Abstract

A disproportional large number of neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs) is caused by variants in genes encoding transcription factors and chromatin modifiers. However, the functional interactions between the corresponding proteins are only partly known. Here, we show that KDM5C, encoding a H3K4 demethylase, is at the intersection of transcriptional axes under the control of three regulatory proteins ARX, ZNF711 and PHF8. Interestingly, mutations in all four genes (KDM5C, ARX, ZNF711 and PHF8) are associated with X-linked NDDs comprising intellectual disability as a core feature. in vitro analysis of the KDM5C promoter revealed that ARX and ZNF711 function as antagonist transcription factors that activate KDM5C expression and compete for the recruitment of PHF8. Functional analysis of mutations in these genes showed a correlation between phenotype severity and the reduction in KDM5C transcriptional activity. The KDM5C decrease was associated with a lack of repression of downstream target genes Scn2a, Syn1 and Bdnf in the embryonic brain of Arx-null mice. Aiming to correct the faulty expression of KDM5C, we studied the effect of the FDA-approved histone deacetylase inhibitor suberanilohydroxamic acid (SAHA). In Arx-KO murine ES-derived neurons, SAHA was able to rescue KDM5C depletion, recover H3K4me3 signalling and improve neuronal differentiation. Indeed, in ARX/alr-1-deficient Caenorhabditis elegans animals, SAHA was shown to counteract the defective KDM5C/rbr-2-H3K4me3 signalling, recover abnormal behavioural phenotype and ameliorate neuronal maturation. Overall, our studies indicate that KDM5C is a conserved and druggable effector molecule across a number of NDDs for whom the use of SAHA may be considered a potential therapeutic strategy.

Introduction

The fine-tuning of histone 3 lysine 4 (H3K4) methylation is of fundamental importance during prenatal development [1–3]. Any deregulation of this epigenetic signalling can cause a variety of neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs), such as microcephaly, epilepsy, intellectual disability (ID) and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) [1–3].

It is beginning to emerge that convergent pathogenetic pathways control H3K4 methylation [4, 5]. However, this knowledge is still only rudimentary and better insight will be needed, also for developing new strategies for therapeutic intervention.

Lysine-specific demethylase 5C (KDM5C/JARID1C/SMCX; MIM 314690) is a well-conserved NDD demethylase coding gene, whose protein acts as a 2-oxoglutarate–dependent dioxygenase [6]. KDM5C is an epigenetic eraser that removes methyl groups from tri- and dimethyl H3K4 (H3K4me3 and H3K4me2), thus inducing transcriptional repression in neuronal development and survival and dendritic growth [7,8]. Located at Xp11.22, KDM5C is mutated in children with X-linked syndromic ID (XLID) Claes-Jensen type (MIM 300534), characterized by moderate to severe ID, spasticity, epileptic seizures, short stature and microcephaly [9,10] or showing a developmental delay and an autism-like disorder [11,12]. Mutations in KDM5C can reduce protein stability and demethylation activity, thus inducing an increment in H3K4me3 level that is a hallmark of active transcription [13].

Recently, it has been demonstrated that KDM5C is involved in fine-tuning enhancer activity during neuronal maturation [14]. In mice, Kdm5C-KO animals show adaptive and cognitive abnormalities, impaired social behaviour, memory deficits, aggressive behaviour and seizure susceptibility [14]. Furthermore, somatic mutations in KDM5C have been found in patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) in association with genomic instability [15].

A picture of the basic machinery regulating KDM5C transcription, and the proteins involved, is beginning to emerge. KDM5C is a direct target of Zinc Finger protein 711 (ZNF711; MIM 314990) [16, 17] a transcription factor that acts through the recruitment of PHD Finger protein 8 (PHF8; MIM 300560) [16] to the KDM5C promoter. PHF8 is a H4K20me1 and H3K9me2 demethylase, which erases repressive histone marks and regulates proximal gene expression [18]. Mutations in ZNF711 have been found in few males with non-syndromic ID accompanied by autistic features or mild facial dysmorphisms (MIM 300803) [17, 19]. Mutations in PHF8 have been identified in a subset of patients with XLID, often accompanied with cleft lip/cleft palate (Siderius-Hamel syndrome; MIM 300263) [20, 21]. We previously found that KDM5C is transcriptionally regulated by the homeotic transcription factor Aristaless-related homeobox (ARX; MIM 300382), implicated in neuronal migration and corticogenesis [22], whose mutations have been found in a range of neurological phenotypes with ID as a consistent feature [22–25]. With variable penetrance, ARX loss-of-function mutations cause X-linked lissencephaly with ambiguous genitalia (XLAG; MIM 300215), agenesis of the corpus callosum (ACC), early-onset intractable seizures (EIEE1) and severe psychomotor retardation [22–25]. Despite identifying these three proteins having a role in regulating KDM5C transcription, the complexity of their interplay remains poorly understood. Elucidating the key features of the KDM5C regulatory axes in healthy and disease states is required to pave the way not only to dissect the molecular pathogenesis of NDD but also to identify compounds targeting the impact of KDM5C deregulation.

In this study, we tested whether the three NDD regulatory proteins, ZNF711, PHF8 and ARX, work together or individually to stimulate KDM5C transactivation. In this framework, we analysed the functional impact of mutations in each regulator gene. Thus, we postulate a correlation between the NDD severity and the KDM5C promoter activity providing new insights into the boundaries of shared co-morbidities. Aiming to study the downstream effect of KDM5C reduction in a NDD animal model, we analysed the transcript levels of known effector genes in the XLAG brain of mice ablated for ARX (Arx-null mice). We evaluated the activity of a histone deacetylase inhibitor to promote KDM5C rescue in murine ES cells and C. elegans, both defective in ARX-KDM5C axis. Histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi) are a class of small-molecule therapeutics used to correct transcriptional unbalance in several diseases [26, 27]. By increasing histone acetylation of condensed chromatin, they activate expression of epigenetically silenced genes. Among them, suberanilohydroxamic acid (SAHA, also named Vorinostat) is a Food-Drug Administration approved-HDACi used in T cell lymphoma therapy [28], known to be able to force neuronal gene expression [27, 29] and promote neuronal differentiation [30]. In this study, we demonstrate that the defective dosage in KDM5C impacting neuronal maturation and behavioral responses is therapeutically corrected by in vitro and in vivo SAHA treatments.

Results

The NDD proteins ARX and PHF8 synergistically transactivate KDM5C promoter activity

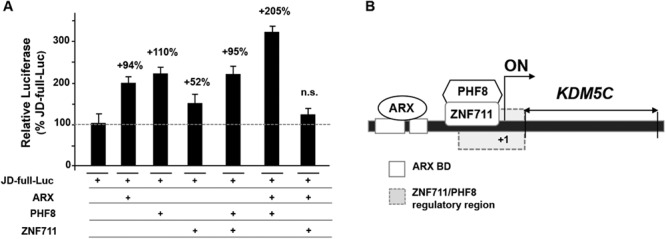

To determine the interplay among the three transcriptional regulators ARX, ZNF711 and PHF8 at the KDM5C promoter, we examined by in vitro assay their ability to work autonomously or in combination. We co-transfected a luciferase report construct carrying the KDM5C 5′ promoter region (−1001/+73, JD-full-Luc), already isolated by us [25], with the mammalian expression vectors of full-length ARX, ZNF711 and PHF8. The over-expression of ARX, PHF8 and ZNF711 individually showed an increase in expression of 94%, 110% or 52%, in comparison with the basal JD-full-Luc activity, respectively (Fig 1A). The combined over-expression of PHF8 and ZNF711 caused a stimulation of KDM5C reporter expression (+95%) comparable to PHF8 alone or ARX alone (Fig 1A). Surprisingly, ARX plus PHF8 caused a cumulative luciferase increase mediating a strong response (205%; Fig 1A). On the contrary, the co-expression of ARX with ZNF711 showed a non-significant response as compared with either ARX or ZNF711 alone, implying a possible negative regulatory interaction (Fig 1A). Altogether, these data suggest that PHF8 has stronger synergy with ARX to induce KDM5C transcription than with ZNF711 and that ARX and ZNF711 may function as antagonist transcription factors competing for PHF8.

Figure 1.

Analysis of the effect of ARX, PHF8 and ZNF711 on KDM5C transcription. Co-transfections of the WT CNE-5′JD construct (JD-full-Luc) with the WT ARX, PHF8 and ZNF711 expression plasmids. The luciferase activity of JD-full-Luc transactivated by each KDM5C regulator alone or in combination is reported as a percentage of the expression of the basal JD-full-Luc activity. Each luciferase assay was performed in duplicate in four independent experiments. The bars indicate the mean ± standard error of four independent experiments. n.s., not significant difference (one-way ANOVA test with Bonferroni correction). (B) Schematic cartoon of the KDM5C regulatory region showing the DNA territories required for the activity of ARX and for the ZNF711/PHF8 complex.

