Abstract

Background

Psychotropic drugs are associated with sexual dysfunction. Symptoms may concern penile erection, lubrication, orgasm, libido, retrograde ejaculation, sexual arousal, or overall sexual satisfaction. These are major aspects of tolerability and can highly affect patients’ compliance.

Objectives

To determine the effects of different strategies (e.g. dose reduction, drug holidays, adjunctive medication, switching to another drug) for treatment of sexual dysfunction due to antipsychotic therapy.

Search methods

An updated search was performed in the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Trials Register (3 May 2012) and the references of all identified studies for further trials.

Selection criteria

We included all relevant randomised controlled trials involving people with schizophrenia and sexual dysfunction.

Data collection and analysis

We extracted data independently. For dichotomous data we calculated random effects risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI), for crossover trials we calculated Odds Ratios (OR) with 95% CI. For continuous data, we calculated mean differences (MD) on the basis of a random‐effects model. We analysed cross‐over trials under consideration of correlation of paired measures.

Main results

Currently this review includes four pioneering studies (total n = 138 , duration two weeks to four months), two of which are cross‐over trials. One trial reported significantly more erections sufficient for penetration when receiving sildenafil compared with when receiving placebo (n = 32, MD 3.20 95% CI 1.83 to 4.57), a greater mean duration of erections (n = 32, MD 1.18 95% CI 0.52 to 1.84) and frequency of satisfactory intercourse (n = 32, MD 2.84 95% CI 1.61 to 4.07). The second trial found no evidence for selegiline as symptomatic treatment for antipsychotic‐induced sexual dysfunction compared with placebo (n = 10, MD change on Aizenberg's sexual functioning scale ‐0.40 95% CI ‐3.95 to 3.15). No evidence was found for switching to quetiapine from risperidone to improve sexual functioning (n = 36, MD ‐2.02 95% CI ‐5.79 to 1.75). One trial reported significant improvement in sexual functioning when participants switched from risperidone or an typical antipsychotic to olanzapine (n = 54, MD ‐0.80 95% CI ‐1.55 to ‐0.05).

Authors' conclusions

We are not confident that cross‐over studies are appropriate for this participant group as they are best for conditions that are stable and for interventions with no physiological and psychological carry‐over. Sildenafil may be a useful option in the treatment of antipsychotic‐induced sexual dysfunction in men with schizophrenia, but this conclusion is based only on one small short trial. Switching to olanzapine may improve sexual functioning in men and women, but the trial assessing this was a small, open label trial. Further well designed randomised control trials that are blinded and well conducted and reported, which investigate the effects of dose reduction, drug holidays, symptomatic therapy and switching antipsychotic on sexual function in people with antipsychotic‐induced sexual dysfunction are urgently needed.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Male; Antipsychotic Agents; Antipsychotic Agents/adverse effects; Benzodiazepines; Benzodiazepines/therapeutic use; Cross‐Over Studies; Drug Substitution; Erectile Dysfunction; Erectile Dysfunction/chemically induced; Erectile Dysfunction/drug therapy; Olanzapine; Piperazines; Piperazines/therapeutic use; Purines; Purines/therapeutic use; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Selegiline; Selegiline/therapeutic use; Sexual Dysfunction, Physiological; Sexual Dysfunction, Physiological/chemically induced; Sexual Dysfunction, Physiological/drug therapy; Sildenafil Citrate; Sulfones; Sulfones/therapeutic use; Vasodilator Agents; Vasodilator Agents/therapeutic use

Plain language summary

Management of sexual problems due to antipsychotic drug therapy

Drugs commonly used to treat schizophrenia often cause sexual problems.This may affect erection, lubrication, orgasm, desire or libido, ejaculation, sexual arousal or overall sexual satisfaction. This may have serious negative consequences such as putting people off taking their medication or stopping taking drugs at an early stage. Sexual problems may limit a person’s quality of life, worsen self‐esteem and cause relationship problems.Strategies to manage these sexual problems are taking additional drugs (Viagra TM), short drug holidays when people temporarily stop antipsychotic medication, reduction of dose and switching to another antipsychotic drug. This review includes four pioneering studies with a total of 138 participants lasting between two weeks to four months, meaning all were small and quite short. Two of the studies compared the effects of drugs to treat sexual problems and two compared the effect of switching to a different antipsychotic drug (while remaining on a current antipsychotic). There is some evidence that sildenafil ((ViagraTM, RevatioTM)) may be a good treatment for men who have problems getting and maintaining an erection. It also seems to increase frequency and satisfaction of sexual intercourse. Switching to olanzapine may improve sexual functioning in men and women.

However, before confident claims can be made, much more research on strategies to deal with sexual problems should be undertaken. Sildenafil may be a useful option in the treatment of sexual problems in men with schizophrenia, but this conclusion is based only on one small, short trial. Switching to olanzapine may improve sexual functioning in men and women, but the trial assessing this was small. Further well designed trials and research, which investigate the effects of dose reduction, drug holidays, taking drugs such as Viagra TM, and switching antipsychotic medication, are much needed.

This plain language summary (PLS) was written by a consumer contributor, Ben Gray from RETHINK: Benjamin Gray, Service User and Service User Expert, Rethink Mental Illness, Email: ben.gray@rethink.org.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. ADJUNCTIVE TREATMENT ‐ SPECIFIC: SILDENAFIL versus PLACEBO for management of sexual dysfunction due to antipsychotic drug therapy.

| SILDENAFIL versus PLACEBO for management of sexual dysfunction due to antipsychotic drug therapy | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with sexual dysfunction due to antipsychotic drug therapy Settings: Outpatients Intervention: SILDENAFIL versus PLACEBO | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | SILDENAFIL versus PLACEBO | |||||

| Sexual function: Subjective assessment (number of erections) Follow‐up: 2 weeks | The mean number of erections in the intervention groups was 3.2 higher (1.83 to 4.57 higher) | 31 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | This trial only included men. | ||

| Sexual function: Objective assessment (Global efficacy questionnaire, improved erections) Follow‐up: 2 weeks | See comment | See comment | OR 11.76 (6.54 to 21.13) | 31 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | OR calculated from the log of the odds ratio.This trial only included men. |

| Leaving the study early Follow‐up: 2 weeks | 62 per 1000 | 21 per 1000 (1 to 476) | RR 0.33 (0.01 to 7.62) | 32 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | |

|

Quality of life Not reported |

See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No data were provided for this outcome. |

|

Adverse effects: Death Not reported |

See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No data were provided for this outcome. |

|

Adverse effects: Psychotic symptoms Not reported |

See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No data were provided for this outcome. |

|

Adverse effects: Extrapyramidal symptoms Not reported |

See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No data were provided for this outcome. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Only one trial provided data for this comparison. It was a very small cross‐over trial of short duration. 2 This trial only included men. 3 The 95% confidence intervals around the pooled effect estimate include both significant benefit and harm of intervention.

Summary of findings 2. ADJUNCTIVE TREATMENT ‐ NON‐SPECIFIC: SELEGILINE versus PLACEBO for management of sexual dysfunction due to antipsychotic drug therapy.

| SELEGILINE versus PLACEBO for management of sexual dysfunction due to antipsychotic drug therapy | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with sexual dysfunction due to antipsychotic drug therapy Settings: Outpatients Intervention: SELEGILINE versus PLACEBO | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | SELEGILINE versus PLACEBO | |||||

| Sexual function: Subjective assessment (Aizenburg's scale) Follow‐up: 3 weeks | The mean sexual function in the intervention groups was 0.4 lower (3.95 lower to 3.15 higher) | 0 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | |||

| Leaving the study early Follow‐up: 3 weeks | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 10 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | Only one trial provided data for this comparison. No attritions were reported in this trial. |

|

Quality of life Not reported |

See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No data were provided for this outcome. |

|

Adverse effects: Death Not reported |

See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No data were provided for this outcome. |

| Adverse effects: Psychopathology (PANSS) Follow‐up: 3 weeks | The mean psychopathology in the intervention groups was 0.50 higher (0.61 lower to 1.61 higher) | 10 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | |||

| Adverse effects: Extrapyramidal symptoms (Simpson‐Angus) Follow‐up: 3 weeks | The mean extrapyramidal symptoms in the intervention groups was 0.9 lower (3.88 lower to 2.08 higher) | 10 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | |||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Only one trial provided data for this comparison. It was a very small cross‐over trial of short duration. The risk of bias for random sequence generation, allocation concealment and blinding were unclear. 2 This trial only included men. 3 The 95% confidence intervals around the pooled effect estimate include both significant benefit and harm of intervention.

