Abstract

Introduction

Appropriate management of patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) helps preserve their independence and time at home. We explored physician behavior in the management of AD, focusing on diagnosis.

Methods

Online questionnaires and patient record forms (PRFs) were created by an independent market research agency and completed by participating physicians. Physicians were recruited from France, Germany, Japan, the UK, and the USA. A sample of 1086 physicians was recruited, including general practitioners, geriatricians, neurologists, and psychiatrists. Physicians completed an online interview and 2–3 PRFs based on randomly selected records of their patients with AD. Data on triggers and timing of diagnosis were captured. Data were assessed for all countries combined (global) and within each country and physician specialty.

Results

A total of 3346 PRFs were submitted. Approximately half of patients received diagnosis within 6 months. There were large country differences. In France, only 35% of patients were diagnosed within 6 months compared to 65% in Japan. Physicians in France also reported diagnoses taking > 9 months for a substantial number of patients (39%) compared with other countries (16–29%). Caregivers were the main driver toward diagnosis. Physician suspicion of AD was a trigger for diagnosis in only 20% of cases, globally. Overall, referral rates were low (14–23%).

Conclusion

This study suggests that detection and timely diagnosis of AD remains suboptimal. This highlights the importance of fostering awareness of early symptoms and education on the benefits of timely diagnosis, a critical step in initiating treatment as early as possible.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Patient record forms, Physician’s management, Timely diagnosis

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Increasing life expectancy is leading to a rise in the elderly population worldwide, which is enhancing the prevalence of neurodegenerative diseases, such as dementia. |

| Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia and one of the main aims of clinical management of this patient population is to maintain good quality of life by preserving patient independence and time at home. |

| The aim of this study was to investigate the clinical management of AD today by providing an up-to-date picture of real-world, self-reported physician behavior focusing on the diagnosis of AD across five countries (France, Germany, Japan, UK and the USA). |

| What were the study outcomes/conclusions? |

| This study showed that approximately half of patients (n = 3346) received a diagnosis within 6 months. There were large differences between countries; in France, 35% of patients were diagnosed within 6 months compared to 65% in Japan. Caregivers were the main driver toward diagnosis. Physician suspicion of AD was a trigger for diagnosis in only 20% of cases, globally (i.e. across all participating countries). |

| What we learned from this study |

| The study showed that the process of diagnosing AD remains suboptimal, even in more developed counties, with a significant number of patients remaining undiagnosed for several months after initially presenting to a physician. |

| Future initiatives to improve diagnosis timelines such as tailored physician educational activities, public awareness campaigns and execution of the updated national dementia strategies are urgently needed. |

Introduction

Rising life expectancy is contributing to a rapid increase in the number of people over 60 years of age worldwide [1]. This in turn is driving the increased prevalence of neurodegenerative diseases such as dementia [1]. In 2015, the number of people worldwide living with dementia was estimated to be 46.8 million; this number is expected to double every 20 years, to a forecast of over 130 million people in 2050, according to the 2015 World Alzheimer Report [1].

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive and debilitating neurological disorder and the most common cause of dementia [2]. The implications of the disorder are both psychosocial [3] and economic [4]. The global societal economic cost of dementia was estimated to be US$818 billion in 2015, a 35% increase from the cost estimate for 2010, which was $604 billion [1]. Projecting forwards, it is estimated that this will have reached US$2 trillion by 2030 [1]. Around half of this increase in cost is due to the rise in the numbers of people with dementia and the other half is due to increases in per capita costs [1].

One of the main goals of dementia management is to keep patients in their own homes for as long as possible [5] , while preserving their independence and ensuring that the levels of assistance required from caregivers remain minimal for as long as possible [6]. This goal serves to maintain patient quality of life and reduce the emotional and financial burdens on caregivers [7–9]. The burden to caregivers can be substantial given their indirect loss of productivity [8], as well the emotional and psychological impact of caring for a patient with AD [9]. Moreover, daily care as a result of nursing home placement, which is often considered by families in the later stages of the disease, escalates cost for the society [10]. Delaying institutionalization is therefore a key aspect in AD management.

