Abstract

Deregulated WNT signaling has been shown to favor malignant transformation, tumor progression, and resistance to conventional cancer therapy in a variety of preclinical and clinical settings. Accumulating evidence suggests that aberrant WNT signaling may also subvert cancer immunosurveillance, hence promoting immunoevasion and resistance to multiple immunotherapeutics, including immune checkpoint blockers. Here, we discuss the molecular and cellular mechanisms through which WNT signaling influences cancer immunosurveillance and present potential therapeutic avenues to harness currently available WNT modulators for cancer immunotherapy.

Introduction

The term ‘WNT signaling’ embraces an evolutionary conserved group of signal transduction cascades that play central roles in embryogenesis, tissue homeostasis, wound repair, and malignancy [1]. WNT pathways govern molecular and cellular traits typically associated with stemness and the balance between self-renewal and lineage determination [2]. At the helm of these signaling cascades are WNTs, a panel of secreted cysteine-rich glycoproteins (19 in humans and mice) that operate as morphogens.

Reflecting its central role in the maintenance of organismal homeostasis, aberrant WNT signaling has been etiologically involved in the pathogenesis of a variety of human disorders, including (but not limited to) birth defects, autoimmune conditions, bone diseases, and cancer [3,4]. In particular, a substantial body of work has linked alterations in WNT signaling with oncogenesis, disease progression, and resistance to treatment in a variety of oncological settings [5,6]. Accumulating evidence suggests that aberrant WNT signaling activated by oncogenic mutations mediates protumoral functions not only by endowing transformed cells with malignant features but also by impairing anticancer immunosurveillance [7].

Here, we review the mechanisms whereby WNT signaling impinges on immune functions, with a special emphasis on cancer immunosurveillance, and discuss the therapeutic potential of harnessing currently available WNT modulators to implement cancer immunotherapy.

Molecular Regulation of Canonical WNT Signaling

Soluble WNT proteins mediate their biological effects upon binding to cognate receptors from the Frizzled (FZD) family (10 in humans and mice). Depending on multiple parameters, including (but not limited to) the precise identity of the ligand and the receptor, as well as the presence of a co-receptor, this interaction can initiate one of multiple signal transduction cascades culminating with the activation of transcriptional or post-translational cellular programs [1].

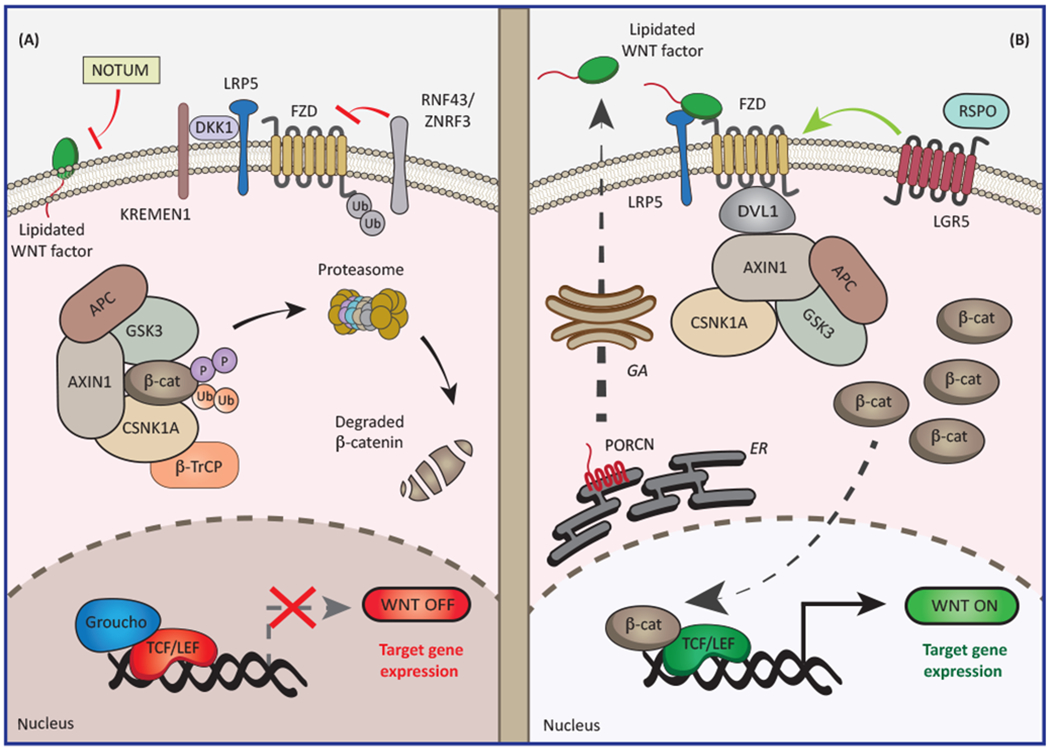

The best characterized of such signal transduction cascades, known as ‘canonical WNT signaling’, relies on the cytoplasmic stabilization and nuclear translocation of the transcriptional regulator catenin beta 1 (CTNNB1; best known as β-catenin) [1] (Figure 1). In the absence of WNT ligands, the intracellular levels of β-catenin are low owing to the constitutive activity of (i) a supramolecular entity commonly known as ‘β-catenin destruction complex’, composed of adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), axin 1 (AXIN1), casein kinase 1 alpha (CSNK1A), and glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3), catalyzing the phosphorylation of β-catenin at its N terminus; and (ii) ‘beta-transducin repeat-containing E3 ubiquitin protein ligase’ (BTRC; best known as β-TrCP) that tags β-catenin for proteasomal degradation upon addition of polyubiquitin chains [8].

Figure 1. Molecular Control of Canonical WNT Signaling.

(A) In the absence of WNT ligands or when the interaction between frizzled (FZD) receptors and low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) is blocked by dickkopf WNT signaling pathway inhibitor 1 (DKK1), cytosolic catenin beta 1 (CTNNB1; best known as β-catenin) is efficiently phosphorylated and ubiquitinated by the so-called β-catenin destruction complex, resulting in efficient proteasomal degradation. In this scenario, transcription factors from the T cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor (TCF/LEF) family are maintained in an inactive state upon binding to transcriptional repressors from the Groucho family. Canonical WNT signaling is counteracted by deacylases such as notum, palmitoleoyl-protein carboxylesterase (NOTUM), which limit the secretion of WNT signals. Also, E3 ubiquitin ligases ring finger protein 43 (RNF43) and zinc and ring finger 3 (ZNRF3) suppress WNT signaling by favoring FZD receptor internalization. (B) WNT ligands secreted upon acylation by porcupine O-acyltransferase (PORCN) enable the assembly of an FZD-LRP5 complex that recruits dishevelled segment polarity protein 1 (DVL1) or DVL2 to the cytosolic face of the plasma membrane. This results in inactivation of the β-catenin destruction complex, accumulation of β-catenin in the cytoplasm and nucleus, displacement of Groucho family members from TCF/LEF transcription factors, and consequent activation of specific transcriptional programs. Conversely, binding of members of the R-spondin (RSPO) protein family to leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptors (LGRs) stimulates WNT-driven signal transduction. APC, adenomatous polyposis coli; AXIN1, axin 1; β-TrCP (official name, BTRC), beta-transducin repeat-containing E3 ubiquitin protein ligase; CSNK1A, casein kinase 1 alpha; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; GA, Golgi apparatus; GSK3, glycogen synthase kinase 3; KREMEN1, kringle-containing transmembrane protein 1.

Binding of a WNT protein to an FZD family member in association with low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) or LRP6, which operate as co-receptors, results in the recruitment of dishevelled segment polarity protein 1 (DVL1) or DVL2 to the cytosolic face of the plasma membrane. In turn, FZD-bound DVL1 recruits AXIN1, enabling β-catenin stabilization [8]. It remains to be elucidated whether the binding of DVL1 to AXIN1 results in the disassembly of the destruction complex, as the classical model proposes [8], or in the blockage of β-catenin ubiquitination as a consequence of saturation of the destruction complex, as some reports suggest [9]. Regardless, in the presence of DNA binding effector proteins, accumulating β-catenin enters the nucleus, where it can operate to influence transcription (for a comprehensive list of WNT-regulated genes, please refer to the Wnt homepage at https://web.stanford.edu/group/nusselab/cgi-bin/wnt/target_genes). The main effectors of β-catenin-dependent transcription are four members of the T cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor (TCF/LEF) family, whose activity can be modulated by corepressors from the Groucho family [10]. Intriguingly, depending upon context, TCF/LEF family members can use β-catenin differently, either in an antagonistic or an agonistic manner [11,12], and recent studies suggest that switches in family members are critical to driving the chromatin dynamics required to elicit fate changes [13,14]. In addition, multiple core components of the canonical WNT signaling cascade are themselves transcriptionally regulated by β-catenin and TCF/LEF proteins, pointing to the existence of a robust feedback control [1].

Several other factors regulate canonical WNT signaling by controlling the availability and functionality of WNT ligands and FZD receptors [1] (Figure 1). For instance, secretion of WNT ligands requires acylation by membrane-bound porcupine O-acyltransferase (PORCN), a post-translational modification that can be reversed by a secreted palmitoleoyl-protein carboxylesterase, NOTUM [15]. WNT activation is also hampered by dickkopf WNT signaling pathway inhibitor 1 (DKK1), a soluble decoy receptor that antagonizes LRP6 in cooperation with kringle-containing transmembrane protein 1 (KREMEN1) or KREMEN2 [16]. Likewise, WNT signaling can be antagonized by members of the family of secreted Frizzled-related proteins (SFRPs) that can bind and sequester WNT factors, despite that WNT-promoting roles have also been reported for these proteins [17]. Furthermore, the transmembrane E3 ubiquitin ligases ring finger protein 43 (RNF43) and zinc and ring finger 3 (ZNRF3) block WNT signaling by favoring FZD receptor internalization and lysosomal degradation [18]. Conversely, members of the R-spondin (RSPO) protein family enhance cellular responsiveness to WNT ligands by stabilizing FZD receptors on the plasma membrane, a mechanism that relies on leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptors (LGRs) [19]. Taken together, these observations exemplify the multiple layers of regulations to which canonical WNT signaling is subjected.

