Abstract

Cellular optogenetics employs light-regulated, genetically encoded protein actuators to perturb cellular signaling with unprecedented spatial and temporal control. Here, we present a potentially generalized approach for transforming a given protein of interest (POI) into an optogenetic species. We describe the rational and methods by which we developed three different optogenetic POIs utilizing the Cry2-Cib photodimerizing pair. The process pipeline is highlighted by (1) developing a low level, constitutively active POI that is independent of endogenous regulation, (2) fusion of the mutant protein of interest to an optogenetic photodimerizing system, and (3) light-mediated recruitment of the light-responsive POI to specific subcellular regions.

1. Introduction

1.1. Optogenetics

Cellular optogenetics employs genetically encoded, light-regulated proteins to drive changes in cellular signaling. Pairing molecular biology and light mediated control of protein activity yields systems that can act globally on whole cells or locally at subcellular sites on timescales from seconds to hours. We have developed optogenetic analogs of endogenous proteins that control cell migration (Hughes & Lawrence, 2014), apoptosis (Hughes et al., 2015), and kinase signaling (O’banion et al., 2018).

Desired characteristics of an optogenetic protein of interest (POI) is that it is (1) silent in the dark and (2) activated in response to a minimally invasive light. Light-activated proteins have been developed by introducing light sensitive motifs into the POI. However, generating these constructs generally requires a significant engineering effort and may only provide partial control over protein activity. A key challenge is to identify the precise location on the POI to position the photoreceptor so that activity is compromised in the dark but liberated upon illumination.

We have developed an alternative and potentially generalizable approach for generating optogenetic POIs. The two-step strategy requires (1) the acquisition of a low level, constitutively active, analog of the POI. This analog is (2) fused to a photoreceptor which, for the constructs described herein, is the cryptochrome photolyase homology region (Cry2). The latter, upon excitation at the appropriate wavelength (vide infra), associates with its binding partner (Cib). The POI-Cry2 construct is designed to be cytoplasmic and functionally silent in the dark. Upon illumination, the POI-Cry2 conjugate binds to Cib, which is sequestered at a specific subcellular region. This generates a dramatic increase in the local concentration of the POI furnishing spatially focused activity.

The inspiration for the design of our optogenetic constructs is derived from the Michaelis-Menten equation (v0 =kcat[E][S]/(KM+[S])). The reaction rate for an enzyme-catalyzed reaction is dependent on the turnover number of an enzyme (kcat), the substrate concentration at which the reaction rate is half maximal (KM) and the concentrations of both enzyme [E] and substrate [S]. A dramatic light-driven increase in [E] at a specific subcellular location should result in an increase in the overall reaction rate. We’ve applied this concept to cofilin, which severs F-actin, and the cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA), which catalyzes the phosphorylation of an array of proteins. In addition, an analogous strategy has been used to generate an optogenetic analog of the pro-apoptotic protein Bax, which forms pore-generating oligomers at the outer mitochondrial membrane.

1.2. An optogenetic engineering strategy

Each of the three optogenetic POIs described herein has a specific subcellular location of activity. Cofilin mediates cellular migration via modulation of the actin cytoskeleton, Bax triggers apoptosis at the outer mitochondrial membrane, and PKA is a highly compartmentalized enzyme with discrete activity profiles at the plasma membrane, mitochondria, and other cellular locations. We note that many effector proteins require an appropriate interaction with a target, be it a subcellular location or a protein/protein interaction, to induce an action and/or transmit a signal. The primary engineering strategy that we’ve developed is based on the ability to bring the POI close to its intended site of activity in a light-dependent fashion. Consequently, the optogenetic engineering approach should prove applicable to POIs that act upon substrates positioned at distinct subcellular sites.

As described in the introduction, we’ve taken an approach based on the Michealis-Menten equation (v0 =kcat[E][S]/(KM+[S])) in order to generate optogenetic constructs that are silent and diffusely distributed in the dark. Illumination furnishes a concentration ([E]) jump at designated intracellular sites sufficient to drive the desired protein activity. A key strategic element associated with our approach is the design of an optogenetic POI that is functionally silent when disseminated throughout the cytoplasm. In order to achieve this, we take into account (1) the mechanism of POI regulation, (2) the location of native POI activity, and (3) protein-protein interactions between the POI and its substrates. Our strategy requires the generation of POI mutants that are (1) diffuse in the cytosol by disrupting subcellular localization of the native protein, (2) impervious to up- or downregulation by endogenous signaling, and (3) exhibit reduced activity at concentrations comparable to that of the wild type POI. Fortunately, site-directed mutagenesis studies constitute one of the very first experiments performed on newly described proteins, which offer insight into structure function activity relationships. Consequently, in many instances, the strategy for generating low level, constitutively active proteins is straightforward. In the examples described below, all optogenetic constructs contain an appended fluorescent protein to assist in visualizing the location of the POI.

