Abstract

Interest in trauma-informed approaches has grown substantially. These approaches are characterized by integrating understanding of trauma throughout a program, organization, or system to enhance the quality, effectiveness, and delivery of services provided to individuals and groups. However, variation in definitions of trauma-informed approaches, coupled with underdeveloped research on measurement, pose challenges for evaluating the effectiveness of models designed to support a trauma-informed approach. This systematic review of peer-reviewed and grey literature identified 49 systems-based measures that were created to assess the extent to which relational, organizational, and community/system practices were trauma-informed. Measures were included if they assessed at least one component of a trauma-informed approach; were not screening or diagnostic instruments; were standardized; were relevant to practices addressing the psychological impacts of trauma; were printed in English; and were published between 1988 and 2018. Most (77.6%) measures assessed organizational-level staff and climate characteristics. There remain several challenges to this emerging field, including: inconsistently reported psychometric data; redundancy across measures; insufficient evidence of a link to stakeholder outcomes; and limited information about measurement development processes. We discuss these opportunities and challenges and their implications for future research and practice.

Keywords: trauma-informed, measurement, systematic review, families, organizations, systems

In the past several decades, the concept of a trauma-informed approach has gained momentum among scholars and practitioners in the fields of psychology, psychiatry, developmental science, education, public health, criminal justice, and social work (Champine, Matlin, Strambler, & Tebes, 2018a; Hanson & Lang, 2016; Donisch, Bray, & Gewirtz, 2016). This push has largely stemmed from the pioneering adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study (Felitti et al., 1998) and the growing body of related research demonstrating the harmful effects of childhood exposure to potentially traumatic events (PTEs; e.g., physical and sexual abuse, witnessed violence, household dysfunction) on health, behavioral health, education, employment, and criminal justice system involvement across the life span (Copeland et al., 2018). Although the link between PTEs and poor health outcomes is consistently documented (see review by Sowder, Knight, & Fishalow, 2018), terminology and components of trauma-related approaches and practices studied by researchers and used by practitioners are less clearly and consistently presented.

For instance, the terms trauma-informed practice, trauma-informed care, trauma-informed approach, and trauma-informed systems are used widely and often interchangeably to refer to the broad notion of a program, organization, or system that is intentionally designed to support children and families experiencing trauma; however, these terms are often not clearly or consistently operationalized (Hanson et al., 2018). Compounding this issue is the scarcity of research on measurement and evaluation of a trauma-informed approach, making it difficult to determine the effectiveness of trauma-informed initiatives and to make decisions about the optimal approaches to investing in such efforts (Becker-Blease, 2017; Hanson et al., 2018). More information is needed about the performance and characteristics of measures used in evaluations of trauma-informed work. Specifically, how can we best measure the extent to which a program, organization, agency, community, or system is truly trauma-informed and distinct from more traditional or universal practices? An important related question is whether trauma-informed programs, organizations, and systems yield more positive outcomes for children and families than those that are not trauma-informed (Hanson et al., 2018).

To address these questions, in this paper, we review systems-based measures of trauma-informed approaches. Our focus on measures of a system – a family, organization, community, or service system – aligns closely with one of the principles of community psychology, emphasizing systems change (Tebes, Thai, & Matlin, 2014). To date, most measures of trauma-informed approaches have emphasized individual assessments that seek to impact outcomes for individuals recovering from acute trauma. In addition, previous systematic reviews have focused on identifying and describing individual-level diagnostic and screening measures (Brewin, 2005; Choi & Graham-Bermann, 2018; Eklund et al., 2018). Although individual-level measures are essential, systems-based measures offer opportunities not only to assess whether systems are equipped to support individual-level changes in outcomes, but also whether they can support broader systems-level changes to support the health of communities (Matlin et al., 2019). Thus, our review of systems-based measures aims to supplement extant reviews of individual-level trauma measures and to help contribute to a more integrated understanding of multilevel issues related to measuring a trauma-informed approach.

Defining Trauma

In the past two decades, research on trauma-informed approaches has burgeoned across disciplines, culminating in a number of terms and definitions (Hanson & Lang, 2016). For instance, childhood adversity broadly refers to circumstances or events that may threaten or cause physical and/or psychological harm to young people (Bartlett & Sacks, 2019). Certain childhood adversities (e.g., school shootings, natural disasters) may increase the likelihood of trauma reactions in children (Bartlett & Sacks, 2019). In this paper, we use the definition of trauma presented by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) as an overarching term to refer to an event or series of events or circumstances experienced by individuals or groups that increases their risk for physical and/or psychological harm (2014). Trauma is widespread and affects nearly everyone; therefore, a diverse, multi-pronged risk prevention and health promotion approach is needed to address its potential effects (Bloom, 2016; Magruder, Kassam-Adams, Thoresen, & Olff, 2016; SAMHSA, 2014; Tebes, Champine, Matlin, & Strambler, 2019). According to SAMHSA’s (2014) widely used concept of a trauma-informed approach, a program, organization, or system is trauma-informed if it demonstrates a realization of the widespread impacts of trauma and potential pathways toward recovery; a recognition of the signs and symptoms of trauma in individuals and groups; a response that involves fully integrating knowledge about trauma into practices and policies; and efforts to prevent re-traumatization of individuals and groups.

Despite the widely accepted concept and general elements of a trauma-informed approach, scholars and practitioners operationalize the specific components in different ways. Here, we use the term “trauma-informed approach” for consistency to refer to efforts that are informed by knowledge of trauma and its potential wide-ranging and lifelong implications and that target risk and protective processes at multiple levels (individual, relational, organizational, and community/systems; Bloom, 2016; Magruder et al., 2016; Matlin et al., 2019; SAMHSA, 2014). This comprehensive and multilevel approach is essential for addressing the population health consequences of trauma (Tebes et al., 2019). Whereas individual-level practices primarily target individual attitudes and behaviors, relational practices often focus on improving family, peer, and interpersonal processes. In addition, organizational practices include interventions in various settings (such as schools and workplaces) and community/systems practices focus on serving whole communities as well as service systems (Magruder et al., 2016; Tebes et al., 2019). Thus, this framework prioritizes an array of interventions that operate across multiple levels within an individual’s broader ecology.

Identifying Core Components of Assessment

The growing interest in a trauma-informed approach has resulted in many different conceptualizations, definitions, and components. In response, Hanson and Lang (2016) conducted a comprehensive search of published literature, websites, and other resources to provide greater clarification on the core components of a trauma-informed approach based upon existing definitions and frameworks, including SAMHSA’s concept of a trauma-informed approach (2014). This search yielded 15 common components organized in three categories: 1. Workforce development (e.g. staff training, internal trauma champions, staff wellness); 2. Trauma-focused services (e.g. screening, access to trauma-focused interventions); and 3. Organizational environment and practices (e.g. policy change, collaboration, consumer engagement). Taken together, investment in these components may contribute to increased provider knowledge and awareness of trauma, facilitate identification of those affected by trauma, inform appropriate response strategies, and foster supportive organizational environments (Hanson et al., 2018).

Importance of measurement.

Important questions remain, however, about the measurement of a trauma-informed approach and its components, including how these components are assessed at the staff, program, organizational, and systems levels (Hanson & Lang, 2016). Organizations need psychometrically sound tools to measure the extent to which they are trauma-informed, to identify strengths and needs, and to monitor progress towards improvement. Systematic evaluations of the effectiveness of trauma-informed approaches are also needed; in particular, those that examine connections to youth and other stakeholder outcomes (Bailey, Klas, Cox, Bergmeier, & Avery, 2018; Hanson & Lang, 2016). Although prior reviews have been completed on individual-level trauma diagnostic and screening instruments (Brewin, 2005; Choi & Graham-Bermann, 2018; Eklund, Rossen, Koriakin, Chafouleas, & Resnick, 2018), there is no comprehensive review of measures of a trauma-informed approach for families, programs, organizations, systems, and communities.

Present Study

The purpose of this systematic review was to identify, review, and summarize all available systems-based measures of a trauma-informed approach, excluding those at the individual level (e.g., diagnostic and screening measures). A socio-ecological framework for a trauma-informed approach (Magruder et al., 2016; Matlin et al., 2019), as described earlier, was then used to organize the measures into socio-ecological levels (i.e., relational/family, organizational, and community/systems) and indicate which component(s) they assessed (Hanson & Lang, 2016). Measures were reviewed to identify additional characteristics, including the relevant contexts for their application (e.g. child welfare, behavioral health), psychometric properties, length, and cost/availability. This information will help to clarify the scope of existing measures of a trauma-informed approach, elucidate any gaps in this work, and inform future research and practice.

