Version Changes

Revised. Amendments from Version 1

We have read the reviewers commentaries and want to clarify certain points in this new version: 1. We have removed figure 2 and replaced it by a table (table 2) for better visualization. 2. We have presented the bivariate analysis based on the 3 strata of the main variable and added the missing data in table 3. 3. We have reviewed the literature and expanded the discussion section according to the reviewer's requirements.

Abstract

Background: Irresponsible self-medication is a problem for health systems in developing countries. We aimed to estimate the frequency of self-medication and associated factors in users of drugstores and pharmacies in Peru.

Methods: We performed a secondary data analysis of the 2015 National Survey on User Satisfaction of Health Services (ENSUSALUD), a two-stage probabilistic sample of all regions of Peru. Non self-medication (NSM), responsible self-medication (RSM) and irresponsible self-medication (ISM) were defined as the outcome categories. Demographic, social, cultural and health system variables were included as covariates. We calculated relative prevalence ratios (RPR) with their 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) using crude and adjusted multinomial logistic regression models for complex samples with NSM as the referent category.

Results: 2582 participants were included. The average age was 41.4 years and the frequencies of NSM, RSM and ISM were 25.2%, 23.8% and 51.0%; respectively. The factors associated with RSM were male gender (RPR: 1.35; 95%CI: 1.06-1.72), being between 40 and 59 years old (RPR: 0.53; 95%IC: 0.39-0.72), being 60 or older (RPR: 0.39; 95%IC: 0.25-0.59), not having health insurance (RPR: 1.89; 95%CI: 1.31-2.71) and living in the Highlands region (RPR: 2.27; 95%CI: 1.23-4.21). The factors associated with ISM were male gender (RPR: 1.41; 95%CI: 1.16-1.72), being between 40 and 59 years old (RPR: 0.68; 95%IC: 0.53-0.88), being 60 or older (RPR: 0.65; 95%IC: 0.48-0.88) and not having health insurance (RPR: 2.03; 95%CI: 1.46-2.83).

Conclusion: Around half of the population practiced ISM, which was associated with demographic and health system factors. These outcomes are the preliminary evidence that could contribute to the development of health policies in Peru.

Keywords: Adults, Pharmacies, Self-Medication, Universal Coverage, Insurance, Health Services Accessibility, Peru

Introduction

Self-medication is a practice that represents a public health problem worldwide 1, mainly in developing countries, where it is an important issue for the health systems. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines self-medication as the selection and use of medicines by individuals to treat self-recognized illness or symptoms 2. In addition, the concept of responsible self-medication (RSM) is based on the treatment of diseases and conditions using medicines that do not require a prescription for their sale, due to their safety and effectiveness when correctly used 2. For that reason, there are over the counter (OTC) medicines, which would respond to the concept of RSM 3. To study these behaviors is relevant in developing countries of Latin America.

The frequency of self-medication differs according to the country and context evaluated. Studies have reported self-medication prevalence ranging from 27% to 90.1%. In Asia, a study made in India reported a prevalence of 71% 4, while in Iran it was 35.4% 5. In Europe, research studies in Spain reported a prevalence between 14% and 90.1% 6– 8. In Latin America, Colombian studies presented prevalence ranges from 27.3% to 55.4% 9– 11, whereas in Brazil, it oscillated from 31% to 86.4% 12, 13. In Peru, a previous work found a self-medication prevalence of 56.7% in an urban area of Lima 14. Then, we consider relevant to research the prevalence of self-medication since it has benefits and risks 15.

Self-medication practice can entail suffering serious adverse effects. In addition, the concomitant use of several medicines may develop interactions that could increase those adverse effects 1, 16. Even OTC medicines used inappropriately and irresponsibly can represent a risk for the consumer 1, 15, 17. Among the main benefits of the RSM, we can mention the increased access to pharmaceutical products, the reduction of unnecessary medical appointments, and of the expenses in healthcare services by the government 15. For this reason it is important to evaluate the factors associated with the irresponsible self-medication practice (ISM) 18.

Among the main conditions associated with self-medication practice are demographic, social, cultural, personal and health system factors. Age, sex, socio-economic status and educational level are frequently related to self-medication practice 10. Among the personal factors associated with self-medication are having good results after self-medication, the belief of having experienced manageable similar symptoms previously, the fear of being diagnosed with a serious disease and the need to alleviate symptoms prior using healthcare services 16, 19, 20. Regarding healthcare system, it has been described that self-medication is related to the easy access to medicines in drugstores and pharmacies and the lack of access to healthcare services, which in turn, is associated with the lack of a health insurance 19. Thus, it is proved the multifactorial character of the self-medication practice.

In this context, despite its relevance, we have not found nationwide studies that had evaluate the frequency of self-medication in users of drugstores and pharmacies in Peru. The objective of this study was to estimate the frequency of RSM and ISM, and to identify the factors associated with such practice in a population-based sample.

Methods

Study design

We performed a secondary data analysis using the fourth questionnaire of the National Survey on User Satisfaction of Health Services (ENSUSALUD) of 2015. ENSUSALUD is an annual questionnaire, the first edition was carried out in 2014, and was applied to internal and external users of healthcare facilities. The survey has been executed by the National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (INEI, by its Spanish initials) in collaboration with the National Superintendency of Health (SUSALUD, by its Spanish initials) 21.

ENSUSALUD is composed by six questionnaires, the fourth questionnaire evaluated the drugstores and pharmacies users who were within the perimeter of two blocks around the 181 healthcare facilities that provided health services for the Ministry of Health and Regional Government (MINSA-GR, by its Spanish initials), Social Security System (EsSalud, by its Spanish initials), Health Service of the Armed Forces and Police (FF.AA.PP, by its Spanish initials) and Private Practice (CSP, by its Spanish initials) evaluated in the first and second questionnaires 21. The study was carried out in 179 drugstores and pharmacies in the 25 regions of Peru.