2. Preparing low level, constitutively active POIs

Cofilin mutants

Cofilin activity is dramatically reduced by phosphorylation at S3. Consequently, a constitutively active (i.e., unregulated) cofilin is readily generated via a S3A mutation. In order to achieve low level cofilin activity so that F-actin is not severed in the dark, we identified three mutations (S120A, S94D, and K96Q) from the literature (Moriyama & Yahara, 2002), which have been shown to compromise activity by interfering with the ability of cofilin to bind to F-actin. Three low level constitutively active cofilin double mutants were prepared: cofilinS3A/S120A, cofilinS3A/S94D, and cofilinS3A/K96Q. We sought to identify a double mutant that displays a significant concentration-dependent increase in activity at ~0.5 μM, which is approximately the intracellular concentration of cofilin. An in vitro F-actin severing assay was used to assess the activity of these constructs at various concentrations (Hughes & Lawrence, 2014). The cofilinS3A/S120A analog displays an order of magnitude change in F-actin severing activity from 0.2 to 1.0 μM, suggesting that a sudden concentration jump of fivefold could transform low activity cofilinS3A/S120A into an efficient F-actin severing protein. The double mutant cofilinS3A/S120A was appended to the Cry2 photoreceptor: cofilinS3A/S120A-Cry2-mCh (optoCofilin; where mCh=mCherry for visualization purposes). A second construct, LifeAct-Cib-GFP, positions Cib (the binding partner of Cry2) at the cytoskeleton via an F-actin binding element (LifeAct) (Riedl et al., 2008). Simultaneous transfection of cells with optoCofilin and LifeAct-Cib-GFP furnishes an optogenetic system that recruits cofilin to the cytoskeleton.

Bax mutants

Like cofilin, Bax is regulated via phosphorylation. Phosphorylation of Bax at S184 sequesters the protein in the cytoplasm, which prevents Bax from associating with the outer mitochondrial membrane where it triggers apoptosis (Nechushtan, Smith, Hsu, & Youle, 1999). In response to an apoptotic stimulus, Bax is dephosphorylated, migrates to the mitochondria, oligomerizes, and generates pores in the outer mitochondrial membrane. An optogenetic version of Bax was designed by first removing the ability of native Bax to migrate to the mitochondria. The phosphomimetic S184E mutant has previously been shown to be cytoplasmic (Nechushtan et al., 1999). Based on this observation, we constructed Cry2-mCh-BaxS184E (optoBax) and demonstrated that it is cytoplasmic in the dark in cells expressing Cib at the outer mitochondrial membrane (Hughes et al., 2015). Illumination provokes migration of the optogenetic Bax to the mitochondria (vide infra).

PKA mutants

The cAMP dependent protein kinase (PKA) holoenzyme exists as a tetramer composed of two catalytic subunits (C) and two regulatory (R) subunits. cAMP binds to the R subunits, which releases the C subunits, allowing them to phosphorylate local protein substrates. First, based on literature precedent, a W196R mutation/substitution was introduced in the C subunit, where it abolishes binding of the R subunit (Gibson & Taylor, 1997). This generates a cAMP-independent PKA. Second, the catalytic activity of the C subunit was dramatically reduced in order to prevent widespread catalytic activity of the cAMP-independent (i.e., constitutively active) enzyme. Three mutations were screened that are known to either impair substrate binding or catalytic activity. The CE203A, CY204A, and CF327A mutants display reduced activity that is 43%, 5.6%, and 1.2% as active, respectively, of wild type C subunit. As in the examples of optogenetic cofilin and Bax, the C subunit mutants were appended to the Cry2 photoreceptor, which can then be directed to specific subcellular sites in a light-dependent fashion using the Cry2 binding partner Cib.

2.1. Protocol for generating site-directed mutants

A general protocol for generating site-directed mutants is adapted from the QuickChange mutagenesis kit:

- Design primers for site-directed mutagenesis so that they have a minimum Tm of 72°C.

- Note: Primers for site-directed mutagenesis should be designed using the Agilent QuickChange primer design web tool: https://www.chem.agilent.com/store/primerDesignProgram.jsp

Combine the following: 125ng of each primer, 50ng of template DNA, 4 μL of 2.5mM dNTPs, 5 μL of 10× PfuUltra buffer, 1 μL of PfuUltra Hotstart DNA polymerase, and ddH2O to a final volume 50 μL.

Treat the PCR products obtained from this reaction with DpnI for 1h at 37°C and use 1 μL of this solution for the transformation of 50 μL of Invitrogen Max Efficiency DH5α E. coli cells.

The next day, choose individual bacterial colonies to be amplified in selective LB media and scale up to miniprep DNA extraction for sequence verification.

3. Fusion of the POI to Cry2

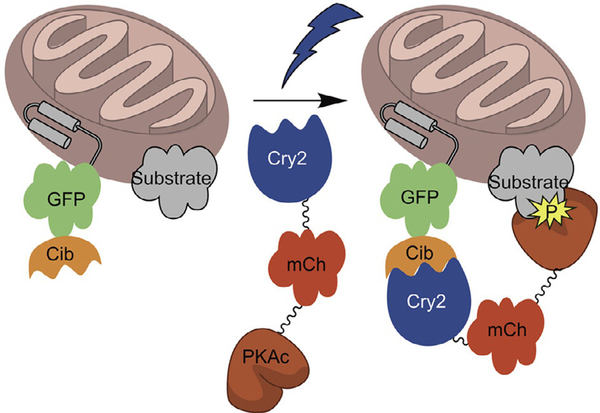

In order to drive local light-dependent concentration jumps for a given POI, fusion to a photodimerizing system is necessary (Fig. 1). Two photoreceptors comprise the entirety of blue light regulated optogenetic dimerization: cryptochrome 2 (Cry2) and LOV. Both are flavin binding photoreceptors with Cry2 binding to FAD and LOV to FMN and absorb light between 400 and 500nm (O’banion & Lawrence, 2018). The best characterized are Cry2 from Arabidopsis thaliana and LOV2 from Avena sativa. As noted above, Cry2 associates with its binding partner, Cib, upon excitation with blue light.

