Abstract

Introduction:

Internet of Things (IoT), which provides smart services and remote monitoring across healthcare systems according to a set of interconnected networks and devices, is a revolutionary technology in this domain. Due to its nature to sensitive and confidential information of patients, ensuring security is a critical issue in the development of IoT-based healthcare system.

Aim:

Our purpose was to identify the features and concepts associated with security requirements of IoT in healthcare system.

Methods:

A survey study on security requirements of IoT in healthcare system was conducted. Four digital databases (Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed and IEEE) were searched from 2005 to September 2019. Moreover, we followed international standards and accredited guidelines containing security requirements in cyber space.

Results:

We identified two main groups of security requirements including cyber security and cyber resiliency. Cyber security requirements are divided into two parts: CIA Triad (three features) and non-CIA (seven features). Six major features for cyber resiliency requirements including reliability, safety, maintainability, survivability, performability and information security (cover CIA triad such as availability, confidentiality and integrity) were identified.

Conclusion:

Both conventional (cyber security) and novel (cyber resiliency) requirements should be taken into consideration in order to achieve the trustworthiness level in IoT-based healthcare system.

Keywords: Internet of Things, Healthcare System, Security, Requirement

1. INTRODUCTION

Internet of things (IoT) as an innovative paradigm was introduced by Kevin Ashton in 1999. This technology can connect a massive group of devices and objects to interact with each other without human intervention (1) Mobile, Analytics and Cloud. The main concept behind IoT is to emphasize the interconnection between reality and physical world via the Internet (2). IoT provides a wide range of applications such as transportation, agriculture, smart cities, emergency services and logistics for the demands of the modern life. Besides, healthcare sector is one of most attractive areas for the applications of IoT (1, 3). Remote patient monitoring, smart health, and Ambient Assisted Living (AAL), to name a few, are instances of IoT-based healthcare applications (4). The combination of IoT with medical equipment leads to the promotion of the quality of healthcare services and progress report of patient status for those who need constant and real-time medical monitoring and preventive interventions (5). IoT accelerate the early detection of diseases and support the process of diagnosis and treatment such as fitness programs, chronic diseases, and elderly care (3, 6).

With all the advantages, the application of IoT is along with the likelihood of new security attacks and vulnerabilities to healthcare systems. This is associated with the following reasons (7): (1) medical devices are mostly collecting and sharing sensitive patient data, (2) the nature of the IoT technology introduces complexity and incompatibility issues, (3) manufacturers of medical IoT devices do not pay attention to security features. Due to the aforementioned reasons, security issues related to confidentiality, integrity, and availability (CIA) are increasing.

Some of the IoT solutions in healthcare consist of the applications and devices monitoring and controlling patients’ vital signs. However, these solutions might be exposed to security risks, such as breaches of authentication, authorization and privacy (4, 7). Cyber security in healthcare domain has become a great concern. Hackers may take advantages of the weaknesses of devices and cause operational disruption to IoT system. More importantly, traditional security requirements of countermeasures for attacks are not applicable because of the constraints of medical devices including power consumption, scalability and interoperability. Therefore, medical IoT technologies should be trusted in terms of security, privacy, and reliability requirements (8). In order to prevent the data leakage of the healthcare sector, the “Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)” have provided physical and technical safeguards. However, these actions were not sufficient and stronger and newer security requirements, using resilient approach, should be applied (9, 10). Hence, there is a crucial need to identify security requirements for a better understanding and designing of a secure IoT-based healthcare architecture.

2. AIM

The purpose of this survey was to provide an overview of the features and concepts related to security requirements of IoT in a healthcare system.

3. METHODS

This study was a literature survey on IoT security requirements in healthcare system. We searched four major digital databases consisting of Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed and IEEE. Moreover, we conducted a manual search of accredited institutions containing security requirements in cyber space such as the International Organization for Standardization (ISO)/ the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC)/ and the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) 24765 (11, 12), National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) 800-160, and several popular security models and reports (13-18). The search terms included: “internet of things”, “internet of objects”, “ambient intelligence”, “ubiquitous computing”, “pervasive computing”, “heterogeneous sensor”, “cyber physical system”, “machine to machine communication”, security , cyber security, cyber resiliency, requirement, health, “healthcare”, “health care”, medical, medicine, “smart health”, “smart hospital”, e-health, and ehealth. On the basis of the research objective, inclusion and exclusion criteria were determined (Table 1).

Table 1. Inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria for selection studies.

| I/E | Criteria | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Inclusion | Language type | Studies written in English |

| Publication year | Studies published from 2005 up to September 2019 | |

| Publication venue | -Digital search in electronic databases: studies published in peer-reviewed journals, and conferences -Manual search: international standards and guidelines |

|

| Research scope | Studies related to security requirements and IoT in healthcare | |

| Exclusion | Without full-text | The full-text of the study is not accessible. |

| Non-related publication source | Publication source of the study is a book, editorial letter, commentary, short communication and poster. | |

| Wrong or non-related categorization | The study is misclassified, incomplete and unclear in terms of content and concept of security requirements. |

4. RESULTS

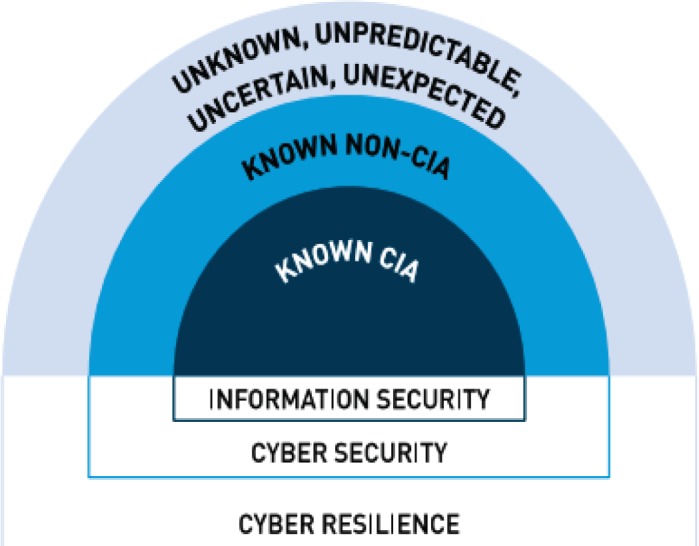

This research study identified the main features and concepts related to IoT security requirements in healthcare and summarized them as shown in Table 2 and Table 3. According to Figure 1, overall, IoT security requirements are categorized into two main groups including cyber security and cyber resiliency. More information about IoT cyber security and cyber resiliency requirements are illustrated as follows.

Table 2. Cyber security requirements for IoT-based healthcare.

| Cyber security requirements | Description | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Features | References | ||

| CIA | Confidentiality | (3, 7, 9, 19, 21-34) | Confidentiality ensures that IoT system prohibits unauthorized entities (users and devices) from disclosing medical information (19, 20). |

| Integrity | (3, 6, 7, 9, 19, 21-34, 36) | Integrity refers to data completeness and accuracy in entire lifecycle of system. Integrity ensures that patients’ medical data are not manipulated or removed or corrupted by adversary leading to mistaken diagnosis or wrong prescription (6, 35). | |

| Availability | (3, 6, 7, 9, 19, 21-25, 27-29, 31-33, 36) | Availability ensures that medical data and devices are accessible to authorized users when needed (23). It means the continuity of security services and prevention of any device failure and operational outage (37). In particular, during treatment process, when timely patients’ data should be available for physicians (6). | |

| Non-CIA | Identification and authentication | (3, 6, 9, 19, 21, 23-26, 28-33, 40) | Identification guarantees the identity of all the entities (patients, doctors, devices, etc.) before permitting them to interact with the resources of the IoT system (30). Authentication is the process of confirming the identity of a person or device before using of the system resources (23). Devices and applications authentication can prove the interacting system is not an adversary and data shared in networks are legal (38, 39). |

| Authorization (access control) | (3, 6, 9, 21, 23-26, 28-31, 33, 36, 40) | After user identity verification, access rights or privileges to resources should be determined so that different users can only access to the resources required based on their tasks (25). For example, a doctor should have more access to patient data than other health providers (40). | |

| Privacy | (3, 6, 7, 19, 21, 23, 26, 28-30, 32, 34) | Privacy means that secretes and personal data of patients should not be disclosed without the consent (6). IoT system should be in accordance with privacy policies allowing users to control their private data (35). | |

