Abstract

Objectives. To quantify the association between personal and family history of criminal justice system (CJS) involvement (PHJI and FHJI, respectively), health outcomes, and health-related behaviors.

Methods. We examined 2017 New York City Community Health Survey data (n = 10 005) with multivariable logistic regression. We defined PHJI as ever incarcerated or under probation or parole. FHJI was CJS involvement of spouse or partner, child, sibling, or parent.

Results. We found that 8.9% reported only FHJI, 5.4% only PHJI, and 2.9% both FHJI and PHJI (mean age = 45.4 years). Compared with no CJS involvement, individuals with only FHJI were more likely to report fair or poor health, hypertension, diabetes, obesity, depression, heavy drinking, and binge drinking. Respondents with only PHJI reported more fair or poor health, asthma, depression, heavy drinking, and binge drinking. Those with both FHJI and PHJI were more likely to report asthma, depression, heavy drinking, and binge drinking.

Conclusions. New York City adults with personal or family CJS involvement, or both, were more likely to report adverse health outcomes and behaviors.

Public Health Implications. Measuring CJS involvement in public health monitoring systems can help to identify important health needs, guiding the provision of health care and resource allocation.

Involvement in the criminal justice system (CJS) can take many different forms, including incarceration in jail or prison, or probation or parole supervision in the community. Having a close family member with one of these experiences also constitutes a form of involvement in the CJS. In 2016, 6.6 million individuals were under the supervision of adult correctional systems in the United States, including nearly 2.2 million held in jail or prison and approximately 4.5 million people on probation or parole.1,2 In New York City in 2017, there were approximately 50 000 jail discharges,3 19 000 people on parole,4 and more than 19 000 people on probation.5 Family members and communities are also indirectly touched by the CJS. At least half of adults incarcerated in US federal and state prisons are parents.6 In 2015, there were an estimated 33 000 children in New York City who had a parent with a history of incarceration (Bureau of Epidemiology Services, e-mail communication, May 8, 2017).

In the United States, CJS involvement has a disproportionate impact on Black and Latino individuals, a population already experiencing higher prevalence of chronic health conditions, higher rates of morbidity and mortality across myriad adverse health outcomes, and persistent disparities in quality of and access to health care as compared with White individuals.7 Recent research suggests that CJS involvement has a role in these differences. A nascent but growing body of literature documents the association between a history of jail or prison incarceration and a range of adverse health outcomes, including mental illness,8 alcohol and substance use,9,10 cardiovascular disease,11,12 hypertension,12,13 diabetes,12,13 hepatitis C,12 HIV,14,15 and premature mortality.16 More recent research on adverse health outcomes among partners and children of incarcerated people17–19 suggests that indirect CJS involvement may have consequences on the health of family members. While these studies draw attention to the relationship between CJS involvement and health, most have relied on small sample sizes and have focused on measuring either the health of individuals or that of their family members.

To our knowledge, there are no population-level studies that have explored both direct and indirect CJS involvement and its association with health outcomes and behaviors. To further our understanding of the role of different types of CJS involvement on health, we examined the association between a history of personal or family member CJS involvement and health behaviors and outcomes among New York City adults.

METHODS

In this study, we utilized data from the 2017 New York City Community Health Survey (CHS), a cross-sectional, computer-assisted landline and cellular telephone survey of noninstitutionalized New York City residents aged 18 years and older (n = 10 005). Conducted annually by the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene since 2002, the CHS collects sociodemographic data as well as information on physical and mental health, lifestyle factors, and health care access. A stratified random sampling method is employed with respondents sampled according to United Hospital Fund neighborhood designation. Interviews were conducted in English, Spanish, Russian, and Chinese; in 2017, 85.6% of people who were contacted and eligible participated in the survey.20,21

We weighted 2017 CHS data to represent the New York City adult residential population (n = 6 573 000; adjusted mean age = 45.4 years) by adjusting for the probability of selection, gender, race/ethnicity, age, number of adults in the household, presence of children in the household, marital status, and educational attainment level according to the American Community Survey 2016.

