Abstract

Osteoclasts (OC) originate from either bone marrow (BM)-resident or circulating myeloid OC progenitors (OCP), expressing the receptor CX3CR1. Multiple lines of evidence argue that OCP in homeostasis and inflammation differ. We investigated the relative contributions of bone marrow-resident and circulating OCP to osteoclastogenesis during homeostasis and fracture repair. Using CX3CR1-EGFP/TRAP tdTomato mice we found CX3CR1 expression in mononuclear cells but not in multinucleated TRAP+ OC. However, CX3CR1-expressing cells generated TRAP+ OC on bone within 5 days in CX3CR1CreERT2/Ai14 tdTomato reporter mice. To define the role that circulating cells play in osteoclastogenesis during homeostasis, we parabiosed TRAP tdTomato mice (CD45.2) on a C57BL/6 background with wild type (WT) mice (CD45.1). Flow cytometry (CD45.1/.2) demonstrated abundant blood cell mixing between parabionts after 2 weeks. At 4 weeks there were numerous tdTomato+ OC in the femurs of TRAP tdTomato mice but almost none in WT mice. Similarly, cultured BM stimulated to form OC demonstrated multiple fluorescent OC in cell cultures from TRAP tdTomato mice but not from WT mice. Finally, flow cytometry confirmed low - level engraftment of BM cells between parabionts but significant engraftment in the spleens. In contrast, during fracture repair, we found that circulating CX3CR1+ cells migrated to bone, lost expression of CX3CR1 and became OC. These data demonstrate that OCP but not mature OC express CX3CR1 during both homeostasis and fracture repair. We conclude that in homeostasis mature OC derive predominantly from bone marrow-resident OCP, while during fracture repair, circulating CX3CR1+ cells can become OC.

Keywords: Osteoclast progenitor cells, CX3CR1, osteoclast, cell tracking and osteoimmunology

Introduction:

Bone homeostasis is a complex process, requiring the precise coordination between bone-forming and bone-resorbing cells. Osteoclasts (OCs) are the only cells that can efficiently resorb bone. Pathologic regulation of OC formation and function contributes to the development of diseases, like inflammatory osteolysis and osteoporosis, which produce low bone mass and an increased risk of fragility fractures (1). OC-mediated bone resorption is critical for bone remodeling, which maintains the structural integrity of the skeleton by replacing worn or micro-fractured bone (1).

The OC is a unique, large, multinucleated cell, originating from a common mononuclear myeloid precursor that can also differentiate into macrophages and dendritic cells (2). While the hematopoietic origin of the OC is well established (3, 4), the identification of its direct progenitor cell is not fully resolved (2, 5). In addition, it remains unclear whether OCs in either pathologic or homeostatic conditions derive predominantly from a circulating monocyte precursor or a bone marrow-resident progenitor that commits to the OC lineage without circulating.

Our group characterized a population of murine osteoclast progenitors (OCP) that were isolated from bone marrow as CD45R− CD3− CD11blow/− CD115+, CD117high, intermediate or low. These OCP are able to differentiate and mature in vitro into OCs with greater than 90 % efficiency as determined by single cell cloning. In addition, others demonstrated that OCP in murine bone marrow express the receptor CX3CR1 for the chemokine, fractalkine (CX3CL1) (6, 7). CX3CR1 is membrane-bound and functions as both a chemoattractant and adhesion molecule (8). CX3CL1 is produced by osteoblasts and has been shown to play a role in osteoclastogenesis through its ability to attract OCPs to the resorption site (6, 7). In turn, this result suggests a role for CX3CR1, which is expressed on OCP (6, 9), in regulating OC migration. Initial studies of the persistence of CX3CR1 expression during OC maturation were performed in vitro and used murine bone marrow cells (6, 7). These demonstrated an almost complete downregulation of CX3CR1 expression in mature OCs. However, interpretation of the later finding is complicated by the results of Ibanez et al. who described a separate origin for OCs that were induced under inflammatory conditions (10). These authors found that a proportion (20 to 30%) of inflammatory OCs maintained expression of CX3CR1 throughout maturation. In contrast, they reported that expression of CX3CR1 on OCs derived during non-inflammatory conditions was less frequent (4 to 7%).

Currently, there is strong evidence that circulating cells are a source of OCP during states that “open” or perturb the integrity of the bone marrow microenvironment. These include fracture (11), inflammation (5), enhanced resorption (12), osteoblast death (13) and defective osteoclast function (14). However, the relative roles that bone marrow-resident and circulating cells play in osteoclastogenesis during unperturbed or homeostatic conditions is controversial. Data implicating both bone marrow-resident and circulating cells as the major source of OCP during homeostasis have been reported (12, 13, 15).

In this study, we used newer and more sensitive techniques than those employed previously to investigated the rate that OC matures from precursors in vivo and the role that circulating and bone-resident OCP play in the development of mature OCs during homeostasis and fracture repair. We first evaluated how rapidly OCP expressing CX3CR1 differentiate into mature OCs in vivo using CX3CR1CreERT2/Ai14 mice. In addition, because, CX3CR1 labels both bone marrow and circulating myeloid OCP, we examined the contribution that circulating cells made to osteoclastogenesis using a shared-blood parabiosis system. This model employed TRAP tdTomato mice, which express high levels of the tdTomato fluorescent protein in mature OC to identify circulating cells that formed OC in bone. Finally, using dual transgenic CX3CR1-GFP/TRAP tdTomato mice, we isolated CX3CR1+ bone marrow cells and injected these into the circulation of mice undergoing fracture repair to determine if circulating CX3CR1+ cells could incorporate into mature OC during this process.

Materials and Methods:

Experimental Animals:

Female mice in a C57BL/6 background were used for all experiments, except for adoptive transfer experiment where males were used. Unless otherwise stated, all mice were analyzed between 14 and 15 weeks of age. CX3CR1CreER mice (16) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Stock No: 020940) and housed in the Center for Comparative Medicine at the UConn Health under standard housing conditions. These mice have exon 1 of their Cx3cr1 gene replaced by a construct that expresses Cre-ERT2. Because the construct was “knocked into” the Cx3cr1 gene, its expression is controlled by the endogenous Cx3cr1 gene regulatory elements. CX3CR1CreER mice were crossed with Ai14 Cre reporter mice from Jackson Laboratories (Stock No: 007914) to generate CX3CR1CreER/Ai14 mice. The Ai14 Cre reporter mouse line produces red fluorescent tdTomato protein in cells that express active Cre recombinase and their progeny.

TRAP tdTomato mice were a gift from Dr. Masaru Ishii (17) (Immunology Frontier Research Center, Osaka University, Osaka, Japan). This transgenic mouse contains a bacterial artificial chromosome construct that utilizes the endogenous mouse Acp5 regulatory sequence to drive expression of tdTomato protein.

CX3CR1-GFP mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Stock No: 005582) (18). A C57BL/6 congenic strain that expresses CD45.1 rather than CD45.2, which is present on most C57BL/6 mouse lines, was obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Pep Boy, Stock No: 002014).

All animals used were heterozygous for the transgene used (CX3CR1-GFP or TRAP tdTomato).

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of UConn Health approved all animal protocols.

Flow cytometry and fluorescence activated cell sorting:

The antibodies used for flow cytometric analysis are all commercially available. These include anti-mouse CD117 (c-kit, clone: ACK2, APC conjugated, cat. no. 17-1171-83, eBioscience, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and anti-mouse CD115 (c-fms, clone: AFS98, biotinylated, cat. no. 13-1152-85, eBioscience, Carlsbad, CA, USA), anti-mouse CD45.1 (clone: A20, APC conjugated, cat. no. 550701, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and anti-mouse CD45.2 (clone: 104, FITC conjugated, cat. no. 11-0454-85, eBioscience, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Streptavidin PE (cat. no. 12-4317-87, eBioscience, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was used to detect CD115. Dead cells were excluded by their ability to incorporate propidium iodide. The leukocyte gate was set by the FSC and SSC properties of the cells and further analyzed for CD45.1 and CD45.2 expression. Unstained sample and single staining controls were used to set the gates for each fluorescent channel. Flow cytometric analysis was done on an LSR II flow cytometry system (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA, USA) and data analysis performed using FlowJo software (Tree Star) or FACS Diva v8 (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA, USA). Tibia and femur bone marrow cells from CX3CR1-GFP mice were isolated and sorted by the expression of GFP−, GFPlow and GFPhigh and further cultured. Sorting was performed on an Aria II (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA, USA) equipped with five lasers and 18 fluorescence detectors.

