Abstract

Preemption—when a higher level of government limits the authority of a lower level to enact new policies—has been devastating to tobacco control. We developed a preemption framework based on this experience for anticipating and responding to the possibility of preemption in other public health areas. We analyzed peer-reviewed literature, reports, and government documents pertaining to tobacco control preemption. We triangulated data and thematically analyzed them.

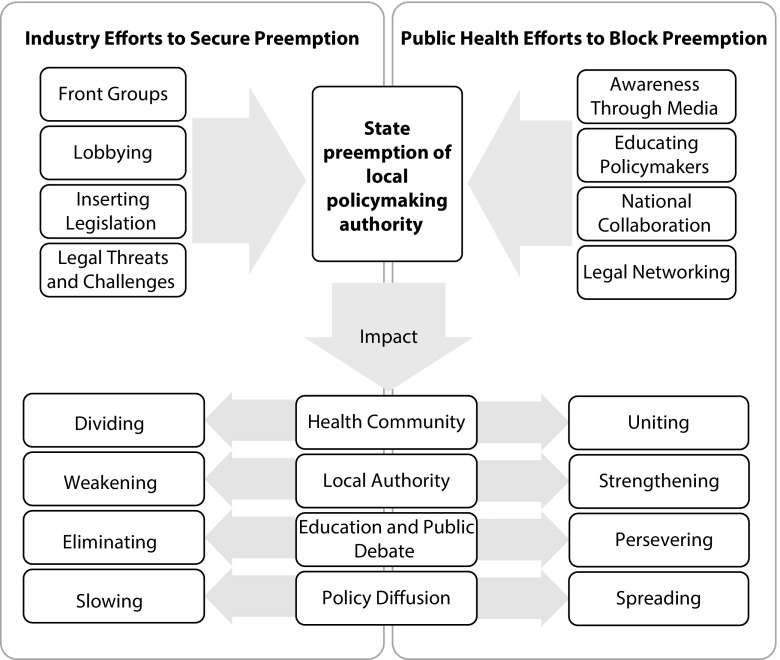

Since the 1980s, tobacco companies have attempted to secure state preemption through front groups, lobbying key policymakers, inserting preemption into other legislation, and issuing legal threats and challenges. The tobacco control community responded by creating awareness of preemption through media advocacy, educating policymakers, mobilizing national collaborations, and expanding networks with the legal community. Ten of the 25 state smoke-free preemption laws have been fully repealed. Repeal, however, took an average of 11 years.

State preemption has been detrimental to tobacco control by dividing the health community, weakening local authority, chilling public education and debate, and slowing local policy diffusion. Health scholars, advocates, and policymakers should use the framework to anticipate and prevent industry use of preemption in other public health areas.

Local governments serve as important testing grounds for introducing public health policy innovations that later influence state and national policy.1 A key tobacco industry strategy to block the diffusion of innovative local laws is preemption, which occurs when a higher level of government (e.g., a state) limits the authority of a lower level (e.g., a city) to enact new laws.2 Whereas floor preemption provides a minimum level of protection, ceiling preemption (as described in this article) sets a maximum level of protection. In some areas, such as inclusionary zoning and civil rights, preemption can limit local laws that promote health inequality.3 In rare cases, federal public health preemption is appropriate, such as the federal airline smoking ban.4 However, state public health preemption usually prevents local governments from enacting laws to address community-specific needs.5 In 2011, the Institute of Medicine concluded that federal and state governments should avoid ceiling preemption because it can often be harmful to innovative local health laws. Higher levels of government should set minimum standards (floor preemption) that allow localities to protect the health and safety of their inhabitants.6

The frequent use of preemption by tobacco companies provides the best case for understanding these trends. Whereas various other industries—including firearms, alcohol, food and beverage—are using preemption to preclude lower levels of government from passing progressive public health measures,2,4,7–13 the tobacco industry has a long, sustained, and largely successful history of securing state preemption. Tobacco companies have used preemption to block, weaken, and delay innovative local tobacco control laws, including clean indoor air, advertising, tax, retailer licensing, and youth access restrictions. To date, researchers have examined particular aspects of preemption,2,14 and although some frameworks exist for decision-makers4 and health advocates,15 none integrate industry practices and the impact of preemption. Recently, scholars have enriched the discussion of preemption by highlighting how preemption is an obstacle to local policymaking,16–18 debunking propreemption arguments,19 and emphasizing the consequences of preemption.20 However, none of these studies synthesize previous evidence on how advocates and policymakers have responded to and resisted preemption.

