Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to conduct a systematic review of preclinical and clinical evidence to chart the successful trajectory of talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC) from the bench to the clinic.

Design

This study was a systematic review. The primary outcome of interest was the efficacy of treatment, determined by complete response. Abstract and full-text selection as well as data extraction were done by two independent reviewers. The Cochrane risk of bias tool was used to assess the risk of bias in studies.

Setting

Embase, Embase Classic and OvidMedline were searched from inception until May 2016 to assess its development trajectory to approval in 2015.

Participants

Preclinical and clinical controlled comparison studies, as well as observational studies.

Interventions

T-VEC for the treatment of any malignancy.

Results

8852 records were screened and five preclinical (n=150 animals) and seven clinical studies (n=589 patients) were included. We saw large decreases in T-VEC’s efficacy as studies moved from the laboratory to patients, and as studies became more methodologically rigorous. Preclinical studies reported complete regression rates up to 100% for injected tumours and 80% for contralateral tumours, while the highest degree of efficacy seen in the clinical setting was a 24% complete response rate, with one study experiencing a complete response rate of 0%. We were unable to reliably assess safety due to the lack of reporting, as well as the heterogeneity seen in adverse event definitions. All preclinical studies had high or unclear risk of bias, and all clinical studies were at a high risk of bias in at least one domain.

Conclusions

Our findings illustrate that even successful biotherapeutics may not demonstrate a clear translational road map. This emphasises the need to consider increasing rigour and transparency along the translational pathway.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42016043541.

Keywords: T-VEC, oncolytic virus, cancer, translation, review

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Comprehensive analysis of the translational pathway of talimogene laherparepvec.

Threats to both internal validity and construct validity were assessed.

Reporting of methods and findings was incomplete in most of the studies included, which limited our analysis

Background

Preclinical research receives approximately half of the world’s biomedical research funding, yet very few of its findings translate clinically. This represents an enormous waste of resources with an estimated US$28 billion dollars per year in the USA alone being spent on biomedical research which is not reproducible and therefore not translatable.1 One study found that only 5% of highly efficacious preclinical therapeutics were clinically translated.2 These successes often take almost 20 years to become successfully translated across the research spectrum.2 3

Although the process of clinical translation is complicated, the transition from bench-to-bedside often starts with preclinical research. These investigations (usually on animals or cells) are aimed at studying efficacy, pharmacokinetics and dynamics, as well as detailing safety.4 Next, a drug is tested in a phase I clinical trial, which usually contains a small number of participants and is aimed at studying the safety of the drug. If a drug is safe, it may proceed to phase II studies which are larger than phase I studies and are designed to test safety, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and optimal dosing regimens. They may also offer preliminary evidence of drug efficacy. Finally, a methodologically rigorous phase III study is performed. These studies are designed and powered to test efficacy in the patient population of interest (usually against a comparator such as placebo), as well as identify rarer adverse events which may have gone unnoticed in a smaller phase I or II study.5

Given the high failure rate in translating therapies across this spectrum, as well as significant time-lags associated with translation, it is important that we examine the few agents that have successfully crossed the preclinical to clinical bridge in order to learn from and replicate their success. Thus, we conducted a comprehensive evaluation of available evidence supporting the successful translation of talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC). T-VEC is a modified Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV)-1 virus produced by Amgen and it is the first, and only, Food and Drug Adminstration (FDA) approved oncolytic virus therapy; it is currently approved to treat advanced melanoma.6 Oncolytic viruses are an emerging cancer therapy that work by preferentially targeting and infecting cancer cells.6 On infection, oncolytic viruses can induce an antitumour immune response that reduces tumour burden. T-VEC was chosen as a model due to the fact that it is the only approved oncolytic virus therapy to date, despite the multitude of agents under investigation.7

Through a careful evaluation of T-VEC development, we hoped to identify factors that may contribute to bench-to-bedside success. This may serve an exemplar for other therapies as they move along the translational continuum. Thus, the purpose of this systematic review was to map the successful preclinical to clinical trajectory of T-VEC to inform the development paths of future biotherapeutics.

Methods

Our review was registered in full on PROSPERO, the international prospective register of systematic reviews (no. CRD42016043541). The review is reported in accordance to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines.8

Eligibility criteria

We included all clinical and preclinical in vivo controlled comparison studies of T-VEC for treatment of any malignancy (randomised, pseudo-randomised and non-randomised studies), as well as observational studies such as case-control, case-series and case reports. Studies reporting only ex vivo or in vitro experiments were excluded. For both preclinical and clinical studies, we included studies that administered T-VEC as a monotherapy or in combination with other therapies for treatment of malignancy. We had no exclusions on comparison treatments, which include standard line therapy or no treatment.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of interest was the efficacy of treatment. Our primary indicator of efficacy was complete response. Other measures of efficacy such as survival, response rates (durable, partial, objective), time to treatment failure and disease stability were also collected. Such measures were based on the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours Guidelines.9 In preclinical studies, additional measures of efficacy such as changes in mean tumour volume and number of lesions were collected. The primary indicator of efficacy, complete response, was used as the primary outcome regardless of reporting within the individual study, in order to assess the continuity of evidence along the research spectrum. The secondary outcome of interest was safety, for which we collected data on all adverse events in preclinical and clinical studies.

