Abstract

Purpose:

To examine an image remapping method for peripheral visual field (VF) expansion with novel virtual reality Digital Spectacles (DSpecs) to improve visual awareness in glaucoma patients.

Design:

Prospective Case Series.

Methods:

Monocular peripheral VF defects were measured and defined with a head mounted display diagnostic algorithm. We used the monocular VF to calculate remapping parameters with a customized algorithm to relocate and resize unseen peripheral targets within the remaining VF. We tested the sequence of monocular VF testing and customized image remapping in 23 patients with typical glaucomatous defects. Test images demonstrating roads and cars were used to determine increased awareness of peripheral hazards while wearing the DSpecs. Patients scores in identifying and counting peripheral objects with the remapped images were the main outcome measures.

Results:

The diagnostic monocular VF testing algorithm was comparable to standard automated perimetric determination of threshold sensitivity based on point by point assessment. Eighteen of 23 patients (78%) could identify safety hazards with the DSpecs that they could not previously. The ability to identify peripheral objects improved with the use of the DSpecs (P value = 0.024, Chi square test). Quantification of the number of peripheral objects improved with the DSpecs (P = 0.0026, Wilcoxon rank sum test).

Conclusions:

These novel spectacles may enhance peripheral objects awareness by enlarging the functional field of view in glaucoma patients.

Keywords: Digital Spectacles, Visual Field, Peripheral Visual Defects, Field Expansion

INTRODUCTION

Peripheral visual field (VF) defects are caused by many diseases, including glaucoma, retinitis pigmentosa, and strokes. Over 60 million patients suffer irreversible visual losses secondary to glaucoma.1 Patients with peripheral VF losses account for about 25% of those suffering from VF losses.2 Despite recent advances, no medical or surgical treatment can reverse existing damage.3–5 Patients sustain significant loss of their functional vision leading to a disability that dramatically affects many daily life activities and higher order visual processing skills.2, 6–8 Patients seek low vision rehabilitation (LVR)3, and depend on visual aids to maximize their visual performance and improve their functionality and safety.9, 10 Nevertheless, current visual aids often fail to achieve the goals of safety and independence.11, 12 Additionally, the evaluation of the effectiveness of modern visual aids for patients with defective peripheral field is limited.12, 13

Current strategies to improve visual function offer patients either optical or electronic visual aids. Optical devices either minify or relocate the remaining VF associated with peripheral defects, and in doing so, reduce the perceived resolution and frequently produce annoying image overlaps.14, 15 Electronic visual aids capture the environment with an electronic camera, process acquired signal, and display the processed images to the patient. Currently available electronic low visual aids, primarily address central vision deficits, and do not consider functional activities that depend on the peripheral vision. Some approaches apply electronic magnification of images and letters, through head mounted display (HMD) or closed-circuit TV (CCTV) to help patients with age related macular degeneration (AMD).16–18 Other devices used basic image enhancements techniques such as contrast and brightness enhancement, zoom, edge sharpening adjustments and color inversion, which makes text on white paper easier to read.12, 17, 19–21 However, the clinical trials and studies performed with these visual aids are limited and only two studies reported their performances.16, 22 Culham and coworkers applied central vision tests such as reading, writing, and identifying objects, to determine the utility of the currently available visual aids.16 Wittich and associates investigated a device that improved central vision related tests; however, the tasks depending on the peripheral vision did not significantly improve with this aid.22 No guidelines nor criteria for determining the suitability of a particular visual aid to a specific patient’s condition have been developed. This is crucially important when recommending visual aids to patients with peripheral visual defects.11 We believe that a need exists to develop a low vision aid that overcomes the shortcomings reported in previous studies, particularly with respect to improving peripheral vision.23

We introduce, herein, a novel concept in visual aids in which we use digital spectacles (DSpecs) that measure the VF and use that to apply a personalized vision augmentation profile based on patient’s unique VF defects. Augmentation of the VF is done by real time resizing and shifting of patients’ scene to the remaining intact VF. To assess the value of DSpecs and as a proof of concept, we tested the ability of patients to recognize hazardous objects located in the peripheral VF with and without the DSpecs using static test images.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

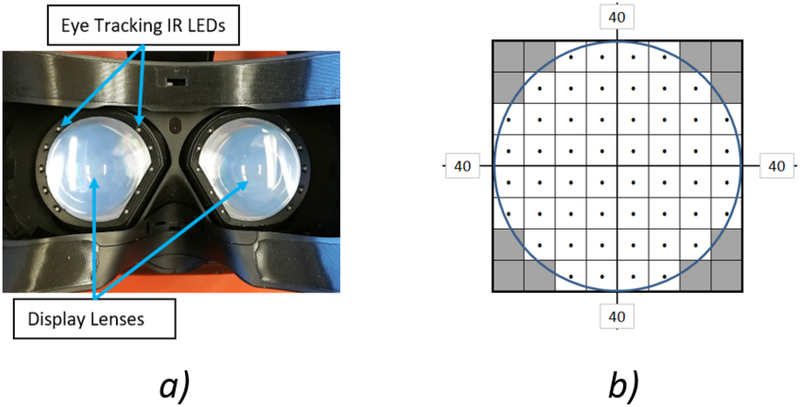

We used a virtual reality head mounted display (VR HMD) (HTC Vive, Xindian District, New Taipei City, Taiwan) with an integrated eye tracking system (Tobii Technology, Danderyd, Sweden), to transmit gaze data for visual field testing. Infrared light emitting diodes (LEDs) positioned around the display lenses and eye tracking sensors located beneath each display lens enabled independent tracking of the right and left eyes (Figure 1.A). Field of view of the display of the VR HMD and the eye tracking system are 100 degrees for each eye independently. The headset was tethered to a VR enabled laptop (Intel Core i7, 2.8GHz Quad core, NVIDIA 1070, 32GB RAM) that runs the VF testing program and image remapping algorithms. These algorithms were implemented with MATLAB R2018b (MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA) and C# under Unity (Unity Technologies, San Francisco, California, USA).