Of note, canonical WNT signaling is highly interconnected with a variety of other signal transduction cascades. These include (but are not limited to) Hippo signaling, whose major effectors Yes associated protein 1 (YAP1) and WW domain containing transcription regulator 1 (WWTR1; best known as TAZ) promote the degradation of β-catenin by the destruction complex [20] and stimulate the secretion of WNT-inhibitory factors [21], as well as Hedgehog signaling, which engages in mutual antagonism with canonical WNT signal transduction in some settings [22]. Moreover, WNT signaling can proceed via ‘non-canonical’ (i.e., β-catenin-independent) mechanisms, such as the planar cell polarity and the WNT-Ca2+ pathways. A comprehensive discussion of non-canonical WNT signal transduction cascades goes beyond the scope of the present review article and can be found elsewhere [4,23,24].

WNT Signaling in Immune System Development and Function

WNT signaling plays a major role in governing cellular homeostasis, including the strict regulation of immune cell development and function. Nevertheless, in contrast to the well-established significance of the WNT pathway in hair follicle and intestinal stem cell biology [2], its contribution to the homeostasis of the pluripotent progenitor cells that are at the root of hematopoiesis, known as hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), has long been matter of debate. For example, defects in several core components of canonical WNT signaling such as PORCN [25] and β-catenin (alone or combined with γ-catenin [26,27]) do not result in overt hematopoietic alterations in mice. Conversely, non-canonical WNT signaling triggered by FZD8 [28] or Wnt family member 5A (WNT5A) [29] inhibits the differentiation of quiescent HSCs by limiting β-catenin activation. Moreover, canonical WNT signaling is subjected to dynamic modulation during hematopoiesis, so that while mild activation of cascade enhances HSC function, the opposite is true for intermediate and exacerbated levels of canonical WNT signaling [30].

In addition, several core components of the molecular machinery for canonical WNT signaling have been proposed to influence HSC fate, as they promote commitment to blood lineages that constitute the hematopoietic tree, mainly T cell lymphopoiesis (Box 1). Hence, enforced canonical WNT signaling (following the expression of a stabilized variant of β-catenin) favors thymocyte differentiation in a variety of rodent models, whereas interruption of the pathway (following the deletion of Ctnnb1 or Tcf7) blocks thymocyte development [31,32]. TCF1, encoded by the Tcf7 gene, mediates such an activity by transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms, de facto enabling activation of T cell specification programs in early thymocyte progenitors [33]. Moreover, TCF1 and LEF1 appear to have intrinsic histone deacetylase enzymatic activity that upholds CD8+ T cell identity by repressing CD4-associated genetic networks [34]. Despite the apparent cooperative interaction of these transcription factors (TFs) during lymphopoiesis, TCF1 represses LEF1 transcription in early thymocytes upon binding to its promoter [12]. That said, most hematopoietic phenotypes that have been suggested to depend on the WNT pathway resulted from the non-physiological overexpression or mutational (in)activation of WNT signaling components, which may not properly recapitulate physiological settings.

Box 1. Regulation of Thymic T Cell Development.

All lymphoid cells (including B cells, T cells, and innate lymphoid cells) derive from so-called ‘common lymphoid progenitors’ (CLPs), a group of non-committed cells that reside in the bone marrow. A subset of such cells commonly referred to as ‘early thymic progenitors’ (ETPs) seeds the thymus in the course of embryonic development to sustain T lymphopoiesis, a stepwise process encompassing sequential phenotypical stages that can be monitored by specific surface markers such as CD4 and CD8. More precisely, early thymic precursors proceed towards the generation of differentiated cells that express either CD4 or CD8 via two major intermediate stages: (i)CD4−CD8− [or double-negative (DN)] and (ii) CD4+CD8+ [or double-positive (DP)]. Additional markers including CD25 and CD44 enable the subdivision of DN cells into four developmental subsets (DN1–DN4).

Of note, differentiating thymocytes migrate to different thymic areas where distinct microenvironmental cues provided by the epithelium regulate the activity of master TFs. In particular, NOTCH signaling driven by stromal delta-like canonical NOTCH ligand 4 (DLL4) in the subcapsular thymic zone dictates the initial commitment of ETPs by driving the expression of TCF1 and GATA3. NOTCH signaling gradually decreases as DN3 thymocytes migrate towards the cortex and start to express an incompletely rearranged version of the TCR (consisting of a rearranged β chain, an α chain precursor, and CD3). This enables proliferation and further differentiation, including the rearrangement of the α chain (β-selection). DP thymocytes expressing a mature TCR with intermediate affinity for self-peptides presented by cortical epithelial thymic cells in the context of MHC molecules progress across the cortex as they receive pro-survival signals (positive selection). This process is coupled with the loss of either CD4 or CD8, reflecting the preferential affinity of the TCR for MHC class I or II molecules, respectively, and culminates with differentiation into CD8+ CTLs or CD4+ TH cells. Finally, as differentiated single-positive thymocytes progress across the cortico-medullary junction to enter the circulation, T cells bearing a TCR with excessive affinity for self-peptides presented by the thymic epithelium undergo apoptotic cell death (negative selection). This process is fundamental for the establishment of central tolerance and hence for the avoidance of autoimmune reactions. Of note, an additional layer of tolerance constantly operates in the periphery. In this setting, autoreactive T cells can either undergo apoptosis as a consequence of chronic TCR signaling or become functionally hyporesponsive upon interaction with tolerogenic antigen-presenting cells. Peripheral tolerance is a major contributor to cancer immunoevasion [149,150].

The role of WNT signaling in immunity goes beyond hematopoiesis and also impinges on the biological features of circulating immune cells, including the regulation of peripheral T cell activation and differentiation (Box 2). Indeed, enforced expression of stabilized β-catenin plus a TCF1 variant (p45) that binds β-catenin favors the generation of central memory T (TCM) cells in response to viral infection, hence improving systemic disease control [35]. Conversely, deletion of Tcf7 from CD8+ T cells prevents the establishment of functional T cell memory to viral infection, resulting in defective responses to viral re-challenge, potentially linked to downregulation of the survival factor BCL2 and limited sensitivity to interleukin 15 (IL-15)-driven proliferation [36,37]. Noteworthy, canonical WNT signaling driven by exogenous WNT3A supplementation or pharmacological glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK3B) inhibition skews CD8+ T cell differentiation upon T cell priming towards a memory stem cell-like state endowed with superior self-renewal and antitumor effector function [38]. Thus, β-catenin-dependent WNT signaling occupies a central position in immune responses to antigenic challenges, including, as discussed below, specific CD8+ T cell-mediated responses to tumor neoantigens.

Box 2. Overview of T Cell Activation and Memory Formation.

Proper T cell activation involves, at least, three consecutive stimulatory signals: (i) TCR activation brought about by specific recognition of the cognate antigen presented in the context of MHC molecules; (ii) secondary signals that are provided by co-stimulatory receptors such as CD28; and (iii) cytokine-dependent control of T cell proliferation and differentiation.

On encountering their cognate antigen, peripheral naïve T cells undergo several marked phenotypic and functional changes that are classically described in the context of three major phases: (i) clonal expansion, in which productive TCR signaling initiates a robust wave of IL-2-driven T cell proliferation coupled with the acquisition of effector functions; (ii) contraction, in which thevast majority of effector T cells produced during clonal expansion succumb to apoptotic cell death as the initiating antigen is eliminated; and (iii) memory formation, in which a small fraction of T cells acquires functional features that enable its persistence for extended periods (up to the entire lifetime) to ensure a prompt response to antigenic re-challenge. Memory T cells are responsible for (or at least contribute to) the prophylactic effects of various vaccines commonly used against infectious agents [151].

Although additional subsets exist, memory T cells are generally subdivided into effector memory T (TEM) and central memory T (TCM) cells. The former are commonly found in the circulation and peripheral tissues, express CD45RO (but not CCR7 and CD62L), and can readily recover effector functions. The latter are mostly found in lymphoid organs, express CD45RO, CCR7 and CD62L, and are relatively insensitive to reactivation. A subset of TEM cells expressing CD69 and CD103 that appears to be restricted to tissues (not found in the circulation) has been dubbed tissue resident memory (TRM) cells [152].

Whether memory T cells are direct descendant of activated naïve T cells or originate from effectors that elude apoptotic cell death during the contraction phase has been the matter of intense debate in the field. Recent research revealed that the epigenetic landscape of memory T cells and effector T cells exhibits a large degree of similarity, supporting the hypothesis that memory formation occurs in the context of the contraction phase [153,154].