Method

Our protocol was informed by systematic review guidelines from the Campbell Collaboration (Kugley et al., 2016) and methods used by other researchers (i.e., Humphrey et al., 2011; Pistrang, Barker, & Humphreys, 2008; and Wolpert et al., 2009). We used Mendeley Reference Management software (www.mendeley.com) to manage citations generated by the review.

Inclusion Criteria

Measures were eligible for inclusion if they met all of the following six criteria: 1. Must assess at least one component of a trauma-informed approach (we used the components identified by Hanson & Lang, 2016 as a guide); 2. Is not a screening or diagnostic measure of trauma symptoms, including secondary traumatic stress; 3. Must be a standardized measure that generates a quantitative score; 4. Must be intended for assessment as part of a trauma-informed initiative or approach focused on addressing the psychological impacts of potentially traumatic events; 5. Must be printed in English; and 6. Must have been published between 1988 and 2018. These criteria were developed based on a thorough review and discussion among all of the authors. In regard to the first criterion, and as noted earlier, components of a trauma-informed approach (Hanson & Lang, 2016) included workforce development (e.g., trauma-related staff training, knowledge, and proficiency), the delivery of trauma-focused services (e.g., evidence-based practices and assessments), and organizational environment and practices (e.g., trauma-related interagency collaboration, environmental characteristics, and policies). We excluded measures from the review if they did not meet all of the inclusion criteria.

Search Strategy

From October to December 2018, the first and third authors conducted comprehensive reviews of the scholarly and grey literatures for measures meeting the inclusion criteria. The PsycINFO database was searched using 30 total combinations of key words that were informed by relevant literature: “trauma-informed” AND “approach” OR “care” OR “practice” OR “intervention” OR “system” AND “measure*” OR “question*” OR “survey” OR “checklist” OR “assessment” OR “evaluation.” Key words were searched via the Boolean/Phrase search mode in PsycINFO and included all publication types; the publication year range was 1988 to 2018. We focused on searching the PsycINFO database given that it is a comprehensive repository of interdisciplinary and peer-reviewed research and seemed the most likely to yield material relevant to psychological trauma.

Consistent with guidelines from the Campbell Collaboration (Kugley et al., 2016), Boolean logic and limiting commands were used in Google Advanced Search to review the grey literature using the following terms: “trauma-informed” AND “measure” OR “survey” OR “questionnaire” OR “checklist” OR “assessment” OR “evaluation.” At a minimum, the first five pages of results were reviewed. In addition, 52 specific websites were searched using the term “trauma-informed.” These sites were identified by the Campbell Collaboration (see Appendix II in Kugley et al., 2016) and also included relevant social science organizations that we identified (e.g., American Institutes for Research, the Child Welfare Information Gateway, the National Education Association, the Social Science Research Network, and SAMHSA). A snowballing approach (Wohlin, 2014) was used if the resource uncovered in the initial search included references or citations that informed subsequent searches. As part of our secondary search of measures, we also consulted with colleagues and other members of our professional network for information about any relevant, including unpublished, measures. Finally, we directly contacted measure developers for more information about their instruments, if needed.

Review and Coding Processes

Following completion of the searches, we used an adapted version of the parallel systematic review method described by Humphrey et al. (2011) to sort through the results in two phases. In the first phase, the first and third authors independently reviewed the same subset of abstracts to assess whether the inclusion criteria were met. Any abstracts that did not meet all of the inclusion criteria were filtered out. A Kappa statistic (McHurgh, 2012) was computed to assess the degree of interrater reliability and is reported in the Results section. When an adequate level of reliability was achieved (i.e., at least .60 to .79; McHugh, 2012), the two researchers divided and independently sorted the remaining abstracts according to whether they met the inclusion criteria.

In the second phase of the sorting process, the first author reviewed the full text of the remaining citations. The full text was reviewed to provide more context and ensure that the measure still met inclusion criteria. During this phase, measures judged to be ineligible for inclusion were filtered out.

Following completion of the sorting process, the first and third authors independently coded the same subset of measures using a data extraction form adapted from the Cochrane Collaboration’s Data Collection Form (https://training.cochrane.org/). The form was created to collect more detailed information about the measures and corresponding studies, where applicable, included in the review. The form captured the following information: citation details; the component(s) of a trauma-informed approach that the measure assessed; corresponding sample information (e.g., composition and size); context of the corresponding study, if applicable (e.g., child welfare, educational, health care); measure details (e.g., number of items, scales and subscales, sample items, response rubric, psychometric properties, cost, languages available, scoring guidelines, strengths and limitations); outcomes linked to measure, if applicable; and key references that cited the measure. Item-level interrater reliability (Orsi, Drury, & Mackert, 2014) was calculated based on the first and third authors’ responses on the forms and is presented in the Results section. When an adequate level of reliability was achieved, the first author completed the data extraction form for the remaining citations.

Results

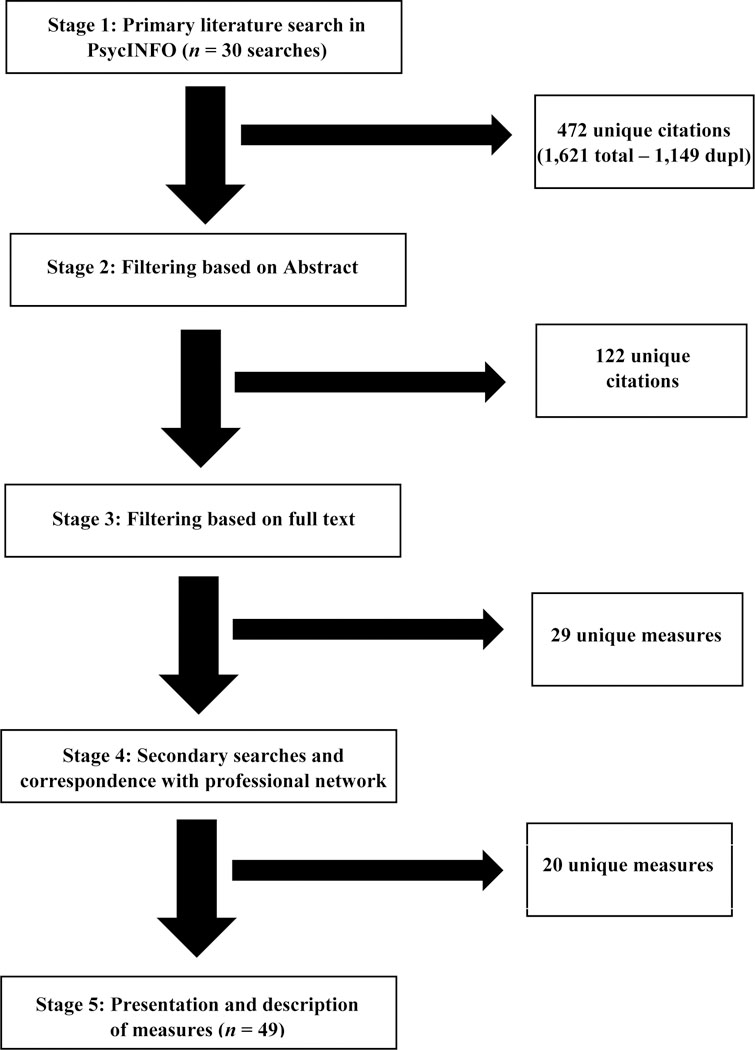

As shown in Figure 1, the initial 30 PsycINFO searches yielded 1,621 citations, 472 of which were unique. Abstract reviews resulted in 122 unique citations that met inclusion criteria. Most citations that were filtered out described measures of individual-level trauma symptoms, which were outside the scope of the present study. As noted earlier, previous reviews have summarized individual-level trauma diagnostic and screening measures (Brewin, 2005; Choi & Graham-Bermann, 2018; Eklund et al., 2018). During this phase of the sorting process, the first and third authors sorted an identical subset of abstracts (n = 60) and demonstrated strong interrater reliability (Kappa = .94). Of the 122 citations that met inclusion criteria based on their abstracts, review of the full texts yielded 29 unique measures that met inclusion criteria. Again, most of the citations that were filtered out described individual-level trauma diagnostic or screening instruments. In addition, the first and third authors filtered out guidelines and checklists that did not generate quantitative scores. Their review of the grey literature and other sources yielded 20 additional unique measures, culminating in a total of 49 unique measures. Finally, the first and third authors completed data extraction forms on an identical subset of citations (n = 22) and demonstrated adequate item-level interrater reliability (i.e., average percent total agreement was 74.5%). The reviewers discussed and resolved areas of discrepancy.