Figure 1:

a) Eye tracking infrared light emitting diodes integrated with the display lens shown from the patient view. The eye tracking sensor is located beneath the display lens. b) Visual field testing point stimuli layout.

Before visual field testing, the eye tracker was calibrated with a one-point strategy. This calibration process offsets the origin of the eye tracking coordinate system to the central fixation point on the display screen. The VF test with 80 degrees was performed, and unseen or partially seen test targets were displayed to the participants in areas of intact VF. The participants were asked to identify hazardous objects such as cars, with and without image remapping. Patient with prescription glasses wore their glasses during the test that fit inside the HMD device.

PARTICIPANTS RECRUITMENT:

A prospective institutional review board (IRB) approval was given from the University of Miami, and informed consents were obtained from all participating patients before commencing the study. The study design was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and compliant with HIPAA regulations.

We examined 28 patients recruited from glaucoma clinics at the Anne Bates Leach Eye Center, Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine during their regular follow-up visits. Five patients were excluded from the study. Reasons for exclusion were unreliable VF testing results (n = 3), and inability to perform eye tracking due to pupil dilation (n=2). Twenty-three patients (33 eyes) were included in the study. All these patients had previously performed standard automated perimetry (SAP) with the Humphrey Zeiss 24–2 program that demonstrated typical glaucomatous visual field defects. Twenty-one patients were examined with the SITA-Standard strategy. The other two patients were tested with the SITA-Fast (n=1), and FAST PAC (n=1) strategies.

MEASURING THE VISUAL FIELD:

The DSpecs measurement method of the visual field was based on the Humphrey standard automated static perimetry technique.24 Fast thresholding strategy was applied with four contrast staircase stimuli. The stimuli locations within the central 40 degrees’ radius were tested with 52 stimuli sequences at the locations shown in (Figure 1.B). The spacing between each stimulus location was 10 degrees. Each stimuli sequence consisted of four consecutive stimuli that were presented at different contrast levels with respect to the background ranging from 32 dB down to 20 dB in steps of 4 dB, and the value of 0 dB was assigned if the patient did not see any stimulus contrast. The background had a bright illumination (100 lux) and the stimuli were dark dots with different contrasts. A stimulus size of 0.43 degrees was used, which is equivalent to the standard Goldmann stimulus size III. The stimulus size at the mid periphery (between 24 and 40 degrees radius) was doubled to be 0.86 degrees, to compensate for the display degraded lens performance in the periphery, and also in consideration of the decreased acuity of the normal human’s peripheral vision that drops to 20/270 at 25 degrees and even worse acuity of 20/555 at 40 degrees eccentricity.25 The testing program was performed with either a stimulus size III (0.43 degrees) or size V (1.72 degrees), according to the SAP testing parameters previously performed.

Patients were asked to fix their eye under examination at a fixation target located at the center of the display. Patient fixation was monitored using the eye tracking system at different time intervals. The testing program proceeded if the participant could fix on the central target. If fixation was not maintained, the program would be paused until fixation was restored. Patient responded to the stimuli by pressing a wireless clicker. Additionally, gaze directions were checked after receiving a response; whether positive (seen point) or negative (unseen point), to ensure proper fixation before recording the response, otherwise that particular stimulus location was repeated later during the test. Normal blind spots were scanned, by showing suprathreshold stimuli at four different locations spaced by 1 degree in the 15-degree vicinity temporal to fixation. This step minimized rotational misalignments between the headset and the eyes. False positive responses, false negative responses and fixation losses were calculated. To generate a VF display plot we interpolated the 52 responses to generate a gray scale printout.

VF tests made with the DSpecs for the 23 clinical patients were compared with the most recent Humphrey VF SAP test. The common areas of the central 24 degrees were matched and compared between the two VF testing devices. The comparison and relative error calculations were based on a point by point basis at the common central 24 degrees’ area. Considering the SAP test as the reference, our VF test error calculations were calculated by finding the mismatches between the two testing methods. More peripheral visual field areas were judged by absence of isolated response points.

