Abstract

Scope

It is investigated whether at realistic dietary intake bixin and crocetin could induce peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor γ (PPARγ)‐mediated gene expression in humans using a combined in vitro–in silico approach.

Methods and results

Concentration–response curves obtained from in vitro PPARγ‐reporter gene assays are converted to in vivo dose–response curves using physiologically based kinetic modeling‐facilitated reverse dosimetry, from which the benchmark dose levels resulting in a 50% effect above background level (BMD50) are predicted and subsequently compared to dietary exposure levels. Bixin and crocetin activated PPARγ‐mediated gene transcription in a concentration‐dependent manner with similar potencies. Due to differences in kinetics, the predicted BMD50 values for in vivo PPARγ activation are about 30‐fold different, amounting to 115 and 3505 mg kg bw−1 for crocetin and bixin, respectively. Human dietary and/or supplemental estimated daily intakes may reach these BMD50 values for crocetin but not for bixin, pointing at better possibilities for in vivo PPARγ activation by crocetin.

Conclusion

Based on a combined in vitro–in silico approach, it is estimated whether at realistic dietary intakes plasma concentrations of bixin and crocetin are likely to reach concentrations that activate PPARγ‐mediated gene expression, without the need for a human intervention study.

Keywords: bixin, crocetin, peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor γ, physiologically based kinetic modeling, reverse dosimetry

Beneficial health effects of bixin and crocetin are suggested via activation of peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor γ (PPARγ). However, it remains unclear whether PPARγ activation can be achieved at realistic human estimated daily intake levels. A combined in vitro, physiologically based kinetic modeling can predict the effects of functional food ingredients in human without the need for a human intervention study.

1. Introduction

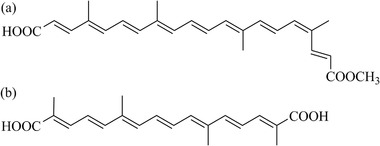

Bixin (methyl hydrogen 9′‐cis‐6,6′‐diapocarotene‐6,6′‐dioate) and crocetin (8,8′‐diapocarotene‐8,8′‐dioic acid) (Figure 1) are food‐borne carotenoids.1, 2 Bixin is present in the extract prepared from the seed coat of annatto (Bixa orellana L). Annato extracts containing bixin are an approved food color additive (E160b), for which the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) established an acceptable daily intake (ADI) of 6 mg kg bw−1 per day.3, 4, 5 Crocetin occurs naturally in the fruits of gardenia (Gardenia jasminoides Ellis) and in the stigma of saffron (Crocus sativus L.) frequently consumed due to its use as food colorant and flavoring.6 Saffron containing crocetin is recognized as food additive in the United States, while JECFA recognized saffron as a food ingredient rather than a food additive.7 In addition to use as food additives, bixin and crocetin have been considered as potential functional food ingredients with beneficial effects in various diseases, including type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).8, 9

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of a) bixin and b) crocetin.

Studies in experimental animals revealed that bixin shows hypoglycemic activity in streptozotocin‐induced diabetic rats,10 and that crocetin enhances insulin sensitivity in insulin resistant rats,11, 12, 13 suggesting their potential beneficial roles in T2DM. The interest to explore the carotenoids as potential functional food ingredients is increasing, due to the growing reports about side effects associated with current T2DM medication. Thiazolidinediones (TZDs), which once were the most widely used drugs for treatment of T2DM,14 have been reported to cause body weight gain and increased risks for myocardial infarction, peripheral edema, and bone fracture.15 TZDs are believed to exert their therapeutic effects via activation of peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor γ (PPARγ), which is also suggested as mode of action underlying the potential beneficial effects of bixin and crocetin.

PPARγ activation has been reported to increase insulin sensitivity,16 decrease free fatty acid levels in plasma, and increase lipid storage in adipose tissue.17 Several carotenoids, including bixin and also norbixin, β‐carotene, lutein, neoxanthin, phytoene, lycopene, β‐carotene, astaxanthin, β‐cryptoxanthin, zeaxanthin, γ‐carotene, δ‐carotene have been shown to activate PPARγ‐mediated gene expression in vitro.18, 19, 20, 21 It remains to be established however, whether the reported PPARγ activating characteristics can also be expected at realistic human dietary intake levels.

Therefore the aim of the present study was to investigate whether the reported PPARγ activating characteristics of bixin and crocetin may be expected at realistic human daily intake levels. To this end, concentration–response curves for bixin‐ and crocetin‐dependent activation of PPARγ‐mediated gene expression in a stably transfected U2OS PPARγ reporter gene cell line were converted to predicted in vivo dose–response curves using so‐called physiologically based kinetic (PBK) modeling facilitated reverse dosimetry. This approach facilitates evaluation of whether PPARγ activating characteristics of bixin and crocetin may be expected at realistic human dietary intake levels without the need for a human intervention study.

