Abstract

Objective: Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) show atypical attention. Mindfulness-based programs (MBPs), with self-regulation of attention as a basic component, could benefit these children. Method: We investigated how 49 children with ASD differed from 51 typically developing (TD) children in their attention systems; and whether their attention systems were improved by an MBP for children and their parents (MYmind), using a cognitive measure of attention, the Attention Network Test. Results: Children with ASD did not differ from TD children in the speed of the attention systems, but were somewhat less accurate in their orienting and executive attention. Also, MYmind did not significantly improve attention, although trend effects indicated improved orienting and executive attention. Robustness checks supported these improvements. Conclusion: Trend effects of the MBP on the attention systems of children with ASD were revealed, as well as minor differences between children with ASD and TD children in their attention systems.

Keywords: autism spectrum disorder, attention, attention network test, mindfulness, mindfulness-based program

Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are characterized by social interaction problems and restrictive behavior patterns or interests (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). Impaired cognitive functions are theorized to underlie the ASD symptoms, such as a weak central coherence (Happé & Frith, 2006), difficulties in executive functioning (Hill, 2004), and problems in theory of mind, the ability to infer mental states (Baron-Cohen, 2000). In addition, children with ASD show alternations in attention, including impaired disengagement and orienting of attention, overly focused and narrow attention, and a decreased ability to filter distractors (e.g., Allen & Courchesne, 2001; Keehn, Nair, Lincoln, Townsend, & Müller, 2016; Landry & Parker, 2013). Besides, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the most common comorbid disorders, with rates estimated to be 22.5 % up to 91.8 % (van Steensel, Bögels, & de Bruin, 2013).

Several scholars argue that atypical attention of children with ASD plays an important role in the development of the cognitive and behavioral impairments in ASD (Allen & Courchesne, 2001; Keehn, Müller, & Townsend, 2013). Attention impairments could lead to weak central coherency. Children could remain focused on local features of an object because of difficulties in shifting their attention away from it (Keehn et al., 2013). Overly focused attention hampers perceiving and integrating complex stimuli and perceiving relations between stimuli, thus, weakening central coherency (Allen & Courchesne, 2001). Attention is crucial for developing higher level executive functioning. Also, impaired disengagement may result in atypical arousal levels, and thereby arousal regulation taxes executive functioning resources (Keehn et al., 2013). Atypical arousal levels could in turn lead to reduced attention to social information to reduce overarousal (Keehn et al., 2013). Also, impaired orienting attention could result in impaired joint attention, which is important for the development of theory of mind and social development (Allen & Courchesne, 2001; Keehn et al., 2013).

Posner and Petersen (1990) provided a useful framework for investigating attention. This framework conceptualizes attention as operating through different networks of anatomical brain areas, and each network represents a different set of cognitive processes of attention. These cognitive processes can be divided in three functionally independent attention systems: the alerting, orienting, and executive system. Alerting attention refers to producing and maintaining a state of optimal vigilance to process high priority signals. When alertness is high, selecting a response occurs more quickly. Orienting attention refers to the ability to attend to sensory input from a specific modality or location, which includes disengaging from one stimulus, shifting, and reengaging to a new stimulus. Executive attention refers to top-down regulation of attention and is responsible for monitoring and resolving conflict (Keehn et al., 2013; Petersen & Posner, 2012; Posner & Petersen, 1990). The Attention Network Test (ANT) was developed and has been widely used to examine these attention systems (Fan, McCandliss, Sommer, Raz, & Posner, 2002; Rueda et al., 2004).

By applying this framework to the extant literature on attention in ASD, Keehn and colleagues (2013) concluded that results indicate a weaker orienting attention and executive attention. Results on alerting attention are inconsistent; no conclusion could be made whether this system is intact or dysfunctioning in ASD (Keehn et al., 2013). Several studies in ASD used the ANT to examine attention. A study in 20 adults with ASD, compared to 20 adults without ASD, did not find differences in orienting attention, but did find increased error rates indicative of a weaker alerting and executive attention. This was associated with abnormal brain activity (Fan et al., 2012). Another study found a weaker orienting attention for 20 children with ASD compared to 20 typically developing (TD) children, but their alerting and executive attention did not differ (Keehn, Lincoln, Müller, & Townsend, 2010). However, weaker executive attention correlated with a lower IQ in children with ASD, and a weaker alerting attention correlated with a higher social impairment. A third study also found a weaker orienting and executive attention in 14 children with ASD compared to 52 TD children, while no differences were found for alerting attention (Mutreja, Craig, & O’Boyle, 2016). Together, these studies suggest that children with ASD show deficits in orienting and executive attention, while results on alerting attention remain inconclusive.

According to theoretical and empirical studies, attentional functioning could be improved by training mindfulness (Bishop et al., 2004; Hölzel et al., 2011; Lutz, Slagter, Dunne, & Davidson, 2008). Mindfulness-based programs (MBPs) train participants to pay attention to the present moment, including emotions, thoughts, bodily sensations, and action tendencies, with a nonjudgmental and curious attitude (Kabat-Zinn, 1994). This present-moment awareness is practiced with meditations and applied during daily life. Self-regulation of attention forms an elementary component of mindfulness (Bishop et al., 2004; Hölzel et al., 2011; Lutz et al., 2008). Alerting attention could be enhanced, because focused and sustained attention is trained by focusing on a specific object of attention, such as the breath, and to be open to and notice experiences that arise in the present moment, such as thoughts and sounds (Bishop et al., 2004; Lutz et al., 2008). Orienting attention could be enhanced, because participants train to switch attention back to the focus of attention, and thereby to disengage, switch, and reengage attention (Bishop et al., 2004; Lutz et al., 2008). Also, in several meditation practices used in MBPs the object of attention is changing, which could enhance the orienting system as well. Executive attention could be enhanced, because participants train to control the focus of attention and to inhibit tendencies to react to distractions or engage in elaborative processing of thoughts, feelings, and sensations that arise in the present moment (Bishop et al., 2004; Hölzel et al., 2011).

So far, a few studies investigated the effects of MBPs for children with ASD, indicating improvements in children’s social responsiveness, and their emotional, behavioral, and attention problems (de Bruin, Blom, Smit, van Steensel, & Bögels, 2015; Hwang, Kearney, Klieve, Lang, & Roberts, 2015; Ridderinkhof, de Bruin, Blom, & Bögels, 2018; Singh, Lancioni, Manikam, et al., 2011; Singh, Lancioni, Singh, et al., 2011). However, these promising results are based on self-reports and parent reports. As children and parents invest time and effort in MBPs, they might overemphasize beneficial effects. Also, specifically in MBPs participants train to be more aware of their thought, emotions, and attention disruptions, which could influence their self-reports by reporting more difficulties after the MBP (Davidson & Kaszniak, 2015). Using an objective assessment of attention is, therefore, of additive value. In addition, investigating the effects on objectively measured attention could provide insight into the working mechanisms of MBPs.

