Abstract

Background

In the UK, drivers aged 17 to 21 years make up 7% of licence holders but 13% of drivers involved in road traffic crashes resulting in injury. As in many countries, the UK government has proposed to tackle this problem with driver education programmes in schools and colleges. However, there is a concern that if driver education leads to earlier licensing this could increase the number of teenagers involved in road traffic crashes.

Objectives

To quantify the effect of school‐based driver education on licensing and road traffic crashes.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, CIG's specialised register, MEDLINE, National Research Register, and the Science & Social Science Citation Index. We also checked reference lists of identified papers and contacted authors and experts in the field.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials comparing school‐based driver education to no driver education and assessing the effect on licensing and road traffic crash involvement.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently screened search results, extracted data and assessed trial quality.

Main results

Three trials, conducted between 1982 and 1984, met the inclusion criteria (n=17,965). Two trials examined the effect of driver education on licensing. In the trial by Stock (USA) 87% of students in the driver education group obtained their driving licence as compared to 84.3% in the control group (RR 1.04; 95% CI 1.02 to 1.05). In the trial by Wynne‐Jones (New Zealand) the time from trial enrolment to licensing was 111 days in males receiving driver education compared with 300 days in males who did not receive driver education, and 105 days in females receiving driver education compared with 415 days in females who did not receive driver education.

All three trials examined the effect of driver education on road traffic crashes. In the trial by Strang (Australia), 42% of students in each group had one or more crashes since being licensed (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.23). In the trial by Stock, the number of students involved in one or more crashes as a driver was 27.5% in the driver education group compared to 26.7% in the control group (RR 1.03; 95% CI 0.98 to 1.09). In the trial by Wynne‐Jones, the number of students who experienced crashes was 16% in the driver education group as compared to 14.5% in the control group (RR 1.10; 95% CI 0.76 to 1.59).

Authors' conclusions

The results show that driver education leads to early licensing. They provide no evidence that driver education reduces road crash involvement, and suggest that it may lead to a modest but potentially important increase in the proportion of teenagers involved in traffic crashes.

Plain language summary

School based driver education leads to early licensing and may increase road crash rates.

Teenagers have a higher risk of road death and serious injury than any other group. School based driver education has been promoted as a strategy to reduce the number of road crashes involving teenagers. The results of this systematic review show that driver education in schools leads to early licensing. They provide no evidence that driver education reduces road crash involvement, and suggest that it may lead to a modest but potentially important increase in the proportion of teenagers involved in traffic crashes.

Background

In March 2000, the British Government launched its road safety strategy, setting out how it plans to achieve a 40% reduction in road deaths and serious injuries by 2010 (DETR 2000). Prominent within the strategy is a plan to reduce deaths and serious injuries in teenage drivers. Drivers aged 17 to 21 years make up 7% of licence holders but 13% of drivers involved in road traffic crashes resulting in injury (DETR 2000). The British government proposed to tackle the problem of teenage road deaths with driver education programmes in schools and colleges. Students aged 16 to 18 years were offered an education package developed by the Driving Standards Agency (DSA), the executive agency of the Department of Environment, Transport and the Regions (DETR) responsible for driving tests in Britain and funded from driving test fees (www.driving‐test.co.uk). The DSA Schools Programme involves presentations by driving examiners about selecting a driving instructor, the theory and practical tests, and a range of road safety issues. In the year the policy was announced, driving examiners made 800 presentations to schools and colleges in Britain reaching 125,000 students. In December 2000, Mr Keith Hill, Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for the DETR, announced an expansion of the programme to reach some 750,000 students (House of Commons).

Driver education has a long history as a road safety strategy and considerable effort has been given to evaluating its effectiveness (Vernick 1999). A major concern with driver education is that it might encourage teenagers to obtain a driving licence and start driving sooner than they would in the absence of driver education. Because teenagers have a higher risk of road death and serious injury than any other age group, earlier licensing could offset any beneficial effect of driver education and increase the number of teenage road traffic crashes. To quantify the effect of school driver education on licensing and road traffic crashes we conducted a systematic search for randomised controlled trials.

Objectives

To quantify the effect of school‐based driver education versus no driver education on licensing and road traffic crashes.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials.

Types of participants

Young people aged 15 to 24 years who had not yet obtained a drivers licence.

Types of interventions

School‐based driver education versus no driver education.

Types of outcome measures

-

Driver licensing as measured by;

the proportion of students who have obtained a driving licence at the end of the trial period or

time from randomisation to licensing

Road traffic crashes

Road related injuries (fatal and non‐fatal)

We did not include driving skills as an outcome measure in this review because we could not be certain that there was a direct relationship between improvements in driving skills and reduced risk of road traffic crashes. The use of a surrogate end point (improved driving skills) for an adverse outcome (road crash) would assume a direct relationship between the two, an assumption that may be inappropriate.

Search methods for identification of studies

The searches were last updated in May 2006.

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases;

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (The Cochrane Library issue 2, 2006)

the Cochrane Injuries Group's specialised register (to May 2006)

MEDLINE (1966 to May week 3, 2006)

National Research Register (issue 2, 2006)

Science & Social Science Citation Index (to May 2006)

TRANSPORT (includes TRIS, IRRD and TRANSDOC) (to 2006/06)

The search strategies for each database are presented in Appendix 1.

Note: Search strategies for controlled studies in medical databases can achieve high sensitivity and PPV because terms describing the study methodology are included among the indexing (descriptor) terms. Road safety databases, however, have a very limited range of indexing terms describing the study methodology. Previous work by the Cochrane Injuries Group used word frequency analysis to develop an electronic search strategy of known sensitivity and positive predictive value (PPV) to identify reports of controlled evaluation studies of road safety interventions in the TRANSPORT database. However, it was found that there are no search terms that combine acceptable sensitivity and positive predictive value. For this reason, we did not include methodological search terms in the search strategy on the TRANSPORT database. Because we could not use methodological indexing terms in the search strategy it was necessary to use terms that restricted the search output to a manageable number of studies. We therefore used terms describing the outcomes of interest. However, the possibility that we would have overlooked studies that did not mention these terms in the abstract or key words is open to question.

Searching other resources

We also checked reference lists of identified papers and contacted authors and experts in the field.

Data collection and analysis

Electronic search results were independently screened for reports of possibly relevant randomised controlled trials and these were retrieved in full. Two authors (IR, IK) applied the selection criteria independently to the trial reports. We searched the reference lists of included trials and contacted authors to ask about unpublished studies. Two authors (IR, IK) independently extracted information on the method of randomisation and allocation concealment, the number of participants in each group, the nature of the intervention and the outcomes in each group. Authors were not blinded to the authors or journal when extracting data. Where there was insufficient information in the published report we contacted the authors for clarification.

The results of each individual trial and the pooled estimate if appropriate were expressed as relative risks (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results

Description of studies

Strang 1982 This trial involved 779 male learner drivers aged 17 to 19 years, who were randomly assigned to receive one of three driver education courses or to a control group that received no formal training. The outcome measures assessed were self and police‐reported traffic accidents and violation up to three years since being licensed.

Stock 1983 This trial involved 16,338 high school students randomly assigned to one of two driver education programmes or to a control group that received no formal driver education. The outcome measures assessed were number of students licensed on completion of the course or within six months of their sixteenth birthday, and official reports of traffic crashes and violation up to 2 to 4 years since trial enrolment.

Wynne‐Jones 1984 This trial involved 848 secondary school students aged 15 to 18 years, who were randomly assigned to attend the Automobile Association driver training programme or to a control group that were left to their own devices to learn to drive. The outcome measures assessed were licensing delay and self and police‐reported traffic crashes up to 18 months since trial enrolment.

Further details of each trial are presented in the Table of Included Studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

Strang 1982 Participants were randomised using stratified randomisation techniques based on types of schools. The method of allocation concealment was not described.

Stock 1983 Participants were randomised using a stratified random sampling plan, based on parents' socio‐economic status, student grade point average and sex. Allocation was by central computer and was well concealed.

Wynne‐Jones 1984 Participants were randomised by ballot within each school, stratified by sex, either to attend the driving course or to be left to their own devices to learn to drive. Method of balloting was not described and allocation concealment was unclear. Data were analysed as randomised, on an intention‐to‐treat basis.

Effects of interventions

After a full text review, three studies were judged to meet the inclusion criteria.

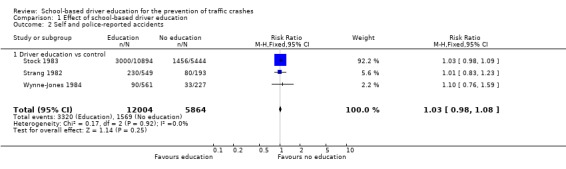

Strang 1982 In this trial on a total of 779 male learner drivers the proportion of participants who had at least one crash since being licensed was 230/549 (42%) for students who received school‐based driver education as compared to 80/193 (42%) in the control group (RR 1.01; 95% CI 0.83 to 1.23). There were no data on licensing.

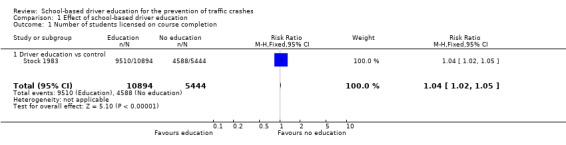

Stock 1983 In this trial on a total of 16,338 high school students, 9510/10894 (87%) of students in the driver education group had been licensed since course completion compared to 4588/5444 (84.3%) in the control group (RR 1.04; 95% CI 1.02 to 1.05). The number of students who were involved in one or more crashes as a driver was 3000/10894 (27.5%) in the driver education group as compared to 1456/5444 (26.7%) in the control group (RR 1.03;95% CI 0.98 to 1.09).

Wynne‐Jones 1984 In this trial on a total of 848 secondary school students, the number of days from trial enrolment until a driving licence was obtained (licensing delay) was significantly shorter in the driver education group. Data on licensing delay were stratified by sex and insufficient information was available in the published report to combine the strata or to calculate the mean difference in licensing delay and its 95% confidence interval. The number of days from trial enrolment to licensing was 111 days in males receiving driver education compared with 300 days in males who did not receive driver education (t=7.19, P<0.001). In females the number of days from trial enrolment to licensing was 105 days in females receiving driver education compared with 415 days in females who did not receive driver education (t=9.88, P<0.001). The number of students who were involved in crashes was 90/561(16%) in students who received driver education as compared to 33/227 (14.5%) in the control group (RR 1.10; 95% CI 0.76 to 1.59) .

Discussion

There is no evidence that driver education reduces teenage involvement in road traffic crashes. Because driver education encourages earlier licensing it may lead to a modest but potentially important increase in the number of teenagers involved in road traffic crashes. The three identified trials of driver education were conducted in Australia, USA and New Zealand, between 1982 and 1984, and it is important to ask whether their results can be generalised to contemporary driver education programmes such as the DSA Schools Programme as proposed by the British government. The DSA programme is much less intensive, the entire presentation lasting only 50 minutes, with no behind the wheel driver training and greater emphasis on taking the driving test. For driver education to be effective in reducing crash involvement, any effect of early licensing must be offset by improved driving skills, if indeed teaching driving skills reduces road crash rates at all (Gregersen 1996). With its emphasis on the driving test, the DSA programme could easily increase licensing but with little or no impact on driving skills, potentially the worst combination from a road safety perspective. If the DSA programme increased the proportion of licensed teenagers by just 2%, then an additional 27 teenagers might be killed or seriously injured each year as a result of this road safety programme.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The results show that driver education in schools leads to early licensing. They provide no evidence that driver education reduces road crash involvement, and suggest that it may lead to a modest but potentially important increase in the proportion of teenagers involved in traffic crashes.

Implications for research.

In view of their potential to encourage earlier licensing and thus increase road traffic crash involvement of young drivers, driver education courses should not be offered outside the context of a randomised controlled trial. Future driver education courses should aim to discourage early licensing.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 11 July 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2001 Review first published: Issue 3, 2001

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 18 May 2006 | New search has been performed | The electronic database searches have been updated; no new studies for inclusion were identified. |

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jon Vernick for providing copies of two of the randomised trials, as well as Reinhard Wentz and Karen Blackhall for their help with searching.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy

| CENTRAL 1. explode "Automobile‐Driving" / education in MIME,MJME 2. explode "Automobile‐Driving" / all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME 3. driving or driver* or automobile* or car or cars in TI,AB 4. #2 or #3 5. "Adolescent‐" / all SUBHEADINGS 6. "Adult‐Children" / all SUBHEADINGS 7. "Adult‐" / all SUBHEADINGS 8. young or youth* or teen* or adolescen* or student* in TI,AB 9. #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 10. educat* or train* or teach* in TI,AB 11. #4 and #10 12. (#1 or #11) and #9 |

| CIG's specialised register (driver* or driving) and (train* or teach* or course* or school* or educat*) and (young or youth* or teen* or adolescen*) |

| MEDLINE 1. explode "Automobile‐Driving" / education in MIME,MJME 2. explode "Automobile‐Driving" / all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME 3. driving or driver* or automobile* or car or cars in TI,AB 4. #2 or #3 5. "Adolescent‐" / all SUBHEADINGS 6. "Adult‐Children" / all SUBHEADINGS 7. "Adult‐" / all SUBHEADINGS 8. young or youth* or teen* or adolescen* or student* in TI,AB 9. #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 10. educat* or train* or teach* in TI,AB 11. #4 and #10 12. (#1 or #11) and #9 13. CLINICAL‐TRIAL in PT 14. (TG:MEDS = ANIMALS) not ((TG:MEDS = HUMANS) and (TG:MEDS = ANIMALS)) 15. #13 not #14 16. #12 and #15 |

| National Research Register 1. drive or driver* or driving 2. train* or teach* or course* or school* or educat* 3. young or youth* or teen* or adolescen* 4. #1 or #2 or #3 5. random* or intervention* or trial* or study or control* 6. #4 and #5 |

| TRANSPORT 1. DRIVER‐EDUCATION 2. DRIVER‐TRAINING 3. ((driver* or driving) near (train* or teach* or course* or school* or educat*)) in ti or ab) 4. #1 or #2 or #3 5. ((youth* or teen* or adolescen* or highschool or high‐school or school* or youth* or young or teen*)) in ti or ab) 6. #4 and #5 |

| SSCI on WOK 1. drive or driver* or driving 2. train* or teach* or course* or school* or educat* 3. young or youth* or teen* or adolescen* 4. #1 or #2 or #3 5. random* or intervention* or trial* or study or control* 6. #4 and #5 |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Effect of school‐based driver education.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Number of students licensed on course completion | 1 | 16338 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.04 [1.02, 1.05] |

| 1.1 Driver education vs control | 1 | 16338 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.04 [1.02, 1.05] |

| 2 Self and police‐reported accidents | 3 | 17868 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.98, 1.08] |

| 2.1 Driver education vs control | 3 | 17868 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.98, 1.08] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Effect of school‐based driver education, Outcome 1 Number of students licensed on course completion.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Effect of school‐based driver education, Outcome 2 Self and police‐reported accidents.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Stock 1983.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial (Allocation by central computer using a stratified random sampling plan). | |

| Participants | 16,338 high school students, who applied for driver education in DeKalb County high schools and who said that they wanted to get their license as soon as possible. | |

| Interventions | 1. The Safe Performance Curriculum (SPC): 72 hours of formal instruction and testing (n = 5464). 2. The Pre‐Driver Licensing Curriculum (PDL): the minimum training required to pass the driving test, involved 24 hours of formal instruction and testing (n = 5430). 3. Control group: No formal driver education apart from any teaching provided by their parents or by private driver training schools (n = 5444). | |

| Outcomes | The number of students who have been licensed before or within six months of their sixteenth birthday or the course completion date whichever is the later. The number of students who were involved as a driver in one or more accidents. |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Strang 1982.

| Methods | Cluster randomised controlled trial (Allocation within strata of state high schools, secondary technical schools, catholic secondary schools, independent secondary schools, employers of young men, technical colleges). Method of allocation concealment not described. | |

| Participants | 779 males aged 17 to 19 years holding a current learner permit and living in the Melbourne area. | |

| Interventions | 1. Shepparton On‐Road (SN): 11 hours of theoretical instruction, 5 hours on‐road and off‐road driving and 6 hours in‐car observation (n = 188). 2. Shepparton Off‐Road (SF): 11 hours of theoretical instruction, 5 hours off‐road driving and 6 hours in‐car observation (n = 178). 3. Royal Automobile Club of Victoria (RACV): 2 hours theoretical instruction and 5 hours off‐road driving (n = 217). 4. Control group: no formal training but were allowed to arrange driving practice or lessons during the course of the study (n = 196). | |

| Outcomes | Proportion of participants having at least one accident since being licensed. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Wynne‐Jones 1984.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial (Students were selected by ballot within each school, stratified by sex, either to attend the driving course or to be left to their own devices to learn to drive). Method of balloting and alllocation concealment not described). | |

| Participants | 848 secondary school students aged 15 to 18 years from 23 schools in Christchurch. About 60 students were deleted from the experiment because of failure to complete correctly the enrolment form, filling out more than one form, or being selected on some other non‐random basis. | |

| Interventions | 1. The Automobile Association driver training programme: 8 hours behind the wheel instruction, 8 hours as a passenger while another student is being instructed, 8 lectures on road traffic law and correct attitudes and 2 lectures on motor mechanics (n = 561). 2. Control group: left to their own devices to learn to drive (n = 227). | |

| Outcomes | Number of days from trial enrolment until driving license obtained (licensing delay). Accidents by self report. Accidents by official record. |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Dreyer 1979 | Lack of a no‐intervention group. |

| Gregersen 1994 | This study compared professional driver education versus no professional driver education (i.e private instruction from parents etc) in 1,894 Swedish teenagers who had yet to obtain a driving license. The study was excluded because allocation of participants was not random. Page 455: "The division could not be made strictly on a random basis since the experimental group was to attend driving schools, and it was necessary to reduce the geographical distance to the schools as much as possible. In certain small villages, all of those within the sample were picked for the experimental group." |

| Planek 1974 | Lack of a no‐intervention group. |

| Raymond 1973 | Intervention and control groups were not selected by random allocation. |

| Schuman 1971 | All participants were licensed drivers. |

| Schupack 1975 | All participants were licensed drivers. |

Contributions of authors

Cochrane Injuries Group Driver Education Reviewers (names listed alphabetically): Shirley Achara, Bola Adeyemi, Efunbo Dosekun, Suzanne Kelleher, Irene Kwan, Marilyn Lansley, Ian Male, Nermin Muhialdin, Lucy Reynolds, Ian Roberts, Mirsada Smailbegovic, Nick van der Spek.

Protocol development: All Screening: All Data extraction: IR, IK Trial quality assessment: IR, IK Drafting: All

Sources of support

Internal sources

London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, UK.

External sources

No sources of support supplied

Declarations of interest

None known.

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Stock 1983 {published data only}

- Davis CS. The DeKalb County, Georgia, Driver Education Demonstration Project: Analysis of its long term effects. Final Report. Iowa City, IO: University of Iowa, Department of Preventive Medicine 1990.

- Lund AK, Williams AF, Zador P. High school driver education: further evaluation of the DeKalb County Study. Accident Analysis and Prevention 1986;18:349‐57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock JR, Weaver JK, Ray HW, Brink JR, Sadoff MG. Evaluation of Safe Performance Secondary School Driver Education Curriculum Demonstration Project. Final Report. Washington, DC: US Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration 1983.

Strang 1982 {published data only}

- Strang PM, Deutsch KB, James RS, Manders SM. A Comparison of On‐Road and Off‐Road Driver Training. Victoria, Australia. Road Safety and Traffic Authority 1982.

Wynne‐Jones 1984 {published data only}

- Wynne‐Jones JD, Hurst PM. The AA Driver Training Evaluation. Traffic Research Report No. 33. Ministry of Transport, Road Transport Division, Wellington, New Zealand 1984.

References to studies excluded from this review

Dreyer 1979 {published data only}

- Dreyer D, Janke M. The effects of range versus non‐range driver training on the accident and conviction frequencies of young drivers. Accident Analysis and Prevention 1979;11(3):179‐98. [Google Scholar]

Gregersen 1994 {published data only}

- Gregersen NP. Systematic cooperation between driving schools and parents in driver education, an experiment. Accident Analysis and Prevention 1994;26(4):453‐61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Planek 1974 {published data only}

- Planek TW, Schupack SA. An evaluation of the National Safety Council's Defensive Driving Course as an adjunct to High School driver education programs, Part 1. National Safety Council, Research Department, Chicago, Il, USA 1974.

Raymond 1973 {published data only}

- Raymond S, Risk AW, Shaoul JE. An evaluation of driver education as a road safety measure. First International Conference on Driver Behaviour, Zurich, October 1973. Traffic Research Report No. 33. Ministry of Transport, Road Transport Division, Wellington, New Zealand 1984.

Schuman 1971 {published data only}

- Schuman SH, McConochie R, Pelz DC. Reduction of young driver crashes in a controlled pilot study. JAMA 1971;218(2):233‐7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schupack 1975 {published data only}

- Schupack SA, Planek TW. An evaluation of the National Safety Council's Defensive Driving Course as an adjunct to High School driver education programs, Part 2. National Safety Council, Research Department, Chicago, IL, USA 1975.

References to studies awaiting assessment

Weaver 1981 {published data only}

- Weaver JK, Stock JR, Ray H, Brink JR. Safe performance secondary school driver edcuation curriculum demonstration project. Annual report. USA National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, Office of Driver and Pedestrian Programs, Washington, DC, USA 1981.

Additional references

DETR 2000

- DETR. Tomorrow's roads: safer for everyone. London: Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions, 2000. [Google Scholar]

Gregersen 1996

- Gregersen NP. Young drivers' overestimation of their own skill ‐ an experiment on the relation between training strategy and skill. Accident Analysis and Prevention 1996;28(2):243‐50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

House of Commons

- House of Commons Hansard Debates for 19 December 2000.

Vernick 1999

- Vernick JS, Guohua L, Ogaitis S, MacKenzie EJ, Baker SP, Gielen AC. Effects of high school driver education on motor vehicle crashes, violations, and licensure. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 1999;16(1S):40‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

www.driving‐test.co.uk

- http://www.driving‐tests.co.uk.