Population, sample and sampling

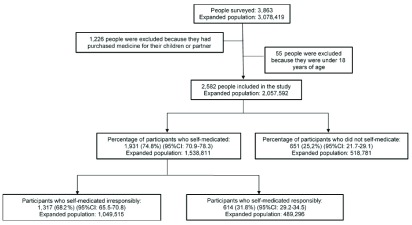

The population was composed of clients of drugstores and pharmacies, who were surveyed after the purchase of a medicine. In total, the fourth questionnaire included 3863 participants. The sample size calculated of 3,863 participants represented an expanded population of 3,078,419 people; participants were not excluded due to lack of data or incomplete records ( Figure 1). The calculation of the sample size used a design effect of 1.2 and a satisfaction possibility of 30% according to the results of the survey ENSUSALUD 2014; assuming a confidence level of 95%. Since our study was a secondary analysis, we calculate the statistical power and the result was 99%.

Figure 1. Flowchart of participants selection, ENSUSALUD 2015.

The sampling was probabilistic, stratified, for each one of the 25 regions of Peru, and two-staged. Drugstores and pharmacies were considered as primary sampling units, while users who went to such establishments were the secondary sampling units.

Eligibility criteria

The fourth questionnaire of ENSUSALUD included people who went and bought a medicine for themselves, their kid(s) or partner in a pharmacy or drugstore close to a health care establishment. For this study, we only included people who have bought medicine for themselves, and this was specified in the question (c4pa): Who did you buy medicine(s) for? Marking the alternative: “for myself”, so the self-medication definition of the WHO was met 2.

We excluded from the analysis the adults that bought medicines for their kid(s) or partner, who has not been able to go to the pharmacy and drugstore, since it was not possible to obtain the sociodemographic data and variables of interest of those people. A total of 1,226 (31.7%) people were excluded since they did not buy medicines for themselves (for their kid or partner). In addition, 55 participants were excluded for being under 18 years old. Finally, a total of 2,582 people were included in the study and they represented an expanded population of 2,057,592 people ( Figure 1). Despite the exclusion of 1,281 (33.2%) participants, the number of participants in the strata of the variables studied did not generated statistical differences.

Variables and measurements

Response variable. We used the question (c4p12): “These medicines, did you buy them with prescription?” to define the response variable. The answers were divided into three options: yes, and showed prescription=1; yes, and did not show prescription =2; no=3. Based on these categories, we created a dichotomous variable called self-medication (yes=1 and no=0), the self-medication category included those participants who bought medicines without doctor’s prescription and those who did not show the prescription when they were surveyed. Additionally, we categorized those participants who had self-medicated in two strata according to the type of medicine they bought (c4p11_1e): RSM (with OTC medicines) and ISM (without using OTC medicines). On the other hand, the non self-medication (NSM) category was composed of participants who bought medicines and showed doctor’s prescription when they were surveyed. Consequently, three final categories were generated (NSM=0; RSM=1; ISM=2).

Exposure variables.

Demographic, social and cultural factors

We included the following variables: sex (c4p3), age (c4p1), language (c4p5), education level (c4p4), current occupation (c4p6), guidance or help for self-medication (c4p21) and geographic region of residency (dominiog).

Factors associated with the Health System

We included the following variables: health insurance affiliation (c4p7), type of health insurance (c4p8) and the request of prescription by the pharmacist when buying the medicine (c4p19).

Ethical considerations

ENSUSALUD 2015 is publicly accessible: http://portal.susalud.gob.pe/blog/base-de-datos-2015/. We downloaded the database without identifiers; thus, the confidentiality of the information given by the participants was guaranteed. Data collection was carried out after the verbal consent of the participants, it did not involve the biological sampling and was conducted for the management of health services nationwide.

Statistical analysis

The database was downloaded from SUSALUD’s website in compatible format with the statistical package STATA ® v14.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA). The database was programmed for a complex sample analysis, the regions of Peru were considered as strata; and drugstores, pharmacies and their users were considered as sampling units. The STATA module “complex survey data” (svy) was used.

The categorical variables were shown as absolute frequencies and as weighted proportions by the complex sampling, with their respective 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). Weighted proportions were calculated which allowed a comparison between the variable’s categories included in the analysis. In this way, we evaluated the association between variables, RSM and ISM practice through Pearson’s chi-squared test corrected for design purposes.

To evaluate the factors associated with RSM and ISM, multinomial logistic regression models were conducted (crude and adjusted) and the complex sampling of the study was considered (svy) 22. NSM was considered as the reference category.

The variables that showed statistically significant association (p<0.05) in the bivariate analysis, were included in the multinomial regression model. Possible collinearity relationships among variables was evaluated to obtain an adequate statistical consistency in the adjusted model. We developed a variable based on health insurance affiliation in participants (c4p7) and the type of health insurance (c4p8). This variable was evaluated in the multinomial regression models (crude and adjusted). The measure of association reported was the relative prevalence ratio (RPR), with their respective 95%CI. Moreover, we elaborated a second multivariate model that included variables whose association with self-medication has been described in the literature. However, this was similar to the first model prepared.

Results

General description of the population

We found that 57.4% participants were women, the average age was 41.4, 96.7% of the respondents spoke Spanish and only 25.3% of the participants had university education. Likewise, 69.4% of the respondents were affiliated to a health insurance, of which more than half were covered by the Comprehensive Health Insurance (SIS, by its Spanish initials) (52.8%) and EsSalud (40.0%).

The prevalence of NSM, RSM, and ISM was 25.2%, 23.8%, and 51.0% respectively. Only 27.7% of the participants were asked for their prescription by the pharmacist when buying the medicine. Furthermore, 54.6% of the participants received guidance or help by the drugstore or pharmacy personnel to self-medicate, and 13.1% of the participants resided in Lima ( Table 1).

Table 1. General characteristics of drugstores and pharmacies users, ENSUSALUD 2015 (N=2,057,592; n=2,582).

| Characteristics | Absolute frequency of

users surveyed |

Weighted proportion of each category * | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | (95%CI) | |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 1,481 | 57.4 | (55.2-59.5) |

| Male | 1,101 | 42.6 | (40.5-44.8) |

| Age | |||

| Average (95%CI) | 41.4 (40.3-42.4) | ||

| 18 to 39 | 1,350 | 52.3 | (49.2-55.4) |

| 40 to 59 | 808 | 31.3 | (29.1-33.6) |

| 60 and older | 424 | 16.4 | (14.4-18.7) |

| Language | |||

| Spanish | 2,498 | 96.7 | (94.7-98.0) |

| Quechua/Other | 84 | 3.3 | (2.0-5.3) |

| Education level | |||

| University education § | 653 | 25.3 | (22.2-28.7) |

| Non-university higher education § | 534 | 20.7 | (18.6-22.9) |

| High school § | 974 | 37.8 | (34.8-40.8) |

| Complete elementary education or below | 419 | 16.2 | (14.0-18.8) |

| Current occupation | |||

| Dependent employee | 659 | 25.5 | (23.1-28.1) |

| Independent worker | 958 | 37.1 | (34.4-40.0) |

| Student | 206 | 8.0 | (6.8-9.4) |

| Housewife | 591 | 22.9 | (20.6-25.3) |

| Unemployed | 109 | 4.2 | (3.0-5.9) |

| Other | 59 | 2.3 | (1.6-3.4) |

| Health insurance | |||

| Yes | 1,792 | 69.4 | (66.1-72.5) |

| No | 790 | 30.6 | (27.5-33.9) |

| Type of health insurance & | |||

| Comprehensive Health Insurance (SIS) | 947 | 52.8 | (47.2-58.5) |

| Social Security System (EsSalud) | 717 | 40.0 | (35.0-45.3) |

| Health Promoting Entities (EPS) | 25 | 1.4 | (0.8-2.3) |

| Health Insurance from Private Companies | 30 | 1.7 | (1.1-2.5) |

| Health Insurance from Private Clinics | 13 | 0.7 | (0.2-2.2) |

| College student health insurance | 12 | 0.7 | (0.3-1.4) |

| FF.AA.PP. Insurance | 47 | 2.6 | (1.8-3.8) |

| Other | 1 | 0.1 | (0.01-0.4) |

| Self-medication | |||

| No | 651 | 25.2 | (21.7-29.1) |

| Responsible | 614 | 23.8 | (21.5-26.2) |

| Irresponsible | 1,317 | 51.0 | (47.8-54.2) |

|

Request of prescription by the pharmacist when

medicine was sold |

|||

| Yes | 714 | 27,7 | (23,9-31,7) |

| No | 1,868 | 72.3 | (68,3-76,1) |

| Guidance or help for self-medication | |||

| Not applicable/not needed/other | 370 | 14.3 | (11.6-17.5) |

| Pharmacists | 1,410 | 54.6 | (49.6-59.5) |

| Radio/Newspapers or Magazines/Television | 610 | 23.6 | (19.8-27.9) |

| Internet | 192 | 7.4 | (5.9-9.4) |

| Geographic region of residency | |||

| Metropolitan Lima | 338 | 13.1 | (8.5-19.6) |

| Other areas of Coast region | 727 | 28.2 | (21.2-36.3) |

| Highlands | 1,070 | 41.4 | (33.1-50.2) |

| Jungle | 447 | 17.3 | (11.9-24.5) |

* Weight proportions and design effect of complex survey sampling were included.

§ Refers to complete or incomplete university, non-university higher education, or high school education.

& Refers only to users who had health insurance.

Description of drugs purchased by participants

When analyzing the total number of self-medicated users, it was found that the most commonly purchased medicine were non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (24.4%), followed by antibiotics (16.5%) and analgesics/antipyretics/corticoids (16.4%). Also, the types of drugs most commonly purchased by participants who irresponsibly self-medicated were: NSAIDs (24.0%), antibiotics (22.6%) and gastrointestinal drugs (15.3%) ( Table 2).

Table 2. Types of medicine purchased by users who self-medicated (N=1,538,811; n=1,931), self-medicated irresponsibly (N=1,049,515; n=1317) and did not self-medicate (N=518,781; n=651).

| Type of medicine purchased by

participants |

Self-medication

N (%) * |

Irresponsible

self-medication N (%) |

Non self-

medication N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotics | 319 (16.5) | 298 (22.6) | 170 (26.1) |

| NSAIDs | 471 (24.4) | 316 (24.0) | 109 (16.7) |

| Gastrointestinal | 241 (12.5) | 201 (15.3) | 62 (9.5) |

| Analgesics/Antipyretics/Corticoids | 317 (16.4) | 144 (11.0) | 58 (8.9) |

| Antihistamines/Respiratory pathologies | 231 (12.0) | 99 (7.5) | 42 (6.5) |

| Nutritional supplement | 104 (5.4) | 53 (4.0) | 46 (7.1) |

| Cardiac pathologies | 89 (4.6) | 57 (4.3) | 51 (7.8) |

| Antiparasitic/Antiviral/Antimycotic | 64 (3.3) | 55 (4.2) | 21 (3.2) |

| Metabolic disorders | 41 (2.1) | 41 (3.1) | 37 (5.7) |

| Neurological pathologies | 29 (1.5) | 28 (2.1) | 33 (5.1) |

| Other | 25 (1.3) | 25 (1.9) | 22 (3.4) |

* Includes irresponsible and responsible self-medication.

After evaluating the 651 participants who did not self-medicate, it was found that the main drugs purchased by this group were antibiotics (26.1%), NSAIDs (16.7%) and gastrointestinal drugs (9.5%) ( Table 2).

