Abstract

Introduction

Harmful behavior such as smoking may reflect a disturbance in the balance of goal-directed and habitual control. Animal models suggest that habitual control develops after prolonged substance use. In this study, we investigated whether smokers (N = 49) differ from controls (N = 46) in the regulation of goal-directed and habitual behavior. It was also investigated whether individual differences in nicotine dependence levels were associated with habitual responding.

Methods

We used two different multistage instrumental learning tasks that consist of an instrumental learning phase, subsequent outcome devaluation, and a testing phase to measure the balance between goal-directed and habitual responding. The testing phases of these tasks occurred after either appetitive versus avoidance instrumental learning. The appetitive versus aversive instrumental learning stages in the two different tasks modeled positive versus negative reinforcement, respectively.

Results

Smokers and nonsmoking controls did not differ on habitual versus goal-directed control in either task. Individual differences in nicotine dependence within the group of smokers, however, were positively associated with habitual responding after appetitive instrumental learning. This effect seems to be due to impaired stimulus-outcome learning, thereby hampering goal-directed task performance and tipping the balance to habitual responding.

Conclusions

The current finding highlights the importance of individual differences within smokers. For future research, neuroimaging studies are suggested to further unravel the nature of the imbalance between goal-directed versus habitual control in severely dependent smokers by directly measuring activity in the corresponding brain systems.

Implications

Goal-directed versus habitual behavior in substance use and addiction is highly debated. This study investigated goal-directed versus habitual control in smokers. The findings suggest that smokers do not differ from controls in goal-directed versus habitual control. Individual differences in nicotine dependence within smokers, however, were positively associated with habitual responding after appetitive instrumental learning. This effect seems to be due to impaired stimulus-outcome learning, thereby hampering goal-directed task performance and tipping the balance to habitual responding. These findings add to the ongoing debate on habitual versus goal-directed control in addiction and emphasize the importance of individual differences within smokers.

Introduction

Although the vast majority of smokers are aware of the severe health consequences of smoking and express a wish to quit smoking, only 2%–5% of the smokers are still abstinent a year after a quit attempt.1 This discrepancy reveals the maladaptive and inflexible nature of addictive behaviors. To account for this “intention-behaviour gap,”2 addiction theories stress the central role of goal-directed versus habitual control in addiction.3 Animal models suggest that substance use spins out of control because of an overreliance on habitual control.3,4 Studies investigating habitual versus goal-directed control in human substance use, however, yielded conflicting results with both evidence for overreliance on habitual control or impaired goal-directed control,5–9 as well as evidence for intact goal-directed control over substance use.5,9–13 This study investigated habitual versus goal-directed control in smokers relative to healthy controls as well as the relationship between habitual responding and nicotine dependence levels.

Two main regulatory systems have been proposed to drive behavior.14,15 The goal-directed system mediates behavior that is driven by goal expectancy and desire, such that decisions are based on the expected positive rewarding effects of behavior (appetitive) or the expected relief resulting from successfully avoiding aversive outcomes (avoidance). The habitual system gives rise to behavior that is automatically elicited by environmental stimuli via previously learned stimulus–response associations, because of either positive (appetitive) or negative (avoidance) reinforcement. Therefore, habits can be seen as learned patterns in which the expected outcomes of behavior no longer drive decision-making processes, and as a result, behavior may persist despite aversive consequences.

Outcome devaluation following instrumental learning is often used to test goal-directed versus habitual responding.14–16 In these procedures, an instrumental learning phase (stimulus–response–outcome) is followed by devaluation of the outcome, for example, through satiation, or through instructing participants about a devaluation of currency. A subsequent test phase assesses whether the participant is able to adjust behavior according to the change in outcome value. In the slips-of-action test,5,17,18 habitual control is reflected in perseverative responding to stimuli signaling the availability of no-longer-valuable (devalued) outcomes following an instrumental learning phase in which responding for those outcomes was positively reinforced by earning points. Using the slips-of-action test, dominance of habitual versus goal-directed control has been demonstrated in patients with obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD),19 Gilles de la Tourette syndrome,17 and cocaine-dependent individuals.5 The use of generic stimuli in the slips-of-action test, rather than population-specific stimuli (eg, smoking stimuli in the context of this study), has the advantage of being able to compare smokers with a control group, as well as to compare studies across different populations.

Hogarth et al.11–13 took a different approach and investigated goal-directed versus habitual control of cigarette versus chocolate stimuli. In these studies, smokers learned response–outcome contingencies to win cigarettes and chocolate, after which smoking was devalued by health warnings, satiety, or nicotine replacement therapy. During a subsequent choice test, smokers were able to reduce responding for cigarettes, indicating that smoking behavior was under goal-directed control.11,12 These findings, therefore, suggest goal-directed control of smoking behavior. Hogarth et al.18,19 also compared daily and non-daily smokers in outcome devaluation procedures. In these studies, outcome devaluation sensitivity did not differ between daily and non-daily smokers suggesting that individual differences in nicotine dependence may not be related to habitual control over smoking. However, the choice test in these studies may not have been optimally sensitive to detect habits as no stimuli were shown in the test phase to trigger the learnt responses for cigarettes. Therefore, competition between the goal-directed and habitual control systems during the test phase was limited. Furthermore, the daily smokers in these studies smoked nine cigarettes a day on average, implying that the severe end of nicotine dependence was not included in these studies.