We propose an integrated framework (Figure 1) that we synthesized from an analysis of the tobacco control experience and its lessons for confronting similar state preemptive attempts in other noncommunicable disease–related areas of public health, such as nutrition and alcohol. The tobacco experience highlights key challenges and opportunities for protecting local authority against industry preemptive attacks and serves as a useful example for the importance of monitoring public health policymaking and conducting comparative research.

FIGURE 1—

Integrated State Preemption Framework

METHODS

Between February 2018 and April 2019, we conducted a comprehensive review on tobacco control preemption using PubMed and Google Scholar as well as tobacco control state reports from the Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education at the University of California, San Francisco (https://tobacco.ucsf.edu/states). The search terms were “preemption,” “preempt,” “tobacco,” “tobacco control,” and “tobacco industry.” We located and reviewed a total of 244 documents. A total of 70 documents, comprising 36 peer-reviewed articles and 34 reports, were deemed relevant on the basis of our inclusion criterion: that each document discussed state preemption of tobacco control in the United States. We excluded any documents pertaining to federal or global preemption or that merely highlighted the existence of preemption. Stanton Glantz, PhD, and Jennifer Pomeranz, JD, should be credited for conducting the bulk of the research on tobacco control preemption, thus laying the foundation for this work and future studies of preemption in public health.

E. C. coded the documents and analyzed the consistent themes across the literature using standard thematic analyses.21 The specific major themes coded were (1) tobacco industry efforts to secure state preemption, (2) public health community responses to preemption, and (3) the impact and effects of state preemption of local tobacco control (Appendix, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

RESULTS

We present an analysis of state preemption in tobacco control that focuses on tobacco industry efforts, health advocacy responses, and consequences for public health.

Tobacco Industry Efforts

Since the 1980s, tobacco companies have been concerned about the diffusion of innovative public health laws in the United States, especially at the local level. Local regulatory battles were demanding and costly.2 A former industry lobbyist noted that local activity drove tobacco companies “crazy,” because when he “put out a fire one place, another one would pop up somewhere else.”22(p199) Local citizens and community organizations also had more influence with local representatives that they “may live next door to.”22 Tobacco interests were viewed as outsiders and “big time lobbyists.”2,22

Beginning in the mid-1980s, tobacco companies embarked on a vigorous campaign to reverse local laws by promoting weak tobacco control legislation at the state level, where industry’s influence was more concentrated.23 By the period 1991 to 1996, there were 17 smoke-free state preemption laws, a 41% increase from the 7 state preemption laws enacted between 1986 and 1991.24 It proved easier and less costly to fight a single state battle than to fight numerous local ones within a state.25,26 One lobbyist noted that the tobacco companies’ “first priority has always been to preempt the field.”22(p199) Tobacco companies have inserted statewide legislation that preempts local smoke-free environments, tobacco retail licensing restrictions, tobacco youth access restrictions, and tobacco tax increases, often as a direct response to local progress.26 We identified 4 key tactics used by the tobacco industry to achieve this (Table 1).

TABLE 1—

Tobacco Industry Efforts to Secure State Preemption and Health Advocacy Responses: United States, 1986–2019

| Industry Efforts to Secure State Preemption |

Public Health Responses to State Preemption |

||||

| Tactic | Objective | Actions | Tactic | Objective | Actions |

| (1) Promoting preemption through front groupsa | Use front groups as a mouthpiece | Distributing brochures, commenting in the media, and writing op-eds and guest columnsb | (1) Creating awareness of preemption through media advocacy | Create public awareness about state preemption and tobacco industry attempts to secure it | Holding press conferences, issuing press releases, distributing flyers and brochures, writing op-edsc |

| (2) Lobbying policymakers | Target politicians in key positions to introduce and secure passage of preemption out of committee | Providing financial contributions and political donations and lobbying high-ranking politicians | (2) Educating policymakers | Educate policymakers about the nature of state preemption and its impact on local control | Writing letters to government officials, testifying during public hearings, and issuing public comments to proposed state preemption legislation |

