INTRODUCTION

Brief interventions include evidence-based and cost-effective psychosocial practices that aim to address harms related to substance use, leading to reduction in harmful use of substances. The World Health Organization describes brief interventions as those aimed at identifying current or potential problems associated with substance use and motivate those at risk to change their substance use behavior.[1] Similarly, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration also proposes that brief interventions are practices that aim to evaluate potential problems and motivate a person to do something about his/her substance abuse either by natural, patient-directed method or by seeking treatment.[2] Brief interventions are based on the harm-reduction principle, which ultimately is aimed at making the person understand the problems associated with his/her pattern of substance abuse and start modifying his/her behavior so as to reduce the harms occurring due to substance use.

Brief interventions are delivered to persons in a structured way through counseling sessions. This intervention follows a patient-oriented approach. It is usually applicable to patients who have inadequate insight into their substance use and who consult with other medical specialties due to complications from substance use. This intervention is not meant to systematically treat patients with severe dependence, but to handle those who have been identified to have risky or problematic substance abuse. A related term is screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT), which refers to screening brief intervention and referral to treatment. In this kind of paradigm, individuals are screened for substance taking behaviors and are provided counseling to quit the substances, and then are referred to addiction treatment services, when continued or sustained treatment is required.

Brief interventions themselves are generally short-term counseling interventions. They can be delivered by a variety of appropriately trained professionals, such as psychiatrists, physicians, and nurses. They can target diverse populations who are considered at-risk (e.g., adolescents) and where opportunity is provided for promoting healthy behaviors (e.g., patients admitted to medical wards). Flexibility is allowed in the settings where brief interventions are provided. Thus, brief intervention seems to be a cost-effective scalable method of reaching out to a large number of substance users. However, the depth of brief intervention is often limited, as compared to other systematic therapies such as cognitive behavior therapy or dialectical behavior therapy. The present guidelines provide an overall framework for the conduct of brief interventions and provide recommendations about the use of brief interventions in the clinical setting. The nuances of providing brief interventions in the Indian setting are also discussed. Since this document is intended to be used for patients, we use the term “patient” rather than “clients” throughout the document. Relapse prevention counseling is a term that helps patients to keep off substances once they stop using, and has different connotations than brief interventions, which aim to target the current substance users. Relapse prevention counseling is not covered in the present guidelines.

THEORETICAL AND PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR BRIEF INTERVENTION

Stages of change model

Prochaska and Diclemente proposed the model of stages of behavior change, which provides a framework of how individuals change their problematic behaviors. This model has been widely used in substance use interventions practice, and Table 1 presents the salient features of the stages of change. These stages of change can be used to determine what kind of intervention would be suited to the person concerned. Understanding these stages and working accordingly are important, or else the health professional may try to cover issues in the clinical encounter which are otherwise not warranted. In the model of stages of behavior change, brief intervention is likely to be useful for the precontemplation and contemplation stages.

Table 1.

Stages of change model

| Stage | Feature | Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Precontemplation | A person does not recognize that his/her substance use pattern has caused a problem in life. There is no desire to change substance use pattern. Such persons can be made to realize the problems that have occurred due to substance abuse | The persons should be given information which connects substance use and his/her physical/mental health problems in a nonjudgmental way. Necessary steps can be taken to educate the person about the negative or harmful consequences of substance use |

| Contemplation | At this stage, person starts realizing that his/her substance use behavior is problematic. Such persons usually remain uncertain about how to proceed to alter dysfunctional behavior. They are ambivalent toward substance use behavior, and decisional balancing may tip the person toward quitting substance | Facilitating understanding regarding problems and substance use behavior. Explore ambivalence and build better comprehension. Enhance the benefits of reducing or stopping substance use and draw attention to harms if substance use persists |

| Preparation | Person starts making plans to change the undesired behavior | The individual is willing to take treatment. His/her commitment needs to be cemented further. Treatment options can be provided |

| Action | Person takes necessary steps to cut down or reduce substance use (including treatment) | In this stage, the focus should be on helping continue skills to maintain abstinence and therapist should acknowledge the person’s experience and encourage social support and self-efficacy |

| Maintenance | Focus is on sustaining the changes made in behavior and prevent relapse to substance use behavior | Attempts should be made to ensure the prevention of relapse. Patient’s current actions should be evaluated, and long-term abstinence should be promoted |

Adapted from Prochaska JO, DiClemente CO. The transtheoretical approach. In Norcross, John C.; Goldfried, Marvin R. (eds.). Handbook of psychotherapy integration. Oxford series in clinical psychology (2nd ed.). 2005. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 147–171