Summary of findings 3. SWITCHING ANTIPSYCHOTIC: TO QUETIAPINE versus MAINTENANCE RISPERIDONE for management of sexual dysfunction due to antipsychotic drug therapy.

| SWITCH to quetiapine versus MAINTENANCE risperidone for management of sexual dysfunction due to antipsychotic drug therapy | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with sexual dysfunction due to antipsychotic drug therapy Settings: Outpatients Intervention: SWITCH to quetiapine versus MAINTENANCE risperidone | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | SWITCH to quetiapine versus MAINTENANCE risperidone | |||||

| Sexual function: Subjective assessment (ASEX scale) Follow‐up: 6 weeks | The mean sexual function in the intervention groups was 2.02 lower (5.79 lower to 1.75 higher) | 36 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | |||

| Sexual function: Subjective assessment (prolactin levels, ng/ml) Follow‐up: 6 weeks | The mean prolactin levels (ng/ml) in the intervention groups was 13.6 lower (25.76 to 1.44 lower) | 17 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,3 | |||

| Leaving the study early Follow‐up: 6 weeks | 91 per 1000 | 200 per 1000 (41 to 976) | RR 2.2 (0.45 to 10.74) | 42 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | No attritions were reported for this study. The results are based on the number of participants with observations for the main outcome at the end of the trial. |

|

Quality of life Not reported |

See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No data were provided for this outcome. |

|

Adverse effects: Death Not reported |

See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No data were provided for this outcome. |

| Adverse effects: Psychopathology (PANSS) Follow‐up: 6 weeks | The mean psychopathology in the intervention groups was 0.6 lower (4.35 lower to 3.15 higher) | 42 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | |||

|

Adverse effects: Extrapyramidal symptoms Not reported |

See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No data were provided for this outcome. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 One trial provided data for this comparison. It was a short, small trial, and had an unclear risk of bias for random sequence generation and allocation concealment. It was also unclear is the outcome assessors were blinded. 2 The 95% confidence intervals around the pooled effect estimate include both significant benefit and harm of intervention. 3 This outcome was only reported in a sub‐sample of participants. No explanation was provided why this was done.

Summary of findings 4. SWITCHING ANTIPSYCHOTIC: TO OLANZAPINE versus MAINTENANCE RISPERIDONE/FGA for management of sexual dysfunction due to antipsychotic drug therapy.

| SWITCH to olanzapine versus MAINTENANCE risperidone/FGA for management of sexual dysfunction due to antipsychotic drug therapy | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with sexual dysfunction due to antipsychotic drug therapy Settings: Outpatients Intervention: SWITCH to olanzapine versus MAINTENANCE risperidone/FGA | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | SWITCH to olanzapine versus MAINTENANCE risperidone/FGA | |||||

| Sexual function: Subjective assessment (GISF) Follow‐up: 4 months | The mean sexual function in the intervention groups was 0.8 lower (1.55 to 0.05 lower) | 54 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | |||

| Sexual function: Objective assessment (prolactin levels, ng/ml) Follow‐up: 4 months | The mean prolactin levels (ng/ml) in the intervention groups was 30.84 lower (47.46 to 14.22 lower) | 54 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | |||

| Leaving the study early Follow‐up: 4 months | 148 per 1000 | 333 per 1000 (117 to 953) | RR 2.25 (0.79 to 6.43) | 54 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | |

|

Quality of life Not reported |

See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No data were provided for this outcome. |

|

Adverse effects: Death Not reported |

See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No data were provided for this outcome. |

| Adverse effects: Psychopathology ‐ various scales Follow‐up: 4 months | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 41 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | Psychopathology was measured on 4 scales (BPRS, PANSS, CGI‐S MMSE), none of which showed a significant difference between treatment groups. |

| Adverse effects: Extrapyramidal symptoms ‐ various scales Follow‐up: 4 months | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 41 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | Extrapyramidal symptoms were measured on 3 scales (Barnes Akathisia, Simpson‐Agnus, AIMS), none showed a significant difference between treatment groups. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Only one trial provided data for this comparison. This trial had an unclear risk of bias for random sequence generation and allocation concealment. It has a high risk of bias for blinding as it was an open label trial. 2 The 95% confidence intervals around the pooled effect estimate include both significant benefit and harm of intervention.

Background

Description of the condition

Sexual dysfunction is an important public health problem that affects the overall well‐being of many people with schizophrenia (El Kissi 2011; Laumann 1999; Nicolaou 2012). It is well established that psychotropic drugs commonly cause sexual dysfunction (El Kissi 2011; Kelly 2004; Montejo 2010; Üçok 2007; Zemishlany 2012). Symptoms may include impairments of: penile erection, lubrication, orgasm, libido, retrograde ejaculation, sexual arousal or overall sexual satisfaction. This adverse effect has been reported to occur with many classes of psychotropic medications though incidences vary in the reported literature between the different agents and countries (Kelly 2004; Malik 2007; Xiang 2011). As an example, the identical drug was reported to have an incidence of sexual dysfunction of 8% in one trial (Herman 1990) and 75% in another (Segraves 1998). Sexual dysfunction has been described to be associated with antipsychotic‐agents to a great extent (El Kissi 2011; Montejo 2010). Psychotropic‐induced sexual dysfunction may have serious negative consequences such as non‐compliance with medication or early discontinuation of pharmacotherapy (Apantaku‐Olajide 2011; Hashimoto 2012a). Moreover, sexual dysfunctions may diminish a person’s quality of life, worsen self‐esteem and cause relationship problems (Althof 2005; Laumann 1999).

Description of the intervention

Different strategies to treat psychotropic‐induced sexual dysfunction have been considered including drug holidays, dose reduction, switching to another psychotropic drug that is meant to be less likely to cause sexual dysfunction and a large number of agents for symptomatic therapy (Clayton 1998; Gitlin 1994; Kelly 2004; Nicolaou 2012).

How the intervention might work

Dose reduction means reducing the dose of the agent causing the sexual dysfunction. A special form of dose reduction is the intervention of drug holidays; this involves discontinuation of the drug two to three days before the anticipated sexual activity. After the sexual activity, the patient can either ignore the skipped medication and carry on with the usual dose or make up for all, or part of the unused medication. Agents that can be used symptomatically to reverse sexual dysfunction induced by psychotropic medication include psychostimulant agents such as PDE‐5 (phosphodiesterase type 5) inhibitors (i.e. sildenafil) and yohimbine (Clayton 1998; Kelly 2004).

Why it is important to do this review

While for many agents, such as antidepressants, the problem of sexual adverse effects has been the focus of concern for years (Clayton 2006; Williams 2006), there is little information about the effects of different strategies in treating antipsychotic‐induced sexual dysfunction

Objectives

To determine the effects of different strategies (dose reduction, drug holidays, symptomatic therapy, switching to another antipsychotic) for treatment of sexual dysfunction due to antipsychotic therapy.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All relevant randomised controlled trials. If a trial was described as 'double blind' but implied randomisation, we included such trials in a sensitivity analysis (see Sensitivity analysis). If their inclusion did not result in a substantive difference, they remained in the analyses. If their inclusion resulted in statistically significant differences, we did not add the data from these lower quality studies to the results of the better trials, but presented such data within a subcategory. We excluded quasi‐randomised studies, such as those allocating by alternate days of the week. Where people were given additional treatments, we only included data if the adjunct treatment was evenly distributed between groups and it was only the strategy for the treatment of sexual dysfunction that was randomised.

Types of participants

We included trials that involved both men and women, of any age, suffering from sexual dysfunction due to antipsychotics in any aspect of sexual performance or behaviour (e.g. penile erection, lubrication, orgasm, libido, sexual arousal or overall sexual satisfaction) as measured by criteria defined by the primary authors of the trials.

We considered the following antipsychotic drugs as potential causes of sexual dysfunction: alimemazine, amisulpride, benperidol, bromperidol, chlorprothixene, clopenthixol, clozapine, dixyrazine, flupenthixol, fluphenazine, fluspirilene, haloperidol, levomepromazine, melperone, olanzapine, perazine, perphenazine, pimozide, pipamperone, promazine, promethazine, prothipendyl, quetiapine, reserpine, risperidone, sulpiride, thioridazine, trifluperazine, trifluperidol, triflupromazine, ziprasidone, zotepine, zuclopenthixol.

Types of interventions

1. Dose reduction

Reduction of the dose of the agent causing the sexual dysfunction.

2. Drug holidays

Discontinuation of the drug two to three days before the anticipated sexual activity.

3. Adjunctive therapy

Use of additional therapy specifically targeted to improve sexual dysfunction symptoms, for example, sildenafil.

4. Switching to another antipsychotic drug

To reduce any sexual adverse effects of a specific compound or compounds.

All the above techniques could be compared with each other or placebo, no intervention (untreated control groups) or maintenance intervention.

Types of outcome measures

We grouped outcomes into short term (up to 12 weeks), medium term (13‐26 weeks) and long term (over 26 weeks) categories.

Primary outcomes

1. No clinically significant improvement of sexual dysfunction as defined by the authors, e.g. less than 50% improvement on a rating scale

Secondary outcomes

1. Improvement of sexual dysfunction

1.1 Objective assessment of improvement of sexual dysfunction by the trialists

1.1.1 Clinically significant improvement of sexual dysfunction as defined by the authors 1.1.2 Average score/change of sexual dysfunction

1.2 Subjective assessment of improvement of sexual dysfunction by the participants

1.2.1 Clinically significant improvement of sexual dysfunction as defined by the authors ‐ other than long term 1.2.2 Average score/change of sexual dysfunction

2. Leaving the study early (for any reason e.g. adverse events or inefficacy of treatment)

3. Quality of life

3.1 Improvement of quality of life ‐ as defined by each of the studies

3.2 Average score/change of quality of life

4. Adverse outcomes

4.1 Death

4.2 Other specific adverse effects e.g. worsening of psychotic symptoms

4.3 Non specific side effects

5. Economic data

5.1 Direct costs

5.2 Indirect costs

6. 'Summary of findings' table

We used the GRADE approach to interpret findings (Schünemann 2008) and used the GRADE profiler to import data from Review Manager (RevMan) to create 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables provide outcome‐specific information concerning the overall quality of evidence from each included study in the comparison, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on all outcomes we rated as important to patient‐care and decision making. We selected the following main outcomes for inclusion in the 'Summary of findings' table.

1. Sexual function

1.1 Objective assessment of sexual dysfunction as defined by each of the studies 1.2 Subjective assessment of sexual dysfunction as defined by each of the studies

2. Leaving the study early

3. Quality of life

4. Adverse effects

4.1 Death 4.2 Psychotic symptoms 4.3 Extrapyramidal symptoms

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register (May 2012)

For details of previous searches please see Appendix 1.

We updated this search. The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Trials Register (3 May 2012).

[*sexual dys* in title or abstract of REFERENCE or in health care conditions of STUDY] The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Trials Register is compiled by systematic searches of major databases, handsearches of journals and conference proceedings (see Group Module). Incoming trials are assigned to relevant existing or new review titles.

Searching other resources

1. Personal contact and pharmaceutical companies

For the update, we did not contact the first author of each included study or companies involved in the production of the principal antipsychotic.

2. Reference searching

We inspected the reference lists of all identified studies for additional studies.

Data collection and analysis

Methods used in data collection and analysis for this update are described below; for methods used in previous versions, please see Appendix 2.

Selection of studies

For this update, review authors MB and MH independently inspected citations from the new electronic search and identified relevant abstracts. The same two review authors inspected full articles of the abstracts meeting inclusion criteria and carried out the reliability check of all citations from the new electronic search.

Data extraction and management

1. Extraction

For this update, Enhance Reviews authors (KSW and NM) extracted and analysed data from included studies. We extracted data presented only in graphs and figures whenever possible. When further information was necessary, we contacted authors of studies in order to obtain missing data or for clarification.

2. Management

2.1 Forms

We extracted data onto standard, simple forms.

2.2 Scale‐derived data

We included continuous data from rating scales only if: a. the psychometric properties of the measuring instrument have been described in a peer‐reviewed journal (Marshall 2000); and b. the instrument has not been developed or modified by one of the trialists for that particular trial.

Ideally, instruments should either be i. a self‐report or ii. completed by an independent rater or relative (not the therapist). We realise that this is not often reported clearly; we have noted whether or not this is the case in Description of studies.

2.3 Endpoint versus change data

There are advantages of both endpoint and change data. Change data can remove a component of between‐person variability from the analysis. On the other hand, calculation of change needs two assessments (baseline and endpoint), which can be difficult in unstable and difficult to measure conditions such as schizophrenia. We decided primarily to use endpoint data, and only use change data if the former were not available. We would have combined endpoint and change data in the analysis had there been data to combine, as we used mean differences (MD) rather than standardised mean differences (SMD) throughout (Higgins 2011).

2.4 Skewed data

Continuous data on clinical and social outcomes are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data, we aimed to apply the following standards to all data before inclusion: a) standard deviations (SD) and means are reported in the paper or obtainable from the authors; b) when a scale starts from the finite number zero, the SD, when multiplied by two, is less than the mean (as otherwise the mean is unlikely to be an appropriate measure of the centre of the distribution (Altman 1996)); c) if a scale started from a positive value (such as the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) which can have values from 30 to 210), we modified the calculation described above to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases skew is present if 2SD>(S‐S min), where S is the mean score and S min is the minimum score. Endpoint scores on scales often have a finite start and end point and these rules can be applied. We would have entered skewed endpoint data from studies of fewer than 200 participants in additional tables rather than into an analysis. Skewed data pose less of a problem when looking at mean if the sample size is large; we would have entered skewed endpoint data from large trials into syntheses.

When continuous data are presented on a scale that includes a possibility of negative values (such as change data), it is difficult to tell whether data are skewed or not based solely on the mean and the SD. In these cases, we entered change data into the syntheses.

2.5 Common measure

To facilitate comparison between trials, we intended to convert variables that can be reported in different metrics, such as days in hospital (mean days per year, per week or per month) to a common metric (e.g. mean days per month).

2.6 Conversion of continuous to binary

If relevant data were available, we would have made efforts to convert outcome measures to dichotomous data. This can be done by identifying cut‐off points on rating scales and dividing participants accordingly into 'clinically improved' or 'not clinically improved'. It is generally assumed that if there is a 50% reduction in a scale‐derived score such as the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS, Overall 1962) or the PANSS (Kay 1986), this could be considered as a clinically significant response (Leucht 2005; Leucht 2005a). We assumed that a 50% reduction of a total score should also be a meaningful cut‐off for other scales. If data based on these thresholds were not available, we used the primary cut‐off presented by the original authors.

