Abstract

High-throughput screens in cancer cell lines (CCLs) have been used for decades to help researchers identify compounds with the potential to improve the treatment of cancer and, more recently, to identify genomic susceptibilities in cancer via genome-wide shRNA and CRISPR/Cas9 screens. Additionally, rich genomic and transcriptomic data of these CCLs has allowed researchers to pair this screening data with biological features, enabling efforts to identify biomarkers of treatment response and gene dependencies. In this paper, we review the major CCL screening efforts and the large datasets these screens have made available. We also assess the CCL screens collectively and include a resource with harmonized CCL and compound identifiers to facilitate comparisons across screens. The CCLs in these screens were found to represent a wide range of cancer types, with a strong correlation between the representation of a cancer type and its associated mortality. Patient ages and gender distributions of CCLs were generally as expected, with some notable exceptions of female underrepresentation in certain disease types. Also, ethnicity information, while largely incomplete, suggests that African American and Hispanic patients may be severely underrepresented in these screens. Nearly all genes were targeted in the genetic perturbations screens, but the compounds used for the drug screens target less than half of known cancer drivers, likely reflecting known limitations in our drug design capabilities. Finally, we discuss recent developments in the field and the promise they hold for enabling future screens to overcome previous limitations and lead to new breakthroughs in cancer treatment.

Keywords: Cancer, Cell Lines, Pharmacogenomics, Genetic Perturbation Screens, Biomarkers, Drug Screens

1. Introduction

Cancer cell lines (CCLs) have been used in pre-clinical research for decades to evaluate drug efficacy prior to advancing to more costly and difficult in vivo studies. This is in part because CCLs represent an easy-to-manipulate system for high-throughput drug and genomic screens on a scale simply unattainable in animal and patient settings due to safety, ethical, and logistical concerns. Additionally, automated liquid handling systems have made it possible to quickly screen thousands of compounds against many hundreds of CCLs while technological advances in genome sequencing have allowed detailed genomic characterization of each cell line screened. Improvements in RNA interference and genome editing technologies have also enabled genome-wide shRNA and CRISPR-Cas9 CCL screens to interrogate the necessity of nearly every gene in the genome in hundreds of CCLs. This wealth of drug sensitivity and genomic data has led to the clinical approval of bortezomib for myeloma treatment (Shoemaker, 2006), the initiation of several ongoing clinical trials (Holbeck et al., 2017), and numerous attempts to discover biomarkers associated with cancer drug response.

Despite these accomplishments, there is still much work to be done in developing new drugs and drug biomarkers to treat what remains an expansive list of poor prognosis cancers. Given the role of CCL screens in this effort, we seek here to examine how well these screens currently represent both the diversity of human cancers encountered in the clinic and the diversity of targetable pathways that are known to be deregulated in cancer. Recent advances in CCL screening and their potential impacts on future screens are also highlighted throughout this review. For those needing an introduction to the field, we provide a concise review of the major CCL screens that are publicly available, and, in an effort to facilitate the use of these screens, we harmonize cell line and drug identifiers between these screens and discuss screening overlap—an effort which was also recently completed by Smirnov et al. (Smirnov et al., 2017) for a subset of the CCL screens reviewed in this article. The hope of this review is ultimately to familiarize researchers with the current strengths and shortcomings of available CCL screening data, to provide a resource for interrogating current screening data, and to stimulate discussion regarding the future of CCL screening.

2. The History of Cancer Cell Line Screening

Numerous CCL screens have been performed over the last three decades, and the format and size of these screens has varied considerably. A very brief description to the history of these screens is provided in this section to demonstrate the progression of CCL screens. Given the large number of CCL screens available to date, we have chosen to focus most of our attention on large-scale screens with cell lines representing multiple cancer types. That said, several screens comprised of only a single cancer type are briefly mentioned by virtue of their being either relatively large or important in developing screening techniques. Further, only screens with publicly available screening data were included in this review. A brief tabular summary of reviewed screens is included in Table 1, with a more expansive tabular summary being provided in Table S1. We also provided individual summaries of each screen in sections 4–6.

Table 1. Available in vitro Cancer Screen Datasets.

This table provides summary information for the CCL screens we review in this article. Further details for each study, such as assay details and the locations of available data, can be found in table s1 and in the study descriptions provided in article sections 4–6. Cell line and compound numbers reflect the latest releases of each dataset, with duplicated cell lines in each study being counted as a single cell line, and only cell lines with available screening data included.

| Study Name | Type of Screen | Institution | # Cell Lines | # of Tested Reagents | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pan-Cancer CCL Screens | |||||

| NCI60 | compound | NCI | 74 | 49,278 compounds | https://wiki.nci.nih.gov/display/NCIDTPdata/ |

| GlaxoSmithKline | compound | GlaxoSmithKline | 310 | 19 compounds | Greshock et al., 2010 |

| CGP/GDSC | compound | Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute and Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center | 1073 | 249 compounds | Garnett et al., 2012; Iorio et al., 2016 |

| CCLE | compound | Broad Institute | 503 | 24 compounds | Barretina et al., 2012 |

| CTRP v1 | compound | Broad Institute | 242 | 354 compounds | Basu et al., 2013 |

| CTRP v2 | compound | Broad Institute | 887 | 496 compounds | Seashore-Ludlow et al., 2015 |

| gCSI | compound | Genentech | 429 | 16 compounds | Haverty et al., 2016 |

| FIMM | compound | Institute for Molecular Medicine Finland | 50 | 52 compounds | Mpindi et al., 2016 |

| NCI-ALMANAC | drug combination | NCI | 60 | 104 compounds (5,334 combinations) | Holbeck et al., 2017 |

| Single-Cancer CCL Screens | |||||

| Daemen et al. (Breast Cancer) | compound | Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory | 70 | 88 compounds | Daemen et al., 2013 |

| Colorectal Cancer Organoid Screen | compound | Hubrecht Institute, Wellcome Trust Sanger Insitute, Broad Institute | 19 (organoids) | 83 compounds | van de Wetering et al., 2015 |

| NCI-Sarcoma Project | compound | NCI | 64 | 440 compounds | Teicher et al., 2015 |

| NCI-SCLC Project | compound | NCI | 70 | 515 compounds | Polley et al., 2016 |

| PRISM (NSCLC) | compound | Broad Institute | 96 | 374 – 8,400 compounds | Yu et al., 2016 |

| shRNA & CRISPR/Cas9 CCL Screens | |||||

| Achilles 2.0 | shRNA | Broad Institute | 102 | 54,020 shRNAs (targeting 11,194 genes) | Cheung et al., 2011 |

| Achilles 2.4.3 | shRNA | Broad Institute | 216 | 54,020 shRNAs (targeting 11,194 genes) | Cowley et al., 2014 |

| Achilles 2.20.2 | shRNA | Broad Institute | 501 | 107,523 shRNAs (targeting 25,579 genes) | Tsherniak et al., 2017 |

| Achilles 3.3.8 | CRISPR/Cas9 | Broad Institute | 33 | 123,411 sgRNAs (targeting 19,060 genes) | Aguirre et al., 2016 |

| Munoz et al., 2016 | CRISPR/Cas9 & shRNA | Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research | 5 | 51,413 sgRNAs (targeting 2707 genes) | Munoz et al., 2016 |

| Tzelepis et al. (AML) | CRISPR/Cas9 | Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute | 7 | 90,709 sgRNAs (targeting 18,010 genes) | Tzelepis et al., 2016 |

| Wang et al. (AML) | CRISRP/Cas9 | Broad Institute | 14 | 187,536 sgRNAS (targeting 18,543 genes) | Wang et al., 2017 |

CCL Drug Screens

To date, the majority of large-scale CCL drug screens have been performed either by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) or the Broad Institute, with other notable screens having also been performed by GlaxoSmithKline, the Sanger Institute, the MGH cancer center, Genentech, the Institute for Molecular Medicine Finland, Novartis, and Berkeley National Laboratory (see Table 1 for references). The NCI began one of the first major CCL drug screening efforts in the 1980’s when it created the NCI60—an initiative to screen large numbers of known and novel compounds against a small group of CCLs. In its long history, the NCI60 has screened over 100,000 compounds and has been responsible for leading to a number of important cancer-related drug discoveries (Shoemaker, 2006). Among its breakthroughs, the NCI60 was used in the first study which integrated analysis of both molecular pharmacology and gene expression data for a large set of CCLs (Scherf et al., 2000). Since then, the genomes and transcriptomes of the CCLs used in drug screens have been extensively characterized, paving the way for studies which integrate genomic and drug sensitivity data.