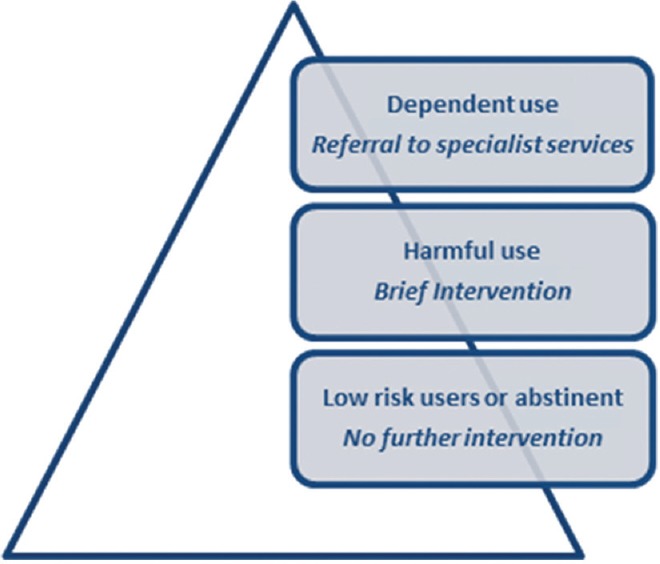

Brief intervention and substance use disorder severity

One important consideration for brief intervention is who the recipients should be for such brief interventions. As shown in Figure 1, brief interventions are well suited for those who have harmful substance use but are not dependent users. Thus, brief interventions could be potentially of use to larger segments of population who have high-risk use, who are not usually catered to by the specialist services. At the same time, health-care providers who are providing brief interventions can link such persons to specialist service providers if the severity of substance use disorders is found to be high or the brief intervention is found to be ineffective.

Figure 1.

Substance use harms and potential interventions

What are the components of brief interventions?

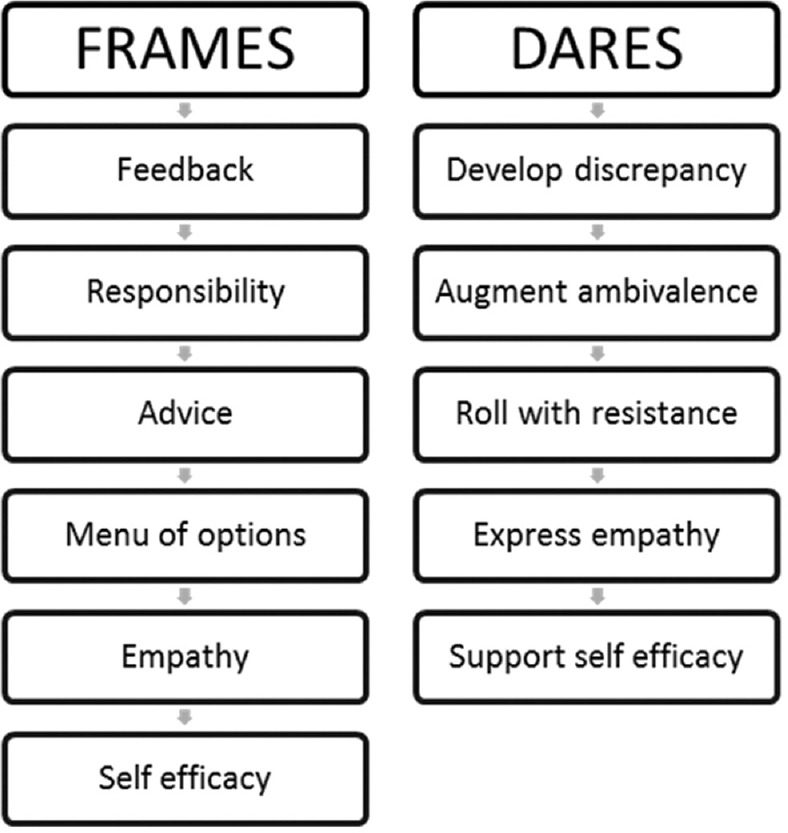

The overarching goal of brief intervention is to make changes to substance taking behavior (either cutting it down or complete cessation). Certain elements of brief interventions have been talked about, popularly known by the acronyms FRAMES and DARES [outlined in Figure 2 below] [2,3]. The individual elements are discussed below, though one should be aware that these are not sequential, and elements often flow into one another.

Figure 2.

Techniques for enhancing motivation and keeping the patient motivated in brief intervention

Feedback

The individual is given personally relevant feedback based on how the substance use is impacting himself/herself or a significant other. Feedback is often ingrained in the assessment process. Any recent medical investigation (like liver function test, pulmonary function test, etc.), which is likely to be linked to the substance taking behavior, can be the starting point for providing feedback. A here-and-now example of how substance use is impacting the person would be better content for feedback, rather than a risk of something happening in the future. While providing feedback, one has to take due consideration of local values, cultural aspects, and literacy level.

