Abstract

We examined student‐ and context‐related factors related to whether bullied students tell adults about their plight at school or at home. The sample included 1,266 students in primary (Grades 4–6) and lower secondary (Grades 8–9) schools, who had answered an online questionnaire at two measurement points about 5 months apart and were identified as victims of bullying on the basis of the latter. Only 55.4% of the bullied students had told their situation to someone, and much fewer had told an adult. Telling an adult at home was more common (34.0%) than telling a teacher (20.6%) or some other adult at school (12.7%). In a longitudinal structural equation model (SEM), factors related to increased likelihood of telling an adult were female gender, lower grade level, the chronicity of victimization, perceived negative teacher attitude towards bullying (teacher not tolerating bullying), and perceived peer support for victims (classmates’ tendency to defend students who are victimized).

Keywords: Bullying, victimization, telling, reporting, popularity, bully‐victims, teacher attitudes, participant roles, longitudinal

Introduction

Far too often, teachers and other adults at school fail to recognize students targeted by bullying. This can be understood in the light of evidence that most bullying incidents take place in settings where adults are not present, for example in the school yard or hallways during recess time (Fekkes, Pijpers & Verloove‐Vanhorick, 2005). In Haataja, Sainio, Turtonen and Salmivalli's (2016) study, only one in four chronically victimized students came to the attention of school personnel. The failure to recognize victims leads to lack of appropriate intervention, and continued bullying. Yablon (2017) suggests that victimized students should be regarded as key informants in the detection of violence in the school context. However, many students targeted by bullying do not report it – the prevalence of telling someone about victimization has been found to be around 70% at best (Hunter, Boyle & Warden, 2004; Oliver & Candappa, 2007; Unnever & Cornell, 2004).

When victimized students do tell someone, they tend to choose telling friends rather than adults (e.g., Hunter et al., 2004), and prefer telling parents to telling teachers (Fekkes et al., 2005; Smith & Shu, 2000). Telling a teacher about being victimized is very rare with 3%–18% of victims telling only a teacher or a teacher as well some other person (Hunter et al., 2004; Smith & Shu, 2000). Telling some other member of the school personnel is even more infrequent, only 3%–9% (Smith & Shu, 2000). This may be due to the victimized students’ expectation of the situation getting worse as a result of teacher involvement (Newman & Murray, 2005; Smith & Shu, 2000). However, reporting bullying to adults is crucial. In Novick and Isaacs’ (2010) study, being told about victimization was the best single predictor of teacher intervention, exceeding the effect of direct teacher observations. Smith and Shu (2000) found that the most common outcome of telling an adult, who then intervened in the bullying, was that matters got better. These findings highlight the importance of reporting bullying to adults; it may be the best way to get help when bullying occurs outside adult surveillance.

There is still little research concerning why some victims choose to tell about their experiences whereas others remain silent. It is necessary to understand the factors related to telling about victimization in order to make appropriate efforts to encourage help seeking. The purpose of this study is to look into the characteristics of the victimized student and those of the social context, as perceived by the student, which are associated with a student's decision to tell adults about victimization.

Student characteristics related to telling

There is vast evidence on gender differences in reporting experienced bullying. Girls are more likely than boys to tell someone about being victimized, as well as to tell adults specifically (Aceves, Hinshaw, Mendoza‐Denton & Page‐Gould, 2010; Cortes & Kochenderfer‐Ladd, 2014; Hunter et al., 2004; Smith & Shu, 2000; Unnever & Cornell, 2004). Girls and boys seem to use different coping strategies when faced with bullying: boys appear to be more likely than girls to react aggressively or to blame themselves (Aceves et al., 2010; Cortes & Kochenderfer‐Ladd, 2014). Seeking social support seems to be more likely for girls than boys; girls might perceive telling as an effective strategy to cope with negative emotions and to stop the bullying (Hunter et al., 2004). According to Unnever and Cornell (2004), when boys do tell about bullying, they tend to tell adults instead of peers. Girls seem to do the opposite (Fekkes et al., 2005). This preference may be due to stronger sanctions in boys’ peer groups against the expression of vulnerabilities and to a norm according to which boys are expected to handle their problems on their own.

Studies on age and grade effects all point to the direction that younger students are more willing to tell adults about being bullied than older students (Aceves et al., 2010; Cortes & Kochenderfer‐Ladd, 2014; Oliver & Candappa, 2007; Smith & Shu, 2000; Unnever & Cornell, 2004). When older students choose to tell about victimization, they prefer telling a peer to telling an adult (Oliver & Candappa, 2007; Unnever & Cornell, 2004). This may result from older students’ increased need for autonomy (as opposed to willingness to ask for help from adults) and their ability to form protective friendships in which support is provided in case of victimization.

The chronicity of victimization has also been suggested to be related to students’ responding to bullying. Yablon (2017) suggests that the frequency and gravity of victimization may have an effect on the victims’ willingness to tell about their plight: When bullying does not stop on its own, help is sought. A study by Unnever and Cornell (2004) supports this view: telling about victimization was more likely among students who had been bullied for longer periods of time.

There is evidence that a student's popularity buffers, to some extent, against victimization (Sainio, Veenstra, Huitsing & Salmivalli, 2012; Sentse, Kretschmer & Salmivalli, 2015; Sijtsema, Veenstra, Lindenberg & Salmivalli, 2009): in their pursuit for high status and popularity, bullies are more likely to choose victims who have little power in the peer group. It should not, however, be assumed that a popular student cannot be a victim of bullying (Sainio et al., 2012).

There is no research concerning the actions of popular vs. unpopular students when faced with bullying. However, their reactions to teasing, threats, and physical harassment in general have been examined by Newman and Murray (2005), who found that unpopular students opted for telling a teacher more frequently in milder cases of peer harassment (i.e., teasing) than peers of average or high popularity. It was suggested that unpopular students take teasing more seriously than average and popular students and rely more on the teacher to solve minor problems, whereas average and popular students often try to resolve such situations by themselves. Popular students may be less willing to report minor incidents to teachers out of the fear of retribution from the perpetrator, as well as due to acknowledged social rules according to which it is uncool to tell the teacher. They may not want to risk their status in less serious cases of harassment. However, popular students report more serious cases of, for example, physical violence, as often as less popular ones do (Newman & Murray, 2005).

Some students who are victimized behave aggressively themselves. According to a review by Salmivalli (2010), the prevalence of bully‐victims is approximately 4%–6%. Bully‐victims are dysregulated and hot‐tempered; such features may be perceived as disruptive by teachers. This may explain why bully‐victims, regardless of their frequent involvement in bullying (Yang & Salmivalli, 2013), are unlikely to be identified as victims and may receive less support from teachers than other victims (Haataja et al., 2016).

Bowers, Smith and Binney (1994) found that bully‐victims had more troubled relationships with their parents than victims, bullies, and control children. Their perceptions of their parents reflected inconsistent discipline and monitoring practices (both neglect and over‐protection) with little affective warmth. Moreover, while they perceived themselves as having relatively more power in the family than other groups of children, they also held negative perceptions of themselves (see also Veenstra, Lindenberg, Oldehinkel, De Winter, Verhulst & Ormel, 2005). These findings raise questions concerning their likelihood of telling adults about victimization. Bully‐victims might not expect to get support either at school or at home. Research on bully‐victims’ telling about their victimization experiences is so far non‐existent. In the light of previous studies, it seems that failing to report victimization, combined with bully‐victims’ unique risk factors, would pose a major threat to their wellbeing.

Characteristics of the social context related to telling

Classrooms differ in how the students tend to respond when witnessing bullying. In some classrooms, the peer context seems to approve and encourage bullying, whereas in others students support and defend those who are vulnerable (Salmivalli, Voeten, & Poskiparta, 2011). Victimized students who perceive their classroom climate as supportive and defending are likely to trust classmates in helping to stop the bullying, and thus it may be easier for them to tell about victimization and allow adult intervention. This is what Unnever and Cornell (2004) found: telling about bullying in general and telling adults in particular was linked to perceiving the school culture as not tolerating bullying. In their study, school culture was measured by questions about perceptions of bystander behaviors and of the teachers’ and students’ efforts to stop the bullying.

Besides classmates, teachers are an important part of the students’ social context. Students’ perceptions of teacher actions during conflicts have been found to be related to students’ willingness to report bullying to teachers (Aceves et al., 2010; Cortes & Kochenderfer‐Ladd, 2014). Adolescents who perceive teachers’ actions as active and effective seem to be more willing to seek help from them, instead of reacting aggressively, than adolescents with more negative perceptions of teacher actions.

Saarento, Kärnä, Hodges and Salmivalli (2013) as well as Cortes and Kochenderfer‐Ladd (2014) found that victimization was less common in classrooms and schools where teachers were perceived to have negative attitudes towards bullying Some teachers may effectively create classroom climates where bullying is taken seriously and students are encouraged to report victimization. In other classrooms, reports of violence may be dismissed and bullying is allowed to thrive. Previous studies have found that teachers’ beliefs about bullying affect their intervention strategies in cases of bullying (Kochenderfer‐Ladd & Pelletier, 2008). By failing to express disapproval of bullying or take appropriate actions to intervene, teachers may convey a message to their students that bullying is, in fact, acceptable (Saarento et al., 2013). This can be anticipated to affect the students’ willingness to report cases of victimization to teachers.

The current study

The aim of the current study is to look into a comprehensive set of predictors that might explain why some victims choose to tell adults at home or at school about being bullied. We focus on telling adults, due to their potential to take action to stop the bullying.

Regarding student‐related factors associated with telling adults, we expect to find gender and grade effects consistent with previous research. Thus, girls as compared to boys, and students in lower as compared to those in higher grades, are expected to be more likely to report bullying. Furthermore, we expect that chronicity of bullying is related to disclosure so that students who have experienced longer periods of bullying are more likely to report bullying than those who have been bullied for a shorter period of time.

In the light of previous studies, we hypothesize that popular students are less willing to tell about victimization due to the fear of looking “uncool” or vulnerable and thus losing their status among peers. It is further expected that victims who also bully others (i.e., bully‐victims) are less likely to tell adults about their plight than pure victims. Keeping in mind that bully‐victims have been found to experience more inconsistent and emotionally cold parenting than other students, it is likely that these students are hesitant in telling about bullying at home, as they may not perceive their parents as being willing to help. They may not expect support from teachers and adults at school because their aggressive behavior and school‐related problems may have caused challenges in the teacher‐student relationship and may be perceived by the adults as merely “bad behavior.”

Moving on to context‐related factors, it is hypothesized that perceiving one's social context as not tolerating bullying encourages telling. In the current study, perceptions of two aspects of such a context are considered: peers’ support for victimized students and teachers’ attitudes towards bullying. In Finland, students spend most of their classroom time with a homeroom teacher in Grades 1–6. In Grades 7–9, they continue to have a main homeroom teacher who teaches some of the subjects and is considered to be in charge of that particular group of students. Because of the homeroom teacher's unique role, the study focuses on student perceptions of the attitudes of homeroom teachers. Finally, as the current study utilizes data collected as part of the randomized controlled trial of the KiVa antibullying program (Kärnä, Voeten, Little, Alanen, Poskiparta & Salmivalli, 2013; Kärnä, Voeten, Little, Poskiparta, Kaljonen & Salmivalli, 2011), we control for the intervention status of the school.

The current study addresses certain gaps in the existing literature. According to our knowledge, none of the previous studies on students’ telling adults about victimization has used a longitudinal design which has been called for (e.g., by Unnever & Cornell, 2004). We examine the association between predictors at one time point and telling adults about bullying at a later point. In addition, many studies have utilized hypothetical vignettes to study telling intentions (e.g., Aceves et al., 2010; Cortes & Kochenderfer‐Ladd, 2014; Newman & Murray, 2005; Yablon, 2010), whereas we could locate only two that have studied actual telling (DeLara, 2012; Unnever & Cornell, 2004). People do not always act according to their intentions (Seebaß, Schmitz & Gollwitzer, 2013), a phenomenon known as the intention‐behavior gap. In the present study, students targeted by bullying were asked whether they had actually told someone about their plight, which serves to strengthen the extant evidence concerning factors related to intentions of telling and to determine whether similar factors also predict actual telling.

Method

Participants

The participants are a subsample of students involved in the randomized controlled trial of the KiVa antibullying program in Finland (Kärnä et al., 2011, 2013). From the total RCT sample (N = 31,667), students from Grades 4–6 and 8–9 were first selected, resulting in a subsample of 16,135 students. Due to design issues, students in Grades 1–3 and 7 in the RCT sample lack the data on some of the focal variables and were therefore excluded. From among the selected grades, students who at Time 2 reported having been bullied at least two or three times a month during the last couple of months (Solberg & Olweus, 2003) were identified. A total of 91.5% of the students on the selected grades had answered this question. These victimized students (N = 1,266, 40% female) constituted the final sample. They were from 139 Finnish schools (77 serving as intervention and 62 as control schools in the RCT). The mean age of students in was 11.04 years Grades 4–6 and 14.72 years in Grades 8–9. Altogether, 7.3% of the participants reported being born outside Finland.

Procedure

The data were collected from May 2007 to May 2009 during the RCT of the KiVa program. For a complete description of the study procedure, see Kärnä et al. (2011) for Grades 4–6 and Kärnä et al. (2013) for Grades 8 and 9.

The study utilizes data from two measurement points. Students in Grades 4 to 6 first answered the questionnaire in December 2007–January 2008 (Time 1) and then again in May 2008 (Time 2). Students in Grades 8 and 9 first answered the questionnaire in December 2008–January 2009 (Time 1) and again in May 2009 (Time 2). In Finland, the school year starts in August and lasts until June, so the measurement points occurred during the same school year. Thus, the social context of the students remained unchanged with regard to classmates and teachers. The independent variables were measured at Time 1, whereas outcome variables (telling), as well as the chronicity of victimization, were measured at Time 2, resulting in a longitudinal setting. Participants answered the online questionnaires anonymously during school hours. Answers given at the two time points by the same student were matched using individual identification codes given to students at Time 1. Bullying was defined to the participants according to Olweus's (1996) formulation, describing the repetitive and intentional nature of the behavior as well as the victim's difficulty defending him‐ or herself against it. Only one question at a time was presented on a page. The students were informed about the confidentiality of their responses.

Measures

Intervention status

Due to the sample being part of the KiVa trial, each school's condition in the RCT was controlled for in the analyses. Whether a student belonged to an intervention school implementing the anti‐bullying program or to a control school is indicated by a dichotomous variable (0 = control, 1 = intervention).

Chronicity of victimization (T2)

The participants reported how long they had been bullied (0 = a week or two, 1 = a month, 2 = about 6 months, 3 = a year, 4 = several years).

Bullying behavior (T1)

For bullying behavior, peer nominations were used in order to avoid possible biases associated with self‐evaluations, such as social desirability, and to diminish shared method variance (e.g., Smith, 2014). All students in the large data collection from which the sample was derived had marked, from a list of classmates provided on the computer screen, an unlimited number of classmates who behaved in ways described by the three bully items of the Participant Role Questionnaire (Salmivalli & Voeten, 2004): starting the bullying, making others join in the bullying, and always finding new ways of harassing the victim. The students’ bullying behavior was indicated by the proportion score obtained by first dividing the number of nominations a student received per item by the number of all nominating classmates, and then averaging across these three item scores.

Perceived peer support for victims (T1)

As described above, the participants in the large project had nominated classmates who tended to defend or support victimized peers. The three defender items from the Participant Role Questionnaire (Salmivalli & Voeten, 2004) include comforting the victim or encouraging him/her to tell the teacher about the bullying, telling the others to stop bullying, and trying to make the others stop bullying. A measure for given defender nominations was calculated as the average proportion of classmates to whom the subject gave defender nominations for each item. Looking into peer nominations that an individual student has given to classmates as an indicator of perceived classroom climate is a relatively new way to utilize peer nominations (see Saarento, Boulton & Salmivalli, 2015).

Perceived teacher attitude (T1)

Students’ perceptions of their homeroom teacher's attitudes towards bullying were measured by asking the question “How does your teacher think of bullying?” Students answered the question on a 5‐point Likert scale (0 = Good thing, 1 = Does not care, 2 = I don't know, 3 = Bad, 4 = Absolutely wrong) (see Saarento et al., 2013, 2015).

Perceived popularity (T1)

The popularity score, ranging from 0.00 to 1.00, was obtained by dividing the number of “most popular” – nominations received from classmates, divided by the number of classmates.

Telling about victimization (T2)

The participants were asked: “Have you told someone that you have been bullied during the last couple of months?” Participants who reported having told someone were then asked to indicate whom they had told by selecting one or more options from a list provided (homeroom teacher, some other adult at school, parent or a legal guardian, a sibling, a friend, someone else).

Results

Of all study participants, 701 (55.4%) had told someone about being victimized, whereas 554 students (43.8%) had told no one (Table 1). Many students had told several people. Predicting telling siblings and friends about victimization was not a focus of the current study. However, these frequencies are also presented in Table 1, as they provide information about the relative frequency of telling adults at school compared to telling peers and parents. All in all, the data indicate that the most likely persons to tell about victimization are parents and friends, followed by teachers. The students were least likely to have told their siblings about victimization.

Table 1.

Frequencies of telling about victimization

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Told someone about victimization | 701 | 55.4 |

| Told teacher | 261 | 20.6 |

| Told at home | 430 | 34.0 |

| Told some other adult | 161 | 12.7 |

| Told brother or sister | 152 | 12.0 |

| Told friend | 409 | 32.3 |

N S = 1,255–1,266.

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 2. The proportions of missing data per measure were rather low, ranging from 0% to 7.8%. The students had been bullied for a period of time ranging from 6 months to 1 year, but there was large variation in the chronicity of victimization. Bullying others was not very common on average, but there were also students in the sample who were identified as bullying others by many classmates (67.4% of students scored higher than 0 on the bullying scale). The same was true for popularity: while most victimized students were not perceived as popular, there were exceptions. The average of perceived peer support for victims was relatively low, indicating that most students perceived little defending in the classroom. Teacher attitudes towards bullying were mainly perceived as negative.

Table 2.

Ranges, means, and standard deviations of independent and dependent variables

| Range | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male = 1) | – | 0.60 | 0.49 |

| Grade | – | 6.56 | 1.95 |

| Chronicity of victimization | [0–4] | 2.22 | 1.68 |

| Bullying behavior | [0.00–0.72] | 0.08 | 0.12 |

| Perceived peer support | [0.00–1.00] | 0.13 | 0.17 |

| Perceived teacher attitude | [0–4] | 2.95 | 1.29 |

| Popularity | [0.00–1.00] | 0.10 | 0.16 |

| Told teacher | – | 0.21 | 0.41 |

| Told at home | – | 0.34 | 0.47 |

| Told some other adult | – | 0.13 | 0.33 |

N S = 1,167–1,266.

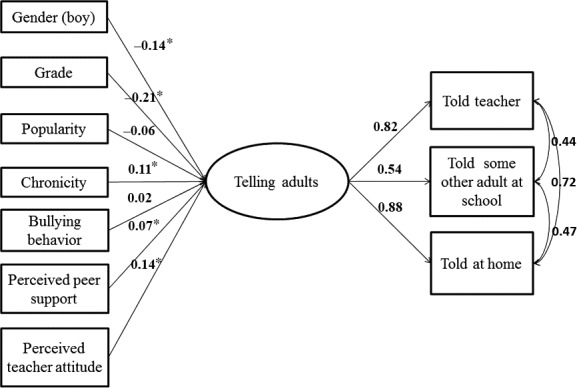

Bivariate correlations among study variables are presented in Table 3. The relatively high correlations (ranging from 0.27 to 0.43) between the three different variables measuring telling various adults (told teacher, told at home and told another adult) support the use of a latent variable measuring telling adults altogether. The measurement model indicated that the items loaded on the expected factor, with loadings ranging from 0.54 to 0.88 (see Fig. 1). The fit of the measurement model could not be defined because of the model being just‐identified. The latent variable accounted for 67% of the variation in telling a teacher, 77% of telling at home and 29% of telling other adults at school.

Table 3.

Correlations among study variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Condition | – | ||||||||||

| 2. Gender | −0.00 | – | |||||||||

| 3. Grade | 0.08** | 0.12*** | – | ||||||||

| 4. Chronicity | 0.03 | 0.05† | 0.23*** | – | |||||||

| 5. Bullying behavior | −0.01 | 0.34*** | −0.04 | 0.02 | – | ||||||

| 6. Perceived peer support | −0.01 | −0.12*** | −0.31*** | −0.10*** | 0.00 | – | |||||

| 7. Perceived teacher attitude | −0.02 | −0.12*** | −0.27*** | −0.12*** | −0.19*** | 0.13** | – | ||||

| 8. Popularity | 0.01 | 0.05† | −0.05 | −0.09** | 0.24*** | 0.06* | −0.06* | – | |||

| 9. Told teacher | 0.03 | −0.07** | −0.24*** | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.12** | 0.12*** | −0.03 | – | ||

| 10. Told at home | 0.00 | −0.15*** | −0.28*** | −0.01 | −0.07* | 0.11** | 0.18*** | −0.04 | 0.43*** | – | |

| 11. Told other adult | 0.03 | −0.05† | 0.07** | 0.08** | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.03 | 0.30*** | 0.27*** | – |

† p < 0.10; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Figure 1.

Factors explaining disclosure about victimization to adults. Statistically significant estimates (p < 0.05) are marked with *. A structural equation model (standardized estimates).

The associations between the independent variables and the latent construct (telling adults) were estimated in the structural part of the SEM model with Mplus version 7. Taking the non‐independence of observations and stratification into account, a sandwich estimator was used to compute adjusted standard errors for the model estimates. Due to the binary factor indicators (i.e., the telling variables), the mean‐ and variance‐adjusted weighted least square, or WLSMV, estimator was used (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012, p. 608). In Mplus, the default is to use all available data, and with WLSMV, this requires the pairwise present approach.