Cognitive capabilities are crucial for the daily functioning of patients with AD [11]; thus, timely diagnosis and initiation of AD-specific treatment can be of benefit in this regard [12]. With disease progression, competencies essential for daily functioning decline and cannot be restored [13]. Moreover, the presence of underlying risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and a history of myocardial infarction can also contribute to the pathogenesis of neurodegeneration, and the development of frailty, in patients with AD [14]. The initiation of AD-specific treatment (such as donepezil or memantine) when the disease has substantially progressed may not lead to a considerable improvement with regards to daily functioning. Furthermore, the effectiveness of such treatments is generally modest, although previous literature has suggested that they have the greatest benefit when initiated early in the course of the disease [8, 12, 15]. Timely identification and treatment of AD has also been reported to result in significant cost savings [4, 16].

The aim of this study was to explore physicians’ behavior in the management of AD today, focusing on diagnosis and treatment. The first part of this report provides an up-to-date picture of real-world physician behavior in the diagnosis of AD specifically (not including other types of dementia), as reported by physicians themselves, across five countries (France, Germany, Japan, the UK, and the USA) that have similar treatment guidelines for AD. The primary objective of part one was to provide a description of the physician’s approach to the diagnosis of AD in each of the five participating countries. Part two will focus on the treatment of AD.

Methods

All aspects of the research were performed by the independent primary market research agency, GfK. Because the study was based on market research data and non-interventional, it was not necessary to register it in a clinical trial database.

Physician Interviews

Participating physicians were identified and screened from global research networks of healthcare professionals, according to the predefined selection criteria below. Eligible physicians were required to have been board certified for at least 3 years at the time of study initiation, spend at least 75% of their working time on patient care (vs. administrative tasks) and see > 200 (specialists)/> 350 [general practitioners (GPs)] patients per month, of whom at least 35 (specialists)/15 (GPs) have a diagnosis of AD.

After physician questionnaires for online interviews and patient record forms (PRFs) were prepared, face-to-face pilot interviews were conducted in the UK in order to confirm the language and clarity of the questionnaire. Questionnaires and PRFs were then translated into study country languages and quality control checks were performed to confirm the accuracy of the translations. Physicians from an online panel were approached via email and were asked to indicate their consent to participate. If the physicians agreed to participate, they were checked for eligibility, using a screening questionnaire, before being directed to the online interview questions. The online interviews, which took 60–75 min to complete, were conducted with GPs, neurologists, geriatricians, and psychiatrists in France, Germany, Japan, the UK, and the USA. The data collected from the questionnaires during the online interviews were based on the physician’s recollection. Each physician was asked to complete 2–3 PRFs, using data transcribed from their patient record database. The patient records used to complete the PRFs were selected at random. Individual data were captured from patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI)/prodromal AD or mild or moderate AD, as assessed by physician judgment. Participating physicians were compensated for their time.

The first part of our publication reports physician demographics and practice details, involvement in diagnosis, triggers and timing for diagnosis, and tools used to confirm diagnosis.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The survey followed national and international guidelines for the conduct of non-interventional studies. It adhered to globally accepted guidelines for the code of conduct on market research and pharmaceutical market research from the European Society for Opinion and Marketing Research [17], the European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association [18], and the Council of American Survey Research Organizations [19]. Because this was a non-interventional, market research study, approval by an institutional review board was not necessary. Survey responses were anonymized to preserve patient confidentiality and to avoid bias during the data collection and analysis phases.

Data Analysis

Data analyses were performed (1) for all countries combined (hereafter referred to as global data), (2) for each individual participating country, and (3) for each physician specialty, wherever possible. For the purpose of this study, no within-country analyses were conducted.

Data were collected, stored and analyzed at GfK. The analysis was performed using IBM SPSS statistics.

Results

Participating Physicians and their Patients

A total of 1086 physicians (428 GPs, 356 neurologists, 151 geriatricians, and 151 psychiatrists) were interviewed and 3346 PRFs were submitted. The participating physicians were predominantly male (76%), working in a practice (solo practice: 24%; single-specialty group practice: 18%; multi-disciplinary group practice: 23%; center for geriatric care: 3%; and hospital: 32%) within large urban centers (46%) or suburbs (33%). They had been board certified for a mean of 17 years at the time of study initiation. Overall, the majority of physicians were the current key medical point of contact for their patients with AD and caregivers (85%). In the event of disease progression, for the majority of patients, the physicians remained the key point of medical contact (GPs, 55%; geriatricians, 62%; psychiatrists, 69%; neurologists, 73%) over the course of the disease.

As detailed in Table 1, physicians reported that they each saw on average 398 patients per month. Of these patients, 69 (17%) had AD. The highest number of patients seen per month per physician was in Germany (446) and the lowest in the UK (336).