Moreover, to understand whether the cooperative activity of ARX with PHF8 induce a change in chromatin accessibility, we analysed H3K4me3 levels associated with KDM5C 780 bp upstream of the transcription start site. As expected, quantitative chromatin immunoprecipitation (qChIP) analysis shows a robust H3K4me3 enrichment when ARX and PHF8 are co-expressed (Text S1 and S1A and S1B Figs).

Since PHF8 and ARX act cooperatively, we next asked whether the PHF8-dependent stimulation requires a regulatory territory shared with ARX. By luciferase assay, we studied four deleted constructs covering the 5′ regulatory region of KDM5C (JD-full-Luc; S2 Fig) including two ARX binding sites, BD1 and BD2 [25]. Upon co-transfection with WT PHF8, only the JD_BD3 construct showed a transcriptional increase respect to the JD-full-Luc (S2 Fig). A similar response, even if with a milder effect, was observed in co-transfection with ZNF711. Therefore, we predict that the PHF8-dependent stimulation necessitates a proximal region, located between −407 and −355, which does not include ARX binding sites but instead is also essential for the ZNF711-dependent stimulation (Fig 1B and S2 Fig).

Mutations in ZNF711, PHF8 and ARX damage the KDM5C transactivation

To verify how disease mutations impact on KDM5C stimulation, we analysed 11 mutations found in patients with variable NDD phenotypes whose common clinical feature is ID and/or developmental delay (S1 Table and S3A Fig). There are two novel ZNF711 nonsense mutations, c.1543C > T (p.R515X) and c.2127_2128delTG (p.C709X), identified in two distinct families with severe XLID with epilepsy and XLID with dysmorphism, respectively (c.e.S., personal communication); two PHF8 missense alterations, c.836 T > C (p.F279S) and c.2720G > A (p.R907H), found in two patients with mild XLID with cleft lip/cleft palate [21, 31]; and seven ARX missense mutations, p.R332P, p.T333 N p.L343Q, p.P353R, p.R358S, p.R379S and p.R379L, identified in XLAG patients with variable comorbidity, including ACC, intractable epilepsy of neonatal onset and variable XLID [32].

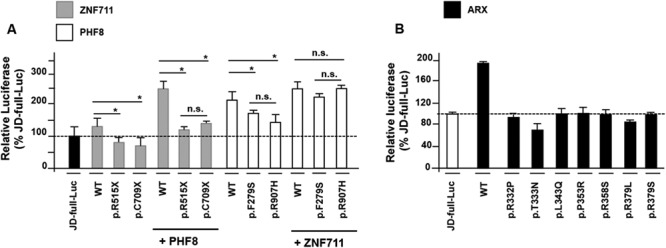

Transient transfection with JD-full-Luc and ZNF711 constructs showed that all mutant constructs lead to a complete loss of transactivation activity as compared with the WT construct (Fig 2A). Importantly, the loss of activity of mutant ZNF711 protein was not compensated by WT PHF8 co-transfection (Fig 2A). Mechanistically, both ZNF711 mutations could trigger the degradation of the related mRNA through as nonsense-mediated decay process. In overexpression studies, we observed that the ZNF711 p.R515X and p.C709X constructs produce shortened nuclear proteins (56 and 86 kDa in comparison to 96 kDa WT protein; S3B Fig) that could have lost the ability to activate the target promoter. However, in both scenarios, the two ZNF711 mutations produce loss of function (LoF) proteins. Both PHF8 mutant constructs (p.F279S and p.R907H) showed a decrease of transactivation activity (partial LoF). Strikingly, this reduction was rescued by ZNF711 WT co-expression (Fig 2A). These point mutations affect two highly conserved residues located in the JumonjiC domain (p.F279S) and in COOH terminus (p.R907H), respectively, that do not interfere with the nuclear localization (S3A and S3C Figs). In contrast to the ZNF711 LoF mutations, we predict that the PHF8 p.F279S and p.R907H are hypomorphic alleles with variable penetrance (partial LoF) that barely impair the KDM5C transactivation. By analysing the seven ARX missense mutant constructs p.R332P, p.T333 N p.L343Q, p.P353R, p.R358S, p.R379S and p.R379L in co-transfection with JD-full-Luc, we found that they are LoF alleles because of a luciferase activity similar with the basal one (Fig 2B). By qChIP experiments with Myc-tagged ARX constructs, we showed that the p.R332P, p.R379S and p.P353R mutations have lost the ability to bind the KDM5C BD1 and BD2 sites (S3D Fig). Based on these findings, we conclude that mutations in ZNF711, PHF8 and ARX alter the KDM5C transactivation with variable effects, depending on the functional severity of the mutation: from complete LoF, as in ARX and ZNF711 mutations, to partial LoF, as in PHF8 mutations (S1 Table). These findings highlight the role of KDM5C as a common target gene whose defective expression could cause one or more common clinical signs. These findings strongly support our idea depicting KDM5C as a promising biomarker for multiple NDDs with sharing comorbidity.

Figure 2.

Impact of ZNF711, PHF8 and ARX mutations on KDM5C cis-regulating element. Transactivation of the KDM5C 5′ UTR region by (A) wild-type and mutant ZNF711 and PHF8 proteins and (B) WT and mutant ARX proteins. The luciferase activity of each construct is reported as a percentage of the expression of the basal JD-full-Luc activity. Each luciferase assay was performed in duplicate in four independent experiments. The bars indicate the mean ± standard error of four independent experiments. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (one-way ANOVA test with Bonferroni correction, *P < 0.05). n.s., not significant difference.

A defective dosage of KDM5C causes a lack of repression of NDD-related transcripts in XLAG Arx-/Y brain

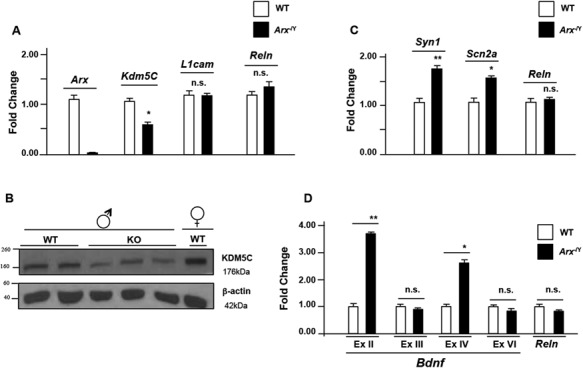

Having established by in vitro studies that ARX is a strong activator of KDM5C expression, we set out to investigate the endogenous expression of KDM5C and its downstream effectors in brain. For this, we tested Kdm5C dosage and its repressor activity in embryonic brain of Arx-null mice (Arx-/Y) that recapitulate the cortical malformations of ARX patients with XLAG [33]. By real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR), we analysed the Kdm5C mRNA level establishing that it is about 50% lower in the Arx-/Y than in the WT E18.5 whole brain (Fig 3A). No changes have been observed in L1 cell adhesion molecule (L1cam, GenBank: NM_008478.3) and Reelin (Reln, GenBank: BC118041.1) levels (Fig 3A). Consistent with this result, we found a robust decrease in the KDM5C protein level (Fig 3B). Remarkably, in forebrain dissected regions, where Arx and Kdm5C are simultaneously expressed (S4A Fig), Kdm5C is significantly lower in each Arx-/Y region tested compared with the WT one (S4B Fig). As a result of KDM5C depletion, we analysed target genes predicted as being transcribed more abundantly in the Arx-/Y mice than in the WT animals [7]. Specifically, we examined three Kdm5C-repressed genes, whose human counterparts are known to be involved in different brain disorders: i. Sodium channel neuronal type II alpha subunit (SCN2A; MIM 182390) [34,35]; ii. Synapsin I (SYN1; MIM 313440) [36]; and iii. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF; MIM 113505) [37–42]. In whole E18.5 Arx-/Y brains, we detected a robust increase in the expression of both Syn1 (GenBank: BC022954.1) and Scn2a (GenBank: KM373687.1) transcripts (Fig 3C). For Bdnf (GenBank: BC034862.1) we observed an increase in the levels of two transcript isoforms, Bdnf II and IV (Fig 3D), whose transcription is activated by two alternative KDM5C-dependent promoters [7,39–42]. As expected, we did not observe any change in the levels of the Bdnf isoforms, Bdnf III and VI, whose transcriptional regulation is KDM5C-independent (Fig 3D). Our data suggest that a decreased dosage of KDM5C slacks the repression in specific murine genes that in turn may compromise brain development and contribute to the disease manifestations. These findings strengthen our hypothesis that a decreased KDM5C dosage is an index of a faulty molecular process through which specific neuronal defect/s may occur.

Figure 3.