A PBK model can predict the concentration of a compound and its relevant metabolites in any tissue at any point in time and for any dose level, within its applicability domain.22 After the PBK model is validated with the available in vivo data, it can be used to convert in vitro concentrations, set equal to internal concentrations in blood or a tissue of choice, to corresponding in vivo dose levels, by so‐called reverse dosimetry.23, 24 In PBK modeling facilitated reverse dosimetry, the PBK model is used in the reverse order compared to the forward dosimetry that is generally applied in pharmacokinetics. Forward dosimetry is applied to calculate the internal concentration of a compound or its metabolite that can be expected in blood or a relevant tissue upon a given dose level. In the reverse dosimetry approach, in vitro concentrations are set equal to blood or tissue levels of the respective compound in the PBK model, following which the PBK model is used to calculate the corresponding in vivo dose level for any given route of administration. Subsequent benchmark dose (BMD) modeling can be applied on the predicted in vivo dose–response data, to determine effective exposure levels for humans, like a BMD value defining the dose levels inducing a limited but measurable response above background level and the BMDL values, the lower confidence limits of the BMD.23

2. Experimental Section

2.1. In Vitro PPARγ CALUX Assay of Bixin and Crocetin

Bixin (96.5% purity by HPLC) was purchased from International Laboratory (San Fransisco, USA). Norbixin was extracted from annatto seeds using extraction with 8% ethanol in dichloromethane (CH2Cl2). Norbixin was purified from this extract by preparative thin layer chromatography (TLC). Crocetin (98% purity by HPLC) was purchased from Carotenature (Lupsingen, Switzerland). The cytotoxicity of bixin, norbixin, and crocetin was tested in vitro as previously decribed using the cytotox CALUX cell line to ascertain that the test compounds did not affect the luciferase activity themselves under the conditions tested.25 PPARγ‐mediated gene expression was tested using the PPARγ2‐reporter gene assay in PPAR‐γ2 CALUX cells provided by BioDetection Systems BV (Amsterdam, The Netherlands).26 To analyze the effects of bixin, norbixin, and crocetin on PPARγ‐mediated gene expression, the cells were incubated for 24 h at increasing concentrations (0.01–100 µm) of the compounds in culture medium added from 200 times concentrated stock solutions in THF. The final concentration of THF in exposure medium was 0.5% v/v. 1 µm rosiglitazone, a well‐known PPARγ agonist,27 was included in every plate as positive control (added from a 200 times concentrated stock solution in DMSO). Luciferase activity of the lysate was quantified at room temperature using a luminometer (Glowmax Multi Detection System, Promega Madison USA).

Data are presented as mean values ± SD from three independent experiments with six replicates per plate. The PPARγ responses were expressed relative to the response of the rosiglitazone positive control set at 100%. The obtained concentration–response curves were fitted with a symmetrical sigmoidal model (Hill slope) using GraphPad Prism software (version 5.00 for Windows, GraphPad software, San Diego, USA) which was further used to derive EC50 values.

2.2. Determination of Model Parameter Values for Hepatic Clearance

Pooled human cryopreserved hepatocytes (HEP10) for suspension were purchased from Life Technologies (Bleiswijk, The Netherlands). The cells were thawed and assessed for metabolic stability in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol (Supporting information 1). The intrinsic clearance (CL int) values of bixin and crocetin were estimated by a substrate depletion approach using the protocol provided by the supplier for in vitro assessment of metabolic stability in suspensions with cryopreserved pooled mixed gender human hepatocytes (HEP10) with little modifications. The rate of disappearance of the parent compounds at a single, low substrate concentration (i.e., 3 µm) were scaled to in vivo clearance values to describe the hepatic clearance of the parent compounds in the PBK model. After incubation at time points 0, 7.5, 15, 30, and 60 min, the residual parent compounds were analyzed using a Waters UPLC‐DAD‐System. For all incubations, three independent replicates were performed.

The slope of the linear curve for the time‐dependent percent residual parent compound from the HEP10 containing reaction mixtures corrected for the percent residual parent compound in the corresponding blancs without cells was used to determine the in vitro t 1/2 (expressed in minutes) of the parent compound. Using the elimination rate constant k = 0.693/t 1/2, CL int,in vitro expressed in µL min−1 106 cells−1 can be described as Equation (1)

| (1) |

where V is the volume of the incubation (expressed in microliter) and N is number of hepatocytes per well (expressed in 106 cells).28 The human physiological parameters reported by Soars et al.29 were used to scale the in vitro CL int values to in vivo CL int values which were applied in the PBK models (Equation 2):

| (2) |

where CL int,in vivo is in vivo CL int (L h−1), WL is liver weight of 20 g kg bw−1, bw is human body weight of 70 kg used in the PBK models, Hep is hepatocellularity of 120 × 106 cells g−1 liver, CL int,in vitro is in vitro CL int (µL min−1 10−6 cells), 60 is the value of 60 min within 1 h, 10−6 to convert from microliter to liter.

As norbixin, which is a likely metabolite of bixin, was unable to induce PPARγ‐mediated gene transcription even at the highest concentration tested, and in line with literature,18 it was not considered in the clearance studies and subsequent PBK modeling.

2.3. Development and Evaluation of a PBK Model for Bixin and Crocetin

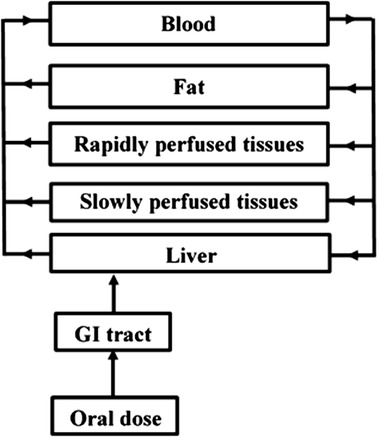

A PBK model is a set of mathematical equations which describe the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) characteristics of a compound within an organism based on three types of parameters, that is, i) physiological and anatomical (e.g., cardiac output, tissue volumes, and tissue blood flows), ii) physico‐chemical (blood/tissue partition coefficients), and iii) kinetic parameters (e.g., kinetic constants for metabolic reactions).23 Figure 2 depicts the conceptual PBK model, which consists of separate compartments for the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, liver, slowly perfused tissues (e.g., skin, muscle, bone), rapidly perfused tissues (e.g., heart, lung, brain), fat, and blood.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the conceptual PBK model for bixin and crocetin in humans.

