Abstract

Background: Whether radioactive iodine (131I) treatments for differentiated thyroid cancer should be performed as an outpatient or inpatient remains controversial. The objective of this study was to survey selected aspects of radiation safety of patients treated with 131I for differentiated thyroid cancer as an outpatient.

Methods: An e-mail invitation was sent to over 15,000 members of ThyCa: Thyroid Cancer Survivors' Association, Inc. to complete a web-based survey on selected aspects of radiation safety regarding their last outpatient 131I treatment.

Results: A total of 1549 patients completed the survey. Forty-five percent (699/1541) of the respondents reported no discussion on the choice of an inpatient or outpatient treatment. Moreover, 5% (79/1541) of the respondents reported that their insurance company made the decision. Survey respondents recalled receiving oral and written radiation safety instructions 97% (1459/1504) and 93% (1351/1447) of the time, respectively. Nuclear medicine physicians delivered oral and written instructions to 54% (807/1504) and 41% (602/1462) of the respondents, respectively. Eighty-eight percent (1208/1370) of the respondents were discharged within 1 hour after receiving their 131I treatment, and 97% (1334/1373) traveled in their own car after being released from the treating facility. Immediately post-therapy, 94% (1398/1488) of the respondents stayed at their own home or a relative's home, while 5% (76/1488) resided in a public lodging. The specific recommendations received by patients about radiation precautions varied widely among the respondents. Ninety-nine percent (1451/1467) of the respondents believed they were compliant with the instructions.

Conclusion: This is the largest, patient-based survey published regarding selected radiation safety aspects of outpatient 131I treatment. This survey suggests several concerns about radiation safety, such as the decision process regarding inpatient versus outpatient treatment, instructions about radiation safety, transportation, and lodging after radioiodine therapy. These concerns warrant further discussion, guidelines, and/or policies.

Keywords: : differentiated thyroid cancer, radioiodine, 131I, radiation safety, outpatient

Introduction

Radioactive iodine (131I) is important in the treatment of many patients with differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC); however, controversies persist regarding radiation safety practices and the subsequent risks to individuals irradiated by exposure to patients treated with 131I (1).

In 1997, the United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) changed the release requirements for patients treated with 131I from a prescribed activity–based limit to an absorbed dose–based limit. According to the Title 10, section 35.75 of the Code of Federal Regulations, treating facilities may release patients based on dose calculations using patient-specific parameters (2,3). In practice, this means that patients may be released with higher levels of radioactivity than the previously permissible levels of 1.22 GBq (33 mCi) of 131I. These requirements have raised concern about radiation exposure levels to the public and the environment, and in many cases have altered the behavior of the patients treated with 131I after their release.

Adherence to radiation safety practices in patients treated with 131I is important to minimize exposure to family members and the public, and the American Thyroid Association (ATA) released practice recommendations for radiation safety in the treatment of patients with thyroid diseases by 131I (4). These recommendations comprise oral and written instructions to be provided to the patients, and these instructions must include information on reproduction, breastfeeding, traveling, and radiation detection at ports of entry, among others. Similarly, the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging has addressed radiation safety issues for therapy of thyroid disease with 131I, including staff protection and instructions to the patients regarding mode of transportation, lodging, personal contact, personal hygiene, and parenthood (5).

Several previous surveys have been published on radiation safety for 131I therapy, but these surveys were not completed by patients and not necessarily on outpatient 131I therapies (6,7). The objective of this study was to perform an epidemiological national survey of patients who were treated with 131I for DTC as an outpatient to characterize selected aspects of radiation safety of these treatments.

