Abstract

Oxidative stress is a pathophysiological condition resulting in neurotoxicity, which is possibly associated with neurodegenerative disorders. In this study, the antioxidative effects of the antioxidant astaxanthin (AXT) in combination with huperzine A (HupA), which is used as a cholinesterase inhibitor for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease, were investigated. PC12 cells were treated with either tert-butyl hydroperoxide (TBHP), or with the toxic version of β-amyloid, Aβ25–35, to induce oxidative stress and neurotoxicity. Cell viability, morphology, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release, intracellular accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity and malondialdehyde (MDA) content were determined, while neuroprotection was also monitored using an MTT assay. It was found that combining AXT with HupA significantly increased the viability of PC12 cells, prevented membrane damage (as measured by LDH release), attenuated intracellular ROS formation, increased SOD activity and decreased the level of MDA after TBHP exposure when compared to these drugs administered alone. Pretreatment with HupA and AXT decreased toxic damage produced by Aβ25–35. These data indicated that combining an antioxidant with a cholinesterase inhibitor increases the degree of neuroprotection; with future investigation this could be a potential therapy used to decrease neurotoxicity in the brain.

Keywords: huperzine A, astaxanthin, PC12 cells, oxidative stress, neuroprotective

Introduction

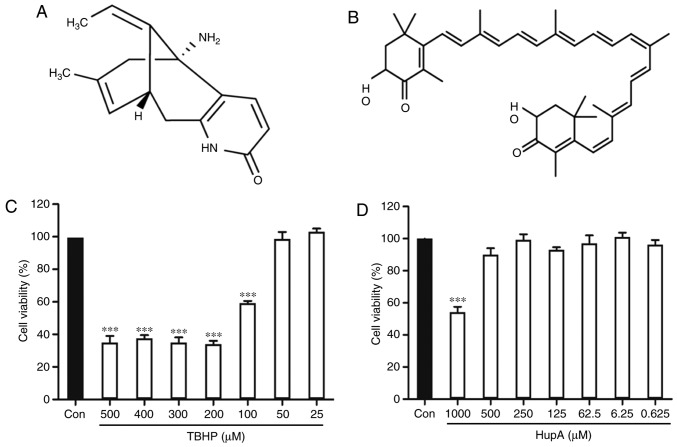

Oxidative stress reflects a disruption in the balance between antioxidant defences and the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (1). These ROS are produced by cell metabolism, and affect systemic and tissue immunity, and signal transduction (2). The accumulation of ROS instigates cell damage and death, thus contributing to neuropathology (3). This can lead to neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease (AD) and Parkinson's disease (4–7). One of the major symptomatic treatments of AD is to downregulate acetylcholinesterase (AChE), thereby increasing acetylcholine in the brain (8). The drugs employed are AChE inhibitors, including donepezil and tacrine. However, these are linked to a number of side effects such as diarrhea, nausea and anorexia (9). Huperzine A (HupA), as shown in Fig. 1A, has been isolated from the herb Lycopodium serratum, which is widely used in traditional Chinese medicine (10). HupA has been shown to alleviate oxidative stress and improve cognitive function in the elderly (11–19). Oxidative stress impairs cholinergic neurotransmission, therefore potentially accelerating cognitive decline (20). Thus, antioxidants may add to therapeutic strategies to attenuate neurotoxicity, improving neurological outcomes in neurodegenerative pathologies. Astaxanthin (AXT; C40H52O4; Fig. 1B) is an antioxidative carotenoid found in a variety of species, including crustaceans, fish, algae, yeast and bird feathers (21). The antioxidant capacity of AXT is ~1.5X that of vitamin E (22). This study reports on previously unknown findings concerning the synergistic antioxidative effects of combining AXT and HupA, using a previously established screening system to characterize therapeutic agents that can scavenge free radicals and protect cells from tert-butyl hydroperoxide (TBHP) (23).

Figure 1.

Chemical structure and cytotoxicity on the cell viability of PC12 cells. (A) Chemical structure of HupA and (B) Chemical structure of AXT. (C) Effect of the cytotoxicity of TBHP and (D) HupA on the cell viability of PC12 cells. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM; n=6/group, ***P<0.001 vs. control group. HuPA, huperzine A; AXT, astaxanthin; TBHP, tert-butyl hydroperoxide.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

HupA and AXT (>98% in purity) were purchased from Sichuan Weikeqi Biological Technology Co., Ltd. TBHP solution was purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 0.25% (w/v) trypsin solution were purchased from Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. Aβ25–35 was purchased from BIOSS. MTT and 2,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA. Kits for superoxide dismutase (SOD; cat no. A001-1), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH; cat no. BC2025) and malondialdehyde (MDA; cat no. A003-1) were purchased from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute Co., Ltd. All other chemicals were of analytical grade.