| Building relationships and alliances with policymakers | |||||

| (3) Inserting statewide preemption through varied legislative channels | Maximize efforts nationwide to adopt preemption legislation | Drafting and introducing new preemption legislation and attaching it to existing bills | (3) Mobilizing national opposition | Maximize efforts nationwide to prevent preemption | Creating a national preemption task force |

| Introducing deceptive legislation | Creating handbooks and campaign materials | ||||

| Introducing direct ballot initiatives | Recruiting prominent national figures to oppose preemption | ||||

| Slipping preemption language into legislation on other issues | |||||

| (4) Issuing legal threats and challenges | Intimidate local governments to chill local policy diffusion | Threatening and suing local governments | (4) Expanding networks within the legal community | Partner with legal community to defend localities | Funding legal resource centers |

| Supporting front groups to file lawsuits | Drafting tobacco control measures to withstand industry challenges | ||||

| Providing legal support to localities | |||||

| Forming a legal consortium | |||||

| Working with state attorneys general | |||||

Tobacco industry front groups include restaurant and hotel associations, restaurant and bar owners, beverage and liquor associations, trade and labor groups, retail merchants, and gaming associations.

Tobacco industry front group key framing messages are that preemption ensures a “level playing field” and “uniformity” and eliminates a “patchwork” of local laws.

Health advocacy key framing messages: positive aspects of “local choice,” “local authority,” and “local control” as well as negative aspects of “state-only control.”

1. Promoting preemption through front groups.

Because of tobacco companies’ declining credibility in the 1980s and 1990s, front groups supported and promoted preemptive state tobacco control laws.2,25 Front group support came from traditional allies such as restaurant associations, hotel associations, restaurant and bar owners, beverage and liquor associations, trade and labor groups, retail merchants, and gaming associations. Several received direct funding from tobacco companies to act as a mouthpiece.

Front groups argued that statewide preemption was necessary to establish “uniform” laws that diminish competitive economic disadvantages for businesses in relation to neighboring communities.26 Preemption would promote fairness among businesses free of government interference,25,26 eliminating a “patchwork” of inconsistent local laws. Tobacco companies produced brochures and editorials supporting “uniform standards” and creating a “level playing field,” slogans later echoed to justify statewide preemptive legislation.

2. Lobbying policymakers.

Tobacco companies have made financial contributions and political donations to state House and Senate representatives willing to introduce statewide preemptive legislation. The industry strategically targeted members of health committees and high-ranking politicians, including Senate presidents, Senate majority leaders, House speakers, and a president pro tempore. These efforts enabled companies to introduce weak state preemptive bills, securing their passage out of committee before full floor votes took place.

3. Inserting statewide preemption through varied legislative avenues.

Tobacco companies lobbied policymakers to introduce (or sponsor) new preemptive tobacco control legislation or to attach amendments or preemption clauses to already existing bills. Companies used deceptive and weak “look alike” bills alongside competing strong bills. They revived bills repeatedly under different names, and snuck in 11th-hour preemption clauses, leaving the public health community with little time to mobilize opposition. Tobacco companies also mounted “look alike” direct ballot initiatives (also known as voter initiatives) in efforts to confuse voters favorable to strong tobacco control ballot initiatives. They slipped preemption into legislative bills focused on other issues, including bills pertaining to property taxes, gambling, pesticides, and education.

4. Issuing legal threats and challenges.

Fearing the growing momentum of local-level progress in tobacco control, companies have threatened local governments with state preemption to deter diffusion to other localities.2 They successfully threatened to sue local governments over tobacco control laws. When the threats failed, tobacco companies sued to secure court rulings that preemption existed when it was unclear or to enforce preemptive laws that had already been passed. Tobacco companies claimed that state laws explicitly or implicitly preempted localities from enacting such measures. Tobacco companies assumed that lawsuits would continue to deter localities, but most cases lost in court because preemption explicitly or implicitly did not exist. Tobacco companies also had front groups file some lawsuits, but these also usually lost in court.

Health Advocacy Responses

National health organizations, including the American Heart Association, American Lung Association, and American Cancer Society, alongside local grassroots organizations, successfully countered state preemption efforts through 4 means (Table 1): media advocacy, educating policymakers, mobilizing national opposition, and expanding legal networks.

Media advocacy.