Differentiation of CD4+ helper T (TH) cells is also regulated by canonical and non-canonical WNT signaling. Hence, non-canonical WNT signaling by WNT5A promotes TH1 responses by stimulating IL-12 secretion from dendritic cells (DCs) [39] and, accordingly, low numbers of interferon gamma (IFNG)-producing TH1 cells are detectable upon conditional WNT5A deficiency in a mouse model of colitis [40]. Conversely, TCF1 and β-catenin support TH2 polarization by activating the expression of the TH2 master TF GATA binding protein 3 (GATA3) via SATB homeobox 1 (SATB1), a chromatin organizer with pivotal roles in T cell development [41,42]. That said, a recent study shows that platelet-derived WNT inhibitor DKK1 favors TH2 polarization and exacerbates leukocyte trafficking in mouse models of allergic asthma and parasite infection, de facto aggravating disease progression [43], which suggests that canonical WNT-mediated regulation of TH polarization may be dependent on the physiological or pathological context. Furthermore, sustained activation of β-catenin in mouse CD4+ thymocytes results in RAR related orphan receptor C (RARC; best known as RORγt) upregulation and consequent TH17 polarization, culminating with the production of proinflammatory cytokines that favor tumorigenesis [44]. Conversely, the effector function and development of TH17 cells are antagonized by CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ regulatory T (TREG) cells, which, in turn, are also under intricate regulation by canonical WNT signaling. Thus, while enforced β-catenin expression in TREG cells favors cell survival (at least in vitro) [45], canonical WNT signaling limits the immunosuppressive activity of these cells upon TCF1-dependent repression of forkhead box P3 (FOXP3) transcriptional activity [46].

Canonical WNT signaling also regulates the activation and differentiation of immune cell lineages other than T lymphocytes. Thus, inhibition of GSK3 downstream of B cell receptor (BCR) signaling drives a β-catenin-dependent wave of gene expression that supports cellular activation [47]. Moreover, despite conditional deletion of Ctnnb1 in B cell precursors does not impair B cell development [48], a paucity of B cell precursors has been reported in the bone marrow of Lef1−/− and Fzd9−/− mice, suggesting that canonical WNT signaling affects adaptive immune cells through indirect mechanisms [49,50]. Similarly, TCF1 is essential for the development of innate lymphoid cells (ILCs), a population of immune cells encompassing natural killer (NK) cells with broad roles in human pathophysiology. In particular, the earliest lineage-specific precursor of ILCs (which has lost the ability to form B and T cells) expresses high TCF1 levels [51], and Tcf7−/− mice lack type 2 ILCs [52] and exhibit defective NK cell survival owing to uncontrolled granzyme B (GZMB) production, which is toxic for NK cells on engagement with their targets [53]. Likewise, pharmacological inhibition of GSK3 favors NK cell maturation following the upregulation of various lineage-relevant TFs, including T-box 21 (TBX21; best known as T-BET), zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 2 (ZEB2) and PR/SET domain 1 (PRDM1; also known as BLIMP-1) [54]. Finally, an interplay between NOTCH and canonical WNT signaling promotes DC differentiation via the stromal delta-like canonical Notch ligand 1 (DLL1)-dependent upregulation of several FZD receptors in DC precursors [55] (Box 3). Altogether, the findings discussed above illustrate the paramount relevance of WNT signaling to immune system homeostasis, suggesting that alterations of this pathway under pathological scenarios, including cancer, can profoundly subvert protective immune responses.

Box 3. Overview of Dendritic Cell Functions.

Dendritic cells (DCs) are myeloid cells with a key role in the regulation of both innate and adaptive immune responses. Although the DC lineage is highly heterogeneous, DCs are classically subdivided into three major groups: (i) conventional DCs (cDCs), encompassing two subsets of lymph node-resident cDCs that express either CD4 or CD8α, as well as two subpopulations of migratory cDCs (expressing either CD11b+ or CD103+) that are normally found in non-lymphoid tissues but can migrate to secondary lymphoid organs on activation; (ii) monocyte-derived DCs, which express CD11b and CX3CR1; and (iii) plasmacytoid DCs, which express high levels of Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7) and TLR9 and hence are major producers of type I IFN (but have controversial roles in cancer).

Among other functions, DCs constantly sample the microenvironment for antigenic material that they process and present in association with MHC molecules, de facto operating as professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs). CD8α+ and CD103+ cDCs, whose development is strictly dependent on basic leucine zipper ATF-like transcription factor 3 (BATF3), display superior APC functions as compared to other DC subsets, especially with respect to cross-presentation (i.e., the ability of DCs to present extracellular antigens on MHC class I, rather than class II, molecules, which is particularly important for anticancer immunity). In steady-state conditions, cDCs display a high phagocytic and macropinocytic activity, but express low levels of MHC class I molecules and co-stimulatory ligands, and hence are major mediators of peripheral tolerance. However, several microbial and endogenous molecules can favor DC maturation, resulting in decreased uptake of extracellular material coupled with (i) the upregulation of the antigen-processing presentation machinery (including MHC molecules); (ii) the expression of multiple co-stimulatory molecules, including CD80 and CD86; (iii) the upregulation of CCR7, which enables the CCL19- and CCL21-dependent migration of mature DCs to the nearest draining lymph node; and (iv) secretion of chemotactic factors for T cells, including CCL3, CCL, CXCL9, and CXCL10. On interaction with mature DCs presenting an antigen in the context of MHC molecules, naïve T cells generally receive all the signals required for clonal expansion, including TCR-delivered cues, co-stimulation via CD28 (driven by CD80 and CD86), and cytokines (notably autocrine IL-2) [155].

WNT Signaling in Cancer

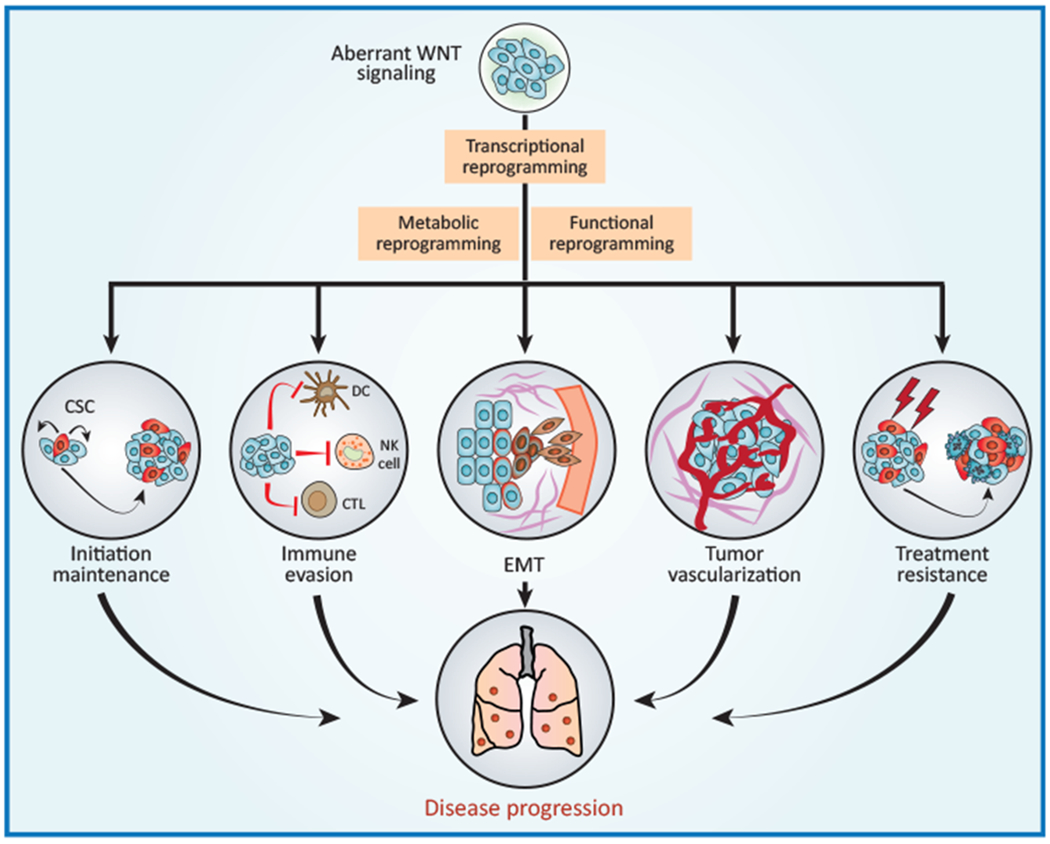

A large body of evidence implicates deregulated WNT signaling in virtually all stages of oncogenesis, from malignant transformation to metastatic dissemination and resistance to treatment (Figure 2). Indeed, Wnt1, the gene encoding the first WNT factor identified in mammals, was cloned as an oncogene in mouse mammary cancers [56]. Furthermore, the loss of one Apc allele was found to be sufficient to drive colorectal (and mammary) carcinogenesis in rodents [57], and re-expression of APC in APC-deficient mouse adenomas restores intestinal crypt homeostasis and potently drives tumor regression [58].

Figure 2. WNT Signaling and Cancer.

Deregulated WNT signaling in the tumor microenvironment supports malignant transformation and disease progression via a variety of mechanisms, including (but not limited to) (i) improved fitness of the cancer stem cell (CSC) compartment; (ii) evasion of tumor-targeting immune responses; (iii) activation of the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT); (iv) accrued neo-vascularization; and (v) increased resistance to a variety of treatment modalities. CTL, cytotoxic T lymphocyte; DC, dendritic cell; NK, natural killer.

Several genetic alterations that inhibit the proteasomal degradation of β-catenin, and thus result in constitutive canonical WNT signaling, are also common in human tumors (Table 1). Loss-of-function mutations in APC are frequent among colorectal carcinoma (CRC) patients [59]. A large sequencing project conducted on 1134 CRC samples identified several other alterations in core WNT regulators and quantified the incidence of oncogenic WNT activation to 96% of human CRCs [59]. Of note, recurrent fusions between protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type K (PTPRK), and RSPO3 have been reported in a subset of patients with CRC [60] and may constitute a potential therapeutic target [61].