Literature search

In collaboration with a medical information specialist (Risa Shorr, Learning Services, The Ottawa Hospital) a search strategy was designed to identify all relevant preclinical and clinical studies. Searches were conducted in the following databases: Embase, Embase Classic and OvidMedline from inception until May 2016. This time frame was chosen to ensure that all published studies which contributed T-VECs FDA approval in 2015 were included. Search terms included Talimogen laherparepvec, Tvec, OncoVEX and Imlygic. Additional terms pertaining to preclinical studies (eg, animal experiment/model) and oncology (eg, cancer, neoplasm, oncolytic virus) were also included. Studies were also screened for inclusion based on reference tracking, by scanning the bibliography of included primary studies and relevant review articles. We did not impose any restrictions on language or publication type. A grey literature search was not performed. The finalised search strategy can be found in online supplementary file 1.

bmjopen-2019-029475supp001.pdf (150KB, pdf)

Study selection process

Studies identified by our literature search were collated and duplicates were removed. Titles and abstracts were independently screened for inclusion by two reviewers using DistillerSR (Evidence Partners, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada). Those deemed potentially relevant were recorded, and full-text articles were obtained. The same reviewers screened full articles for final eligibility. Disagreements at any stage were resolved by discussion or consultation with a senior team member when necessary. The study selection process was documented using a PRISMA flow diagram.

Data extraction

All data extraction was completed independently and in duplicate, using a standardised and piloted data extraction form, with disagreements resolved as mentioned above. Data pertaining to general and intervention characteristics of the included studies were extracted (eg, study design, country, type of malignancy, dosing of intervention and comparator treatments). For clinical studies, data was collected on patient characteristics (eg, age, sex, cancer staging, HSV status). For preclinical studies, characteristics on the animal model were extracted (eg, type of species, cell line used, disease induction method, age, sex, weight).

Risk of bias: assessment to risk of internal validity

Clinical studies that met inclusion criteria were assessed for risk of bias in duplicate, according to the recommended methodology of the Cochrane Collaboration.10 Five types of biases (selection, performance, detection, attrition, reporting biases) were assessed using six domains: randomisation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants/personnel, outcome assessment blinding, incomplete outcome reporting and selective outcome reporting. Additional domains assessed for risk of bias were (1) reported conflicts of interest, (2) sample size calculation and (3) funding. Each domain was given a score of ‘high’, ‘unclear’ or ‘low’ risk of bias for each study. Risk of bias assessment for preclinical studies were assessed using a modified Cochrane Risk of Bias tool and assessed the same domains as indicated for clinical studies.11

Assessment of threats to construct validity

Construct validity is the concept in how well a preclinical experiment (ie, animal studies) corresponds to the clinical entity it is intended to model. There are various threats to construct validity that can be introduced from the preclinical study design. The items evaluated in duplicate for each preclinical study include (1) use of adult animals, (2) use of animals with advanced stage disease (defined as the presence of multiple visceral lesions and/or clinical/histological signs of malignant progression), (3) immune status of animals to HSV, (4) whether a xenograft model was used and (5) the use of a humanised immune system model. Each of these items was given a score of ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘unclear’ for every preclinical study.

Statistical analysis

Efficacy was expressed as proportions with accompanying 95% CIs. If CIs were not present within the individual study, they were calculated via standard methods.12 To assess the continuity between preclinical and clinical studies, the efficacy of studies was plotted as percentage response.

Deviations from protocol

We were unable to assess safety as we could not acquire patient-level safety data. Furthermore, our primary efficacy outcome stated in the protocol was durable response rate. However, this was changed to complete response as most clinical studies did not report durable response, and we needed to track T-VEC’s trajectory over several studies. We acknowledge the limitation of this approach, given the FDA approved T-VEC based on the OPTIM trial,13 the primary endpoint of which was durable response rate. Subgroup analyses, meta-analyses, Egger’s test and pooling of data could not be conducted due to the limited available data.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in this research.

