Abstract

Chondrosarcomas of head and neck region are rare. Very few cases of chondrosarcomas arising in parotid gland have been reported and none with intracranial extension. We report a case of a female presenting with a parotid swelling and a mass in external auditory canal with extradural extension to posterior cranial fossa. With a preoperative fine needle aspiration diagnosis of pleomorphic adenoma, it was excised and the histopathology came out to be low-grade myxoid chondrosarcoma. She has not received any adjuvant chemoradiotherapy and there is no evidence of recurrence at months.

Keywords: ear, nose and throat/otolaryngology; head and neck cancer; head and neck surgery

Background

Chondrosarcomas are considered to be primarily tumours of long bones and pelvis.1 They are not common in head and neck region and accounts for only about 0.1% of head and neck tumours and 10% of all chondrosarcomas.1 In the head and neck region, chondrosarcomas have been reported in mandible, paranasal sinuses, larynx, trachea, temporal bone, nasopharynx, orbit and cervical spine.1 2 Chondrosarcomas, in parotid gland as a primary tumour (either de novo or from a preexisting pleomorphic adenoma) are extremely rare. Only two cases have been reported worldwide.1 We present a case of chondrosarcoma of parotid with extension to lateral skull base and posterior cranial fossa with ipsilateral Lower Moton Neuron (LMN) facial palsy, which would be the third case to be reported and the first with intracranial extension.

Case presentation

A 23-year-old woman presented with sudden increase in size of a swelling in the left parotid region, along with development of facial deviation to the opposite side on smiling or talking, with drooling of water, over a period of 3 months. She also noticed a swelling in the external auditory canal, along with impairment of ipsilateral hearing during this period (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preoperative clinical photograph of patient

The swelling first appeared 5 years ago in the left parotid region, for which she was evaluated elsewhere. It was insidious in onset, painless, gradually progressing over the period. A fine needle aspiration and biopsy done then, showed features of pleomorphic adenoma. She was advised surgery then, but she refused.

Her general examination was within normal limits. Local examination revealed about 4.5×3 cm smooth mass occupying the left infralobular extending to the preauricular region and a smooth pinkish mass in the external auditory canal (figure 1). The overlying skin was healthy other than the preauricular scar mark of previous biopsy. There was left-sided grade IV (House-Brackmann) facial palsy. There was no cervical lymphadenopathy. She did not have any other comorbidities, or familial history of similar disease.

A fine needle aspiration cytology done from both the swellings. The fine needle aspiration cytology from the parotid mass revealed few benign salivary acini against chondromyxoid stroma suggestive of pleomorphic adenoma, but in case of the external auditory canal, it was inconclusive.

Investigations

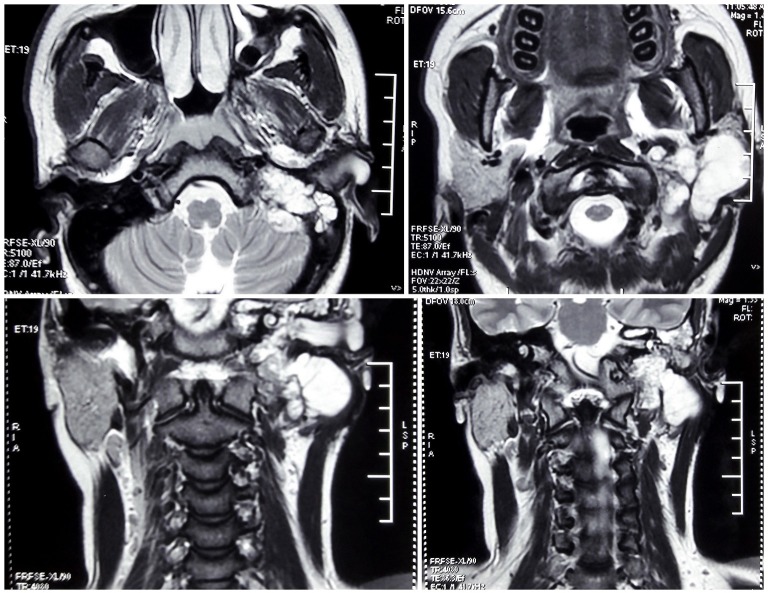

Pure tone audiogram showed a moderately severe conductive hearing loss (13 dB/68 dB) on the left side, and a normal hearing ear on the right side. Contrast-enhanced CT scan of parotid region displayed an isodense mass occupying left parotid, left external auditory canal (EAC) and left mastoid with erosion of anterior bony wall and floor of EAC as well as the mastoid air cells (figure 2). Contrast-enhanced MRI showed a mass, hypointense on T1, hyperintense on T2, with postcontrast enhancement, involving the left parotid region and left external auditory canal causing erosion of temporal bone and mastoid air cells with slight extradural extension to posterior cranial fossa (figure 3). With radiology favouring a malignant rather than benign lesion, an incisional biopsy was performed from the EAC mass which came out to be fibroepithelial polyp.

Figure 2.

Preoperative and postoperative CT.

Figure 3.

Preoperative MRI films (top two—axial sections, bottom two—coronal sections).

Treatment

With informed consent, a lateral skull base approach to surgery was adopted. A neurosurgical consultation was taken prior to surgery as a part of multidisciplinary approach. Radical mastoidectomy was done followed by total radical parotidectomy. Neither the horizontal nor the vertical part of facial nerve could be identified. Tumour was found involving the parotid, external auditory canal and middle ear, while the mastoid antrum and aditus were found uninvolved. A portion of the tumour arising from deep lobe of parotid near mastoid tip was found extending into jugular foramen, which was dissected out. Rest of the tumour in the posterior cranial fossa was removed by trans-labyrinthine approach by the neurosurgeon. The sigmoid sinus and jugular bulb was found to be thrombosed. The internal jugular vein was ligated in the neck while the sigmoid sinus was occluded extraluminally with gelfoam and surgicel proximal to the thrombosed part. The EAC was then closed in a cul-de-sac after packing the mastoid bowl with thigh fat and fascia lata and the wound was closed with placement of a corrugated drain.

Postoperatively patient had severe vertigo, due to labryinthectomy, for the first 6 days which was managed with labyrinthine sedatives. Expectedly left-sided facial palsy persisted. The drain was removed on the fourth postoperative day and she was discharged on the seventh postoperative day. There was no Frey’s syndrome after surgery.

Outcome and follow-up

The final histopathological analysis of the parotid mass showed an infiltrating tumour comprising of lobules of cartilage without significant cellular and nuclear atypia (figure 4). Focal myxoid changes were also noted. The adjacent salivary gland parenchyma showed an atrophic change. No epithelial component identified. On immunohistochemistry, the tumour cells were negative for p63. The tumour was infiltrating into the surrounding bony structures. The diagnosis of low-grade myxoid chondrosarcoma was rendered and the mass from the middle ear found to be consistent with low-grade myxoid chondrosarcoma. Histopathology of EAC polyp showed features of fibroepithelial polyp.

Figure 4.

Postoperative histopathology picture of the tumour showing low grade myxoid xhondrosarcoma.

She has not received any adjuvant chemoradiotherapy and there is no sign of recurrence at 18 months postoperatively

Discussion

Chondrosarcomas primarily are neoplasms of bone. Chondrosarcomas arising in soft tissues probably do so from the cartilaginous differentiation of primitive mesenchymal cells.2 Chondrosarcomas arising in parotid are very rare. Only two such previous cases have been reported.1 3 But none of the previous cases had such intracranial extension or extension into the middle ear as in our case. Chondrosarcomas of the head and neck account for about 10% of all chondrosarcomas and most occur in an age range of 30–60 years2–7 The male:female ratio is reported to vary from 1:1 to 2:1. Chondrosarcomas arising in soft tissues occur more frequently among men and patients older than 50 years of age,2 unlike our case who was a young female. Occurring mostly spontaneously, they have been reported to occur in association with benign conditions, such as Paget’s disease and fibrous dysplasia, as well as malignant conditions such as melanoma, fibrosarcoma and leukaemia.2 As a rule, chondrosarcomas are locally invasive and rarely metastasize, causing injury through compression and invasion of critical structures within the skull base, including the cranial nerves and the carotid artery.8

Radiographically, chondrosarcomas present with bony scalloping, contrast enhancement or matrix calcification on CT. On MRI, there is typically T1 hypointensity, T2 hyperintensity and postcontrast enhancement9 as was seen in our case. However, there was a lack of the characteristic whorls or soap-bubble like appearance seen on T2-weighted and T1 postcontrast9 in our case. Histologically, these tumours demonstrate a hyaline cartilage neoplasm with mild to moderate cellularity, areas of myxoid change and focal host bone entrapment.9

Clinical behaviour of these tumours is largely dependent on location and histological grading1 with high-grade tumours more likely to show local invasion and metastasis. The disease-specific survival of chondrosarcoma of the head and neck region was 87.2% at 5 years and 70.6% at 10 years,2 which was unexpectedly higher, given the anatomical constraints of the region, which makes surgical clearance of the tumour difficult. Surgical excision is widely accepted as the treatment of choice for chondrosarcomas of the head and neck. The common postoperative complications include facial nerve weakness, salivary fistula/sialocele, wound infection, haematoma and Frey’s syndrome.10 The efficacy of adjuvant radiotherapy is unclear with most of literature suggesting it to be ineffective.2 8 Radiotherapy is reserved for tumours with poor prognostic variables, such as high-grade, myxoid or mesenchymal subtype, and positive surgical margins.2

Our case is unique, as very few cases of chondrosarcomas arising in parotid have been reported, but none with extension to middle ear or posterior cranial fossa. Additionally, the intracranial extension was uniquely through the jugular foramen with secondary thrombosis of sigmoid sinus and jugular bulb and that the intratemporal part of facial nerve was unidentifiable, possibly completely involved by tumour. Questions may be raised regarding the primary site of origin of tumour, particularly in the view of radiological erosion of anterior wall and floor of EAC, but the sequence of presentation, as well as the fact that the mass within the EAC was non-malignant probably points to the parotid being the site of origin. The tumour could have arisen from the pre-existing pleomorphic adenoma or could have a completely separate origin within the parotid. The fact that preoperative fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) as well as incisional biopsy pointed to a benign lesion made the preoperative diagnosis a lot difficult. We approached the tumour as a malignant mass based on radiology performing a wide excision.

Learning points.

Chondrosarcomas, in parotid gland, as a primary tumour (either de novo or from a pre-existing pleomorphic adenoma) are extremely rare.

A diagnosis of malignant tumour of the parotid must be kept in mind, if suspected clinically and radiologically, even when the fine needle aspiration points to a pleomorphic adenoma.

Primary treatment of chondrosarcoma of parotid is surgical, with chemoradiation having a very limited role.

Footnotes

Contributors: Conception and design, acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data: SP and SS. Drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content: SP, SS and MNS. Final approval of the version published: SP, SS and PKP. Agreement to be accountable for the article and to ensure that all questions regarding the accuracy or integrity of the article are investigated and resolved: SP, SS, MNS and PKP.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Maruya S, Kurotaki H, Fujita S, et al. Primary chondrosarcoma arising in the parotid gland. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec 2001;63:110–3. 10.1159/000055721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Koch BB, Karnell LH, Hoffman HT, et al. National cancer database report on chondrosarcoma of the head and neck. Head Neck 2000;22:408–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bocklage T. Unusual mesenchymal and mixed tumors of the salivary gland. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1995;119:69–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Burkey BB, Hoffman HT, Baker SR, et al. Chondrosarcoma of the head and neck. Laryngoscope 1990;100:1301–5. 10.1288/00005537-199012000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Evans HL, Ayala AG. Prognostic factors in chondrosarcoma of bone. Cancer 1977;40:818–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arlen M, Tollefsen HR, Huvos AG, et al. Chondrosarcoma of the head and neck. Am J Surg 1970;120:456–60. 10.1016/S0002-9610(70)80006-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Finn DG, Goepfert H, Batsakis JG. Chondrosarcoma of the head and neck. Laryngoscope 1984;94:1539–44. 10.1288/00005537-198412000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lustig LR, Sciubba J, Holliday MJ. Chondrosarcomas of the skull base and temporal bone. J Laryngol Otol 2007;121:725–35. 10.1017/S0022215107006081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Frisch CD, Inwards CY, Lalich IJ, et al. Atypical cartilaginous tumor/chondrosarcoma, grade 1, of the mastoid in three family members: a new entity. Laryngoscope 2016;126:E310–3. 10.1002/lary.25802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Upton DC, McNamar JP, Connor NP, et al. Parotidectomy: ten-year review of 237 cases at a single institution. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery 2007;136:788–92. 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.11.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]