Bivariate analysis

The absolute number of users per category of the variables studied was shown, in addition to the RSM and ISM percentages per each category. The corresponding weighting was considered.

No significant association was found between the practice of self-medication and language. However, there was statistically significant association with sex, age, education level, current occupation, having a health insurance, health insurance type, the request for prescription by the pharmacist when buying the medicine, guidance or help for self-medication, and region of residence ( Table 3).

Table 3. Percentage of responsible and irresponsible self-medication among users of drugstores and pharmacies of ENSUSALUD 2015 (N=2,057,592; n=2,582).

| Characteristics | Absolute

frequency of users per category |

Weighted

proportion of non self- medication according to each category * |

Weighted proportion

of responsible self- medication according to each category * |

Weighted proportion

of irresponsible self- medication according to each category * |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | % | % | p-value † | |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 1,481 | 28.0 | 23.4 | 48.6 | 0.001 |

| Male | 1,101 | 21.5 | 24.3 | 54.2 | |

| Age | |||||

| 18 to 39 | 1,350 | 20.1 | 28.1 | 51.8 | <0.001 |

| 40 to 59 | 808 | 29.5 | 20.4 | 50.1 | |

| 60 and older | 424 | 33.5 | 16.3 | 50.2 | |

| Language | |||||

| Spanish | 2,498 | 25.2 | 23.7 | 51.1 | 0.754 |

| Quechua/Other | 84 | 25.0 | 27.4 | 47.6 | |

| Education level | |||||

| University education § | 653 | 23.0 | 26.5 | 50.5 | 0.044 |

| Non-university higher education § | 534 | 22.4 | 24.0 | 53.6 | |

| High school § | 974 | 25.1 | 22.9 | 52.0 | |

| Complete elementary education

or below |

419 | 32.3 | 21.2 | 46.5 | |

| Current occupation | |||||

| Dependent employee | 659 | 23.6 | 25.3 | 51.1 | <0.001 |

| Independent worker | 958 | 25.0 | 23.6 | 51.4 | |

| Student | 206 | 14.1 | 36.4 | 49.5 | |

| Housewife | 591 | 30.8 | 19.6 | 49.6 | |

| Unemployed | 109 | 28.4 | 20.2 | 51.4 | |

| Other | 59 | 23.7 | 13.6 | 62.7 | |

| Type of medical insurance | |||||

| No | 790 | 17.3 | 25.7 | 57.0 | <0.001 |

| Comprehensive Health

Insurance (SIS) |

947 | 30.4 | 22.9 | 46.7 | |

| Social Security (EsSalud and

EPS) |

742 | 26.6 | 22.9 | 50.5 | |

| Other ** | 103 | 28.2 | 23.3 | 48.5 | |

|

Request of prescription by the

pharmacist when medicine was sold |

|||||

| Yes | 714 | 70.6 | 6.0 | 23.4 | <0.001 |

| No | 1,868 | 7.8 | 30.6 | 61.6 | |

|

Guidance or help for self-

medication |

|||||

| Not applicable/not needed/other | 370 | 38.1 | 18.4 | 43.5 | <0.001 |

| Pharmacists | 1,410 | 25.5 | 20.7 | 53.8 | |

| Radio/Newspapers or

Magazines/Television |

610 | 18.7 | 34.6 | 46.7 | |

| Internet | 192 | 18.7 | 22.4 | 58.9 | |

| Geographic region of residency | |||||

| Metropolitan Lima | 338 | 29.3 | 19.8 | 50.9 | 0.012 |

| Other areas of Coast region | 727 | 28.3 | 18.3 | 53.4 | |

| Highlands | 1,070 | 19.9 | 30.6 | 49.5 | |

| Jungle | 447 | 29.7 | 19.5 | 50.8 |

* Weight proportions and design effect of complex survey sampling were included.

** It included the following categories: Health Insurance from Private Companies, Health Insurance from Private Clinics, College student health insurance, FF.AA.PP. Insurance.

§ Refers to complete or incomplete university, non-university higher education, or high school education.

† It refers to the statistical significance obtained from the comparison of proportions between categories of the variable considering the complex survey sampling.

Multinomial logistic regression analysis

In the crude analysis, there was a greater RSM and ISM frequency in relation to male gender, current occupation (being a student) and not having a health insurance. Living in the Highlands region was associated with a higher frequency of RSM. Likewise, there was less frequency of RSM and ISM in relation to age (40 to 59 years and 60 to older), education level (complete elementary education or below) and current occupation (housewife) ( Table 4).

Table 4. Factors associated with responsible and irresponsible self-medication among users of drugstores and pharmacies, ENSUSALUD 2015 (N=2,057,592; n=2,582).

| Responsible self-medication | Irresponsible self-medication | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Crude Model * | Adjusted Model * | Crude Model * | Adjusted Model * | ||||||||

| RPR | (95%CI) | p-value | RPR | (95%CI) | P-value | RPR | (95%CI) | p-value | RPR | (95%CI) | P-value | |

