Abstract

Autonomic dysreflexia (AD) often occurs in individuals living with spinal cord injury (SCI) and is characterized by uncontrolled hypertension in response to otherwise innocuous stimuli originating below the level of the spinal lesion. Visceral stimulation is a predominant cause of AD in humans and effectively replicates the phenotype in rodent models of SCI. Direct assessment of sympathetic responses to viscerosensory stimulation in spinalized animals is challenging and requires invasive surgical procedures necessitating the use of anesthesia. However, administration of anesthesia markedly affects viscerosensory reactivity, and the effects are exacerbated following spinal cord injury (SCI). Therefore, the major goal of the present study was to develop a decerebrate rodent preparation to facilitate quantification of sympathetic responses to visceral stimulation in the spinalized rat. Such a preparation enables the confounding effect of anesthesia to be eliminated. Sprague-Dawley rats were subjected to SCI at the fourth thoracic segment. Four weeks later, renal sympathetic nerve activity (RSNA) responses to visceral stimuli were quantified in urethane/chloralose-anesthetized and decerebrate preparations. Visceral stimulation was elicited via colorectal distension (CRD) for 1 min. In the decerebrate preparation, CRD produced dose-dependent increases in mean arterial pressure (MAP) and RSNA and dose-dependent decreases in heart rate (HR). These responses were significantly greater in magnitude among decerebrate animals when compared with urethane/chloralose-anesthetized controls and were markedly attenuated by the administration of urethane/chloralose anesthesia after decerebration. We conclude that the decerebrate preparation enables high-fidelity quantification of neuronal reactivity to visceral stimulation in spinalized rats.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY In animal models commonly used to study spinal cord injury, quantification of sympathetic responses is particularly challenging due to the increased susceptibility of spinal reflex circuits to the anesthetic agents generally required for experimentation. This constitutes a major limitation to understanding the mechanisms mediating regionally specific neuronal responses to visceral activation in chronically spinalized animals. In the present study, we describe a spinalized, decerebrate rodent preparation that facilitates quantification of sympathetic reactivity in response to visceral stimuli following spinal cord injury. This preparation enables reliable and reproducible quantification of viscero-sympathetic reflex responses resembling those elicited in conscious animals and may provide added utility for preclinical evaluation of neuropharmacological agents for the management of autonomic dysreflexia.

Keywords: autonomic dysreflexia, decerebration, spinal cord injury, sympathetic, viscerosensory

INTRODUCTION

Distension of the colon and bladder can trigger specific reflex-sympathetic responses generally characterized by activation of visceral vasoconstrictor and sudomotor neurons and inhibition of cutaneous vasoconstrictor neural pathways (13). Integration of the reflex occurs at both the spinal and supraspinal levels (51). The mechanism mediating this reflex is of particular importance in the context of spinal cord injury (SCI). Among individuals living with SCI, visceral stimuli readily generate unopposed increases in sympathetic drive, which can acutely lead to life-threatening increases in blood pressure (7, 10, 12) and can have chronic detrimental effects to cardiac function (58). This phenomenon is called autonomic dysreflexia (AD) and is widely observed in subjects with cervical and high thoracic injuries, which leave sympathetic preganglionic neurons devoid of descending control from the brain stem and higher brain structures (21, 22, 55, 57). However, the mechanisms responsible for the pathogenesis of AD following SCI are currently not well understood.

In animal models commonly used to study SCI, quantification of sympathetic responses is particularly challenging due to the increased susceptibility of spinal reflex circuits to anesthetic agents, which are generally required for experimentation (6, 19, 46). This constitutes a major limitation to understanding the mechanisms mediating regionally specific neuronal responses to visceral activation in chronically spinalized animals. In the present study, we describe a spinalized, decerebrate rodent preparation that facilitates quantification of sympathetic reactivity in response to visceral stimuli following SCI. This preparation enables reliable and reproducible quantification of viscero-sympathetic reflex responses resembling those elicited in conscious animals and may provide added utility for preclinical evaluation of neuropharmacological agents for the management of AD. This preparation may be especially useful in determining spinal mechanisms mediating cardiovascular responses to visceral pain following SCI. Importantly, the decerebrate procedure renders the animal insentient, eliminating the need for injectable or inhalable anesthetics. Methods of decerebration have been successfully employed to study neuronal reflexes in rodent animal models previously (16, 27, 56); however, to our knowledge, this study represents the first attempt to utilize this technique to study neuronal reflexes in chronically spinalized rats. Our study also highlights the dampening effects of commonly used experimental anesthetics on sympathetic reflexes to visceral stimulation in spinalized animals.

METHODS

All protocols and surgical procedures employed in this study were reviewed and approved by the Wayne State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals endorsed by the American Physiological Society and published by the National Institutes of Health.

Design

The effect of anesthesia and its absence on the generation of viscero-sympathetic reflexes was studied in 16 male, spinalized, Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA). On day 0, animals were subjected to spinal cord transection of the fourth thoracic (T4) segment. Thirty days later, animals were randomized into urethane/chloralose-anesthetized (n = 8) or decerebrate (n = 8) groups. Heart rate (HR) and mean arterial pressure (MAP), as well as renal sympathetic nerve activity (RSNA) responses, were measured during viscero-sympathetic reflex activation. Three additional, spinal-intact, decerebrate animals were used to compare the effects of spinalization on RSNA frequency domain profiles and coherence between RSNA and arterial blood pressure.

Procedures and Measurements

T4 spinal cord transection.

On day 0, the average animal weight was 369 ± 21 g. The SCI surgery was performed as described previously (17, 23, 27, 38, 49), with minor modifications. Briefly, animals were anesthetized with 3% isoflurane. Once anesthetic depth was confirmed by the absence of paw withdrawal and corneal reflexes, isoflurane was reduced and maintained at 1.5–2.5% throughout the surgery. Rectal temperature was monitored continuously and maintained at 37.0°C using a homeothermic blanket (Physio Suite; Kent Scientific, Torrington, CT). Carprofen (5 mg/kg) and lidocaine (0.5 mg/kg) were administered subcutaneously, and animals were prepared for aseptic survival surgery according to the Handbook for Laboratory Animal Care and Use.