Bone marrow cell cultures:

Mouse bone marrow (BM) cells were isolated from the femur and tibia by a modification of published methods (19-21). Cells were then cultured (5 × 104 cells/wells in 96-well plates) with complete α-MEM medium (cat. no. 12571-063, Gibco, Paisley, UK) with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum [HIFBS], 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin (cat. no. 15140-122, Gibco) in the presence of mouse macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) (cat. no. M2000, Connstem, Cheshire, CT, USA) and/or mouse receptor activator of nuclear factor κ B ligand (RANKL) (cat. no. R2001, Connstem, Cheshire, CT, USA). Bone marrow macrophage/monocyte cells (BMM) cells were prepared by incubating total bone marrow cells overnight in complete α-MEM on tissue culture plastic. Nonadherent cells were collected and mononuclear cells were separated using Ficoll-Hypaque (cat. no. GE17-1440-02, GE Healthcare, Sweden) density gradient centrifugation.

Pit formation assay:

For analyzing resorptive activity of osteoclasts, pit formation assay was performed by culturing sorted CX3CR1 GFP−, GFPlow and GFPhigh bone marrow cells on UV-sterilized, devitalized bovine cortical bone slices, which we prepared. These were placed in 96-well plates. Cells were treated for 8 days with M-CSF and RANKL (both at 30 ng/ml) (2). Pit perimeter and area per OC were measured using a light microscope (BX53, Olympus Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and images analyzed by CellSens software (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

In vitro OC formation assay:

Mouse BMM were cultured at an initial plating density of 5500 cells per well in 96 well culture plates with M-CSF and RANKL (both at 30 ng/mL or dose indicated). Mouse whole BM (50,000 cells per well of a 96 well plate), spleen cells (50,000 cells per well of a 96 well plate) and blood cells (20,000 cells per well of a 96 well plate) were cultured with M-CSF and RANKL (both at 30 ng/mL) for 6 days. OC precursor population were isolated as described (2), for an in vitro OC formation assay and cultured at 5,000 cells per well in 96 well culture plates with M-CSF and RANKL. The medium was replenished every 3 days. At the completion of an experiment, cells were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 15 minutes at room temperature prior to staining for TRAP using a commercial kit (cat. no. 387A-1KT, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). TRAP-positive cells that contained more than three nuclei were counted as OC.

CX3CR1 expression in mature TRAP+ osteoclasts:

To determine expression of CX3CR1 in mature osteoclasts, we crossed CX3CR1-GFP reporter mice with TRAP tdTomato mice (CX3CR1-GFP/TRAP tdTomato). Animals were sacrificed at the age of 3 weeks, femurs dissected, fixed for 3 days in 10% formalin, transferred to 30% sucrose-PBS overnight, embedded and cut frozen on a cryostat (Leica, Germany). Slides were mounted with 4',6-Diamidino-2-Phenylindole, Dilactate (DAPI, cat. no. D-1306, Molecular probes, Eugene, OR, USA) to identify nuclei, cover-slipped and scanned (Axioscan, Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Germany). After scanning slides for identifying EGFP (green) and tdTomato (red) reporter expression and nuclear staining, sections were stained for hematoxylin and rescanned.

Real time PCR

Total RNA from BMMs cultured cells was extracted using TRI reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, Ohio) and RNA isolated by the manufacturers protocol. RNA concentration and purity were assessed on a NanoDrop one (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). One μg of RNA was transcribed to cDNA using a reverse transcription kit (cat. no. 4368814, Applied Biosystems). qRT-PCR was performed with SYBR Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher) and primers for Acp5, CX3CR1 and β-actin gene. Data are presented as relative gene expression to β-actin housekeeping gene, calculated using ΔΔCt method.

Lineage tracing:

CX3CR1CreER/Ai14 female mice at 14 weeks of age were sacrificed at either 1 or 5 days after a single subcutaneous injection of tamoxifen (75 mg per kg body weight) (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) dissolved in corn oil (Acros Organics, Belgium). Femurs were harvested and fixed for 4 days in 10% formalin, placed in 30% sucrose-PBS overnight before being cryo-embedded with Shandon Cryomatrix embedding resin (cat. no. 6769006, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and 7 μm sections cut frozen on a Cryostat (Leica, Germany). Sections were stained with anti-RFP antibody (cat. no. 600-401-379, Rockland Immunochemicals Inc., 1:200) and secondary antibody goat anti-rabbit Alexa 647 (Invitrogen, 1:500), mounted with DAPI and coverslipped. Fluorescence for tdTomato and nuclei was imaged on a fluorescent microscope (Axioscan, Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Germany). Afterwards, the coverslip was removed and the sections were stained for tartrate resistant acid phosphatase using the Leukocyte acid phosphatase kit (cat. no. 387A-1KT, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol or an Elf97 substrate (cat. no. E6589, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA). In brief, sections were prepared for fluorescent TRAP staining by incubating with TRAP buffer (112 mM sodium acetate, 50 mM sodium tartrate dibasic dihydrate and 17 mM sodium nitrite, pH 4.1–4.3) at room temperature for 10 min. TRAP buffer was removed and incubated with Elf97 substrate diluted 1:400 in TRAP buffer for 7 minutes under UV light (Spectroline XLE-1000) and washed 2 times with PBS for 5 min. OC were identified histologically as multinucleated, TRAP tdTomato positive and positive by enzyme histochemistry for immunofluorescent TRAP. OC were scored for expression of fluorescent label if they were on trabecular bone in the primary spongiosa, adjacent to the growth plate.

Parabiosis:

Isochronic anastomosis surgery was carried out using 10-week-old female mice as described previously by Donskoy and Goldschneider (22). A TRAP tdTomato mouse (CD45.2) was surgically joined to a wild type (Pep Boy, CD45.1) mouse. Parabiosed pairs were maintained for 4 weeks after surgery. Food pellets and water gel were provided on the floor of the cage in order to minimize stretching movement while the mice were adjusting to parabiosis. Establishment of a shared blood circulation was confirmed at 2 weeks after surgery in the blood of both mice by flow cytometry for cells expressing CD45.1 and CD45.2.

At 4-week post-parabiosis, animals were sacrificed and cells from the spleen, blood and bone marrow of each mouse were harvested for flow cytometry analysis to determine the relative expression of CD45.1 and CD45.2. Cells were also collected for culture in osteoclastogenic conditions. Femurs of WT and TRAP tdTomato mice were harvested, and processed for histology identically to that for lineage tracking.

CX3CR1-GFP cell transplantation in intact animals and animals with a femur fracture

CX3CR1-GFP mice was crossed with TRAP tdTomato mice to generate CX3CR1-GFP/TRAP tdTomato mice and the heterozygous progeny for both transgenes were used as a source of donor cells for adoptive transfer into wild type (WT) mice. Bone marrow cells were collected from the long bones of male 8-week old CX3CR1-GFP/ TRAP tdTomato mice and CX3CR1-GFP cells that were negative for PI were isolated on a FACS Aria II system (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA, USA). These were used as donor cells for systemic transplantation into 8-week old male C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Laboratories). Eight mice were randomly divided into two groups of four each. The first group of animals, which were not fractured, were transplanted with CX3CR1-GFP cells. The second group of animals had a femur fractured and were then adoptively transferred with CX3CR1-GFP cells immediately after being fractured. Both group of mice received a second transfer of CX3CR1-GFP cells 10 days after the first adoptive transfer. At each adoptive transfer, 5 × 105 cells were injected into the orbital sinus of a recipient mouse. For cell transplantation and fracture induction, animals were anesthetized with isoflurane. A closed transverse diaphyseal fracture of the right femur was created using a drop-weight blunt guillotine device, after inserting a 24G needle into the intramedullary canal to stabilize the fracture (23). Buprenorphine (0.1 mg/kg) was given subcutaneously during the first 2 days of healing for pain relief.

Statistical analysis:

Statistical analysis was performed by Student’s t test for comparison of two groups or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the Bonferroni post hoc test when ANOVA demonstrated significant differences for comparison of multiple groups. All experiments were repeated at least twice and representative data are shown. Statistical analyses were performed using Graph Prism 6 software (GraphPad software, CA, USA).