Advocates from local and national health groups used earned media in several states to promote public awareness about preemption, its impact on local control, and the tobacco industry’s involvement. Media advocacy included press conferences, press releases, flyers and brochures, op-eds, and media interviews. Framing emphasized the positive aspects of “local choice” and “local authority” in contrast with “state-only control.” These messages targeted at the general public and policymakers resonated with citizens and stirred public debates, further enabling local anti-preemption grassroots coalitions to grow. “Local control” messaging gained less traction, sometimes because of industry counternarratives emphasizing government intrusion on personal behavior and private business decisions. Health groups responded by shifting media advocacy to the negatives of “state-only control,” leading some policymakers to reject state preemption legislation. Health advocates in several states also used earned media to educate the public and policymakers about industry attempts to slip preemption into other legislation, to expose industry front groups, and to identify deceptive industry practices surrounding preemption attempts.

Educating policymakers.

Local and national health advocates in several states educated key government officials about the nature of state preemption and its impact on local control. They built relationships with political champions, wrote letters to government officials, testified during public hearings, and issued public comments. When these efforts failed, advocates targeted committee presidents and Senate majority leaders to halt preemptive legislation—similar to what tobacco companies had done. These efforts often synergized with media advocacy promoting local control and the need for transparency about industry’s role in preemption. Advocacy also involved lobbying state governors to veto preemption laws. Advocates urged the public to contact governors and lieutenant governors, resulting in some strongly worded veto messages.

Mobilizing national opposition.

In response to a rapid increase in statewide preemption bills, health organizations formed a national preemption task force in 1994.25 The task force, which expanded in 1996, led to the mobilization of grassroots movements and more coherent counterstrategies and tactics, and it increased capacity and expertise.25 The task force cultivated best practices for countering preemption. These were codified in handbooks and campaign materials, and shared at national conferences.25 Prominent national political figures—including Henry Waxman (D-California), Mike Synar (D-Oklahoma), and Hillary Clinton—became supportive.26 By 1997 through 2008, only 7 states passed state preemptive smoke-free laws, a 72% decline from 1993 to 1996.27 In 2000, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published Healthy People 2010, which sought the elimination of tobacco state preemptive laws. Delaware became the first state to repeal tobacco preemption in 2002. In 2009, the CDC’s Healthy People 2020 renewed the call to eliminate tobacco state preemption.26

Expanding legal networks.

Health advocates forged partnerships with the legal community. Massachusetts, California, Michigan, Minnesota, and Maryland helped fund legal resource centers that worked with local departments of health. These became a vital resource for drafting tobacco control measures that could withstand industry challenges and later for defending these laws when challenged by tobacco companies. Advocates promoted anti-preemption clauses—known as a “savings clause” or “home rule”—that established minimum standards, thus permitting localities to pass laws that shielded against state preemption lawsuits. In 2002, legal resource centers founded a consortium offering technical assistance. It worked with state attorneys general to scrutinize preemption provisions, sometimes offering formal opinions respected by judges, which emboldened localities to pass stricter tobacco laws despite industry litigation threats.

Consequences for Public Health

The public health community’s initial response to state tobacco preemption involved strong disagreements among stakeholders. National health organizations and others initially accepted state preemption as a reasonable compromise for incremental progress. Too much effort, they argued, had gone into passing state tobacco control bills to throw the legislation away; they assumed that these laws could be repealed later. Smaller grassroots organizations, including Americans for Nonsmokers’ Rights, opposed preemption of any kind, arguing that state tobacco control laws were weak and ineffective compared with local ones. For example, weak state preemptive laws would permit designated smoking areas in public places, whereas strong local laws would establish 100% smoke-free environments. The divide within the public health community made it difficult to help policymakers reject preemption laws. Well-intentioned but misguided legislators in several states mistakenly believed that preemption language could be easily removed at a later time.

