Abstract

A major handicap towards the exploitation of radicals is their inherent instability. In the paramagnetic azafullerenyl radical C59N., the unpaired electron is strongly localized next to the nitrogen atom, which induces dimerization to diamagnetic bis(azafullerene), (C59N)2. Conventional stabilization by introducing steric hindrance around the radical is inapplicable here because of the concave fullerene geometry. Instead, we developed an innovative radical shielding approach based on supramolecular complexation, exploiting the protection offered by a [10]cycloparaphenylene ([10]CPP) nanobelt encircling the C59N. radical. Photoinduced radical generation is increased by a factor of 300. The EPR signal showing characteristic 14N hyperfine splitting of C59N.⊂ [10]CPP was traced even after several weeks, which corresponds to a lifetime increase of >108. The proposed approach can be generalized by tuning the diameter of the employed nanobelts, opening new avenues for the design and exploitation of radical fullerenes.

Keywords: azafullerenes, [10]cycloparaphenylene, host–guest complexes, long-lived radicals, photoinduced radical generation

A radical shielding approach based on supramolecular complexation exploits the protection offered by a [10]cycloparaphenylene ([10]CPP) nanobelt encircling C59N. to stabilize this radical. The EPR signal of C59N.⊂[10]CPP showing characteristic 14N hyperfine splitting was observed even several weeks after its generation.

Introduction

Charge transfer processes occurring in fullerene‐based molecular materials1, 2 have highlighted the importance of fullerene radicals for diverse applications, most notably in spintronics3, 4, 5 as well as energy conversion6, 7, 8 and storage.9 The most explored fullerene C60 radicals, C60 .+,10 C60 .−,11, 12, 13 and C60 .3−,14, 15 are typically transient or labile short‐lived species in air, whereas the paramagnetic C59N. radical, which is mostly exploited for the chemical functionalization of the heterofullerene cage,16, 17 instantly dimerizes to diamagnetic (C59N)2.18 In C59N. the unpaired electron resides on a tertiary carbon atom located on a concave surface, and thus it is exposed to the outer environment of the cage. Evidently, commonly explored molecular design strategies based on the incorporation of bulky substituents to generate a protecting environment around flat C(sp2)‐centered radicals are not applicable in this case.19, 20 Diffusion of sublimed C59N. radicals into single‐walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) was tested as a potential approach to handle these species; however, the rapid rotational and translational motion of the encapsulated species promotes dimerization and depletion of the radicals on a rather short timescale.21

Herein, we present a new strategy for stabilizing fullerene radicals based on a supramolecular approach. Highly reactive C59N. radicals can be shielded by nesting them in carbon nanobelts consisting of single phenyl units connected in para position—cycloparaphenylenes (CPPs).22, 23, 24 These convex molecules have been explored for fullerene complexation and the study of photoinduced phenomena.25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 Our approach takes advantage of 1) the 1.4 nm cavity of [10]CPP, resembling the inner space of carbon nanotubes favoring π–π host–guest interactions, to accommodate a C59N. radical (Figure 1 a), 2) the diminished environmental exposure of the radical resulting from the favorable orientation of the CPPs close to the exposed radical, and 3) the well‐established chemistry of C59N., which prevents chemical addition to 1,4‐substituted phenylenes because of steric hindrance.16, 32 We show that supramolecular complexation of C59N. by a [10]CPP nanobelt effectively shields the unpaired electron and blocks dimerization, resulting in the stable formation of unprecedentedly long‐lived azafullerenyl radical species.

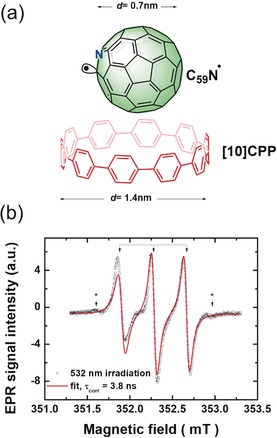

Figure 1.

a) The [10]CPP host and the C59N. guest species. b) Room‐temperature X‐band EPR spectrum of C59N.⊂[10]CPP in 1‐chloronaphthalene as formed upon irradiation at 532 nm (open circles). The solid red line is a fit of the experimental spectrum to a model that assumes slow isotropic rotation of C59N.⊂[10]CPP, yielding a rotational diffusion correlation time of τ corr=3.8 ns. Parameters used in the fit: The eigenvalues of the g‐factor tensor are gxx=2.0010, gyy=1.9993, and gzz=2.0042, while the 14N hyperfine tensor eigenvalues are Axx=1.6 MHz, Ayy=15.9 MHz, and Azz=14.9 MHz. The three arrows on top of the spectrum indicate the main 14N hyperfine splitting of the EPR spectrum, whereas the two weaker signals, probably originating from the additional hyperfine splitting with 13C in its natural abundance, that flank the main triplet of lines are marked with *.

