Abstract

Objective

Study 311 (NCT02849626) was a global, multicenter, open‐label, single‐arm study that assessed safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics of once‐daily adjunctive perampanel oral suspension in pediatric patients (aged 4 to <12 years) with focal seizures (FS) (with/without focal to bilateral tonic‐clonic seizures [FBTCS]) or generalized tonic‐clonic seizures (GTCS).

Methods

In the 311 Core Study, a 4‐week Pre‐treatment Period (Screening/Baseline) preceded a 23‐week Treatment Period (11‐week Titration; 12‐week Maintenance) and 4‐week Follow‐up. Endpoints included safety/tolerability (primary endpoint), median percent change in seizure frequency per 28 days from Baseline (Treatment Period), and 50% responder and seizure‐freedom rates (Maintenance Period). Patients were stratified by age (4 to <7; 7 to <12 years) and concomitant enzyme‐inducing anti‐seizure drug (EIASD) use.

Results

One hundred eighty patients were enrolled (FS, n = 149; FBTCS, n = 54; GTCS, n = 31). The Core Study was completed by 146 patients (81%); the most common primary reason for discontinuation was adverse event (AE) (n = 14 [8%]). Mean (standard deviation) daily perampanel dose was 7.0 (2.6) mg/day and median (interquartile range) duration of exposure was 22.9 (2.0) weeks. The overall incidence of treatment‐emergent AEs (TEAEs; 89%) was similar between patients with FS (with/without FBTCS) and GTCS. The most common TEAEs were somnolence (26%) and nasopharyngitis (19%). There were no clinically important changes observed for cognitive function, laboratory, or electrocardiogram (ECG) parameters or vital signs. Median percent reductions in seizure frequency per 28 days from Baseline were as follows: 40% (FS), 59% (FBTCS), and 69% (GTCS). Corresponding 50% responder and seizure‐freedom rates were as follows: FS, 47% and 12%; FBTCS, 65% and 19%; and GTCS, 64% and 55%, respectively. Improvements in response/seizure frequency from Baseline were seen regardless of age or concomitant EIASD use.

Significance

Results from the 311 Core Study suggest that daily oral doses of adjunctive perampanel are generally safe, well tolerated, and efficacious in children age 4 to <12 years with FS (with/without FBTCS) or GTCS.

Keywords: anti‐seizure drug, enzyme‐inducing anti‐seizure drug, epilepsy, focal to bilateral tonic‐clonic seizures, seizure freedom

Key Points.

Perampanel is a noncompetitive, selective α‐amino‐3‐hydroxy‐5‐methyl‐4‐isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor antagonist indicated in patients with focal seizures (FS) or generalized tonic‐clonic seizures (GTCS).

Pharmacokinetic data suggest that the same perampanel dose (mg/day) can be given to adults and children (age ≥4 years) to achieve exposures shown to be efficacious.

Study 311 was a global, multicenter, open‐label, single‐arm study of adjunctive perampanel treatment in pediatric patients (aged 4 to <12 years) with FS or GTCS.

Perampanel oral suspension was generally safe and well tolerated in pediatric patients; somnolence was the most common treatment‐emergent adverse event.

The median reductions in seizure frequency per 28 days from baseline and 50% or 100% responder rates were similar regardless of seizure type, age, or EIASD status.

1. INTRODUCTION

Perampanel, an orally active, noncompetitive, selective α‐amino‐3‐hydroxy‐5‐methyl‐4‐isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor antagonist,1 is the first selective inhibitor of postsynaptic excitatory neurotransmission2 and is approved in >50 countries worldwide. Perampanel at oral doses of 4‐12 mg/day has shown efficacy when administered as an adjunctive therapy in focal seizures (FS; previously known as partial‐onset seizures) with or without focal to bilateral tonic‐clonic seizures (FBTCS; previously known as secondarily generalized seizures).3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Perampanel has also demonstrated efficacy as an adjunctive therapy for generalized tonic‐clonic seizures (GTCS; previously known as primary generalized tonic‐clonic seizures).3, 4, 8 Recently, in the United States, the indication for perampanel was expanded from adolescent (age ≥12 years) and adult patients to include pediatric patients (≥4 years) with FS with or without FBTCS.4

The efficacy, safety, and tolerability profiles of adjunctive perampanel in patients aged ≥12 years with FS (with/without FBTCS) have been well documented in three double‐blind, randomized, placebo‐controlled, phase III studies (Studies 304 [NCT00699972], 305 [NCT00699582], and 306 [NCT00700310]),5, 6, 7 and an accompanying pooled analysis.9 Long‐term (≤3 years) tolerability and improvements in seizure outcomes for patients with FS (with/without FBTCS) have also been observed with adjunctive perampanel.10 For GTCS, the efficacy and safety of adjunctive perampanel has been demonstrated in a double‐blind, randomized, placebo‐controlled, phase III study (Study 332 [NCT01393743]), which involved patients (aged ≥12 years) with drug‐resistant GTCS associated with idiopathic generalized epilepsy.8

Selection of a suitable anti‐seizure drug (ASD) for patients with epilepsy aged ≥4 years continues to be a challenge for physicians because of the low number of interventional (efficacy/safety) clinical studies conducted in such young patients11 due to factors such as paucity of funding, or ethical concerns.12 Extrapolation of efficacy data from adult to pediatric patients (an approach accepted by the United States Food and Drug Administration [FDA13] when it can be reasonably assumed children have similar disease progression, response to treatment, and exposure‐response relationships to adults) can be a valuable means of increasing treatment options for children with epilepsy.14, 15 However, safety data cannot be extrapolated from adults to children; therefore, separate (open‐label) clinical studies are required to assess drug safety in patients aged ≥4 years.13

The pharmacokinetic (PK) profiles of perampanel (tablet form) in adolescents (aged ≥12 to <18 years) and adult patients are comparable.4, 16 However, the presence of a moderate or strong CYP3A4 inducer such as an enzyme‐inducing ASD (EIASD; eg, carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, and phenytoin) can decrease plasma levels of perampanel.4, 17

Results from an open‐label pilot study (with long‐term extension; Study 232 [NCT01527006]) of once‐daily adjunctive perampanel oral suspension in patients with epilepsy aged ≥2 to <12 years18 showed that perampanel PK is independent of age, weight, or liver function. This suggests that the same perampanel dose (mg/day) can be given to adults and children (≥2 years of age) without the need for age or weight‐based adjustments to achieve exposures shown to be efficacious.18

Study 311 was an open‐label study designed to evaluate the safety, tolerability, PK, and PK/pharmacodynamics of adjunctive perampanel oral suspension in children (aged 4 to <12 years) with inadequately controlled FS (with/without FBTCS) or GTCS. This article presents safety and efficacy results from the final 311 Core Study and aims to provide evidence to support the efficacy extrapolation approach for perampanel as a treatment option for pediatric patients.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Patients and study design

Study 311 (NCT02849626) was a global, multicenter, open‐label, single‐arm study involving children (4 to <12 years of age) with inadequately controlled FS (with/without FBTCS) or GTCS. It included a Core Study plus Extension A and Extension B.