The values of human physiological and anatomical parameters were obtained from literature,30 while the blood/tissue partition coefficients were estimated using the formula using log p‐values of olive oil, pKa, and fraction unbound in serum as input,31 and as shown in Tables S1 and S2, Supporting Information 2. Log Kow values were estimated using ChemBio‐Draw Ultra 14.0 (Cambridge‐Soft, USA). Kinetic parameters for hepatic clearance of bixin and crocetin were determined using HEP10 incubations performed as described earlier. Berkeley Madonna 8.3.18 (Macey and Oster, UC Berkeley, CA) was used to code and numerically integrate the PBK models applying Rosenbrock's algorithm for stiff systems. Compared to other algorithms in Berkeley Madonna (BM), the Rosenbrock's algorithm serves better for stiff systems32, 33, 34 and was shown to provide adequate results in previous studies providing proofs of principle for the PBK model based reverse dosimetry.35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42

The model code for the developed PBK models of bixin is presented in Supporting Information 3.

To evaluate the PBK model performance, predicted maximum bixin and crocetin concentrations in the blood were compared to reported maximum blood concentrations in humans as reported in the literature.43, 44 Maximum concentrations of bixin and crocetin in blood were predicted by PBK modeling using a ka value of 1 h−1 for each compound assuming fast and complete uptake.45

In addition a sensitivity analysis was performed to identify the key parameters which contribute most to the predicted maximum blood concentrations (C max) at an oral dose of 0.23 mg kg bw−1 for bixin and 0.25 mg kg bw−1 for crocetin. This sensitivity analysis was performed as described previously46 calculating normalized sensitivity coefficients (SCs) by Equation (3).

| (3) |

where C is the initial value of the model output, C′ is the modified value of the model output resulting from an increase in parameter value, P is the initial parameter value, and P′ is the modified parameter value. Each parameter was analyzed individually by changing one parameter at a time (5% increase) and keeping the other parameters the same.

2.4. Translation of In Vitro PPARγ Concentration Response Curves to In Vivo PPARγ Dose Response Curves

The in vitro concentration–response curves for bixin‐ and crocetin‐induced activation of PPARγ mediated gene transcription were translated into predicted in vivo dose–response curves using PBK modeling‐facilitated reverse dosimetry. This reverse dosimetry was based on the concentration of the parent compound, which was assumed to represent the form of the carotenoids activating PPARγ‐mediated gene expression.

Furthermore, within this translation a correction was made to take the differences in albumin and lipid concentrations between in vitro and in vivo conditions into account. This was done because it was assumed that only the free fraction of the carotenoid will be available to exert the effects. Extracellular instead of intracellular concentrations were used because unbound concentrations in blood were considered to best match the in vitro model where cells were exposed to the carotenoids dissolved in the medium on top of the cell layer. The unbound fraction (f ub,in vitro) was estimated to determine the fraction bound (f b,in vitro) to lipid and protein in culture medium.47 Each nominal concentration applied in the in vitro PPARγ‐mediated gene expression assay (EC in vitro) of bixin and crocetin was extrapolated to an in vivo effect concentration (EC in vivo) according to the extrapolation rule of Gülden and Seibert47 as described in Supporting Information 4. Each in vivo concentration (EC in vivo), thus obtained was set equal to the blood C max of bixin and crocetin in the PBK model. The PBK model was subsequently used to calculate the corresponding oral dose levels in humans to derive the in vivo dose–response curves.

To define the benchmark dose resulting in a 50% increase over the background level of PPARγ activation (BMD50) the predicted in vivo dose–response data for bixin‐ and crocetin‐induced PPARγ‐mediated gene expression in human were used for BMD modeling. Dose–response modeling and BMD analysis were performed using the EFSA BMD modeling webtool (PROAST version 66.38, https://shiny-efsa.openanalytics.eu/app/bmd).48 Data were analyzed using the exponential model for continuous data because this model appeared to provide the best (goodness of) fit with the lowest Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) value among the available models. In the visualization result of PROAST, a critical effect size (CES), critical effect dose (CED), lower bound of the CED (CEDL), upper bound of the CED (CEDU) correspond to the BMR, BMD50, BMDL50 (lower bound of the BMD50 95%‐confidence interval), and BMDU50 (upper bound of the BMD50 95%‐confidence interval), respectively.

3. Results

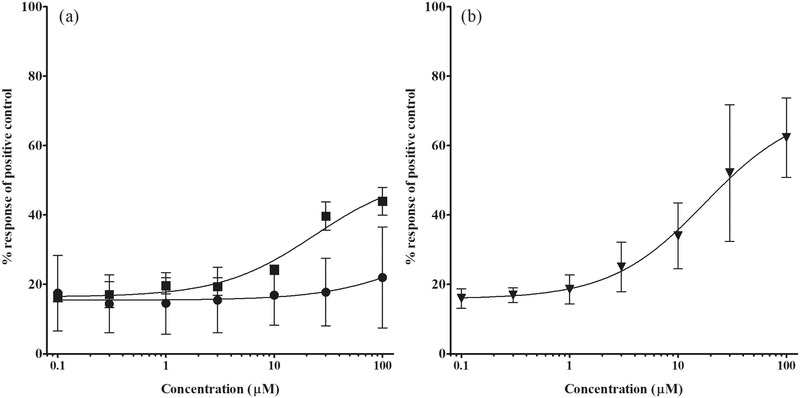

3.1. Bixin‐ and Crocetin‐Induced Activation of PPARγ‐Mediated Gene Expression

Bixin and crocetin increased PPARγ‐mediated gene expression in a concentration‐dependent manner, while norbixin appeared unable to induce PPARγ‐mediated gene expression up to the highest concentration tested of 100 µm (Figure 3). Bixin and crocetin were of similar potency and had an EC50 of 23.5 and 17.7 µm, respectively. Using the cytotox CALUX cell line it was confirmed that at the concentrations tested there was no cytotoxicity and the test compounds did not affect the luciferase activity (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Concentration‐dependent induction of PPARγ‐mediated gene expression by a) bixin (squares) and norbixin (circles), and b) crocetin (triangles) expressed as percentage of the response induced by the positive control 1 µm rosiglitazone set at 100%. The induction by roziglitazone was between sevenfold and eightfold. Values are presented as means ± SD derived from three independent experiments.

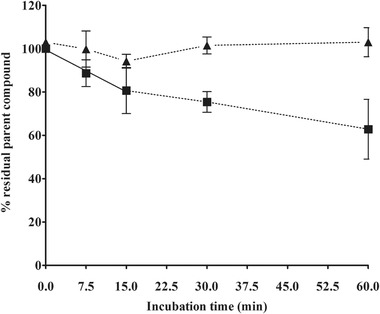

3.2. Hepatic Clearance of Bixin and Crocetin

The hepatic clearance of bixin and crocetin was determined for subsequent PBK modeling using incubations with primary human hepatocytes. Figure 4 shows that bixin concentrations decreased during the incubation, resulting in an in vitro clearance (CL int,in vitro) of 36.13 µL min−1 106 cells−1, and a scaled in vivo clearance (CL int,in vivo) of 364.16 L h−1. Crocetin concentrations were not clearly affected along the 60 min incubation with human hepatocytes and therefore, for subsequent PBK modeling, hepatic clearance was assumed to be negligible (CL int,in vivo = 0).

Figure 4.

Hepatic clearance of bixin (square) and crocetin (triangle) during the incubations with primary human hepatocytes for 60 min. The slope for linear regression until 15 min (straight line) was used to determine the in vitro half‐life (t 1/2) of bixin.

3.3. Evaluation of the PBK Models for Bixin and Crocetin

To evaluate the PBK models, the dose‐dependent blood concentrations of bixin and crocetin in humans were predicted and compared to blood concentrations resulting from oral intake of bixin and crocetin reported in literature. For bixin, the one study available reported a maximum blood concentration (C max) of 0.029 µm after an oral dose of 0.23 mg kg bw−1.43 This predicted C max value accurately matched the PBK model based predicted C max value of 0.027 µm. For crocetin, also a single human study was available reporting C max values after oral intake at three different dose levels of 0.125, 0.25, and 0.374 mg kg bw−1.44 The PBK model based predicted C max values at these dose levels amounted to 0.12, 0.25, and 0.37 µm which were 2.5‐, 2.5‐, and 2.3‐fold lower than the reported values of 0.31, 0.61, and 0.85 µm, respectively. Thus, comparison of the predicted and reported blood levels of bixin and crocetin reveals that the PBK models adequately predicted the C max values. Furthermore, comparison of the C max values of bixin and crocetin reveals that the C max values for bixin are about 5–14 times lower than those of crocetin.

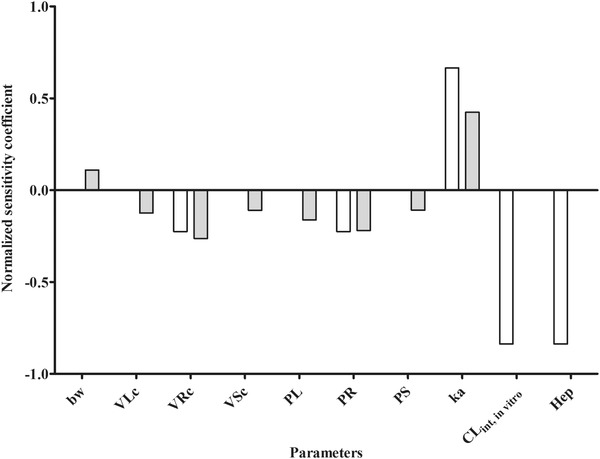

The performance of the developed models was further evaluated by a sensitivity analysis to assess the parameters that affect the prediction of the C max of bixin and crocetin in blood to the largest extent. The sensitivity analysis was performed at an oral dose of 0.23 mg kg bw−1 for bixin and 0.25 mg kg bw−1 for crocetin, which are dose levels applied in the available in vivo kinetic studies. Only the parameters that resulted in a normalized sensitivity coefficient higher than 0.1 (in absolute value) are shown in Figure 5. The results obtained reveal that the prediction of C max in the PBK model is most sensitive to the parameters related to the liver including the hepatic clearance (CL int), the absorption rate constant for uptake from the GI tract into the liver (ka) and hepatocellularity (Hep).

Figure 5.

