OUTLINE

Introduction

Evolution of concept

Principles of interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT)

Assessment and Structure of IPT

Steps in IPT

IPT in Depression

-

Interpersonal problem areas and relevant strategies

- Grief

- Role disputes

- Role transition

- Interpersonal (IP) deficits.

Common IPT techniques

Adaptations for depression in special populations

Adaptations for other mood disorders

Adaptations for non mood disorders

INTRODUCTION

Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) is a time-limited and diagnosis-targeted intervention

It follows a strict time-limited format

IPT has been successfully adapted for various other psychiatric disorders

IPT follows a simple paradigm by assigning the patients a sick role by defining their problems as treatable medical conditions and linking their state of affective distress to their IP situations

IPT focuses on the “here and now” of the illness by resolving issues related to IP problem areas[1]

-

IPT has nonspecific and specific elements:

- Nonspecific elements include nonjudgmental approach, empathic listening, maintaining confidentiality, expressing warmth, and engaging the patient in the therapy

- Specific elements include providing patients a sick role, applying an IP inventory, and making a formulation that links the patients’ IP problem areas with their psychiatric diagnosis.

IPT follows a holistic approach, and it is recommended to use IPT in an integrated manner

The underlying assumption is that IP relationships of a person either in the past or in the present, play a role in the origin and maintenance of psychopathology. Hence, IPT mainly focuses on IP context and related factors. The goal is to either help patients improve their IP relationships or change their expectations about them and focusing on improvements in their social support networks

The specific elements of IPT constitute its basic core, but can be adapted in various ways. IPT can be planned as a short-term, time-limited therapy, maintenance therapy, or long-term, insight-oriented treatment

IPT can be adapted for different age groups including adolescents and elderly, and can also be adapted depending on the target diagnosis

There can be adaptations in the format of IPT for individuals or groups or couples

IPT can be adapted for any psychiatric disorder where IP problems exist[2]

Insight-oriented IPT, on the other hand, emphasizes that the therapist cannot be a neutral observer, but is rather a participant. The task for the therapist is to understand his own reactions toward the patients and reflect them therapeutically, by uncovering, resolving, and termination.[2]

EVOLUTION OF CONCEPT

The principles in the IPT are broadly based on the following models:

Biopsychosocial model

Some concepts of IPT are based on the Adolf Meyer's school of psychobiology, which sees psychiatric disorders as a consequence of an individual's attempts to adapt to psychosocial environment. The model further emphasizes that a person's current state of psychological functioning is a complex interplay of biological correlates, physiological factors, social relationships, and various psychological correlates such as one's temperament and attachment pattern[3]

Thus, IPT is based on the biopsychosocial model of psychological functioning as it views the psychiatric symptoms in a broader aspect

IPT emphasizes on the attachment bonds and effective communication as important predictors of good psychological functioning

IPT builds on the principle that intimacy is protective against the development of depression, especially when facing stressful life events, which frequently precede depression

The biopsychosocial model also stresses upon the patient actively taking the responsibility of making changes in IP relationships and his/her social environment rather than waiting for changes to happen on his/her own.

Harry Stack Sullivan's theory of interpersonal relationship and parataxic distortion

Harry Stack Sullivan's theory of IP relationship emphasizes on the role of social, cultural, and familial factors in the genesis of psychiatric illnesses[3,4]

Sullivan stressed on that maladaptive behaviors emerge as a result of one's attempt to deal with the social environment

He described parataxic distortion as a phenomenon in which the characteristics of previous relationships are imposed upon new ones, which results in distortions in the current relationships.

John Bowlby's working model of relationships

John Bowlby further built on the concept that the previous relationships an individual has had (whether healthy or otherwise), determine the ways in which he/she behaves in a new relationship.[4]

PRINCIPLES OF INTERPERSONAL PSYCHOTHERAPY

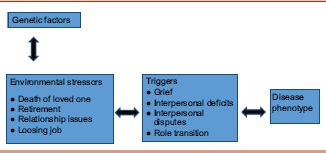

IPT focuses on identifying relationship between environmental triggers related to IP problem areas and clinical symptom onset or the phenotype of the disease

The work of the therapist revolves around helping patients identify these stressors or IP problem areas and relate them to the symptoms or distress. The therapist also encourages patients to find out ways to ameliorate the situation. The interactions are depicted in Box 1.

Box 1.

Stress diathesis model

For depression, IPT builds on the following two important principles:

Depression does not occur due to an individual's fault and it can affect anyone. It is a medical illness which is treatable. Assigning a sick role to the patient helps in defining the problem and also excuses the patient from blaming himself/herself for the illness

The second principle emphasizes that the affective distress and life situations are interrelated. The disturbing life events can either precipitate the symptoms of depression or other mood disorders or can follow the onset of symptoms.[5]

Thus, a disturbance in the environment due to unavoidable stressors leads to changes in IP environment, which eventually leads to the symptoms of depression. When depression sets in, the IP functioning of the patient gets further compromised. It may seem very obvious to an observer that the symptoms have set in due to these triggers, but depressed individuals often tend to blame themselves for these events. The task of the therapist is to help the patient resolve these problems and develop his/her social support system.[6]

Structure of interpersonal psychotherapy

IPT is conducted over 12–20 sessions extending over a period of 4–5 months. In the acute phase, it includes three phases as shown in Box 2

After these three phases are over, a continuation/maintenance phase can be initiated for which a spate contract is made with the patient. An initial assessment for the suitability of IPT is carried out before the initial phase.

Box 2.

Three phases of interpersonal psychotherapy

| Initial/beginning phase: Identifying problem areas, focusing on immediate issues, and deciding targets for the therapy |

| Middle phase: Working on the problem areas (abnormal grief reaction, IP role dispute, role transition, and IP deficits) |

| End/termination phase: Consolidating gains and preparing the patient for handling the IP relationship issues |

IP – Interpersonal

Assessment for the suitability of IPT

The therapist must assess whether the patient is a suitable candidate for IPT prior to initiating the therapy. This phase is carried out for any psychological intervention that a therapist plans to initiate [Box 3]. Patients’ ego strengths and motivation for change are assessed. Certain factors tend to increase the probability that a patient would benefit from the therapy. These include presence of good social support network, presence of an IP focus of distress, ability to relate a coherent narrative of IP network and specific IP interactions, and a secure attachment style. At the end of this phase, a contract is made with the patient regarding the number of sessions that will be carried out and that collectively the therapist will work along with the patient in one or more areas of IP distress.

Box 3.

Assessing suitability of interpersonal therapy

| Assess the ego strengths |

| Assess the motivation |

| Social support network |

| Focus of distress |

| Ability to relate to coherent IP formulation |

IP – Interpersonal

Initial phase

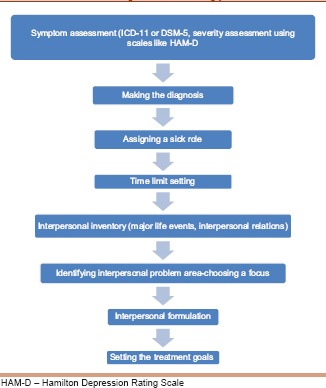

As the sessions begin, the therapist focuses on developing a good therapeutic alliance with the patient. The therapist carefully listens to the patient's complaints, carries out a detailed interview, obtains information about the history of presenting complaints, and identifies the diagnosis and the IP context in which the symptoms have occurred. The following steps are followed.

Assessing the symptoms

A formal diagnosis can be made using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 11 or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 (DSM-5). The severity can be assessed using severity-measuring scales for depression, for example, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (Ham-D). Patients are explained what the scores on these scales mean and that the scales would be repeated during the course of therapy.

Making the diagnosis

Once the diagnosis is made, its prevalence and presenting features can be discussed with the patient. The therapist also discusses about the expectations from the therapy. Once a diagnosis is assigned to the patient, it works in a dual manner. First, it instills hope that the patient has a medical condition which is identifiable and treatable. Second, it identifies the patient as a person who is in need of help. It is emphasized that the patients’ full focus should be on recovery.

Assigning a sick role

Providing a diagnosis gives the patient a “sick role,” which would simply mean that the disturbances in patient's functioning have occurred due to his/her current status and the illness has prevented him/her from performing adequately. It is stressed upon that the symptoms have not occurred due to the patient's own faults. The therapist also discusses with the patient that addressing the current problems in IP functioning will improve his/her psychiatric condition.

Setting a time limit

IPT is strictly a time-limited therapy. Following a strict time limit and initially deciding about a fixed end point helps in keeping the patient motivated to make changes. Prolonged sessions tend to shift the focus from the current IP issues to more intrapsychic conflict exploration, which is not the goal of IPT. Having a time limit and gradual tapering of sessions seems to be better than abrupt discontinuation at the end of 12–20 sessions. The therapist may predecide the number of times a week and number of weeks required for therapy.

Reviewing the need for medications

Evidence suggests that IPT alone can help patients recover from depression, but depending on the severity of symptoms, medications can be initiated. If required, the patient can be referred to the treating psychiatrist for initiating the treatment if the therapist is not a medical professional (clinical psychologist).[7]

Exploring the interpersonal milieu

Moving ahead in the initial phase, the therapist explores about the patient's close relationships and social functioning both in the present and in the past. Details of major life events in patient's life, associated changes in mood, changes in IP relations, and their relation to psychiatric symptoms are explored. All these information are obtained in a structured manner with the help of an IP inventory. The inventory helps in reviewing patient's significant relationships, nature of social relationships, and IP functioning.

Identifying the focus

IP problem areas are identified. Four IP problem areas have been mentioned as shown below. In IPT, one needs to identify the main problem area.

Grief defined as loss of relationships or loss of healthy self

IP role disputes with significant others such as friends, parents, and siblings

IP role transitions including difficulties in adjusting to life changes, which is undesired, unexpected, or for which the patient is not psychologically and emotionally ready

IP skill deficits such as maintaining relationships and communicating about feelings.

Interpersonal formulation

The therapist then prepares an IP formulation linking the target diagnosis to IP focus. It may be possible that more than one problem areas are identified. However, the focus should be on one area at a time or not more than two problem areas. If two problem areas are identified, the one which seems to be more responsive to treatment is dealt with initially. This helps in increasing the patient's competence, helping in recovery. Once the formulation has been prepared, the goals of the therapy and strategies to obtain those goals are discussed with the patient. This helps in formulating a treatment plan, and the strategies can always be referred to while one progresses in the therapy. The initial session usually extends for the first five sessions.

Defining treatment goals

The problem area that will be focused in the current therapy should be discussed with the patient. If there are more than one areas of focus, the one which seems to be more distressing for the patient is addressed initially. Treatment goals need to be decided and discussed with the patient. Practical issues about confidentiality or handling issues of missed appointments should also be discussed. The above steps can be summarized in a flowchart as shown in Box 4.

Box 4.

Steps in performing the initial phase of interpersonal therapy

Middle phase

In the intermediate phase, sessions are focused upon addressing one or more of the four problem areas using IPT techniques. After the identification of specific problem areas in the initial phase, the therapist tries to obtain more information about these specific problem areas. The therapist and the patient then work together to develop solutions for these problems. Solutions may focus upon various domains of an individual's life such as modifying expectations of the patient, improving their communication skills, or developing social support. A suitable solution is selected, and the patient tries to apply it between the sessions. Throughout the sessions, the therapist keeps the patient focused on the specific problem area.

Patients are psychoeducated about their illness and symptoms

Every IP session is important in the therapy. The content and emotional tone, how did the patient feel, what did he/she say, and what was his/her tone, are important for the therapist

If the patient performed well, the therapist congratulates him/her to reinforce the skills

If things did not work well, factors responsible need to be explored

Therapeutic alliance needs to be maintained throughout

At the end of every session, the gains achieved and summary of sessions need to be highlighted

After every session, severity rating scales need to be applied to monitor the progress

The key IPT techniques targeting the four IP problem areas have been discussed later individually.

Termination phase (credit or blame?)

The last few sessions are focused on preparing the patient for termination of the therapy. If the problems have been addressed, the patient needs to be given credit for the success achieved. If the sessions did not turn out to be as successful as planned, blame the treatment. This helps by minimizing the self-blame by the patient. Alternative treatment options such as continuation to the maintenance phase and adding or changing medications are discussed with the patient.

Conducting interpersonal therapy in depression

The relationship between depression and IP problems can be bidirectional. The disorder can arise in the context of IP problems and depression may also interfere with one's IP functioning. Whatever is the cause and irrespective of what appeared first in the time line, IPT focuses on linking mood to the IP state.

The therapist considers that depression has the following three aspects:

The first are the symptoms which include low mood, anhedonia, easy fatigability, poor attention and concentration, eating and sleeping disturbances, and negative thinking

The second aspect is the patient's social and IP context. IP problems can precede or follow depressive symptoms. In addition, the strong social support is protective and social stressors increase the vulnerability for depressive episode

The third aspect is the personality characteristics of the patient. This can either predispose or maintain depression. An enduring pattern of avoiding confrontation, risks, expression, and being dependent may all lead to the occurrence of depressive episode.

Irrespective of what contributes to depression, IPT focuses on dealing with the current IP issues and helps the patient to develop self-reliance to deal with these situations outside the therapy. For psychiatric disorders such as depression, the disturbances in these IP areas result in symptoms. The situations that lead to these IP dysfunctions are the areas of focus in IPT. These include:

Grief

IP role disputes

IP role transitions

IP deficits.

The goals of IPT in depression include:

Decreasing the depressive symptoms

Helping the patient deal with the IP problems that led to depression in a better manner.

The therapist begins by asking questions which can help in understanding about patient's symptoms, such as asking patients:

What brings you here?

How the symptoms started appearing?

Are there any stressors?

How the patient is currently dealing with the stressor?

What happened before the onset of symptoms?

Does the patient feel that something specific happened which triggered the symptoms such as death in the family?

Detailed psychiatric assessment needs to be conducted to confirm the diagnosis. Once the diagnosis of depression is made, the task in the initial sessions is to assess the severity of symptoms using rating scales such as HAM-D or Beck Depression Inventory. Patients should be psychoeducated about depression. One example is as follows:

“Depression is a common mental disorder and is treatable. We can understand your distress, but complaints of decreased confidence and poor attention concentration are the common symptoms of the illness and will resolve as you begin to recover from the illness. This can happen to anyone and with adequate treatment you will recover. The duration may however vary, as some patients respond early and some may take time to get relief from their symptoms.”

Once a sick role has been assigned to the patient, a time limit is decided. The need for starting medications is reviewed. An IP inventory is applied as described previously and the therapist tries to identify the IP problem areas. The therapist then prepares an IP formulation linking the target diagnosis to IP focus Key steps of IPT in depression are outlined in Box 5.

Box 5.

Key steps of performing interpersonal therapy in depression

| Establishing the diagnosis |

| Identifying the focus areas (grief/IP role disputes, IP role transition, IP deficits) |

| Setting the goals (decreasing the symptoms of depression and improving the coping skills) |

| Assigning the sick role |

| Defining the time limit |

| Applying IPT techniques targeting the identified focus areas |

| Terminating therapy (consolidating gains and looking for options to deal with failure, such as continuation and addition of pharmacotherapy) |

IP – Interpersonal; IPT – Interpersonal psychotherapy

Major depressive disorder: Key steps are as follows:

Establishing the diagnosis

Identifying the focus areas (grief/IP role disputes, IP role transition, and IP deficits)

Setting the goals (decreasing symptoms of depression and improving the coping skills)

Assigning the sick role

Defining the time limit

Applying different types of IPT techniques targeting different focus areas

Terminating therapy (consolidating gains and looking for options to deal with failure, such as continuation and addition of pharmacotherapy).

In the subsequent section, we will discuss each of the four IP problem areas and ways to proceed in therapy including the IPT techniques.

FOUR INTERPERSONAL PROBLEM AREAS AND WAYS TO PROCEED IN THERAPY INCLUDING THE IPT TECHNIQUES

Interpersonal psychotherapy techniques

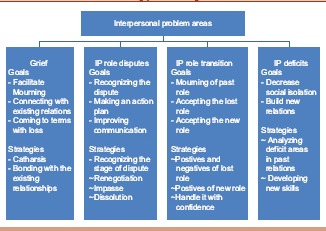

Grief

Grief is selected as a focus, when patients report depressive symptoms following the death of someone significant in their life. The presence of some depressive symptoms following the death is expected and the symptoms resolve as the person starts accepting the death. The low mood, decreased interest in activities, disturbed sleep, and appetite can be a part of normal mourning. However, in some people, the diagnostic threshold for depression is met as they begin to experience significant depressive symptoms leading to socio-occupational dysfunction. In these cases, IPT can be initiated. If the patient approaches due to his/her distress, but still does not meet the diagnostic threshold for depression, IPT can be initiated.

Goals in dealing with grief

The therapy begins with the initial sessions comprising of assigning a sick role to Mr. A as explained previously. The IP inventory would provide information about the IP context. It will provide information of the current relationships Mr. A has irrespective of it being problematic or supportive. Subsequently, the IPT therapist prepares an IP formulation.

Facilitating mourning and coming to terms with the loss

One of the goals in IPT for the management of grief would be catharsis. The therapist encourages the patient to talk about the loss, what they miss the most about the person. Patients are encouraged to describe their relationships, about the sequence of events that occurred prior to the loss, during and after the loss. Patients also tell about all that they experienced since the loss of their loved one. The therapist helps the patient describe all their memories associated with their loved one whom they lost

To connect with the existing relationships and re-establish the lost interests

The other goal of IPT in grief management is to help the patient figure out relations which can act as a substitute for the lost person and lost relationship. One way is to encourage patient to involve others in the process of remembering their lost one.

Strategies in dealing with grief

The strategies includeassessing the psychopathology if any, and help patient relate his/her symptoms with the death of the significant person. The therapist educates the patient about grief and depression, helping the patient to express his/her feelings and helping in finding new pleasurable activities and relationships to substitute the loss.

Catharsis

The strategy that the therapist uses is to encourage patients to talk about their feelings. It is stressed that the expression of feelings does not make a person weak. Some people even fear that once they start expressing their feelings, they may become overwhelmed. Patients are encouraged to focus on the positive and negative aspects of the relationship with the loved one.

Reestablishing the support networks

Death of a loved one often leaves a void in the patient's life, and it is important that this gap is filled up. Once the therapist has explored about the support system of the patient, important relationships in their life can be reestablished. Patients can be encouraged to connect with important people in their life and share their feelings. The therapist must also encourage patients to engage in activities which they enjoyed before the death. This may be difficult for the patient, but still efforts must be made to engage in relationships. Sometimes, patients may completely withdraw themselves from their social life and so, they must be told that they can just go out with a friend to see how things work. Following this, it must be inquired about what the patient enjoyed, which parts he/she did not, and will he/she be interested in repeating the activity again.

As the sessions proceed, the therapist shifts the discussion from being more about the deceased to more about the issues coming up in the new efforts patient is making in reestablishing his/her support system.

The end of the therapy includes termination sessions, focusing on consolidating the gains that occurred in the therapy and preparing patient to work outside the therapy in real-life situations.

Interpersonal role disputes

For a healthy relationship, it is very important that both individuals have a sense of harmony, regard for each other's expectations, and have willingness to compromise for each other. Two people in a relationship may have different aspirations and perspectives, but when their expectations from each other become contrasting or different, it can result in strained relationship. If they do not understand the needs and expectations of each other, it is very likely that disputes will result. If the patient presents with such complaints, the focus of the IPT will be directed toward resolving the role disputes. Often, role transitions may lead to role disputes or the opposite situation. Like shifting to a new job or to a new place may change the expectations, two people in a relationship may have from each other. It can happen the other way around, where differing expectations can interfere with smooth transitions in the role changes one is expected to go through. In either of the circumstances, depression may result from these situations or depression may interfere with the successful handling of these transitions. It is important for the therapist to identify these situations and identify whether role transition or role dispute is the important contributing factor in the initiation or maintenance of depression, and that particular area should be selected as the focus of the therapy.

Goals in the treatment of role disputes

After going through a long-standing role dispute, the patient starts believing that there is no way out and there is no benefit of initiating any therapy. Often, patients find themselves as the main reason behind the dispute and place the partner at a superior position. Goals of the therapy include helping the patient find the dispute, identify it, and look for options to deal with it. The therapist helps to work out a plan of action. Even if the issues may not resolve completely, therapy will help the patient modify his/her expectations or in those cases where even this is not possible, therapy helps the patient in better communication with the partner about his/her expectations and feelings.

Recognizing the dispute

After going through the patient's history of presenting illness, the therapist needs to identify the area of dispute. Even though the patient reports that there is no possible solution, it needs to be reemphasized that no matter what the dispute is, some solution is always possible

Finding options to decide an action plan

After having an agreement with the patient about the dispute area that will be targeted during the therapy, the therapist needs to explore various ways in which the relationship can be renegotiated. If this process is successful, the patient learns to be more assertive and expresses his/her feelings in a more positive and less demeaning way. In cases when the renegotiation does not turn out to be successful, the patients at least learn to communicate their feelings more adequately

Rectifying faulty expectations and facilitating better communication to resolve issues

The cause of many disputes is the contradictory expectations which two people in a relationship have from each other. The goal of the therapy is to identify these faulty expectations and modify them in a better manner. It is better if the partner is also involved in the therapy, but it may not be possible in all cases when the therapist continues sessions with the patient.

Strategies in dealing with role dispute

The following steps are undertaken for dealing with role dispute in IPT:

-

Assessing the depressive symptoms

The key to initiating any session is detailed exploration of the symptoms with which the patient has presented to us. This will be done in the initial sessions of IPT as described previously. The IP inventory also provides information about the IP issues. Once the depressive symptoms have been assessed, the next step is to draw relations between these symptoms and evident or covert dispute. The IP formulation caters to this.

-

Identifying the stage of the dispute

Once the depressive symptoms have been assessed and their relation with the dispute has been drawn, the therapist tries to identify the stage at which the dispute currently is.

-

RenegotiationOften, patients may be aware of the differences in expectations but lack skills to express themselves. They consider their expectations as less important than the other person with whom the dispute is present. The communication between the two people has not stopped. The therapist helps the patient learn that even their expectations are genuine and they need to express it to the other person.

-

ImpasseIn this stage, the relations have reached a point when conversation between the two people has stopped. There are no more discussions and the patient feels that renegotiation is no more an option. Patients feel hopeless about any positive progress in the relationship. At such a stage, discussion can be brought forward clearly in the open.

-

DissolutionThis stage is reached when either one or both the patient and partner are looking out ways and struggling to bring an end to the relation. This is usually not the first stage, but often, patients may report that they do not see a future ahead with their partner and are actively looking out ways to terminate the relationship. At this stage, dissolution is advisable. It must be kept in mind that dissolution may lead to interference in role transition. Strategies that are used in dealing with role dispute are as follows:

- Exploring the patients’ feelings

- Validating these feelings

- Finding out options and deciding out a plan of action depending on the stage of the dispute

- Role play.

-

Once the therapist is aware of the patient's feeling with the IP encounter he/she have, the therapist tries to validate these feelings by considering them genuine and reasonable. If the patient's dispute is at the stage of renegotiation, the patient is encouraged to express about the differences in expectations and communicate his/her objection to the demands made by the other person. The patient may speak about alternative steps, and the therapist must also help the patient understand the consequences of his/her actions. If the stage of impasse has been reached, the therapist encourages the patient to directly ask for the other person's expectations. The disharmony may initially increase, but this opens a conversation between them which had stopped, and it helps the therapist understand the contradictory expectations better. Sometimes, it is better to go for dissolution of the relationship. This is facilitated by the therapist when he/she realizes that the relationship has become strained and both the partners are aspiring to get out of it. This stage should be reserved for the point when all attempts to reestablish the relationship have been explored. The strategy of role play is not only to give the patient a formal homework but also help the patient to do the conversations more easily in real life.

Interpersonal role transition

This category is very wide and may include a large number of situations that one faces in day-to-day life. People who are depressed following role transition often report of difficulty adjusting to the new role and difficulty in giving up the old role. Situations can be multiple, such as marriage, retirement, loss of job, becoming a parent, getting promoted, and getting diagnosed with a disease. Those who are vulnerable to depression have difficulty coping up with these changes, which, in turn, affects their mood and behavior. Sometimes, the changes are unexpected and sudden such as divorce or may be gradual. Sometimes, the transition may have been a desired one such as a planned pregnancy or desired promotion or unexpected such as financial loss. Unexpected losses tend to have a greater impact on the patient. There can be two aspects to role transition. One is that the patient misses his/her old role, often reported in conversations as, “Life was so much better than.” The other aspect is difficulty adjusting to the new role.

Goals in managing role transition

The goal in managing the problem of role transition will be to facilitate the mourning and explain the positive aspects of the transition. Depressed patients emphasize more on the positives of the old role. They consider the change as something that has added to the chaos in their lives.

Facilitating mourning over the old role

Once an old role is lost, patients may have difficulty accepting the transition such as a divorce or an accident. It becomes important that the therapist facilitates the mourning process. The patients must express their feeling about the loss. They may feel sad or may express anger. Some patients also report of not performing their old role adequately and express guilt. Some feel that they have no control over the situation now. The therapist helps the patients to express their feelings

Accepting the loss of old role

Other important aspect of therapy would be that the patients acknowledge their lost role. Once they start doing that, the therapist helps patients to give up their old role

Developing positive outlook toward the new role

Patients may feel apprehensive about their new roles and the therapist tries to explain about all the positive aspects of being in the new role and that the new role is not as bad as the patient was expecting. Patients’ focus is drawn toward the positive aspects of the new role and ways of handling it

Restoring the confidence to fit in the new role

As patients start accepting new role, they gradually develop new skills. This adds to their confidence and helps in restoring their self-esteem. In the process, the patients build up their support group. The entire process may proceed gradually and even if the patients at the end of therapy do not achieve full role transition, they have developed skills for that. This helps in reduction of the depressive symptoms.

Strategies in dealing with role transition

Dealing with role transition may be challenging for the patient and may have been a trigger for their current depressive symptoms. The following aspects can be targeted while dealing with role transition:

Assessing the depressive symptoms

The first step would be to review the depressive symptoms. A detailed history provides important information about the sequence of events and what factors led to depression

Drawing an association between the symptoms and role transition

Once the symptoms have been assessed, the therapist tries to find out the challenges the patient faces in dealing with the new role in which he/she has been put. What were the patient's expectations from the past role and what hurdles they face while dealing with the transition? Why they consider the previous role to be an ideal one. Exploration about the feelings associated with the change is also the part of therapy

Positive and negative aspects of the old and new roles

The therapist now tries to help by reviewing the merits and demerits of both the new and old roles. Good aspects of the new role and negative aspects of the old role are brought to the notice of the patient. The therapist also helps patients to approach the situation in a more realistic way rather than in an ideal way

Helping in adjusting to the new role

The most important aspect in helping patients deal with role transition is helping them acquire skills for the new role. Patients are encouraged to develop social support system which would be required for adjusting to the new role. This potentiates the patient's self-esteem, helping them handle the transition efficiently. As therapy proceeds and patient develops these new skills, depressive symptoms begin to decrease.

Interpersonal deficits

If after detailed exploration no other problem area is found, IP deficits may be chosen as a focus in IPT. They include very few or no attachments, social isolation, or very few relationships. People who fall in this category have poor social skills and avoid IP contact. Often, the results are not favorable when deficits are chosen as the focus in IPT. In addition, if in therapy the therapist feels that no or minimal response is happening, it is better to shift patient to other forms of psychological interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). Individuals lacking close relations, those having difficulty sustaining relationships, or those who fear social relationships as in social phobia fall in this group.

Goals in the treatment of interpersonal deficits

The goal in the treatment is to decrease the isolation and promote the development of new relationships.

Decreasing social isolation

There may be various reasons as to why the patient avoids interaction and prefers isolation. The causes need to be explored. The goal of IPT is to use strategies directed toward reducing the social isolation

Building new relations

In the therapy, efforts are made that patients involve themselves in developing new relations.

Targets in the treatment of interpersonal deficits

The targets of IPT while dealing with IP deficits include:

Assessing the symptoms of depression and relating them to social isolation

Once the patient has given an adequate history, the therapist tries to build a relation between patient's isolation and emergence of depressive symptoms

Analyzing the past relations

It becomes important to explore about the issues, patients had in the past relations and what stops them from indulging in new ones. What were the positive and negative aspects of the past relations they had? Is there a similar pattern in every significant relationship patient has had? Is the patient anxious in making relations or approaching people? What is the fear they have?

Developing new skills.

The therapist tries to encourage patient to get involved in relationships and approach people. When the patient does so, details about how they felt while doing so, what problems they faced, did they like it or not etc., is explored. The therapist may even ask patients to tell about good and bad aspects of the current therapeutic relationships and draw parallels in other relations. It must be noted that drawing parallels does not imply that the issue of transference is addressed, which is not a focus in IPT. Patients may be given tasks to analyze the past relationships, discuss its strength and weakness and discuss their feelings. Patient can be encouraged to contact old friends. The positive steps that the patient takes need to be encouraged. Patient can also be encouraged to visit parties or events. Goals and strategies of different IPT techniques have been shown in Box 6.

Box 6.

Goals and strategies of different interpersonal therapy techniques

COMMON INTERPERSONAL PSYCHOTHERAPY TECHNIQUES

Besides the techniques discussed in specific focus areas targeting depression, we must be aware of the common techniques the therapist must follow while conducting IPT.

Nondirective exploration: In IPT the therapist must present open ended questions to the patient and should not try to direct the questions to get specific answers. This facilitates the discussion and helps in gaining more information about the patient and their circumstances. For example, asking questions like, “Tell me about some of the most important relations of your life”

Direct elicitation: Sometimes, an open-ended question may not stress upon certain areas which need to be clarified and the patient may not express it overtly during the interview. In these cases, the therapist may ask direct questions to elicit some details like asking how exactly the patient felt when husband's dead body was being taken away for funeral

Encouraging expression of affect: Therapist encourages the patient to express their feeling fully and without hesitation. Patients may report that their strong negative feelings are markers of their incompetency in controlling their emotions. The therapist in turn focuses on making the patient understand that emotions are not to be viewed as good or bad. Rather one should focus on proper communication of these emotions. A strong negative emotion can damage an already disturbed relationship. Patient's emotions need to be validated

Clarification: Once the patient brings forward a theme, further clarification helps in making the patient understand about his/her patterns of communication. The therapist may also contradict in between. “You smiled while you described about the way you scolded a very close friend. It doesn’t appear pleasurable at all to me.” The patient can then get an opportunity to reassess their behavior

Communication analysis: The therapist listens to the communication with the patient and then analyses the problems in it. One has to look for the discrepancy between what patient is speaking and what they actually feel. It may not only help in identifying problems but also help in finding reasons for it and ways to deal with it

Decision analysis: This helps patient to explore other available options and decide a course of action. This instills problem solving skills and can be used in any IP area. Like, asking patients if they have considered all options and do they feel there is an alternative solution

Role play: It is used in all the focus areas. An initial rehearsal with the therapist can prepare the patient to deal effectively the real-life situation.

Other indications

IPT although developed for depression can be used in other disorders as well. Other indications of IPT are shown in Box 7.

Box 7.

Indications of interpersonal therapy

| Major depressive disorder in special populations |

| Other mood disorders (dysthymia and bipolar affective disorder) |

| Other psychiatric disorders |

| Anxiety disorders (social phobia) |

| Trauma and stress-related disorders |

| Eating disorders |

| BPD |

| SUDs |

BPD – Borderline personality disorder, SUDs – Substance use disorders

ADAPTATIONS FOR DEPRESSION IN SPECIAL POPULATIONS

Peripartum and postpartum depression

Depression occurring during pregnancy is referred to as peripartum depression. Postpartum depression is characterized by the onset of depressive symptoms within 4 weeks of delivery. About 8%–11% of females experience depression during pregnancy and about 6%–13% experience it in the postpartum period.[8] Evidence supports the beneficial effects of IPT in combating depression during this crucial time period.[9]

No major adaptations are required from routine IPT.[1,6] Some important considerations include:

Differentiating the symptoms of depression from that of pregnancy

Obtaining detailed pregnancy history including planned pregnancy and health status of the fetus

Having a flexible schedule as some adjustments may be required.

Grief may occur following a miscarriage. Difficulties in role transition may occur after shifting of role from an independent person to a mother with responsibilities and restrictions in previous lifestyle. Role disputes occur when patients feel tired or feel that no one else is sharing the responsibilities of the child despite it being a planned pregnancy. During pregnancy, the female may require extra care and help which might be lacking, leading to IP deficits.

Depression in children and adolescents

Depression leads to significant distress and dysfunction including academic dysfunction, suicide, missed school days, and substance abuse in children and adolescents. It often goes unnoticed. IPT can be delivered to adolescents and children, which has been found to be effective in reducing the depressive symptoms.[10] In addition, with the controversial role of antidepressants in increasing suicidal ideation, IPT provides options for dealing with the symptoms without pharmacological agents. Depression in this age group may present with atypical features such as irritability instead of pervasive low mood and increased sleep and appetite. Various studies have found IPT to be effective in adolescents with depression. Different researchers have used different adaptations such as delivering in groups or in school-based clinics. The basic structure and framework of IPT remains same with some adaptations. Some expected adaptations would include ability to communicate well with those in this age group and flexibility so as to adjust with the school schedule. Telephonic sessions should also be considered as an option. The sick role allotted to the child should not be used as a reason to miss classes or extracurricular activities. It is advisable to involve parents in the sessions as they can help in facilitating the therapy. Collateral information from teachers, friends, and caretakers should also be obtained. If the problem areas are centered on the school settings, it is beneficial to obtain information from the teachers as well. This should be done only after taking consent from the patient. For obtaining information about support system and IP context, a visual closeness circle can give more clarity to the patient about what is being asked and can provide more clarity to the therapist. Special issues including substance use, suicidal risk, learning disabilities, and school absenteeism need to be considered.[1,6]

Depression in the elderly

The basic structure of IPT remains same in managing elderly depression. Some adaptations may be required according to the belief system of the age group being targeted. Explaining depression using a medical model seems more relatable. In addition, obtaining information about IP context may be difficult and focus should be on the current important relationships. Besides depressive symptoms, cognitive impairment can also be a problem in elderly patients and often they present with both the symptoms.[1,6] Some adaptations can be made if cognitive disturbances are being targeted.

Format of IPT: The patient as well as the caregiver needs to be involved. Sessions can be taken individually with patient and if this is difficult, with the caregiver as well. It is important to hold problem-solving sessions jointly with both the patient and the caregiver

Focus: Focus of IPT would be depressive as well cognitive disturbances

Duration: Weekly sessions are preferred. A detailed assessment for cognitive impairment must be done. Adequate spacing of visits eases out the therapy.

ADAPTATIONS FOR OTHER MOOD DISORDERS

Dysthymia

In dysthymia, symptoms remain less severe as compared to depression and never reach up to a syndromal level. Patients complain of feeling miserable during their entire life. Duration of 2 years is required to make a diagnosis. Treatment is targeted toward decreasing symptoms which may not be as easy as in cases of acute depression.

Adaptations in IPT for managing dysthymia include the use of iatrogenic role transition as the focus. Unlike the usual framework of IPT, it is difficult to draw a temporal correlation between patient's mood and IP issues due to the long duration of symptoms. Hence, the concept of transition brought about by entering in therapy (iatrogenic transition) is used. Patients start realizing how depressive symptoms interfered with their normal functioning. Gradually, patients learn to handle the IP situations in a positive manner. This builds up their confidence. The remaining structure of IPT remains same.

Bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder is characterized by episodes of depression and mania or hypomania. The characteristic feature is the rhythmicity and disturbances in biological rhythm which paved the path toward the development of IP social rhythm therapy (IPSRT) for managing bipolar disorder.[11] IPSRT sums up IPT with behavioral approach. It was seen that decreased sleep led to the emergence of manic symptoms and thus social rhythm regularization was targeted. Patients fill up a social rhythm metric including activities beginning from the day. This helps in regularizing the daily routine. IPT for depressive phase is delivered in the same manner as for unipolar depression.

ADAPTATIONS FOR NON MOOD DISORDERS

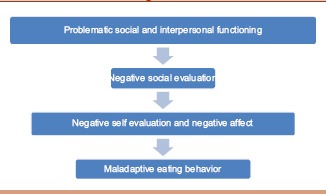

Eating disorders

Disorders included are anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder. The model often proposed for using IPT in eating disorders can be understood by the help of a flowchart as shown in Box 8.[12]

Box 8.

Proposed model for interpersonal therapy in eating disorders

The negative evaluation regarding one's social worth negatively affects the self-worth and esteem of individuals, which triggers eating disorders. IPT has been found to be useful in eating disorders to restore weight. There are mixed results, with a few studies showing positive outcome for IPT in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa.[13,14] Some studies have found CBT to be superior to IPT at the treatment end, but 8-month and 1-year follow-up showed equal results.[15]

Adaptations include providing sick role, restricting discussions, and redirecting them back to difficulties in IP relationships as a cause for eating disorders rather than discussing about eating and body image. Thus, the focus is always centered on the social and IP context and related affective disturbances. The area of IP deficits is also addressed differently in eating disorders. Rather than initiating new relations as in managing depression, focus is on building satisfying relationships. The IPT model for eating disorders views symptoms as chronic and interrelated to IP issues which, in turn, act as triggers to maintain maladaptive eating habits. The therapist tries to draw a time line for the patient linking the IP events with the symptoms of eating disorder. This helps to explain the patient how faulty eating habits are initiated and maintained. The overall structure almost remains same as in IPT for depression. Still, the role of IPT in eating disorders is not backed up by robust evidence. CBT still remains most effective. It may be a valuable option, but results are slow to achieve.

Anxiety disorders

Anxiety disorders and symptoms are often comorbid with depression, and this has formed the background for exploring its role in anxiety spectrum disorders such as social anxiety disorder and panic disorder. Recent evidence comes from a meta-analysis which supports its efficacy for anxiety spectrum disorders.[16] Significant changes and adaptations are not required as the core concept of problem areas links IP problem areas to symptom overlap between depression and anxiety disorders. Hence, the same approach as in depression can be used without significant modifications. The positive outcomes seen in previous studies encourage the use of IPT in these disorders but require more exploration for recommendations as first-line therapy. Significant modifications have not been suggested and exploration for other anxiety disorders is yet in a preliminary stage. CBT has shown to be more effective as compared to IPT in social anxiety disorder.[17]

Trauma and stress-related disorders

IPT is conceptualized to work in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as initially it was considered to an anxiety spectrum disorder with the underlying role of stress diathesis model in the emergence and maintenance of symptoms. With changes in the DSM-5, the category has now been shifted to trauma and stress-related disorders. The other accompanying disorder is adjustment disorder. The focus is not on the memories and traumatic events but on the impact it has had on the social and IP functioning of the patient. Some evidence of its efficacy in PTSD exists.[18] IPT also helps in managing the comorbid depression. Adaptations made target the resulting negative emotions where the patient finds the world untrustworthy. The therapist helps the patient in handling his/her string of negative emotions. The initial half of the therapy focuses on this aspect. Once the patients are able to handle their emotions better, they can eventually handle their interrelationships better. In IPT, it is not required that the patients rethink of their traumatic events. Adjustment disorders are also responses to stressors, but the diagnostic threshold of depression is not met. The basic structure and model of IPT remains same as in depression.

Borderline personality disorder

IPT has not been well researched for personality disorders. Either the trials have been conducted on patients with comorbid mood disorders or have been confounded by small sample size and medication use. The focus of therapy is the IP crisis that these patients go through.[19] Therapy focuses on explaining the associations between mood and IP circumstances. Initial sessions are targeted toward building therapeutic alliance and preparing a formulation. Telephonic conversations can be held in between for keeping a check on the patients. Another important aspect is monitoring patients for suicidality, commonly seen in patients with BPD.[1,6]

Substance use disorders

Substance use disorders (SUDs) have a significant impact on the IP and social relationships of the patients. However, IPT does not seem to benefit the patients with SUD much. There is limited evidence to support its use in this subset of patients. However, once patients are out of their withdrawal and are not experiencing craving, IPT may be initiated for handling social and IP issues. The research findings in support of this still remain scanty and can be an area of further research.

Limitations

The evidence for the use of IPT in SUDs and anxiety disorders is not robust at the moment. It should not be used in psychotic depression or other psychotic disorders. Adequate training is required for the therapist. The patient must be willing for change and understand his/her role in the underlying problem areas. Like any other psychotherapy, some understanding of the IP aspects of relationships and psychological sophistication is required in IPT. Although IPT has been used in various other disorders, the underlying principles and techniques for the same have not been adequately and unanimously described as for depression.

Thus, IPT is an evidence-based therapy for depression, which can improve outcomes in the patients. IPT can be adapted for a wide range of conditions where interpersonnel problems exist. It has also been explored for other mood disorders and anxiety disorders with promising results. Modifications have also been made for delivery by nonmental health professionals such as medical nurses. It is delivered in a time-limited fashion and focuses on the current issues with IP functioning. It can be delivered as an individual therapy or in groups or to couples.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weissman MM, Markowitz JC, Klerman GL. New York: Oxford University Press; 2018. The Guide to Interpersonal Psychotherapy. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guynn RW. Psychotherapies: Interpersonal psychotherapy. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P, editors. Kaplan & Sadock's Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2017. pp. 2775–85. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lipsitz JD, Markowitz JC. Mechanisms of change in interpersonal therapy (IPT) Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33:1134–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Markowitz JC, Weissman MM. Interpersonal psychotherapy: Past, present and future. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2012;19:99–105. doi: 10.1002/cpp.1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Markowitz JC, Weissman MM. Interpersonal psychotherapy: Principles and applications. World Psychiatry. 2004;3:136–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Markowitz JC, Weissman MM, editors. Casebook of Interpersonal Psychotherapy. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cuijpers P, Geraedts AS, van Oppen P, Andersson G, Markowitz JC, van Straten A. Interpersonal psychotherapy for depression: A meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:581–92. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10101411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miniati M, Callari A, Calugi S, Rucci P, Savino M, Mauri M, et al. Interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression: A systematic review. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2014;17:257–68. doi: 10.1007/s00737-014-0442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Hara MW, Stuart S, Gorman LL, Wenzel A. Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:1039–45. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.11.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mufson L, Dorta KP, Wickramaratne P, Nomura Y, Olfson M, Weissman MM. A randomized effectiveness trial of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:577–84. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.6.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frank E, Maggi L, Miniati M, Benvenuti A. The rationale for combining interpersonal and social rhythm therapy (IPSRT) and pharmacotherapy for the treatment of bipolar disorders. Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2009;6:63–74. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rieger E, Van Buren DJ, Bishop M, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Welch R, Wilfley DE. An eating disorder-specific model of interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT-ED): Causal pathways and treatment implications. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:400–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murphy R, Straebler S, Basden S, Cooper Z, Fairburn CG. Interpersonal psychotherapy for eating disorders. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2012;19:150–8. doi: 10.1002/cpp.1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kass AE, Kolko RP, Wilfley DE. Psychological treatments for eating disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2013;26:549–55. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328365a30e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agras WS, Walsh T, Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, Kraemer HC. A multicenter comparison of cognitive-behavioral therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy for bulimia nervosa. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:459–66. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.5.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cuijpers P, Donker T, Weissman MM, Ravitz P, Cristea IA. Interpersonal psychotherapy for mental health problems: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:680–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15091141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stangier U, Schramm E, Heidenreich T, Berger M, Clark DM. Cognitive therapy vs. interpersonal psychotherapy in social anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:692–700. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Markowitz JC, Petkova E, Neria Y, Van Meter PE, Zhao Y, Hembree E, et al. Is exposure necessary? A randomized clinical trial of interpersonal psychotherapy for PTSD. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172:430–40. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14070908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Markowitz JC, Bleiberg K, Pessin H, Skodol AE. Adapting interpersonal psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder. J Ment Health. 2007;16:103–16. [Google Scholar]