Results and Discussion

Α mixture of [10]CPP and (C59N)2 in a 2:1 molar ratio in 1‐chloronaphthalene was stirred for 8 h to allow the effective complexation of the individual species and to reach equilibrium.31 Upon continuous illumination (λ=532 nm) of the solution, an electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) signal composed of three equidistant lines appeared (Figure 1 b). Such a spectrum is a hallmark of 14N hyperfine interactions with an unpaired electron, highlighting the occurrence of EPR‐active C59N.. The average g‐factor of this signal is g =2.0014, whereas the splitting between pairs of these three lines of 0.38 mT corresponds to the 14N hyperfine interaction a N=10.7 MHz. Both the g and a N values match almost perfectly with values deduced earlier for the C59N. radical in solution33, 34 or in powder,35 thus unambiguously demonstrating the formation of paramagnetic C59N. in the presence of [10]CPP nanobelts (Figure 2 a). Careful inspection of the EPR signal revealed the presence of two additional peaks that symmetrically flank the main spectrum on the low‐ and high‐field sides. The splitting to the main lines corresponds to about 0.3 mT, which is a typical value for the hyperfine coupling to the 13C sites next to the N site of C59N.36 The weakness of these peaks arises solely from the low natural abundance of the 13C isotope.

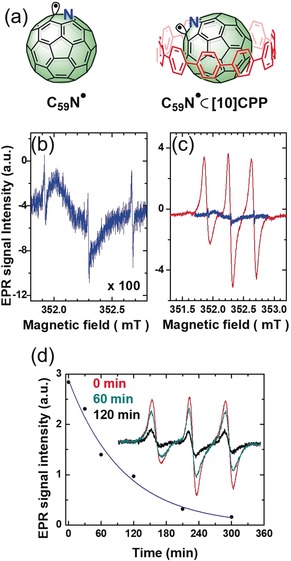

Figure 2.

a) Structures of C59N. and C59N.⊂[10]CPP radicals. b) The X‐band EPR spectrum of bare C59N. in 1‐chloronaphthalene solution. c) Comparison of the solution X‐band EPR spectra of C59N.⊂[10]CPP (red) and C59N. (blue). All measurements were conducted at room temperature in degassed 1‐chloronaphthalene with samples possessing equal concentrations (2.3 mm). d) Time dependence of the X‐band EPR signal of C59N.⊂[10]CPP in 1‐chloronaphthalene after the illumination at 532 nm has been switched off. The solid blue line is a fit to an exponential time decay yielding the characteristic decay of 100 min. Inset: Comparison of spectra recorded during illumination (red), 60 min after switching off the light (cyan), and 120 min after switching off the light (black).

In contrast, the reference EPR spectrum of bare (C59N)2 in 1‐chloronaphthalene (Figure 2 b), at exactly the same concentration and measured under the same experimental conditions, shows some striking and important differences. The first obvious dissimilarity is in the normalized intensity of the EPR signals; for the 1‐chloronaphthalene solution of (C59N)2, the corresponding signal (Figure 2 c) is about 300 times stronger in the presence of [10]CPP than without it. Evidently, [10]CPP protects the photogenerated C59N. against direct recombination, a process that is otherwise unavoidable.37 The time decay of the EPR signal after switching off the light irradiation further demonstrates quantitatively the shielding mechanism. For bare (C59N)2, the EPR signal disappears so quickly after irradiation that it is impossible to measure the radical lifetime by continuous‐wave EPR spectroscopy. This observation is in complete agreement with the literature data.38 On the other hand, the EPR signal for the solution containing the C59N.⊂[10]CPP complex can still be easily traced even after the light illumination has been switched off for 120 min (inset in Figure 2 d). The decay of the EPR signal in the dark shows a simple exponential time dependence reflecting a characteristic decay time of the signal of τ=100 min (Figure 2 d). Markedly, the triplet EPR signal is observed even after 300 min, with decreased intensity (see the Supporting Information, Figure S1), and traces thereof were still detected after a couple of weeks. The second remarkable difference is in the linewidths of the EPR signal; the peak‐to‐peak linewidth of the central line for C59N.⊂[10]CPP is 0.068 mT, whereas it amounts to only 0.011 mT for the bare C59N. radicals. The increase in the linewidth directly manifests the presence of [10]CPP wrapping and protecting the azafullerenyl radical in C59N.⊂[10]CPP by affecting the radical dynamics. In the case of fast complex rotations (for the X‐band EPR spectra, the characteristic correlation time is much shorter than 10−9 s) the anisotropies in the magnetic interactions are fully averaged out, and the 14N hyperfine split EPR spectrum is simply represented as a superposition of three equidistant sharp Lorentzian lines of equal intensity. Such a fast motional limit applies to irradiated (C59N)2 in 1‐chloronaphthalene33, 34 or even to C59N. created in powder by thermolysis at high temperature.35, 38, 39