Cell culture and drug treatment

PC12 cells obtained from the Shanghai Institute of Cell Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% antibiotics (penicillin and streptomycin) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. HupA and AXT were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and diluted to 1 mM with serum-free DMEM.

TBHP-induced cell injury model

PC12 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 5×103 cells/well for 24 h. TBHP was freshly prepared from 30% stock solution prior to each experiment. Seeded cells were incubated with different concentrations (25, 50, 100, 200, 300, 400 and 500 µM) of TBHP for 24 h at 37°C. Subsequently, 20 µl MTT solution (5 mg/ml) was added for 4 h at 37°C. Finally, the supernatant was removed and the formazan crystals were dissolved in 150 µl DMSO. The amount of formazan was measured at 570 nm in a microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc.), with the formula: Cell viability (%)=absorption value experimental group/absorption value of control group ×100%. Cell viability in the control cells was expressed as 100%. The protective effect of HupA and AXT was quantified in the same conditions while cells were incubated with different concentrations of HupA (0.625, 6.25, 62.5, 125, 250, 500 and 1,000 µM) or AXT (0.01, 0.1, 1 and 20 µM) for 24 h at 37°C. The cell viability was determined by an MTT assay as described above.

Cells in the TBHP-induced injury model were incubated in separate groups: Control group (culture medium), model group (culture medium), HupA group (0.625, 6.25, 62.5, 125, 250 and 500 µM) and AXT group (0.01, 0.1, 1 and 10 µM) for 24 h at 37°C. Subsequently, 100 µM TBHP was added to all groups, except the control group which contained only culture medium, for 24 h. Finally, cell viability was determined via an MTT assay. Subsequently, the optimal effective concentrations of HupA and AXT were selected. PC12 cells were then incubated in separate groups with different conditions: Control group (culture medium), model group (culture medium), HupA group (500 µM), AXT group (0.1 µM) and HupA + AXT group (500 + 0.1 µM) for 24 h at 37°C. This was followed by the addition of 100 µM TBHP to all groups, except the control group, for 24 h. Finally, the cell viability was determined via an MTT assay.

Morphological assay

The cells were incubated at 37°C in separate groups: Control group, model group, HupA group (500 µM), AXT (0.1 µM) group and HupA + AXT group (500 µM + 0.1 µM). After processing, the cells were fixed by paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature. The cellular morphological changes were stained by hematoxylin-eosin staining for 15 min at room temperature and were examined under an inverted phase contrast microscope at a magnification of ×400 (Nikon Corporation).

LDH content in supernatant of culture medium

PC12 cells were seeded into 6-well plates, with 2.5×105 cells/well. After treatment as described above in the Morphological assay section, supernatant of the culture medium was collected to evaluate the LDH content. All samples were detected according to the manufacturer's protocols.

Measurement of ROS production

Intracellular accumulation of ROS was measured using DCFH-DA. PC12 were seeded into 6-well plates with 2.5×105 cells/well. After treatment, DCFH-DA (10 µM) was added at 37°C for 30 min in the dark. Thereafter, the cells were washed twice with PBS and harvested. The intracellular ROS levels were measured by flow cytometry. The mean fluorescence intensity was analyzed using NovoExpress 1.2.1 data analysis software (ACEA Biosciences). All experiments were performed at least three times.

Total SOD (T-SOD) and MDA content assays

After treatment, PC12 cells were harvested and washed with ice-cold PBS twice. The T-SOD content and MDA activity in cell homogenates were determined according to the manufacturer's protocols.

Ah25–35-induced cell injury

Aβ25–35 was dissolved in sterilized PBS at a concentration of 1 mM and incubated for 7 days at 37°C for aggregation. The solution was diluted in culture medium prior to each experiment. PC12 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 5×103 cells/well for 24 h. Then, cells were incubated with different concentrations (5, 10, 20 and 40 µM) of Aβ25–35 for 24 h at 37°C. Subsequently, MTT (20 µl) solution (5 mg/ml) was added to each well for 4 h at 37°C. Finally, the supernatant was removed and the formed formazan crystals were dissolved in 150 µl DMSO, and the plate was shaken for 10 min. Afterwards, the amount of the formazan was measured spectrophotometrically at 570 nm.