| Accountability | (22, 25, 29, 30, 34) | In health IoT system, accountability should ensure that the organization or individual are obliged to be answerable or responsible for their actions in case of theft or abnormal event (30, 35). | |

| Non-repudiation | (3, 9, 19, 21, 24-26, 29, 30) | Non-repudiation ensures that someone cannot deny an action that has already been done (3). In fact, it enables the users to prove occurrence or non-occurrence of an event (19). | |

| Auditing | (21, 23, 30, 34) | Auditing is the ability of a system to continuously track and monitor actions. In an IoT-based healthcare system, all user activities should be recorded in sequential orders such as login time to system and data modifying (21, 35). | |

| Data Freshness | (3, 6, 19, 21, 24, 30, 32, 33) | Data freshness means that data should be recent ensuring that no old messages are replayed (3). For example, doctor needs to know the current patients information about his Electrocardiography (ECG) (6). | |

Table 3. Cyber resiliency requirements for IoT-based healthcare.

| Requirements cyber resiliency | Description | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Features | References | |||

| Reliability | (29, 33, 34) | Reliability is an important aspect of the IoT network when devices are data sensing, collecting and transmitting under any high risk environmental conditions (e.g., dust, walls, win, rain, heat, etc). Therefore, reliability refers to continuity of a service correctly in spite of heterogeneous networks, system failures and various environmental conditions (15, 42). | ||

| Maintainability | Modifiability | (28, 30) | The modifiability is the ability of IoT system to update and add new capabilities or modify existing capabilities during the design and implementation of a system (16). | |

| Reparability | (28, 30) | The reparability is the ability to detect and correct the system faults, and attempt to restore the system to the normal operational state (16). | ||

| Configurability | (28, 30) | The configurability occurs when the system can adjust parameters for a set of procedures in a way that the system can function properly in different operational situations (16). | ||

| Adaptability | (28, 30) | The adaptability means the system is enabled to quickly alter and perform correct function during phases of its designing and implementing under different operating circumstances (16). | ||

| Autonomy (autonomic computing) | Self-healing | (3, 24, 28, 30) | The autonomy is that the IoT system is able to properly adapt itself under different operating conditions (16). The autonomic systems are known as self-managing systems which manage and control the processes themselves without human intervention through self-protecting, self-configuring, self-healing and self-optimizing (18, 43). More details about autonomy are defined as follows.

|

|

| Self-optimizing | ||||

| Self-protecting | ||||

| Self-configuring | ||||

| Safety | (28) | It refers to issues associated with functions and safety of devices, nodes and machines to augment safety of the entire IoT environment (45). This property ensures that the system will not fail if encountering disastrous damages during a specified period of time (17). | ||

| Survivability | (3, 19, 24, 30) | Survivability requirements guarantee that the system still protects the IoT network and completes its mission in a timely manner if some devices or nodes are compromised and data are dropped intentionally, Fault tolerance is a subset of survivability that refers to the capability of a system to withstand faults so that machines or devices work in the mode of failures, natural disasters, attacks and threats (15, 19, 30). | ||

| Performability | (24) | Performability is defined as a performance measure (such as speed, accuracy, or memory) of a system or component that performs its designated functions correctly within given constraint situations (17, 24). There are a range of acceptable values for performance attributes in any system, representing in the form of fuzzy quantity. Therefore, a metrics such as timeliness, precision, and accuracy can estimate and evaluate system performance. For instance, timeliness measures the time needed to complete the system task, especially in the real-time systems (16). | ||

Figure 1. Security requirements in cyber space (13).

Cyber security requirements

Cyber security requirements consist of a set of traditional security requirements ensuring security of patient, information, and system through two main parts: CIA Triad and non-CIA (Figure 1). Cyber security enables the users to prevent and protect IoT-based healthcare system against known threats and attacks (14). According to Table 2, CIA triad ensures the data security for IoT through confidentiality, integrity, and availability. Non-CIA is another part of cyber security requirements comprising seven main features including authentication, authorization, privacy, accountability, auditing and non-repudiation. The features and definitions related to cyber security requirements are summarized in Table 2.

Cyber resiliency requirements

Cyber resiliency (system resilience) has been addressed as complementary requirements for IoT-based healthcare system to defend against unknown, unpredictable, uncertain and unexpected threats (Figure 1). NIST standards have defined cyber resilient system as the potential to be prepared for unanticipated hazards, adapt to changing conditions, resist and recover quickly against deliberate and accidental attacks, or naturally occurring incidents (41). System resilience should ensure that a security scheme safeguards the network, device or information against any attack or destruction (19). As can be seen from Table 3, the features of cyber resiliency are divided into six main categories: reliability, maintainability, safety, survivability, performability and information security. It is worth to mention that cyber resiliency requirements overlap three cyber security aspects: availability, confidentiality and integrity (CIA traid) (Figure 1). The concepts of related to cyber resiliency requirements are illustrated in the Table 3.

5. DISCUSSION

Based on our analysis, it is noteworthy to mention that cyber security requirements are conventional requirements which only have protective and preventive tasks for healthcare IoT system, and are not responsive to most of the vulnerabilities and attacks. They may only be effective in protecting against known threats, while medical sensors and devices of IoT are embedded in uncontrolled and open environments with unknown and untrusted entities (46). Consequently, security issues and risks in healthcare systems are much more complicated than other industries. For example, patient information is extremely sensitive and confidential, and access to timely information is crucial in health care professions. (47). Due to greater capabilities, the security requirements in IoT system are shifting from cyber security approach to cyber resiliency approach which has features such as prevention, prediction, fault tolerance and autonomic computing, covering all threats and attacks either known or unknown (13, 41). As a result, security requirements with a resilient approach should be considered for the IoT-based healthcare architecture. A cyber resilient system is one aspect of the trustworthiness requirements and includes other security aspects such as security, reliability, privacy, and safety.

It is said that if IoT systems can meet both requirements of cyber resiliency and cyber security, these systems will reach the highest level of trustworthiness providing users with confident healthcare services, leading to pervasive acceptance of IoT technology. In this respect, Safavi et al. have described six significant features of cyber security requirements for IoT-based healthcare: confidentiality, authentication, integrity, authorization, availability, and non-repudiation (9). Moreover, MacDermott et al. have discussed that integrity and availability are indispensable security requirements for IoT (36). By contrast, Koutli et al. have proposed more security requirements for each layer of e-health IoT architecture including authentication, authorization, confidentiality, integrity, availability, privacy and trust management. More specifically, they have discussed the role of trust among IoT nodes which should ensure trustworthiness to detect malicious nodes in the network (23). Jaiswal et al. have considered both requirements based on cyber security and cyber resiliency, and have highlighted trustworthiness aspects for medical IoT devices (30). Almohri et al. have presented a trust model for all levels of medical IoT system including communication links, software, platform/hardware, and users (27). Mahmoud et al. have referred to IoT security concerns including privacy, confidentiality, authentication, access control, and trust management (48). Jaigirdar et al. believed that trustworthy requirements should be guaranteed in all layers of health IoT system (6). Similarly, Jaiswal et al. have remarked that trustworthiness is achieved by applying all identified security requirements (30). In fact, trustworthiness covers all security features like security, privacy, maintainability, reliability, performability, survivability, and safety (41).

A great part of cyber resiliency requirements is allocated to the features of maintainability, which suggests that, IoT system should be able to repair, modify faults, and configure in different operational situations. In this respect, Algarni et al., Islam et al., and Jaiswal et al. have highlighted the security features related to system maintainability (3, 27, 30). Besides, autonomic computing as a subset of maintainability is one of the crucial features for cyber resiliency requirements. Autonomic computing is also known as self-awareness playing an important role for self-managing activities in IoT-based healthcare systems, achieved through self-protecting, self-configuring, self-healing and self-optimizing (18). It is surprising that most of the studies regarding the IoT security in health industry have not addressed the safety aspects while safety requirements have a fundamental role in all assets of IoT system such as sensors, medical equipment and patients. However, according to NIST guideline, safety requirements protect against conditions leading to death, injury, failure or loss of equipment (41).

6. CONCLUSION

Recently, the healthcare sector has witnessed the development of a wide range of IoT devices and applications. These devices deal with vital and private information such as personal healthcare data and may be targeted by attackers. It is significant to identify the features and concepts of security requirements in healthcare IoT. In this study, we surveyed published studies on security requirements of IoT-based healthcare. The results of this study are expected to be useful for different communities such as researchers, information technology engineers, health providers, and policy makers concerned about IoT and healthcare technologies. This study makes motivation for performing furthermore research and designing a resilient IoT-based healthcare system.

Acknowledgments:

This research was a part of a Ph.D. dissertation supported by Iran University of Medical Science [Grant No: IUMS/SHMIS-1396/9321563003].

Author’s contribution:

Each author gave substantial contribution in acquisition, analysis and data interpretation. Each author had a part in preparing article for drafting and revising it critically for important intellectual content. Each author gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Conflict of interest:

There are no conflict of interest.

Financial support:

Nil

REFERENCES

- 1.Deogirikar J, Vidhate A. Security attacks in IoT: A survey; Proceeding of 2017 International Conference on I-SMAC (IoT in Social, Mobile, Analytics and Cloud) (I-SMAC). 2017 Feb 10-11; 2017; Palladam, India. IEEE; pp. 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta BB, Quamara M. An overview of Internet of Things (IoT): Architectural aspects, challenges, and protocols. Concurr Comput. 2018:e4946, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Islam SMR, Kwak D, Kabir MH, Hossain M, Kwak KS. The Internet of Things for Health Care: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Access. 2015;3:678–708. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gholamhosseini L, Sadoughi F, Ahmadi H, Safaei A. Health Internet of Things: Strengths, Weakness, Opportunity, and Threats; Proceeding of 2019 5th International Conference on Web Research (ICWR). 24-25 April 2019; 2019; Tehran, Iran. IEEE; pp. 287–296. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strielkina A, Kharchenko V, Uzun D. Availability models for healthcare IoT systems: Classification and research considering attacks on vulnerabilities; Proceeding of 2018 IEEE 9th International Conference on Dependable Systems, Services and Technologies (DESSERT). 2018 May 24-27; 2018; Kiev, Ukraine. IEEE; pp. 58–62. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaigirdar FT, Rudolph C, Bain C. Acm. Can I Trust the Data I See? A Physician’s Concern on Medical Data in IoT Health Architectures; Proceeding of Proceedings of the Australasian Computer Science Week Multiconference. 2019 Jan 29-31; 2019; Sydney, NSW, Australia. New York. Association for Computing Machinery (ACM); pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alsubaei F, Shiva S, Abuhussein A. Security and Privacy in the Internet of Medical Things: Taxonomy and Risk Assessment; Proceeding of 2017 Ieee 42nd Conference on Local Computer Networks Workshops. 2017 Oct 9; 2017; Singapore, Singapore. IEEE; pp. 112–120. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu Y, Da Xu L. Internet of Things (IoT) Cybersecurity Research: A Review of Current Research Topics. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018;6(2):2103–2115. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Safavi S, Meer AM, Melanie EKJ, Shukur Z. Cyber Vulnerabilities on Smart Healthcare, Review and Solutions; Proceeding of Proceedings of the 2018 Cyber Resilience Conference. 2019 Jan 28; 2018; Putrajaya, Malaysia. IEEE; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pacheco J, Ibarra D, Vijay A, Hariri S. IoT Security Framework for Smart Water System; Proceeding of 2017 IEEE/ACS 14th International Conference on Computer Systems and Applications (AICCSA). 2018 Mar 12; 2017; Hammamet, Tunisia. IEEE; pp. 1285–1292. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghadeer H. Cybersecurity Issues in Internet of Things and Countermeasures; Proceeding of 2018 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Internet (ICII). 2018 Oct 21-23; 2018; Seattle, Washington, United States. IEEE; pp. 195–201. [Google Scholar]