Table 1.

Main Genetic and Epigenetic genetic or epigenetic alterations affecting components of the WNT signaling pathway in human cancers. Alterations Affecting Components of the WNT Signaling Pathway in Human Cancers

| Cancer type | Alteration | Frequency (%)a | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute myeloid leukemia | SFRP1 hypermethylation | 29 | [156] |

| SFRP2 hypermethylation | 19 | [156] | |

| Adrenocortical carcinoma | All alterations confounded | 41 | [64] |

| CTNNB1 stabilizing mutations | 14.4 | [64] | |

| MEN1 inactivating mutations | 7 | [64] | |

| WIF1 hypermethylation | 57.1 | [157] | |

| ZNRF3 deletion | 16 | [64] | |

| ZNRF3 inactivating mutations | 5.7 | [158] | |

| Bladder carcinoma | WIF1 hypermethylation | 66.7 | [159] |

| Breast carcinoma | APC hypermethylation | 45 | [160] |

| Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | SFRP1 hypermethylation | 69 | [161] |

| SFRP2 hypermethylation | 65 | [161] | |

| SFRP4 hypermethylation | 15 | [161] | |

| Colorectal carcinoma | All alterations confounded | 96 | [59] |

| APC hypermethylation | 18 | [162] | |

| APC inactivating mutations | 79 | [59] | |

| AXIN2 hypermethylation | 76 (MSI) | [163] | |

| AXIN2 inactivating mutations | 9 | [164] | |

| CTNNB1 stabilizing mutations | 8 | [59] | |

| DKK1 hypermethylation | 17 | [70] | |

| FAT1 inactivating mutations | 24 (MMR-D) | [165] | |

| FBXW7 inactivating mutations | 7.7 | [166] | |

| RNF43 inactivating mutations | 9 | [59] | |

| RSPO3 gene fusions | 8 (MSS) | [60] | |

| SFRP1 hypermethylation | 89 | [71] | |

| SFRP2 hypermethylation | 89 | [71] | |

| SFRP5 hypermethylation | 53.3 | [71] | |

| WIF1 hypermethylation | 82 | [167] | |

| Esophageal cancer | SFRP1 hypermethylation | 95 | [168] |

| SFRP2 hypermethylation | 96 | [169] | |

| SFRP4 hypermethylation | 83 | [169] | |

| SFRP5 hypermethylation | 73 | [169] | |

| WIF1 hypermethylation | 85 | [169] | |

| Gastric carcinoma | APC hypermethylation | 34 | [162] |

| SFRP1 hypermethylation | 91 | [170] | |

| SFRP2 hypermethylation | 96 | [170] | |

| SFRP5 hypermethylation | 65 | [170] | |

| WIF1 hypermethylation | 74.2 | [167] | |

| Glioblastoma multiforme | FAT1 deletion | 57.1 | [165] |

| FAT1 inactivating mutations | 20.5 | [165] | |

| Head and neck cancer | FAT1 inactivating mutations | 6.7 | [165] |

| FBXW7 inactivating mutations | 11.1 | [166] | |

| Hepatoblastoma | AXIN1 inactivating mutations | 7.4 | [171] |

| CTNNB1 stabilizing mutations | 70 | [171] | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | APC hypermethylation | 33 | [162] |

| AXIN1 inactivating mutations | 9.6 | [171] | |

| CTNNB1 stabilizing mutations | 19 | [171] | |

| FBXW7 inactivating mutations | 7.7 | [166] | |

| Medulloblastoma | CTNNB1 stabilizing mutations | 12 | [172] |

| Melanoma | APC hypermethylation | 17 | [173] |

| APC inactivating mutations | 4.8 | [174] | |

| AXIN1 inactivating mutations | 6.8 | [174] | |

| CTNNB1 stabilizing mutations | 5 | [175] | |

| FBXW7 inactivating mutations | 4.1 | [174] | |

| LGR5 inactivating mutations | 9.1 | [174] | |

| LRP6 inactivating mutations | 5.7 | [174] | |

| Multiple myeloma | DKK1 hypermethylation | 33 | [176] |

| SFRP1 hypermethylation | 35 | [177] | |

| SFRP2 hypermethylation | 52 | [177] | |

| Non-small-cell lung carcinoma | APC hypermethylation | 46 | [160] |

| WIF1 hypermethylation | 16–83 | [178] | |

| Oral squamous cell carcinoma | SFRP1 hypermethylation | 24 | [179] |

| SFRP2 hypermethylation | 36 | [179] | |

| SFRP5 hypermethylation | 16 | [179] | |

| Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | APC hypermethylation | 33 | [162] |

| MEN1 inactivating mutations | 2.1 | [174] | |

| RNF43 inactivating mutations | 7 | [65] | |

| WIF1 hypermethylation | 75 | [162] | |

| Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors | MEN1 inactivating mutations | 44 | [180] |

MMR-D, mismatch repair deficient; MSI, microsatellite instable; MSS, microsatellite stable.

Besides being a virtually universal feature of CRC, aberrant WNT signaling mediates oncogenic effects in many other oncological settings. For instance, deletion of GSK3B confers a pre-malignant state to (HSCs), which progresses to acute myeloid leukemia (AML) upon GSK3A loss [62]. Likewise, inactivating mutations of menin 1 (MEN1), encoding a β-catenin repressor, are a prominent feature of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors [63] and adrenocortical carcinoma, a setting in which CTNNB1 and ZNRF3 alterations are also common [64]. Despite occurring at relatively low frequency [65], inactivating RNF43 mutations render pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (PDACs) dependent on WNT signaling for proliferation (as evinced by restoring RNF43 expression, inhibiting the release of WNT ligands, or downregulating β-catenin) [66,67]. Such a requirement for niche-derived WNT ligands in PDACs is dynamically regulated during tumor progression by genetic programs orchestrated by GATA6 [68]. This circuitry defines a liability of some pancreatic tumors with therapeutic implications.

Aberrant WNT activation in tumors can also originate in the absence of genetic alterations, either as a consequence of epigenetic mechanisms or following the excessive secretion of WNT ligands by non-malignant components of the tumor microenvironment [69]. For instance, expression of several WNT antagonists such as SFRPs and DKK1 is impaired in a variety of cancers as a result of promoter hypermethylation [70,71] (Table 1), while WNT5A is overexpressed in glioblastoma following an epigenetic switch that culminates with the activation of paired box 6 (PAX6)- and distal-less homeobox 5 (DLX5)-dependent transcription [72]. Similarly, the tumor-draining lymph nodes of mice bearing syngeneic melanoma, thymoma, or lung carcinoma cells secrete increased amounts of WNT ligands [73]. These observations lend solid support to the notion that transformed cells benefit from deregulated WNT signaling.

Nonetheless, elevated levels of DKK1 have been documented in the tumor microenvironment and serum of patients with breast, liver, pancreas, stomach, cervix, and bile duct cancer [74]. Since DKK1 is a transcriptional target of β-catenin [75], it is tempting to speculate that DKK1 is overexpressed by progressing tumors as a consequence of deregulated WNT signaling but cannot establish normal feedback inhibition when WNT ligands are not responsible for β-catenin accumulation (e.g., in the presence of APC mutations). Thus, circulating DKK1 levels may be informative of WNT signaling in malignant lesions and potentially constitute a prognostic biomarker for WNT-driven tumors. Of note, binding of DKK1 to cytoskeleton associated protein 4 (CKAP4) stimulates cancer cell proliferation via phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling [76]. This observation exemplifies the ability of multiple components of the WNT signaling cascade to regulate biological functions other than β-catenin activation.

Solid tumors heavily rely on angiogenesis to grow locally and metastasize into distant organs, a process that also involves the loss of epithelial features concurrent with the acquisition of mesenchymal traits by malignant cells. Both angiogenesis and the so-called ‘epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition’ (EMT) are regulated by WNT signal transduction. In CRC, β-catenin governs a metabolic reprogramming towards glycolysis that drives angiogenesis [77]. Moreover, canonical WNT signaling supports the accumulation of the master EMT regulators snail family transcriptional repressor 1 (SNAI1; best known as SNAIL) and SNAI2 (best known as SLUG) as a consequence of GSK3B inhibition [78,79]. Importantly, macrophages and other myeloid cells can also provide WNT ligands that are involved in EMT and angiogenesis [80,81].

Non-canonical WNT5A signaling not only favors EMT upon the activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) and FYN proto-oncogene, Src family tyrosine kinase (FYN) [82] but also generates a microenvironment enriched of endothelial cells and stimulates the secretion of proteolytic enzymes that enable local invasion, such as matrix metallopeptidase 7 (MMP7), hence favoring metastasis by multiple mechanisms [72,83,84]. Of note, WNT signaling influences the organotropism of tumor cells progressing along the metastatic cascade [85]. For example, uncontrolled WNT signaling endows lung adenocarcinoma cells with a superior ability to infiltrate and colonize brain and bones [86]. Conversely, canonical WNT signaling driven by overexpression of the extracellular protein SPARC like 1 (SPARCL1) in osteosarcoma cells limits their ability to colonize the lungs owing to the recruitment of M1 macrophages with antitumor activity [87]. DKK1 produced by breast cancer cells also suppresses lung colonization (as a consequence of impaired recruitment of protumor neutrophils and macrophages to metastatic sites) but promotes bone colonization (by inhibiting WNT signaling in osteoclasts) [88]. Moreover, ILCs appear to generate a perivascular niche that sustains gastric carcinogenesis upon WNT5A secretion [89]. These observations exemplify how WNT signaling in different cell types can influence oncogenic progression in opposite directions, which has major therapeutic implications.