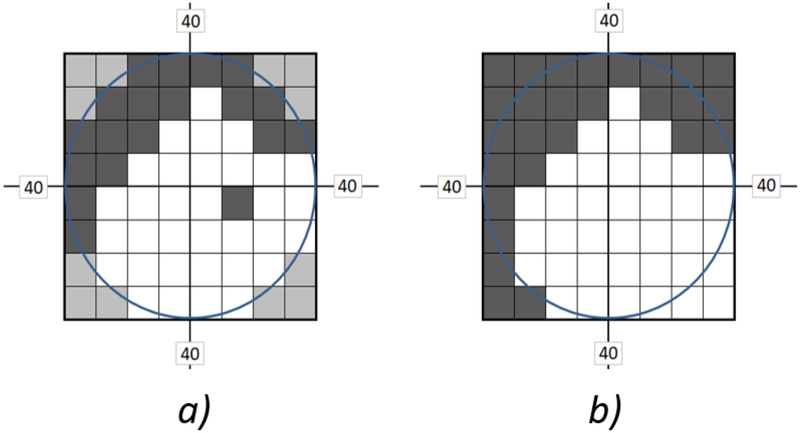

IMAGE REMAPPING:

We remapped images by resizing and shifting geometric operations of the test image to fit into the intact areas of the measured VF. The remapping algorithm was based on the VF test results of the 52-point responses arranged in 8X8 matrices, that were used to calculate new dimensions and a new center for the output images to be shown to the participants. First, the VF was binarized by setting all “seen” responses to ones and “unseen” responses to zeros; this resulted in a binary image of 8X8 size. (Figure 2.A) shows an example of such binary image for a right eye exam with peripheral defects in the upper hemifield. The 12 corner points marked with the gray color are untested points, and were given a value of zero. Afterward, all small regions consisting of no more than 4 connected “unseen” pixels, were removed from the binary visual field image. Those small regions were not considered in the image fitting process (Figure 2.B). The ignored small unseen regions represent either the normal blind spots, insignificant defects (of up to 8% of the total number of testing points), or any subjective random erroneous responses that might have occurred during the patient’s VF test. Our aim of eliminating these small unseen regions from the calculations was to remap the test images as large as possible inside the largest intact VF area and reduce the negative effect of excessive image minification and translation operations that might be produced by the remapping algorithm. With a trial and error approach, elimination of the 4 connected unseen points provided a satisfactory image remapping performance.

Figure 2:

a) Example of a visual field test showing peripheral blind areas. b) The field after eliminating small blind regions.

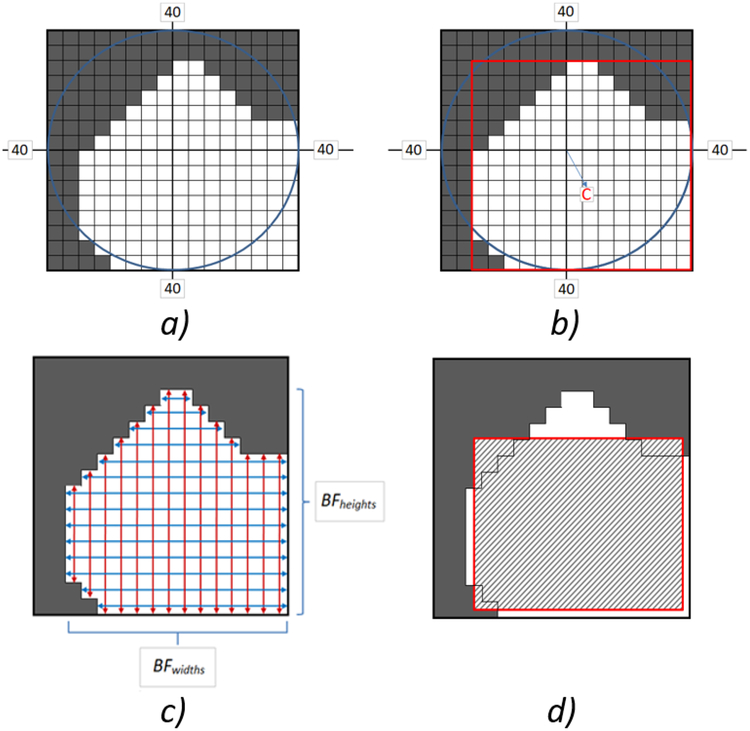

We applied a two-dimensional cubic interpolation to the modified binary VF image to achieve the desired output image size (Figure 3.A). This resized visual field image was used as a template to map the test images into the largest intact region of the visual field; marked regions with pixel values of 1. Based on this interpolated binary field image, the intact field’s region properties were calculated. These region properties were: 1) intact areas in units of pixels squared, 2) region bounding box, 3) weighted area centroid, and 4) a list of all pixels constituting the intact regions of the VF. A bounding box is the smallest rectangle enclosing all pixels constituting the intact region. The bounding box of the example in (Figure 3.A) is shown in (Figure 3.B) marked with a red box. The dimensions of the bounding box were used in the resizing phase of the remapping function. A region centroid is the center of mass of that region calculated in terms of horizontal and vertical coordinates (Figure 3.B). The values of this property correspond to the output image’s new center; i.e. amount of image shift required for remapping. Weighted area centroids take into account the location and intensity values of those regions, which resulted in a more accurate estimate for the output image’s new center.

Figure 3:

a) Interpolated visual field after elimination of small blind regions. b) The intact field’s bounding box and center of mass C. c) Calculation of the intact field’s widths BFwidths and heights BFheights using the region’s bounding pixels. d) Remapped output image fitted inside the visual field’s intact region.