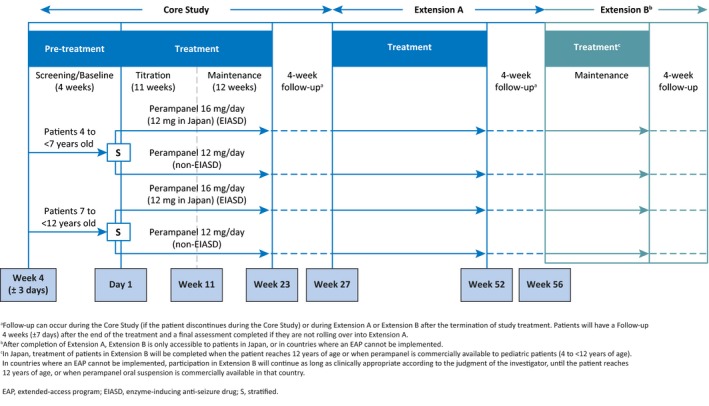

The 311 Core Study consisted of a 4‐week Pre‐treatment Period (Screening/Baseline), a 23‐week Treatment Period (11‐week Titration plus 12‐week Maintenance), and a 4‐week Follow‐up Period for patients not entering Extension A (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study design

During the Pre‐treatment (Screening/Baseline) Period of the Core Study, patients continued their existing baseline ASD(s) as per the inclusion/exclusion criteria. During this period, patients were stratified by age (4 to <7 years; 7 to <12 years) and by the presence or absence of a concomitant EIASD.

During the Treatment Phase, perampanel oral suspension (0.5 mg/mL) was administered once daily at bedtime. During the Titration Period, the perampanel starting dose, titration schedule, and maximum allowed dose were based on whether a patient was/was not receiving a concomitant EIASD, as well as the individual patient's clinical response and tolerability to treatment. Titration (increments of 2 mg/day) occurred no more frequently than weekly from a starting dose of 2 mg/day up to 8 mg/day for patients not receiving concomitant EIASDs or from a starting dose of 2 or 4 mg/day up to 12 mg/day for patients taking concomitant EIASDs. However, patients who were tolerating perampanel well, and were deemed to benefit from a higher dose, could have further dose titrations up to 12 mg/day for patients not receiving concomitant EIASDs or up to 16 mg/day for patients taking concomitant EIASDs. Regardless of EIASD status, the maximum dose of perampanel that patients enrolled in Japan could receive was 12 mg/day.

During the Maintenance Period of the Treatment Phase, patients continued perampanel at the dose level achieved at the end of the Titration Period. Dose adjustments were permitted if a patient experienced intolerable treatment‐emergent adverse event(s) (TEAE[s]) or a higher dose was deemed clinically beneficial. During the Titration and Maintenance Periods of the Core Study, all dose adjustments were implemented via one dose level up or down. Patients who could not tolerate at least 2 mg/day perampanel were discontinued. No change of concomitant ASD was allowed during the Titration or Maintenance Periods of the Core Study.

Patients who completed all scheduled visits up to and including Visit 9 (Week 23) in the Treatment Period of the Core Study were eligible to participate in Extension A. Patients who did not roll over into Extension A, or who discontinued from the Core Study, completed a Follow‐up Period of 4 weeks (±7 days) after the last perampanel dose. Extension A consisted of a Maintenance Period (29 weeks) and Follow‐up Period (4 weeks [±7 days]). After completion of Extension A, patients enrolled in Japan and countries where an Extended Access Program cannot be implemented could enter Extension B.

Study 311 was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH)‐E6 Guideline for Good Clinical Practice (GCP) CPMP/ICH/135/95, the United States Code of Federal Regulations Title 21, the European GCP Directive 2005/28/EC, and the Clinical Trial Directive 2001/20/EC.

2.2. Key eligibility criteria

Eligibility criteria are provided in Text S1. In summary, patients must have had a diagnosis of epilepsy with FS (with/without FBTCS) or GTCS according to the 1981 International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) seizure classification19 (terminology has been updated in accordance with 2017 ILAE seizure classification)20 established at least 6 months prior to screening (Visit 1) by clinical history and an electroencephalogram consistent with the diagnosis. It was required that a pre‐screening brain imaging scan ruled out a progressive cause of epilepsy. Patients must also have had ≥1 FS (simple FS with motor signs, complex FS, or complex FS with FBTC seizures) or ≥1 GTCS during the 12 weeks ± 3 days (4 weeks ± 3 days in Japan only) before study treatment initiation (Visit 2; Week 0)–the seizure could therefore have occurred ≤8 weeks prior to Visit 1 and/or ≤4 weeks prior to Visit 2; the requirement in Japan was 4 weeks ± 3 days.

Patients must have been receiving treatment with 1‐3 ASDs at stable doses for ≥4 weeks prior to Visit 1, or for a new ASD regimen, stable for ≥8 weeks prior to Visit 1. Only one EIASD (carbamazepine, phenytoin, oxcarbazepine, or eslicarbazepine) was permitted.

2.3. Endpoints

The primary endpoint was safety and tolerability of perampanel oral suspension. Safety assessments included the incidence of TEAEs, serious TEAEs (TESAEs), laboratory parameters, vital signs, and electrocardiogram (ECG) parameters.

To evaluate effects of perampanel on cognitive function, secondary safety endpoints included changes from baseline in Aldenkamp‐Baker Neuropsychological Assessment Schedule (ABNAS) at the end of the Treatment Phase (Week 23). ABNAS21 measures the following aspects of cognitive function: fatigue, slowing, memory, concentration, motor coordination, and language, using a 4‐point scale; scores range from 0 – 72, with higher scores indicating worsening cognitive function.

Key secondary endpoints to assess efficacy included median percent change in seizure frequency per 28 days during the Treatment Period (Titration and Maintenance Periods), and the proportion of patients who were 50% responders, or achieved seizure freedom (100% responders) during the Maintenance Period. Clinical Global Impression of Change (CGIC) measured improvement in a patient's condition following perampanel treatment at Week 23 compared with Baseline. A full list of secondary and exploratory endpoints are provided in Table S1.

