Abstract

Background: The effect of corticosteroids on tendon properties is poorly understood, and current data are contradictory and diverse. The biomechanical effect of steroids on rotator cuff tendon has not been studied, to our knowledge. The current study was undertaken to characterize the biomechanical effects of corticosteroid exposure on both uninjured and injured rat rotator cuff tendon.

Methods: One hundred and twenty-three male Sprague-Dawley rats were randomly assigned to four groups: control (C), tendon injury (I), steroid exposure (S), and tendon injury plus steroid exposure (I+S). Unilateral tendon injuries consisting of a full-thickness defect across 50% of the total width of the infraspinatus tendon were created. Steroid treatment consisted of a single dose of methylprednisolone placed into the subacromial space. At one, three, and five weeks postoperatively, the shoulders were harvested and the infraspinatus tendon was subjected to biomechanical testing. Two specimens from each group were used for histological analysis.

Results: At one week, maximum load, maximum stress, and stiffness were all significantly decreased in Group S compared with the values in Group C. Mean maximum load decreased from 37.9 N in Group C to 27.5 N in Group S (p < 0.0005). Mean maximum stress decreased from 18.1 MPa in Group C to 13.6 MPa in Group S (p < 0.0005). Mean stiffness decreased from 26.3 N/mm in Group C to 17.8 N/mm in Group S (p < 0.0005). At one week, mean maximum stress in Group I+S (17.0 MPa) was significantly decreased compared with the value in Group I (19.5 MPa) (p < 0.0005). At both the three-week and the five-week time point, there were no significant differences between Group C and Group S or between Group I and Group I+S with regard to mean maximum load, maximum stress, or stiffness. Histological analysis showed fat cells and collagen attenuation in Groups S and I+S. These changes appeared to be transient.

Conclusions: A single dose of corticosteroids significantly weakens both intact and injured rat rotator cuff tendons at one week. This effect is transient as the biomechanical properties of the steroid-exposed groups returned to control levels by three weeks.

Clinical Relevance: Our findings in this rat model suggest that a single corticosteroid dose has significant short-term effects on the biomechanical properties of both injured and uninjured rotator cuff tendon. These effects should be weighed against any potential benefit prior to administering a subacromial corticosteroid injection.

Rotator cuff disease represents a spectrum of pathological conditions, ranging from tendinosis to full-thickness tears. Conservative measures, including rest, physical therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, and subacromial corticosteroid injections, are the mainstay of treatment1-4. Published reports on the effectiveness of subacromial corticosteroids for the treatment of cuff tendinosis have been equivocal. While some clinical studies have demonstrated relief of shoulder pain and improvement of shoulder function following treatment5-8, other studies have not shown a clinical benefit of steroids compared with the injection of Xylocaine (lidocaine)9 or physical therapy alone10.

The beneficial effects of corticosteroids have to be balanced against their potential detrimental effects on the tendon. There are numerous reports of tendon rupture following local steroid injections11-17. The effects of corticosteroids on the biomechanical properties of tendon remain poorly understood. A number of animal studies of the effects of steroid exposure on tendons and ligaments have shown histological and biomechanical changes18-24. In other studies, however, steroid treatment was found to have no adverse effect on tendon and ligament properties25-28. The lack of consensus in the literature, along with the potential side effects, has led to cautious use of subacromial corticosteroid injections in the clinical setting2,3,5,7.

The rotator cuff is located between the coracoacromial arch and the subacromial bursa superiorly and the glenohumeral joint inferiorly. Because of this unique anatomy, it is difficult to extrapolate conclusions from other tendon studies. Anatomic studies of the rat shoulder have demonstrated close similarities to the human shoulder29,30, and the rat shoulder has served as a consistent in vivo model for studying human rotator cuff disease22,23,31-33.

We are not aware of any previous studies of the biomechanical effect of corticosteroids on healthy or injured rotator cuff tendon. A previous investigation performed in our laboratory demonstrated short-term changes in the normal ratio of type-III to type-I collagen expression in the rat infraspinatus tendon after a single subacromial exposure to corticosteroids34. It is unknown, however, if these molecular changes translate into alterations in the collagen composition and ultimately the biomechanical properties of the tendon. The current study was undertaken to characterize the biomechanical effects of corticosteroid exposure on rat rotator cuff tendon.