Besides supporting metastatic dissemination, EMT endows malignant cells with stem-like features [90], and so-called ‘cancer stem cells’ (CSCs) have been found to underlie proliferation, dissemination, and resistance to therapy in several tumors [91,92]. Tumor-initiating stem cells often rely upon WNT signaling [93,94], and WNT regulators, including LGR4 and LGR5, are highly expressed in tumor organoids established from a variety of malignancies including stomach, colon, liver, pancreas, and prostate cancer [95].

Along similar lines, FZD7 overexpression underlies the ability of a truncated form of tumor protein p63 (TP63) to establish a population of breast CSCs with tumor-initiating potential [96]. Moreover, LGR5+ lung adenocarcinoma cells displaying stem-like properties form distant lesions with the aid of WNT ligands provided by a small population of PORCN+ cancer cells that condition the metastatic niche [97]. Conversely, WNT inhibition by homeobox A5 (HOXA5) eliminates CSCs in mouse models of CRC, resulting in impaired metastatic dissemination [98]. That said, ablation of cells expressing LGR5, which share with intestinal stem cells the expression of this WNT regulator, restricts primary tumor growth, but does not stably eradicate disease in rodent models of CRC [93,99], indicating that LRG5− cells can also sustain tumor growth. These observations corroborate the notion that CSCs generally display high degrees of functional and phenotypic heterogeneity and plasticity [91,92].

Chemotherapy can cause considerable stress to tissues and, similar to wound-related injuries, can also lead to elevated WNT signaling [100,101]. WNT activation in chemotherapy-exposed tumors of the lung and liver can enhance their expression of fibroblast growth factor 4 (FGF4), hence initiating an insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1)-mediated crosstalk between cancer cells and their vasculature that promotes stemness and chemoresistance [100]. Similarly, mixed lineage leukemia (MLL)-dependent leukemic cells become resistant to GSK3 inhibition by a β-catenin-dependent mechanism [102]. Likewise, in AML, WNT signaling is responsible for MYC proto-oncogene, bHLH transcription factor (MYC) expression despite suppressed bromodomain containing 4 (BRDA4) signaling, de facto underlying chemoresistance to BET protein inhibitors [103,104]. In a mouse model of lymphoma, the establishment of senescence by chemotherapy is sometimes linked with the acquisition of stem-like features, including active WNT signaling, which interfere with senescence-dependent oncosuppression and re-enable proliferation [105]. Finally, WNT/β-catenin signaling confers radioresistance to a variety of tumors, mostly by DNA repair [106] or metabolic adaptation [107]. These observations exemplify well the links between deregulated WNT signaling, stemness, and chemoresistance.

In summary, even though WNTs may act conventionally in some cases to drive proliferation, recent evidence suggests that WNT signaling promotes cancer ‘stemness’, invasion, and therapeutic resistance through a diverse array of multifaceted and more circuitous routes (Figure 2).

WNT Signaling and Cancer Immunosurveillance

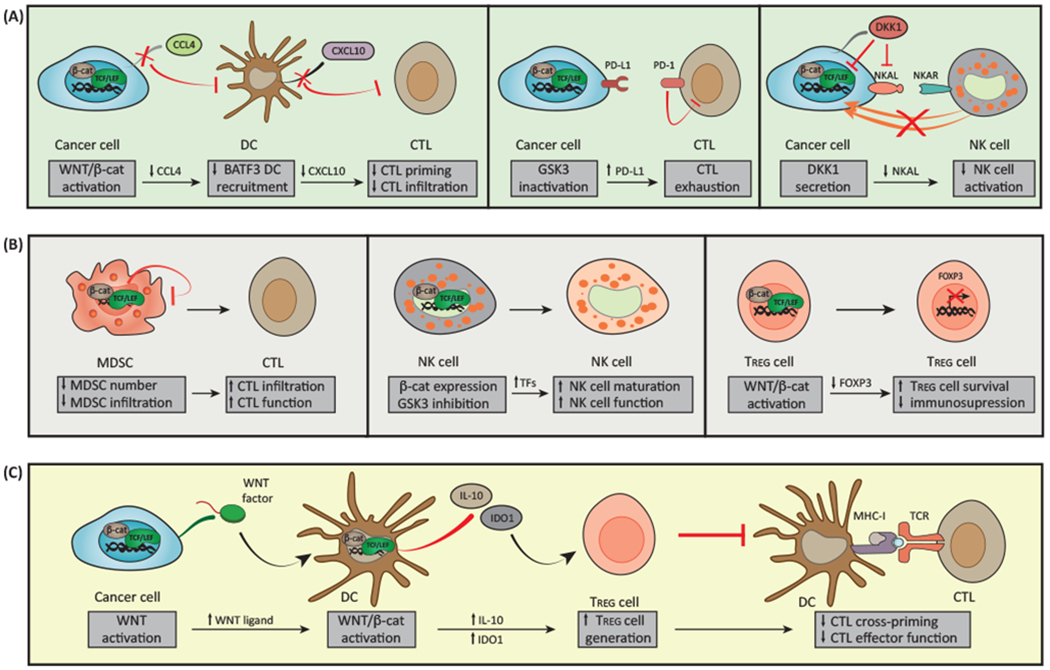

Depending upon context, WNT signaling has been found to either positively or negatively influence anticancer immunosurveillance by regulating multiple aspects of the tumor-immune cell interplay, including the immunogenicity of malignant cells as well as the ability of immune cells to elicit effective tumor-targeting immune responses (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Impact of WNT Signaling on Cancer Immunosurveillance.

(A) Activation of WNT/β-catenin pathway in malignant cells inhibits secretion of C-C motif chemokine ligand 4 (CCL4) that is required for the recruitment of basic leucine zipper ATF-like transcription factor 3 (BATF3)-dependent dendritic cells (DCs) to the tumor microenvironment. This results in reduced levels of DC-derived C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL10) and limited CD8+ cytotoxic T cell (CTL) infiltration and hence defective cross-priming. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) in cancer cells promotes β-catenin activation and consequent stabilization of programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) that drives CTL exhaustion upon interaction with PD-1. The secretion of dickkopf WNT signaling pathway inhibitor 1 (DKK1) by latent metastatic cells prevents natural killer (NK) cell-dependent cancer cell lysis by reducing the expression of NK cell activating ligands (NKALs) that engage NK cell activatory receptors (NKARs). (B) Canonical WNT/β-catenin in myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) inhibits their accumulation and ability to infiltrate malignant lesions, resulting in increased recruitment of CTLs. GSK3 inhibition and β-catenin overexpression in NK cells result in the upregulation of transcription factors responsible for NK cell maturation, hence stimulating NK cell effector function. While enforced expression of β-catenin favors regulatory T (TREG) cell survival in vitro, activation of transcription factor 1 (TCF1, encoded by TCF7) downstream of canonical WNT signaling impairs the immunosuppressive activity of TREG cells by blocking forkhead box P3 (FOXP3) transcriptional functions. (C) WNT ligands released by cancer cells can induce canonical WNT signaling in DCs, resulting in increased secretion of interleukin 10 (IL-10), limited production of IL-12, and upregulation of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1). This favors the generation of TREG cells and consequent inhibition of CTL activity.

Tumor-intrinsic WNT signaling impinges on the immunogenicity of cancer cells. Thus, some components of the WNT signal transduction cascade that are overexpressed by cancer cells can be recognized by the immune system as tumor-associated antigens (TAAs), as documented for mutant β-catenin that was specifically recognized by autologous cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) in a patient with melanoma [108]. Hence, core members of the WNT signaling pathway may constitute targets for the development of tumor-specific vaccines. Indeed, a DKK1-based vaccine was shown to elicit protective immune responses mediated by CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes in a murine model of myeloma, supporting that, given its tumor-restricted expression, vaccination with DKK1 may represent a feasible immunotherapeutic approach for patients with multiple myeloma [109].

In addition, WNT signaling has been shown to play a major role in regulating the immune tolerance against tumors. In this regard, a compelling body of work shows that tumor-induced β-catenin signaling operates in DCs to impose a tolerogenic phenotype on immune effector cells infiltrating the tumor bed, hampering DC-dependent cross-priming of antitumor CTLs. In fact, patients with melanoma refractory to immunotherapy with DC vaccines developed immune tolerance caused by administration of denileukin diftitox that increased β-catenin expression in the skin [110]. Along similar lines, expression of non-degradable β-catenin in melanoma cells or DCs results in the secretion of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 and hence impairs the ability of DCs to cross-prime tumor-targeting CD8+ CTLs [111,112]. LRP5 and LRP6 appear to be required for this process, as conditional co-deletion of these WNT co-receptors in DCs inhibits the secretion of immunosuppressive cytokines and reinstates normal cross-priming in melanoma mouse models [73]. Melanomas also limit antitumor immunity by canonical or non-canonical WNT signaling in DCs, which have been associated with metabolic immunosuppression via vitamin A [113] or indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) [114,115]. That said, even though most work demonstrates that canonical WNT signaling inhibits antitumor CTL cross-priming, activation of this pathway in DCs seems to be important for the maintenance of clonally expanded, antigen-specific CTLs. Thus, the CTLs of mice bearing a DC-specific deletion of Ctnnb1 expand normally upon vaccination with a TAA-derived peptide, yet they are unable to afford protection against TAA-expressing cancer cells [112]. These observations suggest that WNT signaling exerts stage-dependent disparate roles in regulating anticancer responses along the CTL activation process.

Excluding immune cell (mainly CTL) infiltration into the tumor microenvironment constitutes a prominent mechanism of WNT-mediated immunoevasion in different types of cancer, mainly melanomas. Thus, mouse melanomas driven by conditional expression of oncogenic Braf plus Pten deletion and engineered to express β-catenin are unable to express C-C motif chemokine ligand 4 (CCL4), resulting in defective recruitment of CD103+ DCs [116]. This prevents tumor infiltration by CTLs, owing to the absence of CD103+ DC-derived chemokines such as C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 9 (CXCL9) and CXCL10, de facto compromising antitumor immune responses [116,117]. Similarly, β-catenin signaling has been shown to inversely correlate with immune tumor infiltration and survival in patients with primary cutaneous [118] and metastatic melanoma treated with BRAF inhibitors [119].

The lack of effector cells into the tumor microenvironment, as typically observed in tumor with active canonical WNT signaling, is also a main cause of primary resistance to cancer immunotherapies with so-called ‘immune checkpoint blockers’ (ICBs) [120]. Indeed, tumor-intrinsic, active β-catenin signaling in human melanoma seems to cause resistance to anti-CD274 [best known as programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1)] and anti-cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA4) resistance to monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) targeting CD274 (best known as PD-L1) and cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA4) through T cell exclusion [116]. In addition, alterations in canonical WNT signaling impinge on ICB efficacy by regulating the expression of several immune checkpoints, although exactly how is not so clear and seems to depend upon both context and choice of determinant. Thus, for instance, in mouse models of mammary carcinomas, active signaling via the GSK3B-β-TrCP axis (as in the absence of WNT ligands) favors the ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of non-glycosylated PD-L1, ultimately increasing tumor infiltration by IFNG-producing CTLs [121]. By contrast, in mouse melanoma models, GSK3 blockers improve tumor eradication, apparently by repressing the gene encoding programmed cell death 1 (PDCD1; best known as PD-1), which functions in self-tolerance by downregulating T cell inflammatory activity [122,123]. Since GSK3 can affect pathways besides canonical WNT signaling, the action of inhibitors may not necessarily be rooted in stabilization of β-catenin per se.

Finally, there are cases in which WNT signaling exerts overt anticancer effects (Figure 3). For instance, differentiation of primed CD8+ T cell is halted by canonical WNT signaling, giving rise to a population of memory stem-like CD8+ T cells with heightened effector function against adoptively transferred B16 melanoma cells [38]. Likewise, β-catenin signaling limits the tumor-promoting role of CD11B+Gr-1+ myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) [124]. Thus, β-catenin inhibition downstream of the deletion of Plcg2 [125], Cul4b [126], or Muc1 [127], as well as a consequence of increased microenvironmental DKK1 availability [128], results in MDSC expansion and recruitment to the tumor microenvironment, thereby impairing immune responses against several types of tumors. Similarly, autocrine DKK1 causes quiescence in lung metastatic cancer cells, a state that results in the diminished expression of genes encoding certain cell surface markers recognized by NK cells, thereby allowing malignant cell evasion of anticancer innate responses [129]. In this way, by counterbalancing the action of stromal WNT signals, a population of quiescent CSCs may ultimately gain an advantage in immunoevasion.

Taken together, these observations indicate that WNT signaling influences cancer immunosurveillance in complex and context-dependent manners that cannot be represented by a simple mechanistic paradigm.

Therapeutic Opportunities for WNT Modulation in Cancer Immunotherapy

Several agents targeting core components or regulators of WNT signaling have been developed for cancer therapy during the past few years [130]. Although none of these molecules are currently approved by regulatory agencies for use in patients, several are currently being tested in clinical trials listed in the U.S. National Library of Medicine database (https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/).

Initially, attention was mainly devoted to the disruption of WNT-driven tumor growth, leading to the development of multiple agents including monoclonal antibodies against FZD receptors (e. g., OMP-18R5), PORCN inhibitors (e.g., LGK974, IWP-L6), AXIN1 activators (e.g., XAV939), and blockers of β-catenin-dependent transcription (e.g., PKF115-584). Although the immunomodulatory potential of these molecules has been long disregarded, accumulating evidence suggest that (at least part of) the therapeutic activity of WNT inhibitors stems from the re-establishment of anticancer immunity. For instance, PKF115-58 efficiently stimulates DCs to cross-prime melanoma-specific CTLs, resulting in robust therapeutic responses (at least in mice) [111]. Similarly, both IWP-L6 and XAV939 deplete TREG cells from the tumor microenvironment, hence enabling therapeutically relevant immune responses in mouse models of melanoma and lymphoma [73,113]. These are just two examples of the various mechanisms whereby WNT inhibitors can mediate immunomodulatory effects that are relevant for cancer therapy (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effects of WNT Modulation on Cancer Immunosurveillance

| Agent | Stage of development | Mechanism of actiona | Effect on WNT signaling | Effect on immunosurveillance | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artesunate | Approved | Unclear | Inhibition | - Not yet tested | [181] |

| Bafilomycin A | Preclinical | Lysosomal inhibitor | Controversial | - May favor expression of co-stimulatory ligands and receptors - Inhibits autophagy-driven immunosurveillance |

[141,142,182] |

| C59 | Preclinical | PORCN inhibitor | Inhibition | - Synergizes with CTLA4-targeting antibodies in mouse melanoma models | [115] |

| Celecoxib | Approved | COX2 inhibitor | Inhibition | - Boosts the efficacy of DC-based vaccines by downregulating IDO1 - Depletes intratumoral TREG cells |

[144,145] |

| CGX1321 | Clinical | PORCN inhibitor | Inhibition | - Not yet tested | [183] |

| CHIR99021 | Preclinical | GSK3 inhibitor | Activation | - Stimulates NK cell maturation and anticancer activity | [54] |

| Chloroquine | Approved | Lysosomal inhibitor | Controversial | - May favor expression of co-stimulatory ligands and receptors - Inhibits autophagy-driven immunosurveillance |

[143,182] |

| DKK1-targeting antibodies | Clinical | DKK1 blocker | Activation | - Depletes intratumoral MDSCs - Favors tumor infiltration by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells |

[128] , |

| DKK1-targeting vaccine | Preclinical | DKK1 blocker | Activation | - Elicits immune responses against DKK1-expressing myeloma cells | [109] |

| ETC1922159 | Clinical | PORCN inhibitor | Inhibition | - Not yet tested | [184] |

| Foxy-5 | Clinical | WNT5A mimic | Activation | - Not yet tested | [185] , |

| IWP-L6 | Preclinical | DVL2 inhibitor PORCN inhibitor |

Inhibition | - Favors tumor infiltration by IFNG-producing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells - Depletes intratumoral TREG cells |

[73,186] |

| Lenalidomide | Approved | CSNK1A inhibitor | Activation | - Boosts T cell functions and synergizes with ICBs in mouse myeloma models | [138,139,187,188] |

| LGK974 | Clinical | PORCN inhibitor | Inhibition | - Not yet tested | [189,190] , , |

| Niclosamide | Clinical | AXIN1 activator | Inhibition | - Not yet tested | [191] |

| OMP54F28 | Clinical | WNT decoy | Inhibition | - Not yet tested | [192] |

| OTSA101 | Clinical | FZD10-targeting ARC | Inhibition | - Not yet tested | [193] |

| PKF115-584 | Preclinical | β-Catenin inhibitor | Inhibition | - Restores CTL activation in vivo | [111,194] |

| PRI724 | Clinical | β-Catenin inhibitor | Inhibition | - Not yet tested | [195] , , |

| RXC004 | Clinical | PORCN inhibitor | Inhibition | - Not yet tested | |

| SB415286 | Preclinical | GSK3 inhibitor | Activation | - Enhances leukemia eradication by NK cells in vivo - Boosts clearance of transplanted tumors by downregulating PD-1 expression |

[123,196,197] |

| SM08502 | Clinical | Unclear | Inhibition | - Not yet tested | |

| TWS119 | Preclinical | GSK3 inhibitor | Activation | - Favors generation of CD8+ memory cells with increased effector functions - Reduces effector functions of CD19-targeted CAR T cells in vitro |

[38,198] |

| WNT5A trap | Preclinical | WNT5A inhibitor | Inhibition | - Modulates the immunological tumor contexture - Favors doxorubicin-driven immunogenic cell death |

[136] |

| XAV939 | Preclinical | AXIN1 activator | Inhibition | - Favors tumor infiltration by IFNG-producing CD8+ T cells - Depletes intratumoral TREG cells |

[113,199] |

ARC, antibody-radionuclide conjugate; COX2 (official name PTGS2), prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2; DVL2, dishevelled segment polarity protein 2; FZD10, frizzled class receptor 10.

The immunological contexture of the tumor microenvironment has a major impact on the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy, not only in terms of composition, but also in terms of activation status and localization [131]. Indeed, a high number of immunotherapeutic modalities (including several agents currently available in the clinics) aims at inhibiting local or systemic immunosuppression to revert CTL exhaustion and reinstate immunological tumor control [132]. Notably, ICBs limit the ability of co-inhibitory receptors such as PD-1 and CTLA4 to establish CTL exhaustion. The competence of ICB-based immunotherapy, however, is severely reduced when CTLs are absent (a configuration commonly known as ‘immune desert’) or cannot infiltrate malignant cell nests (a configuration commonly referred to as ‘exclusion’) [133]. As the excluded phenotype is particularly prevalent among cancers exhibiting WNT activation [116], inhibitors of canonical WNT signaling may synergize with CTLA4-blocking mAbs at suppressing the growth of mouse melanoma established in immunocompetent syngeneic mice [115]. In line with this notion, one arm of a Phase I clinical study is evaluating the safety and preliminary efficacy of LGK974 plus the anti-PD-1 antibody spartalizumab (previously known as PD001) in patients with solid malignancies linked to aberrant WNT signaling ().