In a study that investigated the effect of mindfulness on the attention systems, 80 healthy adults were randomly assigned to either 5 days of 20 min mindfulness meditation training or 5 days of 20 min relaxation training (Tang et al., 2007). No differences were found on alerting and orienting attention, but the mindfulness group showed improved executive attention (Tang et al., 2007). In 18 adults and 7 adolescents with ADHD of 15 years and older, Zylowska and colleagues (2008) also found an improved executive attention after an 8-week MBP, while alerting and orienting attention did not change. In line, another study showed more efficient executive attention for experienced meditators compared to nonmeditators (Jha, Krompinger, & Baime, 2007). Also, they found improved alerting attention for experienced meditators after a 1-month mindfulness retreat compared to the nonmeditators. Furthermore, after an 8-week mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) course the adults (n = 17) had an improved orienting attention compared to the experienced meditators and a control group (n = 17), while no differences in executive attention were found.

Some studies investigated the effects of mindfulness on the attention systems in children. In a quasiexperimental design 76 adolescents (13-15 years) who received daily concentrative meditation training as part of their regular school curriculum were compared to 70 adolescents who did not receive any mindfulness training (Baijal, Jha, Kiyonaga, Singh, & Srinivasan, 2011). The meditation group showed more efficient alerting and executive attention. No differences in orienting attention were found. Another study randomized 41 children (9-12 years) to either an 8-week mindfulness family stress reduction training or a waitlist control group (Felver, Tipsord, Morris, Racer, & Dishion, 2017). Both groups showed an improved executive attention at posttest, but this improvement in executive attention was larger for the mindfulness group. Trends were found for an improved orienting attention, but surprisingly a deterioration in alerting attention for the children who followed the MBP (Felver et al., 2017). Thus, previous studies indicate that executive attention could be improved by training mindfulness, while effects on orienting and alerting attention are less consistent.

In this study, we aim to explore the effects of an MBP on the attention systems in children with ASD. Clinically referred children (8-23 years) with ASD and their parents followed a 9-week MBP (MYmind) and were compared to a matched group of TD children on the ANT. We investigated (a) whether there were differences in alerting, orienting, or executive attention between children with ASD and TD children before MYmind but not after MYmind, and (b) whether changes in alerting, orienting, or executive attention occurred at a 2-month follow-up in the ASD group. We hypothesized that children with ASD would show less efficient orienting and executive attention compared to TD children before the MBP, and would improve their orienting and executive attention after the MBP, causing the difference with TD children to decrease or be absent at posttest. Although previous studies show inconclusive results, we expected an improved alerting attention after the MBP for children with ASD, as focused and sustained attention is trained. By using objective evaluation, our study intended to add to the preliminary results indicating benefits of MBPs for children with ASD.

Method

Participants

Participants were a group of 49 children with ASD (8-23 years), and an age-, gender-, and educational level–matched comparison group of 51 TD children (9-20 years). Participants in the ASD group were referred to an academic treatment center for parents and children. They participated in the study investigating MYmind for children with ASD and their parents, approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Academic Medical Center (AMC) in Amsterdam (NL43720.018.13). Results on parent- and self-report questionnaires can be found elsewhere (De Bruin et al., 2015; Ridderinkhof et al., 2018). The present study focuses on the computerized test of attention. Inclusion criteria were a clinical diagnosis of ASD, verified by the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS; Lord et al., 2000; see Table 1), and an (estimated) IQ > 80. Exclusion criteria were inadequate mastery of the Dutch language, severe behavioral problems as indicated by conduct disorder, current suicidal risk, or psychotic disorder. Medication was used by 5 children (10.2 %) and 14 families received additional therapy next to MYmind (28.6 %), including child, parent, family counseling, or cognitive behavior therapy. Participants for the TD group were recruited via primary and secondary schools. Adolescents older than 18 year were recruited using snowball sampling. Exclusion criteria were inadequate mastery of the Dutch language, and a developmental disorder as indicated by parent-report for children till 16 years and self-report for children 16 years and older. The TD group study was approved by the Ethics Review Board of the Child Development and Education department of the University of Amsterdam. The ASD and the TD group received a small present after the measurement occasions. Educational level was divided into three groups: preuniversity secondary education (VWO/Gymnasium), higher general secondary education (HAVO), and preparatory secondary vocational education (VMBO), and for children at primary education based on secondary school advice. It was confirmed that groups were matched on age, t(98) = −0.13, p = .896; gender, χ2(1) = 0.16, p = .689; and educational level, χ2(2) = 0.65, p = .721 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics.

| ASD (n = 49) | TD (n = 51) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (M and SD) | 12.90 (3.24) | 12.98 (3.06) |

| Male | 40 (82%) | 40 (78%) |

| (Advised) secondary education level | ||

| Preuniversity | 26 (53%) | 24 (47%) |

| Higher general | 11 (22%) | 15 (29%) |

| Preparatory vocational | 10 (20%) | 10 (20%) |

| Not available | 2 (4%) | 2 (4%) |

| ASD diagnosis | ||

| Classic autism | 7 (14%) | |

| Asperger syndrome | 16 (33%) | |

| PPD-NOS | 22 (45%) | |

| ASD | 4 (8%) | |

| Comorbid diagnosis | ||

| ADHD | 4 (8%) | |

| Internalizing disordera | 5 (10%) | |

| ADOS classification | ||

| Autism | 12 (25%) | |

| ASD | 26 (53%) | |

| One-point beneath cut-off | 2 (4%) | |

| No ASD classification | 5 (10%) | |

| Not available | 4 (8%) | |

Note. ASD = autism spectrum disorder; TD = typically developing; PPD-NOS = pervasive developmental disorder–not otherwise specified; ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ADOS = Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule.

Internalizing disorders included obsessive compulsive disorder, panic disorder, general anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety disorder—not otherwise specified.