Rather than focusing on screening huge compound libraries like the NCI-60, more recent large-scale CCL screens have focused on smaller compound sets screened in much larger numbers of CCLs. This approach has increased the genetic diversity of the screens, which has allowed researchers to draw links between genetic features and drug sensitivity. The methods and results of the NCI60 and the other major pan-cancer CCL screens are summarized in section 4. Tissue-specific cell line screens are also becoming more common. These screens usually contain more cell lines for a given cancer type compared to the pan-cancer screens and can be useful for interrogating the diversity within a particular cancer type. Section 5 contains summaries of these screens. Finally, recent advances in technology and screening techniques have allowed high-throughput screening of 2-drug combinations in Project NCI-ALMANAC (Holbeck et al., 2017) as well as the ability to pool CCLs together into single wells/tumors for both in vitro and in vivo drug screening using the PRISM method (Yu et al., 2016). These screens are also summarized in sections 4 and 5 respectively, and, along with other recent developments in CCL screening, their implications to future CCL screens are discussed in section 8.

CCL shRNA/CRISPR-Cas9 Screens

The advent of high-throughput methods for introducing shRNAs and gene edits via CRISPR-Cas9 into CCLs has allowed scientists to assess individual gene function by knocking down/out genes in panels of CCLs. By far the largest project using these methods is Project Achilles at the Broad Institute (see Table 1). Project Achilles has gradually increased the number of CCLs screened with shRNAs since first publishing in 2011 to now include 501 CCLs screened with shRNAs covering >25,000 gene products. Project Achilles also includes a CRISPR/Cas9 screen, which identified certain liabilities with CRISPR/Cas9 screening that could lead to a high rate of false-positive gene dependencies (Aguirre et al., 2016). This problem has been further researched by multiple groups, leading to the development of potential solutions (which are discussed in section 8) and enabling the use of CRISPR/Cas9 screens to discover novel gene dependencies and drug sensitivities in CCLs (Munoz et al., 2016; Tzelepis et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2017). A summary of these screens and their initial findings can be found in section 6.

3. An Overview of Cancer Cell Line Screens: How well are we doing?

Cell Lines

Human cancers are a complex set of diseases which can arise from essentially every tissue in the body and vary widely in both incidence and mortality. As such, CCL screens are faced with the task of balancing a need to select diverse sets of CCLs which represent a wide range of human cancers with the need to collect a large enough set of CCLs for any individual cancer type to capture the genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity within that cancer. To assess how well current CCL screens have accomplished this task, we identified screened CCLs by name using Cellosaurus (https://web.expasy.org/cellosaurus/) and then matched age, gender, and ethnicity information from a combination of Cellosaurus, the BioSample database (Barrett et al., 2012), and COSMIC (Forbes et al., 2017). An examination of the cell lines used in the studies covered by this review (see Table S2) shows that there are over 1,600 unique cell lines screened among the 20 datasets, covering more than 30 tissues of origin and over 200 cancer types/subsets. These include both common cancers (e.g. breast cancers) and extremely rare cancers (e.g. leiomyosarcomas) as well as highly specific cancer subsets (e.g. B-cell prolymphocytic leukemia). Interestingly, the proportions of CCLs representing any given cancer type correlate well with the American Cancer Society’s (Siegel et al., 2017) estimated number of deaths from those cancers (Figure 1a, R2=0.71). This suggests that current screens have been relatively successful in capturing the diversity of human cancers while prioritizing the cancers that cause the most deaths.

Figure 1. Screened CCLs Correlate with Cancer Fatality while Capturing Age, Gender, and Ethnicity to Varying Extents.

Data for this figure is included in Table S2. A) Correlation is shown between cancer mortality (obtained from Siegel et al., 2017) and the number of unique cell lines screened from each cancer type. Cancer type was determined by bioinformatic and manual curation using Cellosaurus, the BioSample database, COSMIC, or annotations provided by the datasets themselves. Only cell lines with available screening results are included. B-D) As with part A, age of collection, gender, and ethnicity for screened CCLs were determined by bioinformatic and manual curation using Cellosaurus, the BioSample database, and COSMIC. Part B shows the number of unique cell lines collected from patients at given ages, while parts C and D show the distribution of genders and ethnicities respectively for screened cell lines from each cancer type.

Beyond representing a diversity of human cancers, currently screened CCLs also represent a wide range of ages of onset in human cancer as well as relatively even proportions of male and female cancers (Figures 1b,1c), enabling these datasets to be used to study age- and gender-specific phenomenon in cancer drug sensitivity. Certain cancer types, however, do deviate significantly from clinical gender proportions. In lung cancer, for example, there are more than twice as many screened male CCLs as there are female CCLs (207 male, 84 female, Figure 1c). This disparity can be especially pronounced in cancer types with fewer screened CCLs such as liver cancer, for which there are 24 male CCLs and only 4 CCLs that we identified as female. If potential gender differences are to be studied in in vitro drug sensitivity for these cancers, care will need to be taken in designing future CCL screens to adequately represent both males and females in each cancer type.

Unlike age and gender, ethnicity is generally poorly annotated for CCLs. Based on the sources mentioned above, the ethnicity of many screened CCLs is unknown; however, most screened CCLs of known ethnicity are of either Caucasian or Asian descent (Figure 1d), with 87% of the Asian CCLs being Japanese. CCLs of African and Hispanic descent are particularly poorly represented. We were unable to identify any African CCLs in 7 of the 15 cancer categories, and Hispanic CCLs were absent in all but 1 of the categories.

As it is becoming increasingly apparent that ethnicity affects cancer progression and treatment response (Sekine et al., 2008; Keenan et al., 2015; Costa and Gradishar, 2017), this raises two primary concerns about discoveries made using currently available CCL screens. First, the probable lack of ethnic diversity suggests that some of these discoveries may not translate to patients from underrepresented ethnic groups. Second, the high level of uncertainty in CCL ethnicity prevents researchers from properly controlling for ethnicity while searching for pharmacogenomic associations—greatly reducing the ability of these datasets to detect ethnic-specific associations. However, the full extent to which ethnicity confounds somatic pharmacogenomic associations remains unclear, and these datasets are certainly still useful for discovering associations which are either ethnicity independent or which have large enough effect sizes in the well-represented ethnicities to be detected despite confounding ethnic effects. Given its importance to the utility of these datasets, ethnicity will need to be carefully considered and recorded when designing the next generation of CCL screens, and efforts to improve ethnicity information for existing CCLs should be considered (i.e. by contacting labs/institutions who generated CCLs of unknown ethnicity or searching for literature describing the generation of these CCLs).

CCL Screen Targets

Impacting a diverse set of molecular targets with drugs/compounds or shRNA/CRISPR is an equally important aspect of CCL screens. Unsurprisingly, the shRNA and CRISPR screens easily cover the most molecular targets, with most screens targeting over 11,000 and even up to 25,000 gene products. Thus, here we focus on assessing the diversity of the gene targets of the compounds included in the 14 compound-based screens highlighted in sections 4 and 5 (see Table S3). We identified the molecular targets of screened compounds using the Broad Drug Repurposing Hub (Corsello et al., 2017) and any target data provided by the screening datasets themselves. We were able to match gene targets for 1,207 drugs. This covers at least 64% of the drugs in each drug screen aside from the NCI-60, which screened a much higher proportion of probes and extracts with no targeted information (Table S3). It should also be noted that, of these compounds, the Broad Drug Repurposing Hub indicated that 857 of them are currently in or have completed testing in clinical trials (Figure 2a).

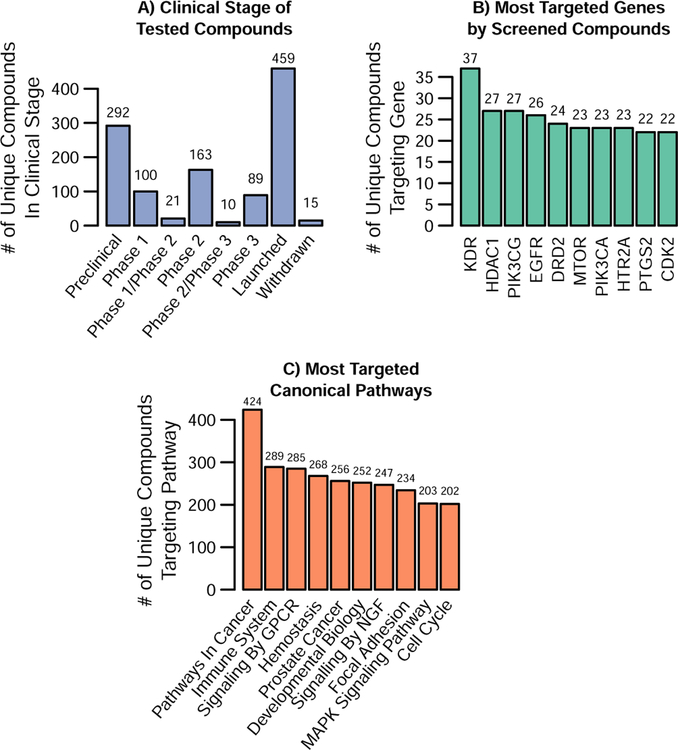

Figure 2. Targets and Clinical Stage of Compounds in CCL Screens.

