Abstract

Inducible T cell costimulator (ICOS, cluster of differentiation (CD278)) is an activating costimulatory immune checkpoint expressed on activated T cells. Its ligand, ICOSL is expressed on antigen-presenting cells and somatic cells, including tumour cells in the tumour microenvironment. ICOS and ICOSL expression is linked to the release of soluble factors (cytokines), induced by activation of the immune response. ICOS and ICOSL binding generates various activities among the diversity of T cell subpopulations, including T cell activation and effector functions and when sustained also suppressive activities mediated by regulatory T cells. This dual role in both antitumour and protumour activities makes targeting the ICOS/ICOSL pathway attractive for enhancement of antitumour immune responses. This review summarises the biological background and rationale for targeting ICOS/ICOSL in cancer together with an overview of the principal ongoing clinical trials that are testing it in combination with anti-cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 and anti-programmed cell death-1 or anti-programmed cell death ligand-1 based immune checkpoint blockade.

Keywords: ICOS, ICOSL, immune checkpoint blockade, tumour microenvironment

Introduction

Immune responses are tightly regulated by a variety of coinhibitory and costimulatory pathways that can be targeted in cancer immunotherapy. Using agonistic or antagonistic antibodies (Abs) to manipulate normal immune regulatory pathways, it has been shown that this can reinvigorate or generate de novo memory immune responses to the tumour. This memory then functions to recognise over the long-term circulating, disseminated or residual tumour cells expressing tumour-associated antigens (Ags). Remarkable benefit from immunotherapy has been observed in specific subsets of cancer patients, highlighting the need to optimise patient selection for treatments as well as improve their effectiveness and activity in different settings to broaden the patient population deriving benefit.

Cancer immunotherapy challenges clinicians not only for the differential diagnosis and management of patients1–3 but also for the new spectra of emerging and potentially long-lasting toxicities it induces.1–3 In addition, the timing for optimal assessment of responses are variable,4 different organ sites may have peculiar patterns5 and abscopal effects can occur6 with responses obtained in non-irradiated sites after radiotherapy (RT). Another research priority is to overcome resistance to cancer immunotherapy7 and further potentiate its activity and effectiveness by using combinational approaches. Currently, a variety of combinations use the established anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte Ag-4 (CTLA-4) and anti-programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1) Abs with other treatments, including chemotherapy, targeted therapy, RT and other immune checkpoint modulators.

The inducible costimulator (ICOS or cluster of differentiation (CD278)) of T cells and its ligand (ICOSL) play important roles in memory and effector T cell development and specific humoral immune responses. Although their role in cancer is still a subject of investigation, this pathway has been shown to potentiate immunosuppression mediated by some CD4+ T cell subsets, such as regulatory T cells (Tregs).8 Interactions between ICOS and ICOSL can have antitumour effects as increases in both CD4+ICOS+ and CD8+ICOS+ T cell subpopulations, which paralleled an increased ratio of effector T cells (Teff)/Tregs in the tumour microenvironment (TME), were observed in patients treated with anti-CTLA-4 Ab.8 Thus, a potential role for this pathway in improving the effectiveness of cancer immunotherapy is being investigated in early phase trials using agonistic or antagonistic Abs administered alone or more often in combination with other immunotherapeutic treatments.

The aim of this review is to summarise the biological background and rationale for targeting the ICOS/ICOSL pathway in tumours, as well as the principal ongoing trials testing it in combination with anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 based immune checkpoint blockade (ICB).

ICOS biology

ICOS, first identified in humans 20 years ago, is the third member of the CD28 coreceptor family, which are all involved in regulating T cell activation and adaptive immune responses.9 ICOS has significant homology with the other two family members, costimulatory CD28 and coinhibitory receptor CTLA-4. Furthermore, T cells costimulated by ICOS can achieve levels of activation comparable to CD28. ICOS signals induce production of a wide spectra of cytokines by CD4+ T helper (Th) cells, CD4+ forkhead box P3 (FoxP3+) Tregs and CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) that function to enhance their proliferation and direct memory cell development (figure 1).

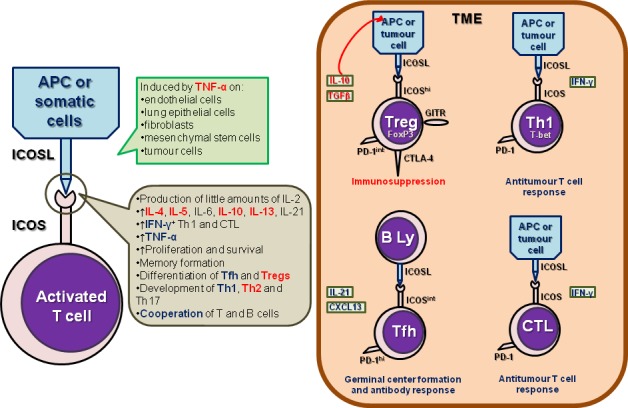

Figure 1.

Biology of ICOS in the tumour microenvironment. ICOS is expressed by different T lymphocyte subpopulations, comprising CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL), CD4+ helper T cells (Th), including Th1, Th2, Th17 and follicular helper T (Tfh) cells and CD4+ FoxP3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs). Its main ligand, ICOSL is expressed by antigen-presenting cells (APCs, including B lymphocytes) and by somatic (including tumour) cells. The interaction between ICOS and ICOSL has agonistic/stimulating activities, promoting an antitumour response by Th1, CTL and Tfh and of a protumour response mediated by Tregs and Th2 in the tumour microenvironment. Figure represents the crosstalk between ICOS+ T cell subsets and ICOSL-expressing cells and the effects of ICOS/ICOSL interaction. In red: protumour activities or effects; in blue: antitumour activities or effects.

Unlike CD28, which is constitutively expressed on both naïve and a majority of memory T cells, ICOS expression is induced after activation with only a small fraction of resting memory T cells expressing it at low levels. ICOSL, the unique ligand of ICOS, is constitutively expressed by professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs), including B cells, macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs).10 In contrast to the restriction of the CD28 and CTLA-4 ligands (CD80 and CD86) largely to lymphoid tissues, ICOSL is widely expressed on somatic cells (figure 1). It can be induced by tumour necrosis factor-α on many non-lymphoid cells including endothelial cells, lung epithelial cells, fibroblasts, mesenchymal stem cells and tumour cells.11–15

ICOS costimulation, in contrast to the CD28 pathway, results in inefficient IL-2 production by activated T cells; however, other cytokines including IL-4, IL-10 and IL-21 are often more efficiently induced (figure 1).9 16 This confers a specific role for ICOS in regulating Th cell subset differentiation in the early stages of activation. The requirement for ICOS signalling has been most studied in Treg and follicular Th cell (Tfh) differentiation. ICOS is highly expressed on human tonsillar PD-1hi CXCR5hi Tfh, whose function is to promote high-affinity Ag-specific B cell responses (figure 1). In the peripheral blood, CD25hiFoxP3+ Tregs express the highest levels of ICOS with ICOS+ circulating Tfh a subpopulation shown increased in autoimmune diseases.17 Furthermore, the differentiation of the Th2 and Th17 subpopulations is also dependent on ICOS and ICOS costimulation can efficiently induce Th1 cytokine expression. In mouse models of infection, ICOS deficiency or ICOS/ICOSL signalling disruption using blocking Abs can either reduce or increase IFN-γ+ Th1 and thereby have an effect on both Th1 and Tregs.18

In human cancer, ICOS expression on FoxP3+ Tregs is well established. In comparison to their counterparts in the periphery, Treg tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) express increased levels of FoxP3 and several other markers including CTLA-4, glucocorticoid-induced TNFR family related gene and ICOS in addition to secreting higher levels of IL-10 and TGFβ (figure 1). ICOShi Tregs isolated from melanoma had superior immunosuppressive activities compared with ICOSlo Tregs and were capable of converting CD4+CD25– T cells (non-Tregs) into IL-10 expressing suppressive type-1 regulatory T cells (Tr1).19 Freshly isolated ICOS+ Tregs also displayed high proliferation (Ki67) rates, indicating in vivo activation at the tumour site.20 21 Plasmacytoid pre-DCs (pDCs) are particularly poised to express ICOSL upon maturation and regulate T cell IL-10 expression.22 Through ICOS/ICOSL interactions, tumour-infiltrating pDCs or tumour cells themselves can support local Treg survival and sustain FoxP3 expression as well as IL-10 production.13 20 23 In gastric cancer, despite a decrease in total FoxP3+ Tregs in parallel with intensifying tumour stages, the ICOS+ subset persisted and ICOS+ Treg TIL were associated with shorter survival.24 In primary and secondary liver tumours, a significant Tr1 presence was detected and correlated with intratumoral pDC abundance.25 Similarly, ICOSL signalling from pDCs was shown to be critical for IL-10 induction in lymphocyte-associated gene 3+FoxP3– CD4+ TIL, indicating a functional role of pDCs in generating Tr1 through ICOS activation.

In addition to regulatory TIL populations, a few studies have linked ICOS expression to other Th subsets infiltrating human tumours. Dominant ICOS expression was detected on Th1 TIL expressing the Th1 transcription factor T-bet and producing IFN-γ in colorectal cancer.14 Further, they found that high levels of ICOS expression were associated with improved clinical outcomes and ICOSL was highly expressed on macrophages. In breast cancer (BC), our studies revealed that activated Treg TIL express high levels of ICOS (ICOShi) and intermediate levels of PD-1 (PD-1int), while PD-1 high (PD-1hi) effector CD4+ TIL (including CXCL13+IL21+ Tfh) express intermediate levels of ICOS (ICOSint) (figure 1).21 Both populations are characterised by prominent proliferation and are positively correlated with one another, except for a few tumours containing unbalanced, high levels of Tregs. ICOS expression on CD8+ TIL is less intense than on CD4+ TIL, due to the absent versus low expression of FoxP3. Interestingly, we found that PD-1hiICOSint CD8+ BC TIL are similar to their CD4+ counterparts and notably express CXCL13 (Gu-Trantien, unpublished observation; Noël et al, manuscript in preparation). ICOS ligation is also critical for generating polyfunctional IFN-γ-coexpressing human Th17 that are capable of mediating effective antitumour functions.26

ICOS was also shown to be an important element in the persistence of CD4+ chimeric Ag receptor (CAR) T cells, a form of passive immunotherapy which is currently in use in clinical trials, particularly for haematological malignancies.27 A recent study demonstrated that the intracellular signalling domain of ICOS could enhance the in vivo persistence of CD4+ CAR T cells, which in turn maintain CD8+ T cells in mouse tumour models.28 The most effective antitumour activity was reached when ICOS was coupled with the intracellular signalling domain of the costimulatory receptor 4-1BB in CAR T cells.

Targeted agents under development

The ICOS/ICOSL axis has been shown to promote either antitumour T cell responses (when activated in Th1 and other Teff) or protumour responses when triggered in Tregs. Therefore, both agonistic and antagonistic monoclonal Abs (mAbs) targeting this pathway are being investigated for cancer immunotherapy (table 1).29–31

Table 1.

Compounds targeting ICOS currently under clinical investigation

| Name | Characteristics | Clinical trial phase | Company |

| Anti-ICOS agonists | |||

| GSK3359609 | Anti-ICOS agonist monoclonal antibody (humanised IgG4) | Phase I, II | GlaxoSmithKline |

| JTX-2011 | Anti-ICOS agonist monoclonal antibody (humanised) | Phase I | Jounce Therapeutics |

| Anti-ICOS antagonists | |||

| MEDI-570 | Anti-ICOS monoclonal antibody (Fc-optimised humanised IgG1) | Phase I | National Cancer Institute (NCI) |

| KY1044 | Anti-ICOS monoclonal antibody (fully human) IgG1κ | Phase I/II | Kymab Limited |

Fc, fragment crystallisable; ICOS, inducible T cell costimulator.

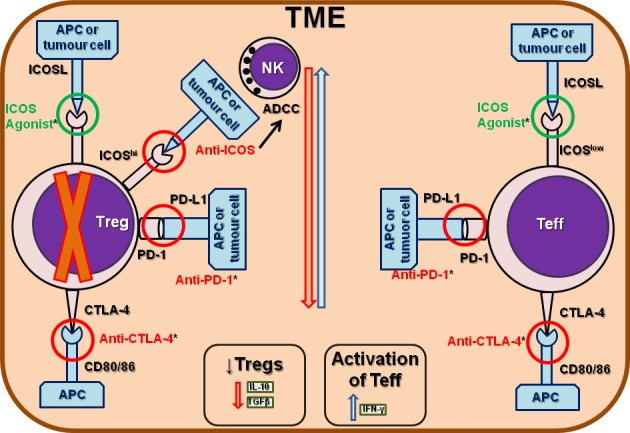

In preclinical studies, ICOS agonistic mAbs potentiate the effects of anti-CTLA-4. ICOS knockout mice do not respond well to anti-CTLA-4,32 suggesting that ICOS signalling is required for effective antitumour responses, likely mediated by Teff (figure 2). Thus, concomitant CTLA-4 and ICOS stimulation had a superior antitumour effect compared with anti-CTLA-4 alone.33 Interestingly, mice and patients treated with anti-CTLA-4 or anti-PD-1 expanded the ICOShi (FoxP3–) CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subpopulations, signalling a treatment benefit33–40 with ICOShi T cells potentially an important biomarker for clinical response.39 41 ICOS alone appears to be less potent compared with other pathways targeted by cancer immunotherapies, primarily because of the predominance of CD4+ Tregs. Using ICOS agonistic or antagonistic Abs in combination with CTLA-4 or PD-1/PD-L1 has the potential to generate potent synergistic effects (figure 2).33 42

Figure 2.

Targeting regulatory and/or effector T cells with ICOS agonistic or antagonistic antibodies. ICOS can be targeted by either agonist (in green) and antagonistic (in red) antibodies (Abs). ICOS agonists are usually administered in concomitance with anti-CTLA-4 or anti-PD-1 Abs, for their ability to synergistically inhibit the suppressive activity of regulatory T cells (Tregs) and to potentiate the antitumour activity of effector T cells (Teff), including CD4+ and CD8+ subpopulations. One main mechanism of action of ICOS antagonistic Abs is to inhibit Tregs by stimulating the antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) mediated by natural killer (NK) cells. CTLA-4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte Ag-4; PD-1, programmed cell death-1.

The first-in-human trial, INDUCE-1 (NCT02723955), used an ICOS agonist Ab administered alone (part 1) or in combination with an anti-PD-1 (pembrolizumab; part 2) in patients with advanced solid tumours and had promising results in terms of tolerability, toxicity profile and clinical activity.43 The most frequent treatment-related adverse events (AEs) were: fatigue (15%), fever (8%), elevation of hepatic enzymes (5%, representing also the most frequent grade 3–4 AE) and diarrhoea (3%). One dose limiting grade 3 pneumonitis occurred.44 The ICONIC trial (NCT02904226) investigated the role of an ICOS agonist Ab (JTX-2011) given alone (mono arm) or in combination with an anti-PD-1 (nivolumab; combo arm) in patients with relapsed/refractory tumours. Currently, the data show this compound is safe, well tolerated and can generate antitumour responses in heavily pretreated gastric cancer and triple-negative BC patients. The most common dose limiting toxicities were an increase in the hepatic enzymes and pleural effusion in patients from the mono arm. Grade 3–4 drug-related AEs were 8% in the mono, 13% in the combo; immune-related AEs were 4% in the mono, 21% in the combo; infusion-related AEs were 12% in the mono and 19% in the combo. Interestingly, peripheral blood CD4+ICOShi T cell subpopulations appear to be a promising biomarker of response.45

ICOS antagonistic Abs have shown limited antitumour activity via their abrogation of Treg-mediated immune suppression and thereby potentially enhancing CTL-mediated immune responses directed to tumour cells. These compounds principally prevent interactions between ICOS+ T cells (particularly CD4+ Tregs) and ICOSL+ pDCs. Their principal activity is to prevent pDC-induced proliferation, the accumulation of ICOShi Tregs and inhibit IL-10 secretion by CD4+ T cells. Noteworthy, fragment crystallisable optimisation has the advantage of inducing antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity.46

Overall, these data indicate that the ICOS pathway plays a critical role in effective responses to anti-CTLA-4 and perhaps other ICB agents. Similar to T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3, ICOS mAbs are unlikely to be used as monotherapy because they do not independently induce cytotoxic immune responses.47

Current ongoing clinical trials

Agonistic Abs are currently being administered either alone (NCT03447314, NCT02904226) or in combination with immunotherapy, including ICB as well as with chemotherapy (NCT03693612, NCT03447314, NCT02723955, NCT03739710, NCT02904226). In one trial, the anti-ICOS mAb MEDI-570 is being tested alone (NCT02520791), while in another, the anti-ICOS Ab KY1044 (NCT03829501) is being tested alone (phase I and II arms) or in combination with an PD-L1-based ICB (also phase I and II arms) (table 2). The principal mechanisms of action by either ICOS agonists or antagonists are shown in figure 2. A summary of the early phase ongoing clinical trials is provided in table 2.

Table 2.

Clinical trials testing ICOS targeting antibodies in a variety of tumour types

| ClinicalTrial.gov identifier | Tumour type | Setting | Phase | Treatment arms | Target accrual |

| Anti-ICOS agonists | |||||

| NCT03693612 (GSK3359609) |

Advanced solid tumours (phase I); RR-HNSCC (phase II) | Advanced (phase I); RR (phase II) | I/II | Part 1: GSK3359609 plus anti-CTLA-4 tremelimumab; Part 2: GSK3359609 plus tremelimumab versus active comparators → single agent standard of care (docetaxel or paclitaxel or cetuximab) | 115 |

| NCT03447314 (GSK3359609) |

Advanced solid tumours; recurrent, locally advanced or metastatic HNSCC | Advanced; recurrent, locally advanced or metastatic | I | Part 1B: GSK3359609 plus TLR-4 agonist GSK1795091; Part 1: PK/Pharmacodynamic cohort (GSK1795091; GSK3174998; GSK3359609; anti-PD-1 pembrolizumab); Part 2B: GSK1795091 plus GSK3359609 | 162 |

| NCT02723955 (INDUCE-1) (GSK3359609) |

Advanced solid tumours including: bladder/urothelial cancer of the upper and lower urinary tract; cervical; colorectal; esophageal, squamous cell; HNSCC; melanoma; malignant pleural mesothelioma; NSCLC; prostate; Microsatellite Instability-High/deficient mismatch repair tumour (Part 1B and Part 2B) and Human Papilloma Virus-positive or Epstein-Barr-positive tumour (Part 1B and Part 2B) | Locally advanced/metastatic or RR | I | Part 1A (dose escalation): GSK3359609; Part 1B (expansion): GSK3359609; Part 2A (dose escalation/safety run-in GSK3359609): GSK3359609; OX40 agonist GSK3174998; anti-PD-1 pembrolizumab; docetaxel; pemetrexed plus carboplatin; paclitaxel plus carboplatin; gemcitabine plus carboplatin; fluorouracil plus carboplatin or cisplatin; Part 2B (expansion-GSK3359609): GSK3359609 plus fluorouracil (5-FU) plus carboplatin or cisplatin plus pembrolizumab | 500 |

| NCT03739710 | RR advanced NSCLC | RR advanced (previous first or second line of anti-PD-1/L1 allowed) | II | GSK3359609 plus docetaxel versus docetaxel | 105 |

| NCT02904226 (ICONIC) (JTX-2011) |

Advanced and/or refractory solid tumours | Advanced and/or refractory | I/II | Part A: JTX-2011; Part B: JTX-2011 plus anti-PD-1 nivolumab; Part C: JTX-2011; Part D: JTX-2011 plus nivolumab; Part E: JTX-2011 plus anti-CTLA-4 ipilimumab; Part F: JTX-2011 plus ipilimumab; Part G: JTX-2011 plus anti-PD-1 pembrolizumab; Part H: JTX-2011 plus pembrolizumab | 498 |

| Anti-ICOS antagonists | |||||

| NCT02520791 (MEDI-570) |

RR peripheral T-cell lymphoma-not otherwise specified; angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma; follicular lymphoma: mycosis fungoides; cutaneous T-cell lymphoma | RR | I | MEDI-570 | 46 |

| NCT03829501 (KY1044) |

Advanced tumours (NSCLC, HNSCC, hepatocellular carcinoma, melanoma, cervical, esophageal, gastric, renal, pancreatic, and triple-negative BC; advanced cancer) |

Advanced | I/II | Experimental phase I: KY1044; experimental phase I: KY1044 plus anti-PD-L1 atezolizumab; experimental phase II: KY1044; experimental phase II: KY1044 plus anti-PD-L1 atezolizumab | 412 |

BC, breast cancer;CTLA-4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte Ag-4; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer;PD-1, programmed cell death-1; PD-L1, programmed cell death – ligand 1; RR, relapsed/refractory; TLR, toll-like receptor.

Conclusions

The remarkable benefits observed by targeting the principal inhibitory regulatory pathways of the immune response in a variety of haematological and solid tumours, including CTLA-4 and particularly PD-1 and PD-L1, have stimulated investigation of new targets associated with alternative, non-redundant modulatory immune checkpoints, including ICOS/ICOSL. The emergence of resistance to the initial drugs has paved the way for combination strategies using more than one immunomodulatory agent. The most active/successful combination thus far is anti-CTLA-4 plus anti-PD-1, despite their association with a significant increase in high grade toxicities. A multitude of new approaches are being considered and implemented in clinical trials. Targeting the ICOS/ICOSL pathway holds considerable promise primarily because of its role in modulating Treg/Teff functions, including inhibiting Treg interactions with ICOSL (ICOS antagonists) or potentiating anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 mAbs activities (ICOS agonists). The ICOS/ICOSL pathway can also modulate antitumour Teff responses by specifically modulating Th1 and CTL activities. Early phase clinical trials testing ICOS agonist Abs in patients with advanced solid tumours have shown good safety profiles and promising antitumour activities, particularly when the compounds are given as a combination with anti-PD-1 agents (pembrolizumab and nivolumab). Dose-limiting toxicities were not common occurrences, reinforcing these agents as promising new targets for combination cancer immunotherapy.

A variety of questions concerning targeting ICOS/ICOSL pathway in cancer immunotherapy remain unanswered. Studies are needed to understand how, at the fundamental level, targeting ICOS/ICOSL interactions impacts immune responses, including the generation of CD4+, CD8+ and B cell memory immune responses in tumour-associated tertiary lymphoid structures. In addition, more clinical information is needed on the optimal ICB target (anti-CTLA-4 versus anti-PD-1/PD-L1) for combination with ICOS/ICOSL, the identification of biomarkers for patient selection and the potential for combination with additional targets. More mature preliminary data from the current ongoing clinical trials should help to address some of these issues.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr David Gray for assistance in writing in English.

Footnotes

CS and CG-T contributed equally.

Contributors: CS and CG-T did the bibliographic research and wrote the article. KW-G wrote the article and supervised the entire process.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Solinas C, Porcu M, De Silva P, et al. Cancer immunotherapy-associated hypophysitis. Semin Oncol 2018;45:181–6. 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2018.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Porcu M, De Silva P, Solinas C, et al. Immunotherapy associated pulmonary toxicity: biology behind clinical and radiological features. Cancers 2019;11:E305 10.3390/cancers11030305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Haanen JBAG, Carbonnel F, Robert C, et al. Management of toxicities from immunotherapy: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2018;29:iv264–6. 10.1093/annonc/mdy162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Solinas C, Porcu M, Hlavata Z, et al. Critical features and challenges associated with imaging in patients undergoing cancer immunotherapy. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2017;120:13–21. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2017.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Porcu M, Solinas C, Garofalo P, et al. Radiological evaluation of response to immunotherapy in brain tumors: where are we now and where are we going? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2018;126:135–44. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2018.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hlavata Z, Solinas C, De Silva P, et al. The Abscopal effect in the era of cancer immunotherapy: a spontaneous synergism boosting anti-tumor immunity? Target Oncol 2018;13:113–23. 10.1007/s11523-018-0556-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sharma P, Hu-Lieskovan S, Wargo JA, et al. Primary, adaptive, and acquired resistance to cancer immunotherapy. Cell 2017;168:707–23. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.01.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Marinelli O, Nabissi M, Morelli MB, et al. ICOS-L as a potential therapeutic target for cancer immunotherapy. Curr Protein Pept Sci 2018;19:1107–13. 10.2174/1389203719666180608093913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hutloff A, Dittrich AM, Beier KC, et al. Icos is an inducible T-cell co-stimulator structurally and functionally related to CD28. Nature 1999;397:263–6. 10.1038/16717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yoshinaga SK, Whoriskey JS, Khare SD, et al. T-Cell co-stimulation through B7RP-1 and ICOS. Nature 1999;402:827–32. 10.1038/45582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Swallow MM, Wallin JJ, Sha WC. B7h, a novel costimulatory homolog of B7.1 and B7.2, is induced by TNFα. Immunity 1999;11:423–32. 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80117-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Khayyamian S, Hutloff A, Büchner K, et al. ICOS-ligand, expressed on human endothelial cells, costimulates Th1 and Th2 cytokine secretion by memory CD4+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002;99:6198–203. 10.1073/pnas.092576699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Martin-Orozco N, Li Y, Wang Y, et al. Melanoma cells express ICOS ligand to promote the activation and expansion of T-regulatory cells. Cancer Res 2010;70:9581–90. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang Y, Luo Y, Qin S-L, et al. The clinical impact of ICOS signal in colorectal cancer patients. Oncoimmunology 2016;5:e1141857 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1141857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lee H-J, Kim S-N, Jeon M-S, et al. ICOSL expression in human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells promotes induction of regulatory T cells. Sci Rep 2017;7:44486 10.1038/srep44486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gigoux M, Shang J, Pak Y, et al. Inducible costimulator promotes helper T-cell differentiation through phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106:20371–6. 10.1073/pnas.0911573106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schmitt N, Bentebibel S-E, Ueno H. Phenotype and functions of memory Tfh cells in human blood. Trends Immunol 2014;35:436–42. 10.1016/j.it.2014.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wikenheiser DJ, Stumhofer JS. Icos co-stimulation: friend or foe? Front Immunol 2016;7:304 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Strauss L, Bergmann C, Szczepanski MJ, et al. Expression of ICOS on Human Melanoma-Infiltrating CD4 + CD25 high Foxp3 + T Regulatory Cells: Implications and Impact on Tumor-Mediated Immune Suppression. J Immunol 2008;180:2967–80. 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.2967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Faget J, Bendriss-Vermare N, Gobert M, et al. ICOS-Ligand Expression on Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells Supports Breast Cancer Progression by Promoting the Accumulation of Immunosuppressive CD4 + T Cells. Cancer Res 2012;72:6130–41. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gu-Trantien C, Migliori E, Buisseret L, et al. CXCL13-producing Tfh cells link immune suppression and adaptive memory in human breast cancer. JCI Insight 2017;2 10.1172/jci.insight.91487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ito T, Yang M, Wang Y-H, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells prime IL-10–producing T regulatory cells by inducible costimulator ligand. J Exp Med 2007;204:105–15. 10.1084/jem.20061660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Conrad C, Gregorio J, Wang Y-H, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells promote immunosuppression in ovarian cancer via ICOS costimulation of Foxp3+ T-regulatory cells. Cancer Res 2012;72:5240–9. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nagase H, Takeoka T, Urakawa S, et al. ICOS + Foxp3 + TILs in gastric cancer are prognostic markers and effector regulatory T cells associated with H elicobacter pylori. Int J Cancer 2017;140:686–95. 10.1002/ijc.30475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pedroza-Gonzalez A, Zhou G, Vargas-Mendez E, et al. Tumor-Infiltrating plasmacytoid dendritic cells promote immunosuppression by Tr1 cells in human liver tumors. Oncoimmunology 2015;4:e1008355 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1008355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Paulos CM, Carpenito C, Plesa G, et al. The inducible costimulator (ICOS) is critical for the development of human Th17 cells. Sci Transl Med 2010;2:55ra78 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gomes-Silva D, Ramos CA. Cancer immunotherapy using CAR-T cells: from the research bench to the assembly line. Biotechnol J 2018;13:1700097 10.1002/biot.201700097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Guedan S, Posey AD, Shaw C, et al. Enhancing CAR T cell persistence through ICOS and 4-1BB costimulation. JCI Insight 2018;3 10.1172/jci.insight.96976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Amatore F, Gorvel L, Olive D. Inducible Co-Stimulator (ICOS) as a potential therapeutic target for anti-cancer therapy. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2018;22:343–51. 10.1080/14728222.2018.1444753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mo L, Chen Q, Zhang X, et al. Depletion of regulatory T cells by anti-ICOS antibody enhances anti-tumor immunity of tumor cell vaccine in prostate cancer. Vaccine 2017;35:5932–8. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.08.093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. KS L, Thibult ML, Just-Landi S, et al. Follicular B lymphomas generate regulatory T cells via the ICOS/ICOSL pathway and are susceptible to treatment by Anti-ICOS/ICOSL therapy. Cancer Res 2016;76:4648–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fu T, He Q, Sharma P. The ICOS/ICOSL pathway is required for optimal antitumor responses mediated by anti-CTLA-4 therapy. Cancer Res 2011;71:5445–54. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fan X, Quezada SA, Sepulveda MA, et al. Engagement of the ICOS pathway markedly enhances efficacy of CTLA-4 blockade in cancer immunotherapy. J Exp Med 2014;211:715–25. 10.1084/jem.20130590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liakou CI, Kamat A, Tang DN, et al. CTLA-4 blockade increases IFN -producing CD4+ICOShi cells to shift the ratio of effector to regulatory T cells in cancer patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105:14987–92. 10.1073/pnas.0806075105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Carthon BC, Wolchok JD, Yuan J, et al. Preoperative CTLA-4 blockade: tolerability and immune monitoring in the setting of a presurgical clinical trial. Clin Cancer Res 2010;16:2861–71. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vonderheide RH, LoRusso PM, Khalil M, et al. Tremelimumab in combination with exemestane in patients with advanced breast cancer and treatment-associated modulation of inducible costimulator expression on patient T cells. Clin Cancer Res 2010;16:3485–94. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kamphorst AO, Pillai RN, Yang S, et al. Proliferation of PD-1+ CD8 T cells in peripheral blood after PD-1–targeted therapy in lung cancer patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017;114:4993–8. 10.1073/pnas.1705327114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tang C, Welsh JW, de Groot P, et al. Ipilimumab with stereotactic ablative radiation therapy: phase I results and immunologic correlates from peripheral T cells. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:1388–96. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Heeren AM, Koster BD, Samuels S, et al. High and interrelated rates of PD-L1+ CD14+ antigen-presenting cells and regulatory T cells mark the microenvironment of metastatic lymph nodes from patients with cervical cancer. Cancer Immunol Res Am Assoc Cancer Res;2014:2014–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Harvey C, Elpek K, Duong E, et al. Efficacy of anti-ICOS agonist monoclonal antibodies in preclinical tumor models provides a rationale for clinical development as cancer immunotherapeutics. J Immunother Cancer 2015;3 10.1186/2051-1426-3-S2-O9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Di Giacomo AM, Calabrò L, Danielli R, et al. Long-term survival and immunological parameters in metastatic melanoma patients who responded to ipilimumab 10 mg/kg within an expanded access programme. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2013;62:1021–8. 10.1007/s00262-013-1418-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sanmamed MF, Pastor F, Rodriguez A, et al. Agonists of co-stimulation in cancer immunotherapy directed against CD137, OX40, GITR, CD27, CD28, and ICOS. Semin Oncol 2015;42:640–55. 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2015.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Burris HA, Callahan MK, Tolcher AW, et al. Phase 1 safety of ICOS agonist antibody JTX-2011 alone and with nivolumab (nivo) in advanced solid tumors; predicted vs observed pharmacokinetics (pK) in iconic. JCO 2017;35:3033 10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.3033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hansen AR, Bauer TM, Moreno V, et al. First-In-Human study with GSK3359609, an inducible T cell costimulator receptor agonist in patients with advanced, solid tumours: preliminary results from INDUCE-1. EMJ Oncol 2018;6:68–71. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yap TA, Burris HA, Kummar S, et al. Iconic: biologic and clinical activity of first in class ICOS agonist antibody JTX-2011 +/- nivolumab (nivo) in patients (PTS) with advanced cancers. JCO 2018;36:3000 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.3000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sainson RCA, Thotakura A, Parveen N, et al. KY1044, a novel anti-ICOS antibody, elicits long term in vivo anti-tumour efficacy as monotherapy and in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors. SITC, 2017. Available: https://www.kymab.com/media/uploads/files/11-Nov-2017-Kymab-KY1044-SITC-Poster.pdf

- 47. Nelson MH, Kundimi S, Bowers JS, et al. The inducible costimulator augments tc17 cell responses to self and tumor tissue. J Immunol Am Assoc Immunol 2015;194:1737–47. 10.4049/jimmunol.1401082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]