Abstract

Introduction:

Dermatophytosis is a fungal infection of the skin, hair, and nails. In the past several years, it has emerged as a general public health problem in our country. Studies from different regions reveal varying patterns of etiological distribution of the disease.

Aims and Objectives:

To estimate the prevalence of different fungal species associated with dermatophytosis and to find out any possible association of the type of fungus with different clinical parameters of the disease.

Materials and Methods:

This was a cross-sectional study among 311 clinically diagnosed dermatophytosis cases from a tertiary care center in eastern India. Potassium hydroxide (KOH) mount and fungal culture were done from samples of skin, hair, and nails, and various clinical parameters were analyzed.

Results:

There was a male preponderance among cases and maximum patients belonged to third decade of life. Most common presentation was tinea corporis et cruris (39.5%). Family history was positive in 48.8% of cases. Trichophyton mentagrophytes was the most common fungal species (79.91%) grown in culture followed by Trichophyton rubrum (13.53%). Majority of patients had a mild body surface area involvement. We did not find statistically significant association of any clinical parameters with type of organism isolated.

Conclusion:

Trichophyton mentagrophytes was the most common isolated fungal species. This is in contrast to several studies where T.rubrum was the frequently found organism. There was no significant association of any clinical parameters like body surface area, number of sites, or duration of diseasewith fungal species isolated in culture.

Keywords: Clinico-mycology, culture, dermatophytosis, KOH

Introduction

Dermatophytosis is a superficial fungal infection with an affinity for keratin-rich structures such as skin, hair, and nails. This disease is predominantly caused by Arthrodermataceae family that contains ~40 species divided among three different genera, i.e., Trichophyton, Epidermophyton, and Microsporum. The nature of predominant species of fungus causing dermatophytosis differs from region to region. An epidemiological transformation of the disease has been observed over last 5–6 years.[1] On literature search, we were unable to find any such study from Eastern India. This study was carried out to explore clinicomycological pattern of dermatophytosis from a tertiary care center in Eastern India.

Aims and Objectives

To estimate the prevalence of different fungal species associated with dermatophytosis

To find out possible association of different clinical parameters with fungal species, if any.

Materials and Methods

Study design

A hospital-based cross-sectional study was carried out in a tertiary care center from January 2018 to June 2018.

Inclusion criteria

All patients with a clinical diagnosis of dermatophytosis were included in the study.

Sample size

Considering the prevalence of the disease about 60 patients/week, the sample size was calculated to be 292 for a 95% confidence interval and 5% margin of error (Raosoft.com, 2014).[2] The study was approved by the research ethical committee of the institute. Exclusion criteria: patients not willing to undergo laboratory tests; patients whose skin scraping samples were negative for both KOH and fungal culture; cultures showing growth other than dermatophytes were excluded from the study.

Methodology

Detailed demographic data and history including age, gender, duration of disease, nature of episode ( first/recurrent), family history, and history of prior treatment (topical and/or systemic) were noted. All patients were thoroughly examined, and different sites of involvement, body surface area involved, associated scalp, and nail involvement, if any, were noted. Body surface area involvement of <1% was considered to be mild, 3%–10% as moderate, and >10% as severe form of disease as adapted from ECTODERM study.[3] The area of outstretched palm from the wrist to the tip of the fingers was considered 1% of the body surface area and was used as a tool to measure the area of involvement.[3] Cases were classified into three groups according to disease duration as <1, 1–3, and >3 months as classified by Agarwal et al.[4]

Sample collection

The suspected area was cleaned with 70% alcohol and allowed to evaporate before collecting the specimen. In case of skin involvement, scrapings were collected from the edge of the lesion, with the blunt end of the sterile surgical blade (No. 15) held at an angle of 90 degrees. In case of hair involvement, scalp scrapings were collected as above and a few of the affected hair strands along with their roots were epilated with the help of forceps. In suspected cases of onychomycosis, nail clippings, and under surface scrapings were collected. In cases of multiple site involvement, sample was collected from the site of maximum activity. Each specimen was divided into two parts: one for KOH mount and another for fungal culture. Direct microscopic examination was done using 10% KOH for skin, 20% for hair, and 40% for nail, and fungal elements were looked for.

Isolation of dermatophyte on culture

The material was then inoculated onto two sets of SDA (Sabouraud's dextrose agar) slope, one with chloramphenicol and cycloheximidine, and the other with only chloramphenicol, and tubes were incubated in biological oxygen demand incubator at 25°C. They were observed for a growth period of 4–6 weeks before labelling it negative.

Species identification

Speciation was done by growth rate, colony morphology, and lactophenol cotton blue mount. Whenever morphological identification was doubtful, slide culture was performed and some biochemical test such as urease test was done.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done using SPSS software version 23 (IBM statistical package for the social sciences IBM SPSS statistics for windows, version 23.0, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). All analysis was done for nonparametric distribution of data. Association between qualitative data was calculated using Chi-square test. Analysis of variance was used to compare means of quantitative data with different types of clinical diagnosis and organisms.

Results

Out of 400 screened patients, 60 patients denied for culture. Overall, 340 met the inclusion criteria and 29 patients were excluded as samples of 8 patients displayed Candida species in culture and 21 patients did not show any fungal elements in KOH mount or any growth in culture medium. Hence, the results of 311 patients were analysed.

Mean age of the patients was 31.35 ± 13.31 years. Maximum number of patients were in the third decade (27.8%). The youngest patient was 1-year old. Males outnumbered females in a ratio of 1.22:1. Age and gender distribution of various cases is given in Table 1. Mean duration of the disease was 4.14 months. Majority of the patients (42.76%) presented with <1 month disease duration. Family history was positive in 48.8% of cases.

Table 1.

Age and gender distribution of various cases

| Age group (in years) | Number, n (%) | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0-10 | 11 (3.5) | 5 | 6 |

| 11-20 | 65 (20.8) | 43 | 22 |

| 21-30 | 87 (27.8) | 47 | 40 |

| 31-40 | 74 (23.6) | 32 | 42 |

| 41-50 | 49 (15.7) | 31 | 18 |

| 51-60 | 21 (6.4) | 12 | 9 |

| 61-70 | 4 (1.3) | 2 | 2 |

About 68 (21.7%) patients gave the history of application of over-the-counter medications containing steroids, 72 (23.1%) patients were on topical antifungal preparations, and 12 (3.85%) gave history of application of indigenous preparations and “preparations containing coal tar, anthralin, salicylic acid.”

Our patients presented with single as well as multiple sites of involvement with dermatophytosis. However, majority of patients (77.17%) presented with multiple site involvement. Most common clinical variant observed was tinea corporis with tinea cruris (39.5%), followed by tinea corporis (27%) andtinea cruris (15.1%). Tinea corporis with tinea manuum, tinea corporis with tinea barbae, and tinea corporis with tinea unguium were seen in one patient each.

Our study revealed a mean body surface area involvement of 3.8%±3.81%. Majority of patients (66.8%) had mild degree of body surface area involvement, whereas 5.4% had a severe degree of body surface area involvement.

KOH mount showed positivity for fungal elements in 304 (97.7%) patients. Thin hyaline branched septate hyphae were seen in 303 cases and chain of arthrospores was found in one case which on culture revealed Trichophyton mentagrophytes.

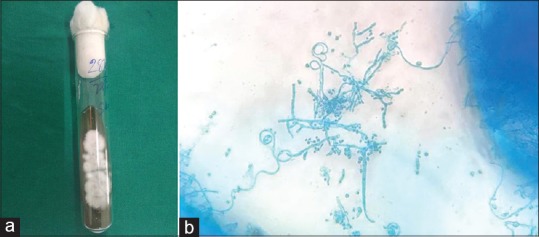

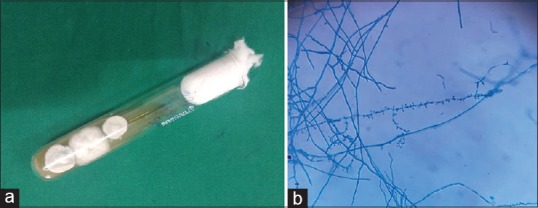

The study showed that 73.63% patients had a positive culture for dermatophyte species. Out of 304 KOH-positive cases, 224 (73.68%) patients yielded positive result for fungal culture. Among the grown organisms, T. mentagrophytes was the most common species isolated (79.91%) [Figure 1a and b], followed by T. nrubrum (13.53%) [Figure 2a and b], T. tonsurans (4.36%), T. verrucosum (0.9%), Epidermophyton floccosum (0.9%), and Microsporum audouinii (0.4%).

Figure 1.

(a) Culture of Trichophyton mentagrophytes on SDA (sabouraud's dextrose agar). (b) Clusters of micro conidia and spiral hyphae of T. mentagrophytes, (lactophenol cotton blue 40×)

Figure 2.

(a) Culture of Trichophyton rubrum on SDA (sabouraud's dextrose agar). (b) Tear drop shaped microconidia of T. rubrum, (lactophenol cotton blue 40×)

The KOH and culture status in different clinical types of dermatophytosis is depicted in Table 2. Among two cases of tinea unguium, T. rubrum was isolated from one and the other did not show any growth on culture.

Table 2.

KOH and culture status in different clinical types of dermatophytosis

| Clinical type | Culture +ve | Culture -ve | KOH +ve | KOH -ve |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tinea corporis | 24 | 60 | 82 | 2 |

| Tinea corporis, Tinea barbae | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Tinea corporis, Tinea cruris | 28 | 95 | 121 | 2 |

| Tinea corporis, Tinea cruris, Tinea barbae | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Tinea corporis, Tinea cruris, Tinea faciei | 4 | 8 | 12 | 0 |

| Tinea corporis, Tinea cruris, Tinea manuum | 4 | 2 | 6 | 0 |

| Tinea corporis, Tinea faciei | 4 | 12 | 16 | 0 |

| Tinea corporis, Tinea manuum | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Tinea corporis, Tinea unguium | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Tinea cruris | 12 | 35 | 45 | 2 |

| Tinea cruris, Tinea faciei | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Tinea faciei | 2 | 9 | 10 | 1 |

| Tinea manuum, Tinea unguium | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Tinea pedis | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| Total | 80 | 231 | 304 | 7 |

The study did not reveal any significant association between the type of organism with body surface area involved (P value = 0.87) and number of sites (P-value = 0.53). Also, there was no significant association between duration of disease and type of organism on statistical analysis (P-value = 0.67). We did not find any association of specific organism among patients either with affected family members or with positive history of topical steroid use. No association was seen between fungal species and the clinical types of tinea.

Discussion

In this study, maximum number of cases of dermatophytosis were noted in the age group of 21–30 years. Similar peak in this age group was observed by Janardan et al., Bhagra et al., Agarwal et al., and Hanumanthappa et al.[4,5,6,7] However, Bindu et al. observed highest peak in second decade.[8] Possible explanation for increase in incidence in this age group is that most of them stay in shared accommodations with lack of proper personal hygiene and sharing of fomites.

Most of the studies including ours show a male preponderance.[5,9,10,11] This part of India lies just south of the Tropic of Cancer and it has a warm climate almost round the year. The average temperature is around 30°C, which reaches nearly 40°C during the summer.[12] According to Panda et al., dermatophytosis is a predominantly tropical dermatosis,[13] so high humidity along with increased outdoor activity exposes males to an environment conducive for the growth of the fungus.

In our study, majority of patients (42.76%) presented with <1 month duration, where as Janardhan et al. observed 17% patients with <1 month disease duration,[5] in contrast to the study by Agarwal et al. and Kumar et al. highest number of patients presented after 3 months of disease.[4,14] With the on-going fungal epidemic, there is an increased awareness about the disease, so many patients present relatively early in the course of the disease.

Positive family history was observed by us in 48.8% cases similar to observation by Ghosh et al. (48%).[15] Bindu et al. nd Vineeta et al. observed a relatively lower value, i.e., 16.6% and 21%, respectively.[8,16] A high number of patients with a positive family history can be explained due to use of common washing machine in family and sharing of fomites.

In our study, 21.7% cases were using over-the-counter (OTC) medications containing steroids, majority of them had taken the medications from the nearby chemist shop without proper consultation. Many authors have observed relatively higher percentage of cases using OTCs,. e.g., Vineeta et al. in 63% cases,[16] Dabas et al. in 77.94% cases[17] and Mahajan et al. in 70.6% cases.[10] Percentage of cases using topical antifungal preparation in our study were 23.1%, whereas it was 5.7%, 47%, and 7.35% in the studies by Mahajan et al., Vineeta et al. and Dabas et al., respectively.[10,16,17] We found 3.85% patients were using indigenous preparations and “preparations containing coal tar, anthralin, salicylic acid” at the time of presentation. Dabas et al. observed 14.7% of cases were on preparations containing salicylic acid, lactic acid, dithranol, coal tar, and urea and 7.35% on topical antifungal therapy.[17] Easy availability of the mixed creams and topical steroid formulations without proper medical consultation could be the reason behind the afore mentioned results. Low cost of the mixed creams and early subsidence of inflammatory symptoms on their use encourages the patients to use the same for prolonged periods.

Majority of our patients presented with multiple site involvement, tinea corporis et cruris being the most common type similar to the results of study by Mahajan et al.[10]

KOH positivity was observed in 97.7% cases; close to the observation made by Janardhan et al.[5] Siddappa et al. reported KOH positivity in all cases.[18] Other authors have observed variable results of KOH positivity such as Sharma et al. 55.21%,[9] Mahajan et al. 79.6%,[10] Manjunath et al. 75.38%, and Poluri et al. 58.18%.[19,20]

About 73.68% of KOH-positive cases yielded positive result for fungal culture similar to the reports by Janardhan et al.[5]; however, Poluri et al. observed a relatively higher value, i.e., 85.9%.[20]

In our study considering culture to be the gold standard method of diagnosis, KOH test was found to be 96.96% sensitive and 20.79% specific. The sensitivity was similar to the result of Mahajan et al. in their study (94.2%); however, a little higher specificity of this test was observed by them (31.8%).[10]

Majority of the studies prior to 2011 show T. rubrum as the most common isolate. According to Ajello, fungal species vary from region to region as well as it may change with passage of time.[10,21]

The most common organism obtained from culture was T. mentagrophytes followed by T. rubrum in this study. Similar results were observed by Agarwal et al. and Mahajan et al.[4,10] T. rubrum was the most common species in majority of studies from South India (Janardhan et al., Aruna et al., Manjunath et al., Ramraj et al.).[5,11,19,22] Sharma et al. observed T. mentagrophytes as the most common type, followed by T. schoenleinii and T. rubrum as least common type accounting for 6.6%.[9] Sardana et al. and Pathania et al. analysed cases of recalcitrant or recurrent dermatophytes and observed T. mentagrophytes as predominant species.[23,24] Since most of the patients in our study have T. mentagrophytes as the causative agent, it could be a menace contemplating the possibility of recurrent or recalcitrant nature of the disease by it. Nenoff et al. did mycological and molecular analysis of 201 patients from various parts of our country and found T. mentagrophytes as the predominant isolate and they also identified a new Indian genotype of this organism (T. mentagrophytes ITS type VIII) responsible for the present epidemic of dermatophytosis.[25] A tabulated comparison of organisms isolated in studies from different regions of India before and after the present fungal epidemic is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of organisms isolated in studies from different regions of India before and after the present fungal epidemic

| Authors | Year | Region | Predominant species isolated (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mahajan et al.[10] | 2017 | North India |

T. mentagrophytes (75.9) T. rubrum (21.9) |

| Malik et al.[26] | 2011-13 | North India |

T. rubrum (58.5) T. mentagrophytes (21.1) |

| Janardhan et al.[5] | 2017 | South India |

T. rubrum (52) T. mentagrophytes (14) |

| Surekha et al.[27] | 2011 | South India |

T. rubrum (64) T. mentagrophytes (20) |

| Agarwal et al.[4] | 2011-12 | Western India |

T. mentagrophytes (37.9) T. rubrum (34.2) |

| Jain et al.[28] | 2008 | Western India |

T. rubrum (66.17) T. mentagrophytes (14.29) |

| Our study | 2018 | East India |

T. mentagrophytes (79.22) T. rubrum (13.4) |

T. mentagrophytes=Trichophyton mentagrophytes; T. rubrum=Trichophyton rubrum

Limitations of Our Study

Patients on antifungal drugs were not excluded from the study and this could result in decreased chance of growth on fungal culture.

Conclusion

There can be a geographical variation in the distribution of species of dermatophytes among patients as evident from studies from different regions of India. Our study showed T. mentagrophytes as the predominant organism to cause dermatophytosis. This is the first such study from Eastern India. An epidemiological shift of type of fungus has been observed by many authors in the epidemic era of dermatophytosis. Previously T. rubrum was most prevalent organism, whereas in this current epidemic, T. mentagrophytes is isolated as the most common species. This may be a possible cause of recurrent and recalcitrant dermatophytosis.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We acknowedge Dr Swati Jain, Dr Sunita Kabi, and Dr Bichitrananda Swain of the Department of Microbiology of this hospital for their contribution.

References

- 1.Poojary S. Epidemiological transformation of dermatophytes in India: Mycological evidence. In: Sardana K, Khurana A, Garg S, Poojary S, editors. IADVL Manual on Management of Dermatophytosis. New Delhi: CBS Publishers; 2018. pp. 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 2. [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 02]. Available from: http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html .

- 3.Rajagopalan M, Inamadar A, Mittal A, Miskeen AK, Srinivas CR, Sardana K, et al. Expert consensus on the management of dermatophytosis in India (ECTODERM India) BMC Dermatol. 2018;18:6. doi: 10.1186/s12895-018-0073-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agarwal US, Saran J, Agarwal P. Clinico-mycological study of dermatophytes in a tertiary care centre in Northwest India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:194. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.129434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janardhan B, Vani G. Clinico mycological study of dermatophytosis. Int J Res Med Sci. 2017;5:31–9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhagra S, Ganju SA, Kanga A, Sharma NL, Guleria RC. Mycological pattern of dermatophytosis in and around Shimla hills. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:268–70. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.131392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanumanthappa H, Sarojini K, Shilpasree P, Muddapur SB. Clinico mycological study of 150 cases of dermatophytosis in a tertiary care hospital in south India. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:322–3. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.97684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bindu V, Pavithran K. Clinico-mycological study of dermatophytosis in Calicut. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2002;68:259–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma R, Adhikari L, Sharma RL. Recurrent dermatophytosis: a rising problem in Sikkim, a Himalayan state of India. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2017;60:541–5. doi: 10.4103/IJPM.IJPM_831_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahajan S, Tilak R, Kaushal SK, Mishra RN, Pandey SS. Clinico-mycological study of dermatophytic infections and their sensitivity to antifungal drugs in a tertiary care center. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017;83:436–40. doi: 10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_519_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aruna GL, Ramalingappa B. A clinico-mycological study of human dfermatophytosis in Chitradurga, Karnataka, India. JMSCR. 2017;5:25743–9. [Google Scholar]

- 12. [Last accessed on 2019 Mar 24]. Available from: https://en.climate-data.org/asia/india/odisha/bhubaneswar-5756/#climate-graph .

- 13.Panda S, Verma S. The menace of dermatophytosis in India: The evidence that we need. Indian J DermatolVenereolLeprol. 2017;83:281–4. doi: 10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_224_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar S, Mallya PS, Kumari P. Clinico-mycological study of dermatophytosis in a tertiary care hospital. Int J Sci Study. 2014;1:27–32. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghosh RR, Ray R, Ghosh TK, Ghosh AP. Clinico-mycological profile of dermatophytosis in a tertiary care hospital in West Bengal, an Indian scenario. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 2014;3:655–66. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vineetha M, Sheeja S, Celine MI, Sadeep MS, Palackal S, Shanimole PE, et al. Profile of dermatophytosis in a tertiary care center. Indian J Dermatol. 2018;63:490–95. doi: 10.4103/ijd.IJD_177_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dabas R, Janney MS, Subramaniyan R, Arora S, Lal VS, Donaparthi N. Use of over-the-counter topical medications in dermatophytosis: A cross-sectional, single-center, pilot study from a tertiary care hospital. Indian J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;4:13–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siddappa K, Mahipal OA. Dermatophytosis in davangere. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1982;48:254–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manjunath M, Mallikarjun K, Dadapeer, Sushma Clinicomycological study of dermatomycosis in a tertiary care hospital. Indian J Microbiol Res. 2016;3:190–3. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poluri LV, Indugula JP, Kondapaneni SL. Clinicomycological study of dermatophytosis in south India. J Lab Physicians. 2015;7:84–9. doi: 10.4103/0974-2727.163135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ajello L. Geographic distribution and prevalence of the dermatophytes. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1960;89:30–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1960.tb20127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramaraj V, Vijayaraman RS, Rangarajan S, Kindo AJ. Incidence and prevalence of dermatophytosis in and around Chennai, Tamilnadu, India. Int J Res Med Sci. 2016;4:695–700. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sardana K, Kaur R, Arora P, Goyal R, Ghunawat S. Is antifungal resistance a cause for treatment failure in dermatophytosis: A study focused on tinea corporis and cruris from a tertiary centre? Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9:90–5. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_137_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pathania S, Rudramurthy SM, Narang T, Saikia UN, Dogra S. A prospective study of the epidemiological and clinical patterns of recurrent dermatophytosis at a tertiary care hospital in India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2018;84:678–84. doi: 10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_645_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nenoff P, Verma SB, Vasani R, Burmester A, Hipler UC, Wittig F, et al. The current Indian epidemic of superficial dermatophytosis due to Trichophyton mentagrophytes–a molecular study. Mycoses. 2018 doi: 10.1111/myc.12878. [E pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malik A, Fatima N, Khan PA. A clinicomycological study of superficial mycosis from a tertiary care hospital of a north Indian town. Virol Mycol. 2014;3:135. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Surekha A, Kumar GR, Sridevi K, Murty DS, Usha G, Bharathi G. Superficial dermatomycoses: A prospective clinico-mycological study. J ClinSci Res. 2015;4:7–15. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jain N, Sharma M, Saxena VN. Clinico-mycological profile of dermatophytosis in Jaipur, Rajasthan. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:274–5. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.41388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]