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Female | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||||

| Male | 1.34 | (1.06-1.70) | 0.015 | 1.35 | (1.06-1.72) | 0.016 | 1.45 | (1.19-1.76) | <0.001 | 1.41 | (1.16-1.72) | 0.001 |

| Age | ||||||||||||

| 18 to 39 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||||

| 40 to 59 | 0.49 | (0.37-0.66) | <0.001 | 0.53 | (0.39-0.72) | <0.001 | 0.66 | (0.51-0.85) | 0.001 | 0.68 | (0.53-0.88) | 0.003 |

| 60 and older | 0.35 | (0.24-0.50) | <0.001 | 0.39 | (0.25-0.59) | <0.001 | 0.58 | (0.43-0.79) | 0.001 | 0.65 | (0.48-0.88) | 0.005 |

| Education level | ||||||||||||

| University

education § |

Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||||

| Non-university

higher education § |

0.92 | (0.66-1.30) | 0.654 | 1.01 | (0.70-1.44) | 0.968 | 1.08 | (0.79-1.49) | 0.625 | 1.16 | (0.84-1.60) | 0.377 |

| High school § | 0.79 | (0.54-1.15) | 0.213 | 1.04 | (0.72-1.51) | 0.836 | 0.94 | (0.70-1.25) | 0.668 | 1.12 | (0.84-1.49) | 0.444 |

| Complete

elementary education or below |

0.57 | (0.37-0.89) | 0.014 | 0.94 | (0.60-1.47) | 0.770 | 0.66 | (0.45-0.96) | 0.028 | 0.92 | (0.64-1.34) | 0.674 |

|

Type of Medical

Insurance |

||||||||||||

| Comprehensive

Health Insurance (SIS) |

Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||||

| No | 1.97 | (1.35-2.87) | 0.001 | 1.89 | (1.31-2.71) | 0.001 | 2.14 | (1.52-3.01) | <0.001 | 2.03 | (1.46-2.83) | <0.001 |

| Social Security

(EsSalud and EPS) |

1.15 | (0.75-1.74) | 0.524 | 1.34 | (0.90-2.00) | 0.150 | 1.24 | (0.85-1.81) | 0.266 | 1.29 | (0.88-1.88) | 0.186 |

| Other ** | 1.10 | (0.58-2.08) | 0.772 | 1.13 | (0.60-2.14) | 0.701 | 1.12 | (0.66-1.92) | 0.670 | 1.05 | (0.61-1.81) | 0.858 |

|

Geographic region

of residency |

||||||||||||

| Metropolitan

Lima |

Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||||

| Other areas of

Coast region |

0.95 | (0.51-1.78) | 0.882 | 1.02 | (0.56-1.86) | 0.937 | 1.08 | (0.59-1.99) | 0.793 | 1.14 | (0.63-2.04) | 0.665 |

| Highlands | 2.27 | (1.22-4.23) | 0.010 | 2.27 | (1.23-4.21) | 0.009 | 1.43 | (0.79-2.61) | 0.239 | 1.48 | (0.82-2.70) | 0.195 |

| Jungle | 0.97 | (0.44-2.11) | 0.932 | 0.98 | (0.45-2.12) | 0.962 | 0.98 | (0.48-2.01) | 0.961 | 1.04 | (0.52-2.09) | 0.914 |

|

Current

Occupation |

Not

included §§ |

Not

included §§ |

||||||||||

| Dependent

employee |

Reference | Reference | ||||||||||

| Independent

worker |

0.87 | (0.62-1.24) | 0.448 | 0.94 | (0.68-1.31) | 0.724 | ||||||

| Student | 2.40 | (1.42-4.07) | 0.001 | 1.62 | (1.00-2.61) | 0.049 | ||||||

| Housewife | 0.59 | 0.42-0.83) | 0.002 | 0.74 | (0.56-0.98) | 0.037 | ||||||

| Unemployed | 0.66 | (0.35-1.25) | 0.200 | 0.83 | (0.49-1.41) | 0.489 | ||||||

| Other | 0.53 | (0.20-1.41) | 0.201 | 1.22 | (0.60-2.48) | 0.590 | ||||||

* A multinomial logistic regression model was performed considering the weighted proportions and design effect of the complex survey sampling.

** It included the following categories: Health Insurance from Private Companies, Health Insurance from Private Clinics, College student health insurance, FF.AA.PP. Insurance.

§ Refers to complete or incomplete university, non-university higher education, or high school education.

§§ Not included in the adjusted model due to collinearity with gender and type of medical insurance.

The factors associated with RSM in the adjusted analysis were male gender (RPR: 1.35; 95%CI: 1.06-1.72), not having health insurance (RPR: 1.89; 95%CI: 1.31-2.71) and living in the Highlands region (RPR: 2.27; 95%CI: 1.23-4.21). On the other hand, the only factors that remained associated with a lower frequency of RSM were being between 40 and 59 years old (RPR: 0.53; 95%IC: 0.39-0.72) and being 60 or older (RPR: 0.39; 95%IC: 0.25-0.59) ( Table 4).

The factors associated with a higher frequency of ISM in the adjusted analysis were male gender (RPR: 1.41; 95%CI: 1.16-1.72) and not having health insurance (RPR: 2.03; 95%CI: 1.46-2.83). Furthermore, the factors that remained associated with a lower frequency of ISM were being between 40 and 59 years old (RPR: 0.68; 95%IC: 0.53-0.88) and being 60 or older (RPR: 0.65; 95%IC: 0.48-0.88) ( Table 4).

Discussion

This study found that three-quarters of the participants self-medicated and one out of two of the total population practiced ISM. Also, two out of three participants who irresponsibly self-medicated were not asked for the corresponding prescription when purchasing the medicine they wanted. The factors associated with increased RSM and ISM practice were male gender and not having health insurance. In addition, living in the Highlands was associated with RSM. On the other hand, being 40 to 59 years old or 60 to older were associated with a lower frequency of RSM and ISM.

Our study showed that the prevalence of self-medication was 74.8%, which was higher than that reported by Faria-Domingues et al. 23 in a systematic review that aimed to assess the prevalence of self-medication in adult population from Brazil. This review found that one-third of the population self-medicates. Likewise, the prevalence in our study was higher than that found by Jerez-Roig et al. 24 in a systematic review that included 28 studies predominantly from Brazil and the United States. Such review showed that the prevalence of self-medication in individuals aged 60 or older was on average 38%, and ranged from 4 to 87%. In our study, the participants were over 18 years old, this may explain the above-average prevalence mentioned in the systematic review of Faria-Domingues et al. 23.