For C59N.⊂[10]CPP, the anisotropies are only partially averaged out by the various types of rotational dynamics of the radical in solution: the fast anisotropic rotation of C59N. within [10]CPP or the rotation of the entire C59N.⊂[10]CPP species in 1‐chloronaphthalene. The increased hydrodynamic radius of C59N.⊂[10]CPP considerably slows down its rotational dynamics in 1‐chloronaphthalene. Thus, the rotational dynamics of the entire C59N.⊂[10]CPP complex has the largest effect on the EPR spectrum. EPR lineshape simulations assuming isotropic C59N.⊂[10]CPP reorientations in the slow‐motion limit (Figure 1 b) yield a rather long correlation time of τ corr=3.8 ns at room temperature. The slight residual discrepancy between the measured and simulated spectra might arise from the presence of a weak defect featureless signal (Figure S2), present with the complex prior to illumination,40 and from the anisotropy of faster C59N. reorientations inside the [10]CPP belt, which was not taken into account in the simulation. Nevertheless, we can conclude that the presence of [10]CPP is critical for slowing down the C59N. rotational dynamics, affording the surprisingly long‐lived EPR signal of C59N.⊂[10]CPP.

We also measured EPR spectra between room temperature and 195 K. A typical X‐band continuous‐wave EPR spectrum measured at 220 K is shown in Figure S3. Assuming the same model of slow isotropic rotations as the one used for the room‐temperature spectrum, we obtained a correlation time for the rotations of τ rot=15 ns, which is about five times longer than that at room temperature. The aforementioned experimental approach allowed us to also employ pulsed EPR techniques. The Fourier transform of the free‐induction‐decay signal is shown in Figure S4 a, where the 14N hyperfine splitting of the three peaks of ±10.5 MHz is clearly visible. No attempts towards line‐shape fitting were made in this case because of the final excitation bandwidth of the π/2=16 ns excitation pulse. On the other hand, pulsed experiments enabled us to directly measure the spin–lattice relaxation rates 1/T 1 by using the inversion recovery method (Figure S4 b). 1/T 1 driven by the molecular dynamics can be expressed as 1/T 1=Aτ rot/[1+(ω e τ rot)2], where ω e is the Larmor angular frequency and A is the magnitude of the field fluctuations. This expression predicts that 1/T 1 has a maximum at ω e τ rot=1, which in our case must be at temperatures higher than room temperature. Therefore, our initial assumption of a slow rotation limit is fully justified. The next important lesson from those measurements is that the freezing of the solvent at around 230 K has a pronounced effect on the dynamics of the C59N. radical as 1/T 1 shows a plateau in this temperature range.

After light illumination, the decay of the EPR signal was accompanied by the precipitation of an EPR‐silent dark green solid, increasing proportionally to the concentration of the solution. The precipitate was filtered off and found to be fully soluble in CD2Cl2. Complementary 1H NMR studies showed the presence of one set of aromatic protons at δ=7.62 and 7.48 ppm, assigned to (C59N)2⊂[10]CPP, together with protons due to free [10]CPP at δ=7.56 ppm in a 1:1 ratio (Figure S5). This observation supports the conclusion that the green solid formed during the decay of C59N.⊂[10]CPP in 1‐chloronaphthalene is the insoluble 2:1 complex [10]CPP⊃(C59N)2⊂ [10]CPP.

DFT calculations show that the most stable orientation for the C59N. radical within [10]CPP features the nitrogen atom and its neighbouring carbon radical facing H atoms of the [10]CPP. The spin distribution of C59N. is almost unperturbed by the presence of [10]CPP (Figure S6). We calculated the isotropic hyperfine coupling parameter A iso between the unpaired electron spin and the 14N nuclear spin in isolated C59N. to be 10.92 MHz, which is in excellent agreement with our experiment (10.7 MHz), while A iso with the two back‐bonded 13C nuclear spins is 3.46 MHz. In the presence of [10]CPP these values shift slightly to 9.97 and 3.21/3.75 MHz (Table S1). The calculated energy barrier for rotation of C59N. within [10]CPP, while maintaining the N atom beneath the ring, is less than 0.2 eV. This is below the 290 meV reorientation barrier for C60 in pristine solid C60 41 and suggests that there should be rapid relative rotation of the two species at room temperature, contributing to the observed EPR line broadening. Critically, the [10]CPP covers and protects the radical from chemical attack. We calculated an energy difference of 0.28 eV between the stable complex and a rotated structure where N and neighbouring radical are exposed facing away from the [10]CPP. Weighing these two energies by the relative surface areas of exposed and protected orientations of the C59N. to create a partition function suggests that the radical will occupy exposed orientations only 0.001 % of the time, that is, collisions between two C59N.⊂[10]CPP species with both radicals exposed will occur 108 times less than when the [10]CPP is not present (e.g., a 1 ms reaction would now take about one day), which is consistent with the extended radical stability.

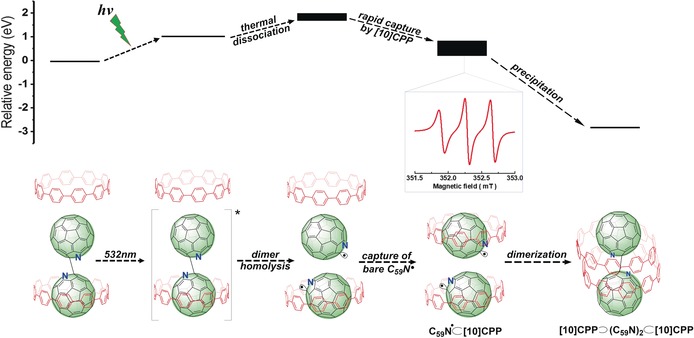

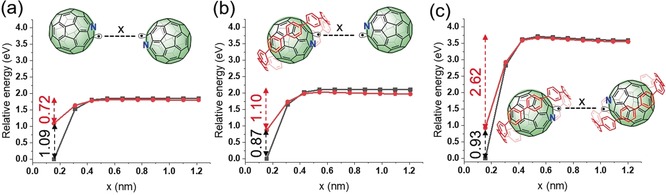

The formation and decay mechanism of the C59N.⊂ [10]CPP radical with calculated relative energies (Table S2) of the various species is summarized in Figure 3. As described, the major starting component in solution is the (C59N)2⊂ [10]CPP species together with the excess of free [10]CPP.31 Upon light irradiation, the (C59N)2 dimer is cleaved, yielding EPR‐active C59N.⊂[10]CPP, as well as a bare C59N., which is immediately captured by a nearby free [10]CPP. Slow recombination of the photogenerated C59N.⊂[10]CPP radical on the timescale of 100 min affords the corresponding neutral and EPR‐silent [10]CPP⊃(C59N)2⊂[10]CPP complex, as evidenced by 1H NMR analysis. DFT calculations confirmed the favourable energetics of this route (Figure 4). Without illumination, the calculated separation barriers for (C59N)2 into 2 C59N. are all >1.6 eV and thermally inaccessible at room temperature irrespective of the presence or not of [10]CPP. Introducing irradiation, by spin flipping an electron, decreases these barriers to 0.72 eV for isolated (C59N)2 and 1.10 eV for (C59N)2⊂[10]CPP, so that both processes can occur spontaneously at room temperature. The final system with two C59N.⊂[10]CPP species is only 0.19 eV less stable than the initial (C59N)2⊂[10]CPP+[10]CPP system. A [10]CPP⊃ (C59N)2⊂[10]CPP complex will remain stable at room temperature and will not be cleaved even in the triplet state (separation barrier >2.5 eV). We note that the presence of [10]CPP slightly increases the barrier to C−C bond homolysis (1.81 eV to 1.97 eV; see Figure 4 a, b). This is due to the stabilization of the initial (C59N)2⊂[10]CPP complex through C−H–π (fullerene) interactions between [10]CPP and the non‐encircled C59N species.

Figure 3.

Top: DFT‐calculated relative energies for the different species; finite width bars indicate energy ranges dependent on the relative orientation of C59N. and [10]CPP in the radical complex. Bottom: Illustration of the light‐induced generation of the C59N.⊂[10]CPP radical complex and the decay pathway. Inset: The EPR signal of long‐lived C59N.⊂[10]CPP.

Figure 4.

DFT relative energy barriers calculated using the nudged elastic band method to separate a) (C59N)2 in the absence of [10]CPP rings, b) (C59N)2⊂[10]CPP, and c) [10]CPP⊃(C59N)2⊂[10]CPP. Black and red lines/points indicate system spins of 0 μB and 2 μB, respectively, that is, after spin flipping of one electron.

Conclusion

In summary, we have shown that [10]CPP efficiently hosts and shields the otherwise highly reactive azafullerenyl C59N. radical, and that light‐induced quantitative formation of [10]CPP⊃(C59N)2⊂[10]CPP offers a facile route to access supramolecular complexes that cannot be generated by means of classical liquid‐phase processing. The slow dynamics of C59N.⊂[10]CPP in 1‐chloronaphthalene and the C59N. radical protection by the [10]CPP ring hinder the recombination process, allowing the observation of paramagnetic C59N. on unprecedentedly long timescales. The approach outlined in this work is thus an important step towards the generation and assembly of stable azafullerenyl radicals. The methodology can be extended to protect other fullerene‐centered radicals, given the wealth of CPPs with different ring diameters.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

C.P.E., J.R., H.A.W., and N.T. acknowledge funding from Region Pays de la Loire “Paris Scientifiques 2017”, Grant Number 09375 and the CCIPL, where some of these calculations were performed. C.P.E. and N.T. acknowledge the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska‐Curie grant agreement No. 642742. A.S. and N.T. acknowledge financial support from “National Infrastructure in Nanotechnology, Advanced Materials and Micro‐/ Nanoelectronics” (MIS 5002772), which is implemented under the “Reinforcement of the Research and Innovation Infrastructures”, funded by the Operational Program “Competitiveness, Entrepreneurship and Innovation” (NSRF 2014–2020), Ministry of Development and Investments and co‐financed by Greece and the European Union (European Regional Development Fund). D.A. acknowledges financial support from the Slovenian Research Agency (Core Research Funding No. P1‐0125 and Project No. N1‐0052). D.A. also acknowledges the assistance of Dr. Pavel Cevc in the experimental work. A.S. acknowledges the support by a STSM Grant from the COST Action CA15107 Multicomp, supported by the COST Association (European Cooperation in Science and Technology).

A. Stergiou, J. Rio, J. H. Griwatz, D. Arčon, H. A. Wegner, C. P. Ewels, N. Tagmatarchis, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 17745.

Contributor Information

Prof. Dr. Denis Arčon, Email: denis.arcon@ijs.si.

Prof. Dr. Hermann A. Wegner, Email: hermann.a.wegner@org.chemie.uni-giessen.de.

Dr. Christopher P. Ewels, Email: chris.ewels@cnrs-imn.fr.

Dr. Nikos Tagmatarchis, Email: tagmatar@eie.gr.

References

- 1. Umeyama T., Imahori H., Nanoscale Horiz. 2018, 3, 352–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kirner S., Sekita M., Guldi D. M., Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 1482–1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Casu M. B., Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 753–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ardavan A., Blundell S. J., J. Mater. Chem. 2009, 19, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Benjamin S. C., Ardavan A., Briggs G. A. D., Britz D. A., Gunlycke D., Jefferson J., Jones M. A. G., Leigh D. F., Lovett B. W., Khlobystov A. N., Lyon S. A., Morton J. J. L., Porfyrakis K., Sambrook M. R., Tyryshkin A. M., J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2006, 18, S867–S883. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Niklas J., Poluektov O. G., Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7, 1602226. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Strauss V., Roth A., Sekita M., Guldi D. M., Chem 2016, 1, 531–556. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Segura J. L., Martín N., Guldi D. M., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2005, 34, 31–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wu Q., Yang L., Wang X., Hu Z., Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 435–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nonell S., Arbogast J. W., Foote C. S., J. Phys. Chem. 1992, 96, 4169–4170. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wasielewski M. R., O'Neil M. P., Lykke K. R., Pellin M. J., Gruen D. M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 2774–2776. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Konarev D. V., Khasanov S. S., Otsuka A., Saito G., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 8520–8521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wabra I., Holzwarth J., Hauke F., Hirsch A., Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 5186–5201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ganin A. Y., Takabayashi Y., Jeglič P., Arčon D., Potočnik A., Baker P. J., Ohishi Y., McDonald M. T., Tzirakis M. D., McLennan A., Darling G. R., Takata M., Rosseinsky M. J., Prassides K., Nature 2010, 466, 221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Takabayashi Y., Ganin A. Y., Jeglič P., Arčon D., Takano T., Iwasa Y., Ohishi Y., Takata M., Takeshita N., Prassides K., Rosseinsky M. J., Science 2009, 323, 1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rotas G., Tagmatarchis N., Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 1206–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Keshavarz-K M., González R., Hicks R. G., Srdanov G., Srdanov V. I., Collins T. G., Hummelen J. C., Bellavia-Lund C., Pavlovich J., Wudl F., Holczer K., Nature 1996, 383, 147–150. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hummelen J. C., Knight B., Pavlovich J., González R., Wudl F., Science 1995, 269, 1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hicks R. G., Org. Biomol. Chem. 2007, 5, 1321–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Please note that even though bulky substituents have been incorporated onto C59N, radical chemistry was not investigated on those azafullerene derivatives; see: Neubauer R., Heinemann F. W., Hampel F., Rubin Y., Hirsch A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 11722–11726; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2012, 124, 11892–11896. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Simon F., Kuzmany H., Náfrádi B., Fehér T., Forró L., Fülöp F., Jánossy A., Korecz L., Rockenbauer A., Hauke F., Hirsch A., Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 97, 136801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lewis S. E., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 2221–2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wu D., Cheng W., Ban X., Xia J., Asian J. Org. Chem. 2018, 7, 2161–2181. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Xu Y., von Delius M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 10.1002/anie.201906069; [DOI] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2019, 10.1002/ange.201906069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Iwamoto T., Watanabe Y., Sadahiro T., Haino T., Yamago S., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 8342–8344; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2011, 123, 8492–8494. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Xia J., Bacon J. W., Jasti R., Chem. Sci. 2012, 3, 3018–3021. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhao C., Meng H., Nie M., Wang X., Cai Z., Chen T., Wang D., Wang C., Wang T., J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 12514–12520. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Toyota S., Tsurumaki E., Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 6878–6890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Xu Y., Wang B., Kaur R., Minameyer M. B., Bothe M., Drewello T., Guldi D. M., von Delius M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 11549–11553; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 11723–11727. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Xu Y., Kaur R., Wang B., Minameyer M. B., Gsänger S., Meyer B., Drewello T., Guldi D. M., von Delius M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 13413–13420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rio J., Beeck S., Rotas G., Ahles S., Jacquemin D., Tagmatarchis N., Ewels C., Wegner H. A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 6930–6934; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 7046–7050. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hauke F., Hirsch A., Tetrahedron 2001, 57, 3697–3708. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hasharoni K., Bellavia-Lund C., Keshavarz-K M., Srdanov G., Wudl F., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 11128–11129. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gruss A., Dinse K.-P., Hirsch A., Nuber B., Reuther U., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 8728–8729. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Simon F., Arčon D., Tagmatarchis N., Garaj S., Forro L., Prassides K., J. Phys. Chem. A 1999, 103, 6969–6971. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fülöp F., Rockenbauer A., Simon F., Pekker S., Korecz L., Garaj S., Jánossy A., Chem. Phys. Lett. 2001, 334, 233–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pagona G., Rotas G., Khlobystov A. N., Chamberlain T. W., Porfyrakis K., Tagmatarchis N., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 6062–6063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Arčon D., Pregelj M., Cevc P., Rotas G., Pagona G., Tagmatarchis N., Ewels C., Chem. Commun. 2007, 3386–3388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rockenbauer A., Csányi G., Fülöp F., Garaj S., Korecz L., Lukács R., Simon F., Forró L., Pekker S., Jánossy A., Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 94, 066603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kuzmany H., Fink J., Mehring M., Roth S., Molecular Nanostructures, World Scientific, Singapore, 1998, pp. 1–570. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Blinc R., Seliger J., Dolinšek J., Arčon D., Phys. Rev. B 1994, 49, 4993–5002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary