Significance Statement

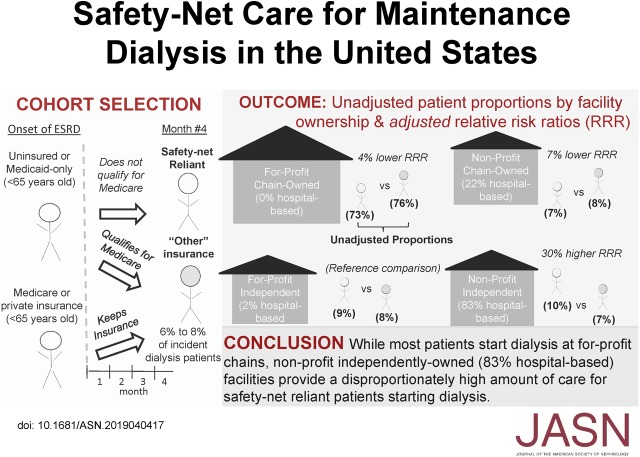

Information about where patients in the United States with limited health insurance coverage receive maintenance dialysis has been lacking. The authors identified patients who were “safety-net reliant”—those who were uninsured and who did not qualify for Medicare had only Medicaid coverage—and found the proportion of patients <65 years initiating dialysis who were safety net–reliant increased between 2008 and 2015 from 11% to 14%. Although 73% of patients who were safety-net reliant received care at for-profit/chain-owned facilities, they were 30% more likely to start dialysis at nonprofit/independently owned (often hospital-affiliated) facilities compared with other facility ownership types—an association most pronounced among patients without insurance. Ongoing loss of market share of nonprofit/independently owned and hospital-based facilities may affect access to outpatient dialysis care for populations with limited health insurance coverage.

Keywords: dialysis, epidemiology and outcomes, United States Renal Data System, economic impact

Visual Abstract

Abstract

Background

Although most American patients with ESKD become eligible for Medicare by their fourth month of dialysis, some never do. Information about where patients with limited health insurance receive maintenance dialysis has been lacking.

Methods

We identified patients initiating maintenance dialysis (2008–2015) from the US Renal Data System, defining patients as “safety-net reliant” if they were uninsured or had only Medicaid coverage at dialysis onset and had not qualified for Medicare by the fourth dialysis month. We examined four dialysis facility ownership categories according to for-profit/nonprofit status and ownership (chain versus independent). We assessed whether patients who were safety-net reliant were more likely to initiate dialysis at certain facility types. We also examined hospital-based affiliation.

Results

The proportion of patients <65 years initiating dialysis who were safety-net reliant increased significantly over time, from 11% to 14%; 73% of such patients started dialysis at for-profit/chain-owned facilities compared to 76% of all patients starting dialysis. Patients who were safety-net reliant had a 30% higher relative risk of initiating dialysis at nonprofit/independently owned versus for-profit/independently owned facilities (odds ratio, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.24 to 1.36); they had slightly lower relative risks of initiating dialysis at for-profit and non-profit chain-owned facilities, and were more likely to receive dialysis at hospital-based facilities. These findings primarily reflect increased likelihood of dialysis among patients without insurance at certain facility types.

Conclusions

Although most patients who were safety-net reliant received care at for-profit/chain-owned facilities, they were disproportionately cared for at nonprofit/independently owned and hospital-based facilities. Ongoing loss of market share of nonprofit/independently owned outpatient dialysis facilities may affect safety net–reliant populations.

In the United States, adult patients without stable health insurance coverage can face significant barriers to accessing healthcare.1–3 Patients who are uninsured or who only have coverage through state Medicaid programs (collectively referred to herein as “safety-net reliant”) commonly rely on a patchwork of safety-net providers for their care. Traditional core healthcare safety-net providers include nonprofit, federally qualified health centers; community health centers; and public hospitals.4 Recognized threats to the viability of safety-net providers in the United States have included increasing demand for care among economically vulnerable populations, rising healthcare costs, growth of managed care, and changes in provider market competition.4–7

In the United States, patients with ESKD frequently come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds and incur high healthcare costs that effectively prohibit out-of-pocket payment for dialysis care or transplantation.8 For most patients with ESKD, public assistance is necessary to ensure access to dialysis care. Although the majority of patients with ESKD automatically qualify for Medicare coverage on the basis of their disease, not all patients meet work and legal-residency criteria for Medicare coverage. Some patients with ESKD who do not have Medicare or private health insurance rely on emergency departments for “emergent” dialysis care when presenting with life-threatening complications from irreversible kidney failure,9–12 whereas others are able to receive maintenance dialysis. A survey of three states in 1991 found that between 3% and 8% of patients receiving maintenance dialysis had Medicaid-only insurance.13 Moreover, little is known about safety-net providers of maintenance dialysis.

Outpatient maintenance dialysis care differs from other areas of healthcare in several ways that might uniquely influence the composition of the safety net–reliant patient population and safety-net providers. Because Medicare covers a majority of patients at the beginning of their fourth month of ESKD,14 the size of the safety net–reliant ESKD population may be relatively small. Unlike many other areas of healthcare, dialysis care in the United States is increasingly furnished by large for-profit chains, with two organizations currently caring for more than two thirds of patients receiving dialysis.15 Furthermore, local dialysis markets are highly concentrated compared with many other areas of healthcare.16 In this study, we describe the safety net–reliant population receiving maintenance dialysis in the United States, and identify characteristics of the dialysis facilities that care for patients who are safety-net reliant in the outpatient setting.