Evidence from previous studies shows that self-medication frequency is higher in low and middle-income countries than in developed countries 20. Variable prevalence rates have been reported in Latin America, Africa and Asia (27%-86.4%) 4, 5, 9– 13, 25. However, percentages ranging from 8% to 14% 1 are reported in developed countries (United Kingdom, Italy, Switzerland, Belgium, Germany, France, United States of America and the United Kingdom). This is due to the fact that in these countries there is an adequate supervision when supplying OTC drugs. Therefore, most of these prevalence’s correspond to the purchase of OTC medicines. It has also been reported that certain types of drugs such as antibiotics and NSAIDs are available as OTC drugs, causing adverse reactions due to misuse 1, 16, 19, 20.

The most requested drugs by the participants were NSAIDs, antibiotics and analgesics/antipyretics/corticoids. A previous study in Peru found that NSAIDs were also the most acquired drugs (30%) 14. On the other hand, in a study carried out in Colombia, the most commonly used drugs were analgesics/antipyretics (44.3%), NSAIDs (36.4%) and antihistamines (8.5%), which goes according to our findings 10. These findings are similar because analgesics/antipyretics/corticoids, NSAIDs, antihistamines, and antibiotics are the most frequently used drugs described in other studies 7, 9, 26– 31 and are used to treat common symptoms that people do not consider sufficient reason to see a doctor; therefore, they tend to self-medicate.

Our study showed that the male gender reported a higher self-medication frequency. However, studies such as those of Jerez-Roig et al. 24 and Lukovic et al. 32 reported that the female gender is associated with a higher prevalence of self-medication practice. Our findings are further supported by the study of Quédraogo et al. 33, who described that the self-medication practice was found to be associated mostly with the male gender in rheumatic diseases. However, this study was only carried out in an urban area; therefore, the results could vary or not be extrapolated at rural or national level, as is the case of our research.

In Peru, a study conducted in a district of Metropolitan Lima by Hermoza-Moquillaza et al. 14 described that self-medication percentage was higher in the male gender. However, this study did not carry out regression models with multiple variables, which would give our study an innovative character because it is a population-based study and includes a multivariate analysis. On the other hand, findings in Peru regarding a lower self-medication prevalence in females can probably be explained by the sexist nature of its society 34. We consider that, in sexist societies, the family structure implies that women are relegated to housekeeping and taking care of children, which, together with the repression from their partner, would reduce their probability to self-medicate and even access to health services. This association could also be explained because men would spend most of their time at work and would not have enough time to go to a health center, having less access to health services 35, 36, so they would resort to the practice of self-medication. Besides, the high prevalence of NSM in women and older adults could be explained due to their poor health status, which would predispose them to use frequently health services and receive a medical prescription. Furthermore, older adults need to acquire several drugs for the best management of their comorbidities 37.

A higher self-medication prevalence was found in participants without health insurance compared to those with SIS. Not having health insurance prevents patient from accessing health services, with the option of self-medicate in drugstores and pharmacies. In this context, some studies have associated the difficulty in obtaining a medical appointment with the self-medication practice, as well as an adverse financial situation 38– 41. However, in some health systems, having a health insurance does not guarantee a lower self-medication prevalence. Thus, no statistically significant differences were found between people who have SIS or EsSalud and the practice of RSM or ISM. This situation could be explained by the fact that those with SIS can easily make an appointment as an outpatient, but they would not have an adequate access to medicines 21. In contrast, the situation with social security is the opposite, people with this insurance can benefit from the adequate supply of medicines under this contributory system. However, making an appointment as an outpatient would represent a more problematic situation compared to people with SIS 42. Both situations would eventually lead to RSM or ISM. A similar case occurs in China, where long waiting times (more than half a day), and an expensive medical care, would lead to a high self-medication prevalence of antibiotics in college students 43. Similarly, in Saudi Arabia, there was a positive association between the difficult access to health services and the self-medication practice of patients in primary care centers 44.

Peru has a fragmented health system, which is divided into two sectors: public and private 45, 46. The public sector is also divided into subsidized or indirect contributory system and direct contributory or social security system. In the public sector, the government provides medical services (SIS) to the population living in poverty through the MINSA-GR establishments. The social security system is intended for citizens with formal employment. It has two subsystems: EsSalud and the private health care providers. Furthermore, the FF.AA.PP have their own health subsystem. Finally, the private sector is divided into the for-profit system (private insurance companies, private clinics) and non-profit system (NGOs) 45, 46. The process of universal health insurance in Peru has begun since 2009 and seeks to ensure that more Peruvians have medical insurance based on an essential plan. However, this process is still being implemented and many citizens do not have health insurance yet 47. This leads to a lack of access to medical services and a high prevalence of ISM in Peru 48, 49.

We found an association between the lack of request for prescription by the pharmacist when purchasing the medicine and self-medication in the bivariate analysis. This situation is evidenced by the inadequate distribution of prescription medicines, as is the case with the OTC sale of antibiotics in Peru, despite the current regulations 14, 50. This situation also occurs in other Latin-American countries such as Chile and Colombia, where there are regulations to prevent the free distribution of antibiotics; however, the results are not evidenced over the years 26, 51. We also observed a small percentage of participants (6%) who were asked for a prescription despite purchasing an OTC medicine. This would reflect a professional malpractice by pharmacists in Peru.

This study has limitations: 1) since it is a secondary analysis of a survey designed to assess user’s satisfaction of health services, it was not necessarily conducted to answer our research question; however, the questionnaire has been designed and validated by the INEI staff; 2) the cross-sectional design of this study does not allow us to establish a causal relationship among the factors associated with self-medication. However, it allows us to find the association and identify the markers that could be used by healthcare managers to carry out future public health interventions 52.

In conclusion, there is a high self-medication frequency in Peru, mostly with medicines that are not authorized for OTC sale. It is important to carry out public health interventions in order to reduce the ISM frequency in Peru. There is also a need for educational reforms aimed at raising awareness of the consequences of this irresponsible practice. Similarly, respective measures should be taken to improve the coverage of universal health insurance, thus preventing people from resorting to ISM due to lack of access to medical services. Finally, efforts should be made to integrate druggists and pharmacists into regulatory entities in order to control OTC and uncontrolled sales of prescription drugs. Self-medication could represent a quick and economical solution for users, but it must be practiced within a responsible context.

Data availability

Underlying data

Data associated with this study is available at National Superintendency of Health ( Superintendencia Nacional de Salud, SUSALUD) website: http://portal.susalud.gob.pe/blog/base-de-datos-2015/

Extended data

Questionnaire analyzed is available online: http://portal.susalud.gob.pe/wp-content/uploads/archivo/encuesta-sat-nac/2015/Cuestionario-4-DIRIGIDA-A-USUARIOS-DE-FARMACIAS-BOTICAS.pdf

Funding Statement

The author(s) declared that no grants were involved in supporting this work.

[version 2; peer review: 2 approved]

References

- 1. Bennadi D: Self-medication: A current challenge. J Basic Clin Pharm. 2014;5(1):19–23. 10.4103/0976-0105.128253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization: The Role of the pharmacist in self-care and self-medication: report of the 4th WHO Consultative Group on the Role of the Pharmacist.The Hague, The Netherlands, 26–28 August 1998.1998. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wazaify M, Shields E, Hughes CM, et al. : Societal perspectives on over-the-counter (OTC) medicines. Fam Pract. 2005;22(2):170–6. 10.1093/fampra/cmh723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Balamurugan E, Ganesh K: Prevalence and pattern of self medication use in coastal regions of South India. Br J Med Pract. 2011;4(3):a428 Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jalilian F, Hazavehei SM, Vahidinia AA, et al. : Prevalence and related factors for choosing self-medication among pharmacies visitors based on health belief model in Hamadan Province, west of Iran. J Res Health Sci. 2013;13(1):81–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jiménez Rubio D, Hernández Quevedo C: [Differences in self-medication in the adult population in Spain according to country of origin]. Gac Sanit. 2010;24(2):116.e1–116.e8. 10.1016/j.gaceta.2009.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Guillem Sáiz P, Francès Bozal F, Gimenez Fernández F, et al. : Estudio sobre Automedicación en Población Universitaria Española. Revista Clí nica de Medicina de Familia. 2010;3(2):99–103. 10.4321/S1699-695X2010000200008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vacas Rodilla E, Castellà Dagà I, Sánchez Giralt M, et al. : [Self-medication and the elderly. The reality of the home medicine cabinet]. Aten Primaria. 2009;41(5):269–74. 10.1016/j.aprim.2008.09.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Peñuela M, dela Espriella A, Escobar E, et al. : Factores socioeconómicos y culturales asociados a la autoformulación en expendios de medicamentos en la ciudad de Barranquilla. Salud Uninorte. 2002;16:30–38. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 10. Machado-Alba JE, Echeverri-Cataño LF, Londoño-Builes MJ, et al. : Social, cultural and economic factors associated with self-medication. Biomedica. 2014;34(4):580–8. 10.7705/biomedica.v34i4.2229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. López JJ, Dennis R, Moscoso SM: [A study of self-medication in a neighborhood in Bogotá]. Rev Salud Publica (Bogota). 2009;11(3):432–42. 10.1590/S0124-00642009000300012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schmid B, Bernal R, Silva NN: Automedicação em adultos de baixa renda no município de São Paulo. Rev Saude Publica. 2010;44(6):1039–45. 10.1590/S0034-89102010000600008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Corrêa da Silva MG, Soares MC, Muccillo-Baisch AL: Self-medication in university students from the city of Rio Grande, Brazil. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):339. 10.1186/1471-2458-12-339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hermoza-Moquillaza R, Loza-Munarriz C, Rodríguez-Hurtado D, et al. : Self-medication en un distrito de Metropolitan Area of Lima, Perú. Rev Med Hered. 2016;27(1):15–21. 10.20453/rmh.v27i1.2779 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hughes CM, McElnay JC, Fleming GF: Benefits and risks of self medication. Drug Saf. 2001;24(14):1027–37. 10.2165/00002018-200124140-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Montastruc JL, Bondon-Guitton E, Abadie D, et al. : Pharmacovigilance, risks and adverse effects of self-medication. Therapie. 2016;71(2):257–62. 10.1016/j.therap.2016.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. James LP, Mayeux PR, Hinson JA: Acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity. Drug Metab Dispos. 2003;31(12):1499–506. 10.1124/dmd.31.12.1499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ocan M, Obuku EA, Bwanga F, et al. : Household antimicrobial self-medication: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the burden, risk factors and outcomes in developing countries. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):742. 10.1186/s12889-015-2109-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sherazi BA, Mahmood KT, Amin F, et al. : Prevalence and Measure of Self Medication: A Review. J Pharm Sci & Res. 2012;4(3):1774–1778. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shaghaghi A, Asadi M, Allahverdipour H: Predictors of Self-Medication Behavior: A Systematic Review. Iran J Public Health. 2014;43(2):136–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mezones-Holguín E, Solis-Cóndor R, Benites-Zapata VA, et al. : Diferencias institucionales en el insuficiente acceso efectivo a medicamentos prescritos en instituciones prestadoras de servicios de salud en Perú: Análisis de la Encuesta Nacional de Satisfacción de Usuarios de los Servicios de Salud (ENSUSALUD 2014). Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2016;33(2):205–14. 10.17843/rpmesp.2016.332.2197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A: Multilevel modelling of complex survey data. J R Statist Soc A. 2006;169(4):805–27. 10.1111/j.1467-985X.2006.00426.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Domingues PH, Galvão TF, Andrade KR, et al. : Prevalence of self-medication in the adult population of Brazil: a systematic review. Rev Saude Publica. 2015;49:36. 10.1590/S0034-8910.2015049005709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jerez-Roig J, Medeiros LF, Silva VA, et al. : Prevalence of self-medication and associated factors in an elderly population: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2014;31(12):883–96. 