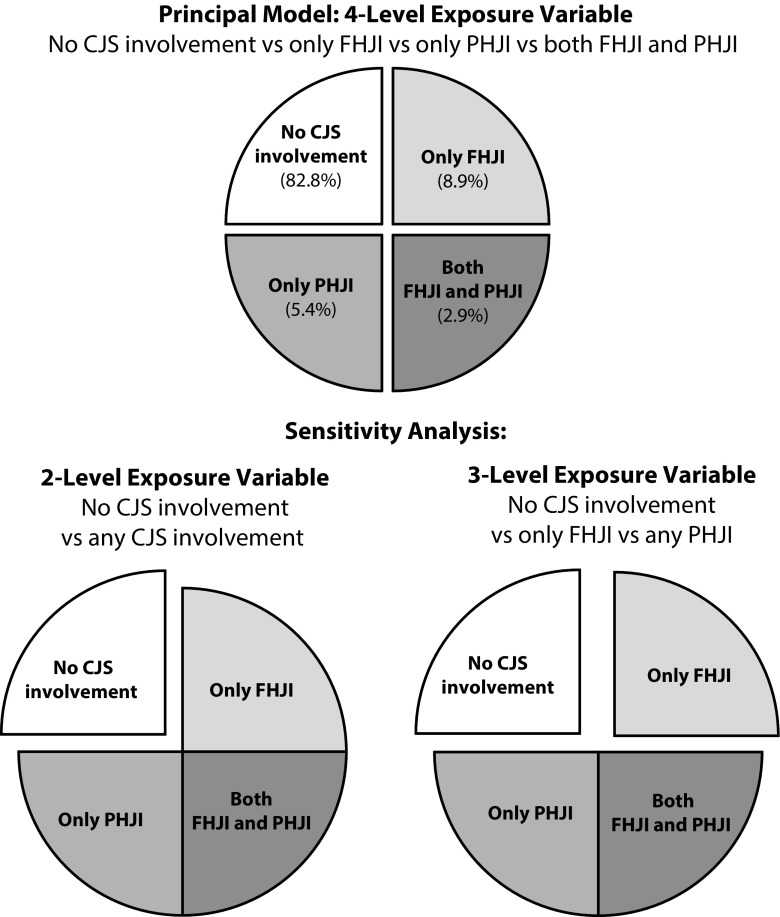

We used 2 CHS questions to define our exposure of interest, self-reported CJS involvement. We assessed personal history of CJS involvement (PHJI) by asking “Have you ever in your life spent any amount of time in a juvenile or adult correctional facility, jail, prison, or detention center, or under probation or parole supervision?” We assessed family history of CJS involvement (FHJI) by asking “Has an immediate family member such as a spouse or partner, child, sibling, or parent ever spent any amount of time in a juvenile or adult correctional facility, jail, prison, or detention center or under probation or parole supervision?” We derived a 4-level variable with mutually exclusive CJS involvement categories as follows: (1) no CJS involvement, (2) only family history of CJS involvement (only FHJI), (3) only personal history of CJS involvement (only PHJI), and (4) both family history and personal history of CJS involvement (both FHJI and PHJI; Figure 1).

FIGURE 1—

Age-Adjusted Prevalence of Criminal Justice System (CJS) Involvement Categories Among New York City Adults: New York City Community Health Survey, 2017

Note. FHJI = family history of criminal justice system involvement; PHJI = personal history of criminal justice system involvement. Data were weighted to the adult residential population per the American Community Survey 2016.

For all analyses, we excluded the 160 individuals who did not respond to both of the CJS involvement questions; this includes 22 respondents who answered only 1 CJS involvement question and were missing the other. A sensitivity analysis that included those 22 respondents and compared any CJS involvement with none did not change our findings (data not shown).

We explored a number of health behaviors and outcomes. We based general health status on self-rating of health from excellent to poor, and dichotomized as fair or poor versus good, very good, or excellent. Respondents were asked if they had ever been told by a doctor, nurse, or other health professional that they had (1) hypertension; (2) diabetes, excluding during pregnancy; or (3) asthma. We used self-reported height and weight to calculate body mass index; respondents with a body mass index of 30 or higher were categorized as having obesity. Current depression in the past 2 weeks was based on the 8-item Patient Health Questionnaire score of 10 or higher (range = 0–24).22 We defined heavy drinking as having a daily average of more than 2 drinks for men and more than 1 drink for women. We defined binge drinking as having 5 or more drinks for men and 4 or more drinks for women on a single occasion in the last 30 days.