Results:

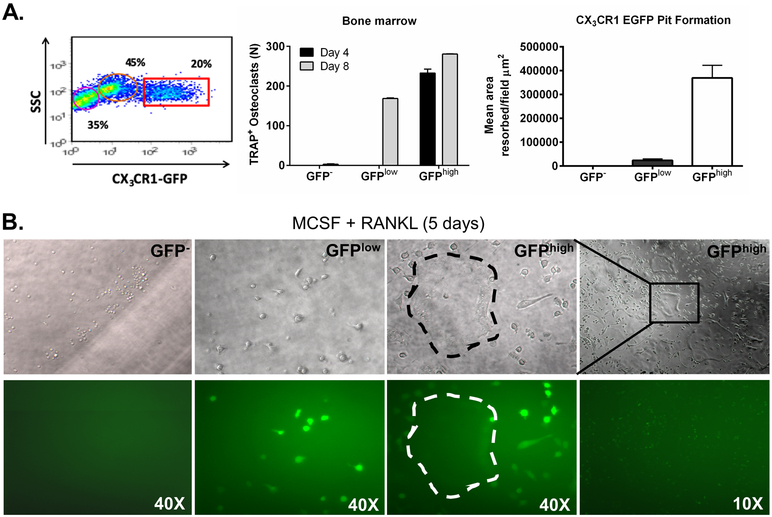

Downregulation of CX3CR1 in BM OCP with differentiation:

To confirm that CX3CR1 can be used to identify BM OCP, we sorted GFP−, GFPlow and GFPhigh BM cells from CX3CR1-GFP reporter mice, which have enhanced green fluorescent protein “knocked into” the Cx3cr1 gene (16), and cultured them with RANKL and M-CSF (30 ng/ml for both) for 5 days (Figure 1A and B). TRAP staining demonstrated that GFP− cells did not differentiate into TRAP+ OC while GFPlow cells formed mature OC, but their maturation rate was slower than that of GFPhigh cells, since they demonstrated no OC in 4-day cultures and required 8 days to produce TRAP+ OC (Figure 1A). In contrast, GFPhigh cells produced OC in vitro at both 4 and 8-days of culture. Measurement of bone resorbing activity by pit assay of cells cultured for 8 days on bovine cortical bone found that GFPhigh cells produced abundant resorption. GFPlow cells had much less resorbing activity at this time point while GFP− cells had none.

Figure 1. Bone marrow osteoclasts progenitors express CX3CR1.

A. Distribution of GFP+ cells in CX3CR1-GFP mice. Number of OC per well of a 96 well plate after plating GFP−, GFPlow and GFPhigh cells at 5000 cells per well and treating with M-CSF + RANKL (30 ng/ml for both) for 4 or 8 days. GFP negative, low and high population were sorted and cultured to determine pit formation after 8 day of culturing with M-CSF + RANKL. N=3 per group.

B. GFP negative (GFP−), GFPlow and GFPhigh cells cultures imaged under phase contrast (top four images) and fluorescent light (bottom 4 images) to demonstrate GFP expression. A large multinucleated osteoclast is outlined by dashes in the GFPhigh culture in phase contrast and fluorescent images.

Fluorescence imaging of the cultures demonstrated that GFP− cultures did not become GFP+ with culture. In contrast, in the GFPhigh culture after 4 days, immature mononuclear GFP+ cells were present (Figure 1B). Significantly, the expression of GFP in mature osteoclasts in 4-day cultures of GFPhigh cells was minimal to absent. This result is not unexpected as CX3CR1 expression was previously demonstrated to decrease as osteoclast progenitors mature into osteoclasts (6, 24). With 4 days of culture, GFPlow mononuclear cells expressed GFP at a level that was equal to GFPhigh cells at 4 days of culture. In addition, they were TRAP positive by enzyme histochemistry on day 8 of culture. These results argue that treatment with M-CSF and RANKL for 4 days induced a switch of GFPlow cells to GFPhigh cells, which may partially explain the slower maturation of GFPlow cells into OC compared to GFPhigh cells.

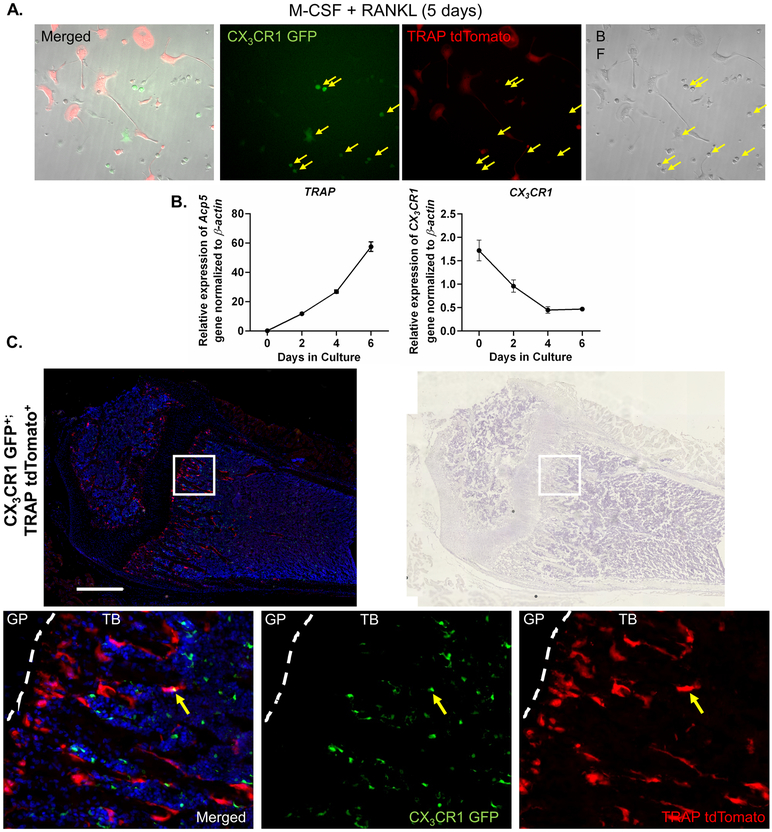

Additionally, to determine expression of CX3CR1 in mature osteoclasts and confirm our in vitro result that CX3CR1 expression in osteoclast progenitors was extinguished during their differentiation, we crossed CX3CR1-GFP reporter mice with TRAP tdTomato mice, which use the Acp5 regulatory regions to drive expression of tdTomato florescent protein (17). We cultured bone marrow cells from CX3CR1-GFP/TRAP tdTomato mice with M-CSF and RANKL for 5 days and examined the expression of the GFP and tdTomato reporters. We found that cells expressing CX3CR1 did not express TRAP, and vice versa (Figure 2A). As expected, tdTomato was predominantly expressed in large multinucleated cells while GFP was present only in mononuclear cells. Furthermore, to confirm downregulation of CX3CR1 we determine the time course of the expression of Acp5 (TRAP) and Cx3cr1 in cultured BMMs that were treated with M-CSF and RANKL (30 ng/mL for both). We found that as the BMMs differentiated expression of Acp5 increased from undetectable to its highest levels on day 6. In contrast, Acp5 expression decreased progressively from day 0 to day 6 (Figure 2B). Since mononuclear CX3CR1-expressing cells persisted in the culture (Figure 2A), it was not unexpected that Cx3cr1 mRNA expression, through day 6 of culture, never fell to undetectable levels.

Figure 2. CX3CR1 expression during OCP differentiation.

A. BMM from CX3CR1-GFP/TRAP tdTomato mice cultured with MCSF + RANKL for 5 days. Yellow arrows identify mononuclear cells expressing GFP only. There is also present red fluorescent mononuclear OCP that have committed to the OC lineage and red fluorescent multinuclear OC. Image to the far left is a composite of bright field, red and green fluorescent images.

B. BMM cultures were treated with M-CSF and RANKL (30 ng/ml for both) and relative mRNA expression of Acp5/β-actin and Cx3cr1/β-actin determined on 0, 2, 4, and 6 days of cultures. N = 3-4. Data are presented as relative expression normalized to β-actin ± SEM.

C. Fluorescent light image of the metaphyseal area from a femur of a CX3CR1-GFP/TRAP tdTomato mouse. The three bottom images are enlargements of the white box in the 2 upper images. These demonstrate, respectively, a merged, green and red fluorescence image (left) and the same section stained with hematoxylin and imaged in brightfield. The lower three images are (from left to right) a merged (green + red), green filtered and red filtered image of the same field. Only one yellow OCs (dual positive for the expression of TRAP and CX3CR1) could be detected anywhere in the bone. The yellow arrow indicates either a CX3CR1 mononuclear cell overlying a mature OC or an OCP fusing and transitioning into a mature OC. In either case the images demonstrate that levels of the GFP and tdTomato proteins were sufficient to identify additional yellow cells if dual expression were more frequent. Images in 5B (upper) were taken under 10x magnification, scale bar 500 μm.

Similar to the results of BM cell cultures from CX3CR1-GFP/TRAP tdTomato mice, we examined femurs from 3-week-old animals by frozen section histology and observed tdTomato expression predominantly in large multinucleated cells adjacent to bone while GFP expression was only observed in mononuclear cells in the trabecular bone and bone marrow. We did find an occasional double positive cell, which either represented an overlying cell or a cell transitioning from an OCP to an OC (arrow, Figure 2C). Hence, both our in vitro and in vivo data argue that CX3CR1 is expressed in OCP but not mature OC in homeostasis.

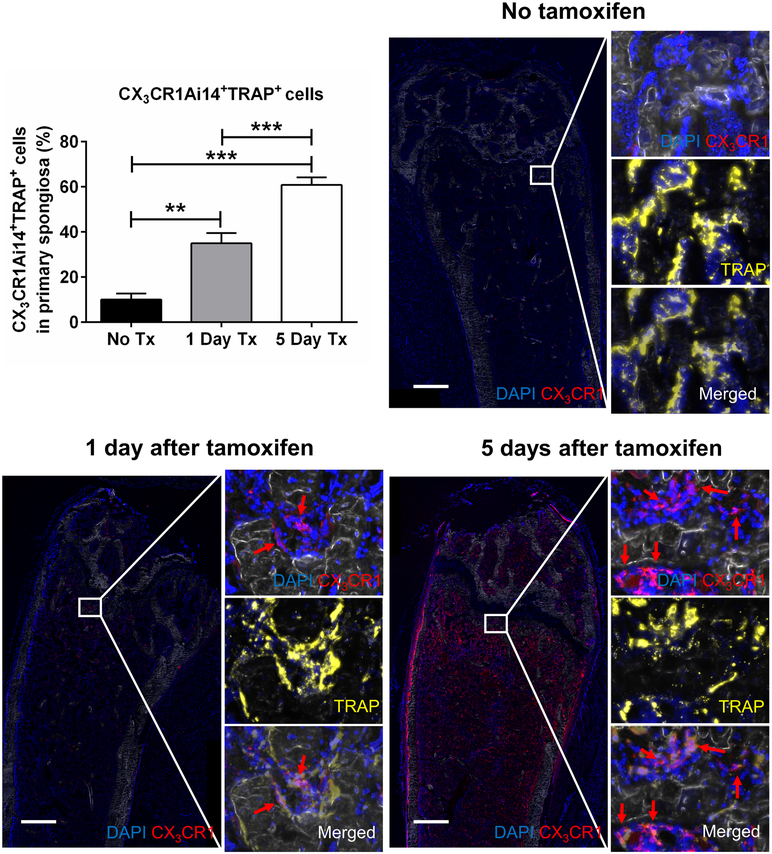

Maturation rate of OCP in vivo during homeostatic condition:

We next examined bones from CX3CR1CreER/Ai14 mice. Ai14 mice are a Cre reporter line that expresses tdTomato red fluorescent protein in cells after Cre recombination. CX3CR1CreER mice have a mutated Cre recombinase inserted into the CX3CR1 gene. This ERT2Cre is essentially inactive until the mice are treated with tamoxifen. Frozen femur sections were cut and stained with an anti-RFP Ab to increase the sensitivity of tdTomato signal and examined microscopically by immunofluorescence. Importantly, bones from CX3CR1CreER/Ai14 mice, which were not treated with tamoxifen, exhibited only an occasional tdTomato-expressing cell (10.1 ± 2.7% tdTomato fluorescent red cells of all TRAP positive cells in the primary spongiosa, lining bone surfaces) (Figure 3). This result demonstrated the minimal “leakiness” of the Cre recombinase in CX3CR1CreER/Ai14 mice.

Figure 3. Maturation of CX3CR1 OCP in vivo during homeostatic conditions.

Images of sections from the femoral bone of a CX3CR1CreER/Ai14 mouse that was not injected with tamoxifen or injected one or five days prior to sacrifice and histological analysis. To determine multinucleated cells, the sections were stained for DAPI (blue color). After tamoxifen was injected into mice, CX3CR1 expressing cells were labeled with tdTomato (red). Sections were stained for TRAP with the fluorescent substrate Elf97 (yellow) and visualized by epifluorescence. All TRAP+ cells and double positive cells for CX3CR1 and TRAP in the primary spongiosa were counted to determine % of mature osteoclast differentiating from CX3CR1 expressing cells. We also determined mononuclear CX3CR1+ expressing cells in bone marrow. Images were taken under 10x magnification, scale bar 500 μm, N=6 for non-tamoxifen treated control, N=12 for 1-day prior Tx, and N=12 for 5-day Tx group. ** Significantly different p<0.01, *** Significantly different p<0.001.

One day after a single tamoxifen injection, the CX3CR1CreER/Ai14 mouse femurs displayed significantly more tdTomato+ cells that were also TRAP+ (35.0 ± 4.6%) in the primary spongiosa, lining trabecular bone surfaces and most of these cells were mononuclear (Figure 3).

Five days after a single tamoxifen injection, the number of CX3CR1 tdTomato TRAP double positive cells was further increased (60.8 ± 3.4%) (Figures 3). In addition, cells in 5-day cultures were larger than those on day 1 and most were multinuclear. We also observed numerous mononuclear cells expressing tdTomato in the bone marrow after a single tamoxifen injection. However, those cells were TRAP negative, implying they were CX3CR1+ OCP or, more likely, monocytes of an alternate lineage.

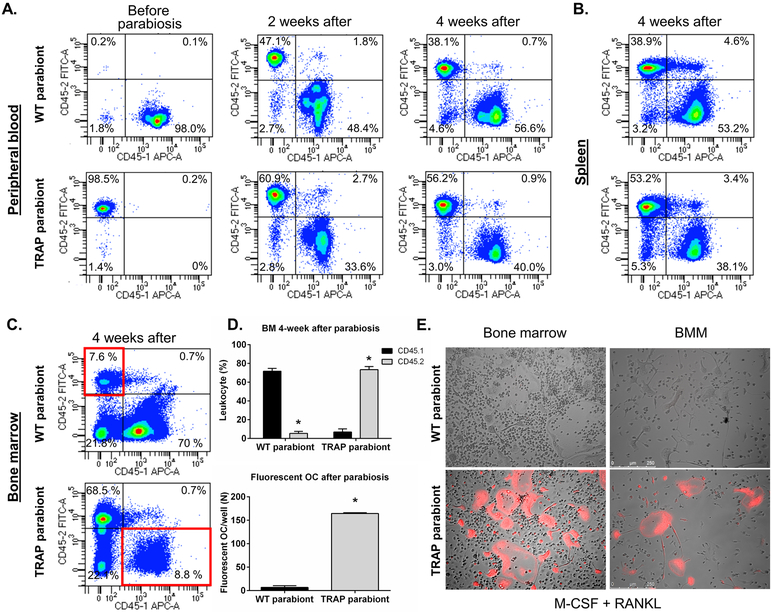

Evaluation of the circulating or BM residency of OCP

OCP can circulate in the blood (12). Hence, mature osteoclasts, under the homeostatic conditions of the previous experiment, could have originated from either a circulating cell or a cell that is bone marrow-resident and noncirculating. To test whether circulating cells contribute to osteoclast development in vivo during homeostasis, we performed parabiosis. In these experiments we created a shared blood circulation system between female WT mice and TRAP tdTomato mice (both in a C57BL/6 background) of the same age (isochronic). In order to evaluate the shared circulation, isoforms of CD45 (CD45.1 and CD45.2) were used as markers of the origin of the cells. TRAP tdTomato mice (CD45.2) were parabiosed to wild-type mice that were congenic for CD45.1. Before surgery, blood samples from both mice were analyzed by flow cytometry. In both the WT and the TRAP tdTomato mice greater than 90% of the blood cells expressed their respective marker (Figure 4A). To confirm the adequacy of parabiosis, we assessed the establishment of the shared-blood circulation by flow cytometry of blood cells 2 weeks after surgery (Figure 4A). The blood of both mice had a mixture of CD45.1 (WT: 48.5 ± 1.8% - TRAP tdTomato: 34.0 ± 2.2%) and CD45.2 (WT: 35.1 ± 2.5% - TRAP tdTomato: 54.4 ± 2.7%) positive cells proving that a shared circulation between parabiosed mice was established. Pairs were sacrificed 4 weeks after parabiosis surgery. Blood, spleen and bone marrow cells were harvested for flow cytometric analyses. Blood and spleen samples (Figure 4A and B) showed a similar mixture of CD45.1 and CD45.2 positive cells in both mice (Table 1) while in the bone marrow (Figure 4C, Table 1) there was a much lower level of engraftment of cells from the other parabiont (5.4 ± 0.8 CD45.2% in WT mice and 6.8 ± 1.3% CD45.1 in TRAP paired mice) (Figure 4D).

Figure 4. Evaluation of the circulating or BM-resident OCP.

A. Flow cytometric analysis of cells from the blood of wild type (WT) and TRAP tdTomato mice before parabiosis and 2 and 4 weeks after establishing parabiosis. Live, nucleated blood cells were analyzed for expression of CD45.1 and CD45.2. The percentages of cells expressing only CD45.1 or CD45.2 are shown. Experiments were repeated eight times with similar results and representative samples are presented.

B. Flow cytometric analysis of cells from the spleen of wild type (WT) and TRAP tdTomato mice after 4 weeks of parabiosis.

C. Flow cytometric analysis of cells from the bone marrow of wild type (WT) and TRAP tdTomato mice after 4 weeks of parabiosis.

Live, nucleated blood cells were analyzed for expression of CD45.1 and CD45.2. The percentages of cells expressing only CD45.1 or CD45.2 are shown. Experiments were repeated eight times with similar results and representative samples are shown.

D. Upper Graph: Analysis of CD45.1 cells from the wild type mice and CD45.2 cells from the TRAP tdTomato mice in the bone marrow of each parabiont calculated as the percent of total nucleated cells.

Lower Graph: The number of fluorescent osteoclasts per well that were present in BMM cultures from the wild type and TRAP tdTomato parabionts after 4 weeks. Cells were cultured with M-CSF + RANKL (30 ng/ml for each) for 5 days and then examined under UV light for the number of multinucleated fluorescence cells/well. N=4 for all groups. Experiments were repeated twice with similar results. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. * Significantly different p<0.01.

E. Representative phase contrast and epifluorescent images of cultured bone marrow cells (after 6 days of culture) and bone marrow macrophages (after 5 days of culture) from wild type (WT) and TRAP tdTomato parabiont after 4 weeks. Cells were cultured with M-CSF + RANKL (30 ng/ml for each) and imaged under fluorescent light to demonstrate tdTomato (red) expression. Experiments were repeated eight times with similar results and representative samples are shown. Scale bar, 200 μm. * Significantly different from the other parabiont, p<0.01

Table 1.

Frequency of CD45.1 and CD45.2 cells in each parabiont mice at 2 weeks and 4 weeks of parabiosis.

| Tissue | Time point | Parabiosis pair |

% CD45.1+ | % CD45.2+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood | 2 weeks | WT | 48.5 ±1.8 | 35.1 ±2.5 |

| 2 weeks | TRAP | 34.0 ±2.2 | 54.4 ±2.7 | |

| 4 weeks | WT | 62.4 ±2.0 | 33.7 ±1.7 | |

| 4 weeks | TRAP | 41.7 ±1.8 | 54.4 ±1.4 | |

| Bone marrow | 4 weeks | WT | 71.6 ±1.2 | 5.4 ±0.8 |

| 4 weeks | TRAP | 6.8 ±1.3 | 73.4 ±1.2 | |

| Spleen | 4 weeks | WT | 53.7 ±2.0 | 32.6 ±2.2 |

| 4 weeks | TRAP | 37.2 ±2.3 | 50.3 ±1.5 |

We next cultured BMM from the WT and TRAP tdTomato parabionts with M-CSF + RANKL for 5 days and examined the OC that formed in vitro under UV light to determine the number of multinucleated fluorescence cells/well. Consistent with the results of the flow cytometry for CD45.1 and CD 45.2 in the bone marrow of the mice, we demonstrated only a few (6.6 ± 3.6/well) fluorescent OC in the WT BMM cultures. In contrast, there were many more (164.3 ± 1.6/well) fluorescent OC in BMM cultures from the TRAP tdTomato parabiont (Figure 4D and 4E). Similar results were obtained when we cultured whole bone marrow cells with M-CSF and RANKL for 6 days (Figure 4E). In these experiments, the total number of TRAP + OC/well, as determined by enzyme histochemistry, was similar in all groups (Data not shown).

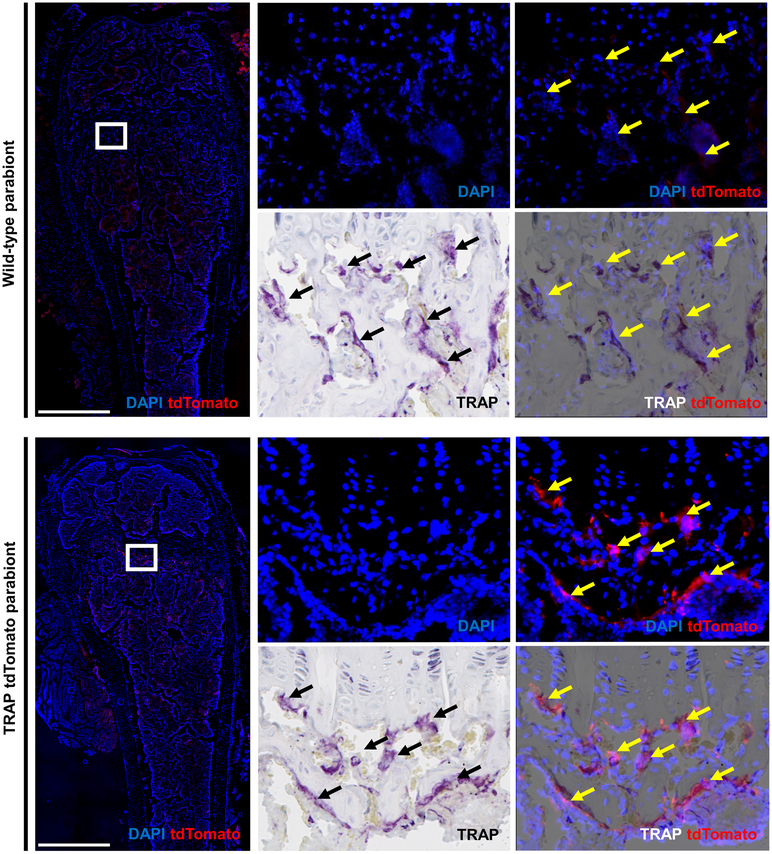

In vivo evaluation of the engraftment of tdTomato cells was performed after 4 weeks of parabiosis in pairs of mice, which at the time of sacrifice were 14-weeks-old. In these studies, 8 parabiont pairs were examined with identical results. Bones from the TRAP tdTomato mice at 14 weeks of age contained numerous large cells on bone that were multinucleated, TRAP+ by enzyme histochemistry and tdTomato+ by antibody-enhanced epifluorescence (Figure 5). Indeed, we found that in the TRAP tdTomato mice all tdTomato-positive cells were also positive for TRAP as measured by enzyme histochemistry. In contrast, bones from WT mice contained few, if any cells that were both, tdTomato+ and TRAP+ (Figure 5). However, as expected, conventional TRAP enzyme histochemical staining demonstrated abundant TRAP+ osteoclasts in the WT mice.

Figure 5. After 4 weeks of parabiosis circulatory OCP do not engraft in the primary and secondary spongiosa.

Images of sections from the femoral bone of a wild type mouse and TRAP tdTomato mouse that were parabiosed for 4 weeks. In the wild type mouse arrows indicate cells that are TRAP positive by enzyme histochemistry but are negative for tdTomato. In the TRAP tdTomato mouse arrows indicate cells that are double positive for the tdTomato reporter and TRAP as stained by enzyme histochemistry. The sections were also stained for DAPI to identify nuclei and then scanned to visualize multinuclear tdTomato positive cells. After imaging under fluorescent light, sections were stained for TRAP by enzyme histochemistry and visualized under conventional light. Two images for each slide were overlaid using Adobe Photoshop CS6 (version 6.0, Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA) and analyzed. Experiments were repeated eight times with similar results and representative samples are shown. Images are taken under 10x magnification, scale bar 500 μm.

CX3CR1-GFP cell transplantation

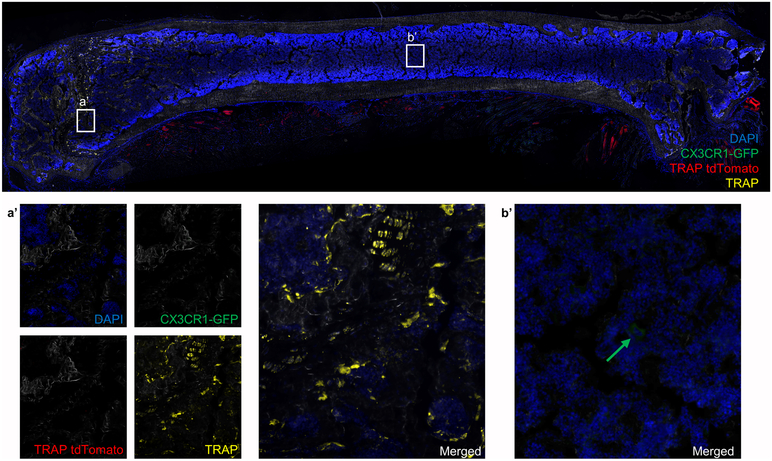

Circulating cells can be a source of OCP during states that “open” or perturb the bone marrow microenvironment (5, 11-14). To examine the role that circulating cells play as a source of OCP during fracture repair and to confirm that expression of CX3CR1 labels OCP, we adapted a protocol from the work of Göthlin and Ericsson (11). EGFP-expressing BM cells from CX3CR1-GFP/TRAP tdTomato mice were isolated by FACS and injected iv into WT recipients that either remained intact or underwent a femur fracture. Cells were injected on days 0 and 10 post-fracture and animals were sacrificed on day 18. Systemic transplantation of sorted CX3CR1-GFP cells from the BM of CX3CR1-GFP/TRAP tdTomato animals into C57BL/6 mice that were not fractured did not demonstrate any TRAP tdTomato positive cells in the femurs. In addition, only a few CX3CR1-GFP positive cells were present in the bone marrow of the femurs of these mice (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Circulatory CX3CR1-GFP cells do not incorporate into mature osteoclasts in the bones of intact mice.

Image of a section from the femoral bone of a C57BL/6 mouse that was transplanted with CX3CR1-GFP cells (sorted from CX3CR1-GFP/TRAP tdTomato mice) on day 0 and 10, and sacrificed on day 18. We could not identify TRAP tdTomato+ cells in the primary spongiosa of the intact femur (a’). Some CX3CR1-GFP cells were present in the bone marrow as indicated by green arrow (b’). N=4.

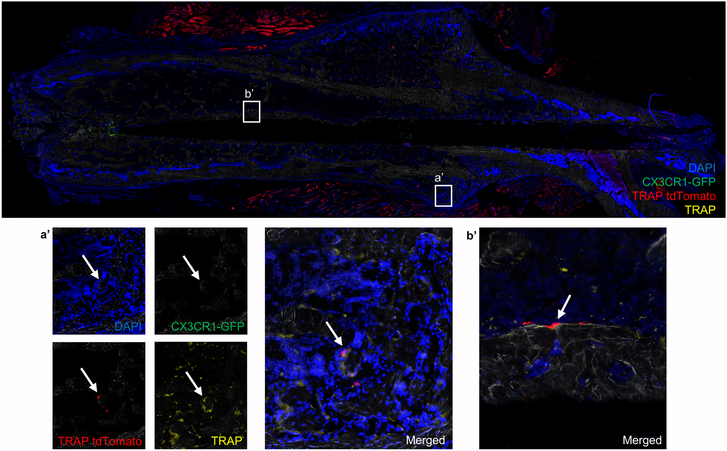

In contrast, when the same cell population was transplanted into a C57BL/6 animal that had undergone a femur fracture, multinucleated TRAP tdTomato-positive cells were present at day 18 post-fracture in the bone of the repair callus and in new bone that formed along the tract of the stabilizing pin insertion. These cells were on bone, multinucleated, and positive for TRAP as stained by fluorescent Elf97 substrate, confirming their osteoclastogenic phenotype (Figure 7). In both Figures 6 and 7 we also observed some nonspecific staining of muscle tissue by the anti-RFP antibody.

Figure 7. Fracture repair induce engraftment and incorporation of circulating CX3CR1-GFP OCP into OC.

Image of a section of femoral bone from a C57BL/6 mouse that was transplanted with CX3CR1-GFP cells (cells sorted from CX3CR1-GFP/TRAP tdTomato mice) and also fractured. The right femur was fractured following which mice received CX3CR1-GFP cells on days 0 (immediately after being fractured) and day 10 post-fracture. Mice were sacrificed on day 18 post-fracture. In the repairing callus of mice that had undergone a femur fracture, TRAP tdTomato positive cells (red) that were also positive for TRAP by fluorescent enzyme histochemistry (yellow) are present (indicated by white arrow) in the callus area (a’) and in the new bone that formed adjacent to the space occupied by the stabilizing pin (b’). N=4.

Discussion

Our results with CX3CR1-GFP mice demonstrated that the Cx3cr1 promoter/enhancer sequences identify essentially all cells in the bone marrow that have the potential to form osteoclasts in vitro. This conclusion is based on our finding that no mature OC formed in cultures from CX3CR1− murine bone marrow cells. In contrast, there was rapid (within 4 days) OC formation in vitro and bone resorbing ability (within 8 days) in cultures of cells expressing high levels of GFP. Cells that were GFPlow required a longer culture time to form mature OC, which suggests that murine bone marrow CX3CR1-GFPlow cells represent a less mature OCP compared to CX3CR1-GFPhigh cells. We expect that if cultured for longer than 8 days CX3CR1-GFPlow BM cells would eventually form abundant resorption pits; although we did not test this hypothesis.

Our studies of CX3CR1-GFP/TRAP tdTomato mice on a C57BL/6 background in homeostatic conditions argue that CX3CR1 is expressed essentially only in OCP and not in mature OC. In vitro we found that almost all cultured mononuclear cells from these mice expressed either the GFP or tdTomato marker with few cells co-expressing both. In addition, gene expression of OCP that were differentiating in BMM cultures demonstrated that Cx3cr1 was rapidly diminished while Acp5 was reciprocally increased during OC differentiation. Similarly, in vivo we found that tdTomato positive OC were almost all negative for GFP, while almost all GFP+ OCP did not express tdTomato. We speculate that the small number of cells that were double positive (expressing both CX3CR1 - green and TRAP - red) either represent overlying cells or were transitioning from OCP to mature OC.

Similar to our results, Han et al. (25) examined sections of homeostatic mouse bone from CX3CR1-GFP mice and found abundant fluorescence in mononuclear TRAP-negative cells and little fluorescence in multinucleated TRAP-positive OC. Similarly, Ibanez et al. (10), using flow cytometry on cells that they isolated from mouse bones, found that under homeostatic conditions only a small percentage (4 to 7%) of osteoclasts expressed CX3CR1 protein.

However, Ibanez et al. did find that under inflammatory conditions expression of CX3CR1 was maintained in a sub-population of osteoclasts. This result suggests that there are multiple origins of OCP and that the conditions of inflammation maintain CX3CR1 expression in mature OCs (10). Interestingly, in our studies of OCP differentiation from circulating cells during fracture repair, a state associated with inflammation (26), we did not see GFP+-OC, indicating expression of CX3CR1. However, the peak of the inflammatory response in fracture repair occurs earlier than day 18, so it is possible that by this time OC expression of CX3CR1 had been extinguished.

The data from our studies of CX3CR1CreER/Ai14 mice in vivo demonstrate the minimal “leakiness” of the CX3CR1CreER construct since, in the absence of tamoxifen, few, if any, tdTomato positive cells were present in the bones of the mice. In contrast, one day after a single injection of tamoxifen the femurs demonstrated a significant increase in tdTomato-positive and TRAP-positive cells in the secondary ossification center of the mice. These tdTomato-positive cells were relatively small compared to mature multinucleated OC, TRAP negative as measured by enzyme histochemistry and most likely represented mononuclear CX3CR1-expressing OCP or CX3CR1-expressing monocytes of other lineages. We would have expected that if mature OC expressed significant amounts of CX3CR1 protein under these conditions, a large number of multinuclear osteoclasts would be labeled with the tdTomato reporter at 1 day after tamoxifen injection, which we did not see. At 5 days post-tamoxifen there were abundant tdTomato-positive large, multinucleated OC on bone in the primary spongiosa. Hence, similar to our in vitro results, our in vivo data argue that the Cx3cr1 promoter/enhancer sequences identifies OCP that rapidly (within 5 days) form mature OC in vivo.

The time of 5 days that it took for mature OC to form from OCP in vivo in CX3CR1CreER/Ai14 mice is similar to the time it takes for the most mature OCP to form OC in vitro (Figure 1) (2, 27). Hence, it appears that this time period is inherent for the maturation of OC from OCP and not a unique characteristic of in vitro culture systems.

It has been known for over 40 years that OCP can circulate and engraft into bones with a perturbed microenvironment (14). However, it has been unclear if circulating cells were a major component of the osteoclasts that form in bone under homeostatic conditions. Our parabiosis studies argue that under the conditions of these studies, production of OC from circulating precursors is a relatively rare event. Similar to our results, Boban et al. showed that during parabiosis between Col3.6GFP and Col2.3ΔTK mice, engraftment of OC between parabionts did not occur unless the mice were treated with ganciclovir (GCV), which killed osteoblast-lineage cells and “opened-up” the bone marrow microenvironment to engraftment (13). However, these studies used the Col 3.6 promoter to drive GFP expression in OC and it can be argued that this off-target expression of GFP might not produce levels of the fluorescent marker in OC that were intense enough to be detected easily by epifluorescence.

Kotani et al. also demonstrated minimal engraftment of circulating monocyte progenitors in the bone marrow (12) during normal homeostasis using CX3CR1-GFP mice to label cells. However, their approach also may have underrepresented the number of cells that migrate from the circulation to the bone and matured into OC. This is because our data and that of others (6, 7) demonstrate that the Cx3cr1 promoter, which they used to drive GFP expression, can be rapidly downregulated as OCP mature into OC.

In contrast, our studies utilized the strong Acp5 promoter/regulatory regions to drive high level tdTomato expression in OC as demonstrated in vitro and in vivo. In addition, to further enhance the sensitivity of our detection assay, we used an antibody to tdTomato but still failed to find significant engraftment of OCP between parabionts. Based on our results from 4 weeks of parabiosis and our finding in CX3CR1CreER/Ai14 mice that OCP differentiate into OC within 5 days, we conclude that circulating cells represent a minor source of OCP under the conditions of parabiosis that we studied.

There are several studies, which demonstrate that the bone marrow environment can be “opened” to engraftment by circulating OCP after various perturbations. In a seminal study Walker found that osteopetrosis, due to defective OC in mice, could be cured by parabiosis of an osteopetrotic mouse with a normal mouse (14). Similarly, Göthlin and Ericsson injected labeled cells into the blood of rats that had undergone a fracture and showed the incorporation of the labeled cells into OC in the resolving callus (11). Kotani et al. (12) found that there was good transfer of labeled circulating OCP into mature OC after stimulating bone resorption in mice by injecting them with RANKL while Charles et al. showed that circulating OCP could become OC in bone that was undergoing inflammation (5).

Our experiment in which FACS-purified GFP+ BM cells from CX3CR1-GFP/TRAP tdTomato mice were transferred into mice with a repairing femur fracture demonstrated that CX3CR1 marked BM cells, which when released into the circulation can become OC during fracture repair. These studies also confirmed the influence of environmental conditions on the ability of circulating OCP to engraft and differentiate into OC on bone in vivo. Finally, the failure of circulating CX3CR1+ OCP to engraft and incorporate into OC in the bones of mice that were not fractured further argue that during homeostasis the bone marrow is relatively protected from engraftment by circulating OCP.

Additional support for this hypothesis, comes from our previous studies of mice that had Cre recombinase “knocked into” the cathepsin K gene (28) and were crossed with Ai14 reporter mice (29). Using this mouse model as a source of OCP, we found that after a single injection of highly purified BM or spleen OCP from Cat-K-Cre/ -Ai14 mice, there was no engraftment of cells in the bone marrow or their maturation into OC in non-irradiated mice (29). In contrast, in irradiated mice (9 gray) there was significant engraftment of bone marrow or spleen cells, and these formed multinuclear mature OC that were TRAP+ in resorption lacuna at 15 days post-irradiation and transplant (29). Our results with parabiosis are consistent with our adoptive transfer studies as outlined above and those of others (10, 30) that required some perturbation of the bone microenvironment for engraftment and maturation of circulating OCP into mature OC to occur in bone.

However, our results are in contrast to those of Jacome-Galarza et al. who showed that in parabiosed animals after four-to-eight weeks, essentially all osteoclasts lining the bone surface expressed both YFP (host) and tdTomato (donor) reporters, and these cells persisted for at least 24 weeks after separation of the parabionts (15). Moreover, in their study they showed successful engraftment of Ly6C+ monocyte from Csf1ricre;Rosa26LSL-tdTomato mice into Csf1rcre;Rosa26LSL-YFP mice after adoptive transfer, without irradiating the recipient mice. Both we and Jacome-Galarza et al. used the identical anti-RFP antibody to increase tdTomato signal detection in frozen sections. Hence, we believe that our ability to detect engrafted cells between parabionts was similar to theirs. We are at a loss to fully explain the contradictory results between our studies. Given the long experience with adoptive transfer and the use of irradiation or other perturbation to allow engraftment, it was unexpected that Jacome-Galarza et al. would find significant bone marrow engraftment of circulating OCP in homeostatic conditions. As a possible explanation for the discrepancy between our results, we postulate that Jacome-Galarza et al. produced an inflammatory reaction by parabiosing mice with two different reporters. Stripeche et al. showed that fluorescent reporters like GFP can induce an immune response, which is stronger in BALB/c mice than in C57BL/6 (31). The study by Jacome-Galarza et al. did not report the background of the animals used, but two different reporters used in parabiosed animals might cause sufficient inflammatory conditions, which enhanced engraftment of osteoclast progenitors. Since in all our experiments we used C57BL/6 mice, which have lower immune responses to the reporter protein, we believe that the parabionts in our study more closely resemble the homeostatic state of an intact mouse. Our demonstration of high-level engraftment of cells from one parabiont to the other in the spleens of the mice and the general health of the animals during parabiosis, argues that we did not have an inflammatory reaction in our parabiosed animals, which destroyed the cells in bone from the other mouse and resulted in an absence of detectable OCP transfer between the parabionts. Our findings that iv injection of labeled OCP into mice with a repairing fracture (a state associated with inflammation (26)) produced engraftment and incorporation of labeled OCP into OC while injection of labeled OCP into intact mice did not, further argues that inflammation itself is not the reason for our failure to find engraftment and maturation of circulating OCP into OC in our homeostatic models.

In summary, our results show that CX3CR1 expressing cells are OCP, which downregulate expression of this gene when they differentiate into mature OC both in vitro and in vivo in homeostasis and during fracture repair in mice. Furthermore, our studies of TRAP tdTomato - WT parabiosed mice and our studies of adoptive transfer of circulating OCP during fracture repair argue that under homeostatic conditions in adult mice, the bone marrow is the principal repository of the OCP that form mature OC in the bone while when the bone marrow integrity is perturbed by fracture, circulating CX3CR1+ cells can become OC during fracture repair.

Key points.

OPC express CX3CR1 and in unperturbed conditions differentiate into osteoclasts

Contribution of circulating CX3CR1+ OCP to OC development is low during homeostasis

Mature OC can originate from circulating CX3CR1+ cells during fracture repair

Acknowledgements:

SN, ER, JK, SJ, and HLA performed experiments, compiled data and contributed to the writing of the manuscript, analyzed data. SN, HLA, SKL, IK and JL planned experiments, analyzed data, and edited the manuscript. Great thank to Nathaniel A. Dyment for allowing us use Axioscan imaging system.

Supported by: This work has been supported by The National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) R01 AR048714 to J.A.L and AR055607 and AR070813 to I.K.

Footnotes

Disclosures:

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References:

- 1.Lorenzo JA, Canalis E, and Raisz LG. 2008. Metabolic Bone Disease In Williams Text Book of Endocrinology. Kronenberg H, Melmed S, Polonsky KS, and Larsen PR, eds. Saunders-Elsevier, Philadelphia: 1269–1310. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacome-Galarza CE, Lee SK, Lorenzo JA, and Aguila HL. 2013. Identification, characterization, and isolation of a common progenitor for osteoclasts, macrophages, and dendritic cells from murine bone marrow and periphery. J Bone Miner Res 28: 1203–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker DG 1975. Bone resorption restored in osteopetrotic mice by transplants of normal bone marrow and spleen cells. Science 190: 784–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walker DG 1975. Spleen cells transmit osteopetrosis in mice. Science 190: 785–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charles JF, Hsu LY, Niemi EC, Weiss A, Aliprantis AO, and Nakamura MC. 2012. Inflammatory arthritis increases mouse osteoclast precursors with myeloid suppressor function. J Clin Invest. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koizumi K, Saitoh Y, Minami T, Takeno N, Tsuneyama K, Miyahara T, Nakayama T, Sakurai H, Takano Y, Nishimura M, Imai T, Yoshie O, and Saiki I. 2009. Role of CX3CL1/fractalkine in osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption. J Immunol 183: 7825–7831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoshino A, Ueha S, Hanada S, Imai T, Ito M, Yamamoto K, Matsushima K, Yamaguchi A, and Iimura T. 2013. Roles of chemokine receptor CX3CR1 in maintaining murine bone homeostasis through the regulation of both osteoblasts and osteoclasts. J Cell Sci 126: 1032–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Imai T, Hieshima K, Haskell C, Baba M, Nagira M, Nishimura M, Kakizaki M, Takagi S, Nomiyama H, Schall TJ, and Yoshie O. 1997. Identification and molecular characterization of fractalkine receptor CX3CR1, which mediates both leukocyte migration and adhesion. Cell 91: 521–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saitoh Y, Koizumi K, Sakurai H, Minami T, and Saiki I. 2007. RANKL-induced down-regulation of CX3CR1 via PI3K/Akt signaling pathway suppresses Fractalkine/CX3CL1-induced cellular responses in RAW264.7 cells. Biochem.Biophys.Res.Commun . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ibanez L, Abou-Ezzi G, Ciucci T, Amiot V, Belaid N, Obino D, Mansour A, Rouleau M, Wakkach A, and Blin-Wakkach C. 2016. Inflammatory Osteoclasts Prime TNFalpha-Producing CD4+ T Cells and Express CX3 CR1. J Bone Miner Res 31: 1899–1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gothlin G, and Ericsson JL. 1973. On the histogenesis of the cells in fracture callus. Electron microscopic autoradiographic observations in parabiotic rats and studies on labeled monocytes. Virchows Arch.B Cell Pathol. 12: 318–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kotani M, Kikuta J, Klauschen F, Chino T, Kobayashi Y, Yasuda H, Tamai K, Miyawaki A, Kanagawa O, Tomura M, and Ishii M. 2013. Systemic circulation and bone recruitment of osteoclast precursors tracked by using fluorescent imaging techniques. J Immunol 190: 605–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boban I, Jacquin C, Prior K, Barisic-Dujmovic T, Maye P, Clark SH, and Aguila HL. 2006. The 3.6 kb DNA fragment from the rat Col1a1 gene promoter drives the expression of genes in both osteoblast and osteoclast lineage cells. Bone 39: 1302–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walker DG 1973. Osteopetrosis cured by temporary parabiosis. Science. 180: 875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacome-Galarza CE, Percin GI, Muller JT, Mass E, Lazarov T, Eitler J, Rauner M, Yadav VK, Crozet L, Bohm M, Loyher P-L, Karsenty G, Waskow C, and Geissmann F. 2019. Developmental origin, functional maintenance and genetic rescue of osteoclasts. Nature 568: 541–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yona S, Kim K-W, Wolf Y, Mildner A, Varol D, Breker M, Strauss-Ayali D, Viukov S, Guilliams M, Misharin A, Hume David A., Perlman H, Malissen B, Zelzer E, and Jung S. 2013. Fate Mapping Reveals Origins and Dynamics of Monocytes and Tissue Macrophages under Homeostasis. Immunity 38: 79–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kikuta J, Wada Y, Kowada T, Wang Z, Sun-Wada GH, Nishiyama I, Mizukami S, Maiya N, Yasuda H, Kumanogoh A, Kikuchi K, Germain RN, and Ishii M. 2013. Dynamic visualization of RANKL and Th17-mediated osteoclast function. J Clin Invest. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jung S, Aliberti J, Graemmel P, Sunshine MJ, Kreutzberg GW, Sher A, and Littman DR. 2000. Analysis of fractalkine receptor CX(3)CR1 function by targeted deletion and green fluorescent protein reporter gene insertion. Mol.Cell Biol. 20: 4106–4114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aguila HL, Mun SH, Kalinowski J, Adams DJ, Lorenzo JA, and Lee SK. 2012. Osteoblast-specific overexpression of human interleukin-7 rescues the bone mass phenotype of interleukin-7-deficient female mice. J Bone Miner Res 27: 1030–1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee SK, Kalinowski J, Jastrzebski S, and Lorenzo JA. 2002. 1,25 (OH)(2) Vitamin D(3)-Stimulated Osteoclast Formation in Spleen-Osteoblast Cocultures Is Mediated in Part by Enhanced IL-1alpha and Receptor Activator of NF-kappaB Ligand Production in Osteoblasts. J Immunol. 169: 2374–2380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee SK, and Lorenzo JA. 1999. Parathyroid hormone stimulates TRANCE and inhibits osteoprotegerin messenger ribonucleic acid expression in murine bone marrow cultures: correlation with osteoclast-like cell formation. Endocrinology 140: 3552–3561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Donskoy E, and Goldschneider I. 1992. Thymocytopoiesis is maintained by blood-borne precursors throughout postnatal life. A study in parabiotic mice. The Journal of Immunology 148: 1604–1612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bonnarens F, and Einhorn TA. 1984. Production of a standard closed fracture in laboratory animal bone. J Orthop Res 2: 97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoshino A, Iimura T, Ueha S, Hanada S, Maruoka Y, Mayahara M, Suzuki K, Imai T, Ito M, Manome Y, Yasuhara M, Kirino T, Yamaguchi A, Matsuhsima K, and Yamamoto K. 2010. Deficiency of chemokine receptor CCR1 causes osteopenia due to impaired functions of osteoclasts and osteoblasts. J Biol Chem 22: 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han KH, Ryu JW, Lim KE, Lee SH, Kim Y, Hwang CS, Choi JY, and Han KO. 2014. Vascular expression of the chemokine CX3CL1 promotes osteoclast recruitment and exacerbates bone resorption in an irradiated murine model. Bone 61: 91–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loi F, Cordova LA, Pajarinen J, Lin TH, Yao Z, and Goodman SB. 2016. Inflammation, fracture and bone repair. Bone 86: 119–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacquin C, Gran DE, Lee SK, Lorenzo JA, and Aguila HL. 2006. Identification of multiple osteoclast precursor populations in murine bone marrow. J.Bone Miner.Res. 21: 67–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakamura T, Imai Y, Matsumoto T, Sato S, Takeuchi K, Igarashi K, Harada Y, Azuma Y, Krust A, Yamamoto Y, Nishina H, Takeda S, Takayanagi H, Metzger D, Kanno J, Takaoka K, Martin TJ, Chambon P, and Kato S. 2007. Estrogen Prevents Bone Loss via Estrogen Receptor α and Induction of Fas Ligand in Osteoclasts. Cell 130: 811–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacome-Galarza CE 2013. Phenotypic Characterization of Peripheral Osteoclast Precursors their Lineage Relation to Macrophages and Dendritic Cells and their Population Dynamics Influenced by Parathyroid Hormone and Inflammatory Signals. Doctoral Thesis. University of Connecticut School of Medicine and DentistryFollow, https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/13/. 152. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matheu MP, Cahalan MD, and Parker I. 2011. General approach to adoptive transfer and cell labeling for immunoimaging. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2011: pdb prot5565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stripecke R, del Carmen Villacres M, Skelton DC, Satake N, Halene S, and Kohn DB. 1999. Immune response to green fluorescent protein: implications for gene therapy. Gene Therapy 6: 1305–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]