A skin incision overlaying the T2–T5 vertebral segments was made. Dorsal laminectomy between T3 and T4 vertebral segments was performed. The dura mater was excised, and the exposed spinal cord was completely transected using microscissors. Transection was deemed complete following visual confirmation that the spinal cord stumps retracted, and a gap of ∼1–2 mm was created, in which no spinal tissue remained. Overlaying muscle and skin incisions were closed using a 3-0 suture and wound clips (Roboz Surgical Instruments), respectively. Animals were allowed to recover in a temperature-controlled chamber for 7 days (Techniplast, West Chester, PA) before being returned to the animal facility. Animals received Carprofen postoperatively (5 mg/kg) for 3 days and Baytril antibiotic (10 mg/kg) for 10 days to prevent bladder infections. Bladders were expressed twice daily for 2 wk to initiate micturition. Food pellets and water were provided ad libitum. Animals were also given cereal and fruit chucks to prevent weight loss.

Acute terminal electrophysiology experiment.

On day 30, the average animal weight was 486 ± 28 g. Anesthesia was induced with 3% isoflurane and maintained with 1–2% isoflurane during instrumentation. Rectal temperature was monitored continuously and maintained at 37°C via a water circulating blanket (Stryker; Kent Scientific). Animals were spontaneously ventilated. The left femoral artery and vein were cannulated using PE50 tubing for blood pressure monitoring and infusion of drugs, respectively. Electrocardiogram (ECG) lead wires were inserted subcutaneously. The ECG signal was acquired using a Grass P511 differential preamplifier and a high-impedance probe HIP 511GA. The signal was digitized using Micro 1401-3 and Spike2 software (Cambridge Electronic Designs, Cambridge UK). Measurement of RSNA was performed similarly, as described previously (36, 37). The left renal nerve bundle was accessed via a left retroperitoneal incision, isolated, and cut distally to minimize interference of afferent signal. The nerve was placed on a bipolar hook electrode. Electrodes and nerves were embedded in gel (Bisico), the wound was closed, and the wires exteriorized. Following instrumentation, animals either were switched to an intravenous infusion of urethane/chloralose or underwent the decerebration procedure. In both groups, isoflurane was discontinued, and animals were allowed to recover for 1 h before initiation of the experimental protocol. The dose of urethane/chloralose (urethane 100 mg·kg−1·h−1 plus chloralose 10 mg·kg−1·h−1) used for the current study was selected from pilot experiments where the anesthetic regimen was titrated. This dose is one-fifth of the dose we routinely use when studying cardiovascular reflex responses in animals with an intact neuraxis (36, 37). Adequate depth of anesthesia was assessed by forelimb pinch, which in this model results in twitching and paw withdrawal response.

Renal Sympathetic Nerve Activity Recording

Neural signals were initially amplified 10,000 times using a Grass P511 differential preamplifier and a high-impedance probe HIP 511GA with a filter setting of 30–1,000 Hz. The signal was digitized using Micro 1401-3 and Spike2 software (Cambridge Electronic Designs). Background noise was determined after the animal was euthanized. Background noise was subtracted offline before data analyses. Resting nerve activity was normalized to 100% (15).

Decerebration

Decerebration was performed as described previously (8, 16, 27, 50, 53) with minor but important adjustments described below. To minimize bleeding, carotid arteries were temporarily occluded using aneurysm clips, which were removed following the procedure. The fully instrumented animals were placed in a stereotaxic frame (Kopf Instruments), with the animals’ lower body positioned below the level of the head. Bilateral craniotomy was performed by shaving of the skull area between the sagittal and lambdoid sutures, taking care not to disrupt the superior sagittal sinus. The dura matter was breached, and the dorsal aspects of the cortex were gently aspirated until the vertebral artery and the rostral edge of the superior and inferior colliculi were visible. Using a blunt instrument, we transected the brain precollicularly, and all central nervous system (CNS) structures rostral and lateral to the transection were aspirated. Transection led to a small drop in blood pressure that was countered by decreasing the inspired isoflurane. The cavity was packed with cotton balls (Ethicon; Johnson & Johnson) soaked in mineral oil, and saline soaked gauze was placed over the skull. The aneurysm clips were removed. Isoflurane was discontinued, and a minimum recovery of 1 h was employed, which was determined adequate for the effects of isoflurane to wear off (26, 27).

Colorectal Distension

Colorectal distension (CRD) was induced by inflation of an 8 French latex, fluid-filled balloon catheter (Covidien, Dublin, Ireland) which was inserted 2 cm past the anal verge, as described previously by others (34, 42). This is an effective and reproducible means of eliciting viscero-sympathetic reflexes (34, 42). The catheter was secured to the tail to prevent retraction. CRD was initiated over several seconds and maintained for 1 min.

Data Acquisition and Analyses

Data acquisition.

Arterial blood pressure was sampled at 100 Hz, whereas ECG and RSNA were sampled at 1,000 Hz. HR was derived from R-R interval, which was calculated based on the ECG signal. Raw RSNA was subject to offline rectification and integration over 1.0 s for time domain analyses and 0.02 s for frequency domain analysis.

Data analyses.

Baseline hemodynamic data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test when appropriate. Average data were expressed as described previously (18). Average hemodynamic data were expressed as a maximum change during CRD from baseline levels (average of 5 min) immediately before CRD. Rectified and integrated RSNA signals were expressed as maximum percent changes from baseline levels (average of 5 min) immediately before CRD. Average data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA to compare the effects of CRD volume and experimental condition. Tukey’s post hoc test was performed when appropriate. Frequency domain analyses were performed on ∼5 min of arterial blood pressure and RSNA data. The data were smoothed using Gaussian filter function, allowing for frequencies >30 Hz to be excluded. We used the power spectral density (or power spectrum) to quantify the frequency content of a time series Xj (i.e., blood pressure or RSNA), defined as

where and A(τ) is the autocorrelation function:

The coherence measures the correlation of two time series Xj and Yj as a function of frequency:

where

Note that 0 ≤ Coh(ω) ≤ 1. This was calculated at Matlab, with the function mscohere using a hanning window size of 100.