Methods

Data Sources and Patient Selection

We identified all patients in the United States initiating outpatient hemodialysis, home hemodialysis, or peritoneal dialysis as their first ESKD treatment between 2008 and 2015 from the US Renal Data System (USRDS) registry, which includes information about nearly every American patient who develops ESKD. We excluded from our primary analysis patients ≥65 years old, who primarily had Medicare coverage at the time of dialysis initiation. We assigned patients to the facility where they initiated outpatient dialysis, and required that patients lived and received dialysis for at least 90 days. We ascertained information about patient demographics, health insurance, and medical comorbidities at dialysis initiation from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Medical Evidence Report (form CMS-2728), which nephrologists complete at the onset of ESKD. Information about dialysis facilities came from annual facility surveys and the CMS Dialysis Facility Compare website, whereas health insurance status after 3 months of dialysis came from Medicare enrollment data (Supplemental Appendix 1). These enrollment data include information about Traditional Medicare, Medicare Advantage, patients listed as “waiting for Medicare,” and private group health insurance. Patients who only had Medicaid or who were uninsured are classified in the enrollment database as having “other” health insurance. We used zip codes to merge patients and dialysis facilities to the Dartmouth Atlas of Healthcare,17 the US Census, and Rural-Urban Commuting Area data,18 to identify hospital service areas and hospital referral regions, socioeconomic characteristics, and population density, respectively.

Study Outcome

The primary study outcome was the type of dialysis facility where patients initiated outpatient dialysis. Considering national trends toward for-profit and chain ownership of dialysis facilities,15 we focused on the following four mutually exclusive facility ownership categories: (1) nonprofit, chain-owned facilities; (2) nonprofit, independently owned facilities, (3) for-profit, chain-owned facilities, and (4) for-profit, independently owned facilities. We also examined whether patients initiated dialysis at a hospital-based versus free-standing facility.

Study Exposure and Covariates

The primary study exposure was whether a patient had limited health insurance, placing them at increased risk of reliance on safety-net care providers (i.e., whether a patient was safety-net reliant). Because many patients who are uninsured or who have Medicaid only at the start of dialysis become eligible for Medicare after 3 months of dialysis, we required that patients be uninsured or have Medicaid only at the start of dialysis and that they did not acquire Medicare coverage (or have employer-provided group health insurance) by their fourth month of dialysis. We classified all other patients, including those with Medicare, Veteran’s Health Administration, and private health insurance coverage at the onset of dialysis, and those who acquired Medicare (with or without Medicaid) after 3 months of dialysis, as having “other insurance.” In all regression analyses, we controlled for patient demographic, socioeconomic, and health characteristics as well as geographic characteristics listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics stratified by insurance coverage

| Characteristics | Medicaid or Uninsured (n=54,995) | Other Insurance (n=389,930) |

|---|---|---|

| Patient demographic characteristics | ||

| Age (%) | ||

| <50 yr | 46 | 33 |

| 50–65 yr | 54 | 67 |

| Female (%) | 47 | 41 |

| Race (%) | ||

| Black | 41 | 33 |

| American Indian | 1 | 1 |

| White | 51 | 61 |

| “Other” race | 7 | 5 |

| Hispanic ethnicity (%) | 23 | 15 |

| Patient health characteristics | ||

| No. medical comorbidities (%) | ||

| 0–1 | 71 | 68 |

| 2 | 18 | 20 |

| >2 | 11 | 13 |

| Smokes (%) | 11 | 8 |

| Drug or alcohol abuse (%) | 8 | 3 |

| Immobile (%) | 7 | 5 |

| Socioeconomic characteristics | ||

| Employed (%) | 7 | 20 |

| Median income (zip code) (1 unit=$10,000)a | 4.5 | 4.9 |

| Facility and geographic characteristics (%) | ||

| Nonprofit | ||

| Independently owned | 10 | 7 |

| Chain owned | 7 | 8 |

| For profit | ||

| Independently owned | 9 | 8 |

| Chain owned | 73 | 76 |

| Population densityb | ||

| Metropolitan area | 88 | 83 |

| Micropolitan area | 7 | 10 |

| Small town | 4 | 5 |

| Rural area | 2 | 3 |

| HSA-level facility market competition | ||

| More competitive market | 10 | 5 |

| Moderately competitive market | 60 | 56 |

| Less competitive market | 31 | 39 |

P value comparing difference in means or proportions was <0.001 in all characteristics. Although not included in regression models, 44% of patients who were safety-net reliant reported receiving pre-ESKD nephrology care, compared with 59% of patients who were not safety-net reliant. HSA, hospital service area.

Median income was obtained from patient zip codes using census data.

Population density is based on patient residence.

Different types of dialysis providers may be more or less likely to be located in a given area depending on the amount of local competition for dialysis care. If market competition is also associated with where safety net–reliant patients live, this could be a potential source of bias. To account for differences in market competition, we measured a commonly used index of local dialysis market competition in each calendar year: the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI).16,19–21 The HHI ranges from near zero (perfectly competitive markets) to one (monopolistic markets). Influenced by Federal Trade Commission guidelines, we used three categories to describe dialysis market concentration: most competitive (HHI<0.25), middle concentration (0.25<HHI<0.5), and least competitive (HHI>0.5)22 (Supplemental Appendix 2).

Study Design

We compared characteristics of patients who were safety-net reliant to all other patients initiating outpatient dialysis in the United States. We plotted the distribution of dialysis facilities stratified according to ownership type and their relative sizes of safety net–reliant populations, which we measured as the percentage of a facility’s total incident dialysis population who were safety-net reliant over the study period. We then compared characteristics of facilities across quartiles of the proportion of patients who were safety-net reliant. After ranking hospital referral regions by quartiles based on proportions of patients who were safety-net reliant, we illustrated the geographic distribution in the provision of outpatient dialysis safety-net care.

We used multivariable, multinomial, logistic regression models at the individual patient level to examine the likelihood of dialysis at each of the four possible facility types (i.e., nonprofit/independently owned, nonprofit/chain owned, for profit/independently owned, and for profit/chain owned). The model simultaneously estimated the relative risk ratio (RRR) of dialysis at each facility ownership type as a function of safety net–reliant status, while controlling for patient and geographic characteristics listed in Table 1 and the calendar year of dialysis initiation. We also used estimated marginal effects to present findings as changes in absolute probabilities.

An initial examination of our data indicated that 83% of nonprofit/independently owned facilities were hospital based, compared with 0%, 2%, and 22% of facilities owned by for profit/chains, for profit/independents, and nonprofit/chains, respectively. In a separate analysis, we used the model described above to examine the association between safety-net reliance and the odds of initiating dialysis at a hospital-based facility. We did not include other ownership categories (e.g., chain and for-profit status) in this analysis. However, we then examined whether observed associations among safety-net reliance and for-profit/chain ownership categories persisted after accounting for whether a facility was hospital based.

Safety net–reliant patients may be more likely to dialyze at certain types of dialysis facilities due to efforts by individual patients, physicians, and/or facilities to target (or avoid) one another during the processes of facility selection and assignment. Alternatively, patients who are safety-net reliant may be more likely to dialyze at certain facility types because those facilities are more likely to be located near where patients who are safety-net reliant live. To differentiate between these alternative possibilities, we constructed multinomial logit models where assignment to dialysis facility ownership type (or hospital-based designation) was conditional upon the set of facilities from which each patient could choose (or be assigned) to receive dialysis.23 Conditional logit demand (“discrete choice”) models are commonly used in economics to examine consumer choices and demand for differentiated products, but have also been used to examine choices in healthcare settings.20,21,24 In this model, we used patient zip codes to identify a set of possible dialysis facility choices (or assignments) available to each patient (Supplemental Appendix 3). By conditioning upon the set of choices available to each patient, model estimates were independent of the possibility that certain facility types may be more likely than others to be located near patients who are safety-net reliant. We excluded from these analyses 90,562 patients (20%) whose zip code had only one facility ownership type to choose from or who initiated dialysis at a facility more than 100 miles from their documented residence.

In separate analyses, we decomposed the safety net–reliant group into two groups, based on the insurance patients had at the onset of ESKD: Medicaid only and uninsured. We also examined the sensitivity or our findings to key model assumptions and examined the following alternative specifications for safety-net reliance: (1) patients who were uninsured at the start of dialysis but who became Medicare eligible by their fourth dialysis month, and (2) patients who were dual eligible for Medicare and Medicaid on their fourth dialysis month.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

We identified 444,925 patients <65 years old who started dialysis between 2008 and 2015. On average throughout the study period, 76% (n=338,288) of patients initiated dialysis at for-profit/chain-owned facilities, 8% initiated dialysis at for-profit/independently owned facilities (n=35,814), non-profit/chain-owned facilities (n=36,522), and non-profit/independently-owned facilities (n=34,301).

Patients who were safety-net reliant comprised 12% of patients under the age of 65 at dialysis initiation (n=54,995). Among patients who were safety-net reliant, 80% (n=44,011) had Medicaid at the onset of dialysis, whereas 10,984 (20%) were uninsured. The proportion of patients <65 years old who were safety-net reliant at the start of dialysis increased over time, ranging from 11% in 2008 to 2009 to 14% in 2015 (P value testing linear trend <0.001). Among patients identified as safety-net reliant after 3 months of dialysis, <7% acquired Medicare coverage during the remainder of the first year of ESKD, indicating that health insurance remained limited within this population (Supplemental Figure 1).

The conditional logit analysis examining for-profit/chain ownership included 346,757 patients. On average, dialysis was initiated at 15 different facilities per zip code (interquartile range, 7–20), although these different facilities frequently shared the same chain owner. The conditional logit analysis examining hospital-based facilities included 426,262 patients with a choice between at least one hospital- and nonhospital-based facility.

Patients who were safety-net reliant differed in every observed characteristic compared with those with more stable insurance coverage. Such patients were younger and were more likely to be female, black, American Indian, and of Hispanic ethnicity. Patients who were safety-net reliant had fewer comorbidities, were less likely to be employed, lived in areas with lower median incomes, and lived in metropolitan areas. In unadjusted analyses, patients who were safety-net reliant were more likely to receive care at independently owned facilities (both nonprofit and for profit) compared with patients who were not safety-net reliant. Patients who were safety-net reliant were also less likely to receive care at chain-owned facilities (both nonprofit and for profit) compared with patients who were not safety-net reliant. However, >70% of patients in both insurance groups received care at chain-owned, for-profit facilities (Supplemental Tables 1 and 2, Table 1).

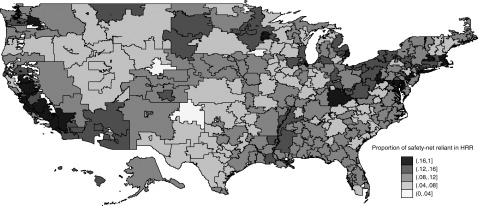

The proportion of incident patients on dialysis who were safety-net reliant varied geographically. Areas with the largest proportions of patients who were safety-net reliant included Central and Southern California, the Pacific Northwest, the Gulf Coast, Great Lakes, and the Northeast (Figure 1), roughly corresponding with higher population densities. Within each dialysis facility, the proportions of patients who were safety-net reliant were correlated over time. When comparing the proportions of patients who were safety-net reliant within each facility between 2008–2010 and 2011–2015, the correlation coefficient was 0.46 (P<0.001).

Figure 1.

The distribution of patients with medicaid only or no health insurance varies geographically. The figure illustrates the distribution of patients with medicaid-only or no health insurance across hospital referral regions, by proportion of patients who are safety-net reliant. It only illustrates those patients who are safety-net reliant and who obtain access to maintenance dialysis care. It does not include patients who never receive this care. HRR, hospital referral region.