Responsibility

This conveys that the responsibility of effecting a change lies with the person concerned. The therapist conveys that the decision to take or not take the substance is left to the individual. This has been shown to improve the motivation and decrease the resistance to change.

Advice

This component aims to make the individual aware of the potential harm of continuing substance taking behavior and to advise him/her to quit. Sometimes, substance users are not aware of the harms, and making them aware would help them to make a clear decision. Furthermore, the benefits of quitting need to be clearly conveyed to the individual so that it influences his/her decision regarding stopping or continuing substance use. In addition, a clear message from health-care providers to quit a substance may help the person to make a decision to reduce or cease the substance taking behavior.

Menu of options

To further strengthen the motivation of the person to reduce or stop substance use, one has to provide alternative solutions or strategies which will help in various circumstances to maintain abstinence. Once patients are aware that there are other ways to deal with their substance use behavior, they are in a better position to choose the suitable option for their life and social activity. A particular strategy may work for a few but not for others. By being more aware of the ways of cutting down substance taking behavior, they would be in a better position to mitigate the effects of substance use behavior. Table 2 provides a sample menu of options for patients.

Table 2.

Menu of options while using brief intervention framework

| Strategies for menu of options |

|---|

| Learn to identify high-risk situations for relapse/lapse and develop coping skills to handle them |

| Develop other productive social activities such as - hobbies, sports, gymming, music |

| Strengthen social support - associate with people who will help in making a change in undesired behavior |

| Read through self-help resources and gather information |

| Maintaining a diary for substance use behavior |

| Using money for other purpose rather than substance use |

| Information regarding other counseling services related to substance use |

Empathy

One of the most important aspects of delivering brief interventions is to provide and ensure an empathic and reflective counseling. The patient must feel and experience a nonjudgment stance from the provider, or else the alliance might become fractured, and the patient might not be receptive. Being warm, reflective, and empathic toward the patients might enhance their confidence and might result in better heed to the advice.

Self-efficacy

The therapist must make efforts to enhance the confidence of patient in modifying his behavior. Once the person feels confident, he/she is likely to put in efforts to reduce or cease the substance taking behavior. Generating self-efficacy thoughts from within is likely to provide better outcomes for the patient.

An ingrained consideration in conducting brief interventions is motivation enhancement through motivational interviewing. Motivation interviewing is considered as a patient-centered counseling aimed at enhancing the motivation of substance users to progress in their stage of change. The elements used in motivational interviewing are best remembered with the acronym DARES, as follows.

Developing discrepancy

This aims to develop an incongruence between what the patient wants to attain with his/her health and well-being, and how the substance use impairs the attainment of such a desire. Substance use is often associated with both hedonic gratification and adverse consequences. The discrepancy is about making the person consciously aware about substance use being associated with consequences (and not only pleasure).

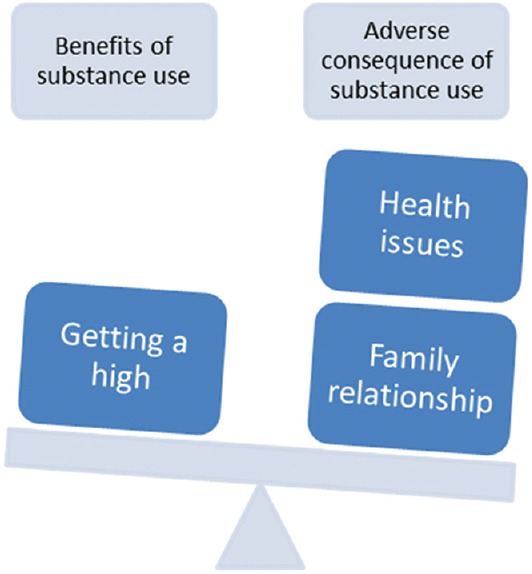

Augment ambivalence

Substance users often have both types of thoughts – to continue the substance taking behavior and to stop it for various reasons. However, such thoughts are not in conscious awareness. Augmenting ambivalence aims to increase the cognitive dissonance from the patient's point of view, about the benefits and harms of substance taking behavior using decisional balancing as an example [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Augmenting ambivalence using decisional balancing

Roll with resistance

Patients are likely to show resistance, particularly when the therapist or health-care provider preaches about substance cessation. They would have encountered many situations when their friends and family would have implored them to stop, and yet they continue. Hence, direct confrontation is likely to lead to a patient becoming defensive or uncooperative. Thus, when resistance is encountered from the patient, then it would be better to take a non-confrontational approach and move the conversation to a different direction.

Express empathy

It is important to acknowledge the patient's current condition and empathize with the fact that quitting substance use is not easy. The patient may not have adequate reasons to quit or be able to engage adequate resources to quit. Empathy with his/her condition might help to provide pragmatic suggestions to help patients quit and abstain.

Support self-efficacy

Supporting self-efficacy of the patients has the advantage of strengthening their self-confidence. This enables them to take measures themselves to bring about change in the substance use behavior.

The above-mentioned constructs and elements of brief interventions can help to understand what is done during the process of brief intervention. The processes involve reflective listening, shifting focus, using praise statements to strengthen self-efficacy, and using open-ended questions, especially when resistance is encountered.[3]

What are possible formats of brief interventions?

Although there can be a wide heterogeneity in the formats or manner of conduct of brief interventions, generally, such an intervention is described as time-limited and has a specific goal. The goal is either to make the patient reflect on the substance use or to agree for a referral to a specific treatment setting or helping the person to quit or reduce substance. The goal would be tailored to the individual and the stage of change he/she is in. The typical duration of a brief intervention session would be <15 min in a single session, but alterations can be made in the form of longer duration of sessions or splitting the agenda into two or more sessions. In general, for the approach to be considered brief interventions, the maximum would be 4 sessions of up to 30 min. The setting can be diverse, either in a hospital, at the bedside, in an office setting, or a community screening program. Thus, there can be a considerable degree of variability in the way brief interventions are conducted.

Since several approaches can be subsumed under the umbrella of brief interventions, some of the brief psychotherapeutic measures which are not typically considered as brief interventions are worth mentioning here. These include brief cognitive behavior therapies, brief humanistic and existential therapies, brief psychodynamic therapy, brief family therapy, and time-limited group therapy. These approaches have been developed as briefer versions of their original psychotherapeutic interventions, but typically involve conduct over several sessions by trained psychotherapists.

Advantages and limitations of brief interventions

There are several advantages of brief interventions which make this approach appealing for implementation. The first is its versatility and suitability in any setting. Brief interventions can be conducted in a variety of settings and thus, does not restrict the patient to report to a specific location for therapy. Second, the limited time duration places less time constraints on the therapist delivering this intervention. This is time-saving and allows several patients to receive the intervention. Third, brief interventions can be integrated into routine assessments and can be linked up to further care. Fourth, it can be an effective approach in individuals who are not very motivated to change their substance taking behaviors. Fifth, a wide variety of professionals is able to provide this intervention. This makes this approach amenable for scale-up. Finally, even in patients with severe substance use, who need more intensive interventions, brief interventions can be helpful in engaging them and motivating them to seek more intensive treatments. The limitations of brief interventions include limited literature on sustained efficacy and continued search for outcome measures (response to referral request or actual cessation of substance), as well as resistance to its use.

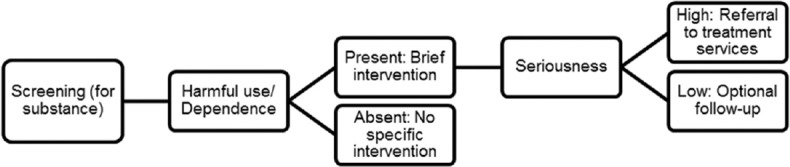

The screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment framework

The SBIRT framework, as shown schematically in Figure 4, merges screening of at-risk population and then determining whether brief intervention or other more intensive approaches are required. The screening can be done by face-to-face assessments or through self-rated instruments, like the alcohol use disorder identification test (AUDIT).[4] Based on the cutoff obtained on the assessment, one can determine if the substance user has a pattern of substance use, which is problematic or tentatively qualifies for a diagnosis. When problematic substance use is identified, then brief intervention can be attempted to understand the current understanding and motivation of the patient and to make changes in substance use. If the substance use is not at a severe level that requires formal medical/psychotherapeutic intervention, then only brief intervention would suffice, aiming to reduce or cease problematic substance use. Those who have greater severity of problems are referred to substance use disorder treatment services and are treated accordingly. For example, those who experience withdrawals while quitting alcohol are recommended detoxification. An important strategy is to ensure steps so that the substance user does not slip through the gaps between the identification of problem and provision of care. For example, reducing the time interval between assessment, brief intervention, and treatment to a referral center, and ensuring that an appointment is made at the referred treatment facility.

Figure 4.

Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment framework

Indications

The brief intervention aims to cater to a wide variety of persons with high-risk of problematic use of substances. It can even cater to those who are otherwise unsuitable for other types of psychotherapy, for example, those with low motivation. The substances which are target of brief intervention can include alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, and other psychoactive substances.