- 12.ISO/IEC/IEEE. International Standard–Systems and software engineering—Vocabulary. New York: 2017. Aug 28, pp. 1–541. Report No: ISO/IEC/IEEE 24765:2017. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geusebroek J. Cyber Risk Governance-Towards a framework for managing cyber related risks from an integrated IT governance perspective. Nederland: Utrecht University; 2012. [MSc thesis] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bodeau D, Graubart R. Cyber resiliency design principles. United States: The MITRE Corporation; 2017. Jan, pp. 1–90. Technical report, Report No: 17-0103. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zieglmeier V. Resilience Metrics. Network. 2016;9:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paul R, Dong J, Yen IL, Bastani F. Trustworthiness Assessment Framework for Net-Centric Systems. Boston, MA: Springer; 2009. pp. 19–44. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Kuwaiti M, Kyriakopoulos N, Hussein S. A comparative analysis of network dependability, fault-tolerance, reliability, security, and survivability. IEEE Commun Surv Tut. 2009;11(2):106–124. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sterritt R, Bustard D. Autonomic Computing - a means of achieving dependability?; Proceeding of 10th IEEE International Conference and Workshop on the Engineering of Computer-Based Systems. 2003 April 7-10; 2003; Huntsville, Alabama, USA. IEEE; pp. 247–251. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mekki N, Hamdi M, Aguili T, Kim TH. Scenario-based vulnerability analysis in IoT-based patient monitoring system; Proceeding of the 14th International Joint Conference on e-Business and Telecommunications. 2017 July 24-26; 2017; Madrid, Spain. pp. 554–559. [Google Scholar]

- 20.ur Rehman S, Iannella A, Gruhn V. A Security Based Reference Architecture for Cyber-Physical Systems; Proceeding of International Conference on Applied Informatics; 2018; Bogotá, Colombia. Springer, Cham; pp. 157–169. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poyner I, Sherratt RS. Proceeding of the Living in the Internet of Things: Cybersecurity of the IoT. 2018 Mar 28-29. London, UK: Institution of Engineering and Technology (IET); 2018. Privacy and security of consumer IoT devices for the pervasive monitoring of vulnerable people; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dogaru DI, Dumitrache I. Cyber security in healthcare networks; Proceeding of The 6th IEEE International Conference on E-Health and Bioengineering Conference (EHB). 2017 Jun 22-24; 2017; Sinaia, Romania. IEEE; pp. 414–417. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koutli M, Theologou N, Tryferidis A, Tzovaras D, Kagkini A, Zandes D, et al. Secure IoT e-Health Applications using VICINITY Framework and GDPR Guidelines; Proceeding of 15th International Conference on Distributed Computing in Sensor Systems (DCOSS). 2019 May 29-31; 2019; Santorini Island, Greece. IEEE; pp. 263–270. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Algarni A. A Survey Classification of Security and Privacy Research in Smart Healthcare Systems. IEEE Access. 2019;7:101879–94. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sangpetch O, Sangpetch A. Security context framework for distributed healthcare IoT platform; Proceeding of Third International Conference on Internet of Things Technologies for Health- Care. 2016 Oct 18-19; 2016; Västerås, Sweden. Springer Verlag; pp. 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rekhis S, Boudriga N, Ellouze N. Securing Implantable Medical Devices against cyberspace attacks; Proceeding of International Conference on Anti-Cyber Crimes (ICACC). 2017 Mar 26-27; 2017; Abha, Saudi Arabia. IEEE; pp. 187–192. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Almohri H, Cheng L, Yao D, Alemzadeh H. On Threat Modeling and Mitigation of Medical Cyber-Physical Systems; Proceeding of 2nd International Conference on Connected Health: Applications, Systems and Engineering Technologies, CHASE 2017. 2017 July 17-19; 2017; Philadelphia, PA, USA. IEEE; pp. 114–119. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fragopoulos A, Gialelis J, Serpanos D. Security Framework for Pervasive Healthcare Architectures Utilizing MPEG-21 IPMP Components. Int J Telemed Appl. 2009;2009:461560. doi: 10.1155/2009/461560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee JD, Yoon TS, Chung SH, Cha HS. Service-Oriented Security Framework for Remote Medical Services in the Internet of Things Environment. Healthcare informatics research. 2015 Oct;21(4):271–282. doi: 10.4258/hir.2015.21.4.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jaiswal S, Gupta D. Security Requirements for Internet of Things (IoT). Proceedings. Singapore: Springer Singapore; 2017. pp. 419–427. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benida I, Jemai A, Loukil A. A survey on security of IoT in the context of eHealth and clouds; Proceeding of Proceedings of 2016 11th International Design & Test Symposium; 2016; New York. pp. 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahmed MU, Bjorkman M, Causevic A, Fotouhi H, Linden M. An Overview on the Internet of Things for Health Monitoring Systems; Proceeding of 2nd EAI International Conference on IoT Technologies for HealthCare. 2015 Oct 26–27; 2016; Rome, Italy. Springer; pp. 429–436. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moosavi SR, Gia TN, Nigussie E, Rahmani AM, Virtanen S, Tenhunen H, et al. End-to-end security scheme for mobility enabled healthcare Internet of Things. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2016;64:108–124. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahmed A, Latif R, Latif S, Abbas H, Khan FA. Malicious insiders attack in IoT based Multi-Cloud e-Healthcare environment: A Systematic Literature Review. Multimed Tools Appl. 2018;77(17):21947–21965. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mosenia A, Jha NK. A Comprehensive Study of Security of Internet- of-Things. IEEE Trans Emerg Top Comput. 2017;5(4):586–602. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boudko S, Abie H. Adaptive Cybersecurity Framework for Healthcare Internet of Things; Proceeding of 2019 13th International Symposium on Medical Information and Communication Technology (ISMICT). 8-10 May 2019; 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Assiri A, Almagwashi H. IoT Security and Privacy Issues; Proceeding of 1st International Conference on Computer Applications and Information Security (ICCAIS). 2018 Aug 23; 2018; Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. IEEE; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin J, Yu W, Zhang N, Yang XY, Zhang HL, Zhao W. A Survey on Internet of Things: Architecture, Enabling Technologies, Security and Privacy, and Applications. IEEE Internet Things J. 2017;4(5):1125–1142. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Daud M, Khan Q, Saleem Y. A study of key technologies for IoT and associated security challenges; Proceeding of 2017 International Symposium on Wireless Systems and Networks (ISWSN). 2017 Nov 19-22; 2018; Lahore, Pakistan. IEEE; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alkeem EA, Yeun CY, Zemerly MJ. Security and privacy framework for ubiquitous healthcare IoT devices; Proceeding of 10th International Conference for Internet Technology and Secured Transactions (ICITST). 2015 Dec 14-16; 2015; London, UK. IEEE; pp. 70–75. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ross R, Graubart R, Bodeau D, McQuaid R. Systems Security Engineering: Cyber Resiliency Considerations for the Engineering of Trustworthy Secure Systems. United States: National Institute of Standards and Technology; 2018. Mar, pp. 1–142. Report No: NIST Special Publication 800-160. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muraleedharan Sreekumaridevi R. Cognitive security framework for heterogeneous sensor network using swarm intelligence. New York: Syracuse University; 2011. [PhD thesis] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pundamale SS. Survivable networks [Internet] 2007. [cited cited 2019 Apr 20]. Available from: http://www.cs.helsinki.fi/u/niklande/opetus/SemK07/paper/pundamale.pdf.