The efficacy of several conventional therapeutic strategies against cancer, including multiple chemotherapeutics, radiation therapy, and some targeted anticancer agents, depends in large part on the activation of anticancer immune responses [134]. In particular, some anticancer agents such as doxorubicin and oxaliplatin can cause a pronouncedly immunogenic variant of cell death that is sufficient for the establishment of adaptive anticancer immunity [135]. WNT signaling has been suggested to limit the efficacy of multiple anticancer therapies that operate in this manner. Thus, trapping WNT5A within the tumor microenvironment with a fusion protein encompassing the extracellular domain of FZD7 markedly reverses immunosuppression in a mouse model of BRAF-driven melanoma, synergistically increasing the otherwise limited efficacy of doxycycline-based chemotherapy [136]. Taken together, these observations suggest that WNT inhibitors may boost the activity of chemotherapy and ICB-based immunotherapy.

That said, GSK3 inhibitors (which stabilize β-catenin and hence boost WNT signaling) have been shown not only to skew the differentiation of CD8+ T cells CD4+ TH17 cells towards a stem-like state with superior anticancer functions [38,137] but also to stimulate NK cell-dependent anticancer immunity, at least in part by driving the expression of NK cell-activating ligands by malignant cells [129]. Moreover, restoration of β-catenin expression in MDSCs as well as the administration of an anti-DKK1 mAb limits tumor growth by favoring the establishment of an immunocompetent tumor microenvironment [128]. Thus, there are settings in which WNT activation may constitute a therapeutic target, at least based on preclinical evidence. To the best of our knowledge, this strategy has not been actively pursued yet in the clinic.

Several pharmacological agents with broad biological effects, including some immunomodulatory molecules, can also impact WNT signaling. For instance, lenalidomide (an immunostimulatory thalidomide analog used to treat patients with various hematological malignancies) triggers the proteasomal degradation of CSNK1A [138], hence stimulating canonical WNT signaling in multiple myeloma cells [139]. Similarly, nonspecific lysosomal inhibitors including the antimalarial agent chloroquine [140] have been reported to alter WNT signaling [141–143], although the precise mechanisms remain obscure. The non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug celecoxib limits β-catenin-dependent transcription in CRC [144] as it stimulates the antitumor efficacy of DC-based cancer vaccines, at least in part by releasing CTLs from IDO1-dependent immunosuppression [145]. Finally, the antibiotic salinomycin appears to mediate cytotoxic activity against CSCs along with WNT signaling inhibition [146]. These observations suggest that WNT signaling (similar to other core signal transduction cascades) may be particularly sensitive to environmental perturbations including multiple forms of treatment.

Concluding Remarks

The studies discussed in this review article point to a role for WNT signaling in tumor initiation, progression to malignancy, and resistance to therapeutics. WNT signaling can impact not only the biology of (pre)malignant cells but also the ability of cancer cells to evade the immune system. Thus, WNT modulators currently stand out as promising candidates to improve the efficacy of various immunotherapeutic agents in the context of combinatorial treatment regimens, a possibility that is currently under scrutiny in multiple preclinical tumor models. However, several caveats should be kept in mind (see Outstanding Questions). First, many of the studies on WNT signaling and immunosurveillance discussed above relied on the artificial overexpression or mutational (in)activation of core components and/or regulators of the pathway, which may not properly recapitulate physiological settings [31]. Second, similar to the effectors and regulators of most (if not all) cellular functions including autophagy and cell death [140], several factors involved in WNT signaling (e.g., GSK3) are involved in a variety of signal transduction pathways, which calls for a cautious (re)interpretation of studies attributing cellular and organismal phenotypes to WNT signaling based on manipulations to single proteins. Fourth, WNT signaling is paramount for the maintenance of physiological homeostasis and wound repair in a variety of tissues, implying that systemic administration of WNT modulators may have considerable side effects, especially in the presence of additional drugs. Finally, as the effects of WNT signaling on cancer progression are context dependent, the use of non-targeted WNT modulators may not necessarily be beneficial for all types of tumors. Therefore, efforts will have to be devoted to the development of platforms for the targeted delivery of WNT modulators to the cells of choice. Furthermore, it will be essential to determine whether and how commonly used anticancer agents alter WNT signaling per se, especially for the development of combinatorial therapeutic regimens involving specific WNT modulators.

Outstanding Questions.

Which are the precise implications of WNT signaling on the modulation of anticancer immunity by GSK3 inhibitors?

What is the potential role of deregulated WNT signaling in immune responses targeting tumors other than melanomas?

Is it conceivable that, in specific scenarios, WNT signaling may promote, rather than inhibit, anticancer immunity?

What impact does WNT signaling have on specific cell subsets that are pivotal for anticancer immunity, such as NK cells?

Which WNT signaling-unrelated effects (if any) do components of the WNT signaling machinery mediate?

What is the actual clinical profile of novel combinatorial anticancer therapies involving immunotherapeutic agents such as immune checkpoint blockers and WNT signaling modulators?

A large body of preclinical data, mostly from melanoma mouse models, evidences that WNT/β-catenin signaling limits ICB efficacy by reducing the presence of CTLs into the tumor-immune contexture. Likewise, the expression levels of some components of the WNT signaling cascades have been linked to insensitivity to ICB-based immunotherapy in patients with melanoma [147] . Of relevance, a recent Phase Ib clinical trial revealed that intratumoral injection of an oncolytic virus, while not augmenting toxicity, significantly increased CTL tumor infiltration and improved anti-PD-1 (pembrolizumab) clinical responses in patients with metastatic melanoma [148]. Therefore, it is tempting to speculate, but remains to be formally addressed, that oncolytic virotherapy may constitute an alternative to a potentially toxic combination therapy involving a WNT modulator in order to revert β-catenin-driven primary resistance to ICB anticancer therapies.

In summary, although WNT modulators represent attractive candidates for the development of combinatorial immunotherapeutic regimens against cancer, additional preclinical and clinical work is required to understand the true potential of these molecules.

Highlights.

Canonical WNT signaling plays a central role in embryogenesis, tissue homeostasis, and wound repair.

Deregulated WNT signaling is involved in virtually all stages of oncogenesis.

Impaired anticancer immunity as a result of aberrant WNT signaling is emerging as a key contributor to tumor progression and resistance to treatment.

Activation of canonical WNT signaling hampers T cell-mediated anticancer immune responses by multiple mechanisms including immune exclusion.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Yuxuan Miao, Rene Adam, and Hanseul Yang (Rockefeller University) for comments on this review article. We apologize to the many authors with articles dealing with WNT signaling and cancer immunotherapy that we were not able to discuss and cite owing to space limitations. L.G. is supported by a startup grant from the Department of Radiation Oncology at Weill Cornell Medical College (New York, USA) and by donations from Sotio a.s. (Prague, Czech Republic), Phosplatin (New York, USA), and the Luke Heller TECPR2 Foundation (Boston, MA, USA). S.S. is supported through the National Cancer Institute R00CA204595 award. E.F.’s work in this arena has been supported by grants from NYS-TEM CO29559 and National Institutes of Health (R01-AR31737, R01-AR27883). E.F. is also a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator.

Footnotes

Disclaimer Statement

L.G. provides remunerated consulting to OmniSEQ (Buffalo, NY, USA). S.S. serves on the scientific advisory board for Venn Therapeutics.