Normalized sensitivity coefficients for the parameters of the PBK model for bixin and crocetin on predicted C max in blood at a single oral dose of 0.23 mg kg bw−1 for bixin (white bars) and 0.25 mg kg bw−1 (gray bars) for crocetin. bw, body weight; VLc, fraction of liver volume; VRc, fraction of rapidly perfused tissues volume; VSc, fraction of slowly perfused tissues volume; PL, liver/blood partition coefficient; PS, slowly perfused tissue/blood partition coefficient; PR, rapidly perfused tissue/blood partition coefficient; ka, uptake rate constant; C int,in vitro, in vitro intrinsic clearance of bixin/crocetin; Hep, hepatocellularity.

Figure 6 presents the in vivo dose–reponse curves obtained for bixin and crocetin when, upon correction for the differences in unbound fraction, the in vitro concentrations were converted to corresponding in vivo dose levels. BMD modeling of these data (for details, see Figure S1, Supporting Information 5), resulted in the BMD50, BMDL50 ,and BMDU50 values presented in Table 1. From these data it follows that the BMD50 of bixin is about 30 times higher than that of crocetin.

Figure 6.

Predicted in vivo dose–response curves for PPARγ‐mediated gene expression of bixin (square) and crocetin (triangle) in humans. Predicted dose–response data were obtained using PBK modeling‐facilitated reverse dosimetry for conversion of in vitro concentration–response data obtained in the PPARγ CALUX reporter gene assay (Figure 3).

Table 1.

BMD50 and BMDL50‐BMDU50 values derived from the dose–response curves predicted using PBK modeling‐facilitated reverse dosimetry to convert the in vitro concentration–response curves as obtained in the present study to in vivo dose–response curves

| Compound | BMD50 [mg kg bw−1] | Predicted BMDL50‐BMDU50 [mg kg bw−1] |

|---|---|---|

| Bixin | 3505 | 1710–5220 |

| Crocetin | 115 | 0.32–374 |

3.4. Comparison to Human Dietary Intake Levels

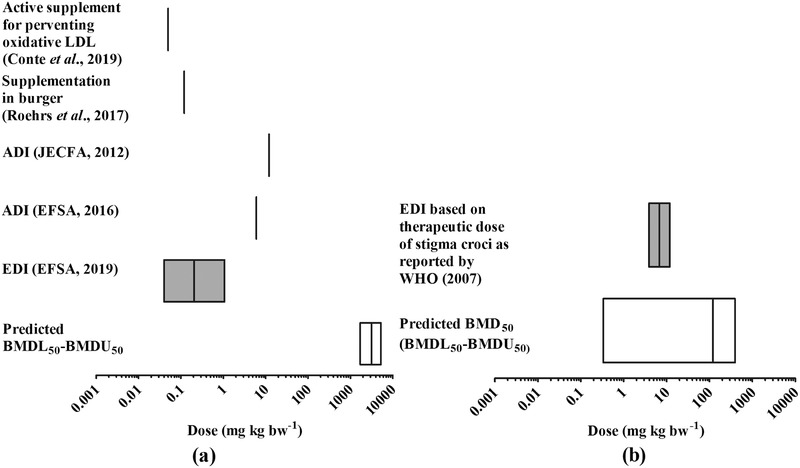

The predicted BMD50 values including the BMDL50 and BMDU50 values thus obtained were compared to the reported dose levels of bixin and crocetin resulting from daily intake in humans as taken from the literature. Figure 7 shows a comparison of the predicted BMD50 values (presenting also the BMDL50‐BMDU50 range) for bixin‐ and crocetin‐mediated induction of PPARγ activity in vivo and the estimated dietary intake levels, resulting from use of the compounds as food additives and/or as functional food ingredients in food supplements.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the predicted in vivo BMD50, BMDL50‐BMDU50 for PPARγ activation with available EDI values for a) bixin and b) crocetin in humans. For comparison also the available ADI values are included.

The recent exposure assessment performed by EFSA3 reported the estimated maximum level of dietary exposure to bixin‐based annatto extracts (E 160b) from its use as food additive to amount to 0.04–1.07 mg kg bw−1 per day (95th percentile). This value is 3 to 5 orders of magnitude lower than the predicted BMD50 for PPARγ acivation, which reveals that normal dietary intake of bixin is expected to not result in activation of PPARγ‐mediated gene expression. Also bixin supplementation at a level of 0.05 mg kg bw−1 in healty human subjects which was reported to be an active dose to prevent early oxidative modifications in LDL as key event of atherosclerosis49 is several orders of magnitude below the predicted BMD50 for inducing the PPARγ‐mediated gene expression. This result is in line with results reported before concluding that bixin supplementation amounting to 1.2 mg kg bw−1 (10% of the ADI) had no effect on the postprandial oxidative LDL levels and thus seemed inactive in preventing the risk of cardiovascular disease and insulin resistance.50 Furthermore comparison of the predicted BMD50 values to the ADI values for bixin of 6 and 0–12 mg kg bw−1 day‐1 established by EFSA3 and JECFA51 reveals that these ADI values are also 2 to 3 orders of magnitude lower than the BMD50 indicating that they will prevent effective PPARγ‐mediated gene expression.

For crocetin there are no existing values for the EDI resulting from its use as a food ingredient. However, the WHO52 based on the Pharmacopoeia of the People's Republic of China reported that the recommended therapeutic daily dose of stigma croci (saffron stigma) is 3–9 g. Considering the level of crocin of 25.95 mg.100 mg−1 dry saffron53 and the mass ratio of crocetin to crocin, this dose of stigma croci is estimated to be equivalent to an intake of crocetin of 3.74–11.2 mg kg1 bw−1 per day for a 70 kg person (see Supporting Information 6 for the detailed calculation). Comparison of this EDI to the predicted BMD50 and BMDL50‐BMDU50 range for crocetin reveals that the recommended therapeutic dose as reported by the WHO52 is predicted to represent a dose levels where PPARγ activation in human might be expected, although it must be noted that the confidence intervals in the predicted dose–response data for crocetin are large.

4. Discussion

PPARγ has been identified as a ligand‐regulated nuclear receptor reported to increase insulin sensitivity in the treatment of T2DM. This made PPARγ a target for drug development and also resulted in reports on various natural dietary ingredients able to activate PPARγ‐mediated gene expression. This includes reports on activation of PPARγ by various carotenoids as detected in in vitro reporter gene assays.18, 19, 20, 21 Some carotenoids, including the model compounds of the present study bixin and crocetin have also been proposed for use as functional food ingredients and/or are used in traditional medicine to treat T2DM‐related symptoms.54 For crocetin, the therapeutic use of crocetin‐containing stigma croci has been proposed at dose levels amounts to 3–9 g per person, estimated in the present study to be equivalent to 3.74–11.2 mg crocetin kg1 bw−1 for a 70 kg person.52 The aim of the present study was to investigate at what dose levels bixin and crocetin would be expected to induce PPARγ‐mediated gene expression in humans in vivo by using a combined in vitro‐in silico based testing strategy without the need for a human intervention study. Thus, the present study especially investigated whether dose–response curve for in vivo PPARγ activation in human by bixin and crocetin can be quantitatively predicted by PBK modeling‐facilitated reverse dosimetry of PPARγ activation data obtained in an in vitro PPARγ reporter gene assay.

The results of the in vitro study indicate that both bixin and crocetin can activate PPARγ‐mediated gene expression in U2OS PPARγ2 cells (Figure 3). This observation is in line with earlier reports on PPARγ activation by related carotenoids.18, 19, 20, 21 The results also match the results which reported that branched fatty compounds represent a group of natural PPARγ agonists able to enhance insulin sensitivity of adipocytes.18 The EC50 values for bixin‐ and crocetin‐dependent induction of PPARγ−mediated gene expression in the U2OS PPARγ2 cells were similar indicating a similar intrinsic potency of the carotenoids to induce PPARγ activity. The absence of PPARγ induction by norbixin, the metabolite resulting from hydrolysis of bixin, as observed in the present study is in line with results previously reported by Takahashi et al.,18 who reported that the activity of norbixin for PPARγ activation was substantially lower than that of bixin when tested in the luciferase assay using a chimera protein of PPARγ and the PPAR full‐length system, respectively. Moreover, Roehrs et al.10 found the opposite effect of bixin and norbixin on potentially PPARγ related effects in vivo; where the highest dose of norbixin increased dyslipidaemia and oxidative stress in streptozotocin‐induced diabetes rats, bixin showed an antihyperglycemic effect, improving lipid profiles, and protecting against damage induced by oxidative stress in the diabetic state.

To enable the translation of the in vitro concentration–response curves to in vivo dose–response curves for PPARγ activation by bixin and crocetin, PBK models for bixin and crocetin were developed. Characterization of the model parameters for hepatic clearance revealed that hepatic clearance of crocetin was limited as compared to that observed for bixin. This result explains the observed differences in reported and also in the PBK modeling‐based predicted C max levels for crocetin and bixin in blood at comparable dose levels. The C max values for crocetin were about 10–20 fold higher than those for bixin at comparable dose levels. Furthermore, comparison of the predicted C max values to C max values actually observed in available in vivo kinetic studies in human43, 44 revealed that for both bixin and crocetin these differences were limited. The predicted C max of bixin of 0.027 µm was similar to the reported value of 0.029 µm.43 For crocetin there was only a twofold difference between the PBK model predictions and the reported C max values,44 the predicted values being somewhat too low.

Upon evaluation of the PBK models the available in vitro concentration–response curves for bixin‐ and crocetin‐mediated PPARγ activation were converted to in vivo dose–response curves using PBK modeling‐facilitated reverse dosimetry. The BMD50 and BMDL50‐BMDU50 values derived from the dose–response curves thus obtained were compared to estimated daily intakes for bixin and crocetin resulting from realistic exposure scenarios. These comparisons revealed that EDI values for bixin resulting from its use as a food additive3 or as food supplement49, 50 are unlikely to result in PPARγ‐mediated gene expression in humans. In contrast, use of crocetin‐containing stigma croci at dose levels amounting to 3–9 g per person, estimated to be equivalent to 3.74–11.2 mg crocetin kg bw−1 for a 70 kg person,52 were predicted to more likely result in substantial induction of PPARγ‐mediated gene expression in human. However, it must be noted that the confindence intervals in the predicted dose–response data for crocetin are large and that the BMD50 of the predicted dose–response data is about ten times higher than the intake at therapeutic dose levels. On the other hand, since clearance of crocetin was measured to be negligible in our in vitro studies, crocetin clearance in vivo is expected to be limited as well so that internal concentrations may increase upon daily repeated crocetin intake, resulting in lower predicted effective dose levels.

It is of interest to note that in spite of the intrinsic similar potency of bixin and crocetin to induce PPARγ‐mediated gene expression, as reflected by similar EC50 values in the PPARγ reporter gene assay, the predicted in vivo BMD50 values differed 30‐fold with the value for crocetin being lower. This can be ascribed to the more efficient clearance of bixin than of crocetin, resulting in lower dose levels required to reach effective in vivo C max levels for crocetin than for bixin. This difference in clearance was observed in the in vitro incubations with the primary hepatocytes used in the present study. The few articles reporting on the pharmacokinetics of crocetin in human confirm the inefficient, albeit not negligible, clearance of crocetin.44, 55, 56, 57

The present study used PBK modeling‐based reverse dosimetry converting in vitro data to predicted in vivo dose‐reponse curves enabling definition of effective in vivo dose levels. In previous studies this combined in vitro‐in silico approach appeared already valid for other endpoints including, for example, genistein‐induced estogenicity,36 hesperitin‐induced effects on inhibition of protein kinase A activity,35 azole‐,37 phenol‐,38 retinoic acid,39 and glycol ether‐mediated developmental toxicity,40 and lasiocarpine‐ and riddelliine‐induced liver toxicity.41, 42 The results of the present study illustrate that this combined in vitro‐in silico approach can also be used to obtain insights in human responses to potential functional food ingredients. This insight can be used to select the promising compounds for subsequent human intervention studies and can help in the selection of doses in such studies.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author Contributions

S.S., L.D.H., and A.S. performed the research. S.S., J.L., K.B., and I.M.C.M.R. designed the research study. S.S. and K.B. analyzed the data. S.S., K.B., J.L., I.M.C.M.R., L.D.H., and A.S. wrote and edited the manuscript.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the Indonesian Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP), Ministry of Finance, Republic of Indonesia [grant number: PRJ‐365/LPDP/2016] awarded to S.S.

Suparmi S., de L. Haan, Spenkelink A., Louisse J., Beekmann K., Rietjens I. M. C. M., Combining In Vitro Data and Physiologically Based Kinetic Modeling Facilitates Reverse Dosimetry to Define In Vivo Dose–Response Curves for Bixin‐ and Crocetin‐Induced Activation of PPARγ in Humans. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2020, 64, 1900880 10.1002/mnfr.201900880

References

- 1. Rao A., Rao L., Pharmacol. Res. 2007, 55, 207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Milani A., Basirnejad M., Shahbazi S., Bolhassani A., Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. EFSA , EFSA J. 2019, 17, e05626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mercadante A. Z., Steck A., Pfander H., J. Agric. Food Chem. 1997, 45, 1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. M. J., Scotter , S. A., Thorpe , S. L., Reynolds , L. A., Wilson , P. R., Strutt , Food Addit. Contam. 1994, 11, 301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pfister S., Meyer P., Steck A., Pfander H., J. Agric. Food Chem. 1996, 44, 2612. [Google Scholar]

- 7. IACM , Saffron, https://iacmcolor.org/color-profile/saffron/.

- 8. Hosseinzadeh H., Nassiri‐Asl M., Phytother. Res. 2013, 27, 475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vilar D. D. A., Vilar M. S. D. A., Moura T. F. A. D. L. E., Raffin F. N., Oliveira M. R. D., Franco C. F. D. O., de Athayde‐Filho P. F., Diniz M. D. F. F. M., Barbosa‐Filho J. M., Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 1. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Roehrs M., Figueiredo C. G., Zanchi M. M. E., Bochi G. V., Moresco R. N., Quatrin A., Somacal S., Conte L., Emanuelli T., Int. J. Endocrinol. 2014, 2014, 839095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Xi L., Qian Z., Shen X., Wen N., Zhang Y., Planta Med. 2005, 71, 917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Xi L., Qian Z., Xu G., Zheng S., Sun S., Wen N., Sheng L., Shi Y., Zhang Y., J. Nutr. Biochem. 2007, 18, 64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sheng L., Qian Z., Shi Y., Yang L., Xi L., Zhao B., Xu X., Ji H., Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 154, 1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nathan D. M., Buse J. B., M. B., Davidson , Ferrannini E., Holman R. R., Sherwin R., Zinman B., American Diabetes Association , European Association for Study of Diabetes , Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nesto R. W., Bell D., Bonow R. O., Fonseca V., Grundy S. M., Horton E. S., Le Winter M., Porte D., Semenkovich C. F., Smith S., Young L. H., Kahn R., Circulation 2003, 108, 2941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kintscher U., Law R E., Am. J. Physiol.‐Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 288, E287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Grygiel‐Górniak B., Nutr. J. 2014, 13, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Takahashi N., Goto T., Taimatsu A., Egawa K., Katoh S., Kusudo T., Sakamoto T., Ohyane C., Lee J. Y., Kim Y. I., Uemura T., Hirai S., Kawada T., Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 390, 1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Garcá‐Rojas P., Antaramian A., González‐Dávalos L., Villarroya F., Shimada A., Varela‐Echavarria A., Mora O., J. Anim. Sci. 2010, 88, 1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gijsbers L., van Eekelen H. D. L. M., de Haan L. H. J., Swier J. M., Heijink N. L., Kloet S. K., Man H. Y., Bovy A. G., Keijer J., Aarts J. M. M. J. G., van der Burg B., Rietjens I. M. C. M., J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 3419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Takahashi N., Kawada T., Goto T., Yamamoto T., Taimatsu A., Matsui N., Kimura K., Saito M., Hosokawa M., Miyashita K., Fushiki T., FEBS Lett. 2002, 514, 315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rietjens I. M. C. M., Louisse J., Punt A., Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2011, 55, 941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Louisse J., Beekmann K., Rietjens I. M. C. M., Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2017, 30, 114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. J., Louisse , M., Verwei , R. A., Woutersen , B. J., Blaauboer , I. M. C. M., Rietjens , Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2012, 8, 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. van der Linden S. C., von Bergh A R.M., van Vught‐Lussenburg B M.A., Jonker L R.A., Teunis M., Krul C A.M., van der Burg B., Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2014, 760, 23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gijsbers L., Man H. Y., Kloet S. K., de Haan L. H. J., Keijer J., Rietjens I. M. C. M., van der Burg B., Aarts J. M. M. J. G., Anal. Biochem. 2011, 414, 77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Willson T. M., Cobb J. E., Cowan D. J., Wiethe R. W., Correa I. D., Prakash S. R., Beck K. D., Moore L. B., Kliewer S. A., Lehmann J. M., J. Med. Chem. 1996, 39, 665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McGinnity D. F., Soars M. G., Urbanowicz R. A., Riley R. J., Drug Metab. Dispos. 2004, 32, 1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Soars M. G., Burchell B., Riley R. J., J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002, 301, 382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. R. P., Brown , M. D., Delp , S. L., Lindstedt , L. R., Rhomberg , Beliles R. P., Toxicol. Ind. Health 1997, 13, 407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Berezhkovskiy L. M., J. Pharm. Sci. 2004, 93, 364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rosenbrock H. H., Comput. J. 1963, 5, 329. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Krause A., Lowe P. J., CPT Pharmacometrics Syst. Pharmacol. 2014, 3, e116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Macey R., Oster G., Zahnley T., Berkeley Madonna User's Guide, University of California, Berkely, CA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Boonpawa R., Spenkelink A., Punt A., Rietjens I. M. C. M., Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1600894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Boonpawa R., Spenkelink A., Punt A., Rietjens I. M. C. M., Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li H., Zhang M., Vervoort J., Rietjens I. M.C.M., van Ravenzwaay B., Louisse J., Toxicol. Lett. 2017, 266, 85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Strikwold M., Spenkelink B., de Haan L. H. J., Woutersen R A., Punt A., Rietjens I. M. C. M., Arch. Toxicol. 2017, 91, 2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Louisse J., Bosgra S., Blaauboer B. J., Rietjens I. M. C. M., Verwei M., Arch. Toxicol. 2015, 89, 1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Louisse J., de Jong E., van de Sandt J. J. M., Blaauboer B. J., Woutersen R. A., Piersma A. H., Rietjens I. M. C. M., Verwei M., Toxicol. Sci. 2010, 118, 470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ning J., Chen L., Strikwold M., Louisse J., Wesseling S., Rietjens I. M. C. M., Arch. Toxicol. 2019, 93, 1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chen L., Ning J., Louisse J., Wesseling S., Rietjens I. M.C.M., Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 116, 216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Levy L. W., Regalado E., Navarrete S., Watkins R. H., Analyst 1997, 122, 977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Umigai N., Murakami K., Ulit M. V., Antonio L. S., Shirotori M., Morikawa H., Nakano T., Phytomedicine 2011, 18, 575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Punt A., Freidig A. P., Delatour T., Scholz G., Boersma M. G., Schilter B. T., van Bladeren P. J., Rietjens I. M. C. M., Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2008, 231, 248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Evans M. V., Toxicol. Sci. 2000, 54, 71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gülden M., Seibert H., Toxicology 2003, 189, 211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. EFSA‐Scientific‐Committee , Hardy A., Benford D., Halldorsson T., Jeger M. J., Knutsen K. H., More S., Mortensen A., Naegeli H., Noteborn H., Ockleford C., Ricci A., Rychen G., Silano V., Solecki R., Turck D., Aerts M., Bodin L., Davis A., Edler L., Gundert‐Remy U., Sand S., Slob W., Bottex B., Abrahantes J. C., Marques D. C., Kass G., Schlatter J. R., EFSA J. 2017, 15, e04658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Conte L., Somacal S., Nichelle S. M., Rampelotto C., Robalo S. S., Roehrs M., Emanuelli T., J. Nutr. Metab. 2019, 2019, 9407069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Roehrs M., Conte L., da Silva D. T., Duarte T., Maurer L. H., de Carvalho J. A. M., Moresco R. N., Somacal S., Emanuelli T., Food Res. Int. 2017, 100, 771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. JECFA , Safety evaluation of certain food additives and contaminants: prepared by the Seventy seventh meeting of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA), http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43645/1/9789241660587_eng.pdf.

- 52. WHO , WHO Monographs on Selected Medicinal Plants, Volume 3, https://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s14213e/s14213e.pdf.

- 53. Anastasaki E. G., Kanakis C. D., Pappas C., Maggi L., Zalacain A., Carmona M., Alonso G. L., Polissiou M. G., J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 6011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sluijs I., Cadier E., Beulens J. W. J., van der A D. L., Spijkerman A. M. W., van der Schouw Y. T., Nutr., Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2015, 25, 376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lautenschläger M., Sendker J., Hüwel S., Galla H. J., Brandt S., Düfer M., Riehemann K., Hensel A., Phytomedicine 2015, 22, 36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mizuma H., Tanaka M., Nozaki S., Mizuno K., Tahara T., Ataka S., Sugino T., Shirai T., Kajimoto Y., Kuratsune H., Kajimoto O., Watanabe Y., Nutr. Res. 2009, 29, 145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Chryssanthi D. G., Lamari F. N., Georgakopoulos C. D., Cordopatis P., J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2011, 55, 563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information