Abstract

The metabolome is a system of small biomolecules (metabolites) and a direct result of human bioculture. Consequently, metabolomics is well poised to impact anthropological and biomedical research for the foreseeable future. Overall, we provide a perspective on the ethical, legal, and social implications (ELSI) of metabolomics, which we argue are often more alarming than those of genomics. Given the current mechanisms to fund research, ELSI beyond human DNA is stifled and in need of considerable attention.

1. INTRODUCTION

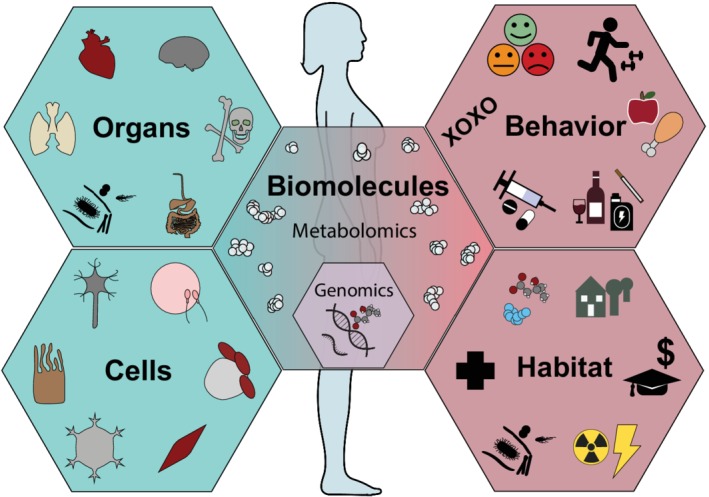

The metabolome, the totality of small molecules in a biological system (Wishart et al., 2017), is arguably the most impactful biological subsystem for health and wellness, given its central role in biochemistry (Patti, Yanes, & Siuzdak, 2012). Although DNA forms a foundation for biology, the action of molecular biology is happening above the genome. Whether referring to the molecular interactions occurring endogenously (from the genome and among the cells and organs) or exogenously (from behavioral and environmental chemical exposures), the metabolome is the highly dynamic molecular system that serves at the nexus (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The metabolome serves as the nexus of the interacting systems that shape health

The metabolome is the molecular system most proximal to phenotype (the observable characteristics of an organism) and metabolomics is exciting because it brings knowledge of mechanisms to health and human biology. For example, translation of metabolomics knowledge into treatments may be more straightforward than the human genome because most drugs are themselves metabolite inspired, small molecule agonists, or antagonists of signaling cascades and metabolism (O′Hagan, Swainston, Handl, & Kell, 2015). Given the key role of small molecules at the intersection of cultural, biological, and environmental systems, metabolomics has a unique potential in a personalized medicine framework; the metabolome is the biomolecularly realized manifestation of the social determinates of health. Metabolomics builds off of a 100+ year legacy of characterizing biochemical pathways, products, and reaction intermediates (classic metabolites), laying the foundation of the vast majority of biotechnological advances, including nearly all current pharmaceuticals, pesticides, and vital nutrients (German, Hammock, & Watkins, 2005). Using new tools, expanding chemical libraries, and integrating with other forms of big data, metabolomics has entered a golden era of discovery, and well deserves a central place in anthropological and biological research programs, federal funding initiatives, and institutes.

Metabolomics initially focused on cellular metabolic pathways. Driven by technological advances, a broader definition is gaining acceptance, emphasizing all “omics”‐scale research on small molecules (<1,500 Da) (Wishart et al., 2017). Consequently, metabolomics research, compared to other “omics” sciences, encompasses a broad range of structurally diverse molecules from microbiome secondary metabolites and food‐derived molecules to xenobiotics (Wishart et al., 2017). Thus, metabolomics can be considered an umbrella discipline including a wide range of studies, such as lipidomics, exposomics, fluxomics, which are deeply connected by scientific theory, protocols, standards, methods, and frequently, ethical, legal, and social implications (ELSI).