The final SEM is presented in Fig. 1, with further model information in Table 4. All independent variables, except popularity (β = −0.06) and the student's own bullying behavior (β = 0.02) predicted telling adults about bullying statistically significantly. However, as indicated by the point estimate and the confidence interval (−0.13, 0.02), there seemed to be a trend in the direction of popularity decreasing the likelihood of telling. Girls were more likely to tell adults about being bullied than boys (β = −0.14), and younger students were more likely to tell than students on higher grades (β = −0.21). Students who had been bullied longer were more likely to tell than those less chronically bullied (β −= 0.11). Perceptions of teacher attitudes (β = 0.14) and perceived peer support (β = 0.07) were also linked to telling. Students who believed their teacher disapproved of bullying were more likely to tell about bullying than those who saw their teacher as having a more condoning attitude, and students who perceived more peer support to victims in their classroom were more likely to tell than those who perceived less support. Controlling for the intervention status did not affect the results, and its effect on telling was statistically non‐significant (β = 0.052, p = 0.168). Model‐estimated correlations between independent variables are not included in Fig. 1 in favor of simplicity.

Table 4.

Standardized and unstandardized model estimates, standard errors, confidence intervals and p values

| β | SE β | 95% CI β | p β | b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | −0.14 | 0.04 | [−0.22, −0.07] | <0.001 | −0.24 |

| Grade | −0.21 | 0.05 | [−0.30, −0.11] | <0.001 | −0.09 |

| Chronicity | 0.11 | 0.04 | [0.03, 0.19] | 0.005 | 0.05 |

| Bullying behavior | 0.02 | 0.04 | [−0.06, 0.11] | 0.563 | 0.16 |

| Perceived peer support | 0.07 | 0.03 | [0.01, 0.14] | 0.034 | 0.34 |

| Perceived teacher attitude | 0.14 | 0.04 | [0.06, 0.23] | 0.001 | 0.09 |

| Popularity | −0.06 | 0.04 | [−0.13, 0.02] | 0.134 | −0.30 |

The model fit the data relatively well (χ 2 = 99.249, df = 16, p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.064, 90% CI [0.052, 0.076]; CFI = 0.911, WRMR = 0.981). The independent variables explained 12% of the total variance in the latent variable measuring telling adults about victimization.

Discussion

Using a large longitudinal sample, we examined the prevalence of children and adolescent telling others about their plight as a victim of bullying and investigated student‐ and context‐related factors related to disclosure of victimization to adults. Consistent with previous findings, students were more likely to disclose to adults at home, rather than to those at school – whereas telling friends was most likely overall. As expected, gender and grade of the student, chronicity of bullying, and characteristics of the social context were related to telling adults about victimization. The findings provide new insight into factors promoting students’ disclosure of victimization to adults.

Previous findings on students’ reluctance to tell about being bullied were supported by the current study. Only 55.4% of the participants reported having told someone about their plight as victims, which is rarer than indicated by previous literature (Hunter et al., 2004; Oliver & Candappa, 2007; Smith & Shu, 2000). On the other hand, telling adults at school was, although rare, more common than in previous studies: 20.6% of victimized youth had told teachers and 12.7% had told other adults at school (as opposed to 3%–18% and 3%–9%, respectively, found in previous studies). Sample characteristics may explain part of these differences. For instance, the average age of the participants in the present study was higher than that in previous studies, and older students are known to report victimization less than younger ones. There might be something in school cultures, too. Reasons for students not telling adults may include fear of reprisal (Boulton & Underwood, 1992), fear of making things worse (Newman & Murray, 2005), and anticipation of ineffective reactions or over‐reactions from the adults (Aceves et al., 2010; Oliver & Candappa, 2007). Perhaps, Finnish students perceive adults at school as more reliable and approachable than students in other countries do, and are, thus, more likely to tell them. Further research on telling adults at school in different cultural contexts is warranted.

Student‐related predictors of telling

As expected, girls and younger students tended to report victimization more than boys and older students. The gender difference might be due to different social norms and coping strategies among boys and girls (Aceves et al., 2010; Cortes & Kochenderfer‐Ladd, 2014; Unnever & Cornell, 2004). Boys are perhaps often expected to handle problems on their own and to not express vulnerabilities. They may cope with bullying by reacting aggressively to harassment or blame themselves for it, which then prevents any telling. Male victims have been found to be more easily recognized by teachers than girls in elementary school (Haataja et al., 2016), which may compensate the gender difference in telling. Still, efforts should be made to find out why boys tend to decide to remain silent and what can be done to break the silence.

The finding that older students tend to tell adults about victimization less frequently than younger students is alarming. It has been found that teachers have most difficulties identifying victims and bullies in higher grades (Yablon, 2017). This, together with failing to report bullying, poses a double threat to students on higher grades, potentially leaving them without proper help from adults. The association between grade and telling has been interpreted to be due to an age‐related increase in the need for autonomy, leading to older children and adolescents’ willingness to handle the situation on one's own as opposed to turning to adults for help (Unnever & Cornell, 2004). Older students may also rely more on their friends because of their ability to offer more support than the peers of younger students and therefore prefer telling friends to telling adults (Oliver & Candappa, 2007).

In line with our hypothesis, the chronicity of victimization was linked to telling so that students who had experienced victimization for a longer time period were more likely to tell adults about it than students who had been bullied for a shorter period of time. A plausible explanation for the finding is the one offered by Yablon (2017): when students realize that bullying is not going to stop on its own after continuing for a long time, they turn to adults for help. Whether the adult is a teacher, another member of the school staff, or a parent would seem less important, as all these adults can be expected to be able to take appropriate action to stop the bullying either by directly intervening at school or by engaging other adults.

Only a weak association was found between popularity and telling. Although statistically non‐significant, the trend was towards popular students being less likely to tell adults about being bullied. This lends some support to the hypothesis that popular students might not want to risk their status by looking “uncool” in the eyes of peers or that they might be afraid of revenge from the bully. However, weak trends like this should be interpreted with caution – the large sample size obviously contributed to this effect being close to statistical significance. Contrary to our expectations, we did not find any effect of students’ own bullying behavior on telling. It should be noted that there was only little variation in popularity as well as in bullying behavior, as the study sample consisted of repeatedly victimized students: most of them were unpopular and non‐aggressive.

Characteristics of the social context related to telling

The results support the hypotheses concerning the influence of the victim's social context on telling. Students who perceived their homeroom teachers as clearly not tolerating bullying were more likely to tell about victimization than students who perceived their teachers’ attitudes as more unclear or tolerant towards bullying. The relationship may be due to the victim's anticipation of more active actions and support from a teacher with negative attitudes towards bullying. Expectations towards other adults to include the teacher in efforts to stop the bullying may be the reason why teacher attitude is linked not only to telling a teacher, but to telling other adults as well.

As expected, perceived peer support to the victims of bullying (i.e., defender nominations given to classmates) was related to telling adults about victimization. This may be due to victims anticipating more support from peers to stop the bullying instead of them siding with the bully. Peers’ actions may also reflect the overall school climate, just like teacher attitudes may do (both have actually been used as indices of school climate in previous studies examining telling, see Unnever & Cornell, 2004). However, as indicated by the results of this study, perceived support from peers and perceptions of teacher attitudes both have a unique association with students telling about victimization to adults.

Controlling for the effect of whether the student belonged to a school implementing the KiVa antibullying program did not affect the results. This lends support to the interpretation that perceived support from peers and teacher attitudes themselves matter and not just as a part of an antibullying program. It should be noted that all students in our sample had reported at Time 2 (at the end of the school year during which the intervention was implemented) that they had been victimized during the past couple of months. Thus, with a design such as ours we cannot make strong conclusions regarding the main effect of KiVa program on telling. Implementing an intervention which both: (1) encourages telling; and (2) provides school personnel an effective method to intervene and stop bullying, is likely to reduce the number of Time 2 victims in the treatment condition. That is, those students who have told and are in the intervention condition may not be in our sample any more (as they are less likely to be Time 2 victims). Testing the main effect of intervention on telling would require a different design: we controlled for intervention status in order to ensure that it does not confound the associations between our predictors and outcome (telling).

Strengths and limitations of the current study

The current study utilized a longitudinal setting in studying telling about victimization. The two time points included were within one school year, so the social context of the students remained, presumably, fairly unchanged between the measurements. The time between the measurements was also short enough to capture the relationship between predictive factors and telling. When studying phenomena like peer victimization, controlled experimental research designs cannot be implemented because of both ethical and practical reasons. Utilizing a longitudinal design with various predictors simultaneously considered in the model may come quite close to the most controlled design available. However, several methodological improvements, discussed below, should still be made in order to gain a more controlled design.

Another strength of the present study is the large sample of victimized students, including students from several grade levels in many different schools. The large sample enabled more generalizable and reliable results, and the vast variation in the students’ grade levels allowed for proper investigation of grade effects. On the other hand, even relatively weak effects become significant in studies with large samples. Thus, our results should be interpreted with caution and validated by future studies.

We included a comprehensive set of possible predictors simultaneously, examining demographic factors along with individual and contextual variables. In addition, we focused on actual telling behavior which can be very different from the students’ intentions. If the prevalence of students telling about victimization is to be increased, interventions cannot solely rely on information about intentions to tell and thus take the risk that the same findings may not hold for actual telling.

In our model, we did not control for previous telling to adults, which could be seen as a limitation. However, as this question was only asked from those students who, in a given time point, reported that they had been bullied (at least once or twice) during the past couple of months, data on T1 telling were missing for many participants (about 25% of the sample). Also, it was clearly not missing at random, but for a good reason (as they were not victimized at T1, there was nothing to tell). This could have been avoided by asking about intentions to tell (e.g., “If you were bullied, would you tell about that to an adult?”) rather than actual disclosure. However, as pointed out above, intentions may be very different from actual behaviors and we consider it a strength that we focused on the latter.

Besides the traditional way of using peer reports as indices of individual students’ bullying behavior and popularity, we formed a variable reflecting each student's perception of their classmates, namely, the extent to which classmates at large were seen as defending and supporting their victimized peers (see also Saarento et al., 2013). The results gained seem to lend further support to the construct validity of this kind of use of peer reports.

This study introduced a structural equation model of factors related to telling adults about victimization. Two features of the analyses are noteworthy: taking into account the clustering of students into classrooms and the use of a latent variable consisting of telling teachers, other school staff members and parents. Recognizing the clustering of students takes into account that students in the same classroom are likely to be more alike than students in different classrooms, as they share the same social environment. Adjusting the analyses accordingly reduces the effects of possible bias resulting from the clustering.

The use of a latent telling an adult variable has both strengths and limitations. The variable reflects the variation that is common to telling all three kinds of adults. Thus, using it as the outcome variable serves to explain why students tell adults about victimization and, also, to create a simple and comprehensive model. In the current study, the latent variable seemed to reflect the shared variation in the three different telling variables relatively well, and its use was therefore supported. However, the use of such a latent variable may not be justifiable when estimating the effect of, for example, more context‐related variables such as popularity or bully‐victim role. The social status of a student is assigned by peers and may thus only be associated with the behavior of the student in the school context and not at home, although students may acknowledge that information about bullying is likely to travel between adults in different contexts. Likewise, bully‐victims might behave differently at school and at home. The final model explained only 12% of the variance in telling adults, which may reflect the differences between all three types of adults in relation to context and, supposedly, distance from the student. Looking at the correlations between predictors and telling different adults, especially telling other adults at school seems to be associated with different things than telling adults at home and telling teachers. On the other hand, coefficients of determination are usually low in behavioral sciences such as psychology.

The fact that the final model only predicted a relatively low percentage of the variance in telling adults about victimization can also result from the research design and some possible confounding factors. For example, previous incidents of telling about victimization were not controlled for in the current study. Thus, it is possible that some of the participants had told someone about victimization prior to the current study, as many participants reported being victimized for a longer period of time than the last 2 months assessed in the questions (59.8% of the victims reported having been bullied for 6 months or more). Because this study only included victimized students, it can be assumed that having told about victimization prior to the study had not resulted in termination of victimization, although it may have had some effect on its intensity or frequency. Based on existing research (Boulton et al., 2013), previous experiences of the effectiveness of telling about victimization (i.e., receiving social support) are likely to have an effect on future telling intentions and, perhaps, also on actual telling behavior.

Another possible explanation for the model's relatively low ability to predict telling adults about victimization is that the current study did not look into predictors related to the family context. Factors such as perceived parental attitudes towards bullying, or parenting style might add to the predictive value of the model. The association between family‐related factors and telling about victimization remains a subject for future studies.

Practical and research implications

There is a crucial need to pay more attention to victimized students who do not disclose to anyone. For instance, adolescent students, boys, and students in contexts where peers do not stand up for the victimized or where bullying behavior is not clearly condemned by adults, are at risk of being unnoticed and therefore not helped. To promote telling, efforts should be made to increase supportive behavior for the victimized student among peers, and school personnel should communicate a clear stand for not tolerating bullying.

Previous studies, as well as the current one, have studied correlates of telling and intentions to tell, but the aspects of telling remain largely unknown. In what kind of situations do victimized students tell about victimization? Are these conversations initiated by the students themselves or by the other person, and do students initiate conversations with adults by telling about victimization in mind or does the subject merely pop up in the middle of some other discussion? What motivates students to tell? What do students actually tell when they talk about victimization? Assessing these kinds of aspects of the telling situation could help to increase the predictability of telling. Furthermore, the current study did not look into the associations between different forms of victimization (e.g., cyber‐victimization, relational or physical victimization) and telling; two previous studies (Unnever & Cornell, 2004; Yablon, 2010) suggest that victims faced with physical bullying are less likely to disclose.

Research on the predictors of telling should be conducted in different cultural and social environments to increase the generalizability of the findings. To avoid recall bias regarding telling about victimization and to collect more detailed information about different aspects of telling, real‐time teacher reports, written immediately after receiving information about incidents of victimization and collected over a long period of time, could be utilized. School personnel might be a more reliable and reachable source of systematic reports than adults at home. This method would also enhance the practical applicability of research about telling behavior. Registering detailed information (e.g., who were present at the time of telling, who initiated the conversation, and the aspects of victimization reported by the victim: who, how, when, etc.) about the situation in which telling takes place would serve to create more controlled research designs. There is also need for further research on the outcomes of telling, as the evidence for disclosure actually leading to adult intervention and to bullying decreasing or stopping is scarce.

The next step in this field of study is theory formulation. Previous research suggests effects of, for example, teacher characteristics and student‐teacher relationship on telling about victimization (Aceves et al., 2010; Yablon, 2017). More focused studies aiming to form theoretical models of such effects (factors related to the school and class as a social environment, e.g., relationships to peers and teachers, class norms, and attitudes, and their interaction with student characteristics) would serve the development of improved interventions.

Blomqvist, K. , Saarento‐Zaprudin, S. & Salmivalli, C. (2020). Telling adults about one's plight as a victim of bullying: Student‐ and context‐related factors predicting disclosure. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 61, 151–159.

References

- Aceves, M. J. , Hinshaw, S. P. , Mendoza‐Denton, R. & Page‐Gould, E. (2010). Seek help from teachers or fight back? Student perceptions of teachers’ actions during conflicts and responses to peer victimization. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 658–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulton, M. J. , Murphy, D. , Lloyd, J. , Besling, S. , Coote, J. , Lewis, J. , et al (2013). Helping counts: Predicting children's intentions to disclose being bullied to teachers from prior social support experiences. British Educational Research Journal, 39, 209–221. [Google Scholar]

- Boulton, M. J. & Underwood, K. (1992). Bully victim problems among middle school children. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 62, 73–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, L. , Smith, P. K. & Binney, V. (1994). Perceived family relationships of bullies, victims and bully/victims in middle school. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 11, 215–232. [Google Scholar]

- Cortes, K. I. & Kochenderfer‐Ladd, B. (2014). To tell or not to tell: What influences children's decisions to report bullying to their teachers? School Psychology Quarterly, 29, 336–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLara, E. W. (2012). Why adolescents don't disclose incidents of bullying and harassment. Journal of School Violence, 11, 288–305. [Google Scholar]

- Fekkes, M. F. , Pijpers, I. M. & Verloove‐Vanhorick, S. P. (2005). Bullying: Who does what, when and where? Involvement of children, teachers and parents in bullying behavior. Health Education Research, 20, 81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haataja, A. , Sainio, M. , Turtonen, M. & Salmivalli, C. (2016). Implementing the KiVa antibullying program: Recognition of stable victims. Educational Psychology, 36, 595–611. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, S. C. , Boyle, J. M. E. & Warden, D. (2004). Help seeking amongst child and adolescent victims of peer‐aggression and bullying: The influence of school‐stage, gender, victimization, appraisal, and emotion. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 74, 375–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kärnä, A. , Voeten, M. , Little, T. D. , Alanen, E. , Poskiparta, E. & Salmivalli, C. (2013). Effectiveness of the KiVa Antibullying Program: Grades 1–3 and 7–9. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105, 535–551. [Google Scholar]

- Kärnä, A. , Voeten, M. , Little, T. D. , Poskiparta, E. , Kaljonen, A. & Salmivalli, C. (2011). A large‐scale evaluation of the KiVa antibullying program: Grades 4–6. Child Development, 82, 311–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochenderfer‐Ladd, B. & Pelletier, M. E. (2008). Teachers’ views and beliefs about bullying: Influences on classroom management strategies and students’ coping with peer victimization. Journal of School Psychology, 46, 431–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L. K. & Muthén, B. (1998–2012) Mplus User's Guide (7th edn). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, R. S. & Murray, B. J. (2005). How students and teachers view the seriousness of peer harassment: When is it appropriate to seek help? Journal of Educational Psychology, 97, 347–365. [Google Scholar]

- Novick, R. M. & Isaacs, J. (2010). Telling is compelling: The impact of student reports of bullying on teacher intervention. Educational Psychology, 30, 283–296. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, C. & Candappa, M. (2007). Bullying and the politics of ‘telling’. Oxford Review of Education, 33, 71–86. [Google Scholar]

- Olweus, D. (1996) The Revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire. Bergen, Norway: University of Bergen, Research Center for Health Promotion (HEMIL Center). [Google Scholar]

- Saarento, S. , Boulton, A. J. & Salmivalli, C. (2015). Reducing bullying and victimization: Student‐ and classroom‐level mechanisms of change. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43, 61–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saarento, S. , Kärnä, A. , Hodges, E. V. E. & Salmivalli, C. (2013). Student‐, classroom‐, and school‐level risk factors for victimization. Journal of School Psychology, 51, 421–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainio, M. , Veenstra, R. , Huitsing, G. & Salmivalli, C. (2012). Same‐ and other‐sex victimization: Are the risk factors similar? Aggressive Behavior, 38, 442–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmivalli, C. (2010). Bullying and the peer group: A review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 15, 112–120. [Google Scholar]

- Salmivalli, C. , Lagerspetz, K. , Björkqvist, K. , Österman, K. & Kaukiainen, A. (1996). Bullying as a group process: Participant roles and their relations to social status within the group. Aggressive Behavior, 22, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Salmivalli, C. , Sainio, M. & Hodges, E. V. E. (2013). Electronic victimization: Correlates, antecedents, and consequences among elementary and middle school students. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 42, 442–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmivalli, C. & Voeten, M. (2004). Connections between attitudes, group norms, and behaviour in bullying situations. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 28, 246–258. [Google Scholar]

- Salmivalli, C. , Voeten, M. & Poskiparta, E. (2011). Bystanders matter: Associations between defending, reinforcing, and the frequency of bullying in classrooms. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 40, 668‐676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seebaß, G. , Schmitz, M. & Gollwitzer, P. M. (Eds.). (2013) Acting intentionally and its limits: Individuals, groups, institutions: Interdisciplinary approaches. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Sentse, M. , Kretschmer, T. & Salmivalli, C. (2015). The longitudinal interplay between bullying, victimization, and social status: Age‐related and gender differences. Social Development, 24, 659–677. [Google Scholar]

- Sijtsema, J. J. , Veenstra, R. , Lindenberg, S. & Salmivalli, C. (2009). Empirical test of bullies’ status goals: Assessing direct goals, aggression, and prestige. Aggressive Behavior, 35, 57–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P. K. (2014). Understanding school bullying. It's nature and prevention strategies. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P. K. & Shu, S. (2000). What good schools can do about bullying: Findings from a decade of research and action. Childhood, 7, 193–212. [Google Scholar]

- Solberg, M. E. & Olweus, D. (2003). Prevalence estimation of school bullying with the Olweus Bully ⁄ Victim questionnaire. Aggressive Behavior, 29, 239–268. [Google Scholar]

- Unnever, J. D. & Cornell, D. G. (2004). Middle school victims of bullying: Who reports being bullied? Aggressive Behavior, 30, 373–388. [Google Scholar]

- Veenstra, R. , Lindenberg, S. , Oldehinkel, A. J. , De Winter, A. F. , Verhulst, F. C. & Ormel, J. (2005). Bullying and victimization in elementary schools: A comparison of bullies, victims, bully/victims, and noninvolved preadolescents. Developmental Psychology, 41, 672–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yablon, Y. B. (2010). Student–teacher relationships and students’ willingness to seek help for school violence. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27, 1110–1123. [Google Scholar]

- Yablon, Y. B. (2017). Students’ reports of severe violence in school as a tool for early detection and prevention. Child Development, 88, 55–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, A. & Salmivalli, C. (2013). Different forms of bullying and victimization: Bully‐victims versus bullies and victims. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 10, 723–738. [Google Scholar]