Results

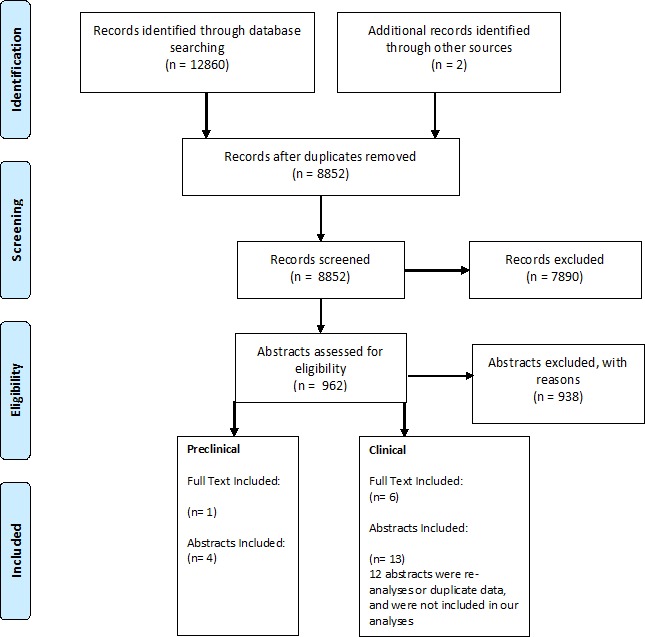

On removal of duplicates, a total of 8852 references were identified by the electronic search. During the review of titles and abstracts, 7890 references were excluded. Following full-text screening, another 938 articles were excluded for reasons such as wrong study design (ie, review article) or wrong study intervention (ie, a different cancer therapeutic). A total of seven clinical studies13–19 and five preclinical studies20–24 were included in our review (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study selection flow diagram.

Characteristics of included trials

Characteristics of included preclinical studies are shown in table 1. Preclinical studies were published between 2003 and 2016 and sample sizes ranged from 20 to 90. Of the five preclinical studies, three used a lymphoma model, one used a colorectal model and one used a melanoma model. All studies were performed in mice. The duration of follow-up was reported by two studies and ranged from 10 to 35 days. The dose of T-VEC used ranged from 3×104 plaque forming units (PFU) to 5×106 PFU. Frequency of T-VEC administration varied: every 3 days for 1 week, every 3 days for 9 days, a single dose given only once and every other day for 5 days. Specific details of study and intervention characteristics for each preclinical study can be found in online supplementary files 2 and 3.

Table 1.

Study characteristics of included preclinical studies of T-VEC

| Preclinical study | Treatment | Total number of animals used | Type of cancer/model | Efficacy measures* | Risk of bias (/9†) |

| Liu et al 20 | T-VEC; HSV1 wild type immunisation | 90 | Lymphoma (A20 murine lymphoma mouse model) | CR: 100% (n=10) (injected) | 9 |

| Piasecki et al 21 | T-VEC | NR | Lymphoma (A20 murine lymphoma mouse model) | CR: 70%–100% of injected, 50%–60% of contralateral | 9 |

| Piasecki et al 23 | T-VEC +Anti-PD-1 | NR | Colorectal (MC-38 colon carcinoma mouse model) | CR: 80.0% (44.2%–96.5%) (injected) n=10 CR: 20.0% (3.5%–55.8%) (contralateral) n=10 |

9 |

| Cooke et al 22 | T-VEC | 40 | Lymphoma (A20 murine lymphoma mouse model) | CR: 100% (65.5%–100%) (injected) n=10 CR: 50% (23.7%–76.3%) (contralateral) |

9 |

| Cooke et al 24 | T-VEC | 20 | Melanoma (B16F10 melanoma model) | NR: statistically significant tumour reduction and survival noted | 9 |

* DR – durable response; OR – objective response; CR – complete response/complete regression; PR – partial response;DR/OR/CR/PR definitions were based on RECIST guidelines for clinical studies. † Total number of domains that were assessed a score of high risk or unclear (maximum = 9).

CR, complete response; HSV, Herpes Simplex Virus; NR, Not reported; PR, partial response; T-VEC, talimogene laherparepvec.

Characteristics of included clinical studies are shown in table 2. Studies were published between 2006 and 2016 and took place in seven countries. Sample sizes ranged from 17 to 295. Of the seven clinical studies, four were in melanoma patients, one was in pancreatic cancer patients, one in head and neck cancer patients and one studied a mix of breast, colorectal, melanoma and head and neck cancer patients. Six were either phase I or II, and one trial was a phase III evaluation. The primary outcome was efficacy in two studies, safety in three studies and a combination of efficacy and safety in the other two studies. The duration of follow-up ranged from 6 weeks to 44 months.

Table 2.