2. METABOLOMICS AND ANTHROPOLOGY

The human metabolome is a direct result of human bioculture, including human practices and the environment; thus, biological anthropology is well situated to engage the metabolome. Yet, metabolomics in anthropology has yet to solidify an identity. Anthropological publications that directly refer to, or study, the metabolome are most frequently associated with studies of the human microbiome (Crittenden & Schnorr, 2017; Pafco et al., 2019; Sankaranarayanan et al., 2015; Stumpf et al., 2013); however, the metabolome and metabolites encompass much more of human biology than that attributed to microbial ecologies. In fact, while metabolites are molecular, they are often nongenetic, revealing a form of nongenetic molecular anthropology. Within archeology, an explicit metabolomic characterization of ancient materials has begun (Velsko et al., 2017). Yet, archeological approaches to metabolomics have been around awhile; they may be concealed under a broader objective of “residue analysis,” revealing remarkable discoveries of human cultural practices through metabolites (e.g., Crown et al., 2015).

3. HEALTH, THE GENOME VERSUS THE METABOLOME

The 100+ year legacy of metabolite science suggests that metabolomics is poised to have a greater claim to success in medicine than genomics. The genome remains significant, to be sure, in that it transcends the health of the individual and reflects the history and potential future of our species. Moreover, genomic variation has demonstrated a level of predictive power for some diseases and health risks, although the predictive power of the genome alone may be limited for complex diseases (Roberts et al., 2012).

Most aspects of health and disease are complex, not directly attributable to genes. Even considering emerging excitement and concerns with CRISPR (Adli, 2018) and other gene editing technologies, these gene‐based approaches will likely remain less relevant than the vast array of metabolite‐based interventions that impact our life. One common misconception of genomics is that the combination of the genome, transcriptome, and proteome determines function, phenotype, and health; however, with respect to much biomolecular activity, the system of gene expression is subordinate to the substrates, products, and other modifiers involved in metabolic activity (ter Kuile & Westerhoff, 2001). Thus, even with perfect data on gene expression, this information still only conveys what might happen during a metabolic process; in contrast, information from the metabolome uncovers what is actually happening (Riekeberg & Powers, 2017).

4. ELSI AND THE METABOLOME

Published research on the ELSI of metabolomics is essentially nonexistent, although it may be mentioned in brief when referencing genomics or related fields (see, e.g., Manasco, 2005). In two broad areas, metabolomics has fewer ethical concerns: on average, (a) metabolomic data are less ancestry informative; (b) metabolites are a more dynamic system than genes and gene products, so our current metabolome profile is less fixed than our germline profile, creating more opportunities for intervention. Also, some ethical issues in genomics have analogues in metabolomics and can serve as foundations. But there are other areas where differences are substantial, and genomic foundations are unlikely to provide direct solutions to metabolomics ELSI. We highlight these in the following.

4.1. Privacy

The potential loss of personal privacy from the metabolome is greater than most realize. The metabolome is shaped by where you live and what you do, and consequently contains information on your environment and your practices; drugs, diet, and various environmental exposures are traceable in the metabolome. Aspects of your behavior, your practices, your biology, are not only impacting the metabolome in your body, but the metabolites you leave behind. Your metabolome can be characterized from your kitchen or bedroom, your keyboard at home or work (Bouslimani et al., 2015; Bouslimani et al., 2016;McCall et al., 2019 ; Petras et al., 2016). Indeed, metabolites left on phones can be used to build a behavioral profile of the phones' owner, and even to match them back together (Bouslimani et al., 2016). The metabolome is therefore a molecular fingerprint different from DNA, but equally impactful, and more so if the objective is to understand human actions rather than human ancestry.

Health and the built environment are deeply tied (Perdue, Stone, & Gostin, 2003). Metabolomics is poised to make significant contributions to this area of research (Athersuch, 2016), but not without some major concerns for privacy, misinterpretation, and misuse of results. Visualizations of the molecules of the built environment not only reveal an individual's contact with their habitat, and the habitat's impact on the individual, but also the diffusion of a chemical material culture within the habitat, such as sanitizers, medication, personal care products, foods, drinks, and their additives (McCall et al., 2019; Petras et al., 2016). The chemical tracing of behavior, from the individual's behaviors to the history of an item, has major implications for a range of sciences, and certainly for ethics. One of the more profound examples is the presence of cocaine in the built environment. It has been observed that most banknotes in circulation in the United States carry detectable levels of cocaine (Zuo, Zhang, Wu, Rego, & Fritz, 2008). As proof of principle, one study applied untargeted metabolomics to reveal the behavior in an apartment (Petras et al., 2016), including associated belongings; unsurprisingly, cocaine was detected although none was used by the occupants. Many metabolites are “sticky” and can be found on objects months later (Bouslimani et al., 2016). Detection of such molecules may not reflect a person's current behavior, but rather their actions 6 months ago or the actions of a previous owner of the object. Preventing misinterpretation and overinterpretation of such findings will be a major concern that intersects privacy, exposomics, and health; policies to protect privacy and human rights with the rise of metabolomics are needed. We should be prepared for a world where molecular tools threaten personal privacy in ways that are difficult to appreciate fully today.

4.2. Policy

The United States Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) of 2008 is a federal law that provides some protections to those using genetic tests or family history to learn about their health risks; health insurers and employers are unable to request, require, or use this genetic information to discriminate. The only metabolites specifically covered under this law are those that directly predict genotypes, mutations, or chromosomal changes. Any other metabolites are excluded from these protections. For example, GINA does not cover current health conditions and specifically excludes metabolites that are directly related to a “manifested disease, disorder, or pathological condition that could reasonably be detected”. This legal condition is problematic in metabolomics. Genetic mutations in one enzyme often affect the direct product of that enzyme, but through cascade effects almost certainly affect the downstream metabolic products, plus any pathways regulated by downstream products, and the cells' compensatory mechanisms. Moreover, the vast majority of health‐associated metabolites are uninformative of genetic variation. In other words, at this time, there are no protections for most health‐ and behavior‐associated metabolites. This is a distinct privacy risk from other nongenetic health information, such as weight and medicine use, because the metabolome is all encompassing, not targeted, and there are no guidelines currently for delineating that which is relevant and reasonable for insurers from that which needs further protection from discrimination.

4.3. Intellectual property

Metabolomics‐based biomarker tests are patentable, for example, the U.S. company Metabolon holds over 30 U.S. patents on biomarkers and biomarker identification methods, covering diseases such as atherosclerosis, diabetes, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, cancer, with additional applications to the study of drug mechanism of action, response to drugs, and the link between gene expression and metabolite production (Gall, Cobb, & Pappan, 2018; Hu et al., 2019; Kaddurah‐daouk & Kristal, 2006; Mitchell, Berger, Lawton, & Beecher, 2013; Paige et al., 2014). Patenting specific metabolites for treatment purposes may be more challenging. For metabolites present in nature and already structurally described, only patents covering method of use or production processes would be possible. Nevertheless, chemical modification may be straightforward and lead to derived patentable novel chemical matter (Kartal, 2007), which raises questions on who owns a trivially modified, but otherwise ubiquitous, metabolite.

4.4. Naïve use of race

Metabolomics is a new opportunity to conflate race and biology. Although the complexities of race, identity, genetics, and health have been the thesis of many publications, we know of no focused discussions on the metabolome. We can expect a large pool of biochemist with little exposure to such issues as their field, unlike genomics, has largely been removed from the narrative. Yet through metabolomics, racial/ethnic groups will be stereotyped and compartmentalized in ways that speak more to the worldview of the researcher than the elastic bioculture of people. In fact, attempts at identifying race‐specific metabolomic biomarkers have begun (Di Poto et al., 2018; Shi, Yuan, Zhang, Feng, & Wang, 2019), and while these studies are drafted to improve clinical practice for diverse people, the framing of the problem is naïve to genetic and cultural diversity. Without question, genetic ancestry and cultural practices impact biology and health, and coassociate with culturally constructed racial groups, to various degrees. Even so, the use of race or ethnicity as the primary focus of research is rarely warranted (Berg et al., 2005). Although ethnicity or racial identifications can have utility in study designs, especially with regard to inclusion of diversity, culturally constructed racial groups are merely proxies, often poor, for the underlying genomic and cultural/environmental variables that directly impact health. To have precision, the wiser approach is not to invent individual tests for races but individual tests for individuals. So much of metabolomics is shaped by practices, and the environment that the construction of race‐specific assays creates an unreliable rigidity of people.

4.5. Disparities

The data available to science shape future science. Naturally, this advocates for efforts to include diverse groups within science to avoid reinforcing disparities. Yet, the impact of new and emerging sciences is less understood and may expose participants to unpredicted risks. These risks maybe more challenging to mitigate in socioeconomically vulnerable populations compared with the general public. This is the most universal protection dilemma impacting health disparities among underrepresented groups. How do we give people the equal potential for benefit, while mitigating potential risks, especially for the more vulnerable? This is a challenging question for ELSI and metabolomics that intersects and exacerbates all the above concerns of the ethical handling of metabolomic data.

Intersecting race and disparities includes appeals to environmental justice, as built environments in more impoverished areas are likely to provide tangible evidence of disproportionate environmental toxins relative the more affluent areas. Claims based on metabolomics will need careful review, which also includes issues of social justice, privacy, and racial disparities.

4.6. Funding and future

Support for ELSI research grew directly out of the National Institutes of Health (NIH, 2019) Human Genome Project, and continues to be overseen as an extramural research program in the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI). Over the past three decades, this funding mechanism has become the primary source of U.S. extramural funding for biomedical ethics. Not surprisingly, the majority of ELSI research proposals focus on genome research and clinical applications of genetic testing. Unfortunately, this emphasis is out of step with the multi‐omics revolution in the life sciences that has followed in the wake of the human genome project. Armed with new insights and tools from genomics, a wide array of biological fields are studying synergistic connections among biological pathways and phenomena—and importantly, focusing their efforts on the system of biomolecules above the genome that are much more amenable to intervention, such as the metabolome.

NHGRI's consistent focus on human genetics has allowed ELSI researchers to develop new strategies to understand genetics, evaluate the benefits of genetic testing, and propose health policy that maximizes promise while minimizing harms (Burke et al., 2015). But a consequence of this focus is a preoccupation with what is arguably the least clinically actionable biomolecule, human DNA. It seems clear that we need a broader ELSI program that is more responsive to, and inclusive of, how biology works and how human biology is studied today. Given that omics sciences are expanding rapidly, the need for broad institutional recognition, identity, and investment in these sciences is critical.

The solution to improving support and awareness of ELSI and biomolecules is not simply broadening the scope of NHGRI (although that would help), but also requires a commitment from other agencies, organizations and institutions, including those within anthropology. Professional societies, particularly those close to biological anthropology, can be doing their part in creating professional awareness—that molecular anthropology is not just about human DNA—and that the implications of molecules are broader than ancestry, population history, and evolution. Many of these issues would benefit from attention from other NIH institutes, which often have minimal explicit investment in anything that resembling ELSI, as well as outside NIH altogether, falling more within the purview of other agencies (e.g., NSF) and foundations. The rise of these new approaches requires, in our opinion, a much more sustained and coordinated approach to engage the kind of issues we have anticipated here.

5. CONCLUSIONS

If the past 100+ years of history is any indication, metabolites will lead health detection and treatment discoveries for the foreseeable future, and with the advent of metabolomic scale research, there is hope that the momentum in drug discovery has a new catalyst. High‐impact discoveries like this, that are paradigm shifting in science and life changing in medicine and society, do not come often. They require deep commitment, sacrifice, and often abundant failure and misdirection, which will only be exacerbated if fear of research reduces participation by individuals, groups, and nations. At this time, there is a reason for all to be concerned about the ELSI of metabolomics. To pave a safer and productive path, there is a need for increased investment in the ELSI above the genome, by institutes, by agencies, and by professional organizations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This publication was primarily supported by the NIH (RM1 HG009042; R01 GM089886). We thank helpful comments from Morris Foster (Old Dominion University), Aaron Goldenberg (Case Western Reserve University), the Center on the Ethics of Indigenous Genomic Research, Laboratories of Molecular Anthropology and Microbiome Research.

Lewis CM Jr, McCall L‐I, Sharp RR, Spicer PG. Ethical priority of the most actionable system of biomolecules: the metabolome. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2020;171:177–181. 10.1002/ajpa.23943

Funding information National Human Genome Research Institute, Grant/Award Number: RM1 HG009042; National Institute of General Medical Sciences, Grant/Award Number: R01 GM089886

REFERENCES

- Adli, M. (2018). The CRISPR tool kit for genome editing and beyond. Nature Communications, 9(1), 1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athersuch, T. (2016). Metabolome analyses in exposome studies: Profiling methods for a vast chemical space. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics, 589, 177–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg, K. , Bonham, V. , Boyer, J. , Brody, L. , Brooks, L. , Collins, F. , et al. (2005). The use of racial, ethnic, and ancestral categories in human genetics research. American Journal of Human Genetics, 77(4), 519–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouslimani, A. , Melnik, A. V. , Xu, Z. , Amir, A. , da Silva, R. R. , Wang, M. , … Dorrestein, P. C. (2016). Lifestyle chemistries from phones for individual profiling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(48), E7645–E7654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouslimani, A. , Porto, C. , Rath, C. M. , Wang, M. , Guo, Y. , Gonzalez, A. , et al. (2015). Molecular cartography of the human skin surface in 3D. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(17), E2120–E2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke, W. , Appelbaum, P. , Dame, L. , Marshall, P. , Press, N. , Pyeritz, R. , … Juengst, E. (2015). The translational potential of research on the ethical, legal, and social implications of genomics. Genetics in Medicine, 17(1), 12–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden, A. N. , & Schnorr, S. L. (2017). Current views on hunter‐gatherer nutrition and the evolution of the human diet. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 162(63), 84–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crown, P. L. , Gu, J. , Hurst, W. J. , Ward, T. J. , Bravenec, A. D. , Ali, S. , et al. (2015). Ritual drinks in the pre‐Hispanic US southwest and Mexican northwest. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(37), 11436–11442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Poto, C. , He, S. , Varghese, R. S. , Zhao, Y. , Ferrarini, A. , Su, S. , et al. (2018). Identification of race‐associated metabolite biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with liver cirrhosis and hepatitis C virus infection. PLoS One, 13(3), e0192748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gall, W. , Cobb, J. E. , & Pappan, K. L. (2018). Biomarkers related to insulin resistance progression and methods using the same. Durham, NC: Metabolon. [Google Scholar]

- German, J. B. , Hammock, B. D. , & Watkins, S. M. (2005). Metabolomics: Building on a century of biochemistry to guide human health. Metabolomics, 1(1), 3–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y. F. , Chirila, C. , Alexander, D. , Milburn, M. , Mitchell, M. W. , Gall, W. , & Lawton, K. A. (2019). Biomarkers for cardiovascular diseases and methods using the same. Durham, NC: Metabolon. [Google Scholar]

- Kaddurah‐daouk, R. , & Kristal, B. S. (2006). Methods for drug discovery, disease treatment, and diagnosis using metabolomics. Research Triangle Park, NC: Metabolon. [Google Scholar]

- Kartal, M. (2007). Intellectual property protection in the natural product drug discovery, traditional herbal medicine and herbal medicinal products. Phytotherapy Research, 21(2), 113–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manasco, P. K. (2005). Ethical and legal aspects of applied genomic technologies: Practical solutions. Current Molecular Medicine, 5(1), 23–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall, L.‐I. , Anderson, V. , Fogle, R. , Haffner, J. , Hossain, E. , Liu, R. , … Yao, S. (2019). Analysis of university workplace building surfaces reveals usage‐specific chemical signatures. Building and Environment, 162, 106289. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, M. W. , Berger, A. , Lawton, K. A. , & Beecher, C. (2013). Biomarkers for prostate cancer and methods using the same. Durham, NC: Metabolon. [Google Scholar]

- NIH . 2019. NHGRI fiscal year 2019 justification of estimates for congressional appropriations committee. NIH National Human Genome Research Institute. https://www.genome.gov/about-nhgri/Budget-Financial-Information. [Google Scholar]

- O′Hagan, S. , Swainston, N. , Handl, J. , & Kell, D. B. (2015). A “rule of 0.5” for the metabolite‐likeness of approved pharmaceutical drugs. Metabolomics, 11(2), 323–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pafco, B. , Sharma, A. K. , Petrzelkova, K. J. , Vlckova, K. , Todd, A. , Yeoman, C. J. , et al. (2019). Gut microbiome composition of wild western lowland gorillas is associated with individual age and sex factors. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 169(3), 575–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paige, L. A. , Mitchell, M. W. , Evans, A. , Harvan, D. , Lawton, K. A. , Brown, R. , & Cudkowicz, M. (2014). Biomarkers for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and methods using the same. Durham, NC: Metabolon. [Google Scholar]

- Patti, G. J. , Yanes, O. , & Siuzdak, G. (2012). Innovation: Metabolomics: The apogee of the omics trilogy. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 13(4), 263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdue, W. C. , Stone, L. A. , & Gostin, L. O. (2003). The built environment and its relationship to the public's health: The legal framework. American Journal of Public Health, 93(9), 1390–1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petras, D. , Nothias, L. F. , Quinn, R. A. , Alexandrov, T. , Bandeira, N. , Bouslimani, A. , et al. (2016). Mass spectrometry‐based visualization of molecules associated with human habitats. Analytical Chemistry, 88(22), 10775–10784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riekeberg, E. , & Powers, R. (2017). New frontiers in metabolomics: From measurement to insight. F1000Res, 6, 1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, N. J. , Vogelstein, J. T. , Parmigiani, G. , Kinzler, K. W. , Vogelstein, B. , & Velculescu, V. E. (2012). The predictive capacity of personal genome sequencing. Science Translational Medicine, 4(133), 133ra158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankaranarayanan, K. , Ozga, A. T. , Warinner, C. , Tito, R. Y. , Obregon‐Tito, A. J. , Xu, J. , et al. (2015). Gut microbiome diversity among Cheyenne and Arapaho individuals from Western Oklahoma. Current Biology, 25(24), 3161–3169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, H. , Yuan, J. , Zhang, Y. , Feng, S. , & Wang, J. (2019). Discovering significantly different metabolites between Han and Uygur two racial groups using urinary metabolomics in Xinjiang, China. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis, 164, 481–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stumpf, R. M. , Wilson, B. A. , Rivera, A. , Yildirim, S. , Yeoman, C. J. , Polk, J. D. , … Leigh, S. R. (2013). The primate vaginal microbiome: Comparative context and implications for human health and disease. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 152(Suppl 57), 119–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ter Kuile, B. H. , & Westerhoff, H. V. (2001). Transcriptome meets metabolome: Hierarchical and metabolic regulation of the glycolytic pathway. FEBS Letters, 500(3), 169–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velsko, I. M. , Overmyer, K. A. , Speller, C. , Klaus, L. , Collins, M. J. , Loe, L. , et al. (2017). The dental calculus metabolome in modern and historic samples. Metabolomics, 13(11), 134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart, D. S. , Feunang, Y. D. , Marcu, A. , Guo, A. C. , Liang, K. , Vazquez‐Fresno, R. , et al. (2017). HMDB 4.0: The human metabolome database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Research, 46(D1), D608–D617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, Y. , Zhang, K. , Wu, J. , Rego, C. , & Fritz, J. (2008). An accurate and nondestructive GC method for determination of cocaine on US paper currency. Journal of Separation Science, 31(13), 2444–2450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]