We calculated age-adjusted prevalence estimates of sociodemographic characteristics and health behaviors and outcomes for each CJS involvement category (PROC DESCRIPT23); we used CONTRAST23 statements to perform 2-tailed tests of significance (α = 0.05). Multivariable logistic regression models evaluated the association between CJS involvement and selected health behaviors and outcomes (PROC RLOGIST and PRED_EFF23 for pairwise comparisons). As most outcomes were relatively common (prevalence > 10%), we used the ADJRR23 statement to obtain model-adjusted risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs); this approach computes the ratio of predicted marginal proportions for logistic regression models.

We conducted all principal analyses by using the 4-level CJS exposure variable, which compared outcomes between individuals with no CJS involvement versus only FHJI versus only PHJI versus both FHJI and PHJI (Figure 1). To assess the relative importance of PHJI and FHJI, we conducted sensitivity analyses by using 2 alterative models with different definitions of CJS involvement: (1) using a 2-level CJS involvement variable to assess the impact of any CJS involvement: no CJS involvement versus any CJS involvement (FHJI or PHJI, or both FHJI and PHJI) and (2) using a 3-level CJS involvement variable to assess the impact of any personal versus only family history of CJS involvement: no CJS involvement versus only FHJI versus any PHJI (Figure 1).

We included age as a covariate in every multivariable model; we considered additional covariates (1) if they were not plausibly within the causal pathway between history of CJS involvement and adverse health behaviors and outcomes to avoid eliminating any indirect effect, through the potential mediator, of our exposure of interest on the outcome; (2) if they did not have a high degree of missingness; (3) if they had a bivariate association of a P level of less than .10 with CJS involvement; and (4) if removing them from an adjusted model caused a change of greater than 15% in the coefficient for the primary CJS involvement variable of interest (4-level variable). To determine whether the strength of the association differed by gender (male, female) or by race/ethnicity (Black, Latino, White/Asian/Pacific Islander/Other), we tested 2-way interaction terms (α = .1). We made no adjustments for multiple comparison testing. A power calculation performed at the time of study design concluded that we would have at least 80% power to find a minimum 5% difference in outcome risk using a 2-tailed test (α = .05). We conducted all analyses with SAS-callable SUDAAN software (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC) to account for the complex survey design.

RESULTS

Among respondents, 17.2% reported any CJS involvement (weighted n = 1 117 000); 8.9% reported only FHJI (weighted n = 574 000), 5.4% only PHJI (weighted n = 352 000), and 2.9% both FHJI and PHJI (weighted n = 191 000; Table 1). When we used age-adjusted prevalence estimates, respondents with only FHJI were more likely than were those with no CJS involvement to be female, to be Black, to be US-born, to not be married or partnered, and to be living at 200% or higher of the federal poverty level (according to 2017 Department of Health and Human Services guidelines: https://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty-guidelines), and were less likely to have graduated college. Respondents with only PHJI were more likely than were those with no CJS involvement to be male, to be Black or Latino, to be US-born, to not be married or partnered, and to have less than a high-school education. Relative to people with no CJS involvement, people who reported both FHJI and PHJI were more likely to be male, to be Black, to be US-born, to not be married or partnered, to not own their home, and to have completed some college but not to have graduated from college.

TABLE 1—

Age-Adjusted Prevalence of Sociodemographic Characteristics, Health-Related Behaviors and Health Outcomes by Criminal Justice System (CJS) Involvement Among New York City Adults: New York City Community Health Survey, 2017

| Only Family History of CJS Involvement (n = 574 000; 8.9%) |

Only Personal History of CJS Involvement (n = 352 000; 5.4%) |

Both Family and Personal History of CJS Involvement (n = 191 000; 2.9%) |

|||||

| No CJS Involvement (n = 5 348 000; 82.8%), % | % | P | % | P | % | P | |

| Male | 44.4 | 32.8 | < .01 | 84.4 | < .01 | 68.1 | < .01 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| Non-Latino White | 37.3 | 27.0 | < .01 | 30.6 | .044 | 25.6 | < .01 |

