ABSTRACT

Epithelial cells are immune sensors and mediators that constitute the first line of defense against infections. Using the epididymis, a model for studying tubular organs, we uncovered a novel and unexpected role for professional proton-secreting ‘clear cells’ in sperm maturation and immune defense. The epididymal epithelium participates in the maturation of spermatozoa via the establishment of an acidic milieu and transfer of proteins to sperm cells, a poorly characterized process. We show that proton-secreting clear cells express mRNA transcripts and proteins that are acquired by maturing sperm, and that they establish close interactions with luminal spermatozoa via newly described ‘nanotubes’. Mechanistic studies show that injection of bacterial antigens in vivo induces chemokine expression in clear cells, followed by macrophage recruitment into the organ. Injection of an inflammatory intermediate mediator (IFN-γ) increased Cxcl10 expression in clear cells, revealing their participation as sensors and mediators of inflammation. The functional diversity adopted by clear cells might represent a generalized phenomenon by which similar epithelial cells decode signals, communicate with neighbors and mediate mucosal immunity, depending on their precise location within an organ.

This article has an associated First Person interview with the first author of the paper.

KEY WORDS: RNA sequencing, V-ATPase, Sperm maturation, Immune regulation, Male reproductive tract, Post-testicular regulation, Male fertility

Summary: Proton-secreting cells lining the epididymal tubule can switch their function to become previously unrecognized regulators of immune responses, while establishing close interactions with spermatozoa.

INTRODUCTION

Epithelial cells create a barrier to the environment and are the first sites of attack by pathogens. In addition, some epithelia also provide a balance between tolerance and immune activation. This relates in particular – but not exclusively – to the epididymal epithelium within the male reproductive tract. In the epididymis, prevention of autoimmune responses against auto-antigenic spermatozoa (which appear during puberty after the immune definition of ‘self’ has been established), while providing protection against ascending and blood pathogens, is a key determinant of male fertility (Da Silva and Smith, 2015). In addition, the epididymis is an immune privileged organ that rarely develops carcinomas (Okasaki and Pryor, 2002). The ability of epididymal epithelial cells to provide immunological tolerance while ensuring rapid recognition of pathogens and defense against cancer cells still remains largely uncharacterized. Another crucial function of the epididymal epithelium is to create an optimal luminal environment for the maturation of spermatozoa. This includes the establishment of an acidic milieu (Breton and Brown, 2013), as well as the transfer of proteins from epithelial cells to sperm cells (Sullivan, 2015), a process that is still poorly characterized. The current report describes an in-depth characterization of specialized epithelial cells that, on the one hand, are involved in ‘traditional’ transepithelial functions – in this case acid secretion – but that can switch their function to become previously unrecognized regulators of immune responses, while establishing close interactions with spermatozoa.

Luminal acidification is essential for the proper function of several epithelia and tissues including the kidney, bone, inner ear and olfactory mucosa, in addition to the epididymis (Breton and Brown, 2013). An acidic luminal environment in the epididymis is achieved via the activity of professional proton-secreting ‘clear cells’ (CCs), and is required for the maturation and storage of spermatozoa. The present study examines how acidifying CCs in the epididymis modulate their extracellular environment, and how they communicate with neighboring immune cells and spermatozoa. Transcriptomic RNA sequencing cluster analysis revealed that CCs can be assigned functions related to immune activation, immune tolerance, microbial defense, anti-oxidant protection, proteolysis inhibition and protein transfer to maturing spermatozoa. Importantly, we also show that there is a remarkable location-specific plasticity of the apical plasma membrane that allows CCs to interact with spermatozoa in the epididymal lumen via the formation of long structures similar to nanotubes that reach deep into the lumen. Finally, we report a novel pro-inflammatory role for CCs following exposure to bacterial antigens, highlighting their multiple functions in this epithelium.

Our findings represent a clear demonstration that a given cell type, thought to have a uniform role, can in fact have tremendous functional diversity. Within the same organ (the epididymis), CCs play different roles depending on their microenvironment, the neighboring cells and the different stimuli they could receive. In this way, populations of cells can now be segregated based on very distinct patterns of gene expression. Such a marked heterogeneity and region-specific diversity in seemingly similar cells may be applicable to epithelial cells in other tissues and organs.

RESULTS

RNA sequencing in CCs isolated from distinct epididymal regions

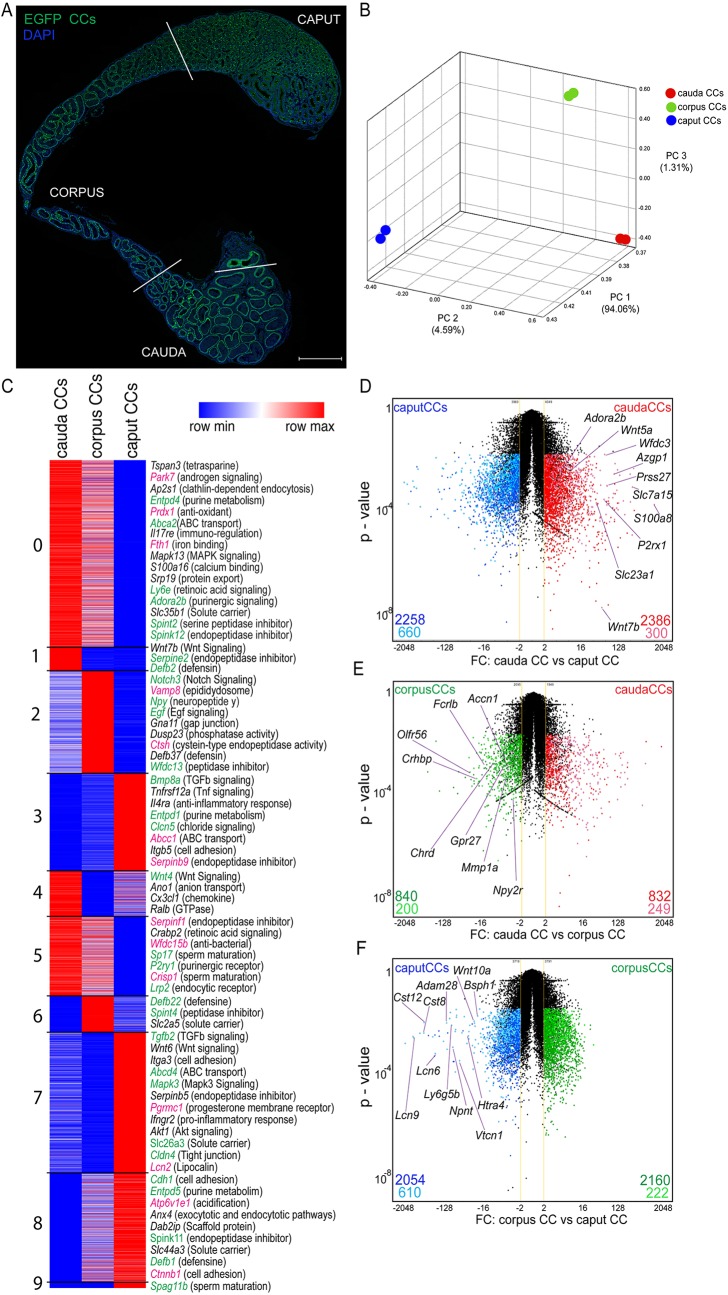

The epididymis is a long and single tubule whose epithelium forms the blood–epididymis barrier (Guyonnet et al., 2011; Johnston et al., 2005, 2007; Mital et al., 2011; Robaire and Orgebin-Crist, 2006; Zhou et al., 2018). It is organized into three major segments: the proximal region [the initial segments (IS) and caput], the corpus and the cauda. We have previously shown that elaborate communication networks between the different epithelial cell types [narrow cells, CCs, principal cells (PCs) and basal cells] are important to establish an optimal acidic luminal environment for the maturation and storage of spermatozoa (Breton and Brown, 2013; Roy et al., 2016; Shum et al., 2011b). In order to gain insight into how CCs communicate with neighboring cells, we investigated their gene expression profile based on their location in the epididymis through RNA sequencing (RNA-seq). EGFP+ CCs were isolated by double cell sorting from the caput (including the IS), corpus and cauda epididymal regions of B1-EGFP transgenic mice that specifically express EGFP in CCs (Fig. 1A). The complete transcriptome dataset is shown in Table S1. Principal component analysis (PCA) 3D mapping of our RNA-seq data demonstrated that CCs from the three regions are clearly separated from each other based on global transcriptome expression profiles (Fig. 1B). Cluster analysis of transcript expression patterns identified nine clusters (Fig. 1C). While several genes are common to all CCs, subsets of genes are differentially expressed in CCs from each epididymal region, and some are exclusive to CCs isolated from each region (Table S2). These include cell surface receptors, transcription factors, transporters and secreted proteins. Some of the genes detected here in CCs have been previously reported in the epididymis (Fig. 1C, green labels), but their cell-specific location was unknown. In addition, we confirm expression of mRNAs encoding proteins that we previously reported to be present in CCs in a proteomics analysis (Da Silva et al., 2010) (Fig. 1C, pink labels), and we now reveal their epididymal segment differential expression. Volcano plots [fold change (FC) versus P value] comparing the gene expression profiles of cauda CCs (red), corpus CCs (green) and caput CCs (blue) show fewer genes that are differentially expressed between corpus and cauda CCs, compared to genes of the caput versus cauda, and caput versus corpus. Groups of genes exclusively expressed in CCs in each epididymal region are shown in light colors, and selected region-specific plasma membrane proteins are named in Fig. 1D–F.

Fig. 1.

Heterogeneous gene expression of CCs from different epididymal segments. (A) Distribution of EGFP+ CCs (green) in the adult mouse epididymis (caput, corpus and cauda). Blue indicates the DNA marker DAPI. Scale bar: 1 mm. (B) Three-dimensional PCA plot of the transcriptomes (population-level RNA-seq) from cauda, corpus and caput CCs, showing differential gene expression patterns in cells from the three regions. Each sample of RNA was obtained from double cell sorting live EGFP+ CCs from a pool of 12 epididymides. (C) Heat-map showing the nine clusters identified in the CC transcriptome based on respective location-specific transcript expression levels. Heat-maps represent row-normalized gene expression of the indicated genes using a color gradient scale ranging from higher (red) to lower (blue) relative levels. Some cell-to-cell communication signaling transcripts are shown; some of the identified genes were previously reported to be present in the epididymis (green labels), others were previously reported by our laboratory to be expressed in CCs in a proteomics study (pink labels). (D–F) Volcano plot of EGFP+ CCs from caput (blue) versus cauda (red) (D), from corpus CC (green) versus cauda (red) (E), and from caput (blue) versus corpus CC (green) (F). Upregulated segment-specific genes (dark colors) and region-specific transcripts that might be plasma membrane markers for CCs (light colors) are highlighted. FC, fold change. The yellow lines show ±2FC. The black dots represent transcripts that are not significantly differentially expressed. Data were analyzed using the Student's t-test, two-tailed; a value of P<0.05 was considered significant.