PC12 cells were cultured on 96-well plates and pretreated with HupA (0.625, 6.25, 62.5, 125, 250 and 500 µM) or AXT (0.01, 0.1, 1 and 10 µM) for 24 h before the introduction of Aβ25–35 (20 µM). Cell viability was determined using an MTT assay. Subsequently, the optimal effective concentrations of HupA and AXT were selected. Cells were incubated and separated in groups with different conditions: Control group (culture medium), model group (culture medium), HupA group (250 µM), AXT group (0.1 µM) and HupA + AXT group (250 + 0.1 µM) for 24 h at 37°C. Subsequently, Aβ25–35 (20 µM) was added to all groups, except the control group, for 24 h. Finally, the cell viability was determined via an MTT assay as aforementioned.

Statistical analysis

All results were expressed as the mean ± SEM and analyzed by SPSS 17.0 (SPSS, Inc.). The statistical significance of the differences between groups was analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

HupA and AXT have protective effects in the TBHP injury model

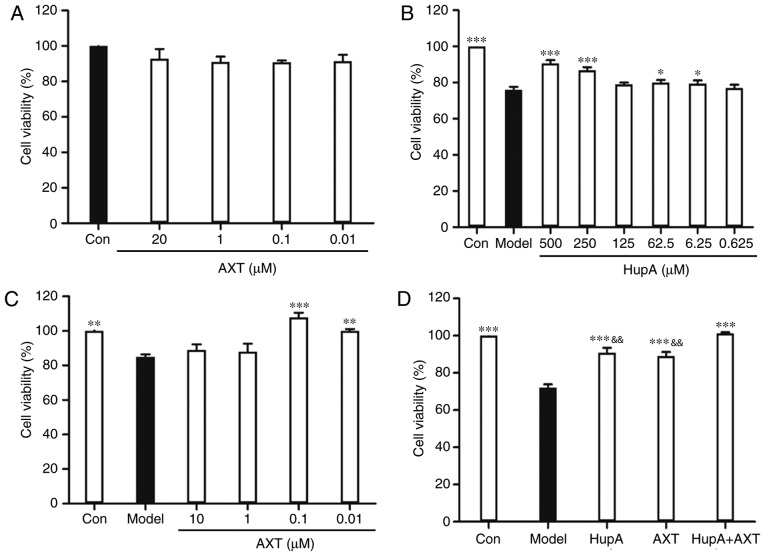

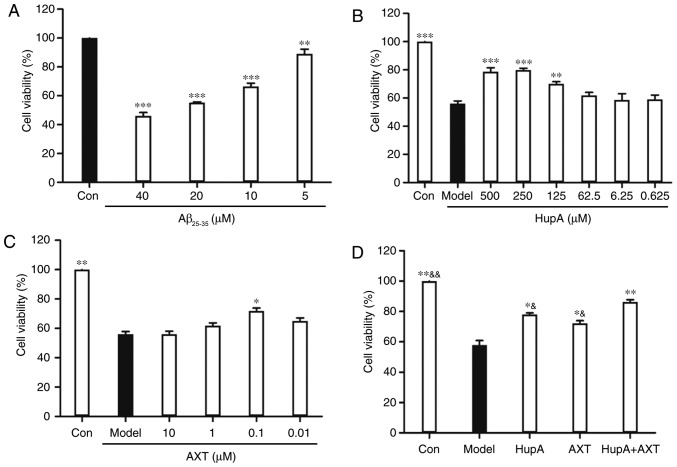

Incubation of PC12 cells with TBHP (100 µM) for 24 h reduced cell survival to 59.35±1.22% of the control value (Fig. 1C). In subsequent experiments, PC12 cells were pretreated with HupA or AXT for 24 h, with a subsequent addition of TBHP (100 µM) for 24 h. Exposure of PC12 cells to different concentrations of HupA (0.625, 6.25, 62.5, 125, 250 and 500 µM) and AXT (0.01, 0.1, 1 and 20 µM) in control conditions had no significant effect on cell survival (Figs. 1D and 2A), but a significant effect was observed at 1,000 µM HupA (Fig. 1D). This is due to DMSO being cytotoxic at certain concentrations. As presented in Fig. 2B, 90.75±1.67% (86.86±1.66%) of the cultured cells survived after 24 h treatment with 500 µM (250 µM) HupA, which meant that 250–500 µM HupA had protective effects against TBHP toxicity and that the most effective concentration of HupA was 500 µM. In Fig. 2C, 101.80±2.61% of the cultured cells survived after 24 h treatment with AXT (0.1 µM), so these concentrations were selected for use in the subsequent experiments. Cell viability of cells incubated with TBHP in the presence of HupA (500 µM), AXT (0.1 µM) and HupA + AXT (500 µM + 0.1 µM) was respectively 90.89±2.62, 89.73±2.29 and 101.34±0.51% of the control (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