Preemption also had a chilling effect on building grassroots movement, encouraging debates, opportunities to shift norms,28 raising awareness about the health effects of smoking,23,26 and informing policymakers.29 Enactment of local laws is associated with increased news coverage and higher compliance rates.24 State tobacco preemption eliminated opportunities to shift social norms on the acceptability of smoking,23 which is an important mechanism in smoking cessation and decreased initiation.30

State preemption also significantly halted momentum in the diffusion of strong local tobacco controls, leading to fewer ordinances and reduced support for smoke-free laws,31 especially among smokers.26 Once state preemption laws were in force, local governments experienced significant constraints on enacting progressive policies (e.g., prohibiting smoking in city parks). Local populations with smoke-free laws could dispel negative myths by showing the firsthand evidence of their benefits, especially for smokers.26

Industry’s threats of lawsuits also impeded the diffusion of innovative local public health laws. Upon being legally threatened or sued by industry, some localities have withdrawn, weakened, or delayed tobacco control laws.2 Intimidating localities can lead to a “chilling effect” by casting fear into nearby localities.32

By the early 2000s, health advocates and lawyers working with policymakers in several states to repeal state preemption, but this proved far more difficult than expected.29 In at least 12 states, attempts to repeal preemptive language were unsuccessful.25,28,33–35 Between 2004 and 2009, in only 7 of the 19 states with preemptive smoke-free laws were these laws repealed through anti-preemption legislation, ballot measures, and court rulings.28 As of 2019, only 12 of the 25 state preemption smoke-free laws have been fully repealed, taking an average of 11 years from the date the law was enacted.27 Between 2000 and 2010, the number of preemptive state tobacco advertising laws remained constant at 18, while state youth access restrictions actually increased from 21 to 22.33

DISCUSSION

Our analysis of the US tobacco control experience reveals tobacco industry strategies to secure state preemption, public health community responses to preemption, and the impact and effects of state preemption of local tobacco control. On the basis of this analysis of tobacco preemption, we propose a framework of industry strategies and tactics in relationship to public health advocacy responses and outcomes (Figure 1). Although the framework can continue to be used to analyze and resist preemption in tobacco control (e.g., regulating electronic cigarettes and raising the legal age for purchasing tobacco from 18 to 21 years), it is also intended for use in anticipating preemption in other areas of public health, such as alcohol and nutrition.

The framework underscores the importance of advocates’ use of media messaging in efforts to resist state preemption. Like the tobacco industry, the alcohol, food, and beverage industries work with and fund restaurant and hotel associations and retail merchants to promote state preemption, with messages about the need for a “level playing field” for businesses in different localities.36 Advocacy groups should counter these messages by first exposing these front group ties to the industry. Although advocacy groups should emphasize the importance of “local control,” they should mostly stress the negatives of “state-only control” because voters tend to vote for initiatives when such changes are framed in terms of their potential to avert negative situations (e.g., “state-only control”) rather than to make positive improvements (e.g., importance of local control).

The framework shows that public health advocates must counter industry’s lobbying of high-ranking policymakers with proactive outreach and education on the true nature of preemption bills and industry’s deceptive practices. Advocates’ failure to adequately do precisely this recently led to the preemption of local sugar-sweetened beverage tax increases.7

Figure 1 highlights the importance of national efforts to swing the pendulum on state preemption. Industry will continue to use established networks of front groups and politicians nationally to promote preemption through sneak preemption clauses in the 11th hour, leaving little time to mobilize effective opposition. The beverage industry’s recent efforts to promote state preemption of sugar-sweetened beverage taxes have already caught health advocates off guard. In the last-minute introduction of a state preemption law prohibiting local sugar-sweetened beverage taxes in California, industry used a ballot initiative threatening to end all local taxes as extortion.7

Similar to tobacco control, public health advocates have begun developing handbooks, campaign materials, and toolkits to combat preemption of alcohol control and nutrition policies. Groups including the Local Solutions Support Center, the Campaign to Defend Local Solutions, Grassroots Change, ChangeLab Solutions, and Voices for Healthy Kids (a joint initiative of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the American Heart Association) have created national preemption task forces to mobilize grassroots movements, counter industry strategies and tactics, and increase capacity and legal expertise. These groups should continue to expand their connections with prominent national political figures and leading health agencies (e.g., the CDC) and work together to unify their voices against the harms of the threat of state preemption to public health.

The framework reveals that industry is likely to use the threat of litigation—and actual litigation—to prevent the diffusion of best public health practices.32 The alcohol industry has used this strategy to intimidate local governments and deter local action in alcohol advertising and retail licensing restrictions,2 and the food and beverage industry has begun following suit.37 Advocates in the United States should expand their networks with the legal community through legal resource centers and state attorneys general. Advocates should be more proactive in lobbying policymakers to adopt anti-preemption “home rule savings” clauses that in some states allow the possibility of local action on public health matters, and in other states permit local governments to enact laws shielding against state preemption lawsuits. In nutrition menu labeling and alcohol restrictions, there has been a good start,13 but these efforts should be redoubled.

Advocates for nutritional and alcohol control policies should take note of timing: early failures to match the tobacco industry’s efforts at state preemption divided the public health community, weakening local authority, chilling education and public debate, and slowing policy diffusion. Our framework suggests that public health advocates should be wary of industry divide-and-conquer strategies. The beverage industry in California and Washington pitted unions against health groups7 to encourage acceptance of preemption as a reasonable compromise that could be reversible. A key lesson from tobacco control is that repealing preemption is extremely difficult. Advocacy groups should not agree to accept incremental improvements at the expense of state laws that will thwart local activities that raise public awareness and education, gradually changing social norms.

Limitations

The analysis was confined to the state preemption of local public health laws, although this can occur at higher levels of government. A few authors have discussed national2,12 and global preemption.38–40 Although this material was important background information, analyzing strategies and responses at higher levels of government was out of the scope of this study. Despite several tobacco control state reports, there is a lack of detailed cases within these reports concerning preemption, thereby limiting details in these lessons learned.

Conclusions

A review of tobacco control preemption in the United States reveals the damaging effects that state preemption has had on local tobacco control efforts. Public health scholars and advocates examining continued state preemption efforts in tobacco control and other areas of public health should systematically apply lessons learned from the tobacco experience to identify key industry strategies and effective public health responses, and to prevent the deleterious effects that state preemption can have on local policymaking.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (grant UCSF-CTSI UL1 TR001872), the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, the National Cancer Institute (training grant 2T32 CA113710-11), and the University of Nevada, Reno.

We thank Casey Palmer for providing feedback on this study.

Note. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the University of Nevada, Reno.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts to declare.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

Protocol approval was not needed for this study because it was an analysis of previous literature.

Footnotes

See also Pomeranz, p. 268.

REFERENCES

- 1.Florey K, Doan A. A successful experiment: California’s local laboratories of regulatory innovation. UCLA Law Rev. 2018;4:80–109. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorovitz E, Mosher J, Pertschuk M. Preemption or prevention? Lessons from efforts to control firearms, alcohol, and tobacco. J Public Health Policy. 1998;19(1):36–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silverstein T. Combating state preemption without falling into the local control trap. Poverty & Race Research Action Council, December 1, 2017. Available at: https://prrac.org/combating-state-preemption-without-falling-into-the-local-control-trap. Accessed August 20, 2018.

- 4.Pertschuk M, Pomeranz JL, Aoki JR et al. Assessing the impact of federal and state preemption in public health: a framework for decision makers. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2013;19(3):213–219. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182582a57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stark MJ, Rohde K, Maher JE et al. The impact of clean indoor air exemptions and preemption policies on the prevalence of a tobacco-specific lung carcinogen among nonsmoking bar and restaurant workers. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(8):1457–1463. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.094086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute of Medicine. For the Public’s Health: Revitalizing Law and Policy to Meet New Challenges. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crosbie E, Schillinger D, Schmidt LA. State preemption to prevent local taxation of sugar-sweetened beverages. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(3):291–292. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.7770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pomeranz JL, Pertschuk M. State preemption: a significant and quiet threat to public health in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(6):900–902. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rutkow L, Vernick JS, Hodge JG, Jr, Teret SP. Preemption and the obesity epidemic: state and local menu labeling laws and the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act. J Law Med Ethics. 2008;36:772–789, 611. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2008.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pomeranz JL, Teret SP, Sugarman SD et al. Innovative legal approaches to address obesity. Milbank Q. 2009;87(1):185–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00552.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pomeranz JL, Pertschuk M. Sugar-sweetened beverage taxation in the USA, state preemption of local efforts. Public Health Nutr. 2019;22(1):190. doi: 10.1017/S136898001800304X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pomeranz JL, Mozaffarian D, Micha R. The potential for federal preemption of state and local sugar-sweetened beverage taxes. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(5):740–743. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pomeranz JL, Zellers L, Bare M et al. State preemption of food and nutrition policies and litigation: undermining government’s role in public health. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56(1):47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ashe M, Jernigan D, Kline R et al. Land use planning and the control of alcohol, tobacco, firearms, and fast food restaurants. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(9):1404–1408. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.9.1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bare M, Zellers L, Sullivan PA et al. Combatting and preventing preemption: a strategic action model. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2019;25(2):101–103. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pomeranz JL. Local policymakers’ new role: preventing preemption. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(8):1069–1070. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rutkow L, McGinty MD, Wetter S et al. Local public health policymakers’ views on state preemption: results of a national survey, 2018. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(8):1107–1110. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galea S, Vaughan R. On choosing the right starting question: a public health of consequence, August 2019. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(8):1075–1076. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pomeranz JL, Zellers L, Bare M et al. State preemption: threat to democracy, essential regulation, and public health. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(2):251–252. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Falbe J. Sugar-sweetened beverage taxation: evidence-based policy and industry preemption. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(2):191–192. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guest G, MacQueen KM, Namey EE. Applied Thematic Analysis. London, England: Sage Publications; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crawford VL. Cancer converts tobacco lobbyist: Victor L. Crawford goes on the record. Interview by Andrew A. Skolnick. JAMA. 1995;274(3):199–200, 202. doi: 10.1001/jama.274.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conlisk E, Siegel M, Lengerich E et al. The status of local smoking regulations in North Carolina following a state preemption bill. JAMA. 1995;273(10):805–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chriqui JF, Frosh M, Brownson RC et al. Application of a rating system to state clean indoor air laws (USA) Tob Control. 2002;11(1):26–34. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.1.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yanez E, Cox G, Cooney M, Eadie R. Preemption in public health: the dynamics of clean indoor air laws. J Law Med Ethics. 2003;31(4 suppl):84–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720x.2003.tb00763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mowery PD, Babb S, Hobart R et al. The impact of state preemption of local smoking restrictions on public health protections and changes in social norms. J Environ Public Health. 2012;2012:632629. doi: 10.1155/2012/632629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Americans for Nonsmokers’ Rights. Timeline of state preemption of smokefree air laws, April 2019. Available at: http://www.protectlocalcontrol.org/docs/PreemptionTimeline.pdf. Accessed April 10, 2019.

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. State preemption of local smoke-free laws in government work sites, private work sites, and restaurants—United States, 2005–2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(4):105–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alciati MH, Frosh M, Green SB et al. State laws on youth access to tobacco in the United States: measuring their extensiveness with a new rating system. Tob Control. 1998;7(4):345–352. doi: 10.1136/tc.7.4.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Preventing tobacco use among youth and young adults: a report of the surgeon general. February 2012. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK99237/?report=reader. Accessed September 10, 2018. [PubMed]

- 31.Borland R, Yong HH, Siahpush M et al. Support for and reported compliance with smoke-free restaurants and bars by smokers in four countries: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control. 2006;15(suppl 3):iii34–iii41. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.008748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nixon ML, Mahmoud L, Glantz SA. Tobacco industry litigation to deter local public health ordinances: the industry usually loses in court. Tob Control. 2004;13(1):65–73. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.004176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. State preemption of local tobacco control policies restricting smoking, advertising, and youth access—United States, 2000–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(33):1124–1127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Connor JC, MacNeil A, Chriqui JF et al. Preemption of local smoke-free air ordinances: the implications of judicial opinions for meeting national health objectives. J Law Med Ethics. 2008;36:403–412, 214. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2008.00284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rhoades RR, Beebe LA. Tobacco control and prevention in Oklahoma: best practices in a preemptive state. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(1):S6–S12. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ax the Bev Tax. Philly bev tax hurts! January 2018. Available at: https://www.axthebevtax.com. Accessed September 10, 2018.

- 37.Backholer K, Martin J. Sugar-sweetened beverage tax: the inconvenient truths. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(18):3225–3227. doi: 10.1017/S1368980017003330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crosbie E, Gonzalez M, Glantz SA. Health preemption behind closed doors: trade agreements and fast-track authority. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(9):e7–e13. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crosbie E, Hatefi A, Schmidt L. Emerging threats of global preemption to nutrition labelling. Health Policy Plan. 2019;34(5):401–402. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czz045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crosbie E, Thomson G. Regulatory chills: tobacco industry legal threats and the politics of tobacco standardised packaging in New Zealand. N Z Med J. 2018;131(1473):25–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]