Figure 1.

Outline of steps in the review of the literature.

Table 1 summarizes information about the final list of 49 measures. As shown in Table 1, the measures are sorted according to socio-ecological level (i.e., relational, organizational, or community/systems; Matlin et al., 2019) and then alphabetically by author(s). Whereas 29 of the measures were described in peer-reviewed journal articles, 20 of the measures were described in dissertations, online documents, or on websites. The number of items included in the measures ranged from five to 87 items. In addition, at least one of the measures, the Attitudes Related to Trauma-Informed Care scale (ARTIC; Baker, Brown, Wilcox, Overstreet, & Arora, 2016), is available in versions that are adapted for human service providers and educators.

Table 1.

Summary of Measures Included in Review (n = 49)

| Socio- Ecological Level |

Measure and Citation | # of items | Example Item(s) | Context(s) | Components Assessed | Psychometric Data | Availability | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family | Educational | Child Welfare | Other Services | Health | Workforce Development** | Trauma-Focused Services | Org Env and Practices | ||||||

| Relational (n = 4) | Trauma Systems Therapy for Foster Care – Caregiver (Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2017) | 10 | “How much training have you had on child trauma?” | x | x | x | Not reported | Freely available online | |||||

| Trauma-Informed Practice Scales (Goodman et al., 2016; Sullivan et al., 2018)* | 20 | “I have the opportunity to learn how abuse and other difficulties affect responses in the body.” | x | x | x | x | x | Cronbach’s alpha = .85 – .98

across Agency, Information, Connection, Strengths, Inclusivity, and

Parenting Subscales Presented data from factor analysis |

Available upon request | ||||

| Resource Parent Knowledge and Beliefs Survey (Sullivan et al., 2016)* | 33 | “I understand how traumatic events can impact the way my child’s brain works.” | x | x | x | Cronbach’s alpha = .79 | Available upon request | ||||||

| Changes in trauma-informed parenting practices (Vanderzee et al., 2017)* | 8 | “I recognized when my child was experiencing something that might be traumatic.” | x | x | x | Not reported | Contact author(s) | ||||||

| Organizational (n = 38) | Supporting students affected by trauma (Alisic et al., 2012)* | 9 | “For me, with children like Janne and Joris, it is…know what is best for me to do to support them.” | x | x | Cronbach’s alpha =

.82 Presented data from factor analysis |

Freely available upon request | ||||||

| Psychosocial Care Survey -Knowledge about Pediatric Traumatic Stress (Alisic et al., 2016, 2017; Hoysted, Jobson, & Alisic, 2018)* | 7 | “Children at risk of posttraumatic stress present in the ED as…” | x | x | Cronbach’s alpha =

.86 Test-retest reliability = .75 |

Freely available upon request | |||||||

| Post-workshop survey for schools (Anderson, Blitz, & Saastamoinen, 2015)* | 11 | “Student disruptive behaviors may be linked to physical changes related to a stressful living environment.” | x | x | x | Not reported | Contact author(s) | ||||||

| Trauma Systems Therapy for Foster Care – Staff (Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2017) | 19 | “I have a clear understanding of what trauma-informed practice means in my professional role” and “A continuum of trauma-informed intervention is available for children served by my agency.” | x | x | x | Not reported | Freely available online | ||||||

| Teaching Rating Scale – Compassionate Schools Curriculum (Axelsen, 2017) | 12 | “I feel I have knowledge about the impact of trauma and environmental stressors on students’ performances.” | x | x | x | Not reported | Contact author(s) | ||||||

|

Attitudes Related to Trauma-Informed Care (ARTIC) Scale (Baker et al., 2016)* |

45-, 35-, and 10-item versions | “I am concerned that I do not/will not have enough support to implement the trauma-informed care approach” vs. “I think I do/will have enough support to implement the trauma-informed care approach.” | x | x | x | x | x | Cronbach’s alphas = .93 (ARTIC-45);

.91 (ARTIC-35); and .82 (ARTIC-10) Presented data from factor analysis |

Starts at $500 | ||||

| TICOMETER (Bassuk et al., 2017)* | 35 |

“Ongoing training on

trauma is required for all staff

and administrators (including clinical and non-clinical staff, peer support staff, and volunteers).” |

x | x | x | x | x | Cronbach’s alphas = .92 (overall

scale); .82 (Knowledge and Skills); .73 (Trusting Relationships); .86

(Respect); .86 (Service Delivery); and .78 (Procedures and

Policies) Presented data from factor analysis |

Starts at $250 | ||||

| Staff Behavior in the Milieu (Brown, Baker, & Wilcox, 2012; Brown & Wilcox, 2010)* | 12 |

“Staff talk with their

peers and supervisors about their strong positive and negative reactions to clients and doing this kind of work.” |

x | x | x | Cronbach’s alphas = .81 – .84 | Contact author(s) | ||||||

| Trauma-Informed Belief Measure (Brown, Baker, & Wilcox, 2012; Brown & Wilcox, 2010)* | 19 |

“The

clients I work with are generally doing the best they can at any particular time.” |

x | x | x | x | Cronbach’s alphas = .79 – .85 | Contact author(s) | |||||

| Current Practices in Trauma-Informed Care (Conners-Burrow et al., 2013)* | 12 |

“I talk to foster parents

about the trauma history of their potential foster children.” |

x | x | x | Cronbach’s alphas = .85 (Direct Support for Children) and .85 (Trauma-Informed Systems) | Contact author(s) | ||||||

| Trauma-Informed Knowledge Scale (Conners-Burrow et al., 2013)* | 12 | “I understand the meaning of child traumatic stress.” | x | x | Cronbach’s alpha = .94 | Contact author(s) | |||||||

| Trauma-Informed Understanding

Self-Assessment Tool (TRUST; Coordinated Care Services, Inc., 2018) (note: formerly known as the TIC-OSAT) |

46 | “There is a ‘trauma initiative’ in place aligned with the organization’s strategic plan (e.g., policy statement, workgroup, specialist).” | x | x | x | x | x | x | Cronbach’s alphas = .80 – .97 across the ten subscales | Free for any organization in New York State; otherwise, available for fee | |||

| Self-perceptions and use of ACEs (Counts et al., 2017)* | 10 | “I understand how early experiences influence the course of a person’s life.” | x | x | Not reported | Contact author(s) | |||||||

| Healthy Environments and Response to Trauma in Schools (HEARTS) Survey (Dorado et al., 2016)* | 9 | “My knowledge about trauma and its effects on children.” | x | x | Not reported | Contact author(s) | |||||||

| Creating Cultures of Trauma-Informed Care – Self-Assessment Scale and Fidelity Scale (Fallot & Harris, 2011, 2014) | 67; 16 | “The program creates ways to engage consumers as partners in plans for the recovery support services they need and want” and “The program routine recognizes all staff members’ strengths and skills in the planning, implementation, and evaluation of its services.” | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | Not reported | Contact author(s) | ||

| Understanding of trauma-informed practice and confidence in nursing skills (Hall, McKenna, Dearie, Maguire, Charleston, & Furness, 2016)* | 18 | “I am confident talking with patients about their traumatic experiences.” | x | x | Not reported | Contact author(s) | |||||||

| Creating Trauma-Informed Care Environments: Organizational Self-Assessment (Hummer & Dollard, 2010) | 25 | “Agency leadership and staff at all levels express commitment to implementing trauma-informed care.” | x | x | x | x | x | Not reported | Contact author(s) | ||||

| Trauma-Informed Care Questionnaire (Kenny et al., 2017)* | 18 |

“What are some

essential elements of trauma-informed care?” |

x | x | Test-retest reliability = .71 | Contact author(s) | |||||||

| Perceptions of Court Environment (Knoche, Summers, & Miller, 2018)* | 5 | “The courthouse is easy to navigate for the families.” | x | x | Cronbach’s alpha = .77 | Contact author(s) | |||||||

| Perceptions of Court Policy (Knoche et al., 2018)* | 5 | “It is the policy of my organization to regularly screen clients for trauma.” | x | x | Cronbach’s alpha = .77 | Contact author(s) | |||||||

| Perceptions of Court Practice (Knoche et al., 2018)* | 7 | “An understanding of the impact of trauma is incorporated into daily decision-making practice at my agency.” | x | x | Cronbach’s alpha = .80 | Contact author(s) | |||||||

| Understanding of Trauma Measure (Knoche et al., 2018)* | 11 | “Implementing trauma-informed practices will improve the well-being of children and families in my jurisdiction.” | x | x | x | Cronbach’s alpha = .86 | Contact author(s) | ||||||

| Practices in Trauma-Informed Care (Kramer et al., 2013)* | 13 |

“I expect that when staff

refer for mental health services, they make sure the therapist is trained in evidence-based trauma interventions.” |

x | x | x | Cronbach’s alphas = .88 (Trauma-Informed Practice) and .88 (Trauma Assessment) | Contact author(s) | ||||||

| Trauma-Informed Knowledge Scale (Kramer et al., 2013)* | 12 |

“I can identify at least

three ways in which the child welfare

system may increase a child’s trauma symptoms.” |

x | x | Cronbach’s alpha = .93 | Contact author(s) | |||||||

| Trauma Learning – Knowledge, Attitudes Toward, and Perceived Confidence in Trauma Inquiry and Response (Lotzin et al., 2018)* | 18 | “How confident do you feel to ask your clients about traumatic events?” | x | x | Cronbach’s alpha = .73 | Contact author(s) | |||||||

| Child Welfare Trauma-Informed Individual Assessment Tool (Madden et al., 2017)* | 17 |

“In my own case practice,

I am utilizing what I believe to be trauma-informed interactions with the children on my caseload.” |

x | x | x | Cronbach’s alpha =

.86 Presented data from factor analysis |

Contact author(s) | ||||||

| Trauma Knowledge Questionnaire (Marvin & Robinson, 2018)* | 12 | “Trauma only affects the person who lived through it.” | x | x | Not reported | Contact author(s) | |||||||

| Test Your Knowledge about Trauma-Informed Care/Ministry Quiz (Mills Kamara, 2017) | 25 |

“Traumatized

children/adults can be highly emotionally reactive or

sensitive” and “How often do

you/other leaders speak to your church in

sermons, teaching, seminars, or discussions about issues related to traumatic stress or trauma?” |

x | x | x | Not reported | Contact author(s) | ||||||

| Trauma-Informed Practices Self-Assessment (Multnomah County, Defending Childhood Oregon, 2016) | 46 | “In the past 30 days…I recognized ways in which ‘class disruptions’ or ‘behavior problems’ could be related to trauma” and “Staff shares with each other successful trauma-informed techniques.” | x | x | x | Not reported | Contact author(s) | ||||||

| Trauma-Informed Organizational Assessment (TIOA; The National Child Traumatic Stress Network, 2019) | 87 | “The organization ensures that children, youth, and families are connected with timely trauma assessment when the trauma screening indicates the need.” | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | Not reported | Contact

author(s) (note: measure is in development) |

||

| National Council Trauma-Informed Care Organizational Self-Assessment (National Council for Behavioral Health, 2014) | 34 | “The organization’s leadership communicates a clear and direct message that the organization is committed to creating a trauma-informed system of care…” | x | x | x | Not reported | Contact author(s) | ||||||

| Knowledge and confidence in working with clients affected by trauma (Palfrey et al., 2018)* | 5 |

“Level of confidence in

the assessment of trauma and adversity in your

clinical practice.” |

x | x | Not reported | Contact author(s) | |||||||

| Trauma knowledge, attitudes, and practices (Schiff et al., 2017)* | 28 | “How comfortable are you…asking families about previous traumatic experiences?” | x | x | Cronbach’s alphas = .81 (overall scale); .86 (Comfort); .86 (Trust and Confidence); and .60 (Attitudes) | Contact author(s) | |||||||

| Foundational Knowledge for Trauma-Informed Care Scale (Sundborg, 2017) | 30 |

“I know the principles of

trauma-informed care.” |

x | x | x | Cronbach’s alpha =

.96 Presented data from factor analysis |

Freely available online | ||||||

| Trauma-Informed Care in Youth Service Settings: Organizational Self-Assessment (Traumatic Stress Institute of Klingberg Family Centers, 2010) | 67 | “The organization has a ‘trauma-informed care initiative’ (e.g., workgroup/task force, trauma specialist) endorsed by and authorized by a chief administrator.” | x | x | x | x | Not reported | Freely available online | |||||

| Child Welfare Traumameter (Tullberg, 2019) | 56 | “Our supervisors and administrators identify when their staff are suffering from secondary trauma.” | x | x | x | x | Not reported | Contact

author(s) (note: measure is in development) |

|||||

| Trauma-Informed Medical Care Questionnaire (TIMCQ; Weiss et al., 2017)* | 8 | “Understand the prevalence of trauma in youth and families.” | x | x | Cronbach’s alphas = .71 (Attitude) and .91 (Confidence) | Contact author(s) | |||||||

| Standards of Practice for Trauma-Informed Care – Health Care Settings (Yatchmenoff, 2016) | 54 | “Agency is working with community partners and/or other systems to develop common trauma-informed protocols and procedures.” | x | x | x | x | Not reported | Contact author(s) | |||||

| Community/Systems (n = 7) | ACES and Resilience Collective Community Capacity (ARC) Survey (Hargreaves et al., 2016) | 53 |

“We have many strategic partnerships that work across sectors (such as education, health, juvenile justice, and social services).” |

x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | Cronbach’s alphas = .82 (Community

Cross-Sector Partnerships); .78 (Shared Goals); .76 (Leadership and

Infrastructure); .87 (Data Use for Improvement and Accountability); .81

(Communications); .76 (Community Problem-Solving Processes); .79

(Diverse Engagement and Empowerment); .84 (Focus on Equity); .85

(Multi-Level Strategies); and .79 (Scale of

Work) Presented data from factor analysis |

Contact author(s) |

| Trauma System Readiness Tool (Hendricks, Conradi, & Wilson, 2011) | 46 | “Child welfare staff members at all levels…understand their role in helping reduce the impact of trauma on children involved in the child welfare system.” | x | x | x | x | Not reported | Contact

author(s) (note: measure is no longer being supported by developer) |

|||||

| Trauma-Sensitive School Checklist (Lesley University and Trauma & Learning Policy Initiative, 2012) | 26 | “School develops and maintains ongoing partnerships with state human service agencies and with community-based agencies to facilitate access to resources.” | x | x | x | x | Not reported | Contact author(s) | |||||

| Trauma-Informed System Change Instrument (TISCI; Richardson et al., 2012)* | 19 | “There are structures in place to support consistent trauma informed responses to children and families across roles within the agency.” | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | Cronbach’s alphas = .37 (Policy);

.88 (Agency Practice); .85 (Integration); and .74

(Openness) Presented data from factor analysis |

Freely available online | ||

| System of Care Trauma-Informed Agency Assessment (TIAA; Thrive, 2011) | 42 | Not provided | x | x | x | x | x | x | Cronbach’s alphas = .84 – .88

(Physical and Emotional Safety); .83 – .92 (Youth Empowerment);

.82 – .90 (Family Empowerment); .87 – .89 (Trauma

Competence Subscale); .85 – .91 (Trustworthiness); .93

(Commitment to Trauma-Informed Approach); .91 (Cultural

Competence) Presented data from factor analysis |

Freely available

online (note: now owned by the State of Maine) |

|||

| Trauma Responsive Schools Implementation Assessment (TRS-IA; Treatment and Services Adaptation Center for Resilience, Hope and Wellness in Schools and the Center for School Mental Health, 2017) | 32 | “To what extent does your school/district have clearly defined discipline policies that are sensitive to students exposed to trauma?” | x | x | x | x | Not reported | Freely available online after completing registration | |||||

| Trauma Responsive Systems Implementation Advisor (TreSIA; EPower & Associates, 2011) | 50 | “We are committed to the long-term transformation (not a ‘program of the month’) to trauma-informed care and trauma-responsive systems.” | x | x | x | x | x | x | Not reported | Freely available online | |||

Published in peer-reviewed journal.

