Abstract

Background

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension most commonly affects women of childbearing age and usually causes headache and intermittent visual obscurations. Some patients suffer permanent visual loss. The major modifiable risk factor associated with IIH is obesity. Scotland has one of the poorest records for obesity in the western world, with a prevalence in 2016 of 29% in the adult population. We aimed to establish the incidence of idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) in Scotland.

Methods

All new cases of IIH seen in Scotland were collected over a 1-year period. Cases were reported by ophthalmologists through the Scottish Ophthalmic Surveillance Unit (SOSU) and by neurologists directly to the investigators using encrypted NHS emails. An open dialogue was maintained between the investigators and specialist neuro-ophthalmology clinics throughout the year to minimise the risk of under-reporting. Cases were defined using the Modified Dandy Diagnostic Criteria.

Results

One hundred and forty-four confirmed cases of IIH were reported. One hundred and ten out of 144 patients were female and aged 15–44. The mean BMI in this group was 38.9.

Conclusions

The incidence of IIH in Scotland is at least 2.65/100,000. This figure rises to 37.9/100,000 in obese females aged 15–44. This figure is higher than previously published and is probably a result of increasing levels of obesity across the nation. The significant morbidity caused by IIH, in this young population raises the question of whether enough is being done to prevent and treat Scotland’s obesity crisis.

Subject terms: Epidemiology, Risk factors

Introduction

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) is a syndrome characterised by increased intracranial pressure in the absence of clinical, laboratory and radiological evidence of a space occupying a lesion or hydrocephalus. Its aetiology is unknown, however, it classically affects young women of childbearing age [1–3]. Diagnosis is made based on the Modified Dandy Criteria [4], and the clinical features, risk factors, natural history and long-term follow-up are well described in the literature [5]. Previous estimates of the annual incidence of IIH vary from 0.03 to 2.4 per 100,000, however, this varies depending on ethnicity, geographical location, age and sex (see Table 1). IIH is more common in women and is predominantly a disease affecting younger adults. The estimated incidence in women aged 15–44 years is 3.5/100,000. The most common symptoms of IIH are headache and transient visual loss. In the majority of cases, IIH is treatable, without impairment of vision in the long term. However, a significant group of patients exist, who develop permanent visual loss, which can be rapidly progressive and devastating [6].

Table 1.

Published incidence of IIH in the literature

| Year | Location | Author | Study design | Duration of data collection | Population size | IIH incidence per 100,000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1984–1985 | Iowa, USA | Durcan [1] | ‘Survey of specialists’ | 1 year | 2,913,808 | 0.9 |

| 1984–1985 | Louisiana, USA | Durcan [1] | ‘Survey of specialists’ | 1 year | 4,480,681 | 1.07 |

| 1982–1989 | Benghazi, Libya | Radhakrishnan [2] | ‘Epidemiological survey’ | 7 years | 519,000 | 2.2 |

| 1993 | Hokkaido, Japan | Yabe [20] | Retrospective | 1 year | 5,780,000 | 0.03 |

| 1991–1995 | Belfast, N Ireland | Craig [3] | Retrospective, single centre | 5 years | 1,640,000 | 0.6 |

| 1998–1999 | Israel | Kesler [21] | Prospective, multicentre | 2 years | 5,970,000 | 0.75 |

| 1990–1999 | Parma, Italy | Carta [22] | Retrospective, multicentre | 10 years | ~200,000 | 0.28 |

| 2007–2008 | Sheffield, England | Raoof [23] | Retrospective, single centre | 2 years | ~500,000 | 1.56 |

| 2007–2014 | Northern Ireland | McCluskey [24] | Retrospective, single centre | 7 years | 182,518 | 2.36 |

| 2006–2013 | Sweden | Sundholm [25] | Retrospective, multicentre | 8 years | Not given | 0.65 |

| 2002–2014 | Olmsted County, Minnesota, USA | Kilgore [26] | Retrospective, multicentre | 12 years | ~140,000 | 1.8 |

| 2013–2014 | Fife, Scotland | Goudie [13] | Prospective, single centre | 1 year | 365,000 | 3.56 |

| 2016–2017 | Scotland | Present study | Prospective, multicentre | 1 year | 5,424,800 | 2.65 |

The major modifiable risk factor associated with IIH is body mass [7–10]. The majority of patients with IIH are obese (defined as having a body mass index (BMI) of over 30) with an additional link to recent weight gain [11].

Scotland has one of the poorest records for obesity in the western world, with a prevalence in 2016 of 29% in the adult population [12]. We have previously performed a prospective incidence study of IIH amongst the entire population of Fife, an area on the east coast of Scotland with a population of 365,000, and found the incidence to be 3.56/100,000 [13]. This is higher than previous studies reporting from similar populations. The prevalence of obesity in Fife is only slightly higher than the national average and did not account for such a high incidence. As a consequence, we decided to undertake a nationwide incidence study in Scotland over a period of 1 year to see if other regions in Scotland reflected the findings in Fife, as well as to describe the demographics of those affected by IIH.

Methods

All new cases of IIH seen by ophthalmologists or neurologists in Scotland were collected prospectively between 1 November 2016 and 31 October 2017. Cases seen by ophthalmologists were reported via the Scottish Ophthalmic Surveillance Unit (SOSU). SOSU is run by the Royal College of Ophthalmologists, alongside the British Ophthalmic Surveillance Unit (BOSU), to assist with the epidemiological study of rare ocular disorders. It is an active prospective case ascertainment system that engages with all consultant or associate specialist ophthalmologists in Scotland (122 individuals were on the database at the time of data collection) to identify cases of rare eye diseases to provide meaningful data for epidemiological analysis. Each month, every ophthalmologist in Scotland was posted a SOSU reporting card asking if they had managed any new cases of IIH in their practice. When a case was reported, a questionnaire was sent to the notifying ophthalmologist asking for demographic and clinical data on the case, including BMI, medications and postcode. If BMI was not known, we asked clinicians to comment on whether they considered the patient to be clinically obese. If the questionnaire was not returned, a reminder letter was sent to increase the response rate. Ophthalmologists were also sent a 6-month follow-up questionnaire for each case they reported. An identical system was developed with all neurology departments in Scotland. Neurologists were contacted by a secure NHS email, and when a case was reported, an abbreviated questionnaire was requesting patient age, sex and postcode.

To maximise case reporting from higher-volume specialist neuro-ophthalmologists, there was a more open dialogue with the investigators, allowing cases to be reported by email, rather than being restricted to the SOSU reporting cards.

Cases of IIH were defined using the the Modified Dandy Criteria, namely:

If symptoms and/or signs are present, they may only reflect those of generalised intracranial hypertension or papilloedema

Intracranial pressure, as measured in the lateral decubitus position, is elevated

The composition of the cerebrospinal fluid is normal

There is no evidence of hydrocephalus, mass, structural or vascular lesion

No other cause of intracranial hypertension has been identified

Ethics advice was sought from the South East Scotland Research and Ethics Service and approval was granted through the Public Benefit and Privacy Panel for Health and Social Care in Scotland.

Population obesity data were taken from the Scottish Health Survey 2016 [12]. Data on social deprivation were analysed depending on postcode using the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation, also from the Scottish Health Survey 2016. The incidence of IIH was calculated using a Scottish population of 5,424,800 [14].

Results

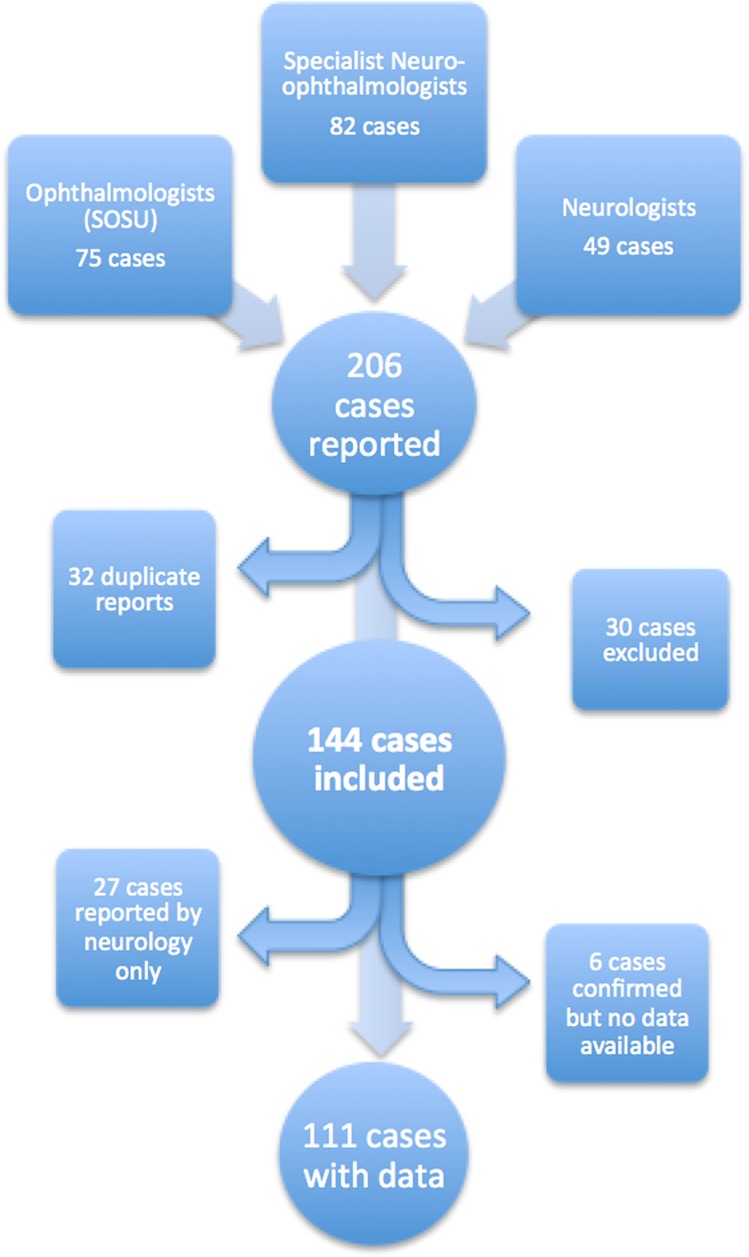

Two hundred and six cases were reported to the investigators during the 12-month study period. Thirty of these were excluded, whilst 32 cases were reported by more than one source, leaving a total of 144 cases. The breakdown of these case reports is shown in Fig. 1. Thirteen cases were incorrectly reported following errors with the SOSU reporting system and so were excluded. Other reasons for exclusion were duplicate reports from the same source (8), cases reported outside the study period (4) and incorrect diagnosis (5). Twenty seven of these cases were reported by a neurologist only and therefore only age, sex and postcode were collected. Questionnaires were sent for the remaining 117 cases and 111 responses were received, 106 of which included usable information.

Fig. 1.

Source of the reported new cases of IIH

The SOSU card response rate from ophthalmologists each month was 68%, whilst the response rate from neurologists (via email) was 30%.

Patient demographics

The mean patient age was 27.7 years with a range of 6–63 years. One hundred and ten patients were female and aged 15–44. Eleven patients were under 15 (5 male and 6 female) and 12 patients were over 44 (2 male and 10 female) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient demographics showing obesity and BMI data

| Number (n = 141) | Patients considered to be clinically obese | Mean BMI (range) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female <15 | 6 | 4/4 (100%) | 28.5 (1 reported) |

| Male <15 | 5 | 1/5 (20%) | 20.99 (16.64–16.28) |

| Female 15–44 | 110 | 73/80 (91%) | 39.8 (17.5–107.3) |

| Male 15–44 | 8 | 5/6 (83%) | 39.0 (28.7–47.9) |

| Female >44 | 10 | 5/7 (71%) | 39.4 (24.2–56.5) |

| Male >44 | 2 | 0/1 (0%) | n/a |

Obesity

Information regarding obesity was reported for 103 patients, whilst BMI was available for 75. Seventy three out of 80 (91%) females aged 15–44 were considered to be obese. BMIs were reported for 49 patients in this group with a mean of 39.8 (range 17.5–107.3). Forty three out of 49 had a BMI >29.9, whilst 47 out of 49 had a BMI of >24.9. Five out of 9 children, 5 out of 7 men and 5 out of 7 women over 44 were considered to be obese.

Social deprivation

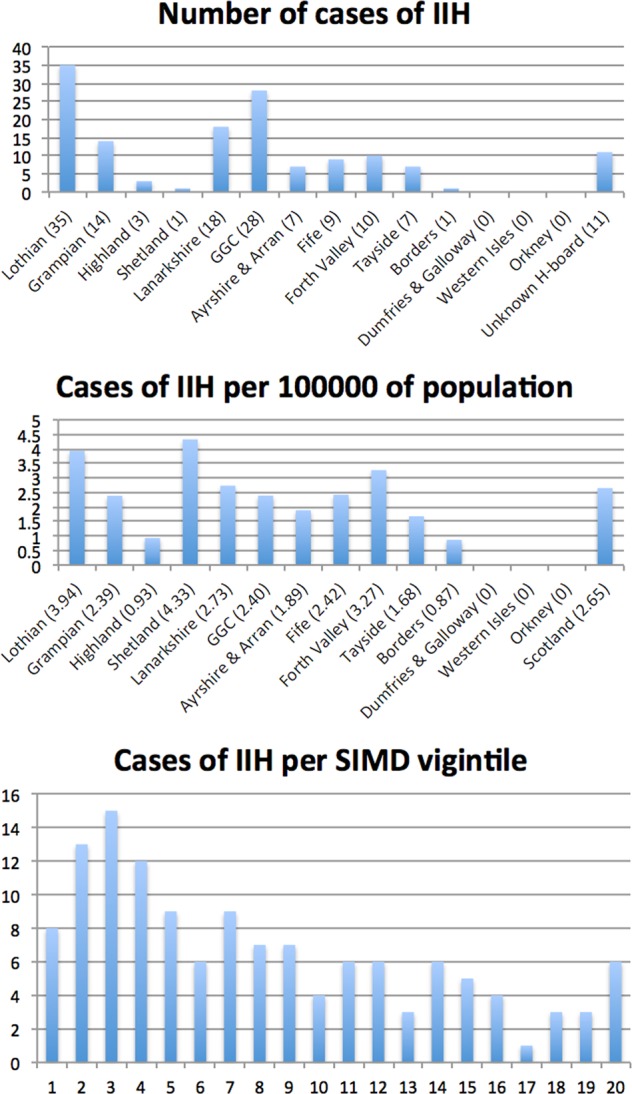

The distribution of patients by the NHS Board and SIMD data is shown in Fig. 2. Vignitile 1 includes the most deprived 5% of the population, whilst vignitile 20 includes the least deprived 5%. When SIMD data were corrected for obesity, our data did not demonstrate an independent link between social deprivation and IIH.

Fig. 2.

Number of cases of IIH shown by the healthboard, per 100,000 of the population and per SIMD viginitle. Vigintile 1 is the most deprived 5% of the population

Medication use

Nine patients were taking the oral contraceptive pill, whilst six others were reported as using alternative forms of long-term contraception (three intrauterine devices, three contraceptive implants). Five patients were pregnant at the time of diagnosis. Six patients reported current or recent use of corticosteroids (one of these cases was thought to be secondary to the use of fludrocortisone) and four patients were taking tetracyclines. One patient developed IIH following an infusion of intravenous immunoglobulin to treat chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. Sixty nine out of 111 were taking no medications prior to their diagnosis.

One hundred and seven out of 111 patients had bilateral optic disc swelling, two patients had unilateral swelling and two patients had normal optic disc appearances. Further clinical information and data from the 6-month follow-up questionnaire (which was obtained for 103 cases) will be reported in a subsequent article.

Discussion

This prospective study estimates that the incidence of IIH in Scotland is 2.65/100,000. In females aged 15–44, the incidence is 10.7/100,000 and in obese females aged 15–44, the incidence is 37.9/100,000. These figures are significantly higher than previously published, which may reflect the levels of obesity in Scotland. IIH is known to cause significant morbidity, via headache, and in some cases, irreversible loss of vision. Headache is associated with low mood, and along with visual loss, leads to significant psychological, social and economic consequences, magnified by the young population that is affected by this condition [15].

A recent meta-analysis [16] and a systematic review of epidemiological studies in IIH highlights significant variability in the incidence of IIH (see Table 1) based on population characteristics, particularly obesity. They describe a paucity in large, high- quality epidemiological studies looking at IIH. Very few of the studies they looked at were prospective and when compared with all large studies (population size over 1,000,000), our data for the Scottish population estimate a significantly higher incidence.

The demographics of our study were consistent with the literature, with the majority of cases affecting women, aged 15–44. Mean BMI of 39.8 is also consistent with previous studies. BMI was not recorded for 36 out of 111 cases (33%). The recently published consensus guidelines on IIH identify weight loss as the only disease-modifying therapy in typical IIH, advising that BMI should be recorded at all follow-up appointments. Patients with IIH often struggle to lose weight. Regular BMI monitoring in the clinic may serve as a reminder and promote discussion about the importance of weight loss in managing IIH, taking emphasis away from the medications that often demand much attention during a consultation, but do not in fact modify the course of the disease.

These data add further weight to evidence from many other medical specialties that Scotland’s obesity epidemic is causing significant morbidity, and raises the question about whether enough is being done at a public health level to reverse the trend.

Our study is the first to show that IIH is most prevalent in areas of social deprivation. It is likely that higher levels of obesity in these areas explain this link. Indeed, when we analysed our results, corrected for obesity, social deprivation was not an independent risk factor for IIH. It is interesting to note that the number of cases reported drop off in the two most deprived vigintiles. This almost certainly reflects under-reporting due to lack of engagement with or lack of access to health services in these populations [17].

Whilst the pathogenesis is not fully understood, it is thought that ‘prepubertal’ IIH and ‘secondary’ IIH, linked to medication use, are distinct conditions from typical ‘weight-related’ IIH [15]. Eleven cases of IIH were reported in patients under 15 years old (male:female = 6:5), although we did not specifically ask if these individuals were prepubertal. The male-to-female ratio in prepubertal IIH is nearly one, a condition that may not be associated with weight. Of the nine reported cases that included information about obesity, five (55%) were considered to be obese.

The number of cases in our study is not sufficient to reach a conclusion on the role that individual medications play in the pathogenesis of IIH. Nine out of 111 patients (8.1%) were taking the oral contraceptive pill at the time of diagnosis. There is conflicting evidence linking oral contraception and IIH. Recent consensus suggests that similar to pregnancy, it is likely that this relationship reflects the typical age and gender profile of an IIH patient rather than the medication itself [1, 7, 8]. Five patients (4.5%) were pregnant at the time of diagnosis. As with oral contraceptive use, a seemingly high prevalence of IIH during pregnancy is thought to reflect a young, female demographic affected. It is likely that patients diagnosed during pregnancy likely had an onset of IIH prior to getting pregnant. Our experience suggests that IIH often stabilises during pregnancy, despite stopping treatment [18].

Of the six patients that reported current or recent use of corticosteroids, two were male, and one female was over 44. Only one of these patients was obese (female aged 15–44). Secondary IIH has been reported with corticosteroid excess and also with deficiency (such as in Addison’s disease), although this link is not established [15]. All four patients that were taking tetracylines were females, aged between 15 and 44, who were obese. IIH has been reported in patients taking tetracycline antibiotics in many case reports and in one case–control study; however, other prospective studies have failed to confirm this link [1, 8, 11]. One patient developed IIH following an infusion of intravenous immunoglobulin to treat chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. If these cases are truly linked to medication, then they should be considered as secondary IIH, which should be considered differently to weight-associated IIH.

It must be true that the true incidence of any condition, with specific diagnostic criteria, that is the subject of a study that relies on case reporting, will be equal to or higher than the reported figure. The main reason for this is under-reporting. Response rates from ophthalmologists and neurologists were similar to previous BOSU/SOSU studies and other electronic case-reporting studies, respectively. By receiving case reports from multiple sources (neurology, ophthalmology and specialist neuro-ophthalmologists), we attempted to minimise under-reporting. Our data show a significant variation in the cases reported, depending on the NHS board across Scotland. In smaller NHS boards, the population is such that one or two new cases will significantly change the incidence per 100,000, and so a study period of 1 year does not accurately reflect the incidence. The variation seen between the larger health boards (most noticeable when comparing Lothian and Tayside) probably reflects under-reporting, where busy clinicians fail to report cases they have seen.

The Modified Dandy Criteria were used to define the diagnosis of IIH in our study. In reality, the diagnosis is often not straightforward, which is reflected in recently published consensus guidelines [15]. This is further highlighted by Fisayo et al. [19], who suggest that IIH is often over-diagnosed, despite the Modified Dandy Criteria. Their retrospective study showed that a significant proportion of patients initially diagnosed with IIH by non-neuro-ophthalmologists (including ophthalmologists, neurologists and optometrists) did not have IIH, according to the neuro-ophthalmologist. They cited that the most common source of error was inaccurate assessment of the optic nerve head (usually anomalous optic nerves being misinterpreted as papilloedema). Mild optic disc swelling from papilloedema can be a subtle sign and an asymptomatic patient, with normal imaging, can be observed by experienced clinicians, rather than proceeding with an invasive lumbar puncture.

Our study design was such that false positives were unlikely. Eighty two out of 144 new cases were reported by specialist neuro-ophthalmologists. Six-month follow-up data were available for 103 cases, none of whom had their diagnosis revised. We are unable to comment on the diagnostic accuracy of the 27 cases reported by neurology only, however, it is likely that most (if not all) of these will have also been seen by an ophthalmologist, with the fact that they were reported by neurology only, reflecting under-reporting by ophthalmologists.

Furthermore, in certain cases, measuring opening pressure by lumber puncture can be unreliable. It is important to follow a standard protocol when obtaining an opening pressure, to avoid inaccurate results. LP can be more difficult in obese patients, where bony landmarks are less obvious; anxiety, leading to tense muscles, can alter true CSF pressure. If LP opening pressure does not fit the clinical picture, it should be interpreted with caution. For clarity and consistency, an elevated opening pressure on LP was an essential part of the inclusion criteria in our study, which may have resulted in under-reporting caused by false negatives.

Although our figure of 2.65 cases of IIH for 100,000 of the population is almost certainly an underestimate, it is clear that the incidence is increasing, alongside the increasing levels of obesity throughout Scotland. We have shown that the incidence of IIH in Scotland is at least 2.65/100,000, which increases to 40 per 100,000 in obese young women. Frustratingly, for most of the people, IIH should be preventable. Our study is the latest in a long line, showing increased morbidity caused by Scotland’s obesity crisis and raises questions about whether we, as a society, are doing enough to prevent and treat this modern epidemic.

Summary

What was known before

IIH causes significant morbidity in young, female patients. Obesity is the major modifiable risk factor for developing IIH. The levels of obesity in Scotland are higher than ever before.

What this study adds

The incidence of IIH in Scotland is higher than previously recorded, which is almost certainly a consequence of the increasing levels of obesity.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was supported by the Scottish Ophthalmic Surveillance Unit, through the Ross Foundation SOSU study bursary.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Durcan FJ, Corbett JJ, Wall M. The incidence of pseudotumour cerebri. Population studies in Iowa and Louisiana. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:875–7. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1988.00520320065016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Radhakrishnan K, Ahlskog JE, Cross SA, Kurland LT, O’Fallon WM. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumour cerebri): descriptive epidemiology in Rochester, Minn. 1976 to 1990. Arch Neurol. 1993;50:78–80. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1993.00540010072020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Craig JJ, Mulholland DA, Gibson JM. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension; incidence, presenting features and outcome in Northern Ireland (1991–5) Ulst Med J. 2001;70:31–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman DI, Jacobson DM. Diagnostic criteria for idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurology. 2002;59:1492–5. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000029570.69134.1B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dhungana S, Sharrack B, Woodroofe N. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Acta Neurol Scand. 2010;121:71–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2009.01172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Best J, Silvestri GBJ, Foot B, Atchison J. The Incidence of Blindness Due to Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension in the UK. Open Ophthalmol J. 2013;7:26–29. doi: 10.2174/1874364101307010026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ireland B, Corbett JJ, Wallace RB. The search for causes of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. A preliminary case-control study. Arch Neurol. 1990;47:315–20. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1990.00530030091021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giuseffi V, Wall M, Siegel PZ, Rojas PB. Symptoms and disease associations in idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri): a case–control study. Neurology. 1991;41:239–44. doi: 10.1212/WNL.41.2_Part_1.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rowe FJ, Sarkies NJ. The relationship between obesity and idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23:54–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galvin JA, Van Stavern GP. Clinical characterization of idiopathic intracranial hypertension at Detroit Medical Centre. J Neurol Sci. 2004;223:157–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daniels AB, Liu GT, Volpe NJ, Galetta SL, Moster ML, Newman NJ, et al. Profiles of obesity, weight gain, and quality of life in idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri). Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:635–41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.The Scottish Government. Scottish Health Survey 2016. www.gov.scot/topics/statistics/browse/health/trendobesity. Accessed 25 Jun 2018.

- 13.Goudie C, Burr J, Blaikie A. Incidence of idiopathic intracranial hypertension in Fife. Scott Med J. 2018:36933018809727. 10.1177/0036933018809727. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.National Records of Scotland 2018. https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/news/2018/scotlands-population-2017. Accessed 29 Sep 2018.

- 15.Mollan SP, Davies B, Silver NC, Shaw S, Mallucci CL, Wakerley BR, et al. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: consensus guidelines on management. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018;89:1088–100. 10.1136/jnnp-2017-317440. Epub 2018 Jun 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.McCluskey G, Doherty-Allan R, McCarron P, Loftus AM, McCarron LV, Mulholland D, et al. Meta-analysis and systematic review of population-based epidemiological studies in idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Eur J Neurol. 2018;25:1218–27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Hutt P, Gilmour S. Tackling inequalities in general practice. The King’s Fund. 2010. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_document/health-inequalities-general-practice-gp-inquiry-research-paper-mar11.pdf. Accessed 28 Sep 2018.

- 18.Huang X, Buchan D, Shah P. PO064 Idiopathic intracranial hypertension, pregnancy and acetazolamide. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88:A28. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2017-ABN.96. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fiyaso A, Bruce BB, Newman NJ, Biousse V. Overdiagnosis of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurology. 2016;86:341–50. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yabe I, Moriwaka F, Notoya A, Ohtaki M, Tashiro K. Incidence of idiopathic intracranial hypertension in Hokkaido, the northernmost island of Japan. J Neurol. 2000;247:474–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Kesler A, Gadoth N. Epidemiology of idiopathic intracranial hypertension in Israel. J Neuroophthalmol. 2001;21:12–14. doi: 10.1097/00041327-200103000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carta A, Bertuzzi F, Cologno D, Giorgi C, Montanari E, Tedesco S. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri): descriptive epidemiology, clinical features, and visual outcome in Parma, Italy, 1990 to 1999. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2004;14:48–54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Raoof N, Sharrack B, Pepper IM, Hickman SJ. The incidence and prevalence of idiopathic intracranial hypertension in Sheffield, UK. Eur J Neurol. 2011;18:1266–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCluskey G, Mulholland DA, McCarron P, McCarron MO. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension in the northwest of Northern Ireland: epidemiology and clinical management. Neuroepidemiology. 2015;45:34–39. doi: 10.1159/000435919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sundholm A, Burkill S, Sveinsson S, Piehl F, Bhamanyar S, Nilsson Remahl A. Population-based incidence and clinical characteristics of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Acta Neurol Scand. 2017;136:427–33. doi: 10.1111/ane.12742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kilgore KP, Lee MS, Leavitt JA, Mokri B, Hodge DO, Frank RD, et al. Re-evaluating the incidence of idiopathic intracranial hypertension in an era of increasing obesity. Ophthalmology. 2017;124:697–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]