Study characteristics of included clinical studies of T-VEC

| Clinical study | Treatment | Total N | Type of cancer | Efficacy measures* | Risk of bias (/9†) |

| Hu et al

14

Non-controlled phase I |

T-VEC | 30 (9 melanoma) | Breast, colorectal, melanoma, head and neck | CR: 0% (0%–14.1%) PR: 0% (0%–14.1%) |

7 |

| Senzer et al

15

Non-controlled phase II |

T-VEC | 50 | Melanoma | OR: 26.0% (15.1%–40.6%) CR: 20.0% (10.5%–34.1%) PR: 10.0% (3.7%–22.6%) |

7 |

| Harrington et al

18

phase I/II |

T-VEC +cisplatin | 17 | Head and neck | CR: 23.5% (7.8%–50.2%) PR: 58.8% (33.5%–80.6%) OR: 82.4% (55.8%–95.3%) |

6 |

| Chang et al

19

phase I |

T-VEC | 17 | Pancreatic | OR: 0% (0%–22.9%) | 6 |

| Andtbacka et al

13

phase III |

T-VEC | 295 | Melanoma | DR: 16.3% (12.1%–20.5%) OR: 26.4% (21.4%–31.5%) PR: 15.6% (11.7%–20.3%) CR: 10.8% (7.6%–15.1%) |

3 |

| GM-CSF (control) | 141 | DR: 2.1% (0%–4.5%) OR: 5.7% (1.9%–9.5%) PR: 5.0% (1.3%–8.5%) CR:<1% |

|||

| Long et al

16

phase Ib |

T-VEC +pembrolizumab | 21 | Melanoma | – | 6 |

| Puzanov et al

17

phase Ib |

T-VEC+IPI | 18 | Melanoma | DR: 44.4% (22.4%–68.7%) OR: 50.0% (29.0%–70.9%) CR: 22.2% (7.4%–48.1%) PR: 27.8% (10.7%–53.6%) |

6 |

*Definitions of DR/OR/CR/PR were based on RECIST guidelines for clinical studies.

†Total number of domains that were assessed a score of high risk or unclear (maximum=9). The nine domains include randomisation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants/personnel, outcome assessment blinding, incomplete outcome reporting, selective outcome reporting, reported conflicts of interest, sample size calculation and funding.

CR, complete response/complete regression; DR, durable response; IPI, Ipilimumab; OR, objective response; PR, partial response; RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours; T-VEC, talimogene laherparepvec.

T-VEC was administered alone in four studies, while it was administered immediately following to systemic therapy in three studies. The dose of T-VEC administered ranged from 104 to 108 PFU/mL. In the large study, phase III, T-VEC was administered at ≤4 mL × 106 PFU/mL once, and then 3 weeks later, ≤4 mL 108 PFU/mL was administered every 2 weeks for a median of 23 weeks. A similar dosing regimen was used in three other trials. The other three trials were dose-finding in nature and had multiple trial arms receiving increasing doses of T-VEC. In-depth study details, as well as participant and intervention details for each study, can be found in online supplementary files 4-6.

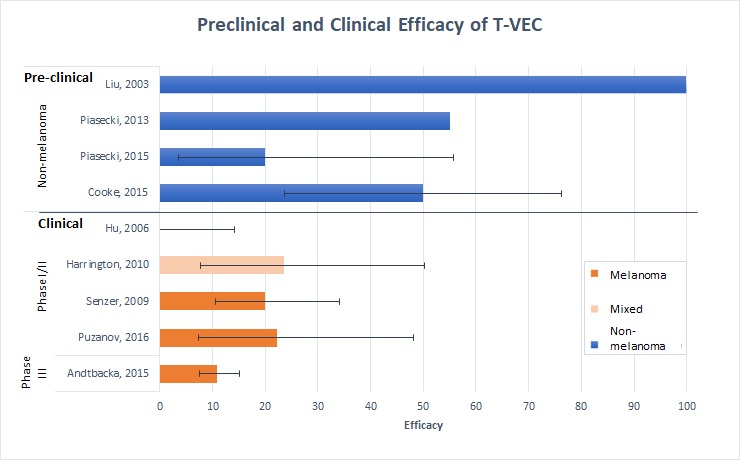

Efficacy of treatment

Treatment efficacy for each study is summarised in table 1, table 2 and figure 2. Preclinical studies reported complete regression rates up to 100% for injected tumours and 80% for contralateral tumours (see also online supplementary file 7). In comparison, the first published phase I T-VEC clinical trial reported a complete response of 0% for cutaneous lesions caused by malignancies of head and neck, breast, colorectal and melanoma. Of the multiple malignancies treated, melanoma had the best response in this trial. Subsequent phase I/II melanoma trials were then conducted and demonstrated complete response rates of 20%–22%. This was followed by the phase III OPTIM melanoma trial, which had a complete response rate of 10.8%. Studies involving non-melanoma cancers varied with efficacies between 0% and 24%.

Figure 2.

Preclinical and clinical efficacy of T-VEC. Four preclinical studies using mice demonstrated efficacy rates of 20%–100% and clinical studies (three melanoma and two mixed malignancy studies) demonstrated efficacy rates from 0% to 23.5%. Non-melanoma/mixed studies are represented by blue bars, whereas melanoma studies are represented by orange bars. Where possible, complete regression rates of contralateral tumours for mice were used in preclinical studies and complete response was used for clinical studies. Efficacy rates decrease in the preclinical to clinical translation and on more rigorous study design in later phase clinical trials. Error bars are plotted and represent 95% CIs. Some studies were not included in this analysis as they did not report the outcome of CR. CR, complete response; T-VEC, talimogene laherparepvec.

Safety of treatment

We attempted to assess safety across clinical studies; however, we were unable to obtain patient-level data from any of the studies. The definitions of adverse events, and the manner in which they were classified, were found to be highly heterogenous across studies. Studies did not specify what percent of adverse events were repeated adverse events from the same patient(s), used different criteria for recording and reporting adverse events, and categorised them differently. Therefore, we were unable to pool adverse events or interpret findings reliably.

Validity assessments

Construct validity, the concept of how well an animal model represents the clinical entity it is intended to mimic, was first assessed through the following domains: the use of appropriately aged mice, advanced stage of disease, HSV-immunity and types of mouse models. None of the preclinical studies fully reported or used methodologies to reduce threats to construct validity domains (table 3). No studies declared using adult animal models, no studies used animals with late stage disease, only one study used animals immune to HSV, no studies used a xenograft model and no studies reported using an animal model with a humanised immune system.

Table 3.

Construct validity assessment for preclinical studies

| First author, year | Adult used | Animals with advanced stage disease | Animals immune to HSV | Xenograft model used | Used model with a Humanised immune system |

| Cooke, 201624 | Unclear | No | Unclear | No | Unclear |

| Cooke, 201522 | Unclear | No | Unclear | No | Unclear |

| Piasecki, 201523 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | No | Unclear |

| Piasecki, 201321 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | No | Unclear |

| Liu, 200320 | Unclear | No | Yes | No | Unclear |

HSV, Herpes Simplex Virus.

We also assessed internal validity (ie, risk of bias) and found that all preclinical studies had high or unclear risk of bias across the assessed domains: randomisation sequence, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete reporting, sample size calculation and funding source (table 4). For clinical studies, early phase trials had high or unclear risk of bias across at least six of nine domains, whereas the more robust phase III OPTIM trial had the lowest risk of bias and also the lowest efficacy of any of the published melanoma clinical trials (table 5). Reporting of key methodological elements was lacking.

Table 4.

Risk of bias assessment for preclinical studies

| Author, Year | Random Sequence Generation | Allocation Concealment | Blinding of Personnel | Blinded Outcome Assessment | Incomplete Outcomes Addressed | Selective Outcome Reporting | Conflicts of Interest | A Priori Sample Size Calculation | Funding |

| Cooke, 201624 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High Risk |

| Cooke, 201522 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High Risk |

| Piasecki, 201523 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High Risk |

| Piasecki, 201321 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High Risk |

| Liu, 200320 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High Risk |

Table 5.

Risk of bias assessment for clinical studies

| Author, Year | Random Sequence Generation | Allocation Concealment | Blinding of Participants and Personnel | Blinding of Outcome Assessors | Incomplete Outcome Data Addressed | Selective Reporting | Conflicts of Interest | Funding | Sample Size Calculation |

| Andtbacka, 201513 | Low Risk | Low Risk | High Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | High Risk | High Risk | Low Risk |

| Long, 201516 | High Risk | High Risk | High Risk | Unclear | Low Risk | Low Risk | High Risk | High Risk | Unclear |

| Puzanov, 201617 | High Risk | High Risk | High Risk | Unclear | Low Risk | Low Risk | High Risk | High Risk | Unclear |

| Chang, 201219 | High Risk | High Risk | High Risk | Unclear | Low Risk | Low Risk | High Risk | High Risk | Unclear |

| Harrington, 201018 | High Risk | High Risk | High Risk | Unclear | Low Risk | Low Risk | High Risk | High Risk | Unclear |

| Senzer, 200915 | High Risk | High Risk | High Risk | Unclear | Low Risk | High Risk | High Risk | High Risk | Unclear |

| Hu, 200614 | High Risk | High Risk | High Risk | Unclear | Low Risk | Unclear | High Risk | High Risk | Unclear |

Discussion

We hoped to synthesise the evidence to produce a clear road map of T-VEC’s translation in the published literature. This would allow us to follow the journey of a successful biotherapeutic, and potentially use this as a blueprint for similar efforts in the future. Yet, we were unable to paint a clear picture of how the evidence was used in proceeding to melanoma clinical trials. Rather, our assessment uncovered a disconnect between in vivo preclinical and clinical findings. Furthermore, the road map was plagued with poor reporting, high risk of bias and insufficient data along the translational path. Overall, we were surprised by the pace and magnitude of diminishing efficacy as T-VEC moved from bench-to-bedside and then towards later phase clinical trials (ie, phase I to III). Although T-VEC was successful in terms of gaining regulatory approval, its translational path is complicated and the pieces of the evidence puzzle do not easily fit together. While we appreciate that translation is not a predictable linear process, it is difficult to learn from the example of T-VEC given the available and reported preclinical and clinical evidence.

While many novel therapeutics are under intellectual property rights, details of study design and results should be transparently reported for scientists, clinicians and patients to evaluate findings. The fact that the only FDA approved oncolytic virus therapy is not clearly reported illustrates the issues plaguing the success of cancer therapeutics. Nonetheless, T-VEC has shown some efficacy in treating refractory melanoma25 and numerous clinical trials are underway to assess its use in combination with other cancer regimens and in treating other malignancies. It is also the recommended treatment by the National Comprehensive Cancer Centre for patients with in-transit melanoma.26

Perhaps the largest discrepancy noted was that only a single preclinical study used a melanoma model, whereas all but two clinical studies administered T-VEC to melanoma patients. Conversely, lymphoma, which was used in three preclinical studies, was not assessed in clinical studies. Interestingly, our subsequent searches found that Amgen’s FDA filing (STN# 125518.000)27 for T-VEC did not appear to report on any in vivo melanoma models, whereas the European Medicines Agency (EMA) report did (EMA/734400/2015).28 Thus, the majority of animal models were off-target from the malignancies studied in clinical trials and may have poorly represented melanoma in the clinical setting. Coupled with these findings was the fact that the majority of included studies were found to be at a high or unclear risk of bias for most domains. Such threats to internal validity can bias results and may help explain T-VEC’s superior preclinical efficacy compared with later phase clinical trials. A lack of randomisation and blinding in preclinical studies has been associated with inflated effect sizes,29 30 thus this may partially explain the preclinical to clinical discrepancy of T-VEC.

Reporting of methods and findings was incomplete in most of the studies included. Only one full preclinical article on T-VEC was published, and solely aggregate patient data for later phase trials was available. Poor reporting and study design are major contributors to the ongoing reproducibility crisis in preclinical research.31 Thus, in hopes of presenting a clearer picture of T-VEC’s successful translation, we contacted Amgen to obtain preclinical in vivo melanoma data, patient-level safety data and any additional efficacy data. Patient-level data would afford the ability to combine data across T-VEC’s clinical development and also provide clarification into the categorisation of adverse events. Recently, release of individual patient data to third parties has been advocated by the Institute of Medicine, journal editors and others as it enhances transparency, enables reanalyses of data and helps address reproducibility.32 The reporting of harms in clinical trials remains an issue in the scientific community,33–35 and represents a roadblock to translational success. Some basic steps required to improve the reporting of safety in translational research include the development of standardised scales and instruments, instituting active rather than passive surveillance for toxicity, including detailed information on participant withdrawals due to toxicity, reporting the timing, frequency and duration of clinically relevant events and the publication of raw data.36 37 Amgen, however, was unwilling to enter a data sharing agreement, as they stated that there was little value to compel a transparent data release for our proposed analyses. This lack of transparency and incomplete reporting is disappointing, especially considering that it was Amgen that previously highlighted poor reporting as contributing to its own failure to reproduce 47 of 53 high-impact preclinical cancer studies.38 Their findings fuelled a call by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and other stakeholders to enhance the reproducibility and transparency of preclinical research.39

As stated, we recognise that translation is not a linear process, but we should observe consistent and coherent patterns. Moving forward, we suggest that preclinical and clinical studies for emerging therapies should be fully reported and attention should be given to validities in order to develop more precise estimates of effect early in development. Investigators should carefully match their preclinical model to the intended clinical population; when possible, both disease states and outcomes measured should have high construct validity. Following successful exploratory preclinical studies, investigators should consider preclinical systematic reviews40 and designing methodologically rigorous confirmatory and/or multicentre preclinical studies.41 These steps may allow preclinical testing to more accurately forecast downstream clinical results in human patients.30 Within the trajectory of clinical development (ie, once clinical trials have been initiated), careful consideration of methods to reduce bias should also be considered (although, this may not be possible for the earliest phase trials). We believe these steps will provide unbiased and valuable information that will ultimately provide patients with cancer therapies that match their preclinical and early clinical promise.

Conclusions

The findings from our systematic review demonstrate that even successful biotherapeutics may not demonstrate a clear translational road map. The magnitude of efficacy of T-VEC demonstrated in preclinical studies was considerably larger than subsequent clinical trials; the most methodologically rigorous trial included in our review demonstrated the smallest degree of efficacy. Methodologically rigorous studies should be performed earlier on in the translational pathway, which may help provide a realistic estimate of treatment efficacy prior to clinical translation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Risa Shorr (Ottawa Hospital Research Institute librarian) for systematic search assistance. ML is supported by The Ottawa Hospital Anesthesia Alternate Funds Association and the Scholarship Protected Time Program, Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Ottawa.

Footnotes

Twitter: @manojlalu

ML and GJL contributed equally.

Contributors: ML and DAF conceptualised the study. ML, RCA, DAF and GJL contributed to the study design. GJL, YYD, JM and CB conducted data extraction. All authors analysed and interpreted the data. ML and GJL were responsible for drafting the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and provided intellectual content. All authors approve the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: Biotherapeutics for Cancer Treatment (BioCanRx) supported the conduct of this study by a Catalyst grant. BioCanRx is a Government of Canada funded Networks of Centres of Excellence and was not involved in any other aspect of the project, such as the design of the project’s protocol and analysis plan, the collection of data and analyses. CB was also supported by a BioCanRx studentship. ML is supported by The Ottawa Hospital Anesthesia Alternate Funds Association and the Scholarship Protected Time Program, Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, uOttawa.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1. Freedman LP, Cockburn IM, Simcoe TS. The economics of reproducibility in preclinical research. PLoS Biol 2015;13:e1002165 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG, Ntzani EE, Ioannidis JPA. Translation of highly promising basic science research into clinical applications. Am J Med 2003;114:477–84. 10.1016/S0002-9343(03)00013-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Morris ZS, Wooding S, Grant J. The answer is 17 years, what is the question: understanding time lags in translational research. J R Soc Med 2011;104:510–20. 10.1258/jrsm.2011.110180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Use of laboratory animals in biomedical and behavioral research. Washington (DC), 1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Umscheid CA, Margolis DJ, Grossman CE. Key concepts of clinical trials: a narrative review. Postgrad Med 2011;123:194–204. 10.3810/pgm.2011.09.2475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rehman H, Silk AW, Kane MP, et al. . Into the clinic: Talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC), a first-in-class intratumoral oncolytic viral therapy. J Immunother Cancer 2016;4 10.1186/s40425-016-0158-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fergusson DA, Wesch NL, Leung GJ, et al. . Assessing the completeness of reporting in preclinical oncolytic virus therapy studies. Molecular Therapy - Oncolytics 2019;14:179–87. 10.1016/j.omto.2019.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:1006–12. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. . New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009;45:228–47. 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, et al. . The Cochrane collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928 10.1136/bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hooijmans CR, Rovers MM, de Vries RBM, et al. . SYRCLE's risk of bias tool for animal studies. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014;14:43 10.1186/1471-2288-14-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Newcombe RG. Two-Sided confidence intervals for the single proportion: comparison of seven methods. Stat Med 1998;17:857–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Andtbacka RHI, Kaufman HL, Collichio F, et al. . Talimogene Laherparepvec improves durable response rate in patients with advanced melanoma. JCO 2015;33:2780–8. 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.3377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hu JCC, Coffin RS, Davis CJ, et al. . A phase I study of OncoVEXGM-CSF, a second-generation oncolytic herpes simplex virus expressing granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Clin Cancer Res 2006;12:6737–47. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Senzer NN, Kaufman HL, Amatruda T, et al. . Phase II clinical trial of a granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating Factor–Encoding, second-generation oncolytic herpesvirus in patients with unresectable metastatic melanoma. JCO 2009;27:5763–71. 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.3675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Long GV, Dummer R, Ribas A, et al. . 24LBA safety data from the phase 1B part of the MASTERKEY-265 study combining talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC) and pembrolizumab for unresectable stage IIIB-IV melanoma. Eur J Cancer 2015;51:S722 10.1016/S0959-8049(16)31944-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Puzanov I, Milhem MM, Minor D, et al. . Talimogene Laherparepvec in combination with ipilimumab in previously untreated, unresectable stage IIIB-IV melanoma. JCO 2016;34:2619–26. 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.1529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Harrington KJ, Hingorani M, Tanay MA, et al. . Phase I/II study of oncolytic HSVGM-CSF in combination with radiotherapy and cisplatin in untreated stage III/IV squamous cell cancer of the head and neck. Clinical Cancer Research 2010;16:4005–15. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chang KJ, Senzer NN, Binmoeller K, et al. . Phase I dose-escalation study of talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC) for advanced pancreatic cancer (Ca). Journal of Clinical Oncology 2012;30. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu BL, Robinson M, Han Z-Q, et al. . Icp34.5 deleted herpes simplex virus with enhanced oncolytic, immune stimulating, and anti-tumour properties. Gene Ther 2003;10:292–303. 10.1038/sj.gt.3301885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Piasecki J, Tiep L, Zhou J, et al. . Talilmogene Iaherparepvec generates systemic T-cell-mediated anti-tumor immunity. J Immunother Cancer 2013;1 10.1186/2051-1426-1-S1-P198 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cooke K, Rottman J, Zhan J, et al. . Oncovex MGM-CSF –mediated regression of contralateral (non-injected) tumors in the A20 murine lymphoma model does not involve direct viral oncolysis. J Immunother Cancer 2015;3 10.1186/2051-1426-3-S2-P336 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Piasecki J, le T, Ponce R, et al. . Abstract 258: Talilmogene laherparepvec increases the anti-tumor efficacy of the anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint blockade. Cancer Research 2015;75:258. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cooke K, Estrada J, Zhan J, et al. . Abstract 2351: development of a B16F10 cell line expressing mNectin1 to study the activity of OncoVEXmGM-CSF in murine syngeneic melanoma models. Cancer Research 2016;76:2351. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Louie RJ, Perez MC, Jajja MR, et al. . Real-World outcomes of Talimogene Laherparepvec therapy: a multi-institutional experience. J Am Coll Surg 2019;228:644–9. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.12.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. National Comprehensive Cancer Center Guidelines for patients: melanoma 2018.

- 27. US Food and Drug Administration IMLYGIC (talimogene laherparepvec), 2015. Available: https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/cellular-gene-therapy-products/imlygic-talimogene-laherparepvec

- 28. European Medicines Agency Assessment report Imlygic international non-proprietary name: talimogene laherparepvec, 2015. Available: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/imlygic-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf

- 29. Hirst JA, Howick J, Aronson JK, et al. . The need for randomization in animal trials: an overview of systematic reviews. PLoS One 2014;9:e98856 10.1371/journal.pone.0098856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Macleod MR, van der Worp HB, Sena ES, et al. . Evidence for the efficacy of NXY-059 in experimental focal cerebral ischaemia is confounded by study quality. Stroke 2008;39:2824–9. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.515957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Landis SC, Amara SG, Asadullah K, et al. . A call for transparent reporting to optimize the predictive value of preclinical research. Nature 2012;490:187–91. 10.1038/nature11556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zarin DA, Tse T. Sharing individual participant data (IPD) within the context of the trial reporting system (TRS). PLoS Med 2016;13:e1001946 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hodkinson A, Kirkham JJ, Tudur-Smith C, et al. . Reporting of harms data in RCTs: a systematic review of empirical assessments against the CONSORT harms extension. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003436 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rodgers MA, Brown JVE, Heirs MK, et al. . Reporting of industry funded study outcome data: comparison of confidential and published data on the safety and effectiveness of rhBMP-2 for spinal fusion. BMJ 2013;346:f3981 10.1136/bmj.f3981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jureidini JN, McHenry LB, Mansfield PR. Clinical trials and drug promotion: selective reporting of study 329. International Journal of Risk & Safety in Medicine 2008;20:73–81. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ioannidis JPA, Lau J. Improving safety reporting from randomised trials. Drug Safety 2002;25:77–84. 10.2165/00002018-200225020-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lineberry N, Berlin JA, Mansi B, et al. . Recommendations to improve adverse event reporting in clinical trial publications: a joint pharmaceutical industry/journal editor perspective. BMJ 2016;355 10.1136/bmj.i5078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Begley CG, Ellis LM. Drug development: raise standards for preclinical cancer research. Nature 2012;483:531–3. 10.1038/483531a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Collins FS, Tabak LA. Policy: NIH plans to enhance reproducibility. Nature 2014;505:612–3. 10.1038/505612a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lalu MM, Sullivan KJ, Mei SHJ, et al. . Evaluating mesenchymal stem cell therapy for sepsis with preclinical meta-analyses prior to initiating a first-in-human trial. eLife 2016;5 10.7554/eLife.17850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Llovera G, Hofmann K, Roth S, et al. . Results of a preclinical randomized controlled multicenter trial (pRCT): Anti-CD49d treatment for acute brain ischemia. Sci Transl Med 2015;7:ra121 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa9853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-029475supp001.pdf (150KB, pdf)