References

- 1.Nusse R and Clevers H (2017) Wnt/beta-catenin signaling, disease, and emerging therapeutic modalities. Cell 169, 985–999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lien WH and Fuchs E (2014) Wnt some lose some: transcriptional governance of stem cells by Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Genes Dev. 28, 1517–1532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karasik D et al. (2016) The genetics of bone mass and susceptibility to bone diseases. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol 12, 323–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butler MT and Wallingford JB (2017) Planar cell polarity in development and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 18,375–388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murillo-Garzon V and Kypta R (2017) WNT signalling in prostate cancer. Nat. Rev. Urol 14, 683–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gagnaire A et al. (2017) Collateral damage: insights into bacterial mechanisms that predispose host cells to cancer. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 15, 109–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spranger S and Gajewski TF (2018) Impact of oncogenic pathways on evasion of antitumour immune responses. Nat. Rev. Cancer 18, 139–147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stamos JL and Weis WI (2013) The beta-catenin destruction complex. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 5, a007898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li VS et al. (2012) Wnt signaling through inhibition of beta-catenin degradation in an intact Axin1 complex. Cell 149, 1245–1256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daniels DL and Weis WI (2005) Beta-catenin directly displaces Groucho/TLE repressors from Tcf/Lef in Wnt-mediated transcription activation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 12, 364–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merrill BJ et al. (2004) Tcf3: a transcriptional regulator of axis induction in the early embryo. Development 131, 263–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu S et al. (2012) The TCF-1 and LEF-1 transcription factors have cooperative and opposing roles in T cell development and malignancy. Immunity 37, 813–826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shy BR et al. (2013) Regulation of Tcf7l1 DNA binding and protein stability as principal mechanisms of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Cell Rep. 4, 1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adam RC et al. (2018) Temporal layering of signaling effectors drives chromatin remodeling during hair follicle stem cell lineage progression. Cell Stem Cell 22, 398–413 e7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kakugawa S et al. (2015) Notum deacylates Wnt proteins to suppress signalling activity. Nature 519, 187–192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mao B et al. (2002) Kremen proteins are Dickkopf receptors that regulate Wnt/beta-catenin signalling. Nature 417, 664–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cruciat CM and Niehrs C (2013) Secreted and transmembrane wnt inhibitors and activators. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 5, a015081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koo BK et al. (2012)Tumour suppressor RNF43 is a stem-cell E3 ligase that induces endocytosis of Wnt receptors. Nature 488, 665–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hao HX et al. (2012) ZNRF3 promotes Wnt receptor turnover in an R-spondin-sensitive manner. Nature 485, 195–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Azzolin L et al. (2014) YAP/TAZ incorporation in the beta-catenin destruction complex orchestrates the Wnt response. Cell 158, 157–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park HW et al. (2015)Alternative Wnt signaling activates YAP/TAZ. Cell 162, 780–794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ouspenskaia T et al. (2016) WNT-SHH antagonism specifies and expands stem cells prior to niche formation. Cell 164, 156–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang Y and Mlodzik M (2015) Wnt-Frizzled/planar cell polarity signaling: cellular orientation by facing the wind (Wnt). Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol 31, 623–646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Niehrs C(2012)The complex world of WNT receptor signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 13, 767–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kabiri Z et al. (2015) Wnts are dispensable for differentiation and self-renewal of adult murine hematopoietic stem cells. Blood 126, 1086–1094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cobas M et al. (2004) beta-Catenin is dispensable for hematopoiesis and lymphopoiesis. J. Exp. Med 199, 221–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeannet G et al. (2008) Long-term, multilineage hematopoiesis occurs in the combined absence of beta-catenin and gamma-catenin. Blood 111, 142–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sugimura R et al. (2012) Noncanonical Wnt signaling maintains hematopoietic stem cells in the niche. Cell 150, 351–365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nemeth MJ et al. (2007) Wnt5a inhibits canonical Wnt signaling in hematopoietic stem cells and enhances repopulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 104, 15436–15441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luis TC et al. (2011) Canonical wnt signaling regulates hematopoiesis in a dosage-dependent fashion. Cell Stem Cell 9, 345–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Staal FJ et al. (2008) WNT signalling in the immune system: WNT is spreading its wings. Nat. Rev. Immunol 8, 581–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu Y et al. (2003) Deletion of beta-catenin impairs T cell development. Nat. Immunol 4, 1177–1182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson JL et al. (2018) Lineage-determining transcription factor TCF-1 initiates the epigenetic identity of T cells. Immunity 48, 243–257.e10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xing S et al. (2016)Tcf1 and Lef1 transcription factors establish CD8(+)T cell identity through intrinsic HDAC activity. Nat. Immunol 17, 695–703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao DM et al. (2010) Constitutive activation of Wnt signaling favors generation of memory CD8T cells. J. Immunol 184, 1191–1199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jeannet G et al. (2010) Essential role of the Wnt pathway effector Tcf-1 for the establishment of functional CD8T cell memory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 107, 9777–9782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou X et al. (2010) Differentiation and persistence of memory CD8(+)T cells depend on T cell factor 1. Immunity 33, 229–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gattinoni L et al. (2009) Wnt signaling arrests effector T cell differentiation and generates CD8+ memory stem cells. Nat. Med 15, 808–813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Valencia J et al. (2014) Wnt5a signaling increases IL-12 secretion by human dendritic cells and enhances IFN-gamma production by CD4+ T cells. Immunol. Lett 162 (1 Pt A), 188–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sato A et al. (2015) The Wnt5a-Ror2 axis promotes the signaling circuit between interleukin-12 and interferon-gamma in colitis. Sci. Rep 5, 10536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu Q et al. (2009) T cell factor 1 initiates the T helper type 2 fate by inducing the transcription factor GATA-3 and repressing interferon-gamma. Nat. Immunol 10, 992–999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Notani D et al. (2010) Global regulator SATB1 recruits beta-catenin and regulates T(H)2 differentiation in Wnt-dependent manner. PLoS Biol. 8, e1000296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chae WJ et al. (2016) The Wnt antagonist dickkopf-1 promotes pathological type 2 cell-mediated inflammation. Immunity 44, 246–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keerthivasan S et al. (2014) beta-Catenin promotes colitis and colon cancer through imprinting of proinflammatory properties in T cells. Sci. Transl. Med 6, 225ra28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ding Y et al. (2008) Beta-catenin stabilization extends regulatory T cell survival and induces anergy in nonregulatory T cells. Nat Med. 14, 162–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Loosdregt J et al. (2013) Canonical Wnt signaling negatively modulates regulatory T cell function. Immunity 39, 298–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Christian SL et al. (2002) The B cell antigen receptor regulates the transcriptional activator beta-catenin via protein kinase C-mediated inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3. J. Immunol 169, 758–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu Q et al. (2008) Role of beta-catenin in B cell development and function. J. Immunol 181, 3777–3783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reya T et al. (2000) Wnt signaling regulates B lymphocyte proliferation through a LEF-1 dependent mechanism. Immunity 13, 15–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ranheim EA et al. (2005) Frizzled 9 knock-out mice have abnormal B-cell development. Blood 105, 2487–2494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang Q et al. (2015) TCF-1 upregulation identifies early innate lymphoid progenitors in the bone marrow. Nat. Immunol 16, 1044–1050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang Q et al. (2013) T cell factor 1 is required for group 2 innate lymphoid cell generation. Immunity 38, 694–704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jeevan-Raj B et al. (2017) The transcription factor Tcf1 contributes to normal NK cell development and function by limiting the expression of granzymes. Cell Rep. 20, 613–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cichocki F et al. (2017) GSK3 Inhibition drives maturation of NK cells and enhances their antitumor activity. Cancer Res. 77, 5664–5675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou J et al. (2009) Notch and wingless signaling cooperate in regulation of dendritic cell differentiation. Immunity 30, 845–859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rijsewijk F et al. (1987) Transfection of the int-1 mammary oncogene in cuboidal RAC mammary cell line results in morphological transformation and tumorigenicity. EMBO J. 6, 127–131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Luongo C et al. (1994) Loss of Apc+ in intestinal adenomas from Min mice. Cancer Res. 54, 5947–5952 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dow LE et al. (2015) Apc restoration promotes cellular differentiation and reestablishes crypt homeostasis in colorectal cancer. Cell 161, 1539–1552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yaeger R et al. (2018) Clinical sequencing defines the genomic landscape of metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell 33, 125–136.e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Seshagiri S et al. (2012) Recurrent R-spondin fusions in colon cancer. Nature 488, 660–664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Storm EE et al. (2016) Targeting PTPRK-RSPO3 colon tumours promotes differentiation and loss of stem-cell function. Nature 529, 97–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Guezguez B et al. (2016) GSK3 deficiencies in hematopoietic stem cells initiate pre-neoplastic state that is predictive of clinical outcomes of human acute leukemia. Cancer Cell 29, 61–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jiang X et al. (2014) Targeting beta-catenin signaling for therapeutic intervention in MEN1-deficient pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Nat. Commun 5, 5809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zheng S et al. (2016) Comprehensive Pan-genomic characterization of adrenocortical carcinoma. Cancer Cell 29, 723–736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network (2017) Integrated genomic characterization of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell 32, 185–203 e13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jiang X et al. (2013) Inactivating mutations of RNF43 confer Wnt dependency in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 110, 12649–12654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Steinhart Z et al. (2017) Genome-wide CRISPR screens reveal a Wnt-FZD5 signaling circuit as a druggable vulnerability of RNF43-mutant pancreatic tumors. Nat. Med 23, 60–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Seino T et al. (2018) Human pancreatic tumor organoids reveal loss of stem cell niche factor dependence during disease progression. Cell Stem Cell 22, 454–467.e6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Anastas JN and Moon RT (2013) WNT signalling pathways as therapeutic targets in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 13, 11–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Aguilera O et al. (2006) Epigenetic inactivation of the Wnt antagonist DICKKOPF-1 (DKK-1) gene in human colorectal cancer. Oncogene 25, 4116–4121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Suzuki H et al. (2004) Epigenetic inactivation of SFRP genes allows constitutive WNT signaling in colorectal cancer. Nat. Genet 36, 417–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hu B et al. (2016) Epigenetic activation of WNT5A drives glioblastoma stem cell differentiation and invasive growth. Cell 167, 1281–1295.e18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hong Y et al. (2016) Deletion of LRP5 and LRP6 in dendritic cells enhances antitumor immunity. Oncoimmunology 5, e1115941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sato N et al. (2010) Wnt inhibitor Dickkopf-1 as a target for passive cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 70, 5326–5336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Niida A et al. (2004) DKK1, a negative regulator of Wnt signaling, is a target of the beta-catenin/TCF pathway. Oncogene 23, 8520–8526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kimura H et al. (2016) CKAP4 is a Dickkopf1 receptor and is involved in tumor progression. J. Clin. Invest 126, 2689–2705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pate KT et al. (2014) Wnt signaling directs a metabolic program of glycolysis and angiogenesis in colon cancer. EMBO J. 33, 1454–1473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wu ZQ et al. (2012) Canonical Wnt signaling regulates Slug activity and links epithelial-mesenchymal transition with epigenetic breast cancer 1, early onset (BRCA1) repression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 109, 16654–16659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhou BP et al. (2004) Dual regulation of Snail by GSK-3beta-mediated phosphorylation in control of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat. Cell Biol 6, 931–940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Linde N et al. (2018) Macrophages orchestrate breast cancer early dissemination and metastasis. Nat. Commun 9, 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yeo EJ et al. (2014) Myeloid WNT7b mediates the angiogenic switch and metastasis in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 74, 2962–2973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gujral TS et al. (2014) A noncanonical Frizzled2 pathway regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis. Cell 159, 844–856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]