At the Relational level, the Workforce Development component refers to caregiver and other consumer attitudes, beliefs, and competencies.

Socio-Ecological Levels of Measurement

As shown in Table 1, four (8.2%) of the 49 measures focused on the relational level. These measures involved self-reports of the knowledge, attitudes, and skills of stakeholders, including caregivers of children, affected by trauma. For example, the Resource Parent Knowledge and Beliefs Survey (Sullivan, Murray, & Ake, 2016) measures caregivers’ knowledge of how trauma affects children and their beliefs about parenting a child affected by trauma. In comparison, 38 (77.6%) of the measures assessed the extent to which an organization (e.g., school, workplace, faith community) was trauma-informed. These measures involved self-reports by staff of training received, their use of trauma-focused services, and/or organizational practices and policies. For example, the TICOMETER (Bassuk, Unick, Paquette, & Richard, 2017) measures the extent to which health and human service organizations deliver trauma-informed care, as perceived by staff and reflected by staff knowledge and skills as well as broader policies and procedures. Finally, seven (14.3%) of the measures assessed the extent to which a community or system (e.g., whole community, city or town, or service system) was trauma-informed. These measures involved self-reports by staff of knowledge, attitudes, and skills of providers and/or aspects of the overall climate (e.g., cross-system collaboration). For example, the Trauma-Informed System Change Instrument (TISCI; Richardson, Coryn, Henry, Black-Pond, & Unrau, 2012) is a self-report measure completed by staff that assesses their perceptions of the extent to which the child welfare system in which they work is trauma-informed, as indexed by staff understandings of trauma and related competencies, as well as their views of broader policies and practices.

Applicable Contexts for Use of the Measures

Table 1 also shows that the largest proportion of measures (n = 17, 34.7%) applied to more than one context (e.g., family, educational, child welfare). In addition, nine (18.4%) were relevant to primarily child welfare contexts, eight (16.3%) to behavioral health/health contexts, seven (14.3%) to educational contexts, and eight (16.3%) to other service contexts, including court and correctional agencies, human service agencies, home visiting programs, and religious institutions. Authors of measures did not always identify the most applicable context(s) for use of their measure and, in those instances, we used consensus within the team to code the context that was most applicable for use with that measure. We gave consideration to information including an organization’s mission statement, services provided, and stakeholders (when identified or applicable), as well as to background literature reviewed in the Introduction section of publications (when applicable).

Trauma-Informed Components Assessed

At the relational level, of the four total measures, three (75.0%) assessed components of workforce development only. In other words, these measures focused on assessing stakeholders’ (e.g., caregivers’) understandings of the potential developmental impacts of trauma exposure and their trauma-informed competencies in their daily lives. In comparison, one measure (25.0%) assessed components of the workforce development, trauma-focused services, and organizational environment and practice components. This measure, known as the Trauma-Informed Practice Scales (Goodman et al., 2016), captures information about domestic violence survivors’, including caregivers’, trauma-related knowledge and competencies as well as their perceptions of the extent to which domestic violence program staff are skilled in responding to survivors’ feelings and coping skills and engage them as partners in service delivery.

Of the 38 total measures of the organizational level, 16 (42.1%) assessed components of workforce development only. For example, the Trauma-Informed Belief Measure (Brown, Baker, & Wilcox, 2012; Brown & Wilcox, 2010) assesses staff attitudes and beliefs toward trauma-informed care. Three measures (7.9%) assessed organizational and environment practices only. For example, the Perceptions of Court Policy Measure (Knoche, Summers, & Miller, 2018) assesses the extent to which court personnel perceive court policies (e.g., related to reducing staff burnout) to be trauma-informed within their organizations. Half of organizational-level measures (n = 19, 50.0%) assessed more than one component of a trauma-informed approach. For example, the ARTIC scale (Baker et al., 2016) consists of seven self-report subscales that assess the extent to which staff demonstrate knowledge of the underlying causes and potential developmental impacts of trauma exposure as well as perceive the overall climate of their agencies or organizations as supportive of a trauma-informed approach.

Finally, at the community/systems level, all seven of the measures (100.0%) assessed components of all three categories of a trauma-informed approach. For example, the Trauma-Informed System Change Instrument (TISCI; Richardson et al., 2012) consists of five self-report subscales that measure the extent to which staff understand the concept of trauma-informed practice, use trauma-informed safety plans and interventions for children in their care, and perceive their agency or organization as implementing formal policies and communications that are trauma-informed.

Additional Measure Characteristics

In addition to the measure information summarized in Table 1, we used a data extraction form to record a few additional details about the measures included in our review. Any data that were missing were either unavailable because they were not generated by the developers (as confirmed via personal communication), or we could not receive clarification from the measure developer. The majority of the 49 measures (91.8%) included a Likert-type scale as the response rubric. In addition, 26 (53.1%) of the measures included some psychometric data; of these, 15 (57.7%) presented Cronbach’s alpha coefficients only, one (3.8%) presented a test-retest reliability coefficient only, and 10 (38.5%) presented Cronbach’s alpha coefficients in conjunction with test-retest reliability coefficients or data from factor analyses. In regard to cost, nine of the measures were freely available online, whereas three had fees associated with their use, and the remainder appeared to be available upon request; further information about cost or use limitations was not available. A subset of the measures (i.e., 83.7%) was described within the context of validation or outcomes studies, with samples ranging from 18 to 1,592 participants; the remaining measures were described or presented in online documents or on websites.

Discussion

The purpose of this systematic review was to identify, review, and summarize all systems-based measures of a trauma-informed approach that were published within the scholarly or grey literatures in the previous 30 years. Each measure assessed at least one component of a trauma-informed approach (excluding diagnostic and screening instruments) and was relevant to practices addressing the psychological impacts of trauma. Interest in trauma-informed approaches has grown substantially in recent years and spanned multiple disciplines, raising questions about how these approaches are defined, implemented, and measured (Donisch et al., 2016; Hanson et al., 2018). Contemporary scholarship emphasizes the adoption of multilevel approaches that address the wide-ranging impacts of trauma on individuals, families and other groups, organizations, service systems, and communities (Bloom, 2016; Champine et al., 2018; Magruder et al., 2016; Tebes et al., 2019). In addition, research has further operationalized the concept of a trauma-informed approach according to measurable components (Hanson & Lang, 2016). We organized the 49 measures in our review according to socio-ecological level, applicable context, and components assessed.

Opportunities for Systems-Based Measurement of a Trauma-Informed Approach

Our review identified a number of measures that cover various levels, contexts, and components for the systems-based measurement of trauma-informed approaches. This is an important development as the field transitions from a clinical science to a population health science perspective to address potentially traumatic events (Tebes et al., 2019). A population health perspective considers how trauma exposure impacts the aggregated health status of groups of individuals and seeks as its focus the development and implementation of a range of interventions that can have an impact on trauma and its sequelae at a population level (Tebes et al., 2019). Prioritizing population health aligns closely with community psychology principles that emphasize systems change (Tebes et al., 2014) and the development of participatory approaches to address major public health challenges (Tebes & Thai, 2018). The development of systems-based measures of trauma-informed approaches is essential to population health (Tebes et al., 2019).

The measures reviewed in this study, which span 2010 through 2018, indicate that in recent years, the field has moved toward embracing comprehensive and systems-based approaches to trauma-informed work. This shift away from a sole emphasis on individual-level treatment toward more integrative policies and practices that engage families, schools, and whole communities and service systems offers exciting opportunities for future research. For instance, based on our review, there is a strong need to include more ethnically and racially diverse samples in this work to assess measurement invariance, or the extent to which an instrument measures the same construct across groups (Milfont & Fischer, 2010). For the measures we reviewed that were assessed as part of studies, the majority included samples that were primarily White or European American. A small subset of studies included ethnically and/or racially heterogeneous samples (e.g., Alisic et al., 2016, 2017; Anderson, Blitz, & Saastamoinen, 2015; Axelsen, 2017; Dorado et al., 2016). Implementing these measures with more diverse samples would help to elucidate whether groups ascribe the same meaning and importance to components of a trauma-informed approach and whether similarities and differences between groups can be meaningfully interpreted (Milfont & Fischer, 2010).

