Abstract

Oocyte maturation is essential for proper fertilization, embryo implantation and early development. While the physiological conditions of these processes are relatively well-known, its exact molecular mechanisms remain widely undiscovered. Oocyte growth, differentiation and maturation are therefore the subject of scientific debate. Precious literature has indicated that the oocyte itself serves a regulatory role in the mechanisms underlying these processes. Hence, the present study performed expression microarrays to analyze the complete transcriptome of porcine oocytes during their in vitro maturation (IVM). Pig material was used for experimentation, as it possesses similarities to the reproductive processes and general genetic proximities of Sus scrofa to human. Oocytes, isolated from the ovaries of slaughtered animals were assessed via the Brilliant Cresyl Blue test and directed to IVM. A number of oocytes were left to be analyzed as the ‘before IVM’ group. Oocyte mRNA was isolated and used for microarray analysis, which was subsequently validated via RT-qPCR. The current study particularly focused on genes belonging to ‘positive regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent’, ‘positive regulation of gene expression’, ‘positive regulation of macromolecule metabolic process’ and ‘positive regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter’ ontologies. FOS, VEGFA, ESR1, AR, CCND2, EGR2, ENDRA, GJA1, INHBA, IHH, INSR, APP, WWTR1, SMARCA1, NFAT5, SMAD4, MAP3K1, EGR1, RORA, ECE1, NR5A1, KIT, IKZF2, MEF2C, SH3D19, MITF and PSMB4 were all determined to be significantly altered (fold change, >|2|; P<0.05) among these groups, with their downregulation being observed after IVM. Genes with the most altered expressions were analyzed and considered to be potential markers of maturation associated with transcription regulation and macromolecule metabolism process.

Keywords: pig, oocyte, RNA, transcription, in vitro maturation

Introduction

The porcine reproductive physiology is a clear and valuable model for studying and developing the knowledge in follicle growth and maturation of the oocyte. Moreover, it gives lots of information that might be implemented in human research, taking into account the relevant similarity of reproduction between the species. The past and recent animal research gave rise to the basics of embryology and implemented many techniques in assisted reproduction. The oocyte development and ovulation are one of the most important processes in mammalian reproduction, though it gives the opportunity to fertilize and transfer genes to a new entity. Nevertheless, growth, differentiation and maturation of the oocyte and surrounding structures still remains a subject of inquiring debate. Literature suggests, that oocyte itself, plays an essential role in regulatory mechanisms of its growth and development, influencing and being influenced by surrounding granulosa cells via specific gap junctions. These mechanisms are regulated by expression of particular genes and their biochemical signaling pathways, presence of specific molecules and growth and differentiation factors (1–5). Oocyte maturation consists of numerous rearranges in cell nucleus and cytoplasm, which are essential to finalize its competence to fertilize. Nuclear maturity is strictly conjoined with resume and finish of first meiotic division and entrance into second one, arrested in metaphase II, until contact with spermatozoon. The initiation of final maturation is present in antral-dominant follicles and is based on the mid-cyclic LH surge or administration of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). However, as mentioned, mechanisms of oocyte maturation in vivo are still under investigation, therefore an animal in vitro models provide insight into these complicated and sensitive cross-linked actions, comprising regulation of gene expression, transcription and macromolecule metabolic processes. The adequate gene expression and storage of macromolecules seems to be crucial for protein biosynthesis during pre- and periimplantation stages of embryo development (6).

The mentioned, bi-directional communication between the oocyte and accompanying cumulus cells is necessary for growth, development and function of the whole cumulus-oocyte complex (COC), but it has also been published, that the oocyte is the crucial cell determining the direction of differentiation and the function of the granulosa cells surrounding it (1). It secretes factors, such as growth and differentiation factor 9 (GDF9), bone morphogenetic protein 15 (BMP15) and possibly many others, regulating proliferation, apoptosis, expansion luteinisation and metabolism of GCs (7). However, transcriptomic profiles of exclusively expressed either in granulosa cells or oocytes have been hardly studied. We investigated transcriptome profile of porcine oocytes before and after in vitro culture, assuming, that oocyte itself plays a crucial role in self-development and early embryo evolution. The results obtained are advancing our knowledge about oocyte transcriptome changes during in vitro culture (8–10).

Materials and methods

Part of the materials and methods section is based on our previous publications of the same research team, presenting results from the same cycle of studies related to porcine oocytes (11–13).

Animals

In the present study, pubertal crossbred Landrace gilts (median age of 170, ranging from 150–180 days; median weight of 98 kg, ranging from 95–110 kg) in a total number of 45 were used. The animals were bred under the same conditions, also feeding and housing state of all the animals was identical. The specimen were obtained from a commercial slaughterhouse and the methods of anaesthesia, euthanasia and death verification were compliant to the law of the European Union (European Union Parliament directives 853/2004, 854/2004 and 1099/2009, on the hygiene, quality control, worker qualification and slaughter methods in the meat industry) and Local Laws [Directives of the Polish Ministry of Agriculture and Countryside Development from 24th of September 2009 (Protection of Slaughtered Animals) and 19th of May 2010 (Qualification of Small-scale Slaughterhouse Working Conditions and Hygiene)]. All experiments employed in this study were approved by the Local Bioethical Committee of Poznań University of Medical Sciences (resolution no. 32/2012, issued 01.06.2012).

Collection of porcine ovaries and cumulus-oocyte-complexes (COCs)

After slaughter, the ovaries and reproductive tracts of the animal specimen were recovered and transported to the laboratory within 30 min at 38°C. in 0.9% NaCl, to provide material integrity through transport time. Ovaries of each animal were placed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Sigma-Aldrich Co.; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) to ensure optimal environment for subsequent oocyte in vitro maturation and fertilization. In the next step, single preovulatory large follicles (an estimated diameter greater than 5 mm) were opened (in the number of 300) in a sterile Petri dish by puncturing (a 5-ml syringe and 20-G needle were employed to puncture selected follicles). This operation allows to obtain the cumulus-oocyte complexes (COCs). The COCs extracted from follicles were washed thrice in PBS supplemented with 36 µg/ml pyruvate, 50 µg/ml gentamicin, and 0.5 mg/ml Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA; all ingredients provided by Sigma-Aldrich Co.; Merck KGaA). After collection and washing, an inverted microscope Zeiss, Axiovert 35 (Zeiss, Lübeck, Germany) were used for COCs selection, counting, and morphological evaluation. Subsequently, the scale suggested by Pujol et al (14) and Le Guienne et al (15) and also described in our previous study were used. Only grade I COCs that exhibited homogeneous cytoplasm and uniform, compact cumulus cells were qualified for the following steps of study, which resulted in a total of 300 grade I oocytes. From the total number of 300 grade I oocytes that were determined BCB+. 150 of those were used for analysis as ‘Before IVM’ with the other directed for in vitro maturation (‘After IVM’).

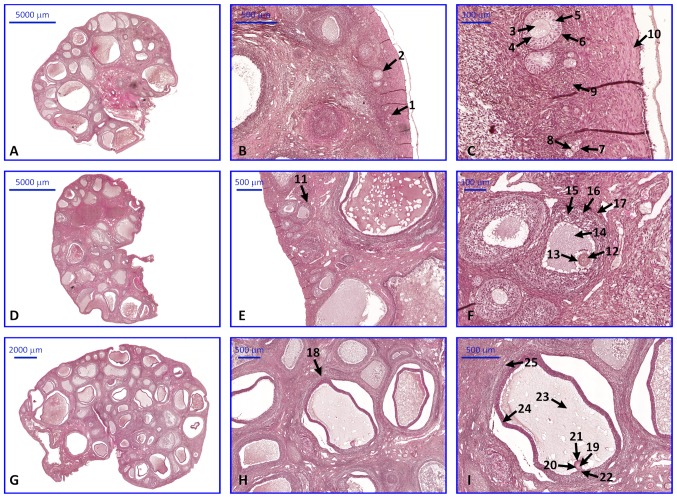

Ovaries from ten animals were collected and fixed in the Bouin's solution for 48 h. Subsequently, tissues were dehydrated and embedded in paraffin wax. Sections of ovaries (3–4 µm) were cut with a semi-automatic rotary microtome (Leica RM 2145, Leica Microsystems, Nussloch, Germany). Then, the paraffin sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) routine procedure, following the steps: Deparaffinization and rehydration, H and staining, and finally, dehydration. Histological sections were evaluated by light microscope and selected pictures were taken with a use of high-resolution scanning technique and Olympus BX61VS microscope scanner (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Assessment of oocyte developmental competence by BCB test

Measurement of the activity of the glucose-6-phosphate (G6PDH) enzyme, which is responsible for conversion of Brilliant Cresyl Blue (BCB) stain from blue to colourless, was employed to assess oocyte developmental competence. In oocytes that completed their growth, activity of the enzyme decreases significantly, which causes the stain to be immobilized, resulting in blue oocytes (marked BCB+). To perform the BCB staining test oocytes were washed twice in modified Dulbecco PBS (DPBSm) (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) additionally supplemented with 50 IU/ml penicillin, 50 µg/ml streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA), 0.4% [w/v] BSA, 0.34 mM pyruvate, and 5.5 mM glucose. After the initial preparation of oocytes, cells were treated with 13 µM BCB (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) diluted in DPBSm at 38.5°C, 5% CO2 for 90 min. In the next step oocyte were twice washed in DPBSm. During the washing procedure, the oocytes were examined under an inverted microscope, which allowed for their classification as stained blue (BCB+) or colourless (BCB−). Immature oocytes, characterized by the presence of a cumulus cells layer, give a negative result in this test, and were used for the downstream analyses as ‘Before IVM’ group. Whereas, the BCB+ COCs to remove cumulus and granulosa cells layer, were incubated with hyaluronidase solution (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 2 min at 38°C. After removing these additional cells in the 1% sodium citrate buffer, oocytes for further cell culture procedures were obtained.

In vitro maturation (IVM) of porcine COCs

The oocytes that gave a positive result after the first BCB test were used during IVM procedure. Oocytes were cultured in 500 µl standard porcine IVM culture medium, TCM-199 (tissue culture medium) with Earle's salts and L-glutamine, (Gibco BRL Life Technologies; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 2.2 mg/ml sodium bicarbonate (Nacalai Tesque, Inc., Kyoto, Japan), 0.1 mg/ml sodium pyruvate (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA), 10 mg/ml Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA), 0.1 mg/ml cysteine (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA), 10% (v/v) filtered porcine follicular fluid and gonadotropin supplements at final concentrations of 2.5 IU/ml hCG (human Chorionic Gonadotropin; Ayerst Laboratories, Inc., Philadelphia, PA, USA) and 2.5 IU/ml eCG (equine Chorionic Gonadotropin; Intervet, Whitby, ON, Canada). Each well in Nunclon™Δ 4-well dishes (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was covered with mineral oil overlay and placed for the first 22 h of maturation in 38°C under 5% CO2. Subsequently, in the same culture conditions for 22 h, a new portion of the maturation medium has been used, however now without hormone supplementation. After maturation, second BCB staining test was performed, with BCB+ oocytes used for downstream analyses. Based on visual analysis under inverted microscope, around 70% from the initial pool of cells were determined as BCB+. This contributed to obtain the final number around 105 out of the initial 150 of oocytes marked as ‘After IVM’.

RNA extraction from porcine oocytes and reverse transcription

Before the extraction, COCs from both of the experimental groups were denuded with the use of hyaluronidase and glass micropipette to eliminate all of the surrounding somatic cells. Total RNA from all of the samples (both before and after IVM) was isolated according to the method published by Chomczyński and Sacchi (16) employing TRI reagent (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA). RNA integrity was determined by denaturing agarose gel (2%) electrophoresis, and then, the RNA was quantified by measuring the optical density (OD) at 260 nm (NanoDrop spectrophotometer; Thermo Scientific, Inc.). The RNA samples were re-suspended in 20–40 µl of RNase-free water and stored at −80°C. RNA samples were treated with DNase I and reverse-transcribed into cDNA using RT2 First Strand kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), according to the manufacturer's protocol. From each RNA sample, 100 ng of RNA was taken for the following molecular analyses (Microarray and RT-qPCR).

Microarray expression analysis and statistics

Experiments were performed in three replicates. cDNA obtained was used for biotin labelling and fragmentation using Affymetrix GeneChip® WT Terminal Labeling and Hybridization (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Biotin-labelled fragments of cDNA (5.5 µg) were hybridized to Affymetrix® Porcine Gene 1.1 ST Array Strip (48°C/20 h). Microarrays were then washed and stained according to the technical protocol using the Affymetrix GeneAtlas Fluidics Station. The array strips were scanned employing Imaging Station of the GeneAtlas System. Preliminary analysis of the scanned chips was performed using Affymetrix GeneAtlas™ Operating Software. The quality of gene expression data was confirmed according to the quality control criteria provided by the software. The obtained CEL files were imported into downstream data analysis software.

To prepare all presented in the manuscript analyses and graphs Bioconductor, based on the statistical R programming language were used. Each CEL file was merged with a description file. In order to correct background, normalize and summarize the raw data, we used Robust Multiarray Averaging (RMA) algorithm.

To determine the statistical significance of the analyzed genes, moderated t-statistics from the empirical Bayes method were performed. The obtained P-value was corrected for multiple comparisons using Benjamini and Hochberg's false discovery rate. The selection of significantly altered genes was based on a P<0.05 and expression higher than two-fold. The differentially expressed gene list (separated for up- and downregulated genes) was uploaded to the DAVID software (Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery). In our work we focused on 27 genes belonging to ‘positive regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent’, ‘positive regulation of gene expression’, ‘positive regulation of macromolecule metabolic process’ and ‘positive regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter’ Gene Ontology Biological Process (GO BP) terms.

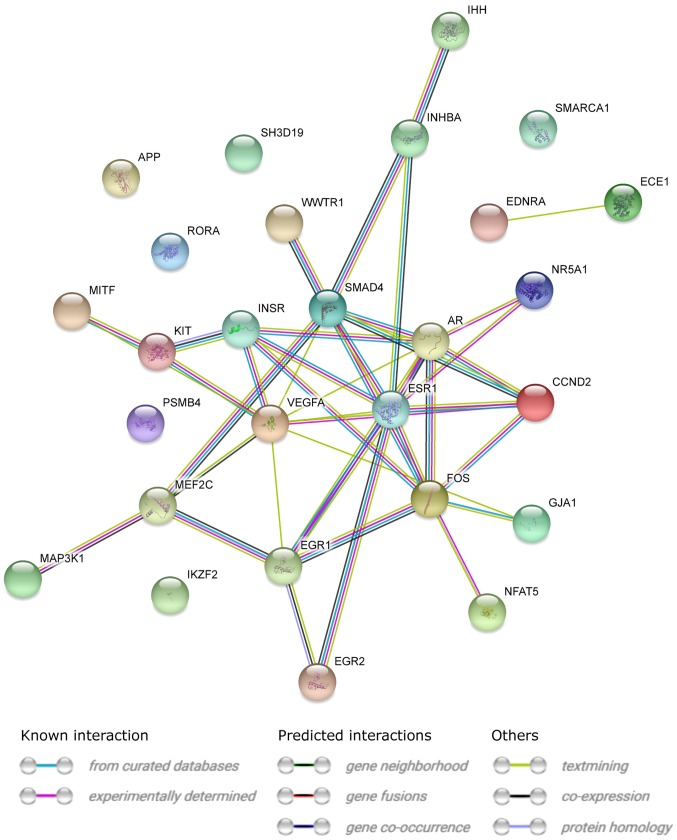

Subsequently, sets of differentially expressed genes from selected GO BP terms were applied to STRING10 software (Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins) for interaction prediction. STRING is a huge database containing information about protein/gene interactions, including experimental data, computational prediction methods and public text collections.

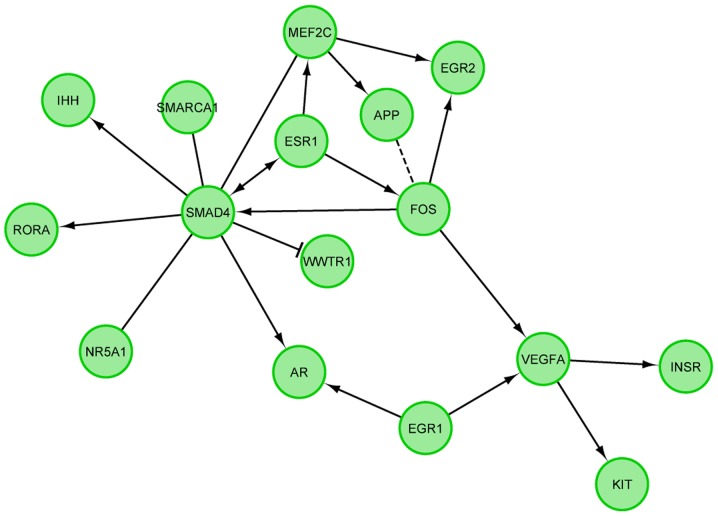

In the next step of microarray data analysis, we employed ReactomeFIViz application to the Cytoscape 3.6.0 software. Through the use of this analytical tool the functional interaction between genes that belongs to the chosen GO BP terms were examined.

The ReactomeFIViz app used for location pathways and network patterns that are connected to cancer and other disease types. It allows to run pathway enrichment analysis for a specified gene group, visualizes found pathways with the use of manually laid-out pathway diagrams, as well as to investigate the functional relations between the genes of those pathways, through accessing the Reactome database.

Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) analysis

The RT-qPCR method was performed to confirm and quantitatively validate the results obtained in the analysis of expression microarrays. LightCycler 96 real-time PCR detection system (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) was used to perform the RT-qPCR reactions. SYBR® Green I detection dye was used during the analyzes, with target cDNA quantified using the relative quantification method. The relative abundance of FOS, VEGFA, ESR1, AR, CCND2, EGR2, ENDRA, GJA1, INHBA transcripts in each sample was standardized to the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA level as an internal control. For efficient amplification, 2 µl of previously received cDNA was mixed with 18 µl of RT2 SYBR® Green ROX™ qPCR Master Mix (Qiagen Sciences, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, USA) and sequence-specific primers (Table I). One RNA repeat from each preparation was processed without the RT-reaction to provide a negative control for subsequent PCR. For relative quantification, we applied the 2-ΔΔCq method. Agarose gel electrophoresis was used to confirm the specificity of the amplified PCR products. To quantify mRNA levels of specific genes in the oocyte, transcript levels were calculated in relation to porphobilinogen deaminase (PBGD) and β-actin (ACTB). To ensure result integrity, an additional housekeeping gene, 18S rRNA, was used as an internal standard.

Table I.