2.4. Patient cohorts

Data are presented for all (total) patients and by disease cohort (FS; FBTCS; GTCS), age cohort (younger [4 to <7 years] vs older patients [7 to <12 years]), and with/without concomitant EIASDs. Patients were enrolled into the FS or GTCS disease cohorts (or FBTCS sub‐cohort) by the investigator based on epilepsy history. Patients who experienced ≥1 seizure type during Baseline were included in the efficacy analysis for each seizure type. Efficacy data for patients with FS are presented as total FS: all FS including simple FS seizures without motor signs, simple FS with motor signs, complex FS, and complex FS with FBTCS. If a patient did not experience a FS, FBTCS, or GTCS during Baseline, they were excluded from the efficacy analysis for that seizure type but were included as part of the total seizure group analysis for the cohort into which they were assigned.

2.5. Statistical analyses

The Safety Analysis Set (SAS) included all patients who received ≥1 dose of perampanel and had ≥1 post‐dose safety assessment. The Full Analysis Set (FAS) included all patients who received ≥1 perampanel dose and had ≥1 post‐dose primary efficacy measurement. Statistical analyses were completed using statistical software SAS version 9.3. Responder rate data (Maintenance Period) are presented using last observation carried forward (LOCF). Cognition data, demographic, and other Baseline characteristics for the SAS, and percent change in seizure frequency per 28 days from Baseline were summarized using descriptive statistics. The proportion of responders, the proportion of patients who achieved seizure freedom (100% responders), and CGIC (LOCF) values were summarized using frequency count (n,%).

A sample size of ≥160 patients was considered sufficient for safety evaluation in this patient population, and is consistent with the total number of adolescents enrolled in the global phase III efficacy and safety studies, which supported perampanel's indication in FS and GTCS.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Patients

Patient demographics and Baseline clinical characteristics for all (total) patients and by cohort are provided in Table 1. A total of 180 pediatric patients were enrolled (Figure 2); 149 patients (83%) had FS, of which a subset of 54 patients (30%) had FBTCS, and 31 patients (17%) had GTCS. Forty‐six patients (26%) patients were age 4 to <7 years and 134 patients (74%) were age 7 to <12 years. The mean (SD) patient age for all (total) patients was 8.1 (2.1) years. Forty‐nine patients (27%) were taking a concomitant EIASD at Baseline, although one patient taking carbamazepine at Baseline was erroneously included in the “without EIASD” cohort (Table 1). Most commonly taken ASDs at Baseline were levetiracetam (n = 58, 32%) and valproic acid (n = 54, 30%); the most common EIASDs were carbamazepine (n = 26, 14%) and oxcarbazepine (n = 19, 11%).

Table 1.

Demographic and Baseline clinical characteristics of patients participating in the Core Study by disease, age, and EIASD cohort (Safety Analysis Set)

| Disease cohort | Age cohort | EIASD cohort | All (total) patients (N = 180) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FS (N = 149) | FBTCS (N = 54) | GTCS (N = 31) | 4 to <7 years (N = 46) | 7 to <12 years (N = 134) | With EIASDs (N = 48) | Without EIASDs (N = 132)a | ||

| Mean age,b years (SD) | 8.1 (2.1) | 7.7 (2.0) | 8.5 (2.0) | 5.3 (0.7) | 9.1 (1.4) | 8.4 (2.1) | 8.1 (2.1) | 8.1 (2.1) |

| Sex, % | ||||||||

| Female | 52 | 54 | 36 | 52 | 48 | 54 | 47 | 49 |

| Race, n (%) | ||||||||

| Caucasian | 70 (48) | 19 (35) | 23 (89) | 21 (50) | 72 (56) | 30 (64) | 63 (51) | 93 (54) |

| Japanese | 65 (45) | 33 (61) | 0 (0) | 16 (38) | 49 (38) | 13 (28) | 52 (42) | 65 (38) |

| Otherc | 10 (7) | 2 (4) | 3 (12) | 5 (12) | 8 (6) | 4 (9) | 9 (7) | 13 (8) |

| Missing data | 4 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 8 | 9 |

| Mean (SD) time since diagnosis,d years | 5.7 (2.7) | 5.7 (2.5) | 5.6 (3.6) | 4.2 (1.5) | 6.2 (3.1) | 5.5 (2.8) | 5.8 (2.9) | 5.7 (2.9) |

| Seizure type,e n (%) | ||||||||

| FS | 148 (99) | 54 (100) | 7 (23) | 41 (89) | 114 (85) | 46 (96) | 109 (83) | 155 (86) |

| Simple FS without motor signs | 19 (13) | 6 (11) | 5 (16) | 5 (11) | 19 (14) | 6 (13) | 18 (14) | 24 (13) |

| Simple FS with motor signs | 46 (31) | 16 (30) | 5 (16) | 9 (20) | 42 (31) | 10 (21) | 41 (31) | 51 (28) |

| Complex FS | 116 (78) | 35 (65) | 4 (13) | 30 (65) | 90 (67) | 38 (79) | 82 (62) | 120 (67) |

| Complex FS with FBTCS | 82 (55) | 54 (100) | 2 (7) | 23 (50) | 61 (46) | 21 (44) | 63 (48) | 84 (47) |

| Generalized seizures | 24 (16) | 9 (17) | 31 (100) | 11 (24) | 44 (33) | 11 (23) | 44 (33) | 55 (31) |

| Absence/myoclonic | 9 (6)/ 12 (8) | 2 (4)/ 3 (6) | 16 (52)/ 17 (55) | 5 (11)/ 6 (13) | 20 (15)/ 23 (17) | 2 (4)/ 4 (8) | 23 (17)/ 25 (19) | 25 (14)/ 29 (16) |

| Clonic/tonic | 6 (4)/ 5 (3) | 3 (6)/ 4 (7) | 10 (32)/ 11 (36) | 4 (9)/ 3 (7) | 12 (9)/ 13 (10) | 2 (4)/ 3 (6) | 14 (11)/ 13 (10) | 16 (9)/ 16 (9) |

| Tonic‐clonic | 4 (3) | 2 (4) | 27 (87) | 6 (13) | 25 (19) | 2 (4) | 29 (22) | 31 (17) |

| Atonic (astatic) | 9 (6) | 4 (7) | 6 (19) | 3 (7) | 12 (9) | 4 (8) | 11 (8) | 15 (8) |