Challenges to Systems-Based Measurement of a Trauma-Informed Approach Many definitions, many measures.

In our review, we used the trauma-informed approach components identified by Hanson and Lang (2016) as a guide for organizing the measures we identified. However, there was variation in how measures operationalized the components, in part because of the divergence in how “trauma-informed” is being defined. For example, in our review, 41 measures indexed workforce development according to components such as demonstrated knowledge and understanding of trauma and the components of a trauma-informed approach (e.g., Alisic et al., 2016; Conners-Burrow et al., 2013; Marvin & Robinson, 2018; Sullivan et al., 2016); perceived self-efficacy (e.g., Baker et al., 2016; Sullivan et al., 2016); personal attitudes and beliefs about consumers and/or the adoption of a trauma-informed approach (e.g., Baker et al., 2016; Brown et al., 2012); skill development (e.g., Bassuk et al., 2017); and the availability of trauma training and education (e.g., Fallot & Harris, 2011). Thus, although “workforce development” was used to categorize the measures in our review, it is important to acknowledge the variation in how this component was indexed within and across measures.

There were also areas of considerable overlap across measures in the components that were assessed. Most of the workforce development measures included a scale that assessed respondent knowledge of trauma and its potential impacts that were not specific to an intervention or context, raising questions about the need for separate measures. Similarly, measures of organizational environment and practices commonly included scales that assessed system-wide support for trauma-informed approaches in the form of policies and collaborations. To eliminate redundancy and enhance efforts to connect interests in trauma-informed approaches across disciplines, it is recommended that we explore how to produce a more unified framework and set of components for measurement and evaluation. To build a more robust empirical base, future studies should incorporate previously validated measures, or adaptations of such measures, rather than create new measures without adequate justification.

“Teaching to the Test”

Many of the measures appeared to have been developed expressly to evaluate the impact of a specific intervention, rather than for the purposes of understanding a trauma-informed approach per se. This finding represents a challenge for how best to integrate data across studies when tailored measures may not be applicable across levels, contexts, and components. As discussed by Purtle (2018) in his review of evaluations of trauma-informed organizational interventions, there is the risk of finding “teaching to the test” effects. This bias occurs when a survey assesses components that are strongly emphasized in trainings or interventions (Purtle, 2018). In our review, we uncovered multiple measures that were developed to assess the impacts of trauma trainings, workshops, and interventions on participant knowledge, attitudes, and skills (e.g., Anderson, Blitz, & Saastamoinen, 2015; Palfrey et al., 2018; Vanderzee et al., 2017). Thus, it is questionable whether post-test increases in participant characteristics truly reflected gains in knowledge and skills or were linked to response bias associated with material emphasized in the program or intervention.

Insufficient Psychometric Data

The inconsistent reporting of psychometric data for trauma-informed approach measures is an important limitation of the research in this area. In our review, these data were not available for nearly half (46.9%) of the measures. These data are critical for assessing the quality and performance of measures and whether they are measuring the intended components. Of the measures that did have these data, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were primarily presented to index internal consistency reliability. However, other indices of validity (e.g., construct validity, face validity, content validity) and reliability (e.g., test-retest) are needed to assess the strengths of measures and study findings (DeVon et al., 2007).

Insufficient Descriptions of the Measurement Development Processes

Related to the issue of underreported psychometric data was the absence of information about the processes involved in developing many of the measures in our review. Whereas some researchers (including Baker et al., 2016; Goodman et al., 2016; Richardson et al., 2012) thoroughly described the theoretical and empirical bases for their measures and presented findings from exploratory factor analyses and psychometric evaluations, other resources simply described the measures as developed for the present study and provided no contextual information. This observation, again, raises questions about the need for developing new and invalidated instruments.

Of the studies we reviewed that did describe the processes involved in measure development, the findings were promising. For instance, Goodman et al. (2016) described in detail the steps involved in the item generation for the Trauma-Informed Practice Scales, including consultation of relevant scholarly work and pilot testing with ethnically and racially diverse focus groups. This work informed a subsequent validation study, which included administering the measure and running a series of exploratory factor analyses. In addition, they assessed construct validity using different techniques. This level of detail was not available for most of the measures included in our review.

Unclear Relevance to Stakeholder Outcomes

Another area that needs further attention is how measures are used to assess specific stakeholder outcomes. Specifically, how do we know whether being trauma-informed within the context of relationships, organizations, systems, and communities is linked to improved outcomes for individuals served? Most of the measures in our review were used to assess the impacts of trainings or programs with pre- and post-test assessments of participants’ trauma-related knowledge, attitudes, and skills. However, do those staff, program, or system improvements yield improvements in outcomes for those served? To date, we know very little about the relation of systems-based enhancements to meaningful outcomes for children and families. This observation is particularly important given that the presumption underlying the entire trauma-informed approach movement is that it can mitigate the significant and chronic negative behavioral health, health, and social outcomes associated with childhood trauma.

Understudied Socio-Ecological Levels, Components, and Contexts

Another key observation based on our findings is the scarcity of measures that currently assess trauma-informed approaches at the relational and systems/community levels. Over three-quarters of the measures in our review assessed self-report organizational-level characteristics. Although assessing trauma-informed approaches within organizations is essential, more attention needs to be directed toward other levels of intervention, consistent with a multilevel approach (Champine et al., 2018; Magruder et al., 2016; Matlin et al., 2019). Attention to a “diversity of contexts” (Trickett, 1996) is a critical consideration for community psychologists. Although there is a growing recognition of the need for additional systems-based measures of trauma-informed approaches, expansion of the contexts for measurement remains a significant challenge.

Specifically, there is a dearth of research on trauma-informed approaches for youth who are not school- or system-involved. What are the components of a trauma-informed approach in non-organizational or institutional settings outside of the home, and what are the implications for measurement? A small body of research has examined trauma-informed approaches in community youth programs. For example, Im et al. (2018) developed and evaluated a trauma-informed psychoeducation intervention for urban Somali refugee youth in Kenya. Using a pre-/post-test method, results indicated improved functioning among youth participants. The intervention consisted of modules that emphasized diverse psychosocial competencies, but these components were not directly measured or linked to youth functioning. In another study, Ferguson and Maccio (2015) examined the extent to which programs for sexual minority runaway and homeless youth incorporated a trauma-informed approach. As noted by the researchers, this population is at increased risk for experiencing traumatic stress and other health concerns; however, services that target this population are limited. In their review of programs, the researchers found that staff aimed to be trauma-informed in their exchanges with these youth (Ferguson & Maccio, 2015); however, more information is needed about the key components that comprise a trauma-informed approach within these particular program contexts.

In the present study, in regard to trauma-informed approach components, most measures included at least one scale relevant to workforce development (85.7%), whereas nearly half of measures addressed trauma-focused services (49.0%) and less than half addressed organizational environment and practices (46.9%). Of note, strategies for addressing secondary traumatic stress fall under the workforce category (Hanson & Lang, 2016), but were not explicitly targeted in this review in light of their emphasis on diagnosis and screening. A future systematic review could focus on measures of this component of a trauma-informed approach.

The largest proportions of measures in our review were relevant to child welfare contexts (44.9%), other social and human service settings (42.9%), and behavioral health and health care settings (38.8%). In comparison, there were fewer measures linked to educational (30.6%) and family (12.2%) contexts. These are key contexts in the lives of children and families exposed to trauma that should be studied in greater depth, and development of psychometrically sound measures of these systems is important for doing so.

Limitations

There were four primary limitations of our study. First, there may be unpublished measures of trauma-informed approaches that we were unable to access through scholarly and grey literature searches and correspondence with our professional network. Second, we limited our review to measures printed in English. Third, we were unable to collect detailed information on all of the measures in our review; some developers did not respond to requests for more information. Fourth, several systems-based measures assessed primarily individual perceptions of a program, organization, community, or service system. This finding raises the question of whether these perceptions truly represent a measure of a given “system” (e.g., family, organization, community) or a much narrower construct. We agree that this is a limitation, but one that applies to many types of “systems” assessment, whether they involve aggregated individual perceptions or draw on systematic community observations or social indicator data. What is critical is specifying the data sources and methods in the assessment of a given system, which reveal the potential limitations of generalizability and threats to validity (Tebes, Kaufman, & Connell, 2003).

Finally, although the present study focused on identifying and summarizing survey-based measures, qualitative approaches are also essential in measuring components of a trauma-informed approach and the processes through which these components may impact stakeholder outcomes. For instance, interviews and focus groups with stakeholders can shed light on the extent to which a trauma-informed approach adequately addresses multilevel risk and protective factors (Blitz, Anderson, & Saastamoinen, 2016; Perry & Daniels, 2016); these findings, in turn, can be used to inform quantitative measures.

Implications for Action

Findings from this review may help to inform future measurement-related decision-making in assessments and evaluations of programs, organizations, and systems that serve children and families affected by trauma. It is our hope that this review will aid readers who are interested in measuring the extent to which their program, agency, or system is trauma-informed by serving as a guide in identifying promising measures. In selecting measures, consideration should be given to factors including relevance to program context and sample, length of measure, cost of measure, and available language(s). In addition, it is essential that measures align with the methodological aims of a study (e.g., needs assessment, pre-/post-comparison, longitudinal outcomes study). We recommend that researchers and practitioners build upon, adapt, and study previously developed measures, when feasible; avoid developing new measures intended only to evaluate a specific program (i.e., teaching to the test; Purtle, 2018); or use a rigorous measure development process to develop a new measure. As noted earlier, researchers should also explore opportunities to implement measures with ethnically and racially diverse samples to assess whether these measures can be used to make valid comparisons among groups (Milfont & Fischer, 2010).

Conclusions

Interest among scholars and practitioners in trauma-informed approaches shows no sign of waning. To date, research in this area has yielded a multitude of definitions and measures that encompass an array of individual-, group-, organization-, and systems-level characteristics and processes. We encourage readers to thoughtfully reflect on this work; specifically, as it relates to measurement and evaluation and the question of whether and how scores on measures correspond to improvements in child and family functioning. Our review identified 49 systems-based measures developed to assess trauma-informed approaches at the relational, organizational, and community/systems levels. These measures vary in quality and strength and raise important questions for future study. Rigorous and psychometrically valid and reliable measures of trauma-informed approaches at multiple levels of intervention will enhance understanding of how initiatives may advance population health.

Highlights:

First comprehensive review of systems measures of a trauma-informed approach.

Identified 49 systems measures based on review of scholarly and grey literatures.

Measures assessed relational, organizational, and community/system practices.

Most measures assessed organizational-level staff and climate characteristics.

More work is needed to measure psychometric properties and to establish a link to stakeholder outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Compliance with Ethical Standards:

The authors of this manuscript have complied with APA ethical principles in their treatment of individuals participating in the research, program, or policy described in the manuscript. Since the research did not involve collection of data from human subjects, it did not need to be approved by an organizational unit responsible for the protection of human participants.

Funding: This study was funded, in part, by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (T32DA019426).

This work was supported, in part, by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (T32DA019426).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alisic E, Bus M, Dulack W, Pennings L, & Splinter J (2012). Teachers’ experiences supporting children after traumatic exposure. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 25, 98–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alisic E, Hoysted C, Kassam-Adams N, Landolt MA, Curtis S, Kharbanda AB, … Babl FE (2016). Psychosocial care for injured children: Worldwide survey among hospital emergency department staff. The Journal of Pediatrics, 170, 227–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alisic E, Tyler MP, Giummarra MJ, Kassam-Adams R, Gouweloos J, Landolt MA, & Kassam-Adams N (2017). Trauma-informed care for children in the ambulance: International survey among pre-hospital providers. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson EM, Blitz LV, & Saastamoinen M (2015). Exploring a school-university model for professional development with classroom staff: Teaching trauma-informed approaches. School Community Journal, 25(2), 113–134. [Google Scholar]

- Axelsen KT (2017). Developing compassionate schools and trauma-informed school-based services: An expanded needs assessment and preliminary pilot study. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest. (10757813) [Google Scholar]

- Baker CN, Brown SM, Wilcox PD, Overstreet S, & Arora P (2016). Development and psychometric evaluation of the Attitudes Related to Trauma-Informed Care (ARTIC) Scale. School Mental Health, 8, 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey C, Klas A, Cox R, Bergmeier H, & Avery J (2018). Systematic review of organisation-wide, trauma-informed care models in out-of-home care (OoHC) settings. Health and Social Care in the Community, 1–13. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett JD, & Sacks V (2019). Adverse childhood experiences are different than child trauma, and it’s critical to understand why. Child Trends. Retrieved from https://www.childtrends.org/adverse-childhood-experiences-different-than-child-trauma-critical-to-understand-why [Google Scholar]

- Bassuk EL, Unick GJ, Paquette K, & Richard MK (2017). Developing an instrument to measure organizational trauma-informed care in human services: The TICOMETER. Psychology of Violence, 7(1), 150–157. [Google Scholar]

- Becker-Blease KA (2017). As the world becomes trauma-informed, work to do. (2017). Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 18(2), 131–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blitz LV, Anderson EM, & Saastamoinen M (2016). Assessing perceptions of culture and trauma in an elementary school: Informing a model for culturally responsive trauma-informed schools. The Urban Review, 48(4), 520–542. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom SL (2016). Advancing a national cradle-to-grave-to-cradle public health agenda. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 17(4), 383–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR (2005). Systematic review of screening instruments for adults at risk of PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 18(1), 53–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SM, Baker CN, & Wilcox P (2012). Risking connection on trauma training: A pathway toward trauma-informed care in child congregate care settings. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 4(5), 507–515. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SM, & Wilcox P (2010, April). From resistance to enthusiasm: Implementing trauma-informed care. Paper presented at Massachusetts Department of Mental Health Grand Rounds, Worcester, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Champine RB, Matlin S, Strambler MJ, & Tebes JK (2018). Trauma-informed family practices: Toward integrated and evidence-based approaches. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(9), 2732–2743. [Google Scholar]

- Choi KR, & Graham-Bermann SA (2018). Developmental considerations for assessment of trauma symptoms in preschoolers: A review of measures and diagnoses. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(11), 3427–3439. [Google Scholar]

- Conners-Burrow NA, Kramer TL, Sigel BA, Helpenstill K, Sievers C, & McKelvey L (2013). Trauma-informed care training in a child welfare system: Moving it to the front line. Children and Youth Services Review, 35, 1830–1835. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland WE, Shanahan L, Hinesley J, Chan RF, Aberg KA, Fairbank JA, …Costello EJ (2018). Association of childhood trauma exposure with adult psychiatric disorders and functional outcomes. JAMA Network Open, 1(7), e184493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Counts JM, Gillam RJ, Perico S, & Eggers KL (2017). Lemonade for Life: A pilot study of a hope-infused, trauma-informed approach to help families understand their past and focus on the future. Children and Youth Services, 79, 228–234. [Google Scholar]

- Data collection form. (no date). The Cochrane Collaboration. Retrieved from https://training.cochrane.org/sites/training.cochrane.org/files/public/uploads/resources/downloadable_resources/English/Collecting%20data%20%20form%20for%20RCTs%20only.doc.

- DeVon HA, Block ME, Moyle-Wright P, Ernst DM, Hayden SJ, Lazzara DJ, … Kostas-Polston E (2007). A psychometric toolbox for testing validity and reliability. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 155–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donisch K, Bray C, & Gewirtz A (2016). Child welfare, juvenile justice, mental health, and education providers’ conceptualizations of trauma-informed practice. Child Maltreatment, 21(2), 125–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorado JS, Martinez M, McArthur LE, & Leibovitz T (2016). Healthy Environments and Response to Trauma in Schools (HEARTS): A whole-school, multi-level, prevention and intervention program for creating trauma-informed, safe, and supportive schools. School Mental Health, 8, 163–176. [Google Scholar]

- Eklund K, Rossen E, Koriakin T, Chafouleas SM, & Resnick C (2018). A systematic review of trauma screening measures for children and adolescents. School Psychology Quarterly, 33(1), 30–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallot RD, & Harris M (2011). Creating Cultures of Trauma-Informed Care: Program Self-Assessment Scale. Community Connections. [Google Scholar]

- Fallot RD, & Harris M (2014). Creating Cultures of Trauma-Informed Care: Program Fidelity Scale. Community Connections. [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, …Marks JS (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson KM, & Maccio EM (2015). Promising programs for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning runaway and homeless youth. Journal of Social Service Research, 41, 659–683. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman LA, Sullivan CM, Serrata J, Perilla J, Wilson JM, Fauci JE, & DiGiovanni CD (2016). Development and validation of the Trauma-Informed Practice Scales. Journal of Community Psychology, 44(6), 747–764. [Google Scholar]

- Hall A, McKenna B, Dearie V, Maguire T, Charleston R, & Furness T (2016). Educating emergency department nurses about trauma informed care for people presenting with mental health crisis: A pilot study. BMC Nursing, 15(21). doi: 10.1186/s12912-016-0141-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson RF, & Lang J (2016). A critical look at trauma-informed care among agencies and systems serving maltreated youth and their families. Child Maltreatment, 21(2): 95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson RF, Lang JM, Fraser JG, Agosti JR, Ake GS, Donisch KM, & Gewirtz AH (2018). Trauma-informed care: Definitions and statewide initiatives In Klika JB & Conte JR (Eds.), The APSAC handbook on child maltreatment (4th ed., pp. 272–291). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves MB, Verbitsky-Savitz N, Coffee-Borden B, Perreras L, Pecora PJ, Roller White C, …Adams K (2016). Advancing the measurement of collective community capacity to address adverse childhood experiences and resilience. Gaithersburg, MD: Community Science. [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks A, Conradi L, & Wilson C (2011). Creating trauma-informed child welfare systems using a community assessment process. Child Welfare, 90(6), 187–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoysted C, Jobson L, & Alisic E (2018). A pilot randomized controlled trial evaluating a web-based training program on pediatric medical traumatic stress and trauma-informed care for emergency department staff. Psychological Services. doi: 10.1037/ser0000247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummer V, & Dollard N (2010). Creating trauma-informed care environments: An organizational self-assessment. (part of Creating Trauma-Informed Care Environments curriculum). Tampa, FL: University of South Florida, Department of Child & Family Studies within the College of Behavioral and Community Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey N, Kalambouka A, Wigelsworth M, Lendrum A, Deighton J, & Wolpert M (2011). Measures of social and emotional skills for children and young people: A systematic review. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 71(4), 617–637. [Google Scholar]

- Im H, Jettner JF, Warsame AH, Isse MM, Khoury D, & Ross AI (2018). Trauma-informed psychoeducation for Somali refugee youth in urban Kenya: Effects on PTSD and psychosocial outcomes. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 11, 431–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny MC, Vazquez A, Long H, & Thompson D (2017). Implementation and program evaluation of trauma-informed care training across state child advocacy centers: An exploratory study. Children and Youth Services Review, 73, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Knoche VA, Summers A, & Miller MK (2018). Trauma-informed: Dependency court personnel’s understanding of trauma and perceptions of court policies, practices, and environment. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 11, 495–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer TL, Sigel BA, Conners-Burrow NA, Savary PE, & Tempel A (2013). A statewide introduction of trauma-informed care in a child welfare system. Children and Youth Services Review, 35, 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kugley S, Wade A, Thomas J, Mahood Q, Jørgensen A, Hammerstrøm K, & Sathe N (2016). Searching for studies: A guide to information retrieval for Campbell systematic reviews. Oslo, Norway: The Campbell Collaboration. [Google Scholar]

- Lotzin A, Sehner S, Martens M, Read J, Schäfer I, Buth S, …Härter M (2018). “Learning how to ask”: Effectiveness of a training for trauma inquiry and response in substance use disorder healthcare professionals. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 10(2), 229–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden EE, Scannapieco M, Killian MO, & Adorno G (2017). Exploratory factor analysis and reliability of the Child Welfare Trauma-Informed Individual Assessment Tool. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 11(1), 58–72. [Google Scholar]

- Magruder KM, Kassam-Adams N, Thoresen S, & Olff M (2016). Prevention and public health approaches to trauma: A rationale and a call to action. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 18(7). doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v7.29715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marvin AF, & Robinson RV (2018). Implementing trauma-informed care at a non-profit human service agency in Alaska: Assessing knowledge, attitudes, and readiness for change. Journal of Evidence-Informed Social Work, 15(5), 550–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matlin SL, Champine RB, Strambler MS, O’Brien C, Hoffman E, Whitson M, & Tebes JK (2019). A community’s response to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs): Building a resilient, trauma-informed community. American Journal of Community Psychology, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh ML (2012). Interrater reliability: The Kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica, 22(3), 276–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendeley – Reference Management Software & Researcher Network. (2018). Retrieved from: https://www.mendeley.com/?interaction_required=true

- Milfont TL, & Fischer R (2010). Testing measurement invariance across groups: Applications in cross-cultural research. International Journal of Psychological Research, 3(1), 111–121. [Google Scholar]

- Mills Kamara CV (2017). Do no harm: Trauma-informed lens for trauma-informed ministry: A study of the impact of the helping churches in trauma awareness workshop (HCTAW) on trauma awareness among predominantly African- and Caribbean-American leaders in Church of God 7th Day churches in the Bronx and Brooklyn, New York. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest. (10275904) [Google Scholar]

- Organizational Self-Assessment: Adoption of trauma-informed care practice. National Council for Behavioral Health. Retrieved from: https://www.nationalcouncildocs.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/OSA-FINAL_2.pdf

- Orsi R, Drury IJ, & Mackert MJ (2014). Reliable and valid: A procedure for establishing item-level interrater reliability for child maltreatment risk and safety assessments. Children and Youth Services Review, 43, 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Palfrey N, Reay RE, Aplin V, Cubis JC, McAndrew V, Riordan DM, & Raphael B (2018). Achieving service change through the implementation of a trauma-informed care training program within a mental health service. Community Mental Health Journal. doi: 10.1007/s10597-018-0272-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry DL, & Daniels ML (2016). Implementing trauma-informed practices in the school setting: A pilot study. School Mental Health, 8(1), 177–188. [Google Scholar]

- Pistrang N, Barker C, & Humphreys K (2008). Mutual help groups for mental health problems: A review of effectiveness studies. American Journal of Community Psychology, 42, 110–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purtle J (2018). Systematic review of evaluations of trauma-informed organizational interventions that include staff trainings. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 1–16. doi: 10.1177/1524838018791304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson MM, Coryn CLS, Henry J, Black-Pond C, & Unrau Y (2012). Development and evaluation of the Trauma-Informed System Change Instrument: Factorial validity and implications for use. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 29(3), 167–184. [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. (2014). Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Retrieved from: https://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content/SMA14-4884/SMA14-4884.pdf

- Schiff DM, Zuckerman B, Wachman EM, & Bair-Merritt M (2017). Trainees’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards caring for the substance-exposed mother-infant dyad. Substance Abuse, 38(4), 414–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowder KL, Knight LA, & Fishalow J (2018). Trauma exposure and health: A review of outcomes and pathways. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment, & Trauma, 27(10), 1041–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan CM, Goodman LA, Virden T, Strom J, & Ramirez R (2018). Evaluation of the effects of receiving trauma-informed practices on domestic violence shelter residents. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 88(5), 563–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan KM, Murray KJ, & Ake GS (2016). Trauma-informed care for children in the child welfare system: An initial evaluation of a trauma-informed parenting workshop. Child Maltreatment, 21(2), 147–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundborg SA (2017). Foundational knowledge and other predictors of commitment to trauma-informed care. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from Portland State University PDXScholar. (3625). [Google Scholar]

- Survey and feedback materials for TST-FC. (2017). The Annie E. Casey Foundation. Retrieved from: https://www.aecf.org/resources/survey-and-feedback-materials-for-tst-fc/

- System of Care Trauma-Informed Agency Assessment (TIAA) overview. THRIVE. Retrieved from: http://thriveinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Copy-of-TIAA-Manual-7-9-12-FINAL.pdf

- Tebes JK, Champine RB, Matlin SL, & Strambler MS (2019). Population health and trauma-informed practice: Implications for programs, systems, and policies. American Journal of Community Psychology, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tebes JK, Kaufman JS, & Connell CM (2003). The evaluation of prevention and health promotion programs In Gullotta T & Bloom M (Eds.), The encyclopedia of primary prevention and health promotion (pp. 46–63). New York: Kluwer/Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Tebes JK, & Thai NG (2018). Interdisciplinary team science and the public: Steps towards a participatory team science. American Psychologist, 73(4), 549–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]