| Non-Latino Black | 18.9 | 35.6 | < .01 | 28.8 | < .01 | 44.1 | < .01 |

| Latino | 26.5 | 29.6 | .18 | 33.9 | .023 | 25.1 | .7 |

| Non-Latino Asian/Pacific Islander | 15.5 | 3.5 | < .01 | 5.3 | < .01 | 0.9a | < .01 |

| Non-Latino other | 1.8 | 4.4 | .009 | 1.4a | .51 | 4.3a | .09 |

| US born (vs foreign born) | 47.4 | 74.2 | < .01 | 67.1 | < .01 | 87.3 | < .01 |

| Not married or partnered (vs married or partnered) | 49.2 | 62.7 | < .01 | 65.4 | < .01 | 58.7 | .022 |

| ≥ 200% federal poverty levelb (vs < 200% federal poverty level) | 56.6 | 62.5 | .016 | 54.0 | .45 | 52.7 | .37 |

| Owns home (vs does not own home) | 36.6 | 32.8 | .12 | 30.0 | .054 | 21.6 | < .01 |

| Education | |||||||

| Less than high school | 17.7 | 17.0 | .71 | 28.7 | < .01 | 21.9 | .24 |

| High-school graduate | 23.9 | 20.6 | .1 | 29.9 | .06 | 30.5 | .11 |

| Some college | 21.4 | 30.8 | < .01 | 25.1 | .2 | 34.6 | < .01 |

| College graduate | 37.0 | 31.6 | .026 | 16.3 | < .01 | 13.1 | < .01 |

| Health-related behaviors and outcomes | |||||||

| Fair or poor health | 22.0 | 28.1 | .006 | 30.6 | < .01 | 23.9 | .6 |

| Hypertension | 26.8 | 33.9 | < .01 | 31.5 | .09 | 35.2 | .007 |

| Diabetes | 11.0 | 15.2 | .01 | 13.3 | .28 | 10.5 | .8 |

| Obesity | 23.7 | 31.9 | < .01 | 29.8 | .047 | 35.7 | .006 |

| Asthma | 12.1 | 16.4 | .019 | 21.6 | < .01 | 24.0 | < .01 |

| Current depression | 7.9 | 14.9 | < .01 | 12.8 | .026 | 17.5 | < .01 |

| Heavy drinking | 4.7 | 9.3 | < .01 | 12.4 | < .01 | 14.7 | < .01 |

| Binge drinking | 15.1 | 22.7 | < .01 | 33.9 | < .01 | 31.6 | < .01 |

Note. Data were weighted to the adult residential population per the American Community Survey 2016 and age-adjusted to the US 2000 standard population.

Estimate should be interpreted with caution because of large relative standard error.

According to 2017 Department of Health and Human Services guidelines: https://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty-guidelines.