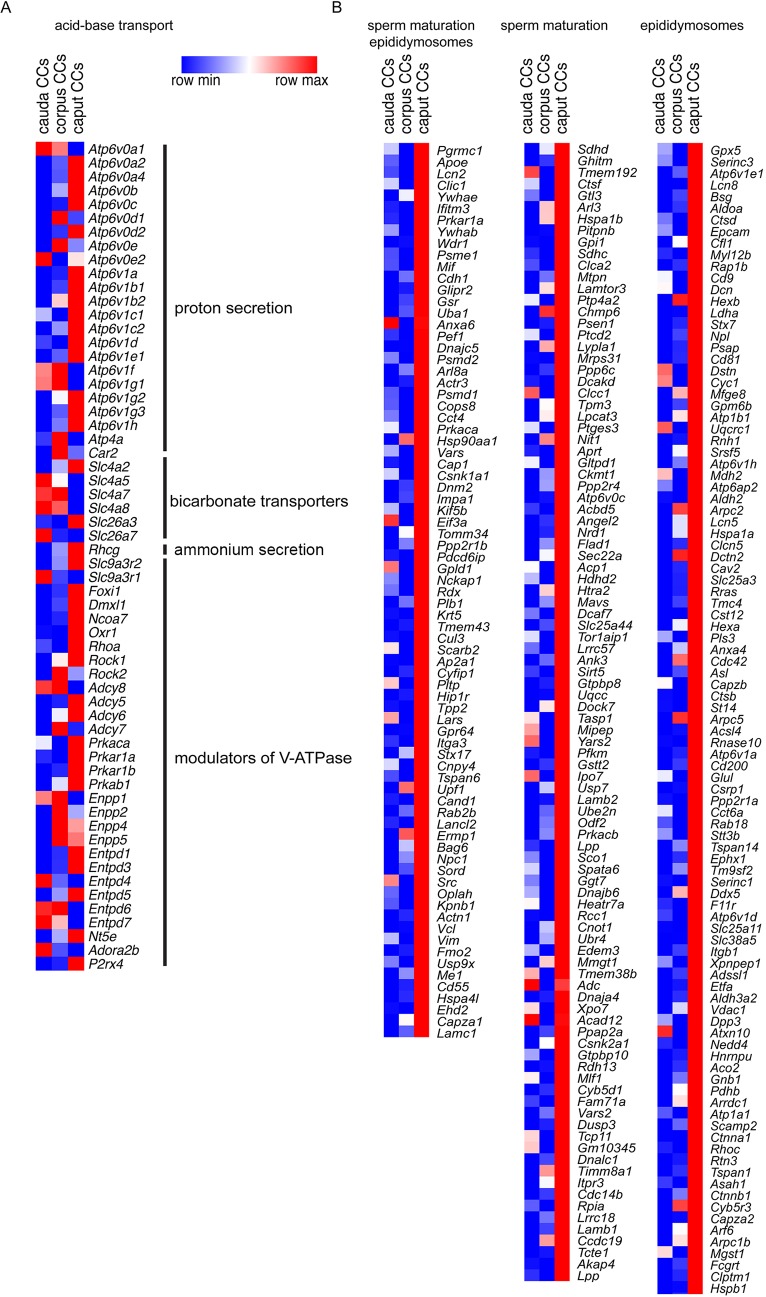

In agreement with their known acidifying role, genes belonging to acid/base transport were identified in CCs from the three regions, including several subunit isoforms of the proton pump V-ATPase (e.g. Atp6v0b, Atp6v0e, Atp6v1g1 and Atp6v1b1), bicarbonate transporters (Slc4a and Slc26a carriers) and Rhcg, an ammonium transporter (Fig. 2A; Table S3). Interestingly, CCs also express several genes that are involved in the regulation of V-ATPase-dependent H+ secretion, such as adenylate cyclase, protein kinase A, ectonucleotidases (Nt5e, Entpd and Enpp) and purinergic receptors (Adora2b and P2rx4). We then examined the potential implication of CCs in complementary functions that could take place in addition to their traditional participation in the vectorial transport of protons.

Fig. 2.

Location-dependent functional specialization of CCs. (A) Heat-map of identified transcripts that are related to acid-base balance (proton secretion via the V-ATPase, bicarbonate transporters, ammonium secretion, as well as modulators of V-ATPase-dependent proton secretion) in CCs from the three segments of the epididymis examined. The complete list is in Table S3. (B) Heat-map of identified transcripts with high expression in caput CCs that encode proteins that have been previously shown to be acquired by sperm (sperm maturation) during epididymal transit and were also detected in epididymosomes (left), proteins acquired by sperm (middle), or proteins that were described in epididymosomes (right panel shows the 100 highest expressed genes in caput CCs). The complete list is provided in Table S4. Heat-maps represent row-normalized gene expression of the indicated genes using a color gradient scale ranging from higher (red) to lower (blue) relative levels.

Role of CCs in intercellular communication

Interaction with sperm

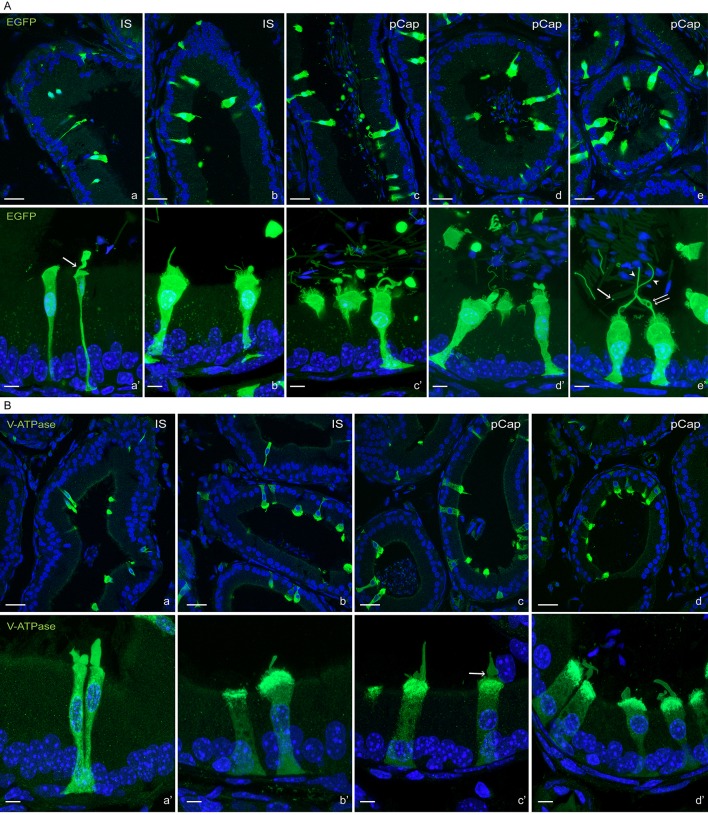

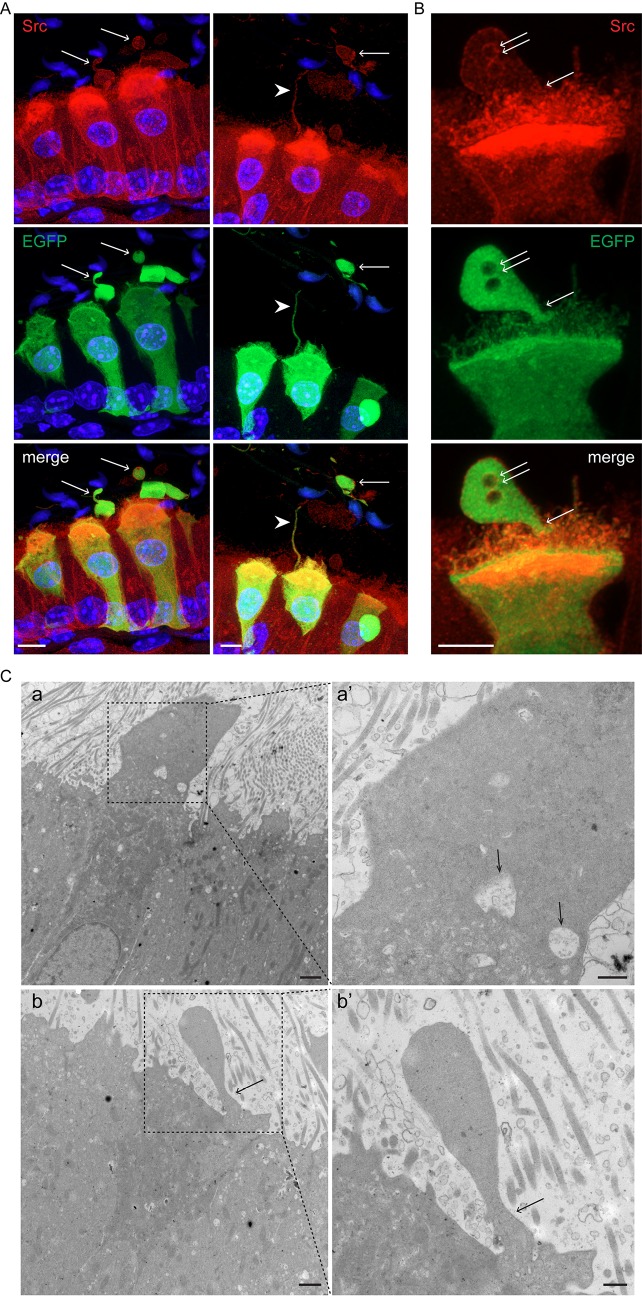

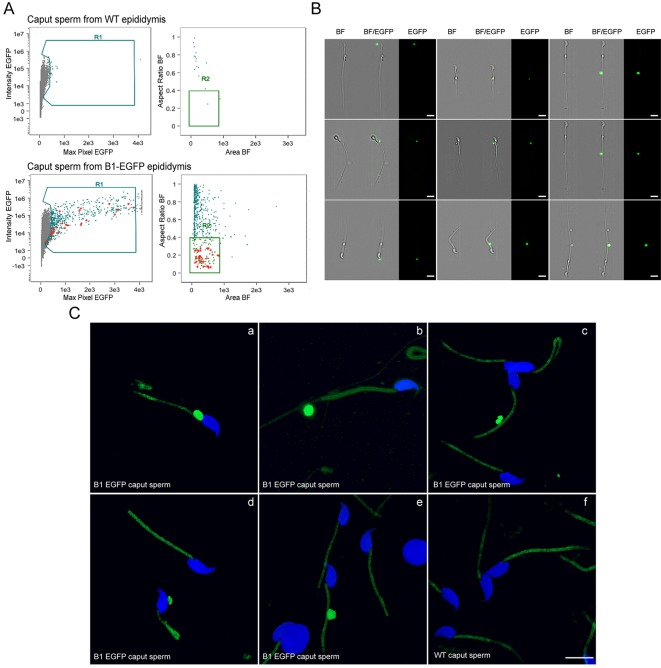

An important function of the epididymal epithelium is to transfer new proteins to spermatozoa, a process that is mediated via extracellular vesicles called epididymosomes (Guyonnet et al., 2011; Johnston et al., 2005, 2007; Nixon et al., 2019; Sullivan, 2015; Thimon et al., 2007; Yanagimachi et al., 1985; Zhou et al., 2018). Interestingly, CCs express transcripts that encode proteins that have been previously shown to be acquired by sperm during epididymal transit (Aitken et al., 2007; Skerget et al., 2015) and were also detected in epididymosomes (Frenette et al., 2010; Nixon et al., 2019; Sullivan, 2015) (Fig. 2B, left column). In addition, CCs express transcripts that encode proteins known to be acquired by sperm during epididymal maturation, although it is unclear whether they are transferred through epididymosomes (Fig. 2B, middle column). CCs also express transcripts of proteins that were described in epididymosomes, although their transfer to sperm remains uncertain (Fig. 2B, right column; Table S4). Confocal microscopy analysis of the proximal epididymis of B1-EGFP mice revealed the presence of several types of apical membrane protrusions in narrow cells in the IS and CCs in the proximal caput (Fig. 3A). While some of these membrane extrusions may represent apocrine secretion, others were long apical extensions, similar to previously described nanotubes, which reached out deep into the lumen to directly interact with spermatozoa (Fig. 3A; Movie 1). We also found large EGFP+ vesicles and filamentous structures in the luminal compartment, indicating their formation as a consequence of fragmentation from the CC plasma membrane. Immunofluorescence (IF) analysis showed that these protrusions are positive for the V-ATPase (Fig. 3B; Movie 2) and also contain Src, a protein that is transferred to sperm during their epididymal maturation (Krapf et al., 2012) (Fig. 4A,B; Movie 3). Electron microscopic images showed that narrow cells and CCs, identified by their high mitochondria content and apically located nuclei, present large apical blebs indicating their apocrine activity (Fig. 4C). While some of the protrusions contain vesicles (arrows in Fig. 4Ca′), others have a smooth appearance lacking intracellular organelles (Fig. 4Cb–b′). Note that some apical protrusions have a connecting stalk attached to the cell (arrow in Figs 3Aa′,Bc′ and 4B,Cb′). Moreover, we observed that some apical protrusions appear to have ‘holes’ (double arrow in Figs 3Ae′ and 4B). In addition, imaging flow cytometry (AMNIS) showed that EGFP+ vesicles are attached to several sperm, even after their isolation from the caput region of B1-EGFP transgenic mice (Fig. 5A,B). WT mice were used as controls to determine the threshold for green fluorescence positivity (Fig. 5A, top panels). The R1 gate shows EGFP+ events (i.e. EGFP+ vesicles) and the R2 gate [the aspect ratio and the area of the bright-field (BF)] includes events compatible with sperm morphology (i.e. EGFP+ vesicles close or attached to spermatozoa). By using this powerful technology, 520±46 (mean±s.e.m.) EGFP+ events were detected in the caput sperm samples from B1-EGFP mice (Fig. 5A, left bottom panel, R1 gate) and from those events, 14.1±1.2% (mean±s.e.m.) were EGFP+ events (vesicles) in close proximity to sperm (Fig. 5A, right bottom panel, R2 gate). Individual review of each image in this population revealed that 26.0±2.2% of EGFP+ vesicles were attached to sperm cells (Fig. 5A, lower panels, red dots). Fig. 5B shows representative images of EGFP+ vesicles attached to sperm in the BF and EGFP channels. 3D confocal microscopy images also revealed the presence of sperm cells in contact with EGFP-containing vesicles from the caput region of B1-EGFP transgenic mice (Fig. 5Ca–e; Movies 4–8). We could also detect sperm–vesicle complexes after sperm isolation in vitro, indicating that the interaction between the vesicle and sperm membrane was strong enough to remain intact during the isolation procedure. The mid-piece of WT mouse sperm has a high auto-fluorescence level in the green wavelength, probably due to the high number of mitochondria in this region (Fig. 5Cf). IF labeling of epididymal sections from B1-EGFP mice also showed sperm–vesicle interaction events (Fig. S1, arrows). 3D reconstruction revealed several EGFP+ vesicles that were embedded within the sperm head (Movies 9 and 10). Interestingly, large luminal EGFP+ vesicles appeared to be in the process of fragmentation into smaller vesicles (Fig. S1, arrowheads). In all experimental conditions, vesicles that were attached to the sperm head, mid-piece and principal piece were observed, indicating their affinity for all regions of the sperm membrane. Next, we examined the localization of the exosome marker CD63 in the epididymis from B1-EGFP mice (Fig. S2A). CD63 was detected in all epithelial cells in the caput epididymis, and was enriched in the apical blebs (star) and nanotubes (arrowhead) of CCs. There are CD63-containing structures in the lumen that are also positive for EGFP, indicating that they were shed from CCs (arrows). EGFP and CD63 double-positive vesicles attached to sperm were also observed after their isolation from the caput of B1-EGFP mice (Fig. S2B). A recent study reported that the CC-specific V-ATPase subunits ATP6V0A4 (a4) and ATP6V1G1 (G1) are present in mouse epididymosomes (Nixon et al., 2019). We show here that the EFGP+ apical CC protrusions contain a4, as do EGFP+ luminal vesicles (Fig. S3A, arrows) and EGFP+ vesicles that are in intimate contact with sperm isolated from the caput region (Fig. S3B). Taken together, these results indicate that CCs participate in the transfer of proteins to spermatozoa, either via direct contact of their nanotubes with the sperm cell or via the production of epididymosomes.

Fig. 3.

Confocal microscopy showing CC-spermatozoa communication. (A) Confocal microscopy images of EGFP+ narrow cells in IS (Aa–b′) and EGFP+ CCs in the proximal caput (pCap; Ac–d′) showing the presence of apical blebs and apical membrane protrusions. Lower panels show higher magnifications of a portion of the same images shown in the upper panels. EGFP+ large vesicles and filamentous structures are also present in the tubule lumen. The arrow in panel Aa′ shows narrowing of the bleb to produce a connecting stalk attached to the cell. Some CCs show long protrusions similar to ‘nanotubes’ that reach out into the lumen (Ae,e′, arrowheads). These long structures come into contact with spermatozoa. Note the presence of ‘holes’ in these apical protrusions (double arrow). Some EGFP+ elongated structures and fragments are present in the lumen, indicating they originate from CCs (e.g. in panels Ac′,Ad′ and Ae′). A small EGFP+ vesicle is shown in contact with the mid-piece of a sperm cell (arrow in Ae′). (B) Confocal microscopy images showing V-ATPase B1 subunit IF labeling in narrow cells from the IS (Ba–b′) and CCs from the pCap (Bc–d′). Lower panels show a higher magnification of a portion of the image shown in the upper panels. EGFP+ apical membrane blebs and protrusions are labeled for V-ATPase. The arrow in panel Bc′ shows the narrowing of the apical bleb to produce a connecting stalk attached to the cell. Nuclei are labeled with DAPI in blue. Scale bars: 20 µm (main images); 10 µm (magnifications).

Fig. 4.

Immunofluorescence labeling showing that CC apical blebs, EGFP+ extracellular vesicles and CC nanotubes contain Src, and electron microscopy showing apical blebs in CCs. (A) Confocal microscopy images showing the localization of Src in EGFP+ CCs, CC apical blebs and luminal EGFP+ vesicles (arrows) and a CC nanotube (arrowhead). Nuclei are labeled with DAPI in blue. Scale bar: 5 µm. (B) Confocal Airyscan microscopy images showing the co-localization of EGFP+ and Src in CCs and apical blebs. Arrow shows the narrowing of the bleb to produce a connecting stalk attached to the cell, and the double arrow shows “holes” in the apical protrusion. Scale bars: 2.5 µm. (C) EM images showing CCs (identified by their high mitochondria content and apically located nucleus) that have extensive apical membrane protrusions. While some protrusions contain vesicles (arrows in panel a′), others have a smooth appearance lacking intracellular organelles (panels b,b′). Arrow in panels b and b’ indicates a connecting stalk still attached to the CC. Scale bars: 1 µm (main images); 500 nm (magnifications).

Fig. 5.

Caput spermatozoa attached to EGFP-containing vesicles in B1-EGFP mice. (A) Imaging flow cytometry (AMNIS) showing that EGFP+ vesicles are attached to several sperm isolated from the caput region of B1-EGFP transgenic mice. WT mice were used as controls to determine the threshold for green fluorescence positivity. Representative dot plots of caput sperm from WT (top panels) and B1-EGFP (bottom panels). R1 gate (mean intensity and maximum pixel intensity of EGFP) shows all EGFP+ events. R2 gate (the aspect ratio and the area of the BF) includes events compatible with sperm morphology. Red dots represent EGFP+ vesicles that were attached to sperm cells, upon visualization of individual images. (B) Representative images of EGFP+ vesicles attached to sperm showing the BF and the EGFP channel. Scale bars: 10 μm. (C) 3D confocal microscopy images of isolated sperm cells with EGFP-containing vesicles from the caput region of B1-EGFP transgenic mice (panels a–e). Panel f shows sperm cells from the caput region of WT mice. The middle piece of the mouse sperm has a high auto-fluorescence level in the green wavelength due to the high number of mitochondria in this region. Scale bar: 10 μm.