Contraindications

However, some individuals may be quite unsuited for brief interventions. For example, those who are currently in delirium or a confused mental state or are likely to have complicated withdrawals. Furthermore, those patients who are currently agitated, actively suicidal, or have serious psychopathology are unsuitable for brief intervention. However, merely having an additional psychiatric disorder along with a substance use diagnosis (i.e., dual diagnosis) is not necessarily a contraindication for brief intervention.[5]

Assessment and formulation

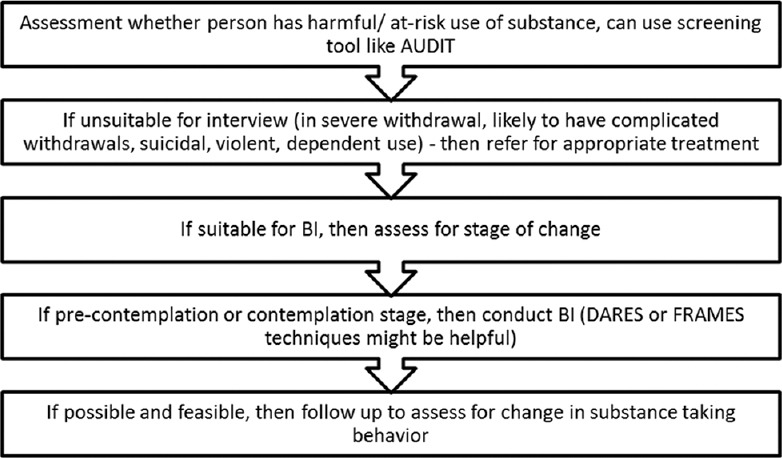

The assessment, formulation, and conduct of brief intervention are presented in Figure 5. The initial phase of assessment can use a screening tool to assess for problematic substance use, for example, AUDIT for alcohol. If the patient is unsuitable for brief intervention, i.e., being in severe withdrawal, likely to have complicated withdrawals, suicidal, violent, or dependent use, then the patient may be referred for specific treatment. If the patient is suitable for brief intervention, then assess for the stage of change. If the patient is in pre-contemplation or contemplation stage, a brief intervention session is conducted. If possible and feasible, then the patient is followed up to assess for change in substance taking behavior.

Figure 5.

Assessment, formulation, and conduct of brief intervention. AUDIT: Alcohol use disorder identification test; BI: Brief intervention; DARES: Develop discrepancy, augment ambivalence, roll with resistance, express empathy, support self-efficacy; FRAMES: Feedback, responsibility, advice, menu of options, empathy, self-efficacy

EFFICACY OF BRIEF INTERVENTIONS IN VARIOUS SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS

Brief interventions have been tried for a variety of substance use disorders and have shown some promise. There is strong evidence for the effectiveness of brief interventions in primary care for substance use disorders [Table 3].

Table 3.

Summary of the evidence base of brief intervention

| Substance/population | Efficacy data |

|---|---|

| Substance | |

| Alcohol | Small effect sizes, seem to work better for at-risk users than dependent users |

| Tobacco | Physician advice coupled with providing assistance to quit might be more effective than a suggestion to quit tobacco |

| Cannabis | Mixed evidence of being efficacious |

| Illicit drug use | Less promising than alcohol use disorders |

| Special populations | |

| Adolescents | Some efficacy for alcohol-related behaviors |

| Pregnant women | Inconclusive evidence of efficacy |

| Emergency department attendees | Reduced alcohol consumption for short term |

Alcohol use

Brief interventions have probably been tried to the largest extent in the context of alcohol use disorders. In a meta-analysis conducted in 2002, 54 studies were included, which assessed brief intervention.[6] The authors classified the studies as those primarily including treatment-seeking population, and those which had nontreatment seeking samples. In nontreatment seeking samples, brief interventions were more effective than control conditions, with small to moderate effect sizes. In treatment-seeking population samples, brief interventions were no more effective than control conditions.

In another meta-analysis, studies of brief motivation enhancement were compared to control conditions.[7] The findings suggested an overall effect size of 0.18 (small). However, the effect size was greater when the studies of 3 months or less were included, suggesting that the effect did not persist for a long duration. Furthermore, the efficacy was greater when dependent users were excluded, suggesting that brief motivation enhancement worked better on those who were at-risk drinkers rather than dependent drinkers.

A recent Cochrane review included 69 studies of brief interventions.[8] The meta-analysis included more than 33,000 participants. The primary meta-analysis included 34 studies and suggesting that who received brief intervention consumed less alcohol than minimal or no intervention participants after 1 year. It was seen that both men and women reduced alcohol consumption after receiving brief intervention. The authors also found minimal, but statistically significant effect of brief intervention on the frequency of binges per week and drinking days per week. Longer counseling duration did not have much additional effect, according to this meta-analysis.