| Number of ASDs at Baseline, n (%) | ||||||||

| EIASDf | ||||||||

| 1 | 13 (28) | 4 (33) | 2 (100) | 1 (9) | 14 (37) | 15 (31) | NA | 15 (31) |

| 2 | 27 (57) | 7 (58) | 0 (0) | 7 (64) | 20 (53) | 26 (54) | NA | 27 (55) |

| 3 | 7 (15) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 3 (27) | 4 (11) | 7 (15) | NA | 7 (14) |

| Non‐EIASDsf | ||||||||

| 1 | 14 (14) | 7 (17) | 6 (21) | 4 (11) | 16 (17) | NA | 20 (15) | 20 (15) |

| 2 | 56 (55) | 22 (52) | 17 (59) | 22 (63) | 51 (53) | NA | 73 (56) | 73 (56) |

| 3 | 32 (31) | 13 (31) | 6 (21) | 9 (26) | 29 (30) | NA | 38 (29) | 38 (29) |

Disease cohorts: Patients were assigned as FS or GTCS by the investigator; FBTCS is the subset of FS patients who recorded focal to bilateral tonic‐clonic seizures during the Baseline period. Percentage values may be >100% due to rounding.

Abbreviations: EIASD, enzyme‐inducing anti‐seizure drug; FBTCS, focal to bilateral tonic‐clonic seizures; FS, focal seizures; GTCS, generalized tonic‐clonic seizures; SD, standard deviation.

One patient who was taking carbamazepine for epilepsy at Baseline was erroneously included in the without EIASD cohort.

Age is calculated at date of informed consent/assent.

Not Caucasian and not Japanese race; includes Black or African American, Asian (non‐Japanese), American Indian or Alaska Native, Other.

(Screening date – date of diagnosis)/365.25. If the day or month of diagnosis was missing, the day was imputed as the first of the month, and the month was imputed as January. If imputed date is before the birth date, the birth date was used in place of time from diagnosis.

Multiple seizure types may be recorded.

An EIASD patient took one inducing ASD at Baseline; EIASDs include carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, eslicarbazepine, and phenytoin; all other ASDs are non‐EIASDs.

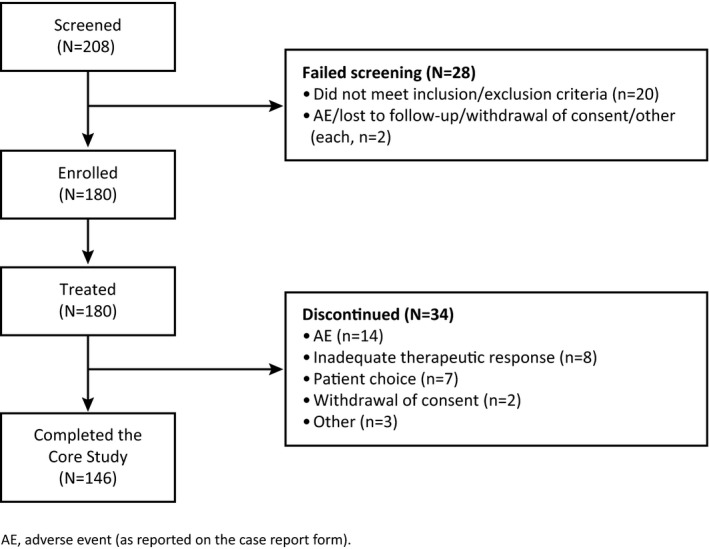

Figure 2.

Patient disposition and primary reason for discontinuation from the 311 Core Study (all enrolled patients)

All enrolled patients were included in the SAS and had ≥1 post‐dose primary efficacy measurement so were also included in the FAS. The total seizures (FS) group includes one patient with FS who was excluded from the FS efficacy analysis because they did not have a FS at Baseline, and the total seizures (GTCS) group includes nine patients excluded from the GTCS efficacy analysis because they did not have a GTCS seizure at Baseline. All patients in the FBTCS cohort had experienced an FBTCS at Baseline.

Overall, 146 patients (81%) completed the Core Study. The most common reasons for discontinuation were the following: adverse event (AE; 8%), inadequate therapeutic effect (4%), and patient choice (4%). Similar trends for study completion and reason for discontinuation were seen in the disease, age, and EIASD cohorts.

3.2. Perampanel dose and exposure

The mean (standard deviation, SD) daily dose of perampanel for all (total) patients was 7.0 (2.6) mg/day; this was similar across the disease and age cohorts, but slightly higher in the “with” (8.7 [2.9] mg/day) vs the “without” (6.4 [2.3] mg/day) EIASD cohorts (Table S2). The median (interquartile range [IQR]) duration of exposure for all (total) patients was 22.9 (2.0) weeks; again, this was similar across the cohorts (Table S2). The majority of patients (80%) received perampanel for >20 weeks, with 69% receiving perampanel for >22 weeks.

3.3. Safety outcomes

Overall, 89% of patients experienced a TEAE and 67% experienced a TEAE considered related to perampanel (Table 2). Patients in the GTCS cohort and younger pediatric patients had a higher proportion of treatment‐related TEAEs (81% and 83%, respectively) compared with any other cohort (60%‐69%, Table 2). The most common TEAEs (≥10% of patients, regardless of causality) observed in all (total) patients were somnolence (26%), nasopharyngitis (19%); dizziness, irritability, and pyrexia (each 13%); and vomiting (11%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Overview of TEAEs, and TEAEs occurring in ≥10% of patients, by disease cohort, age cohort, and EIASD cohort (Safety Analysis Set)

| Disease cohort | Age cohort | EIASD cohort | All (total) patients (N = 180) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FS (N = 149) | FBTCS (N = 54) | GTCS (N = 31) | 4 to <7 years (N = 46) | 7 to <12 years (N = 134) | With EIASDs (N = 48) | Without EIASDs (N = 132) | ||

| TEAEs,a n (%) | 134 (90) | 53 (98) | 26 (84) | 45 (98) | 115 (86) | 40 (83) | 120 (91) | 160 (89) |

| Treatment‐related TEAEs, n (%) | 95 (64) | 36 (67) | 25 (81) | 38 (83) | 82 (61) | 29 (60) | 91 (69) | 120 (67) |

| Severeb TEAEs, n (%) | 10 (7) | 4 (7) | 4 (13) | 6 (13) | 8 (6) | 2 (4) | 12 (9) | 14 (8) |

| Serious TEAEs, n (%) | 23 (15) | 13 (24) | 4 (13) | 13 (28) | 14 (10) | 5 (10) | 22 (17) | 27 (15) |

| Deathsc | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Other SAEs, n (%) | 22 (15) | 13 (24) | 4 (13) | 12 (26) | 14 (10) | 4 (8) | 22 (17) | 26 (14) |