10.1007/s40266-014-0217-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Donkor ES, Tetteh-Quarcoo PB, Nartey P, et al. : Self-medication practices with antibiotics among tertiary level students in Accra, Ghana: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;9(10):3519–29. 10.3390/ijerph9103519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vacca CP, Niño CY, Reveiz L: [Restriction of antibiotic sales in pharmacies in Bogotá, Colombia: a descriptive study]. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2011;30(6):586–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bertoldi AD, Silveira MP, Menezes AM, et al. : Tracking of medicine use and self-medication from infancy to adolescence: 1993 Pelotas (Brazil) birth cohort study. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51(6 Suppl):S11–S5. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.06.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Grigoryan L, Burgerhof JG, Degener JE, et al. : Determinants of self-medication with antibiotics in Europe: the impact of beliefs, country wealth and the healthcare system. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61(5):1172–9. 10.1093/jac/dkn054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Grigoryan L, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM, Burgerhof JG, et al. : Self-medication with antimicrobial drugs in Europe. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(3):452–9. 10.3201/eid1203.050992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. World Health Organization: Responsible self-care and self-medication; A worldwide review of consumers’ survey. The World Self-Medication Industry.2010. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lam A, Bradley G: Use of self-prescribed nonprescription medications and dietary supplements among assisted living facility residents. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2006;46(5):574–81. 10.1331/1544-3191.46.5.574.Lam [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lukovic JA, Miletic V, Pekmezovic T, et al. : Self-medication practices and risk factors for self-medication among medical students in Belgrade, Serbia. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e114644. 10.1371/journal.pone.0114644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ouédraogo DD, Zabsonré/Tiendrebeogo JW, Zongo E, et al. : Prevalence and factors associated with self-medication in rheumatology in Sub-Saharan Africa. Eur J Rheumatol. 2015;2(2):52–56. 10.5152/eurjrheum.2015.0091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Flake DF: Individual, family, and community risk markers for domestic violence in Peru. Violence Against Women. 2005;11(3):353–73. 10.1177/1077801204272129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dolja-Gore X, Loxton D, D’Este C, et al. : Differences in Use of Government Subsidised Mental Health Services by Men and Women with Psychological Distress: A Study of 229,628 Australians Aged 45 Years and Over. Community Ment Health J. 2018;54(7):1008–18. 10.1007/s10597-018-0262-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Barbosa YO, Menezes LPL, de Jesus Santos JM, et al. : Access of men to primary health care services. Journal of Nursing UFPE/Revista de Enfermagem UFPE. 2018;12(11). 10.5205/1981-8963-v12i11a237446p2897-2905-2018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Morin L, Johnell K, Laroche ML, et al. : The epidemiology of polypharmacy in older adults: register-based prospective cohort study. Clin Epidemiol. 2018;10:289–298. 10.2147/CLEP.S153458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Montastruc JL, Bagheri H, Geraud T, et al. : [Pharmacovigilance of self-medication]. Therapie. 1996;52(2):105–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Giroud JP, Cupillard C, Curé O: Médicaments sans ordonnance: les bons et les mauvais!La Martinière;2011. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fainzang S: L'automédication ou les mirages de l'autonomie. Presses universitaires de France.2015. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fainzang S: The other side of medicalization: self-medicalization and self-medication. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2013;37(3):488–504. 10.1007/s11013-013-9330-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sánchez-Moreno F: [Inequity in health affects the development in Peru]. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2013;30(4):676–82. 10.17843/rpmesp.2013.304.251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhu X, Pan H, Yang Z, et al. : Self-medication practices with antibiotics among Chinese university students. Public Health. 2016;130:78–83. 10.1016/j.puhe.2015.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Alghanim SA: Self-medication practice among patients in a public health care system. East Mediterr Health J. 2011;17(5):409–16. 10.26719/2011.17.5.409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sánchez-Moreno F: [The national health system in Peru]. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2014;31(4):747–53. 10.17843/rpmesp.2014.314.129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Alcalde-Rabanal JE, Lazo-González O, Nigenda G: [The health system of Peru]. Salud Publica Mex. 2011;53 Suppl 2:s243–s54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Benites-Zapata VA, Lozada-Urbano M, Urrunaga-Pastor D, et al. : Factores asociados a la no utilización de los servicios formales de prestación en salud en la población peruana: análisis de la Encuesta Nacional de Hogares (ENAHO) 2015. Revista Peruana de Medicina Experimental y Salud Pública. 2017;34:478–84. 10.17843/rpmesp.2017.343.2864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Eibenschutz C, Valdivia AS, González ST, et al. : Considerations on health reform process (1993-2013) and social participation in Peru. Saúde em Debate. 2014;38(103):872–82. 10.5935/0103-1104.20140077 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wilson L, Velásquez A, Ponce C: La ley marco de aseguramiento universal en salud en el Perú: análisis de beneficios y sistematización del proceso desde su concepción hasta su promulgación. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2009;26(2):207–17. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ecker L, Ruiz J, Vargas M, et al. : [Prevalence of purchase of antibiotics without prescription and antibiotic recommendation practices for children under five years of age in private pharmacies in peri-urban areas of Lima, Peru]. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2016;33(2):215–23. 10.17843/rpmesp.2016.332.2152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bavestrello FL, Cabello MA: [Community antibiotic consumption in Chile, 2000-2008]. Rev Chilena Infectol. 2011;28(2):107–12. 10.4067/S0716-10182011000200001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rothman KJ, Gallacher JE, Hatch EE: Why representativeness should be avoided. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(4):1012–4. 10.1093/ije/dys223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]