Oligonucleotide sequences of the primers used for reverse transcription-quantitative PCR analysis.

| Gene | Accession number | Primer sequence (5′-3′) | Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| APP | P79307 | F: CATCGCTTACAAACTCGCCA | 160 |

| R: TGCCAAGAAGTCTACCCTGA | |||

| AR | NP_999479 | F: TGGTGCAATCATTTCTGCTG | 153 |

| R: ACTTTCCACCCCAGAAGACC | |||

| CCND2 | Q8WNW2 | F: ACGTCGGTGTTGGTGATCC | 154 |

| R: CCACTGACTTCAAGTTCGCC | |||

| ECE1 | HGNC:3146 | F: GTAATGTTAGCAGCGCCGTT | 110 |

| R: GAGAAGGTGCTGACGGGATA | |||

| EDNRA | NP_999394 | F: AGGTGTTCACTGAGGGCAAT | 168 |

| R: TGCCACGTCAAAATTCATGGA | |||

| EGR1 | HGNC:3238 | F: CCACTAGAACCTTCTCGTTATTCA | 103 |

| R: AGCGCCTTCAACCCTCAG | |||

| EGR2 | NP_001090957 | F: GCTGGCACCAGGGTACTG | 154 |

| R: CGGAGATGGCATGATCAAC | |||

| ESR1 | Q29040 | F: TTCCTGTCCAGGAGCAAGTT | 155 |

| R: AAGAGGGTGCCAGGATTTTT | |||

| FOS | NP_001116585 | F: CAGATCGGTGCAGAAGTCCT | 159 |

| R: ATGATGTTCTCCGGCTTCAA | |||

| GJA1 | NP_001231141 | F: GGGCAGGGATCTCTTTTGC | 150 |

| R: CAAGGTGAAAATGCGAGGGG | |||

| IHH | NP_001231399 | F: CACACGTGCCCCACTCTC | 134 |

| R: GCTTCGACTGGGTGTATTACG | |||

| IKZF2 | HGNC:13177 | F: AGGAGGTACATGGTGACTCA | 174 |

| R: CTCACAGGACACCTCAGGAC | |||

| INHBA | P03970 | F: TCAGGAAGAGCCAGATTTCG | 151 |

| R: AGGGCGGAAATGAATGAACT | |||

| INSR | HGNC:6091 | F: GTCGGTGACTCTCTCTGGAC | 160 |

| R: CACTTCTTCCGACATGTGGT | |||

| KIT | NP_001037990 | F: ACAGCCTAATCTCATCGCCA | 152 |

| R: CGCCTGGGATTTTCTCTTCG | |||

| MAP3K1 | HGNC:6848 | F: CTACATTCTTCTGCCCAGATTG | 150 |

| R: TTCAGAAAACAGTATAAAAGATGAAGA | |||

| MEF2C | NP_001038005 | F: TTTTGCTTGCATATTCTTGTTCA | 168 |

| R: CCTGGTGTAACACATCGACCT | |||

| MITF | NM_001315782 | F: CTGTTCCCGTTGCAACTTTC | 163 |

| R: CAATCACAACTTGATTGAACGAA | |||

| NFAT5 | HGNC:7774 | F: GTTGGCCTGGCTGACTTATG | 157 |

| R: GGAGGTACAATGAACCAGCTACA | |||

| NR5A1 | P79387 | F: GGTCAGCTCCACCTCCTG | 150 |

| R: GTCTTCAAGGAGCTGGAGGT | |||

| PSMB4 | NP_001231384 | F: ACGTAACCCAGGAAGCTCTC | 165 |

| R: GGTGATTGATGAGGAGCTGC | |||

| RORA | HGNC:10258 | F: CATGAGCGATCTGCTGACAT | 152 |

| R: TATGCTAGCCCCGATGTCTT | |||

| SH3D19 | HGNC:30418 | F: GCTCTGTTATTATGTCTCCAGCC | 154 |

| R: ATCTTCCCCGCAGTCTTCG | |||

| SMAD4 | Q9GKQ9 | F: TGTTTTAATTCATTTTTGTGAAGATCA | 150 |

| R: AACCACAAATGGAGCTCACC | |||

| SMARCA1 | HGNC:11097 | F: TTCCTTGGGACCTTATAGCC | 164 |

| R: AGAGAGGCATTACGTGTCAGC | |||

| VEGFA | NP_999249 | F: TCTCGATTGGACGGCAGTAG | 154 |

| R: CTCTCTTGGGTGCATTGGAG | |||

| WWTR1 | HGNC:24042 | F: ATTGATGTTCATGGGTGTGG | 152 |

| R: ATGGGGGACCATATCATTCA | |||

| ACTB | DQ845171 | F: GGGAGATCGTGCGGGACAT | 141 |

| R: CGTTGCCGATGGTGATGAC | |||

| PBGD | NM_001097412 | F: GAGAGTGCCCCTATGATGCTAT | 214 |

| R: GATGGCACTGAACTCCT | |||

| 18S rRNA | AB117609 | F: GTGAAACTGCGAATGGCTC | 105 |

| R: CCGTCGGCATGTATTAGCT |

F, forward; R, reverse.

Results

We observed upregulation of all genes involved in ‘positive regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent’, ‘positive regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter’, ‘positive regulation of gene expression’, ‘positive regulation of macromolecule metabolic process’ before IVM as compared to transcriptional profile analyzed after IVM.

Microarray

Whole transcriptome profiling by Affymetrix microarray allowed us to analyze the oocyte gene expression changes after in vitro maturation in relation to freshly isolated oocyte, before in vitro procedure (in vivo). By Affymetrix® Porcine Gene 1.1 ST Array we examined expression of 12258 porcine transcripts. Genes with fold change higher than abs (2) and with corrected P-value lower than 0.05 were considered as differentially expressed. This set of genes consisted of 419 different transcripts.

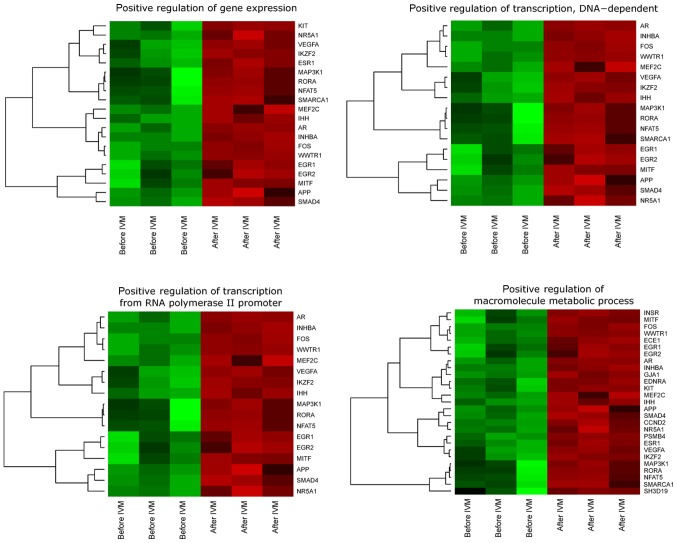

DAVID (Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery) software was used for extraction of enriched GO BP terms. Up and downregulated gene sets were subjected to DAVID searching separately and only gene sets where adj. P-value were lower than 0.05 were selected, as previously described (17). We find that 28 genes that belong to ‘positive regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent’, ‘positive regulation of gene expression’, ‘positive regulation of macromolecule metabolic process’ and ‘positive regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter’ GO BP terms were significantly represented in downregulated gene set. This set of genes was subjected to hierarchical clusterization procedure and presented as heatmaps (Fig. 1). Fold changes in expression, Entrez gene IDs and adjusted P. values of genes belonging to selected GO BP were shown (Table II).

Figure 1.

Heat map representation of differentially expressed genes belonging to the selected ‘positive regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent’, ‘positive regulation of gene expression’, ‘positive regulation of macromolecule metabolic process’ and ‘positive regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter’ Gene Ontology biological process terms. Arbitrary signal intensity acquired from microarray analysis is represented by different colors (green indicates a higher expression; red indicates a lower expression). Log2 signal intensity values for any single gene were resized to Row Z-Score scale (from −2, the lowest expression to +2, the highest expression for single gene). IVM, in vitro maturation.

Table II.

Gene symbols, fold changes on expression, Entrez gene IDs and adjusted P-values of the genes studied.

| Gene | Fold-change | Adjusted P-value | Entrez Gene ID |

|---|---|---|---|

| APP | 0.324139 | 0.005602 | 351 |

| AR | 0.105986 | 0.000138 | 367 |

| CCND2 | 0.121809 | 0.000179 | 894 |

| ECE1 | 0.395388 | 0.001178 | 1889 |

| EDNRA | 0.166939 | 0.001854 | 1909 |

| EGR1 | 0.376128 | 0.005477 | 1958 |

| EGR2 | 0.165504 | 0.00795 | 1959 |

| ESR1 | 0.08163 | 0.000522 | 2099 |

| FOS | 0.052794 | 4.74E-05 | 2353 |

| GJA1 | 0.206907 | 0.000108 | 2697 |

| IHH | 0.304996 | 0.000551 | 3549 |

| IKZF2 | 0.431872 | 0.002983 | 22807 |

| INHBA | 0.24126 | 0.000148 | 3624 |

| INSR | 0.316016 | 0.001913 | 3643 |

| KIT | 0.430444 | 0.002556 | 3815 |

| MAP3K1 | 0.368765 | 0.024748 | 4214 |

| MEF2C | 0.453593 | 0.003964 | 4208 |

| MITF | 0.49166 | 0.00633 | 4286 |

| NFAT5 | 0.344889 | 0.013145 | 10725 |

| NR5A1 | 0.425153 | 0.001889 | 2516 |

| PSMB4 | 0.493702 | 0.000939 | 5692 |

| RORA | 0.383924 | 0.021554 | 6095 |

| SH3D19 | 0.488128 | 0.046513 | 152503 |

| SMAD4 | 0.367802 | 0.001239 | 4089 |

| SMARCA1 | 0.329141 | 0.014759 | 6594 |

| VEGFA | 0.069689 | 0.001913 | 7422 |

| WWTR1 | 0.327202 | 0.000254 | 25937 |

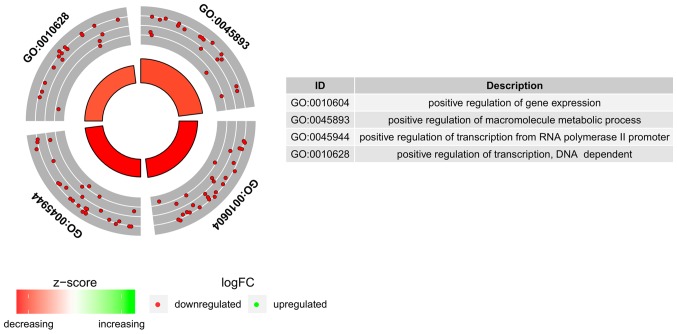

To further investigate the changes within chosen GO BP terms we measured the enrichment levels of each selected GO BP terms. The enrichment levels were expressed as z-score and presented as circular visualization (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Circular visualization of gene-annotation enrichment analysis. The outer circle presents a scatter plot for each log FC term of the assigned genes. Red circles indicate upregulation and blue circles indicate downregulation. The inner circle represents the Z-score and the size/colour of the bar corresponds to its value.