Most experimental paradigms, including the slips-of-action test, test habit propensity after appetitive instrumental learning during which participants are rewarded for correct responses. Although such procedures resemble positive reinforcement involved in substance use, negative reinforcement is also crucially involved in substance use20 and may affect the balance between goal-directed and habitual control.21,22 The balance between goal-directed and habitual control following avoidance instrumental learning has been measured using paradigms in which participants are trained to avoid aversive outcomes by responding to specific stimuli each associated with shocks to the left or right wrists.23,24 In the outcome devaluation phase, participants are made aware that they can no longer receive shocks to one of the wrists after which responses to the associated stimuli are measured. Using such procedures, evidence has been gathered to suggest that patients with OCD are less sensitive to devaluation after overtraining specifically (and not after a brief training session),23 suggesting that habitual responding was probed in this paradigm. Only one study so far used this paradigm to study addiction. It was found that, in contrast to findings after appetitive instrumental learning, both cocaine-dependent individuals and controls did not develop habitual responding following instrumental avoidance learning.5 Altogether, this suggests that habitual responding may differ depending on whether learning is positively or negatively reinforced.

Here, we investigated habitual versus goal-directed control following appetitive and avoidance learning in both smokers and nonsmokers. In addition, individual differences within smokers were investigated by testing the association between nicotine dependence levels and habit propensity based on the theoretical claims that especially the most severe end of the dependency spectrum should be associated with habitual control.3 Given previous conflicting results in human studies in addiction,25 we did not have strong expectations as to whether or not observing differences between smokers and controls in habitual responding.

Methods

Participants

A power calculation (repeated measures-analysis of variance [RM-ANOVA] between-subjects factors, medium effect size f = 0.25 and α = .05) showed that 94 participants were required to obtain 80% power for our main analysis. Forty-nine smokers (Mage = 27.69, SDage = 11.01, 52% male; Mcigarettes a day = 17.58, SDcigarettes a day = 5.06) and 46 nonsmokers (Mage = 27.39, SDage = 13.09, 35% male) participated in this study (see Table 1 for further participant characteristics). One smoker was excluded from all analyses because of missing questionnaire data. Smokers smoked at least 10 cigarettes a day and smoked on a daily basis for at least 1 year. Nonsmokers smoked on 10 or fewer occasions lifetime. Smokers refrained from smoking for 1 hour before study participation. The ethics committee of the Department of Psychology, Education and Child Studies of the Erasmus University Rotterdam approved the study. All participants provided informed consent. A carbon monoxide breath sample was taken and participants completed questionnaires on demographics, smoking behavior, the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND),26,27 Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test,28 and Barratt Impulsiveness Scale.29 Task order for the appetitive and the avoidance instrumental learning tasks was counterbalanced. Participants either received course credits or participated voluntarily.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Smokers (N = 48) | Nonsmokers (N = 46) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Range | Mean | SD | Range | t/Χ 2 | p (95% CI) | |

| Gender (% male) | 52 | 35 | 2.86 | .091 | ||||

| Education | ||||||||

| % Low | 12 | 7 | 0.97 | .615 | ||||

| % Medium | 19 | 22 | ||||||

| % High | 69 | 71 | ||||||

| Age | 27.69 | 11.01 | 18–60 | 27.39 | 13.09 | 18–63 | –0.12 | .906 (–5.24 to 4.65) |

| CO breath (ppm) | 11.48 | 7.30 | 2–38 | 0.89 | 1.04 | 0–3 | –9.95 | .000 (–12.73 to –8.45) |

| AUDIT | 9.21 | 5.69 | 0–22 | 4.35 | 3.85 | 0–15 | –4.87 | .000 (–6.85 to –2.87) |

| BIS-11 impulsivity | 64.33 | 9.34 | 48–93 | 59.76 | 8.06 | 45–79 | –2.54 | .013 (–8.15 to –.99) |

| FTND | 4.29 | 2.04 | 0–9 | |||||

| Smoking days per week | 6.98 | 0.14 | 6–7a | |||||

| Cigarettes per day | 17.58 | 5.06 | 9–30a | |||||

| Years smoking | 11.82 | 11.59 | 1–50 | |||||

| Last cigarette before testing (min) | 175.52 | 205.21 | 20–720b |

AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test; BIS-11 = Barratt Impulsiveness Scale; CI = confidence interval; CO = carbon monoxide; FTND = Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence; ppm = parts per million.

aAlthough all smokers indicated to be a daily smoker and to smoke at least 10 cigarettes a day during screening, during testing in the laboratory one smoker indicated to smoke 6 days a week on average and one smoker indicated to smoke nine cigarettes a day.

bTwo smokers did not comply with the 1 hour nonsmoking restriction before testing and smoked their last cigarette 20 and 30 minutes before testing.

Appetitive Instrumental Learning Task

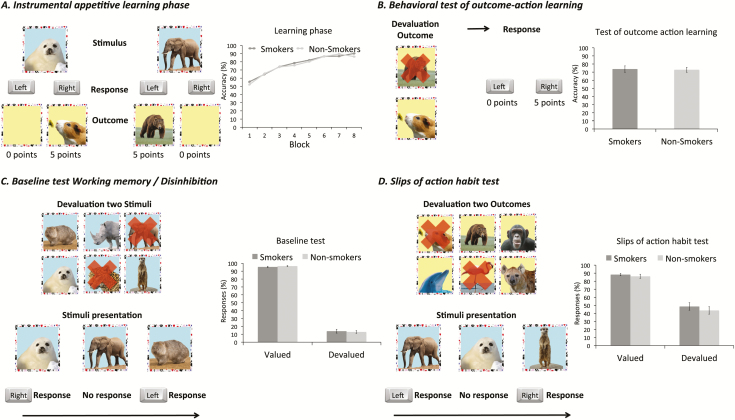

The appetitive instrumental learning task was exactly the same as in a previous study in cocaine-dependent individuals5 (Figure 1 and Supplementary Materials). During the instrumental appetitive learning phase consisting of 96 trials, participants learned associations between stimuli, responses, and outcomes that were worth points. The behavioral test of action-outcome learning assessed how well participants learned the associations between the outcomes and responses that earned them. Two outcomes were simultaneously presented on the screen. One of these outcomes was no longer valuable and participants had to perform the response associated with the still valuable outcome to win points.

Figure 1.

Appetitive instrumental learning task. (A) During the instrumental appetitive learning phase participants learn stimulus–response–outcome associations, which is stimulated by a reward system. (B) In the behavioral test of action-outcome learning, one of the two displayed outcomes is devalued. The participants are instructed to respond with the correct response that is associated with the outcome. (C) During the baseline test, participants are exposed to all six stimuli, of which two are devalued. After the stimuli exposure, stimuli appear on the screen one by one and participants are asked to respond with the learned correct response unless the stimulus is devalued. (D) In the slips-of-action test, all outcomes are shown to the participants. Two of these outcomes are devalued. After outcome presentation, the associated stimuli appear on the screen one by one. Participants are asked to respond with the correct learned response unless the associated outcome of the stimulus is devalued. Participants who have a stronger habit tendency will automatically respond to the stimuli with the learned response regardless the value of the associated outcome.

This initial test was followed by either the slips-of-action test, probing the balance between goal-directed and habitual responding, or a baseline test that controlled for working memory and disinhibition.18,30 During slips-of-action test, all six outcomes from training were first presented on screen, with two outcomes being devalued, as indicated by a red cross and the instruction that responding to stimuli associated with devalued outcomes would lead to subtraction of points. By responding to stimuli associated with valuable outcomes participants could earn points. After this devaluation screen, stimuli were presented to participants in a continuous stream. Continuing to respond to stimuli associated with devalued outcomes is supposed to reflect habitual responding.

The baseline test was identical to the slips-of-action test, except that stimuli rather than outcomes were devalued. As such, task performance was independent on knowledge of action–outcome associations but reflects participants’ ability to inhibit responses based on memory of the devalued stimuli.

Finally, a questionnaire to test explicit knowledge on the learned stimulus–response, stimulus–outcome, and response–outcome associations was completed.

Avoidance Instrumental Learning Task

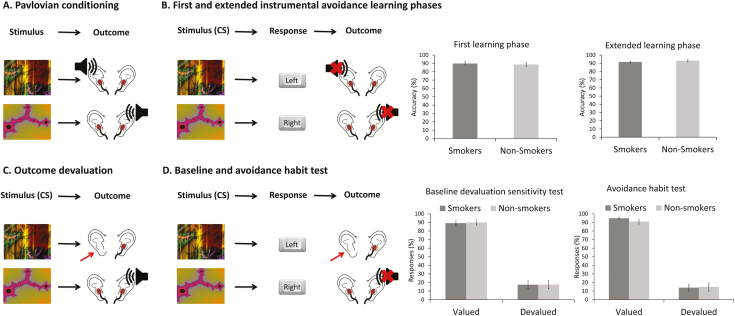

The current version of the avoidance instrumental learning task was based on previous studies5,23,24 (Figure 2 and Supplementary Materials). Loud high-pitch tones were used as aversive outcomes instead of shocks. Participants were first told that two visual stimuli would predict the delivery of an aversive noise outcome. If they saw one of these stimuli, the aversive noise would be imminently delivered to their left or right ear. They were then shown the stimuli and the noises were delivered, thus establishing the Pavlovian contingency between stimuli and noise outcomes. The loudness of the high-pitch tones was individually determined so that participants were motivated to avoid the tone.

Figure 2.

Avoidance instrumental learning task. (A) First participants are exposed to the stimuli and the aversive noise in the associated ear to establish learning of the stimuli–outcome associations by means of Pavlovian conditioning. (B) During the first and extended instrumental avoidance learning phases, participants learn to avoid the aversive noise by giving the correct response associated with the Stimuli. The first instrumental avoidance learning phase consists of 12 trials and is followed by outcome devaluation (C) and the first extinction phase, that is, the baseline devaluation sensitivity test (D). After the baseline devaluation sensitivity test, the participants are overtrained in the extended instrumental avoidance learning phase in 120 trails. After the extended instrumental avoidance learning phase, there is again outcome devaluation (C) followed by the avoidance habit test (D). (C) During outcome devaluation one of the earplugs is removed so that the outcome to the corresponding stimulus is devalued, that is, participants will not hear the aversive noise if they do not respond to the corresponding stimulus in the extinction phases. (D) During the baseline devaluation sensitivity and avoidance habit test, participants are instructed to avoid the aversive noises. Participants who have a stronger habit tendency will continue to respond to the stimuli regardless the value of the associated outcome.

Subsequently, participants were informed that they could avoid the noises (outcomes) by pressing (responses) the right or left key during stimuli presentation, the number of required responses varied between 1 and 3. During the first instrumental avoidance learning phase, consisting of 12 trials, participants were instructed to avoid the noise that would otherwise follow stimulus presentation. If participants did not make the correct response, the noise was played to the corresponding ear. Subsequently, in the baseline devaluation sensitivity test participants’ baseline devaluation sensitivity in extinction was tested by disconnecting one earplug from participants’ ears, thereby devaluing that aversive outcome. We presented participants with the stimuli from learning in 24 trials and assessed if they would selectively respond to avoid the valuable outcome but refrain from responding to avoid the now devalued outcome. After reconnected the earphones, participants were overtrained in the extended instrumental avoidance learning phase that lasted for 120 trials. Next, we conducted the avoidance habit test (24 trials), after disconnecting one of the earphones. The percentage of responses to the stimulus associated with the devalued outcome (the disconnected headphone) relative to the valued outcome during the avoidance habit test was the index of habitual responding.

Participants rated the unpleasantness of the noises before and after task performance. After task performance, participants reported explicit knowledge of stimulus–outcome and stimulus–response associations.

Analyses

Accuracy rates (percentage of correct responses to the stimuli) in the instrumental appetitive learning phase were analyzed using RM-ANOVA with Block as eight-level within-subject factor and Group as two-level between-subjects factor (smokers, nonsmokers). Accuracy rates (percentage of responses for the valued outcome) in the behavioral test of action-outcome learning were analyzed using a univariate ANOVA with Group as two-level between-subjects factor. Separate RM-ANOVAs were performed for the percentage of responses for the slips-of-action test and the baseline test both with Value as two-level within-subject factor (valued, devalued) and Group as two-level between-subjects factor.

Univariate ANOVAs with Group as two-level between-subjects factor were performed for accuracy rates during both the first and extended instrumental avoidance learning phases. RM-ANOVAs were performed with Value as two-level within-subject factor and Group as a two-level between-subjects factor for both the baseline devaluation sensitivity test and the avoidance habit test.

Univariate ANOVAs with Group as two-level between-subjects factor were performed for explicit knowledge on the appetitive and avoidance instrumental learning tasks. Age was included as a covariate in all analyses given the wide age range in the current sample and the effect of age on goal-directed versus habitual controls.31 Greenhouse-Geisser corrections were applied if the assumption of sphericity was violated. All analyses were also performed for reaction times (results are reported in supplementary materials).

Kendall’s tau correlations were calculated to test the association between nicotine dependence levels within smokers and goal-directed versus habitual responding for both tasks using difference scores for the percentage of responses to stimuli associated with valued minus devalued outcomes (the devaluation scores). Hierarchical multiple regression analyses were performed to test whether or not control variables accounted for the association between nicotine dependence and habitual responding. Data are publically available via data archiving and networked services. https://doi.org/10.17026/dans-zsf-94p8

Results

Appetitive Instrumental Learning Task

Five participants were excluded from the analyses for the appetitive instrumental learning task because of missing or incomplete data. See Supplementary Table 1 for task performance data.

A main effect of Block was found during the instrumental appetitive learning phase, F(5.42,465.78) = 15.79, p < .001, eta2 = .16, indicating increasing accuracy of stimulus–response learning over the eight blocks. No Group or Group × Block interaction effects were observed, F(1,86) = 0.60, p = .440, 95% CI = –5.80 to 2.54, eta2 = .01, and F(5.42,465.78) = 1.78, p = .111, eta2 = .02, respectively.

Accuracy scores during the behavioral test of action-outcome learning did not differ between smokers and controls, F(1,86) = 0.05, p = .823, 95% CI = –11.14 to 8.88, eta2 = .00.

A main effect of Value was found for the baseline test, showing that the percentage of responses to valued stimuli was higher than that of responses to devalued stimuli, F(1,86) = 405.12, p < .001, eta2 = .83 (Mvalued = 95.94, SDvalued = 5.00; Mdevalued = 13.42, SDdevalued = 14.02). Neither the Group × Value nor the main effect of Group for the percentage of responses was significant, F(1,86) = 0.26, p = .611, eta2 = .02 and F(1,86) = .00, p = .971, 95% CI = –2.78 to 2.88, eta2 = .00, respectively.

A main effect of Value during the slips-of-action test showed that participants responded more often to stimuli associated with valuable outcomes compared to the stimuli associated with devalued outcome, F(1,86) = 63.59, p < .001, eta2 = .43, Mvalued = 87.16, SDvalued = 13.68; Mdevalued = 46.16, SDdevalued = 30.87. Neither the Group × Value nor the main effect of Group was significant for the percentage of responses during slips-of-action test, F(1,86) = 0.06, p = .806, eta2 = .00 and F(1,86) = 0.94, p = .335, 95% CI = –10.07 to 3.47, eta2 =.01, respectively, suggesting no differences between groups in habitual responding after appetitive learning. As the Group × Value interaction tested our main hypothesis, we further examined this null-finding with Bayesian statistics. Using standard priors as implemented in JASP, a Bayes Factor10 of .217 was observed, suggesting substantial evidence for the null hypothesis of no interaction.

Finally, smokers and nonsmokers did not differ in their explicit knowledge on stimulus–response, outcome–response, and stimulus–outcome associations, F(1,86) = 0.00, p = .980, 95% CI = –0.11 to 0.11, eta2 = .00, F(1,86) = 0.90, p = .347, 95% CI = –0.06 to 0.16, eta2 = .01, and F(1,86) = 0.00, p = .980, 95% CI = –0.13 to 0.14, eta2 = .00, respectively.

The analyses reported here suggest that smokers as a group did not differ from nonsmokers in the balance between goal-directed and habitual control and related measures. However, it remains possible that more severely dependent smokers were relatively impaired. To investigate this possibility, we examined the relationship between smoking severity and performance on the slips-of-action test. Strong evidence was found for the association between individual differences in nicotine dependence levels and habitual responding during the slips-of-action test rτ = –.34, p = .002, BF10 = 37.58 (Supplementary Figure 1). To unravel the specificity of, and mechanisms contributing to this association, exploratory correlations were calculated. Strong evidence was obtained for a negative association between FTND scores and explicit knowledge on stimulus–response, rτ = –.30, p = .019, BF10 = 10.42, and stimulus–outcome associations, rτ = –.30, p = .010, BF10 = 12.24, whereas inconclusive evidence was obtained for the associations between FTND scores and explicit knowledge of outcome–response associations, rτ = –.19, p = .106, BF10 = 1.07, learning during the instrumental appetitive learning phase (averaged accuracy over the eight blocks), rτ = –.16, p = .150, BF10 = 0.63, and the percentage of responses to valued versus devalued stimuli in the baseline test, rτ = –.15, p = .168, BF10 = 0.57.

A hierarchical regression analysis investigated whether FTND scores explains additional variance in habitual responding after including control variables consisting of age, impulsivity, alcohol use, percentage of responses to valued versus devalued stimuli in the baseline test, and explicit knowledge of stimulus–response and stimulus–outcome associations. Together, these control variables explained variance in habitual responding, F(6,38) = 16.57, p < .001, R2 = .72, with knowledge of stimulus–outcome knowledge as the only significant predictor, t(38) = 6.87, p < 0.001, 95% CI = 53.55 to 98.28, β = .73. FTND scores in the next step did not explain significantly additional variance, Fchange(1,37) = 1.92, p = .174, R2change = .01. Altogerther, these additional analyses suggest that the association between nicotine dependence and habitual responding may be due to reduced stimulus–outcome learning in severely nicotine-dependent smokers.

Avoidance Instrumental Learning Task

Three participants were excluded from the analyses for the avoidance instrumental learning task because of missing or incomplete data. See Supplementary Table 2 for task performance data.

Accuracy rates did not differ between smokers and nonsmokers during both the first, F(1,88) = 0.15, p = .704, 95% CI = –7.18 to 4.87, eta2 = .00, and extended instrumental avoidance learning phases, F(1,88) = 0.78, p = .374, 95% CI = –1.98 to 5.21, eta2 = .01.

During the baseline devaluation sensitivity test, the percentage of responses was higher for both groups to valued stimuli compared to the devalued stimuli, as indicated by a main effect of Value, F(1,88) = 51.02, p < .001, eta2 = .37 (Mvalued = 89.50 SDvalued = 19.56; Mdevalued = 17.40, SDdevalued = 31.88). Smokers and nonsmokers did not differ in their percentage of responses, as Group × Value and Group effects were not significant, F(1,88) = 0.01, p = .927, eta2 = .00 and F(1,88) = 0.02, p = .892, 95% CI = –6.51 to 7.47, eta2 = .00, respectively.

During the avoidance habit test, a main effect of Value was found, F(1,88) = 99.38, p = .000, eta2 = .53 (Mvalued = 92.95, SDvalued = 14.54; Mdevalued = 14.29, SDdevalued = 30.84). No significant Group and Group × Value effects were found, F(1,88) = 0.17, p = .680, 95% CI = –8.74 to 5.72, eta2 = .00 and F(1,88) = 0.46, p = .501, eta2 = .01, respectively. As the Group × Value interaction reflects our main hypothesis, we further tested this null-finding with Bayesian statistics. A Bayes Factor10 of .269 was observed suggesting substantial evidence for the null hypothesis of no interaction. These results show that responding to stimuli associated with devalued outcomes does not differ between smokers and controls after overtraining of avoidance learning.

An additional analysis, testing whether the devaluation effect differs between the baseline devaluation sensitivity test and the avoidance habit test, did not show an interaction effect between Value and Test Phase F(1,88) = 0.85, p = .358, eta2 = .01, suggesting that participants did not respond more often to stimuli associated with devalued outcomes after overtraining of avoidance learning.

Explicit knowledge about stimulus–response and stimulus–outcome associations, as well as the knowledge of which earplug was disconnected during the avoidance habit test did not differ between groups, F(1,88) = 0.01, p = .942, 95% CI = –0.06 to 0.06, eta2 = .00, F(1,88) = 0.07, p = .799, 95% CI = –0.06 to 0.07, eta2 = .00, and F(1,88) = 1.76, p = .188, 95% CI = –0.19 to 0.04, eta2 = .02, respectively. Smokers, however, experienced a stronger urge to respond to the stimulus associated with a devalued outcome compared to nonsmokers, F(1,87) = 5.50, p = .021, 95% CI = –1.79 to –0.15, eta2 = .06, and this urge to respond was associated with the devaluation score across groups rτ = –.35, p < .001, BF10 = 18854.41, suggesting that a stronger urge to response was associated with more responding to stimuli signaling devalued outcomes. Both groups rated the unpleasantness of the noises at the same level for both ears as no significant effects in ratings were found for Group, Devalued Side (left versus right) and Time (before versus after task performance), F(1,66) = 1.99, p = .163, 95% CI = –11.67 to 2.01, eta2 = .03, F(1,66) = 0.84, p = .362, eta2 = .01, and F(1,66) = 0.60, p = .442, eta2 = .01, respectively.

Moderate evidence was observed for a lack of an association between nicotine dependence levels and habitual responding during the avoidance habit test rτ = .01, p = .916, BF10 = .19 (Supplementary Figure 1). The control variables age, alcohol use, and impulsivity in the hierarchical regression analyses were not associated with habitual responding, F(3,44) = 0.60, p = .477, R2 = .05. FTND scores in the next step did not explain additional variance, Fchange(1,43) = 0.02, p = .898, R2change = .00. Thus, habitual control after avoidance learning was not stronger in severely dependent smokers.

When correlating the devaluation score of the slips-of-action test and the devaluation score of the avoidance habit test strong evidence was observed for a positive association, rτ = .24, p = .002, BF10 = 32.15, in line with the notion that these two measures partly reflect similar processes.

Discussion

This study investigated habitual versus goal-directed control after appetitive and avoidance instrumental learning in smokers. No differences for smokers and nonsmokers were observed for goal-directed versus habitual control. Higher levels of nicotine dependence within smokers, however, were associated with increased habitual responding after appetitive instrumental learning only. Exploratory analyses showed that nicotine dependence levels were negatively associated with explicit knowledge of stimulus–response and stimulus–outcome contingencies after appetitive instrumental learning, suggesting that habitual responding in severely dependent smokers may be the result of compromised goal-directed learning.

These findings shed some light on the nature of the imbalance between goal-directed and habitual control in highly dependent smokers. Increased habitual responding in highly dependent smokers is likely to be due to a failure to learn to anticipate outcomes on the basis of stimuli in the environment (stimulus–outcome associations). Therefore, these findings suggest that reliance on habits in this subgroup of smokers is the consequence of impaired goal-directed learning, as opposed to aberrantly enhanced stimulus–response learning. This idea is in line with the conclusion of a recent article, suggesting that goal-directed impairments are more likely to be responsible for interindividual variability in the imbalance between habitual and goal-directed control.32 In future, neuroimaging studies can contribute to unraveling the nature of the dual-system imbalance by measuring activity in both goal-directed and habit-related brain systems during task performance. This important question should be further explored, not only in the context of limited training, as in this study, but also after more extensive instrumental training, thereby offering more opportunity for strong habit formation and allowing one to dissociate between weak goal-directed control and strong habit formation33 (but see also de Wit et al.34).

Our finding that more severe nicotine dependence levels are associated with compromised goal-directed appetitive learning and consequentially enhanced habitual control, whereas smokers as a group do not differ from nonsmoking controls, emphasizes the relevance of individual differences amongst smokers. Currently, individual differences within smokers are increasingly considered in the development of interventions, given that the variety of smoking behavior that occurs within the population is increasing. Given the compromised goal-directed learning in highly dependent smokers, future interventions tailored for this group should specifically aim to change automatic behavior, for example, by using implementation intentions,35 by retraining automatic approach tendencies,36 or by adapting current habit reversal therapies to smoking.37

The lack of group differences between smokers and controls after appetitive instrumental learning is in contrast with earlier findings using the same slips-of-action test in cocaine-dependent individuals.5 Generally, findings on habitual versus goal-directed control in various addicted populations using different task paradigms (all using nonsubstance-related reinforcers) have been mixed with no associations between goal-directed or habitual control and alcohol use in young adults,10 and no difference between controls and abstinent alcohol-dependent patients9 and inpatient drug users.25 Other studies in alcohol-dependent individuals, however, did show reduced goal-directed control,6 as well as reduced medial prefrontal cortex activation during goal-directed decision-making as predictor for alcohol relapse.7 A bias toward habitual control was observed in methamphetamine-dependent individuals.9 Altogether, these studies and the findings of this study seem to suggest that goal-directed versus habitual control is not consistently compromised across different addictive behaviors, with the more severe end of the spectrum of addictive behaviors more likely to be affected. In addition, the observation that there is a large overlap in responding on the slips-of-action test for smokers and nonsmoking controls (Supplementary Table 1), and the notion that habitual responding has previously been linked to different types of inflexible behavior including eating9 and internet use,38 suggests that habitual responding in combination with a preference for tobacco may be associated with severe nicotine dependence, whereas the same type of habitual responding in nonsmokers may result in different types of inflexible behavior.

Previous studies,39,40 in which devaluation procedures were targeted to devalue smoking behavior specifically, did not show a difference between daily and non-daily smokers (used as a proxy for nicotine dependence levels). The contrast with these findings may be because of the differences in methods used to test outcome devaluation sensitivity. The slips-of-action test may offer a more sensitive measure than simple choice tests because here participants are confronted with stimuli that can elicit learned responses through stimulus–response associations. Furthermore, the slips-of-action test is conducted under time pressure, which should offer an advantage for the faster and more efficient habit system over the goal-directed system. Other possibly relevant differences between this study and those by Hogarth et al. are the conceptualization of dependence (a continuous measure of dependence score versus a comparison of daily versus non-daily smokers), and the types of smokers included in the two studies. Smokers in this study smoked on average about 18 cigarettes a day and were therefore more severely dependent than the smokers in the studies by Hogarth et al. who smoked nine cigarettes a day on average. Therefore, the smokers in this study may represent the subpopulation of relatively severe smokers showing reduced outcome devaluation sensitivity.

This finding that smoking status and individual differences in nicotine dependence levels were not associated with compromised goal-directed versus habitual control after avoidance instrumental learning may suggest that habitual versus goal-directed control is valence-dependent. Using almost exactly the same task paradigms as in this study to measure habitual versus goal-directed control after both appetitive and avoidance instrumental learning, a previous study observed increased habitual control in cocaine-dependent individuals after appetitive but not avoidance instrumental learning.5 Given that substance use in the early stage is mostly driven by positive reinforcing effects, representing appetitive instrumental learning, it may be that those individuals with compromised goal-directed control or those with enhanced habitual control after appetitive learning are also the ones who developed more severe nicotine dependence. However, differences in the two used task paradigms to measure habitual responding after appetitive versus avoidance learning could also account for the observed findings. Although the development of habits was previously observed after overtraining in the avoidance instrumental learning task in patients with OCD,23 this study, as well as previous investigations using this task5 could not show increased responding to stimuli associated with devalued outcomes after overtraining of avoidance. It may be that the slips-of-action test is a more suitable measure compared to the avoidance habit test because of the requirement to learn multiple stimulus–response–outcome contingencies and testing under time pressure, thereby challenging goal-directed control or favoring responding driven by stimulus–response habits. To more critically test differential development of habitual responding after appetitive or avoidance learning, we suggest that future studies test habitual responding using equi-sensitive versions of the same task paradigm.

In line with previous findings in patients with OCD,23,24 smokers showed a stronger urge to respond to the stimulus associated with devalued outcomes in the avoidance instrumental learning task compared to controls, and the urge to respond was associated with more habitual responding across groups. The findings in patients with OCD additionally show that these patients report to respond to the stimulus associated with the devalued outcome because of threat beliefs.23 Future studies in the context of addiction can benefit from a more thorough investigation of the subjective aspects of responding to stimuli signaling devalued outcomes to unravel associated subjective beliefs.

Its cross-sectional character is a limitation of this study, as it hampers the causal interpretation of the association between compromised goal-directed learning and nicotine dependence levels. To gain more insight in the directionality of this effect, longitudinal studies in individuals at risk to develop dependence would be necessary.

In conclusion, the findings of this study indicate that smokers do not differ from controls in habitual versus goal-directed control after either after appetitive or avoidance instrumental learning. Higher nicotine dependence levels within smokers, however, were associated with increased habitual control after appetitive instrumental learning, most likely because of compromised stimulus–outcome learning thereby hampering goal-directed task performance and tipping the balance to habitual responding. Whether or not goal-directed versus habitual control is compromised across human addictive behaviors remains a subject for further study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Marielle van der Burg, Annelie Han, Tessa Hartman, and Melian Boon for their assistance with participant recruitment and data collection. Design and analyses of the current manuscript were not preregistered.

Funding

This research is funded by a VENI grant (nr. 451-15-029) from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) to M. Luijten. NWO had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Declaration of Interests

ML, CMG, SW, IHAF, and KDE declare no conflicts of interest. TWR consults for Cambridge Cognition and receives royalties for the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery. He also currently consults for Lundbeck and Multipharma and holds a research grant from Shionogi.

References

- 1. International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation P. ITC Project: Netherlands National Report. The Hague, The Netherlands: STIVORO; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tiffany ST. A cognitive model of drug urges and drug-use behavior: role of automatic and nonautomatic processes. Psychol Rev. 1990;97(2):147–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Drug addiction: updating actions to habits to compulsions ten years on. Annu Rev Psychol. 2016;67:23–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Clemens KJ, Castino MR, Cornish JL, Goodchild AK, Holmes NM. Behavioral and neural substrates of habit formation in rats intravenously self-administering nicotine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39(11):2584–2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ersche KD, Gillan CM, Jones PS, et al. Carrots and sticks fail to change behavior in cocaine addiction. Science. 2016;352(6292):1468–1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sebold M, Deserno L, Nebe S, et al. Model-based and model-free decisions in alcohol dependence. Neuropsychobiology. 2014;70(2):122–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sebold M, Nebe S, Garbusow M, et al. When habits are dangerous: alcohol expectancies and habitual decision making predict relapse in alcohol dependence. Biol Psychiatry. 2017;82(11):847–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sjoerds Z, de Wit S, van den Brink W, et al. Behavioral and neuroimaging evidence for overreliance on habit learning in alcohol-dependent patients. Transl Psychiatry. 2013;3:e337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Voon V, Derbyshire K, Rück C, et al. Disorders of compulsivity: a common bias towards learning habits. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20(3):345–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nebe S, Kroemer NB, Schad DJ, et al. No association of goal-directed and habitual control with alcohol consumption in young adults. Addict Biol. 2018;23(1):379–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hogarth L. Goal-directed and transfer-cue-elicited drug-seeking are dissociated by pharmacotherapy: evidence for independent additive controllers. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process. 2012;38(3):266–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hogarth L, Chase HW. Parallel goal-directed and habitual control of human drug-seeking: implications for dependence vulnerability. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process. 2011;37(3):261–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hogarth L, Dickinson A, Duka T. The associative basis of cue-elicited drug taking in humans. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2010;208(3):337–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Balleine BW, O’Doherty JP. Human and rodent homologies in action control: corticostriatal determinants of goal-directed and habitual action. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(1):48–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. de Wit S, Dickinson A. Associative theories of goal-directed behaviour: a case for animal-human translational models. Psychol Res. 2009;73(4):463–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Corbit LH, Janak PH. Habitual alcohol seeking: neural bases and possible relations to alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40(7):1380–1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Delorme C, Salvador A, Valabrègue R, et al. Enhanced habit formation in Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Brain. 2016;139(Pt 2):605–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Worbe Y, Savulich G, de Wit S, Fernandez-Egea E, Robbins TW. Tryptophan depletion promotes habitual over goal-directed control of appetitive responding in humans. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;18(10):pyv013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gillan CM, Papmeyer M, Morein-Zamir S, et al. Disruption in the balance between goal-directed behavior and habit learning in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(7):718–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Koob GF, Le Moal M. Plasticity of reward neurocircuitry and the ‘dark side’ of drug addiction. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(11):1442–1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hogarth L, Hardy L. Depressive statements prime goal-directed alcohol-seeking in individuals who report drinking to cope with negative affect. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2018;235(1):269–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hogarth L, He Z, Chase HW, et al. Negative mood reverses devaluation of goal-directed drug-seeking favouring an incentive learning account of drug dependence. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2015;232(17):3235–3247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gillan CM, Morein-Zamir S, Urcelay GP, et al. Enhanced avoidance habits in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;75(8):631–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gillan CM, Apergis-Schoute AM, Morein-Zamir S, et al. Functional neuroimaging of avoidance habits in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(3):284–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hogarth L, Lam‐Cassettari C, Pacitti H, et al. Intact goal-directed control in treatment-seeking drug users indexed by outcome-devaluation and Pavlovian to instrumental transfer: critique of habit theory. Eur J Neurosci. 2018. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerström tolerance questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vink JM, Willemsen G, Beem AL, Boomsma DI. The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence in a Dutch sample of daily smokers and ex-smokers. Addict Behav. 2005;30(3):575–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption–II. Addiction. 1993;88(6):791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J Clin Psychol. 1995;51(6):768–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. de Wit S, Watson P, Harsay HA, Cohen MX, van de Vijver I, Ridderinkhof KR. Corticostriatal connectivity underlies individual differences in the balance between habitual and goal-directed action control. J Neurosci. 2012;32(35):12066–12075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. de Wit S, van de Vijver I, Ridderinkhof KR. Impaired acquisition of goal-directed action in healthy aging. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2014;14(2):647–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gillan CM, Otto AR, Phelps EA, Daw ND. Model-based learning protects against forming habits. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2015;15(3):523–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Watson P, de Wit S. Current limits of experimental research into habits and future directions. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2018;20:33–39. [Google Scholar]

- 34. de Wit S, Kindt M, Knot SL, et al. Shifting the balance between goals and habits: Five failures in experimental habit induction. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2018;147(7):1043–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Armitage CJ. Evidence that implementation intentions can overcome the effects of smoking habits. Health Psychol. 2016;35(9):935–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wiers RW, Eberl C, Rinck M, Becker ES, Lindenmeyer J. Retraining automatic action tendencies changes alcoholic patients’ approach bias for alcohol and improves treatment outcome. Psychol Sci. 2011;22(4):490–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bate KS, Malouff JM, Thorsteinsson ET, Bhullar N. The efficacy of habit reversal therapy for tics, habit disorders, and stuttering: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31(5):865–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhou B, Wang W, Zhang W, Li Y, Nie J. Succumb to habit: behavioral evidence for overreliance on habit learning in Internet addicts. Comput Hum Behav. 2018;89:230–236. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hogarth L, Chase HW, Baess K. Impaired goal-directed behavioural control in human impulsivity. Q J Exp Psychol (Hove). 2012;65(2):305–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hogarth L, Chase HW. Evaluating psychological markers for human nicotine dependence: tobacco choice, extinction, and Pavlovian-to-instrumental transfer. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;20(3):213–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.