If multiple intact regions existed in the field and based on the intact regions area property, only one area is used for mapping. The intact areas were sorted from largest to smallest, and only the largest area was selected to fit the input image. This ensures a maximized utilization of the remaining intact field. Then, using the list of pixels constituting the largest intact field, the widths and heights of all pixels bounding it were calculated (Figure 3.c). For each row in the intact field, the two bounding pixels were located and their vertical coordinates were subtracted to calculate the field width BFwidth at that specific row. This width calculation was iterated for all rows thereby establishing the considered intact field to calculate BFwidths. The same iteration was applied on a column basis to calculate BFheights. Afterwards, a scaling equation was used to determine the new size of the remapped output image; Widthremap and Heightremap. The resizing function was:

| (1) |

where BFwidths and BFheights are the calculated intact field’s bounding pixels’ widths and heights, BXwidths, BXheights are the bounding box width and height, Isize is the output image size, respectively. The summations in the numerators approximate the intact field area calculated with respect to the horizontal and vertical directions, respectively. Therefore, dividing those summations by the square of the output image’s size provided an estimate of the proportional image areas to be remapped in each direction. These proportions are then multiplied by the corresponding bounding box dimension that was previously calculated. The remapping behavior of this method is to fit images in the largest intact visual field while trying to preserve the output image’s aspect ratio (Figure 3.D).

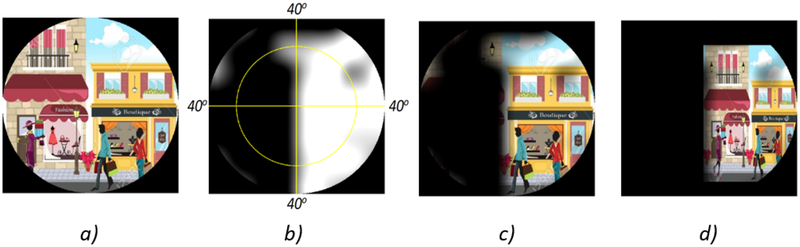

Figure 4 shows an example application of the remapping process to automatically fit an image within the intact part of a given VF. (Figure 4.A) shows an Image as seen through normal vision. (Figure 4.B) is an example VF with peripheral defects. (Figure 4.C) shows the image without remapping where only one building can be seen. (Figure 4.D) shows the remapped image where the two buildings can be noticed. VF was overlaid over the image in (Figures 4.C and D) for demonstration purposes only.

Figure 4:

An example showing the image remapping process: a) Example Image. b) Visual Field (VF) with peripheral defects. c) Image as shown without remapping: only one building can be seen. d) Image with remapping: the two buildings can be seen. VF was overlaid over the image in c) and d) for demonstration purposes only.

To benchmark the effectiveness of the image remapping method in functionally improving a specific field of view, the used test images included simple objects shown in the periphery such as trees, cars, roads, and the participants were asked to describe seeing these objects. The test images were first shown in the HMD without remapping then again after remapping. Two types of image remapping experiments were performed. The first experiment focused on finding and recognizing a primary object in the test image, mainly a car as a safety hazard. The car location in each test image was positioned to test one of the four VF quadrants. The test images were first shown to the patients without image remapping and the participants were asked to identify any object they could see. This testing setup avoided the learning effect that could occur if the patient saw the car using image remapping first, where he/she could look for it with eye scanning if the setup was revered. In this experiment, the recorded responses were either the patient identified the safety hazard or not, before and after application of image remapping. The second experiment used test images showing multiple peripheral objects (such as cars), and the participants were asked to count the number of objects before and after applying image remapping. In this second experiment, the recorded responses were the number of objects the patients could count, before and after activating the image remapping algorithm.

Statistical analyses were performed using MATLAB R2018b (MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA) to calculate descriptive statistics for all measurements and recorded responses. Mean ± standard deviation (SD) values were used to describe all VF measurements errors. In the peripheral object identification experiment, Chi square tests were performed to statistically test whether there is a significant difference between the patients’ responses before and after activation of image remapping. In the object counting experiment, Wilcoxon rank-sum testing was performed to test for significance between the patients counts before and after remapping. To assess the correlation of different VF defect severity measures and the patient’s improved scores, we used Pearson’s linear correlation analysis. Mean Deviation (MD), Pattern Standard Deviation (PSD), and the Visual Field Index (VFI) measures were included in the correlation analysis, as being VF defects characterization parameters.26, 27 P-values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

VF MEASUREMENTS:

