Abstract

Cereal endosperm is a short-lived tissue adapted for nutrient storage, containing specialized organelles, such as protein bodies (PBs) and protein storage vacuoles (PSVs), for the accumulation of storage proteins. During development, protein trafficking and storage require an extensive reorganization of the endomembrane system. Consequently, endomembrane-modifying proteins will influence the final grain quality and yield. However, little is known about the molecular mechanism underlying endomembrane system remodeling during barley grain development. By using label-free quantitative proteomics profiling, we quantified 1,822 proteins across developing barley grains. Based on proteome annotation and a homology search, 94 proteins associated with the endomembrane system were identified that exhibited significant changes in abundance during grain development. Clustering analysis allowed characterization of three different development phases; notably, integration of proteomics data with in situ subcellular microscopic analyses showed a high abundance of cytoskeleton proteins associated with acidified PBs at the early development stages. Moreover, endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT)-related proteins and their transcripts are most abundant at early and mid-development. Specifically, multivesicular bodies (MVBs), and the ESCRT-III HvSNF7 proteins are associated with PBs during barley endosperm development. Together our data identified promising targets to be genetically engineered to modulate seed storage protein accumulation that have a growing role in health and nutritional issues.

Subject terms: Protein transport, Proteomics

Introduction

After differentiation, fully developed cereal endosperm makes up to 75% of the grain weight and covers four major cell types: aleurone, starchy endosperm, transfer cells, and the cells of the embryo surrounding region1. The starchy endosperm thereby is characterized as a storage site, accumulating starch and seed storage proteins (SSPs)2. The aleurone layer plays essential roles during seed germination and mobilizes starch and SSP reserves in the starchy endosperm by releasing hydrolytic enzymes that are responsible for the degradation of stored nutrients in the endosperm2. Contrary to the persistent endosperm of cereals, the cellular endosperm of Arabidopsis thaliana (A. thaliana) supports the developing and growing embryo, resulting in a gradually depleted endosperm as the embryo grows. Finally, the massive A. thaliana embryo is only accompanied by a single peripheral layer, the aleurone layer, in mature seeds2. Consequently, A. thaliana cannot to be used as a model system to study the endomembrane system in grain endosperm.

In cereals, SSPs, which account for more than 50% of the grain protein content3,4, accumulate in the outer layer of the endosperm, in the subaleurone, and in the starchy endosperm, the latter in parallel with starch granules5. In barley, for instance, globulins and prolamins comprise the major endosperm SSPs6.

The SSP trafficking routes depend on the cereal species, endosperm layer and development stage7–9. SSPs are produced by the secretory pathway and reach their final destinations by two main routes: soluble albumins and globulins pass the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi to travel to protein storage vacuoles (PSVs); and most prolamins are finally deposited in specific, ER-derived protein bodies (PBs) or/and in PSVs. Along with these main routes, other organelles are proposed to be involved in the SSP trafficking in cereal endosperm, e.g., multivesicular bodies (MVBs), precursor-accumulating (PAC) vesicles and/or dense vesicles (DVs)9.

Depending on the protein trafficking, PB composition is affected, thereby influencing the qualitative output. For instance, the SSP composition defines the malting purposes, most specifically for the brewing industry10. Thus, endomembrane-modifying proteins within the endomembrane system will have an influence on the final grain quality/yield and recombinant protein production.

Barley (Hordeum vulgare) holds the fourth-most important cereal in terms of food production after maize, wheat, and rice11. Microscopic analyses revealed that spherical PSVs, which are stable in the aleurone during development, underwent a dynamic rearrangement including fusion, rupture and degeneration in the subaleurone and starchy endosperm of barley12–14. Between 8 and 12 days after pollination (DAP), PSVs reduced their size and even degenerated in the starchy endosperm13. Simultaneously, PBs were found in distinct compartments in the subaleurone but also within the vacuoles, where fusion events of PBs were observed by live cell imaging13. In the starchy endosperm, PBs were tightly enclosed by vacuoles that finally degenerated and released the PBs13. Recent bioinformatic, proteomic and RT-qPCR analyses shed the first light on proteins possibly involved in the rearrangement of the endomembrane system in barley endosperm12,15,16: Endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRT)-III proteins were identified by a bioinformatic assay12 and localization studies of recombinantly expressed ESCRT-III components HvSNF7a, HvVPS24 and HvVPS60a in barley revealed different localization of these proteins within the endosperm12. It was further suggested that cell layer–specific protein deposition or trafficking and remodeling of the endomembrane system in the endosperm has an impact on the steady-state association of ESCRT-III12. Additionally, the ER was identified to be most abundant in the starchy endosperm and ER rearrangements were characterized, including re-localization of HvPDIL1-1 during development15.

This work aimed to temporally map in situ the endomembrane system during barley endosperm development, using integrative cell biology experimental approaches. Label-free proteomics approaches of four different stages of grain development allowed the quantification of 1,822 proteins. Among these, 94 proteins could be associated with the endomembrane system. We identified cytoskeleton members, ESCRT proteins, and MVBs as putative key players for protein sorting into PBs during barley endosperm development. More specifically, seven out of eight proteins related to the ESCRT machinery showed specific expression patterns and transcript abundances associated with early and mid-development. In this context, confocal and transmission electron microscopy analyses located HvSNF7 and MVBs at the periphery of PBs and later within PBs, playing a putative role in protein sorting to PBs at mid-development. These results pave the way to exploit specifically the function of the endomembrane system to modulate SSP accumulation and/or to improve the production of recombinant proteins.

Materials and Methods

Plant material and growth conditions

Barley (H. vulgare L.) wild-type variety Golden Promise (GP) and transgenic lines (TIP (Tonoplast intrinsic protein)3-GFP, p6U::SNF7.1-mEosFP) were cultivated as described in17 and in the supplementary material. In detail, caryopses were harvested at different stages of grain development including 6–8, 10, 12–18 and ≥20 days after pollination (DAP) (designated as 6, 10, 12 and ≥20 DAP) of three biological replicates.

Data processing and protein identification

Sample preparation for proteomics analyses and Mass spectrometry (MS) was performed as previously described in16 and in the supplementary material. Raw files were processed with MaxQuant 1.5 (http://www.maxquant.org) and the Andromeda search algorithm18–20 on the barley UniProt database (http://uniprot.org). Peptide identification was performed as previously described16. Label-free quantification was done at the MS1 level with at least two peptides per protein. PTXQC was used to assess data quality and statistical analysis was performed with Perseus 1.5 software21,22. Protein annotation was performed with the MERCATOR tool (http://mapman.gabipd.org/de)23. Unknown proteins were identified by using BLAST at the UniProt homepage searching for the most identical cereal protein. Proteins were classified to “compartment-specific proteins” (functional associated with a specific subcellular endomembrane pathway or organelle), and as “trafficking regulators” (functional associated with several organelles) based on published data. In the final dataset, representative proteins were quantified in at least 9 of the 12 samples analyzed. Data were first Log2 transformed prior Z-scores (zero mean, unit variance) and were finally used to calculate the relative protein abundance. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Student’s t-tests were performed with Perseus 1.5 software. Cluster analysis was performed with fuzzy-c means algorithm implemented in GProX24. Generation of protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks was conducted via the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING) database for known and predicted protein-protein interactions (http://string-db.org/) with default parameters25. The MS proteomic data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium26 via the PRIDE (Vizcano et al., 2016) partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD009722.

Cloning of constructs

Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC)

The backbone of all vectors (MKK4_SPYCE and MPK3_SPYNE, kindly provided by Dr. Andrea Pitzschke) used in this study contain a p35S promoter (Cauliflower Mosaic virus 35 S promoter), 5′UTR (untranslated region from tobacco etch virus), our genes of interest (HvSNF7.1), C-terminal or N-terminal sequence of YFP (SPYCE or SPYNE, t35 (Cauliflower Mosaic virus 35S terminator), HA-tag (Human influenza hemagglutinin) or c-MYC-tag, and a kanamycin antibiotic resistance sequence. HvSNF7.1 (according to HvSNF7a.1 described in12) was cloned into the vector pCR2.1 (#K200001, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA) using HvSNF7.1_NcoI-F and HvSNF7.1_NotI-R as primers, digested by NcoI and NotI and inserted into previously digested MKK4_SPYCE and MPK3_SPYNE, respectively. To obtain a pSPYCE vector without insert for control reactions, plasmids were cut (NcoI/NotI), blunted using Klenow fragment and re-ligated. All the clones were verified by sequencing.

Yeast two-hybrid (Y2H)

The restriction sites NdeI and Sfil were introduced into HvSNF7.1 by PCR using the primers pGADT7_SNF7F and pGADT7_SNF7R3. Using NdeI and Sfil, HvSNF7.1 was ligated into the vector pGEM-T Easy (#A1360, Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, United States). All the clones were verified by sequencing and finally cloned into the target vectors pGADT7 AD (#630442, Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, California, United States) and pGBKT7 DNA-BD (#630443, Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, California, United States). Positive clones were verified by sequencing.

p6U::SNF7.1-mEosFP

To obtain HvSNF7-mEosFP driven by the barley hordein D promoter (p6U) and ended by the nopaline synthase terminator, HvSNF7.1-mEosFP (previously described in12) was ligated in the following into the vector p6U_pHordeinD (kindly provided by Eszter Kapusi, unpublished) using MluI. The p6U vector backbone originates from DNA Cloning Service e.K. (http://www.dna-cloning.com/vectors/Binaries_hpt_plant_selection_marker/p6U.gbk). The sequence of the Hordein D promoter was taken from27. The vector p6U_pHordeinD is based on p6U_pHordein_BamHI_SP, which was cut using BamHI/HindIII, blunted using Klenow fragment and re-ligated.

Transformation of barley endosperm cells

Barley (GP) transformation was carried out using particle bombardment17,28. T1 plants surviving hygromycin selection were genotyped using primer pairs as described in Supplemental Table 1. Homozygous T4 grains were used from transgenic p6U::SNF7.1-mEosFP plants for microscopic and Western blot analyses. The intact fusion protein SNF7.1-mEosFP was detected by Western blot using polyclonal rabbit anti-SNF7 antibody (kindly provided by D. Teis), which could detect all isoforms of HvSNF7 and the transgenic SNF7.1-mEosFP (49 kDa) (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Identified proteins classified corresponding to their involvement within the endomembrane pathway and to their diverse endomembrane functions.

| Nr. | Uniprot Accession | Protein Name | Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M0XYS5 | Coatomer subunit delta (RET2p) COPI | secretory pathway |

| 2 | M0UY14 | Golgin candidate 5 | secretory pathway |

| 3 | A0A287KUM9 | Coatomer subunit beta (COPI) | secretory pathway |

| 4 | F2E4V3 | Coatomer subunit epsilon | secretory pathway |

| 5 | A0A287HD61 | SEC. 31 homolog B (COPII) | secretory pathway |

| 6 | F2CXJ0 | Endoplasmic reticulum vesicle transporter protein | secretory pathway |

| 7 | A0A287HI31 | Transmembrane emp24 domain-containing protein 10 | secretory pathway |

| 8 | F2CQI5 | Protein transport protein Sec. 61 subunit beta | secretory pathway |

| 9 | A0A287T0X1 | Putative ADP-ribosylation factor GTPase-activating protein AGD8 (COPI) | secretory pathway |

| 10 | A0A287NDD5 | SEC. 24 like (COPII) | secretory pathway |

| 11 | A0A287N3A5 | CASP | secretory pathway |

| 12 | F2DJ14 | SEC. 13 homolog B (COPII) | secretory pathway |

| 13 | F2DF14 | Signal recognition particle subunit SRP72 | secretory pathway |

| 14 | A0A287J9F8 | Gamma-soluble NSF attachment protein | secretory pathway |

| 15 | F2CRB3 | Ras-related protein RIC1 - ARA5 | secretory pathway |

| 16 | A0A287WFD7 | Peroxisome biogenesis protein 5 PEX5 | peroxisome |

| 17 | A0A287QYS2 | Proton pump-interactor 1 | PM |

| 18 | M0UEQ. 6 | Nicastrin | PM |

| 19 | F2CWF3 | Putative voltage-gated potassium channel subunit beta | PM |

| 20 | A0A287RSX4 | Proton pump-interactor 1 | PM |

| 21 | F2CS48 | redox.ascorbate and glutathione; Membrane steroid-binding protein 1 | PM |

| 22 | A0A287QB60 | SEC. 1 family transport protein SLY1 | sorting |

| 23 | A0A287XZU3 | CLC2 (CCV) | sorting |

| 24 | A0A287JMQ9 | CLC1 | sorting |

| 25 | A0A287Y199 | EHS (TPLATE) | sorting |

| 26 | F2D106 | VPS20.1 | sorting |

| 27 | A0A287NWK0 | TOL3 | sorting |

| 28 | M0X0B4 | TOL2 | sorting |

| 29 | M0XC79 | TOL1 | sorting |

| 30 | A0A287X2J4 | TOL8 | sorting |

| 31 | A0A287R3U8 | CHC1 | sorting |

| 32 | A0A287FF51 | SH3PH | sorting |

| 33 | M0YLE4 | non-specific serine/threonine protein kinase | sorting |

| 34 | A0A287QP21 | Auxilin-related protein 1 | sorting |

| 35 | A0A287FUM0 | SNX2b | sorting |

| 36 | A0A287U4A9 | VPS29 | sorting |

| 37 | A0A287K2S5 | SKD1 | sorting |

| 38 | A0A287H7X6 | VSR1 | sorting |

| 39 | A0A287NZS5 | VSR1 | sorting |

| 40 | A0A287R1U7 | VSR1 | sorting |

| 41 | F2DS44 | SNX1 | sorting |

| 42 | A0A287R803 | SNF7.1 | sorting |

| 43 | A0A287XAB9 | SNF7.2 | sorting |

| 44 | A0A287RZ89 | PUX 8.1 | transport |

| 45 | A0A287WLG4 | PUX 8.2 | transport |

| 46 | A0A287G9M8 | Patellin1 | transport |

| 47 | A5CFY5 | Tubulin beta chain | transport |

| 48 | A5CFY9 | Tubulin beta chain | transport |

| 49 | A0A287FFF9 | Actin-2 | transport |

| 50 | F2DY31 | Actin-depolymerization factor 4 | transport |

| 51 | A0A287MS88 | Myosin-like protein | transport |

| 52 | M0YZY8 | Autophagy-related protein 8 C | degradation |

| 53 | A0A287FQD8 | Autophagy-related protein 3 | degradation |

| 54 | A0A287UDR1 | Vacuolar processing enzyme 1 | vacuolar processing |

| 55 | A0A287IXX5 | Vacuolar processing enzyme 2b | vacuolar processing |

| 56 | A0A287IXX4 | Vacuolar processing enzyme 2c | vacuolar processing |

| 57 | A0A287IXM3 | Vacuolar processing enzyme 2d | vacuolar processing |

| 58 | A0A287RKR9 | Vacuolar processing enzyme 4 | vacuolar processing |

| 59 | A0A287IY00 | Legumain | vacuolar processing |

| 60 | A0A287GK50 | Dynamin-related protein 1 A | dynamins |

| 61 | A0A287N3M7 | Dynamin-related protein 1 C, putative | dynamins |

| 62 | A0A287W654 | Dynamin-2A | dynamins |

| 63 | A0A287MCV3 | Dynamin-related protein 3 A | dynamins |

| 64 | A0A287GAT9 | NSF | SNARE |

| 65 | A0A287GJC4 | SYP71 protein | SNARE |

| 66 | A0A287N705 | ERO1 | Disulfide-generating enzyme and- carrier |

| 67 | A0A287EWS7 | HvPDIL2-1 | Disulfide-generating enzyme and- carrier |

| 68 | A0A287NWD9 | HvPDIL1-1 | Disulfide-generating enzyme and- carrier |

| 69 | A0A287RLW1 | HvPDIL2-2 | Disulfide-generating enzyme and- carrier |

| 70 | A0A287P669 | HvPDIL5-1 | Disulfide-generating enzyme and- carrier |

| 71 | A0A287T503 | HvPDIL1-3 | Disulfide-generating enzyme and- carrier |

| 72 | M0XFC8 | Vacuolar proton-ATPase subunit A | ATPase |

| 73 | F2DCK0 | V-type proton ATPase subunit B 1 | ATPase |

| 74 | A0A287L8C5 | YLP; Vacuolar ATP synthase subunit E | ATPase |

| 75 | F2EFW5 | Pyrophosphate-energized vacuolar membrane proton pump | ATPase |

| 76 | A0A287X931 | RABA1d/d | GTPase |

| 77 | A0A287EG08 | AtRABD1 | GTPase |

| 78 | A0A287K336 | RABD2a | GTPase |

| 79 | A0A287GB98 | RABG3f | GTPase |

| 80 | A0A287HZ99 | Ras-related protein RABH1b | GTPase |

| 81 | A0A287WHY3 | Signal recognition particle receptor beta subunit | GTPase |

| 82 | A0A287HAL5 | Signal recognition particle 54 kDa protein | GTPase |

| 83 | A0A287UM33 | ADP-ribosylation factor GTPase-activating protein AGD12 | GTPase-activating protein |

| 84 | A0A287FZ46 | GDI1/2 | RAB regulator |

| 85 | F2CQ27 | GTP-binding nuclear protein | GTP binding protein |

| 86 | A0A287P5H8 | Ran-binding protein | GTP binding protein |

| 87 | M0ZCE0 | Ran-binding protein 1 | GTP binding protein |

| 88 | M0YLZ9 | Ran-specific GTPase-activating protein 2 | GTP binding protein |

| 89 | A0A287QN80 | GTPase SAR1A | GTP binding protein |

| 90 | M0X1Z2 | Ran GTPase activating protein | GTP binding protein |

| 91 | F2CWF2 | GTP-binding protein SAR1A | GTP binding protein |

| 92 | A0A287H404 | GTP-binding protein | GTP binding protein |

| 93 | F2DYD4 | GTP-binding protein SAR1A | GTP binding protein |

| 94 | M0YT49 | ADP-ribosylation factor homolog1 | GTP binding protein |

Microscopy

Live cell imaging

GP and the transgenic line TIP3-GFP13 were used for live cell imaging as previously described13. ER-Tracker Green (BODIPY FL Glibenclamide; #E34251, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) and LysoTracker Red DND-99 (#L7528, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) were used to visualize ER and acidic compartments, respectively. ER-Tracker Green was used as previously described13. In detail, at least three randomly selected transgenic and GP grains were harvested at 6, 12 and ≥20 DAP, sectioned, washed, and stained as follows: ER-Tracker Green, 1 h (final concentration, 2 µM, from 1 mM DMSO stock with water); LysoTracker Red, 30 min (final concentration, 2 µM, from 1 mM DMSO stock with water). Mock treatments included the final DMSO concentration in water. Sections were mounted in tap water and immediately imaged by the Leica SP5 CLSM using sequential scans with filter settings for GFP (excitation 488 nm, emission 500–530 nm), LysoTracker Red (excitation 561 nm, emission 570–630 nm), and ER-Tracker Green (excitation 488 nm, emission 500–531 nm). Transgenic p6U::SNF7.1-mEosFP grains were chipped, mounted in tap water and analyzed by CLSM with excitation at 488 nm, emission 508–540 nm.

Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC)

A single colony of transformed Agrobacterium tumefaciens was inoculated in 5 mL of YEB-Medium (0.5% beef extract, 0.5% sucrose, 0.1% yeast extract, 0.05% MgSO4*7H2O) containing appropriate antibiotics and incubated at 28 °C overnight. In the morning, 5 ml of the same medium was re-inoculated with 1 ml of the pre-culture. Cells were collected by centrifugation at 5000 g for 5 min and the pellet was washed with 1 mL infiltration buffer (10 mM MES pH 5.7, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 µM acetosyringone). Washed cells were re-collected by centrifugation (5000 g, 5 min) and washed two additional times with 500 µl infiltration buffer and finally adjusted to an OD600 of 0.3. The resuspended bacteria containing the corresponding binary expression vectors for BiFC were mixed in a ratio of 1:1 and incubated for 3 h in darkness. Nicotiana benthamiana plants were cultivated in the greenhouse on soil, maintained at 60% humidity, with a 14 h light period and a 25 °C day/19 °C night temperature cycle. The entire leaf area of two leaves per Nicotiana benthamiana plant was infiltrated with the bacterial solution through the abaxial side using a 1 mL syringe. After infiltration, the plants were kept in a tray with a hood at 25 °C. After 2–5 days, the detection of protein–protein interaction by BiFC was performed using confocal microscopy (Leica SP5 CLSM). The excitation wavelength was 514 nm (argon laser) and emission was detected between 525–600 nm and 680–760 nm for YFP and autofluorescence detection, respectively. Red channels were visualized in magenta.

Histological and immunofluorescence studies

At least three randomly selected GP grains were harvested at 6, 12 and ≥20 DAP and fixed, embedded and sectioned as described in15,16. The 1.5 µm sections on glass slides were stained with toluidine blue (0.1%) for 30 s at 80 °C on a hot plate and rinsed with distilled water. Immunofluorescence microscopy of developing barley grains was performed as described by16 using: polyclonal rabbit anti-V-ATPase antibody (#AS 07 213, Agrisera, Vännäs, Sweden, raised against Arabidopsis thaliana At4g11150, specific for higher plants including Hordeum vulgare), dilution 1:100; polyclonal rabbit anti-actin antibody (#AS 13 2640, Agrisera, Vännäs, Sweden, raised against Arabidopsis thaliana actin-1/-2/-3/-4/-5/-7/-8/-11 and-12, specific for higher plants including Hordeum vulgare), dilution 1:50; polyclonal rabbit anti-tubulin-α antibody (#AS 10 680, Agrisera, Vännäs, Sweden, raised against Arabidopsis thaliana tubulin alpha-1/-2/-4/-5/-6-chain, specific for higher plants including Hordeum vulgare, dilution 1:50); polyclonal rabbit anti-VSR1 antibody, dilution 1:100, kindly provided by Dr. Liwen Jiang, raised against Pisum sativum BP80, specific for Pisum sativum, Arabidopsis thaliana and BY2-cells) and polyclonal rabbit anti-SNF7 antibody (dilution 1:100, kindly provided by D. Teis, raised against Saccharomyces cerevisiae SNF7, specifically recognizing SNF729). Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 488 (#A-11008, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) (dilution 1:30) was used as a secondary antibody. The specificity of the first antibodies for GP was proved by western blot analyses (Supplementary Fig. 1.) At least three sections were analyzed, and pictures captured by Nikon Eclipse Ni. Images were processed using Leica confocal software version 2.63, ImageJ and Adobe Photoshop CS5. Negative controls show sections incubated only with the secondary antibody.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

The coat was removed from grains harvested at 6, 12 and ≥20 DAP, chopped and immediately fixed in 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde plus 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate, pH 7.4, overnight at 4 °C. After washing with sodium cacodylate buffer, the samples were immersed in OsO4 for one and a half hours at room temperature followed by washing with buffer. The chemically fixed samples underwent dehydration in an ethanol series (30%, 50%,70%, 95% ethanol for 10 min each, and two times 100% ethanol). Prior to infiltration with resin, the ethanol was replaced by 100% acetone. The dehydrated samples were infiltrated with low viscosity resin (Agar Scientific Ltd, Stansted, UK) as follows: 1/3 volume resin and 2/3 volume acetone for 15 min, 1/2 volume resin and 1/2 volume acetone for 30 min, 2/3 volume resin and 1/3 volume acetone for 3 h, and pure resin overnight. Subsequently, samples were transferred in resin-filled tubes and polymerized in an oven at 65 °C for two days.

Ultrathin sections (90 nm) of the grains were cut by using an ultramicrotome LEICA EM UC7 (Wetzlar, Germany) and a diamond knife type “ultra 45°” (DIATOME Ltd., Switzerland), collected on copper grids (300 mesh) and stained with 2.5% gadolinium triacetate for 30 min and 3% lead citrate for 8 min. Grids were analyzed at 120 kV with a TEM Zeiss Libra 120 equipped with a LaB6 (Lanthanum-Hexaboride) cathode. Images were acquired using a side port camera Morada G2, 11 MP (Soft Imaging System GmbH, Münster, Germany) and a bottom mount camera Sharp:eye TRS (2 × 2 KP) with iTEM software and processed using Adobe Photoshop CS5.

Results

Multivariate statistics unravel proteome reorganization across multiple biological processes during barley grain development

To identify proteins that are localized at the endomembrane system and/or are functionally associated with the rearrangement of the endomembrane system in barley, grains of different development stages including 6, 10, 12 and ≥20 DAP were harvested as previously described16. We used liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to identify a total of 3,005 proteins. Our label-free quantification (LFQ) data obtained by MS was validated: first, by the comparison of the relative intensity of the HveF1a and HvVSR1 to a semi-quantitative Western blot (Supplementary Fig. S2b, Supplementary Table S2) that both show the stable and increasing trend of protein accumulation, respectively. Second, the measured protein abundances were highly reproducible with an average Pearson’s correlation coefficients of >0.95 between biological replicates (Supplementary Fig. S2c). Additionally, the performed Principal Component Analysis (PCA) supports these results and shows that samples grouped and clustered in a stage-specific manner (Fig. 1a). However, two samples of 10 DAP cluster together with samples of 6 and 12 DAP, respectively. The high distribution of the standard deviation of the normalized LFQ intensities at 10 DAP (Supplementary Fig. S2d) point to a physical variability at 10 DAP. Additionally, the seed weight between the stages are significantly different except the stage between 6 and 10 DAP (Supplementary Fig. S2e) These results are in line with the previously published microscopic data where the most dramatic endomembrane rearrangements could be observed between 8 and 12 DAP13.

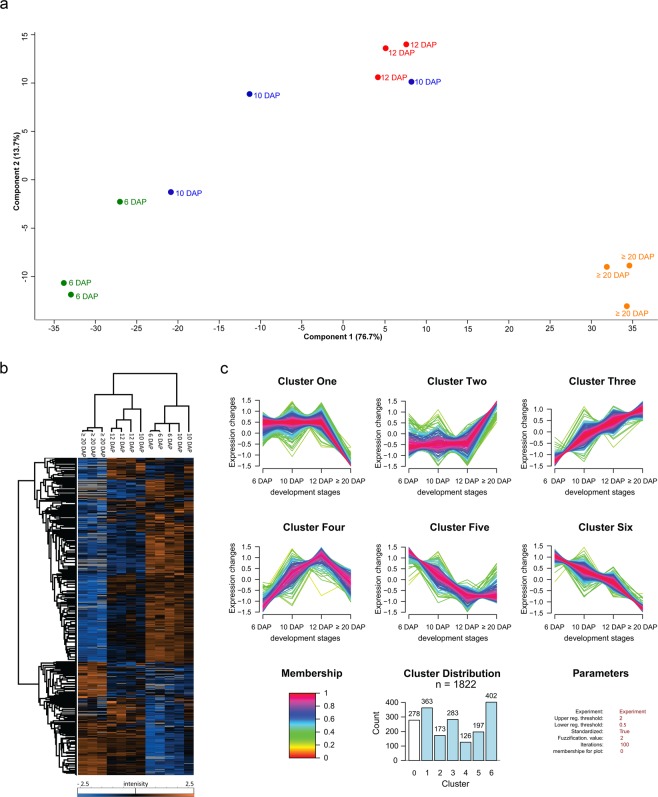

Figure 1.

Proteome profiling during barley grain development. (a) PCA was conducted on logarithmically transformed protein intensities; each dot corresponds to a single biological replicate (n = 3). (b) Hierarchical cluster analysis of quantified proteins along barley grain development was performed with Perseus after Z-score transformation of the data21. Clustering of proteins was done based on Euclidian distance while samples’ clustering is based on Pearson correlation. (c) Cluster of proteins dynamics along the grain development. Quantified proteins were subjected to unsupervised clustering with the fuzzy c-means algorithm implemented in GproX24. Cluster distribution indicates the number of proteins in each cluster. Membership value represents how well the protein profile fits the average cluster profile.

A total of 1,822 out of 3,005 were quantified in at least 9 out of the 12 analyzed biological samples (Supplementary Table S2). To determine the proteins that were significantly changed along the grain development, we applied a one-way ANOVA analysis, corrected with a permutation-based false discovery rate (FDR) (p < 0.05). Among the 1,822 quantified proteins, the abundance of 1,544 proteins was significantly changed (Supplementary Table S2). To assess the proteome dynamics during barley grain development, both PCA and a hierarchical bi-clustering analysis (HCA) were performed. Thereby identical clusters of stage-specific groups related to development stages of the barley grain were identified (Fig. 1a,b). An investigation of the PCA results shows that PC1 (76.7% of variance) separated the sample based on the different development stages, particularly between the early (6 DAP) and late development stages (≥20 DAP). PC2 (13.7% of variance) was rather more involved in the early development stage discrimination. Protein loadings on each principal component are indicated in Supplementary Table S2. As expected, SSPs were among the highest loadings on PC1. Interestingly, most of the detected changes occurred at ≥20 DAP (Fig. 1b).

To refine our protein expression pattern analysis, unsupervised clustering was performed with GproX software to partition the temporal profiles of 1,544 significantly changed proteins measured at all time points. Six clusters based on a fuzzy-mean clustering process24 were detected (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Table S2):

Proteins presenting a higher expression level at 6 than at ≥20 DAP belong to Clusters One, Five and Six. Those three clusters account for most of the significantly changed proteins (in total, 962 proteins). It is known that endosperm development involves cell division, cellular differentiation events and the deposition of SSPs between early, late and mid-development30,31. These findings were confirmed by toluidine-stained sections prepared at 6, 12 and ≥20 DAP that revealed fully cellularized endosperm including three aleurone cell layers at 6 DAP (Supplementary Fig. S3a). Cluster Four accounts for 126 proteins and shows its highest protein abundance between 10 and 12 DAP, which corresponds to mid-stage, where the differentiation of aleurone, subaleurone, and starchy endosperm is finalized (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. S3a). Finally, the 456 proteins associated with Cluster Two and Three exhibit higher expression levels at ≥20 than at 6 DAP, corresponding to the end of mid-stage and beginning of the late stage, where the accumulation of storage reserves can be observed in the endosperm (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. S3). Using LC-MS/MS, all 20 identified SSPs showed significantly higher abundance at ≥20 DAP (Supplementary Fig. S3b,c).

Toluidine staining of sections prepared at 6, 12 and ≥20 DAP confirmed protein accumulation starting at 12 DAP and increasing at ≥20 DAP in subaleurone as well as in the starchy endosperm (Supplementary Fig. S3a). Additionally, Cluster Two and Three contain HvPDIL1–1 and HINs15,16.

Development phase I contains proteins of high abundance associated with endocytosis and cytoskeleton, plasma membrane proteins, and ATPases

Based on a BLAST search, 94 proteins related to the endomembrane system (out of the 1 544 significantly changed ones) could be identified in total, where 59 compartment-specific proteins (secretory pathway, peroxisome, plasma membrane, sorting, transport, degradation, and vacuolar processing) and 35 trafficking regulators were defined (dynamins, SNAREs, disulfide-generating enzyme and- carrier, ATPase, GTPase, GTPase-activating protein, RAB regulator, and GTP binding protein) (Table 1). The abundance of all identified endomembrane related proteins at 6, 10, 12, and ≥20 DAP were visualized by a heat map categorizing the protein expression pattern based on Pearson correlation (Supplementary Fig. S4). Compartment-specific proteins and trafficking regulators were categorized in pink and blue, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S4).

The 94 proteins could be associated with the three main development phases (Supplementary Fig. S4): 39 proteins present a higher expression during the development phase I (green cluster), 15 proteins presented an expression peak at the development phase II (yellow cluster), and 40 proteins are associated to the development phase III (red cluster). Within each phase, compartment-specific proteins and trafficking regulators were categorized (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. S5a,b). Taken together, these data present molecular regulators for the endomembrane system in developing barley grain.

Among the 39 proteins identified in the development phase I, proteins related to the secretory pathway (ER, Golgi, Golgi – ER), plasma membrane, sorting pathway (endocytosis, ESCRT), transport (vesicle-mediated transport, cytoskeleton), degradation (Autophagy-related protein 3) and to vacuolar processing as well as trafficking factors (dynamins, SNAREs, disulfide-generating enzymes and carriers, ATPase, GTPase, GTPase-activating protein and GTP binding protein) were enriched at 6 and 10 DAP (Fig. 2a).

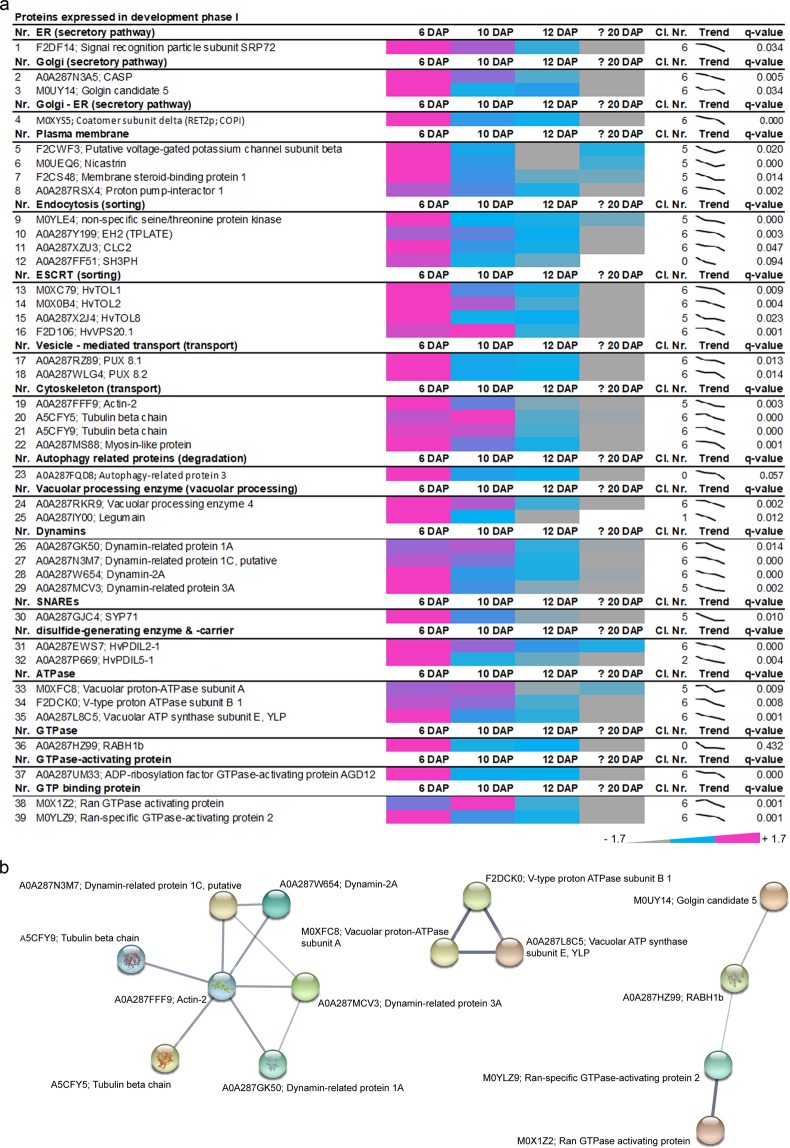

Figure 2.

Identification of proteins that are highly abundant at development phase I of developing barley grains. (a) Data-matrix heat map representing Z-score values of 6, 10, 12 and ≥20 DAP. Heat map was prepared using Microsoft Excel. Scale: grey = smallest value; blue = 50% quantile; pink = highest value. (b) Proteins present in this stage were analyzed using the STRING database. STRING default parameters were used25, protein names are indicated. PBs are identified in the bright field as small spherical structures as recently published13,15,16.

More precisely, plasma membrane-associated proteins such as putative voltage-gated potassium channel subunit beta (F2CWF3), Membrane steroid-binding protein 1 (F2CS48), Nicastrin (M0UEQ. 6) and Proton pump-interactor 1 (A0A287RSX4) present decreasing abundance in concomitance to proteins associated to the endocytosis processes such as dynamins (A0A287GK50, A0A287N3M7, A0A287W654, A0A287MCV3), tubulin (A5CFY5, A5CFY9), actin (A0A287FFF9), myosin (A0A287MS88), EH2 (A0A287Y199) and CLC2 (A0A287XZU3). In line with the constant need of energy necessary for endocytosis and plasma membrane remodeling processes, three vacuolar-ATPase subunits were identified (A: M0XFC8, B1: F2DCK0, E: A0A287L8C5). All three subunits showed a decreased expression, indicating an acidification process at the early development stage (Supplementary Table S2). Using STRING, a functional association between dynamins and cytoskeleton-related proteins was visualized (Fig. 2b), both necessary for plant endocytic processes32,33. Additionally, STRING revealed a functional correlation between several ATPases that were abundant at 6 and 10 DAP (Fig. 3b). The functional association between Golgin candidate 5, RABH1b and further GTPases shown by STRING points to an active protein sorting in the trans-Golgi or at the trans-Golgi network (TGN)34. Taken together, the proteins that are highly abundant at 6 DAP point to the necessity of cytoskeleton, acidification, and sorting during the development phase I.

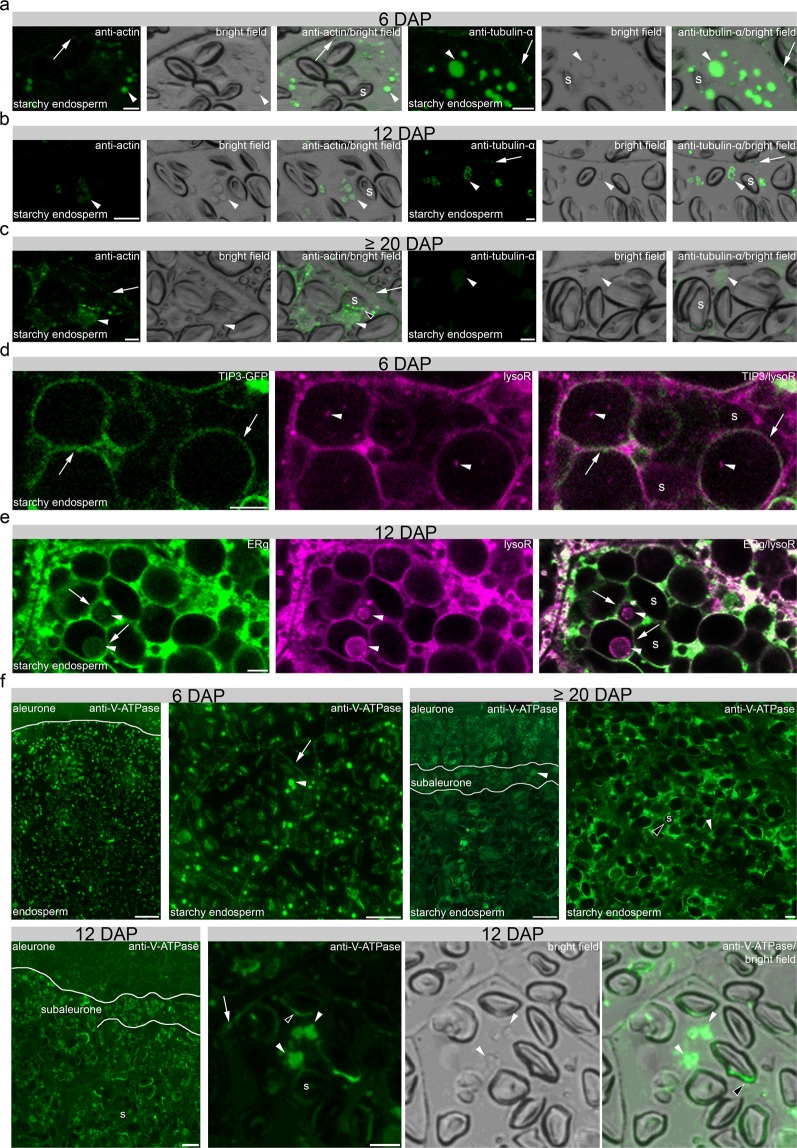

Figure 3.

In situ microscopical analyses of the cytoskeleton and acidification of PBs in development phase I. (a–c) Immunofluorescence studies of 1.5 µm prepared sections of 6, 12 and ≥20 DAP using antibodies for anti-actin and anti-tubulin-α showing a strong signal at PBs (arrowheads), respectively. PBs are identified in the bright field as small spherical structures a recently published13,15,16. Note the signal at the plasma membrane with anti-tubulin-α (arrow). The fluorescence signal intensity is weaker at 12 and at ≥20 DAP. Note the additional signal at the periphery of the starch granule at ≥20 DAP using anti-actin (black-white arrowhead). (d) LysoTracker Red (lysoR) accumulation (arrowheads) within TIP3-GFP labelled vacuoles (arrows) at 6 DAP. (e) ER-Tracker Green (ERg)-labelled compartments (arrows) accumulate LysoTracker Red (lysoR) positive PBs (arrowheads) at 12 DAP. (f) Immunofluorescence studies of 1.5 µm sections of 6, 12 and ≥20 DAP using anti-V-ATPase antibody showing no positive signal at aleurone at 6 DAP whereas strong signal could be detected in aleurone at ≥20 DAP. In starchy endosperm, anti-V-ATPase antibody labels strongly PBs (arrowheads) and was found weaker at the plasma membrane (arrows). At 12 DAP, signal appeared at PBs in subaleurone and starchy endosperm. Note the specific signal at the PBs (arrowheads), at the periphery of starch granules (black-white arrowhead) and the weak labelling of vesicles at the plasma membrane (arrow). At ≥20 DAP, the anti-V-ATPase antibody labels strongly PBs in subaleurone (arrowhead), but to lesser extent in the starchy endosperm. s = starch granule. Bars = 5 µm in a–e and 10 µm in f, except at ≥20 DAP where the bar represents 100 µm in the overview picture.

We performed immunofluorescence studies of actin and tubulin to follow the subcellular appearance of the cytoskeleton during barley endosperm development. We observed strong signals within PBs at 6 DAP, becoming weaker at 12 and ≥20 DAP, respectively (Fig. 3a–c). PBs are identified in the bright field as small spherical structures as recently published13,15,16. Interestingly, a faint actin signal was observed at the plasma membrane at ≥20 DAP, whereas the signal of tubulin at the plasma membrane was strong at 6 DAP but was reduced at 12 and ≥20 DAP (Fig. 3a–c). No signal could be detected in the negative controls for immunofluorescence for all stages (Supplementary Fig. 6b).

Recently it was shown that PBs in maize are acidified and can be visualized by live cell imaging of fluorescent organelle markers35. To determine if the identified and functionally associated ATPases are putatively involved in the acidification of PBs in barley, we first used LysoTracker Red to detect acidic compartments in the transgenic TIP3-GFP line that visualizes PSVs. At 6 DAP, acidic compartments could be observed within PSVs in the starchy endosperm (Fig. 3d). Large vacuoles are most prominent in the starchy endosperm at 6 DAP13 when the accumulation of PBs has just started (Supplementary Fig. 3)15, indicating that the LysoTracker Red-labelled compartments represent PBs. Indeed, co-labelling of ER and acidic compartments in starchy endosperm cells at 12 DAP revealed LysoTracker Red- and ER-Tracker Green-positive PBs (Fig. 3e).

To determine the time-dependent subcellular distribution of ATPase, we used immunofluorescence microscopy with anti-V-ATPase subunit epsilon antibody on sections at 6 and ≥20 DAP (Fig. 3f). V-ATPases are described to localize at the membranes of PSVs as well as in mature PB in developing pea cotyledons36. Whereas at 6 DAP a punctate structure was observed at the plasma membrane and a strong signal within PBs, a weaker labelling could be observed at the periphery of starch granules and within PBs at 12 DAP (Fig. 3f). At ≥20 DAP, an additional strong signal appeared in aleurone (putatively at the tonoplast of PSVs), whereas the signal was weak within PBs and at the periphery of starch granules in the starchy endosperm (Fig. 3f). No signal could be detected in the negative controls for immunofluorescence for 6, 10, 12 and ≥20 DAP (Supplementary Fig. 6b). Overall, our proteomics and in situ microscopic results point to a high abundance of proteins involved in cytoskeleton regulation and acidification of PBs at early barley grain development stage.

Sorting-associated proteins preferentially accumulate at development phase II

Among the 15 proteins associated with development stage II (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. S4, yellow tree), we found one peroxisome protein, PEX5 (A0A287WFD7); one cytoskeleton protein, Actin-depolymerizing factor 4 (F2DY31); proteins related to endocytosis, CHC1 (A0A287R3U8), Auxilin-related protein 1 (A0A287QP21); as well as proteins of ESCRT machinery, vacuolar processing enzymes (VPEs), GTP-binding proteins, GTPases, and ATPases (Fig. 4a). Again, three ESCRT proteins, TOL4 (A0A287NWK0), SNF7.1 (A0A287R803) and SNF7.2 (A0A287XAB9) were identified, pointing to sorting processes including MVBs already detected in development phase I.

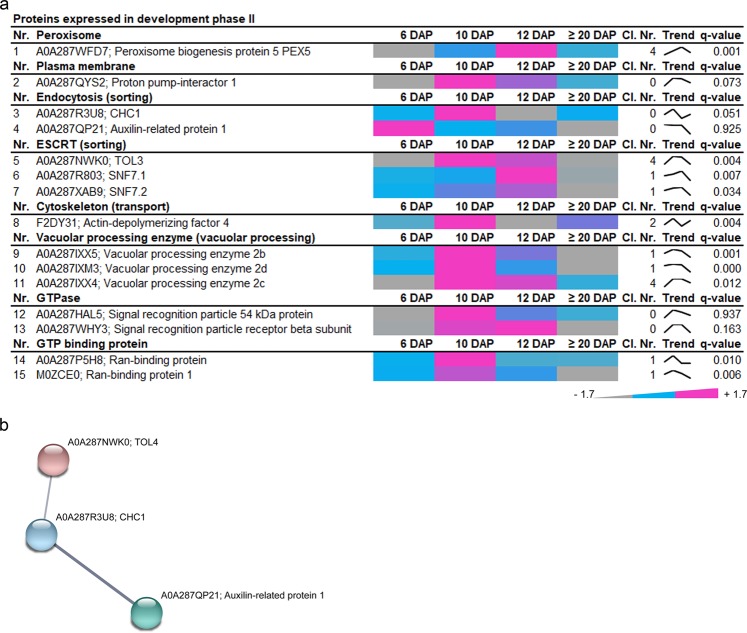

Figure 4.

Identification of highly abundant proteins at development phase II of developing barley grains. (a) Data-matrix heat map representing Z-score values of 6, 10, 12 and ≥20 DAP. Heat map was prepared using Microsoft Excel. Scale: gray = smallest value; blue = 50% quantile; pink = highest value. (b) Proteins present in this stage were analyzed by STRING database. STRING default parameters were used25, protein names are indicated.

Using STRING, a functional association between the ESCRT TOL4, clathrin, and an auxilin-related protein appeared (Fig. 4b). TOLs have putative clathrin-binding motifs37 and auxilin-related protein 1 functions as clathrin-uncoating factor38, and both were described to be involved in endocytosis. Interestingly, proteins involved in sorting, transport, and degradation have been already identified in the development phase I.

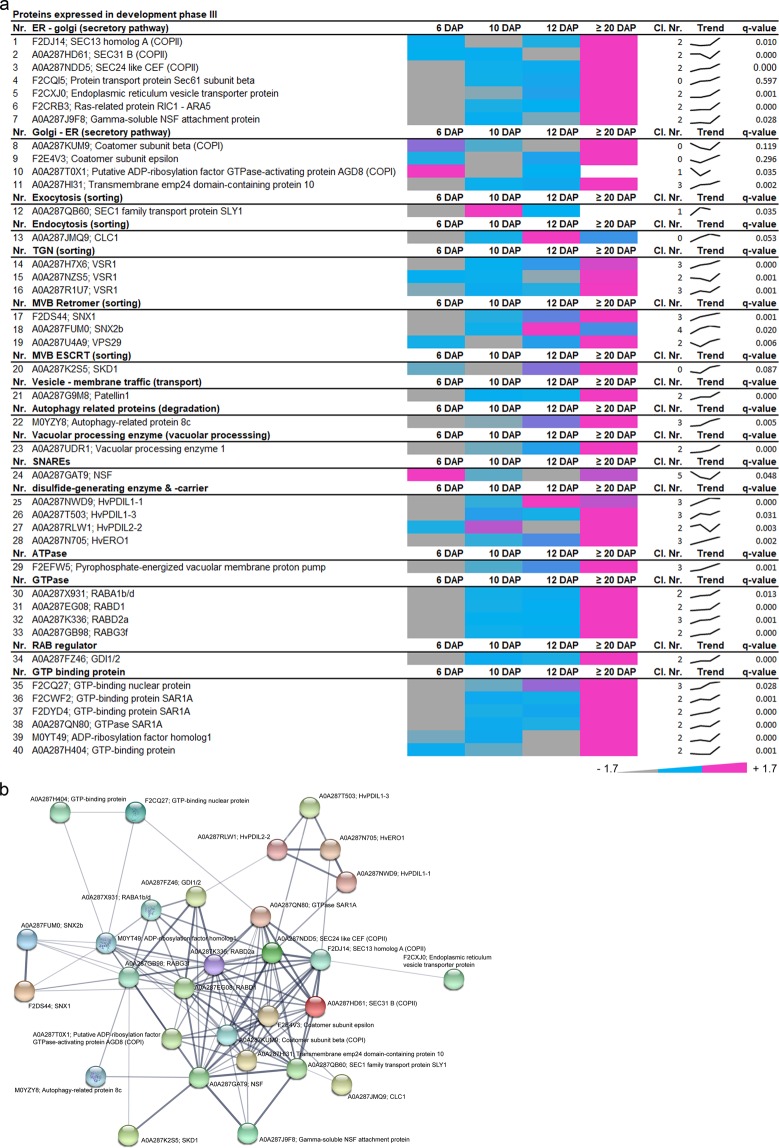

Compartment-specific proteins and trafficking regulators participating in storage protein targeting, transport, and deposition are accumulating at development phase III

In total 40 proteins were associated with development phase III, most of them highly abundant at ≥20 DAP (Fig. 5a). Interestingly, 11 proteins involved in the secretory pathway (e.g., COPII/COPI), and 9 proteins that function in the protein sorting (e.g., VSR1, retromer, and ESCRT) were identified. Additionally, proteins involved in degradation (autophagy-related 8c, vacuolar processing enzyme1) were highly abundant at ≥20 DAP. Among other proteins, one SNARE was identified as well as 11 trafficking regulators associated with the ATPase, GTPase or the GTP-binding group. Strikingly, endomembrane-associated proteins characterizing the phase III presented the highest interconnectivity within the STRING database compared to phases I and II (Fig. 5b).

Figure 5.

Identification of highly abundant proteins at development phase III of developing barley grains. (a) Data-matrix heat map representing Z-score values of 6, 10, 12 and ≥20 DAP. Heat map was prepared using Microsoft Excel. Scale: gray = smallest value; blue = 50% quantile; pink = highest value. (b) Proteins present in this stage were analyzed by STRING database. STRING default parameters were used25, protein names are indicated.

As expected, important ER markers such as the disulfide isomerase protein (HvPDIL1-1 and ERO1) were found in this group, being in line with the accumulation of SSPs (Supplementary Fig. S2). The STRING network indicates that the group of ER markers is linked with proteins associated with the secretory pathway and their associated factors such as a RAB regulator GDI1/2 (A0A287FZ46), COPII (F2DJ14, A0A287HD61, A0A287NDD5) as well as COPI proteins (A0A287KUM9, A0A287T0X1) and other regulators (F2E4V3, A0A287HI31). Interestingly, this core set of proteins are functionally associated with diverse proteins including ESCRT related SKD1 protein (A0A287K2S5), autophagy-related protein 8c (M0YZY8), sorting nexins, as well as regulatory factors related proteins (GTPases, GTP binding proteins).

However, some of the identified functional groups clustered within each development phase of barley grain development, suggesting a temporal regulation of the identified mechanisms. For example, VSR1, which participates in vacuolar sorting of 12S globulins and 2S albumins in A. thaliana seeds39, was strongly localized in the aleurone layer instead of the starchy endosperm at ≥20 DAP (Supplementary Fig. 7a), indicating predominantly functional activity in the aleurone layer during development or during germination. The vacuolar processing enzymes (VPEs) are known to be involved in PCD40–42 as well as in processing SSPs in seeds43–45. Similarly, ESCRT-related proteins contained members of each development phase, indicating tissue-specific functions of proteins.

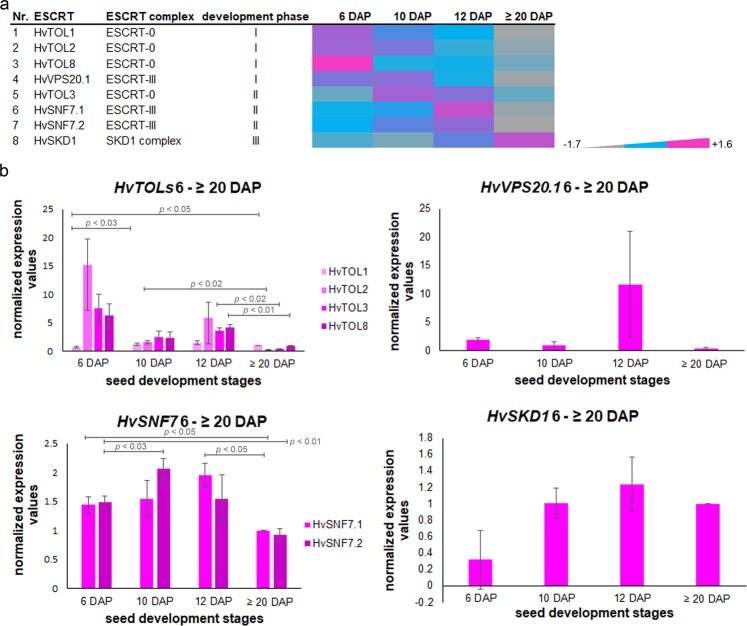

ESCRT-III HvSNF7 associates to MVBs at development phase I and both localize to and within PBs at development phase II and III

Proteomic analysis identified eight proteins related to ESCRT-0, ESCRT-III and SKD1 complex. Interestingly, they showed different expression patterns and subsequently belonged to different clusters (Fig. 6a).

Figure 6.

Temporal regulation of identified ESCRT proteins and transcripts. (a) Data-matrix heat map representing Z-score values of 6, 10, 12 and ≥20 DAP. Heat map was prepared using Microsoft Excel. Scale: grey = smallest value; blue = 50% quantile; pink = highest value. HvTOL1, HvTOL2, HvTOL8, and HvVPS20.1 show a high abundance at developmental phase I, but a continuous decrease over the development of barley grain. HvTOL3, HvSNF7.1, and HvSNF7.2 exhibit an expression peak during developmental phase II, while HvVPS4 continuously accumulated during the early grain development up to developmental phase III. (b) Temporal quantification of HvESCRT transcripts in developing barley grains. Bar graphs describe the average over three biological replicates of the normalized transcripts from HvTOL1/HvTOL2/HvTOL3/HvTOL8, HvVPS20.1, HvSNF7.1/HvSNF7.2 and HvSKD1 at 6, 10, 12 and ≥20 DAP. For statistical analyses we performed a Student’s t-test (n = 3). Bars represent standard deviation; p-values are indicated.

To gain insight into theexpression behavior of identified ESCRT members, we analyzed the transcript levels of HvTOLs, HvSNF7s, HvVPS20.1, and HvVPS4 during barley grain development by RT-qPCR (Fig. 6b). RNA was isolated from whole grains harvested at 6, 10, 12 and ≥20 DAP, and the previously characterized most stable genes were used to normalize the ESCRT transcripts16. A high correlation between transcript and protein abundances for all identified HvESCRT members was observed, except for HvVPS4. Even though the HvVPS4 transcript follows the same trend as HvSNF7 transcripts and proteins, HvVPS4 protein increased, suggesting a delay of the response or a fine-tuning of HvVPS4 translation (Fig. 6b). These results indicate that the expression of HvESCRT is temporally regulated during barley grain development.

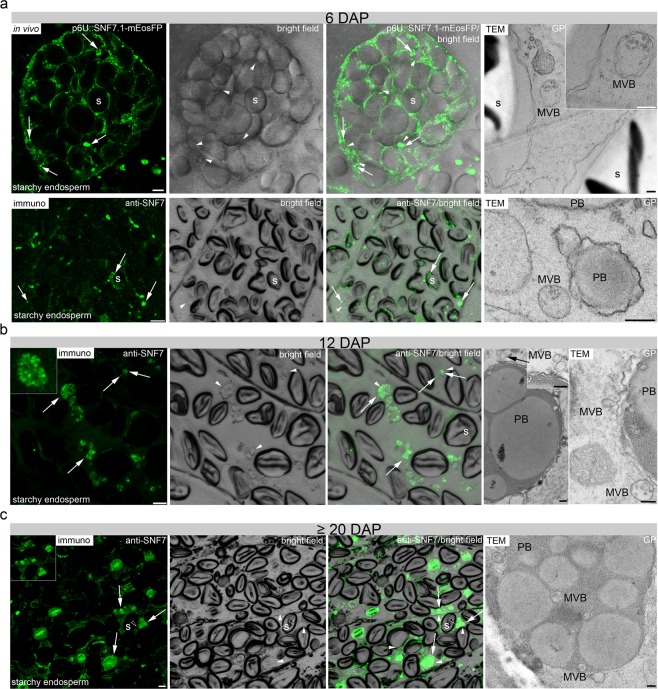

ESCRT originally refers to a protein–protein interaction network in yeast and metazoan cells that coordinates sorting of ubiquitinated membrane proteins into intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) of the MVB46–48. Specifically, ESCRT-III is known to be necessary for membrane remodeling that drives the biogenesis of MVBs49,50. Recent electron tomography studies in A. thaliana revealed that intraluminal vesicles form as large networks of interconnected or concatenated vesicles. AtSNF7 was detected in the intervesicle bridges, suggesting that ESCRT-III proteins remain trapped inside the vesicle cluster in MVBs and are finally delivered together with the cargo into the vacuole51–53. So far, no observations of HvSNF7 and MVBs have been reported in barley endosperm tissues. Thus, the subcellular localization of HvSNF7 and the identification of MVBs was performed. To elucidate the subcellular localization of HvSNF7, we first studied the localization of HvSNF7 in vivo at the early development stage using the transgenic line p6U::SNF7.1-mEosFP. Confocal live cell imaging of the p6U::SNF7.1-mEosFP transgenic line revealed punctual structures and few agglomerations around PBs at 6 DAP (Fig. 7a). AtSNF7.1 is known to form homodimers and thus can possibly lead to agglomerations54. Indeed, bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) and Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) analyses revealed homodimerization of HvSNF7.1 (Supplementary Fig. 8a,b). We used an anti-SNF7 antibody to analyze the localization by immunofluorescence microscopy at 6 DAP where the observations of small punctual structures and few agglomerations from the live cell imaging could be confirmed (Fig. 7a). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analyses showed that grains at 6 DAP contained MVB’s in proximity to starch granules and PBs, as representatively displayed in Fig. 7a. As live cell imaging in developing endosperm is limited to early- and mid-development stages13, immunofluorescence analyses of sections prepared from 12 and ≥20 DAP were analyzed. Strong signals within PBs at 12 and ≥20 DAP could be detected (Fig. 7b). The punctured structures that could be observed inside the PBs possibly appeared by fusing of several smaller PBs (Fig. 7b). Additionally, a weak signal could be observed at the periphery of starch granules at 12 and ≥20 DAP (Fig. 7b). Indeed, TEM analyses identified MVBs associated with PBs at 12 DAP and within fused PBs at ≥20 DAP (Fig. 7b). These findings indicate that HvSNF7 is first localized at vesicular structures (putatively at MVBs) and later associated with single PBs and finally localized inside fused PBs.

Figure 7.

Localization of HvSNF7 and MVBs in developing barley grains. (a) Confocal live cell imaging of p6U::SNF7.1-mEosFP and immunofluorescence study using anti-SNF7 at 6 DAP showing both punctate structures (arrows) around protein PBs (arrowheads) and starch granules (indicated by the index s). Note the MVB between two starch granules in the TEM section (ca. 90 nm in thickness) and nearby PBs at 6 DAP. (b, c) Immunofluorescence studies of 1.5 µm sections of 12 and ≥20 DAP using anti-SNF7 showed weak/strong punctate structures (arrows) at PBs/within PBs (arrowheads) at 12 DAP whereas a more diffuse signal (arrows) within the PBs (arrowheads) could be detected at ≥20 DAP. At 12 DAP, a MVB approximates to a PB (left and right image) and fuses with a membrane surrounding a PB (right image). MVBs are detected within fused PBs at ≥20 DAP. Scale = 5 µm, except in TEM images = 250 nm. PBs are identified in the bright field as small spherical structures as recently published13,15,16.

Discussion

Proteomics and in situ microscopic analyses enable the mapping of the endomembrane system of developing barley endosperm

Many proteomic analyses in barley grain allow us to identify and understand the molecular composition of developing barley grain55–57. However, less is known about proteins regulating the endomembrane system in developing barley grains. Only one of the proteins identified in our study, Membrane steroid-binding protein 1 (F2CS48), was recently characterized in barley58. Recent studies have shown that the endomembrane system and SSP trafficking are spatio-temporally regulated in developing barley endosperm between 8 and 12 DAP13,15. This time-dependent regulation was confirmed by PCA analysis of our proteomics data, which revealed stage-specificity of protein expression during grain development.

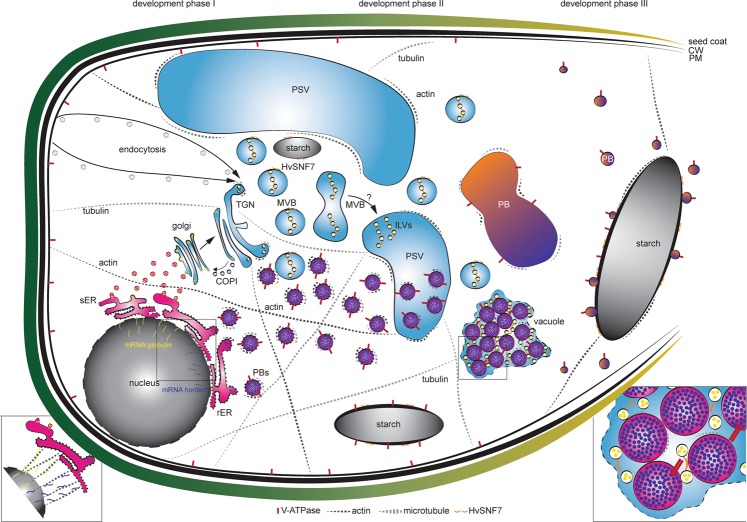

A detailed analysis of the 94 endomembrane related proteins associated them with three development phases: I, II and III. Altogether with previously published work, correlation of proteomics data with in situ microscopic analyses allowed us to provide the first temporal map of endomembrane-related proteins involved in stage-specific regulation of different endomembrane processes (Fig. 8): in development phase I, prolamin and glutelin RNAs are localized to two subdomains of the cortical ER, and targeted to the Golgi or to PBs by RNA-binding proteins and the cytoskeleton59–63. Additionally, development phase I displays endocytic activities involving plasma membrane rearrangement. Such processes have been shown to be associated with specific cytoskeleton dynamics: besides the necessity of the plant cytoskeleton in vesicle trafficking and organelle movement64, actin is required for the auxin-dependent convolution and deconvolution of the vacuole65.

Figure 8.

Quantitative in situ mapping of the endomembrane system during barley endosperm development. Quantitative proteomics and in situ microscopic analyses identified HvSNF7 and MVBs as putative key players for protein sorting into PBs during barley starchy endosperm development. At developmental phase I, mRNA of e.g., globulin and e.g., hordein are transported by the cytoskeleton to the ER where they are entering different protein trafficking pathways (zoom in)59–63. During developmental phase I and II, PSVs become smaller and PBs are formed, both putatively regulated by the cytoskeleton. In parallel, MVBs containing HvSNF7 appear and possibly fuse with PSVs, leading to PSVs containing HvSNF7 positive ILVs and PBs (zoom in). Between developmental phase II and III, PSVs collapse, and PBs fuse to one big PB containing HvSNF7. At developmental phase III, PBs become smaller again, attaching to the protein matrix at the periphery of the starch granule. Note the additional localization of HvSNF7 at the starch granules between phase I and III. Additionally, V-ATPase localize to PBs at developmental phase I, acidifying PBs. V-ATPase could be further observed at starch granules during development. Schema is not in scale. PSV, protein storage vacuole; MVB, multivesicular body; ILVs, intraluminal vesicles; PB, protein body; sER, smooth ER; rER, rough ER; CW, cell wall; PM, plasma membrane.

Specifically, SNAREs, actin and its associated motor protein myosin shape the vacuole by actin-dependent constrictions. While the protein accumulation starts at 6 DAP with observable PBs at 8 DAP, the size of PSVs decreases between 8 and 10 DAP. As we could observe actin as well as tubulin associated with PBs, we conclude that the cytoskeleton proteins present at early stages of barley endosperm development regulate the PBs formation/trafficking and the size of PSVs. Concurrent with the endocytic activity, microscopic analyses indicate an increase of the acidity within PBs. During development phase II, processes associated with the sorting system seem to be highly active. Recently, MVBs were discussed to be taken up into the vacuole by autophagy66. Additionally, studies in A. thaliana root cells have shown that central vacuoles were derived from MVB to small vacuole transition and subsequent fusions of small vacuoles67.

Thus, we propose that MVBs loaded with HvSNF7 possibly contribute to PSV rearrangement events, resulting in large PSVs containing PBs associated with MVBs and HvSNF7, as it is known that PBs are taken up by PSVs at 10 DAP13. Finally, during development phase III, PBs, MVBs, and HvSNF7 were found in proximity to the protein matrix at the periphery of starch granules, while the presence of the cytoskeleton was reduced.

Here, we point out the necessity to correlate proteomics data with microscopic analysis for reasons of spatio-temporal specificity. Although the bulk of the barley grain is mainly occupied by the starchy endosperm, we cannot exclude that identified proteins can reflect different spatial activity. For example, VPE4 was described to be most expressed in the pericarp of barley between 8 and 10 DAP68 and to be necessary for programmed cell death execution in the developing pericarp42, thereby being responsible for the grain size, starch and lipid content. As our proteomics data identified VPE4 to be most abundant at 6 and 10 DAP and subsequently to be grouped into development phase I, we assume the main function of VPE4 is in the pericarp. In contrast, VPE2b, c, and d, which are most abundant between 10 and 12 DAP and were grouped to development phase II, have been described to be involved in nucellar PCD68. Thus, proteomics from dissected sections would be useful to identify tissue-specific proteins. In order to refine our analysis to a spatio-temporal level, we compared our dataset with previously published LMD-based proteomics analysis15. However, only four out of our 94 identified endomembrane related proteins could be detected (F2DY31, Actin-depolymerization factor 4; A0A287NWD9, HvPDIL1-1; A0A287RLW1, HvPDIL2-2; and F2CQ27, GTP-binding nuclear protein). This indicates a detection range limitation of proteomic analyses of dissected samples prepared for laser microdissection. Consequently, a combined analysis of proteomics together with microscopy appears as the most appropriate strategy.

It is worth mentioning that our data provide comprehensive coverage of the endomembrane-associated proteins involved in the rearrangement of the endomembrane system and protein trafficking. However, we cannot entirely exclude additional proteins involved in these processes or organelle-specific proteins involved in other processes. For example, even though the importance of the Golgi in protein trafficking was shown previously in wheat in the transition between stage I and II69–71, only two Golgi-associated proteins could be found (Golgin 5 and CASP), both grouped to development phase I.

In order to define if Golgi-associated proteins are underrepresented in our dataset, we compared our data with previously identified proteins in A. thaliana72. Interestingly, we could explicitly identify more than 10 Golgi-resident proteins such as cell wall synthesis-associated proteins (e.g., UDP-glucuronic acid decarboxylase, A0A287H8Z0), which are parts of the glycosylation processes (Supplemental Table 2). It is possible that these identified proteins are active in aleurone, as previous data characterized the barley aleurone N-glycoproteome, in which numerous N-glycosylation sites were identified that play key roles in protein processing and secretion73.

How do ESCRTs and MVBs contribute to PB formation

Although MVBs were reported to be responsible for targeting proteins to the storage vacuole in maize aleurone cells74,75, their existence and localization during cereal endosperm development has so far not been investigated. Here, our proteomics data revealed VPS29, SNX1, and SNX2b, proteins from the retromer complex, mediating the recycling pathway at the TGN and at the MVB76. Additionally, our proteomics data identified eight ESCRT proteins (four from ESCRT-0, three from ESCRT-III and one from the SKD1 complex) quantified over all three development stages. MVBs have been suggested to arise by TGN maturation77,78 with the support of Rab GTPases79. It is worth mentioning that several Rab GTPases were detected over all three different development stages, possibly supporting MVB maturation.

Additionally, ESCRT are known to be necessary to drive the formation of ILVs in MVBs46–48. Only few studies concerning ESCRT proteins are described in cereals: in maize, supernumerary aleurone layer1 (Sal1), that encodes the maize homolog of VPS46/CHMP1 (ESCRT-III associated), restricts aleurone cell identity to the outer cell layer of endosperm80. SAL1 preserves the proper plasma membrane concentration of DEFECTIVE KERNEL1 (DEK1) and CRINKLY4 (CR4), both involved in aleurone cell fate specification, by regulating the internalization and degradation of SAL1 positive endosomes74. The rice AAA ATPase LRD6-6, which is homologous to the AAA ATPase VPS4/SKD1, was identified as an interactor with OsSNF7b/c (Os06g40620/Os12g02830) and OsVPS2.2 (Os03g43860), supporting its putative MVB-mediated vesicular trafficking function81. OsLRD6-6 is described to be localized at MVBs, to be required for MVBs-mediated vesicular trafficking and to inhibit the biosynthesis of antimicrobial compounds for the immune response in rice81.

Recently, the overexpressed ESCRT-III-associated component HvVPS60 was shown to be involved in protein targeting in developing barley endosperm12. Here, seven of the identified ESCRT proteins were most expressed at development phase I and II, indicating a possible involvement in MVB body formation. The high abundances of the ESCRT-0 proteins, HvTOL1, HVTOL2 and HvTOL8 in the development stage I indicate early steps of cargo endocytic events to the vacuole: originally, nine Tom1 (target of Myb1) proteins with a domain structure similar to the VHS domain of ESCRT-0 were identified and it was speculated that these proteins are responsible to load the ESCRT machinery82. Tom1 proteins were further characterized as members of the A. thaliana TOL family (TOM1-LIKE), which are able to bind ubiquitin directly and participate in the endocytic trafficking of plasma membrane proteins, such as the auxin efflux facilitator PIN237. HvTOL3, which was detected at development phase II, may have an additional/different function, as it was already previously speculated that AtTOLs can participate in different pathways of distinct endosomal systems of plants83.

Our proteomics, RT-qPCR, microscopic and biochemical analyses showed a highly similar protein expression and transcription behaviour of both HvSNF7.1/2, which is reasonable as interaction studies showed heterodimerization54. Snf7/VPS32 induce membrane curvature at MVBs by assembling into long spiral filaments and are discussed to be involved in corralling the ESCRT cargo at the vesicle bud84–86. Given the transgenic line p6U::SNF7.1-mEosFP, which showed punctate structures and are most probably labelling MVBs, and the TEM analyses, we were able to detect MVBs around PBs at early barley endosperm development stages, and later within fused PBs.

To conclude, our proteomic approach combined with in situ microscopy, which focused on endomembrane-associated proteins isolated from four different stages of barley grain development, provide only a snapshot of the endomembrane system dynamics. Future studies will be needed to verify the temporal protein-protein interactions identified by the STRING analysis. Furthermore, it would be of interest to study the endomembrane system remodeling under abiotic stress conditions that are likely to affect the SSPs synthesis and/or the production of recombinant proteins. Finally, experimental proof of the involvement of cytoskeleton-related proteins, MVBs and ESCRT in sorting proteins to the PBs, ideally obtained by investigating mutant barley lines impaired in ESCRT function using proteomics and in situ microscopy, has yet to be provided. Nevertheless, the proteins that have been identified in association with the endomembrane system are useful targets for genetic engineering to modulate SSPs accumulation.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Roland Berdaguer, Doris Abraham for screening transgenic lines, cloning HvSNF7.1 for Y2H and with the TEM, respectively. EM work, including technical assistance with the TEM by Norbert Cyran, was performed at the Core Facility Cell Imaging and Ultrastructure Research, University of Vienna - member of the Vienna Life‐Science Instruments (VLSI). We are grateful to Christiane Schwartz for RT-qPCR support and Dr. Karl Schedle from Institute of Animal Nutrition, Livestock Products, and Nutrition Physiology (TTE), University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna for sharing the RNA lab. We thank the BOKU-VIBT Imaging-Center and Dr. Monika Debreczeny for help with LMD. We additionally thank Dr. Erika Isono for sharing the Y2H strain YT190. We thank Dr. Liwen Jiang for kindly providing the VSR1 antibody. We thank Dr. David Teis for kindly providing the SNF7 antibody. We thank Dr. Andrea Pitzschke for kindly providing MKK4_SPYCE and MPK3_SPYNE encoding plasmids and Dr. Eszter Kapusi for kindly providing the vector p6U_phordeinD. A special thanks to the master gardeners Thomas Joch and Andreas Schröfl and their team. We thank MSc Jakob Weiszmann for fruitful discussion. This work was financially supported by the Austrian Science Fund FWF (P29454-B22 and P29303-B22) and Erasmus+ Job Shadowing program. We thank Dr. Alois Schweighofer for critical reading of the manuscript.

Author contributions

V.R., J.H., S.R. and V.I. designed the experiments. V.R., J.H., M.W., S.R., A.S., C.G., B.D., G.D., P.-J.R., M.S. and V.I. conducted the experiments and analyzed data. E.S. discussed data and results. V.R. and V.I. wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-58740-x.

References

- 1.Olsen Odd-Arne. ENDOSPERMDEVELOPMENT: Cellularization and Cell Fate Specification. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology. 2001;52(1):233–267. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.52.1.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olsen OA. Nuclear endosperm development in cereals and Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant. Cell. 2004;16(Suppl):S214–227. doi: 10.1105/tpc.017111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guo B, et al. Comparative Proteomic Analysis of Two Barley Cultivars (Hordeum vulgare L.) with Contrasting Grain Protein Content. Front. plant. Sci. 2016;7:542. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Psota V, Vejrazka K, Famera O, Hrcka M. Relationship between grain hardness and malting quality of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) J. Inst. Brew. 2007;113:80–86. doi: 10.1002/j.2050-0416.2007.tb00260.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore Katie L., Tosi Paola, Palmer Richard, Hawkesford Malcolm J., Grovenor Chris R.M, Shewry Peter R. The dynamics of protein body formation in developing wheat grain. Plant Biotechnology Journal. 2016;14(9):1876–1882. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shewry PR, Halford NG. Cereal seed storage proteins: structures, properties and role in grain utilization. J. Exp. Bot. 2002;53:947–958. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/53.370.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arcalis E, Ibl V, Peters J, Melnik S, Stoger E. The dynamic behavior of storage organelles in developing cereal seeds and its impact on the production of recombinant proteins. Front. Plant. Sci. 2014;5:439. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng Y, Wang Z. Protein accumulation in aleurone cells, sub-aleurone cells and the center starch endosperm of cereals. Plant. Cell Rep. 2014;33:1607–1615. doi: 10.1007/s00299-014-1651-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ibl V, Stoger E. The formation, function and fate of protein storage compartments in seeds. Protoplasma. 2012;249:379–392. doi: 10.1007/s00709-011-0288-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta M, Abu-Ghannam N, Gallaghar E. Barley for Brewing: Characteristic Changes during Malting, Brewing and Applications of its By-Products. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2010;9:318–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2010.00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.WAP. World AgriculturalProduction Circular Series, 14–31 (2019).

- 12.Hilscher J, Kapusi E, Stoger E, Ibl V. Cell layer-specific distribution of transiently expressed barley ESCRT-III component HvVPS60 in developing barley endosperm. Protoplasma. 2016;253:137–153. doi: 10.1007/s00709-015-0798-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ibl V, Kapusi E, Arcalis E, Kawagoe Y, Stoger E. Fusion, rupture, and degeneration: the fate of in vivo-labelled PSVs in developing barley endosperm. J. Exp. botany. 2014;65:3249–3261. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cameron-Mills V. Protein body formation in the developing barley endosperm. Carlsberg Res. Commun. 1980;45:577–576. doi: 10.1007/BF02932924. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roustan, V. et al. Microscopic and Proteomic Analysis of Dissected Developing Barley Endosperm Layers Reveals the Starchy Endosperm as Prominent Storage Tissue for ER-Derived Hordeins Alongside the Accumulation of Barley Protein Disulfide Isomerase (HvPDIL1-1). Front Plant Sci, 10.3389/fpls.2018.01248 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Shabrangy, A. et al. Using RT-qPCR, Proteomics, and Microscopy to Unravel the Spatio-Temporal Expression and Subcellular Localization of Hordoindolines Across Development in Barley Endosperm. Frontiers in Plant Science, 9, 10.3389/fpls.2018.00775 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Ibl Verena, Stoger Eva. Live Cell Imaging During Germination Reveals Dynamic Tubular Structures Derived from Protein Storage Vacuoles of Barley Aleurone Cells. Plants. 2014;3(3):442–457. doi: 10.3390/plants3030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cox J, Mann M. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26:1367–1372. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cox J, et al. Andromeda: a peptide search engine integrated into the MaxQuant environment. J. proteome Res. 2011;10:1794–1805. doi: 10.1021/pr101065j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tyanova S, et al. Visualization of LC-MS/MS proteomics data in MaxQuant. Proteom. 2015;15:1453–1456. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201400449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tyanova Stefka, Temu Tikira, Sinitcyn Pavel, Carlson Arthur, Hein Marco Y, Geiger Tamar, Mann Matthias, Cox Jürgen. The Perseus computational platform for comprehensive analysis of (prote)omics data. Nature Methods. 2016;13(9):731–740. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bielow C, Mastrobuoni G, Kempa S. Proteomics Quality Control: Quality Control Software for MaxQuant Results. J. proteome Res. 2016;15:777–787. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lohse M, et al. Mercator: a fast and simple web server for genome scale functional annotation of plant sequence data. Plant. Cell Env. 2014;37:1250–1258. doi: 10.1111/pce.12231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rigbolt Kristoffer T. G., Vanselow Jens T., Blagoev Blagoy. GProX, a User-Friendly Platform for Bioinformatics Analysis and Visualization of Quantitative Proteomics Data. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 2011;10(8):O110.007450. doi: 10.1074/mcp.O110.007450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Franceschini A, et al. STRING v9.1: protein-protein interaction networks, with increased coverage and integration. Nucleic acids Res. 2013;41:D808–D815. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deutsch EW, et al. The ProteomeXchange consortium in 2017: supporting the cultural change in proteomics public data deposition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D1100–D1106. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horvath H, et al. The production of recombinant proteins in transgenic barley grains. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U S Am. 2000;97:1914–1919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.030527497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wan Y, Lemaux PG. Generation of Large Numbers of Independently Transformed Fertile Barley Plants. Plant. Physiol. 1994;104:37–48. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teis D, Saksena S, Judson BL, Emr SD. ESCRT-II coordinates the assembly of ESCRT-III filaments for cargo sorting and multivesicular body vesicle formation. EMBO J. 2010;29:871–883. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sabelli PA, Larkins BA. The contribution of cell cycle regulation to endosperm development. Sex. Plant. Reprod. 2009;22:207–219. doi: 10.1007/s00497-009-0105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang R, et al. The Dynamics of Transcript Abundance during Cellularization of Developing Barley Endosperm. Plant. Physiol. 2016;170:1549–1565. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.01690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Samaj J, et al. Endocytosis, actin cytoskeleton, and signaling. Plant. Physiol. 2004;135:1150–1161. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.040683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Samaj J, Read ND, Volkmann D, Menzel D, Baluska F. The endocytic network in plants. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:425–433. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Latijnhouwers M, et al. Localization and domain characterization of Arabidopsis golgin candidates. J. Exp. Bot. 2007;58:4373–4386. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ibl V, Peters J, Stoger E, Arcalis E. Imaging the ER and Endomembrane System in Cereal Endosperm. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018;1691:251–262. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7389-7_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoh B, Hinz G, Jeong BK, Robinson DG. Protein storage vacuoles form de novo during pea cotyledon development. J. Cell Sci. 1995;108(Pt 1):299–310. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.1.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Korbei B, et al. Arabidopsis TOL proteins act as gatekeepers for vacuolar sorting of PIN2 plasma membrane protein. Curr. biology: CB. 2013;23:2500–2505. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adamowski M, et al. A Functional Study of AUXILIN-LIKE1 and 2, Two Putative Clathrin Uncoating Factors in Arabidopsis. Plant. Cell. 2018;30:700–716. doi: 10.1105/tpc.17.00785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zouhar J, Munoz A, Rojo E. Functional specialization within the vacuolar sorting receptor family: VSR1, VSR3 and VSR4 sort vacuolar storage cargo in seeds and vegetative tissues. Plant. J. 2010;64:577–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hatsugai N, Yamada K, Goto-Yamada S, Hara-Nishimura I. Vacuolar processing enzyme in plant programmed cell death. Front. Plant. Sci. 2015;6:234. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hara-Nishimura I, Kinoshita T, Hiraiwa N, Nishimura M. Vacuolar processing enzymes in protein-storage vacuoles and lytic vacuoles. J. Plant. Physiol. 1998;152:668–674. doi: 10.1016/S0176-1617(98)80028-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Radchuk V, et al. Vacuolar processing enzyme 4 contributes to maternal control of grain size in barley by executing programmed cell death in the pericarp. N. Phytol. 2018;218:1127–1142. doi: 10.1111/nph.14729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Y, et al. The vacuolar processing enzyme OsVPE1 is required for efficient glutelin processing in rice. Plant. J. 2009;58:606–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shimada T, Hiraiwa N, Nishimura M, Hara-Nishimura I. Vacuolar processing enzyme of soybean that converts proproteins to the corresponding mature forms. Plant. Cell Physiol. 1994;35:713–718. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a078648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shimada T, et al. Vacuolar processing enzymes are essential for proper processing of seed storage proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:32292–32299. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305740200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Katzmann DJ, Babst M, Emr SD. Ubiquitin-dependent sorting into the multivesicular body pathway requires the function of a conserved endosomal protein sorting complex, ESCRT-I. Cell. 2001;106:145–155. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00434-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Babst M, Katzmann DJ, Estepa-Sabal EJ, Meerloo T, Emr SD. Escrt-III: an endosome-associated heterooligomeric protein complex required for mvb sorting. Developmental Cell. 2002;3:271–282. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00220-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Babst M, Katzmann DJ, Snyder WB, Wendland B, Emr SD. Endosome-associated complex, ESCRT-II, recruits transport machinery for protein sorting at the multivesicular body. Developmental Cell. 2002;3:283–289. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00219-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hurley JH, Emr SD. The ESCRT complexes: structure and mechanism of a membrane-trafficking network. Annu. Rev. biophysics biomolecular structure. 2006;35:277–298. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.35.040405.102126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hurley JH, Hanson PI. Membrane budding and scission by the ESCRT machinery: it’s all in the neck. Nat. reviews. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010;11:556–566. doi: 10.1038/nrm2937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Buono Rafael Andrade, Leier André, Paez-Valencia Julio, Pennington Janice, Goodman Kaija, Miller Nathan, Ahlquist Paul, Marquez-Lago Tatiana T., Otegui Marisa S. ESCRT-mediated vesicle concatenation in plant endosomes. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2017;216(7):2167–2177. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201612040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Otegui MS. ESCRT-mediated sorting and intralumenal vesicle concatenation in plants. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2018;46:537–545. doi: 10.1042/BST20170439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yoshida K, et al. Studies on vacuolar membrane microdomains isolated from Arabidopsis suspension-cultured cells: local distribution of vacuolar membrane proteins. Plant. Cell Physiol. 2013;54:1571–1584. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pct107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Richardson LG, et al. Protein-Protein Interaction Network and Subcellular Localization of the Arabidopsis Thaliana ESCRT Machinery. Front. Plant. Sci. 2011;2:20. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2011.00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Finnie C, Melchior S, Roepstorff P, Svensson B. Proteome analysis of grain filling and seed maturation in barley. Plant. Physiol. 2002;129:1308–1319. doi: 10.1104/pp.003681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Finnie C, Andersen B, Shahpiri A, Svensson B. Proteomes of the barley aleurone layer: A model system for plant signalling and protein secretion. Proteom. 2011;11:1595–1605. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201000656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mock, H. P., Finnie, C., Witzel, K. & Svensson, B. Barley Proteomics. (2018).

- 58.Witzel K, et al. Plasma membrane proteome analysis identifies a role of barley membrane steroid binding protein in root architecture response to salinity. Plant. Cell Env. 2018;41:1311–1330. doi: 10.1111/pce.13154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tian L, Chou HL, Zhang L, Okita TW. Targeted Endoplasmic Reticulum Localization of Storage Protein mRNAs Requires the RNA-Binding Protein RBP-L. Plant. Physiol. 2019;179:1111–1131. doi: 10.1104/pp.18.01434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Crofts AJ, et al. Targeting of proteins to endoplasmic reticulum-derived compartments in plants. The importance of RNA localization. Plant. Physiol. 2004;136:3414–3419. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.048934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Crofts AJ, Crofts N, Whitelegge JP, Okita TW. Isolation and identification of cytoskeleton-associated prolamine mRNA binding proteins from developing rice seeds. Planta. 2010;231:1261–1276. doi: 10.1007/s00425-010-1125-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hamada S, et al. Dual regulated RNA transport pathways to the cortical region in developing rice endosperm. Plant. Cell. 2003;15:2265–2272. doi: 10.1105/tpc013821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hamada S, et al. The transport of prolamine RNAs to prolamine protein bodies in living rice endosperm cells. Plant. Cell. 2003;15:2253–2264. doi: 10.1105/tpc.013466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thomas C, Staiger CJ. A dynamic interplay between membranes and the cytoskeleton critical for cell development and signaling. Front. Plant. Sci. 2014;5:335. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Scheuring D, et al. Actin-dependent vacuolar occupancy of the cell determines auxin-induced growth repression. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:452–457. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1517445113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]