Interaction with immune cells

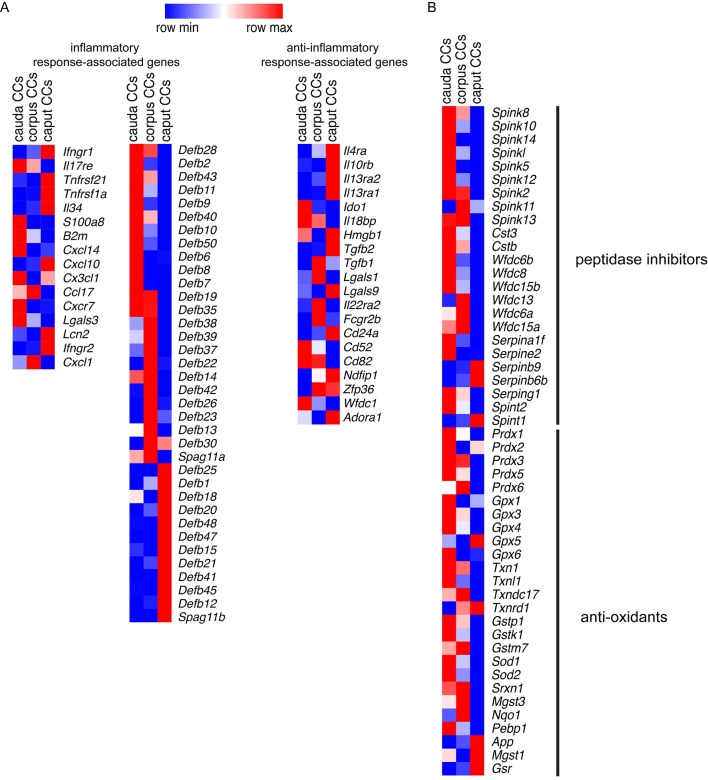

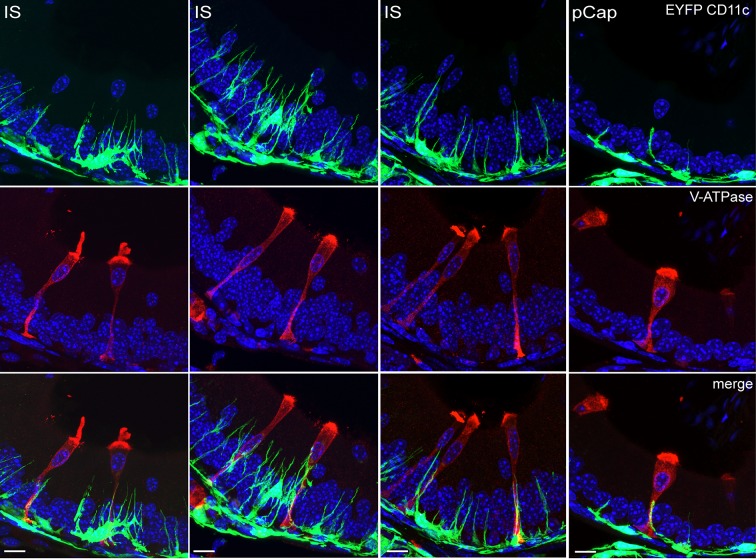

Our RNA-seq data showed that CCs also express multiple genes involved in immune regulation. As such, we detected inflammatory response-associated genes (Fig. 6A, left column; Table S5) and several β-defensins (Defbs) (Fig. 6A, middle column; Table S5). However, CCs also express anti-inflammatory genes (Fig. 6A, right column; Table S5). In addition, we identified several peptidase inhibitors and anti-oxidant transcripts that may be involved in the protection of the epididymal epithelium and spermatozoa (Fig. 6B; Table S6). IF labeling of epididymal sections from CD11c-EYFP transgenic mice that express EYFP exclusively in mononuclear phagocytes (MPs) revealed intraepithelial projections of CD11c EYFP+ MPs that are in close proximity to V-ATPase-positive narrow cells (the IS) and CCs (caput) (Fig. 7; Movie 11). Moreover, IF confirmed that Cx3cl1 is highly expressed in cauda CCs (Fig. S4); this chemokine binds CX3CR1, a MP receptor expressed by immune cells residing in the epididymis (Da Silva et al., 2011). Taken together, these data indicate that CCs in the epididymis have characteristics of immune regulatory cells, including the potential to mount an innate immune defense against pathogens while preserving sperm from the host immune system.

Fig. 6.

Location-dependent expression of immune regulators and protective enzymes in CCs. (A) Heat-map of the most representative inflammatory response-associated (left) and anti-inflammatory response-associated genes (right) in the CC transcriptome from the three regions examined. Middle, several β-defensin transcripts were also detected. The RPKM values are listed in Table S5. (B) Heat-map of 50 identified transcripts related to peptidase inhibitors and anti-oxidants in CCs from the three segments of the epididymis examined. The complete list is provided in Table S6. Heatmaps represent row-normalized gene expression of the indicated genes using a color gradient scale ranging from higher (red) to lower (blue) relative levels.

Fig. 7.

Mononuclear phagocyte–CC interactions. Confocal microscopy images showing multiple projections of CD11c EYFP-positive mononuclear phagocytes (green), in very close proximity to CCs (V-ATPase-positive cells, red) in the IS and in the proximal caput (pCap) epididymidis. Nuclei are labeled with DAPI in blue. Scale bars: 10 µm.

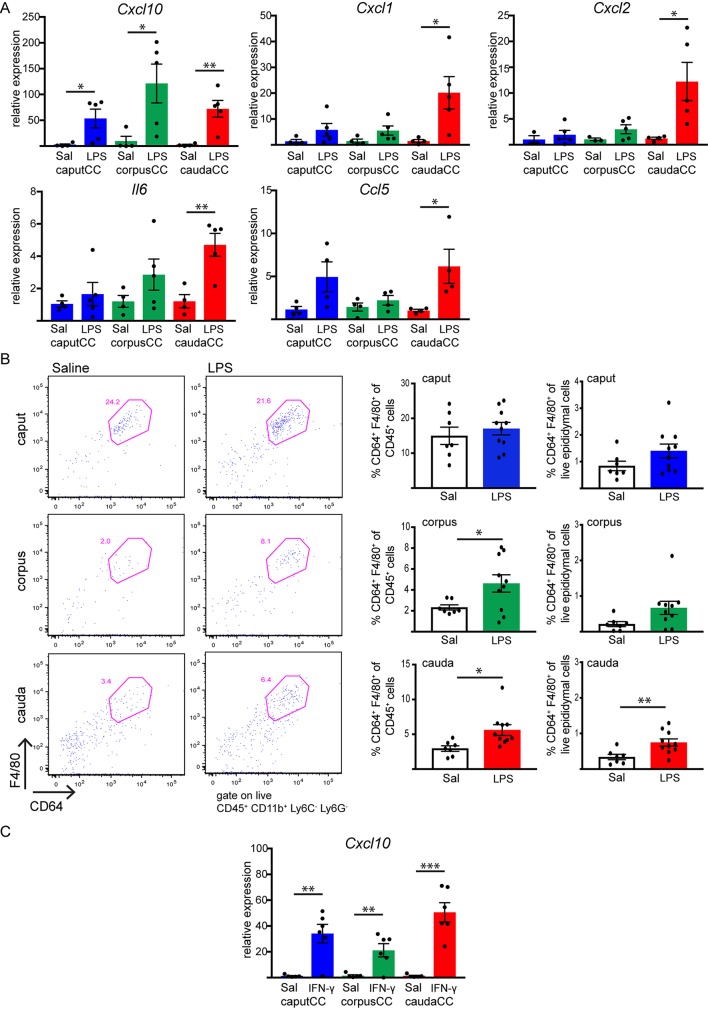

We next performed mechanistic studies to determine a potential functional link between CCs and epididymal MPs. Recent studies have shown that injection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a major structural component of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, into the vas deferens and distal epididymis (intravasal-epididymal injection) increases the level of pro-inflammatory factors in the epididymal cauda (Silva et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2019). Since our transcriptome data indicate that CCs might serve as immune regulators against pathogens, we examined the CC responsiveness to LPS. To that end, B1-EGFP mice were subjected to intravasal-epididymal injection with ultrapurified LPS from E. coli. Control mice were injected with saline (Sal). After 6 h, EGFP+ CCs were isolated by cell sorting from the caput, corpus and cauda epididymal regions, and we analyzed the acute inflammatory response of CCs by means of quantitative (q)PCR. In cauda CCs, LPS increased the mRNA levels of pro-inflammatory chemokines, such as Cxcl10, Cxcl1, Cxcl2, Il6 and Ccl5 compared to the saline-injected group (Fig. 8A). In corpus CCs and caput CCs, LPS treatment upregulated only Cxcl10 expression. No changes were detected for other pro-inflammatory chemokines tested (Tnf, Cx3cl1, Ccl2 and Il1b; Fig. S5A). We found that most of these chemokine genes (Cxcl2, Ccl2, Ccl5, Il6 and Tnf) were not detected in CCs under normal conditions, where no sham surgery was performed. However, we could detect their transcripts after intravasal-epididymal saline injection, indicating that the procedure per se upregulates the expression of these genes. Flow cytometry analysis revealed infiltration of CD45+CD11b+Ly6C−Ly6G−CD64+F4/80+ ‘macrophages’ (Ly6C and LY6G are surface markers for monocytes and neutrophils, respectively, and are not expressed by macrophages) into the corpus and cauda regions after 24 h of intravasal-epididymal LPS injection, considering only the CD45+ immune cell population (Fig. 8B, left dots plots and right bar graphs). However, the percentage of ‘macrophages’ with respect to the total number of live epididymal cells analyzed was increased only in the cauda after LPS injection (Fig. 8B, bar graphs). No LPS-induced macrophage infiltration was observed in the caput. When we compared macrophage population abundance between control (not injected) with saline-injected (Sal) epididymis, we detected a higher percentage of macrophages (with respect to CD45+ immune cells) in control epididymis compared to the saline group (Fig. S6). This result indicates that the intravasal-epididymal injection per se produces changes in the immune cell populations, consistent with the qPCR data above on chemokine gene expression. The decreased macrophage frequency in the saline condition compared to control epididymis is a consequence of a significant neutrophil and monocyte infiltration that occurs upon intravasal-epididymal injection. However, the neutrophil and monocyte percentage did not differ between saline- and LPS-treated epididymis (pink square in Figs S7 and S8A,B). Moreover, we observed no difference in Ly6G−Ly6C− population between LPS-injected and saline-injected groups (blue squares in Fig. S8A and Fig. 8C).

Fig. 8.

Intravasal-epididymal LPS or IFN-γ injections upregulates the expression of pro-inflammatory molecules in cauda CCs, and LPS treatment induces macrophage recruitment into the epididymis. (A) Relative quantification of Cxcl10, Cxcl1, Cxcl2, Il6, Ccl5 transcripts by qPCR. Caput (blue), corpus (green) and cauda (red) EGFP+ CCs were isolated by FACS from B1-EGFP mice 6 h after intravasal-epididymal injections (bilateral) with saline (Sal) or with saline containing LPS (25 µg in 25 µl). Samples were normalized to their internal control (Gapdh) and expressed as relative values of their respective saline control groups. Results are expressed as mean±s.e.m. of experiments performed in duplicate with samples from four mice for the saline group or five mice for the LPS group. *P<0.05; **P<0.01 (two-tailed Student's t-test; for Cxcl10, P=0.042 for caput CC, P=0.038 for corpus CC, and P=0.0067 for cauda CC; for Cxcl1, P=0.034; for Cxcl2, P=0.034; for Il6, P=0.0054; for Ccl5, P=0.042). (B) Flow cytometry analysis of infiltration of live macrophages (CD45+ CD11b+ Ly6C− Ly6G− F4/80+ CD64+) within the CD45+ cell population in the caput, corpus (P=0.041) and cauda (P=0.017) epididymis of mice 24 h after injection with saline or LPS. A significant increase in macrophages with respect to the total number of epididymal live cells analyzed was seen only in cauda region (P=0.0092). Results are expressed as mean±s.e.m. of experiments performed with both epididymides from five mice for control and six for LPS-treated group. *P<0.05; **P<0.01 (two-tailed Student's t-test). (C) Caput (blue), corpus (green) and cauda (red) EGFP+ CCs were isolated by FACS from B1-EGFP mice 4 h after intravasal-epididymal injections (bilateral) with saline (Sal) or with saline containing IFN-γ (10,000 units in 20 µl). Relative quantification of Cxcl10 transcripts by qPCR. Samples were normalized to their internal control (Gapdh) and expressed as relative values of their respective saline control groups. Results are expressed as mean±s.e.m. of experiments performed in duplicate with samples from five mice for the saline group and six mice for the IFN-γ group. **P<0.01; ***P<0.001 (two-tailed Student's t-test; P=0.0026 for caput CC, P=0.0073 for corpus CC, and P=0.0002 for cauda CC).

LPS increases interferon γ (IFN-γ) production in the epididymis (Silva et al., 2018) and other systems (Negishi et al., 2011), and our RNA-seq analysis revealed that CCs express IFN-γ type 1 and type 2 receptors. Thus, we studied the direct effect of IFN-γ on CCs. We found that, in vivo, IFN-γ intravasal-epididymal injection dramatically increased Cxcl10 expression in CCs from the three regions (Fig. 8C), while no effect was observed on the expression levels of Cxcl1, Cxcl2, Il6, Ccl5, Tnf, Cx3cl1, Ccl2 and Il1b (Fig. S5B) indicating that CCs have the ability to modulate immune responses to protect the epididymis.

DISCUSSION

Despite its critical involvement in reproduction, the segment-specific molecular machinery that epididymal epithelial cells employ to establish an optimal luminal environment for sperm maturation, protection and storage remains poorly characterized. Our present study addresses this issue by elaborating the transcriptome signature of a specific cell type, the proton-secreting CC, whose activity is central to male fertility (Blomqvist et al., 2006; Vidarsson et al., 2009). We uncovered molecular signals involved in cell–cell communication, and show that CCs adopt distinct region-specific physiological roles. In addition to their known participation in the luminal acidification necessary for the proper storage of spermatozoa (Breton et al., 2016), our results now implicate CCs in other critical functions of the epididymis, including sperm maturation and protection.

Our RNA-seq results show a higher degree of diversity of CCs isolated from the caput compared to CCs from the corpus and cauda. This is in agreement with previous global transcriptomic characterization of human epididymis tissues showing that the caput is functionally divergent from the corpus and cauda (Browne et al., 2016; Thimon et al., 2007). However, in these previous studies, the different epithelial cell types were not separated, and the corpus and cauda had similar transcriptomes. In the current study, we identify clearly distinct transcriptomic signatures between CCs from the corpus and cauda regions, which might reflect a more accurate functional characterization of a given specific cell type. In addition, we confirm the expression of several genes known to be present in proton-secreting CCs, including subunits of the V-ATPase, bicarbonate and ammonium transporters, as well as enzymes and receptors involved in the regulation of V-ATPase-dependent H+ secretion (Blomqvist et al., 2006; Breton and Brown, 2013; Da Silva et al., 2010; Herak-Kramberger et al., 2001; Jensen et al., 1999; Lee et al., 2013; Pastor-Soler et al., 2008; Shum et al., 2011a). In particular, CCs express several components of the purinergic signaling pathways, which we recently showed are key regulators of luminal acidification (Battistone et al., 2019; Belleannée et al., 2010).

During their transit through the epididymal lumen, sperm acquire new proteins (Aitken et al., 2007; Belleannée et al., 2011; Frenette et al., 2010; Skerget et al., 2015) via transfer from epididymosomes (Frenette et al., 2010; Labas et al., 2015; Nixon et al., 2019; Paunescu et al., 2014; Sullivan, 2015; Yanagimachi et al., 1985). PCs are traditionally believed to produce epididymosomes, which then fuse with the sperm membrane (Hermo and Jacks, 2002; Rejraji et al., 2006; Sullivan, 2015). Surprisingly, CCs express several transcripts encoding proteins that have been described in epididymosomes and are also acquired by sperm during epididymal transit. These include Src, CRISP1, ADAM7, serpine 2 and several Wnt proteins, which play crucial roles in male fertility (Banks et al., 2010; Da Ros et al., 2015; Koch et al., 2015; Krapf et al., 2012). These findings indicate that, in addition to PCs, CCs are also likely to participate in the transfer of proteins to sperm via the formation of epididymosomes. Several organs of the male reproductive tract use the apocrine pathway to secrete proteins (Aumüller et al., 1999). Apocrine secretion is characterized by the formation of apical blebs, which then detach from the apical membrane (Gesase and Satoh, 2003). We now provide confocal and electron microscopy evidence for the presence of apical blebs in narrow cells and CCs. This observation is in agreement with previous studies showing apical membrane protrusions in narrow cells using electron microscopy (Hermo et al., 2000; Orgebin-Crist, 1969). In secretory glands, the release of secretory materials by apocrine secretion is carried out by fragmentation, pinching-off and pore formation on the plasma membrane that covers the apical protrusions (Gesase and Satoh, 2003). In our study, we show several images of these proposed mechanisms in narrow cells and CCs in the proximal epididymal region. Indeed, we observed connecting stalks at the base of some CC apical protrusions that were very similar to the stalks previously reported using scanning electron microscopy (see figure 4 in Gesase and Satoh, 2003). These stalks may become progressively thinner and cause pinching off at the base of the stalk and the release of the protrusions. In agreement with this notion, numerous large vesicles were detected in the luminal compartment, and their EGFP content confirmed that they originated from CCs. Moreover, we observed that some apical protrusions present ‘holes’, an evidence of the reported pore formation mechanism. Moreover, EGFP-containing luminal vesicles and blebs are positive for CD63, a marker of extracellular vesicles. Similar results were previously found when CD9 staining was performed in the epididymis (Whelly et al., 2016).

Interestingly, we observed a new type of intercellular connections in CCs, characterized by long membrane protrusions, similar to the tunneling nanotubes (TNTs) or transzonal tubes described in other cell types (Chinnery et al., 2008; Clarke, 2018; Dupont et al., 2018; Lou et al., 2012; Rustom et al., 2004). These elongated structures connect the cytoplasm of cells and allow the exchange of substances, vesicles and organelles between non-adjacent distant cells. To our knowledge, most studies have described TNTs in cultured cells, except one that reported them in dendritic cells in the inflamed mouse cornea (Chinnery et al., 2008). We now provide in vivo evidence that epithelial cells, in particular proton-secreting CCs, form TNT-like structures. We propose that these novel cellular structures might be used for the transfer of exogenous proteins to some spermatozoa in the proximal epididymis. Of note, the probability of detecting intact nanotubes on thin sections is quite low and the fact we could actually find several of these long structures indicates their potential physiological relevance.

In addition, 3D image reconstruction allowed us to visualize luminal spermatozoa in the caput region that were attached to EGFP-containing vesicles and to EGFP+ nanotubes. Sperm–EGFP+ vesicle complexes were also detected after isolation of sperm from the caput region by imaging flow cytometry and confocal microscopy, indicating that their interaction was strong enough to remain intact during the isolation procedure. Moreover, we found that CC apical blebs, EGFP+ extracellular vesicles and CC nanotubes all contain Src, a protein acquired by sperm during epididymal transit (Krapf et al., 2012), as well as the exosome marker CD63. The fact that we, and others (Nixon et al., 2019) have observed that the V-ATPase subunit a4, specifically expressed in epididymal CCs (Pietrement et al., 2006), was detected in extracellular vesicles, strongly indicates that CCs have the ability to produce epididymosomes.

Another key process of sperm maturation is related to the correct localization of sperm surface components, which depends on proteolytic processing. Protease inhibitors present in the epididymal lumen have been proposed to finely control proteolysis activity during sperm maturation (Sipilä et al., 2009). Our RNA-seq data showed high expression of several peptidase inhibitors in CCs. In addition, we identified numerous players involved in the anti-oxidant defense system, which are activated to scavenge free radicals and protect tissues from injury (Chabory et al., 2010; Zubkova and Robaire, 2004). These results suggest that CCs participate in segment-specific epididymal pro-protein processing and sperm storage, and that they maintain tissue integrity through defense against oxidative damage.

A finely tuned balance between sperm tolerance and immune defense is required to maintain the immune privileged function of the epididymis, while protecting sperm against pathogens. Interestingly, CCs express components of immune activation in the epididymis. Among these mediators, we found several β-defensins (Defbs), a major subfamily of host defense peptides that are abundant in the epididymis (Johnston et al., 2007; Ribeiro et al., 2016). Thus, the current study now positions CCs as an important source of several Defbs, indicating that they may play a constitutive role in monitoring epididymal health. In addition, we found that CCs express mediators involved in the inflammatory response, such as IL-17, IFN-γ and TNF receptors, and several chemokines including Cxcl10, Cxcl1 and Cx3cl1. Our CC transcriptome also revealed regional distribution of selected immune response components. In particular, the danger-associated molecular pattern molecule S100a8 is expressed only in cauda CCs, in agreement with its higher expression in human cauda epididymis (Browne et al., 2016). In caput CCs, we found higher expression of IL-34, which promotes the release of pro-inflammatory chemokines in other epithelia (Franzè et al., 2016). However, CCs also express some anti-inflammatory response-associated genes, such as IL-4 and IL-13 receptors, as well as genes involved in the maintenance of immune tolerance, such as Ido1, Hmgb1 and Il18bp. IDO1 plays a role in epididymis immune tolerance toward sperm and mediates a regulatory response to prevent inflammation of the epididymis (Jrad-Lamine et al., 2013). Interestingly, we found TGFβ1 and TFGβ2 in CCs throughout the epididymis, indicating their potential participation in cross-talk with dendritic cells, which were recently shown to maintain a non-inflammatory steady state in the epididymis through TGFβ receptor type 2 (Pierucci-Alves et al., 2018). The present study thus points toward the role of CCs as immune modulators, and their participation in the establishment and maintenance of the protective immune-privileged environment in which spermatozoa mature and are stored. In agreement with this notion, we observed that mononuclear phagocytes establish intimate interactions with CCs in the epididymis. Moreover, we detected a higher percentage of ‘macrophages’ compared to monocytes and neutrophils in the three epididymal regions from control mice, similar to results from a recent study (Voisin et al., 2018). Of note, we previously found that proton-secreting cells in the kidney, the intercalated cells, also play a role in immune regulation (Azroyan et al., 2015). This implies that the proposed function of CCs in the epididymis might reflect a more widespread but under-appreciated activity of this family of acidifying cells.

Breakdown of the homeostasis between the epididymal mucosa and sperm might be responsible for a significant number of male infertility cases (McLachlan, 2002). Epididymitis is an inflammatory condition that frequently produces scrotal pain and infertility (Michel et al., 2015). Pathogens can reach the epididymis via their retrograde ascent through the urethra. An animal model that mimics that situation is the retrograde injection of bacteria or LPS into the vas deferens lumen (Michel et al., 2015; Silva et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2019), a procedure that increases tissue concentration of cytokines and chemokines in the cauda epididymis (Silva et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2019). Here, we show that CCs rapidly respond to an LPS challenge by upregulating distinct sets of pro-inflammatory chemokines and cytokines, such as Cxcl10, Cxcl1, Cxcl2, Ccl5 and Il6. Those molecules play important roles in immune cell recruitment to the epididymis upon infection. In particular, we show that, after 24 h, LPS induced more macrophage recruitment into the corpus and cauda regions, compared to what was seen with saline injection. This result is consistent with a recent study showing the presence of macrophages and pan-leukocytes in the interstitial spaces of the cauda epididymides several weeks after LPS injection (Wang et al., 2019).

In addition, LPS induced IFN-γ production in the epididymis and other tissues (Negishi et al., 2011; Silva et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2017). While CCs do not express toll-like receptors (TLRs), immune cells are known to have TLRs and produce IFN-γ when activated by LPS (Schroder et al., 2004), indicating a possible cell–cell crosstalk between CCs and resident macrophages in the LPS-induced response. In agreement with this notion, we show that CCs express IFN-γ receptors, and dramatically increase their expression of Cxcl10 following in vivo injection of IFN-γ. This chemokine is implicated in the recruitment and differentiation of pro-inflammatory macrophages under different physio-pathological situations (Liu et al., 2011; Petrovic-Djergovic et al., 2015; Tomita et al., 2016). Thus, the present study supports the hypothesis that CCs respond to pathogens and initiate crosstalk with immune cells to protect the epididymis. This cell–cell communication might involve IFN-γ and CXCL10. Moreover, under physiological conditions, TLRs have also been found in the epididymal epithelium (possibly PCs) and on luminal spermatozoa, indicating a potential crosstalk between CCs and neighboring cells (Hedger, 2011; Palladino et al., 2007, 2008). A better understanding of the onset of the epididymal epithelial inflammatory reaction that occurs upon an injury could help prevent chronic lesions that lead to irreversible loss of fertility and chronic scrotal pain.

In summary, our study provides evidence for unexpected roles of professional acidifying cells in other functions of the epididymis, including the maturation and protection of sperm as they transit along the epididymal tubule. These complex functions of CCs lining the tubule lumen are in addition to their ‘traditional’ role in transepithelial proton transport. Our present study fills knowledge gaps related to male reproductive biology, and addresses crucial concepts of mucosal immunology and cell–cell interactions – all of which are critical but understudied facets of human male reproductive health, notably impacting sperm storage and maturation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Adult (12 weeks) C57BL/CBAF1 wild-type male mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Transgenic mice that express either EGFP under the control of the ATP6V1B1 gene promoter (Miller et al., 2005) or EYFP under the control of the CD11c promoter (Lindquist et al., 2004) were used; they are referred to throughout as B1-EGFP (12 weeks) and CD11c-EYFP (12 weeks) transgenic mice, respectively. The mice referred to as ‘CX3CR1-EGFP’ (Jung et al., 2000) in this study are exclusively Cx3cr1Egfp/+ [heterozygote mice in which one of the endogenous loci the Cx3cr1 gene was disrupted by the insertion of sequence encoding enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP), replacing the first 390 bp of the coding exon 2] mice. All procedures described were reviewed and approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Subcommittee on Research Animal Care and were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Isolation of EGFP+ CCs from B1-EGFP mice, RNA extraction and RNA-seq

Isolation of EGFP+ CCs from the epididymis of B1-EGFP mice was performed as previously described (Da Silva et al., 2010). FACS isolation was performed at the HSCI-CRM Flow Cytometry Core (Boston, MA). A second sorting was performed to obtain a higher enrichment of the EGFP+ cell population. The RNA of EGFP+ CCs, from the three anatomical regions (caput, corpus and cauda), was isolated using a PicoRNA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) (Ruan et al., 2014). Each sample was obtained from 12 epididymides. Genomic DNA contamination was removed by digestion with an RNase-free DNase set (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). RNA quality and quantity were assessed using a Bioanalyzer (Agilent RNA 6000 Pico Kit, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). RNA-seq libraries were prepared using the Clontech SMARTER Kit v4, followed by sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq2500 instrument. Transcriptome mapping was performed with STAR (Dobin et al., 2013) using the Ensembl annotation of mm9 reference genome. Read counts for individual genes were produced using HTSeq (Anders et al., 2015). Differential expression analysis was performed using the EdgeR package (Robinson et al., 2010) after normalizing read counts and including only those genes with a counts per million (CPM) value of >1 for one or more samples. Differentially expressed genes were defined based on the criteria of >2-fold change in expression value and P<0.05. Unsupervised transcript clustering was performed using Express Cluster from the Gene-Pattern package (http://cbdm.hms.harvard.edu/LabMembersPges/SD.html) based on a k-means algorithm. Multiplot studio software was used to obtain differential gene-expression and the volcano plots, and the web-based software Morpheus was employed to plot heatmaps. RNA-seq dataset from CCs have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession number GSE130619.

Immunofluorescence labeling

IF of epididymis sections was performed as previously described (Battistone et al., 2019). For IF of isolated sperm, minced (three cuts) caput epididymides from B1-EGFP transgenic mice and WT mice were placed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 15 min at 37°C. Caput tissues were discarded, and the sperm suspension was fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS for 10 min followed by two washes in PBS by centrifugation at 2000 g at room temperature for 5 min. The pellet was resuspended in PBS and 20-μl drops were placed onto glass slides to dry. The primary antibodies used were chicken polyclonal antibody against the V-ATPase B1 subunit (0.3 μg/ml, made and purified in our laboratory; Breton et al., 2000; Herak-Kramberger et al., 2001), anti-Src antibody (1:200, Cat. # 2109, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), anti-CD63 antibody (20 μg/ml, Cat. # E-A-63818, Elabscience, Houston, TX), rabbit anti-V-ATPase a4 subunit antibody (2.5 μg/ml; made and purified in our laboratory; Battistone et al., 2018) and anti-Cx3cl1 (2 μg/ml, Cat. # sc-7227, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Cx3cl1 staining was abolished when the Cx3cl1 antibody was pre-incubated with the immunizing peptide (2 μg/ml). The secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories) used were: donkey Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-chicken IgY (30 μg/ml, Cat. # 703-545-155), donkey Cy3-conjugated anti-chicken IgY (7.5 μg/ml, Cat. # 703-165-155), donkey Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated anti-goat-IgG (7.5 μg/ml, Cat. # 705-605-147) and donkey Cy3-conjugated anti-rabbit-IgG (7.5 μg/ml, Cat. # 711-165-152). All antibodies were diluted in DAKO medium (Dako, Carpinteria, CA). Slides were mounted with Vectashield mounting medium containing the DNA marker DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and were examined using a Zeiss LSM800 confocal microscope equipped with Airyscan high-resolution capability (Zeiss Laboratories).

Animal model of epididymitis

Intravasal-epididymal injection was performed as previously described (Silva et al., 2018). Mice were anesthetized with isofluorane (Baxter, Deerfield, IL). A single abdominal incision was made to expose the proximal portion of the vas deferens (adjacent to the epididymis). LPS (25 μg, S-form; purity ≥99.9%, 1 mg/ml endotoxin units, 25 μl; Innaxon, Oakield Close, UK), IFN-γ (10,000 units, 20 μl, PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ) or saline were injected into the vas deferens using a 31-G needle. The injection was made bilaterally in a retrograde direction as near as possible to the cauda epididymis. Mice were euthanized at 6 h or 24 h post-treatment for cell sorting and mRNA extraction, and immune cell recruitment analysis.

Pro-inflammatory molecule expression in EGFP+ CCs

Total RNA was isolated from EGFP+ cells as described above. cDNA was synthesized from 1000 pg RNA by using the SuperScript VILO cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed by using the Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Life Technologies) and primers listed in Table S7. Results are reported as mean±s.e.m. using the formula −ΔCt=−[Ct target gene – Ct control gene Gapdh]. Relative expression is derived from 2−ΔΔCt where −ΔΔCt=ΔCt treated group−ΔCt control group.

Flow cytometry analysis

Epididymal single-cell suspensions were generated as previously described (Da Silva et al., 2011). Briefly, caput, corpus and cauda tissues were incubated for 30 min at 37°C with gentle shaking in dissociation medium (RPMI 1640 with 0.5 mg/ml collagenase type I and 0.5 mg/ml collagenase type II). After enzymatic digestion, cells were passed through a 70 µm nylon mesh strainer, washed in PBS with 2% fetal bovine serum and 2 mM EDTA. Cell suspensions were incubated with a cocktail of anti-mouse Ig antibodies (1:100) against PE/Cy7 F4/80 (clone BM8), BV711 CD45 (clone 30-F11), APC/Cy7 CD11b (clone M1/711), FITC LY6C (clone AL-21), PE LY6G (clone 1A8), and CD64 Alexa Fluor 647 (clone X54-5/7.1). Antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA) or BioLegend (San Diego, CA).

Evaluation of EGFP+ vesicle–sperm complexes using imaging flow cytometry

Caput epididymal mouse sperm were collected from B1-EGFP transgenic and WT mice by placing minced (three cuts) caput epididymis in PBS for 15 min at 37°C. To evaluate EGFP+ events, sperm were analyzed on an Imaging Flow Cytometer (ImageStreamΧ Mark II, AMNIS, Seattle, WA; now a part of Luminex Corporation). The bright-field (BF ch01) and the 488 nm (ch02) channel for EGFP were used for data acquisition. Multiple 100,000 event files were collected at 40× magnification. Additionally, a focus threshold for the exclusion of out of focus events [gradient root mean square (gradient RMS) for channel 01 of ≥40] was held. The acquisition rate was ∼12,000 events per minute. Sperm images were analyzed using the provided analysis software IDEAS v6.2.64. WT mice were used as controls to determine the threshold for green fluorescence positivity. The aspect ratio and the area of the BF images were set to analyze events compatible with sperm morphology.

Electron microscopy

Mouse epididymis IS from B1-EGFP transgenic mice were immersion fixed immediately upon excision in a PFA-lysine periodate solution (PLP, as previously described; Paunescu et al., 2004) for 4 h on a gentle rotator at room temperature, then cut up into small pieces and allowed to infiltrate further in the PLP fixative overnight at 4°C. The next day, tissue specimens were post-fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer for several hours, rinsed in cacodylate buffer, infiltrated with 1% osmium tetroxide for 1 h, then rinsed several times again in cacodylate buffer. Tissue blocks were then dehydrated through a graded series of ethanol to 100%, dehydrated briefly in 100% propylene oxide, then allowed to pre-infiltrate at least 2 h in a 2:1 mix of propylene oxide and Eponate resin and overnight at room temperature in a 1:1 mix of propylene oxide and Eponate resin (Ted Pella, Redding, CA) on a gentle rotator. The following day, specimens were allowed to infiltrate at least 2 h in a 2:1 mix of Eponate and propylene oxide, then several hours in fresh 100% Eponate resin. The tissue blocks were placed into BEEM capsules with fresh 100% Eponate resin and specimens allowed to polymerize for 24–48 h at 60°C. Thin (70 nm) sections were cut using a Leica EM UC7 ultramicrotome, collected onto formvar-coated grids, stained with uranyl acetate and Reynold's lead citrate and examined in a JEOL JEM 1011 transmission electron microscope at 80 kV. Images were collected using an AMT digital imaging system with proprietary image capture software (Advanced Microscopy Techniques, Danvers, MA).

Statistical analysis

The numeric data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism (Version 8; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Data were analyzed using the Student's t-test, or one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey's post hoc test. A value of P<0.05 was considered significant. Data are expressed as the mean±s.e.m. For each set of data, at least four different animals (n) were included for each condition. Collection, analysis and interpretation of data were conducted by a researcher that was blind to the identity of the samples.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the HSCI-CRM Flow Cytometry Facility (MGH, Boston, MA), in particular Maris Handley and Amy Galvin Watt for their guidance and assistance for the sorting and flow cytometry analysis. The Amnis ImageStream MkII located in the Department of Pathology Flow, Image and Mass Cytometry Core was purchased using an NIH Shared Instrumentation Grant 1S10OD012027-01A1 AMNIS ISX (FIP). In addition, we thank Mr. Ferran Barrachina Villalonga for his help with the AMNIS experiments. Electron microscopy and confocal microscopy were performed in the Microscopy Core facility of the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Center for Systems Biology/Program in Membrane Biology which receives support from Boston Area Diabetes and Endocrinology Research Center (BADERC) award DK57521 and Center for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease grant DK43351. The Zeiss LSM800 microscope was acquired using an NIH Shared Instrumentation Grant S10-OD-021577-01.

Footnotes

Competing interests

S.B. is a co-founder of Kantum Pharma (previously ‘Kantum Diagnostics, Inc.’). Dr Breton and her spouse each own equity in the privately held company and Dr Breton is an inventor on patents covering technology that has been licensed to the company through the hospital. Kantum is developing a diagnostic and therapeutic combination to prevent and treat Acute Kidney Injury. S.B.’s interests were reviewed and are managed by Massachusetts General Hospital and Partners HealthCare in accordance with their conflict of interest policies.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: M.A.B., D.B., S.B.; Methodology: M.A.B., R.G.S., D.C., S.B.; Validation: M.A.B., R.G.S., S.B.; Formal analysis: M.A.B.; Investigation: M.A.B., A.C.M., D.C., A.V.N.; Resources: M.A.B.; Writing - original draft: M.A.B.; Writing - review & editing: R.G.S., A.C.M., A.V.N., D.B., S.B.; Visualization: M.A.B., D.B., S.B.; Supervision: S.B.; Funding acquisition: S.B.

Funding

This work was supported by a Lalor Foundation Fellowship (to M.A.B.), and National Institutes of Health grants DK042956 (to D.B.), HD040793 (to S.B.), HD069623 (to S.B.) and DK097124 (to S.B.). S.B. is the recipient of the Richard Moerschner Endowed MGH Research Institute Chair in Men's Health. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Data availability

RNA-seq dataset from CCs have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession number GSE130619.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information available online at http://jcs.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/jcs.233239.supplemental

References

- Aitken R. J., Nixon B., Lin M., Koppers A. J., Lee Y. H. and Baker M. A. (2007). Proteomic changes in mammalian spermatozoa during epididymal maturation. Asian J. Androl. 9, 554-564. 10.1111/j.1745-7262.2007.00280.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders S., Pyl P.T. and Huber W (2015). HTSeq – a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31, 166-169. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aumüller G., Wilhelm B. and Seitz J. (1999). Apocrine secretion--fact or artifact? Ann. Anat. 181, 437-446. 10.1016/S0940-9602(99)80020-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azroyan A., Cortez-Retamozo V., Bouley R., Liberman R., Ruan Y. C., Kiselev E., Jacobson K. A., Pittet M. J., Brown D. and Breton S. (2015). Renal intercalated cells sense and mediate inflammation via the P2Y14 receptor. PLoS ONE 10, e0121419 10.1371/journal.pone.0121419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks F. C., Calvert R. C. and Burnstock G. (2010). Changing P2X receptor localization on maturing sperm in the epididymides of mice, hamsters, rats, and humans: a preliminary study. Fertil. Steril. 93, 1415-1420. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.02.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battistone M. A., Nair A. V., Barton C. R., Liberman R. N., Peralta M. A., Capen D. E., Brown D. and Breton S. (2018). Extracellular adenosine stimulates vacuolar ATPase-dependent proton secretion in medullary intercalated cells. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 29, 545-556. 10.1681/ASN.2017060643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battistone M. A., Merkulova M., Park Y. J., Peralta M. A., Gombar F., Brown D. and Breton S. (2019). Unravelling purinergic regulation in the epididymis: activation of V-ATPase-dependent acidification by luminal ATP and adenosine. J. Physiol. 597, 1957-1973. 10.1113/JP277565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belleannée C., Da Silva N., Shum W. W., Brown D. and Breton S. (2010). Role of purinergic signaling pathways in V-ATPase recruitment to apical membrane of acidifying epididymal clear cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 298, C817-C830. 10.1152/ajpcell.00460.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belleannée C., Labas V., Teixeira-Gomes A. P., Gatti J. L., Dacheux J. L. and Dacheux F. (2011). Identification of luminal and secreted proteins in bull epididymis. J. Proteomics 74, 59-78. 10.1016/j.jprot.2010.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomqvist S. R., Vidarsson H., Söder O. and Enerbäck S. (2006). Epididymal expression of the forkhead transcription factor Foxi1 is required for male fertility. EMBO J. 25, 4131-4141. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breton S. and Brown D. (2013). Regulation of luminal acidification by the V-ATPase. Physiology (Bethesda) 28, 318-329. 10.1152/physiol.00007.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breton S., Wiederhold T., Marshansky V., Nsumu N. N., Ramesh V. and Brown D. (2000). The B1 subunit of the H+ATPase is a PDZ domain-binding protein. Colocalization with NHE-RF in renal B-intercalated cells. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 18219-18224. 10.1074/jbc.M909857199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breton S., Ruan Y. C., Park Y.-J. and Kim B. (2016). Regulation of epithelial function, differentiation, and remodeling in the epididymis. Asian J. Androl. 18, 3-9. 10.4103/1008-682X.165946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne J. A., Yang R., Leir S.-H., Eggener S. E. and Harris A. (2016). Expression profiles of human epididymis epithelial cells reveal the functional diversity of caput, corpus and cauda regions. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 22, 69-82. 10.1093/molehr/gav066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabory E., Damon C., Lenoir A., Henry-Berger J., Vernet P., Cadet R., Saez F. and Drevet J. R. (2010). Mammalian glutathione peroxidases control acquisition and maintenance of spermatozoa integrity. J. Anim. Sci. 88, 1321-1331. 10.2527/jas.2009-2583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnery H. R., Pearlman E. and McMenamin P. G. (2008). Cutting edge: Membrane nanotubes in vivo: a feature of MHC class II+ cells in the mouse cornea. J. Immunol. 180, 5779-5783. 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.5779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke H. J. (2018). Regulation of germ cell development by intercellular signaling in the mammalian ovarian follicle. Wiley Interdiscip Rev. Dev. Biol. 7, e294 10.1002/wdev.294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Ros V. G., Munoz M. W., Battistone M. A., Brukman N. G., Carvajal G., Curci L., Gomez-ElIas M. D., Cohen D. B. and Cuasnicu P. S. (2015). From the epididymis to the egg: participation of CRISP proteins in mammalian fertilization. Asian J. Androl. 17, 711-715. 10.4103/1008-682X.155769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva N. and Smith T. B. (2015). Exploring the role of mononuclear phagocytes in the epididymis. Asian J. Androl. 17, 591-596. 10.4103/1008-682X.153540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva N., Pisitkun T., Belleannée C., Miller L. R., Nelson R., Knepper M. A., Brown D. and Breton S. (2010). Proteomic analysis of V-ATPase-rich cells harvested from the kidney and epididymis by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 298, C1326-C1342. 10.1152/ajpcell.00552.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva N., Cortez-Retamozo V., Reinecker H.-C., Wildgruber M., Hill E., Brown D., Swirski F. K., Pittet M. J. and Breton S. (2011). A dense network of dendritic cells populates the murine epididymis. Reproduction 141, 653-663. 10.1530/REP-10-0493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobin A., Davis C. A., Schlesinger F., Drenkow J., Zaleski C., Jha S., Batut P., Chaisson M. and Gingeras T. R (2013). STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15-21. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont M., Souriant S., Lugo-Villarino G., Maridonneau-Parini I. and Vérollet C. (2018). Tunneling nanotubes: intimate communication between myeloid cells. Front. Immunol. 9, 43 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzè E., Marafini I., De Simone V., Monteleone I., Caprioli F., Colantoni A., Ortenzi A., Crescenzi F., Izzo R., Sica G. et al. (2016). Interleukin-34 induces Cc-chemokine ligand 20 in gut epithelial cells. J. Crohns Colitis 10, 87-94. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenette G., Girouard J., D'Amours O., Allard N., Tessier L. and Sullivan R. (2010). Characterization of two distinct populations of epididymosomes collected in the intraluminal compartment of the bovine cauda epididymis. Biol. Reprod. 83, 473-480. 10.1095/biolreprod.109.082438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gesase A. P. and Satoh Y. (2003). Apocrine secretory mechanism: recent findings and unresolved problems. Histol. Histopathol. 18, 597-608. 10.14670/HH-18.597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyonnet B., Dacheux F., Dacheux J.-L. and Gatti J.-L. (2011). The epididymal transcriptome and proteome provide some insights into new epididymal regulations. J. Androl. 32, 651-664. 10.2164/jandrol.111.013086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedger M. P. (2011). Immunophysiology and pathology of inflammation in the testis and epididymis. J. Androl. 32, 625-640. 10.2164/jandrol.111.012989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herak-Kramberger C. M., Breton S., Brown D., Kraus O. and Sabolic I. (2001). Distribution of the vacuolar H+ atpase along the rat and human male reproductive tract. Biol. Reprod. 64, 1699-1707. 10.1095/biolreprod64.6.1699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermo L. and Jacks D. (2002). Nature's ingenuity: bypassing the classical secretory route via apocrine secretion. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 63, 394-410. 10.1002/mrd.90023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermo L., Adamali H. I. and Andonian S. (2000). Immunolocalization of CA II and H+ V-ATPase in epithelial cells of the mouse and rat epididymis. J. Androl. 21, 376-391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen L. J., Stuart-Tilley A. K., Peters L. L., Lux S. E., Alper S. L. and Breton S. (1999). Immunolocalization of AE2 anion exchanger in rat and mouse epididymis. Biol. Reprod. 61, 973-980. 10.1095/biolreprod61.4.973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston D. S., Jelinsky S. A., Bang H. J., DiCandeloro P., Wilson E., Kopf G. S. and Turner T. T. (2005). The mouse epididymal transcriptome: transcriptional profiling of segmental gene expression in the epididymis. Biol. Reprod. 73, 404-413. 10.1095/biolreprod.105.039719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston D. S., Turner T. T., Finger J. N., Owtscharuk T. L., Kopf G. S. and Jelinsky S. A. (2007). Identification of epididymis-specific transcripts in the mouse and rat by transcriptional profiling. Asian J. Androl. 9, 522-527. 10.1111/j.1745-7262.2007.00317.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jrad-Lamine A., Henry-Berger J., Damon-Soubeyrand C., Saez F., Kocer A., Janny L., Pons-Rejraji H., Munn D. H., Mellor A. L., Gharbi N. et al. (2013). Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (ido1) is involved in the control of mouse caput epididymis immune environment. PLoS ONE 8, e66494 10.1371/journal.pone.0066494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung S., Aliberti J., Graemmel P., Sunshine M. J., Kreutzberg G. W., Sher A. and Littman D. R. (2000). Analysis of fractalkine receptor CX(3)CR1 function by targeted deletion and green fluorescent protein reporter gene insertion. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 4106-4114. 10.1128/MCB.20.11.4106-4114.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch S., Acebron S. P., Herbst J., Hatiboglu G. and Niehrs C. (2015). Post-transcriptional Wnt signaling governs epididymal sperm maturation. Cell 163, 1225-1236. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krapf D., Ruan Y. C., Wertheimer E. V., Battistone M. A., Pawlak J. B., Sanjay A., Pilder S. H., Cuasnicu P., Breton S. and Visconti P. E. (2012). cSrc is necessary for epididymal development and is incorporated into sperm during epididymal transit. Dev. Biol. 369, 43-53. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.06.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labas V., Spina L., Belleannee C., Teixeira-Gomes A.-P., Gargaros A., Dacheux F. and Dacheux J.-L. (2015). Analysis of epididymal sperm maturation by MALDI profiling and top-down mass spectrometry. J. Proteomics 113, 226-243. 10.1016/j.jprot.2014.09.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.-W., Verlander J. W., Handlogten M. E., Han K.-H., Cooke P. S. and Weiner I. D. (2013). Expression of the rhesus glycoproteins, ammonia transporter family members, RHCG and RHBG in male reproductive organs. Reproduction 146, 283-296. 10.1530/REP-13-0154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist R. L., Shakhar G., Dudziak D., Wardemann H., Eisenreich T., Dustin M. L. and Nussenzweig M. C. (2004). Visualizing dendritic cell networks in vivo. Nat. Immunol. 5, 1243-1250. 10.1038/ni1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M., Guo S., Hibbert J. M., Jain V., Singh N., Wilson N. O. and Stiles J. K. (2011). CXCL10/IP-10 in infectious diseases pathogenesis and potential therapeutic implications. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev. 22, 121-130. 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2011.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou E., Fujisawa S., Barlas A., Romin Y., Manova-Todorova K., Moore M. A. and Subramanian S. (2012). Tunneling Nanotubes: A new paradigm for studying intercellular communication and therapeutics in cancer. Commun. Integr. Biol. 5, 399-403. 10.4161/cib.20569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan R. I. (2002). Basis, diagnosis and treatment of immunological infertility in men. J. Reprod. Immunol. 57, 35-45. 10.1016/S0165-0378(02)00014-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel V., Pilatz A., Hedger M. P. and Meinhardt A. (2015). Epididymitis: revelations at the convergence of clinical and basic sciences. Asian J. Androl. 17, 756-763. 10.4103/1008-682X.155770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller R. L., Zhang P., Smith M., Beaulieu V., Paunescu T. G., Brown D., Breton S. and Nelson R. D. (2005). V-ATPase B1-subunit promoter drives expression of EGFP in intercalated cells of kidney, clear cells of epididymis and airway cells of lung in transgenic mice. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 288, C1134-C1144. 10.1152/ajpcell.00084.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mital P., Hinton B. T. and Dufour J. M. (2011). The blood-testis and blood-epididymis barriers are more than just their tight junctions. Biol. Reprod. 84, 851-858. 10.1095/biolreprod.110.087452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negishi M., Izumi Y., Aleemuzzaman S., Inaba N. and Hayakawa S. (2011). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced Interferon (IFN)-gamma production by decidual mononuclear cells (DMNC) is interleukin (IL)-2 and IL-12 dependent. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 65, 20-27. 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00856.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon B., De Iuliis G. N., Hart H. M., Zhou W., Mathe A., Bernstein I. R., Anderson A. L., Stanger S. J., Skerrett-Byrne D. A., Jamaluddin M. F. B. et al. (2019). Proteomic profiling of mouse epididymosomes reveals their contributions to post-testicular sperm maturation. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 18, S91-S108. 10.1074/mcp.RA118.000946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okasaki I. J. and Pryor J. L. (2002). Cancer of the epididymis. In The Epididymis from Molecules to Clinic Practice (ed. Robaire B. and Hinton B.). pp. 555-561. New York: Kluwar Academic/Plenum Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Orgebin-Crist M. C. (1969). Studies on the function of the epididymis. Biol. Reprod. 1 Suppl. 1, 155-175. 10.1095/biolreprod1.Supplement_1.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palladino M. A., Johnson T. A., Gupta R., Chapman J. L. and Ojha P. (2007). Members of the Toll-like receptor family of innate immunity pattern-recognition receptors are abundant in the male rat reproductive tract. Biol. Reprod. 76, 958-964. 10.1095/biolreprod.106.059410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palladino M. A., Savarese M. A., Chapman J. L., Dughi M.-K. and Plaska D. (2008). Localization of Toll-like receptors on epididymal epithelial cells and spermatozoa. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 60, 541-555. 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2008.00654.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastor-Soler N. M., Hallows K. R., Smolak C., Gong F., Brown D. and Breton S. (2008). Alkaline pH- and cAMP-induced V-ATPase membrane accumulation is mediated by protein kinase A in epididymal clear cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 294, C488-C494. 10.1152/ajpcell.00537.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paunescu T. G., Da Silva N., Marshansky V., McKee M., Breton S. and Brown D. (2004). Expression of the 56-kDa B2 subunit isoform of the vacuolar H(+)-ATPase in proton-secreting cells of the kidney and epididymis. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 287, C149-C162. 10.1152/ajpcell.00464.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paunescu T. G., Shum W. W. C., Huynh C., Lechner L., Goetze B., Brown D. and Breton S. (2014). High-resolution helium ion microscopy of epididymal epithelial cells and their interaction with spermatozoa. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 20, 929-937. 10.1093/molehr/gau052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovic-Djergovic D., Popovic M., Chittiprol S., Cortado H., Ransom R. F. and Partida-Sánchez S. (2015). CXCL10 induces the recruitment of monocyte-derived macrophages into kidney, which aggravate puromycin aminonucleoside nephrosis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 180, 305-315. 10.1111/cei.12579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierucci-Alves F., Midura-Kiela M. T., Fleming S. D., Schultz B. D. and Kiela P. R. (2018). Transforming growth factor beta signaling in dendritic cells is required for immunotolerance to sperm in the epididymis. Front. Immunol. 9, 1882 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrement C., Sun-Wada G.-H., Da Silva N., McKee M., Marshansky V., Brown D., Futai M. and Breton S. (2006). Distinct expression patterns of different subunit isoforms of the V-ATPase in the rat epididymis. Biol. Reprod. 74, 185-194. 10.1095/biolreprod.105.043752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rejraji H., Sion B., Prensier G., Carreras M., Motta C., Frenoux J. M., Vericel E., Grizard G., Vernet P. and Drevet J. R. (2006). Lipid remodeling of murine epididymosomes and spermatozoa during epididymal maturation. Biol. Reprod. 74, 1104-1113. 10.1095/biolreprod.105.049304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro C. M., Silva E. J., Hinton B. T. and Avellar M. C. (2016). beta-defensins and the epididymis: contrasting influences of prenatal, postnatal, and adult scenarios. Asian J. Androl. 18, 323-328. 10.4103/1008-682X.168791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robaire B. H. B. and Orgebin-Crist M. (2006). The epididymis. Knobil and Neill's Physiology of Reproduction (Third Edition) 1, 1071-1148. 10.1016/B978-012515400-0/50027-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson M. D., McCarthy D. J. and Smyth G. K (2010). edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139-140. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy J., Kim B., Hill E., Visconti P., Krapf D., Vinegoni C., Weissleder R., Brown D. and Breton S. (2016). Tyrosine kinase-mediated axial motility of basal cells revealed by intravital imaging. Nat. Commun. 7, 10666 10.1038/ncomms10666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan Y. C., Wang Y., Da Silva N., Kim B., Diao R. Y., Hill E., Brown D., Chan H. C. and Breton S. (2014). CFTR interacts with ZO-1 to regulate tight junction assembly and epithelial differentiation through the ZONAB pathway. J. Cell Sci. 127, 4396-4408. 10.1242/jcs.148098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustom A., Saffrich R., Markovic I., Walther P. and Gerdes H. H. (2004). Nanotubular highways for intercellular organelle transport. Science 303, 1007-1010. 10.1126/science.1093133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder K., Hertzog P. J., Ravasi T. and Hume D. A. (2004). Interferon-gamma: an overview of signals, mechanisms and functions. J. Leukoc. Biol. 75, 163-189. 10.1189/jlb.0603252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shum W. W., Da Silva N., Belleannee C., McKee M., Brown D. and Breton S. (2011a). Regulation of V-ATPase recycling via a RhoA- and ROCKII-dependent pathway in epididymal clear cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 301, C31-C43. 10.1152/ajpcell.00198.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shum W. W. C., Ruan Y. C., Da Silva N. and Breton S. (2011b). Establishment of cell-cell cross talk in the epididymis: control of luminal acidification. J. Androl. 32, 576-586. 10.2164/jandrol.111.012971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva E. J. R., Ribeiro C. M., Mirim A. F. M., Silva A. A. S., Romano R. M., Hallak J. and Avellar M. C. W. (2018). Lipopolysaccharide and lipotheicoic acid differentially modulate epididymal cytokine and chemokine profiles and sperm parameters in experimental acute epididymitis. Sci. Rep. 8, 103 10.1038/s41598-017-17944-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sipilä P., Jalkanen J., Huhtaniemi I. T. and Poutanen M. (2009). Novel epididymal proteins as targets for the development of post-testicular male contraception. Reproduction 137, 379-389. 10.1530/REP-08-0132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skerget S., Rosenow M. A., Petritis K. and Karr T. L. (2015). Sperm proteome maturation in the mouse epididymis. PLoS ONE 10, e0140650 10.1371/journal.pone.0140650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan R. (2015). Epididymosomes: a heterogeneous population of microvesicles with multiple functions in sperm maturation and storage. Asian J. Androl. 17, 726-729. 10.4103/1008-682X.155255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thimon V., Koukoui O., Calvo E. and Sullivan R. (2007). Region-specific gene expression profiling along the human epididymis. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 13, 691-704. 10.1093/molehr/gam051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita K., Freeman B. L., Bronk S. F., LeBrasseur N. K., White T. A., Hirsova P. and Ibrahim S. H. (2016). CXCL10-mediates macrophage, but not other innate immune cells-associated inflammation in murine nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Sci. Rep. 6, 28786 10.1038/srep28786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidarsson H., Westergren R., Heglind M., Blomqvist S. R., Breton S. and Enerback S. (2009). The forkhead transcription factor Foxi1 is a master regulator of vacuolar H-ATPase proton pump subunits in the inner ear, kidney and epididymis. PLoS ONE 4, e4471 10.1371/journal.pone.0004471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voisin A., Whitfield M., Damon-Soubeyrand C., Goubely C., Henry-Berger J., Saez F., Kocer A., Drevet J. R. and Guiton R. (2018). Comprehensive overview of murine epididymal mononuclear phagocytes and lymphocytes: Unexpected populations arise. J. Reprod. Immunol. 126, 11-17. 10.1016/j.jri.2018.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P., Han X., Mo B., Huang G. and Wang C. (2017). LPS enhances TLR4 expression and IFNgamma production via the TLR4/IRAK/NFkappaB signaling pathway in rat pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 16, 3111-3116. 10.3892/mmr.2017.6983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Liu W., Jiang Q., Gong M., Chen R., Wu H., Han R., Chen Y. and Han D. (2019). Lipopolysaccharide-induced testicular dysfunction and epididymitis in mice: a critical role of tumor necrosis factor alphadagger. Biol. Reprod. 100, 849-861. 10.1093/biolre/ioy235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelly S., Muthusubramanian A., Powell J., Johnson S., Hastert M. C. and Cornwall G. A. (2016). Cystatin-related epididymal spermatogenic subgroup members are part of an amyloid matrix and associated with extracellular vesicles in the mouse epididymal lumen. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 22, 729-744. 10.1093/molehr/gaw049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagimachi R., Kamiguchi Y., Mikamo K., Suzuki F. and Yanagimachi H. (1985). Maturation of spermatozoa in the epididymis of the Chinese hamster. Am. J. Anat. 172, 317-330. 10.1002/aja.1001720406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]