Procedure

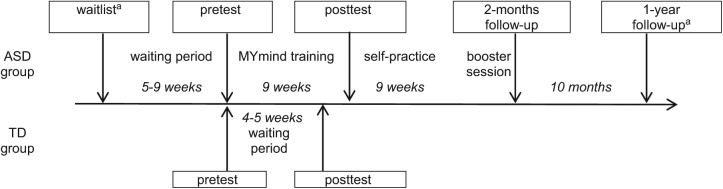

For the first research question, an a-priori analysis, using G*Power 3.1, indicated a sample size of n = 34 to detect a significant effect. For the second research question, a total sample size of n = 36 was needed (α = .05, f = .25, power = .80). Children in the ASD group completed the ANT at five measurement occasions: 9 till 5 weeks before the start of MYmind (waitlist); within 2 weeks prior to the start of MYmind (pretest); within 2 weeks after MYmind (posttest); within 2 weeks after the booster session (2-month follow-up); and 1 year after MYmind (1-year follow-up). As only 15 children completed the waitlist and only 18 completed the 1-year follow-up, these measurement occasions were excluded from the analyses. Four children were excluded from the study, because they completed waitlist only and then dropped out from the study. Waitlist data of one child was used as missing pretest data. Therefore, analyses were based on 49 children, including 42 pretests, 39 posttests, and 36 two-month follow-ups. Children in the TD group completed the ANT at two measurement occasions: the first occasion (pretest); and 4 till 5 weeks later (posttest). At both occasions all 51 children participated. TD children and adolescents did not receive any training between pre- and posttest, but performed the ANT twice to control for the possibility of a learning effect and changes over time. Figure 1 displays the study timeline.

Figure 1.

Study timeline.

Note. ASD = autism spectrum disorder; TD = typically developing.

aThese measurement occasions were excluded from the analyses.

MYmind

Children with ASD participated in MYmind, a manualized MBP with parallel sessions for children and their parents. This program has nine weekly sessions of 1.5 hours in a group of four to six children, and an additional booster session 9 weeks later. The sessions included psychoeducation on ASD and mindfulness, meditation exercises, short inquiry about the exercises, and discussion home practices. Practices included the breathing meditation, 3-min breathing space, body scan, sound meditation, thought meditation, walking meditation, yoga, and informal mindfulness exercises. The program was tailored to specific needs of children with ASD and their parents. Participants trained to apply mindfulness to situations particularly stressful for this group. Also, the meditations consisted of less verbal instructions, and the mindfulness trainer used more direct language. The parent sessions included additional mindful parenting practices. The program was delivered by child mental health care professionals who completed the advanced teacher training in MYmind for youth with ADHD/ASD and their parents, and committed to personal mindfulness practice. For more information see De Bruin and colleagues (2015) and Ridderinkhof and colleagues (2018).

Measurement Procedures

To measure alerting, orienting, and executive attention, the child version of the ANT was used (Rueda et al., 2004). Children performed the test in a quiet room on a laptop, with the experimenter present. They placed their left and right index fingers on the mouse buttons. The test was conducted as described by Rueda and colleagues (2004). In short, participants were instructed to feed a hungry fish, by pressing the mouse button that matched the direction of the middle fish. In addition, they were instructed to focus on the fixation cross and to respond as quick and accurate as possible. They received visual and auditory feedback on the (in)correctness of their responses. The ANT consisted of 24 practice trials and three blocks of 48 experimental trials. Each trial began with a central fixation cross for a random duration between 400 and 1600 ms. This was followed by one of four warning cues for 150 ms: no cue, a center cue, a double cue, and a spatial cue. The center cue consisted of a single asterisk presented at the center. The double cue consisted of two asterisks presented above and below the center. The spatial cue consisted of a single asterisk presented at the same position as the upcoming target fish. After the warning cue the fixation cross appeared for 450 ms. Then, the target fish appeared in one of three types: alone, with flanker fish congruent with the target, or with flanker fish incongruent with the target. Participants had a maximum of 1700 ms to respond. Accuracy and reaction times (RTs) were recorded via the software package E-Prime.

Difference scores were calculated by subtracting the median RTs for the more simple trials from the median RTs for the more difficult trials for each participant on each measurement occasion (Rueda et al., 2004). The alerting score was calculated by subtracting the median RTs for double cue trials from the median RTs for no cue trials. The orienting score was calculated by subtracting the median RTs for spatial cue trials from the median RTs for center cue trials. The executive score was calculated by subtracting the median RTs for congruent trials from the median RTs for incongruent trials. The accuracy difference scores followed the same calculations for percentage of accurate trials (Table 2).

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations of the ANT Variables for the ASD Group and the TD Group at Pretest, Posttest, and 2-Month Follow-Up.

| Pretest |

Posttest |

Follow-up |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASD |

TD |

ASD |

TD |

ASD |

||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Median RT | ||||||||||

| Alerting | 59.49 | 50.12 | 59.58 | 45.32 | 86.37 | 56.00 | 76.86 | 53.18 | 81.65 | 53.76 |

| No cue | 641.76 | 103.89 | 631.41 | 127.00 | 636.72 | 130.49 | 613.70 | 118.01 | 605.74 | 104.01 |

| Double | 582.27 | 91.56 | 571.83 | 101.44 | 550.35 | 116.78 | 536.83 | 89.77 | 524.08 | 79.72 |

| Orienting | 32.19 | 40.87 | 27.25 | 36.59 | 26.17 | 34.15 | 24.27 | 36.64 | 17.04 | 30.10 |

| Central | 599.61 | 105.42 | 592.48 | 109.43 | 569.46 | 120.13 | 551.53 | 103.71 | 530.03 | 87.26 |

| Spatial | 567.42 | 94.27 | 565.24 | 117.81 | 543.29 | 121.31 | 527.25 | 96.09 | 512.99 | 81.00 |

| Executive | 69.95 | 54.27 | 64.60 | 38.38 | 56.65 | 42.60 | 44.25 | 36.48 | 55.74 | 33.18 |

| Incongruent | 653.68 | 116.91 | 641.43 | 123.37 | 614.13 | 123.87 | 594.35 | 101.21 | 582.22 | 86.26 |

| Congruent | 583.73 | 91.74 | 576.83 | 106.29 | 557.47 | 107.86 | 550.11 | 103.07 | 526.49 | 74.72 |

| Accuracy | ||||||||||

| Alerting | −0.66 | 3.41 | −0.22 | 2.98 | −0.28 | 4.84 | −1.20 | 3.16 | −0.69 | 3.72 |

| No cue | 96.89 | 3.43 | 97.77 | 3.04 | 97.22 | 3.55 | 97.33 | 3.77 | 97.15 | 4.33 |

| Double | 97.55 | 3.26 | 97.98 | 2.78 | 97.51 | 4.93 | 98.53 | 2.91 | 97.84 | 3.19 |

| Orienting | 0.26 | 4.11 | 0.33 | 2.70 | −0.57 | 3.26 | −0.16 | 3.01 | −0.31 | 2.88 |

| Central | 97.09 | 5.09 | 98.53 | 2.18 | 97.51 | 2.61 | 98.04 | 2.56 | 97.99 | 3.29 |

| Spatial | 96.83 | 3.86 | 98.20 | 2.35 | 98.08 | 2.72 | 98.20 | 3.08 | 98.30 | 3.13 |

| Executive | −3.37 | 3.74 | −2.08 | 2.47 | −2.51 | 4.97 | −2.37 | 3.25 | −2.66 | 4.16 |

| Incongruent | 95.39 | 4.31 | 96.85 | 2.99 | 96.05 | 5.12 | 96.61 | 3.84 | 96.18 | 5.07 |

| Congruent | 98.76 | 2.21 | 98.94 | 2.33 | 98.56 | 1.92 | 98.98 | 1.83 | 98.84 | 2.36 |

Note. Accuracy is based on percentage of accurate trials. ANT = Attention Network Test; ASD = autism spectrum disorder; TD = typically developing; RT = reaction time.