Data for this figure is included in Tables S2, S4 and S5. Compounds used in Figure 2 are the 1,207 unique compounds from the 14 CCL drug screens reviewed in this paper with targeted information from the CCL screens or the Broad DRH. A) The clinical stage distribution for the drugs with current clinical trial information from Broad DRH (1149 of the 1207). B) Shows the ten most commonly targeted genes and the number of unique compounds against them. Table S4 contains the complete list of all the genes and their targeted frequency. C) Shows the 10 most commonly targeted pathways in MSigDB’s Canonical Pathway Gene Set (C2:CP) based on the number of unique compounds whose gene information in Table S4 indicate the compound impacts at least one gene target in that pathway. The full list of pathways and the number of genes and compounds that impact the pathway can also be found in Table S4.

Specifically, 1,234 genes were impacted by these drugs, with many genes targeted by multiple compounds. Figure 2b shows the ten most frequently targeted genes, which were each targeted by at least 22 unique compounds in the CCL screens we reviewed. Encouragingly, many of these top gene targets are recognizable as important in cancer. However, when overlaying these 1,234 genes to known cancer genes (either those frequently mutated or implicated in cancer), the resulting overlap was less than anticipated. We queried known cancer genes through two different resources: the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (Kandoth et al., 2013) and the Cancer Gene Census (CGC) (Futreal et al., 2004). Of the 127 most frequently mutated genes identified by the TCGA, only 40 were targeted by these compounds. Additionally, the Sanger Institute (CGC) has catalogued genes that have been causally implicated in cancer. Only 134 of the 699 CGC genes were targeted by at least one compound screened in CCLs. Both limitations on the number of compounds screened as well as general limitations regarding ‘protein druggability’ likely play a role in explaining these proportions. Indeed, of the targeted genes in CGC, close to 60% are classified as oncogenes while 15% were classified tumor suppressor genes. Table S4 contains a list of all 1,234 druggable genes, the number of unique compounds that target this gene, and indicates if the gene overlaps with either the TCGA or CGC gene list.

To further investigate the role these druggable genes played in general cell biology and cancer pathways, we utilized the Broad Institute’s MSigDB database (Liberzon et al., 2015; Subramanian et al., 2005). We used the database’s Canonical Pathways gene set (Fabregat et al., 2018; Kanehisa et al., 2017; Liberzon et al., 2015; Milacic et al., 2012) (http://www.biocarta.com/) to represent general cell biology pathways as well as its Cancer Modules (Segal et al., 2004) and Oncogenic Pathways to represent cancer specific pathways. While the most commonly targeted canonical biology pathway was unsurprisingly “pathways in cancer,” many other biologically significant pathways are also impacted (Figure 2c). Indeed, 1,234 of the 1,329 canonical biology pathways are impacted by at least one compound, with a median of 21 unique drugs impacting a given pathway (Table S5). Regarding cancer specific pathways, 592 of the 620 pathways were impacted by at least one compound, with a median of 28 unique compounds per pathway (Table S6). Overall, the coverage of the majority of the general biology pathways and cancer specific pathways along with the proportion of drugs approved or in clinical trials suggests that CCL screens have, in general, selected a relevant yet broad array of compounds for screening.

4. Pan-Cancer Drug Screens

NCI60

Created in the late 1980’s, the NIH’s NCI60 initiative was one of the first major cancer cell line screening efforts. The panel originally had 60 cancer cell lines available for screening (Paull et al., 1989), but cell lines have been added and dropped from NCI60 since then such that the study currently has at least partial data for 74 cell lines representing ten different tumor types. The primary screening method for NCI60 is a 5-dose 48-hour screen using Sulforhodamine B staining for endpoint measurement, but, as of 2007, all newly screened compounds undergo a single high-dose test across the NCI60 cell lines and must satisfy a minimum inhibition criteria before undergoing the full 5-dose screen (see https://dtp.cancer.gov/discovery_development/nci-60 for further details). The NCI60 has screened over 100,000 compounds since 1989, with the results of approximately 50,000 of these being currently available for public access. In its long history, the NCI60 has been responsible for leading to a number of important cancer-related drug discoveries, including the identification of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib for the treatment of myeloma—one of the most rapidly developed and approved modern anticancer drugs (Shoemaker, 2006). The NCI60 effort also lead to development of the COMPARE algorithm (Paull et al., 1989), which allows compounds to be compared based on their patterns of inhibition within NCI60 and has helped identify the mechanisms of action for uncharacterized compounds (Shoemaker, 2006). In 2000, the NCI60 integrated the analysis of both molecular pharmacology and gene expression data in a large dataset for the first time, allowing them to cluster cells lines by both expression and drug sensitivity to reveal novel gene-drug relationships (Scherf et al., 2000). Since then, the CCLs used in NCI60 have been characterized extensively using methods including exome sequencing, various SNP arrays, sanger sequencing, mRNA arrays, a transporter protein array, a protein lysate array, and short tandem repeat fingerprinting. Cell line characterization and drug response data have been consolidated and are available through the CellMiner data portal (http://discover.nci.nih.gov/cellminer/) (Shankavaram et al., 2009). Growth inhibition data is also available from the NCI Developmental Therapeutics Program website (https://wiki.nci.nih.gov/display/NCIDTPdata/).

GlaxoSmithKline

Another early large-scale drug screening effort with publicly available data is a screen of 310 cancer cell lines from 24 different lineages using 19 drugs led by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) (Greshock et al., 2010). Greshock et al. determined genomic copy number (Affymetrix 500K “SNP chip”) and mRNA expression (Affymetrix GeneChip U133 Plus 2.0 Array) in each cell line and used a 72-hour 10-point dose-response screen using CellTiter-Glo to determine drug sensitivity. The 19 tested compounds included 5 targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, 4 targeting IGF-IR, 5 targeting mitosis, and several targeting receptor tyrosine kinases. Based on their results, they found cell lines representing a particular tumor type or molecular class to be acutely sensitive to certain drug classes with a common target. Drug sensitivity data for this screen is included in the original publication (Greshock et al., 2010). SNP array data can be accessed at ftp://caftpd.nci.nih.gov/pub/caARRAY/SNP/, and RNA expression data can be accessed at ftp://caftpd.nci.nih.gov/pub/caARRAY/transcript_profiling/.

Cancer Genome Project/Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (CGP/GDSC)

The Cancer Genome Project (CGP) is a collaboration between the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute (UK) and Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center (USA) which has performed several cancer screens in order to understand the interplay between genomic features and drug response. In 2012, they published a study which used a 72-hour 9-point dose-response assay using Resazurin (Sigma) staining to screen 130 compounds (31 approved clinical drugs, 47 in clinical trials, and 52 tool compounds) against a mean of 368 cell lines per drug (Garnett et al., 2012). Following genomic and transcriptional characterization of these cell lines, analyses were performed to identify biomarkers of sensitivity and resistance to cancer therapeutics. One of the results of these analyses was the identification of EWS-FLI1 as a biomarker for PARP inhibitor sensitivity.

In 2016, the project published an expansion to this effort (Iorio et al., 2016) in which a 72-hour 5-point drug screen using Resazurin (Sigma), CellTiter-Glo (Promega), or Syto60 (Invitrogen) staining to screen 249 oncology drugs in 1,073 unique cancer cell lines that had molecular annotation from the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC). Molecular data from 11,289 tumors from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), the International Cancer Genome Consortium, and other sources was then used to generate a set of clinically relevant genomic features which were then correlated with drug sensitivity in these cell lines using Elastic Net and Random Forest models. Their findings suggested that gene expression was their best predictor for pan-cancer drug sensitivity, and logic optimization for binary input to continuous output (LOBICO) modeling allowed >80% specificity in predicting drug sensitivity for 78% of the drugs tested.