| Life‐threatening | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Requiring hospitalization/prolongation of hospitalization | 21 (14) | 13 (24) | 4 (13) | 12 (26) | 13 (10) | 4 (8) | 21 (16) | 25 (14) |

| Persistent/significant disability or incapacityc | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Important medical eventsc | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0 | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| TEAEs leading to study drug dose adjustment, n (%) | 69 (46) | 24 (44) | 15 (48) | 27 (59) | 57 (43) | 17 (35) | 67 (51) | 84 (47) |

| Withdrawal | 14 (9) | 2 (4) | 3 (10) | 5 (11) | 12 (9) | 5 (10) | 12 (9) | 17 (9) |

| Dose increase | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Dose reduction | 60 (40) | 22 (41) | 13 (42) | 24 (52) | 49 (37) | 15 (31) | 58 (44) | 73 (41) |

| Dose interruption | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| TEAE related to psychosis/psychotic disorders,d n (%) | ||||||||

| Bradyphrenia | 5 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (4) | 3 (6) | 2 (2) | 5 (3) |

| Abnormal behavior | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Affect lability | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Most common TEAEs (occurring in ≥10%, each cohort), n (%) | ||||||||

| Somnolence | 42 (28) | 17 (32) | 5 (16) | 16 (35) | 31 (23) | 12 (25) | 35 (27) | 47 (26) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 32 (22) | 16 (30) | 3 (10) | 12 (26) | 23 (17) | 11 (23) | 24 (18) | 35 (19) |

| Dizziness | 18 (12) | 7 (13) | 5 (16) | 6 (13) | 17 (13) | 5 (10) | 18 (14) | 23 (13) |

| Irritability | 18 (12) | 8 (15) | 5 (16) | 9 (20) | 14 (10) | 3 (6) | 20 (15) | 23 (13) |

| Pyrexia | 20 (13) | 7 (13) | 3 (10) | 11 (24) | 12 (9) | 8 (17) | 15 (11) | 23 (13) |

| Vomiting | 16 (11) | 7 (13) | 4 (13) | 5 (11) | 15 (11) | 9 (19) | 11 (8) | 20 (11) |

Disease cohorts: Patients were assigned as FS or GTCS by the investigator; FBTCS is the subset of FS patients who recorded focal to bilateral tonic‐clonic seizures during the Baseline period. Percentage values may be >100% due to rounding.

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; EIASD, enzyme‐inducing anti‐seizure drug; FBTCS, focal to bilateral tonic‐clonic seizures; FS, focal seizures; GTCS, generalized tonic‐clonic seizures; MedDRA, Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities; SAE, serious adverse event; SMQ, standardized MedDRA queries; TEAE, treatment‐emergent adverse event.

A TEAE is defined as an AE that emerges from the date of first dose of study drug to 28 days after last end date of dose in prescribed dose entry, having been absent at Pre‐treatment (Baseline) or re‐emerges during treatment, having been present at Pre‐treatment (Baseline) but stopped before treatment, or worsens in severity during treatment relative to the Pre‐treatment state when the AE is continuous; a patient with two or more AEs is counted only once for that event.

Severe = incapacitating, with inability to work or to perform normal daily activity.

This event was considered unrelated to study drug (perampanel) treatment.

Defined by narrow and broad MedDRA SMQ terms.

The withdrawal rate due to TEAEs was generally similar across all cohorts (4%‐11%). Perampanel dose reductions due to a TEAE were reported in 31%‐52% of patients across all cohorts, and were highest in patients 4 to <7 years of age.

Twenty‐seven patients (15%) experienced 47 TESAEs, of whom 25 (14%) required hospitalization or prolongation of hospitalization during the study. Of these, seven patients (4 from the younger and 3 from the older pediatric cohort) had 10 TESAEs considered related to perampanel (Table S3). One death was reported (viral myocarditis) in a patient taking 8 mg perampanel (FS; aged 4 years; with EIASD); the event was deemed to be not related to perampanel. Further information on those patients who discontinued due to a TEAE/s, or who had a dose reduction due to a TEAE/s, can be found in Text S2.

There were no clinically significant changes at Week 23 from Baseline in cognitive function as assessed by ABNAS in total score and in each of the domains. Mean (SD) change from Baseline in total ABNAS score across all cohorts at Week 23 was 1.3 (15.2) (LOCF). No clinically important changes in mean laboratory values, vital signs, or ECG parameters from Baseline to Week 23 were reported (Text S3).

3.4. Efficacy outcomes

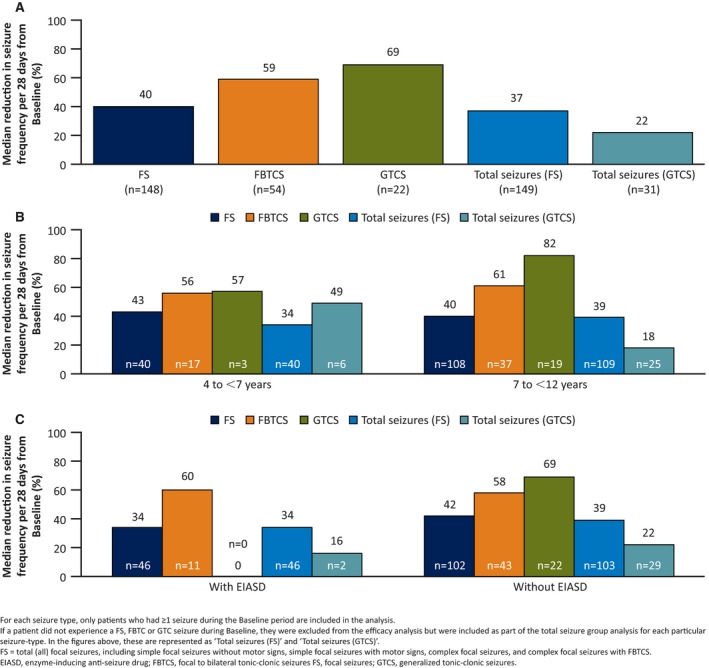

For the overall population, the median percent reduction in FS, FBTCS, and GTCS frequency per 28 days from Baseline following treatment with adjunctive perampanel was: 40% (95% confidence interval [CI] 31%‐53%; [IQR] 76), 59% (95% CI 49%‐70%; IQR 49), and 69% (95% CI 18%‐100%; IQR 82), respectively (Figure 3A). For total seizures in the FS cohort, the median percent reduction in seizure frequency from Baseline per 28 days was 37% (95% CI 31%‐51%; IQR 77) (Figure 3A). For total seizures in the GTCS cohort, the value was 22% (95% CI −12% to 57%; IQR 88) (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Median percent reduction in seizure frequency per 28 days from Baseline by seizure type for (A) all (total) patients, (B) age cohort, and (C) EIASD cohort (Full Analysis Set)

A similar reduction in seizure frequency was observed for the age and EIASD cohorts for all seizure types. For FS, median percent reduction in seizure frequency per 28 days from Baseline was 43% (95% CI 26%‐56%; IQR 48) for the 4 to <7 year cohort and 40% (95% CI 31%‐53%; IQR 81) for the 7 to <12 year cohort (Figure 3B). For total seizures in the FS cohort, these values were 34% (95% CI 25%‐56%; IQR 56) and 39% (95% CI 24%‐51%; IQR 84) for the 4 to <7 and 7 to <12 year cohorts, respectively. For the with/without concomitant EIASD cohorts, the median percent reduction for FS were 34% (95% CI −9% to 60%; IQR 93) and 42% (95% CI 32%‐54%; IQR 57), respectively (Figure 3C). For total seizures in the FS cohort, the values were 34% (95% CI −9% to 62%; with EIASD; IQR 94) and 39% (95% CI 31%‐53%; without EIASD; IQR 63).

For FBTCS, median percent reduction in seizure frequency per 28 days from Baseline was 56% (95% CI 39%‐78%; IQR 39) for younger patients and 61% (95% CI 43%‐76%; IQR 52) for older patients (Figure 3B), and 60% (95% CI 9%‐79%; IQR 59) for the with concomitant EIASDs cohort and 58% (95% CI 48%‐70%; IQR 47) for the without concomitant EIASDs cohort (Figure 3C).

For GTCS, the median percent reduction in seizure frequency per 28 days from Baseline was 57% (95% CI −1218% to 100%; IQR 1318) for younger patients, and 82% (95% CI 18%‐100%; IQR 82) for older patients (only three patients in the younger age cohort had GTCS potentially limiting comparisons with the older cohort) (Figure 3B). For total seizures in the GTCS cohort, these values were 49% (95% CI −177% to 100%; IQR 120) for patients 4 to <7 years of age and 18% (95% CI −12% to 52%; IQR 72) for patients age 7 to <12 years (Figure 2B). No patients who were taking EIASDs experienced GTCS at Baseline and, as such, were not included in the main efficacy analysis. However, in the total seizures (GTCS) cohort analysis and for two patients who were taking EIASDs, the median percent reduction in seizure frequency per 28 days from Baseline was 16% (95% CI −27% to 58%; IQR 85). In those patients with GTCS not taking concomitant EIASDs, median percent reduction in GTCS frequency per 28 days from Baseline was 69% (95% CI 18%‐100%; IQR 82) (Figure 3C). For total seizures, the values were 22% (95% CI −12% to 52%; IQR 75).

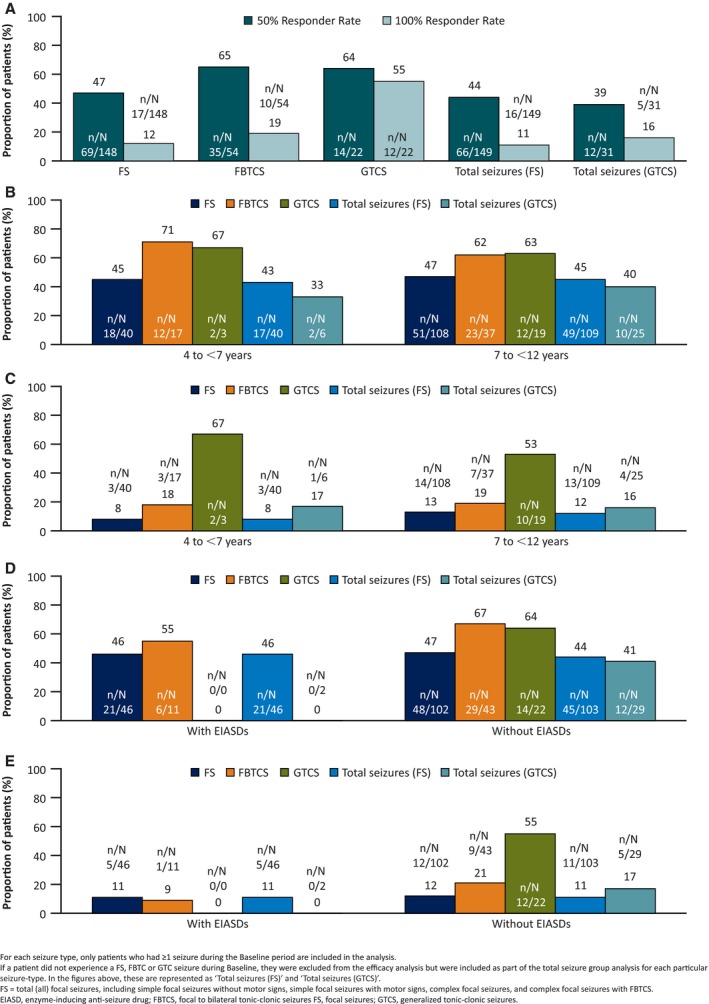

Figure 4A shows the 50% responder rates for total seizures (FS): 44%; FS: 47%; FBTCS: 65%; total seizures (GTCS): 39%; and GTCS, 64%. For total seizures (FS), FBTCS, total seizures (GTCS), and GTCS, the 50% responder rates were similar between the younger and older age cohorts (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Fifty percent responder rates and seizure‐freedom (100% responder) rates, by seizure type, during the Maintenance period for (A) all (total) patients, (B) age cohort 50% responder rate, (C) age cohort seizure‐freedom rate, (D) EIASD cohort 50% responder rate, and (E) EIASD cohort seizure‐freedom rate (Full Analysis Set, last observation carried forward)

The 50% responder rates were 46% and 55%, for FS and FBTCS, respectively, in the with EIASD cohort; and 47%, 67%, and 64% for FS, FBTCS, and GTCS, respectively, in the without EIASD cohort (Figure 4D). For the total seizures FS cohort, these values were 46% (with EIASD) versus 44% (without EIASD) and for total seizures (GTCS) were 0% versus 41% for with versus without EIASDs, respectively (Figure 4D). Seizure‐freedom (100% responders) rates are shown in Figure 4A, C, and E. Seizure freedom was obtained across all seizure types.