KDM5C downregulation correlates with Syn1, Scn2a and Bdnf upregulation in Arx-/Y mouse brain. (A) Analysis of Kdm5C/KDM5C expression by real time PCR analysis and (B) western blotting in the whole embryonic brain (E18.5). (C) Real-time PCR analysis of the Syn1, Scn2a transcripts and (D)Bdnf exon II, exon III, exon IV and exon VI isoforms in the whole embryonic brain (E18.5). Each transcript analysis was performed in triplicate and the samples were normalized with Gapdh and 18S. The bars indicate the mean ± standard error of repeated experiments. In (A-D), asterisks indicate statistical significance compared with WT control mice (one-way ANOVA test with Bonferroni correction): *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005. The western blotting experiment was repeated with five WT and Arx-/Y mice brain obtaining similar results. The beta-actin antibody (β-actin) was used as a loading control.

SAHA rescues KDM5C depletion in Arx-KO murine neurons and ameliorates defective neuronal maturation

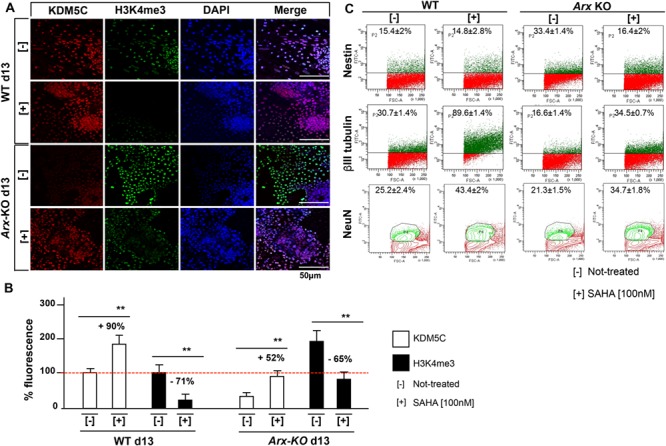

We investigated if treatment with SAHA, a HDACi known to upregulate neuronal gene expression [27, 29], could correct KDM5C downregulation. We chose as a model the Arx-KO neuronal cells with a severe KDM5C depletion coupled with a strong H3K4me3 increase [25]. First, we established that at the minimum effective dose of 100 nM, SAHA is able to correct Kdm5C expression in Arx-KO mature neurons at both mRNA and protein levels (Text S1 and S5A-E Figs). Upon SAHA exposure, we observed that SAHA has a direct activity on Kdm5C promoter modifying the acetylation level of Histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9ac), a histone mark associated with active transcription (Text S1 and S5A-E Figs). Next, by immunofluorescence studies, we proved that SAHA treatment induces a KDM5C upregulation, which directly correlates with a H3K4me3 decrease (Fig 4A and 4B). Overall, these findings suggest that Kdm5C is a SAHA-sensitive gene and its downregulation in Arx-deficient disease model could be restored by SAHA. Since Arx-KO/Kdm5C-depleted cells show a delay in in vitro neuronal maturation [25], we tested the SAHA activity, known to be a modulator of neuronal precursor cell differentiation [30]. Upon SAHA treatments, we assessed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis a robust decrease in the content of immature neurons. Indeed, nestin+ cells decreased from 33.4 + 1.4% in the untreated culture to 16.4 + 2% in the SAHA-treated ones (Fig 4C). In parallel, a robust expansion of mature neuronal populations has been observed: β-III tubulin+ cells increased from 16.6 + 1.4% to 34.5 + 0.7%, and NeuN+ cells increased from 21.3 + 1.5% to 34.7 + 1.8%. Consistently, real time PCR data for Nestin (Nestin, GenBank: BC062893), Paired box gene 6 (Pax6, GenBank: NM_013627.6) and Glutamate decarboxylase (Gad65, GeneBank: L16980.1) showed a decrease in the relative abundance of Nestin and Pax6 transcripts, both markers of immature neurons, and the increase in Gad65 transcript as marker of mature neurons (S6 Fig). Although it has been reported that KDM5C modulates the expression of plasticity-related genes during neuronal maturation [14], it is still unclear whether KDM5C depletion contributes directly to the defective maturation of Arx-KO ESs in neurons. However, the application of SAHA showed an additional and unexpected benefit in ameliorating neuronal differentiation when the ARX-dependent processes are severely compromised.

Figure 4.

SAHA impacts on KDM5C-H3K4me3 and neuronal differentiation of ES-Arx KO-derived cells. (A) Immunofluorescence analysis of KDM5C and its substrate H3K4me3 in ES-derived cells at the endpoint of in vitro neuronal differentiation (day 13). Treated and untreated cells were fixed and stained with antibodies specific for KDM5C and H3K4me3. The nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Images were taken randomly under a Nikon confocal microscopy. The KDM5C- and H3K4me3-stained nuclei and DAPI-stained nuclei were counted. Five fields from three replicates for each marker were analysed. (B) The activity of the marked proteins localized in the untreated cells compared with that present in the SAHA-treated cells, is reported as a percentage increase (+) or percentage decrease (−). The bars indicate the mean ± standard error of repeated experiments. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (one-way ANOVA test with Bonferroni correction, **P < 0.005). (C) Fractionation of WT and Arx-KO derived neurons by flow cytometry, comparing the percentage of Nestin+, β-III tubulin+ and NeuN+ cells, before and after SAHA treatment. The experiments were performed in triplicate and the mean ± standard error is reported. The cells were analysed using a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC-A) channel. The events are displayed as a FITC-A versus FSC-A density plot. FSC, forward scatter.

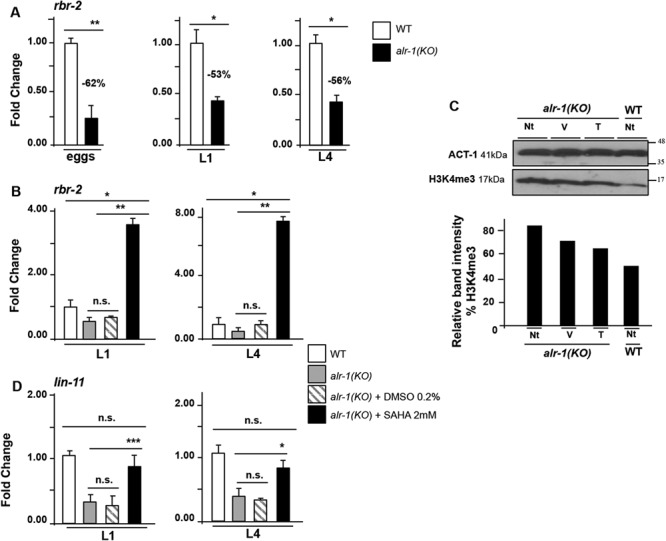

SAHA corrects RBR-2 depletion in C. elegans ARX/alr-1 larvae

In order to validate the SAHA efficacy to rescue KDM5C depletion during the early stage of development in an in vivo animal model, we studied the C. elegans mutant ablated for alr-1 (GenBank: NM_077459.4), the ortholog of ARX. First, we tested whether ALR-1 controls the transcription of H3K4 demethylase rbr-2 (GenBank: NM_069631.6), the single ortholog of human KDM5 family in C. elegans [43]. By consulting the modENCODE data set where genomic binding sites for a number of C. elegans transcription factors have been annotated [44], we mapped a strong ChIP-seq signal for ALR-1 in a region upstream to exon 1 of rbr-2 (S7A Fig). In line with this data, by real time PCR studies we found a rbr-2 mRNA decrease in alr-1(KO) eggs (−62%), and in animals at the first (L1; −53%) and at the fourth (L4; −56%) larval stages, compared with the WT controls (Fig 5A and S7B Fig). These evidences support the idea that rbr-2 is positively regulated by ALR-1 in early embryogenesis and during larval development. Consequently, we conclude that the ARX-KDM5C is a conserved regulatory axis. We thus used alr-1(KO) mutants to verify SAHA efficacy to rescue rbr-2 depletion. By exposing alr-1(KO) animals to the highest non-toxic concentration (2 mM = the minimum effective dose, MED), we observed a strong rbr-2 upregulation at L1 and L4 stages (Fig 5B). Next, we verified if the rectification of rbr-2 expression impacts on H3K4me3 level. In fact, alr-1(KO) animals, as well as rbr-2(KO), showed an H3K4me3 increase because of the faulty H3K4 demethylase activity (S7C Fig). Upon SAHA exposure of alr-1(KO) animals, western blotting analysis revealed a H3K4me3 band which intensity is similar to that found in WT animals (Fig 5C). Additionally, we also found a rescue effect on LIM homeobox gene lin-11 expression level (GenBank: FJ805074.1) at L1 and L4 stages (Fig 5D). lin-11 is a direct positive target of RBR-2 involved in neuronal fate [45, 46] and dendritic morphogenesis [47], whose defective expression has been detected in alr-1(KO)/rbr-2 depleted eggs and L1 and L4 larvae (S7D Fig). Based on these results, we propose that ALR-1/RBR-2 is a conserved regulatory pathway with SAHA being able to correct rbr-2 depletion at early larval stages.

Figure 5.