The data from each of these studies has been deposited in the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC) database (www.cancerRxgene.org) (Yang et al., 2013). The database currently contains available screening data for 1073 cell lines and 249 compounds (most of which are targeted agents) as well as data for mRNA expression (Affymetrix Human Genome U219 Array), genomic copy number (Affymetrix SNP 6.0 array), methylation (Illumina HumanMethylation450 BeadChip), and whole exome sequencing (WES) (Illumina HiSeq 2000).

Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE)

The Broad Institute is responsible for generating several large-scale cancer cell line and drug sensitivity datasets, and, since their publication of the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) in 2012, they have continued to expand the cell lines and drugs they have screened. The initial study to assemble the CCLE dataset profiled 947 human cancer cell lines on the basis of mRNA expression (Affymetrix U133 plus 2.0 array), genomic copy number (Affymetrix 6.0 SNP array), and Illumina exome sequencing of 1651 genes (Barretina et al., 2012). Since then, the number of genomically characterized cell lines in CCLE has grown to more than 1000, with 503 of these having been used in a 72–84 hour 8-point dose-response screen using CellTiter-Glo (Promega) to determine pharmacological sensitivity to 24 anti-cancer compounds. Analysis of the screening data revealed several correlations between genomic markers and drug sensitivity, such as an association of SLFN11 expression with topoisomerase inhibitor efficacy—an association that has subsequently been confirmed by other groups, leading to ongoing investigation of SLFN11 as a potential biomarker (Ballestrero et al., 2017). Beyond the results of its drug screen, the CCLE has proven useful in that other Broad Institute screens have utilized the CCLE cell lines, allowing those screens to integrate the CCLE genomic data with their own pharmacological results. Genomic data for CCLE cell lines and the drug sensitivity screen are available at http://www.broadinstitute.org/ccle.

CTRP v1

In 2013, recognizing the need to expand the number of agents screened against cancer cell lines that have matched, comprehensive genomic data, researchers at the Broad published the Cancer Therapeutics Response Portal (CTRP) (Basu et al., 2013). A subset of 242 cell lines from the CCLE panel were chosen based on their correspondence with lineages studied in TCGA and also overlap with an shRNA cancer cell line screen, Project Achilles (Cheung et al., 2011). A total of 354 small molecules, including 35 FDA-approved drugs, 54 clinical candidates, and 265 probes, were selected based on two main criteria: 1) high selectivity for their target and 2) targeting multiple nodes in cell signaling pathway. Similar to CCLE, these compounds were screened across the 242 cell lines in a 72 hour 8-point dose-response screen using the CellTiter-Glo assay (Promega) to measure viability. Drug sensitivity data for CTRP v1 are available at http://www.broadinstitute.org/ctrp.v1/.

CTRP v2

In late 2015, Broad researchers published the Cancer Therapeutic Response Portal Version 2 (CTRP v2) (Seashore-Ludlow et al., 2015). This newest expansion includes 887 cancer cell lines, 827 of which have been characterized as part of the CCLE, representing 25 different lineages. A 72-hour 16-point dose-response screen using CellTiter-Glo (Promega) was used to assess sensitivity of these cell lines to 496 compounds—including 70 FDA approved drugs, 100 clinical candidates, and 311 small-molecule probes collectively exploiting over 250 protein targets. Of the small-molecule probes, over half had no known protein target. To examine this large dataset, Seashore-Ludlow et al. developed the Annotated Cluster Multidimensional Enrichment (ACME) analysis algorithm which allows for the identification of relationships between tested compounds and shared genetic features between cell lines, providing insights into the compounds’ mechanisms of action. Drug sensitivity data and ACME clustering analysis for CTRP v2 are available at http://www.broadinstitute.org/ctrp.v2.2/.

Genentech Cell Line Screening Initiative (gCSI)

A recently completed drug screen by Genentech independently assessed 429 cancer cell lines and 16 drugs that had been previously evaluated in CCLE and/or GDSC (Haverty et al., 2016). A 72-hour 9-point dose-response screen using CellTiter-Glo (Promega) was used to determine drug sensitivity, and 24 cell lines and 4 drugs were selected for a follow up screen to assess the impact of using different cell viability assays on the screen’s results. The follow-up screen varied the use of CellTiter-Glo versus Syto60 (Invitrogen) to measure cell viability, 10% versus 5% FBS to supplement culture media, and fixed versus variable seeding to plate cells. The results indicated that conditions which allowed cells to become overconfluent (i.e. via overseeding or using media with a high FBS content) led to an underestimation of inhibition and that using Syto60 resulted in less precise results than using CellTiter-Glo. It was also shown that gCSI correlates more closely with CCLE than with GDSC, consistent with CCLE having a more similar screening strategy to gCSI than GDSC. However, the study ultimately found that gCSI, CCLE, and GDSC identified sensitive/resistant cell lines and candidate biomarkers for the tested drugs in a largely consistent manner. Data from this screen are included in the original publication (Haverty et al., 2016).

Institute for Molecular Medicine Finland (FIMM)

In another effort to assess consistency between the CCLE and GDSC datasets, a group from the FIMM released screening data from their compound testing dataset including 52 compounds and 50 cell lines that overlap between FIMM and either GDSC, CCLE, or both (Mpindi et al., 2016). The FIMM dataset used a 5-point dose-response screen with a CellTiter-Glo (Promega) viability readout. Following re-analysis of the three studies to generate standardized drug sensitivity scores, the authors concluded that harmonizing the data by accounting for the dosing range increased the consistency among the CCLE, GDSC and FIMM datasets. They also found that a higher correlation exists between the FIMM and CCLE datasets than between either dataset and the GDSC, which they suggest is due to the FIMM and CCLE studies being more similar in experimental design with each other than with the GDSC—indicating that standardized assay design may be important for achieving consistency between drug screens performed in separate laboratories. Drug response data for the released FIMM data is included in the original publication (Mpindi et al., 2016).

NCI-ALMANAC

Being completed in early 2017, the NCI-ALMANAC dataset was designed to be used for identifying effective double agent combinations of FDA-approved oncology drugs for cancer therapy (Holbeck et al., 2017). The screen was performed at NCI’s Fredrick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, SRI International, and the University of Pittsburgh, ultimately producing data for 104 drugs and 5334 drug combinations in 60 cell lines from the NCI60. Experiments at the NCI were performed according to the NCI60 testing protocol (see NCI60 section of this review) in a 96-well format with a 48-hour Sulphorhodamine B endpoint. Single agents were tested at 5 concentrations and combinations were tested with 5 concentrations of the first agent and 3 concentrations of the second agent using duplicate wells. Experiments performed at SRI International and the University of Pittsburgh used a 384-well plate format with a 48-hour CellTiter-Glo (Promega) endpoint. Single agents were tested at 3 concentrations and combinations were tested with 3 concentrations of the first agent and 3 concentrations of the second agent using single wells. In order to identify drug combinations that showed more than additive growth inhibition, a modified form of Bliss independence was used to calculate a “ComboScore”. This revealed a number of effective combinations, 44 of which were selected for testing in one or more mouse models. These tests revealed 21 combinations showing greater than single-agent activity in vivo, and, in light of these results, two phase-I clinical trials were started to evaluate the clinical safety of Bortezomib + Clofarabine and Paclitaxel + Nilotinib combinations respectively ( and ). NCI-ALMANAC data can be accessed at https://dtp.cancer.gov/ncialmanac.

5. Cancer Specific Drug Screens

Daemen et al. Breast Cancer Screen

In 2013, a group from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory published a drug screen specifically focused on breast cancer, containing data for 70 cell breast cancer cell lines tested against 88 therapeutic compounds (Daemen et al., 2013). The study used a 72-hour 9-point dose-response screen with CellTiter-Glo (Promega) to determine drug sensitivity, and each cell line was assessed for DNA copy number (Affymetrix SNP6.0), mRNA expression (Affymetrix U133A and Exon 1.0 ST arrays), RNA sequencing (RNAseq) (Illumina Genome Analyzer IIx), promoter methylation (Illumina Methylation27 BeadChip), protein abundance (Reverse Protein Lysate Array), and WES (Illumina Genome Analyzer IIx). Daemen et al. used this information to create least squares support vector machine and random forest models for predicting drug response in cell lines. These models suggested that the response for 13 of the compounds could be well predicted using transcriptional data alone, and the application of transcriptome based predictive models to RNAseq data from patient tumors that had been treated with tamoxifen or valproic acid allowed for relatively accurate predictions of which patients were responders or non-responders. Raw drug response data for this study is included in the original publication (Daemen et al., 2013), and genomic data is available at https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ega (copy number: EGAS00000000059 & EGAS00001000585), https://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress (expression array: E-TABM-15 & E-MTAB-181), or https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/ (RNAseq/WES: GSE48216, Methylation: GSE42944).

Colorectal Cancer Organoid Screen

In 2015, a collaboration between the Hubrecht Institute, the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, and the Broad Institute published the results of an 83 compound drug screen performed against 19 colorectal cancer organoids (van de Wetering et al., 2015). In addition to the drug screen, the organoids were characterized via WES (Agilent V2 capture kit with HighSeq2500), total RNA expression array (Affymetrix Human Gene 2.0ST Array), and RNAseq (Illumina NextSeq500). The results revealed that organoids clustered into groups defined by general sensitivity or resistance to the compounds screened and confirmed the association between loss-of-function TP53 mutations and resistance to nutlin-3a. Perhaps more importantly, the screen established that multi-clonal organoids can be used for high-throughput drug screening. Drug sensitivity data for the screen is included in the original paper (van de Wetering et al., 2015), and genomic data is available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/ (expression array: GSE64392, RNAseq: GSE65253).

NCI-Sarcoma Project

In 2015, the Developmental Therapeutics Program (DTP) at the NCI published a sarcoma specific screen in which 64 CCLs were screened against 100 FDA approved drugs and 345 investigational agents in a 96-hour 9-point screen with an alamar blue endpoint (Teicher et al., 2015). The cell lines were additionally characterized via total RNA expression array (Affymetrix Human Exon 1.0ST Array) and microRNA profiling (NanoString human miRNA probeset). Analysis of the screen revealed sensitivities of certain types of sarcoma to specific drugs, including a sensitivity of Ewing’s sarcoma to alisertib and barasertib, which are both currently in clinical trials. Drug response and RNA expression data for this study can be downloaded from https://sarcoma.cancer.gov/sarcoma/, and RNA and miRNA expression data can be accessed from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/ (GSE68591 and GSE69470 respectively).

NCI-SCLC Project

In 2016, the DTP at the NCI published another cancer screen, this time focusing on small cell lung cancer (SCLS) (Polley et al., 2016). 70 lung CCLs were screened against 103 FDA approved oncology drugs and 423 experimental agents, and drug sensitivity was assessed using a 96 hour 9-point screen with ATP Lite (Perkin Elmer Inc., Waltham, MA) as the endpoint readout. The cell lines were additionally characterized via total RNA expression array (Affymetrix Human Exon 1.0ST Array) and miRNA profiling (NanoString human miRNA probeset), and the study found correlations between the expression of several genes/miRNAs and sensitivity to select drugs. The study’s drug response, RNA expression, and miRNA expression data are available at https://sclccelllines.cancer.gov/sclc/.

PRISM NSCLC Screen

Another 2016 drug screen was published by the Broad Institute, which introduced a novel drug screening method called PRISM and focused on non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (Yu et al., 2016). Instead of the traditional strategy of testing compounds against one cell line at a time and measuring effectiveness using viability assays, PRISM tests compounds against mixtures of cell lines in which each cell line has been genetically labeled via lentiviral barcoding. Following compound or control treatment, the growth of each cell line in the mixture is determined by quantifying the genetic tags using a Luminex FlexMap detector. This allows high-throughput testing of cell lines in drug screens while also providing a method to examine how a cell line responds to a compound when in the presence of other cell lines. Yu et al. applied this technique to perform a screen of 96 cell lines (86 NSCLC + 10 others) against 8,000 diversity-oriented synthesis (DOS) molecules in a single dose and 400 tool compounds or current oncology drugs in 8 or 16 doses. Cell lines were assayed in mixtures of 25–27 cell lines per group and treated for 5 days prior to barcode quantification. An 8-dose validation was subsequently performed for the 199 DOS compounds which showed >80% growth inhibition in at least one cell line in the initial screen, with the results from 139 of the 199 compounds being successfully validated. Yu et al. also tested PRISM in vivo, where they tested erlotinib, an EGFR inhibitor, against a mixture of 24 cell lines in a 16-day treatment schedule in NOD-SCID-IL2Rgammanull mice. The screen distinguished a robust difference in sensitivity between the 4 EGFR-mutant cell lines and the 20 wild-type EGFR cell lines, suggesting that PRISM may be successfully applied as a semi-high-throughput method for assessing drug sensitivity in vivo. While SNP fingerprinting was the only genomic analysis performed by Yu et al., 80 of the cell lines used in their study overlap with CCLE and, therefore, have extensive genomic information available for them at http://www.broadinstitute.org/ccle. Drug-response data and SNP fingerprinting data for this study is included with the original publication (Yu et al., 2016).

6. shRNA and CRISPR/CAS9 Screens

Project Achilles

Project Achilles (http://www.broadinstitute.org/achilles) is an effort by the Broad Institute which has performed genetic perturbations across the genomes of hundreds of CCLs in order to identify genetic vulnerabilities and gene-dependencies in cancer. The project currently consists of four available datasets—Achilles 2.0, Achilles 2.4.3, Achilles 2.20.2, and Achilles 3.3.8. Achilles 2.0 (Cheung et al., 2011) contains pooled short hairpin RNA (shRNA) screen data for 102 cell lines previously annotated by CCLE. The screen included 54020 shRNAs targeting 11,194 gene products which were incubated with CCLs for at least 16 doublings. Following this incubation, shRNA abundance was quantified with microarray hybridization. Achilles 2.4.3 (Cowley et al., 2014) sought to improve on this screening method by using next generation sequencing (Illumina) to quantify shRNA abundance rather than microarray hybridization. The study re-assessed the 102 cell lines from Achilles 2.0 as well as 143 additional cell lines using the same shRNA screen from Achilles 2.0, ultimately obtaining high quality data from 216 cell lines. Genomic copy number data was also collected for these cell lines by either obtaining data from the CCLE or by independently genotyping the cell lines (Affymetrix 6.0 SNP array). Achilles 2.20.2 (Tsherniak et al., 2017) is the most recent expansion of Achilles, adding an additional 285 cell lines to the screen and nearly doubling the number of shRNAs for a dataset. In total 501 cell lines were incubated with >107,000 shRNAs targeting >25,000 gene products for either 16 doublings or 40 days. The results of the screen were used to develop the DEMETER analytical framework for separating on- and off-target effects in shRNA screens and to build the initial framework for the Broad Institute’s Cancer Dependency Map (https://depmap.org/broad/). Achilles 3.3.8 (Aguirre et al., 2016) departs from using an shRNA based screen by instead employing a genome scale CRISPR/Cas9 screening technique. 123,411 single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting 19,050 genes, 1,864 miRNAs, and 1,000 negative controls were screened against 33 cancer cell lines for either 21 or 28 days, and then quantified using next-generation sequencing. Copy number alterations after sgRNA infection were also assessed via SNP array, revealing a strong correlation between copy number alterations, cell viability, and the number of sgRNA target loci. This led to the conclusion that CRISPR/Cas9 targeting leads to gene-independent alterations in cell proliferation. The implications of this, along with efforts to circumvent the issue, are discussed later in this paper.

The results of the Achilles screens have been consolidated along with other relevant data within the NCI’s Cancer Target Discovery and Development Network data portal (https://ctd2.nci.nih.gov/dataPortal/) and are also available through the project Achilles data portal (https://portals.broadinstitute.org/achilles). Project Achilles also offers several tools for analyzing screening data, which are also available at their website (https://portals.broadinstitute.org/achilles/resources#tools).

Munoz et al.

In 2016, a group from the Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research published a comparison of genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 dropout screening to genome-wide shRNA screening (Munoz et al., 2016). Five cancer cell lines were screened using both methods, and the results were compared to determine the relative sensitivity and accuracy of the methods. Munoz et al. found that the CRISPR/Cas9 screen was able to detect many more essential genes than the shRNA screen and that this was at least partially due to an inefficient knockdown of some genes by a subset of the shRNAs targeting that gene. In agreement with the Achilles CRISPR/Cas9 screen (Aguirre et al., 2016), Munoz et al. also found that regions of amplification led to false-positive hits in the CRISPR/Cas9 screen due to induction of the DNA damage response, with regions having more than 6 genomic copies being especially vulnerable and regions with as few as one extra copy also showing above average growth inhibition. The study also found that sgRNAs matching off-target sites could lead to cell lethality via the DNA damage response, highlighting the importance of ensuring that sgRNAs are specific in the context of the entire genome. Processed screening and RNAseq for this study are included in the original publication (Munoz et al., 2016).

Tzelepis et al.-AML

In 2016, a group from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute published the results of a genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 screen of 5 AML cell lines, 1 colorectal cancer cell line, and 1 fibrosarcoma cell line (Tzelepis et al., 2016). During optimization of the protocol, Tzelepis et al. noticed that sgRNAs showed nucleotide biases between positions 16 and 20 of their sgRNAs when compared to efficient guides. To correct for this, the authors generated a new library using a sgRNA scaffold design that has been previously optimized for CRISPR imaging (Chen et al., 2013) and found that the new library both eliminated the nucleotide bias and greatly increased the number of genes that were statistically depleted in the screen. The new library ultimately allowed the group to identify 492 AML-specific cell essential genes, including 227 genes which are targets of currently available drugs. Validation of a set of 14 of these genes revealed a high degree of correlation between drug sensitivity and their CRISPR/Cas9 results, and in vivo inhibition of one of these genes, KATA2, was found to prolong survival of MOLM-13-Cas9 transplanted Rag2−/−,Il2rg−/− mice. This suggests that relatively small CRISPR/Cas9 screens are capable of informing drug development in a disease-specific manner, but that careful optimization of these screens is necessary. Processed screening data is include with the original publication (Tzelepis et al., 2016) and raw CRISPR sequencing and RNAseq data are available at http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena (CRISPR: ERP005600 & ERP008475; RNAseq: ERP006662 & ERP003933).

Wang et al.-AML

Another genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 screen in AML cell lines was published in 2017 by a group from the Broad Institute (Wang et al., 2017) in which 14 AML cell lines with varying RAS pathway statuses were screened. In line with previous studies (Aguirre et al., 2016; Munoz et al., 2016), Wang et al. found that regions of genomic amplification led to false-positive hits. To correct for this, the group developed a sliding window score to exclude contiguous regions of the genome that were depleted in the screen, and they further refined their analysis of essential genes by assessing correlation between the dropout rates of genes within the same pathways. This correlation analysis allowed the researchers to identify the pathways to which several uncharacterized genes belonged, and the study uncovered 5 genes essential in AML cell lines in the context of oncogenic but not normal RAS signaling. Processed screening data is included with the original publication (Wang et al., 2017) and raw sgRNA counts are available at http://sabatinilab.wi.mit.edu/wang/2017.

7. Similarity and Consistency between CCL Screens

Many of the CCL screens we described above have shared elements in terms of the cancer types, cell lines, and compounds that they screened. This is important both because it impacts the number of unique drug-cell line observations made by each CCL screen and because it provides an opportunity to gauge the reproducibility of screening results between different institutions and studies. As such, here we discuss the extent of similarity, overlap, and reproducibility among these screens.

Tissue Composition and Cell Line Overlap

To investigate how similar the CCL screens are in terms of the types of cancers they screened, we used the information outlined in section 3 (table S2) to determine the relative abundance of a cancer type in the pan-cancer datasets. Figure 3a shows that the proportion of represented cancer types is largely similar across pan-cancer datasets, with the most prominent deviations from the average occurring in the datasets that screened the fewest cell lines. For instance, the NCI-60 and NCI-ALMANAC screening sets omit sarcomas and pancreatic cancer cell lines, the Achilles v3.3.8 dataset focuses more specifically on sarcomas and pancreatic cancers than other datasets, and the FIMM dataset has a larger proportion of haematopoietic/lymphoid, breast, and female reproductive cancers. However, on the whole, many of the large pan-cancer studies represent the various cancer types in similar proportions.

Figure 3. Composition and Overlap of CCL Screens.

A) Cell line tissue type vs. dataset. Tissue type was determined by bioinformatic and manual curation using Cellosaurus, the BioSample database, COSMIC, or annotations provided by the datasets themselves, and then similar cancer types were grouped in the broad groups shown. The data for this figure is included in Table S2. B) Heatmap of cell line overlap between reviewed studies. Overlap is based on data from Table S2, with each color scale being relevant to the amount of overlap each column study has with the study in that row. C) Heatmap of compound overlap between reviewed drug screen studies. Overlap is based on data from Table S3, with each color scale corresponding to the amount of overlap each column study has with the study in that row. Note that the 8,000 diversity-oriented synthesis molecules tested in PRISM are excluded in this plot.

Some of this similarity can be explained by the fact that many of the pan-cancer datasets use highly overlapping sets of CCLs for their screens (Figure 3b, Figure S1a). For example, CTRP v2 contains at least 79% of the cell lines used in any other Broad Institute screen, and NCI-ALMANAC is entirely composed of CCLs from NCI60. Of the 1,561 unique CCLs screened across all studies, 594 are unique to a single study, 229 are included in two studies, and 738 are included in three or more studies (Figure S1b), with some cell lines being included in most screens—such as the A549, a lung adenocarcinoma line which is included in 14 of the 20 datasets. The 594 CCLs that are unique to a single screen are mostly used in either GDSC or CTRP v2, the two datasets with the greatest number of cell lines, though several of the single-cancer screens also contribute a number of unique cell lines (Figure S1c).

Considering CCL overlap and genetic uniqueness within datasets may be useful to researchers when attempting to validate findings between screens since validation in a dataset which is independent in both its screening data and its cell lines lends stronger support to the initial findings than validation in a dataset which simply has independent measurements from the same cell lines used in the initial discovery. On the other hand, having a high degree of CCL overlap among screens does provide several advantages. First, it allows researchers to measure the consistency between different studies which have also screened the same compounds (a topic we review later in this section). Second, it often allows for increased knowledge about these overlapping CCLs as a result of their being genomically and pharmacologically characterized more fully than if the CCL were studied by only a single group. Finally, it allows new studies to use previously generated genomic data and CCL repositories instead of needing to generate those resources de novo. This makes new screens less expensive and faster to complete. In the end, these advantages will need to be weighed against the potential for genetic drift of these CCLs and the need for expanding the genetic diversity in future CCL screens.

Compound Overlap

In total, there are over 50,000 unique screening agents with publicly available data in these datasets, most of which can be attributed to the NCI-60. The NCI-60 has data for close to 49,300 compounds with almost 49,000 of these agents being unique to the NCI-60 screen (Figure S2c). However, it should be noted that the majority of these compounds failed to meet the NCI-60’s screening standards by either missing the minimum range requirements, not passing a minimum consistency among replicates, or by having results for fewer than 35 cell lines. Taking this into consideration, only ~21,000 compounds are both publicly available from the NCI-60 and passed their standards. Comparatively, the other CCL screens we reviewed screened a combined total of approximately 2,800 agents, of which about 1,300 are unique (Table S3).

To determine overlap, we made use of PubChem’s Identifier Exchange Service (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/idexchange/idexchange.cgi) to identify synonyms for all named compounds in the original datasets and converted these synonyms to PubChem IDs. We then matched PubChem IDs back to their original name, and used the PubChemID(s) identified to match the compounds among the datasets. This ensured the highest degree of overlap, and the results were manually checked and curated as needed to ensure correctness. This method also identifies overlap in highly related compounds, for example irinotecan and its active metabolite SN-38. In most circumstances, overlap based on very close relatedness such as this was considered appropriate and kept. Table S3 lists all compounds under their original name along with the corresponding database, their harmonized PubChemID and name, as well as their clinical status, mechanism of action and gene targets from the Broad Drug Repurposing Hub (mentioned in section 3 of this review).

Similar to the relatively high overlap among cell lines in these datasets, there was an appreciable amount of overlap among the drugs screened (Figure 3d). The exact number of compounds that overlap between any two datasets is shown in Figure S2a. There are 766 compounds overlapped in at least 2 datasets, about 240 of which overlapped in 4 or more datasets (Figure S2b).

Interestingly, the median overlap between any two datasets is close to 22% and the median cell line overlap between any two datasets is close to 27%. Thus, while each dataset contains unique information (Figure S2c), there is often enough overlap for performing cross-validation as well as to investigate the consistency of these datasets.

Consistency among Screens

Concerns regarding the consistency of these CCL screen datasets heightened in 2013 when a study reported a large degree of inconsistency between the CCLE and GDSC datasets (Haibe-Kains et al., 2013). However, the statistical methods and approaches employed in this study were subsequently called into question and multiple follow-up studies that reanalyzed the results concluded that both the pharmacological and genomic data are largely consistent and reproducible between these datasets (Bouhaddou et al., 2016; Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia Consortium and Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer Consortium, 2015; Geeleher et al., 2016; Haverty et al., 2016; Mpindi et al., 2016; Pozdeyev et al., 2016).

Beyond reanalyzing the data, these follow-up papers also proposed potential reasons for any remaining inconsistencies. Aside from technical considerations (which were investigated in the gCSI and FIMM studies and summarized in their respective descriptions in section 4), there was a consensus that a major source of variation was due to the abundance of insensitive cell lines for a majority of compounds tested. That is, often when compounds target specific cancer dependencies, their pharmacological metrics are dominated by cells insensitive to the compound’s effects. When comparing the IC50 or area under the drug dosage and response curve (AUC) metrics, the few sensitive cell lines appear as outliers while the technical variability (noise) can then dominate the correlation of these statistics.

Additionally, problems with consistency are compounded when the datasets use different dose ranges or when IC50s are used for comparison. Mpindi et al., for example, investigated the effect of dose ranges by harmonizing the data to the same dose range, and found improved agreement between the datasets when these differences were accounted for. Several studies called into question the utility of the IC50 metric in comparing such large-scale datasets for two major reasons (Bouhaddou et al., 2016; Haverty et al., 2016; Pozdeyev et al., 2016). First, it was noted that extrapolating the IC50 when it lies beyond the maximum dose tested often leads to increased variability, which would further decrease consistency among the studies. Second, several studies argued that IC50s do not capture the diversity of pharmacological profiles, and thus reanalyzed the data using variations on the AUC metric, which better combines information on the potency (IC/EC50) and efficacy (i.e. maximal activity value or Emax) of the drug (Bouhaddou et al., 2016; Haverty et al., 2016; Mpindi et al., 2016; Pozdeyev et al., 2016). Both harmonizing the dose range and analyzing the data with AUCs instead of IC50 helped to account for some of the variability expected from insensitive cell lines and thus allowed for a more accurate assessment of consistency.

Technical variability exists in all biological experiments, and CCL drug screens are no exception. A benefit of having overlap among these screens is that it allows for cross-validation when identifying novel drugs or cancer/molecular settings for existing drugs. However, in conducting cross-validation, one needs to keep in mind all potential sources of variability and take these into consideration when determining if diverging results from one study to another represents something truly biological. That said, all in all, the results from CCLE and GDSC (along with FIMM and gCSI) have been found to be largely consistent.

8. Recent Developments in CCL Screening and Novel Opportunities

PRISM

As described in section 5, the Broad Institute recently developed a novel drug screening method called PRISM in which CCLs are genetically labeled via lentiviral barcoding and mixed together prior to compound exposure (Yu et al., 2016). This method allows for much higher throughput than traditional screening techniques as it allows roughly 25 CCLs to be screened against a compound in a single well as compared to a single cell line per well with traditional methods. The method also provides several novel opportunities to researchers as it allows CCLs (and non-cancer cell lines) to be mixed at known ratios during compound exposure. This could potentially allow in vitro systems to more closely resemble an in vivo environment by adding stromal and immune cells to the system while retaining the ability to measure a compound’s effect specifically on CCLs, and it allows for high-throughput testing of the effects of compound exposure in poly-clonal mixtures of CCLs. As demonstrated by Yu et al., the method has been successfully adapted to create a semi-high-throughput in vivo screening method by implanting tagged mixtures of CCLs into mice and quantifying changes in the CCL ratio of the tumor following a course of compound treatment.

Organoids

Another recent advance on the cell line side of CCL screens has come with the successful development of high-throughput compound screening in cancer organoids (van de Wetering et al., 2015). As organoids are grown in a 3D matrix and retain some degree of the poly-clonality present in the original tumor, this may provide another method to assess the effect of compound treatment on poly-clonal mixtures of cancer cells in an environment that is potentially more clinically relevant than 2D culture.

Efforts to Increase the Number of Available Cancer Cell Lines

As others have reviewed (Williams and McDermott, 2017), there is a pressing need for an increase in the number of available in vitro cancer models to meet the challenge of faithfully recapitulating the genomic and phenotypic heterogeneity of human cancers. As large-scale sequencing efforts in patient tumors has revealed complex diversity and sub-grouping within cancer types, efforts have begun to generate in vitro cancer models which capture this diversity. Two large projects with this goal have emerged in recent years. One is the Cancer Cell Line Factory at the Broad Institute, which aims to generate more than 10,000 CCLs for use by the research facility (Boehm and Golub, 2015). The other is the Human Cancer Model Initiative collaboration between the NCI, Cancer Research UK, the Sanger Institute, and the foundation Hubrecht Organoid Technology, which aims to create as many as 1000 new in vitro cancer models with detailed clinical information, carefully controlled culture condition, and modern culture techniques such as conditionally reprogrammed cells and organoids (https://ocg.cancer.gov/programs/HCMI). Patient-derived tumor xenografts have also been explored as a means of expanding the genetic diversity of pre-clinical drug screens (Gao et al., 2015). It is the hope that these efforts will greatly increase the diversity and clinical relevance of available pre-clinical cancer models for future screens.

Drug Combinations

The recent publication of the NCI-ALMANAC dataset demonstrated both the feasibility and utility of testing drug combinations in a large-scale CCL screen (Holbeck et al., 2017). As discussed in the NCI-ALMANAC description in section 4, the effort screened double-agent combinations of 104 drugs across 60 CCLs, leading to the initiation of two clinical trials for promising drug combinations—Bortezomib + Clofarabine () and Paclitaxel + Nilotinib (). While it remains to be seen how effective these combinations are in the clinic, there is hope that such screens may help identify novel uses for already developed drugs in the fight against cancer as well as treatments which concurrently target sub-clones of patient tumors with distinct pharmacological sensitivities.

shRNA and CRISPR/Cas9 screens

While shRNA and CRISPR/CAS9 screening allows researchers to assess gene dependence in CCLs at a genome-wide scale, these technologies are much younger than traditional drug screening techniques, and care must be used both in performing and interpreting these screens. Evidence suggests that current shRNA screens may be limited in sensitivity compared to CRISPR/Cas9 screens, possibly due to uneven knockdown by shRNAs targeting the same gene or a need for complete gene inactivation to see an effect (Munoz et al., 2016). CRISPR/Cas9 screens, on the other hand, may be limited in sensitivity by inefficient guide RNAs (Tzelepis et al., 2016) and carry a significant liability for detecting false positives in regions of copy number amplification or for guide RNAs which match multiple sites within the genome (Aguirre et al., 2016; Munoz et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2017).

As the technologies mature, however, these drawbacks are gradually being overcome. For shRNA screens, constantly expanding shRNA libraries tested against large sets of CCLs with improved algorithms for detecting on- and off-target shRNA effects have led to the identification of hundreds of potential cancer dependencies, creating a framework for prioritizing therapeutic targets in these cancers (Tsherniak et al., 2017). For CRISPR/Cas9 screens, modified sgRNA design algorithms have been shown to significantly improve screening sensitivity (Tzelepis et al., 2016), and algorithms have been developed to bioinformatically remove false positives (Wang et al., 2017). So far, these advances have allowed researchers to use CRISPR/Cas9 screens to distinguish between genes essential in AML cell lines with compromised RAS pathways and those essential in AML lines with wild-type RAS signaling (Wang et al., 2017); and to identify the KATA2 gene as a promising target in AML (Tzelepis et al., 2016). As these technologies continue to improve, they promise to provide invaluable assistance in identifying and prioritizing novel therapeutic targets for cancer treatment.

9. Considerations for Future Screens

Over the past three decades, CCL screens have done much to aid in the development and understanding of cancer treatments, and they have also done much to improve themselves over time. That said, as with all cancer research, much remains to be done. Future CCL screens must carefully compare traditional immortalized cell line models with newer methods for cell line generation to determine the clinical relevance and consistency of each. Likewise, ethnicity, age, and gender must all be considered for their possible implications on treatment discovery and efficacy. The genomic and phenotypic heterogeneity within each cancer type must be considered in efforts to identify effective treatments for ever more specific groups of cancers and patients. This will likely involve greatly expanding the number of CCLs screened in future studies, which may be especially important for identifying biomarkers relevant to targeted therapies, which are expected to only be effective in a subset of cell lines tested. Indeed, previous reports have suggested that up to 85% of the cell lines tested in some screens are insensitive to the majority of tested compounds (Bouhaddou et al., 2016), placing serious limits on the power to identify biomarkers associated with response to those treatments—limits which future screens will need to overcome.

Likewise, ongoing research is needed into the effect of different screening methodologies on the reproducibility between studies and institutions, and careful standards must continue to be considered and improved for maintaining the integrity and identity of screened CCLs. This is of particular concern for new studies which rely on previously generated genomic data for their cell lines, as genetic drift, contamination, or changes in culture conditions could meaningfully confound correlations between genomic/transcriptomic data and the screening results.

Throughout the history of cancer cell line screening, the technology and models at hand have limited the scope and findings of cell line screens. While it is simple to suggest the addition of more cell lines to bolster the diversity of screening efforts, this will require continual development of new models to make capturing tumor heterogeneity and adequately probing specific cancer targets feasible. Encouragingly, many of these considerations are already well recognized and being addressed. It may be that the use and combination of current technologies will overcome these barriers and allow for the screening of therapies in diverse cell lines cultured in increasingly relevant biological conditions. One can envision the continued expansion and improvement of available models as well as the combination of various new tools/systems for drug screening. This provides a promising future for CCL screens.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

A.L, R.G. and J. F received funding support from the University of Chicago Cancer Biology Training program grant [T32 CA009594]. R.S.H. received support from a research grant from the Avon Foundation for Women; the NIH/ NIGMS [grants K08GM089941, U01GM61393]; the NIH/NCI [grant R21 CA139278]; and a Circle of Service Foundation Early Career Investigator award.

These funding sources had no involvement in the design, creation, or submission of this manuscript.

Abbreviations:

- CCL

Cancer Cell Line

- CCLE

Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia

- CGC

Cancer Gene Census

- COSMIC

Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer

- DTP

Developmental Therapeutics Program

- FIMM

Institute for Molecular Medicine Finland

- gCSI

Genentech Cell Line Screening Initiative

- GDSC

Genomic of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer

- NSCLC

Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

- RNAseq

RNA Sequencing

- sgRNA

Single Guide RNA

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- WES

Whole Exome Sequencing

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement:

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aguirre AJ, Meyers RM, Weir BA, Vazquez F, Zhang C-Z, … Hahn WC. (2016). Genomic Copy Number Dictates a Gene-Independent Cell Response to CRISPR/Cas9 Targeting. Cancer Discovery, 6, 914–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballestrero A, Bedognetti D, Ferraioli D, Franceschelli P, Labidi-Galy SI, … Zoppoli G. (2017). Report on the first SLFN11 monothematic workshop: from function to role as a biomarker in cancer. Journal of Translational Medicine, 15, 199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barretina J, Caponigro G, Stransky N, Venkatesan K, Margolin AA, … Garraway LA. (2012). The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature, 483, 603–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett T, Clark K, Gevorgyan R, Gorelenkov V, Gribov E, … Ostell J. (2012). BioProject and BioSample databases at NCBI: facilitating capture and organization of metadata. Nucleic Acids Research, 40, D57–D63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu A, Bodycombe NE, Cheah JH, Price EV, Liu K, … Schreiber SL. (2013). An Interactive Resource to Identify Cancer Genetic and Lineage Dependencies Targeted by Small Molecules. Cell, 154, 1151–1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehm JS, & Golub TR. (2015). An ecosystem of cancer cell line factories to support a cancer dependency map. Nature Reviews Genetics, 16, 373–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouhaddou M, DiStefano MS, Riesel EA, Carrasco E, Holzapfel HY, … Birtwistle MR. (2016). Drug response consistency in CCLE and CGP. Nature, 540, E9–E10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia Consortium, & Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer Consortium. (2015). Pharmacogenomic agreement between two cancer cell line data sets. Nature, 528, 84–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Gilbert LA, Cimini BA, Schnitzbauer J, Zhang W, … Huang B. (2013). Dynamic Imaging of Genomic Loci in Living Human Cells by an Optimized CRISPR/Cas System. Cell, 155, 1479–1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung HW, Cowley GS, Weir BA, Boehm JS, Rusin S, … Hahn WC. (2011). Systematic investigation of genetic vulnerabilities across cancer cell lines reveals lineage-specific dependencies in ovarian cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108, 12372–12377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa RLB, & Gradishar WJ. (2017). Differences Are Important: Breast Cancer Therapy in Different Ethnic Groups. Journal of Global Oncology, 3, 281–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowley GS, Weir BA, Vazquez F, Tamayo P, Scott JA, … Hahn WC. (2014). Parallel genome-scale loss of function screens in 216 cancer cell lines for the identification of context-specific genetic dependencies. Scientific Data, 1, 140035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daemen A, Griffith OL, Heiser LM, Wang NJ, Enache OM, … Gray JW. (2013). Modeling precision treatment of breast cancer. Genome Biology, 14, R110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabregat A, Jupe S, Matthews L, Sidiropoulos K, Gillespie M, … D’Eustachio P. (2018). The Reactome Pathway Knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Research, 46, D649–D655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes SA, Beare D, Boutselakis H, Bamford S, Bindal N, … Campbell PJ. (2017). COSMIC: somatic cancer genetics at high-resolution. Nucleic Acids Research, 45, D777–D783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futreal PA, Coin L, Marshall M, Down T, Hubbard T, … Stratton MR. (2004). A census of human cancer genes. Nature Reviews Cancer, 4, 177–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H, Korn JM, Ferretti S, Monahan JE, Wang Y, … Sellers WR. (2015). High-throughput screening using patient-derived tumor xenografts to predict clinical trial drug response. Nature Medicine, 21, 1318–1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnett MJ, Edelman EJ, Heidorn SJ, Greenman CD, Dastur A, … Benes CH. (2012). Systematic identification of genomic markers of drug sensitivity in cancer cells. Nature, 483, 570–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geeleher P, Gamazon ER, Seoighe C, Cox NJ, & Huang RS. (2016). Consistency in large pharmacogenomic studies. Nature, 540, E1–E2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greshock J, Bachman KE, Degenhardt YY, Jing J, Wen YH, … Wooster R. (2010). Molecular Target Class Is Predictive of In vitro Response Profile. Cancer Research, 70, 3677–3686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haibe-Kains B, El-Hachem N, Birkbak NJ, Jin AC, Beck AH, … Quackenbush J. (2013). Inconsistency in large pharmacogenomic studies. Nature, 504, 389–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haverty PM, Lin E, Tan J, Yu Y, Lam B, … Bourgon R. (2016). Reproducible pharmacogenomic profiling of cancer cell line panels. Nature, 533, 333–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holbeck SL, Camalier R, Crowell JA, Govindharajulu JP, Hollingshead M, … Doroshow JH. (2017). The National Cancer Institute ALMANAC: A Comprehensive Screening Resource for the Detection of Anticancer Drug Pairs with Enhanced Therapeutic Activity. Cancer Research, 77, 3564–3576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iorio F, Knijnenburg TA, Vis DJ, Bignell GR, Menden MP, … Garnett MJ. (2016). A Landscape of Pharmacogenomic Interactions in Cancer. Cell, 166, 740–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandoth C, McLellan MD, Vandin F, Ye K, Niu B, … Ding L. (2013). Mutational landscape and significance across 12 major cancer types. Nature, 502, 333–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M, Sato Y, & Morishima K. (2017). KEGG: new perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Research, 45, D353–D361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan T, Moy B, Mroz EA, Ross K, Niemierko A, … Bardia A. (2015). Comparison of the Genomic Landscape Between Primary Breast Cancer in African American Versus White Women and the Association of Racial Differences With Tumor Recurrence. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 33, 3621–3627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberzon A, Birger C, Thorvaldsdóttir H, Ghandi M, Mesirov JP, & Tamayo P. (2015). The Molecular Signatures Database Hallmark Gene Set Collection. Cell Systems, 1, 417–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milacic M, Haw R, Rothfels K, Wu G, Croft D, … Stein L. (2012). Annotating Cancer Variants and Anti-Cancer Therapeutics in Reactome. Cancers, 4, 1180–1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mpindi JP, Yadav B, Östling P, Gautam P, Malani D, … Aittokallio T. (2016). Consistency in drug response profiling. Nature, 540, E5–E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz DM, Cassiani PJ, Li L, Billy E, Korn JM, … Schlabach MR. (2016). CRISPR Screens Provide a Comprehensive Assessment of Cancer Vulnerabilities but Generate False-Positive Hits for Highly Amplified Genomic Regions. Cancer Discovery, 6, 900–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paull KD, Shoemaker RH, Hodes L, Monks A, Scudiero DA, … Boyd MR. (1989). Display and analysis of patterns of differential activity of drugs against human tumor cell lines: development of mean graph and COMPARE algorithm. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 81, 1088–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polley E, Kunkel M, Evans D, Silvers T, Delosh R, … Teicher BA. (2016). Small Cell Lung Cancer Screen of Oncology Drugs, Investigational Agents, and Gene and microRNA Expression. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 108, djw122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]