Experimental Controls

HR, MAP, and RSNA responses to CRD were measured in urethane/chloralose-anesthetized animals and unanesthetized, decerebrate preparations 30 days following spinal cord transection. Dextrose (5%) was administered intravenously to all animals to maintain fluid homeostasis. Brief phenylephrine challenge (40 μg/kg iv) was used to test baroreflex activity following decerebration. Animals lacking baroreflex responses to phenylephrine challenge were excluded from the study (n = 1). The stability of the preparation was assessed by monitoring baseline blood pressure and heart rate levels throughout the experiment. To further assess the effect of anesthesia in this preparation, cardiovascular and sympathetic responses to CRD were also measured in decerebrate animals following administration of urethane/chloralose (27). To determine the effect of spinalization on RSNA firing frequency and RSNA-arterial blood pressure coherence, frequency domain and coherence analysis were conducted using data from three spinal-intact and three spinalized decerebrate animals. Hexamethonium (20 mg/kg) was administered intravenously to evaluate the effect of ganglionic blockade on baseline sympathetic and hemodynamic values in decerebrate animals.

RESULTS

Baseline HR and blood pressure values for urethane/chloralose-anesthetized animals and for decerebrate animals before and after urethane/chloralose administration are presented in Table 1. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc analysis revealed significant differences in HR across all groups. HR was significantly increased in decerebrate animals when compared with urethane/chloralose-anesthetized animals or to decerebrate animals following urethane/chloralose administration (P < 0.05). Arterial pressure values were not significantly different in decerebrate animals when compared with the urethane/chloralose-anesthetized group; however, administration of anesthesia to decerebrate animals significantly lowered systolic blood pressure (P < 0.05). Baseline nerve activity ± SD was 1.026 ± 0.863, 1.973 ± 1.087, and 1.621 ± 0.932 µV/200 ms for urethane/chloralose-anesthetized, decerebrate, and decerebrate following urethane/chloralose, respectively. Administration of urethane/chloralose anesthesia in decerebrate animals reduced baseline RSNA by 8.6 ± 4.4%, which was not statistically significant.

Table 1.

Effect of preparation on baseline arterial blood pressure and HR values

| HR, beats/min | MAP, mmHg | SBP, mmHg | DBP, mmHg | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urethane/chloralose | 372 ± 29# | 65 ± 5 | 92 ± 9# | 54 ± 7 |

| Decerebrate | 413 ± 37*# | 64 ± 4 | 93 ± 6# | 59 ± 5 |

| Decerebrate + urethane/chloralose | 270 ± 11* | 60 ± 3 | 77 ± 4 | 52 ± 2 |

Values are means ± SD. DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HR, heart rate; MAP, mean arterial pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure. Decerebration (n = 7) increases HR and has minimal effect on blood pressure. Administration of urethane/chloralose in decerebrate rats decreased blood pressure and HR. Data were analyzed using 1-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test.

P < 0.05 vs. urethane/chloralose (n = 8);

P < 0.05 vs. decerebrate + urethane/chloralose (n = 7).

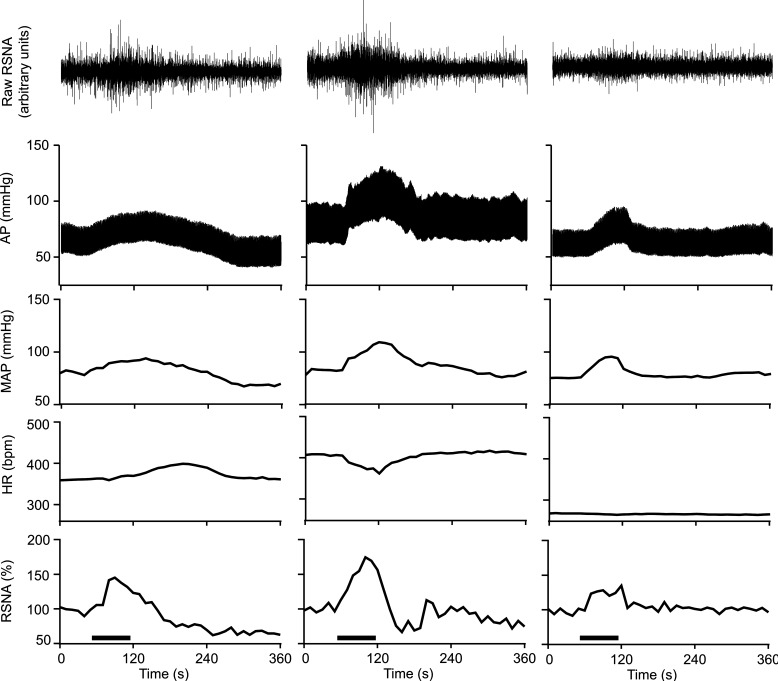

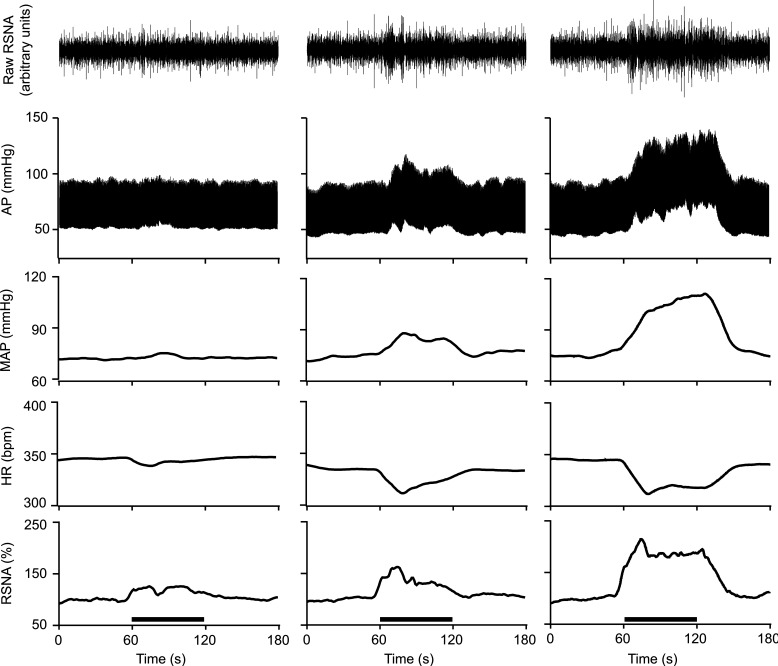

Representative examples of hemodynamic and RSNA responses to 2 ml of CRD are provided in Fig. 1. Figure 1, left, depicts the responses in one urethane/chloralose-anesthetized animal, whereas Fig. 1, middle and right, depict responses in one decerebrate animal before and after urethane/chloralose administration, respectively. In general, urethane/chloralose-anesthetized animals responded to CRD with increases in MAP and RSNA and delayed changes in HR. In decerebrate animals, CRD produced bradycardia and more robust increases in MAP and RSNA. Administration of urethane/chloralose in decerebrate animals markedly lowered baseline HR and virtually abolished bradycardiac responses. In all instances, baseline RSNA, heart rate, and blood pressure returned to pre-CRD values following cessation of the stimulus. Graded CRD revealed dose dependent effects in decerebrate animals (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Representative examples of heart rate (HR), mean arterial pressure (MAP), and renal sympathetic nerve activity (RSNA) responses to 2 ml of colorectal distension in 1 urethane/chloralose-anesthetized animal (left) and 1 decerebrate animal before (middle) and after (right) administration of urethane/chloralose anesthesia. Colorectal distension (1 min) is indicated by the horizontal line above the time axis (bottom). Decerebrate preparation exhibits more robust blood pressure and RSNA responses to colorectal distension, which are accompanied by bradycardia. AP, arterial pressure.

Fig. 2.

Representative examples of heart rate (HR), mean arterial pressure (MAP), and renal sympathetic nerve activity (RSNA) responses to 0.5 (left), 1.0 (middle), and 2.0 ml (right) colorectal distension in 1 decerebrate, spinalized animal. Colorectal distension (1 min) is indicated by the horizontal line above the time axis (bottom). Decerebrate preparation enables dose-dependent responses to colorectal distension to be evaluated in spinalized animals without the confounds of anesthesia. AP, arterial pressure.

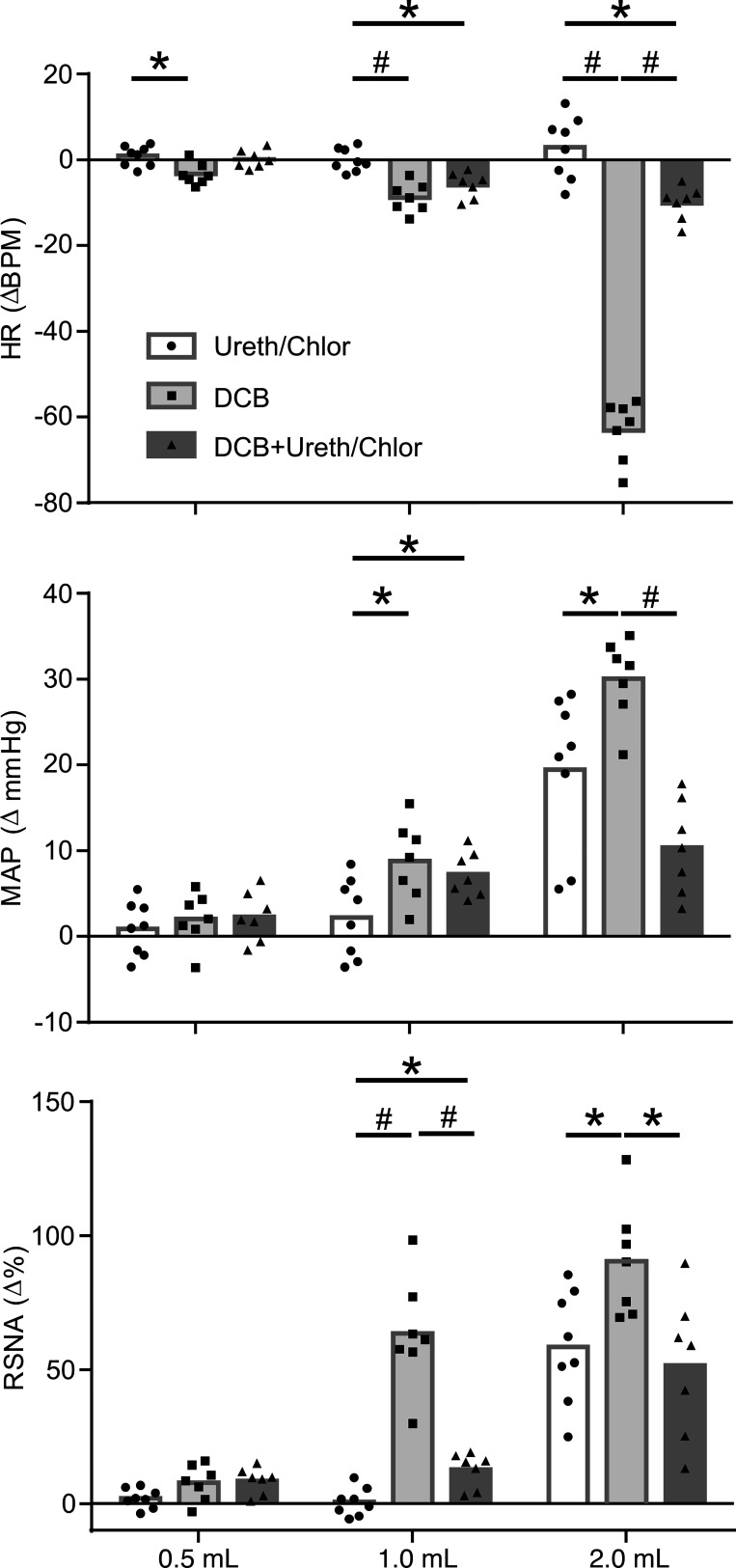

Average responses to graded colorectal distention in urethane/chloralose-anesthetized animals and in decerebrate animals before and after urethane/chloralose administration are compared in Fig. 3. When compared with decerebrate rats, urethane/chloralose anesthetized animals and exhibited attenuated reactivity to visceral stimulation and significantly blunted responses to the maximal stimulation of 2 ml. The addition of anesthesia to decerebrate animals similarly attenuated responses to visceral stimulation.

Fig. 3.

Average data showing maximum changes in heart rate [HR; beats/min (BPM)], mean arterial pressure (MAP), and renal sympathetic nerve activity (RSNA) during graded colorectal distension (CRD). ●, Urethane/chloralose-anesthetized animals (n = 8); ■, decerebrate animals (n = 7); ▲, decerebrate animals following administration of urethane/chloralose anesthesia (n = 7). Data were analyzed using 2-way ANOVA, followed by 1-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc test of all pairwise comparisons for a given CRD volume. *P < 0.05; #P < 0.01.

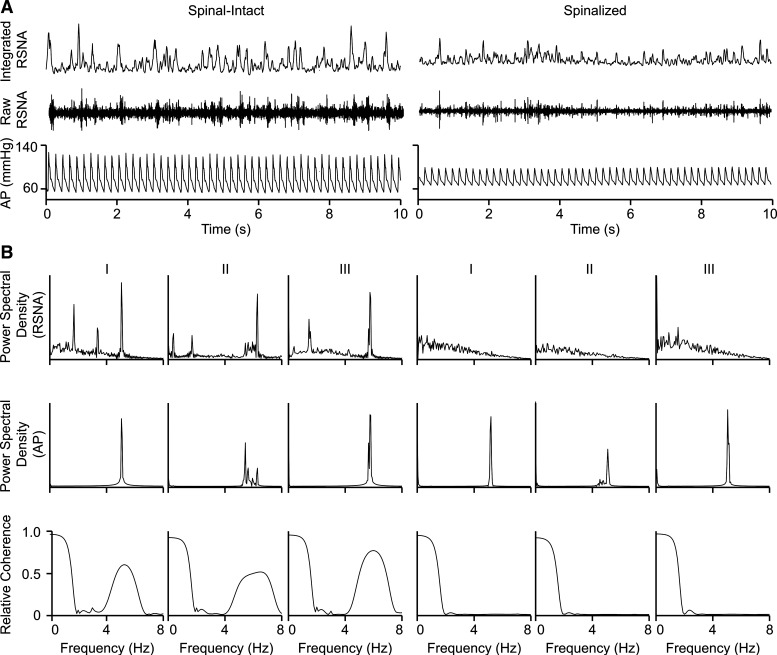

Figure 4 shows a representative neurogram and arterial blood pressure tracings from a spinal-intact decerebrate and a spinalized, decerebrate animal. Animals with an intact neuraxis showed clustered RSNA firing, the occurrence of which is related to the cardiac cycle. Clustered RSNA firing is markedly diminished in spinalized, decerebrate animals. Figure 4, bottom, shows power spectral density of arterial blood pressure and RSNA signals from three spinal-intact decerebrate animals and three spinalized, decerebrate animals. Arterial blood pressure power spectra showed a prominent frequency band between 4 and 8 Hz, apparently with sharp peaks, which correspond to the cardiac cycle. Power spectra of RSNA in the spinal-intact decerebrate animals showed a prominent frequency between 4 and 8 Hz as well as additional frequency peaks between 0 and 3 Hz. All RSNA frequencies were absent in the spinalized, decerebrate animals. Coherence of arterial blood pressure and RSNA power spectra showed coupling between 4 and 8 Hz in spinal-intact animals, which was not observed in spinalized animals.

Fig. 4.

A: representative tracings of arterial pressure (AP) and renal sympathetic nerve activity (RSNA) in 1 decerebrate spinal-intact and 1 decerebrate, spinalized animal. B: power spectral densities of resting arterial pressure (top) and RSNA (middle) and coherence of AP and RSNA (bottom) form 3 decerebrate spinal-intact and 3 decerebrate spinalized animals. Strong coherence of AP-RSNA between 4 and 8 Hz (corresponding to the cardiac cycle) observed in spinal-intact decerebrate animals is absent in spinalized, decerebrate animals.

DISCUSSION

The major goal of the present study was to develop a decerebrate rodent preparation to facilitate direct assessment of viscero-sympathetic reactivity in spinalized rats. The central finding is that sympathetic reactivity in the spinalized animal is highly influenced by the presence of anesthesia. In accord with this, the reflex reactivity was greater in decerebrate, unanesthetized animals than in urethane/chloralose anesthetized animals and resembles those animals obtained in conscious preparations (34, 49). The results suggest that the use of a decerebrate, spinalized rodent model to study AD following SCI is superior to animal models requiring the use of anesthesia.

Decerebration Procedure

To render animals insentient and allow for discontinuation of anesthesia, we utilized precollicular decerebration consistent with what we and others have used previously (16, 26, 27). Although other models of decerebration involving different degrees of CNS tissue removal exist, the method presented herein is conservative, which improves the stability of the preparation. Spinalized animals are inherently unstable, and responses that usually result in minor and short-acting cardiovascular effects in intact animals, such as phenylephrine challenge or volume administration, have much greater effects following SCI (11, 14, 17). Importantly, precollicular (versus postcollicular) decerebration ensures that cardiovascular integrative centers in the medulla oblongata are not disturbed, as Hayashi (16) showed for exercise pressor reflex activation. Spontaneous hindlimb motor activity, which can occur in decerebrate preparations, presents minimal issues in spinalized animals, as spinal cord transection disrupts descending locomotor drive. An alternative approach for the removal of anesthetics is the in situ working heart-brain stem preparation (47, 48). This preparation is particularly useful for studying viscero-sympathetic reflexes. However, the use of this preparation seems to be restricted to young, naïve animals and might not be suitable for studies in chronically spinalized animals.

To ensure the success of this preparation in spinalized animals, modifications to standard decerebration procedures (26, 27, 53) were employed and have been described herein. Attenuation of blood loss associated with decerebration is critical, as spinalized animals are generally hypotensive (24, 34). The temporary application of aneurysm clips to the carotid arteries bilaterally minimized blood loss and had no effect on baroreflex control. Average decrease in heart rate in response to phenylephrine challenge among the seven barosensitive, unanesthetized, decerebrate animals was 30 ± 8 beats/min. One animal was removed from the study, as it displayed no baroreflex sensitivity following decerebration. Positioning of the animal’s body below the head also decreased blood loss, as did initial aspiration of the cortical tissue, followed by the removal of precollicular subcortical structures. Continuous blood pressure monitoring allowed for decreases in blood pressure to be effectively countered by decreasing levels of inspired isoflurane, as reported by Dobson and Harris (8). As a result, abrupt and sudden decreases in blood pressure during execution of the decerebration procedure were prevented. Tight packing of the cranial cavity with cotton balls soaked in high-density mineral oil further prevented blood loss following removal of the aneurysm clip.

Viscero-Sympathetic Reflex Reactivity in Decerebrate Animals

Visceral stimulation in decerebrate animals led to increases in RSNA and MAP, which were accompanied by decreases in HR. This pattern is similar to what is reported in human subjects (3, 4, 25, 30). Reflex reactivity is attenuated by the administration of anesthesia and abolished by ganglionic blockade. These data are in line with others’ observations using colorectal stimulation (41, 42, 44–46). Enhanced reflex reactivity to visceral stimuli in naïve (i.e., nonspinalized) decerebrate animals has been demonstrated before (42, 43). Naïve decerebrate animals displayed reflex reactivity similar to awake animals, and anesthetics posed an obstacle when quantifying these reflexes (40). The current study highlights the utility of the decerebrate preparation for obtaining direct measurements of efferent sympathetic nerve activity in response to viscerosensory stimulation in spinalized rats. The magnitude of the responses demonstrated in this study compared with those previously reported are difficult to compare, as different methods of visceral stimulation as well as different sexes and species were used. Nonetheless, the magnitude of the responses obtained in the preparation assessed in this study is within the range of what others have reported (42, 46). Graded colorectal stimulation yielded dose-dependent responses, with 2 ml of CRD producing hemodynamic effects that can be characterized as AD. Anesthetized animals showed virtually no responses to mild CRD, and 2 ml of CRD did not produce AD-like responses in all animals. Because of this, in a subset of spinalized, anesthetized rats, we performed 3 ml of CRD. Greater CRD volumes (e.g., 3 ml) in anesthetized animals produced greater effects (data not shown) but were associated with colorectal tissue damage. The precise mechanism by which urethane/chloralose dampens viscero-sympathetic reactivity in spinalized animals remains unclear. Urethane/chloralose anesthesia is routinely used in studies of visceral and cardiovascular reflexes in naïve animals (31–33, 52); however, these anesthetic agents have consistently been shown to dampen reflex responsiveness mediating, for example, reductions in baroreflex gain (9, 52).

Hemodynamic and Sympathetic Parameters Following SCI

Spinalized, decerebrate animals exhibit hypotension with average systolic blood pressures of 90 mmHg, which is similar to what others have reported in conscious animals (24, 28). High thoracic SCI (e.g., T4) results in decentralization of sympathetic preganglionic neurons below the level of the injury and the reduction of tonic vasocontrictor drive originating from below the level of the spinal lesion. Previous studies indicate that sympathetic drive originating from above the level of a thoracic spinal transection is increased following the injury (28, 29). Lujan and colleagues (28, 29) previously demonstrated that ganglionic blockade reduced cardiac sympathetic drive and cardiac output in spinalized animals. In the spinalized, decerebrate preparation described herein, ganglionic blockade (20 mg/kg hexamethonium) decreased mean arterial pressure by 27 ± 8 mmHg. It is tempting to speculate that, following SCI, elimination of both 1) regional sympathetic drive originating from above the spinal lesion and 2) spinally governed sympathetic drive originating from below the spinal transection contribute to the observed decreases in blood pressure in response to ganglionic blockade. The effect of SCI on sympathetic discharge and blood pressure variability is seen in Fig. 4, demonstrating the ability of the preparation to serve as a reliable model. Previous reports indicate that coordinated intersegmental firing of sympathetic nerves is absent in spinalized cats and rats when measured under anesthetized conditions (1, 54). The presently described decerebrate preparation supports this observation in the absence of anesthesia. Coherence analyses revealed a broad peak between 4 and 8 Hz, which is abolished following SCI. The 4- to 8-Hz frequency is associated with the cardiac cycle, and its physiological significance has been linked with maintenance of vasoconstrictor tone (39). Low frequencies (∼0.4 Hz) of RSNA were detected in some of the spinal-intact decerebrate animals. Although some do report a low-frequency domain of RSNA (2, 20, 35), Taylor and Schramm (54) showed that the presence of a low-frequency domain of RSNA is inconstant. Vasocontrictor drive originating above the level of the injury (i.e., to the heart) is maintained and likely increased to compensate for systemic hypotension (e.g., animals become tachycardic) in the chronic stages of SCI (29). Decerebrate animals exhibited tachycardia, with HR exceeding 400 beats/min, and administration of urethane/chloralose to decerebrate animals markedly lowered HR. This suggests that urethane/chloralose anesthesia influences autonomic control to the heart in spinalized, decerebrate animals and may partially explain the masking of bradycardiac responses to visceral stimulation. Nevertheless, it is likely that the attenuated pressor responses contribute to the reduced reflex bradycardia observed in response to CRD following administration of urethane/chloralose.

In summary, we describe a straightforward means for eliminating the confounding effects of anesthesia for direct measurement of regional sympathetic nerve activity in spinalized rats. Direct and reliable measurement of sympathetic nerve activity and hemodynamic responses to visceral stimulation is important, as both noxious and innocuous visceral stimuli can trigger hypertensive episodes associated with AD. This preparation may provide valuable insight into the mechanisms mediating viscero-sympathetic reactivity following SCI, thereby facilitating translation to the human condition. Moreover, it may enable neural pathways by which visceral pain exerts cardiovascular effects in different disease states to be explored, such as neuropathic pain (5).

Limitations of the Preparation

Limitations of the decerebrate preparation are noted. It is not entirely analogous to the conscious state, and the role of cortical structures in modulating viscero-sympathetic reflex cannot be studied, as these structures are removed during the decerebration procedure. In this preparation, sympathetic nerves are cut distally to improve signal quality and minimize afferent signal interference. It is possible that afferent fibers arising from the kidney modulate efferent RSNA at the level of the spinal cord. This being stated, the potential role of renal afferent neurons in modulating RSNA reflex reactivity to CRD could be explored by leaving the renal nerves intact.

GRANTS

This work was supported, in part, by funds from the Department of Emergency Medicine Munuswamy Dayanandan Endowment, the Cardiovascular Research Institute, and the Office of the Vice President for Research, Wayne State University.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.R. and Z.M. conceived and designed research; C.R., C.L., and Z.M. performed experiments; C.R. and Z.M. analyzed data; C.R. and Z.M. interpreted results of experiments; C.R., C.L., and Z.M. prepared figures; C.R. and Z.M. drafted manuscript; C.R., D.S.O., C.L., S.A.S., and Z.M. edited and revised manuscript; C.R., D.S.O., C.L., S.A.S., and Z.M. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ardell JL, Barman SM, Gebber GL. Sympathetic nerve discharge in chronic spinal cat. Am J Physiol 243: H463–H470, 1982. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1982.243.3.H463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown DR, Brown LV, Patwardhan A, Randall DC. Sympathetic activity and blood pressure are tightly coupled at 0.4 Hz in conscious rats. Am J Physiol 267: R1378–R1384, 1994. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.267.5.R1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown R, Engel S, Wallin BG, Elam M, Macefield V. Assessing the integrity of sympathetic pathways in spinal cord injury. Auton Neurosci 134: 61–68, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cameron AA, Smith GM, Randall DC, Brown DR, Rabchevsky AG. Genetic manipulation of intraspinal plasticity after spinal cord injury alters the severity of autonomic dysreflexia. J Neurosci 26: 2923–2932, 2006. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4390-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cervero F, Laird JM. Understanding the signaling and transmission of visceral nociceptive events. J Neurobiol 61: 45–54, 2004. doi: 10.1002/neu.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins JG, Kawahara M, Homma E, Kitahata LM. Alpha-chloralose suppression of neuronal activity. Life Sci 32: 2995–2999, 1983. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(83)90651-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunningham DJ, Guttmann L, Whitteridge D, Wyndham CH. Cardiovascular responses to bladder distension in paraplegic patients. J Physiol 121: 581–592, 1953. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1953.sp004966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dobson KL, Harris J. A detailed surgical method for mechanical decerebration of the rat. Exp Physiol 97: 693–698, 2012. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2012.064840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fluckiger JP, Sonnay M, Boillat N, Atkinson J. Attenuation of the baroreceptor reflex by general anesthetic agents in the normotensive rat. Eur J Pharmacol 109: 105–109, 1985. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(85)90545-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao SA, Ambring A, Lambert G, Karlsson AK. Autonomic control of the heart and renal vascular bed during autonomic dysreflexia in high spinal cord injury. Clin Auton Res 12: 457–464, 2002. doi: 10.1007/s10286-002-0068-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goshgarian HG. The crossed phrenic phenomenon: a model for plasticity in the respiratory pathways following spinal cord injury. J Appl Physiol (1985) 94: 795–810, 2003. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00847.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guttmann L, Whitteridge D. Effects of bladder distension on autonomic mechanisms after spinal cord injuries. Brain 70: 361–404, 1947. doi: 10.1093/brain/70.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Häbler HJ, Hilbers K, Jänig W, Koltzenburg M, Kümmel H, Lobenberg-Khosravi N, Michaelis M. Viscero-sympathetic reflex responses to mechanical stimulation of pelvic viscera in the cat. J Auton Nerv Syst 38: 147–158, 1992. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(92)90234-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hains BC, Saab CY, Waxman SG. Changes in electrophysiological properties and sodium channel Nav1.3 expression in thalamic neurons after spinal cord injury. Brain 128: 2359–2371, 2005. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hart EC, Head GA, Carter JR, Wallin BG, May CN, Hamza SM, Hall JE, Charkoudian N, Osborn JW. Recording sympathetic nerve activity in conscious humans and other mammals: guidelines and the road to standardization. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 312: H1031–H1051, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00703.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayashi N. Exercise pressor reflex in decerebrate and anesthetized rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 284: H2026–H2033, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00400.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hou S, Duale H, Cameron AA, Abshire SM, Lyttle TS, Rabchevsky AG. Plasticity of lumbosacral propriospinal neurons is associated with the development of autonomic dysreflexia after thoracic spinal cord transection. J Comp Neurol 509: 382–399, 2008. doi: 10.1002/cne.21771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ichinose TK, Minic Z, Li C, O’Leary DS, Scislo TJ. Activation of NTS A(1) adenosine receptors inhibits regional sympathetic responses evoked by activation of cardiopulmonary chemoreflex. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 303: R539–R550, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00164.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jinks SL, Martin JT, Carstens E, Jung SW, Antognini JF. Peri-MAC depression of a nociceptive withdrawal reflex is accompanied by reduced dorsal horn activity with halothane but not isoflurane. Anesthesiology 98: 1128–1138, 2003. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200305000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Julien C, Chapuis B, Cheng Y, Barrès C. Dynamic interactions between arterial pressure and sympathetic nerve activity: role of arterial baroreceptors. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 285: R834–R841, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00102.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karlsson AK. Autonomic dysreflexia. Spinal Cord 37: 383–391, 1999. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krassioukov A, Warburton DE, Teasell R, Eng JJ; Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence Research Team . A systematic review of the management of autonomic dysreflexia after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 90: 682–695, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krassioukov AV, Johns DG, Schramm LP. Sensitivity of sympathetically correlated spinal interneurons, renal sympathetic nerve activity, and arterial pressure to somatic and visceral stimuli after chronic spinal injury. J Neurotrauma 19: 1521–1529, 2002. doi: 10.1089/089771502762300193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krassioukov AV, Weaver LC. Episodic hypertension due to autonomic dysreflexia in acute and chronic spinal cord-injured rats. Am J Physiol 268: H2077–H2083, 1995. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.5.H2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krenz NR, Meakin SO, Krassioukov AV, Weaver LC. Neutralizing intraspinal nerve growth factor blocks autonomic dysreflexia caused by spinal cord injury. J Neurosci 19: 7405–7414, 1999. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07405.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leal AK, Williams MA, Garry MG, Mitchell JH, Smith SA. Evidence for functional alterations in the skeletal muscle mechanoreflex and metaboreflex in hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295: H1429–H1438, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01365.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Llewellyn-Smith IJ, Weaver LC. Changes in synaptic inputs to sympathetic preganglionic neurons after spinal cord injury. J Comp Neurol 435: 226–240, 2001. doi: 10.1002/cne.1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lujan HL, DiCarlo SE. T5 spinal cord transection increases susceptibility to reperfusion-induced ventricular tachycardia by enhancing sympathetic activity in conscious rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H3333–H3339, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01019.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lujan HL, Janbaih H, DiCarlo SE. Dynamic interaction between the heart and its sympathetic innervation following T5 spinal cord transection. J Appl Physiol (1985) 113: 1332–1341, 2012. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00522.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Macefield VG, Burton AR, Brown R. Somatosympathetic vasoconstrictor reflexes in human spinal cord injury: responses to innocuous and noxious sensory stimulation below lesion. Front Physiol 3: 215, 2012. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maggi CA, Meli A. Suitability of urethane anesthesia for physiopharmacological investigations in various systems. Part 1: General considerations. Experientia 42: 109–114, 1986. doi: 10.1007/BF01952426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maggi CA, Meli A. Suitability of urethane anesthesia for physiopharmacological investigations in various systems. Part 2: Cardiovascular system. Experientia 42: 292–297, 1986. doi: 10.1007/BF01942510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maggi CA, Meli A. Suitability of urethane anesthesia for physiopharmacological investigations. Part 3: Other systems and conclusions. Experientia 42: 531–537, 1986. doi: 10.1007/BF01946692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maiorov DN, Weaver LC, Krassioukov AV. Relationship between sympathetic activity and arterial pressure in conscious spinal rats. Am J Physiol 272: H625–H631, 1997. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.2.H625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malpas SC, Burgess DE. Renal SNA as the primary mediator of slow oscillations in blood pressure during hemorrhage. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 279: H1299–H1306, 2000. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.3.H1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Minic Z, Li C, O’Leary DS, Scislo TJ. Severe hemorrhage attenuates cardiopulmonary chemoreflex control of regional sympathetic outputs via NTS adenosine receptors. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 307: H904–H909, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00234.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Minic Z, O’Leary DS, Scislo TJ. NTS adenosine A2a receptors inhibit the cardiopulmonary chemoreflex control of regional sympathetic outputs via a GABAergic mechanism. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 309: H185–H197, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00838.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Minic Z, Zhang Y, Mao G, Goshgarian HG. Transporter protein-coupled DPCPX nanoconjugates induce diaphragmatic recovery after SCI by blocking adenosine A1 receptors. J Neurosci 36: 3441–3452, 2016. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2577-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Montano N, Furlan R, Guzzetti S, McAllen RM, Julien C. Analysis of sympathetic neural discharge in rats and humans. Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci 367: 1265–1282, 2009. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2008.0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ness TJ. Models of visceral nociception. ILAR J 40: 119–128, 1999. doi: 10.1093/ilar.40.3.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ness TJ, Gebhart GF. Characterization of neurons responsive to noxious colorectal distension in the T13-L2 spinal cord of the rat. J Neurophysiol 60: 1419–1438, 1988. doi: 10.1152/jn.1988.60.4.1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ness TJ, Gebhart GF. Colorectal distension as a noxious visceral stimulus: physiologic and pharmacologic characterization of pseudaffective reflexes in the rat. Brain Res 450: 153–169, 1988. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91555-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ness TJ, Gebhart GF. Visceral pain: a review of experimental studies. Pain 41: 167–234, 1990. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(90)90021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ness TJ, Piper JG, Follett KA. The effect of spinal analgesia on visceral nociceptive neurons in caudal medulla of the rat. Anesth Analg 89: 721–726, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ness TJ. Intravenous lidocaine inhibits visceral nociceptive reflexes and spinal neurons in the rat. Anesthesiology 92: 1685–1691, 2000. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200006000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Osborn JW, Taylor RF, Schramm LP. Chronic cervical spinal cord injury and autonomic hyperreflexia in rats. Am J Physiol 258: R169–R174, 1990. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1990.258.1.R169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pickering AE, Paton JF. A decerebrate, artificially-perfused in situ preparation of rat: utility for the study of autonomic and nociceptive processing. J Neurosci Methods 155: 260–271, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Potts JT, Spyer KM, Paton JF. Somatosympathetic reflex in a working heart-brainstem preparation of the rat. Brain Res Bull 53: 59–67, 2000. doi: 10.1016/S0361-9230(00)00309-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramer LM, van Stolk AP, Inskip JA, Ramer MS, Krassioukov AV. Plasticity of TRPV1-expressing sensory neurons mediating autonomic dysreflexia following spinal cord injury. Front Physiol 3: 257, 2012. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sapru HN, Krieger AJ. Procedure for the decerebration of the rat. Brain Res Bull 3: 675–679, 1978. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(78)90016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sato A, Schmidt RF. Somatosympathetic reflexes: afferent fibers, central pathways, discharge characteristics. Physiol Rev 53: 916–947, 1973. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1973.53.4.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shimokawa A, Kunitake T, Takasaki M, Kannan H. Differential effects of anesthetics on sympathetic nerve activity and arterial baroreceptor reflex in chronically instrumented rats. J Auton Nerv Syst 72: 46–54, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1838(98)00084-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith SA, Williams MA, Leal AK, Mitchell JH, Garry MG. Exercise pressor reflex function is altered in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Physiol 577: 1009–1020, 2006. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.121558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Taylor RF, Schramm LP. Differential effects of spinal transection on sympathetic nerve activities in rats. Am J Physiol 253: R611–R618, 1987. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1987.253.4.R611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Teasell RW, Arnold JM, Krassioukov A, Delaney GA. Cardiovascular consequences of loss of supraspinal control of the sympathetic nervous system after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 81: 506–516, 2000. doi: 10.1053/mr.2000.3848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tian GF, Duffin J. Connections from upper cervical inspiratory neurons to phrenic and intercostal motoneurons studied with cross-correlation in the decerebrate rat. Exp Brain Res 110: 196–204, 1996. doi: 10.1007/BF00228551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weaver LC, Marsh DR, Gris D, Brown A, Dekaban GA. Autonomic dysreflexia after spinal cord injury: central mechanisms and strategies for prevention. Prog Brain Res 152: 245–263, 2006. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(05)52016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.West CR, Squair JW, McCracken L, Currie KD, Somvanshi R, Yuen V, Phillips AA, Kumar U, McNeill JH, Krassioukov AV. Cardiac consequences of autonomic dysreflexia in spinal cord injury. Hypertension 68: 1281–1289, 2016. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.07919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]