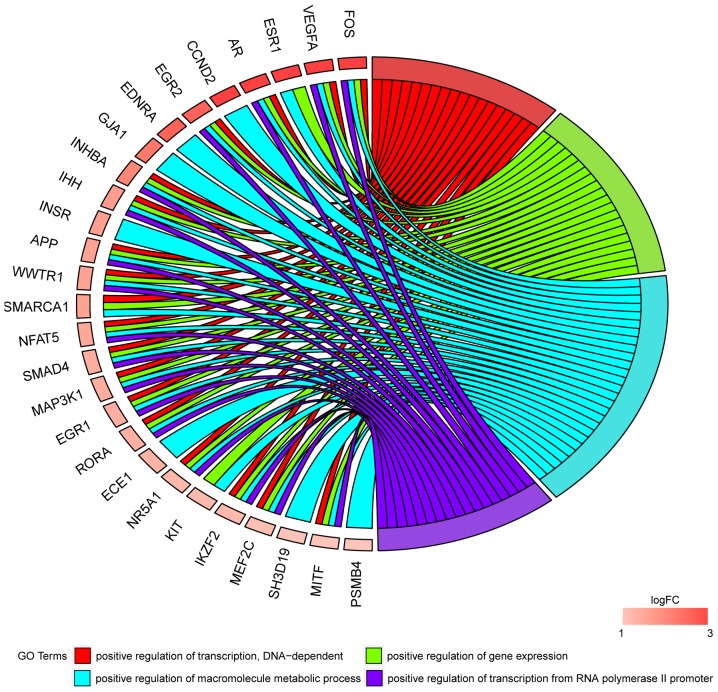

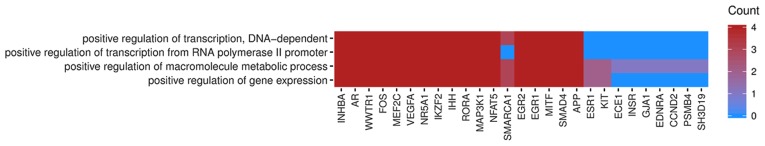

In Gene Ontology database genes that formed one particular GO group can also belong to other different GO term categories. For this reason, we have explored the gene intersections between selected GO BP terms. The relation between those GO BP terms was presented as circle plot (Fig. 3) as well as heatmap (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Representation of the mutual association between genes that belongs to ‘positive regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent’, ‘positive regulation of gene expression’, ‘positive regulation of macromolecule metabolic process’ and ‘positive regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter’ Gene Ontology biological process terms. The ribbons indicate which gene belongs to which category. The genes were sorted via logFC from the most to least altered genes.

Figure 4.

Heatmap presenting occurrence between genes that belong to ‘positive regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent’, ‘positive regulation of gene expression’, ‘positive regulation of macromolecule metabolic process’ and ‘positive regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter’ GO BP terms. Red coloring indicates the gene occurrence in the indicated GO BP Term. Colour intensity is correlated with the number of GO BP terms that selected genes belonged to. GO, gene ontology; BP, biological process.

STRING interaction network was generated among chosen differentially expressed genes belonging to each of the selected GO BP terms. Using such prediction method provided us with a molecular interaction network formed between protein products of studied genes (Fig. 5). Finally, we investigated the functional interactions between chosen genes with REACTOME FIViz app to Cytoscape 3.6.0 software. The results were shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 5.

STRING-generated interaction network among differentially expressed genes belonging to the ‘positive regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent’, ‘positive regulation of gene expression’, ‘positive regulation of macromolecule metabolic process’ and ‘positive regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter’ Gene Ontology biological process terms. The intensity of the edges indicates the strength of interaction score.

Figure 6.

FIs between genes that belong to ‘positive regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent’, ‘positive regulation of gene expression’, ‘positive regulation of macromolecule metabolic process’ and ‘positive regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter’ Gene Ontology biological process terms. > indicates ‘for activating/catalyzing’, -| for ‘inhibition’, - for FIs extracted from complexes or inputs and --- for predicted FIs. FI, functional interaction.

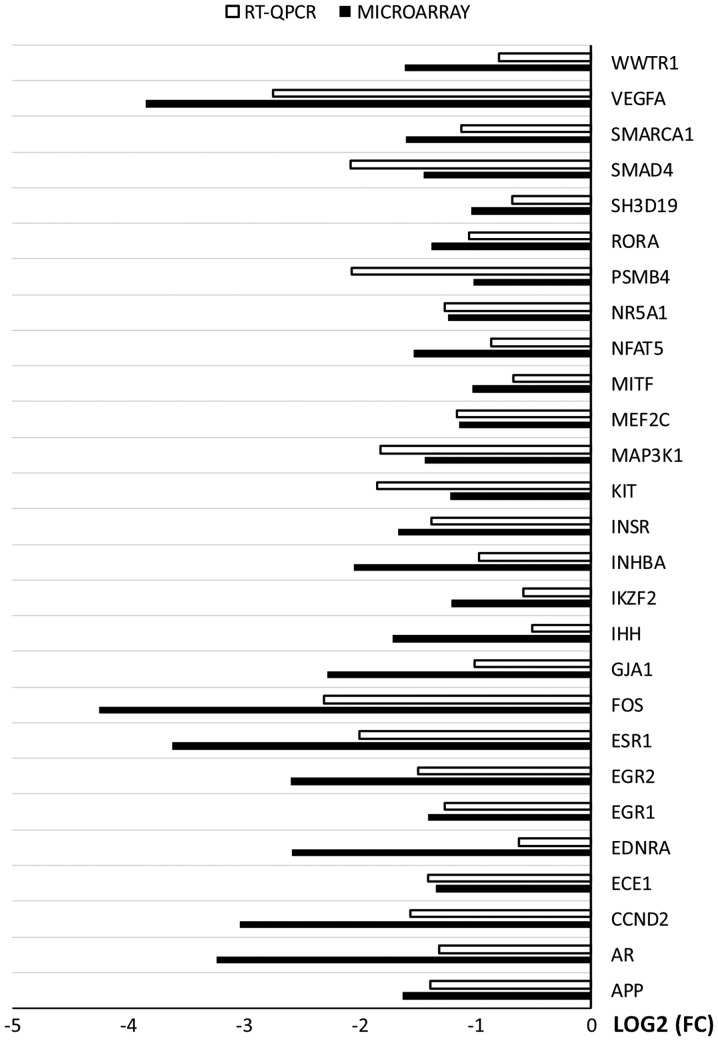

RT-qPCR was used to validate the results of microarray analysis. The results were presented in a form of a bar graph (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Comparison of RT-qPCR and microarray results. RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative PCR.

Overall, the direction of changes was confirmed in every example. However, the scale of changes in levels of gene expression varied between the methods. In examples such as: APP, NR5A1, MEF2C, INSR, EGR1 and ECE1 the difference was rudimental. However, in some genes (WWTR1, VEGFA, PSMB4, INGBA, IHH, FOS, ESR1, EGR2, ENDRA, CCND2, AR) the variation between the methods was major. The rest of the genes presented moderate variation between the microarray and RT-qPCR results.

Light microscope observation of H&E stained sections revealed the normal histological structure of ovaries (Fig. 8). The follicles in different stages of development were present in each of analyzed sections.

Figure 8.

Photomicrograph representing the sections of ovaries stained with hemotoxylin and eoesin. All images present follicles in various stages of development. The description of each arrow and number is represented in brackets. (A) Primordial and primary follicles. Tissue sections exhibiting: (B) Primordial follicles and primary follicles, and (C) primary oocytes, zona pellucida, granulosa cells, theca cells, follicular cells, cortical stroma and tunica albuginea. (D) Secondary follicle. Tissue sections exhibiting: (E) secondary follicles, and (F) primary oocytes, zona pellucida, antrum, granulosa cells, theca cells and theca externa. (G) Graafian follicle. Tissue sections exhibiting: (H) Graafian follicles, and (I) secondary oocytes, zona pellucida, corona radiata, cumulus oophorus, antrum, granulosa cells and theca externa. 1, primordial follicle; 2, primary follicle; 3, 7 and 12, primary oocyte; 4, 13 and 20, zona pellucida; 5, 15 and 24, granulosa cells; 6 and 16, theca cells; 8, follicular cells; 9, corticol stroma; 10, tunica albuginea; 11, secondary follicle; 14 and 23, antrum; 17 and 25, theca externa; 18, Graafian follicle; 19, secondary oocyte; 21, corona radiata; 22, cumulus oophorus.

Discussion

Heat maps show the expression of genes which belong to the category of ‘positive regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent’, ‘positive regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter’, ‘positive regulation of gene expression’ and ‘positive regulation of macromolecule metabolic process’ from GO. BP database. We have found abundant differences in the expression of genes: FOS, VEGFA, ESR1, AR, CCND2, EGR2, ENDRA, GJA1, INHBA. These genes were upregulated in porcine oocytes before IVM as compared with post-IVM expression analysis.

In the complexity of genes up- and downregulated in mammalian cumulus-oocyte-complex cross-talk, we have tried to distinguish these, which are differentially expressed in the in vitro oocyte culture in comparison to development in vivo. Investigation of transcriptomic profiles of oocyte and CCs separately is a very demanding challenge, requiring deep knowledge of factors acting bi-directionally and expressed exceptionally in particular cell type. Regassa et al (7) analyzed transcriptome profile from oocyte and CCs samples in bovine ovaries. They detected multiple genes in germinal vesicle and in metaphase II oocytes, reflecting their different expression patterns, in accordance to presence, or absence of accompanying cumulus cells. This study revealed, that a total of 265 transcripts expressed differentially between oocytes cultured with and without CCs, of which 217 and 48 were over expressed in the former and the later groups, respectively. Authors concluded, that the presence or absence of cumulus cells' factors during bovine oocyte maturation can have a significant influence on transcript abundance, showing the dominant importance of molecular cross-talk between oocytes and their corresponding CCs. This leads us to the conclusion, that ‘bare’ oocyte, even matured in vitro in cumulus-like conditions, can express differently than one encapsulated in cumulus complex. Moreover, it might express some GCs specific factors in conditions of granulosa crosstalk deficiency. Therefore, it is a very challenging request and limit of our study, to differentiate cell-specific transcriptome and to conclude, that particular gene is expressed in oocyte exceptionally, especially in in vitro culture of isolated oocyte.

Moreover, considering the above, in the present study we performed a microarray approach-analyzed porcine oocyte transcriptome and found abundant expression of multiple genes, including FOS, VEGFA, ESR1, AR, CCND2, EGR2, ENDRA, GJA1, INHBA, IHH, INSR, APP, WWTR1, SMARCA1, NFAT5, SMAD4, MAP3K1, EGR1, RORA, ECE1, NR5A1, KIT, IKZF2, MEF2C, SH3D19, MITF and PSMB4.

These genes were downregulated after in vitro oocyte maturation, what might indicate decreased potential of the cell to develop in an environment different than physiological. We will discuss only the most abundant differences in expression of oocyte genes before and after IVM procedure.

The strongest inhibitory effect after in vitro maturation of oocytes referred to transcription factor FBJ-murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog (FOS). It refers to all ontology groups analyzed in recent study. Defined also, as Fos Proto-Oncogene or AP-1 Transcription Factor Subunit, it belongs to the Fos family, comprising of c-Fos, FosB and its smaller splice variants, Fra-1 and Fra-2. It is the part of the SMAD3/SMAD4/JUN/FOS complex and it forms AP1 promoter site due to response to TGF-β (18). It binds to the regulatory regions of numerous genes (19,20). Specific functions of Jun-Fos proteins depend on posttranslational modifications, selective dimerization between family members, and protein-protein interactions with other regulatory molecules (21). It plays a critical role in regulating the development of cells destined to form and maintain the skeleton. It was proved by Johnson et al (22), that the c-fos proto-oncogene has been admitted as a central regulatory component of the nuclear response to mitogens and other extracellular stimuli in mice. The homozygous mutants showed diminished placental and fetal weights and significant loss of viability at birth. There were multiple defects observed, like foreshortening of the long bones, ossification of the marrow space, and absence of tooth eruption, delayed or absent gametogenesis, lymphopenia, and altered behavior. The above indicated that c-Fos was involved in the development and function of several distinct tissues. Moreover, in humans, c-Fos gene transcripts were localized significantly more abundant in fetal amniotic and chorionic cells, what suggested that these gene may be related to embryo-derived cells, whose primary functions are protection and nourishment of the fetus (23). The analysis of porcine ovaries, obtained by Rusovici et al (21), suggests that although most AP-1 factors are present throughout the follicular cycle, specific Jun/Fos proteins are more characteristic for a particular stage of development than for another. The authors found c-Fos, FosB and Fra-1, Fra-2 in all follicular cell compartments, also in oocyte nucleus, in which being present throughout whole follicle development, but the last staining could be nonspecific due to technical limitations. Nevertheless, a study conducted by Hattori et al (24), showed the presence of c-Fos mRNA in porcine oocytes as well. There is limited data concerning AP1/FOS in folliculogenesis and in ovulation, though it may be involved in many cellular processes, e.g. regulation of steroidogenesis or granulosa cell proliferation. It has been found to be induced by FSH in pig oocyte culture after 1 h, what was consistent with rat studies, but progressively fell over the whole culture period (25).

The second most significant expression decline was observed in VEGFA. This gene is downregulated in all of the ontology groups in our study, after IVM procedure. VEGF gene codes a heparin-binding growth factor specific for vascular endothelial cells and it induces angiogenesis in vivo (26). It has been purified from bovine pituitary follicular cells in 1989 and proved to be mitogenic factor for capillary endothelial cells (27). The gene itself, is a member of platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)/vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) family. This potent factor occurs in five isoforms that rise from alternative splicing of the same gene, and the above have various metabolic effects (28).

The known, basic functions of vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) are: The regulation of cell growth and differentiation; the stimulation of angiogenesis and neovascularization in tissues and organs, inhibition of apoptosis, promotion of cell migration and vascular permeability (29). It is essential for both physiological and pathological vessel formation. This gene is upregulated in many known tumors and its expression is correlated with tumor stage and progression. VEGFA has also been widely studied because of its important role in follicle development. It has been proven, that the growth of antral follicles is associated with increased density of blood vessels within the theca cell layers (30). Moreover, the injection of VEGF gene directly into gilts' ovaries, increased the levels of mRNA expression of VEGF 120 and VEGF 164 isoforms in the granulosa cells and VEGF protein level in the follicular fluid. This resulted in the increase in number of preovulatory follicles, indicating, that angiogenesis is an important factor in the development of ovulatory follicles (30). However, since the expression of VEGFA has also been localized in nonvascular follicles and cells, influence on follicular development through nonangiogenic mechanisms is debated (31). It is unknown, if oocyte originated VEGFA has an influence on surrounding cells, but Bui et al (32) published data confirming, that VEGF supplementation improves the meiotic and developmental competence and fertilization ability of oocytes derived from 0.3–5 mm porcine follicles, at adequate concentrations during IVM. This might indicate, that VEGF has to be secreted locally (by GCs or oocyte), before vascularization process occurs, to increase growth and developmental competence of the oocyte. In addition, its levels do not increase, until antrum formation. Consistent with previous studies (33,34), in the culture of monkey follicles, Xu et al (35) revealed that VEGF is increased markedly in activated, growing follicles (theca and GCs close to the oocyte), but not in primordial and preantral ones. The hypothesis concludes, that VEGF-dependent antrum formation is a result of hypoxic state of the growing follicle, and increasing need for oxygen and substrates for developing oocyte (36).

Besides FOS and VEGFA, there was significant reduction in expression of AR, EGR2 and INHBA in all four ontology groups observed.

It has been distinctly proven, that androgen receptor (AR) is one of the essential players in reproductive system in mammals (37). AR is expressed in various reproductive tissues, including, various ovarian cells and neuroendocrine ovarian-pituitary-hypothalamus axis. Reproductive phenotypes examined in androgen receptor knock out mice (ARKO) showed disturbances explainable by granulosa cells AR expression, including premature ovarian failure (POF), subfertility with longer estrous cycles, fewer ovulated oocytes, more preantral and atretic follicles, fewer antral follicles and fewer corpora lutea. In addition, in vitro growth of follicles was slower than in control wild-type animals (38). Lenie and Smitz analyzed mouse in vitro folliculogenesis model and proved the importance of AR to normal follicle maturation. Treatment with anti-androgenic compounds reduced follicle growth during the preantral phase and oocyte meiotic maturation in response to human hCG was arrested (39). Therefore, interestingly, oocytes also appear to benefit from androgens. Li et al (40) revealed that testosterone positively contributes to porcine oocyte meiotic resumption in culture system containing a low dose of hypoxanthine. AR apparently significantly contributes to testosterone-induced mitogen-activated protein kinase activation and germinal vesicle breakdown (38,40). In human model AR has been widely investigated in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) patients, in whom there are high androgen levels observed and diminished oocyte developmental competence. Despite the fact, that PCOS is a heterogenous condition, that has different diagnostic criteria worldwide, the AR gene is the X-linked candidate for follicle arrest and maturation disorders. Van Nieuwerburgh et al (41) suggested that the gene's CAG repeat polymorphism is associated with a PCOS phenotype. They reported, shorter CAG repeats in the AR gene, that appear to enhance androgenicity in PCOS.

The next significantly downregulated expression concerns an EGR2 gene-protein also termed Krox20. The early growth response (EGR) family of zinc finger transcription-regulatory factors influences critical genetic programs in cellular growth, differentiation, and function (42,43). There are four EGR members, EGR1, EGR2, EGR3, and EGR4 and each of them have specific biological functions, for example inflammation, immune tolerance and glucose homeostasis (44). It was extensively examined in the context of autoimmunity, being a potent negative regulator of adaptive immune responses (45). The gene products are induced in response to multiple extracellular signals, such as growth factors, hypoxia, cytokines and mechanical forces associated with injury and cellular stress (46). EGR2 gene is highly expressed in a population of migrating neural crest cells in mice and is critical for peripheral nerve myelination in Schwann cells (47). It also has a specific function in the regulation of hindbrain segmentation, stabilization of long-term potentiation, neural plasticity, learning and memory (48), and EGR2-null mice died early, in the embryonic stage, due to defective myelination (45,49). The interesting research by Fang et al (46), showed, that it also may take part in tissue remodeling and wound healing processes, due to upregulation of multiple genes associated with these above. They revealed EGR2, as a functionally distinct transcription factor that was both necessary and sufficient for TGF-β-induced profibrotic responses. These findings suggested that EGR2 plays a role in the pathogenesis of fibrosis. Moreover EGR2 has been suggested to participate in multiple extracellular signals, including adipogenesis and carcinogenesis (50) and it was shown to control adipocyte differentiation, which potentially links to insulin resistance (51). In ovary, EGR2 was investigated, as an intra-ovarian factor, part of a novel signaling axis comprising of gonadotropins-EGR2-IER3, regulating the survival of granulosa cells during folliculogenesis in rats and humans (52). It was also found in the article above, to regulate the expression of myeloid cell leukemia 1 (MCL-1), which belongs to the BCL-2 family of proteins regulating cell survival. It is rather EGR3, that localizes to chromosomes during meiotic progression and it seems to be dispensable during oocyte maturation in mice (43).