Using the CGIC ([LOCF] population, N = 176), 10%, 28%, and 31% of patients were “very much improved,” “much improved,” or “minimally improved” at Week 23 compared with Baseline, respectively; 23% of patients experienced “no change” from Baseline (Table S4). A similar trend was observed across the disease cohort, age cohort, and by EIASD status, with the majority of patients in each cohort showing improvement in CGIC at Week 23 compared with Baseline (Table S4).

4. DISCUSSION

As safety data cannot be extrapolated from adults to children, separate open‐label clinical studies involving ≥100 patients are required to adequately assess drug safety in patients ≥4 years of age.13 Safety and efficacy results from the 311 Core Study suggest that daily oral doses of adjunctive perampanel are generally safe, well tolerated, and efficacious in pediatric patients (aged 4 to <12 years) irrespective of seizure type, and add to existing efficacy and safety data from adult and adolescent studies with perampanel.5, 6, 7, 8

In the 311 Core Study, 67% of patients experienced a treatment‐related TEAE, which is within the range reported for treatment‐related TEAEs in Studies 304, 305, and 306 from the 8 or 12 mg/day dose cohorts (57%‐81%),5, 6, 7 but slightly lower than the proportion of patients experiencing a treatment‐related TEAE in the Core part of the open‐label, pilot Study 232 (82%) (data on file, Eisai Inc., Woodcliff Lake, NJ, USA). The most commonly reported TEAEs across all cohorts in Study 311 were somnolence and nasopharyngitis (upper respiratory tract infection [URTI]). Somnolence was a commonly reported TEAE in Studies 304, 305, 306, and 332.5, 6, 7, 8 Furthermore, URTI was also a commonly reported TEAE in the Core part of Study 232 (in addition to pyrexia; data on file, Eisai Inc.,).

The incidence of treatment‐related TEAEs and TEAEs was slightly higher in younger pediatric patients (4 to <7 years: 83% and 98%, respectively) compared with older pediatric patients (7 to <12 years; 61% and 86%, respectively). In addition, a higher proportion of younger children had a serious TEAE and/or required hospitalization or prolongation of hospitalization compared with older children (4 to <7 years: 26% vs 7 to <12 years: 10%; Table 2). Of the 25 patients who experienced hospitalizations/prolongation of hospitalization for a serious AE (SAE), seven SAEs were considered related to perampanel and four were in younger pediatric patients. However, the overall incidence of TEAEs leading to discontinuation was low and similar in both age cohorts.

ASDs have the potential to exert detrimental effects on cognitive function and compromise patient well‐being.22 Perampanel did not produce any clinically significant changes in cognitive function at Week 23 compared with Baseline.

Concomitant EIASDs such as phenytoin, carbamazepine, and oxcarbazepine (CYP3A4 inducers) can decrease perampanel plasma levels, thereby potentially reducing efficacy.4, 17 Study 311 included a with/without EIASD cohort to test any impact of concomitant EIASDs on perampanel safety and efficacy. Some flexibility in perampanel dosing (weekly titration) was permitted; patients in the with EIASD cohort (outside of Japan) could receive ≤16 mg/day perampanel (vs ≤12 mg/day for patients in the without EIASD cohort) if tolerability was not impacted and the patient would likely benefit.

The most commonly taken concomitant EIASDs at Baseline in Study 311 were carbamazepine (14%) and oxcarbazepine (11%). The mean daily perampanel dose was higher in the with EIASD cohort vs the non‐EIASD cohort (8.7 vs 6.4 mg, respectively) due to patients in the EIASD cohort being permitted to receive a greater maximum dose of perampanel (≤16 mg/day perampanel). Despite the higher overall perampanel dose in the EIASD cohort, the incidence of TEAEs was similar across both EIASD cohorts, and the incidence of AEs leading to discontinuation was low and similar.

In the 311 Core Study, reductions relative to Baseline in seizure frequency per 28 days and increased responder rates (50% and 100%) were observed across all seizure types. For FS, FBTCS, and GTCS, the median percent reduction in seizure frequency per 28 days from Baseline for patients aged 4 to <12 years was 40%, 59%, and 69%, respectively. These outcomes are generally consistent with a pooled analysis of data from adolescents and adult patients from Studies 304, 305, and 306 (N = 442, placebo; N = 686, perampanel 8 and 12 mg/day) — the median percent reduction in seizure frequency per 28 days from Baseline for perampanel 8 and 12 mg/day were 29% and 27%, respectively, for all FS, and 63% and 53%, respectively, for FBTCS.9 In Study 332, this reduction (GTCS) was 77% for perampanel 8 mg/day.8

In addition, in the 311 Core Study, 50% responder rates were 47% for FS, 65% for FBTCS, and 64% for GTCS. These outcomes are generally consistent with those observed in the pooled analysis, where 50% responder rates for perampanel 8 and 12 mg/day were 35% and 35%, respectively, for all FS, and 61% and 54%, respectively, for FBTCS.9 Similarly, in Study 332, the 50% responder rate for perampanel 8 mg/day was 64%,8 which is the same as was reported for patients with GTCS in Study 311. In the 311 Core Study and consistent with previous studies involving perampanel in adult and adolescent patients, seizure freedom was obtained across all seizure types.5, 6, 7, 8

Median percent reduction in FS seizure frequency per 28 days from Baseline in the 7 to <12 year cohort was 40%, similar to the 37% reduction for patients with FS aged ≥7 to <12 years in the Core part of Study 232 (data on file, Eisai Inc.,). For younger patients in the 311 Core Study (4 to <7 years), median reduction in FS frequency from Baseline was 43% versus a 75% reduction in FS in patients aged ≥2 to <7 years in the Core part of Study 232 (data on file, Eisai Inc.,). In the Core part of Study 232, median reduction in FBTC seizure frequency was 79% and 43% for younger and older patients, respectively (data on file, Eisai Inc.,), compared with 56% and 61% for Study 311, respectively. These differences between the studies may be partly explained by the relatively small patient population in Study 232.

For the EIASD cohort, there was a reduction in seizure frequency and an increase in responder rates (50% and 100%). This suggests no negative impact of concomitant EIASDs on perampanel efficacy in the 311 Core Study.

Study 311 also assessed perampanel’s efficacy using the CGIC23 as a measure of improvement at Week 23 relative to Baseline. Across disease, age, and concomitant EIASD cohorts, the majority of patients improved following treatment with adjunctive perampanel at Week 23 compared with Baseline.

Limitations of the 311 Core Study include the open‐label design and lack of control group. In addition, the study population diversity was limited because the majority of patients were either of Caucasian or Japanese origin, meaning additional studies in more diverse populations are warranted. There was also a smaller number of younger (n = 46; 4 to <7 years) patients compared with older (n = 134; 7 to <12 years) patients. In relation to seizure type, the number of GTCS patients was small (n = 31 in the SAS and FAS) relative to the other seizure types investigated in the study. The number of patients in the EIASD cohort was also small, making conclusions regarding perampanel’s efficacy and safety in the presence of a concomitant EIASD/s difficult. In addition, only two patients with GTCS were included in the “with” EIASD cohort (not surprising as EIASDs are not typically prescribed for GTCS24); however, neither of these patients had a GTCS at Baseline so were not included in the EIASD cohort efficacy analysis.

In conclusion, results from the 311 Core Study suggest that daily oral doses of adjunctive perampanel are generally safe, well tolerated, and efficacious in younger (4 to <7 years) and older (7 to <12 years) pediatric patients with FS (with/without FBTCS) or GTCS, regardless of Baseline concomitant EIASD status. The safety and efficacy outcomes from 311 Core Study are consistent with previous analyses of perampanel in adolescent and adult populations.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Andras Fogarasi and Robert Flamini have received honoraria for participation in an advisory board and have served as Principal Investigator at their sites. Mathieu Milh has received honoraria from Eisai for a scientific symposium and from Novartis and Advicenne for participation in advisory boards. Steven Phillips and Shinsaku Yoshitomi have no real or apparent conflicts of interest to disclose. Anna Patten is an employee of Eisai Ltd. Takao Takase is an employee of Eisai Co., Ltd. Antonio Laurenza is a former employee of Eisai Inc. Leock Y Ngo is an employee of Eisai Inc. Part of this work was first presented as posters at the 72nd Annual Meeting of the American Epilepsy Society, New Orleans, LA, USA, November 30–December 4, 2018.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this manuscript is consistent with those guidelines.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Medical writing support, under the direction of the authors, was provided by Lisa Moore, PhD, of CMC AFFINITY, a division of McCann Health Medical Communications Ltd., Macclesfield, UK, funded by Eisai Inc, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines.

Fogarasi A, Flamini R, Milh M, et al. Open‐label study to investigate the safety and efficacy of adjunctive perampanel in pediatric patients (4 to <12 years) with inadequately controlled focal seizures or generalized tonic‐clonic seizures. Epilepsia. 2020;61:125–137. 10.1111/epi.16413

Funding information

This study was funded by Eisai Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hanada T. The AMPA receptor as a therapeutic target in epilepsy: preclinical and clinical evidence. J Receptor Ligand Channel Res. 2014;7:39–50. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lattanzi S, Striano P. The impact of perampanel and targeting AMPA transmission on anti‐seizure drug discovery. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2019;14:195–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. European Medicines Agency (EMA) . Fycompa® Annex I: summary of product characteristics. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/fycompa-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed December 16, 2019.

- 4. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) . Fycompa® Prescribing Information, May 2019. Available at: https://www.fycompa.com/-/media/Files/Fycompa/Fycompa_Prescribing_Information.pdf. Accessed December 16, 2019.

- 5. Krauss GL, Serratosa JM, Villanueva V, et al. Randomized phase III study 306: adjunctive perampanel for refractory partial‐onset seizures. Neurology. 2012;78:1408–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. French JA, Krauss GL, Biton V, et al. Adjunctive perampanel for refractory partial‐onset seizures: randomized phase III study 304. Neurology. 2012;79:589–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. French JA, Krauss GL, Steinhoff BJ, et al. Evaluation of adjunctive perampanel in patients with refractory partial‐onset seizures: results of randomized global phase III study 305. Epilepsia. 2013;54:117–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. French JA, Krauss GL, Wechsler RT, et al. Perampanel for tonic‐clonic seizures in idiopathic generalized epilepsy: a randomized trial. Neurology. 2015;85:950–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Steinhoff BJ, Ben‐Menachem E, Ryvlin P, et al. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive perampanel for the treatment of refractory partial seizures: a pooled analysis of three phase III studies. Epilepsia. 2013;54:1481–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Krauss GL, Perucca E, Kwan P, et al. Final safety, tolerability, and seizure outcomes in patients with focal epilepsy treated with adjunctive perampanel for up to 4 years in an open‐label extension of phase III randomized trials: Study 307. Epilepsia. 2018;59:866–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rosati A, De Masi S, Guerrini R. Antiepileptic drug treatment in children with epilepsy. CNS Drugs. 2015;29:847–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Joseph PD, Craig JC, Caldwell PH. Clinical trials in children. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;79:357–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Food and Drug Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) . Drugs for treatment of partial onset seizures: Full extrapolation of efficacy from adults to pediatric patients 4 years of age and older. Guidance for industry. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/media/110916/download. Accessed December 16, 2019.

- 14. Pellock JM, Carman WJ, Thyagarajan V, et al. Efficacy of antiepileptic drugs in adults predicts efficacy in children: a systematic review. Neurology. 2012;79:1482–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pellock JM, Arzimanoglou A, D'Cruz O, et al. Extrapolating evidence of antiepileptic drug efficacy in adults to children ≥2 years of age with focal seizures: the case for disease similarity. Epilepsia. 2017;58:1686–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Patsalos PN. The clinical pharmacology profile of the new antiepileptic drug perampanel: a novel noncompetitive AMPA receptor antagonist. Epilepsia. 2015;56:12–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gidal BE, Ferry J, Majid O, et al. Concentration‐effect relationships with perampanel in patients with pharmacoresistant partial‐onset seizures. Epilepsia. 2013;54:1490–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Renfroe JB, Mintz M, Davis R, et al. Adjunctive perampanel oral suspension in pediatric patients from ≥2 to <12 years of age with epilepsy: pharmacokinetics, safety, tolerability, and efficacy. J Child Neurol. 2019;34:284–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. ILAE . Proposal for revised clinical and electroencephalographic classification of epileptic seizures. From the commission on classification and terminology of the international league against epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1981;22:489–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fisher RS, Cross JH, French JA, et al. Operational classification of seizure types by the International league against epilepsy: position paper of the ILAE commission for classification and terminology. Epilepsia. 2017;58:522–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brooks J, Baker GA, Aldenkamp AP. The A‐B neuropsychological assessment schedule (ABNAS): the further refinement of a patient‐based scale of patient‐perceived cognitive functioning. Epilepsy Res. 2001;43:227–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Eddy CM, Rickards HE, Cavanna AE. The cognitive impact of antiepileptic drugs. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2011;4:385–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Busner J, Targum SD. The clinical global impressions scale: applying a research tool in clinical practice. Psychiatry. 2007;4:28–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Goldenberg MM. Overview of drugs used for epilepsy and seizures: etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. P T. 2010;35:392–415. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials