Abstract

Post-traumatic spinal epidural haematoma (SEH) is a rare clinical entity in children. We are reporting the case of an 8-year-old child who presented with thoracolumbar SEH with neurological deficit. MRI confirmed SEH without bony disruption. Emergency evacuation of haematoma was done. There was an improvement in neurological status after removal of haematoma. Diagnosis of this rare condition is tricky in children owing to variable presenting symptoms, especially in an early stage with subtle neurological changes. There should be high clinical suspicion in children with atypical symptoms, and MRI should be done to confirm the diagnosis. Patients with acute neurological deficit should undergo urgent operative decompression. Conservative treatment has a limited role. Patients may be considered for non-operative management if they have medical contraindications, coagulation dysfunction or a small SEH without neurological deficit. These patients require serial MRI monitoring.

Keywords: orthopaedic and trauma surgery, neurological injury, spinal cord, back pain, paediatrics

Background

Spinal epidural haematoma (SEH) is a rare clinical entity that can present with acute neurological deficit. First reported by Jackson in 1869, SEH infrequently occurred following spine fractures and dislocations but rarely found in children.1–3 Cervical spine involvement is seen in cases reported among children.4 It is quite challenging to diagnose SEH in children because of inconsistent clinical symptoms and signs.4 5 We report a rare case of thoracolumbar SEH leading to an acute neurological deficit in a child without bony disruption.

Case presentation

An 8-year-old male child presented to our emergency department with an alleged history of fall 10 days prior while riding a bicycle. After sustaining injury, the patient had pain in the lower back and was able to stand up without any aid. Twelve hours later, the patient complained of increasing pain in the lower back and weakness in bilateral lower limbs. Weakness progressed over the next few days, and the patient was bedridden within a week. The patient had urinary retention and taken to a local hospital and, after that, referred to our hospital. On admission, the patient was conscious, having complete weakness of bilateral lower limbs and sensory loss. On neurological examination, there was a complete loss of power in both lower limbs (1/5 power by Medical Research Council (MRC) grade) and total sensory loss below the D10 level. Bladder and bowel involvement was present.

Investigations

Radiographic screening of the whole spine was performed, and no abnormality was detected. The coagulation profile and complete blood count were within normal limits. Finally, MRI scan was obtained, and it revealed a posterior SEH extending from D10 to L1 (figures 1–3).

Figure 1.

Axial T1-weighted (A) and T2-weighted (B) MRI showing the hyperintense collection in the epidural space and pushing the cord towards the right side and anteriorly.

Figure 2.

Sagittal T1-weighted MRI (A) shows extradural haematoma (hyperintense signal) at the level of D10 to L1 and compression of the spinal cord. Sagittal contrast-enhanced MRI (B) showing peripheral contrast enhancement.

Figure 3.

Axial post-contrast T1-weighted MRI showing peripheral enhancement.

Treatment

After evaluation, an urgent decompression of SEH was planned. Under general anaesthesia and prone positioning, the posterior approach was used. The patient underwent decompressive laminectomy at D11 and D12 levels with evacuation of the haematoma (figure 4). The immediate postoperative period was uneventful. The patient was discharged from the hospital in stable condition.

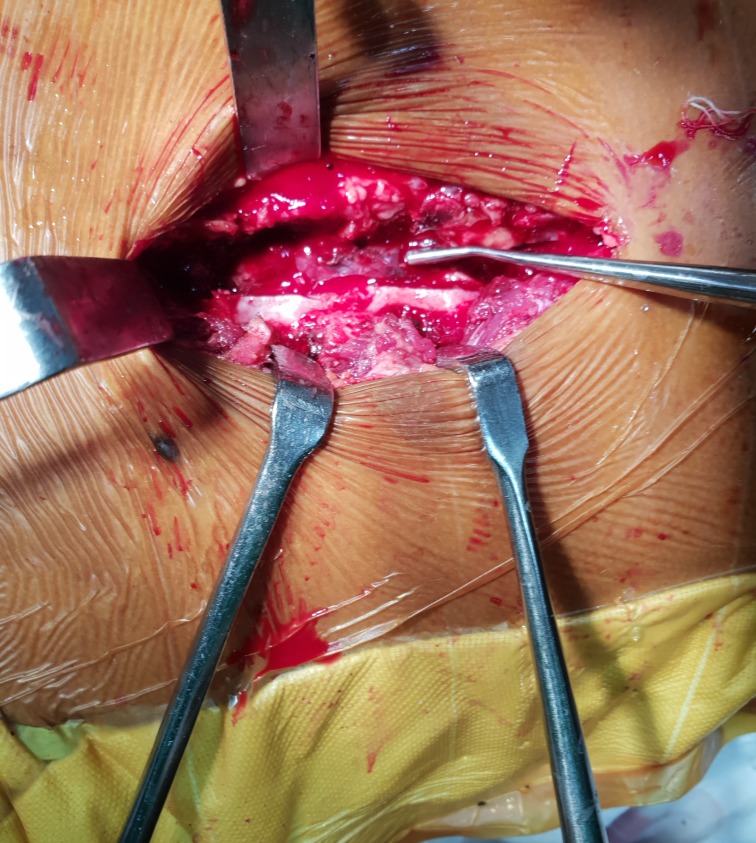

Figure 4.

Photograph showing the laminectomy performed at level D11 and D12 for the evacuation of an epidural haematoma.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient regained bladder and bowel function by 3 weeks postoperatively and was able to stand and walk independently by the end of the third month (5/5 power by MRC grade).

Discussion

SEH is broadly classified into four major types: spontaneous, post-traumatic, idiopathic and secondary to other disorders.6 Spontaneous SEH occurs as a result of straining events or mild exaggeration of physiological events such as coughing, sneezing and defecation. The post-traumatic type occurs either following severe trauma or minor injury without bony disruption. Secondary SEH is attributed to disorders such as hypertension, coagulopathy, alcohol or opioid abuse, and physiological states like pregnancy. SEH also occurs following spine surgery and minor procedures like a lumbar puncture. This classification is more useful in cases with subtle neurological signs as defining the primary cause will prevent recurrent SEH. In our case, the child developed SEH following minor trauma and without bony injury.

The incidence of post-traumatic SEH is between 1% and 1.7% of all spine injuries.7 In children, SEH is infrequent and found at the cervical segment in contrast to adults where it is present at either the cervicothoracic or thoracolumbar region. In our case, it was localised to the thoracolumbar region. Moreover, the thoracolumbar region is prone to neurological deficits because of narrow canal dimensions at this level.

The source of bleed in SEH is believed to be rich epidural venous plexus. The blunt trauma causes a sudden increase in pressure leading to the rupture of these thin-walled valveless vessels.4 8 The greater elasticity of the spinal column in paediatric patients leads to SEH without bony disruption.

The clinical presentation depends on the amount of blood collected, the extent and location of the haematoma.9 Backache, radiculopathy, weakness or sensory loss may be the presenting symptoms.8 Spontaneous recovery rarely happens but has been reported.8 10 11 Initial presentations may vary, leading to delay in diagnosis. Excessive crying, irritability, pain, and stiffness in the neck or back may be the early presentation before neurological deficit in children.9 12 Sometimes it is quite difficult to diagnose SEH because of variable clinical features.

MRI is the modality of choice in the diagnosis of SEH. Whenever there is clinical suspicion, MRI should be done to delineate the location and extent of haematoma and to rule out arteriovenous malformation.9 Coagulation profile is also mandatory to rule out underlying coagulopathy, and it has to be corrected to prevent recurrent SEH, while suspecting SEH following differential diagnosis should be kept in mind like subdural haematoma, abscess and epidural metastasis.8

SEH with neurological deficit is a surgical emergency as early decompression improves the chances of neurological recovery.4 7 8 The surgical decision-making should rely on clinical features, neurological status, MRI features dictating size and location of haematoma, and coagulation profile.6 The operative procedure commonly used is laminectomy. The conservative treatment is limited to some patients who are having subtle clinical features, medical contraindications for surgery and have moderate-size SEH with improving neurological function.8 13

Learning points.

Diagnosing traumatic spinal epidural haematoma in children with subtle clinical findings is quite challenging.

There should be a high index of suspicion with atypical symptoms, and MRI should be done.

Emergent decompression should be done in cases with severe neurological deficit or worsening neurological status.

Conservative management is reserved for selected cases where coagulation dysfunction or medical contraindications rule out urgent surgery. However, serial MRI monitoring is mandatory in such cases.

Footnotes

Contributors: All four authors (SV, AD, VK and SSD) have contributed to and approved of this submitted manuscript. SV is the submitting author.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Parental/guardian consent obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Jackson R. Case of spinal apoplexy. Lancet 1869;94:5–6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)67624-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Watanabe T. Traumatic spinal epidural hematoma without bone disruption. Eur J Pediatr 2006;165:278–9. 10.1007/s00431-005-0038-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pan G, Kulkarni M, MacDougall DJ, et al. Traumatic epidural hematoma of the cervical spine: diagnosis with magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosurg 1988;68:798–801. 10.3171/jns.1988.68.5.0798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kiran NAS, Kasliwal MK, Kale SS, et al. Two children with traumatic thoracic spinal epidural hematoma. J Clin Neurosci 2009;16:1356–8. 10.1016/j.jocn.2009.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fountas KN, Kapsalaki EZ, Robinson JS. Cervical epidural hematoma in children: a rare clinical entity. Case report and review of the literature. Neurosurg Focus 2006;20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Messerer M, Dubourg J, Diabira S, et al. Spinal epidural hematoma: not always an obvious diagnosis. Eur J Emerg Med 2012;19:2–8. 10.1097/MEJ.0b013e328346bfae [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hsieh C-T, Chiang Y-H, Tang C-T, et al. Delayed traumatic thoracic spinal epidural hematoma: a case report and literature review. Am J Emerg Med 2007;25:69–71. 10.1016/j.ajem.2006.05.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ng WH, Lim CCT, Ng PY, et al. Spinal epidural haematoma: MRI-aided diagnosis. J Clin Neurosci 2002;9:92–4. 10.1054/jocn.2001.0918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tarbé de Saint Hardouin A-L, Grévent D, Sainte-Rose C, et al. Traumatic spinal epidural hematoma in a 1-year-old boy. Arch Pédiatrie 2016;23:731–4. 10.1016/j.arcped.2016.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen CJ, Fang W, Chen CM, et al. Spontaneous spinal epidural haematomas with repeated remission and relapse. Neuroradiology 1997;39:737–40. 10.1007/s002340050498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Albayrak S, Atcı IB, Ayden O, et al. Spontaneous regression of traumatic lumbar epidural hematomas. Am J Case Rep 2012;13:258–61. 10.12659/AJCR.883520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schoonjans A-S, De Dooy J, Kenis S, et al. Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma in infancy: review of the literature and the “seventh” case report. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2013;17:537–42. 10.1016/j.ejpn.2013.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. La Rosa G, d'Avella D, Conti A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging-monitored conservative management of traumatic spinal epidural hematomas. Report of four cases. J Neurosurg 1999;91:128–32. 10.3171/spi.1999.91.1.0128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]