Methods

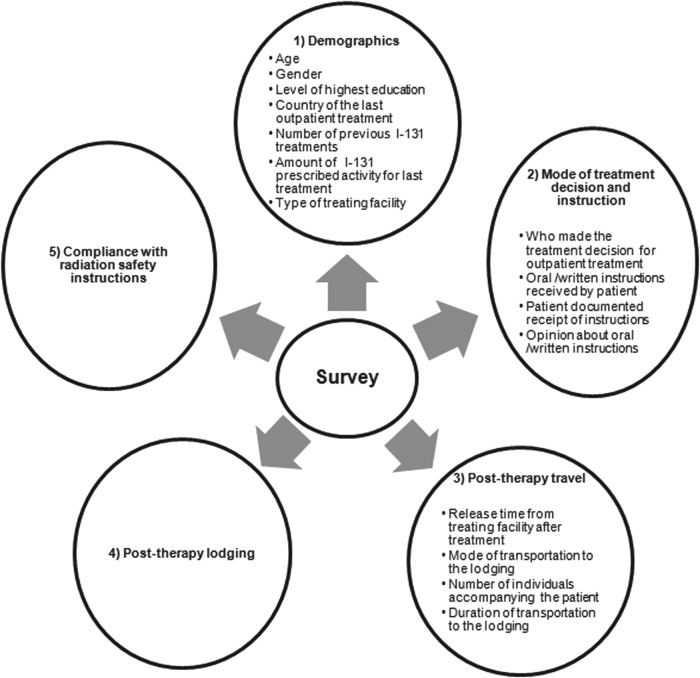

The survey was administered via a web-based, commercial survey management service (SurveyMonkey, Palo Alto, CA). Figure 1 depicts an overview of the survey topics. The entire survey is available in the Supplementary Data (Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/thy).

FIG. 1.

Overview of survey topics.

Question designs

The survey was developed by a team involving two nuclear medicine physicians, three endocrinologists, three 131I-treated DTC patients, one statistician, and one professional survey developer. Five patients with DTC, previously treated with radioiodine, completed a trial survey with subsequent modifications. The majority of questions required a single best response to be selected from multiple choices. When more than one answer could be provided, an option of “select all that apply” was present. Several questions allowed text comments. In order to ensure survey completion and minimize survey “fatigue,” the survey was designed to be brief, easy to comprehend, and completed in less than 10 minutes. The survey of 29 questions was sent to over 15,000 members of Thyroid Cancer Survivors' Association (see entire survey in the supplemental data). Each patient was asked to respond only for his/her last 131I treatment, and responses of “don't remember” were excluded. The survey was open from September 2010 to May 2011 and could only be completed once for each IP address. The study was approved by the MedStar Institutional Review Board.

Results

A total of 1549 patients completed the survey. Table 1 presents the demographics. The denominator changes according to the number of respondents of each question of the survey. Ninety percent (1399/1542) of respondents were female, and 99% (1538/1544) of respondents had completed high school or a higher level of education. Table 2 presents data about the last outpatient 131I therapy. Ninety-six percent (1487/1543) of respondents were treated in the United States. Only patients treated after 1997 were included in the final analysis, and 72% (1119/1579) of respondents received therapy within three years from answering the survey. Thirty-nine percent (424/1072) of respondents were administered at least 5.5 GBq (150 mCi) as an outpatient, with 11% (116/1072) administered over 7.4 GBq (200 mCi) as an outpatient. 131I was administered in a hospital facility 89% (1367/1537) of the time. Table 3 notes the responses regarding the decision-making process for an outpatient treatment. The physician made the decision 75% (1162/1541) of the time, and the respondents aided in that decision by completing a form only 21% (320/1541) of the time. Reportedly, no decision-making discussion was held with 45% (699/1541) of the patients. The insurance company would not authorize payment for an inpatient therapy for 5% (79/1541) of the respondents. Table 4 presents the data on oral instructions, and the opinion about the quality of oral radiation safety instructions is presented in Supplementary Table S1. Table 5 presents the data on written instructions; the opinion about the quality of written radiation safety instructions is presented in the Supplementary Table S2. Of the total respondents, 97% (1459/1504) of patients received oral radiation safety instructions, and 93% (1351/1447) received written instructions. Only 72% (1023/1420) and 69% (933/1355) received oral or written instructions, respectively, that warned about the potential to set off security alarms. Radiation safety instructions were provided by various medical professionals, most commonly by the nuclear medicine physicians or staff. Table 6 presents the data for release time and travel after the outpatient 131I treatment. Eighty-eight percent (1208/1370) of patients were released within one hour after 131I administration. Five percent (74/1372) of respondents traveled two hours or more, and only 0.4% (5/1373) used public transportation. The correlation of doses of 131I to different aspects of transportation is presented in Supplementary Tables S3–S6). Table 7 presents the data for lodging, and Supplementary Table S7 correlates doses of 131I to lodging. For accommodation, 94% (1398/1488) of patients resided in their own home or a relative's home, while 5% (76/1488) resided in a hotel, motel, or boarding house (public lodging). The compliance with different radiation safety instructions is presented in Supplementary Tables S8–S12. These tables correlate the number of days the patient was told to follow a certain instruction with the number of days the patient complied with that instruction. Table 8 presents data on the patients' perception of his/her overall compliance. Supplementary Tables S13, S14, and S15 display data on (i) the degree of anxiety of patients about radiation exposure, (ii) their preference for outpatient or inpatient treatment in the future, and (iii) their evaluation of the treating facility and physician staff, respectively.