Cytotoxicity or neuroprotective effect on PC12 cells. (A) Effects of the cytotoxicity of AXT on PC12 cells. (B) Neuroprotective effect of HupA, (C) AXT and (D) HupA + AXT on PC12 cells after 24 h exposure to TBHP. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM; n=6/group, *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. model group; &&P<0.01 vs. HupA + AXT group. AXT, astaxanthin; HupA, huperzine A; TBHP, tert-butyl hydroperoxide.

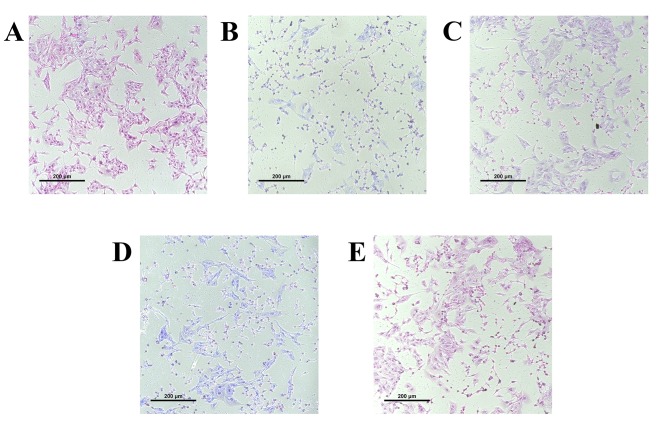

The morphology of the cultured cells was assessed using transmitted phase-contrast microscopy. The control group showed round cell bodies with clear edges and fine dendritic networks (Fig. 3A). Incubation with TBHP (100 µM) for 24 h induced the shrinkage of cell bodies and the disruption of dendritic networks, indicating that the cell injury model was successively established by TBHP induction (Fig. 3B). Following HupA, AXT and HupA + AXT pretreatment, these morphological manifestations marking cell damage in cells were alleviated, indicating that HupA, AXT and HupA + AXT may be able to prevent cell morphology damage by TBHP (Fig. 3C-E).

Figure 3.

Effects of HupA and AXT on TBHP-induced morphological alterations of PC12 cells (magnification, ×400). (A) Normal control without TBHP, (B) TBHP treatment, (C) HupA plus TBHP treated group, (D) AXT plus TBHP treated group and (E) HupA + AXT plus TBHP treated group. Cell morphology of PC12 cells was detected using an inverted phase contrast microscope. AXT, astaxanthin; HuPA, huperzine A; TBHP, tert-butyl hydroperoxide.

Measurement of LDH production

As shown in Table I, the concentration of LDH in the model group (313.42±9.55 U/l) was significantly higher than in the control group (145.57±12.11 U/l; P<0.001, n=3). However, both HupA (229.77±9.26 U/l) and AXT (201.28±13.81 U/l) groups were lower than the model group (P<0.001, n=3). Moreover, the HupA + AXT group (162.37±9.04) was significantly lower than the HupA group (P<0.01, n=3) and AXT group (P<0.05, n=3). These results indicated that while HupA or AXT could inhibit cell death caused by TBHP, the protective effect of HupA combined with AXT is higher than that of either HupA or AXT alone.

Table I.

Effects of HupA and AXT on LDH, SOD and MDA content in PC12 cells.

| Group | LDH (U/l) | SOD (U/ml) | MDA (nmol/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 145.57±12.11c | 46.27±2.11c,f | 0.96±0.46c,e |

| Model | 313.42±9.55 | 16.29±1.80 | 3.85±0.22 |

| TBHP + HupA | 229.77±9.26c,e | 19.33±2.46a,f | 3.43±0.13f |

| TBHP + AXT | 201.28±13.81c,d | 23.09±1.65b,d | 2.38±0.19c,e |

| TBHP + HupA + AXT | 162.37±9.04c | 29.44±2.12c | 1.67±0.11c |

P<0.05

P<0.01

P<0.001 vs. Model group

P<0.05

P<0.01

P<0.001 vs. TBHP + HupA + AXT group. AXT, astaxanthin; HupA, huperzine A; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MDA, malondialdehyde; SOD, superoxide dismutase; TBHP, tert-butyl hydroperoxide.