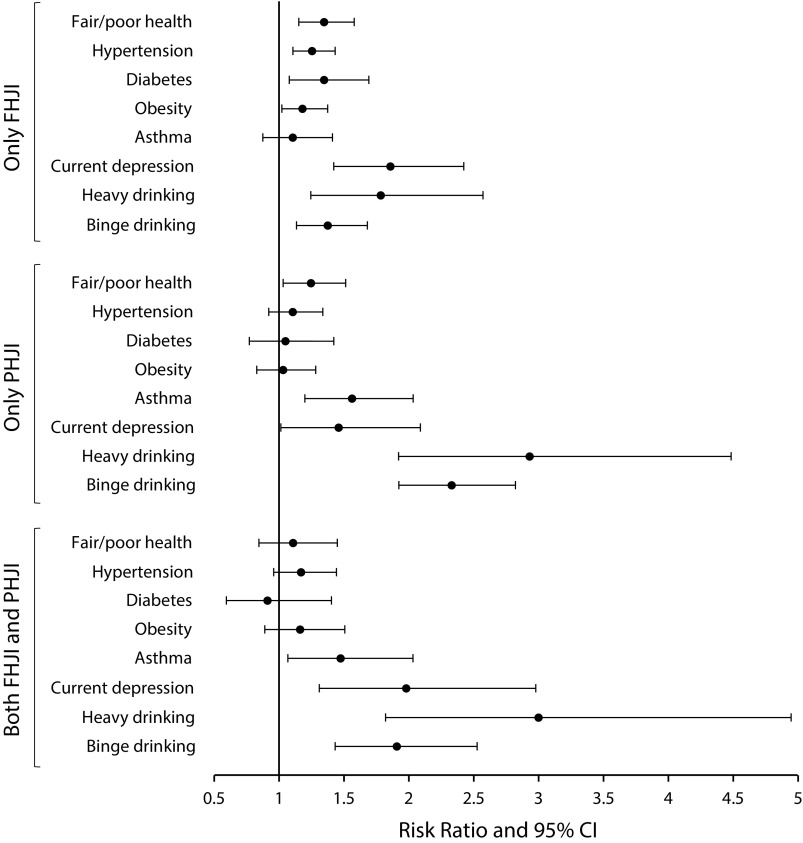

As compared with people who reported no CJS involvement, the age-adjusted prevalence of all health behaviors and outcomes was significantly greater among respondents with only FHJI (Table 1). Respondents with only PHJI were more likely to report fair or poor health, obesity, asthma, current depression, heavy drinking, and binge drinking than were those with no CJS involvement. Those with both FHJI and PHJI were more likely to report hypertension, obesity, asthma, current depression, heavy drinking, and binge drinking compared with those with no CJS involvement. The results from the multivariable model with the 4-level CJS involvement variable, adjusted for age, US nativity, and education level are presented in Figure 2. Compared with those with no CJS involvement, individuals with only FHJI were more likely to report fair or poor health (RR = 1.3; 95% CI = 1.2, 1.6), hypertension (RR = 1.3; 95% CI = 1.1, 1.4), diabetes (RR = 1.3; 95% CI = 1.1, 1.7), obesity (RR = 1.2; 95% CI = 1.0, 1.4), current depression (RR = 1.9; 95% CI = 1.4, 2.4), heavy drinking (RR = 1.8; 95% CI = 1.2, 2.6), and binge drinking (RR = 1.4; 95% CI = 1.1, 1.7). Respondents with only PHJI were more likely to report fair or poor health (RR = 1.2; 95% CI = 1.0, 1.5), asthma (RR = 1.6; 95% CI = 1.2, 2.0), current depression (RR = 1.5; 95% CI = 1.0, 2.1), heavy drinking (RR = 2.9; 95% CI = 1.9, 4.5), and binge drinking (RR = 2.3; 95% CI = 1.9, 2.8) than were those with no CJS involvement. Those with both FHJI and PHJI were more likely to report asthma (RR = 1.5; 95% CI = 1.1, 2.0), current depression (RR = 2.0; 95% CI = 1.3, 3.0), heavy drinking (RR = 3.0; 95% CI = 1.8, 4.9), and binge drinking (RR = 1.9; 95% CI = 1.4, 2.5) than were those with no CJS involvement.

FIGURE 2—

Adjusted Risk Ratios for Health-Related Behaviors and Health Outcomes by Criminal Justice System (CJS) Involvement Among New York City Adults: New York City Community Health Survey, 2017

Note. CI = confidence interval; FHJI = family history of criminal justice system involvement; PHJI = personal history of criminal justice system involvement. Data were weighted to the adult residential population per the American Community Survey 2016. Multivariable models were adjusted for age, US nativity, and education level.

Testing for effect measure modification did not signal a significant difference in the association between CJS involvement and health outcomes by gender or by race/ethnicity. In analyses stratified by gender (Appendix, Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org), in general, point estimates for adverse health behaviors and outcomes tended to be higher among women than men, even if differences were not statistically significant. Women with only FHJI were more likely to report adverse general health, chronic disease, mental health, and heavy and binge drinking, whereas men with only FHJI were more likely to report diabetes. Female respondents with only PHJI were more likely to report fair or poor health and current depression, whereas men with only PHJI were more likely to report heavy drinking. Among the group with both FHJI and PHJI, men were more likely to report asthma. We also observed numerous differences across race/ethnicity categories (Appendix, Table B). With the exception of heavy and binge drinking, few significant health findings emerged among Blacks and Latinos across nearly all CJS involvement categories. White, Asian/Pacific Islander, and other race/ethnicity respondents with only FHJI were more likely to report diabetes, and those with only PHJI were more likely to report asthma; we observed elevated risk of reporting current depression and heavy and binge drinking across all CJS involvement categories.