Table 1.

Demographics of Respondents

| Baseline characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | 1542 | |

| Female | 1399 | 90.7 |

| Male | 143 | 9.3 |

| Age | 1525 | |

| Mean ± SD | 45.6 ± 11.6 | |

| Range | 9–86 | |

| Level of Education | 1544 | |

| Elementary | 1 | 0.1 |

| Middle school | 5 | 0.3 |

| High school | 294 | 19 |

| College | 832 | 53.9 |

| Graduate School | 412 | 26.7 |

| Total number of treatments to date | 1254 | |

| 1 | 887 | 70.7 |

| 2 | 253 | 20.2 |

| 3 | 75 | 6 |

| 4 | 21 | 1.7 |

| 5 | 7 | 0.5 |

| 6 | 6 | 0.5 |

| 7 or more | 5 | 0.4 |

Table 2.

Last Outpatient Radioactive Iodine Treatment

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Country of the last outpatient 131I treatment | 1543 | |

| United States | 1487 | 96.4 |

| Canada | 29 | 1.9 |

| United Kingdom | 11 | 0.7 |

| Mexico | 3 | 0.2 |

| Australia | 2 | 0.1 |

| Other | 11 | 0.7 |

| Year of the last outpatient 131I treatment | 1549 | |

| 1997–1999 | 15 | 1 |

| 2000–2004 | 185 | 11.9 |

| 2005 | 91 | 5.9 |

| 2006 | 139 | 9 |

| 2007 | 186 | 12 |

| 2008 | 329 | 21.2 |

| 2009 | 604 | 39 |

| Prescribed 131I activity as outpatient | 1072 | |

| Less than 1.11 GBq (<30 mCi) | 70 | 6.5 |

| 1.11–1.8 GBq (30-49 mCi) | 58 | 5.4 |

| 1.85–2.74 GBq (50-74 mCi) | 60 | 5.6 |

| 2.78–3.66 GBq (75-99 mCi) | 91 | 8.5 |

| 3.7–5.5 GBq (100-149 mCi) | 369 | 34.5 |

| 5.5–7.36 GBq (150-199 mCi) | 308 | 28.7 |

| 7.4–9.2 GBq (200-249 mCi) | 72 | 6.7 |

| 9.25–11.0 MBq (250-299 mCi) | 18 | 1.7 |

| 11.1–12.9 MBq (300-349 mCi) | 10 | 1 |

| 13.0–14.8 MBq (350-399 mCi) | 5 | 0.4 |

| 14.8– 16.6 MBq (400-449 mCi) | 2 | 0.2 |

| 16.75–18.5 MBq (450-499 mCi) | 2 | 0.2 |

| More than 18.5 MBq (>500 mCi) | 7 | 0.6 |

| Type of treatment facility | 1537 | |

| Outpatient nonhospital | 170 | 11.1 |

| Community hospital, small | 134 | 8.7 |

| Community hospital, large | 802 | 52.2 |

| University hospital | 416 | 27 |

| Veterans Administration hospital | 6 | 0.4 |

| Military hospital | 9 | 0.6 |

I, radioactive iodine

Table 3.