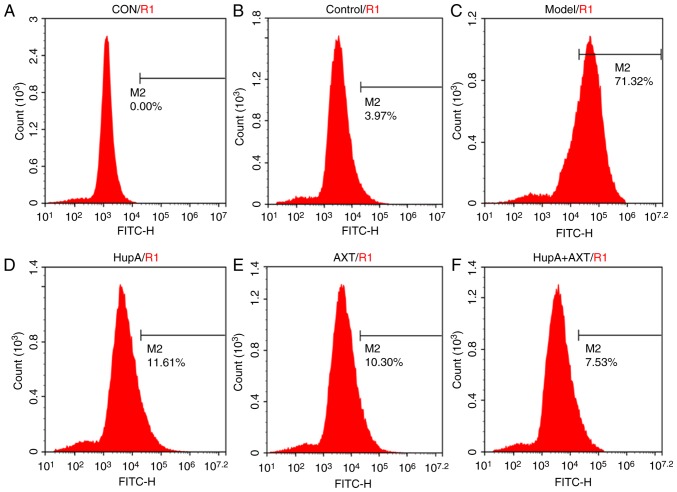

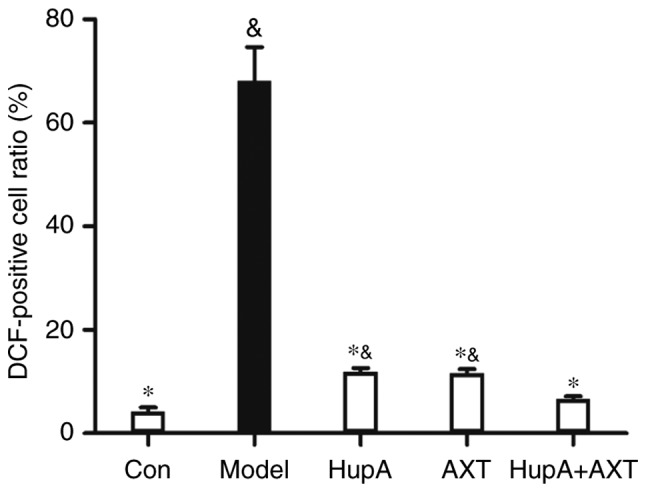

HupA + AXT decreases intracellular ROS accumulation in the TBHP injury model

As presented in Figs. 4 and 5, the intracellular ROS level of PC12 cells measured by flow cytometry was visibly increased after being exposed to TBHP (100 µM) for 24 h (Fig. 4C; Fig. 4A was the control group without DCFH-DA and Fig. 4B was the control group with DCFH-DA). However, with the pretreatment of HupA, AXT and HupA + AXT, the ROS levels were reduced from 68.07±6.56% in the model group to 11.91±0.79% (P<0.05, n=3; Fig. 4D), 11.67±0.75% (P<0.05, n=3; Fig. 4E) and 6.12±0.82% (P<0.05, n=3; Fig. 4F), respectively. The HupA + AXT group is significantly lower than the HupA (P<0.05, n=3) and AXT group (P<0.05, n=3). This further demonstrated the increased protective effect of combining HupA and AXT.

Figure 4.

Effect of HupA and AXT on TBHP-induced intracellular accumulation of reactive oxygen species. Cells were maintained in (A) culture medium without 2,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate, (B) culture medium, (C) TBHP, (D) TBHP + HupA, (E) THBP + AXT, (F) THBP + HupA + AXT. AXT, astaxanthin; HuPA, huperzine A; TBHP, tert-butyl hydroperoxide.

Figure 5.

Quantification of flow cytometry. Data were presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. *P<0.05 vs. Model group; &P<0.05 vs. HUPA + AXT group. AXT, astaxanthin; HuPA, huperzine A.