SAHA rectificates molecular defects in vivo. (A)rbr-2 expression in eggs, L1 and L4 larval stages, in WT and alr-1(KO) animals. (B) Effects of SAHA treatment on the expression of rbr-2. (C) Effects of SAHA treatment on the global level of H3K4me3. Western blot (upper panel) and band quantification (bottom panel) analysis of H3K4me3 in non-treated (Nt), DMSO (V) and SAHA (T) treated alr-1(KO) mutants and in non-treated (Nt) WT animals. ACT-1 was used as a loading control. The band quantification of H3K4me3 was analysed with ImageQuant 5.0 software. (D) Effects of SAHA treatment on the expression of RBR-2 target gene lin-11 in L1 and L4 larval stages. The bars indicate the mean ± standard error of three independent experiments and act-1 was used as an internal control. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.0001). n.s. indicates a not significant difference.

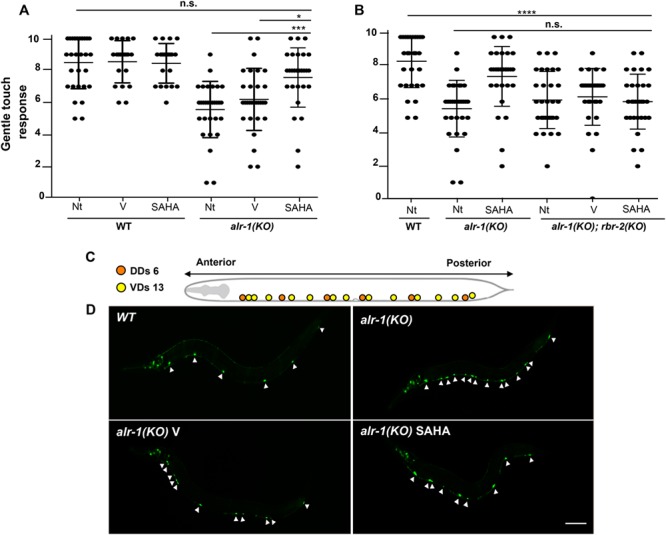

SAHA improves neuronal functions in alr-1(KO) through rbr-2

We next asked whether SAHA is able to recover neuronal deficiencies affecting alr-1(KO) animals. As already described, alr-1(KO) mutants show a loss of sensitivity to gentle touch caused by a defect in the touch receptor neurons [48]. They also showed a defective differentiation of the ventral D-type GABAergic motor neurons (VDs), which adopt the fate of dorsal D-type GABAergic motor neurons (DDs) [49].

We exposed alr-1(KO) L4 larvae to SAHA (2 mM). Thus, we observed that gentle touch sensitivity is significantly improved in adult treated-animals -compared to vehicle-treated (0.2% DMSO) and untreated controls- and produce a response similar to that shown by WT animals (Fig 6A and S1, S2, S3 Movies). Next, to prove whether this effect is mediated by the ALR-1/RBR-2 axis, we generated the double mutants alr-1(KO);rbr-2(KO). Remarkably, in these animals no touch sensitivity recovery has been observed upon SAHA treatments suggesting that the restoration of this behavioural response acts through RBR-2 (Fig 6B). Furthermore, given our findings showing that SAHA ameliorates neuronal differentiation in Arx-KO ESs, we tested whether SAHA is also able to have a positive impact on the defective VD development shown by alr-1(KO). Normally, WT adult animals present nineteen ventral cord neurons (thirteen named VDs and six DDs), whose neuronal processes constitute ventral and dorsal nerve bundles (Fig 6C) [50]. alr-1(KO) adult animals showed an abnormal number of DD motor neurons expressing the flp-13p::gfp transgene [49]. In SAHA-treated alr-1(KO) L4 larvae and young adult animals, we observed a partial rescue in the number of DD motor neurons that is significantly lower (Fig 6D and S2 Table), in comparison to the DDs counted in vehicle-treated mutants. As already stated for the defective maturation of Arx-KO/Kdm5C-depleted neurons, a mechanistic explanation linking RBR-2 to the VD maturation is unknown. However, also in alr-1(KO) mutants, whose are defective in rbr-2 expression, SAHA treatments exert an extra activity improving neuronal maturation when the ALR-1-dependent program is sternly damaged.

Figure 6.

SAHA impacts on alr-1 mutant function and neuron differentiation through rbr-2.(A, B) SAHA was able to rescue gentle touch sensitivity in alr-1(KO) adult animals but not in alr-1(KO);rbr-2(KO) double mutants. Each dot corresponds to an individual animal stimulated 10 times (N = 30 for mutants and WT animals tested). The mean and the 95% confident interval are shown. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (one-way ANOVA test with Bonferroni correction; *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.0005, ****P < 0.0001) compared with untreated (Nt) or DMSO-treated animals (V). n.s. indicates a not significant difference. (C) Diagram of the 19 GABAergic motor neuron cell bodies ventrally located in WT animals, subdivided in six DDs (in orange) and 13 VDs (in yellow). (D) Partial rescue of defective development of GABAergic motor neurons in alr-1(KO) mutants after SAHA treatment. Confocal images of an adult WT animal and alr-1(KO) mutants expressing a transgene that allows the visualization of the DD motor neurons, indicated by arrowheads. Scale bar is 100 μm. The anterior of the animal is to the left, ventral is down in (C) and (D).

Discussion

Our work has revealed that the XLID gene KDM5C is a central hub of a multi-component pathogenic cascade implicated in a group of NDDs and that its reduced dosage can be therapeutically corrected by SAHA treatments, both in vitro and in vivo settings. We described the functional relationship among the KDM5C regulators ARX, ZNF711 and PHF8, whose genes are known to be involved in NDD phenotypes with shared comorbidity. We found that ARX and ZNF711 function as antagonist transcription factors (TFs) and may compete for the recruitment of PHF8, which is able to boost the transcriptional activity at KDM5C promoter, through H3K4me3 enrichment. Our data indicate that ARX acts cooperatively with PHF8 by using distinct regulatory territories of KDM5C promoter, suggesting that their recruitment may be mediated by independent mechanisms, through interaction with DNA or other DNA-bound proteins. Additional studies are needed to demonstrate whether the cooperativity between ARX and PHF8 requires a direct contact or is mediated by changes in the physical properties of DNA. It is striking to note that when we co-expressed the two TFs ARX and ZNF711, we observed a non-significant KDM5C stimulation as compared to either TF alone. We suggest that these two TFs may functionally antagonize each other in response to specific stimuli. In alternative, ARX may act as transcriptional repressor of KDM5C. Indeed, ARX is known to act as both an activator and repressor of gene expression [22–23,25]. Whereas an accurate characterization of the bifunctional transcriptional activity of ARX is required, this consideration point towards a role of ARX as on-off switch for KDM5C transcription.

Previous studies revealed a dynamic co-expression of ARX with KDM5C from the neuronal commitment to the final maturation [25], while ZNF711 and PHF8 are co-expressed with KDM5C along all stages of neuronal differentiations [51]. Noteworthy, KDM5C and its three regulatory genes are located in syntenic mammalian blocks of X chromosome (UCSC GRCh38 NCBI homology map). Although specific studies are required to define the topological cis-landscape of these X chromosome territories, their expression could be coordinated in spatiotemporal transcriptional waves.

By studying how mutations in the three KDM5C regulatory genes impact on KDM5C transactivation, we found that they caused a variable reduction in KDM5C promoter activity, irrespective of the underlying primary genetic defects. Complete LoF alleles due to several ARX missense mutations and ZNF711 truncating variants present an extensive phenotypic variability. In contrast, PHF8 missense mutations appear to represent partial LoF alleles.

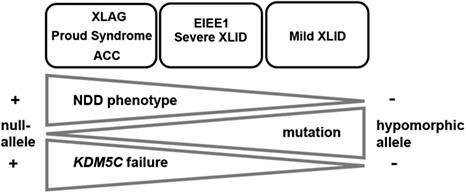

Thus, we propose a molecular-phenotypical model showing the direct relationship between the type of mutation and the severity of the NDD disease, which correlates with the reduced KDM5C expression (Fig 7). Although there are significant differences among clinical manifestations caused by mutations in ARX [23–25], ZNF711 [17,19], PHF8 [20–21] (Table S1) and KDM5C [9–11] there also is a considerable overlap in neuronal illnesses, particularly referred to ID. This is commonly present, even if at various degree, in all patients mutated in ARX, KDM5C, ZNF711 and PHF8, alone or in combination with other specific manifestations, such as cortical malformations or refractory epilepsy [9, 23–25], short stature [10], autism [11,12], facial dysmorphism [17,19], and cleft lip/cleft palate [20–21]. These observations suggest a phenotypical intersection among the ARX-, ZNF711-, PHF8- and KDM5C-related disorders and allow to propose ID as a common clinical manifestation, potentially linked to a defective KDM5C activity into control neuron arborization and brain network [9,14]. However, recent literature shows that in patients mutated in KDM5C [53], or other chromatin regulator genes involved in NDDs [54–57], the epigenetic code, including the DNA methylation, is generally disrupted, suggesting a correlation between overlapping epi-signature profiles and distinct endo-phenotypes. Thus, given the role of ARX and ZNF711 as transcriptional regulators and KDM5C and PHF8 as chromatin modifiers, the identification of peculiar epi-signature patterns, caused by single mutation in each of them, could help to define a genotype-phenotype bridge between common epi-signature hallmarks and shared comorbidity.

Figure 7.

Implications for neurodevelopmental disorders linked to KDM5C decrease. Graphic representation of the correlation between the severity of the neurodevelopmental phenotypes (NDDs) from the most severe cortical malformations (XLAG, Proud syndrome and ACC, on the left) to the least severe (mild XLID, on the right) caused by mutations in KDM5C regulators, and the functional activity of the NDD mutations (from null-alleles to varying hypomorphic alleles) corresponding to KDM5C defects, from the most severe (+) to the least severe (−). Our model proposes the direct relationship between the type of mutation (null-allele, LoF or hypomorphic allele, partial LoF), and the severity of the NDD disease (from the most severe to the least severe), which correlates with the reduced KDM5C expression (from the most severe reduction to the least severe one).

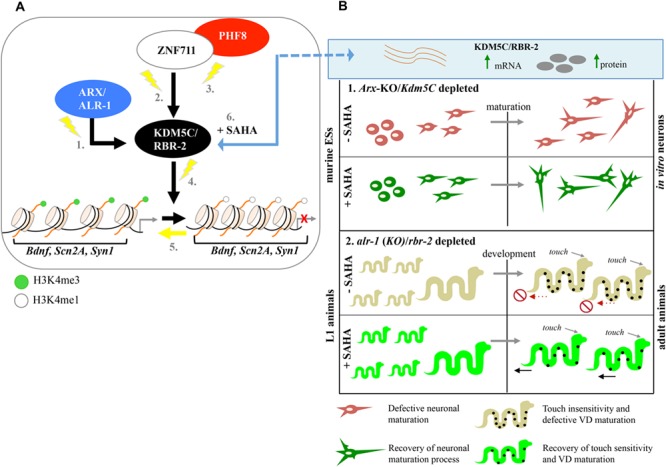

Disruption of KDM5C dosage affects H3K4 methylation and consequently gene expression. In line with the notion that KDM5C represses REST-mediated neuronal gene expression [7], we showed that a decreased KDM5C dosage causes a lack of transcriptional repression of Scn2a, Syn1 and Bdnf in prenatal Arx-/Y brains. The human counterparts for each are known genes mutated in a number of NDD-related syndromes. SCN2A, a neuronal voltage-gated sodium channel NaV1.2, is mutated in several NDDs including EIEE, ID and ASD [34,35]. SYN1 has a critical role into controlling synaptic vesicle trafficking and neurotransmitter release and is mutated in male patients with epilepsy, learning disorders and ASD [36]. A deregulated expression of BDNF, which encodes a neurotrophin with a potent effect on excitatory and inhibitory synapses, has been found in distinct brain disorders, such as Rett syndrome, Kleefstra syndrome and Alzheimer's disease [37–42]. Therefore, we propose a module of tightly interconnected NDD genes designating KDM5C as a central hub through which we may study deregulated cross-talks and/or disease-associated sub-networks, such as neuronal homeostasis and synaptic activity (Fig 8A). In this scenario, consistent with the role of KDM5C as a dose-dependent inspector of synaptic plasticity involved in XLID, epilepsy and ASD [7–14, 52,53,58], a faulty KDM5C dosage could make the developing brain more prone to be damaged. Since KDM5C could intersect other epigenetic cascades linked to other neuronal diseases its outreach could be much wider than expected [2, 5, 53, 58–60].

Figure 8.

KDM5C is a SAHA-sensitive marker of a druggable pathway damaged in NDDs. (A) Model of the KDM5C-related pathway damaged in NDDs. Mutations in genes encoding the transcription regulators ARX (1.), ZNF711 (2.) and PHF8 (3.) damage the KDM5C transcription, which protein in turn, through a defective H3K4me3 demethylation process (4.), causes a lack of repression of Bdnf, Scn2a, and Syn1 (5.). Treatment with SAHA restores KDM5C activity and consequently the downstream signalling (6.). (B) In Arx-KO/Kdm5C-depleted cells, SAHA ameliorates neuronal maturation during in vitro differentiation (1.). In alr-1(KO)/rbr-2-depleted animals, the SAHA exposure during early stage of development rescues touch sensitivity deficit and ameliorates VDs maturation (2.).

We demonstrate here that KDM5C is a conserved transcriptional hub. Indeed, a robust decrease in Kdm5C/rbr-2 was found both in murine Arx-KO GABAergic neurons and C. elegans alr-1(KO) mutants, indicating that the regulatory ARX-KDM5C axis is a phenolog-disease process. Previous studies have been shown that KDM5C and PHF8 ortholog in C. elegans regulate axon guidance by acting in a common pathway [16,43,61]. Thus, these observations indicate that there is a complete conservation from nematode to humans of the ARX-KDM5C and PHF8-KDM5C axes in terms of regulation and function, which strongly support our model (Fig. 8A). Besides, although no ZNF711 homolog in C. elegans has been characterized, further studies are required to evaluate the potential conservation of the ZNF711-KDM5C axis.

The feasibility of using treatable C. elegans models represents a unique and powerful tool to design molecular-guided therapies for disorders where treatment options are absent or not appropriate [62,63]. In alignment with the rationale that SAHA is capable to force gene transcription [27,29,64–66], we have shown that this epimolecule corrects Kdm5C/rbr-2 deficiency both in Arx-KO ESs and C. elegans alr-1(KO) mutants (Fig 8B). Interestingly, acting specifically through rbr-2, SAHA exposure of alr-1(KO) animals rescues touch insensitivity, a behavioural defect affecting mechanosensory neurons [48]. Although the mechanism is unknown, we have also observed that SAHA ameliorates the aberrant neuronal maturation in Arx-KO ESs [25] and the defective VD differentiation in alr-1(KO) worms [49]. Therefore, the recent use of SAHA as a potent anticonvulsant drug that reduces seizure in Kcna1-null disease models [67] strongly supports its applicability in neurodevelopmental disease models. Further studies are required to establish the benefits of SAHA in treating disease mouse models defective in KDM5C, as well as in balancing installation of inappropriate repressive histone marks.

In conclusion, we have uncovered the molecular intersection within a group of X-linked NDDs genes emphasizing their converging role into controlling the transcription of KDM5C. These findings shed light on the pivotal role of KDM5C as a disease biomarker of a class of NDDs with associated co-morbidities that were traditionally considered to be distinct nosological entities but instead might share a common malfunctioning molecular gene network. Finally, we established that KDM5C is a conserved SAHA-sensitive gene and proved, as a proof of principle, that its defective expression is rescued by SAHA, an epi-molecule that could be employed in drug discovery against multiple NDDs or some of their co-morbidities.

Materials and methods

Cell lines, transient transfection and Luciferase assay

SH-SY5Y and HEK293T cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies), 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 mg/ml streptomycin (Life Technologies). The mES cells derived from wild-type (WT) and Arx knock-out mice (Arx−/Y) [33] were maintained in an undifferentiated state by culture on a monolayer of mitomycin C-inactivated fibroblasts in the presence of Leukaemia-Inhibiting Factor (Millipore), as described elsewhere [68]. Cells were plated in a six-well plate at a seeding density of 8 × 105 cells/well and transfected using Lipofectamine® 2000 (Life Technologies) following the manufacturer's instructions. Overexpressed protein levels were tested by immunoblot analysis. For the luciferase assay, the reporter activities were measured using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). Activities of firefly and Renilla luciferases were measured using the Dual-Glo® Luciferase Assay System (Promega). Firefly luciferase values were normalized using the Renilla values. Each assay was performed in duplicate in three independent experiments. All cell lines were tested regularly for mycoplasma contamination.

Plasmids

The mutants c.836 T > C (p.F279S) and c.2720G > A (p.R907H) in PHF8 were prepared using the QuikChange II XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer's instructions and verified by sequencing. The mutants c.1543C > T (p.R515X) and c.2127_2128delTG (p.C709X) in ZNF711 were created by cloning the mutated cDNA in the pcDNA3.1 GFP plasmid and verified by DNA sequencing. The other constructs expressing WT cDNA of ARX or mutations, the CNE-5′JD deleted regions and WT cDNA of PHF8 and ZNF711 have been described previously [16, 25, 32].

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

The ChIP assays on chromatin from the SH-SY5Y cells and ESCs were performed using MAGnify chromatin immunoprecipitation kit (Life Technologies) following the manufacturer's instructions. The antibodies used were specific for c-Myc (10 μg for 25 μg of chromatin, Sigma), H3K4me3 (2 μg for 25 μg of chromatin, Abcam) and H3K9ac (2 μg for 25 μg of chromatin, Abcam). The amplicons were measured by the SYBR Green fluorescence (Applied Biosystems) method. The human and murine fragments of KDM5C/Kdm5C were amplified with ChIP primers reported in S3 Table. An amplification of the highly conserved SHOX2/Shox2 binding site was used as a ChIP positive control [25]. All reactions were performed in triplicate in two independent experiments. The amount of the product was determined relative to a standard curve of input chromatin. The error bars express the mean ± SEM.

RNA extraction and Real-time polymerase chain reaction

For the RNA extraction, murine brain tissues and C. elegans eggs and animals were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and total RNA was extracted according to the TRIzol protocol (Life Technologies). Reverse transcription was performed with QuantiTect Reverse Transcription kit (Qiagen) and the steady-state mRNA abundance was determined using the Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) on the 7900HT Fast Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems), as a standard procedure. The oligonucleotide sequences for the transcript analysis in mice and C. elegans are reported in S4 and S5 Tables, respectively. For the Bdnf analysis, alternative transcripts were analysed by using oligonucleotides donated by Prof. E. Tongiorgi (University of Trieste, Italy) [39]. In mouse, the measures of transcript analysis were normalized to Gapdh and 18S RNA levels; in C. elegans, the measures were normalized to act-1 RNA level. Each experiment assay was performed in triplicate in three independent experiments.

Immunoblotting

The protein extracts from mammalian cells and tissues were prepared and separated following standard methods. Protein extraction in C. elegans was performed following the method described elsewhere [69]. After blocking with 5% non-fat milk, the membranes were incubated with specific antibodies. The following antibodies were used: anti-KDM5C (1:1000; SantaCruz), anti-H3K4me3 (1:5000; Abcam), anti-H3K9ac (1:1000; Abcam), and anti-GFP (1:1000; Novus biological). Anti-GAPDH (1:500; SantaCruz) and anti-β-actin (1:3000; SantaCruz) were used as loading controls. The signals were detected with an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Amersham Biosciences) and the films were processed for densitometric scanning.

Immunofluorescence

For the immunofluorescence analysis the commercial antibodies used were: c-Myc (1:1000; 9E10 SantaCruz), KDM5C (1:100; LS-BIO), H3K4me3 (1:400; Abcam). Rabbit AlexaFluor-488 (1:200; Life Technologies) and Texas Red (1:200; Life Technologies) were used as secondary antibodies. The images were superimposed with nuclear DAPI (1:5000; Roche) staining and taken randomly under a NIKON confocal microscope. The cells labeled by antibody staining and total cell number (based on DAPI nuclei staining) were quantified to obtain percentages of the target cell types. Error bars represent the mean ± SEM.

Flow cytometry

For the flow cytometry experiments, mES-derived cells were released into single-cell suspension by incubation in Accutase (0.05%, Biowest) at 37°C for 3 minutes. For the marker staining, 2.5 × 106 to 3 × 106 cells were re-suspended in 500 μL blocking buffer (10% goat serum, 0.3 M glycine diluted in staining buffer). The following antibodies (β-III tubulin, 1:200, Sigma; Nestin 1:20, Hybridoma bank; NeuN-conjugated mouse 488, 1:500, Millipore) were added to the cells. The stained cells were incubated with specific secondary antibodies: mouse AlexaFluor-647 (1:400; Life Technologies) and rabbit AlexaFluor-488 (1:400; Life Technologies). The cells were analyzed on BD FACS Canto using the BD FACS Diva Software with at least 10.000 events acquired.

Animal models

Arx −/y mice were maintained on a C57Bl/6 background and genotyping and sex assessment was performed as described elsewhere [33]. All protocols for animals have being approved by the Italian Minister of Health (DLgs116/92), in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care guidelines of the Institute of Genetics and Biophysics “Adriano Buzzati-Traverso,” under the accreditation number n307/2018-PR E58D.8.

C. elegans were grown and handled following standard procedures, under uncrowded conditions, at 20°C, on nematode growth medium (NGM) agar plates seeded with Escherichia coli strain OP50 [70]. For C. elegans strains (listed in Text S1) genotypes were determined by PCR assay using specific oligonucleotides (S5 Table).

SAHA treatments

Suberanilohydroxamic acid (SAHA, Selleckchem) was dissolved in DMSO to a stock concentration of 1 M and then diluted to the required concentrations with a complete culture medium of mammalian cells. The final concentration of DMSO was no greater than 0.01% in cell cultures. In C. elegans studies, SAHA dissolved in DMSO was added to plates poured with NGM agar to the desired concentration. Control NGM plates with the appropriate dilution of DMSO were used. Plates were allowed to dry for 12 hours before seeding with OP50 bacteria, after which they were incubated at 37°C overnight.

Gentle touch assay and microscope analysis

Well-fed, young adult C. elegans animals were used for gentle touch sensitivity assay to test mechanosensory neurons function. The assay was performed blind on NGM plates, 6 cm in diameter, seeded with bacteria, as described [71]. The response to gentle touch was quantified using an eyelash and counting the number of responses to ten touches delivered alternatively beyond the head and on the tail of thirty animals. A defective movement was scored when animals displayed no response to the stimulus and continued their normal movement. For each data set the mean number of positive responses per each animal is reported. Video recording was performed to monitor the movement pattern on Leica IC80 HD. Animals expressing the GFP-reporter in DD motor neurons were immobilized in 0.01% tetramisole hydrochloride (Sigma) on 4% agar pads and visualized using Zeiss Axioskop or Leica DMI6000B microscopes. All microscopes were equipped with epifluorescence and DIC Nomarski optics and images were collected with an Axiocam digital camera or with Leica digital cameras DFC 480 and 420 RGB. Pictures were taken with a Leica TCS SP2 AOBS laser scanning confocal microscope. Scale bar represents 100 μM.

Bioinformatics

Multiple protein sequences and amino acid conservation was performed by CLUSTALW and Jalview softwares.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were performed with the GraphPad Prism 4 software (GraphPad Software) to calculate the significance of the differences among each sample against the control. One-way ANOVA test with Bonferroni correction and Student t test were used for the statistical analysis. The standard error of the mean was used to estimate variation within a single assay. P-values of < 0.05 were considered significant.

Web Resources

BLAST, https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi

CLUSTALW, https://www.genome.jp/tools-bin/clustalw

GenBank, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/

Jalview, http://www.jalview.org/

modENCODE, http://www.modencode.org/

NCBI, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

OMIM, https://www.omim.org/

UCSC, https://genome.ucsc.edu/

Wormbase, https://wormbase.org/

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr G. Zampi for technical assistance and Dr F. Polino for the cartoon draws. We thank IGB Microscope Integrated Facility and IBBR Microscope Facility, IGB Mouse Facility, IGB FACS Facility and Wormbase. For the C. elegans strains we would like to thank A.E. Salcini (University of Copenhagen, Denmark, Copenaghen), P. Sengupta (Brandeis University, Waltham, Massachusetts), and the CGC, which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440). For Bdnf oligos, we would like to thank E. Tongiorgi (University of Trieste, Italy). We are grateful to P. Bazzicalupo (Naples), A.E. Salcini (University of Copenhagen, Denmark, Copenaghen), and S. Martinelli (Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Rome, Italy) for critical reading of this manuscript. We also are grateful to S. Dantone, ‘Associazione Uniti per crescere’ Onlus and ‘Families SCN2A Foundation’ for promoting SCN2A studies, ‘SPECIALmente Noi Onlus Foundation’ and ‘La forza del silenzio Onlus Foundation’ for promoting research in ASD. We are indebted to the worms and mice for their invaluable contribution. The study is dedicated to the memory of Ethan Francis Schwartz, 1996-1998.

This work was supported by Jerome Lejeune Foundation grants (1021-MM2012 and 1372-MM2015A), Telethon Foundation grant (GGP14198) and Italian Ministry of Economic Development grant (F/050011/02/X32) to M.G.M., by NIH/NICHD grant (HD-26202) to C.E.S., and by an Italian Ministry of Health ‘Ricerca corrente’ grant to S.F.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- 1. Vallianatos C.N. and Iwase S. (2015) Disrupted intricacy of histone H3K4 methylation in neurodevelopmental disorders. Epigenomics, 7, 503–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. van Bokhoven H. (2011) Genetic and epigenetic networks in intellectual disabilities. Annu. Rev. Genet., 45, 81–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gabriele M., Lopez Tobon A., D'Agostino G. and Testa G. (2018) The chromatin basis of neurodevelopmental disorders: rethinking dysfunction along the molecular and temporal axes. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry, 84, 306–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kleefstra T., Kramer J.M., Neveling K., Willemsen M.H., Koemans T.S., Vissers L.E., Wissink-Lindhout W., Fenckova M., van den W.M., Kasri N.N. et al. (2012) Disruption of an EHMT1-associated chromatin-modification module causes intellectual disability. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 91, 73–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen E.S., Gigek C.O., Rosenfeld J.A., Diallo A.B., Maussion G., Chen G.G., Vaillancourt K., Lopez J.P., Crapper L., Poujol R. et al. (2014) Molecular convergence of neurodevelopmental disorders. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 95, 490–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hancock R.L., Dunne K., Walport L.J., Flashman E. and Kawamura A. (2015) Epigenetic regulation by histone demethylases in hypoxia. Epigenomics, 7, 791–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tahiliani M., Mei P., Fang R., Leonor T., Rutenberg M., Shimizu F., Li J., Rao A. and Shi Y. (2007) The histone H3K4 demethylase SMCX links REST target genes to X-linked mental retardation. Nature, 31, 601–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Iwase S., Lan F., Bayliss P., de la Torre-Ubieta L., Huarte M., Qi H.H., Whetstine J.R., Bonni A., Roberts T.M. and Shi Y. (2007) The X-linked mental retardation gene SMCX/JARID1C defines a family of histone H3 lysine 3 demethylases. Cell, 128, 1077–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jensen L.R., Amende M., Gurok U., Moser B., Gimmel V., Tzschach A., Janecke A.R., Tariverdian G., Chelly J., Fryns J.P. et al. (2005) Mutations in the JARID1C gene, which is involved in transcriptional regulation and chromatin remodelling, cause X-linked mental retardation. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 76, 227–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Abidi F.E., Holloway L., Moore C.A., Weaver D.D., Simensen R.J., Stevenson R.E., Rogers R.C. and Schwartz C.E. (2008) Mutations in JARID1C are associated with X-linked mental retardation, short stature and hyperreflexia. J. Med. Genet., 45, 787–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Adegbola A., Gao H., Sommer S. and Browning M. (2008) A novel mutation in JARID1C/SMCX in a patient with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Am. J. Med. Genet., 146, 505–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vallianatos C.N., Farrehi C., Friez M.J., Burmeister M., Keegan C.E. and Iwase S. (2018) Altered gene-regulatory function of KDM5C by a novel mutation associated with autism and intellectual disability. Front. Mol. Neurosci., 11, 104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brookes E., Laurent B., Õunap K., Carroll R., Moeschler J.B., Field M., Schwartz C.E., Gecz J. and Shi Y. (2015) Mutations in the intellectual disability gene KDM5C reduce protein stability and demethylase activity. Hum. Mol. Genet., 15, 2861–2872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Scandaglia M., Lopez-Atalaya J.P., Medrano-Fernandez A., Lopez-Cascales M.T., Del B., Lipinski M., Benito E., Olivares R., Iwase S. and Shi Y. (2017) Loss of Kdm5c causes spurius transcription and prevents the fine-tuning of activity-regulated enhancers in neurons. Cell. Rep., 21, 47–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rondinelli B., Rosano D., Antonini E., Frenquelli M., Montanini L., Huang D., Segalla S., Yoshihara K., Amin S.B., Lazarevic D. et al. (2015) Histone demethylase JARID1C inactivation triggers genomic instability in sporadic renal cancer. J. Clin. Invest, 125, 4625–4637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kleine-Kohlbrecher D., Christensen J., Vandamme J., Abarrategui I., Bak M., Tommerup N., Shi X., Gozani O., Rappsilber J., Salcini A.E. et al. (2010) A functional link between the histone demethylase PHF8 and the transcription factor ZNF711 in X-linked mental retardation. Mol. Cell., 23, 165–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tarpey P.S., Smith R., Pleasance E., Whibley A., Edkins S., Hardy C., O'Meara S., Latimer C., Dicks E., Menzies A. et al. (2009) A systematic, large-scale resequencing screen of X-chromosome coding exons in mental retardation. Nat. Genet., 41, 535–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang J., Lin X., Wang S., Wang C., Wang Q., Duan X., Lu P., Wang Q., Wang C., Liu X.S. et al. (2014) PHF8 and REST/NRSF co-occupy gene promoters to regulate proximal gene expression. Sci. Rep., 23, 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. van der Werf I.M., Van Dijck A., Reyniers E., Helsmoortel C., Kumar A.A., Kalscheuer V.M., de Brouwer A.P., Kleefstra T., van Bokhoven H., Mortier G. et al. (2017) Mutations in two large pedigrees highlight the role of ZNF711 in X-linked intellectual disability. Gene, 20, 92–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Laumonnier F., Holbert S., Ronce N., Faravelli F., Lenzner S., Schwartz C.E., Lespinasse J., Van Esch H., Lacombe D., Goizet C. et al. (2005) Mutations in PHF8 are associated with X linked mental retardation and cleft lip/cleft palate. J. Med. Genet., 42, 780–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Abidi F.E., Miano M.G., Murray J. and Schwartz C.E. (2007) A novel mutation in the PHF8 gene is associated with X-linked mental retardation with cleft lip/cleft palate. Clin. Genet., 72, 19–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Friocourt G., Kanatani S., Tabata H., Yozu M., Takahashi T., Antypa M., Raguénès O., Chelly J., Férec C., Nakajima K. et al. (2008) Cell-autonomous roles of ARX in cell proliferation and neuronal migration during corticogenesis. J. Neurosci., 28, 5794–5805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shoubridge C., Fullston T. and Gécz J. (2010) ARX spectrum disorders: making inroads into the molecular pathology. Hum. Mutat., 31, 889–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Laperuta C., Spizzichino L., D'Adamo P., Monfregola J., Maiorino A., D'Eustacchio A., Ventruto V., Neri G., D’Urso M., Chiurazzi P. et al. (2007) MRX87 family with Aristaless X dup24bp mutation and implication for polyalanine expansions. BMC Med. Genet., 8, 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Poeta L., Fusco F., Drongitis D., Shoubridge C., Manganelli G., Filosa S., Paciolla M., Courtney M., Collombat P., Lioi M.B. et al. (2013) A regulatory path associated with X-linked intellectual disability and epilepsy links KDM5C to the polyalanine expansions in ARX. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 92, 114–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ganai S.A., Ramadoss M. and Mahadevan V. (2016) Histone Deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors-emerging roles in neuronal memory, learning, synaptic plasticity and neural regeneration. Curr. Neuropharmacol., 1, 55–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cenik B., Sephton C.F., Dewey C.M., Xian X., Wei S., Yu K., Niu W., Coppola G., Coughlin S.E., Lee S.E. et al. (2011) Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (vorinostat) up-regulates progranulin transcription: rational therapeutic approach to frontotemporal dementia. J. Biol. Chem., 6, 16101–16108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Marks P.A. and Dokmanovic M. (2005) Histone deacetylase inhibitors: discovery and development as anticancer agents. Expert. Opin. Investig. Drugs, 14, 1497–1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Siebzehnrubl F.A., Buslei R., Eyupoglu I.Y., Seufert S., Hanhen E. and Bluncke I. (2007) Histone deacetylase inhibitors increase neuronal differentiation in adult forebrain precursor cells. Exp. Brain Res., 176, 672–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Franci G., Casalino L., Petraglia F., Miceli M., Menafra R., Radic B., Tarallo V., Vitale M., Scarfò M., Pocsfalvi G. et al. (2013) The class I-specific HDAC inhibitor MS-275 modulates the differentiation potential of mouse embryonic stem cells. Biol. Open., 22, 1070–1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Koivisto A.M., Ala-Mello S., Lemmelä S., Komu H.A., Rautio J. and Järvelä I. (2007) Screening of mutations in the PHF8 gene and identification of a novel mutation in a Finnish family with XLMR and cleft lip/cleft palate. Clin. Genet., 72, 145–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shoubridge C., Tan M.H., Seiboth G. and Gécz J. (2012) ARX homeodomain mutations abolish DNA binding and lead to a loss of transcriptional repression. Hum. Mol. Genet., 21, 1639–1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Collombat P., Mansouri A., Hecksher-Sorensen J., Serup P., Krull J., Gradwohl G. and Gruss P. (2003) Opposing actions of Arx and Pax4 in endocrine pancreas development. Genes Dev., 17, 2591–2603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang T., Guo H., Xiong B., Stessman H.A., Wu H., Coe B.P., Turner T.N., Liu Y., Zhao W., Hoekzema K. et al. (2016) De novo genic mutations among a Chinese autism spectrum disorder cohort. Nat. Commun., 7, 13316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sanders S.J., Campbell A.J., Cottrell J.R., Moller R.S., Wagner F.F., Auldridge A.L., Bernier R.A., Catterall W.A., Chung W.K., Empfield J.R. et al. (2018) Progress in understanding and treating SCN2A-mediated disorders. Trends neurosci., 41, 442–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fassio A., Patry L., Congia S., Onofri F., Piton A., Gauthier J., Pozzi D., Messa M., Defranchi E., Fadda M. et al. (2011) SYN1 loss-of-function mutations in autism and partial epilepsy cause impaired synaptic function. Hum. Mol. Genet., 20, 2297–2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chang Q., Khare G., Dani V., Nelson S. and Jaenisch R. (2006) The disease progression of Mecp2 mutant mice is affected by the level of BDNF expression. Neuron, 49, 341–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Selten M., van Bokhoven H. and Nadif Kasri N. (2018) Inhibitory of the excitatory/inhibitory balance in psychiatric disorders. F1000Res., 8, 7–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Baj G., Leone E., Chao M.V. and Tongiorgi E. (2011) Spatial segregation of BDNF transcripts enables BDNF to differentially shape distinct dendritic compartments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 108, 16813–16818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Martìnez-Levy G.A., Rocha L., Rodrìguez-Pineda F., Alonso-Vanegas M.A., Nani A., Buentello-Garcìa R.M., Briones-Velasco M., San-Juan D., Cienfuegos J. and Cruz-Fuentes C.S. (2018) Increased expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor transcripts I and VI, cAMP response element binding, and glucocorticoid receptor in the cortex of patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Mol. Neurobiol., 55, 3698–3708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Isackson P.J., Huntsman M.M., Murray K.D. and Gall C.M. (1991) BDNF mRNA expression is increased in adult rat forebrain after limbic seizures: temporal patterns of induction distinct from NGF. Neuron, 6, 937–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Benevento M., Iacono G., Selten M., Ba W., Oudakker A., Frega M., Keller J., Mancini R., Lewerissa E., Kleefstra T. et al. (2016) Histone methylation by the Kleefstra syndrome protein EHMT1 mediates homeostatic synaptic scaling. Neuron, 91, 341–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mariani L., Lussi Y.C., Vandamme J., Riveiro A. and Salcini A.E. (2016) The H3K4me3/2 histone demethylase RBR-2 controls axon guidance by repressing the actin-remodeling gene wsp-1. Development, 143, 851–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Niu W., Lu Z.J., Zhong M., Sarov M., Murray J.I., Brdlik C.M., Janette J., Chen C., Alves P., Preston E. et al. (2011) Diverse transcription factor binding features revealed by genome-wide ChIP-seq in C. elegans. Genome Res., 21, 245–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lussi Y.C., Mariani L., Friis C., Peltonen J., Myers T.R., Krag C., Wong G. and Salcini A.E. (2016) Impaired removal of H3K4 methylation affects cell fate determination and gene transcription. Development, 143, 3751–3762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sarafi-Reinach T.R., Melkman T., Hobert O. and Sengupta P. (2011) The lin-11 LIM homeobox gene specifies olfactory and chemosensory neuron fates in C. elegens. Development, 128, 3269–3281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lui N.C., Tam W.Y., Gao C., Huang J.D., Wang C.C., Jiang L., Yung W.H. and Kwan K.M. (2017) Lhx1/5 control dendritogenesis and spine morphogenesis of Purkinje cells via regulation of Espin. Nat. Commun., 8, 15079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Topalidou I., van Oudenaarden A. and Chalfie M. (2011) Caenorhabditis elegans aristaless/Arx gene alr-1 restricts variable gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 8, 4063–4068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Melkman T. and Sengupta P. (1990) Regulation of chemosensory and GABAergic motor neuron development by the C. elegans Aristaless/Arx homolog alr-1. Development, 132, 1935–1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. McIntire S.L., Jorgensen E., Kaplan J. and Horvitz H.R. (1993) The GABAergic nervous system of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature, 364, 337–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wu J.Q., Habegger L., Noisa P., Szekely A., Qiu C., Hutchison S., Raha D., Egholm M., Lin H., Weissman S. et al. (2010) Dynamic transcriptomes during neural differentiation of human embryonic stem cells revealed by short, long, and paired-and sequencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 107, 5254–5259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Iwase S., Brookes E., Agarwal S., Badeaux A.I., Ito H., Vallianatos C.N., Tomassy G.S., Kasza T., Lin G., Thompson A. et al. (2016) A mouse model of X-linked intellectual disability associated with impaired removal of histone methylation. Cell Rep., 9, 1000–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Schenkel L.C., Aref-Eshghi E., Skinner C., Ainsworth P., Lin H., Paré G., Rodenhiser D.I., Schwartz C. and Sadikovic B. (2018) Peripheral blood epi-signature of Claes–Jensen syndrome enables sensitive and specific identification of patients and healthy carriers with pathogenic mutations in KDM5C. Clin. Epigenetics, 10, 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bend E.G., Aref-Eshghi E., Everman D.B., Rogers R.C., Cathey S.S., Prijoles E.J., Lyons M.J., Davis H., Clarkson K., Gripp K.W. et al. (2019) Gene domain-specific DNA methylation episignatures highlight distinct molecular entities of ADNP syndrome. Clin. Epigenetics., 11, 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Aref-Eshghi E., Bourque D.K., Kerkhof J., Carere D.A., Ainsworth P., Sadikovic B., Armour C.M. and Lin H. (2019) Genome-wide DNA methylation and RNA analyses enable reclassification of two variants of uncertain significance in a patient with clinical Kabuki syndrome. Hum. Mutat., 40, 1684–1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sadikovic B., Aref-Eshghi E., Levy M.A. and Rodenhiser D. (2019) DNA methylation signatures in mendelian developmental disorders as a diagnostic bridge between genotype and phenotype. Epigenomics., 11, 563–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Siu M.T., Butcher D.T., Turinsky A.L., Cytrynbaum C., Stavropoulos D.J., Walker S., Caluseriu O., Carter M., Lou Y., Nicolson R. et al. (2019) Functional DNA methylation signatures for autism spectrum disorder genomic risk loci: 16p11.2 deletions and CHD8 variants. Clin. Epigenetics., 16, 103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Talebizadeh Z., Shah A. and DiTacchio L. (2019) The potential role of a retrotransposed gene and a long noncoding RNA in regulating an X-linked chromatin gene (KDM5C): novel epigenetic mechanism in autism. Autism Res., 12, 1007–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. De Rubeis S., He X., Goldberg A.P., Poultney C.S., Samocha K., Cicek A.E., Kou Y., Liu L., Fromer M., Walker S. et al. (2014) Synaptic, transcriptional, and chromatin genes disrupted in autism. Nature, 515, 209–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Johnson M.R., Shkura K., Langley S.R., Delahaye-Duriez A., Srivastava P., Hill W.D., Rackham O.J., Davies G., Harris S.E., Moreno-Moral A. et al. (2016) Systems genetics identifies a convergent gene network for cognition and neurodevelopmental disease. Nat. Neurosci., 19, 223–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Riveiro A.R., Mariani L., Malmberg E., Amendola P.G., Peltonen J., Wong G. and Salcini A.E. (2017) JMJD-1.2/PHF8 controls axon guidance by regulating Hedgehog-like signaling. Development, 144, 856–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Riessland M., Kaczmarek A., Schneider S., Swoboda K.J., Lohr H., Bradler C., Grysko V., Dimitriadi M., Hosseinibarkooie S., Torres-Benito L. et al. (2017) Neurocalcin delta suppression protects against spinal muscular atrophy in humans and across species by restoring impaired endocytosis. Am. J. Human Genet., 100, 297–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Gallotta I., Mazzarella N., Donato A., Esposito A., Chaplin J.C., Castro S., Zampi G., Battaglia G.S., Hilliard M.A., Bazzicalupo P. et al. (2016) Neuron-specific knock-down of SMN1 causes neuron degeneration and death through an apoptotic mechanism. Hum. Mol. Genet., 25, 2564–2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Nakano Y., Kelly M.C., Rehman A.U., Boger E.T., Morell R.J., Kelley M.W., Friedman T.B. and Bánfi B. (2018) Defects in the alternative splicing-dependent regulation of REST cause deafness. Cell, 174, 536–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sharma S. and Taliyan R. (2015) Transcriptional dysregulation in Huntington’s disease: the role of histone deacetylases. Pharmacol. Res., 100, 157–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Koppel I. and Timmusk T. (2013) Differential regulation of Bdnf expression in cortical neurons by class-selective histone deacetylase inhibitors. Neuropharmacology, 75, 106–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Ibhazehiebo K., Gavrilovici C., de la Hoz C.L., Ma S.C., Rehak R., Kaushik G., Meza Santoscoy P.L., Scott L., Nath N., Kim D.Y. et al. (2018) A novel metabolism-based phenotypic drug discovery platform in zebrafish uncovers HDACs 1 and 3 as a potential combined anti-seizure drug target. Brain, 141, 744–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Fico A., Manganelli G., Simeone M., Guido S., Minchiotti G. and Filosa S. (2008) High-throughput screening-compatible single-step protocol to differentiate embryonic stem cells in neurons. Stem. Cells Dev., 17, 573–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Zanin E., Dumont J., Gassmann R., Cheeseman I., Maddox P., Bahmanyar S., Carvalho A., Niessen S., Yates J.R. 3rd, Oegema K. et al. (2011) Affinity purification of protein complexes in C. elegans. Methods Cell. Biol., 106, 289–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Brenner S. (1974) The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics, 77, 71–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Chalfie M. and Sulston J. (1981) Developmental genetics of the mechanosensory neurons of Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol., 82, 358–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.