We also observed the association of CJS involvement with adverse health behaviors and outcomes in sensitivity analyses that used different definitions of CJS involvement. When we used a 2-level variable, people with any CJS involvement (FHJI or PHJI, or both FHJI and PHJI) were more likely to report fair or poor health, hypertension, asthma, current depression, heavy drinking, and binge drinking (Appendix, Table C) relative to people with no CJS involvement. With the 3-level CJS involvement variable, findings for the only FHJI group were identical to the only FHJI group in the 4-level variable. Those with any PHJI were more likely to report fair or poor health, asthma, current depression, heavy drinking, and binge drinking (Appendix, Table D) as compared with those without CJS involvement.

DISCUSSION

Nearly 1 in 6 adults in New York City, an estimated 1.1 million people, reported personal or family involvement in the CJS. We found this population more likely to report a number of adverse health behaviors and outcomes relative to those who have no CJS involvement history. People experiencing only FHJI had greater risk for self-report of virtually all health behaviors and conditions. However, the most striking and persistent were for mental health and both heavy and binge drinking, also observed among people with only PHJI as well as among those with both FHJI and PHJI. Furthermore, we found greater risk of reporting fair or poor health among people with only PHJI as well as higher self-report of asthma among those with only PHJI and among those with both FHJI and PHJI. These findings were robust to sensitivity analyses that used different definitions of CJS involvement. To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine self-report of health outcomes among individuals with personal, close family member, or with both personal and family member CJS experience.

To date, most research on the relationship between CJS involvement and health has focused on individuals with PHJI, generally concluding that they experience poorer health relative to people without PHJI.8–16 Our findings of increased self-report of adverse health conditions among people with only PHJI living in their home communities are similar to past research conducted among people who are incarcerated. However, by contrast with most studies on people with PHJI, we examined a range of physical and mental health conditions and risky drinking behaviors, and therefore illustrated the breadth of outcomes associated with CJS involvement.

The increased prevalence of adverse health behaviors and outcomes we observed among people with only FHJI is consistent with national population-level research in which women with currently incarcerated family members exhibited greater odds of obesity, cardiovascular disease (heart attack or stroke), fair or poor health,18 and poor mental health (major depression and life dissatisfaction).24 Past studies have also observed increased odds of chronic diseases and mental health conditions19 and of adverse health behaviors17 in young adults having experienced parental incarceration in childhood. To our knowledge, this research is the first to examine PHJI and FHJI in the same population, allowing us not only to separately assess the association of each with health but also to assess them together. Our findings suggest that indirect CJS involvement may be as strongly associated with poor health as direct CJS involvement.

The findings about the health of people who have experienced both FHJI and PHJI are an intriguing feature of this study. Contrary to our expectation that joint experience of indirect and direct CJS involvement would be associated with increased adverse health risks, the magnitude of difference was only greatest for current depression among people with both FHJI and PHJI; this may be attributable, at least in part, to the smaller number of individuals with both FHJI and PHJI.

Notwithstanding the absence of statistical significance of the interaction terms, the analyses stratified by gender and by race/ethnicity suggest that there may be differences in the health of subpopulations that have experienced CJS involvement. In particular, RR point estimates for women were generally larger in magnitude across all CJS involvement categories as compared with those of their male counterparts. Given the predominance of women among respondents with only FHJI (67.2%), this finding may be in part related to the consistently higher RRs for self-reported adverse health behaviors and outcomes observed among the only-FHJI group in the principal analysis. Our analyses make evident the CJS exposure women may experience and suggest that either direct, indirect, or both direct and indirect CJS experience may contribute to physical and mental health risks, consistent with past studies that generally considered one or the other type of exposure.12,25