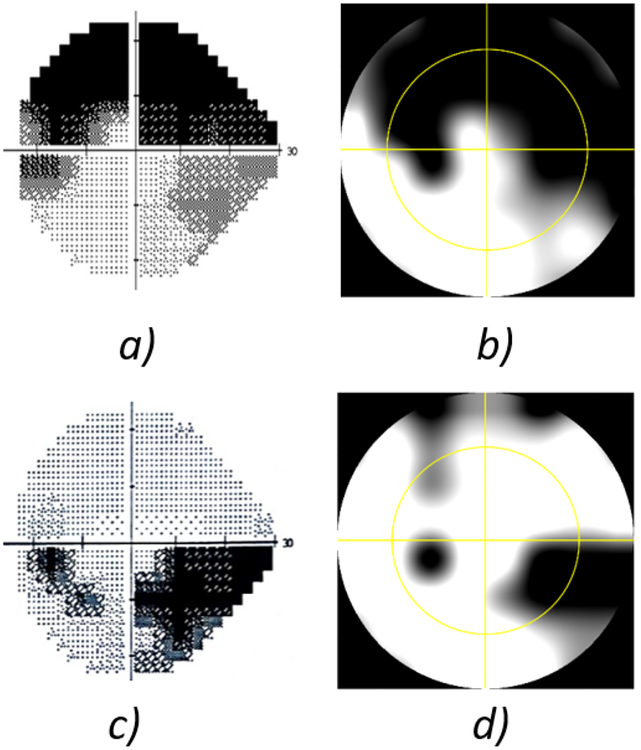

The age range was 30 to 90 years with mean value of 66.77 ± 13.89 years old. (Figure 5) shows two comparative examples using both Humphrey VF SAP (on the left column) and DSpecs VF testing (on the right column), for two different eyes of two patients. The yellow circles in (Figure 5.B) and (Figure 5.D) geometrically match the 24-degree radius of the HFA test shown on (Figure 5.A) and (Figure 5.C), respectively. The similarity between the two VF measurement methods is evident.

Figure 5:

Testing visual field (VF) defects for two cases: Left column: a) and c) Humphrey VF test using the central 24–2 protocol. Right column: b) and d) VF test using our new device covering the central 40 degrees. The yellow circle approximately represents the central 24 degrees’ area for comparison purposes.

Failure of the two tests to demonstrate the same visual field defect can be attributed to the subjectivity nature of the test, therefore the error points were recorded for all recruited cases and error percentages were calculated accordingly. The mean errors and standard deviations for the patient study are listed in (Table 1), as number of error points and also as error percentages calculated by dividing the number of test points in error over the total number of common testing points; 40 points in the central visual testing area. The overall average error was found to be 7.652 ± 5.301 %.

Table 1:

Mismatch error calculations between visual field measurements using standard automated perimetry and the digital spectacles for 23 glaucoma patients based on point to point comparisons.

| Left Eyes | Right Eyes | Total Error | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Error Points | 3.059 | 2.277 | 3.063 | 2.016 | 3.061 | 2.120 |

| Error Percentage | 7.647 % | 5.692 % | 7.656 % | 5.039 % | 7.652 % | 5.301 % |

IMAGE REMAPPING:

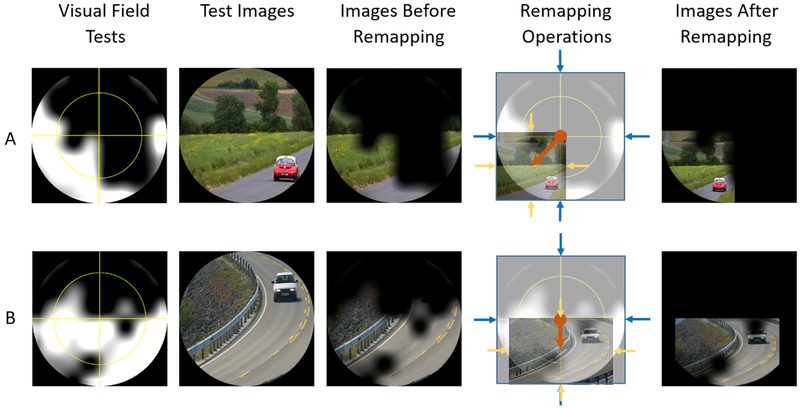

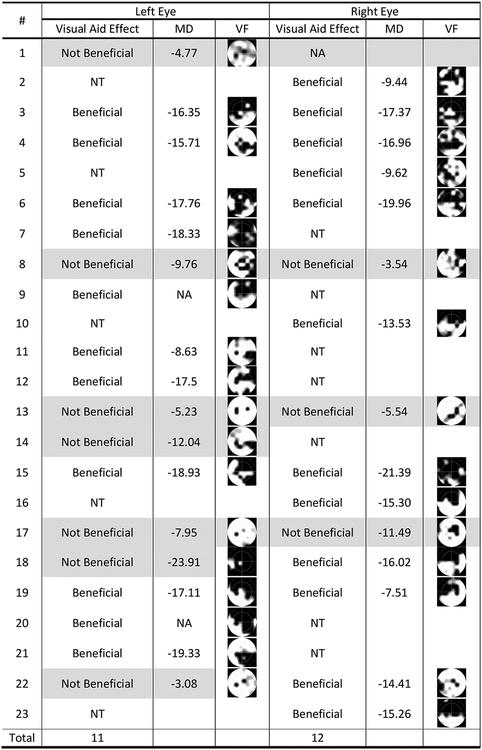

Two test examples are shown in (Figure 6. A and B), where the patients could only recognize the cars after image remapping was applied; fifth column in (Figure 6). The fourth column shows the applied remapping operations in each example, where image shifting amount was represented by the length of the orange arrow, and resizing was represented by the ratio between the bounding blue arrows (original image size) to the bounding yellow arrows (remapped image size). In most cases (18 of 23), the car was not identified by the patients, but after applying remapping the car was seen. Some patients could identify only parts of the car before applying image remapping, but could not identify its color or moving direction. Five of the 23 participants could identify the object without image processing. Therefore, the new visual aid was beneficial to 78% of the patients. Patient responses for each eye, whether mapping was beneficial or not in each case are summarized in (Figure 7). Patients who did not benefit were highlighted. The DSpecs significantly improved the functional VF of the participating patients (23/33, Chi square test, P value = 0.024, 5 % significance level).