Fig. 1.

Schematic for light-induced recruitment of a POI fused to Cry2-mCh to the OMM. Reproduced with permission from O’Banion, C. P., Priestman, M. A., Hughes, R. M., Herring, L. E., Capuzzi, S. J., & Lawrence, D. S. (2018). Design and profiling of a subcellular targeted optogenetic cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Cell Chemical Biology, 25(1), 100–109 e108. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2017.09.011.

There are several choices available with respect to the design of fused POI/photoreceptor construct, especially if a fluorescent protein is part of the optogenetic species. First, in the case of the Cry2/Cib binding partner, Cry2 is generally recruited best if Cib is immobilized at a subcellular location of interest and the POI is fused to the Cry2 construct. Second, a determination of whether a POI is best placed at the N- or C-terminus of the construct (or inserted between: Cry2-POI-fluorescent protein) is dependent, in part, on the POI itself. For example, the POI may require a free N-terminus for activity. In the absence of strict POI structural requirements, we have found that some experimentation is necessary to identify the best-behaved constructs. For example, the C subunit of PKA, when fused to the N-terminus of Cry2, does not recruit to Cib upon illumination. By contrast, fusion of the C subunit to the C-terminus of Cry2 provides constructs that are efficiently recruited to Cib in a light-dependent fashion (O’banion et al., 2018). Interestingly, in the case of cofilin, the exact opposite behavior is observed (Hughes & Lawrence, 2014).

3.1. Protocol for the construction of POI/Cry2/fluorescent protein constructs

The following general protocol describes our strategy for fusing the POI to the N- or C-termini of Cry2-mCh (in a pmCherry-N1 plasmid backbone) to generate the following constructs: Bax-Cry2-FLAG-mCh, Cry2-mCh-Bax, Cofilin-Cry2-FLAG-mCh, Cry2-mCh-Cofilin and Cry2-mCh-C (PKA). The protocol is as follows:

Cloning of POI-Cry2-FLAG-mCherry into pmCherry-N1 vector by splice overlap extension PCR

- Design and generate primers that contain: (1) an appropriate gene specific region for amplification of POI, (2) any linkers to be appended, and (3) an additional region containing 30–40 homologous bases to the other DNA fragment to be spliced together (see examples for cloning below).

- Forward primer for POI: 5′-XhoI-POI gene specific region-3′

- Reverse primer for POI: 5′-gene specific region-3′

- Forward primer for Cry2: 5′-POI homology region-linker region-Cry2 gene specific region-3′.

- Reverse primer for Cry2: 5′-XmaI-FLAG-Cry2 gene specific region-3′

Separately PCR amplify the POI and Cry2 gene constructs with Phusion polymerase and primers encoding linkers and homology regions.

After subsequent gel purification of the individual isolates, use aliquots (6 μL of each PCR isolate) of the obtained DNA fragments to combine with a cocktail of 1.5 μL each of the forward primer for the POI (a. from primer list above) and reverse primer for Cry2 (d. from primer list above) (10 μM stocks), 4 μL dNTPS (2.5mM stock), 3 μL of 10× Phusion HF buffer, 8 μL ddH2O, and 0.5 μL of the Phusion polymerase enzyme and subject this mix to splice overlap extension PCR. Standard thermocycling conditions can be applied for this reaction.

Purify the resultant PCR fragments via agarose gel and subject them to restriction digestion. The resultant fragments should be ligated into a plasmid backbone containing pmCherry-N1 with XhoI and XmaI sites to yield 5′-XhoI-POI-GGSGGS-Cry2-GGSDYKDDDKARDPPVAT-XmaI-mCh-3′.

Cloning of Cry2-mCh-POI in pCry2-mCherry-N1 vector

PCR amplify POI with primers appending BsrGI and NotI restriction digestion sites as well as a six amino-acid N-terminal linker, followed by gel purification and isolation of the appropriately sized PCR amplicon.

The pCry2-mCherry-N1 should be analogously linearized via BsrGI/NotI restriction digestion, and both digested PCR and vector fragments should be ligated via T4 DNA ligase using standard procedures. The resultant construct will yield Cry2-mCh-GGSGGS-POI.

In the case of optoPKA, inclusion of an additional 16 amino acid tether as an alternative to the six amino acid tether, followed by BsrGI/NotI restriction and ligation should generate Cry2-mCh-SAGGSAGGSAGGSAGG-C (PKA).

For generating the corresponding Cib constructs fused to the respective anchoring peptide sequences, the following protocol can be employed to generate Tom20MLS-Cib-GFP and LifeAct-Cib-GFP in a phCMV-GFP vector. Tom20MLS is an N-terminal fragment of the Tom20 protein that is anchored to the outer mitochondrial membrane. The protocol entails the following steps:

PCR amplify Tom20MLS, LifeAct (anchoring peptides) and Cib (Kennedy et al., 2010) separately by PCR Phusion polymerase. After gel isolation and purification of the fragments, combine aliquots of the purified DNA and subject them to overlap extension PCR, as before.

Digest the resultant constructs with XhoI and HindIII enzymes, followed by ligation into an analogously digested phCMV-GFP vector backbone to generate the final construct(s) expressed as (anchoring peptide)-GGSGGS-Cib-GGSGGSRSFEF-GFP.

A somewhat modified protocol can be used to generate Cib-CAAX (lacking GFP) from Cib-GFP-CAAX (Addgene 26867) viaPCR-mediated site-directed mutagenesis to insert a poly-lysine sequence CAAX box [GGSGKKKKKKSKTK-CVIM] and a stop codon between Cib and GFP.

4. Characterization and validation of light mediated translocation

4.1. Experimental setup and considerations

A characteristic displayed by many genetically encoded light-activated proteins, such as the Cry2/Cib system, is functional reversibility. The latter transpires by exposing the optogenetic species to a series of light and dark cycles. Under these circumstances, optogenetic proteins display a characteristic recruitment or activity half-life following illumination. For example, an optogenetic Bax mutant fused to the C-terminus of Cry2-mCh (i.e., Cry2-mCh-Bax) displays a longer residence time at mitochondria than its N-terminal counterpart (i.e., Bax-Cry2-mCh) (Hughes et al., 2015). Mitochondrial recruitment serves as a direct means for quantifying light mediated translocation. Mitochondria have clear morphology that allow for obvious qualitative assessment of translocation as well as simple quantitative measurements of translocation from the cytoplasm to the mitochondria. In addition, imaging mitochondrial recruitment can be performed on either a widefield or confocal microscope whereas plasma membrane recruitment (another popular region of interest) requires the use of confocal microscopy for precise measurement of light-mediated recruitment.

4.2. Experimental design

Short single pulse recruitment vs. multiple pulse recruitment

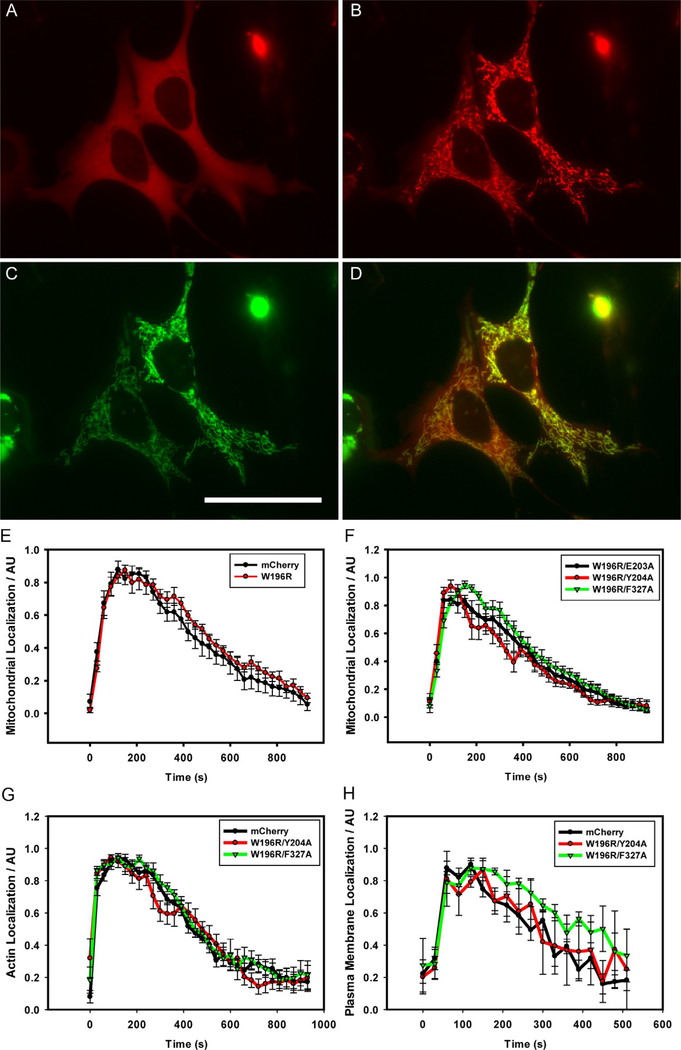

Recruitment of an optogenetic protein to a subcellular location can be imaged on a microscope and analyzed by initiation with either a single pulse of light or sustained light pulses. Short, single pulses (100 ms) at 488nm provide information about the sensitivity of an optogenetic system as well as qualitative and quantitative information about reversibility (Fig. 2). On the other hand, multiple short pulses of light establish the maximal possible recruitment of the POI. The latter defines the dynamic range of recruitment and assists in identifying an appropriate light dosing regimen for the biological system to be studied.

Fig. 2.

Light-Triggered optoPKA association with, and subsequent dissociation from, the OMM, cytoskeleton, and PM. All optoPKA constructs contain the mCh fluorescent protein: Cry2-mCh-CW196R/E203A (A–D and F), Cry2-mCh (E), control, Cry2-mCh-CW196R (E), Cry2-mCh-CW196R/Y204A (F–H), and Cry2-mCh-CW196R/F327A (F–H). The following Cib constructs were employed to recruit optoPKA to specific intracellular sites: Tom20MLS-Cib-GFP (OMM-Cib in A–F) at the OMM; LifeAct-GFP-Cib (LifeAct-Cib) in (G) at the actin cytoskeleton; Cib-GFP-CAAX (PM-Cib) in (H) at the PM. Visualization of the mCh label in PKA196R/E203A (A) before and (B) 1min after stimulation with a 100ms, 488nm light pulse. (C) Visualization of the GFP label in OMM-Cib (Tom20MLS-Cib-GFP), where (D) is an overlay of (B and C). (E–H) Association and subsequent dissociation of optoPKA with and from the PM, OMM, and the cytoskeleton were monitored via mCh fluorescence. A single 100ms pulse (FITC cube) was employed to initiate recruitment of the optoPKA constructs to designated sites. Experiments were performed on either a wide-field (OMM-Cib, LifeAct-Cib) or confocal (PM-Cib) microscope. N=3 cells per group. Scale bar, 50 μm. Data expressed as meanSEM. Reproduced with permission from O’Banion, C. P., Priestman, M. A., Hughes, R. M., Herring, L. E., Capuzzi, S. J., & Lawrence, D. S. (2018). Design and profiling of a subcellular targeted optogenetic cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Cell Chemical Biology, 25(1), 100–109 e108. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2017.09.011.

4.3. Light-mediated translocation of opto-POIs

A general protocol for the characterization and validation of light mediated translocation of the opto-POI constructs is outlined here:

4.3.1. Equipment and materials

Fluorescent microscopy (widefield) imaging is performed with an inverted Olympus IX81 microscope equipped with a Hamamatsu C848 camera, 60× oil immersion Plan S-Apo objective and FITC and TxRed filter cubes (Semrock).

Metamorph Imaging Suite

Opaque heat, humidity, and atmosphere (5% CO2) controlled microscope enclosure

37°C tissue culture incubator with 5% CO2 and 95% humidity

35mm glass bottom dishes (Mattek)

Fluorophore-labeled purified proteins

DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100U/mL penicillin, 100μg/mL streptomycin.

Lebowitz L-15 media without phenol red (Gibco).

Mammalianexpressionvectorcontainingthesequencefor(photoswitch)-fused to fluorescent protein spectrally compatible with our system

Cell lines of interest

Transfection reagent (Polyplus transfection 114–07)

4.3.2. Protocol

Day 1

-

1

Plate cells in 35mm glass bottomed MatTek dishes at 75,000 cells per dish and return to incubator for 16–24h.

Day 2

-

2

Using DMEM and Polyplus-transfection reagent, transfect cells with the plasmids containing photoswitch according to transfection protocol (each plasmid in a 1:1 ratio with a total of 2μg DNA per well; 1:2 ratio of DNA: jetPrime transfection cocktails should be incubated for 10min at room temperature (RT) before being added to each well and allowed to incubate).

-

3

4–6h later, aspirate media and exchange for fresh DMEM, followed by overnight incubation.

Day 3

-

4

On the day of imaging, aspirate and exchange media for complete Lebowitz L-15 media without phenol red for live cell imaging.

Day 4

-

5

Allow for dishes to equilibrate in heated incubators (32°C, 45% humidity) for at least 30min prior to imaging.

-

6

In live cell experiments, initiate whole cell recruitment of either N- or C-termini fused Cry2-mCh constructs to the respective peptide-anchored-Cib-GFP with a 100ms pulse of blue light (488nm) using FITC filter cube.

-

7

Monitor time-lapse images via the TxRed filter cube (500ms pulse) and acquire images every 30 s over 15min during the course of the experiment; collected images should be processed by ImageJ.

4.4. Data analysis

Data analysis is performed in ImageJ (or other analysis software). Generally, data are presented as the fold change in localization relative to the initial timepoint. For mitochondrial recruitment, we first calculate the mitochondrial:cytoplasmic ratio of the POI and then normalize to the first timepoint (F/F0). Generally, we define three regions of interest (ROIs) within the mitochondrial area and three ROIs in adjacent cytoplasmic regions as well as a number of background measurements from regions containing either nontransfected cells or no cells. Background is subtracted from cellular ROIs and the ratio of a mitochondrial ROI to its adjacent cytoplasmic ROI is calculated.

The FIJI (ImageJ) software package is used for data analysis. A general protocol for the analysis of image data using ImageJ consists of the following steps:

For each cell, collect images from two channels: Cib-GFP (acts as label for either mitochondria, cytoskeleton or the plasma membrane) and Cry2-mCh.

Define three mitochondrial ROIs and three adjacent cytoplasmic ROIs for each cell, as well as three background ROIs.

Record the mean fluorescent intensity for each ROI and subtract background fluorescence from each ROI.

The ratio of mitochondrial:cytoplasmic fluorescence is obtained by dividing background corrected mitochondrial ROI fluorescence by adjacent background corrected cytoplasmic ROI fluorescence.

Steps 1–5 should then be repeated for every image in the series.

Normalize values between 0 and 1 for comparison or as fold change relative to the initial time point.

5. Characterization and validation of light-mediated biological activity of optogenetic constructs

A critical element of optogenetic protein design is characterization of the optoPOI using a well-defined cellular assay.

5.1. Filopodia induction and cell spreading by light activation of optoCofilin

optoCofilin

The cofilinS3A/S120A-Cry2-mCh (optoCofilin) and LifeAct-Cib-GFP constructs were expressed in MTLn3 cells. The light-induced (488nm, 100ms pulse) association of optoCofilin with the cytoskeleton was imaged and quantified. optoCofilin does not associate with the cytoskeleton in the dark, which is in marked contrast to the wild type (cofilin-Cry2-mCh) and high constitutively active (cofilinS3A-Cry2-mCh) analogs.

Initial characterization of optogenetic cofilin construct activity was assessed by whole-cell spreading after whole-cell illumination by measuring cell area during and after multiple 488nm pulses over 10min. Cofilin activation by EGF is known to induce cell spreading (Song et al., 2006). optoCofilin induces both cell spreading and filopodial formation, another phenotype of increased cofilin activity (Lichtner, Wiedemuth, Noeske-Jungblut, & Schirrmacher, 1993), in response to illumination. In contrast, a Cry2-mCh control recruited in the same manner does not generate filopodia (Hughes & Lawrence, 2014).

A protocol for assessing filopodia formation by light activation of optoCofilin is described here:

5.1.1. Equipment and materials

Fluorescent microscopy (widefield) imaging is performed with an inverted Olympus IX81 microscope equipped with a Hamamatsu C848 camera, 60× oil immersion Plan S-Apo objective and FITC and TxRed filter cubes (Semrock).

Metamorph Imaging Suite.

Opaque heat, humidity, and atmosphere (5% CO2) controlled microscope enclosure.

37°C tissue culture incubator with 5% CO2 and 95% humidity.

35mm glass bottom dishes (Mattek).

MEM alpha (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% Pen-Strep.

MEM alpha without phenol red (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% Pen-Strep.

Mammalian expression plasmids: CofilinS3A-Cry2-mCh, CofilinS3A/S120A-Cry2-mCh, Cry2-mCh, LifeAct-Cib-GFP.

MTLn3 cells.

Transfection reagent (Polyplus transfection 114–07).

5.1.2. Protocol

Grow MTLn3 cells to confluency in MEM alpha medium supplemented with 5% FBS and 1% Pen-Strep.

After plating on 35mm MatTek dishes, transfect cells with CofilinS3A/S120A-Cry2-mCh, CofilinS3A-Cry2-mCh (or Cry2-mCh) along with LifeAct-Cib-GFP for initiating the association of optoCofilin to the F-actin cytoskeleton.

Select individual cells for filopodia-forming experiments by assessing their adherence and brightness; Image cells using both the TxRed and FITC channels for each time point (60s over 10min). The exposure time for the TxRed channel should be 300ms, and 100ms for the FITC channel.

Image analysis: Manually count the filopodia at both the beginning and end of each time-lapse image series for each cell using the FITC channel (via the LifeAct-Cib-GFP construct). The fold change in filopodia (10min vs. 0min) should then be quantified for each cell and the net fold change calculated for each individual experimental setup.

5.2. Cellular collapse by the recruitment of optoBax to the outer mitochondrial membrane

optoBax

The Cry2-mCh-BaxS184E (optoBax) construct was expressed in HeLa cells and is retained in the cytoplasm in the dark. Cells transfected with optoBax and Tom20MLS-Cib-GFP (positioned on the outer mitochondrial membrane) are likewise healthy in the dark. However, upon pulsed illumination at 488nm for 1h, optoBax is recruited to the outer mitochondrial membrane, resulting in cellular collapse and subsequent death. By contrast, when Cib is positioned on the plasma membrane (Cib-GFP-CAAX), optoBax recruitment to the membrane has no effect on cell viability (Hughes et al., 2015).

A protocol for the characterization and validation of cellular collapse in HeLa cells transfected with optoBax is described here:

5.2.1. Equipment and materials

Fluorescent microscopy (widefield) imaging is performed with an inverted Olympus IX81 microscope equipped with a Hamamatsu C848 camera, 60× oil immersion Plan S-Apo objective and FITC and TxRed filter cubes (Semrock)

Metamorph Imaging Suite

Opaque heat, humidity, and atmosphere (5% CO2) controlled microscope enclosure

37°C tissue culture incubator with 5% CO2 and 95% humidity

35mm glass bottom dishes (Mattek)

DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% Pen-Strep

DMEM without phenol red (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% Pen-Strep

Mammalian expression plasmids: Cry2-mCh-BaxS184E, Cry2-mCh and Tom20-Cib-GFP

HeLa cells

Transfection reagent (Polyplus transfection 114–07)

5.2.2. Protocol

Grow HeLa cells to confluency in DMEM media supplemented with 5% FBS and 1% Pen-Strep

Plate cells in 35mm MatTek dishes as described followed by transfection with Cry2-mCh-BaxS184E, Cry2-mCh and Tom20-Cib-GFP for initiating the association of optoBax to outer mitochondrial membrane.

Select individual cells for cellular collapse experiments by assessing their adherence and brightness; Image cells using both the TxRed and FITC channels for each time point (every 120 s for the duration of the experiment, typically an average of 60min). The exposure time for the TxRed channel should be between 100 to 300ms, and FITC channel should be kept at a minimum (10ms) to reduce light induced toxicity.

For image analysis, the loss of adherent cell morphology and the appearance of membrane blebbing can be used as direct indicators of cell collapse. Time-lapse images should be collected for each individual cell in each field of view followed by processing using ImageJ. A timestamp is appended to each image series and thereby manually viewed over an appropriate image interval to inspect the loss of adherent morphology and/or membrane blebbing.

5.3. Phosphorylation of mitochondrial PKA reporter by optoPKA

optoPKA

We evaluated the behavior of three different PKA C subunit mutants: CW196R/E203A, C W196R/Y204A, and C W196R/F327A, which were inserted into the construct of the general form Cry2-mCh-Cmutant (optoPKA). Desired optoPKA properties include low kinase activity in the dark, observable kinase activity upon exposure to 470nm light, and inhibition by known PKA inhibitors. MVD7 cells were simultaneously transfected with one of the three optoPKA constructs and a Cib construct targeted to the outer mitochondrial membrane (Tom20MLS-Cib). Cells were also transfected with a PKA reporter described in O’banion et al. (2018). The levels of mitochondrial PKA reporter phosphorylation were compared for cells in the dark, illuminated (470nm) for 1min, or illuminated in the presence of the PKA inhibitor H89. We found Cry2-mCh-CW196R/Y204A displays robust kinase activity (reporter phosphorylation) upon exposure to 1min of 470nm light and insignificant kinase activity in the dark. Furthermore, the presence of H89 interferes with light-triggered kinase activity (O’banion et al., 2018).

5.3.1. Equipment and materials

Fluorescent microscopy (widefield) imaging was performed with an inverted Olympus IX81 microscope equipped with a Hamamatsu C848 camera, 60× oil immersion Plan S-Apo objective and CFP, TxRed, and Cy5.5 filter cubes (Semrock)

Blue LED light source (470nm, Home Depot PAR38 Blue LED Flood Lamp Model #469072)

37°C tissue culture incubator with 5% CO2 and 95% humidity

DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% Pen-Strep, 50 UI recombinant mouse interferon-γ, and 2mM Glutamax

Optimem (Gibco)

DPBS with calcium and magnesium (Gibco)

Trypsin-EDTA (0.05%) (Gibco)

MatTek 12-well glass bottom plates or 35mm # 1.5 glass bottom dishes

Mammalian expression plasmids: Cry2-mCh, Cry2-mCh-CW196R, Cry2-mCh-CW196R/Y204A, Cry2-mCh-CW196R/F327A, Cry2-mCh-CW196R/E203A, OMM-Cib, and mitochondrial PKA-reporter

JetPrime transfection reagent (PolyPlus transfection 114–07)

Mouse anti-phosphoVASPS157 antibody (abcam ab58555)

Anti-mouse Alexa 647 antibody (Life Technologies)

MVD7 cells (gift from Dr. James E. Bear, double knockout VASP and Mena embryonic mouse fibroblast clonal cells with no detectable expression of the EVL protein)

Forskolin (Sigma; 10mM stock solution in DMSO)

H-89 (Sigma; 10mM stock solution in DMSO)

5.3.2. Protocol

Grow MVD7 cells to confluency in DMEM media supplemented with 5% FBS and 1% Pen-Strep

Plate cells in 35mm MatTek dishes as described, followed by transfection with the plasmids containing optoPKA, Tom20MLS-Cib, and mitochondrial PKA reporter at a ratio of 2:1:1 with a total of 2μg DNA per well using jetPrime transfection reagent (Polyplus Transfection).

The following day, exchange media for 1mLL-15/10% FBS/1 × GlutaMAX/50 UI interferon γ without phenol red. L-15 is phosphate and amino acid buffered and is to be used without CO2. If a CO2 incubator is to be used, then bicarbonate buffered media without phenol red is required.

Pre-treat positive control cells with 100 μM forskolin, an cAMP generator, for 30min. Equilibrate cells expressing optoPKA mutants, Tom20MLS-Cib (lacking GFP) and mitochondrial PKA reporter for 10min at RT. They are either to be left in the dark, exposed to 1min blue light (470nm) or exposed to blue light in the presence of 10 μM PKA inhibitor H89.

Cells treated with H89 should be preequilibrated with inhibitor for 10min at RT before light exposure.

Post-light treatment, fix cells by adding 1mL of 2× paraformaldehyde (8% v/v) in PBS yielding a final concentration of 4% paraformaldehyde; incubate for 10min at RT before washing twice with PBS.

Block fixed cells with PBS containing 5% BSA+0.1% Triton X-100 for 1h at RT.

Incubate blocked cells with primary antibody (1:100 dilution of mouse anti-phosphoVASPS157 in PBS with 1% BSA+0.1% Triton X-100) overnight at 4°C.

The following day, wash cells three times with PBS for 5min each and then incubate with secondary antibody (1:1000 anti-mouse Alexa fluor 647) in blocking buffer at RT for 2h.

Repeat wash steps with PBS three times for 5min each before imaging.

Three channels are used for imaging on the widefield microscope: CFP (cyan fluorescent protein; total mitochondrial PKA reporter), TxRed (mCh), and Cy5.5 (phosphorylated mitochondrial PKA reporter via immunostaining with anti phospho-VASPS157 and detecting with anti-mouse Alexa fluor 647)

At least 10 frames containing one or more cells per frame should be captured. Analyze cells that express both mCh and CFP fluorescence.

Draw ROIs around CFP fluorescence and calculate mean and minimum fluorescent intensity for both CFP and Alexa fluor 647.

Use the minimum fluorescent intensity as background signal and subtract from respective channels.

The ratio of phosphorylated reporter/total reporter can be determined by dividing background corrected Alexa fluor 647 mean fluorescent intensity by CFP mean fluorescent intensity. Data can be presented as a percentage of forskolin treated positive control.

6. Summary

We’ve described the process of developing an optogenetic POI using a concentration jump approach in conjunction with the Cry2-Cib system. Three optogenetic POIs across three protein families have been developed: optoCofilin, an actin remodeler, optoBax, an apoptosis inducer, and optoPKA, a protein kinase. These optogenetic species are functionally silent in the dark but can be recruited upon illumination to specific intracellular sites where they are functionally active. Mutants of the POI are generated cytoplasmically disseminated low activity analogs of the wild type protein. These mutants are fused to a photoreceptor (Cry2), and along with the photoreceptor’s binding partner (Cib), the constructs are expressed in cells. Although our work has, to this point, primarily utilized the Cry2-Cib photodimerizing pair, we anticipate that the concentration jump approach may be applied to other photodimerizing systems such as iLid.

Acknowledgments

Eshelman Institute for Innovation at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (R1040 RX03712116) and the National Institutes of Health (1R21NS093617, 1R01NS103486, 1U01CA207160).

Abbreviations

- C

PKA catalytic subunit

- CFP

cyan fluorescent protein

- Cib

cryptochrome-interacting basic helix-loop-helix protein

- Cry2

cryptochrome 2 photolyase homology region

- FAD

flavin adenine dinucleotide

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- FMN

flavin mononucleotide

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- LOV

light, oxygen, voltage domain

- mCh

mCherry

- PKA

cAMP dependent protein kinase

- POI

protein of interest

- R

PKA regulatory subunit

- ROI

region of interest

- TxRed

Texas red

References

- Gibson RM, & Taylor SS (1997). Dissecting the cooperative reassociation of the regulatory and catalytic subunits of camp-dependent protein kinase. Role of Trp-196 in the catalytic subunit. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 272(51), 31998–32005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes RM, Freeman DJ, Lamb KN, Pollet RM, Smith WJ, & Lawrence DS (2015). Optogenetic apoptosis: Light-triggered cell death. Angewandte Chemie (International Ed. in English), 54(41), 12064–12068. 10.1002/Anie.201506346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes RM, & Lawrence DS (2014). Optogenetic engineering: Light-directed cell motility. Angewandte Chemie (International Ed. in English), 53(41), 10904–10907. 10.1002/Anie.201404198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy MJ, Hughes RM, Peteya LA, Schwartz JW, Ehlers MD, & Tucker CL (2010). Rapid blue-light-mediated induction of protein interactions in living cells. Nature Methods, 7(12), 973–975. 10.1038/Nmeth.1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtner RB, Wiedemuth M, Noeske-Jungblut C, & Schirrmacher V (1993). Rapid effects of EGF on cytoskeletal structures and adhesive properties of highly metastatic rat mammary adenocarcinoma cells. Clinical & Experimental Metastasis, 11(1), 113–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriyama K, & Yahara I (2002). The actin-severing activity of cofilin is exerted by the interplay of three distinct sites on cofilin and essential for cell viability. Biochemical Journal, 365(1), 147–155. 10.1042/Bj20020231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nechushtan A, Smith CL, Hsu YT, & Youle RJ (1999). Conformation of the Bax C-terminus regulates subcellular location and cell death. The EMBO Journal, 18(9), 2330–2341. 10.1093/Emboj/18.9.2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’banion CP, & Lawrence DS (2018). Optogenetics: A primer for chemists. Chembiochem, 19(12), 1201–1216. 10.1002/Cbic.201800013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’banion CP, Priestman MA, Hughes RM, Herring LE, Capuzzi SJ, & Lawrence DS (2018). Design and profiling of a subcellular targeted optogenetic CAMP-dependent protein kinase. Cell Chemical Biology, 25(1). 10.1016/J.Chembiol.2017.09.011. 100–109.e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedl J, Crevenna AH, Kessenbrock K, Yu JH, Neukirchen D, Bista M, et al. (2008). Lifeact: A versatile marker to visualize F-actin. Nature Methods, 5(7), 605–607. 10.1038/Nmeth.1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X, Chen X, Yamaguchi H, Mouneimne G, Condeelis JS, & Eddy RJ (2006). Initiation of cofilin activity in response to EGF is uncoupled from cofilin phosphorylation and dephosphorylation in carcinoma cells. Journal of Cell Science, 119(Pt. 14), 2871–2881. 10.1242/Jcs.03017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]