INHBA is the protein also known as inhibin beta A or follicle-stimulating hormone-releasing protein (FRP), and is encoded by the INHBA gene (53). The resultant preprotein is a member of the transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) superfamily and is proteolytically modified to build a subunit of the dimeric activin and inhibin protein complexes. Inhibin β A (INHBA) forms a disulfide-linked homodimer known as activin A, which is also a well-known factor in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis (54). Activin A is also proved to play role during embryogenesis and in specific differentiation processes, such as hematopoiesis and osteogenesis (55). INHBA gene is overexpressed in various types of neoplasms, including colorectal, pancreatic, skin and lung cancer (56), but also presents cytostatic and proapoptotic signaling in human melanoma cells (57). According to Locci et al (58), it is proven, that activin A programs the differentiation of human follicular helper T cells, which play a role in protective antibody responses and autoimmune diseases, using SMAD2 and SMAD3 signaling pathways. High expression of INHBA has also been correlated with developmental competence of oocytes and proposed, among others, as predictor of embryo quality in women and in animal models (7,59,60). Little is known about specific roles of inhibins (activin A as well) in early stages of folliculogenesis, but mouse and human models present it, as an important factor for cell proliferation (germ and somatic) and follicular assembly as well (61). Myers et al (62) showed, that the absence of inhibin (but in this paper-particularly inhibin A) induced more granulosa cell-derived activin signaling and oocyte-derived GDF9, reducing Kitl expression in granulosa cells, which in turn influence oocyte growth and contributes to the small oocyte phenotype.

ENDRA and GJA1 expression was markedly reduced in our post-IVM expression analysis. They belong to only one ontology group-the positive regulation of macromolecule metabolic process.

ENDRA is a endothelin-1 receptor type A, also indexed as ETA, is a peptide that plays a role in potent and long-lasting vasoconstriction. There are two receptors, ETA and ETB (the endothelin-1 receptor type B), which are members of the family A G-protein-coupled receptors (63). ENDRA signaling is known to be involved in cardiovascular and craniofacial development, and mice deficient in Endothelin1/Ednra signaling present malformation of an aortic arch and outflow anomalies, which are attributed to cardiac neural crest mesenchymal cell defects (64). Kawamura et al (65) demonstrated, that in periovulatory mice ovaries, there is an increase in the expression of endothelin-1 and one of its receptors endothelin receptor type A (EDNRA). They also presented the ability of endothelin-1 to promote GVBD of preovulatory oocytes by using in vitro and in vivo models, analyzing communication between cumulus cells and oocytes. In addition, the experimental study by Cui et al (66) on supplementation of endothelin-1 to culture medium with human oocytes, presented significant promotion of oocyte maturation via connexin 26 (Cx26) gene expression.

GJA1-Gap junction alpha-1 protein, also known as connexin 43 (Cx43)-is a component of gap junctions, which allow cell to cell communications, providing a route for the diffusion of low molecular weight materials from cell to cell, regulating proliferation, differentiation and cell death (67). It is detected in most cell types, and a major protein responsible for synchronized heart contraction (68). It is also expressed in in cumulus cells, participating in connexons with other cumulus granulosa cells or the oocyte. It regulates oocyte meiosis resumption, and lower levels of GJA1 in cumulus cells are beneficial for oocyte maturation (69). Li et al (70) evaluated cumulus GJA1 gene expression levels according to maturation of the oocyte, fertilization and embryo development. They found GJA1 to be a promising oocyte maturation predictor, but not a fertilization and embryo morphology marker, as indicated in previous studies (71,72).

ESR1 gene, coding estrogen receptor alpha is highly conserved among the vertebrates, and is nuclear, ligand-activated transcription factor composed of several domains important for hormone binding, DNA binding, and activation of transcription (73). The 5′ region of the gene contains multiple promoters responsible for tissue-specific gene expression. ERs form homo- and heterodimers and, when activated, can bind to specific estrogen response elements (EREs) in genes, to mediate transcription of various developmental and homeostatic pathways (74). During sex differentiation in human, when ESR1 is bound by its main ligand, estradiol, the whole complex converts to a form binding to nuclear components, starting the activation or repression of numerous genes involved in development, organization and other functions. It is fundamental in maintaining female phenotype of the endocrine somatic cells of the ovary and development of interstitial compartment cells, keeping the integrity of female sex differentiation (75). ESR1 female knockout homozygous mice appear to develop testis-like features with Leydig cell-like changes to interstitial cells with symptoms of sex reversal in the aspect of morphology and function (76). In the human ovary immunoreactivity for ESR1 was found in thecal, interstitial, and germinal epithelium cells, moreover it is also noticeable in adrenal cortices, kidneys mammary gland, bone, heart, hypothalamus, pituitary gland, liver, lung, spleen, adipose tissue and significantly in epithelial, stromal, and muscle uterine cells (77). ESR1 plays an important role in a variety of tissues and structures, like reproductive, central nervous, skeletal, and cardiovascular systems (78,79). In addition, there are two splice variants resulted from alternative splicing of an ESR1, presenting different tissue-specific manners. ESR1 splice variants were detected in nuclei of granulosa cells of growing follicles at all stages from primary to mature follicles, interstitial gland, theca cells and germinal epithelium cells (80). It is widely known, that ESR1 is extensively disputed in relation to breast cancer therapy and valuable use of selective estrogen receptor modulators (81). Artini et al (82), interestingly analyzed human and mouse cumulus cells samples and concluded, that the downregulation of ESR1 could be related to oocyte competence and is likely to be the driver of expression changes highlighted in the PI3K/AKT pathway.

Cyclin D2 (CCND2) is also downregulated after IVM procedure in porcine oocytes. In general, D-type cyclins are considered as ultimate recipients of mitogenic and oncogenic signals and present specific over-expression in some malignancies in humans. They promote G1/S transition during cell cycle progression, and the action is based on binding to cyclin-dependent kinases, increasing retinoblastoma protein phosphorylation and relieving inhibition of the transcription factor E2F (83). CCND2 is expressed mainly in granulosa cells in response to FSH in the ovary, and cyclin D2 deficient mice present sterility due to lack of proliferative action of GCs and resulting in follicle arrest (84). Han et al (85) reveled, that in rat ovaries, FSH rapidly increased CCND2 expression through both the cAMP/PKA and PI3K/PDK1/Akt signaling pathways, but also enhanced cAMP-mediated CCND2 degradation through a ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Moreover, the inquiring study on infant mice ovaries published by François et al (86), showed, that cyclin D2 expression is influenced by FSH, but in particular concentrations. Low concentrations were inducing CCND2, resulting in GCs proliferations, while high levels of FSH were unable to stimulate cyclin D2-dependent follicular growth, but supporting steroidogenesis. In the study above, it was suggested, that since the paracrine oocyte action plays a significant role in development of ovarian follicles, it would be of interest to determine the possible contribution of the oocyte in the function of the infantile ovary. Cyclin D2 could be one of the factors explaining this process.

Overall, the study has provided us with a plethora of genes that could potentially become new markers of oocyte in vitro maturation associated with regulation of transcription and macromolecule metabolism. However, it needs to be noted that it is an entry level transcriptomic study, which will need further validation on protein level, followed by further in vivo studies to gain clinical significance. Despite that, this research might serve as a point of reference for future studies and possible clinical approaches.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by grants obtained from the Polish National Centre of Science (grant no. UMO-2016/21/B/NZ9/03535).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

MBra designed and performed the experiments, selected the models and wrote the manuscript. KO designed the experiments and provided editorial assistance. WK revised the medical methodology and performed the experiments. MJN wrote the manuscript, performed the experiments and analyzed the data. PSK performed histological experiments and analyzed the data. MJa analyzed the data and corrected the language. AK performed histological experiements. IK revised the medical methodology and performed the experiments. PC analyzed the data, prepared the figures and wrote the manuscript. MJe revised the medical methodology and analyzed the models. PA revised the medical methodology and analyzed the models. DB revised the medical methodology, provided editorial supervision and interpreted the data. MTS provided editorial supervision and interpreted the data. MBru supervised the study, interpreted the data and approved the manuscript. HPK supervised the project and interpreted the data. MN designed and supervised the project, and drafted/revised the manuscript. LP revised the medical methodology, provided editorial supervision and interpreted the data. MZ designed the study, revised the methodology and wrote the manuscript. BK designed and supervised the project, revised the methodology, provided editorial supervision and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Experiments were approved by the Local Ethics Committee in Poznan (resolution no. 32/2012).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Eppig JJ. Oocyte control of ovarian follicular development and function in mammals. Reproduction. 2001;122:829–838. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1220829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilchrist RB, Ritter LJ, Armstrong DT. Oocyte-somatic cell interactions during follicle development in mammals. Anim Reprod Sci. 2004;82-83:431–446. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2004.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matzuk MM, Burns KH, Viveiros MM, Eppig JJ. Intercellular communication in the mammalian ovary: Oocytes carry the conversation. Science. 2002;296:2178–2180. doi: 10.1126/science.1071965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rybska M, Knap S, Jankowski M, Jeseta M, Bukowska D, Antosik P, Nowicki M, Zabel M, Kempisty B, Jaśkowski JM. Cytoplasmic and nuclear maturation of oocytes in mammals-living in the shadow of cells developmental capability. Med J Cell Biol. 2018;6:13–17. doi: 10.2478/acb-2018-0003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rybska M, Knap S, Stefańska K, Jankowski M, Gliszczyńska AC, Popis M, Jeseta M, Bukowska D, Antosik P, Kempisty B, Jaśkowski JM. Transforming growth factor (TGF)-is it a key protein in mammalian reproductive biology? Med J Cell Biol. 2018;6:125–130. doi: 10.2478/acb-2018-0020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rybska M, Knap S, Jankowski M, Jeseta M, Bukowska D, Antosik P, Nowicki M, Zabel M, Kempisty B, Jaśkowski JM. Characteristic of factors influencing the proper course of folliculogenesis in mammals. Med J Cell Biol. 2018;6:33–38. doi: 10.2478/acb-2018-0006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Regassa A, Rings F, Hoelker M, Cinar U, Tholen E, Looft C, Schellander K, Tesfaye D. Transcriptome dynamics and molecular cross-talk between bovine oocyte and its companion cumulus cells. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borys-Wójcik S, Kocherova I, Celichowski P, Popis M, Jeseta M, Bukowska D, Antosik P, Nowicki M, Kempisty B. Protein oligomerization is the biochemical process highly up-regulated in porcine oocytes before in vitro maturation (IVM) Med J Cell Biol. 2018;6:155–162. doi: 10.2478/acb-2018-0025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Budna J, Celichowski P, Bryja A, Jeseta M, Jankowski M, Bukowska D, Antosik P, Nowicki A, Brüssow KP, Bruska M, et al. Expression changes in fatty acid metabolic processrelated genes in porcine oocytes during in vitro maturation. Med J Cell Biol. 2018;6:48–54. doi: 10.2478/acb-2018-0009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kranc W, Brązert M, Ożegowska K, Budna-Tukan J, Celichowski P, Jankowski M, Bryja A, Nawrocki MJ, Popis M, Jeseta M, et al. Response to abiotic and organic substances stimulation belongs to ontologic groups significantly up-regulated in porcine immature oocytes. Med J Cell Biol. 2018;6:91–100. doi: 10.2478/acb-2018-0015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chermuła B, Brązert M, Jeseta M, Ożegowska K, Sujka-Kordowska P, Konwerska A, Bryja A, Kranc W, Jankowski M, Nawrocki MJ, et al. The unique mechanisms of cellular proliferation, migration and apoptosis are regulated through oocyte maturational development-A complete transcriptomic and histochemical study. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;20:E84. doi: 10.3390/ijms20010084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ożegowska K, Dyszkiewicz-Konwińska M, Celichowski P, Nawrocki MJ, Bryja A, Jankowski M, Kranc W, Brązert M, Knap S, Jeseta M, et al. Expression pattern of new genes regulating female sex differentiation and in vitro maturational status of oocytes in pigs. Theriogenology. 2018;121:122–133. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2018.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borys S, Brązert M, Jankowski M, Kocherova I, Ożegowska K, Celichowski P, Nawrocki MJ, Kranc W, Bryja A, Kulus M, et al. Enzyme linked receptor protein signaling pathway is one of the ontology groups that are highly up-regulated in porcine oocytes before in vitro maturation. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2018;32:1089–1103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pujol M, López-Béjar M, Paramio MT. Developmental competence of heifer oocytes selected using the brilliant cresyl blue (BCB) test. Theriogenology. 2004;61:735–744. doi: 10.1016/S0093-691X(03)00250-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Le Guienne B. Small atlas of bovine oocyte. Elevage et Insemination (France) 1998:24–30. [In French] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nawrocki MJ, Celichowski P, Jankowski M, Kranc W, Bryja A, Borys-Wójcik S, Jeseta M, Antosik P, Bukowska D, Bruska M, et al. Ontology groups representing angiogenesis and blood vessels development are highly up-regulated during porcine oviductal epithelial cells long-term real-time proliferation-a primary cell culture approach. Med J Cell Biol. 2018;6:186–194. doi: 10.2478/acb-2018-0029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Budna J, Celichowski P, Karimi P, Kranc W, Bryja A, Ciesiółka S, Rybska M, Borys S, Jeseta M, Bukowska D, et al. Does porcine oocytes maturation in vitro is regulated by genes involved in transforming growth factor beta receptor signaling pathway? Adv Cell Biol. 2017;5:1–14. doi: 10.1515/acb-2017-0001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curran T, Franza BR., Jr Fos and jun: The AP-1 connection. Cell. 1988;55:395–397. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Angel P, Karin M. The role of Jun, Fos and the AP-1 complex in cell-proliferation and transformation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1072:129–157. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(91)90011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rusovici R, LaVoie HA. Expression and distribution of AP-1 transcription factors in the porcine ovary. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:64–74. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.013995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson RS, Spiegelman BM, Papaioannou V. Pleiotropic effects of a null mutation in the c-fos proto-oncogene. Cell. 1992;71:577–586. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90592-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Müller R, Tremblay JM, Adamson ED, Verma IM. Tissue and cell type-specific expression of two human c-onc genes. Nature. 1983;304:454–456. doi: 10.1038/304454a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hattori MA, Kato Y, Fujihara N. Retinoic acid suppression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in porcine oocyte. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2002;80:777–782. doi: 10.1139/y02-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blaha M, Nemcova L, Kepkova KV, Vodicka P, Prochazka R. Gene expression analysis of pig cumulus-oocyte complexes stimulated in vitro with follicle stimulating hormone or epidermal growth factor-like peptides. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2015;13:113. doi: 10.1186/s12958-015-0112-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leung DW, Cachianes G, Kuang WJ, Goeddel DV, Ferrara N. Vascular endothelial growth factor is a secreted angiogenic mitogen. Science. 1989;246:1306–1309. doi: 10.1126/science.2479986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferrara N, Henzel WJ. Pituitary follicular cells secrete a novel heparin-binding growth factor specific for vascular endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;161:851–858. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(89)92678-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferrara N, Davis-Smyth T. The biology of vascular endothelial growth factor. Endocr Rev. 1997;18:4–25. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.1.0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sousa LM, Campos DB, Fonseca VU, Viau P, Kfoury JR, Jr, Oliveira CA, Binelli M, Buratini J, Jr, Papa PC. Vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) modulates bovine placenta steroidogenesis in vitro. Placenta. 2012;33:788–794. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shimizu T. Promotion of ovarian follicular development by injecting vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and growth differentiation factor 9 (GDF-9) genes. J Reprod Dev. 2006;52:23–32. doi: 10.1262/jrd.17072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McFee RM, Rozell TG, Cupp AS. The balance of proangiogenic and antiangiogenic VEGFA isoforms regulate follicle development. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;349:635–647. doi: 10.1007/s00441-012-1330-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bui TMT, Nguyễn KX, Karata A, Ferré P, Trần MT, Wakai T, Funahashi H. Presence of vascular endothelial growth factor during the first half of IVM improves the meiotic and developmental competence of porcine oocytes from small follicles. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2017;29:1902–1909. doi: 10.1071/RD16321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ravindranath N, Little-Ihrig L, Phillips HS, Ferrara N, Zeleznik AJ. Vascular endothelial growth factor messenger ribonucleic acid expression in the primate ovary. Endocrinology. 1992;131:254–260. doi: 10.1210/endo.131.1.1612003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamamoto S, Konishi I, Tsuruta Y, Nanbu K, Mandai M, Kuroda H, Matsushita K, Hamid AA, Yura Y, Mori T. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) during folliculogenesis and corpus luteum formation in the human ovary. Gynecol Endocrinol. 1997;11:371–381. doi: 10.3109/09513599709152564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu J, Xu M, Bernuci MP, Fisher TE, Shea LD, Woodruff TK, Zelinski MB, Stouffer RL. Primate follicular development and oocyte maturation in vitro. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;761:43–67. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-8214-7_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silva CM, Matos MH, Rodrigues GQ, Faustino LR, Pinto LC, Chaves RN, Araújo VR, Campello CC, Figueiredo JR. In vitro survival and development of goat preantral follicles in two different oxygen tensions. Anim Reprod Sci. 2010;117:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walters KA, Simanainen U, Handelsman DJ. Molecular insights into androgen actions in male and female reproductive function from androgen receptor knockout models. Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16:543–558. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmq003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gleicher N, Weghofer A, Barad DH. The role of androgens in follicle maturation and ovulation induction: Friend or foe of infertility treatment? Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2011;9:116. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-9-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lenie S, Smitz J. Functional AR signaling is evident in an in vitro mouse follicle culture bioassay that encompasses most stages of folliculogenesis. Biol Reprod. 2009;80:685–695. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.067280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li M, Ai JS, Xu BZ, Xiong B, Yin S, Lin SL, Hou Y, Chen DY, Schatten H, Sun QY. Testosterone potentially triggers meiotic resumption by activation of intra-oocyte SRC and MAPK in porcine oocytes. Biol Reprod. 2008;79:897–905. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.069245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Nieuwerburgh F, Stoop D, Cabri P, Dhont M, Deforce D, De Sutter P. Shorter CAG repeats in the androgen receptor gene may enhance hyperandrogenicity in polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2008;24:669–673. doi: 10.1080/09513590802342841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O'Donovan KJ, Tourtellotte WG, Millbrandt J, Baraban JM. The EGR family of transcription-regulatory factors: Progress at the interface of molecular and systems neuroscience. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:167–173. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(98)01343-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shin H, Seol DW, Nam M, Song H, Lee DR, Lim HJ. Expression of Egr3 in mouse gonads and its localization and function in oocytes. Asian-Australas J Anim Sci. 2017;30:781–787. doi: 10.5713/ajas.16.0798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thiel G, Müller I, Rössler OG. Expression, signaling and function of Egr transcription factors in pancreatic β-cells and insulin-responsive tissues. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2014;388:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Safford M, Collins S, Lutz MA, Allen A, Huang CT, Kowalski J, Blackford A, Horton MR, Drake C, Schwartz RH, Powell JD. Egr-2 and Egr-3 are negative regulators of T cell activation. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:472–480. doi: 10.1038/ni1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fang F, Ooka K, Bhattachyya S, Wei J, Wu M, Du P, Lin S, Del Galdo F, Feghali-Bostwick CA, Varga J. The early growth response gene Egr2 (alias Krox20) is a novel transcriptional target of transforming growth factor-β that is up-regulated in systemic sclerosis and mediates profibrotic responses. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:2077–2090. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nagarajan R, Svaren J, Le N, Araki T, Watson M, Milbrandt J. EGR2 mutations in inherited neuropathies dominant-negatively inhibit myelin gene expression. Neuron. 2001;30:355–368. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00282-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hu TM, Chen CH, Chuang YA, Hsu SH, Cheng MC. Resequencing of early growth response 2 (EGR2) gene revealed a recurrent patient-specific mutation in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2015;228:958–960. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Le N, Nagarajan R, Wang JY, Araki T, Schmidt RE, Milbrandt J. Analysis of congenital hypomyelinating Egr2Lo/Lo nerves identifies Sox2 as an inhibitor of schwann cell differentiation and myelination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:2596–2601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407836102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li X, Zhang Z, Yu M, Li L, Du G, Xiao W, Yang H. Involvement of miR-20a in promoting gastric cancer progression by targeting early growth response 2 (EGR2) Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:16226–16239. doi: 10.3390/ijms140816226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barbeau DJ, La KT, Kim DS, Kerpedjieva SS, Shurin GV, Tamama K. Early growth response-2 signaling mediates immunomodulatory effects of human multipotential stromal cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2014;23:155–166. doi: 10.1089/scd.2013.0194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jin H, Won M, Shin E, Kim HM, Lee K, Bae J. EGR2 is a gonadotropin-induced survival factor that controls the expression of IER3 in ovarian granulosa cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;482:877–882. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.11.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Burger HG. Inhibin: Definition and nomenclature, including related substances. J Endocrinol. 1988;117:159–160. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1170159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seder CW, Hartojo W, Lin L, Silvers AL, Wang Z, Thomas DG, Giordano TJ, Chen G, Chang AC, Orringer MB, Beer DG. Upregulated INHBA expression may promote cell proliferation and is associated with poor survival in lung adenocarcinoma. Neoplasia. 2009;11:388–396. doi: 10.1593/neo.81582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Howley BV, Hussey GS, Link LA, Howe PH. Translational regulation of inhibin βa by TGFβ via the RNA-binding protein hnRNP E1 enhances the invasiveness of epithelial-to- mesenchymal transitioned cells. Oncogene. 2016;35:1725–1735. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Katayama Y, Oshima T, Sakamaki K, Aoyama T, Sato T, Masudo K, Shiozawa M, Yoshikawa T, Rino Y, Imada T, Masuda M. Clinical significance of INHBA gene expression in patients with gastric cancer who receive curative resection followed by adjuvant s-1 chemotherapy. In Vivo. 2017;31:565–571. doi: 10.21873/invivo.11095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Donovan P, Dubey OA, Kallioinen S, Rogers KW, Muehlethaler K, Müller P, Rimoldi D, Constam DB. Paracrine activin-A signaling promotes melanoma growth and metastasis through immune evasion. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:2578–2587. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.07.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Locci M, Wu JE, Arumemi F, Mikulski Z, Dahlberg C, Miller AT, Crotty S. Activin A programs the differentiation of human TFH cells. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:976–984. doi: 10.1038/ni.3494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McKenzie LJ, Pangas SA, Carson SA, Kovanci E, Cisneros P, Buster JE, Amato P, Matzuk MM. Human cumulus granulosa cell gene expression: A predictor of fertilization and embryo selection in women undergoing IVF. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:2869–2874. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Assidi M, Dufort I, Ali A, Hamel M, Algriany O, Dielemann S, Sirard MA. Identification of potential markers of oocyte competence expressed in bovine cumulus cells matured with follicle-stimulating hormone and/or phorbol myristate acetate in vitro. Biol Reprod. 2008;79:209–222. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.067686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bristol-Gould SK, Kreeger PK, Selkirk CG, Kilen SM, Cook RW, Kipp JL, Shea LD, Mayo KE, Woodruff TK. Postnatal regulation of germ cells by activin: The establishment of the initial follicle pool. Dev Biol. 2006;298:132–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Myers M, Middlebrook BS, Matzuk MM, Pangas SA. Loss of inhibin alpha uncouples oocyte-granulosa cell dynamics and disrupts postnatal folliculogenesis. Dev Biol. 2009;334:458–467. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Maguire JJ, Davenport AP. Endothelin receptors and their antagonists. Semin Nephrol. 2015;35:125–136. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Asai R, Kurihara Y, Fujisawa K, Sato T, Kawamura Y, Kokubo H, Tonami K, Nishiyama K, Uchijima Y, Miyagawa-Tomita S, Kurihara H. Endothelin receptor type A expression defines a distinct cardiac subdomain within the heart field and is later implicated in chamber myocardium formation. Development. 2010;137:3823–3833. doi: 10.1242/dev.054015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kawamura K, Ye Y, Liang CG, Kawamura N, Gelpke MS, Rauch R, Tanaka T, Hsueh AJ. Paracrine regulation of the resumption of oocyte meiosis by endothelin-1. Dev Biol. 2009;327:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cui L, Shen J, Fang L, Mao X, Wang H, Ye Y. Endothelin-1 promotes human germinal vesicle-stage oocyte maturation by downregulating connexin-26 expression in cumulus cells. Mol Hum Reprod. 2018;24:27–36. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gax058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cheng JC, Chang HM, Fang L, Sun YP, Leung PC. TGF-β1 up-regulates connexin43 expression: A potential mechanism for human trophoblast cell differentiation. J Cell Physiol. 2015;230:1558–1566. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Salameh A, Haunschild J, Bräuchle P, Peim O, Seidel T, Reitmann M, Kostelka M, Bakhtiary F, Dhein S, Dähnert I. On the role of the gap junction protein Cx43 (GJA1) in human cardiac malformations with fallot-pathology. A study on paediatric cardiac specimen. PLoS One. 2014;9:e95344. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Edry I, Sela-Abramovich S, Dekel N. Meiotic arrest of oocytes depends on cell-to-cell communication in the ovarian follicle. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;252:102–106. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li SH, Lin MH, Hwu YM, Lu CH, Yeh LY, Chen YJ, Lee RK. Correlation of cumulus gene expression of GJA1, PRSS35, PTX3, and SERPINE2 with oocyte maturation, fertilization, and embryo development. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2015;13:93. doi: 10.1186/s12958-015-0091-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hasegawa J, Yanaihara A, Iwasaki S, Mitsukawa K, Negishi M, Okai T. Reduction of connexin 43 in human cumulus cells yields good embryo competence during ICSI. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2007;24:463–466. doi: 10.1007/s10815-007-9155-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang HX, Tong D, El-Gehani F, Tekpetey FR, Kidder GM. Connexin expression and gap junctional coupling in human cumulus cells: Contribution to embryo quality. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:972–984. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00373.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Amberger JS, Bocchini CA, Schiettecatte F, Scott AF, Hamosh A. OMIM.org: Online mendelian inheritance in man (OMIM®), an online catalog of human genes and genetic disorders. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D789–D798. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Calatayud NE, Pask AJ, Shaw G, Richings NM, Osborn S, Renfree MB. Ontogeny of the oestrogen receptors ESR1 and ESR2 during gonadal development in the tammar wallaby, Macropus eugenii. Reproduction. 2010;139:599–611. doi: 10.1530/REP-09-0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jameson JL, DeGroot LJ, De Kretser DM, Giudice LC, Grossman AB, Melmed S, Potts JT Jr, Weir GC, editors. 7th. Elsevier; Philadelphia, PA: 2016. Endocrinology: Adult & Pediatric. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Labrie F, Luu-The V, Lin SX, Simard J, Labrie C. Role of 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases in sex steroid formation in peripheral intracrine tissues. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2000;11:421–427. doi: 10.1016/S1043-2760(00)00342-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kuiper GG, Carlsson B, Grandien K, Enmark E, Häggblad J, Nilsson S, Gustafsson JA. Comparison of the ligand binding specificity and transcript tissue distribution of estrogen receptors alpha and beta. Endocrinology. 1997;138:863–870. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.3.4979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bondesson M, Hao R, Lin CY, Williams C, Gustafsson JÅ. Estrogen receptor signaling during vertebrate development. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1849:142–151. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Paterni I, Granchi C, Katzenellenbogen JA, Minutolo F. Estrogen receptors alpha (ERα) and beta (ERβ): Subtype-selective ligands and clinical potential. Steroids. 2014;90:13–29. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2014.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pelletier G, El-Alfy M. Immunocytochemical localization of estrogen receptors alpha and beta in the human reproductive organs. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:4835–4840. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.12.7029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nathan MR, Schmid P. A review of fulvestrant in breast cancer. Oncol Ther. 2017;5:17–29. doi: 10.1007/s40487-017-0046-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Artini PG, Tatone C, Sperduti S, D'Aurora M, Franchi S, Di Emidio G, Ciriminna R, Vento M, Di Pietro C, Stuppia L, et al. Cumulus cells surrounding oocytes with high developmental competence exhibit down-regulation of phosphoinositol 1, 3 kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/AKT) signalling genes involved in proliferation and survival. Hum Reprod. 2017;32:2474–2484. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Musgrove EA, Caldon CE, Barraclough J, Stone A, Sutherland RL. Cyclin D as a therapeutic target in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:558–572. doi: 10.1038/nrc3090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Robker RL, Richards JS. Hormone-induced proliferation and differentiation of granulosa cells: A coordinated balance of the cell cycle regulators cyclin D2 and p27Kip1. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:924–940. doi: 10.1210/mend.12.7.0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Han Y, Xia G, Tsang BK. Regulation of cyclin D2 expression and degradation by follicle-stimulating hormone during rat granulosa cell proliferation in vitro. Biol Reprod. 2013;88:57. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.112.105106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.François CM, Petit F, Giton F, Gougeon A, Ravel C, Magre S, Cohen-Tannoudji J, Guigon CJ. A novel action of follicle-stimulating hormone in the ovary promotes estradiol production without inducing excessive follicular growth before puberty. Sci Rep. 2017;7:46222. doi: 10.1038/srep46222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.