Figure 6:

Image remapping for two glaucoma cases. First column: Visual Field (VF) measurements made with the Digital Spectacles. Second column: Test Images. Third column: Test Images as shown to the patient without remapping; patients could see only roads. Fourth column: Image remapping; shifting represented by the orange arrow, and resizing represented by the yellow and blue arrows. Fifth column: Test Image with remapping. VF was overlaid over the test image in the third and fifth columns for demonstration purposes only.

Figure 7:

Responses for identifying safety hazards after displaying the test images on the digital spectacles. MD: Mean Deviation. VF: measured visual field using our spectacles. NT: Normal eye, Not Tested. NA: Value Not Available.

In the second experiment, a different test image was shown to the patients, where this image presented a highway scene with 16 cars running in two lanes. Patients were asked to indicate the number of cars they could see before and after image remapping. For all patients, car counts were recorded for each eye individually (Table 2). Patients could count more cars after activating the image remapping algorithm. Additionally, the peripheral objects counting performance was found to be significantly improved after performing image remapping with the visual aid (Wilcoxon rank sum test, P = 0.0026, 5 % significance level). The p-value was calculated for each eye between the two car counts, with and without image remapping.

Table 2:

Patients’ Identification and counting of peripheral objects with and without the digital spectacles image remapping.

| Case # | Left Eye | Right Eye | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count with image remapping | Count without image remapping | Count with image remapping | Count without image remapping | |

| 1 | 16 | 16 | Count NA | Count NA |

| 2 | Count NA | Count NA | 16 | 15 |

| 3 | 13 | 5 | 15 | 11 |

| 4 | 16 | 14 | 15 | 15 |

| 5 | Count NA | Count NA | 14 | 10 |

| 6 | 10 | 6 | 9 | 6 |

| 7 | 10 | 8 | Count NA | Count NA |

| 8 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| 9 | 13 | 7 | Count NA | Count NA |

| 10 | Count NA | Count NA | 14 | 5 |

| 11 | 15 | 11 | Count NA | Count NA |

| 12 | 12 | 9 | Count NA | Count NA |

| 13 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| 14 | 16 | 15 | Count NA | Count NA |

| 15 | 12 | 9 | 7 | 4 |

| 16 | Count NA | Count NA | 14 | 8 |

| 17 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 15 |

| 18 | Count NA | Count NA | 16 | 8 |

| 19 | 16 | 6 | 14 | 10 |

| 20 | 10 | 4 | Count NA | Count NA |

| 21 | 15 | 7 | Count NA | Count NA |

| 22 | 16 | 16 | 15 | 14 |

| 23 | Count NA | Count NA | 14 | 6 |

| Average Counts | 13.94 | 10.63 | 14.13 | 10.93 |

| P-Value | 0.0026 | |||

Count NA: Count Not Available for the corresponding case.

Additionally, correlation analysis was performed between improvement scores of the object counting experiment, and the three parameters characterizing SAP VF defects (MD, VFI, and PSD). The improvement scores were calculated as the difference between the counts before and after image remapping for each eye (Table 2). Pearson’s linear correlation analysis showed a significant correlation of the MD (r-0.42; P-value 0.02), the PSD (r 0.46; P-value 0.01), and the VFI (r-0.41; P-value 0.022) with the DSpecs remapping improvement scores.

DISCUSSION

We developed and tested a technology to benefit patients suffering from peripheral visual field defects by expanding their functional field of view and potentially improve performance in their visually intense life activities.28, 29

Previous computer processing techniques that were designed to aid vision were first developed by Loshin and Juday in 1989, who described a remapping algorithm based on image warping that can aid peripheral VF defects associated with retinitis pigmentosa. However, they studied no patients with this algorithm, and continued their studies focusing on central defects by testing with TV screen reading experiments.30, 31 Although the benefit of this technology was hypothesized, no visual aid was developed; owing to technological barriers. Other, available commercial devices11, 16, 17, 32 apply general image enhancements, such as magnification and brightness without taking into account the specific VF defect. These improved performances were based on central VF defects, but provided very limited benefits for activities that depend on the peripheral VF.11, 12, 17 Peli and associates reported a visual aid to expand the field of view for patients with tunnel vision due to retinitis pigmentosa by providing a minified contours of the patient surroundings.14, 33–36 Their approach was limited to displaying expanded contours and edges of objects that were captured with a camera. This was implemented on a number of commercial HMDs; however, even though it increased the field of view, it was not effective in improving patients’ ability to avoid collisions.34 Recently, they reported the use of peripheral prisms to help patients with peripheral VF losses to detect pedestrians, and tested their visual aid with a VR simulator. Despite the significant improvement of peripheral detection, the small apertures of the visual aid and the inevitable optical confusion and overlap were major shortcomings.37

In contrast to the previous studies, our DSpecs approach has the advantage of customizing the vision augmentation based on patient’s unique VF defect. VF augmentation is done by displaying real images that are processed and relocated into the remaining intact visual field. Our approach does not exhibit image overlap nor optical confusion artifacts, since the whole test image is being remapped. The DSpecs performs a diagnostic test before processing to ensure that what is displayed conforms with the personalized participant’s VF geometrically. The purpose of our DSpecs VF measurement was to guide the image remapping algorithm by identifying the intact VF regions. These measurements are not directly comparable to those obtained with the standard automated perimetric analysis. Our VF measurements had an acceptable error of 7.65% with the DSpecs compared with the commonly utilized testing strategy. Furthermore, the DSpecs is more case specific, as it has the potential to help various peripheral VF defects, including peripheral glaucoma defects. The results of this study have shown evidence that peripheral awareness can be improved using the DSpecs.

The VF testing data with the DSpecs was incorporated to provide two advantages. First, with this technique no eye misorientation or calibration issues, such as lens rim artifact or head malpositioning occurred. Second, the diameter of the VF with the DSpecs was larger than the standard 24–2 or 30–2, which better approximates the area of display’s field of view and covers more of the peripheral vision. To our knowledge, no similar visual aid can be used to diagnose a VF defect and apply a visual correction profile.

Although ability of most patients with peripheral VF defects to identify hazards was improved with DSpecs, not everyone benefitted. As shown in (Figure 7), some patients recognized the peripheral object without applying image remapping. Patients with minor peripheral defect cases did not appreciate the produced visual profile and some expressed minor improvements, such as the object being easier to find using the remapped images. These patients likely scanned the test images using eye movements and compensated for their VF defect. Another case had a severe VF defect in the left eye that even the produced remapped image was not beneficial, as the object was not seen because of the extremely narrow remaining VF to fit the image. It was also noted that the DSpecs algorithm was most effective with patients with moderate continuous peripheral field defects. Correlation analysis suggests that the MD, PDS, and VFI metrics might be predictive parameters for potential functional improvements with image remapping.

Limitations of this proof of concept study include the usage of only static images for testing. Activities of daily living are normally based on responding to dynamic moving objects. Peripheral awareness is very important to sustain adequate mobility performance.7, 38 A dynamic testing environment with an adequate sample size is needed to ultimately prove the usefulness of this DSpecs to improve patient’s ability to avoid moving obstacles. Real time video image remapping will be necessary to conduct such experiment. Another limitation, is the subjective nature of VF testing and the accuracy of the produced visual augmentation profile consequently depends on the accuracy of the measured VF. Repetitive measurements and averaging strategies can be employed to overcome this limitation. One more limitation of the study, is the utilization of subjective patients’ responses to test images as the test scores, therefore patient factors such as their level of understanding of the test processes or familiarity with the VR headset could influence their responses.

The minified and shifted visual perception might affect hand and body movements while performing daily tasks. We believe that proprioception might play an important role in determining directional orientations, and only training will be needed to achieve good hand and body coordination with the modified spectacles visual perspective. Evaluation of the patients’ ability to maintain stereopsis while the displayed images are being remapped for both eyes (i.e. binocular vision) is another point to investigate, and new remapping algorithms will be needed to eliminate the binocular rivalry effects. Driving is an important activity that many patients with peripheral VF defects cannot perform safely anymore, as they tend to miss peripherally projected stimuli.39 Our spectacles may help these patients restore their awareness of the peripheral safety hazards associated with driving. Implementation of the DSpecs using an Augmented reality (AR) platform would produce a visual aid that is more user friendly, light weight, and socially acceptable for the daily real-life usage. These points are all considered in our future studies.

We believe that this new digital glasses technology may help patients with peripheral VF defects functionally restore a wider field of view. The glasses display algorithms allowed the test subjects to identify safety hazards that they could not do without their use. The glasses significantly allowed the recruited patients to quantify more objects in the periphery. This highlighted the positive impact of the DSpecs to potentially restore these patients’ ability to perform many aspects of their visually intense activities.

FUNDING/SUPPORT:

This research has been partially supported by the National Institute of Health (NIH) under Grant # K23 KEY026118A. Research and its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NIH.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES:

United States Non-Provisional Pending Patent (Application No. 16/144,995) (MA) and United States Non-Provisional Filed Patents (Application No. 16/367,633, 16/367,687 and 16/367,751) (MA, AS).

REFERENCES

- 1.Quigley HA, Broman AT. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(3):262–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Owsley C, McGwin G, Jr., Lee PP, Wasserman N, Searcey K. Characteristics of low-vision rehabilitation services in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127(5):681–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor DJ, Hobby AE, Binns AM, Crabb DP. How does age-related macular degeneration affect real-world visual ability and quality of life? A systematic review. BMJ Open. 2016;6(12):e011504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dhital A, Pey T, Stanford MR. Visual loss and falls: a review. Eye (Lond). 2010;24(9):1437–1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown JC, Goldstein JE, Chan TL, Massof R, Ramulu P, Low Vision Research Network Study G. Characterizing functional complaints in patients seeking outpatient low-vision services in the United States. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(8):1655–1662 e1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson P, Aspinall P, Papasouliotis O, Worton B, O’Brien C. Quality of life in glaucoma and its relationship with visual function. J Glaucoma. 2003;12(2):139–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedman DS, Freeman E, Munoz B, Jampel HD, West SK. Glaucoma and mobility performance: the Salisbury Eye Evaluation Project. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(12):2232–2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirooka K, Sato S, Nitta E, Tsujikawa A. The Relationship Between Vision-related Quality of Life and Visual Function in Glaucoma Patients. J Glaucoma. 2016;25(6):505–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinreb RN, Aung T, Medeiros FA. The pathophysiology and treatment of glaucoma: a review. JAMA. 2014;311(18):1901–1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans K, Law SK, Walt J, Buchholz P, Hansen J. The quality of life impact of peripheral versus central vision loss with a focus on glaucoma versus age-related macular degeneration. Clin Ophthalmol. 2009;3:433–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patodia Y, Golesic E, Mao A, Hutnik CM. Clinical effectiveness of currently available low-vision devices in glaucoma patients with moderate-to-severe vision loss. Clin Ophthalmol. 2017;11:683–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ehrlich JR, Ojeda LV, Wicker D, et al. Head-Mounted Display Technology for Low-Vision Rehabilitation and Vision Enhancement. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;176:26–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ehrlich JR, Spaeth GL, Carlozzi NE, Lee PP. Patient-Centered Outcome Measures to Assess Functioning in Randomized Controlled Trials of Low-Vision Rehabilitation: A Review. Patient. 2017;10(1):39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peli E Vision multiplexing: an engineering approach to vision rehabilitation device development. Optom Vis Sci. 2001;78(5):304–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehr EB, Quillman RD. Field Expansion by Use of Binocular Full-Field Reversed 1.3x Telescopic Spectacles. Am J Optom Phys Opt. 1979;56(7):446–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Culham LE, Chabra A, Rubin GS. Clinical performance of electronic, head-mounted, low-vision devices. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2004;24(4):281–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Markowitz SN. State-of-the-art: low vision rehabilitation. Can J Ophthalmol. 2016;51(2):59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Virtanen P, Laatikainen L. Low-vision aids in age-related macular degeneration. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 1993;4(3):33–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewis CW, Mathers DR, Hilkes RG, Munger RJYB, Colbeck RP, Inventors; Esight Corp, Assignee. Apparatus and method for augmenting sight. US patent 8,494,298 B2, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Antaki Pr, Dunn R, Lemburg R, Inventors; Evergaze Inc, Assignee. Apparatus and method for improving, augmenting or enhancing vision. European patent EP3108444A1, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hilkes R, Jones F, Rankin K, Inventors. Apparatus and method for enhancing human visual performance in a head worn video system. European patent EP2674805A2, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wittich W, Lorenzini MC, Markowitz SN, et al. The Effect of a Head-mounted Low Vision Device on Visual Function. Optom Vis Sci. 2018;95(9):774–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ehrlich JR, Moroi SE. Comment on “Clinical effectiveness of currently available low-vision devices in glaucoma patients with moderate-to-severe vision loss”. Clin Ophthalmol. 2017;11:1119–1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson DR. Automated static perimetry. St. Louis: Mosby Year Book; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Low FN. Peripheral visual acuity. AMA Arch Ophthalmol. 1951;45(1):80–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ng M, Sample PA, Pascual JP, et al. Comparison of visual field severity classification systems for glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2012;21(8):551–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bengtsson B, Heijl A. A visual field index for calculation of glaucoma rate of progression. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145(2):343–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barabas J, Woods RL, Peli E. Walking simulator for evaluation of ophthalmic devices. P Soc Photo-Opt Ins. 2005;5666:424–433. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tatham AJ, Boer ER, Gracitelli CPB, Rosen PN, Medeiros FA. Relationship Between Motor Vehicle Collisions and Results of Perimetry, Useful Field of View, and Driving Simulation in Drivers With Glaucoma. Transl Vis Sci Techn. 2015; 4(3):1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ho JS, Loshin DS, Barton RS, Juday RD. Testing of remapping for reading enhancement for patients with central visual field losses. Visual Information Processing Iv. 1995;2488:417–424. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loshin DS, Juday RD. The programmable remapper: clinical applications for patients with field defects. Optom Vis Sci. 1989;66(6):389–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robert Hilkes OCFJ, Carp(CA); Kevin Rankin, Kanata (CA), Inventors; ESight Corp., Assignee. Apparatus and Method for Enhancing Human Visual Performance in a Head Worn Video System. US Patent 10,225,526 B2, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peli E, Luo G, Bowers A, Rensing N. Applications of Augmented Vision Head-Mounted Systems in Vision Rehabilitation. J Soc Inf Disp. 2007;15(12):1037–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo G, Woods RL, Peli E. Collision Judgment When Using an Augmented-Vision Head-Mounted Display Device. Invest Ophth Vis Sci. 2009;50(9):4509–4515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hwang AD, Peli E. An augmented-reality edge enhancement application for Google Glass. Optom Vis Sci. 2014;91(8):1021–1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luo G, Peli E. Use of an augmented-vision device for visual search by patients with tunnel vision. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(9):4152–4159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qiu C, Jung JH, Tuccar-Burak M, Spano L, Goldstein R, Peli E. Measuring Pedestrian Collision Detection With Peripheral Field Loss and the Impact of Peripheral Prisms. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2018;7(5):1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Turano KA, Rubin GS, Quigley HA. Mobility performance in glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40(12):2803–2809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vega RP, van Leeuwen PM, Velez ER, Lemij HG, de Winter JCF. Obstacle Avoidance, Visual Detection Performance, and Eye-Scanning Behavior of Glaucoma Patients in a Driving Simulator: A Preliminary Study. Plos One. 2013;8(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]