Statistical Analysis

To investigate whether there were differences in the attention systems between children with ASD and TD children before MYmind but not after MYmind, the pretest and posttest data of both groups were used. Multilevel data analysis was used to account for dependencies within individuals, and to include all available data. For each attention system a model was created with a random intercept, the ANT scores as dependent variable (alerting, orienting, executive), and group (ASD vs. control), time (posttest vs. pretest), and an interaction between group and time as predictors. To investigate whether changes in the attention systems occurred at 2-month follow-up in the ASD group pretest, posttest, and 2-month follow-up data for the ASD group were analyzed. For each attention system a model was built with a random intercept, the ANT score as dependent variable (alerting, orienting, executive) and measurement occasions (pretest and posttest) as predictors. By using the 2-month follow-up as baseline, it could be investigated if children with ASD changed in the attention systems from pretest to follow-up and from posttest to follow-up. Further exploratory analyses were conducted using the mean trial scores (no cue, double cue, center cue, spatial cue, incongruent, and congruent trials) as dependent variable, to investigate potential time, group, and interaction effects for cue and flanker type, and to interpret effects on attention system difference scores.

Outcome measures were standardized, therefore parameter estimates could be interpreted as Cohen’s d effect sizes (0.2 < small < 0.5 < moderate < 0.8 < large; Cohen, 1992). Data inspection revealed 1 till 4 outliers (standardized z score < −3.29 or > 3.29) on outcome variables executive RT difference score, no cue trial RT score, double cue trial RT score, spatial cue trial RT score, and all accuracy scores, which influenced the results of the analyses. Therefore, outliers were winsorized to z = 3.29 or −3.29.

Results

Comparisons Between Groups

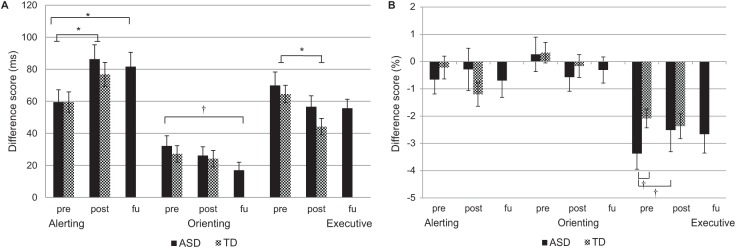

Alerting attention

A significant main effect of time was found on the alerting RT difference score, signifying a small increase in the alerting score from pre- to posttest (Figure 2; Table 3). No significant main effect of group and no significant interaction between group and time was found. This difference score was based on no cue and double cue trials. A small significant effect of time was found on the RT of double cue trials, showing a decrease from pretest to posttest. No effect of time was found on the RT of no cue trials. Furthermore, on the RT of no cue and double cue trials no significant main effect of group, and no significant group by time interaction effect was found. Together, this indicates that the children in the ASD and TD group did not differ before and after the MYmind training on the alerting RT scores, while both groups became faster in the double cue trials. Therefore, the larger alerting RT difference score reflects a more efficient use of cues at posttest for both groups. No significant effects on the alerting accuracy difference score were found for time, group, and their interaction. Also, no effects on no cue and double cue trial accuracy scores were found for time, group, and their interaction (Table 4).

Figure 2.

Attention system scores based on reaction times (A) and accuracy (B) for the ASD and TD group before (pre), after (post), and 2 months after (FU) the ASD group received MYmind.

Note. Error bars represent one standard error of the mean. ASD = autism spectrum disorder; TD = typically developing; FU = follow-up.

†p < .10. *p < .05.

Table 3.

Statistics of the Multilevel Analyses on Attention System RT Difference Scores and Trial RT Scores for (a) the ASD Group Compared to the TD Group Over Time and (b) Follow-Up Effects in the ASD Group.

| Alerting RT |

No cue RT |

Double cue RT |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | F | df | p | B (SE) | F | df | p | B (SE) | F | df | p | |

| (a) | ||||||||||||

| Post vs. Pre | .33 (.15) | 5.09* | 1, 83 | .03 | −.15 (.09) | 2.65 | 1, 80 | .11 | −.35 (.09) | 13.75** | 1, 79 | .00 |

| ASD vs. TD | −.03 (.20) | 0.02 | 1, 160 | .88 | .12 (.21) | 0.36 | 1, 122 | .55 | .18 (.21) | 0.74 | 1, 122 | .39 |

| Time × Group | .21 (.23) | 0.85 | 1, 93 | .36 | .05 (.15) | 0.11 | 1, 85 | .74 | −.06 (.15) | 0.19 | 1, 84 | .66 |

| (b) | ||||||||||||

| Pre vs. FU | −.40 (.19) | 4.32* | 1, 75 | .04 | .24 (.12) | 4.30* | 1, 68 | .04 | .48 (.12) | 16.79** | 1, 68 | .00 |

| Post vs. FU | .10 (.19) | 0.28 | 1, 74 | .60 | .16 (.12) | 1.92 | 1, 68 | .17 | .11 (.12) | 0.91 | 1, 68 | .34 |

| Orienting RT |

Center RT |

Spatial RT |

||||||||||

| B (SE) | F | df | p | B (SE) | F | df | p | B (SE) | F | df | p | |

| (a) | ||||||||||||

| Post vs. Pre | −.08 (.19) | 0.18 | 1, 78 | .68 | −.37 (.08) | 21.38** | 1, 80 | .00 | −.35 (.09) | 15.35** | 1, 79 | .00 |

| ASD vs. TD | .13 (.21) | 0.39 | 1, 178 | .53 | .13 (.20) | 0.42 | 1, 116 | .52 | .09 (.21) | 0.20 | 1, 119 | .65 |

| Time × Group | −.09 (.29) | 0.09 | 1, 90 | .76 | −.01 (.13) | 0.00 | 1, 83 | .95 | .05 (.14) | 0.13 | 1, 84 | .72 |

| (b) | ||||||||||||

| Pre vs. FU | .42 (.23) | 3.51† | 1, 114 | .06 | .54 (.12) | 18.65** | 1, 68 | .00 | .43 (.13) | 11.48** | 1, 68 | .00 |

| Post vs. FU | .25 (.23) | 1.23 | 1, 114 | .27 | .22 (.13) | 3.04† | 1, 67 | .09 | .18 (.13) | 1.94 | 1, 68 | .17 |

| Executive RT |

Incongruent RT |

Congruent RT |

||||||||||

| B (SE) | F | df | p | B (SE) | F | df | p | B (SE) | F | df | p | |

| (a) | ||||||||||||

| Post vs. Pre | −.47 (.16) | 8.19** | 1, 83 | .01 | −.40 (.09) | 21.16** | 1, 80 | .00 | −.26 (.08) | 9.58** | 1, 80 | .00 |

| ASD vs. TD | .15 (.20) | 0.54 | 1, 169 | .46 | .18 (.20) | 0.82 | 1, 119 | .37 | .12 (.20) | 0.34 | 1, 118 | .56 |

| Time × Group | .11 (.25) | 0.20 | 1, 93 | .66 | −.06 (.14) | 0.19 | 1, 84 | .66 | −.07 (.13) | 0.25 | 1, 84 | .62 |

| (b) | ||||||||||||

| Pre vs. FU | .33 (.19) | 3.24† | 1, 72 | .08 | .53 (.12) | 20.54** | 1, 68 | .00 | .47 (.12) | 15.19** | 1, 68 | .00 |

| Post vs. FU | −.03 (.19) | 0.03 | 1, 71 | .87 | .13 (.12) | 1.15 | 1, 68 | .29 | .19 (.12) | 2.34 | 1, 68 | .13 |

Note. B can be interpreted as Cohen’s d effect sizes. RT = reaction time; ASD = autism spectrum disorder; TD = typically developing; FU = follow-up.

p < .10. *p < .05. **p ⩽⩽.01.

Table 4.

Statistics of the Multilevel Analyses on ACC Difference Scores and Trial ACC Scores for (a) the ASD Group Compared to the TD Group Over Time and (b) Follow-Up Effects in the ASD Group.

| Alerting ACC |

No cue ACC |

Double cue ACC |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | F | df | p | B (SE) | F | df | p | B (SE) | F | df | p | |

| (a) | ||||||||||||

| Post vs. Pre | −.27 (.19) | 2.05 | 1, 179 | .15 | −.10 (.17) | 0.30 | 1, 78 | .59 | .16 (.17) | 0.89 | 1, 84 | .35 |

| ASD vs. TD | −.12 (.19) | 0.40 | 1, 179 | .53 | −.26 (.20) | 1.69 | 1, 175 | .20 | −.13 (.18) | 0.49 | 1, 179 | .49 |

| Time × Group | .31 (.28) | 1.25 | 1, 179 | .27 | .20 (.27) | 0.54 | 1, 90 | .46 | −.06 (.25) | 0.07 | 1, 96 | .80 |

| (b) | ||||||||||||

| Pre vs. FU | .01 (.21) | 0.00 | 1, 114 | .97 | −.10 (.19) | 0.26 | 1, 71 | .61 | −.04 (.17) | 0.06 | 1, 77 | .82 |

| Post vs. FU | .06 (.22) | 0.07 | 1, 114 | .79 | −.01 (.20) | 0.01 | 1, 70 | .94 | .03 (.17) | 0.04 | 1, 77 | .84 |

| Orienting ACC |

Center ACC |

Spatial ACC |

||||||||||

| B (SE) | F | df | p | B (SE) | F | df | p | B (SE) | F | df | p | |

| (a) | ||||||||||||

| Post vs. Pre | −.15 (.19) | 0.62 | 1, 179 | .43 | −.15 (.14) | 1.10 | 1, 81 | .30 | .00 (.15) | 0.00 | 1, 82 | 1.00 |

| ASD vs. TD | .00 (.20) | 0.00 | 1, 179 | 1.00 | −.34 (.18) | 3.54† | 1, 169 | .06 | −.41 (.20) | 4.11* | 1, 163 | .04 |

| Time × Group | −.12 (.29) | 0.18 | 1, 179 | .67 | .17 (.22) | 0.63 | 1, 92 | .43 | .35 (.23) | 2.25 | 1, 92 | .14 |

| (b) | ||||||||||||

| Pre vs. FU | .18 (.22) | 0.69 | 1, 79 | .41 | −.12 (.16) | 0.61 | 1, 74 | .44 | −.39 (.17) | 5.10* | 1, 74 | .03 |

| Post vs. FU | −.07 (.22) | 0.10 | 1, 79 | .76 | −.09 (.16) | 0.29 | 1, 74 | .60 | −.07 (.18) | 0.14 | 1, 73 | .71 |

| Executive ACC |

Incongruent ACC |

Congruent ACC |

||||||||||

| B (SE) | F | df | p | B (SE) | F | df | p | B (SE) | F | df | p | |

| (a) | ||||||||||||

| Post vs. Pre | −.08 (.16) | 0.24 | 1, 83 | .63 | −.05 (.14) | 0.14 | 1, 82 | .71 | −.03 (.15) | 0.03 | 1, 81 | .86 |

| ASD vs. TD | −.36 (.20) | 3.42† | 1, 173 | .07 | −.38 (.19) | 3.75† | 1, 159 | .06 | −.11 (.19) | 0.34 | 1, 165 | .56 |

| Time × Group | .41 (.25) | 2.81† | 1, 94 | .10 | .32 (.22) | 2.23 | 1, 92 | .14 | −.11 (.22) | 0.24 | 1, 91 | .62 |

| (b) | ||||||||||||

| Pre vs. FU | −.21 (.18) | 1.41 | 1, 78 | .24 | −.22 (.15) | 2.15 | 1, 76 | .15 | .02 (.18) | 0.02 | 1, 70 | .90 |

| Post vs. FU | .08 (.18) | 0.19 | 1, 77 | .66 | −.02 (.16) | 0.02 | 1, 75 | .89 | −.14 (.18) | 0.62 | 1, 70 | .43 |

Note. B can be interpreted as Cohen’s d effect sizes. ACC = Attention System Accuracy; ASD = autism spectrum disorder; TD = typically developing; FU = follow-up.

p < .10. *p < .05.

Orienting attention

On the orienting RT difference score no significant main effects for time, group, and the interaction between them were found. This difference score was based on center cue and double cue trials. A small significant effect of time was found on the RT of center cue trials, and on the RT of spatial cue trials, showing a decrease from pretest to posttest. On the RT of center cue and spatial cue trials no significant main effect of group, and no significant interaction effect was found. This indicates that the children in the ASD and TD group did not differ before and after the MYmind training on the RT scores, but both became faster on the spatial and center cue trials.

On the orienting accuracy difference score no significant effects of time, group, and the interaction between them were found. However, a small borderline significant effect of group was found on center cue, and a small significant effect on spatial cue trial accuracy scores. Children in the ASD group made more errors on the center cue and spatial cue trials than the children in the TD group on both time points, indicating a somewhat “messier” working style for children with ASD. No time and interaction effects on center cue and spatial cue were found.

Executive attention

On the executive RT difference score a significant main effect of time was found, showing a small decrease. No significant main effect of group, and no significant interaction between group and time was found. This difference score was based on incongruent and congruent flanker trials. A significant main effect of time was found on the RT of incongruent trials, and on the RT of congruent trials, showing a small decrease in RT from pretest to posttest. On the RT of incongruent and congruent trials no significant main effect of group, and no significant interaction effect was found. Together, this indicates that the children in the ASD and TD group did not differ before and after the MYmind training on the executive RT scores. For both groups the increased speed was larger for incongruent trials, therefore, the decreased executive difference score reflects an improved executive attention.

No significant main effect of time was found on the executive accuracy difference score. A small borderline significant effect of group indicated a more negative executive accuracy score for children in the ASD group compared to the TD group (Figure 2; Table 4). Also, a small borderline significant interaction effect between time and group was found on the executive accuracy score (p = .097). Post hoc tests indicated that the executive accuracy difference score did not change for TD children from pre- to posttest, t (50) = 0.57, p = .569, but the difference score became less negative for children with ASD indicated by a trend effect, t (31) = −1.99, p = .056. Also, children with ASD had a more negative executive difference score than TD children at pretest indicated by a trend effect, t (68.55) = −1.92, p = .059, but not at posttest, t (88) = 0.10, p = .924. For the flanker types, a small borderline significant effect of group was found on the incongruent trial accuracy score, but not on the congruent trial accuracy score. Together, these trend effects point in the direction of a weaker executive attention system in terms of accuracy of the ASD group compared to the TD group, and that this group difference disappeared after children with ASD followed the MYmind training.

Follow-Up Effects in the ASD Group

Alerting attention

A small significant increase between pretest and 2-month follow-up was found on the alerting RT difference score (Figure 2; Table 3). No significant difference between posttest and 2-month follow-up was found. Also, on the no cue and double cue trials a small significant decrease in RT between pretest and 2-month follow-up was found, while no significant difference between posttest and 2-month follow-up was found. No significant time effects were found on the alerting accuracy difference score, the no cue, and the double cue trials (Table 4).

Orienting attention

A small borderline significant decrease between pretest and 2-month follow-up was found on the orienting RT difference score, and no significant difference between posttest and 2-month follow-up. On center cue trials a medium significant decrease in RT was found between pretest and 2-month follow-up, and a small borderline significant decrease between posttest and 2-month follow-up. On spatial cue trials a small significant decrease in RT was found between pretest and 2-month follow-up, but not between posttest and 2-month follow-up. The increased speed was larger for center trials than for spatial trials. Therefore, the decreased orienting RT difference score reflects an improved orienting attention at 2-month follow-up.

No significant time effects on orienting accuracy difference score and no time effects on center cue trial accuracy score were found. However, a small significant time effect between pretest and 2-month follow-up was found on spatial cue trial accuracy, while no effect between posttest and follow-up. This indicates that children with ASD scored more accurate on spatial cue trials 2 months after MYmind compared to pretest.

Executive attention

A small borderline significant decrease between pretest and 2-month follow-up was found on the executive RT difference score. No significant difference between posttest and 2-month follow-up was found. Also, on the incongruent and congruent trials a significant decrease in RT between pretest and 2-month follow-up was found, while no significant difference between posttest and 2-month follow-up. The increased speed was larger for incongruent trials, therefore the decreased executive RT difference score reflects an improved executive attention at 2-month follow-up. No significant time effects were found on the executive accuracy difference score, the incongruent, and the congruent trials.

Robustness Checks

We repeated all analyses with exclusion of negative attention system RT difference scores, with exclusion of participants who completed a waitlist, and with exclusion of participants who did not complete a pretest, separately. A negative RT difference score means that participants perform slower on the simple trial than on the more difficult trial, which might indicate they are not paying attention to the test, or the more difficult trial is easier for them for other reasons. Participants who performed a waitlist could show a learning effect at pretest, while participants who did not perform the pretest missed this learning effect at posttest.

Effects on RT scores were in the same direction for all robustness checks. There were changes in significance level and effect sizes, but directions were the same, so this did not lead to other conclusions. However, when excluding participants who completed a waitlist the ASD group did no longer differ from the TD group on the central and spatial trial accuracy scores. In addition, the ASD group significantly differed from the TD group on the executive accuracy difference score, F (1,153.14) = 3.93, p = .049, B = −0.44 (0.22), the interaction effect between time and group became significant, F (1,85.44) = 7.63, p = .007, B = 0.73 (0.26), and there was an additional interaction effect between time and group on the incongruent trial accuracy score, F (1,83.53) = 4.11, p = .046, B = 0.48 (0.23). The improvement in the executive accuracy difference score and on the incongruent trial accuracy score was also present at 2-month follow-up compared to pretest, executive: F (1,58.69) = 6.45, p = .014, B = −0.50 (0.20); incongruent: F (1,58.38) = 5.28, p = .025, B = −0.44 (0.19). This supported the trend effects in the main analyses that indicated a weaker executive attention system based on accuracy for the ASD group compared to the TD group at pretest, while the ASD group caught up after MYmind.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated whether children with ASD showed differences in attention systems compared to TD children before but not after the MBP MYmind, and whether changes occurred for children with ASD at 2-month follow-up. Results indicated that first, children with ASD seem to have no different speed of the attention systems than TD children: They did not differ in RT scores, and they improved similarly over time. However, ASD children showed a somewhat “messier” style: They performed less accurate on both orienting trials, and trend effects indicated a weaker executive accuracy as compared to TD children. Second, no MYmind training effects on this objective measure of attention appeared from the lack of interaction between group and time for both RT and accuracy scores. However, a trend effect and robustness checks showed that children with ASD had a weaker executive accuracy before the MYmind training as compared to TD children, while this difference was no longer present after the MYmind training. This might indicate an improved executive attention for children with ASD by the MYmind training. Also, 2 months later, improvements in orienting attention were found in children with ASD, while not in TD children at posttest. These improvements might indicate MYmind training effects on orienting attention.

With this study, we added an objective evaluation of the effects of MBPs for children with ASD. Previous studies with non-ASD study populations showed improved orienting attention (Felver et al., 2017; Jha et al., 2007) and executive attention (Baijal et al., 2011; Felver et al., 2017; Tang et al., 2007; Zylowska et al., 2008) after MBPs, corresponding to the slight improvements in orienting and executive attention we found in children with ASD. MBPs train participants to switch and reengage their attention (Bishop et al., 2004; Lutz et al., 2008), which could explain the improved orienting attention. Also, MBPs train to recognize automatic tendencies to react and then to respond deliberately instead of automatically (Bishop et al., 2004), which explains why children with ASD who followed an MBP performed more accurate on executive attention tasks. They could recognize the automatic tendency to make a mistake, and then respond correctly. This is an additional step in responding, which could explain why the speed in responding did not increase after training mindfulness.

Improved orienting and executive attention could lead to a cascade of improvements that benefit children with ASD, as attention impairments are theorized to be underlying the development of ASD symptoms (Allen & Courchesne, 2001; Keehn et al., 2013). Improved ability to switch attention could improve central coherency by preventing to be overly focused on local features. Also, improved ability of executive control over attention could enhance attention to social information; instead of automatic withdrawal from social stimuli, children with ASD could learn to direct their attention to it. In addition, improved executive attention could prevent from being distracted by external and internal stimuli while in a social interaction. Furthermore, it could improve the capacity to disengage their attention from distressing automatic thought patterns and feelings, and thereby improve the ability to cope with stress and emotional problems. Improved social responsiveness, attention, and emotional and behavioral functioning were indeed found on parent- and self-reports after MYmind for these children with ASD (de Bruin et al., 2015; Ridderinkhof et al., 2018). However, we should be cautious to conclude that the slight improvements in orienting and executive attention are underlying these behavioral improvements.

One study also showed improved alerting attention after an MBP in children at school (Baijal et al., 2011) but this was not confirmed by our study. Also, MYmind did not improve the speed of orienting and executive attention in children with ASD, which was previously found in other study populations (Baijal et al., 2011; Felver et al., 2017; Jha et al., 2007; Tang et al., 2007; Zylowska et al., 2008). So it seems that an MBP does not improve objectively measured alertness, speed of orienting toward stimuli, and speed of resolving conflict of attention in children with ASD. The ANT assesses the attention systems through fast reacting to cues. Possibly, MBPs do not target this fast reacting. Although it is practiced to pay attention to experiences in the present moment, it is also practiced not to react automatically, but rather to take a moment between perception and response (Bishop et al., 2004).

Furthermore, lack of beneficial effects of the MBP could be due to the finding that, unexpectedly, this group of children with ASD hardly showed attention problems on the ANT, making it questionable whether they needed to improve. These results are supported by previous studies that showed no differences in alerting attention between children with ASD and TD children (Keehn et al., 2010; Mutreja et al., 2016). Also, Fan and colleagues (2012) did not find differences between adults with ASD and controls in orienting attention. However, previous studies did show a less efficient speed in orienting attention for children with ASD (Keehn et al., 2010; Mutreja et al., 2016). Our results in executive attention are in line with previous studies, showing no differences in speed, but a less accurate performance on executive attention (Fan et al., 2012; Keehn et al., 2010; Mutreja et al., 2016). However, the differences that we found were small and only approached significance, so should be interpreted with caution. The other studies used smaller sample sizes (ASD group n = 12-20), which reduces the likelihood that the statistically significant differences between the groups reflected a difference between populations. A possible explanation for the lack of differences in attention between children with ASD and TD children is that children with ASD show heterogeneity in their symptoms and underlying cognitive functioning, resulting in no differences when categorically comparing groups (e.g., Verté, Geurts, Roeyers, Oosterlaan, & Sergeant, 2006). Future studies could investigate the relation between ASD and the attention systems with a dimensional approach.

Another possible explanation for the lack of difference between ASD and TD children on the ANT is the relatively low comorbidity rate of ADHD in our sample compared to studies that investigated comorbidity rates of ADHD (e.g., van Steensel et al., 2013). This could imply that not ASD but comorbid ADHD would be responsible for differences in attention between ASD and TD children. However, ADHD rates in our study were based on the number of children that were clinically diagnosed with ADHD before inclusion, not the number of children that met the criteria for ADHD on a diagnostic interview conducted for all children. A simultaneous diagnosis of ADHD and ASD is only allowed since the latest Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (APA, 2013)—this could explain the low rate of ADHD in our sample.

This study has several limitations. Although the ANT is a commonly used test to objectively assess attention, there are some indications that the test–retest reliability of the ANT is low (Rueda et al., 2004). Future studies could use attention tests with well-studied and high test–retest reliabilities. In addition, to investigate the effects of an intervention the design would be stronger if a control group of children with ASD was used. This study, however, also has strengths. By assessing the control group twice, we were able to control for the learning effects. Also, we used a relatively large sample size to compare children with ASD to TD children. Finally, this study adds an objective evaluation of MBPs for children with ASD to this emerging research field.

In sum, children with ASD were as fast as TD children in their attention systems, but were to some extent less accurate in orienting and executive attention. In general MYmind did not improve their attention systems, nonetheless trend effects point into the direction of improved orienting and executive attention. MBPs are promising and feasible for children with ASD and their parents (e.g., de Bruin et al., 2015; Ridderinkhof et al., 2018; Singh, Lancioni, Singh, et al., 2011), but this study could not strongly support the found behavioral changes with an objective test of attention. This implies that an MBP mainly improves behavioral functioning in children with ASD, while underlying attention processes are hardly affected. Future research should further explore the underlying mechanisms of MBPs to better understand how mindfulness could benefit children with ASD, which could in turn be used to improve interventions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the children and their parents for their time and effort to participate in this study. We would also like to thank the research assistants for their valuable contribution to the data collection.

Author Biographies

Anna Ridderinkhof, MSc, is a PhD candidate at the Research Institute of Child Development and Education of the University of Amsterdam. Her research focuses on MBPs for children with ASD and their parents, and on mindfulness and empathy.

Esther I. de Bruin, PhD, is an associate professor at the Research Institute of Child Development and Education of the University of Amsterdam and health care psychologist. Her research focuses on the development, evaluation, and implementation of MBPs in mental health care and at work.

Sanne van den Driesschen, BSc, is a research master student at the Research Institute of Child Development and Education of the University of Amsterdam. Her research interests include clinical and behavioral characteristics of individuals with ASD and other (neuro)psychiatric disorders.

Susan M. Bögels, PhD, is a psychotherapist and professor in developmental psychopathology at the Research Institute of Child Development and Education, and at the department Developmental Psychology of the University of Amsterdam. Her main research interests are the intergenerational transmission of anxiety and MBPs.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Susan M. Bögels owns shares in UvA minds, the participating treatment center.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Anna Ridderinkhof  http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6512-3931

http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6512-3931

References

- Allen G., Courchesne E. (2001). Attention function and dysfunction in autism. Frontiers in Bioscience, 6, 105-119. doi: 10.2741/A598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Baijal S., Jha A., Kiyonaga A., Singh R., Srinivasan N. (2011). The influence of concentrative meditation training on the development of attention networks during early adolescence. Frontiers in Psychology, 2, 153. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S. (2000). Theory of mind and autism: A review. International Review of Research in Mental Retardation, 23, 169-184. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7750(00)80010-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop S. R., Lau M., Shapiro S., Carlson L., Anderson N. D., Carmody J., . . . Devins G. (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11, 230-241. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bph077 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. (1992). A power primer. Pyschological Bulletin, 112, 155-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson R. J., Kaszniak A. W. (2015). Conceptual and methodological issues in research on mindfulness and meditation. American Psychologist, 70, 581-592. doi: 10.1037/a0039512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruin E. I., Blom R., Smit F. M., van Steensel F. J., Bögels S. M. (2015). MYmind: Mindfulness training for youngsters with autism spectrum disorders and their parents. Autism, 19, 906-914. doi: 10.1177/1362361314553279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J., Bernardi S., Van Dam N. T., Anagnostou E., Gu X., Martin L., . . . Grodberg D. (2012). Functional deficits of the attentional networks in autism. Brain and Behavior, 2, 647-660. doi: 10.1002/brb3.90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J., McCandliss B. D., Sommer T., Raz A., Posner M. I. (2002). Testing the efficiency and independence of attentional networks. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 14, 340-347. doi: 10.1162/089892902317361886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felver J. C., Tipsord J. M., Morris M. J., Racer K. H., Dishion T. J. (2017). The effects of mindfulness-based intervention on children’s attention regulation. Journal of Attention Disorders, 21, 872-881. doi: 10.1177/1087054714548032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happé F., Frith U. (2006). The weak coherence account: Detail-focused cognitive style in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36, 5-25. doi: 10.1007/s10803-005-0039-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill E. L. (2004). Executive dysfunction in autism. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8, 26-32. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2003.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hölzel B. K., Lazar S. W., Gard T., Schuman-Olivier Z., Vago D. R., Ott U. (2011). How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6, 537-559. doi: 10.1177/1745691611419671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang Y. S., Kearney P., Klieve H., Lang W., Roberts J. (2015). Cultivating mind: Mindfulness interventions for children with autism spectrum disorder and problem behaviours, and their mothers. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 3093-3106. doi: 10.1007/s10826-015-0114-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jha A. P., Krompinger J., Baime M. J. (2007). Mindfulness training modifies subsystems of attention. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 7, 109-119. doi: 10.3758/CABN.7.2.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. (1994). Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. New York, NY: Hyperion. [Google Scholar]

- Keehn B., Lincoln A. J., Müller R. A., Townsend J. (2010). Attentional networks in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51, 1251-1259. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02257.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keehn B., Müller R. A., Townsend J. (2013). Atypical attentional networks and the emergence of autism. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 37, 164-183. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.11.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keehn B., Nair A., Lincoln A. J., Townsend J., Müller R. A. (2016). Under-reactive but easily distracted: An fMRI investigation of attentional capture in autism spectrum disorder. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 17, 46-56. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2015.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry O., Parker A. (2013). A meta-analysis of visual orienting in autism. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 833. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C., Risi S., Lambrecht L., Cook E. H., Leventhal B. L., DiLavore P. C., . . . Rutter M. (2000). The autism diagnostic observation schedule—Generic: A standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30, 205-223. doi: 10.1023/A:1005592401947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz A., Slagter H. A., Dunne J. D., Davidson R. J. (2008). Attention regulation and monitoring in meditation. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 12, 163-169. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutreja R., Craig C., O’Boyle M. W. (2016). Attentional network deficits in children with autism spectrum disorder. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 19, 389-397. doi: 10.3109/17518423.2015.1017663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen S. E., Posner M. I. (2012). The attention system of the human brain: 20 years after. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 35, 73-89. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-062111-150525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner M. I., Petersen S. E. (1990). The attention system of the human brain. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 13, 25-42. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.13.030190.000325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridderinkhof A., de Bruin E. I., Blom R., Bögels S. M. (2018). Mindfulness-based program for children with autism spectrum disorder and their parents: Direct and long-term improvements. Mindfulness, 9, 773-791. doi: 10.1007/s12671-017-0815-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueda M. R., Fan J., McCandliss B. D., Halparin J. D., Gruber D. B., Lercari L. P., Posner M. I. (2004). Development of attentional networks in childhood. Neuropsychologia, 42, 1029-1040. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2003.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh N. N., Lancioni G. E., Manikam R., Winton A. S., Singh A. N., Singh J., Singh A. D. (2011). A mindfulness-based strategy for self-management of aggressive behavior in adolescents with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5, 1153-1158. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2010.12.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh N. N., Lancioni G. E., Singh A. D., Winton A. S., Singh A. N., Singh J. (2011). Adolescents with Asperger syndrome can use a mindfulness-based strategy to control their aggressive behavior. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5, 1103-1109. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2010.12.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y. Y., Ma Y., Wang J., Fan Y., Feng S., Lu Q., . . . Posner M. I. (2007). Short-term meditation training improves attention and self-regulation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104, 17152-17156. doi:10.1073pnas.0707678104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Steensel F. J., Bögels S. M., de Bruin E. I. (2013). Psychiatric comorbidity in children with autism spectrum disorders: A comparison with children with ADHD. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 22, 368-376. doi: 10.1007/s10826-012-9587-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verté S., Geurts H. M., Roeyers H., Oosterlaan J., Sergeant J. A. (2006). The relationship of working memory, inhibition, and response variability in child psychopathology. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 151, 5-14. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zylowska L., Ackerman D. L., Yang M. H., Futrell J. L., Horton N. L., Hale T. S., . . . Smalley S. L. (2008). Mindfulness meditation training in adults and adolescents with ADHD: A feasibility study. Journal of Attention Disorders, 11, 737-746. doi: 10.1177/1087054707308502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]