Mitochondria in cardiac myocytes are densely packed to form a cell-wide network of communicating organelles that accounts for about 35% of the myocyte’s volume [1]. The lattice-like arrangement of mitochondria, mostly in long and dense rows parallel to the cardiac myocyte myofilaments, has the structural features of a highly ordered network [2]. This specific mitochondrial network architecture ensures that the large demand of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) of cardiac myocytes is met and appropriately distributed. Mitochondria synthesize approximately 30 kg of ATP each day to both provide energy for the basic cellular metabolism and to secure basic physiological functions of the cardiovascular system such as the maintenance of pulmonary and systemic blood pressure during heart contractions [3]. Their intracellular position is closely associated with the sarcoplasmic reticulum and the myofilaments to facilitate cellular distribution of ATP [4]. However, the role of mitochondrial structure and function is not only limited to ATP generation; mitochondria participate in and control numerous metabolic pathways and signaling cascades such as the calcium signaling, redox oxidation, β-oxidation of fatty acids, oxidative phosphorylation, the synthesis of aminoacids, heme and steroids, and cellular apoptosis [5]. Their structural and functional diversity thus surpasses any other cellular organelle.

Specifically, the control of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation is dependent on the arrangement, interplay and interdependence of mitochondrial ion channels, transporters, and pumps that are located in an inner membrane that is selectively permeable to enable the adjustment of mitochondrial volume, inner membrane potential ΔΨm and mitochondrial redox potential [6]. Thus, the mitochondrial membranes facilitate and balance cellular energy supply and demand.

The Mitochondrial Network in Cardiac Myocytes

Mitochondrial Inner Membrane Oscillations

When subjected to critical amounts of oxidative stress or substrate deprivation, the mitochondrial network in cardiac myocytes may pathophysiologically transition into a state where the inner membrane potential ΔΨm of a large amount of mitochondria depolarizes and oscillates [6–9]. Oscillations of individual mitochondria in intact myocytes were first documented in the early 1980s when Berns et al. excited quiescent cardiac myocytes with a focal laser beam to induce transient cycles of alternating ΔΨm depolarization and repolarization [10]. Mitochondrial inner membrane depolarizations were also detected in smooth muscle cells [11], cultured neurons [12], and in isolated mitochondria [13]. A functional link between metabolic oscillations and cardiac function was demonstrated when O’Rourke et al. [14] showed that cyclical activation of ATP-sensitive potassium currents in guinea pig cardiac myocytes under substrate deprivation was associated with low frequency oscillations in the myocyte’s action potential duration and excitation-contraction coupling. These oscillations were accompanied by a synchronous oxidation and reduction of the intra-cellular nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) concentration.

While it was initially believed that this mechanism was due to changes in glucose metabolism, subsequent studies detected an association of the oscillations with redox transients of mitochondrial flavoprotein and waves of mitochondrial ΔΨm depolarization [15], therefore implying a mitochondrial origin of the phenomenon. Network-wide mitochondrial membrane potential oscillations could be initiated reliably by the application of a localized laser-flash that induced a depolarization of ΔΨm in just a few mitochondria [16]. The association of ΔΨm oscillations with reactive oxygen species (ROS) was discovered by Zorov and Sollot who showed that a localized laser-flash produced a high number of free radicals in cardiac mitochondria in an autocatalytic manner, concomitant with depolarization, referred to as ROS-induced ROS release [17, 18]. Experimentally, synchronous ΔΨm oscillations were observed in small contiguous mitochondrial clusters as well as in large clusters that span the whole myocyte [16], or as mitochondrial ΔΨm depolarization waves that could pass between neighboring cardiac myocytes through intercalated discs [15]. Mitochondrial communication may also be facilitated through the formation of intermitochondrial junctions [19], which could facilitate wave propagation.

Generally, mitochondrial network coordination is heavily influenced by the intricate balance of ROS generation and ROS scavenging within the myocyte: when a critical amount of network mitochondria exhibits a destabilized inner membrane potential, the increased presence of ROS can lead the network into a state of ROS-induced ROS release [16, 20]. It is likely that the antioxidant flux is lowered to a point at which ROS production cannot be scavenged fast enough – this causes a flux mismatch that rapidly goes out of control such that multiple mitochondria form a myocyte-wide cluster of synchronously oscillating mitochondria, also called spanning cluster; these mitochondria lock into an oscillatory mode with low frequencies and high amplitudes [6, 8, 20].

The cardiac mitochondrial network can also behave in an oscillatory mode in the absence of metabolic or oxidative stress. A computational model of the mitochondrial oscillator has predicted mitochondrial behavior that was characterized by low-amplitude, high-frequency oscillations [21], which was later demonstrated experimentally [8]. Since, the collective mitochondrial behavior happened (i) in the absence of metabolic/oxidative stress, (ii) did not involve collapse or large excursions of the membrane potential (i.e., microvolts to a few millivolts), and (iii) could be clearly distinguished from the high-amplitude, low-frequency oscillations involving strongly coupled mitochondria through elevated ROS levels, this regimen was dubbed “physiological” [6, 8]. The transition between normal and pathological behavior in mitochondrial function can be determined by the abundance and interplay between cytoplasmic (Cu, Zn SOD) and matrix (Mn SOD) superoxide dismutases with ROS generation in the respiratory chain, as recently demonstrated [22].

In intact cardiac myocytes, ROS generation from mitochondrial respiration mainly originates in complex III and complex I, and is favored by highly reduced redox potentials and high ΔΨm, typically corresponding to either inhibition or low respiratory flux [6, 16]. The occurrence of ΔΨm limit-cycle oscillations could be suppressed by adding inhibitors of mitochondrial respiration or ligands of the mitochondrial benzodiazepine receptor, but not adding inhibitors of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) [23]. This class of ΔΨm oscillations was consistent with a ROS-induced ROS release mechanism involving the activation of mitochondrial inner membrane anion channels (IMAC), see also below and [6, 16, 24].

Mitochondrial Morphology, Dynamics and Morphodynamics

Changes in the morphology of mitochondria or their dynamic characteristics can influence their collective behavior. In cardiac myocytes, mitochondria can be peri-nuclear, intermyofibrilar and subsarcolemmal, and possess different morphologies as well as proteomic and physiological status [25–29]. This (static) morphological heterogeneity is associated with different mitochondrial functions [30, 31]; for instance, mitochondria in intermyofibrillar locations show a reduced content of flavoproteins compared to those beneath the sarcolemma, thus resulting in different oxidative capacities for NADH- and FADH-generating substrates [30, 32].

The role of dynamic heterogeneity becomes important for pertubations of the mitochondrial network during oxidative or metabolic stress: the mitochondrial network’s response to stress can affect not only intracellularly clustered mitochondria, but scale to the majority of cellular mitochondria and even to the whole-organ level, thus leading to emergent phenomena, such as ventricular arrhythmias [20, 33–35]. In many non-cardiac myocytes, mitochondrial mobility and morphological plasticity or morphodynamics is affected by proteins that facilitate fusion and fission processes, by cytoskeletal proteins (through disruptive structural changes of the cytoskeleton) [36], and changes in myocyte energy metabolism or calcium homeostasis [37, 38]. Recently, it was shown that redox signaling also occurs in clusters of morphologically changing axonal mitochondria, suggesting a morphological and functional inter-mitochondrial coupling in neurons [39, 40]. However, apart from “pre-fusion” events at inter-mitochondrial junctions [19], fusion and fission events as well as mitochondrial mobility have not been observed in adult cardiac myocytes so far, although mitochondrial fusion has been observed in skeletal muscle [41]. However, there is growing evidence from mitochondrial protein gene studies that mitochondrial morphodynamics may play a role in the maintenance of mitochondrial fitness [42].

Spatio-Temporal Behavior of Individual Mitochondrial Oscillators

While many studies have investigated the response of the whole mitochondrial network in external stress stimuli (i.e. ischemia-reperfusion injury or oxidative stress) at the inner mitochondrial membrane [8, 16], more recent ones have focused on the role of individual mitochondria and their spatio-temporal behavior [9, 35, 40, 43, 44].

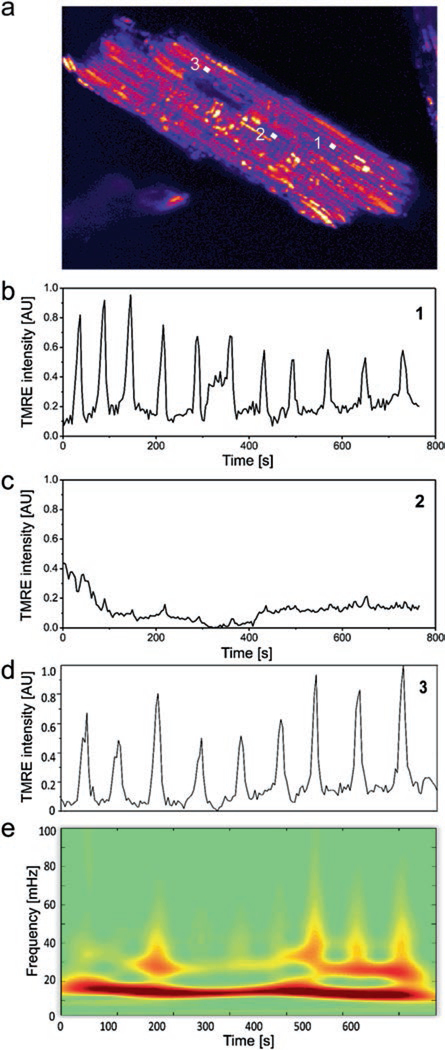

Alterations of the mitochondrial membrane potential ΔΨm can be monitored with the positively charged lipophilic fluorescent dyes tetramethylrhodamine methyl or ethyl ester (TMRM or TMRE), that redistribute from the matrix to the cytoplasm with a depolarization of ΔΨm [45] (see Fig. 1.1). Myocyte-wide ΔΨm oscillations can then be triggered by a perturbation of the mitochondrial network through thiol-oxidizing substances such as diamide, or by a highly localized laser flash [16, 46]: the ensuing sequence of locally confined ROS generation and induced autocatalytic ROS release [16, 17, 47] can lead to a critical accumulation of ROS that initiates a propagating wave of ΔΨm depolarization [7]. However, the reaction of each individual mitochondrion within the myocyte is highly variable: while a majority of mitochondria synchronize to cell-wide ΔΨm oscillations, some mitochondria do not participate whereas others participate only temporarily (see Fig. 1.1b–d) [9, 43]. This diversified mitochondrial behavior (in frequency and amplitude) is directly associated with the scavenging capacity of intracellular ROS on a local level within the myocyte, as well as the inner membrane efflux of superoxide ions.

Fig. 1.1.

Dynamic mitochondrial oscillations and wavelet transform analysis. (a) Densely packed mitochondria in an adult cardiac myocyte, monitored with the fluorescence dye TMRE. (b–d) Perturbations of the mitochondrial network can result in oscillatory patterns of individual mitochondria that differ in occurrence and frequency content. (e) Dynamic frequency content of oscillating mitochondria can be analyzed with the absolute wavelet transform: the major frequency component of mitochondrion 3 (d) varies between 15 and 20 mHz (Reprinted with permission from Ref. [81]. Copyright 2014)

A large cluster of mitochondria with synchronized ΔΨm oscillations can recruit additional mitochondria in analogy to a network of weakly coupled oscillators (see below), whereas some mitochondria may exit the cluster, i.e. show ΔΨm oscillations that are not synchronized with the cluster, because their local ROS defense mechanisms are exhausted [9, 43]. Thus, this complex interplay of ROS generation and scavenging determines the individual mitochondrial frequency and amplitude.

Since the frequencies of these oscillations change in time, they are best described by methodologies that do not assume an a priori stationarity of ΔΨm signals, such as wavelet transform analysis. Unlike standard methods of statistical analysis, that can only be applied if the nonstationarity of the signals is associated with the low-frequency part of the observed power spectrum, wavelet analysis allows analyzing the full range of frequencies of the nonstationary mitochondrial network. The wavelet analysis provides a time-resolved picture of the frequency content of each mitochondrial signal, see Fig. 1.1e. Earlier methodologies, e.g. relative dispersion analysis or power spectral analysis, although they provided a glimpse of the functional mitochondrial network properties such as the long-term memory of mitochondrial oscillatory dynamics [7], probed the average behavior of the whole myocyte (single signal trace) [8], without discriminating individual mitochondria. Therefore, application of wavelet analysis on individual mitochondria to characterize the dynamic behavior of the mitochondrial network across the myocyte, was a significant step forward in the systematic analysis of the whole population of mitochondrial oscillators, accounting for both their frequency dynamics and spatio-temporal correlations [9, 43].

Mitochondrial Clusters with Similar Oscillatory Dynamics

It has been shown that mitochondria whose signals are highly correlated during a specific time range, i.e. mitochondria with a similar frequency content, could be grouped into different clusters [9]. Then, the largest cluster of similarly oscillating mitochondria forms a highly correlated and coherent ΔΨm signal that drives the cell-wide oscillations which are observed during the recording. These major clusters do not necessarily contain mitochondria that demonstrate strong spatial contiguity (albeit the data is showing only a cross section of the network, therefore synchronized clusters that are “non-contiguous” could be connected as a 3D structure through other planes), nor do they have to coincide with local ROS levels as in the case of a “spanning cluster” as proposed in [8]. In fact, the spatial contiguity of major clusters is substrate dependent (such as glucose, pyruvate, lactate and β-hydroxybutyrate) through their influence on the cellular redox potential [35].

The size of mitochondrial clusters is related to the cluster frequency and phase: mitochondria within the cluster adjust their frequencies and phases to a common one, while large clusters comprising many (coupled) mitochondria need a longer time to synchronize [48, 49]. Similarly, clusters with large separation distances among their components or a low contiguity, take longer to synchronize compared to clusters with smaller separation distances among their components. In both cases, the common cluster frequency remains low and is characterized by an inverse relation between common cluster frequency and cluster size [9, 35].

For cardiac myocytes superfused with glucose, pyruvate, lactate or β-hydroxybutyrate, local laser-flashing still leads to synchronized cell-wide oscillations of mitochondrial clusters. However, the network’s adaptation to the specific metabolic conditions leads to differences in mitochondrial cluster synchronization and dynamics. These differences can be attributed to the altered cardiac myocyte catabolism and ROS/redox balance [35]. For substrates such as pyruvate and β-hydroxybutyrate that generally lead to strongly reduced redox potential (in comparison with glucose or lactate), the rate of change of cluster size versus averaged cluster frequency is higher than for perfusion with glucose or lactate, see Fig. 4 in [35]; yet, typical cluster frequencies for β-hydroxybutyrate were found in a much smaller range (5–20 mHz) than those for pyruvate (10–70 mHz) [35]. A large range of mitochondrial frequencies is a strong indicator of desynchronization processes that are based on dynamic heterogeneity. Likewise, an increased dispersion in cluster size, as observed for perfusion with pyruvate and β-hydroxybutyrate, is a signature of an increasingly fragmented mitochondrial network with several smaller clusters of similar size that have different frequencies. In contrast, a low mitochondrial frequency dispersion is an indicator of a rapid increase in the formation of mitochondrial network clusters during ROS-induced ROS release, such that an increasingly rapid recruitment of mitochondrial oscillators would result in a decrease of clusters with different frequencies. Since in a pathophysiological state, a slow growth in cluster size after the rapid onset of a synchronized cell-wide cluster oscillation is a sign of exhausted ROS scavenging capacity (reflected by a decrease of ΔΨm amplitude), quantification of cluster synchronization and contiguity properties provide important information about the myocyte’s propensity to death [9]. These findings help provide a better understanding of the altered cellular metabolism observed in diabetic cardiomyopathy or heart failure, where the myocyte’s response to the switch in substrate utilization, e.g. through an increased utilization of glucose, can be protective or maladaptive [49–51].

Apart from isolated cardiac myocytes, such a relation could also be observed in mitochondria in intact hearts preparations, where neighboring cardiac myocytes are linked electrically and chemically via gap junctions [35, 52]. In those experiments, mitochondrial populations of several myocytes show cell-wide ΔΨm signal oscillations following a laser flash, similar to those observed in isolated or pairs of cardiac myocytes [15, 52]. Such behavior could also be observed in rat salivary glands in vivo [53]. Generally, mitochondrial oscillations in intact tissue are faster than in isolated myocytes with an approximate frequency range of 10–80 mHz in cardiac tissue and 50–200 mHz in salivary glands [35, 53], and their frequency is not as strongly influenced by the size of the cluster as in isolated myocytes [35].

The Mitochondrial Network as a Network of Coupled Oscillators

The intricate spatio-temporal dynamics of mitochondrial networks results from many forms of inter-mitochondrial interactions that involve several metabolic pathways. Such pathways include the modification of gene expression, electrochemical interactions that are mediated by ROS through ROS-induced ROS release, other (e.g. exogenous) forms of control exerted on the local redox environment [54], and morphological changes in neighboring mitochondria [19]. In general terms, signaling or communication between (intra-cellular) organelles modulates the relation between cellular networks that involve the transformation (generation) of mass (energy), as represented by the metabolome, and those networks that carry information as represented by the proteome, genome, and transcriptome. A unique pheno-typical signature of a myocyte is then given by the fluxome which represents the network of all cellular reaction-fluxes: it interacts with all other networks and provides a description of the dynamic content of all cellular processes [55]. Emergent properties of the cardiac mitochondrial network, i.e. properties that cannot be derived from the simple sum of behavior of the network’s individual components represent a distinguishing trait of biological complexity and provide the opportunity to study the dynamical coordination of functional intra-cellular relations.

Emergent Properties of the Mitochondrial Network: Mitochondrial Criticality

Biological networks exhibit mostly scale-free dynamics and topologies: the structure of the network is represented by several network hubs, i.e. nodes with a large number of links to other nodes, and a large number of nodes with low connectivity [56]. Analysis of emergent properties of these networks, e.g. large-scale responses to external or internal stimuli (perturbations), synchronization, general collective behavior, vulnerability to damage and ability to self-repair, has been the subject of intensive research endeavors [57–59]. In those studies, the scale-free character of the networks is revealed by the presence of network constituents with different frequencies on highly dependent temporal scales [60]. However, as pointed out by Rosenfeld et al. [61], the network’s robustness to perturbations and modularity cannot be determined using a reductionist approach from knowledge of all elementary biochemical reactions at play, but instead requires network conceptualizations known from systems biology.

In the cardiac network of mitochondrial oscillators, the synchronized, myocyte-wide, low-frequency, high-amplitude depolarizations of ΔΨm represent an emerging self-organized spatio-temporal process in response to a perturbation of individual mitochondrial oscillators that are weakly or strongly coupled in the physiological or pathophysiological state, respectively [8, 62–64]. The oscillation period of an individual mitochondrial oscillator is therefore not static but can be modulated by long-term temporal correlations within the mitochondrial network [8, 21]. Such synchronization processes in the form of biochemical rhythms, as observed in many systems of chemically, physically or chemico-physically coupled oscillators, serve the purpose of generating and sustaining spatio-temporal organization through numerous regulatory mechanisms: the resulting dynamically changing oscillations are used by cardiac myocytes to achieve and control internal organization [62–65]. During oxidative or metabolic stress, the mitochondrial network’s response can affect not only intracellularly clustered mitochondria, but scale-up to affect the majority of cellular mitochondria and even the whole-organ, thus leading to myocardial malfunction, and ultimately to ventricular arrhythmias [24, 33, 34]. For example, during reperfusion following ischemic injury, cardiac myocytes become oxidatively stressed due to substrate deprivation (e.g., oxygen, glucose), leading to mitochondrial membrane potential collapse at the onset of oscillations [16, 46], transient inexcitability [16] and, eventually, ventricular fibrillation [24, 34, 66]. Experimental measures to prevent these effects include the application of the mBzR antagonist 4′-chlorodiazepam that modulates IMAC activity [34]. The prominent role of IMAC opening in ROS-induced ROS release and ΔΨm depolarization was further supported by blocking mPTP via cyclosporin A, which had no effect on ensuing post-ischemic arrhythmias [24, 34] (see also below and Fig. 1.2).

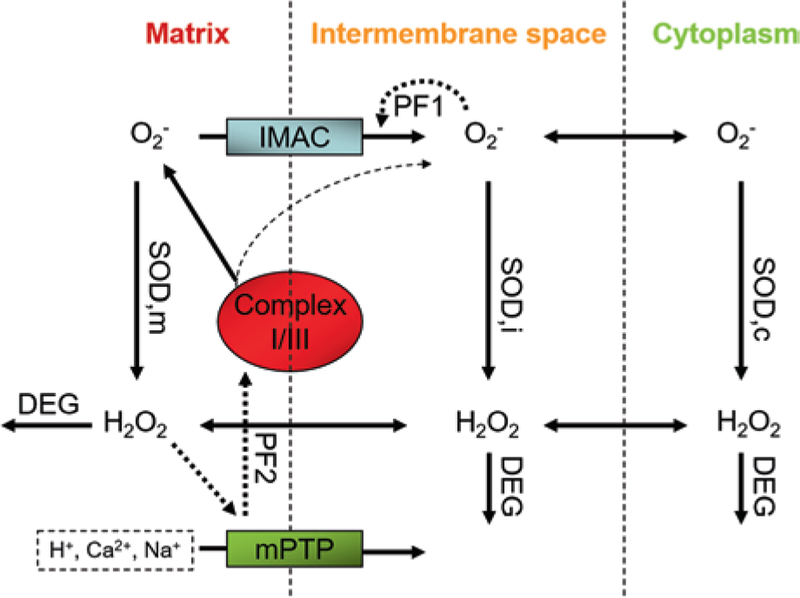

Fig. 1.2.

Schematic description of mitochondrial ROS-induced ROS release. The mitochondrial respiration complexes I and III produce superoxide anions (O2−) and release them in the mitochondrial matrix. The anions can then reach the intermembrane space (IS) through IMAC, although small quantities directly exit complex III (dashed arrow that originates from complex III). Superoxide dismutases (SOD) in matrix, IS and cytoplasm convert superoxide anions into hydrogen peroxide that can diffuse freely between all compartments. Its degradation is effected by peroxidases (DEG). One positive feedback loop (PF1) is initiated by the activation of IMAC through superoxide anions in the IS to eventually depolarize the mitochondrial inner membrane potential [16, 21]. The resulting stimulation of SODs can, if passing a critical threshold, deactivate IMAC to allow electron transport and repolarization of the membrane potential. Byproducts of hydrogen peroxide-initiated redox processes can trigger mPTP opening (e.g. oxidized lipids or hydroxyl radicals), thus leading to (temporarily) increased production of superoxide anions in the respiratory chain to further open mPTPs in a positive feedback loop (PF2). (This diagram has been adapted from its original version in Yang et al. [71]).

As was previously demonstrated [9, 20], synchronization of mitochondrial oscillations can be achieved by a critical amount of spontaneously synchronized oscillators, a concept termed ‘mitochondrial criticality’ [7, 20]: a number of synchronously oscillating mitochondria recruits more mitochondria to eventually lead the majority of network mitochondria into myocyte-wide synchronized ΔΨm oscillations. A transition of this critical threshold into a state of collective, synchronized mitochondrial behavior is equivalent to that of a phase transition between states of matter in thermodynamics. However, in the mitochondrial network it describes a transition from a physiological state into a pathophysiological state. Such transitions among large populations of locally connected mitochondria can be described with the percolation theory which takes into consideration the long-range connectivity of (random) systems and employs a probabilistic model to assess the collective dynamics of the inter-connected network of mitochondria [67]. For ideal lattice-like networks, which is a convenient description of the dense, quasi-uniform and spatially arranged cardiac mitochondria, the theoretical percolation threshold can be identified as pc = 0.59; this threshold is close to experimentally obtained values of mitochondrial criticality where a transition into myocyte-wide ΔΨm oscillations was observed in about 60% of all mitochondria within the mitochondrial network with significantly increased ROS levels [20]. For mitochondria in close vicinity to the percolation threshold, small perturbations can thus provoke a transition into global limit cycle oscillations.

Stochasticity and Mitochondrial Network Modeling

Computational models may help obtain a deeper understanding of the intricate interdependencies of mitochondrial networks that lead to emergent behavior. Today, there are several computational models that describe mitochondrial network dynamics, see e.g. [68] for a detailed review.

A mathematical model that has employed ordinary differential equations to represent matrix concentration time rates of ADP, NADH, calcium, Krebs cycle intermediates and ΔΨm has been recently reported by Cortassa et al. [69]. In this model, the role of IMAC opening in ROS-induced ROS release and ROS diffusion dynamics were incorporated to correctly reproduce mitochondrial respiration, calcium dynamics, bioenergetics, and the generation of ΔΨm limit cycle oscillations [21]. The model provided evidence for the existence of synchronized clusters of mitochondria that entrain more mitochondria to participate in synchronous ΔΨm oscillations [47]. Other models have been developed based on the hypothesis of mPTP-mediated ROS-induced ROS release [18, 70] or a combination of mPTP- and IMAC-mediated ROS-induced ROS release [71] (see also Fig. 1.2 for physiological details). Another probabilistic, agent-based model has considered the switch of superoxide anions to hydrogen peroxide, to model ROS signaling for increasingly distant neighboring mitochondria, thus facilitating the inhibition of ROS-induced ROS release through gluthathione peroxidase 1 in the cytosol [72].

Dynamic tubular reticulum models of mitochondrial networks that involve the modeling of molecular fission and fusion events have been recently proposed [73, 74]. Some use graph-based models of the mitochondrial network with a set of simple rules of network connectivity, see e.g. [75], which predict topological properties of the mitochondrial network. However, this approach does not take into account spatial information about the proximity and positioning of neighboring mitochondria.

Overall, the dynamic response of mitochondrial networks to stimuli is due to the stochastic nature of the underlying processes. These processes can be modeled by the addition of intrinsic noise (that emerges from the stochastic processes at small timescales), into system-defining differential equations [61, 76, 77]. However, although in low-dimensional non-linear systems the introduction of random noise may lead to deterministic chaos [78], in high-dimensional non-linear systems with strong links among their components stochasticity may exhibit synchronized behavior [79], as is the case for cardiac mitochondria.

In this case, criteria for stochasticity of high-dimensional non-linear systems are easily fulfilled for strong links between components [79]. This is especially the case for mitochondria in cardiac myocytes that are morphologically and functionally coupled to reveal complex spatio-temporal dynamics [19, 80, 81], see also below.

Mitochondrial Coupling in a Stochastic Phase Model

Synchronization phenomena in networks of coupled nonlinear oscillators were first studied mathematically a few decades ago by Winfree and Kuramoto [82, 83]. The Kuramoto model assumes a (large) group of identical or nearly identical limit-cycle oscillators that are weakly coupled and whose oscillations are driven by intrinsic natural frequencies which are normally distributed around a mean frequency [84]. It provides an exact solution for the critical strength of coupling that allows a transition into a fully synchronized state [85]. The simplicity of the model and its analytical power have made it a frequently applied model in the context of circadian biology, but also in many other systems that contain biologically, physically or chemically coupled oscillators (reviewed in detail in [84, 85]).

The coupling constant in Kuramoto models is time-independent and identical for every pair of coupled oscillators [84]. In cardiac myocytes, however, the dynamic behavior of mitochondrial oscillating frequencies, as well as the presence of structurally varying areas of mitochondrial density or arrangement within the myocyte suggest a position-dependent and time-varying mitochondrial coupling.

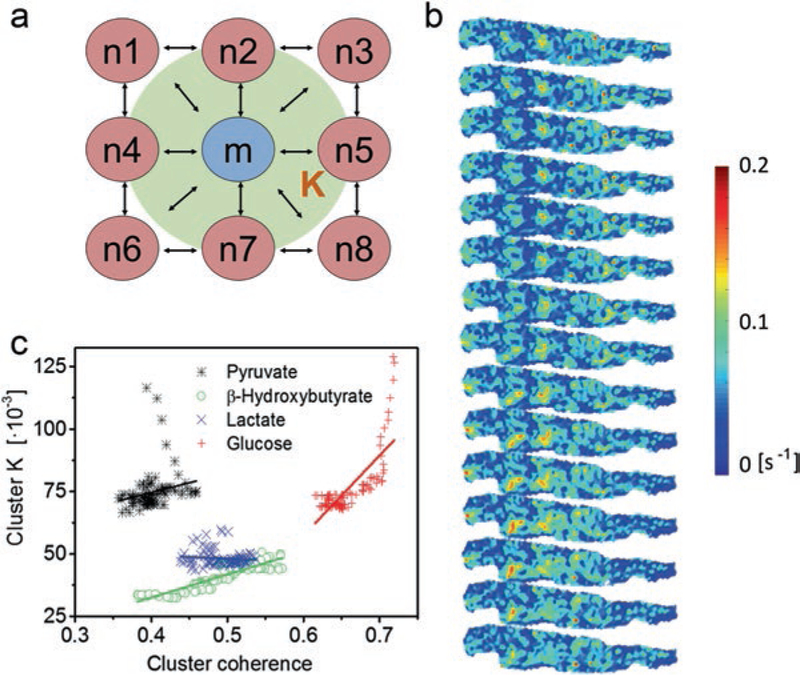

We have recently studied the cardiac inter-mitochondrial coupling by adopting an extended Kuramoto-type model, to determine the time-dependent coupling constants of individual mitochondrial oscillators [35]. In this model, we combined wavelet analysis results with a set of stochastic differential equations that describe drifting frequencies with the intention to develop a minimum-order model that uses only two parameters to characterize inter-mitochondrial coupling: the intrinsic oscillatory frequency and the mitochondrial coupling constant [35]. By mapping and identifying each mitochondrion within the mitochondrial network, the exact nearest neighbors of each mitochondrion were used to describe the spatial variance of mitochondrial coupling, i.e. inter-mitochondrial coupling constants were considered for the local nearest-neighbor environment. The concept of local coupling acknowledges inter-mitochondrial coupling through physical connections, i.e. coupling through diffusion of chemical coupling agents such as ROS and/or forms of inter-mitochondrial communication at inter-mitochondrial junctions [19]. It also emphasizes the role of local ROS scavenging mechanisms that prevent long-range diffusion. Using this approach, we were able to determine the averaged dynamic coupling constant (of local mean field type) of each mitochondrion to all of its nearest neighbors, see Fig. 1.3. Quantitative understanding of local myocardial coupling has important implications in the study of the myocyte’s response to metabolic and oxidative challenges during its transition to a pathophysiological state.

Fig. 1.3.

Dynamic inter-mitochondrial coupling and relation to frequency cluster coherence. (a) Dynamically changing inter-mitochondrial coupling can be described with a stochastic phase model that provides local coupling constants K of mean-field form (green cloud) for each mitochondrion m to its nearest neighbors n. Inter-mitochondrial coupling is mediated by diffusive coupling agents that interact with the inner mitochondrial membrane, see also Fig. 1.2. (b) Maps of coupling constants at different time-points (from top to bottom with time intervals of 17.5 s): strong coupling is indicated in yellow and red colors, weak coupling in green and blue colors. Clustered nests of highly coupled mitochondria indicate synchronously oscillating mitochondria, whereas regions with low coupling may be associated with a local exhaustion of antioxidant defense systems. (c) Coupling constant K versus coherence for mitochondria in a large frequency cluster (details see main text) for cell-superperfusion with different substrates. Generally, cluster coupling increases with coherence, whereby the rate of increase is associated with the size of the cluster (see also Fig. 4 in [35]). Lactate-perfusion is associated with small cluster areas such that cluster coupling is not increasing with cluster coherence. Linear fit curves are shown in their respective substrate color (Reprinted with permission from Ref. [35]. Copyright 2015)

Coupling Dynamics in Mitochondrial Frequency Clusters

Inter-mitochondrial coupling within the cardiac myocyte can be studied by comparing the spatio-temporal distribution of inter-mitochondrial coupling constants of mitochondria that belong to the (largest) mitochondrial cluster with similar frequencies, against those of the remaining (“non-cluster”) mitochondria. Cellular conditions that promote low coupling constant values for the cluster mitochondria versus the remaining oscillating mitochondria (that may also be organized in clusters), indicate similar structural organization principles [35].

By relating the inter-mitochondrial coupling within a cluster with the coherence (a measure of the similarity of the mitochondrial ΔΨm oscillations) of the cluster (Fig. 1.3d), we have shown that larger clusters show stronger cluster coupling constants rendering more coherent cluster oscillations. However, for small cluster areas that occur when a myocyte is superfused with lactate (see also Fig. 4 in [35]), an increase in cluster coherence is not accompanied by an increase in cluster coupling. Such behavior is indicative of a greater influence of spatial rather than temporal coupling on the network of mitochondrial oscillators. During superfusion with pyruvate an early decrease of coupling strength (Fig. 1.3d) can be attributed to a strong drift towards the common cluster frequency of those mitochondria with the initially largest difference from the common cluster frequency. When cluster coherence levels at this point are low, which is likely is for small clusters (as experimentally verified for pyruvate perfusion (Fig. S5 in [35]), mitochondria might rapidly drop in and out of the cluster. In addition, the distribution of mitochondrial oscillator frequencies is narrowed during their rapid recruitment into the major frequency cluster, leaving fewer clusters with different frequencies. In contrast, high frequency distributions and high rates of change of cluster size compared to the common cluster frequency are a sign of desynchronization through dynamic heterogeneity.

In this system, the observed strong drift of oscillatory frequencies relates to the fundamental concept of synchronization within the mitochondrial oscillator network: its mechanism can be explained by the dynamics of local ROS generation and scavenging mechanisms that involve the mitochondrial matrix as well as extramitochondrial compartments [86]. Then, the slow drift of each mitochondrial oscillator towards the actual mitochondrial frequency is in agreement with the notion of diffusion-mediated signaling, with ROS as the primary coupling agent that is locally restricted and mainly dependent on local ROS density changes.

For small areas of structurally dense, phase-coupled mitochondrial oscillators, local ROS concentration is strongly increased through ROS-induced ROS release, thus leading to the recruitment of neighboring mitochondria. Consequently, these growing clusters lose spatial contiguity and, therefore, show a decrease in their common frequency which, in turn, leads to a decrease of the frequency of local ROS release and to declining local ROS levels, especially along the cluster perimeter. This effect naturally decreases inter-mitochondrial coupling. The formation of spanning clusters, however, provides for a slight increase in the overall basal ROS level to coincidentally increase local inter-mitochondrial coupling. Generally, these observations indicate a preference of spatial coupling over temporal coupling that affect synchronized mitochondrial oscillator networks: early cluster formation mainly drives the correlation between common cluster frequency and local mitochondrial coupling. During this time, the mean cluster coupling constant is large (see Fig. 5 in [15]). Cluster size and local coupling, however, mainly show correlative effects when the cluster of synchronized mitochondrial oscillators involves a majority of the mitochondrial network. At this point, a spanning cluster has already been formed and most mitochondria participate in cell-wide ΔΨm oscillations.

ROS as primary inter-mitochondrial coupling agents and products of mitochondrial respiration take a central role in cell homeostasis and its response to oxidative or metabolic stress. Under physiological conditions, mitochondria minimize their ROS emission as they maximize their respiratory rate and ATP synthesis according to the redox-optimized ROS balance hypothesis [87]. Stress alters this relationship through increased ROS release and a diminished energetic performance [88]. Thereby, the compartmentation of the redox environment within the cellular compartments such as the cytoplasm and mitochondria, is important in the control of ROS dynamics and their target processes [86]. Within physiological limits, increased mitochondrial metabolism resulting in enhanced ROS generation can function as an adaptive mechanism leading to increased antioxidant capacity and stress resistance, according to the concept of (mito)hormesis [89, 90]. Generally speaking, controlled ROS emission may serve as a robust feedback regulatory mechanism of both ROS generation and scavenging [88]. Dysfunctional mitochondria alter their redox state to elicit pathological oxidative stress, which has been implicated in ageing [91, 92], metabolic disorders like diabetes [93], as well as in cardiovascular [34, 94], neoplastic [95], and neurological diseases [40, 96]. Chronic exposure to increased ROS levels can affect excitation-contraction coupling and maladaptive cardiac remodeling that may lead or increase the propensity to cardiac arrhythmias [34, 97, 98].

Mitochondrial Scale-Free Network Topology and Functional Clustering

Self-Similar Dynamics and Fractal Behavior in Mitochondrial Networks

The defining feature of time series signals with scale-free dynamics is the similarity of frequency-amplitude relations on small, intermediate, and large time scales. In a network of coupled oscillators this translates into new links between oscillators that form in higher numbers depending upon the number of already existing links. In scale-free networks, the occurrence of hubs (i.e., nodes with multiple input and output links) increases the probability of new links being formed [99], an effect known as preferential attachment [58] or the “Matthew effect” in the sociological domain [100].

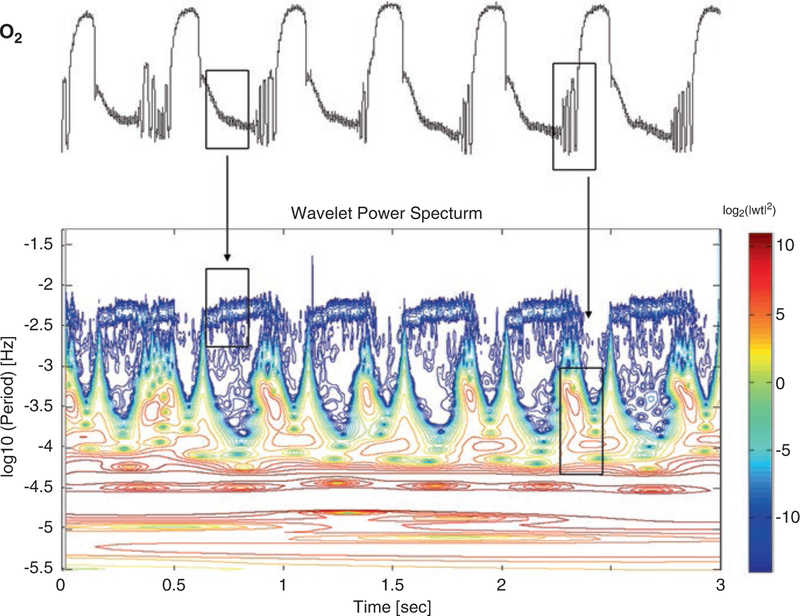

Such fractal or self-similar dynamics develop because of a multiplicative interdependence among these processes and has been observed in cardiac myocytes subjected to oxidative stress [20, 34, 101], in self-organized chemostat yeast culture [62, 102, 103] and in continuous single-layered films of yeast cells exhibiting large-scale synchronized oscillations of NAD(P)H and ΔΨm [62, 104]. Using wavelet analysis, and as predicted by fractal dynamics, one observes an intricate scale-free frequency content with similar features on different time scales (Fig. 1.4) [60].

Fig. 1.4.

Wavelet analysis of the O2 signal time series obtained from the self-organized multioscillatory continuous culture of S. cerevisiae. (a) Relative membrane inlet mass spectrometric signal of O2 versus time for S. cerevisiae. The time scale is not shown, but corresponds to hours after the start of continuous fermentor operation. Large-amplitude oscillations show substantial cycle-to-cycle variability with 13.6 ± 1.3 h (N = 8). Other evident oscillation periods are ~40 min and ~4 min. This figure was provided courtesy of Prof. David Lloyd, affiliated with Cardiff University, United Kingdom. (b) Logarithmic absolute squared wavelet transform over logarithmic frequency and time. At any time, the wavelet transform uncovers the predominant frequencies and reveals a complex and fine dynamic structure that is associated with mitochondrial fractal dynamics. Boxes and arrows show the correspondence between the time series and the wavelet plot

For cardiac mitochondrial networks in the physiological regime, it could be demonstrated that the failure or disruption of a single element beyond a critical threshold can result in a failure of the entire network; such scaling towards higher levels of organization in the mitochondrial network obeys an inverse power law behavior that implies an inherent correlation of cellular processes operating at different timescales [8, 58]. The observation of scale-free dynamics in mitochondrial oscillator networks is in agreement with their representation as weakly coupled oscillators in the physiological domain (in the presence of low ROS levels), and their role as energetic, redox and signaling hubs [105].

Functional Connectivity and Mitochondrial Topological Clustering

Dynamic changes in the network’s topology during synchronized myocyte-wide oscillations in the pathophysiological state reveal important information about functional relations between distant mitochondria displaying similar signal dynamics. These relations cannot be explained alone by local coupling through diffusion or structural connections. As in networks of communicating neurons, the spontaneous occurrence of changes in the clusters’ oscillatory patterns observed at markedly different locations, indicates strong and robust functional correlations; interestingly, the time-scales of these changes are similar in mitochondrial and neuronal networks [106, 107].

Mitochondrial network functionality can be assessed by measuring the functional connectedness between mitochondrial network nodes, i.e. by obtaining a quantitative measure of the functional relations that span the dynamically changing mitochondrial network topology [108].

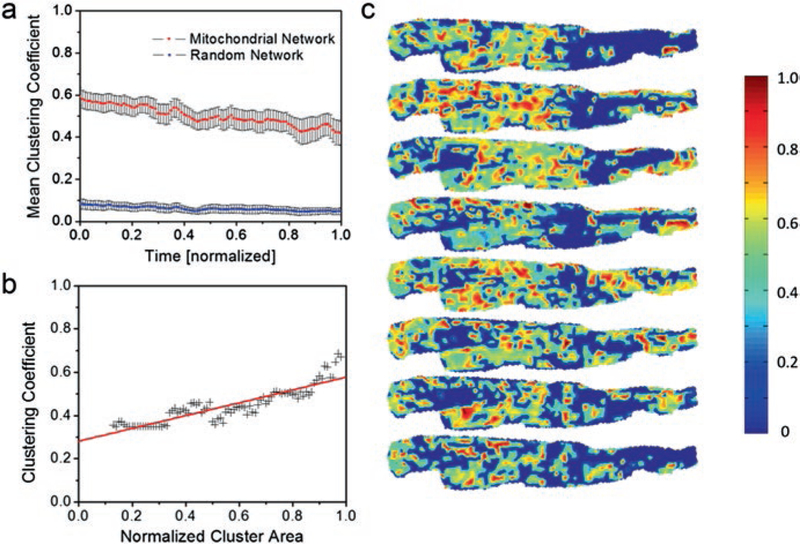

Such a measure of mitochondrial functional connectedness can be the clustering coefficient, similar to that employed by Eguiluz et al. for scale-free functional brain networks [109]. In that case, for a specific network constituent, the clustering coefficient provides a measure of connectedness between neighbors [110]. For instance, clustering plays an important role in neuronal phase synchronization [111]. In the case of mitochondrial networks, dynamic functional clustering significantly differs from random Erdös-Rényi networks [112], even in the presence of similar number of links [81] (Fig. 1.5). This result supports the concept that mitochondrial networks exhibit structural-functional unity [113]. Therefore, dynamic mitochondrial clustering is consistent with its functional properties that are associated with mitochondrial positioning within the network, as previously described [30, 31]. In Fig. 1.5c, the dynamic nature of topological clustering is shown for a glucose-perfused cardiac myocyte during synchronized membrane potential oscillations. While some regions on the left part of the myocyte maintain high clustering, mitochondria on the right side show higher clustering only during the middle portion of the recording, as the spatio-temporal topology evolves.

Fig. 1.5.

Dynamic functional clustering in mitochondrial networks. (a) Comparison of dynamic functional clustering for mitochondrial networks (red line) and random networks (blue line) with the same number of links on the same set of vertices. Mitochondrial networks are scale-free networks whose functional organization is significantly different from random networks. (b) Functional clustering for a large cluster of similarly oscillating mitochondria versus the cluster’s area. Functional clustering is increasing with the number of synchronously oscillating mitochondria. (c) Consecutive maps of distributions of functional clustering coefficients in a cardiac myocyte. Some regions of the cell maintain a high functional clustering during the recording (middle left area of the cell) whereas other regions only temporarily display functional clustering (far right area of the cell) (a and b reprinted with permission from Ref. [81]. Copyright 2014)

To further investigate the mitochondrial network dynamics, future studies will need to identify and quantify functional ensembles of strongly interconnected mitochondria [80, 114]. These studies may shed new light into populations of coexistent subsarcolemmal and intermyofibrillar mitochondria that exhibit different roles in the myocyte (patho)physiology [28, 29, 115].

Concluding Remarks

Biological networks within one cell, organ or organism are not isolated entities but exhibit common nodes. Introducing higher-dimensional node degrees generates multi-layer, interdependent, networks. So far, our understanding of such networks is still in its infancy (see [116, 117] for detailed reviews). For example, within the cardiac mitochondrial network, at least two layers can be distinguished, corresponding to structural connections via inter-mitochondrial junctions, and communication through mechanisms that control local ROS balance [19, 35, 80, 118].

Stressful events can trigger synchronized mitochondrial oscillations in which mitochondria functionally self-recruit in frequency clusters [9, 16, 35, 81]. In functional terms, mitochondria can be seen as alternating between states of excitability and quiescence modulated by ROS signaling, thus modulating myocyte’s function and energy metabolism [119]. In cardiac myocytes under critical situations, e.g. at myocyte-wide ROS accumulation close to the percolation threshold, inter-mitochondrial functional, structural and dynamic coupling can lead to electrical and contractile dysfunction, and ultimately to myocyte death and whole heart dysfunction. Eventually, under criticality conditions, perturbation of a single mitochondrion could propagate to the remaining mitochondria, leading to myocyte death.

A mitochondrion’s gatekeeper role, at the brink of cardiac myocyte death, can only be understood when its function in the mitochondrial network can be predicted either experimentally or through quantitative modeling in which case the mitochondrial parameters are inferred from the available experimental data. Although an increase in computational efficiency has helped modeling make impressive progress in recent years [68], a complete description of the mitochondrial network is still evolving. Stochastic models have been well suited to provide system-wide mitochondrial parameters, such as dynamic coupling constants and functional clustering coefficients in large networks of coupled mitochondrial oscillators.

Synergistic, experimental and computational investigations have unveiled emergent properties of the complex mitochondrial oscillatory networks that describe cluster partitioning of synchronized oscillators with different oscillatory frequencies [120, 121], as well as the chimeric co-existence of synchronized and non-synchronized oscillators [122, 123]. These results coincide with our observations of mitochondrial oscillations in cardiac myocytes, thus supporting the view of network-coupled mitochondrial oscillators. The computational approach promises further discernment of the dynamic spatio-temporal relations within biological networks, while aiding our understanding of its functional implications for cell survival. Therefore, the quantitative description of inter-mitochondrial coupling and functional connectedness provides parameters whose dynamic behavior under pathological conditions may help evaluate the impact of, e.g., metabolic disorders, ischemia-reperfusion injury, heart failure, on mitochondrial networks in cardiac, cancer and neurodegenerative diseases.

To further investigate the mitochondrial network dynamics, future studies will need to identify and quantitate functional ensembles of strongly interconnected mitochondria [80, 114]. These studies may shed new light into populations of coexistent subsarcolemmal and intermyofibrillar mitochondria that exhibit different functional outputs [28, 29, 115].

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid (#15GRNT23070001) from the American Heart Association (AHA) and NIH grant 1 R01 HL135335-01.

Contributor Information

Felix T. Kurz, Department of Neuroradiology, Heidelberg University Hospital, Heidelberg, Germany Massachusetts General Hospital, Cardiovascular Research Center, Harvard Medical School, Charlestown, MA, USA.

Miguel A. Aon, Laboratory of Cardiovascular Science, National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, Baltimore, MD, USA

Brian O’Rourke, Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Antonis A. Armoundas, Massachusetts General Hospital, Cardiovascular Research Center, Harvard Medical School, Charlestown, MA, USA

References

- 1.Page E, McCallister LP. Quantitative electron microscopic description of heart muscle cells; application to normal, hypertrophied and thyroxin-stimulated hearts. Am J Cardiol. 1973;31:172–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Covian R, Balaban RS. Cardiac mitochondrial matrix and respiratory complex protein phosphorylation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;303:H940–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrari R, Censi S, Mastrorilli F, Boraso A. Prognostic benefits of heart rate reduction in cardiovascular disease. Eur Hear J Suppl. 2003;5:G10–4. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruiz-Meana M, Fernandez-Sanz C, Garcia-Dorado D. The SR-mitochondria interaction: a new player in cardiac pathophysiology. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;88:30–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alberts B, Bray D, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Watson JD. Molecular biology of the cell. New York: Garland Science; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aon MA, Cortassa S, O’Rourke B. Mitochondrial oscillations in physiology and pathophysiology. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;641:98–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aon MA, Cortassa S, Akar FG, O’Rourke B. Mitochondrial criticality: a new concept at the turning point of life or death. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1762(2):232–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aon MA, Cortassa S, O’Rourke B. The fundamental organization of cardiac mitochondria as a network of coupled oscillators. Biophys J. 2006;91(11):4317–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurz FT, Aon MA, O’Rourke B, Armoundas AA. Spatio-temporal oscillations of individual mitochondria in cardiac myocytes reveal modulation of synchronized mitochondrial clusters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(32):14315–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berns MW, Siemens AE, Walter RJ. Mitochondrial fluorescence patterns in rhodamine 6G-stained myocardial cells in vitro: analysis by real-time computer video microscopy and laser microspot excitation. Cell Biophys. 1984;6(4):263–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Reilly CM, Fogarty KE, Drummond RM, Tuft RA, Walsh JVJr. Spontaneous mitochondrial depolarizations are independent of SR Ca2+ release. Biophys J. 2003;85(5):3350–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loew LM, Tuft RA, Carrington W, Fay FS. Imaging in five dimensions: time-dependent membrane potentials in individual mitochondria. Biophys J. 1993;65(6):2396–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huser J, Rechenmacher CE, Blatter LA. Imaging the permeability pore transition in single mitochondria. Biophys J. 1998;74(4):2129–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Rourke B, Ramza B, Marban E. Oscillations of membrane current and excitability driven by metabolic oscillations in heart cells. Science. 80- 1994;265:962–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romashko DN, Marban E, O’Rourke B. Subcellular metabolic transients and mitochondrial redox waves in heart cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(4):1618–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aon MA, Cortassa S, Marban E, O’Rourke B. Synchronized whole cell oscillations in mitochondrial metabolism triggered by a local release of reactive oxygen species in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(45):44735–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zorov DB, Filburn CR, Klotz LO, Zweier JL, Sollot SJ. Reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced ROS release: a new phenomenon accompanying induction of the mitochondrial permeability transition in cardiac myocytes. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1001–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zorov DB, Juhaszova M, Sollot SJ. Mitochondrial ROS-induced ROS release: an update and review. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1757:509–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Picard M Mitochondrial synapses: intracellular communication and signal integration. Trends Neurosci. 2015;38:468–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aon MA, Cortassa S, O’Rourke B. Percolation and criticality in a mitochondrial network. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(13):4447–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cortassa S, Aon MA, Winslow RL, O’Rourke B. A mitochondrial oscillator dependent on reactive oxygen species. Biophys J. 2004;87(3):2060–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kembro JM, Cortassa S, Aon MA. Complex oscillatory redox dynamics with signaling potential at the edge between normal and pathological mitochondrial function. Front Physiol. 2014;5:257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Rourke B Pathophysiological and protective roles of mitochondrial ion channels. J Physiol. 2000;529(1):23–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aon MA, Cortassa S, Akar FG, Brown DA, Zhou L, O’Rourke B. From mitochondrial dynamics to arrhythmias. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41(10):1940–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuznetsov AV, Usson Y, Leverve X, Margreiter R. Subcellular heterogeneity of mitochondrial function and dysfunction: evidence obtained by confocal imaging. Mol Cell Biochem. 2004;256–257(1–2):359–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manneschi L, Federico A. Polarographic analyses of subsarcolemmal and intermyofibrillar mitochondria from rat skeletal and cardiac muscle. J Neurol Sci. 1995;128(2):151–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Croston TL, Thapa D, Holden AA, Tveter KJ, Lewis SE, Shepherd DL, et al. Functional deficiencies of subsarcolemmal mitochondria in the type 2 diabetic human heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014;307(1):H54–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dabkowski ER, Williamson CL, Bukowski VC, Chapman RS, Leonard SS, Peer CJ, et al. Diabetic cardiomyopathy-associated dysfunction in spatially distinct mitochondrial subpopulations. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296(2):H359–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lesnefsky EJ, Chen Q, Hoppel CL. Mitochondrial metabolism in aging heart. Circ Res. 2016;118(10):1593–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuznetsov AV, Mayboroda O, Kunz D, Winkler K, Schubert W, Kunz WS. Functional imaging of mitochondria in saponin-permeabilized mice muscle fibers. J Cell Biol. 1998;140(5):1091–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lesnefsky EJ, Tandler B, Ye J, Slabe TJ, Turkaly J, Hoppel CL. Myocardial ischemia decreases oxidative phosphorylation through cytochrome oxidase in subsarcolemmal mitochondria. Am J Phys. 1997;273(3 Pt 2):H1544–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Philippi M, Sillau AH. Oxidative capacity distribution in skeletal muscle fibers of the rat. J Exp Biol. 1994;189:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Rourke B, Cortassa S, Aon MA. Mitochondrial ion channels: gatekeepers of life and death. Physiology. 2005;20:303–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Akar FG, Aon MA, Tomaselli GF, O’Rourke B. The mitochondrial origin of postischemic arrhythmias. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(12):3527–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kurz FT, Derungs T, Aon MA, O’Rourke B, Armoundas AA. Mitochondrial networks in cardiac myocytes reveal dynamic coupling behavior. Biophys J. 2015;108(8):1922–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anesti V, Scorrano L. The relationship between mitochondrial shape and function and the cytoskeleton. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1757:692–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rossignol R, Gilkerson R, Aggeler R, Yamagata K, Remington SJ, Capaldi RA. Energy substrate modulates mitochondrial structure and oxidative capacity in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:985–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yi M, Weaver D, Hajnoczky G. Control of mitochondrial motility and distribution by the calcium signal: a homeostatic circuit. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:661–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Breckwoldt MO, Pfister FMJ, Bradley PM, Marinković P, Williams PR, Brill MS, et al. Multiparametric optical analysis of mitochondrial redox signals during neuronal physiology and pathology in vivo. Nat Med. 2014;20(5):555–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Breckwoldt MO, Armoundas AA, Aon MA, Bendszus M, O’Rourke B, Schwarzländer M, et al. Mitochondrial redox and pH signaling occurs in axonal and synaptic organelle clusters. Sci Rep. 2016;6:23251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eisner V, Lenaers G, Hajnóczky G. Mitochondrial fusion is frequent in skeletal muscle and supports excitation-contraction coupling. J Cell Biol. 2014;205(2):179–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee S, Park YY, Kim SH, Nguyen OT, Yoo YS, Chan GK, Sun X, Cho H. Human mitochondrial Fis1 links to cell cycle regulators at G2/M transition. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71(4):711–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kurz FT, Aon MA, O’Rourke B, Armoundas AA. Wavelet analysis reveals heterogeneous time-dependent oscillations of individual mitochondria. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;299(5):H1736–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nivala M, Korge P, Nivala M, Weiss JN, Qu Z. Linking flickering to waves and whole-cell oscillations in a mitochondrial network model. Biophys J. 2011;101(9):2102–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scaduto RC, Grotyohann LW. Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential using fluorescent rhodamine derivatives. Biophys J. 1999;76(1):469–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aon MA, Cortassa S, Maack C, O’Rourke B. Sequential opening of mitochondrial ion channels as a function of glutathione redox thiol status. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(30):21889–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou L, Aon MA, Almas T, Cortassa S, Winslow RL, O’Rourke B. A reaction-diffusion model of ROS-induced ROS release in a mitochondrial network. PLoS Comput Biol. 2010;6(1):e1000657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li P, Yi Z. Synchronization of Kuramoto oscillators in random complex networks. Phys A Stat Mech Appl. 2008;387(7):1669–74. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lopaschuk GD, Ussher JR, Folmes CDL, Jaswal JS, Stanley WC. Myocardial fatty acid metabolism in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:207–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stanley WC, Recchia FA, Lopaschuk GD. Myocardial substrate metabolism in the normal and failing heart. Physiol Rev. 2005;85(3):1093–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aon MA, Cortassa S (n.d.). Mitochondrial network energetics in the heart. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 4(6):599–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Slodzinski MK, Aon MA, O’Rourke B. Glutathione oxidation as a trigger of mitochondrial depolarization and oscillation in intact hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;45(5):650–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Porat-Shliom N, Chen Y, Tora M, Shitara A, Masedunskas A, Weigert R, et al. In vivo tissue-wide synchronization of mitochondrial metabolic oscillations. Cell Rep. 2014;9(2):514–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cortassa S, Aon MA. Dynamics of mitochondrial redox and energy networks: insights from an experimental-computational synergy In: Aon MA, Saks V, Schlattner U, editors. Systems biology of metabolic and signaling networks. energy, mass and information transfer. 1st ed. Berlin: Springer; 2013. p. 115–44. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cascante M, Marin S. Metabolomics and fluxomics approaches. Essays Biochem. 2008;45:67–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barrat A, Barthélemy M, Vespignani A. Dynamical processes on complex networks. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Albert R, Jeong H, Barabasi A. Error and attack tolerance of complex networks. Nature. 2000;406(6794):378–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Barabasi AL, Oltvai ZN. Network biology: understanding the cell’s functional organization. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5(2):101–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Alon U Network motifs: theory and experimental approaches. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8(6):450–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aon MA, Cortassa S, Lloyd D. Chaos in biochemistry and physiology Encyclopedia of molecular cell biology and molecular medicine. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rosenfeld S Mathematical descriptions of biochemical networks: stability, stochasticity, evolution. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2011;106(2):400–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aon MA, Roussel MR, Cortassa S, O’Rourke B, Murray DB, Beckmann M, et al. The scale-free dynamics of eukaryotic cells. PLoS One. 2008;3(11):e3624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yates FE. Self-organizing systems In: Boyd CAR, Noble D, editors. The logic of life. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1993. p. 189–218. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mazloom AR, et al. Modeling a complex biological network with temporal heterogeneity: cardiac myocyte plasticity as a case study. Complex. 2009;1(LNICST 4):467–86. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tsiairis CD, Aulehla A, Aulehla A, Wiegraebe W, Baubet V, Wahl MB, et al. Self-organization of embryonic genetic oscillators into spatiotemporal wave patterns. Cell. 2016;164(4):656–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brown DA, Aon MA, Frasier CR, Sloan RC, Maloney AH, Anderson EJ, et al. Cardiac arrhythmias induced by glutathione oxidation can be inhibited by preventing mitochondrial depolarization. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48(4):673–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kesten H What is … Percolation? Not Am Math Soc. 2006;53(5):572–3. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhou L, O’Rourke B. Cardiac mitochondrial network excitability: insights from computational analysis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302(11):H2178–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cortassa S, Aon MA, Marban E, Winslow RL, O’Rourke B. An integrated model of cardiac mitochondrial energy metabolism and calcium dynamics. Biophys J. 2003;84(4):2734–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brady NR, Hamacher-Brady A, Westerhoff HV, Gottlieb RA. A wave of reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced ROS release in a sea of excitable mitochondria. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8(9–10):1651–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yang L, Paavo K, Weiss JN, Qu Z. Mitochondrial oscillations and waves in cardiac myocytes: insights from computational models. Biophys J. 2010;98:1428–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Park J, Lee J, Choi C. Mitochondrial network determines intracellular ROS dynamics and sensitivity to oxidative stress through switching inter-mitochondrial messengers. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e23211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liu X, Weaver D, Shirihai O, Hajnóczky G. Mitochondrial “kiss-and-run”: interplay between mitochondrial motility and fusion-fission dynamics. EMBO J. 2009;28(20):3074–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Twig G, Liu X, Liesa M, Wikstrom JD, Molina AJA, Las G, et al. Biophysical properties of mitochondrial fusion events in pancreatic beta-cells and cardiac cells unravel potential control mechanisms of its selectivity. Am J Phys Cell Physiol. 2010;299(2):C477–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sukhorukov VM, Dikov D, Reichert AS, Meyer-Hermann M, Scheckhuber C, Erjavec N, et al. Emergence of the mitochondrial reticulum from fission and fusion dynamics Beard DA, editor PLoS Comput Biol. 2012;8(10):e1002745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Blake WJ, Kaern M, Cantor CR, Collins JJ. Noise in eukaryotic gene expression. Nature. 2003;422(6932):633–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kepler TB, Elston TC. Stochasticity in transcriptional regulation: origins, consequences, and mathematical representations. Biophys J. 2001;81(6):3116–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lorenz EN. Deterministic nonperiodic flow. J Atmos Sci. 1963;20(2):130–41. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rosenfeld S, Kapetanovic I. Systems biology and cancer prevention: all options on the table. Gene Regul Syst Biol. 2008;2:307–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Aon MA, Camara AKS. Mitochondria: hubs of cellular signaling, energetics and redox balance. A rich, vibrant, and diverse landscape of mitochondrial research. Front Physiol. 2015;6:94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kurz FT, Aon MA, O’Rourke B, Armoundas AA. Cardiac mitochondria exhibit dynamic functional clustering. Front Physiol. 2014;5:329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Winfree AT. Biological rhythms and the behavior of populations of coupled oscillators. J Theor Biol. 1967;16:15–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kuramoto Y Chemical oscillations, waves, and turbulence. Berlin: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Acebrón JA, Bonilla LL, Vicente P, Conrad J, Ritort F, Spigler R. The Kuramoto model: a simple paradigm for synchronization phenomena. Rev Mod Phys. 2005;77:137–85. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Strogatz SH. From Kuramoto to Crawford: exploring the onset of synchronization in population of coupled oscillators. Phys D. 2000;143:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kembro JM, Aon MA, Winslow RL, O’Rourke B, Cortassa S. (n.d.) Integrating mitochondrial energetics, redox and ROS metabolic networks: a two-compartment model. Biophys J. 104(2):332–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Aon MA, Cortassa S, O’Rourke B. Redox-optimized ROS balance: a unifying hypothesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1797;6–7:865–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cortassa S, O’Rourke B, Aon MA. Redox-optimized ROS balance and the relationship between mitochondrial respiration and ROS. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1837(2):287–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Calabrese EJ. Hormesis and medicine. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;66(5):594–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ristow M, Zarse K. How increased oxidative stress promotes longevity and metabolic health: the concept of mitochondrial hormesis (mitohormesis). Exp Gerontol. 2010;45(6):410–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bratic I, Trifunovic A. Mitochondrial energy metabolism and ageing. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1797;6–7:961–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Aon MA, Cortassa S, Juhaszova M, Sollott SJ. Mitochondrial health, the epigenome and healthspan. Clin Sci (Lond). 2016;130(15):1285–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tocchetti CG, Caceres V, Stanley BA, Xie C, Shi S, Watson WH, et al. GSH or palmitate preserves mitochondrial energetic/redox balance, preventing mechanical dysfunction in metabolically challenged myocytes/hearts from type 2 diabetic mice. Diabetes. 2012;61(12):3094–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Stary V, Puppala D, Scherrer-Crosbie M, Dillmann WH, Armoundas AA. SERCA2a upregulation ameliorates cellular alternans induced by metabolic inhibition. J Appl Physiol. 2016;120(8):865–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wallace DC. Mitochondria and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(10):685–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nunnari J, Suomalainen A. Mitochondria: in sickness and in health. Cell. 2012;148(6):1145–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Giordano FJ. Oxygen, oxidative stress, hypoxia, and heart failure. J Clin Invest. 2005; 115(3):500–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Maack C, Dabew ER, Hohl M, Schäfers H-J, Böhm M. Endogenous activation of mitochondrial KATP channels protects human failing myocardium from hydroxyl radical-induced stunning. Circ Res. 2009;105(8):811–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Keller EF. Revisiting “scale-free” networks. Bioessays. Wiley Periodicals, Inc. 2005;27(10): 1060–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Merton RK. The Matthew effect in science. Science. (80- ) 1968;159:56–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.West BJ. Fractal physiology and the fractional calculus: a perspective. Front Physiol. 2010;1:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Roussel MR, Lloyd D. Observation of a chaotic multioscillatory metabolic attractor by real-time monitoring of a yeast continuous culture. FEBS J. 2007;274(4):1011–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Murray AJ. Mitochondria at the extremes: pioneers, protectorates, protagonists. Extrem Physiol Med. 2014;3:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Aon MA, Cortassa S, Lemar KM, Hayes AJ, Lloyd D. Single and cell population respiratory oscillations in yeast: a 2-photon scanning laser microscopy study. FEBS Lett. 2007;581(1):8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Aon M, Cortassa S, O’Rourke B. Chapter 4: On the network properties of mitochondria In: Saks V, editor. Molecular system bioenergetics. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KG; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Fox MD, Snyder AZ, Vincent JL, Corbetta M, Van Essen DC, Raichle ME. The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(27):9673–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Greicius MD, Krasnow B, Reiss AL, Menon V. Functional connectivity in the resting brain: a network analysis of the default mode hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(1):253–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Passingham RE, Stephan KE, Kötter R. The anatomical basis of functional localization in the cortex. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3(8):606–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Eguíluz VM, Chialvo DR, Cecchi GA, Baliki M, Apkarian AV. Scale-free brain functional networks. Phys Rev Lett. 2005;94(1):18102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Watts DJ, Strogatz SH. Collective dynamics of “small-world” networks. Nature. 1998;393:440–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Percha B, Dzakpasu R, Zochowski M, Parent J. Transition from local to global phase synchrony in small world neural network and its possible implications for epilepsy. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlinear Soft Matter Phys. 2005;72(3 Pt 1):31909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Erdős P, Rényi A. On the evolution of random graphs. Publ Math Inst Hung Acad Sci. 1960;5:17–61. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Viola HM, Arthur PG, Hool LC. Evidence for regulation of mitochondrial function by the L-type Ca2+ channel in ventricular myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;46(6):1016–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Harenberg S, Bello G, Gjeltema L, Ranshous S, Harlalka J, Seay R, et al. Community detection in large-scale networks: a survey and empirical evaluation. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Comput Stat. 2014;6(6):426–39. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Dabkowski ER, Baseler WA, Williamson CL, Powell M, Razunguzwa TT, Frisbee JC, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in the type 2 diabetic heart is associated with alterations in spatially distinct mitochondrial proteomes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;299(2): H529–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kivela M, Arenas A, Barthelemy M, Gleeson JP, Moreno Y, Porter MA. Multilayer networks. J Complex Networks. Oxford University Press 2014;2(3):203–71. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Boccaletti S, Bianconi G, Criado R, del Genio CI, Gómez-Gardeñes J, Romance M, et al. The structure and dynamics of multilayer networks. Phys Rep. 2014;544(1):1–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kurz FT, Kembro JM, Flesia AG, Armoundas AA, Cortassa S, Aon MA, et al. Network dynamics: quantitative analysis of complex behavior in metabolism, organelles, and cells, from experiments to models and back. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2017;9(1):e1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Wang W, Gong G, Wang X, Wei-LaPierre L, Cheng H, Dirksen R, et al. Mitochondrial flash: integrative reactive oxygen species and pH signals in cell and organelle biology. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2016;25(9):534–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Belykh VN, Osipov GV, Petrov VS, Suykens JAK, Vandewalle J. Cluster synchronization in oscillatory networks. Chaos. 2008;18:37106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Wang X, Zhou C, Lai CH. Multiple effects of gradient coupling on network synchronization. Phys Rev E. 2008;77(5):056208.1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Tinsley MR, Nkomo S, Showalter K. Chimera and phase-cluster states in populations of coupled chemical oscillators. Nat Phys. 2012;8(9):662–5. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Nkomo S, Tinsley MR, Showalter K. Chimera states in populations of nonlocally coupled chemical oscillators. Phys Rev Lett. 2013;110(24):244102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]