There are a few studies from India which have suggested a brief intervention to be an efficacious modality for individuals with problematic alcohol use, including in primary health-care setting, community setting, and the workplace.[9,10,11]

Tobacco use disorders

Brief intervention for tobacco cessation uses the principles of motivational interviewing. A variant known as the 5As models (Ask at every visit, Advise to quit, Assess readiness to quit, Assist with a quit plan, and Arrange a referral to a specialist when required) has been in use to help tobacco users quit. A meta-analysis has looked at the effect of opportunistic brief physician advice to stop smoking and offer assistance in the medical setting.[12] From the 13 studies included in the meta-analysis, advice to quit on medical grounds, compared to no intervention, increased the frequency of quit attempts. Behavioral support for cessation and offering assistance to quit was associated with more quit attempts as compared to only quit advice. This suggests that physician advice, coupled with providing assistance to quit might be more effective than a suggestion to quit tobacco. Studies are available from India, which have suggested a brief intervention to be more effective than simple advice for tobacco cessation.[11,13]

One meta-analysis evaluated whether brief intervention for alcohol use disorders led to cessation of tobacco use as well.[14] The authors found that there were high rates of smoking cessation in both brief intervention and control groups. However, brief intervention for alcohol use disorder was not found to be superior to the control condition for tobacco cessation. This suggested that since the focus of brief intervention was alcohol, the benefits only accrued for alcohol use reduction.

Cannabis use disorders

A review of 27 studies from across the globe evaluated the effect of brief interventions for cannabis use.[15] The review included brief interventions across a variety of setting (like school, college campus, general population, etc.), and used different kinds of delivery modes (like face to face counseling, web-based, telephone-based, etc.). While some of the studies showed the efficacy of brief intervention, others did not endorse its efficacy. A meta-analysis was not performed, limiting the generalizability of the inferences.

Illicit substance use

The brief intervention has been attempted for illicit drug use as well. In a three-arm randomized trial,[16] participants with illicit substance use in primary care were provided brief intervention, motivational interviewing, or no intervention. At 6 months’ follow-up, it was seen that brief intervention was not superior to no intervention for the outcome measure of self-identified drug use in the past 30 days. A secondary analysis from the work also suggested that brief intervention did not increase treatment-seeking subsequently.[17] Similar results were obtained for a randomized controlled study in the emergency setting which used brief intervention for those with problematic drug use.[18] Thus, the role of brief intervention in illicit drug use remains somewhat less promising as compared to its usefulness in reducing alcohol or tobacco use.

SPECIAL POPULATIONS AND NEWER DELIVERY FORMATS

Adolescents

A systematic review of studies of SBIRT in adolescents showed effectiveness in 4 of the 7 studies.[19] The improved outcomes were in terms of either alcohol consumption or alcohol-related consequences. Beaton et al.[20] reviewed the literature on the utility of brief intervention in the adolescent population, in light of the recommendation of SBIRT by the American Academy of Pediatrics, in its 2011 policy document. The authors deduced that the literature was starting to show the efficacy of SBIRT in reducing substance use among adolescents. The effect of motivational interviewing on adolescent illicit substance use has been evaluated by Li et al.[21] The authors found that motivational interviewing did not have a significant effect on drug use behaviors, but resulted in significant changes in attitudes toward drug-taking behavior. Taken overall, the evidence suggests that brief intervention in adolescents might not have a robust role in prevention or cessation. This might be due to greater risk-taking among adolescents, partly contributed by the still-maturing brain of the adolescents.

Pregnant women

Alcohol use during pregnancy has been known to cause fetal malformations and growth aberrations. Brief interventions have been delivered during pregnancy and evaluated.[22] Four randomized controlled trials have shown that brief intervention as well as control condition were both associated with reduction in alcohol consumption. Significant differences between brief intervention and control condition were not forthcoming. The authors suggest brief intervention can be provided during antenatal care to achieve sobriety during pregnancy.

Emergency attendees

Emergency department visits probably provide a “teachable moment” for individuals with risky substance use. This is especially true if the substance use has been the cause of the emergency visit (e.g., violent brawl after intoxication and accident after drunken driving). A recent systematic review has evaluated the effect of brief interventions for alcohol use disorders among patients who were at risk for alcohol use disorders.[23] The researchers found that in 16 studies, both brief intervention and control condition were effective in reducing the consumption of alcohol. Nine out of these sixteen studies showed that brief intervention was superior to control condition in the reduction of alcohol consumption. It has also been seen that low or moderate drinkers were more likely to be benefitted by brief interventions than dependent drinkers. The author also remarked that if the emergency visit was attributable to the consequences of alcohol, then brief intervention was associated with a greater reduction of alcohol consumption. Another group of researchers suggested that the effect of brief intervention in the emergency department was more pronounced for reducing alcohol consumption in the short-term (i.e., within 3 months), rather than long-term (i.e., at 1 year),[24] suggesting that the effects tend to dissipate with time.

PRAGMATIC ASPECTS IN CONDUCT AND SCALE-UP

Barriers and facilitators to implementation

Some literature which has looked at barriers and facilitators of brief intervention or SBIRT has accrued over the years.[25] The barriers have been classified as being at the organization level, provider level, and at the patient level. Organization factors include context of delivery, and primary care physicians and nurses (rather than specialists) were deemed suitable for brief intervention, while lack of managerial support and lack of financial incentives were found to be barriers for implementation. From the provider's perspective, perceived lack of knowledge and confidence in giving advice were deemed as barriers. Clinical inertia in busy emergency setting was seen as another barrier. Furthermore, lack of training and disinclination to ask about drinking habits emerged as other barriers. With respect to patient characteristics, women and those who were employed were less likely to be asked questions related to drinking, and attendance to referral was better if arranged in a short span of time. The barriers discussed above can be taken into consideration when SBIRT is being implemented in a new setting or service.

Considerations for brief interventions in the Indian clinical setting

Health-care service approaches in India are different than in other parts of the world. The clinical clientele is also inevitably different from other parts of the world, due to differences in culture and societal values. Hence, the following may be considered while delivering brief interventions in the Indian clinical scenario.

Patient inclination and psychological mindedness – Since brief interventions are focused on the patient's problems and are time-limited, with constrained scope for introspection, the patient's psychological mindedness is not an issue. However, patient inclination (or resistance) to change behavior may be encountered, which might lead to obstruction to flow of communication

Doctor-pleasing – Indian patients are frequently likely to agree to what the doctors say, and unlikely to express their dissent. This might lead to an impression of brief intervention working well, although in reality, the person might be report improvement merely in deference to the health-care professional

The elderly patients – Younger health-care professionals might find it difficult to discuss the problem of alcohol use in older patients, particularly in recommending lifestyle changes among the elderly

The family intertwinement – Unlike in the West, family members are closely associated in the provision of health care; and hence, the brief intervention session may need to include them as well. However, this has the potential of taking the focus away to a distressed and disparaging family member who is waiting for an opportunity to ventilate feelings

Territorial boundaries in health care – Health-care systems often throw up challenges when care provision is not integrated. A patient admitted to a medical and surgical specialty remains their specific dominion until consult is sought for a particular reason. And the consult is often expected to be limited to the question asked. Therefore, while providing brief intervention, the referring physician/surgeon needs to be sensitized about the need for referral, or better still, themselves trained in brief intervention

Workload – High patient loads and lack of adequate time for attending to each patient may make implementation of brief intervention difficult. Health-care professionals often triage their time and patient needs. If brief intervention is lower on the list of priorities, then it is likely to be missed in the busy clinical setting

Referral processes – Referral systems in the Indian setting (barring a few places), is not well organized. Hence, implementing SBIRT would be challenging as the patients may face systemic barriers and hassles when going through the suggested referrals.

Application and utility of brief intervention in India

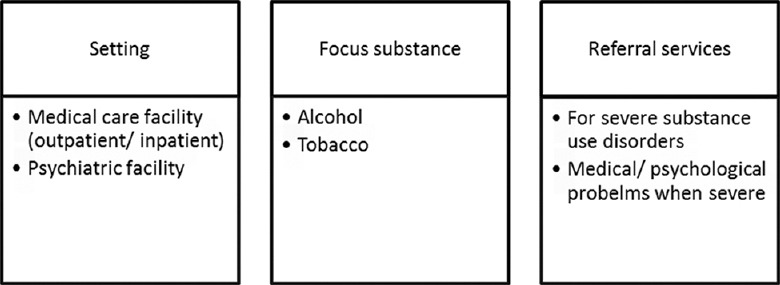

Keeping in mind the issues raised in the previous section, the following can guide the application of brief interventions in the Indian setting [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

Using brief interventions in the clinical setting

Setting: Brief intervention can be conducted in medical care settings, general psychiatric care setting, and in schools and colleges

Focus substance: As of now, brief intervention should be limited to alcohol and/or tobacco use disorders

Personnel: Adequately trained personnel including physicians, psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses, and social workers can implement brief interventions

Link to treatment facilities: When the substance use severity is high, then brief intervention should be linked to other treatment facilities.

The advantage of a brief intervention lies in its being a simple and easy to implement intervention. Although busy workload and lack of privacy are concerns, this type of intervention when conducted might lead to a health promotion cascade, leading to improved health outcomes for self and others.

CONCLUSION

Brief interventions are promising psychologically oriented, time-limited counseling approaches that target high-risk substance users. The SBIRT adds a component of screening and referral to specialist services when required. Brief interventions can be carried out in a variety of settings, including primary care and emergency departments. Research has largely focused on alcohol use disorders, where brief interventions have shown benefits, especially in the short-term. Those who are currently not seeking treatment are likely to be benefitted the most. Being a cost-effective measure, and given the ease of delivery by a variety of professionals, brief interventions have the potential to be applied to large segments of the population in need. Certain aspects of the delivery of this intervention would need careful consideration when applied in the Indian health-care system.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Henry-Edwards S, Humeniuk R, Ali R, Monteiro M, Poznyak V. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. Brief Intervention for Substance Use: A Manual for Use in Primary Care. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Brief interventions and brief therapies for substance abuse. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 34. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Helping people change. New York: Guilford press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graham HL, Copello A, Griffith E, Freemantle N, McCrone P, Clarke L, et al. Pilot randomised trial of a brief intervention for comorbid substance misuse in psychiatric in-patient settings. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;133:298–309. doi: 10.1111/acps.12530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moyer A, Finney JW, Swearingen CE, Vergun P. Brief interventions for alcohol problems: A meta-analytic review of controlled investigations in treatment-seeking and non-treatment-seeking populations. Addiction. 2002;97:279–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vasilaki EI, Hosier SG, Cox WM. The efficacy of motivational interviewing as a brief intervention for excessive drinking: A meta-analytic review. Alcohol Alcohol. 2006;41:328–35. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agl016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaner EF, Beyer FR, Muirhead C, Campbell F, Pienaar ED, Bertholet N, et al. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;2:CD004148. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004148.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joseph J, Das K, Sharma S, Basu D. ASSIST-linked alcohol screening and brief intervention in Indian work-place setting: Result of a 4 month Follow-up. Indian J Soc Psychiatry. 2014;30:80–6. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pal HR, Yadav D, Mehta S, Mohan I. A comparison of brief intervention versus simple advice for alcohol use disorders in a North India community-based sample followed for 3 months. Alcohol Alcohol. 2007;42:328–32. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sabari Sridhar OT, Murthy P, Kishore Kumar KV. Integrated brief tobacco and alcohol cessation intervention in a primary health-care setting in Karnataka. Indian J Public Health. 2017;61:S29–34. doi: 10.4103/ijph.IJPH_235_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aveyard P, Begh R, Parsons A, West R. Brief opportunistic smoking cessation interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis to compare advice to quit and offer of assistance. Addiction. 2012;107:1066–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jhanjee S, Lal R, Mishra A, Yadav D. A randomized pilot study of brief intervention versus simple advice for women tobacco users in an Urban community in India. Indian J Psychol Med. 2017;39:131–6. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.203121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCambridge J, Jenkins RJ. Do brief interventions which target alcohol consumption also reduce cigarette smoking? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;96:263–70. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parmar A, Sarkar S. Brief interventions for cannabis use disorders: A review. Addict Disord Their Treat. 2017;16:80–93. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saitz R, Palfai TP, Cheng DM, Alford DP, Bernstein JA, Lloyd-Travaglini CA, et al. Screening and brief intervention for drug use in primary care: The ASPIRE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:502–13. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim TW, Bernstein J, Cheng DM, Lloyd-Travaglini C, Samet JH, Palfai TP, et al. Receipt of addiction treatment as a consequence of a brief intervention for drug use in primary care: A randomized trial. Addiction. 2017;112:818–27. doi: 10.1111/add.13701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bogenschutz MP, Donovan DM, Mandler RN, Perl HI, Forcehimes AA, Crandall C, et al. Brief intervention for patients with problematic drug use presenting in emergency departments: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1736–45. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuma-Guerrero PJ, Lawson KA, Velasquez MM, von Sternberg K, Maxson T, Garcia N. Screening, brief intervention, and referral for alcohol use in adolescents: A systematic review. Pediatrics. 2012;130:115–22. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beaton A, Shubkin CD, Chapman S. Addressing substance misuse in adolescents: A review of the literature on the screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment model. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2016;28:258–65. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li L, Zhu S, Tse N, Tse S, Wong P. Effectiveness of motivational interviewing to reduce illicit drug use in adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction. 2016;111:795–805. doi: 10.1111/add.13285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nilsen P. Brief alcohol intervention to prevent drinking during pregnancy: An overview of research findings. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2009;21:496–500. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e328332a74c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barata IA, Shandro JR, Montgomery M, Polansky R, Sachs CJ, Duber HC, et al. Effectiveness of SBIRT for alcohol use disorders in the emergency department: A Systematic Review. West J Emerg Med. 2017;18:1143–52. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2017.7.34373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McGinnes RA, Hutton JE, Weiland TJ, Fatovich DM, Egerton-Warburton D. Review article: Effectiveness of ultra-brief interventions in the emergency department to reduce alcohol consumption: A systematic review. Emerg Med Australas. 2016;28:629–40. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson M, Jackson R, Guillaume L, Meier P, Goyder E. Barriers and facilitators to implementing screening and brief intervention for alcohol misuse: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. J Public Health (Oxf) 2011;33:412–21. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdq095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]