- 44.Gurgen L, Gunalp O, Benazzouz Y, Gallissot M. Self-aware cyber- physical systems and applications in smart buildings and cities; Proceedings of The Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition (DATE). 2013 Mar 18-22; 2013; Grenoble, France. IEEE; pp. 1149–1154. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Breivold HP. Internet-of-Things and Cloud Computing for Smart Industry: A Systematic Mapping Study; Proceeding of 2017 5th International Conference on Enterprise Systems (ES). 2017 Sept 22- 24; 2017; Beijing, China. IEEE; pp. 299–304. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frustaci M, Pace P, Aloi G, Fortino G. Evaluating Critical Security Issues of the IoT World: Present and Future Challenges. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018;5(4):2483–2495. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mehraeen E, Ayatollahi H, Ahmadi M. Health Information Security in Hospitals: the Application of Security Safeguards. Acta Inform Med. 2016;24(1):47–50. doi: 10.5455/aim.2016.24.47-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mahmoud R, Yousuf T, Aloul F, Zualkernan I. Internet of things (IoT) security: Current status, challenges and prospective measures; Proceeding of The 10th International Conference for Internet Technology and Secured Transactions (ICITST-2015). 2015 Dec 14-16; 2016; London, UK. IEEE; pp. 336–341. [Google Scholar]