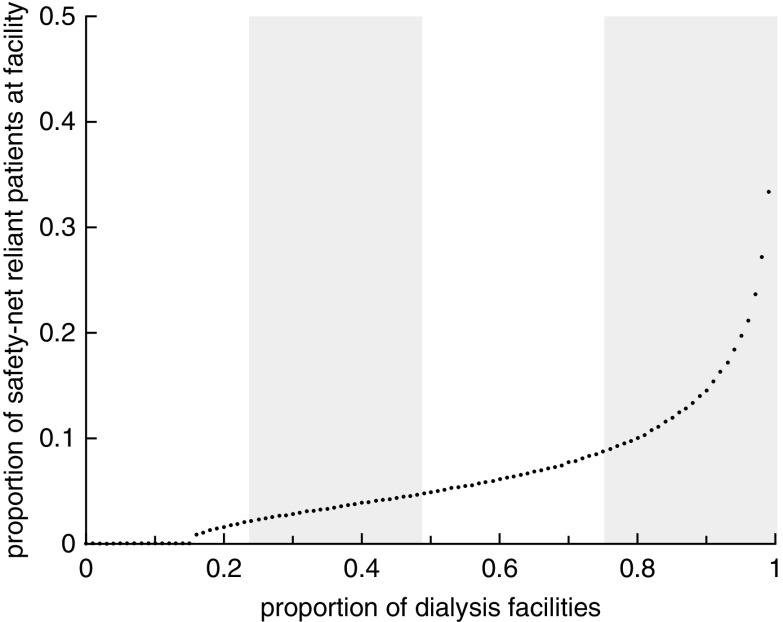

When we stratified dialysis facilities based on the proportions of incident patients on dialysis at each facility who were safety-net reliant (aggregated over the entire study period), we observed that some dialysis facilities provided disproportionately high and low shares of care for safety net–reliant populations. The mean percentages of patients who were safety-net reliant were 0%, 6%, 12%, and 32% in the first, second, third, and fourth quartiles, respectively, and these distributions varied according to ownership type (Figure 2, Supplemental Figures 2 and 3). Compared with facilities in the lowest quartile of caring for patients who were safety-net reliant, those facilities in the highest quartile of caring for patients who were safety-net reliant were larger. Independently owned facilities (both nonprofit and for profit) were more likely to be in both the first and fourth quartiles of safety-net reliant relative to their counterparts (Supplemental Table 3).

Figure 2.

There is variation in the distribution of dialysis facilities in the United States by proportion of patients who are safety-net reliant between 2008 and 2015. A total of 6064 dialysis facilities are included.

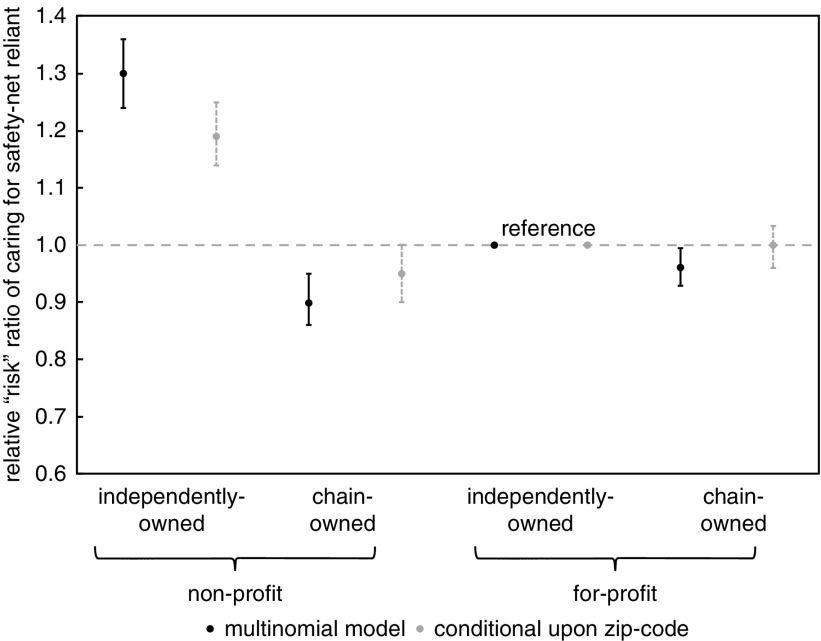

Regression Results: Chain and For-profit Ownership

The likelihood of patients initiating dialysis at for-profit/independently owned facilities served as the “reference” in all regression models. In a multivariable, multinomial regression where we controlled for patient and geographic characteristics, the risk of initiating dialysis at nonprofit/independently owned facilities relative to reference facilities was 30% higher among patients who were safety-net reliant and receiving maintenance dialysis compared with patients who were not safety-net reliant (95% CI, 24% to 36%). In contrast, the risks of initiating dialysis at nonprofit and for-profit chains relative to reference facilities were 10% lower (95% CI, −5% to −14%) and 4% lower (95% CI, −1% to −7%), respectively, among patients who were safety net–reliant and receiving maintenance dialysis when compared with patients who were not safety-net reliant (Figure 3, Table 2). According to predictions from these estimates, patients who were safety-net reliant experienced a 2% increase in the absolute probability of dialysis at nonprofit/independently owned facilities (95% CI, 2.0% to 2.5%), and decreases in absolute probabilities of 0.7% (95% CI, −0.9% to −0.4%) and 1.5% (95% CI, −1.9% to −1.2%) at nonprofit and for-profit chain-owned facilities, respectively. There was no estimated change in the probability of dialysis at for-profit/independently owned (reference) facilities (P=0.9; Supplemental Figure 4).

Figure 3.

The likelihood of dialysis at different facility types among patients who are safety-net reliant relative to other patients initiating dialysis varies by ownership and chain status. The likelihoods of dialysis at for-profit/independently owned facilities served as the reference in both models.

Table 2.

Primary results from multinomial regression model comparing the likelihood of dialysis at different facility types among patients who are safety-net reliant versus other patients

| Covariates | Relative Risk Ratio (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nonprofit Chaina | Nonprofit Independenta | For-Profit Chaina | |

| Safety-net reliant | 0.90 (0.86 to 0.95) | 1.30 (1.24 to 1.36) | 0.96 (0.93 to 1.00) |

| Demographics | |||

| Female | 1.01 (0.98 to 1.04) | 0.98 (0.95 to 1.01) | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.02) |

| Age (<50 is referent) | |||

| 50–65 yr | 0.89 (0.86 to 0.92) | 0.74 (0.72 to 0.77) | 0.98 (0.95 to 1.00) |

| Race (white is referent) | |||

| Black | 1.15 (1.11 to 1.20) | 0.86 (0.82 to 0.89) | 1.13 (1.10 to 1.16) |

| American Indian | 2.35 (2.08 to 2.66) | 1.76 (1.54 to 2.00) | 0.85 (0.76 to 0.95) |

| Other | 1.11 (1.04 to 1.18) | 0.73 (0.68 to 0.78) | 0.80 (0.76 to 0.84) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 0.67 (0.64 to 0.70) | 0.73 (0.70 to 0.76) | 0.91 (0.88 to 0.94) |

| Health and socioeconomic | |||

| Medical comorbidities (<2 is referent) | |||

| 2 | 1.00 (0.96 to 1.04) | 1.01 (0.97 to 1.05) | 0.91 (0.88 to 0.94) |

| >2 | 0.91 (0.87 to 0.95) | 0.98 (0.94 to 1.03) | 0.71 (0.68 to 0.73) |

| Smokes | 1.17 (1.11 to 1.23) | 1.05 (0.99 to 1.11) | 0.92 (0.88 to 0.96) |

| Drug or alcohol abuse | 1.25 (1.16 to 1.34) | 1.17 (1.09 to 1.27) | 0.93 (0.87 to 0.98) |

| Immobility | 0.70 (0.66 to 0.74) | 0.76 (0.71 to 0.80) | 0.64 (0.61 to 0.67) |

| Median income (zip code) of $10,000 | 1.07 (1.06 to 1.07) | 1.06 (1.05 to 1.06) | 1.01 (1.00 to 1.01) |

| Employed | 1.16 (1.11 to 1.21) | 1.38 (1.33 to 1.44) | 1.02 (0.99 to 1.06) |

| Geographic | |||

| Population density (micropolitan is referent) | |||

| Metropolitan | 1.39 (1.31 to 1.47) | 0.59 (0.55 to 0.62) | 1.48 (1.42 to 1.55) |

| Small town | 0.96 (0.88 to 1.04) | 0.92 (0.85 to 1.00) | 0.89 (0.83 to 0.95) |

| Rural | 1.12 (1.01 to 1.24) | 1.22 (1.10 to 1.35) | 0.83 (0.77 to 0.91) |

| HSA-level facility market competition (more competitive market is referent) | |||

| Moderately competitive market | 5.78 (5.40 to 6.19) | 0.97 (0.94 to 1.01) | 6.87 (6.63 to 7.11) |

| Less competitive market | 16.72 (15.53 to 18.01) | 0.70 (0.66 to 0.74) | 17.05 (16.33 to 17.79) |

| Calendar year (2008 is referent) | |||

| 2009 | 1.21 (1.15 to 1.29) | 1.06 (1.01 to 1.13) | 1.23 (1.18 to 1.29) |

| 2010 | 1.17 (1.11 to 1.24) | 0.97 (0.92 to 1.02) | 1.23 (1.18 to 1.29) |

| 2011 | 1.22 (1.15 to 1.29) | 0.96 (0.91 to 1.02) | 1.33 (1.27 to 1.39) |

| 2012 | 1.16 (1.10 to 1.23) | 0.84 (0.79 to 0.89) | 1.31 (1.26 to 1.37) |

| 2013 | 1.16 (1.09 to 1.23) | 0.69 (0.65 to 0.73) | 1.45 (1.39 to 1.51) |

| 2014 | 1.15 (1.09 to 1.22) | 0.62 (0.59 to 0.66) | 1.49 (1.43 to 1.56) |

| 2015 | 1.10 (1.04 to 1.17) | 0.65 (0.61 to 0.69) | 1.42 (1.36 to 1.49) |

Includes 444,925 patients. For-profit, independently owned facilities served as the reference group in the model. Intercepts not included in the table. HSA, hospital service area.

For-profit independently-owned facilities serve as the reference group.

We conducted several analyses to better understand the reasons for increased likelihood of dialysis at nonprofit/independently owned facilities. In a multinomial model where the likelihood of patients who were safety-net reliant initiating dialysis at a given facility type was conditional upon the set of facility choices available to patients in each zip code, patients who were safety-net reliant remained more likely to initiate dialysis at nonprofit/independently owned facilities (RRR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.14 to 1.25) compared with reference facilities (i.e., for-profit/independently owned facilities), although the magnitude of the difference was smaller when compared with the primary multinomial model. Estimated differences in the likelihoods of dialysis at chain-owned facilities among patients who were safety-net reliant and those who were not safety-net reliant were no longer significantly different from reference facilities; the RRR for nonprofit/chain-owned facilities was 0.95 (95% CI, 0.90 to 1.00) and the RRR for for-profit/chain-owned facilities was 1.00 (95% CI, 0.96 to 1.03) (Figure 3; Supplemental Tables 4 and 5).

Regression Results: Hospital-based Affiliation

In a separate logistic regression model examining hospital-based affiliation, the odds of initiating dialysis at a hospital-based facility (relative to a free-standing facility) were 27% higher among patients who were safety-net reliant compared with patients who were not safety-net reliant (95% CI, 23% to 31%; Table 3). When we included hospital-based affiliation as an additional covariate in our primary multinomial regression model, the increased likelihood of dialysis at nonprofit/independently owned facilities among patients who were safety-net reliant remained significant (RRR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.15 to 1.30), although the magnitude of the difference was smaller.

Table 3.

Results from logistic regression model comparing the likelihood of dialysis at hospital-based and free-standing facility types among patients who are safety-net reliant versus other patients

| Covariates | Hospital-Based Facility |

|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

| Safety-net reliant | 1.27 (1.23 to 1.31) |

| Demographics | |

| Female | 0.99 (0.97 to 1.02) |

| Age - yr (<50 is referent) | |

| 50–65 | 0.77 (0.75 to 0.79) |

| Race (white is referent) | |

| Black | 0.74 (0.72 to 0.76) |

| American Indian | 1.73 (1.60 to 1.87) |

| Other | 0.90 (0.85 to 0.94) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 0.84 (0.82 to 0.87) |

| Health and socioeconomic | |

| Medical comorbidities (<2 is referent) | |

| 2 | 1.10 (1.07 to 1.14) |

| >2 | 1.31 (1.27 to 1.36) |

| Smokes | 1.12 (1.07 to 1.16) |

| Drug or alcohol abuse | 1.16 (1.10 to 1.22) |

| Immobility | 0.98 (0.93 to 1.03) |

| Median income - $10,000 | 1.06 (1.05 to 1.06) |

| Employed | 1.39 (1.35 to 1.43) |

| Geographic | |

| Population density (micropolitan is referent) | |

| Metropolitan | 0.49 (0.47 to 0.51) |

| Small town | 1.19 (1.12 to 1.26) |

| Rural | 1.73 (1.63 to 1.84) |

| HSA-level facility market competition (More competitive market is referent) | |

| Moderately competitive market | 0.30 (0.29 to 0.31) |

| Less competitive market | 0.12 (0.11 to 0.12) |

| Calendar yr (2008 is referent) | |

| 2009 | 0.90 (0.87 to 0.94) |

| 2010 | 0.80 (0.76 to 0.83) |

| 2011 | 0.74 (0.72 to 0.77) |

| 2012 | 0.69 (0.66 to 0.72) |

| 2013 | 0.48 (0.46 to 0.50) |

| 2014 | 0.43 (0.41 to 0.45) |

| 2015 | 0.47 (0.45 to 0.49) |

Includes 444,925 patients. HSA, hospital service area.

In a similar logistic regression model that conditioned upon the set of facility choices available to patients, the odds of initiating dialysis at a hospital-based facility were 19% higher among patients who were safety-net reliant compared with patients who were not safety-net reliant (95% CI, 15% to 23%; Supplemental Table 6). This suggests that a tendency of patients who are safety-net reliant to receive dialysis at hospital-based facilities, and closer proximity of nonprofit/independently owned facilities to patients who are safety-net reliant, can only explain part of the observed association between safety-net reliance and dialysis at nonprofit/independently owned facilities.

Analysis of Safety Net–Reliant Components

In an additional unconditional multinomial regression model (adjusted for baseline patient and geographic characteristics) where we assessed patients who were safety-net reliant with Medicaid only separately from those who were uninsured at the onset of dialysis, the RRR of dialysis at nonprofit/independently owned facilities was increased in both groups, but the magnitude of this association was substantially higher among the uninsured (RRR, 2.03; 95% CI, 1.86 to 2.22) versus Medicaid only (RRR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.10 to 1.21). In a similar multinomial model that conditioned upon the set of facility choices available to patients, nonprofit/independently owned facilities were no longer more likely to dialyze patients with Medicaid only (RRR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.94 to 1.04), but remained substantially more likely to dialyze patients without health insurance (RRR, 2.61; 95% CI, 2.37 to 2.88). We observed similar patterns when examining hospital affiliation.

Nonprofit/chain-owned facilities were less likely to care for patients with Medicaid only in both the unconditional multinomial model (RRR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.83 to 0.92) and in the model where facility assignment was conditional upon the set of nearby choices available to patients (RRR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.86 to 0.96). In contrast, nonprofit/chain-owned facilities were more likely to care for patients who were uninsured relative to reference facilities (RRR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.11 to 1.39) after accounting for the set of nearby choices available to patients (Supplemental Table 7).

Regression Results: Additional Analyses

Study findings from the primary unconditional multinomial and logistic regression models were not sensitive to the inclusion of patients who were ≥65 years old at dialysis initiation and the inclusion of home dialysis as an additional covariate. Observed associations between safety-net reliance and nonprofit/independent ownership and hospital affiliation became less pronounced over time (see Supplemental Appendices 4 and 5 for sensitivity analyses). Nonprofit/independently owned and hospital-affiliated facilities disproportionately cared for patients with more limited insurance under alternative specifications of safety-net reliance, but the magnitude of the increased risk was smaller (Supplemental Table 8).

Discussion

We found that 12% of patients under the age of 65 who initiated outpatient dialysis in the United States between 2008 and 2015 did not have health insurance or only had Medicaid at the onset of dialysis and did not become eligible for Medicare by their fourth month of dialysis (i.e., were safety-net reliant). In fully adjusted models, we found that independently owned/nonprofit dialysis facilities and hospital-based facilities cared for a disproportionately high share of patients who were safety-net reliant relative to other facility ownership types. When we examined these associations in more detail, we found that all of the increased likelihood of caring for patients with Medicaid only could be accounted for by geographic proximity to these patients, whereas the increased likelihoods of for-profit/independently owned and hospital-affiliated facilities caring for patients who were uninsured became more pronounced after accounting for the set of choices available to patients.

In its annual assessments, the Medicare Payment and Advisory Commission has consistently found that Medicare beneficiaries have access to maintenance dialysis.8 Similar assessments have not been conducted among those without Medicare or private health insurance. The many patients with ESKD who regularly rely on hospital emergency departments for dialysis to treat life-threatening complications of renal failure indicates that significant barriers to maintenance dialysis already exist for some patients.9–12 Our finding that independently owned/nonprofit dialysis facilities cared for a disproportionately high share of patients who are safety-net reliant relative to other facility ownership types suggest that these facilities have an important role in providing maintenance dialysis care for patients with limited health insurance.

A vast majority of independently owned/nonprofit facilities were categorized as hospital based, and we found that patients who were safety-net reliant were substantially more likely to initiate care at hospital-based facilities. This indicates that hospital-based facilities also have an important role in providing safety-net dialysis care in the United States, similar to core safety-net providers described in other areas of healthcare.4 Possible explanations for this role include increased dialysis referrals from associated safety-net hospitals and/or an organizational mission focused on providing access to care for underserved populations. Yet for several decades the share of nonprofit, hospital-based dialysis facilities has been declining in the United States.8 As these trends continue, it will be important for policy makers to find ways to ensure that patients who are safety-net reliant receive access to dialysis care.

The increased likelihoods of patients who were safety-net reliant initiating dialysis at independently owned/nonprofit and hospital-based facilities compared with patients with other insurance was most pronounced among patients who had no health insurance at the onset of dialysis. Increased reliance on certain facility types for maintenance dialysis could explain previous findings that uninsured populations are at increased risk for care disruptions and negative health consequences in the setting of barriers to maintenance dialysis care.13,25,26

Compared with patients with more stable health insurance, patients who were safety-net reliant were younger, more likely to live in poorer areas, were less likely to be employed, and were more likely to be members of racial and ethnic minorities. They were also more likely to live in areas with higher population density. This is consistent with a study of patients with Medicaid-only insurance receiving dialysis in three states in the 1990s and with surveys of safety-net reliance in the general population in the United States.13,27

The proportion of patients receiving maintenance dialysis who were uninsured or only had state Medicaid was small compared with many other healthcare settings. Nearly 10% of the United States population has no health insurance, and >20% of American adults under the age of 65 depend on Medicaid coverage.28 Although it is not uncommon for the majority of patients treated at safety-net hospitals to be uninsured or to only have Medicaid,4,6 only 12% of those <65 years old receiving maintenance dialysis were safety-net reliant. Even among dialysis facilities in the top quartile of safety-net care, only 32% of their populations were safety-net reliant.

One possible explanation for this discrepancy between the magnitudes of safety-net reliance in the general population compared with the maintenance dialysis population includes an exemption of outpatient dialysis facilities from the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act—the federal law that requires hospital emergency departments to stabilize or transfer all patients with medical emergencies, regardless of their abilities to pay. Additionally, mortality is very high among patients initiating maintenance dialysis,29 and those who face barriers to dialysis care are even less likely to survive, which could reduce the observed size of the safety net–reliant population. In general, adults do not become eligible for Medicare’s near-universal coverage for patients with ESKD if they (or their spouse) have not paid 40 quarters of Medicare payroll taxes or if they do not satisfy legal residency criteria. These circumstances are relatively uncommon and may explain both the relatively small number of patients who are safety-net reliant and the higher proportions of younger and unemployed patients within this population.

Results of the unconditional multinomial regression model indicate that for-profit and nonprofit chains cared for disproportionately fewer patients who were safety-net reliant relative to the reference group (for-profit/independently owned facilities). However, these differences disappeared or were no longer statistically significant after accounting for the set of nearby dialysis facilities from which each patient could choose.

Interestingly, when we accounted for the set of nearby dialysis facilities from which patients could choose, nonprofit/chain-owned facilities were more likely to care for patients without insurance who never became eligible for Medicare but were less likely to care for patients with Medicaid only. This suggests that nonprofit chains may have a role in providing safety-net care in some settings, similar to their role in providing safety-net care in other areas of healthcare.4 However, in other aspects (such as where to locate dialysis facilities), nonprofit chains appear more similar to their for-profit counterparts. This latter finding is consistent with economic theories predicting similar profit maximizing behavior among nonprofit and for-profit organizations.30

Despite a relative increase in the likelihood of patients who were safety-net reliant receiving care from more traditional hospital-based, safety net–provider types, we also found that chain-owned and for-profit dialysis facilities play a major role in the current delivery of maintenance dialysis to patients who are safety-net reliant in the United States. For-profit/chain-owned facilities provide care for about 73% of such patients, whereas for-profit/independently owned facilities care for about 10% of patients who are safety-net reliant. For-profit organizations serve a significant role in the provision of safety-net care in some healthcare settings outside of dialysis.4 However, the overall magnitude of their role in providing safety-net dialysis care delivery is unique.

Our study has several limitations. Because our data only included patients who were able to receive maintenance dialysis in the outpatient setting, we were unable to describe the full extent to which patients face difficulties accessing this care. Importantly, we could not determine how many patients with late-stage kidney disease die because of limited access to maintenance dialysis care and how many patients receive dialysis care through emergency departments. Our data did not enable us to determine the extent to which patients who were uninsured acquired public insurance (such as Medicaid) or private nongroup insurance (e.g., from the Health Insurance Marketplace) after initiating dialysis, and our analysis relied on reporting from the CMS-2728 form, which can be inconsistent in some areas. One survey of eastern states found that Medicaid reimbursement for the dialysis procedure was, in many instances, comparable to Medicare reimbursement.31 Although this suggests that factors other than differences in health insurance reimbursement influence the types of facilities where patients with Medicaid receive care, we did not examine why patients who were safety-net reliant in a given location were more likely to receive care at certain facility types. In a sensitivity analysis we found that associations between safety-net reliance and the likelihood of initiating dialysis at certain facilities changed over time. As the landscape of dialysis care evolves, it will be important to better understand these changes. Finally, limited information about health insurance after the initiation of dialysis prevented us from examining specific changes in the composition of the safety net–reliant population after passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in 2010, which has altered the landscape of safety-net care in the United States6 and may have increased Medicaid coverage among some vulnerable populations.32,33

In summary, we found that patients who are safety-net reliant comprise a relatively small, but growing, proportion of the maintenance dialysis population in the United States. For-profit/chain-owned facilities are a critical part of the dialysis safety-net provider network due to their predominant role in providing outpatient dialysis care. Yet independently owned nonprofit facilities (which are primarily affiliated with hospitals) provide a disproportionate share of safety-net dialysis care due to both their proximity to safety net–reliant populations and the process of dialysis facility selection and/or assignment. Their roles as safety-net providers may be particularly important for patients with no health insurance. As ongoing trends in the United States toward increased for-profit and chain-owned dialysis facilities persist, it will be important to monitor the extent to which safety net–reliant populations are able to access maintenance dialysis care.

Disclosures

Dr. Chertow reports personal fees from Akebia; personal fees from Angion; personal fees from Amgen; personal fees and other from Ardelyx; personal fees from AstraZeneca; personal fees from Baxter; personal fees from Bayer; other from Cricket: personal fees from DiaMedica; other from Durect; other from DxNow; personal fees from Gilead; other from Outset; personal fees from Reata; personal fees from ReCor; personal fees from Sanifit; personal fees from Satellite Healthcare, during the conduct of the study; and personal fees from Vertex, outside the submitted work. Dr. Erickson reports personal fees from Acumen LLC, outside the submitted work. Dr. Ho is a board member of Community Health Choice. Dr. Shen reports grants from National Institutes of Health/NIDDK, during the conduct of the study. Dr. Winkelmayer reports personal fees from Akebia, personal fees from Amgen, personal fees from AstraZeneca (ZS Pharma), personal fees from Bayer, personal fees from Janssen, personal fees from Relypsa, and personal fees from Vifor FMC Renal Pharma, outside the submitted work.

FUNDING

Dr. Erickson received funding for this project from National Institutes of Health/NIDDK grant (1K23DK101693-01).

Supplementary Material

Data Sharing Statement

This work was conducted under a data use agreement between Dr. Winkelmayer and the National Institutes for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). An NIDDK officer reviewed the manuscript and approved it for submission. The data reported here have been supplied by the USRDS. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the US Government.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

See related editorial, “The Dialysis Safety Net: Who Cares for Those Without Medicare?” on pages 238–240.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2019040417/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Appendix 1. Chain ownership.

Supplemental Appendix 2. Measuring competition.

Supplemental Appendix 3. Conditional logit model.

Supplemental Appendix 4. Sensitivity analyses.

Supplemental Appendix 5. Analysis of facility switch rates.

Supplemental Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients stratified by facility ownership type.

Supplemental Table 2. Baseline characteristics of patients stratified by hospital affiliation.

Supplemental Table 3. Characteristics of dialysis facilities, stratified by proportion of safety-net reliant patients.

Supplemental Table 4. Baseline characteristics of the population under 65 years old included in conditional logit model based on patient zip-codes.

Supplemental Table 5. Regression results of multinomial logit model conditional upon the set of dialysis facility ownership choices available within a given zip-code.

Supplemental Table 6. Regression results of logistic regression model conditional upon the set of dialysis facility choices (Hospital-based versus free-standing) available within a given zip-code.

Supplemental Table 7. Results of analyses examining each component of safety-net reliance.

Supplemental Table 8. Results of analyses of alternative specifications of safety-net reliance.

Supplemental Figure 1. Proportion of patients with medicaid or no health insurance who do not receive medicare or private group insurance at each day following dialysis initiation.

Supplemental Figure 2. Distribution of proportion of patients who are safety-net reliant stratified by facility ownership type.

Supplemental Figure 3. Distribution of proportion of patients who are safety-net reliant stratified by facility hospital affiliation.

Supplemental Figure 4. Absolute probability of initiating dialysis at different facility types by health insurance category.

References

- 1.Cook NL, Hicks LS, O’Malley AJ, Keegan T, Guadagnoli E, Landon BE: Access to specialty care and medical services in community health centers. Health Aff (Millwood) 26: 1459–1468, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calvin JE, Roe MT, Chen AY, Mehta RH, Brogan GX Jr., Delong ER, et al.: Insurance coverage and care of patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Ann Intern Med 145: 739–748, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maryland Association of Certified Public Accountants Commission : Report to congress on medicaid and CHIP, Washington, DC, United States Congress, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of Medicine : America’s Health Care Safety Net Intact but Endangered, Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gresenz CR, Rogowski J, Escarce JJ: Health care markets, the safety net, and utilization of care among the uninsured. Health Serv Res 42: 239–264, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chokshi DA, Chang JE, Wilson RM: Health reform and the changing safety net in the United States. N Engl J Med 375: 1790–1796, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Redlener I, Grant R: America’s safety net and health care reform--what lies ahead? N Engl J Med 361: 2201–2204, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission : March 2018 Report to Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Washington, DC, Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuruvilla R, Raghavan R: Health care for undocumented immigrants in Texas: Past, present, and future. Tex Med 110: e1, 2014 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coritsidis GN, Khamash H, Ahmed SI, Attia AM, Rodriguez P, Kiroycheva MK, et al.: The initiation of dialysis in undocumented aliens: The impact on a public hospital system. Am J Kidney Dis 43: 424–432, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raghavan R, Nuila R: Survivors--dialysis, immigration, and U.S. law. N Engl J Med 364: 2183–2185, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell GA, Sanoff S, Rosner MH: Care of the undocumented immigrant in the United States with ESRD. Am J Kidney Dis 55: 181–191, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thamer M, Ray NF, Richard C, Greer JW, Pearson BC, Cotter DJ: Excluded from universal coverage: ESRD patients not covered by Medicare. Health Care Financ Rev 17: 123–146, 1995 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.caUSCr: Social Security Amendments of 1972, Pub. L. No. 92-603, Section 299I, 1972

- 15.United States Renal Data System : 2016 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erickson KF, Zheng Y, Winkelmayer WC, Ho V, Bhattacharya J, Chertow GM: Consolidation in the dialysis industry, patient choice, and local market competition. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 536–545, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice : Selected Hospital and Physician Capacity Measures, Lebanon, NH, The Trustees of Dartmouth College, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 18.U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes (RUCA), Washington DC, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker LC, Bundorf MK, Royalty AB, Levin Z: Physician practice competition and prices paid by private insurers for office visits. JAMA 312: 1653–1662, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kessler DP, McClellan MB: Is hospital competition socially wasteful? Q J Econ 115: 577–615, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee DK, Chertow GM, Zenios SA: Reexploring differences among for-profit and nonprofit dialysis providers. Health Serv Res 45: 633–646, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.US Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission : Horizontal Merger Guidelines, Washington, DC, US Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 23.McFadden D: Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior. In: Frontiers in Econometrics, edited by Zarembka P, New York, NY, Academic Press, 1974, pp 105–142 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erickson KF, Zheng Y, Ho V, Winkelmayer WC, Bhattacharya J, Chertow GM: Market competition and health outcomes in hemodialysis. Health Serv Res 53: 3680–3703, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Devlin A, Waikar SS, Solomon DH, Lu B, Shaykevich T, Alarcón GS, et al.: Variation in initial kidney replacement therapy for end-stage renal disease due to lupus nephritis in the United States. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 63: 1642–1653, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perez JJ, Zhao B, Qureshi S, Winkelmayer WC, Erickson KF: Health insurance and the use of peritoneal dialysis in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 71: 479–487, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schoen C, Collins SR, Kriss JL, Doty MM: How many are underinsured? Trends among U.S. adults, 2003 and 2007. Health Aff (Millwood) 27: w298–w309, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Center for Health Statistics : Health, United States, 2016 - Individual Charts and Tables, Atlanta, GA, US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 29.United States Renal Data System : 2017 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Darius L, Tomas P: The nonprofit sector and industry performance. J Public Econ 90: 1681–1698, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Commonwealth of Virginia Department of Medical Assistance Services : History of Medicaid Reimbursement Rates for Dialysis In Virginia, Richmond, VA, Virginia Department of Medical Assistance Services, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trivedi AN, Sommers BD: The affordable care act, medicaid expansion, and disparities in kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 480–482, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iglehart JK: The ACA opens the door for two vulnerable populations. Health Aff (Millwood) 33: 358, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.