Effects of HupA and AXT on MDA content and T-SOD activity in PC12 cells

As shown in Table I, in the presence of TBHP, MDA levels were increased from 0.96±0.46 to 3.85±0.22 nmol/ml (P<0.001, n=3), while SOD levels were decreased from 46.27±2.11 to 16.29±1.80 U/ml (P<0.001, n=3). Pre-incubation with HupA significantly decreased the level of MDA to 3.43±0.13 nmol/ml and increased the activity of SOD to 19.33 U/ml (P<0.05, n=3). Pre-incubation with AXT significantly decreased the level of MDA to 2.38±0.19 (P<0.001, n=3) and increased the activity of SOD to 23.09±1.65 (P<0.01, n=3). The MDA level of HupA + AXT group (1.67±0.11) was significantly lower than the HupA (P<0.001, n=3) and AXT group (P<0.01, n=3). The SOD level of the HupA + AXT group (29.44±2.12) was significantly higher than the HupA (P<0.001, n=3) and AXT group (P<0.01, n=3), thus indicating again that HupA and AXT in combination are more effective than when used alone.

HupA and AXT decrease Aβ25–35-induced cytotoxicity

As shown in Fig. 6A, the cell viability of PC12 cells after treatment with 5, 10, 20 and 40 µM of Aβ25–35 was 89.36±3.26, 66.51±2.26, 55.29±0.46 and 46.94±2.32% of the control groups, respectively (n=5). Based on the results above, the concentration of 20 µM Aβ25–35 was used for further studies. After pretreatment with HupA (250 µM) and AXT (0.1 µM) cell viability was 79.85±1.27 and 71.89±1.97%, (Fig. 6B and C), respectively. Although there was no statistical difference in viability between the 250 and 500 µM HupA group (Fig. 6B), the cell viability in the 250 µM group was still higher than in the 500 µM group. So, 250 µM was chosen as the optimal dose in the Aβ25–35-induced PC12 cell model study. To determine whether the combination of HupA and AXT had a better neuroprotective effect than HupA or AXT alone, the optimal effective concentrations of HupA (250 µM) and AXT (0.1 µM) were selected. Fig. 6D showed that pretreatment with HupA, AXT and HupA + AXT increased the cell viability to 78.09±1.84, 72.17±1.21 and 86.21±1.51% (n=5).

Figure 6.

Cytotoxicity or neuroprotective effect on PC12 cells. (A) Effects of the cytotoxicity of Aβ25–35 on the cell viability of PC12 cells. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM; n=6/group. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. control group. Neuroprotective effect of (B) HupA, (C) AXT and (D) HupA + AXT on PC12 cells after 24 h exposure to Aβ25–35. Data were presented as the mean ± SEM; n=6/group. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. model group; &P<0.05, &&P<0.01 vs. HupA + AXT group. AXT, astaxanthin; HuPA, huperzine A; TBHP, tert-butyl hydroperoxide.

Discussion

Oxidative stress contributes to the progression of neurodegeneration by increasing neuronal cell death (20). Therefore, the elimination of excess ROS or an increase in the capacity of endogenous antioxidative activity may provide a rational strategy in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases (24). The pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases involves multiple mechanisms, so a combination of two or more drugs with different targets may be advantageous over single drug treatments (25,26).

Pre-treatment with HupA and AXT significantly reduced cell death in the TBHP injury model. Furthermore, combining HupA and AXT was more effective compared with the administration of a single drug. However, there is a potential limitation of the study. In Fig. 2C, the optimal dose of AXT combined with TBHP was determined to be 0.1 µM, with a cell viability of 101.80±2.61%, but in Fig. 2D, the cell viability was 89.73±2.29% following treatment with 0.1 µM AXT + TBHP. This shows a discrepancy between the AXT treatment groups despite using the same optimal dose (0.1 µM). Because AXT was dissolved in DMSO and it was diluted to 1 µM with serum-free DMEM as the original liquid, it is possible that the AXT used in Fig. 2D was partially decomposed due to its long time in storage.

According to cell morphological analysis, TBHP can cause a disruption to dendritic networks and the shrinkage of cell bodies; HupA and AXT can rescue both of these impairments. Another effect of TBHP toxicity is associated with increased levels of LDH, which disrupts cell membrane permeability (27). Incubation with TBHP increased the concentrations of LDH in the culture medium, whereas HupA and AXT reduce LDH. These results demonstrated that HupA and AXT can protect PC12 cells from oxidative damage; however, it is the combination of both drugs that offers the higher degree of protection.

Another mechanism by which HupA and AXT exert their antioxidant effects may be associated with direct ROS scavenging. Levels of intracellular ROS were determined by monitoring the conversion of DCFH-DA to dichlorofluorescein (DCF). The fluorescent signal of DCF was enhanced in the TBHP injury model, while this increase in fluorescence was notably alleviated by pre-treatment with HupA and AXT. These results suggested that the antioxidant effects of HupA and AXT could result from the inhibition of intracellular ROS production. Again, combining both drugs increased the degree of antioxidative protection.

Oxidative damage caused by ROS is usually accompanied by an increase in lipid peroxidation (28). MDA was used as an index to estimate the degree of lipid peroxidation (29). SOD is regarded as an important protective system to prevent damage caused by ROS (30); in the TBHP injury model the SOD activity was decreased, whereas MDA levels were increased. Pretreatment of cells with HupA and AXT reversed these changes, indicating that the enhancement of SOD activity and the inhibition of lipid peroxides may represent another antioxidant mechanism of HupA and AXT.

In order to further verify the relationship between oxidative stress and neurotoxicity, the degree of protection of HupA and AXT on the Aβ25–35-treated PC12 AD cells model was evaluated via an MTT assay. Results indicated that HupA and AXT increased cell viability, especially when used in combination.

In summary, this study demonstrated that HupA and AXT protected PC12 cells against TBHP-induced cell oxidative stress and against Aβ25–35 toxicity. Combining both of these drugs further increased the degree of cell protection. Therefore, a therapeutic combination of HupA and AXT could be beneficial in the treatment of AD and other neurodegenerative diseases.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was financially supported by Guangzhou Traditional Chinese Medicine and Integrated Chinese and Western Medicine Science and Technology Project (grant no. 20192A011019).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

XY, HMW, HKZ and HN participated in the design of the study and preparation of the manuscript. GYH, JZ and LNL performed most of the experiments. CJL and ZJZ carried out the statistical analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Migdal C, Serres M. Reactive oxygen species and oxidative stress. Med Sci (Paris) 2011;27:405–412. doi: 10.1051/medsci/2011274017. (In French) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Byun EB, Park WY, Kim WS, Song HY, Sung NY, Byun EH. Neuroprotective effect of Capsicum annuum var. Abbreviatum against hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress in HT22 hippocampus cells. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2018;82:2149–2157. doi: 10.1080/09168451.2018.1460572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sullivan PG, Rabchevsky AG, Waldmeier PC, Springer JE. Mitochondrial permeability transition in CNS trauma: Cause or effect of neuronal cell death? J Neurosci Res. 2005;79:231–239. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Namioka N, Hanyu H, Hirose D, Hatanaka H, Sato T, Shimizu S. Oxidative stress and inflammation are associated with physical frailty in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Geriater Gerontol Int. 2017;17:913–918. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sankhla CS. Oxidative stress and Parkinson's disease. Neurol India. 2017;65:269–270. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.201842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uttara B, Singh AV, Zamboni P, Mahajan RT. Oxidative stress and neurodegenerative diseases: A review of upstream and downstream antioxidant therapeutic options. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2009;7:65–74. doi: 10.2174/157015909787602823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wadhwa R, Gupta R, Maurya PK. Oxidative stress and accelerated aging in neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorder. Curr Pharm Des. 2018;24:4711–4725. doi: 10.2174/1381612825666190115121018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shinotoh H, Namba H, Fukushi K, Nagatsuka S, Tanaka N, Aotsuka A, Ota T, Tanada S, Irie T. Progressive loss of cortical acetylcholinesterase activity in association with cognitive decline in Alzheimer's disease: A positron emission tomography study. Ann Neurol. 2000;48:194–200. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(200008)48:2<194::AID-ANA9>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mimica N, Presecki P. Side effects of approved antidementives. Psychiat Danub. 2009;21:108–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng DH, Ren H, Tang XC. Huperzine A, a novel promising acetylcholinesterase inhibitor. Neuroreport. 1996;8:97–101. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199612200-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang R, Zhang HY, Tang XC. Huperzine A attenuates cognitive dysfunction and neuronal degeneration caused by beta-amyloid protein-(1–40) in rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;421:149–156. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(01)01030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mei Z, Zheng P, Tan X, Wang Y, Situ B. Huperzine A alleviates neuroinflammation, oxidative stress and improves cognitive function after repetitive traumatic brain injury. Metab Brain Dis. 2017;32:1861–1869. doi: 10.1007/s11011-017-0075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu Z, Wang Y. Huperzine A attenuates hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury via anti-oxidative and anti-apoptotic pathways. Mol Med Rep. 2014;10:701–706. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi Q, Fu J, Ge D, He Y, Ran J, Liu Z, Wei J, Diao T, Lu Y. Huperzine A ameliorates cognitive deficits and oxidative stress in the hippocampus of rats exposed to acute hypobaric hypoxia. Neurochem Res. 2012;37:2042–2052. doi: 10.1007/s11064-012-0826-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pohanka M, Zemek F, Bandouchova H, Pikula J. Toxicological scoring of Alzheimer's disease drug huperzine in a guinea pig model. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2012;22:231–235. doi: 10.3109/15376516.2011.635320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang HY, Zheng CY, Yan H, Wang ZF, Tang LL, Gao X, Tang XC. Potential therapeutic targets of huperzine A for Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. Chem Biol Interact. 2008;175:396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2008.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao X, Tang XC. Huperzine A attenuates mitochondrial dysfunction in beta-amyloid-treated PC12 cells by reducing oxygen free radicals accumulation and improving mitochondrial energy metabolism. J Neurosci Res. 2006;83:1048–1057. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiao XQ, Wang R, Tang XC. Huperzine A and tacrine attenuate beta-amyloid peptide-induced oxidative injury. J Neurosci Res. 2000;61:564–569. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20000901)61:5<564::AID-JNR11>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiao XQ, Wang R, Han YF, Tang XC. Protective effects of huperzine A on beta-amyloid(25–35) induced oxidative injury in rat pheochromocytoma cells. Neurosci Lett. 2000;286:155–158. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(00)01088-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saxena G, Singh SP, Agrawal R, Nath C. Effect of donepezil and tacrine on oxidative stress in intracerebral streptozotocin-induced model of dementia in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;581:283–289. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ambati RR, Phang SM, Ravi S, Aswathanarayana RG. Astaxanthin: Sources, extraction, stability, biological activities and its commercial applications-a review. Mar Drugs. 2014;12:128–152. doi: 10.3390/md12010128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naguib YM. Antioxidant activities of astaxanthin and related carotenoids. J Agric Food Chem. 2000;48:1150–1154. doi: 10.1021/jf991106k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang Y, Liu X, Huang J, Zhong Y, Mao Z, Xiao H, Li M, Zhuo Y. Inhibition of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylation decrease tert-butyl hydroperoxide-induced apoptosis in human trabecular meshwork cells. Mol Vis. 2012;18:2127–2136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brookmeyer R, Johnson E, Ziegler-Graham K, Arrighi HM. Forecasting the global burden of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2007;3:186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.04.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu W, Liu BH, Xie CL, Xia XD, Zhang YM. Neuroprotective effects of N-acetyl cysteine on primary hippocampus neurons against hydrogen peroxide-induced injury are mediated via inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinases signal transduction and antioxidative action. Mol Med Rep. 2018;17:6647–6654. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.8699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee JH, Park SY, Shin YW, Kim CD, Lee WS, Hong KW. Concurrent administration of cilostazol with donepezil effectively improves cognitive dysfunction with increased neuroprotection after chronic cerebral hypoperfusion in rats. Brain Res. 2007;1185:246–255. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cachard-Chastel M, Devers S, Sicsic S, Langlois M, Lezoualc'H F, Gardier AM, Belzung C. Prucalopride and donepezil act synergistically to reverse scopolamine-induced memory deficit in C57Bl/6j mice. Behav Brain Res. 2008;187:455–461. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma S, Liu X, Xun Q, Zhang X. Neuroprotective effect of Ginkgolide K against H2O2-induced PC12 cell cytotoxicity by ameliorating mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress. Biol Pharm Bull. 2014;37:217–225. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b13-00378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Z, Lv Z, Shao Y, Qiu Q, Zhang W, Duan X, Li Y, Li C. Microsomal glutathione transferase 1 attenuated ROS-induced lipid peroxidation in Apostichopus japonicus. Dev Comp Immunol. 2017;73:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2017.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suzuki S, Miyachi Y, Niwa Y, Isshiki N. Significance of reactive oxygen species in distal flap necrosis and its salvage with liposomal SOD. Br J Plast Surg. 1989;42:559–564. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(89)90045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.