2.7 Direction of graphs

Where possible, we entered data in such a way that the area to the left of the line of no effect indicated a favourable outcome for the strategy for the treatment of sexual dysfunction. Where keeping to this would have made it impossible to avoid outcome titles with clumsy double‐negatives we would have reported data where the left of the line indicates an unfavourable outcome and noted this in the relevant graphs.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For this update, two members of the Enhance Review team (KSW and NM) worked independently by using criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) to assess risk of bias in trials. This new set of criteria is based on evidence of associations between overestimation and a high risk of bias in the trial such as sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data and selective reporting.

Where inadequate details of randomisation and other characteristics of trials were provided, we contacted authors of the studies in order to obtain additional information.

We have noted the level of risk of bias in both the text of the review and in the 'Summary of findings' tables.

Measures of treatment effect

1. Binary data

For binary outcomes, we calculated a standard estimation of the risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI)*. It has been shown that RR is more intuitive (Boissel 1999) than odds ratios (ORs) and that ORs tend to be interpreted as RR by clinicians (Deeks 2000). We did not calculate the Number Needed to Treat/Harm (NNT/H). The NNT/H statistic with its CIs is intuitively attractive to clinicians but is problematic both in its accurate calculation in meta‐analyses and interpretation (Hutton 2009). For binary data presented in the 'Summary of findings' table, where possible, we calculated illustrative comparative risks.

* For cross‐over trials we calculated OR and its 95% confidence interval (CI) (See Differences between protocol and review).

2. Continuous data

For continuous outcomes we estimated mean difference (MD) between groups. We would prefer not to calculate standardised effect size measures (standardised mean difference (SMD)). However, had scales of considerable similarity been used, we would have presumed there was a small difference in measurement, and we would have calculated effect size and transformed the effect back to the units of one or more of the specific instruments.

Unit of analysis issues

1. Cluster trials

Studies increasingly employ 'cluster randomisation' (such as randomisation by clinician or practice), but analysis and pooling of clustered data poses problems. Authors often fail to account for intra‐class correlation in clustered studies, leading to a 'unit of analysis' error (Divine 1992) whereby P values are spuriously low, confidence intervals unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated. This causes type I errors (Bland 1997; Gulliford 1999).

Had there been cluster trials included and where clustering was not accounted for in primary studies, we would have presented data in a table, with a (*) symbol to indicate the presence of a probable unit of analysis error. In subsequent versions of this review we will seek to contact first authors of studies to obtain intra‐class correlation coefficients (ICC) for their clustered data and to adjust for this by using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999). Where clustering has been incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we would have presented these data as if from a non‐cluster randomised study, but adjusted for the clustering effect.

For adjustment for clustering a posteriori, the binary data as presented in a report were divided by a 'design effect'. This is calculated using the mean number of participants per cluster (m) and the ICC [Design effect = 1+(m‐1)*ICC] (Donner 2002). If the ICC was not reported it was assumed to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999).

If cluster studies have been appropriately analysed taking into account ICCs and relevant data documented in the report, synthesis with other studies would have been possible using the generic inverse variance technique.

2. Cross‐over trials

A major concern of cross‐over trials is the carry‐over effect. It occurs if an effect (e.g. pharmacological, physiological or psychological) of the treatment in the first phase is carried over to the second phase. As a consequence, on entry to the second phase the participants can differ systematically from their initial state despite a wash‐out phase. For the same reason cross‐over trials are not appropriate if the condition of interest is unstable (Elbourne 2002). Both effects are very likely in severe mental illness, and usually only data from the first phase of corss‐over trials are used, however, we did use data from both phases of cross‐over studies (see Differences between protocol and review).

3. Studies with multiple treatment groups

If a study had involved more than two treatment arms, if relevant, we would have presented the additional treatment arms in comparisons. If data had been binary we would simply have added these and combined them within the two‐by‐two table. If data were continuous we would have combined the data following the formula in section 7.7.3.8 (Combining groups) of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). If the additional treatment arms were not relevant, we would not have reproduced these data.

Dealing with missing data

1. Overall loss of credibility

At some degree of loss of follow‐up, data must lose credibility (Xia 2009). In this review, we planned that should more than 50% of data be unaccounted for, we would not reproduce these data or use them within analyses. If, however, more than 50% of those in one arm of a study were lost, but the total loss was less than 50%, we would have marked such data with (*) to indicate that such a result may well be prone to bias.

2. Binary

In the case where attrition for a binary outcome was between 0% and 50% and where these data were not clearly described, we presented data on a 'once‐randomised‐always‐analyse' basis (an intention‐to‐treat analysis). Those leaving the study early were all assumed to have the same rates of negative outcome as those who completed, with the exception of the outcome of death and adverse effects. For these outcomes the rate of those who stay in the study ‐ in that particular arm of the trial ‐ was used for those who did not. If we had high attrition we would have undertaken a sensitivity analysis to test how prone the primary outcomes were to change when data only from people who complete the study to that point were compared with the intention‐to‐treat analysis using the above assumptions.

3. Continuous

3.1 Attrition

In the case where attrition for a continuous outcome was between 0% and 50%, and data only from people who completed the study to that point were reported, we presented and used these data.

3.2 Standard deviations

If standard deviations (SDs) were not reported, we first tried to obtain the missing values from the authors. If not available, where there were missing measures of variance for continuous data, but an exact standard error (SE) and confidence intervals available for group means, and either P value or T value available for differences in mean, we calculated them according to the rules described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011): When only the SE was reported, SDs were calculated by the formula SD = SE * square root (n). Chapters 7.7.3 and 16.1.3 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) present detailed formulae for estimating SDs from other statistics such as P values, T or F values, confidence intervals or ranges. If these formulae did not apply, we calculated the SDs according to a validated imputation method which is based on the SDs of the other included studies (Furukawa 2006). Although some of these imputation strategies can introduce error, the alternative would be to exclude a given study’s outcome and thus to lose information. We nevertheless examined the validity of the imputations in a sensitivity analysis excluding imputed values.

3.3 Last observation carried forward

We anticipated that in some studies the method of last observation carried forward (LOCF) would be employed within the study report. As with all methods of imputation to deal with missing data, LOCF introduces uncertainty about the reliability of the results (Leucht 2007). Therefore, where LOCF data have been used in the trial, if less than 50% of the data have been assumed, we reproduced these data and indicated that they are the product of LOCF assumptions.

Assessment of heterogeneity

1. Clinical heterogeneity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge clinical heterogeneity. We inspected all studies for clearly outlying people or situations which we had not predicted would arise. When such situations or participant groups arose, we fully discussed these.

2. Methodological heterogeneity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge methodological heterogeneity. We inspected all studies for clearly outlying methods which we had not predicted would arise. When such methodological outliers arose, we fully discussed these.

3. Statistical heterogeneity

3.1 Visual inspection

We visually inspected graphs to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity.

3.2 Employing the I2 statistic

We investigated heterogeneity between studies by considering the I2 method alongside the Chi2 P value. The I2 provides an estimate of the percentage of inconsistency thought to be due to systematic variation rather than due to chance (Higgins 2003). The importance of the observed value of I2 depends on i. magnitude and direction of effects and ii. strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P value from Chi2 test, or a confidence interval for I2). An I2 estimate greater than or equal to around 50% accompanied by a statistically significant Chi2 statistic was interpreted as evidence of substantial heterogeneity (Higgins 2011). When substantial heterogeneity was found in the primary outcome, we explored reasons for heterogeneity (Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results (Egger 1997). These are described in Section 10 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We are aware that funnel plots may be useful in investigating reporting biases but are of limited power to detect small‐study effects. We did not use funnel plots for outcomes as there were less than 10 included studies. In other cases, where funnel plots were meaningful, we sought statistical advice in their interpretation.

Data synthesis

We understand that there is no closed argument for preference for use of fixed‐effect or random‐effects models. The random‐effects method incorporates an assumption that the different studies are estimating different, yet related, intervention effects. This often seems to be true to us and the random‐effects model takes into account differences between studies even if there is no statistically significant heterogeneity. There is, however, a disadvantage to the random‐effects model: it puts added weight onto small studies which often are the most biased ones. Depending on the direction of effect, these studies can either inflate or deflate the effect size. We chose the random‐effects model for all analyses with the exception of Analysis 3.4.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 SWITCHING ANTIPSYCHOTIC: TO QUETIAPINE versus MAINTENANCE RISPERIDONE, Outcome 4 Adverse effects: Psychopathology ‐ average endpoint score (PANSS, high=poor).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

1. Subgroup analyses ‐ only primary outcomes

1.1 Clinical state, stage or problem

We proposed to undertake this review and provide an overview of the effects of strategies for the treatment of sexual dysfunction for people with schizophrenia in general. In addition, however, we tried to report data on subgroups of people in the same clinical state, stage and with similar problems. We were not able to undertake subgroup analyses based on these as there was only one study for each comparison.

2. Investigation of heterogeneity

Where heterogeneity was high, we have reported this. First, we investigated whether data had been entered correctly. Second, if data were correct, we planned to inspect the graph visually and to remove outliers to see if homogeneity was restored. For this review we decided that should this occur with data contributing to the summary finding of no more than around 10% of the total weighting, we would present data. If not, then we would not pool data but would discuss the issues. We know of no supporting research for this 10% cut‐off, but we use prediction intervals as an alternative to this unsatisfactory state.

Sensitivity analysis

We applied all sensitivity analyses to the primary outcome of this review.

1. Implication of randomisation

We aimed to include trials in a sensitivity analysis if they were described in some way so as to imply randomisation. For the primary outcomes we would have included these studies and if there was no substantive difference when the implied randomised studies were added to those with better description of randomisation, then we would have entered all data from these studies.

2. Assumptions for lost binary data

Where assumptions had to be made regarding people lost to follow‐up and missing SDs data (see Dealing with missing data), we would have compared the findings on primary outcomes when we used imputed compared to complete data only. If there was a substantial difference, we would have reported results and discussed them.

3. Risk of bias

We would have analysed the effects of excluding trials that were judged to be at high risk of bias across one or more of the domains of randomisation (implied as randomised with no further details available), allocation concealment, blinding and outcome reporting for the meta‐analysis of the primary outcome. If the exclusion of trials at high risk of bias did not substantially alter the direction of effect or the precision of the effect estimates, then we would have included data from these trials in the analysis.

4. Imputed values

We also planned to undertake a sensitivity analysis to assess the effects of including data from trials where we used imputed values for ICC in calculating the design effect in cluster randomised trials.

If we noted substantial differences in the direction or precision of effect estimates in any of the sensitivity analyses listed above, we did not pool data from the trials in which imputed ICC was used with the other trials contributing to the outcome, but presented them separately.

Results

Description of studies

Please see Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

The updated search identified a total of 30 relevant studies. Two trials met all criteria for study selection for this review in addition to the two studies included in the last version of the review. Fifty studies have now been excluded, no studies are awaiting assessment and no ongoing studies have been identified.

Included studies

The current review includes eight reports describing four studies (Byerly 2008; Gopalakrishnan 2006; Kinon 2006; Kodesh 2003) including a total of 138 participants with schizophrenia or delusional disorder.

1. Methods

We included two cross‐over studies (Kodesh 2003; Gopalakrishnan 2006) and two parallel studies (Byerly 2008; Kinon 2006) All studies were stated to be randomised. Three of the studies were double blind, Kinon 2006 was not blinded.

2. Length of trials

Three studies presented data on 'short‐term' follow‐up: two weeks (Gopalakrishnan 2006), three weeks (Kodesh 2003) and six weeks (Byerly 2008); Kinon 2006 had a follow‐up of four months.

3. Participants

All studies included people with formally operationalised diagnoses. In one study people with schizophrenia were included (Kodesh 2003), in two studies people with schizoaffective disorder were also included (Byerly 2008; Kinon 2006), as diagnosed by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM‐IV). In Gopalakrishnan 2006, participants with schizophrenia or delusional disorder were included, as diagnosed by the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD‐10). In three studies (Byerly 2008; Gopalakrishnan 2006; Kodesh 2003) participants with sexual dysfunction were included. In Kinon 2006 the participants were included if they had hyperprolactinaemia (an abnormally high concentration of prolactin in the blood). The participants also all had moderate sexual dysfunction at baseline.

4. Setting

Kinon 2006 included both inpatients and outpatients; the other three studies included only outpatients. Byerly 2008 was conducted in the USA, Gopalakrishnan 2006 in India, Kodesh 2003 in Israel and Kinon 2006 did not report the country.

5. Study size

All studies were very small: Byerly 2008 included 42 participants, Gopalakrishnan 2006 included 32 participants, Kinon 2006 included 54, and Kodesh 2003 included 10.

6. Intervention

Two trials evaluated adjunctive medication to antipsychotic treatment. Gopalakrishnan 2006 evaluated 25‐50 mg/day sildenafil against placebo and Kodesh 2003 15 mg/day selegiline, also against placebo. Two trials evaluated switching from one antipsychotic to another: Byerly 2008 tested maintenance of risperidone versus switching from risperidone to quetiapine and Kinon 2006 compared maintenance of risperidone or typical antipsychotic versus switching to olanzapine.

7. Outcomes

The following outcomes were reported by the included studies: leaving the study early, sexual function (number of erections, mean duration of erections, improved erections, frequency of satisfactory intercourse, sexual functioning measured on the Arizona Sexual Experience Scale (ASEX), prolactin levels), adverse events (psychopathology, extrapyramidal symptoms).

The following outcomes were not reported by any of the studies: objective assessment of improvement of sexual dysfunction by the trialists, clinically significant improvement of sexual dysfunction as defined by the authors, quality of life, death, non‐specific side effects, economic outcomes (costs of therapy).

7.1 Outcome scales

7.1.1 Sexual dysfunction

i. Patient log data This standardised diary is filled out by the patient over the study period. Data are then extracted by investigators. The outcomes were:

number of erections sufficient for penetration;

mean duration of erections, and

frequency of satisfactory intercourse.

Gopalakrishnan 2006 reported these outcomes in this way.

ii. Aizenberg`s sexual functioning scale (ASF) (Aizenberg 1997) This scale assesses improvement from baseline. In this instrument patients assess their sexual dysfunction with regard to four domains of sexual activity: desire, erection, ejaculation, and satisfaction from sexual performance. Each item is rated in comparison to pre‐treatment function on a four‐point scale (from 'markedly decreased' to 'unchanged or normal'). A total score is calculated by summing the four domain scores. Kodesh 2003 employed this scale.

iii. General Efficacy Questionnaire (GEQ) (Goldstein 1998) This was used by Gopalakrishnan 2006. In this instrument general dichotomous (yes/no) questions are used to assess general treatment efficacy. The most frequently used question of this instrument is "Did the treatment improved your erection?". The questions of interest in the included study were:

if medication improved erections, and

if they would take medication in the future if it was available.

iv. Arizona Sexual Experience Scale (ASEX) (McGahuey 2000) This is a five‐item rating scale that quantifies sex drive, arousal, vaginal lubrication/penile erection, ability to reach orgasm, and satisfaction from orgasm. Possible total scores range from five to 30, with the higher scores indicating more pronounced sexual dysfunction. This scale was used by Byerly 2008.

v. Global Impressions of Sexual Function (GISF) (Michelson 2001) This is a patient‐rated scale that measures the patient’s subjective feelings toward their sexual function. The report consists of four items covering sexual interest/desire, arousal (erection for men and vaginal lubrication for women), climax and overall sexual function. Each item is rated from 1 = Normal to 5 = Severely impaired. This scale was used by Kinon 2006.

7.1.2 Adverse effects ‐ Psychopathology

i. Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (Kay 1987) Byerly 2008, Kinon 2006 and Kodesh 2003 used this to measure exacerbations of psychotic symptoms. This schizophrenia scale has 30 items, each of which can be defined on a seven‐point scoring system varying from one, absent to seven, extreme. It can be divided into three sub‐scales for measuring the severity of general psychopathology, positive symptoms (PANSS‐P), and negative symptoms (PANSS‐N). A low score indicates lesser severity.

ii. Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI) (Guy 1976) This is used to assess both severity of illness and clinical improvement, by comparing the conditions of the person standardised against other people with the same diagnosis. A seven‐point scoring system is usually used with low scores showing decreased severity and/or overall improvement. CGI‐Severity (CGI‐S) is one component of the CGI, which rates illness severity.

iii. Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (Overall 1962) This is used to assess the severity of abnormal mental state. The original scale has 16 items, but a revised 18‐item scale is commonly used. Each item is defined on a seven‐point scale varying from 'not present' to 'extremely severe', scoring from zero to six or one to seven. Scores can range from zero to 126, with high scores indicating more severe symptoms.

iv. Mini‐Mental State Examation (MMSE) (Folstein 1975) This is an 11‐question measure that tests five areas of cognitive function: orientation, registration, attention and calculation, recall, and language. The maximum score is 30. A score of 23 or lower is indicative of cognitive impairment. This scale was used by Kinon 2006.

7.1.3 Adverse effects ‐ extrapyramidal symptoms

i. Simpson‐Angus Scale (SAS) (Simpson 1970) This scale was employed to measure extrapyramidal symptoms. The 10‐item SAS is used to evaluate the presence and severity of parkinsonian symptomatology and other extrapyramidal effects. Higher scores reflect more adverse effects. This scale was used by Kinon 2006.

ii. Barnes Akathisia Scale (Barnes 1989) This is a 12‐item scale consisting of a standardised examination followed by questions rating the orofacial, extremity and trunk movements, as well as three global measurements. Each of these 10 items can be scored from zero (none) to four (severe). Two additional items assess the dental status. The AIMS ranges from zero to 40, with higher scores indicating greater severity. This scale was used by Kinon 2006.

iii. Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) (Guy 1976) This is a 12‐item clinician‐rated scale to assess severity of dyskinesias (specifically, orofacial movements and extremity and truncal movements) in patients taking neuroleptic medications. Items are scored on a zero (none) to four (severe) basis; the scale provides a total score (items one through seven) or item eight can be used in isolation as an indication of overall severity of symptoms. This scale was used by Kinon 2006.

Excluded studies

Fifty studies have now been excluded. Twenty‐seven were excluded as they were not randomised, most of which were observational studies or case‐reports. A further 23 studies were excluded as the participants did not have sexual dysfunction.

Awaiting assessment

No studies are currently awaiting assessment.

Ongoing studies

We identified no ongoing studies.

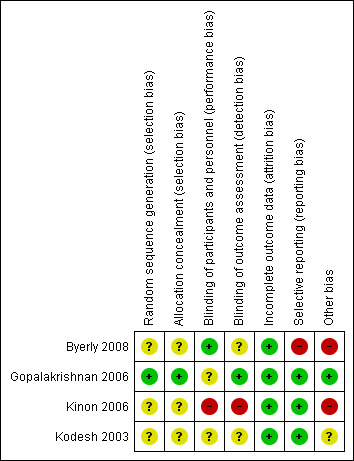

Risk of bias in included studies

See also Figure 1 and Figure 2.

1.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

With regard to random sequence generation and allocation concealment, risk of bias was rated low in one study (Gopalakrishnan 2006), in the remaining studies risk of bias was unclear.

Blinding

Three studies (Byerly 2008; Gopalakrishnan 2006; Kodesh 2003) were described as double blind; risk of bias was low in Byerly 2008 and unclear in the other two studies; blinding of outcome assessors led to a low risk of bias in Gopalakrishnan 2006 and risk of bias remained unclear in the other two studies. Kinon 2006 was an open label study and rated as high risk of bias for blinding.

Incomplete outcome data

All studies were at low risk of bias regarding incomplete outcome data.

Selective reporting

Three studies were at low risk of bias with regard to selective reporting. Byerly 2008 was rated as being at high risk of bias due to missing observations on the outcome without giving reasons and prolactin levels were reported only in a sub‐sample of participants.

Other potential sources of bias

Two studies Byerly 2008; Kinon 2006) were rated as being at high risk of other bias. In Gopalakrishnan 2006 the risk of bias was low, and in Kodesh 2003 it was unclear.

A major flaw of Kodesh 2003 is that reported test statistics (paired t test) do not correspond to reported P values. A detailed examination suggests that t values are reported falsely (ten times higher due to a possible decimal point placement error).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

COMPARISON 1. ADJUNCTIVE TREATMENT ‐ SPECIFIC: SILDENAFIL versus PLACEBO

Gopalakrishnan 2006 (n = 32) compared sildenafil with placebo as additional medication to antipsychotic treatment in a cross‐over trial with two weeks follow‐up. The results were only presented with both phases combined so it was not possible to present only the results from the first phase.

1.1 Objective assessment of improvement of sexual dysfunction

In patient logs, participants reported statistically significantly more erections that were sufficient for penetration when receiving sildenafil compared with those allocated placebo (Analysis 1.1; n = 31, mean difference (MD) 3.20 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.83 to 4.57). Statistically significant differences favouring sildenafil were also found concerning mean scores relating to duration of erections (Analysis 1.2; n = 31, MD 1.18 95% CI 0.52 to 1.84) and frequency of satisfactory intercourse (Analysis 1.3; n = 31, MD 2.84 95% CI 1.61 to 4.07).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ADJUNCTIVE TREATMENT ‐ SPECIFIC: SILDENAFIL versus PLACEBO, Outcome 1 Sexual function (objective assessment): Number of erections sufficient for penetration (over 2 weeks).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ADJUNCTIVE TREATMENT ‐ SPECIFIC: SILDENAFIL versus PLACEBO, Outcome 2 Sexual function (objective assessment): Mean duration of erections (minutes).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ADJUNCTIVE TREATMENT ‐ SPECIFIC: SILDENAFIL versus PLACEBO, Outcome 3 Sexual function (objective assessment): Frequency of satisfactory intercourse (over 2 weeks).

1.2 Subjective assessment of improvement of sexual dysfunction

Participants were more satisfied with sildenafil than with placebo: statistically significantly more participants answered the questions "Has the treatment improved your erections?" (Analysis 1.4; n = 31, odds ratio (OR) 11.76 95% CI 6.54 to 21.13) and "Would you take the drug in future if it were available?" (Analysis 1.5; n = 31, OR 2.50 95% CI 1.48 to 4.22) with 'yes` when receiving sildenafil.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ADJUNCTIVE TREATMENT ‐ SPECIFIC: SILDENAFIL versus PLACEBO, Outcome 4 Sexual function (subjective assessment): Improved erections ('yes') (GEQ).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ADJUNCTIVE TREATMENT ‐ SPECIFIC: SILDENAFIL versus PLACEBO, Outcome 5 Sexual function (subjective assessment): Would take drug in future ('yes') (GEQ).

1.3 Leaving the study early

One participant in the placebo group withdrew consent immediately after randomisation. We found no statistically significant difference between treatment and control group concerning leaving the study early after two weeks follow‐up (Analysis 1.6; n = 32, risk ratio (RR) 0.33 95% CI 0.01 to 7.62).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ADJUNCTIVE TREATMENT ‐ SPECIFIC: SILDENAFIL versus PLACEBO, Outcome 6 Leaving the study early.

COMPARISON 2. ADJUNCTIVE TREATMENT ‐ NON‐SPECIFIC: SELEGILINE versus PLACEBO

Kodesh 2003 compared selegiline with placebo in a small (n = 10) cross‐over trial, with three weeks follow‐up. The results were only presented with both phases combined so it was not possible to present only the results from the first phase.

2.1 Objective assessment of improvement of sexual dysfunction

Sexual function change from baseline measured on the Aizenberg's sexual functioning scale after three weeks follow‐up did not differ significantly between selegiline and placebo phases (Analysis 2.1; n = 10, MD ‐0.40 95% CI ‐3.95 to 3.15).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 ADJUNCTIVE TREATMENT ‐ NON‐SPECIFIC: SELEGILINE versus PLACEBO, Outcome 1 Sexual function (objective assessment): Average change in score (ASF, high=good).

2.2 Leaving the study early

No participants left the study in any phase (Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 ADJUNCTIVE TREATMENT ‐ NON‐SPECIFIC: SELEGILINE versus PLACEBO, Outcome 2 Leaving the study early.

2.3 Adverse effects

No significant difference was found between selegiline and placebo phases regarding extrapyramidal symptoms after three weeks follow‐up measured on the Simpson‐Angus scale (Analysis 2.3; n = 10, MD ‐0.90 95% CI ‐3.88 to 2.08) and psychotic symptoms measured on the PANSS (Analysis 2.4; n = 10, MD 0.50 95% CI ‐0.61 to 1.61).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 ADJUNCTIVE TREATMENT ‐ NON‐SPECIFIC: SELEGILINE versus PLACEBO, Outcome 3 Adverse effects: Extrapyramidal symptoms ‐ average change in score (SAS, high=poor).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 ADJUNCTIVE TREATMENT ‐ NON‐SPECIFIC: SELEGILINE versus PLACEBO, Outcome 4 Adverse effects: Psychopathology ‐ average change in scores (PANSS, high=poor).

COMPARISON 3. SWITCHING ANTIPSYCHOTIC: TO QUETIAPINE versus MAINTENANCE RISPERIDONE

Byerly 2008 (n = 42) compared switching from risperidone to quetiapine with maintenance risperidone, with six weeks follow‐up.

3.1 Subjective assessment of improvement of sexual dysfunction

No statistically significant difference was found between treatment groups in the improvement of sexual dysfunction as measured on the ASEX scale with six weeks follow‐up (Analysis 3.1; n = 36, MD ‐2.02 95% CI ‐5.79 to 1.75).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 SWITCHING ANTIPSYCHOTIC: TO QUETIAPINE versus MAINTENANCE RISPERIDONE, Outcome 1 Sexual function (subjective assessment): Average endpoint score (ASEX, high=bad).

3.2 Surrogate assessment of improvement of sexual dysfunction

Prolactin levels were measured in a sub‐sample of participants. A significant difference was found in favour of the treatment group after six weeks follow‐up (Analysis 3.2; n = 17, MD ‐13.60 95% CI ‐25.76 to ‐1.44).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 SWITCHING ANTIPSYCHOTIC: TO QUETIAPINE versus MAINTENANCE RISPERIDONE, Outcome 2 Sexual function (surrogate assessment): Prolactin levels, average endpoint (ng/ml).

3.3 Leaving the study early

No participants were reported as leaving the study early, however, four participants in the intervention group and two in the control group had missing observations for the primary outcome at the end of the trial, although there was no statistically significant difference found between the treatment groups (Analysis 3.3; n = 42, RR 2.20 95% CI 0.45 to 10.74).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 SWITCHING ANTIPSYCHOTIC: TO QUETIAPINE versus MAINTENANCE RISPERIDONE, Outcome 3 Leaving the study early.

3.4 Adverse effects

No statistically significant difference was found between switching to quetiapine and maintenance risperidone regarding psychotic symptoms measured on the PANSS scale after six weeks follow‐up (Analysis 2.4; n = 42, MD ‐0.60 95% CI ‐4.35 to 3.15).

COMPARISON 4. SWITCHING ANTIPSYCHOTIC: TO OLANZAPINE versus MAINTENANCE OF RISPERIDONE/FGA (First Generation Antipsychotic)

Kinon 2006 (n = 54) compared switching from risperidone to quetiapine with maintenance of risperidone or typical antipsychotic, with four months follow‐up.

4.1 Subjective assessment of improvement of sexual dysfunction

A statistically significant difference was found in the improvement of sexual dysfunction measured on the GISF scale in favour of switching to olanzapine after four months follow‐up (Analysis 4.1; n = 54, MD ‐0.80 95% CI ‐1.55 to ‐0.05). This result is a product of last observation carried forward assumptions.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 SWITCHING ANTIPSYCHOTIC: TO OLANZAPINE versus MAINTENANCE RISPERIDONE/FGA, Outcome 1 Sexual function (subjective assessment): Average change in score (GISF, high=poor).

4.2 Surrogate assessment of improvement of sexual dysfunction

A statistically significant difference was found in prolactin levels in favour of the treatment group after four months follow‐up (Analysis 4.2; n = 54, MD ‐30.84, 95% CI ‐47.46 to ‐14.22). This result is a product of last observation carried forward assumptions.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 SWITCHING ANTIPSYCHOTIC: TO OLANZAPINE versus MAINTENANCE RISPERIDONE/FGA, Outcome 2 Sexual function (surrogate assessment): Prolactin levels, average change (ng/ml).

4.3 Leaving the study early

Nine participants in the switch to olanzapine group and four in the maintenance group left the study early and there was no statistically significant difference between the treatment groups (Analysis 4.3; n = 54, RR 0.25 95% CI 0.79 to 6.43).

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 SWITCHING ANTIPSYCHOTIC: TO OLANZAPINE versus MAINTENANCE RISPERIDONE/FGA, Outcome 3 Leaving the study early.

4.4 Adverse effects

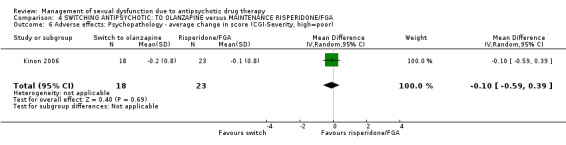

4.4.1 Psychopathology

No statistically significant difference was found between switching to olanzapine and maintenance risperidone or typical antipsychotic regarding psychotic symptoms over four months measured on the PANSS scale (Analysis 4.4; n = 41, MD 0.20 95% CI ‐6.93 to 7.33), the BPRS scale (Analysis 4.5; n = 41, MD ‐0.30 95% CI ‐4.57 to 3.97), the CGI‐severity scale (Analysis 4.6; n = 41, MD ‐0.10 95% CI ‐0.59 to 0.39) and the MMSE scale (Analysis 4.7; n = 41, MD 0.0 95% CI ‐1.35 to 1.35).

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 SWITCHING ANTIPSYCHOTIC: TO OLANZAPINE versus MAINTENANCE RISPERIDONE/FGA, Outcome 4 Adverse effects: Psychopathology ‐ average change in score (PANSS, high=poor).

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 SWITCHING ANTIPSYCHOTIC: TO OLANZAPINE versus MAINTENANCE RISPERIDONE/FGA, Outcome 5 Adverse effects: Psychopathology ‐ average change in score (BPRS, high=poor).

4.6. Analysis.

Comparison 4 SWITCHING ANTIPSYCHOTIC: TO OLANZAPINE versus MAINTENANCE RISPERIDONE/FGA, Outcome 6 Adverse effects: Psychopathology ‐ average change in score (CGI‐Severity, high=poor).

4.7. Analysis.

Comparison 4 SWITCHING ANTIPSYCHOTIC: TO OLANZAPINE versus MAINTENANCE RISPERIDONE/FGA, Outcome 7 Adverse effects: Psychopathology ‐ average change in score (MMSE, high=good).

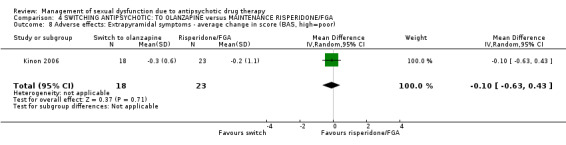

4.4.2 Extrapyramidal symptoms

Extrapyramidal symptoms were measured on three scales, no statistically significant difference was found between the treatment groups on any of the scales after four months follow‐up: the Barnes Akathisia Scale (Analysis 4.8; n = 41, MD ‐0.10 95% CI ‐0.63 to 0.43), the Simpson‐Agnus Scale (Analysis 4.9; n = 41, MD ‐0.90, 95% CI ‐2.25 to 0.45), or the AIMS scale (Analysis 4.10; n = 41, MD ‐0.30 95% CI ‐1.19 to 0.59).

4.8. Analysis.

Comparison 4 SWITCHING ANTIPSYCHOTIC: TO OLANZAPINE versus MAINTENANCE RISPERIDONE/FGA, Outcome 8 Adverse effects: Extrapyramidal symptoms ‐ average change in score (BAS, high=poor).

4.9. Analysis.

Comparison 4 SWITCHING ANTIPSYCHOTIC: TO OLANZAPINE versus MAINTENANCE RISPERIDONE/FGA, Outcome 9 Adverse effects: Extrapyramidal symptoms ‐ average change in score (SAS, high=poor).

4.10. Analysis.

Comparison 4 SWITCHING ANTIPSYCHOTIC: TO OLANZAPINE versus MAINTENANCE RISPERIDONE/FGA, Outcome 10 Adverse effects: Extrapyramidal symptoms ‐ average change in score (AIMS, high=poor).

Discussion

Four studies are included in this review: two estimate the effects of drugs compared against placebo to treat sexual dysfunction (Gopalakrishnan 2006 and Kodesh 2003), and two compare the effect of switching to a different antipsychotic with maintaining current antipsychotic treatment (Byerly 2008 and Kinon 2006). All four studies were small and had a follow‐up of less than four months. As each study investigated a different intervention it was not possible to undertake any meta‐analysis.

Summary of main results

1. Adjunctive treatment ‐ Specific: Sildenafil versus placebo

1.1 Sexual functioning

There is limited evidence that sildenafil can improve antipsychotic‐induced sexual dysfunction in men, increasing the number of erections sufficient for penetration, the mean duration of erections, and the frequency of satisfactory intercourse over the course of two weeks.

1.2 Adverse effects

This study did not report data on adverse effects. It is, therefore, impossible to tell how safe sildenafil is when added to antipsychotic drugs.

2. Adjunctive treatment ‐ Non‐specific: Selegiline versus placebo

2.1 Sexual functioning

A single very small, short study did not find selegiline to be superior to placebo in treating antipsychotic‐induced sexual dysfunction in men after three weeks.

2.2 Adverse effects

No differences in extrapyramidal movement disorders and exacerbation of schizophrenic symptoms were found between selegiline and placebo after three weeks.

3. Switching antipsychotic: to quetiapine versus maintenance of risperidone

3.1 Sexual functioning

Switching from risperidone to quetiapine did not improve sexual functioning in men and women when measured on the ASEX scale after six weeks. However, prolactin levels (a surrogate measure of sexual function) were significantly lower in a sub‐sample of patients who had switched to quetiapine.

3.2 Adverse effects

No difference in the severity of schizophrenic symptoms was found between patients who switched to quetiapine or remained on risperidone after six weeks.

4. Switching antipsychotic: to olanzapine versus maintenance of risperidone/typical antipsychotic

4.1 Sexual functioning

Male and female patients who switched to olanzapine showed improved sexual functioning after four months measured on the GISF scale and reduced prolactin levels (a surrogate measure of sexual function) compared with patients remaining on risperidone or typical antipsychotic.

4.2 Adverse effects

No difference was found in schizophrenic symptoms or extrapyramidal symptoms between patients switching to olanzapine or remaining on risperidone or typical antipsychotic after four months.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The two studies that focused on adjunctive therapies included only male participants. The intervention in Gopalakrishnan 2006 was sildenafil, a drug typically prescribed to men to treat erectile dysfunction, which was the focus of the study. However, the intervention in Kodesh 2003 was selegine, a drug used as an antiparkinsonian medication. Both studies had very short follow‐up periods (two and three weeks) and were very small cross‐over studies. It is presumable that such methods are inappropriate for evaluation of sexual dysfunction. Cross‐over studies are suitable for the evaluation of treatments for short‐term symptoms without carry‐over effects. Whether sexual dysfunction can be considered acute and drug treatments as free from carry‐over effects, remains questionable

The two studies that focused on switching antipsychotic included both male and female participants, but were also small studies. Although the follow‐up periods were slightly longer (six weeks to four months) they still do not allow long‐term outcome measures to be assessed.

The trials were conducted in India, Israel and the USA, but there is no indication that sexual problems differ by region or race (Tharyan 2006), therefore, if the results were more authoritative they could be widely applicable. No studies reported on quality of life or the economic aspects of treating sexual dysfunction.

We did not identify any trialsinvestigating other strategies for treating sexual dysfunction in people taking antipsychotics ‐ drug holidays and reducing the dose of antipsychotic.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the current evidence is very low based on GRADE. The limited number of studies, the small number of participants, the inclusion of only men in two of the studies, and two studies being cross‐over trials are the main methodological limitations to the quality of the evidence. One trial had a high risk of bias for selective reporting of outcomes. With regard to sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding and selective reporting, the remaining studies were considered to be at a low or unclear risk of bias. Three of the studies were very short in duration (two to six weeks); one study was of moderate duration (four months) but was an open label trial.

Potential biases in the review process

The extensive search was planned to be highly sensitive, however, we may have failed to identify some relevant studies.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

No other reviews covering the same topic are available to compare their results with those obtained from this review.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

1. For people with schizophrenia and sexual dysfunction

For men with schizophrenia taking antipsychotic medication and experiencing erectile dysfunction as an adverse effect of the pharmacological treatment, sildenafil may be a useful treatment option as additional medication. Men should be aware that this conclusion is based on limited data and that long‐term effects are unknown. Drug‐drug interactions may be a problem and sildenafil is contraindicated in certain instances, particularly in people on concurrent nitrates (Tharyan 2006).Men and women with antipsychotic‐induced sexual dysfunction caused by risperidone or typical antipsychotic may find that switching to olanzapine improves their sexual functioning. Both men and women with both schizophrenia and sexual dysfunction could reasonably request that their treatment, whatever that may be, should be undertaken only in the context of a randomised study.

2. For clinicians

Sildenafil may be a useful option to improve erectile functioning in the treatment of antipsychotic‐induced erectile dysfunction in men with schizophrenia, and switching to olanzapine from risperidone or typical antipsychotic may be useful in managing sexual dysfunction in men and women. However, although the studies in this review are pioneering they are far too small and short to be the source of robust evidence. Clinicians will continue treatment, based on sources other than trials, until they feel that such levels of evidence are inadequate.

3. For managers/policy makers

For people facing cost‐effectiveness and cost‐utility decisions, currently, there is no useful trial‐based data to support decision making.

Implications for research.

1. General

The four trials in this review were mostly well reported but future studies should ensure that they comply with the CONSORT statement (Moher 2010).

2. Specific

Randomised controlled trials are needed to provide evidence for the effects of different strategies (dose reduction, drug holidays, symptomatic treatment, switching) to manage sexual adverse events in patients receiving antipsychotic medication.

These studies should focus also on other dysfunctions such as erectile dysfunction and include both men and women who experience antipsychotic‐induced sexual dysfunction. All outcomes should be investigated on the short, medium as well as long term and adverse effects should be reported in detail. Data on quality of life, partner satisfaction with the intervention, and economic outcomes should be included. We suggest an outline of such a study in Table 5.

1. Suggestions for trial of management of antipsychotic‐induced sexual dysfunction.

| Methods | Participants | Interventions | Outcomes | Notes |