Factors in the Decision-Making of Treatment Settinga

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| The amount of 131I prescribed activity was below 1.22 GBq (33 mCi) | 135 | 8.8 |

| The physician made the decision | 1162 | 75.4 |

| The patient made the decision | 174 | 11.3 |

| The insurance company would not authorize payment for an inpatient 131I treatment | 79 | 5.2 |

| The patient completed a form to determine whether or not his/her living situation would allow the outpatient treatment | 320 | 20.8 |

| There was no discussion regarding the options of being treated as an inpatient or outpatient | 699 | 45.3 |

More than one answer was possible for this question. Number of respondents: 1541

Table 4.

Oral Instructions on Radiation Safety

| Content of instruction | Yes | No | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| To reduce as low as is reasonably achievable radiation exposure from 131I to other individuals | 1459 (97%) | 45 (3%) | 1504 |

| To discontinue breast feeding (if you were breast feeding) and the potential consequences to your infant or child if the instructions were not followed | 433 (90%) | 48 (10%) | 481 |

| About detectable amounts of 131I, which may set off a security radiation monitoring alarm that may be located in such places as roadway tunnels, airports or boarding crossings | 1023 (72%) | 397 (28%) | 1420 |

| The name and telephone number of a person or department to call in the event you or security personnel had questions about your 131I treatment | 1016 (72.5%) | 384 (27.5) | 1400 |

| Signature on a form about compliance | Yes | No | |

| 980 (85.9%) | 160 (14.1%) | 1510 | |

| Oral instructions provided bya | 1504 | ||

| Nuclear Medicine physician | 807 (53.6%) | ||

| Radiation Oncologist or Radiation Therapist | 284 (18.9%) | ||

| Endocrinologist | 354 (23.5%) | ||

| Nuclear Radiologist | 293 (19.5%) | ||

| Technologist | 201 (13.3%) | ||

| Radiation Safety Physicist | 77 (5.1%) | ||

| Radiation Safety Technologist | 178 (11.8%) | ||

| Nurse | 215 (14.3%) | ||

| Administrator | 26 (1.7%) | ||

| Other | 28 (1.9%) | ||

More than one answer was possible for this question.

Table 5.

Written Instructions on Radiation Safety

| Yes (n) | No (n) | Total (N) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Content of instruction | |||

| To reduce as low as is reasonably achievable radiation exposure from 131I to other individuals | 1351 (93.4%) | 96 (6.6%) | 1447 |

| To discontinue breast feeding (if you were breast feeding) and the potential consequences to the infant or child if the instructions were not followed | 487 (87.3%) | 71 (12.7%) | 558 |

| About detectable amounts of 131I, which may set off a security radiation monitoring alarm that may be located in such places as roadway tunnels, airports, or boarding crossings | 933 (68.9%) | 422 (31.1%) | 1355 |

| The name and telephone number of a person or department to call in the event you or security personnel had questions about your 131I treatment | 1035 (75.9%) | 329 (24.1%) | 1364 |

| Signed compliance form | 953 (86.1%) | 154 (13.9%) | 1107 |

| Written instructions provided bya | 1462 | ||

| Nuclear medicine physician | 602 (41.2%) | ||

| Radiation oncologist or radiation therapist | 238 (16.3%) | ||

| Endocrinologist | 254 (16.8%) | ||

| Nuclear radiologist | 243 (16.6%) | ||

| Technologist | 171 (11.7%) | ||

| Radiation safety physicist | 69 (4.7%) | ||

| Radiation safety technologist | 155 (10.6%) | ||

| Nurse | 195 (13.3%) | ||

| Administrator | 20 (1.4%) | ||

| Other | 25 (1.7%) | ||

More than one answer was possible for this question.

Table 6.

Release Time and Travel After the Outpatient 131I Treatment

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Release time after 131I administration (1370 respondents) | ||

| Immediately (within 30 min) | 970 | 70.8 |

| 30 to 59 min | 238 | 17.4 |

| 1 to 2 hours | 116 | 8.5 |

| 2 to 3 hours | 21 | 1.5 |

| 3 to 4 hours | 8 | 0.5 |

| 4 to 5 hours | 2 | 0.2 |

| 5 to 6 hours | 4 | 0.3 |

| 6 to 7 hours | 2 | 0.2 |

| 7 to 8 hours | 0 | 0 |

| 8 or more hours | 9 | 0.6 |

| Mode of transportation (1373 respondents) | ||

| Car | 1334 | 97.1 |

| Taxi | 19 | 1.4 |

| Bus | 1 | 0.1 |

| Train | 1 | 0.1 |

| Subway | 3 | 0.2 |

| Airplane | 0 | 0 |

| Other (not specified) | 15 | 1.1 |

| Duration of travel (1372 respondents) | ||

| Less than 1 hour | 1065 | 77.6 |

| 1 to 2 hours | 233 | 17 |

| 2 to 3 hours | 45 | 3.2 |

| 3 to 4 hours | 18 | 1.3 |

| 4 to 5 hours | 4 | 0.3 |

| 5 to 6 hours | 4 | 0.3 |

| 6 to 7 hours | 2 | 0.2 |

| 7 to 8 hours | 0 | 0 |

| 8 hours or more | 1 | 0.1 |

| Number of persons within 3 feet proximity (1354 respondents) | ||

| 0 | 708 | 52.3 |

| 1 | 567 | 41.9 |

| 2 | 52 | 3.8 |

| 3 | 12 | 0.9 |

| 4 | 2 | 0.1 |

| 5 | 1 | 0.1 |

| 6 | 3 | 0.2 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 or more | 9 | 0.7 |

Table 7.

Lodginga

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Own home | 1256 | 84.4 |

| Relative's home | 142 | 9.3 |

| Motel or hotel | 72 | 4.7 |

| Boarding house | 3 | 0.2 |

| Nursing home | 1 | 0.1 |

| Other | 32 | 1.3 |

| Total | 1488 | 100 |

More than one answer was possible for this question.

Table 8.

Overall Compliance to Safety Instructions

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Complete | 1230 | 83.8 |

| Almost complete | 221 | 15.1 |

| Half | 11 | 0.8 |

| Almost none | 3 | 0.2 |

| None | 2 | 0.1 |

| Total | 1467 | 100 |

Discussion

The current report is an epidemiological study of patients who were administered 131I for the outpatient treatment of DTC in order to determine (i) the decision-making process for the location of treatment (i.e., inpatient versus outpatient); (ii) the radiation safety instructions given to the patients and the method of communication, (iii) the release time after the treatment and the conditions of the travel, (iv) the types of lodging, and (v) the perception of the patients' level of compliance to the radiation safety instructions.

Extensive previous discussions are available regarding regulations, guidelines, and controversies related to radiation safety after 131I therapies (1,3–18), and while it is not the intent of this study to address specific regulations or guidelines, we believe that the survey results raise several concerns. First, 45% (699/1541) reported that they had no discussion regarding the options of an inpatient or outpatient treatment. Second, insurance companies reportedly made that decision 5% (79/1541) of the time. Although we do not know what criteria the insurance companies based their decision on, this needs to be evaluated further. Third, although the great majority of patients received oral or written radiation safety instructions, a quarter of them reported receiving no oral or written instructions on how security agents could contact the treating team for verification of the individual's 131I treatment in case of setting off security alarms. Finally, 5% (76/1488) of patients resided in public lodging, and of those patients 30.2% (23/76) received at least 5.5 GBq (150 mCi) of radioiodine (Supplementary Table S7). Whether or not an individual should be allowed to reside in a hotel remains controversial (1,5,9,14). In fact, in 2011, the (NRC) issued a regulatory issue summary strongly discouraging the release of patients to a location other than a private residence (19). We would emphasize two additional concerns. We would submit that some, and perhaps many patients might not remain in their lodging room. Instead, they might go out to a public facility such as to eat, and the public facility will be oblivious of and not practicing any radiation precautions whatsoever from the radioactivity. Although a patient may not remain in his/her room at home and may go out to public facilities to eat, this would be less likely to occur when residing at home than in a hotel. Although again the potential exposure to housekeeping and other hotel staff is controversial, we submit that there is still a moral issue: Why an individual is concerned enough to avoid staying with his/her family members at home, but will go to a public lodging, with no concerns about its staff or other lodgers?

Several other surveys on radiation safety precautions have been published (6,7). The ATA survey targeted members from various medical associations (e.g., ATA, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, The Endocrine Society, American Association of Endocrine Surgeons, Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, and American Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology) (6). In the ATA study, physicians, nurse practitioners, and radiation safety officers responded—not patients—and the study did not distinguish between 131I prescribed activity for outpatient treatments versus inpatient treatments for DTC. Another survey was conducted by Katz et al. in collaboration with the U.S. NRC to examine how health care facilities informed patients regarding radiation alarm issue (7). This survey assessed individuals such as authorized users, physicians, technologists, and health physicists regarding their work experience, involvement in patient release, patient communication, familiarity with the NRC Information Notice, the process of making a decision on patient release, the process of patient education related to radiopharmaceutical administration including pre- and postadministration counseling, and verbal and written communications (7).

Decision-making regarding inpatient versus outpatient treatment

Katz et al. did not address factors that affected the decision regarding whether the patient was to be treated as an outpatient or inpatient (7). Greenlee et al. reported prescribed activity and social situations as factors potentially affecting the decision, with high prescribed activity encouraging inpatient treatment, but they did not further define the social situations (6). Greenlee et al. also reported that the insurance coverage influenced the decision of outpatient versus inpatient care in 17% of the respondents of the United States. This was higher than our response rate of 5.2% (Table 3), and again the criteria used by the insurance companies were not reported (6). Our numbers might have underestimated this issue because the process of obtaining authorization for procedures is not usually apparent to the patient.

In addition, there is frequently some discrepancy of patients' preference for inpatient 131I therapy versus the medical necessity determined by medical and radiation safety staff. This may explain why physicians made the decision in 75% (1162/1541) of the times.

Radiation safety instructions to the patients and the method of communication

For the use of oral and written instructions, Greenlee et al. reported that 66% of the respondents had given instructions that addressed hygiene and contact precautions, breastfeeding, avoidance of pregnancy, and side effects such as salivary glands effects and cancer risk (6), whereas our survey reported that a greater proportion of respondents received oral (97%; 1459/1504) and written (93%; 1351/1447) radiation safety instructions to reduce as low as is reasonably achievable radiation exposure from 131I to other individuals. In addition, most of the respondents signed a statement agreeing that they would comply with the instructions (Tables 4 and 5).

In regard to the individual responsible for providing radiation safety instructions, Greenlee et al. observed that various professionals were in charge of instructing the patients, which raises the potential for patient and staff confusion (6). Their questionnaire was not structured to evaluate who ultimately provided the safety instructions and what aspects of radiation safety each professional addressed. In the survey of Katz et al., the quality and utility of the written instructions provided to patients varied among the Nuclear Medicine facilities, and the authors suggested some standardization of basic instructions that are given to all released patients and emphasized the importance of using an appropriate and effective language to the patient (7). In our survey, we found that nuclear medicine physicians and staff provided oral and written instructions for the majority of the respondents, while a minority of them received either oral (24%; 354/1504) or written instructions (17%; 254/1462) from their endocrinologists (Tables 4 and 5). Our findings indicate that in the perception of the patient, the nuclear medicine staff is the main source of instructions. Further improvement is needed for both oral and written radiation safety instructions in the consistency, the delivery, and the clarity of instructions by one individual.

Release time after the treatment

This aspect was not addressed in the previous surveys. In our survey, 88.2% 1208/1370) of the respondents were released within 1 hour of the therapy (Table 6), of which 28% (335/1208) of patients received 150 mCi (5.5 GBq) or more of radioiodine (Supplementary Table S3).

Method of travel

Sisson et al. recommended that patients should travel alone after 131I therapy (4). Although we observed that 52% (708/1354) of respondents traveled alone after 131I therapy (Table 6), we did not determine what percentage of patients was prepared with thyroid hormone withdrawal. We speculate that a significant portion of the 52% were hypothyroid. Hennessey et al. raised concerns regarding the risks of driving while potentially impaired by the effects of hypothyroidism (13). In addition, Parthasarathy et al. emphasized that most patients cannot drive properly because of their hypothyroid status or their general medical condition (14). In regard to the use of public transportation, most authors agree that it should be avoided in the first 24 hours after 131I therapy (1,4,5,14,15). Only 0.4% (5/1373) of our respondents used public transportation (Table 6). However, it is noteworthy that one patient that was treated with 300–349 mCi was released immediately after the therapy and took a bus for 1–2 hours (Supplementary Tables S4 and S5).

Types of lodging

Location of lodging after 131I outpatient therapy was not addressed in the previous surveys. In our survey, 94% (1398/1488) of the respondents resided in private lodging, either their own homes or a relative's home (Table 7). Our survey was not structured to pursue details about home setting, such as number of bedrooms, bathrooms, family members in house, and others. However, given its importance for radiation safety to family members, we speculate that the home setting was considered in the decision making of outpatient versus inpatient treatment of 131I.

On the other hand, 5% (76/1488) of the respondents stayed in hotels, motels, or boarding houses. When we correlated the doses of 131I administered to types of lodging, we noticed that one patient who stayed in a boarding house received between 250–299 mCi (9.25–11.06 GBq). Remarkably, 22 out of 72 patients (30.5%) that resided in hotels received doses higher than 150 mCi (5.5 GBq), including one patient that received more than 350 mCi (11.1 Gbq) (Supplementary Table S7).

As noted earlier, the issue of patients treated with 131I residing in hotels remains controversial, and although our intent is not to discuss the pros and cons of allowing patients to stay in hotels, we believe further discussions are warranted, because a significant number of patients resided in hotels.

Level of compliance to radiation safety instructions

Neither Greenlee et al. (6) nor Katz et al. (7) addressed level of compliance. We observed that, for each given instruction, regardless of the number of days the patients were instructed, most of them were compliant and some were even over compliant to the instructions (SupplementaryTables S8–S12). Indeed, 1451 out of 1467 (98.9%) respondents considered their overall compliance with safety instructions complete or almost complete (Table 8).

The strengths of this survey are not only that this is the largest number of responses of any survey on this subject ever published, but also that all responses were reportedly from patients.

This survey study does, however, have several limitations. First, the survey depends on the respondents' recollection of events. Second, the respondents represent a select group of individuals who are members of Thyroid Cancer Survivors' Association, relatively computer savvy, and more likely to be knowledgeable, motivated, and compliant regarding their 131I therapy and radiation safety precautions. Third, the survey is less than complete because not all aspects of the patient radiation safety instructions, practices, etc. could be surveyed without the survey becoming too long, which in turn may have increased the incomplete rate. Fourth, the survey was performed several years ago. But we are unaware of any significant subsequent changes in regulations or other major initiatives that improved radiation safety practices, only a call for input by the NRC regarding various practices and radiation safety instructions, and a regulatory issue summary from NRC (19). Finally, even if there has been a change in radiation safety behavior, this study can potentially be a baseline for future comparisons.

Conclusions

We report a large epidemiological survey of selected radiation safety aspects for outpatient 131I treatments that was completed by patients with DTC.

We believe that this survey identifies several areas that warrant future evaluations, discussion, guidelines, and/or policies including: 1) discussions with patients regarding inpatient versus outpatient treatments, 2) assessment and documentation of the patient's personal situation regarding inpatient versus outpatient 131I treatment, 3) limitations on the insurance companies making the decision regarding whether the 131I treatment is performed as an inpatient or outpatient, 4) oral and written instructions and documents regarding radiation safety issues including but not limited to instructions and documents about the potential to set off security alarms and how a security agent can verify the patient's recent 131I therapy, 5) consistency of radiation safety instructions, and 6) further discussion on public lodging after 131I treatment. This large epidemiological study can be used as a baseline for evaluating future changes in radiation safety management.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was underwritten by generous grants from our grateful patients.

We thank Elizabeth Carter, from the AARP Public Policy Institute, Washington, DC, for helping to design the survey.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Zanzonico PB 2013 Release criteria and other radiation safety considerations for radionuclide therapy. In: Akatolun C, Goldsmith SJ (eds) Nuclear Medicine Therapy. Springer New York, pp 409–424 [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission [NRC] 10 CFR §35.75 Release of individuals containing unsealed byproduct material or implants containing byproduct material. Available online at: www.nrc.gov/reading-rm/doc-collections/cfr/part035/part035-0075.html (accessed September2017)

- 3.NRC 1997 Release of patients administered radioactive materials. Regulatory Guide 8.39. U.S. NRC, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Thyroid Association Taskforce on Radioiodine S, Sisson JC, Freitas J, McDougall IR, Dauer LT, Hurley JR, Brierley JD, Edinboro CH, Rosenthal D, Thomas MJ, Wexler JA, Asamoah E, Avram AM, Milas M, Greenlee C. 2011. Radiation safety in the treatment of patients with thyroid diseases by radioiodine 131I : practice recommendations of the American Thyroid Association. Thyroid 21:335–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silberstein EB, Alavi A, Balon HR, Clarke SE, Divgi C, Gelfand MJ, Goldsmith SJ, Jadvar H, Marcus CS, Martin WH, Parker JA, Royal HD, Sarkar SD, Stabin M, Waxman AD. 2012. The SNMMI practice guideline for therapy of thyroid disease with 131I 3.0. J Nucl Med 53:1633–1651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenlee C, Burmeister LA, Butler RS, Edinboro CH, Morrison SM, Milas M, American Thyroid Association Radiation Safety Precautions Survey Task F. 2011. Current safety practices relating to I-131 administration for diseases of the thyroid: a survey of physicians and allied practitioners. Thyroid 21:151–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katz L, Ansari A. 2007. Survey of patient release information on radiation and security checkpoints. J Nucl Med 48:14N, 16N, 18N [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kloos RT. 2011. Survey of radioiodine therapy safety practices highlights the need for user-friendly recommendations. Thyroid 21:97–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amdur RJ, Snyder G, Mazzaferri EL. 2005. Requirements for outpatient release following I-131 therapy. In: Amdur RJ, Mazzaferri EL (eds) Essentials of Thyroid Cancer Management. Springer, Boston, pp 177–182 [Google Scholar]

- 10.NRC 2008 Precautions to protect children who may come in contact with patients released after therapeutic administration of iodine-131. Regulatory Issue Summary 2008–11. USNRC, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siegel JA, Marcus CS, Stabin MG. 2007. Licensee over-reliance on conservatisms in NRC guidance regarding the release of patients treated with 131I. Health Phys 93:667–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siegel JA, Silberstein EB. 2008. A closer look at the latest NRC patient release guidance. J Nucl Med 49:17N–20N [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hennessey JV, Parker JA, Kennedy R, Garber JR. 2012. Comments regarding Practice Recommendations of the American Thyroid Association for radiation safety in the treatment of thyroid disease with radioiodine. Thyroid 22:336–337; author reply 337–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harolds JA. 2011. New scrutiny of outpatient therapy with I-131. Clin Nucl Med 36:206–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parthasarathy KL, Crawford ES. 2002. Treatment of thyroid carcinoma: emphasis on high-dose 131I outpatient therapy. J Nucl Med Technol 30:165–171; quiz 172–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grigsby PW, Siegel BA, Baker S, Eichling JO. 2000. Radiation exposure from outpatient radioactive iodine (131I) therapy for thyroid carcinoma. JAMA 283:2272–2274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Willegaignon J, Sapienza M, Ono C, Watanabe T, Guimaraes MI, Gutterres R, Marechal MH, Buchpiguel C. 2011. Outpatient radioiodine therapy for thyroid cancer: a safe nuclear medicine procedure. Clin Nucl Med 36:440–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.NCRP 2007 Management of radionuclide therapy patients Report 155. National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurement (NCRP), Bethesda, MD [Google Scholar]

- 19.NRC 2011 Policy on release of iodine-131 therapy patients under 10 CFR 35.75 to locations other than private residences. Regulatory Issue Summary 2011-01 USNRC, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.