Abstract

Background

Trifluoperazine is an inexpensive accessible 'high potency' antipsychotic drug, widely used to treat schizophrenia or related psychoses.

Objectives

To estimate the effects of trifluoperazine compared with placebo and other drugs.

Search methods

Searches of the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's register of trials (March 2002), supplemented with hand searching, reference searching, personal communication and contact with industry.

Selection criteria

All clinical randomised trials involving people with schizophrenia and comparing trifluoperazine with any other treatment.

Data collection and analysis

Studies were reliably selected and quality rated and data was extracted. For dichotomous data, relative risks (RR) were estimated, with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Where possible, we undertook intention‐to‐treat analyses. For statistically significant results, the number needed to treat (NNT) was calculated. We estimated heterogeneity (I‐square technique) and publication bias.

Main results

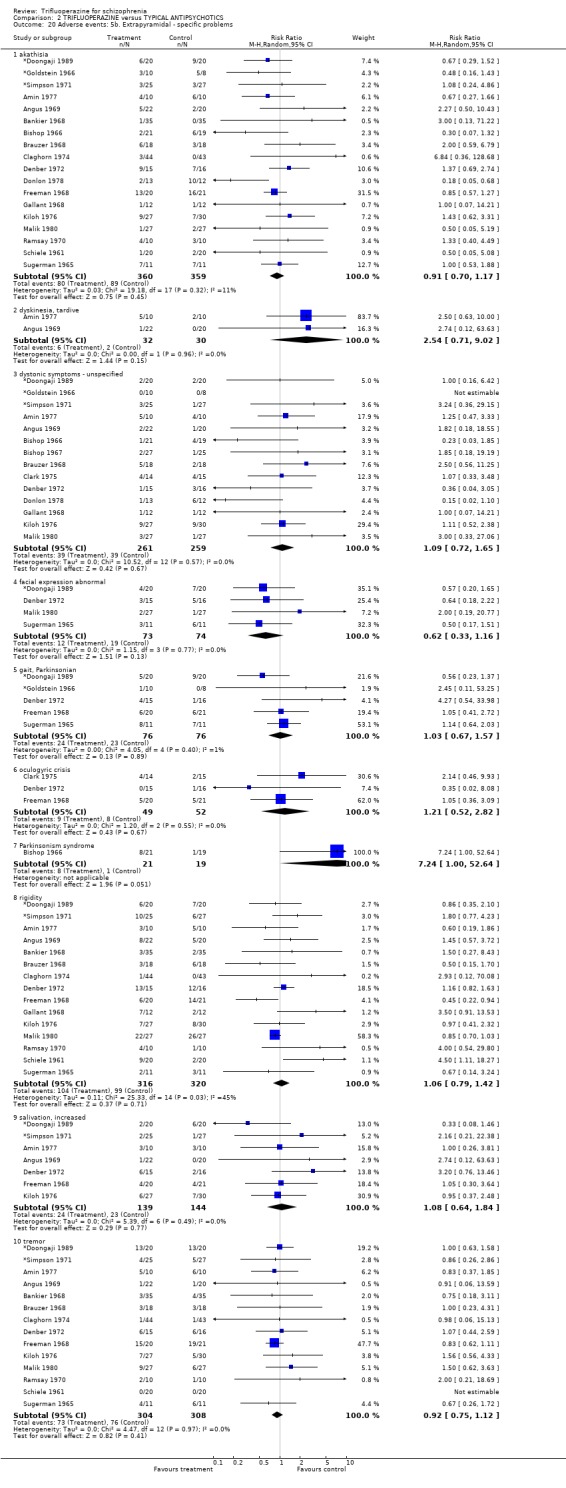

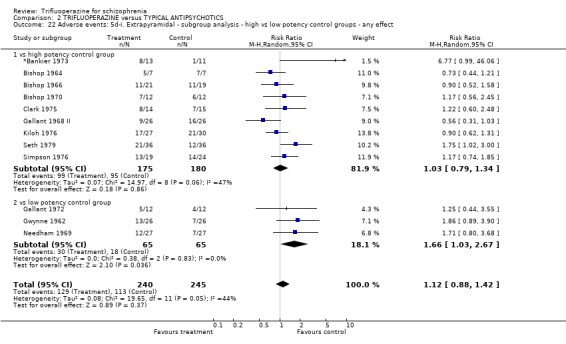

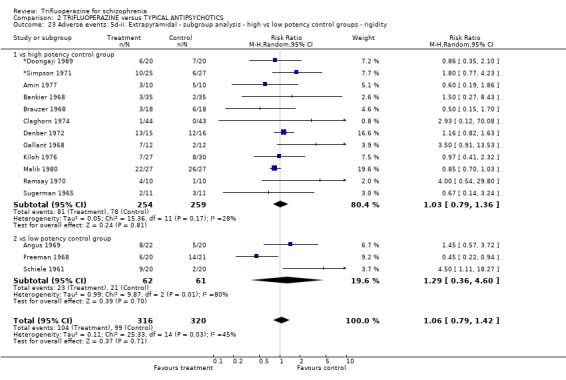

1162 people from 13 studies were randomised to trifluoperazine or placebo. For global improvement, small short‐term studies favoured trifluoperazine (n=95, 3 RCTs, RR 0.62 CI 0.49 to 0.78 NNT 3 CI 2 to 4). Loss to follow up was about 12% in both groups (n=280, 7 RCTs, RR 0.99 CI 0.62 to 1.57) and more people allocated trifluoperazine used antiparkinson drugs to alleviate movements disorders compared with placebo (n=195, 4 RCTs, RR 5.06 CI 2.49 to 10.27, NNH 4 CI 2 to 9). 2230 people from 49 studies were randomised to trifluoperazine or another older generation antipsychotic. Trifluoperazine was not clearly different in terms of 'no substantial improvement' (n=1016, 27 RCTs, RR 1.06 CI 0.98 to 1.14) or leaving the study early (n=930, 22 RCTs, RR 1.15 CI 0.83 to 1.58). Almost identical numbers of people reported at least one adverse event (˜60%) in each group (n=585, 14 RCTs, RR 0.99 CI 0.87 to 1.13), although trifluoperazine was more likely to cause extrapyramidal adverse effects overall when compared to low potency antipsychotics such as chlorpromazine (n=130, 3 RCTs, RR 1.66 CI 1.03 to 2.67, NNH 6 CI 3 to 121). One small study (n=38) found no clear differences between trifluoperazine and the atypical drug, sulpiride.

Authors' conclusions

Although there are shortcomings and gaps in the data, there appears to be enough consistency over different outcomes and periods to confirm that trifluoperazine is an antipsychotic of similar efficacy to other commonly used neuroleptics for people with schizophrenia. Its adverse events profile is similar to that of other drugs. It has been claimed that trifluoperazine is effective at low doses for patients with schizophrenia but this does not appear to be based on good quality trial based evidence.

Plain language summary

Trifluoperazine for schizophrenia

Trifluoperazine is inexpensive and widely accessible. Thousands of people with schizophrenia have participated in studies and therefore we are reasonably sure that it is a potent antipsychotic drug and as good as similar older drugs. Most people taking it do experience adverse effects, but this also applies to other older drugs. Not enough comparisons with newer generations of drugs have been undertaken to be sure of how trifluoperazine compares to them.

Background

The most commonly prescribed antipsychotic drugs (chlorpromazine, haloperidol and trifluoperazine), are the benchmarks against which all others are compared. They have too rarely been the subjects of quantitative, systematic reviews. Now that synthesis of trials comparing placebo with chlorpromazine, and placebo with haloperidol, for people with schizophrenia are maintained in the Cochrane Library (Thornley 2001, Joy 2001), only trifluoperazine remains to be reviewed.

Trifluoperazine is a long‐established, widely used 'conventional' antipsychotic drug. It has been claimed that it is effective at low doses (Ban 1966, Bazire 2000, Reardon 1989). Trifluoperazine has been considered effective and safe since the 1960s (Reardon 1989, APA 1997), and is considered a first‐line drug for people in the acute phase of schizophrenia (APA 1997). Conventional antipsychotic medications vary, both in potency and propensity to induce adverse effects such as, the so‐called 'extrapyramidal adverse effects', or EPS. With EPS, the normally fluid movements of everyday living become stiff and tremulous, facial expression becomes limited and some repetitive movements of the mouth and face may become gross and disfiguring. These EPS are said to occur more frequently with 'high‐potency' compounds such as haloperidol and trifluoperazine. Sedation and low blood pressure, so often associated with antipsychotic drugs, is said to be less frequent with the 'high potency' trifluoperazine (APA 1997).

The search to identify antipsychotic drugs with minimal adverse effects, and a broader spectrum of efficacy, has produced a class of drug known as atypical antipsychotics. As a group, it is claimed that these cause reduced EPS and have some efficacy in the treatment of the negative symptoms of schizophrenia (apathy, inability to express emotions, poverty of speech and lack of motivation). From the whole class of 'atypicals' , only clozapine has proved to be more potent for treating refractory symptoms (Wahlbeck 2001, Duggan 2002, Hunter 2003), although even this is in question (Geddes 2000). Atypical antipsychotics are more expensive than the conventional drugs, and cost has become part of the controversy concerning their prescribing (Wood Mackenzie 1998, Meltzer 1996). Cost is a major influence on accessibility of treatments, especially for middle or low‐income countries.

Technical background Trifluoperazine is a phenothiazine derivative, 10‐[3‐(4‐methyl‐1‐piperazinyl)propyl]‐2‐trifluoromethylpheno thiazine(hydrochloride), sold as Stelazine by GlaxoSmithkline (tablets of 1mg, 2 mg, 5mg and 10 mg). The daily dose ranges from 12 to 50 mg (APA 1997). It may be administered orally once or twice a day.

Trifluoperazine is related chemically to chlorpromazine, but it has high milligram potency, and an adverse effect profile (mainly the incidence of extrapyramidal symptoms) similar to haloperidol (Luckey 1967). It has a specific action on the brain: D2 receptors blockade. The blockade of postsynaptic D2 receptors in mesolimbic and mesocortical projection is responsible for initiating the therapeutic actions of typical antipsychotic drugs. The blockade in striatum is responsible for the extrapyramidal effects and in the tuberoinfundubular system of the hypothalamus can produce hyperprolactinemia (Arana 2000). Although D2 blockade takes hours, clinical effects usually take weeks, probably because the decrease of homovallinic acid levels (principal metabolite of dopamine) is expected to take several weeks (Bazire 2000). The risk of extrapyramidal reactions (pseudo parkinsonism, acute dystonic reaction, akathisia and tardive dyskinesia) is suggested to be higher than in other phenothiazines. Trifluoperazine has a low potency of cholinergic blockade (confusion, agitation, dry mouth, blurred vision, urinary retention) and causes less sedation and orthostatic hypotension (histaminic and alpha‐adrenergic antagonism). It is usually well tolerated (Kaplan 1998).

Objectives

To examine the effects of trifluoperazine compared to placebo, and other antipsychotic drugs, for people with schizophrenia.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All relevant randomised controlled trials were included. Where a trial was described as 'double‐blind' but it was implied that the study was randomised and the demographic details of each group were similar, it was included. Quasi‐randomised studies, such as those allocated by using alternate days of the week, were excluded.

Types of participants

People with schizophrenia and non‐affective serious/chronic mental illness irrespective of mode of diagnosis, age, sex and chronicity of illness.

Types of interventions

1. Trifluoperazine: any dose and mode or pattern of administration. If a high/low dichotomy was not provided within the trial, high dose was defined as over 30 mg/day, and low dose as any lesser dose. If different doses of trifluoperazine were randomised these studies were also of interest.

2. Placebo.

3. Other typical antipsychotics: any dose and mode or pattern of administration. Examples of such drugs are chlorpromazine and haloperidol.

4. Atypical antipsychotics: any dose and mode or pattern of administration. Examples of such drugs are clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone.

Types of outcome measures

As schizophrenia is often a life‐long illness, and trifluoperazine is used as an ongoing treatment, outcomes were grouped according to time periods: immediate (seven days or less), short term (eight days to three months), medium term (> three months to one year) and long term (more than one year).

Primary outcomes

1. Service utilisation outcomes 1.1 Hospital admission.

2. Global outcomes 2.1 No clinically significant response in global state ‐ as defined by each of the studies.

3. Mental state 3.1 No clinically significant response in mental state ‐ as defined by each of the studies.

4. Extrapyramidal adverse effects 4.1 Incidence of use of antiparkinsonian drugs.

Secondary outcomes

1. Death 1.1 Suicide. 1.2 Other causes.

2. Service utilisation outcomes 2.1 Days in hospital. 3. Global outcomes 3.1 Average score/change in global state.

4. Mental state 4.1 Average score/change in mental state. 4.2 No clinically significant response on negative symptoms ‐ as defined by each of the studies. 4.3 Average score/change in negative symptoms. 4.4 Relapse as defined in the study.

5. Behaviour 5.1 Leaving the study early. 5.2 No clinically significant response in behaviour ‐ as defined by each of the studies. 5.3 Average score/change in behaviour.

6. Extrapyramidal adverse effects 6.1 No clinically significant extrapyramidal adverse effects ‐ as defined by each of the studies. 6.2 Average score/change in extrapyramidal adverse effects.

7. Other adverse effects, general and specific 7.1 Number of people dropping out due to adverse effects. 7.2 Cardiac effects. 7.3 Anticholinergic effects. 7.4 Antihistaminic effects. 7.5 Prolactin related symptoms.

8. Social functioning 8.1 No clinically significant response in social functioning ‐ as defined by each of the studies. 8.2 Average score/change in social functioning.

9. Economic outcomes

10. Quality of life/ satisfaction with care for either recipients of care or careers. 10.1 Significant change in quality of life / satisfaction ‐ as defined by each of the studies. 10.2 Average score/change in quality of life / satisfaction. 10.3 Employment status.

11. Cognitive functioning

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Trifluoperazine is known by many names. We constructed the following search phrase to assist identification:

Trifluoperazine‐phrase = *10‐[3‐(4‐methyl‐1‐piperazinyl)propyl]‐2‐trifluoromethylpheno thiazine (hydrochloride)* or *terfluzine* or *terfluzinor discimer* or *eskazine foille* or *iremo* or *piero* or *jatroneural* or *modalina* or *oxyperazine* or *sedofren* or *sporalon* or *stelazine* or *stelazina* or *stelium* or *terflurazine* or *terfluoperazine* or *SKF 5019* or *7623 RP* or *trifluoperazine* or *Solazine*.

1. The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Register (March 2002) was searched using the phrase:

{[(trifluoperazine‐phrase) in title, abstract or index terms of REFERENCE] or [*trifluoperazine* in interventions of STUDY]}

This register is compiled by methodical searches of BIOSIS, CINAHL, Dissertation abstracts, EMBASE, LILACS, MEDLINE, PSYNDEX, PsycINFO, RUSSMED, Sociofile, supplemented with hand searching of relevant journals and numerous conference proceedings (see Group Module).

Searching other resources

1. Reference searching References of all identified studies were also inspected for more trials. SCISEARCH ‐ Science Citation Index (1974 to 2001) was used to trace papers that had cited included trials. These reports were inspected in order to identify further studies.

2. Personal contact The first author of each included study was contacted for information regarding unpublished trials.

3. Industry Pharmaceutical companies were contacted for additional data or reports of trials.

Data collection and analysis

1. Selection of trials All reports of identified studies were inspected by the principal reviewer (LOM). A random sample of ten percent of reports was re inspected by MSL in order to ensure reliability of selection. Where disagreement occurred this was resolved by discussion, or, when there was still doubt, reviewers acquired the full article for further inspection. Once the full articles were obtained LOM decided whether they met review criteria and this was checked by MSL on a 10% sample. Again, if disagreement occurred this was resolved by discussion and when this was not possible further information was sought. These trials were added to the list of those awaiting assessment pending acquisition of this further information. 2. Quality assessment Trials were classified into three quality categories, as described in the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook (Clarke 2001) by the lead reviewer (LOM). A random sample (10%) of trial reports was re inspected by MSL. When disputes arose regarding which category a trial should be allocated to, again, resolution was attempted by discussion. When this was not possible, and further information was necessary, data were not entered into the analyses and the study was allocated to the list of those awaiting assessment. Only trials in Category A or B were included in the review. 3. Data extraction Data from selected trials were extracted twice by LOM blind to the first extraction. A random selection were independently re inspected by MSL (10%). When disputes arose reviewers attempted resolution by discussion. If doubt remained and further information was necessary to resolve the dilemma, reviewers did not enter the data and added them to the list of those awaiting assessment, pending further information.

4. Data synthesis 4.1 Data types Outcomes are assessed using continuous (for example, average changes on a behaviour scale), categorical (for example, one of three categories on a behaviour scale, such as 'little change', 'moderate change' or 'much change') or dichotomous measures (for example, either 'no important changes' or 'important changes' in a person's behaviour). RevMan software does not currently support categorical data so they were only presented in the text of the review. 4.2 Incomplete data With the exception of the outcome of leaving the study early, trial outcomes were not included if more than 40% of people were not reported in the final analysis. Reviewers felt that such a degree of attrition would threaten the validity of any findings. 4.3 Dichotomous data Where the original authors of the studies gave outcomes such as 'clinically improved' or 'not clinically improved' based on their clinical judgment, predetermined criteria or any scale, this was recorded in RevMan. If data was from a rater not clearly stated to be independent then it was only included if it did not change the results, otherwise it was presented separately with a label 'prone to bias'.

Where possible, efforts were made to convert relevant categorical or continuous outcome measures to dichotomous data by identifying cut off points on rating scales and dividing people accordingly into groups. We used the cut off points 'moderate or severe impairment' for end of study data or 'no better or worse' for change data. For example, the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS ‐ Overall 1962) is frequently used as a measure of change of symptoms in studies. The reviewers defined a 50% change on this particular scale as clinically important, although it was recognised that for many people, especially those with chronic or severe illnesses, a less rigorous definition of important improvement, for example, 25% on the BPRS, would be equally valid. If individual patient data were available, the 50% cut off was used for non‐chronically ill people and 25% for those with chronic illness.

This review presents an intention to treat analysis. As long as over 60% of people completed the study, everyone allocated to the intervention was counted whether or not they completed follow up. It was assumed that those who left the study early had a negative outcome, with the exception of the outcome of death. Also with regard to 'reasons for leaving the study early' because of adverse events or relapse, only patients not accounted for were assumed to have a negative outcome. This was felt to be a more reasonable interpretation of limited data. These data were included as long as this did not change the results. This was tested by a sensitivity analysis.

Where trialists presented data as 'last result carried forward' for those who left the study early, these data were only included if they did not change the overall results, otherwise, they were presented separately with the label 'prone to bias'. Where there was genuine uncertainty as to how the trialists had handled data, this uncertainty was tested using a range of possible missing values. If this affected the results then it was presented separately with a label 'prone to bias'.

We used relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) based on the random effects model as the preferred statistic for summation, as this takes into account differences between studies even if heterogeneity is not statistically significant. Data were inspected to see if analysis using a Mantel‐Haenszel odds ratio and fixed effects models made a substantive difference. Where possible, reviewers estimated the number needed to treat / harm (NNT/H). 4.4 Continuous data In the case of continuous data, completer analysis is presented. 4.4.1 Rating scales A wide range of instruments is available to measure mental health outcomes. These instruments vary in quality and many are not valid, or even ad hoc. For outcome instruments some minimum standards have to be set. They are that: i. the psychometric properties of the instrument should have been described in a peer‐reviewed journal; ii. the instrument should either be a self‐report, or completed by an independent rater or relative (not the therapist); and iii. the instrument should be a global assessment of an area of functioning. 4.4.2 Normal distribution Mental health continuous data are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data the following standards were applied to all data before inclusion: i. standard deviations and means were reported in the paper or were obtainable from the authors; ii. if the data were finite measures from, for example 0‐100, when the standard deviation was multiplied by two, the result should be less than the mean, otherwise the mean was unlikely to be an appropriate measure of the centre of the distribution (Altman 1996). Continuous data, if normally distributed, were summated using a calculation of the weighted mean difference (WMD). Non‐normally distributed data were reported in the 'Other data types' tables. Endpoint scale‐derived data is finite, ranging from one score to another. Change data is more problematic and for it the rule described above does not hold. Although most change scores are likely to be skewed, it cannot be proven, so they were presented in MetaView. Where both endpoint and change were available for the same outcome the reviewers presented the former in preference. 4.5 Sensitivity analyses 4.5.1 Primary outcomes for an intention‐to‐treat analysis were compared with those from a completer‐only analysis.

4.6 Subgroup analysis 4.6.1 Trials that used low doses of trifluoperazine were compared with those where high doses (over 30 mg/day) were employed.

4.6.2 Studies with less than 40% of people leaving early were compared with those with higher rates.

5. Heterogeneity As well as inspecting the graphical presentations, the reviewers checked whether the differences between results of trials were greater than would be expected by chance alone using tests of heterogeneity (Chi squared). A significance level of less than 0.10 was interpreted as evidence of heterogeneity. When heterogeneity was present, a sensitivity analysis was undertaken. Outlying studies were removed from the pooled measure if they caused a substantive change in the overall findings and these data were presented and discussed separately.

6. Assessing the presence of publication bias Data from all included trials were entered into a funnel graph (trial effect versus trial size or 'precision') in an attempt to investigate the likelihood of overt publication bias. A formal test of funnel plot asymmetry (which suggests potential publication bias) was undertaken where appropriate, according to the methods of Egger 1997. Significance levels of p < 0.1 were set a priori to detect the presence of asymmetry. Where only 3‐4 studies reported an outcome, or there was little variety in sample size (or precision estimate) between studies, tests of asymmetry were not appropriate.

7. Tables and figures Where possible, data were entered into RevMan so the area to the left of the line of no effect indicated a favourable outcome for trifluoperazine.

Results

Description of studies

Please also see Included and Excluded studies tables.

1. Awaiting assessment Four studies have been ordered but not yet obtained (Toru 1969, Gallant 2000, Kogeorgos 1995, Ortega‐Soto 1996). A further eighteen did not fulfil inclusion criteria but we have contacted the authors and await their response before these are excluded. One Polish paper has not yet been translated (Terminska 1989).

2. Excluded studies The majority of excluded studies either did not have a control group (n=7) or were not stated to be randomised (n=32). Some randomised studies used interventions that were not the focus of this review or involved people who did not suffer from schizophrenia (n=7). Ten randomised trials had to be excluded as no data were usable, for example, one was a crossover study with no information for the first stage. Two trials did not report the number of people randomised to each group.

3. Included studies Fifty studies were included.

3.1 Methods All included studies were described as randomised. Follow‐up periods ranged from three days to 13 months. Twenty‐eight were in the short duration category (less than three months) and six were of intermediate duration (three months to one year). Only one was over one year (long duration, Donlon 1978).

3.2 Participants The number of people in the included studies ranged from 18 to 360 (mean 52 SD 50). 47% of studies had 40 or fewer participants but a total of 2583 people have participated in the 50 trials.

From the studies reporting information on the sex of participants, there were 1271 men and 971 women. Ages ranged from 14 to 74 years (mean from 18 studies was about 43 years). Only two studies specifically focused on adolescents (Bagadia 1980, Malik 1980).

Most participants had a diagnosis of schizophrenia although some studies were included if most people had schizophrenia or a schizophrenia‐like illness. For example, Coons 1962 reported that 79% of participants had schizophrenia, and Marjerrison 1964 and Denber 1972 that over 80% of included people suffered from schizophrenia. Rubin 1971 included one person with manic‐depressive disorder and Brauzer 1968 included a single person with chronic brain syndrome with psychoses. Andersen 1974 randomised 40 people with schizophrenia or "paranoid syndrome" and the participants in O'Brien 1974 were 30 people with hostility, suspiciousness, paranoia and aggressiveness.

Only nine studies described the diagnostic criteria used; the remainder appeared to have made a clinical diagnosis without the use of operational criteria. Many trials (n=30) involved only people with chronic illness, two during an acute exacerbation of this illness. Two studies involved people whose illness was designated as highly treatment resistant. The remainder included acutely ill people and first episode patients.

3.3 Setting Most studies were conducted in inpatient settings. Only six trials included only people who were not in hospital. Most trial centres were in USA (30) or Canada (10). Five were in India, two in Australia, two in Europe (Sweden, UK) and one in Peru.

3.4 Interventions The mean dose of trifluoperazine, based on the 25 studies which reported it, was about 28 mg/day (SD ˜20 mg/day, median 26 mg/day) and the range, taken from 35 studies, was 4 to 100 mg/day. Three studies used intramuscular trifluoperazine (Brauzer 1968, Gallant 1968 II, Perales 1974).

Eleven studies employed a separate placebo arm. Forty‐nine studies compared trifluoperazine with oral typical antipsychotics (for comparison compounds and their frequency of use please see Table 4). For the purposes of this review, loxapine and molindone are considered as typical drugs. Only Edwards 1980 compared trifluoperazine to an atypical antipsychotic (sulpiride). Twenty‐four studies stated they used other medications to alleviate adverse effects or problematic behaviour as required. These drugs included benztropine mesylate, biperiden, trihexphenidyl, chloral hydrate, metyprylon, phenobarbital, chlorpromazine, thioridazine, and short action sedatives. Rubin 1971 reported that some patients received psychotherapy in addition to medication.

1. Comparison compounds used in trifluoperazine studies.

| Drug | Number of studies |

| loxapine | 7 |

| pimozide | 6 |

| thiothixene | 4 |

| molindone | 4 |

| SKF 14336 ‐ acridan derivative | 4 |

| chlorpromazine | 4 |

| haloperidol | 4 |

| trifluperidol | 3 |

| fluphenazine | 1 |

| fluspirilene | 1 |

| penfluridol | 1 |

| cetbutindole | 1 |

| triperidol | 1 |

| clorprothixene | 1 |

| clothiapine | 1 |

| butaperazine | 1 |

| SKF 7261 | 1 |

| GP‐45795 | 1 |

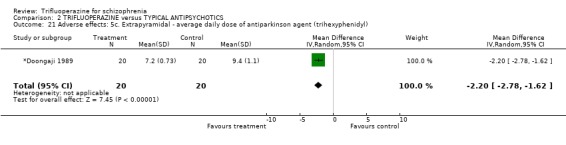

3.5 Outcomes Most outcomes were reported as dichotomous (yes‐no/binary outcomes), and are presented as such. Scale derived data was usually categorical and therefore easily dichotomised. Four studies used the Clinical Global Impression (Guy 1976) and reported categorical data. Another 27 studies, undertaken before 1976, used comparable data to report global ratings of improvement. Thirty five studies used the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (Overall 1962) and 17 employed the Nurses Observational Scale of Inpatients Evaluation (NOSIE, Honingfeld 1965) but these data were either impossible to extract from graphs or so incomplete as to render them unusable. Menon 1972 reported dichotomous global state data on the Wings rating Scale. *Doongaji 1989 provided continuous data on mean daily dose of an antiparkinson agent but information collected on adverse events and side effects was not standardised.

3.5.1 Scales

3.5.1.1 Global State Clinical Global Impression ‐ CGI (Guy 1976) CGI is a rating instrument commonly used in studies on schizophrenia that enables clinicians to quantify severity of illness and overall clinical improvement during therapy. A seven‐point scoring system is usually used, with low scores indicating decreased severity and/or greater recovery. In this review, absence of clinical improvement was considered to be when patients had moderate, slight or no improvement. 3.5.1.2 Mental state Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale ‐ BPRS (Overall 1962) A brief rating scale used to assess the severity of a range of psychiatric symptoms, including psychotic symptoms. The original scale has 16 items, but a revised 18‐item scale is commonly used. Each item is defined on a seven‐point scale varying from 'not present' to 'extremely severe', scoring from 0‐6 or 1‐7. Scores can range from 0‐126, with high scores indicating more severe symptoms.

3.5.1.3 Behaviour Nurses Observational Scale of Inpatients Evaluation ‐ NOSIE (Honingfeld 1965). An 80‐item scale which ranks items from 0‐4 (0=never present). Ratings are taken from behaviour over the previous three days. The seven headings are: social competence, social interest, personal neatness, co‐operation, irritability, manifest psychosis and finally, psychotic depression. Scoring ranges from 0‐320.

Wing Behaviour Rating Scale (Wing 1961) This scale consists of two parts. The first rates four typical symptoms of schizophrenic mental state, based on a brief psychiatric interview, on a 5‐point scale. The second is a 12‐item behavioural schedule that rates on a three‐point scale. The more acute the patient's condition, the higher the score on the scale.

3.5.1.4 Adverse events Treatment Emergent Symptoms Scale ‐ TESS (Guy 1976) This side effect tool is a checklist where the degree and severity of an adverse event is recorded. The TESS records the presence or absence of a list of side effects.

3.5.2 Missing outcomes No study reported on negative symptoms, neither were there usable cognitive outcomes. Death, suicide or self‐harm were not mentioned in any of the trials. Only one included study attempted to quantify levels of satisfaction or quality of life (Malik 1980) and no trial attempted to any direct economic evaluation of trifluoperazine.

Risk of bias in included studies

1. Randomisation Only four studies described the method used to generate random allocation (Clark 1975, Edwards 1980, Perales 1974, *Pinard 1972). All used tables of random numbers. Eleven trials reported that allocation was undertaken independently (Angus 1969, Clark 1975, Coons 1962, Edwards 1980, Needham 1969, O'Brien 1974, Perales 1974, Schiele 1969, *Simpson 1971, Simpson 1976). Coons 1962 described a form of allocation concealment (sealed envelopes). Denber 1972 and Sugerman 1965 reported that the random code was unknown until the end of study. For the other studies little assurance was given that bias was minimised during the allocation procedure. Twenty‐six studies reported that the numbers allocated to each treatment group were identical, without reporting the use of block randomisation. When allocating by chance this is improbable.

2. Blinding Thirty‐six of the fifty included trials described precautions taken to make the investigation blind (identical capsules). Two studies (Gallant 1968 II, Gallant 1972) gave no indication that blinding had been attempted. Menon 1972 reported that only research workers were blind. The remaining eleven trials indicated that an attempt at blinding had been made, but they gave no description of how this had been undertaken.

3. Loss to follow‐up Thirty‐two studies gave data on loss to follow‐up and 15 reported a full breakdown of the reasons for leaving the study.

4. Data reporting This was generally poor. Overall very little of the data from the fifty included trials was usable. Continuous data were particularly problematic. The most common reason for exclusion was lack of standard deviations and/or failure to give any information about outcomes at all. Many studies also presented findings in graphs, in percentiles or by inexact p‐values. 'P'‐values are commonly used as a measure of association between intervention and outcomes instead of showing the strength of the association. We were unable to carry out an intention to treat analysis in some studies because the data on leaving the study early were not provided or were not fully or not clearly reported. These studies were preceded by a '*'.

5. Overall quality Only studies allocated to Category A or B according to the Cochrane Handbook criteria were included in this review. As only twelve studies could be allocated to Category A, the data from the remaining 38 studies must be considered to be prone to a moderate degree of bias.

Effects of interventions

1. The search The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Register (March 2002‐ BIOSIS, CINAHL, Dissertation abstracts, EMBASE, LILACS, MEDLINE, PSYNDEX, PsycINFO, RUSSMED, Sociofile, supplemented with hand searching of relevant journals and numerous conference proceedings) provided 124 records. Of these, after removal of duplicates, 99 were obtained as full publications. A further 25 were acquired after hand searching the references, but only two of the latter could be included. Contacting authors of included studies has not yielded further studies. To date, contacting the relevant drug company (GlaxoSmithkline) has not led to further usable data. Fifty eight publications were sufficiently close to the review's inclusion criteria but had to be excluded (see Excluded Studies table). Twenty three papers or studies still await assessment.

2. COMPARISON 1. TRIFLUOPERAZINE versus PLACEBO A total of 1162 patients from 13 studies were randomised to this comparison.

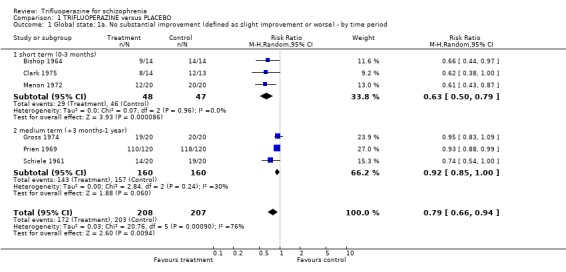

2.1 Global state Studies presented data on global impression in several ways. Three small short‐term studies (three months or less) favoured trifluoperazine (n=95, RR not substantially improved 0.62 CI 0.49 to 0.78, NNT 3 CI 2 to 4). At six months, three other studies tended to favour trifluoperazine (n=320, RR not substantially improved 0.93 CI 0.86 to 1.0). When all information was pooled, heterogeneous data (p=0.0002, I2 79%) favoured trifluoperazine (n=415, RR not substantially improved 0.79 CI 0.67 to 0.94, NNT 6.5 CI 5 to 10).

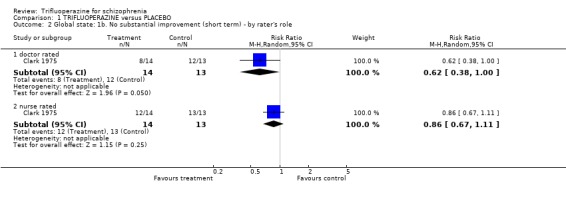

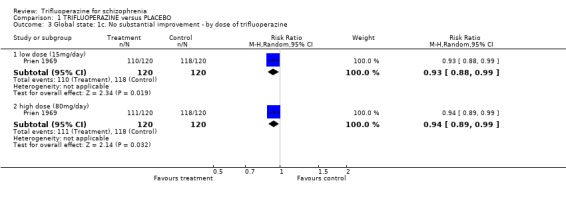

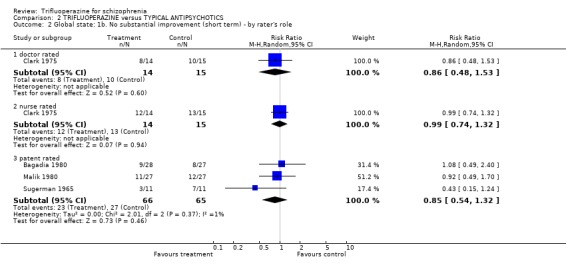

Clark 1975 compared ratings by nurses and doctors for this outcome. This small study (n=27) found no significant differences, although doctors did tend to rate the experimental group more favourably. Prien 1969 evaluated different doses of trifluoperazine compared with placebo and found no clear differences in response.

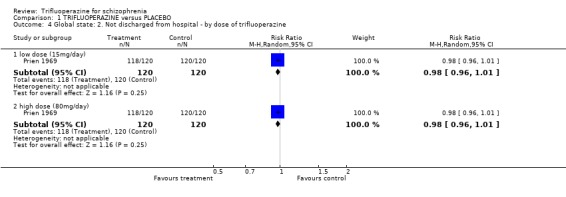

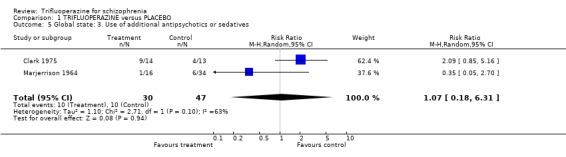

One study provided data on whether or not patients were discharged from hospital (Prien 1969). Most people were in hospital throughout this study and treatment with either high or low dose trifluoperazine made little difference (n=240, RR not discharged on low dose trifluoperazine 0.98 CI 0.96 to 1.01). Two trials reported on 'use of additional antipsychotics/sedatives'. There was no clear difference between trifluoperazine and placebo (n=77, 2 RCTs, RR 1.07 CI 0.18 to 6.31).

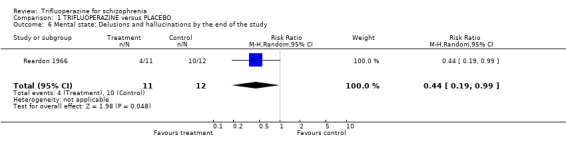

2.2 Mental state Only Reardon 1966 (n=23) directly reported mental state outcomes. Delusions and hallucinations were a little less prevalent for people given trifluoperazine (RR 0.44 CI 0.19 to 0.99, NNT 3 CI 5 to 100).

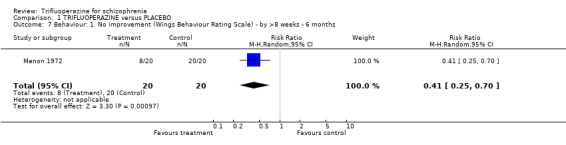

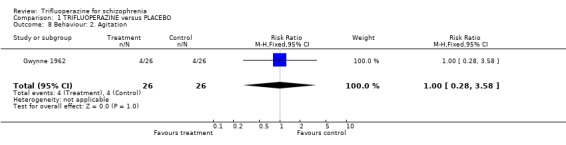

2.3 Behaviour Only one small study reported overall impression of effects on behaviour (Menon 1972). Dichotomised data from the Wings Behaviour Rating Scale favoured trifluoperazine (n=40, RR 0.4 CI 0.23 to 0.68). Another small study reported data on whether a person was agitated (Gwynne 1962, n=52). Trifluoperazine did not seem to have much advantage over placebo (RR agitation 1.0 CI 0.22 to 4.51).

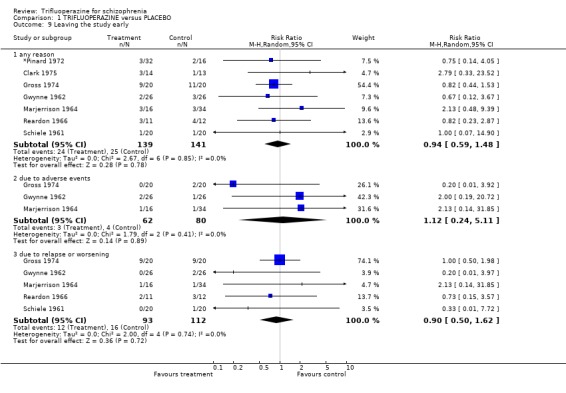

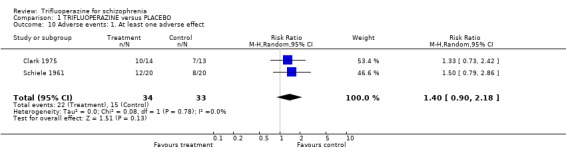

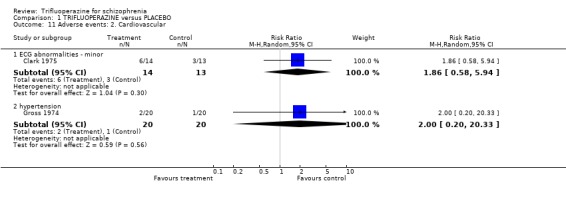

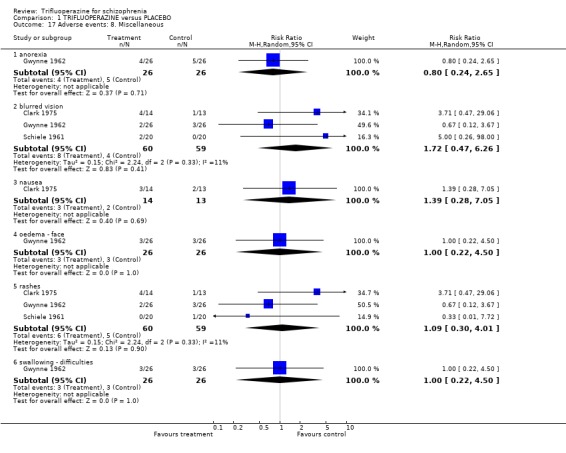

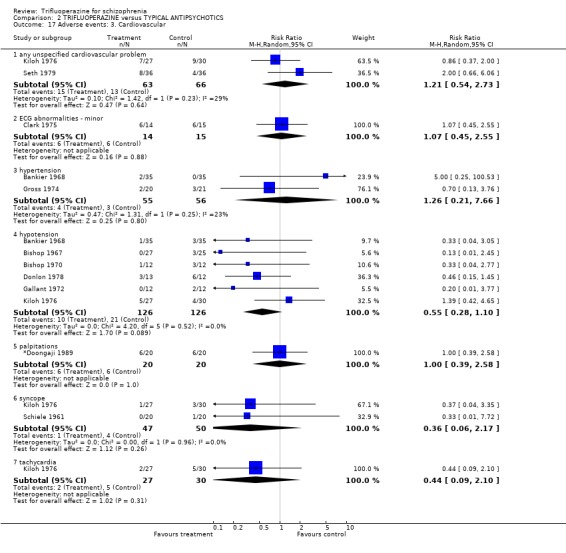

2.4 Leaving the study early There was no significant difference between trifluoperazine and placebo for the outcome 'leaving for any reason' (n=280, 7 RCTs, RR 0.99 CI 0.62 to 1.57). Nearly thirteen percent of the trifluoperazine group left early compared to 11.6% of people allocated to placebo. When different reasons for leaving early the study were analysed separately, this result did not change. 2.5 Adverse events When studies reported on the non‐specific outcome of 'any adverse event', trifluoperazine was no more likely to cause this than placebo (n=77, 2 RCTs, RR 1.4 CI 0.90 to 2.18). Most adverse event data comes from one or two small studies and selective reporting could be an issue. Cardiovascular problems such as minor ECG abnormalities (˜40% of participants in the one study that recorded them, Clark 1975) and hypertension were equally common in the trifluoperazine and placebo groups.

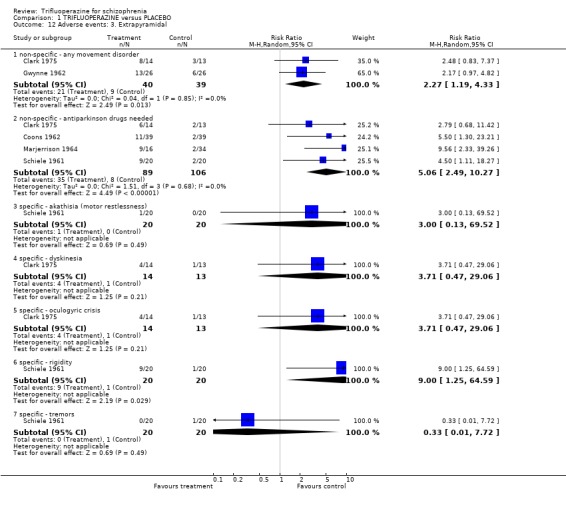

Trifluoperazine may well cause more extrapyramidal events than placebo (n=70, 2 RCTs, RR any moment disorder 2.27 CI 1.19 to 4.33, NNH 4 CI 2 to 23) and more people in the trifluoperazine group used antiparkinson drugs to alleviate movements disorders (n=195, 4 RCTs, RR 5.06 CI 2.49 to 10.27, NNH 4 CI 2 to 9). Other studies reported on more specific movement disorders such as oculogyric crisis (n=27, 1 RCT, RR oculogyric crisis 3.71 CI 0.47 to 29.06) and akathisia but were too underpowered to highlight a real difference. Most results, however, did suggest that trifluoperazine does tend to cause a full spectrum of movement disorders.

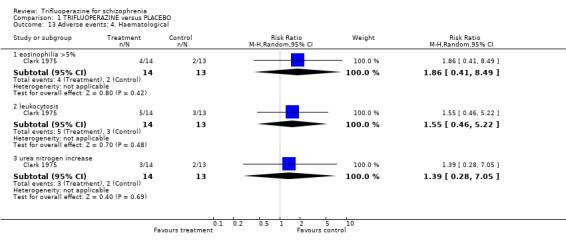

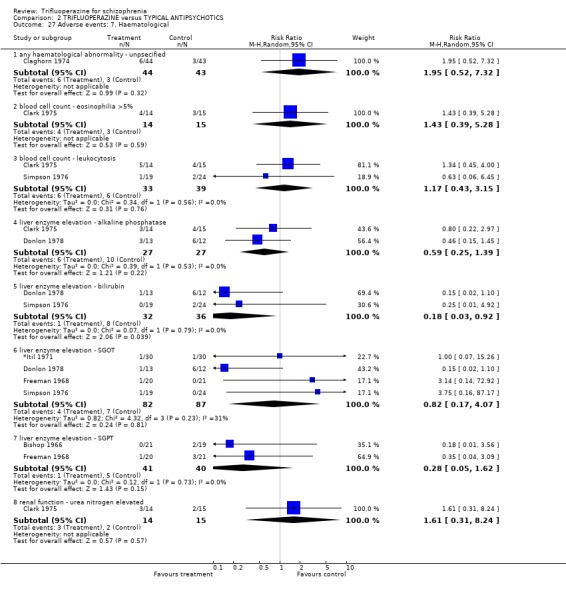

Only one study reported haematological outcomes (Clark 1975, n=27). Such disorders were rare and trifluoperazine did not seem implicated.

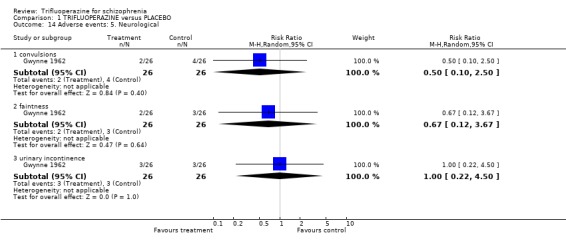

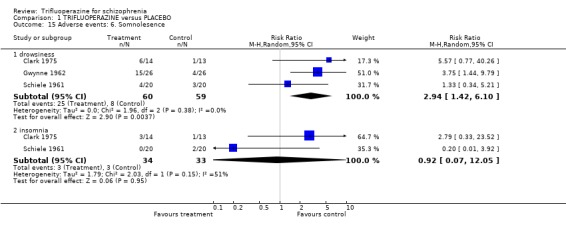

Gwynne 1962 (n=52) reported neurological outcomes and trifluoperazine did not clearly cause convulsions (RR 0.50 CI 0.10 to 2.50), or faintness (RR 0.67 CI 0.12 to 3.67). Trifluoperazine may, however, be sedating (n=119, 3 RCTs, RR 2.94 CI 1.42 to 6.10, NNH 4 CI 2 to 18).

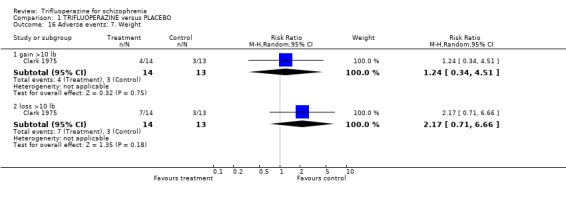

More people given trifluoperazine lost weight (7/14) than gained it (4/14) but neither effect was statistically significant (Clark 1975). Trifluoperazine may cause more blurred vision than placebo (n=119, 3 RCTs, RR 1.72 CI 0.47 to 6.26).

3. COMPARISON 2. TRIFLUOPERAZINE versus TYPICAL ANTIPSYCHOTIC This comparison includes 2230 people from 49 studies.

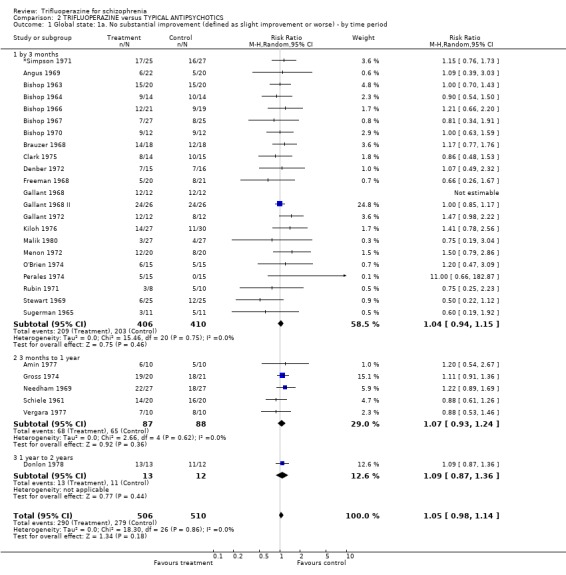

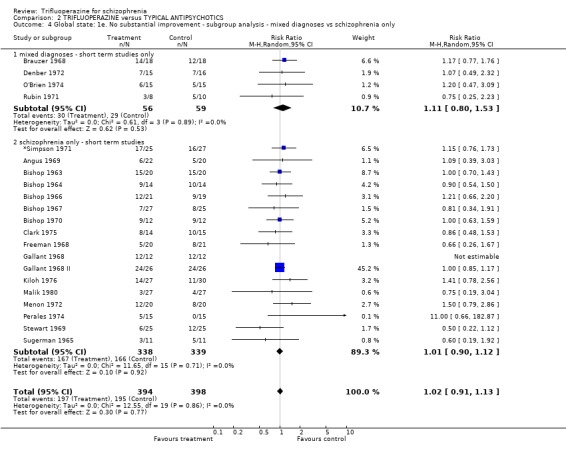

3.1 Global state In terms of the outcome of 'no substantial improvement', trifluoperazine was not clearly different than other older generation drugs (n=1016, 27 RCTs, RR 1.06 CI 0.98 to 1.14). This applies to the short term (n=816, 21 RCTs, RR 1.04 CI 0.94 to 1.15), medium term (n=175, 5 RCTs, RR 1.07 CI 0.93 to 1.24), and to the one long term trial (n=25, RR 1.09 CI 0.92 to 1.29).

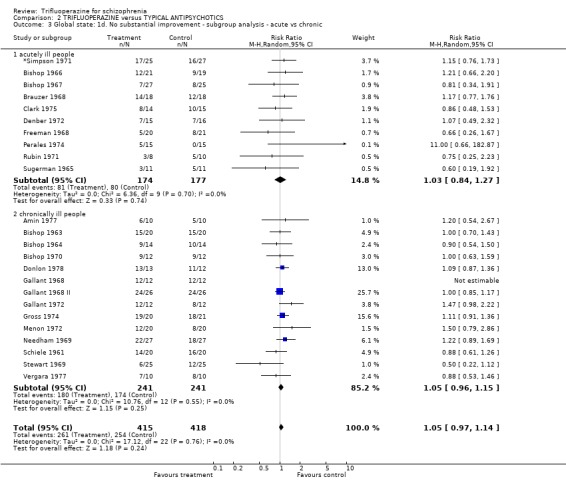

Acutely ill people responded similarly (n=351, 10 RCTs, RR 1.03 CI 0.84 to 1.27) to those with a more chronic illness (n=482, 13 RCTs, RR 1.06 CI 0.97 to 1.15). Involving people with mixed diagnoses, such as those with affective disorders, did not effect the outcome of 'no substantial improvement' (n=115, 4 RCTs RR 1.11 CI 0.8 to 1.53).

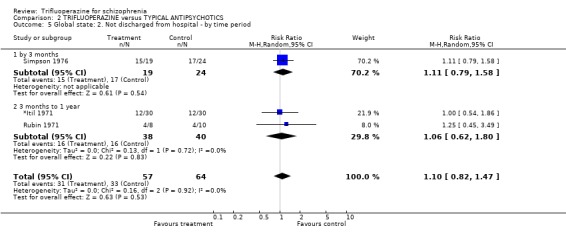

Three studies, dating from the 1970's, do not suggest that trifluoperazine has any clear advantage over other drugs for the outcome of discharge from hospital (n=121, RR 1.10 CI 0.82 to 1.47). In these trials about 40% of participants were still in hospital by one year follow up.

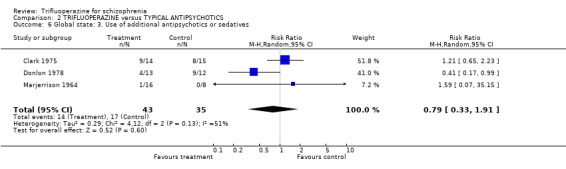

Trifluoperazine was no better than other drugs in avoiding the need for additional sedation (n=78, 3 RCTs, RR 0.79 CI 0.33 to 1.91).

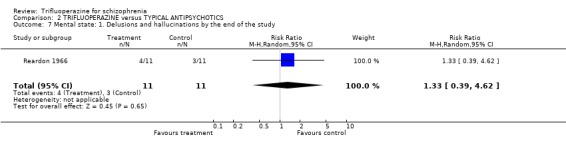

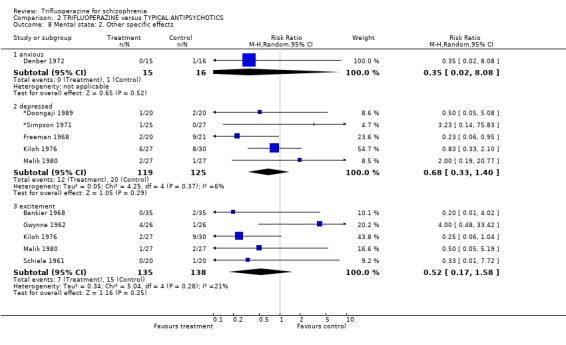

3.2 Mental state One small study (Reardon 1966) specifically reported whether hallucinations and delusions were present in participants. Most people in both the trifluoperazine and chlorpromazine group did not complain of these key psychotic symptoms (n=22, RR delusions or hallucinations 1.33 CI 0.39 to 4.62). Several other less specific aspects of mental state were reported. Compared with other older generation drugs, trifluoperazine was not clearly better in reducing anxiety, depression or excitement.

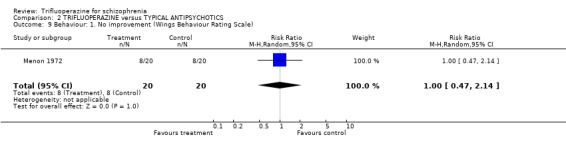

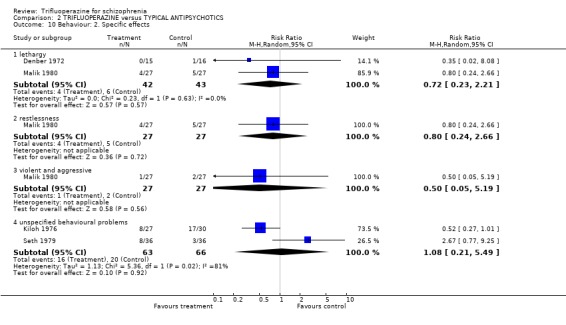

3.3 Behaviour One study reported general effects on behaviour (Menon 1972, n=40). Compared with trifluperidol, trifluoperazine was not clearly advantageous (RR no behavioural improvement 1.00 CI 0.47 to 2.14). Similar findings were reported for specific aspects of behaviour such as lethargy and aggression.

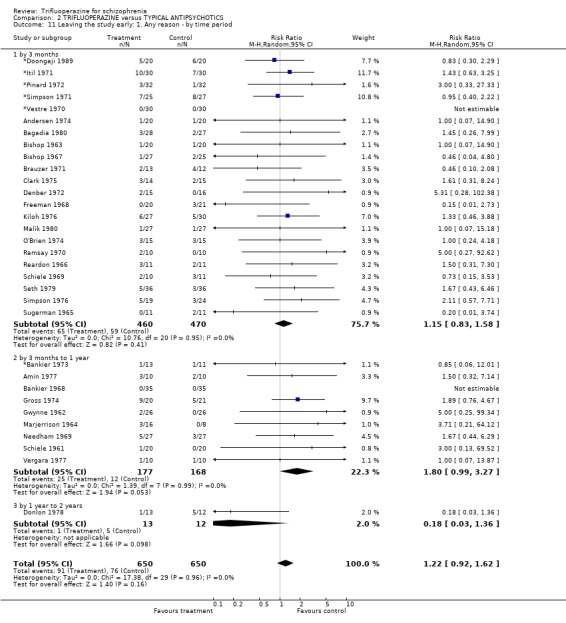

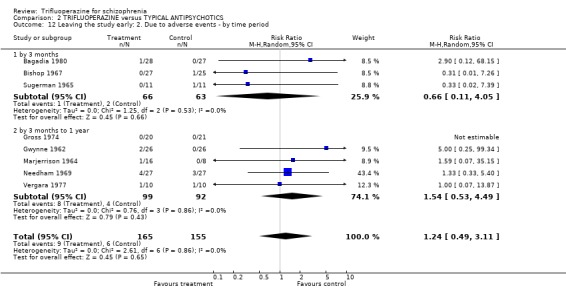

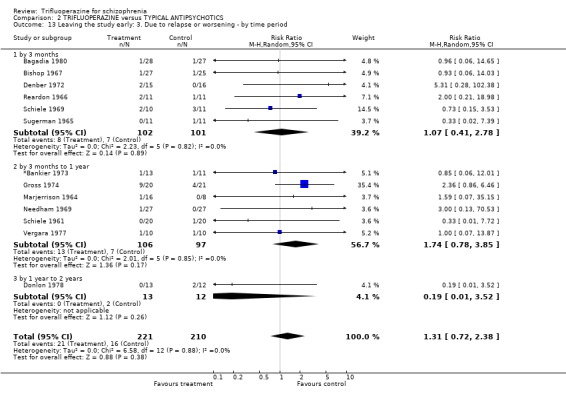

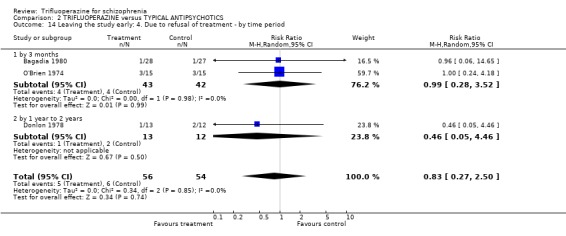

3.4 Leaving the study early Twenty‐two short‐term studies (n=930) found no clear differences between trifluoperazine and other typical antipsychotics for the outcome 'leaving for any reason' (RR 1.15 CI 0.83 to 1.58). This held true for the nine medium term studies (n=345, RR 1.8 CI 0.99 to 3.27) and the one long term trial (Donlon 1978, n=25, RR 0.18 CI 0.03 to 1.36). For the more specific outcome of leaving due to adverse effects, trifluoperazine was no more toxic than other older generation drugs, with very few people leaving for this reason (n=320, 8 RCTs, RR leaving due to adverse effects 1.24 CI 0.49 to 3.11). Leaving due to relapse was similar (n=431, 13 RCTs, RR leaving due to relapse 1.31 CI 0.72 to 2.38) as was leaving due to treatment refusal (n=110, 3 RCTs, RR leaving due to treatment refusal 0.83 CI 0.27 to 2.50).

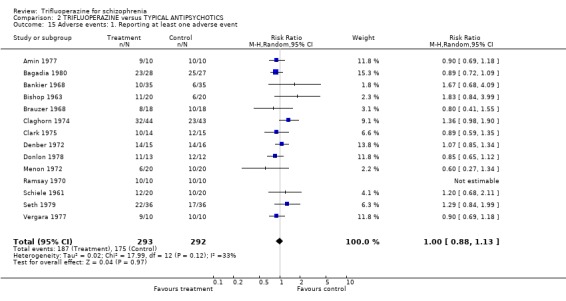

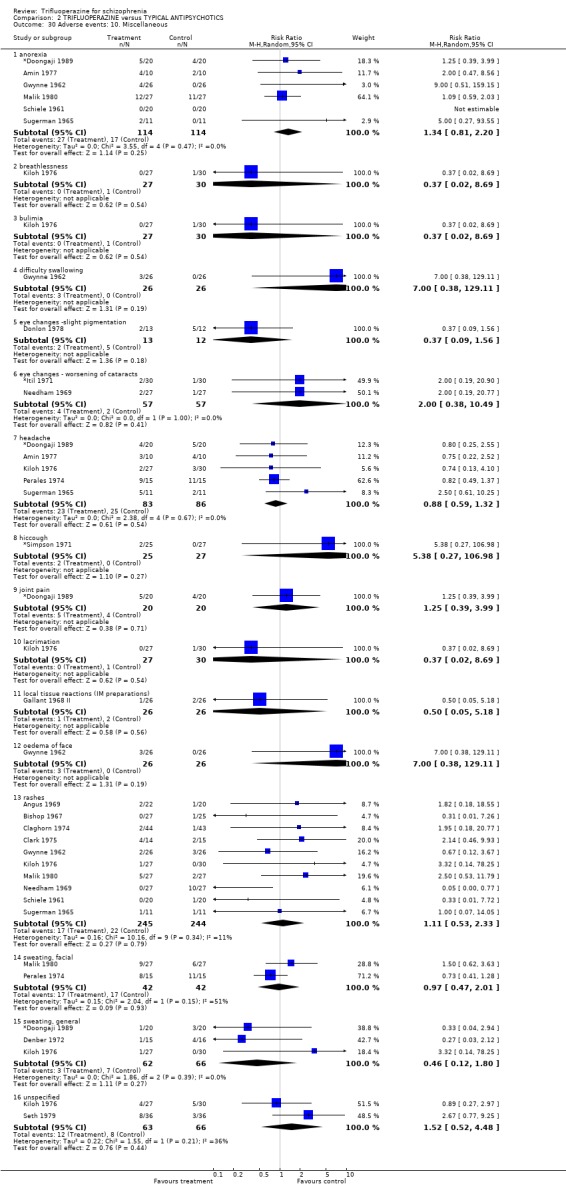

3.5 Adverse events A huge number of adverse events were listed in many different ways. There were no statistically differences between trifluoperazine and other drugs for all comparisons. Almost identical numbers of people reported at least one adverse event (˜60%) in each group (n=585, 14 RCTs, RR 0.99 CI 0.87 to 1.13).

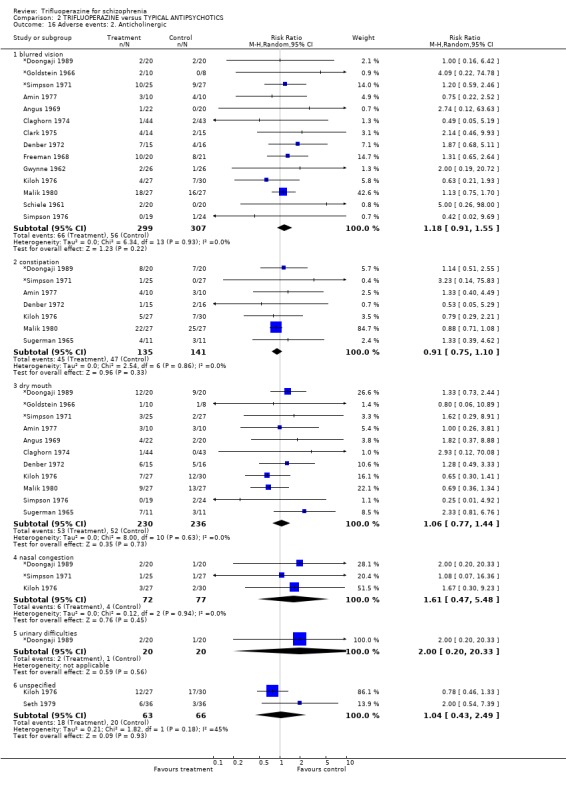

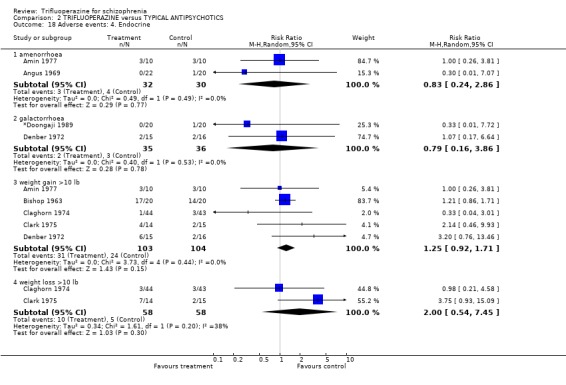

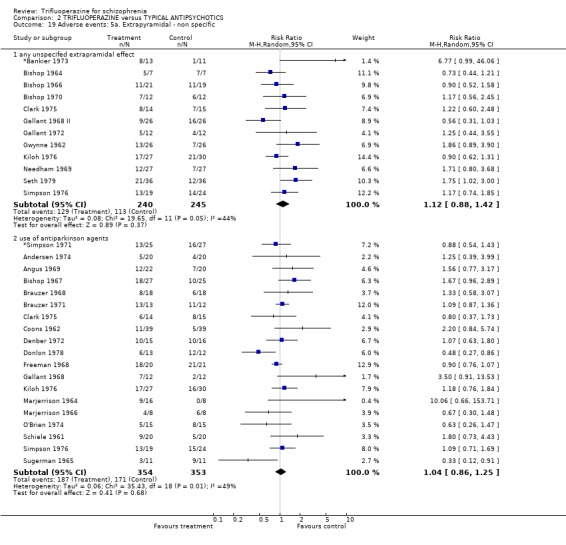

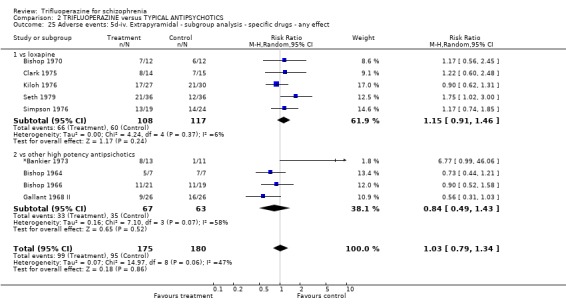

We will not reiterate all adverse effects here but just highlight some of the most noteworthy. Trifluoperazine did not cause more blurred vision than other first generation drugs (n=606, 14 RCTs, RR 1.18 CI 0.91 to 1.55). It did tend to encourage considerable weight gain, but not quite to the conventional level of statistical significance (n=207, 5 RCTs, RR >10lb weight gain 1.25 CI 0.92 to 1.71). Data with a moderate degree of inconsistency (I2 46%) did not suggest that trifluoperazine causes more unspecified movement disorders than other older generation drugs (n=485, 12 RCTs, RR 1.11 CI 0.87 to 1.43). Similarly heterogeneous data (I2 56%) did not suggest that using trifluoperazine results in more need for anticholinergic drugs than typical antipsychotics (n=707, 19 RCTs, RR 1.04 CI 0.87 to 1.24). Trifluoperazine does not seem to cause any more akathisia (n=719, 18 RCTs, RR 0.91 CI 0.70 to 1.17), dystonia (n=520, 13 RCTs, RR 1.09 CI 0.72 to 1.65) or tremor (n=612, 13 RCTs, RR 0.92 CI 0.75 to 1.12) than other old antipsychotics.

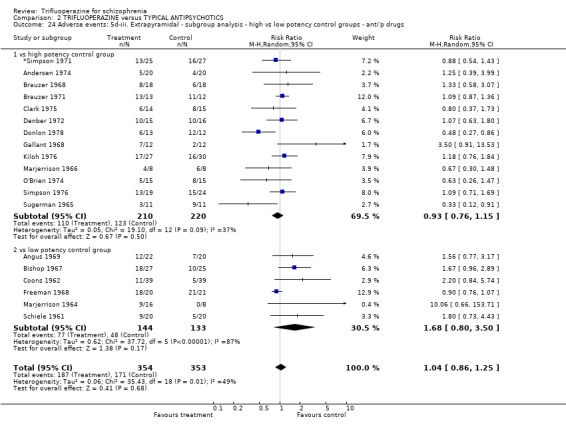

We carried out subgroup analyses in some comparisons where heterogeneity was detected. Drugs used in the control group were pooled according their potency for blocking dopamine receptors. Trifluoperazine was more likely to cause extrapyramidal adverse effects overall when compared to the low potency group (n=130, 3 RCTs, RR 1.66 CI 1.03 to 2.67, NNH 6 CI 3 to 121) and there was no difference in the high potency group (n=355, 9 RCTs, RR 1.02 CI 0.78 to 1.34), but heterogeneity remained for this subgroup (p=0.047, I2 46%). The same pattern was apparent for the high versus low potency comparison sub‐groups for the outcome of rigidity and use of antiparkinsonian drugs. Finally for this sub‐group analysis, data from the high potency control group was pooled excluding loxapine because of its different extrapyramidal profile (Fenton 2002) but this made little difference (n=225, 5 RCTs, RR extrapyramidal effects 1.15 CI 0.91 to 1.46).

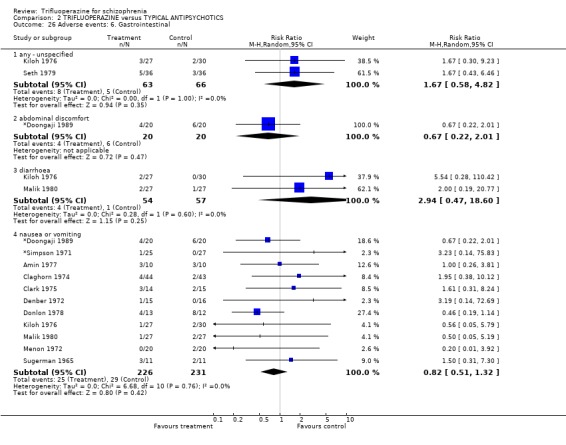

Trifluoperazine did not cause more nausea (n=457, 11 RCTs, RR 0.82 CI 0.51 to 1.32), or drowsiness (n=816, 20 RCTs, RR 0.89 CI 0.72 to 1.10) than the comparison drugs

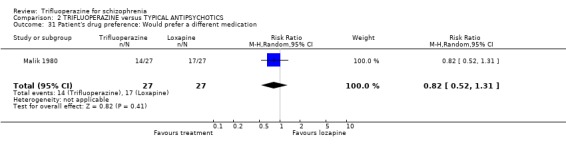

3.6 Patient's preference One small study (Malik 1980, n=54) asked patients if they preferred one medication over the other. 50‐60% in each group did express a preference for the other medication.

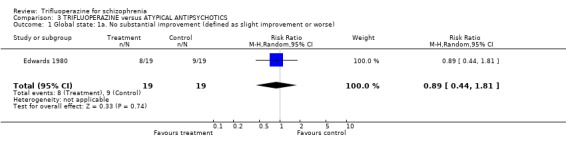

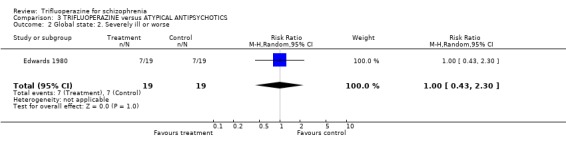

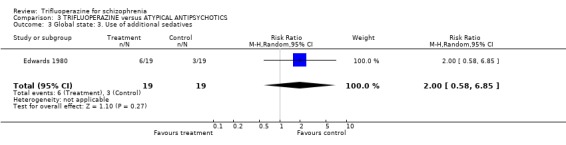

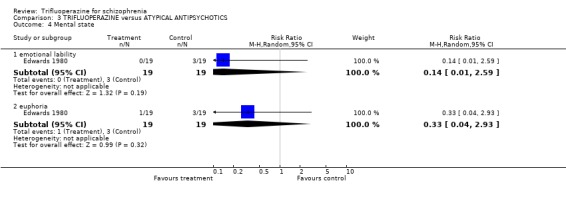

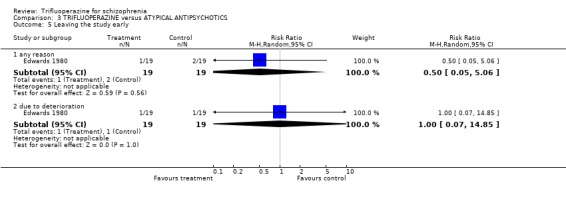

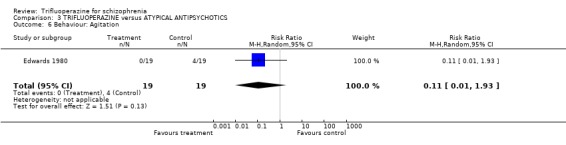

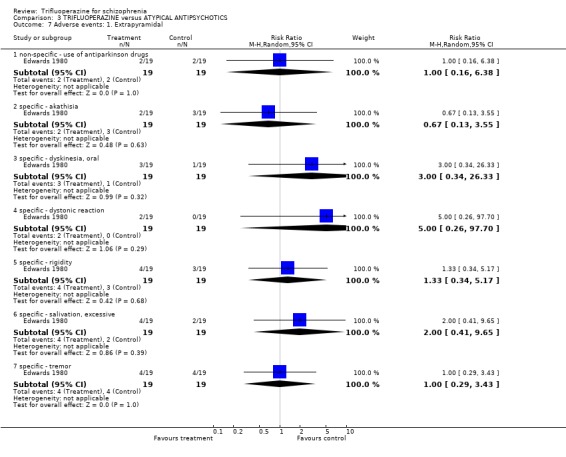

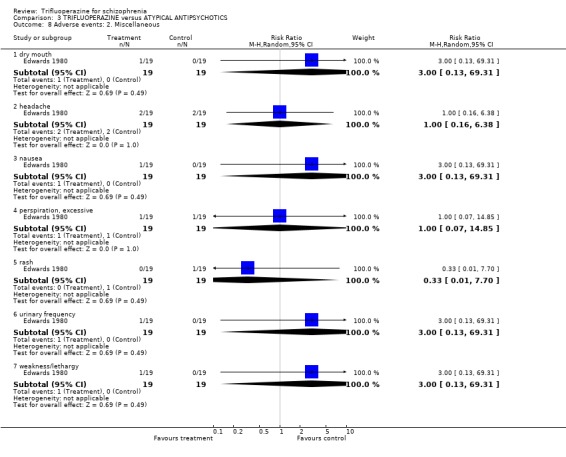

4. COMPARISON 3. TRIFLUOPERAZINE versus ATYPICAL ANTIPSYCHOTIC Only one study compared trifluoperazine with atypical antipsychotics (sulpiride) in a six‐week trial Edwards 1980 (n=38).

4.1 Global state Raters using the Clinical Global Impression scale, found no difference between the drugs in terms of global state (RR no substantial improvement 0.89 CI 0.44 to 1.81). This also applied to the outcomes of 'severely ill or worse' (RR 1.00 CI 0.43 to 2.3) and use of additional sedatives (RR 2.00 CI 0.58 to 6.85).

4.2 Mental state The small study did not find any effects of trifluoperazine on emotional state (RR lability 0.14 CI 0.01 to 2.59, RR euphoria 0.33 CI 0.04 to 2.93).

4.3 Leaving the study early Very few people left the study. One patient left each group because of worsening symptoms and another person allocated to sulpiride left the hospital (differences not significant).

4.4 Behaviour Less people given trifluoperazine were agitated compared with those in the sulpiride group (0 vs 4) but this was not statistically significant as confidence intervals were wide (RR 0.11 CI 0.01 to 1.93).

4.5 Adverse events We have roughly grouped adverse events into movement disorders and others. Edwards 1980 involved only 38 people so any statistically significant differences would be surprising. None were found, although in keeping with the findings from the trifluoperazine versus placebo comparison it seems that the older drug is more prone to cause problems with movement.

5. Publication bias We used funnel plots to investigate the possibility of publication bias (see Methods). No asymmetry was detected but many of the outcomes had a small number of trials which limits the value of the plot. Such plots are not powerful investigative tools and are further weakened when there is little variation in study size (Egger 1997). 6. Statistical model for measuring effect The findings noted above were not changed by using odds ratios or by using a fixed effects model for relative risk.

7. Sensitivity analyses We had hoped to undertake a sensitivity analysis for intention‐to‐treat analyses versus completer‐only analyses when heterogeneity was present. This is not complete and will be presented in the updates of this review.

Discussion

1. Applicability The 50 included studies involved many people who would be recognisable in everyday medical practice. Only two studies (Bagadia 1980, Malik 1980) focused on adolescents and none on childhood or old age. These trials presented similar results to those including other scopes of participants. In most of the studies the diagnosis was clinical and only a few operational criteria were used. People with schizophrenia who also had any kind of comorbidity such as alcoholism or kidney insufficiency were, however, frequently excluded in original studies and most studies were undertaken in hospital. Applying findings to people with additional health problems and in community settings could be problematic. Overall the daily doses of trifluoperazine were probably a little higher than would be seen in everyday practice (mean 28mg/day, SD 20) but do fit with American Psychiatric Association recommendations (APA 1997).

2. Limitations and strengths The main limitation of this review is that it includes a large number of small studies from many years ago. Valuable additional information could not be obtained as it proved impossible to contact many authors. We were unable to carry out an intention to treat analysis in some studies because the data on leaving the study early were not provided or were not fully or not clearly reported. Despite the fact that most of the included trials predate the CONSORT statement (Begg 1996, Moher 2001) which encourages high standards of trial reporting, twelve trials did receive a quality rating of 'A' (good) and all remaining studies were rated 'B' (medium). This review is the most current and comprehensive synthesis of these data for a widely used antipsychotic.

3. COMPARISON 1. TRIFLUOPERAZINE versus PLACEBO With 1162 people involved in this comparison, these data must represent one of the most powerful placebo comparisons in the whole of antipsychotic research.

3.1 Global state These old placebo‐controlled studies could probably not be repeated now. Although they are dogged with inconsistency in terms of the choice of measures used for similar outcomes, their results do indicate that the number of people needed to be given trifluoperazine in order for one person to improve to an important extent in the medium term is about six. In this respect trifluoperazine is similar to other older generation antipsychotic drugs (Joy 2001, Thornley 2001).

Most of the included studies were undertaken in hospital and were carried out at a time when community care was less prevalent. However, in health systems where hospital care still dominates, it may be relevant that the use of trifluoperazine, at any dose, did not make clear differences in the rate of discharge (though it should be noted that 56% of patients in the study from which these findings are derived had been in hospital for more than ten years). Oddly, being allocated to trifluoperazine did not decrease the risk of needing additional antipsychotics/sedatives. Perhaps this was because the populations in the two studies (total n=77) were not very disturbed or that placebo is also calming.

3.2 Mental state In such a large review, with thousands of patients included, only a single small study (n=23, Reardon 1966) directly reported mental state outcomes. Even within a study of such low power, trifluoperazine did seem to be effective and delusions and hallucinations were decreased (NNT 3 CI 5 to 100). Ideally, of course, this finding should be replicated in order to increase the confidence in the result.

3.3 Behaviour Again, as for mental state outcomes, too few studies with too few participants reported on this for any firm conclusions to be taken from the data. Menon 1972 (n=40) favoured trifluoperazine but Gwynne 1962 (n=52) found no clear differences between trifluoperazine and placebo.

3.4 Leaving the study early Considerably fewer people left these studies early than is common in modern studies where attrition of 40‐50% is common (Duggan 2002, Srisurapanont 2002). This could well be due to the different research climate of three decades ago rather than some advantageous aspect of study design. Nevertheless, the latter is also possible and it could be that modern researchers have lost skills or been so constrained by regulations that design has suffered and so have those likely to benefit from the research. In seven studies (total n=280) trifluoperazine was as acceptable as placebo. It can be concluded that in the climate in which these studies were undertaken, adverse effects were not an obstacle to compliance with study protocol. 3.5 Adverse events It is difficult to interpret some of the adverse effect data. Often a single study reported on an effect that was attributed to trifluoperazine and reporting biases could well be in operation. However, the more consistently reported findings do fit with clinical impression. Trifluoperazine may well cause more extrapyramidal events than placebo (n=70, 2 RCTs, NN to cause any moment disorder 4 CI 2 to 23) and more people in the trifluoperazine group used antiparkinson drugs to alleviate movement disorders (n=195, 4 RCTs, NNH 4 CI 2 to 9). It is likely that trifluoperazine may be sedating (n=119, 3 RCTs, NNH 4 CI 2 to 18) and cause anticholinergic effects (n=119, 3 RCTs, RR blurred vision 1.72 CI 0.47 to 6.26).

4. TRIFLUOPERAZINE versus TYPICAL ANTIPSYCHOTIC This comparison includes over 2000 people (49 RCTs) and so is one of the largest in the evaluation of the care of people with schizophrenia.

4.1 Global state Analyses of various measures of global state consistently failed to find clear differences between trifluoperazine and other typical antipsychotics (n=1016, 27 RCTs, RR 1.06 CI 0.98 to 1.14) and splitting the data by chronic illness versus non‐chronic, mixed diagnoses versus only people with 'pure' schizophrenia did not materially change the results. Trifluoperazine is as effective as other older generation drugs but there are no data to support its reputed 'activating effects' at low doses.

4.2 Mental state Considering the amount of data for other outcomes, it is surprising that so few have been collected on direct mental state symptoms such as delusions and hallucinations. Reardon 1966 (n=22) did record mental state outcomes but the results are too imprecise for conclusions to be drawn. Even after over 40 years of research based on randomised studies, clinicians and recipients of care have to continue to be unsure of the direct effects on delusions and hallucinations of trifluoperazine compared with other similar drugs.

4.3 Behaviour Behavioural improvement was also a rare outcome (Menon 1972, n=40) so results are imprecise and not clearly different from those of trifluperidol.

4.4 Leaving the study early Taking trifluoperazine is as acceptable as other typical antipsychotics for people with schizophrenia (14% attrition vs 11%) and, because of the relatively large numbers of people involved, we can be fairly certain of these results (short term n=930, medium term n=345). When data were reported with reasons for attrition specified, once more trifluoperazine is no different in terms of leaving the study because of adverse effects, relapse or due to due to treatment refusal. Again, because the numbers of people in these outcomes is relatively large we can be confident of the findings.

4.5 Adverse events Trifluoperazine does cause some kind of adverse effect in about 60% of people, but, according to the data from 14 trials (n=585) so do all other drugs of comparison. There was no difference between the typical antipsychotics and trifluoperazine for a whole series of adverse outcomes for which reasonable amounts of data were available (blurred vision n=606, weight gain n=207, unspecified movement disorders n=485, need for anticholinergic drugs n=707, akathisia n=719, dystonia n=520, or tremor n=612). Use of trifluoperazine carries with it a burden of adverse effects, but no more so than other similar drugs.

The sub‐group analyses must be viewed with a degree of caution as all results are heterogeneous, but the findings do coincide with clinical impression. Trifluoperazine is more likely to cause extrapyramidal adverse effects, the need for additional anticholinergic drugs, and rigidity when compared to the low potency drugs such a chlorpromazine (n˜130, 3 RCTs). This difference disappeared in comparisons with only high potency drugs such as haloperidol (n˜355, 9 RCTs). It is a pity that more studies did not ask patients if they preferred a different medication. With the above results it would be expected that people with schizophrenia would prefer the low potency drugs. Only Malik 1980 (n=54) asked patients if they preferred trifluoperazine to loxapine, an unusual low potency drug. There was no clear preference but with such small numbers the confidence in the final result is limited.

5. TRIFLUOPERAZINE versus SULPIRIDE (ATYPICAL DRUGS) Only one study compared trifluoperazine with an atypical antipsychotic (Edwards 1980, n=38, duration six weeks).

5.1 Global state, mental state, leaving the study early, and adverse effects The precision of all findings is poor as numbers are small but, in terms of measures of global state, mental state, study attrition, and adverse effects trifluoperazine seems little different to sulpiride.

This seems a little implausible and the equivocal findings are probably due to imprecision in the reporting of results. It would be interesting to compare these findings with those of other atypical studies where benchmark drugs such as clozapine have been used, particularly because there is some controversy as to whether sulpiride is really an atypical drug (Soares 2002),

6. Publication bias Even for the outcomes which many studies reported on, funnel plot analyses are limited in power, but it is heartening that no suggestion of small study‐biases were found. Perhaps, as trifluoperazine is an old drug in which there is little current commercial interest, we have managed to identify all relevant trials.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

1. For people with schizophrenia Trifluoperazine is an antipsychotic which is as effective as other commonly used typical drugs for treating schizophrenia and, in common with the other drugs, about 60% of people do experience an adverse effect. Whether to use trifluoperazine or another typical drug may, therefore, be a matter of personal preference, and there is some indication that trifluoperazine may cause more adverse effects than drugs such as chlorpromazine.

2. For clinicians Although there are shortcomings and gaps in the data, there appears to be enough overall consistency over different outcomes and time scales to confirm that trifluoperazine is an antipsychotic of similar efficacy to other commonly used antipsychotics, such as chlorpromazine. The adverse effect profile of trifluoperazine seems similar to that of typical drugs overall, but, in common with haloperidol, it may have a higher level of extrapyramidal adverse events. The common claim that trifluoperazine is a particularly useful in the treatment of withdrawal patients is not based on trial derived evidence.

3. For managers, funders, decision makers Trifluoperazine is inexpensive and is as effective as other typical antipsychotics. It might be an alternative when newer and more expensive antipsychotics are not readily available.

Implications for research.

1. General All studies considerably preceded the CONSORT statement (Begg 1996, Moher 2001), so the quality of data reporting might be expected to be lower than at present, although some studies were very clearly presented. If data from past studies is still available, we would be most interested in hearing from the authors of trials. Future studies should rigorously apply the standards of reporting as outlined in CONSORT and also make all data freely available. Continuous data were particularly poorly reported and authors should present raw data rather than graphical format.

2. Specific Trifluoperazine does seem comparable to other typical antipsychotics in terms of efficacy but most existing randomised studies are of short‐term duration and were undertaken in hospital settings. Given the clinical dilemma as to whether to use trifluoperazine or, perhaps a drug such as chlorpromazine, there is still a need for more well designed, conducted and reported randomised studies of considerable duration undertaken in real world circumstances.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 14 April 2010 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2002 Review first published: Issue 1, 2004

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 15 February 2010 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 31 October 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Acknowledgements

LOM would like to thank Clive Adams, Nancy Owens, Mark Fenton, Gillian Rizzello, Shazia Akhtar (from the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group, UK) for their administrative help and support.

The reviewers sent many letters to authors, asking for extra information. Dr George Simpson (University of Southern California), Dr Charles O'Brien (University of Pennsylvania, School of Medicine), Dr Maryanne O'Donnell (in memoriam of Dr Leslie Kiloh; Prince of Wales Hospital, UK) and Dr Guy Edwards (Royal South Hants Hospital, UK) were kind enough to respond, for which we are very grateful.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. TRIFLUOPERAZINE versus PLACEBO.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Global state: 1a. No substantial improvement (defined as slight improvement or worse) ‐ by time period | 6 | 415 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.79 [0.66, 0.94] |

| 1.1 short term (0‐3 months) | 3 | 95 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.63 [0.50, 0.79] |

| 1.2 medium term (+3 months‐1 year) | 3 | 320 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.85, 1.00] |

| 2 Global state: 1b. No substantial improvement (short term) ‐ by rater's role | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 doctor rated | 1 | 27 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.62 [0.38, 1.00] |

| 2.2 nurse rated | 1 | 27 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.67, 1.11] |

| 3 Global state: 1c. No substantial improvement ‐ by dose of trifluoperazine | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 low dose (15mg/day) | 1 | 240 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.88, 0.99] |

| 3.2 high dose (80mg/day) | 1 | 240 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.89, 0.99] |

| 4 Global state: 2. Not discharged from hospital ‐ by dose of trifluoperazine | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 low dose (15mg/day) | 1 | 240 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.96, 1.01] |

| 4.2 high dose (80mg/day) | 1 | 240 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.96, 1.01] |

| 5 Global state: 3. Use of additional antipsychotics or sedatives | 2 | 77 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.18, 6.31] |

| 6 Mental state: Delusions and hallucinations by the end of the study | 1 | 23 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.44 [0.19, 0.99] |

| 7 Behaviour: 1. No improvement (Wings Behaviour Rating Scale) ‐ by >8 weeks ‐ 6 months | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.41 [0.25, 0.70] |

| 8 Behaviour: 2. Agitation | 1 | 52 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.28, 3.58] |

| 9 Leaving the study early | 7 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 9.1 any reason | 7 | 280 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.59, 1.48] |

| 9.2 due to adverse events | 3 | 142 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.12 [0.24, 5.11] |

| 9.3 due to relapse or worsening | 5 | 205 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.50, 1.62] |

| 10 Adverse events: 1. At least one adverse effect | 2 | 67 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.40 [0.90, 2.18] |

| 11 Adverse events: 2. Cardiovascular | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 11.1 ECG abnormalities ‐ minor | 1 | 27 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.86 [0.58, 5.94] |

| 11.2 hypertension | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.0 [0.20, 20.33] |

| 12 Adverse events: 3. Extrapyramidal | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 12.1 non‐specific ‐ any movement disorder | 2 | 79 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.27 [1.19, 4.33] |

| 12.2 non‐specific ‐ antiparkinson drugs needed | 4 | 195 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 5.06 [2.49, 10.27] |

| 12.3 specific ‐ akathisia (motor restlessness) | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 3.00 [0.13, 69.52] |

| 12.4 specific ‐ dyskinesia | 1 | 27 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 3.71 [0.47, 29.06] |

| 12.5 specific ‐ oculogyric crisis | 1 | 27 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 3.71 [0.47, 29.06] |

| 12.6 specific ‐ rigidity | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 9.00 [1.25, 64.59] |

| 12.7 specific ‐ tremors | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.01, 7.72] |

| 13 Adverse events: 4. Haematological | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 13.1 eosinophilia >5% | 1 | 27 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.86 [0.41, 8.49] |

| 13.2 leukocytosis | 1 | 27 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.55 [0.46, 5.22] |

| 13.3 urea nitrogen increase | 1 | 27 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.39 [0.28, 7.05] |

| 14 Adverse events: 5. Neurological | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 14.1 convulsions | 1 | 52 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.5 [0.10, 2.50] |

| 14.2 faintness | 1 | 52 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.12, 3.67] |

| 14.3 urinary incontinence | 1 | 52 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.22, 4.50] |

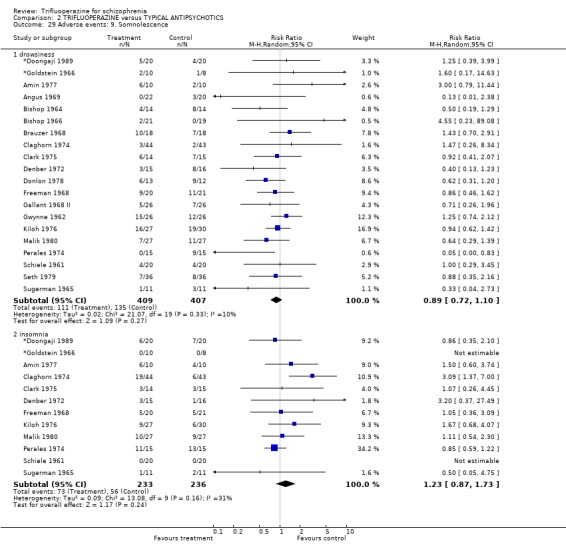

| 15 Adverse events: 6. Somnolesence | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 15.1 drowsiness | 3 | 119 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.94 [1.42, 6.10] |

| 15.2 insomnia | 2 | 67 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.07, 12.05] |

| 16 Adverse events: 7. Weight | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 16.1 gain >10 lb | 1 | 27 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.24 [0.34, 4.51] |

| 16.2 loss >10 lb | 1 | 27 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.17 [0.71, 6.66] |

| 17 Adverse events: 8. Miscellaneous | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 17.1 anorexia | 1 | 52 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.8 [0.24, 2.65] |

| 17.2 blurred vision | 3 | 119 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.72 [0.47, 6.26] |

| 17.3 nausea | 1 | 27 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.39 [0.28, 7.05] |

| 17.4 oedema ‐ face | 1 | 52 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.22, 4.50] |

| 17.5 rashes | 3 | 119 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.30, 4.01] |

| 17.6 swallowing ‐ difficulties | 1 | 52 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.22, 4.50] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TRIFLUOPERAZINE versus PLACEBO, Outcome 1 Global state: 1a. No substantial improvement (defined as slight improvement or worse) ‐ by time period.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TRIFLUOPERAZINE versus PLACEBO, Outcome 2 Global state: 1b. No substantial improvement (short term) ‐ by rater's role.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TRIFLUOPERAZINE versus PLACEBO, Outcome 3 Global state: 1c. No substantial improvement ‐ by dose of trifluoperazine.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TRIFLUOPERAZINE versus PLACEBO, Outcome 4 Global state: 2. Not discharged from hospital ‐ by dose of trifluoperazine.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TRIFLUOPERAZINE versus PLACEBO, Outcome 5 Global state: 3. Use of additional antipsychotics or sedatives.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TRIFLUOPERAZINE versus PLACEBO, Outcome 6 Mental state: Delusions and hallucinations by the end of the study.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TRIFLUOPERAZINE versus PLACEBO, Outcome 7 Behaviour: 1. No improvement (Wings Behaviour Rating Scale) ‐ by >8 weeks ‐ 6 months.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TRIFLUOPERAZINE versus PLACEBO, Outcome 8 Behaviour: 2. Agitation.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TRIFLUOPERAZINE versus PLACEBO, Outcome 9 Leaving the study early.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TRIFLUOPERAZINE versus PLACEBO, Outcome 10 Adverse events: 1. At least one adverse effect.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TRIFLUOPERAZINE versus PLACEBO, Outcome 11 Adverse events: 2. Cardiovascular.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TRIFLUOPERAZINE versus PLACEBO, Outcome 12 Adverse events: 3. Extrapyramidal.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TRIFLUOPERAZINE versus PLACEBO, Outcome 13 Adverse events: 4. Haematological.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TRIFLUOPERAZINE versus PLACEBO, Outcome 14 Adverse events: 5. Neurological.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TRIFLUOPERAZINE versus PLACEBO, Outcome 15 Adverse events: 6. Somnolesence.

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TRIFLUOPERAZINE versus PLACEBO, Outcome 16 Adverse events: 7. Weight.

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TRIFLUOPERAZINE versus PLACEBO, Outcome 17 Adverse events: 8. Miscellaneous.

Comparison 2. TRIFLUOPERAZINE versus TYPICAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Global state: 1a. No substantial improvement (defined as slight improvement or worse) ‐ by time period | 28 | 1016 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.98, 1.14] |

| 1.1 by 3 months | 22 | 816 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.94, 1.15] |

| 1.2 3 months to 1 year | 5 | 175 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.93, 1.24] |

| 1.3 1 year to 2 years | 1 | 25 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.87, 1.36] |

| 2 Global state: 1b. No substantial improvement (short term) ‐ by rater's role | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 doctor rated | 1 | 29 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.48, 1.53] |

| 2.2 nurse rated | 1 | 29 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.74, 1.32] |

| 2.3 patent rated | 3 | 131 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.54, 1.32] |

| 3 Global state: 1d. No substantial improvement ‐ subgroup analysis ‐ acute vs chronic | 24 | 833 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.97, 1.14] |

| 3.1 acutely ill people | 10 | 351 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.84, 1.27] |

| 3.2 chronically ill people | 14 | 482 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.96, 1.15] |

| 4 Global state: 1e. No substantial improvement ‐ subgroup analysis ‐ mixed diagnoses vs schizophrenia only | 21 | 792 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.91, 1.13] |

| 4.1 mixed diagnoses ‐ short term studies only | 4 | 115 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.80, 1.53] |

| 4.2 schizophrenia only ‐ short term studies | 17 | 677 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.90, 1.12] |

| 5 Global state: 2. Not discharged from hospital ‐ by time period | 3 | 121 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.82, 1.47] |

| 5.1 by 3 months | 1 | 43 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.79, 1.58] |

| 5.2 3 months to 1 year | 2 | 78 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.62, 1.80] |

| 6 Global state: 3. Use of additional antipsychotics or sedatives | 3 | 78 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.79 [0.33, 1.91] |

| 7 Mental state: 1. Delusions and hallucinations by the end of the study | 1 | 22 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.33 [0.39, 4.62] |

| 8 Mental state: 2. Other specific effects | 9 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 8.1 anxious | 1 | 31 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.35 [0.02, 8.08] |

| 8.2 depressed | 5 | 244 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.33, 1.40] |

| 8.3 excitement | 5 | 273 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.52 [0.17, 1.58] |

| 9 Behaviour: 1. No improvement (Wings Behaviour Rating Scale) | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.47, 2.14] |

| 10 Behaviour: 2. Specific effects | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 10.1 lethargy | 2 | 85 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.23, 2.21] |

| 10.2 restlessness | 1 | 54 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.8 [0.24, 2.66] |

| 10.3 violent and aggressive | 1 | 54 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.5 [0.05, 5.19] |

| 10.4 unspecified behavioural problems | 2 | 129 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.21, 5.49] |

| 11 Leaving the study early: 1. Any reason ‐ by time period | 32 | 1300 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.22 [0.92, 1.62] |

| 11.1 by 3 months | 22 | 930 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.15 [0.83, 1.58] |

| 11.2 by 3 months to 1 year | 9 | 345 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.80 [0.99, 3.27] |

| 11.3 by 1 year to 2 years | 1 | 25 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.18 [0.03, 1.36] |

| 12 Leaving the study early: 2. Due to adverse events ‐ by time period | 8 | 320 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.24 [0.49, 3.11] |

| 12.1 by 3 months | 3 | 129 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.11, 4.05] |

| 12.2 by 3 months to 1 year | 5 | 191 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.54 [0.53, 4.49] |

| 13 Leaving the study early: 3. Due to relapse or worsening ‐ by time period | 13 | 431 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.31 [0.72, 2.38] |

| 13.1 by 3 months | 6 | 203 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.41, 2.78] |

| 13.2 by 3 months to 1 year | 6 | 203 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.74 [0.78, 3.85] |

| 13.3 by 1 year to 2 years | 1 | 25 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.19 [0.01, 3.52] |

| 14 Leaving the study early: 4. Due to refusal of treatment ‐ by time period | 3 | 110 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.27, 2.50] |

| 14.1 by 3 months | 2 | 85 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.28, 3.52] |

| 14.2 by 1 year to 2 years | 1 | 25 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.46 [0.05, 4.46] |

| 15 Adverse events: 1. Reporting at least one adverse event | 14 | 585 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.88, 1.13] |

| 16 Adverse events: 2. Anticholinergic | 16 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 16.1 blurred vision | 14 | 606 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.18 [0.91, 1.55] |

| 16.2 constipation | 7 | 276 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.75, 1.10] |

| 16.3 dry mouth | 11 | 466 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.77, 1.44] |

| 16.4 nasal congestion | 3 | 149 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.61 [0.47, 5.48] |

| 16.5 urinary difficulties | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.0 [0.20, 20.33] |

| 16.6 unspecified | 2 | 129 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.43, 2.49] |

| 17 Adverse events: 3. Cardiovascular | 11 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 17.1 any unspecified cardiovascular problem | 2 | 129 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.21 [0.54, 2.73] |

| 17.2 ECG abnormalities ‐ minor | 1 | 29 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.45, 2.55] |

| 17.3 hypertension | 2 | 111 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.26 [0.21, 7.66] |

| 17.4 hypotension | 6 | 252 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.55 [0.28, 1.10] |

| 17.5 palpitations | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.39, 2.58] |

| 17.6 syncope | 2 | 97 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.36 [0.06, 2.17] |

| 17.7 tachycardia | 1 | 57 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.44 [0.09, 2.10] |

| 18 Adverse events: 4. Endocrine | 7 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 18.1 amenorrhoea | 2 | 62 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.24, 2.86] |

| 18.2 galactorrhoea | 2 | 71 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.79 [0.16, 3.86] |

| 18.3 weight gain >10 lb | 5 | 207 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.92, 1.71] |

| 18.4 weight loss >10 lb | 2 | 116 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.00 [0.54, 7.45] |

| 19 Adverse events: 5a. Extrapyramidal ‐ non specific | 28 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 19.1 any unspecifed extrapramidal effect | 12 | 485 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.12 [0.88, 1.42] |

| 19.2 use of antiparkinson agents | 19 | 707 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.86, 1.25] |

| 20 Adverse events: 5b. Extrapyramidal ‐ specific problems | 20 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 20.1 akathisia | 18 | 719 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.70, 1.17] |

| 20.2 dyskinesia, tardive | 2 | 62 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.54 [0.71, 9.02] |

| 20.3 dystonic symptoms ‐ unspecified | 14 | 520 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.72, 1.65] |

| 20.4 facial expression abnormal | 4 | 147 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.62 [0.33, 1.16] |

| 20.5 gait, Parkinsonian | 5 | 152 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.67, 1.57] |

| 20.6 oculogyric crisis | 3 | 101 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.21 [0.52, 2.82] |

| 20.7 Parkinsonism syndrome | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 7.24 [1.00, 52.64] |

| 20.8 rigidity | 15 | 636 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.79, 1.42] |

| 20.9 salivation, increased | 7 | 283 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.64, 1.84] |

| 20.10 tremor | 14 | 612 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.75, 1.12] |

| 21 Adverse effects: 5c. Extrapyramidal ‐ average daily dose of antiparkinson agent (trihexyphenidyl) | 1 | 40 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.2 [‐2.78, ‐1.62] |

| 22 Adverse events: 5d‐i. Extrapyramidal ‐ subgroup analysis ‐ high vs low potency control groups ‐ any effect | 12 | 485 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.12 [0.88, 1.42] |

| 22.1 vs high potency control group | 9 | 355 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.79, 1.34] |

| 22.2 vs low potency control group | 3 | 130 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.66 [1.03, 2.67] |

| 23 Adverse events: 5d‐ii. Extrapyramidal ‐ subgroup analysis ‐ high vs low potency control groups ‐ rigidity | 15 | 636 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.79, 1.42] |

| 23.1 vs high potency control group | 12 | 513 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.79, 1.36] |

| 23.2 vs low potency control group | 3 | 123 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.29 [0.36, 4.60] |

| 24 Adverse events: 5d‐iii. Extrapyramidal ‐ subgroup analysis ‐ high vs low potency control groups ‐ anti'p drugs | 19 | 707 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.86, 1.25] |

| 24.1 vs high potency control group | 13 | 430 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.76, 1.15] |

| 24.2 vs low potency control group | 6 | 277 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.68 [0.80, 3.50] |

| 25 Adverse events: 5d‐iv. Extrapyramidal ‐ subgroup analysis ‐ specific drugs ‐ any effect | 9 | 355 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.79, 1.34] |

| 25.1 vs loxapine | 5 | 225 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.15 [0.91, 1.46] |

| 25.2 vs other high potency antipsichotics | 4 | 130 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.49, 1.43] |

| 26 Adverse events: 6. Gastrointestinal | 12 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 26.1 any ‐ unspecified | 2 | 129 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.67 [0.58, 4.82] |

| 26.2 abdominal discomfort | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.22, 2.01] |

| 26.3 diarrhoea | 2 | 111 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.94 [0.47, 18.60] |

| 26.4 nausea or vomiting | 11 | 457 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.51, 1.32] |

| 27 Adverse events: 7. Haematological | 7 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 27.1 any haematological abnormality ‐ unpsecified | 1 | 87 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.95 [0.52, 7.32] |

| 27.2 blood cell count ‐ eosinophilia >5% | 1 | 29 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.43 [0.39, 5.28] |

| 27.3 blood cell count ‐ leukocytosis | 2 | 72 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.17 [0.43, 3.15] |

| 27.4 liver enzyme elevation ‐ alkaline phosphatase | 2 | 54 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.59 [0.25, 1.39] |

| 27.5 liver enzyme elevation ‐ bilirubin | 2 | 68 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.18 [0.03, 0.92] |

| 27.6 liver enzyme elevation ‐ SGOT | 4 | 169 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.17, 4.07] |

| 27.7 liver enzyme elevation ‐ SGPT | 2 | 81 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.28 [0.05, 1.62] |

| 27.8 renal function ‐ urea nitrogen elevated | 1 | 29 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.61 [0.31, 8.24] |

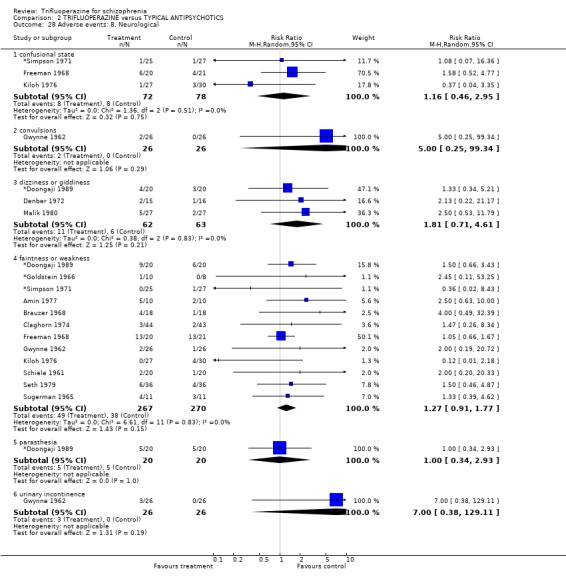

| 28 Adverse events: 8. Neurological | 14 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 28.1 confusional state | 3 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.16 [0.46, 2.95] |

| 28.2 convulsions | 1 | 52 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 5.0 [0.25, 99.34] |

| 28.3 dizziness or giddiness | 3 | 125 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.81 [0.71, 4.61] |

| 28.4 faintness or weakness | 12 | 537 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.27 [0.91, 1.77] |

| 28.5 parasthesia | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.34, 2.93] |