That involvement in the CJS could have an impact on health is expected. Alexander characterizes the penal system in the United States as a racialized system of social control, perpetuating the repression and criminalization of Black communities first imposed through slavery, later by way of Jim Crow laws, and most recently as unprecedented rates of incarceration in service of the War on Drugs.26,27 As such, CJS involvement may be a marker of discrimination and other important social determinants of health. Mass incarceration has contributed to deepening structural inequalities in Black and Latino communities, introducing barriers to securing housing, employment, and education.28 In New York City, housing authorities may consider the circumstances regarding a person’s conviction history as a basis to exclude them from public housing for several years, for example. While our findings focus specifically on the influence of CJS involvement on health, it is imperative that the role of other social determinants of health closely related to CJS involvement also continue to be priority areas of public health research and action.

Strengths and Limitations

A major strength of this study was the use of 2017 CHS data, which included information on PHJI and FHJI as well as a number of sociodemographic characteristics and health outcomes, with few missing data. This provided the opportunity to examine the association of direct and indirect experience of CJS involvement with health outcomes in a large weighted sample that is representative of the adult New York City population; availability of an additional year of data in 2018 will allow for a more robust exploration of the relationships between CJS involvement and health. Lastly, our findings are generalizable to New York City and possibly to other large, racially and ethnically diverse urban centers in the United States.

Study limitations included the wording of CHS questions, each of which made reference to different types of CJS involvement (incarceration, probation, and parole) as well as different types of incarceration (jail and prison), which likely incurred heterogeneity in our exposure of interest. In addition, important information about exposure dose, such as timing, frequency, and length of incarceration, was not included in CHS data. All information obtained via the CHS is self-reported, potentially incurring underreporting of information perceived as stigmatizing, such as CJS involvement and risky drinking behaviors. However, past research largely supports the reliability and validity of self-reported CJS involvement29 and health outcomes measured in the CHS.30

People with PHJI may have been underrepresented in our analyses because of high rates of residential instability31 and homelessness,32 which can be barriers to their inclusion in survey efforts, but also because of the CHS’s exclusion of people in institutional settings, such as halfway houses and shelters. This may have resulted in an underestimation of the association of poor health with PHJI.

The cross-sectional nature of the data restricted our ability to assess the temporal relationship of CJS involvement and sociodemographic characteristics with health outcomes and to characterize this relationship as causal. Furthermore, young men may have limited access to health care systems, as a result of lack of insurance coverage and infrequent care seeking. If they only see a doctor because they are admitted into jail or prison, the observed increase in adverse health reporting among PHJI could be partially explained by positive improvements in health care access as a result of more timely diagnosis of previously undetected conditions.

Finally, our analytic models did not include numerous household- and neighborhood-level stressors, such as domestic violence and community disinvestment, found in previous research to be closely related with CJS involvement; these were not measured in the CHS.33 Still, our findings, including the associations with indirect involvement in the CJS, warrant increased investment in research, policy, and programming related to CJS involvement and health. Without this attention, public health may be overlooking a significant contributor to poor health in of some of our most highly burdened communities.

Public Health Implications

Our novel findings on the magnitude and breadth of the association of CJS involvement with the health of individuals and families evidence the importance of CJS involvement as a social determinant of health and a public health concern. While we are cautious about causal inference given our cross-sectional data, we believe that health departments could respond by incorporating measures of CJS involvement into routine population health monitoring to identify groups at greatest risk. The often complex health burden that people with a history of CJS involvement and their families face warrants community-based health care and social service resources that can adequately address their well-being.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank the Survey and Data Analysis Unit, Bureau of Epidemiology Services, NYC DOHMH; Shadi Chamany, MD, MPH; and Ashwin Vasan, MD, PhD, for their support.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

The research protocol was deemed exempt by the NYC DOHMH institutional review board.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kaeble D. Probation and parole in the United States, 2016. US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. 2018. Available at: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/ppus16.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2019.

- 2.Kaeble D, Cowhig M. Correctional populations in the United States, 2016. US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. 2018. Available at: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cpus16.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2019.

- 3.NYC Department of Correction at a glance—information for entire FY2018. New York City Department of Corrections. 2018. Available at: https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doc/downloads/press-release/DOC_At%20a%20Glance-entire_FY%202018_073118.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2019.

- 4.Community Supervision Legislative Report, 2017, New York State Corrections and Community Supervision. 2017. Available at: http://www.doccs.ny.gov/Research/Reports/2017/Legislative_Report.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2019.

- 5.DOP adult cases snapshot by calendar year. New York City Department of Probation. 2018. Available at: https://data.cityofnewyork.us/City-Government/DOP-Adult-Cases-Snapshot-by-Calendar-Year/ph29-5mxy/data. Accessed April 1, 2019.

- 6.Glaze L, Maruschak LM. Parents in prison and their minor children. Special Report. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2010.

- 7.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Institute of Medicine. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steadman HJ, Osher FC, Robbins PC, Case B, Samuels S. Prevalence of serious mental illness among jail inmates. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(6):761–765. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.6.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karberg JC, James DJ. Substance dependence, abuse, and treatment of jail inmates, 2002. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2005.

- 10.James DJ, Glaze LE. Mental health problems of prison and jail inmates. Special Report. US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. 2006. Available at: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/mhppji.pdf. Accessed December 9, 2019.

- 11.Bai JR, Befus M, Mukherjee DV, Lowy FD, Larson EL. Prevalence and predictors of chronic health conditions of inmates newly admitted to maximum security prisons. J Correct Health Care. 2015;21(3):255–264. doi: 10.1177/1078345815587510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maruschak LM, Berzofsky M, Unangst J. Medical problems of state and federal prisoners and jail inmates, 2011–12. Special Report. US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics. 2016. Available at: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/mpsfpji1112.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2019.

- 13.Wilper AP, Woolhandler S, Boyd JW et al. The health and health care of US prisoners: results of a nationwide survey. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(4):666–672. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.144279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spaulding AC, Seals RM, Page MJ, Brzozowski AK, Rhodes W, Hammett TM. HIV/AIDS among inmates of and releasees from US correctional facilities, 2006: declining share of epidemic but persistent public health opportunity. PLoS One. 2009;4(11):e7558. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maruschak LM. HIV in prisons, 2001–2010. US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. 2015. Available at: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/hivp10.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2019.

- 16.Binswanger IA, Stern MF, Deyo RA et al. Release from prison—a high risk of death for former inmates. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(2):157–165. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heard-Garris N, Winkelman TNA, Choi H et al. Health care use and health behaviors among young adults with history of parental incarceration. Pediatrics. 2018;142(3):e20174314. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee H, Wildeman C, Wang EA, Matusko N, Jackson JS. A heavy burden: the cardiovascular health consequences of having a family member incarcerated. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(3):421–427. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee RD, Fang X, Luo F. The impact of parental incarceration on the physical and mental health of young adults. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4):e1188–e1195. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Community Health Survey—methodology. 2019. Available at: https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/data/data-sets/community-health-survey-methodology.page. Accessed March 15, 2019.

- 21.Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 9th ed. American Association for Public Opinion Research; 2016. Available at: https://www.aapor.org/AAPOR_Main/media/publications/Standard-Definitions20169theditionfinal.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Berry JT, Mokdad AH. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2009;114(1-3):163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bieler G. SUDAAN Language Manual, Release 10.0. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wildeman C, Schnittker J, Turney K. Despair by association? The mental health of mothers with children by recently incarcerated fathers. Am Sociol Rev. 2012;77(2):216–243. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wildeman C, Lee H, Comfort M. A new vulnerable population? The health of female partners of men recently released from prison. Womens Health Issues. 2013;23(6):e335–e340. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muhammad KG. The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alexander M. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York, NY: New Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Research Council. The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Research Council. Measurement Problems in Criminal Justice Research: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pierannunzi C, Hu SS, Balluz L. A systematic review of publications assessing reliability and validity of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), 2004–2011. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13(1):49. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herbert CW, Morenoff JD, Harding DJ. Homelessness and housing insecurity among former prisoners. RSF. 2015;1(2):44–79. doi: 10.7758/rsf.2015.1.2.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greenberg GA, Rosenheck RA. Jail incarceration, homelessness, and mental health: a national study. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(2):170–177. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.2.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Western B. Homeward: Life in the Year After Prison. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2018. [Google Scholar]