Materials and Methods

Rat Surgical Model

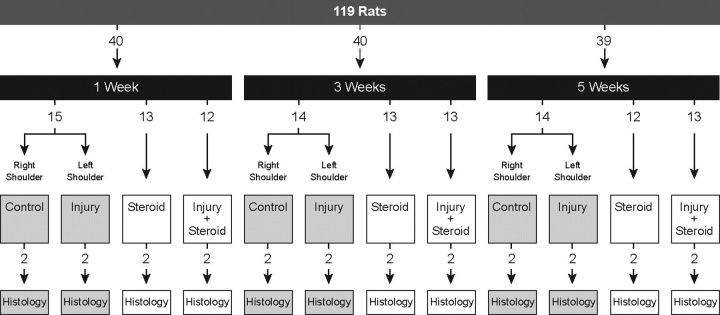

One hundred and twenty-three Sprague-Dawley male rats, with a mean body weight of 378 g (range, 330 to 418 g), were used in this study, which was approved by the institutional animal care and use committee. An infection developed at the surgical site of four rats, leaving 119 rats for inclusion in the study. The rats were randomly assigned to one of three groups: steroid exposure (Group S), tendon injury (Group I), and tendon injury plus steroid exposure (Group I+S). The control group (Group C) and Group I were composed of the same rats, with the left shoulder serving as the tendon-injury specimen and the contralateral shoulder serving as the untreated control. The left shoulder was used in the other groups (Fig. 1). Four rats served as sham-surgery controls to determine whether the surgical procedure itself had any effect on the biomechanics of the rotator cuff tendon. We chose the infraspinatus tendon to study the effects of subacromial steroid exposure. The fact that the rat infraspinatus tendon has an anatomic relationship similar to that of human infraspinatus tendon and that it has a greater working length than the supraspinatus tendon made it an ideal model for our study35.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram depicting how the rats were divided into the four groups and for evaluation at three time points. Two rats from each group were used for histological analysis.

Surgical Procedure

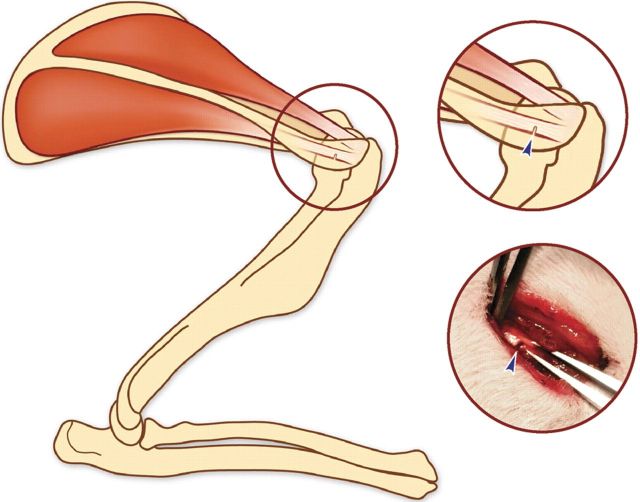

A subcutaneous injection of antibiotics (gentamicin; 8 mg/kg) was administered preoperatively. Anesthesia was induced by means of intraperitoneal injections of ketamine (90 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). The shoulder to be operated on was shaved. The sterile surgical procedure was performed under loupe magnification as previously described34. A 1-cm incision was made over the lateral border of the acromion. A small portion of the deltoid muscle was divided to expose the underlying acromion and the infraspinatus tendon. A laceration (a simulated injury), 2 mm from the humeral insertion, was standardized with intraoperative calipers. The calipers were then used to measure the tendon width, which was approximately 2 mm in all specimens. The calipers were set for 1 mm, and a full-thickness defect across 50% of the tendon width was created 2 mm medial to the humeral insertion with a microknife (Fig. 2). In the rats in Group I (tendon injury), the wound was then closed, without steroid exposure, by suturing the fascia of the deltoid muscle with Prolene (polypropylene) and stapling the skin. No activity restrictions were imposed postoperatively.

Fig. 2.

Schematic diagram and intraoperative photograph depicting the injury created in the infraspinatus tendon (arrowheads).

In Groups S and I+S (steroid exposure), a single dose of methylprednisolone acetate (0.6 mg/kg, equivalent to a human dose) was injected with a micropipette into the subacromial space under direct visualization. In Group I+S (injury plus steroid), the steroid exposure directly followed creation of the tendon injury. The deltoid was closed over the subacromial space to ensure no leakage of the steroid. The sham-surgery group underwent the identical surgical exposure of the infraspinatus tendon with subacromial exposure to saline solution.

The rats were killed at one, three, or five weeks postoperatively. We chose to test the tendons at these time intervals to determine if our previous finding of an alteration in the ratio of type-III to type-I collagen34 corresponds to a biomechanical change in the tendon. The entire scapula with its overlying muscles and the humerus was dissected free from the body, and the limb was disarticulated at the elbow joint. In Group I, the contralateral shoulder was also harvested to serve as the control (Group C). The shoulders were stored at −20°C in saline solution-soaked gauze.

Biomechanical Testing

The specimens were allowed to thaw, and each shoulder was dissected to isolate the infraspinatus tendon-humerus unit. The tendinous portion of the infraspinatus was then isolated. The humerus up to the infraspinatus insertion was embedded in polymethylmethacrylate within a 3-mL syringe. The entire tendon was protected by saline solution-soaked gauze at room temperature to prevent thermal necrosis during the exothermic cement-curing process. The syringe was then placed into a custom metal block, which allowed the infraspinatus tendon to hang vertically at a 90° angle to the long axis of the humerus. This ensured testing along the direction of the tendon fibers. The infraspinatus tendon was clamped between pieces of sandpaper in a soft-tissue clamp, and a materials testing machine (model 8841; Instron, Norwood, Massachusetts) was used.

The biomechanical testing protocol that we utilized was similar to that described by Galatz et al.36. Specimens were subjected to a preload of 0.2 N and held for sixty seconds to allow measurement of the tendon thickness and width at the injury site or at the corresponding location in the uninjured tendons. Measurements were made under loupe magnification with digital calipers. The cross-sectional area was calculated with the assumption of a rectangular geometry19,37. Tendons were then preconditioned for five cycles to 0.38 mm of displacement at a rate of 0.1 mm/s, after which they were tested to failure at a rate of 0.1 mm/s. Maximum load versus extension was recorded for each specimen. Extension measurements were determined with use of machine displacement. Maximum stress was calculated by dividing the maximum load by the area measurement. Stiffness was determined by finding the slope of the load versus extension curve in the linear region following toe-in.

Histological Analysis

Two rats from each group were used for histological analysis. The tendons were fixed in a buffered 10% formalin solution for two days, after which they were placed flat and embedded in paraffin. They were then sectioned along the longitudinal direction of the infraspinatus fibers to include the entire length of the tendon. Five sections were cut at a thickness of 4 μm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. An independent pathologist with experience in musculoskeletal pathology examined the sections to assess the cellular response to injury and/or steroids, inflammatory cells, and collagen orientation.

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcomes included maximum load, maximum stress, and stiffness in each group at each time point. For each outcome parameter, the groups were compared at each time point with use of multivariate analysis of variance and Tukey multiple comparison procedures. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

Source of Funding

This study was funded by an institutional grant through the Walgreen Foundation. This foundation funds research through the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery but did not have any direct role in this investigation.

Results

General Observations

Postoperatively, all rats exhibited normal gait patterns and food intake. No differences in weight were seen among the treatment groups at any time point. There were no differences in maximum load, maximum stress, or stiffness between the sham-surgery group and the control group at one week. There were no significant differences in tendon cross-sectional area among the groups at any time point (Table I).

TABLE I.

Biomechanical Results

| Group | No. | Area* (mm2) | Maximum Load† (N) | Maximum Stress† (MPa) | Stiffness† (N/mm) |

| 1 week | |||||

| Control | 11 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 37.9 (34.6-41.1) | 18.1 (17.5-18.6) | 26.3 (24.2-28.4) |

| Steroid | 11 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 27.5 (23.9-31.1) | 13.6 (12.8-14.4) | 17.8 (15.4-20.2) |

| Injury | 11 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 30.9 (28.4-33.5) | 19.5 (18.4-20.6) | 18.2 (16.5-19.8) |

| Injury + steroid | 10 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 27.6 (24.3-31.0) | 17.0 (16.1-17.9) | 18.7 (16.1-21.4) |

| 3 weeks | |||||

| Control | 10 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 38.4 (35.5-41.4) | 18.1 (17.5-18.8) | 25.7 (22.6-28.7) |

| Steroid | 11 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 38.1 (36.0-40.2) | 18.1 (17.8-18.4) | 23.0 (21.7-24.4) |

| Injury | 10 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 34.0 (30.7-37.2) | 20.3 (19.3-21.3) | 19.7 (18.1-21.2) |

| Injury + steroid | 11 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 35.3 (31.2-39.3) | 20.7 (19.3-22.1) | 21.2 (19.4-23.0) |

| 5 weeks | |||||

| Control | 10 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 43.9 (40.3-47.5) | 18.7 (17.8-19.7) | 28.6 (25.4-31.8) |

| Steroid | 10 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 41.2 (37.9-44.5) | 18.2 (17.6-18.9) | 27.3 (23.0-31.6) |

| Injury | 9 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 37.3 (32.7-41.8) | 20.4 (19.0-21.8) | 23.1 (20.1-26.1) |

| Injury + steroid | 11 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 37.1 (33.7-40.1) | 20.6 (19.4-21.8) | 20.9 (19.0-22.8) |

The values are given as the mean and standard deviation.

The values are given as the mean with the 95% confidence interval in parentheses.

The mode of failure in the control group differed from that in the other groups. The tendons in the control group failed at two places, at the tendon insertion onto the humeral head and within the tendon substance between the two grips. The tendons in the steroid group(s) failed within the tendon substance. The tendons in the injury (I) and injury-plus-steroid (I+S) groups all failed at the site of injury.

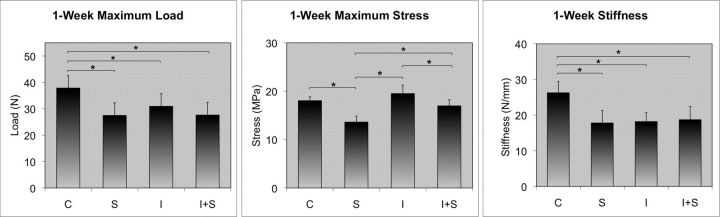

One-Week Time Point

Steroid exposure had a significant effect on tendon biomechanics at one week (Fig. 3). Mean maximum load decreased from 37.9 N in Group C to 27.5 N in Group S, a decrease of 27% (p < 0.0005). There was no significant difference in mean maximum load between Group I and Group I+S (30.9 N and 27.6 N, respectively).

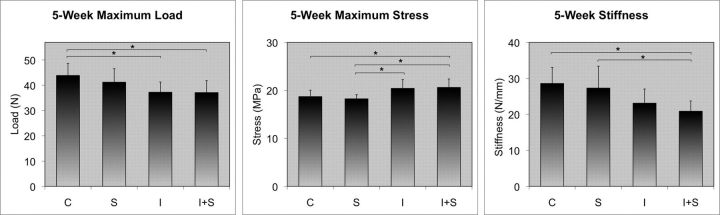

Fig. 3.

One-week results. Steroid exposure reduced the maximum load, maximum stress, and stiffness of normal tendon and reduced the maximum stress of injured tendon. Asterisks indicate significance (p < 0.01).

Mean maximum stress decreased from 18.1 MPa in Group C to 13.6 MPa in Group S, a decrease of 25% (p < 0.0005). Mean maximum stress decreased from 19.5 MPa in Group I to 17.0 MPa in Group I+S, a decrease of 13% (p < 0.0005).

Mean stiffness decreased from 26.3 N/mm in Group C to 17.8 N/mm in Group S, a decrease of 32% (p < 0.0005). There was no significant difference in stiffness between Group I and Group I+S (18.2 N/mm and 18.7 N/mm, respectively).

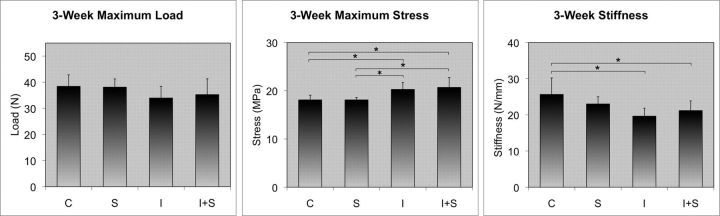

Three-Week Time Point

Maximum load in the test groups returned to control levels at three weeks (Fig. 4). Mean maximum load measured 38.4 N in Group C compared with 38.1 N in Group S, whereas it measured 34.0 N in Group I compared with 35.3 N in Group I+S. Neither of these comparisons revealed a significant difference.

Fig. 4.

Three-week results. Exposure to steroids resulted in no difference in maximum load, maximum stress, or stiffness in either the normal tendons or the injured tendons. The injured tendons showed increased maximum stress and decreased stiffness compared with the controls. Asterisks indicate significance (p < 0.01).

Mean maximum stress returned to control levels at three weeks as well. Mean maximum stress was determined to be 18.1 MPa in both Group C and Group S. It was found to be 20.3 MPa in Group I compared with 20.7 MPa in Group I+S. Neither of these comparisons showed a significant difference.

Mean stiffness was determined to be 25.7 N/mm in Group C compared with 23.0 N/mm in Group S. The value was 19.7 N/mm in Group I compared with 21.2 N/mm in Group I+S. No significant difference was found in either comparison.

Five-Week Time Point

The results at five weeks reflected those seen at three weeks (Fig. 5). Mean maximum load measured 43.9 N in Group C, while it measured 41.2 N in Group S. Mean maximum load was 37.3 N in Group I, while it was 37.1 N in Group I+S. Neither of these comparisons showed a significant difference.

Fig. 5.

Five-week results. Exposure to steroids resulted in no difference in maximum load, maximum stress, or stiffness in either the normal tendons or the injured tendons. Asterisks indicate significance (p < 0.05).

Mean maximum stress was determined to be 18.7 MPa in Group C compared with 18.2 MPa in Group S. It was 20.4 MPa in Group I compared with 20.6 MPa in Group I+S. No significant difference was found in either comparison.

Mean stiffness measured 28.6 N/mm in Group C compared with 27.3 N/mm in Group S. The value was 23.1 N/mm in Group I compared with 20.9 N/mm in Group I+S. Neither of these comparisons demonstrated a significant difference.

Histological Findings

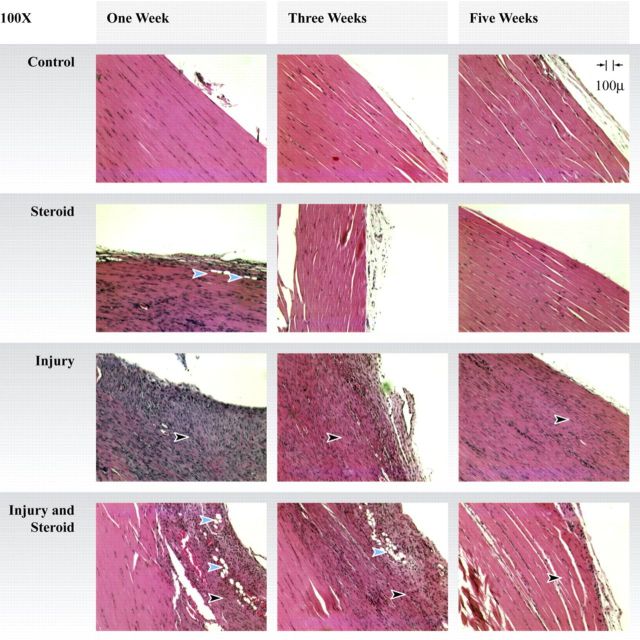

Histologically, Group C displayed normal collagenous fibers arranged in compact parallel bundles at all time points (Fig. 6). At one week, Group S demonstrated increased cellularity with abundant lymphocytes. In addition, the collagen was subjectively judged to be attenuated with less parallelism than in Group C. There were also fat cells located near the edge of the tendon that were not present in Group C or Group I. At one week, Group I demonstrated a cellular granulation tissue reaction consisting of histiocytes and lymphocytes. Group I+S showed granulation tissue with proliferative blood vessels, histiocytes, and lymphocytes. There were abundant fat cells in the area of the tendon injury.

Fig. 6.

Histological findings at the site of the tendon injury or the corresponding area in the uninjured tendons (black arrowheads). Steroid-exposed tendons have fat cells (blue arrowheads) present at early time points. All groups showed progression toward normal parallel collagen orientation over time (hematoxylin and eosin, ×100).

At three weeks, Group S assumed a histological pattern similar to that of Group C, with dense collagenous fibers arranged in parallel bundles. Group I showed collagen tissue remodeling into a more parallel architecture. Group I+S continued to show fat cells. The remodeling collagen tissue had assumed a more parallel orientation.

At five weeks, Group S and Group I+S had assumed a collagen tissue architecture similar to that in Group C. Group I continued to show increased cellularity; however, the collagen fibers showed greater parallel orientation compared with what had been seen at one and three weeks.

Discussion

Our results proved our hypothesis that one dose of corticosteroids significantly alters the biomechanical properties of both uninjured and injured rat rotator cuff tendons. This effect appears to be transient, as the biomechanical parameters returned to control levels by three weeks.

Normal Tendon

We found a significant reduction in the strength of normal rat rotator cuff tendon one week after exposure to corticosteroids. Maximum load decreased by 27%; maximum stress, by 25%; and stiffness, by 32%. These findings are consistent with those in a study by Hugate et al.18, who showed a 13% decrease in maximum load and a 23% decrease in maximum stress in normal rabbit Achilles tendons exposed to corticosteroids. In another study of rabbit Achilles tendons, Phelps et al.26 found no difference in maximum load or stiffness between specimens treated with serial corticosteroid injections and those treated with saline solution. However, the tendons in that study were tested at an average of thirty-three days (nearly five weeks) after the last injection. These studies support our conclusion that corticosteroids have a substantial but transient detrimental effect on the biomechanical properties of normal tendon.

Injured Tendon

Following steroid exposure, injured tendon displayed less dramatic decreases in biomechanical measurements than did normal tendon. Mean maximum load decreased from 30.9 N in the injury group (Group I) to 27.6 N in the injury-plus-steroid group (Group I+S); this difference was not significant. However, calculation of maximum stress showed the tendons in Group I+S to be 13% weaker than those in Group I, and this difference was significant (p < 0.005). Our theory is that steroid exposure not only decreases the strength of the intact portion of a tendon but also alters the biomechanics of local granulation tissue. Thus, the area is slightly increased by the granulation tissue, but this tissue has poor biomechanical strength, leading to an overall decrease in stress.

We are aware of three previous studies in which the effects of steroids on injured tendons were assessed. Kapetanos20 found a decrease in failure load of 29.8% and a decrease in energy to failure of 67.1% in injured rabbit Achilles tendons five days after exposure to triamcinolone. Similarly, Wrenn et al.38 found that repaired dog Achilles tendons treated with daily triamcinolone injections were 40% weaker than repaired tendons not exposed to steroids. These results suggest that a single dose of corticosteroids has a considerable effect on the biomechanics of an injured tendon. On the other hand, McWhorter et al.25 found no difference in failure load in injured rat Achilles tendons exposed to hydrocortisone. However, in that study, the earliest test period was three weeks after injection. These data support our findings at three weeks. It is possible that, if McWhorter et al. had performed their assessments at an earlier time period, they would have found a decrease in strength in the tendons exposed to corticosteroids just as we did in our study.

Comparison of the Effects of Steroids and Injury

We have shown that both steroid exposure and injury are detrimental to the tendon. At one week, the steroid and injury groups displayed similar maximum loads (27.5 and 27.6 N, respectively) and similar stiffness values (17.8 and 18.7 N/mm, respectively). It is plausible that steroid exposure and tendon injury activate similar cellular responses. In a previous study in our laboratory, collagen gene expression was measured after steroid exposure and/or tendon injury34. That study showed that the magnitudes of the increase in the ratio of type-III to type-I collagen were comparable in the steroid and injury groups at one week. Additionally, the injury and the injury-plus-steroid groups had similar and substantial increases in the ratio of type-III to type-I collagen at one week. The ratios returned to control levels by five weeks34. Thus, the effects of corticosteroids on tendon collagen expression and biomechanical parameters were both transient in these studies.

Although collagen composition plays an important role in the biomechanical properties of tendon, it may not be entirely responsible for the biomechanical effects of the steroid exposure that we observed in this study. Wong et al.39 showed that glucocorticoid exposure suppresses proteoglycan production in cultured human tenocytes. One possible explanation for our data is that steroid exposure activates a response in normal tendon that mimics, at least to some extent, the early biological response to physical tendon injury. It is clear that additional studies are needed to analyze changes in tendon biology following both acute injury and steroid exposure. We are currently analyzing molecular changes in rat rotator cuff tendon following treatment to further elucidate the mechanisms responsible for the responses of rotator cuff tendon to injury and steroids.

Histological Findings

The steroid-exposed groups both showed fat cells that were not seen in the control or injury group. This appears to be a transient phenomenon as the fat cells were no longer present at three weeks in the steroid group and at five weeks in the injury-plus-steroid group. In addition, the steroid group showed inflammatory cells and collagen attenuation. These results are consistent with those of both Tillander et al.22 and Akpinar et al.23, who found inflammatory cells and collagen fragmentation in normal rat rotator cuff tendons injected with corticosteroids. However, in all previous histological studies on steroid-exposed tendons of which we are aware, the authors performed the evaluation at only one time point22-24. Our protocol allowed us to track histological changes over time. As was the case for the biomechanical data, the histological changes in response to steroids and/or injury appeared to be transient, as all groups showed collagen remodeling toward a normal, parallel orientation by three weeks.

Our study had some limitations. First, data obtained from any animal model must be closely scrutinized prior to extrapolation to humans. The rotator cuff in the rat, the model in this study, is associated with a weight-bearing forelimb, which is unlike the situation in humans. Although we did not observe any gait abnormalities, it is plausible that the corticosteroid-related effects that we found may have been modulated by weight-bearing. Kjaer et al. showed that mechanical loading of tendon increases levels of growth factors that potentially stimulate collagen synthesis40. Another limitation of our study is that we used an acute injury model—i.e., a laceration through normal tendon, as opposed to a rotator cuff tear that occurs traumatically, most often through abnormal tendon. Thus, we did not duplicate the clinical setting in which subacromial corticosteroid injections are commonly used. Patients often receive steroid injections for chronic tendinopathy2-4. However, to our knowledge, there are no accepted animal models for reproducing chronic rotator cuff disease. Our emphasis was to help clarify the largely unexamined interplay between rotator cuff disease and corticosteroids rather than to differentiate the type and chronicity of rotator cuff injury. In addition, we studied two distinct groups of rats, one with a tendon injury (Groups I and I+S) and one without a tendon injury (Groups C and S). In the injury groups, there was tendon remodeling in response to the injury. This is a confounding factor in the comparison of the injury groups with the uninjured groups. To avoid this problem, we confined the comparisons to those between Group C and Group S and those between Group I and Group I+S. This emphasized the effect of steroids on the tendons without the confounding variable of tendon injury.

Despite the limitations that we have discussed, our data clearly show a significant impact of corticosteroid exposure on rat rotator cuff tendon biomechanics, which suggests that application of steroids temporarily alters tendon biology.

In conclusion, the data presented in this study suggest that a single dose of corticosteroids significantly weakens the rat rotator cuff infraspinatus tendon. While this effect appears to be transient, the significant changes in biomechanical properties of tendon exposed to corticosteroids suggest that a single dose of this agent is not entirely benign. These risks should be weighed against any potential benefit prior to administering a subacromial corticosteroid injection.

Acknowledgments

Note: The authors thank Dr. Sherri Yong, MD, and Marykay Olson for their time and effort in the histological analysis. They also thank Patrick Carrico for assisting with the figures in our study.

Footnotes

Disclosure: In support of their research for or preparation of this work, one or more of the authors received, in any one year, outside funding or grants of less than $10,000 from the Walgreen Foundation. Neither they nor a member of their immediate families received payments or other benefits or a commitment or agreement to provide such benefits from a commercial entity. No commercial entity paid or directed, or agreed to pay or direct, any benefits to any research fund, foundation, division, center, clinical practice, or other charitable or nonprofit organization with which the authors, or a member of their immediate families, are affiliated or associated.

Investigation performed at the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery and Rehabilitation, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Illinois

References

- 1.Bartolozzi A, Andreychik D, Ahmad S. Determinants of outcome in the treatment of rotator cuff disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;308:90-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breazeale NM, Craig EV. Partial-thickness rotator cuff tears. Pathogenesis and treatment. Orthop Clin North Am. 1997;28:145-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fukada H. Partial-thickness rotator cuff tears. A modern view on Codman's classic. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9:163-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McConville OR, Iannotti JP. Partial-thickness tears of the rotator cuff: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1999;7:32-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arroll B, Goodyear-Smith F. Corticosteroid injections for painful shoulder: a meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55:224-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adebajo AO, Nash P, Hazleman BL. A prospective double blind dummy placebo controlled study comparing triamcinolone hexacetonide injection with oral diclofenac 50 mg TDS in patients with rotator cuff tendinitis. J Rheumatol. 1990;17:1207-10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blair B, Rokito AS, Cuomo F, Jarolem K, Zuckerman J. Efficacy of injections of corticosteroids for subacromial impingement syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:1685-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petri M, Dobrow R, Neiman R, Whiting-O'Keefe Q, Seaman WE. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the treatment of the painful shoulder. Arthritis Rheum. 1987;30:1040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alvarez C, Litchfield R, Jackowski D, Griffin S, Kirkley A. A prospective, double-blind, randomized clinical trial comparing subacromial injection of betamethasone and xylocaine to xylocaine alone in chronic rotator cuff tendinosis. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:255-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hay EM, Thomas E, Paterson SM, Dziedzic K, Croft PR. A pragmatic randomised controlled trial of local corticosteroid injection and physiotherapy for the treatment of new episodes of unilateral shoulder pain in primary care. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:394-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kleinman M, Gross AE. Achilles tendon rupture following steroid injection. Report of three cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983;65:1345-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vardakas DG, Musgrave DS, Varitimidis SE, Goebel F, Sotereanos DG. Partial rupture of the distal biceps tendon. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10:377-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stannard JP, Bucknell AL. Rupture of the triceps tendon associated with steroid injections. Am J Sports Med. 1993;21:482-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cowan MA, Alexander S. Simultaneous bilateral rupture of Achilles tendons due to triamcinolone. BMJ. 1961;1:1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee HB. Avulsion and rupture of the tendo calcaneous after injection of hydrocortisone. BMJ. 1957;2:395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee MLH. Bilateral rupture of Achilles tendon. BMJ. 1961;1:1829-30. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Melmed EP. Spontaneous bilateral rupture of the calcaneal tendon during steroid therapy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1965;47:104-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hugate R, Pennypacker J, Saunders M, Juliano P. The effects of intratendinous and retrocalcaneal intrabursal injections of corticosteroid on the biomechanical properties of rabbit Achilles tendons. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:794-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiggins ME, Fadale PD, Barrach H, Ehrlich MG, Walsh WR. Healing characteristics of a type I collagenous structure treated with corticosteroids. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22:279-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kapetanos G. The effect of the local corticosteroids on the healing and biomechanical properties of the partially injured tendon. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;163:170-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oxlund H. The influence of a local injection of cortisol on the mechanical properties of tendons and ligaments and the indirect effect on skin. Acta Orthop Scand. 1980;51:231-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tillander B, Franzen LE, Karlsson MH, Norlin R. Effect of steroid injections on the rotator cuff: an experimental study in rats. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999;8:271-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akpinar S, Hersekli MA, Demirors H, Tandogan RN, Kayaselcuk F. Effects of methylprednisolone and betamethasone injections of the rotator cuff: an experimental study in rats. Adv Ther. 2002;19:194-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tatari H, Kosay C, Baran O, Ozcan O, Ozer E. Deleterious effects of local corticosteroid injections on the Achilles tendon of rats. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2001;121:333-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McWhorter JW, Francis RS, Heckmann RA. Influence of local steroid injections on traumatized tendon properties. A biomechanical and histological study. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19:435-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phelps D, Sonstegard DA, Matthews LS. Corticosteroid injection effects on the biomechanical properties of rabbit patellar tendons. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1974;100:345-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campbell RB, Cannistra LM, Fadale PD, Wiggins M, Akelman E. The effects of local corticosteroid injection on the healing of rat medial collateral ligaments. Trans Orthop Res Soc. 1991;16:112. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mackie JW, Goldin B, Foss ML, Cockrell JL. Mechanical properties of rabbit tendons after repeated anti-inflammatory steroid injections. Med Sci Sports. 1974;6:198-202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soslowsky LJ, Carpenter JE, DeBano CM, Banerji I, Moalli MR. Development and use of an animal model for investigations on rotator cuff disease. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1996;5:383-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Norlin R, Hoe-Hansen C, Oquist G, Hildebrand C. Shoulder region of the rat: anatomy and fiber composition of some suprascapular nerve branches. Anat Rec. 1994;239:332-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soslowsky LJ, Thomopoulos S, Tun S, Flanagan CL, Keefer CC, Mastaw J, Carpenter JE. Overuse activity injures the supraspinatus tendon in an animal model: a histologic and biomechanical study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9:79-84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carpenter JE, Thomopoulos S, Flanagan CL, DeBano CM, Soslowsky LJ. Rotator cuff defect healing: a biomechanical and histologic analysis in an animal model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7:599-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carpenter JE, Flanagan CL, Thomopoulos S, Yian EH, Soslowsky LJ. The effects of overuse combined with intrinsic or extrinsic alterations in an animal model of rotator cuff tendinosis. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:801-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wei AS, Callaci JJ, Juknelis D, Marra G, Tonino P, Freedman KB, Wezeman FH. The effect of corticosteroid on collagen expression in injured rotator cuff tendon. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1331-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schneeberger AG, Nyffeler RW, Gerber C. Structural changes of the rotator cuff caused by experimental subacromial impingement in the rat. J Shoulder Elbow Surg Am. 1998;7:375-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Galatz LM, Silva MJ, Rothermich SY, Zaegel MA, Havlioglu N, Thomopoulos S. Nicotine delays tendon-to-bone healing in a rat shoulder model. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:2027-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Woo SL-Y, Peterson RH, Ohland KJ, Sites TJ, Danto MI. The effects of strain rate on the properties of the medial collateral ligament in skeletally immature and mature rabbits: a biomechanical and histological study. J Orthop Res. 1990;8:712-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wrenn RN, Goldner JL, Markee JL. An experimental study of the effect of cortisone on the healing process and tensile strength of tendons. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1954;36:588-601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wong MW, Tang YY, Lee SK, Fu BS. Glucocorticoids suppress proteoglycan production by human tenocytes. Acta Orthop. 2005;76:927-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kjaer M, Langberg H, Miller BF, Boushel R, Crameri R, Koskinen S, Heinemeier K, Olesen JL, Døssing S, Hansen M, Pedersen SG, Rennie MJ, Magnusson P. Metabolic activity and collagen turnover in human tendon in response to physical activity. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2005;5:41-52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]