Table 1.

Number of patients and patients with AD seen by physicians each month, per country and specialty

| Total number of all patients/number of patients with AD (%) seen each month | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All specialties | GPs | Geriatricians | Neurologists | Psychiatrists | |

| Global | 398/69 (17) | 506/49 (10) | 348/90 (26) | 327/81 (25) | 309/76 (25) |

| USA | 403/86 (21) | 457/55 (12) | 435/111 (26) | 338/107 (32) | 399/76 (19) |

| Japan | 407/65 (16) | 516/47 (9) | 536/101 (19) | 361/66 (18) | 312/79 (25) |

| Germany | 446/63 (14) | 549/45 (8) | 327/65 (20) | 393/79 (20) | 353/85 (24) |

| France | 394/61 (15) | 546/45 (8) | 325/113 (35) | 265/62 (23) | 275/41 (15) |

| UK | 336/63 (19) | 472/50 (11) | 225/64 (28) | 254/73 (29) | 212/85 (40) |

Data are presented as means and percentages

AD Alzheimer’s disease, GPs general practitioners

As anticipated, there were country-specific differences in the number of patients with AD seen by various specialties (Table 1). While a large portion of patients with AD (35%) were seen by geriatricians in France, 40% of patients with AD were seen by psychiatrists in the UK.

The largest portion of patients presenting to physicians were in the mild to moderate stage of AD (GPs, 59%; geriatricians, 59%; psychiatrists, 62%; neurologists, 63%).

AD Diagnosis

Globally, physicians reported that they diagnosed 66% of their patients with AD themselves. However, some differences were observed on a country-specific level; physician survey data showed that Japanese physicians (across all specialties) were involved in the initial diagnosis of 75% of their patients, compared to only 54% of cases for physicians in the UK. Split by specialty, GPs, geriatricians, neurologists, and psychiatrists were involved in AD diagnosis in 59%, 61%, 75%, and 68% of cases globally, respectively.

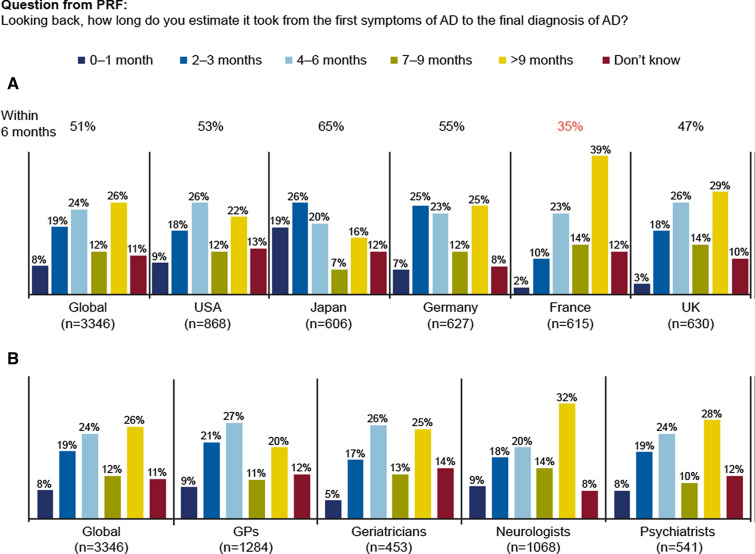

Analysis of the PRF data showed that globally, approximately half of patients (51%) were diagnosed within 6 months of presenting with first symptoms. As depicted in Fig. 1a, there were large country-specific differences. In Japan, 45% of patients were diagnosed within 3 months and 65% within 6 months of presenting with symptoms. In Germany, the USA, and the UK, approximately half of patients were diagnosed within 6 months after presenting with symptoms to physicians (55%, 53% and 47%, respectively). Only 12% patients were diagnosed within 3 months and 35% within 6 months in France. The percentage of patients with diagnosis taking more than 9 months was highest in France (39%) and lowest in Japan (16%). Split by specialty, longer time to diagnosis was reported more often by neurologists (32% of patients) than by other specialties (20–28% of patients) (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

The time from first symptoms of AD until diagnosis, globally and by country (a) and by specialty (b) (n = 3346). AD Alzheimer’s disease, GPs general practitioners, n number of PRFs, PRF patient record form (data transcribed from the physician’s patient record database)

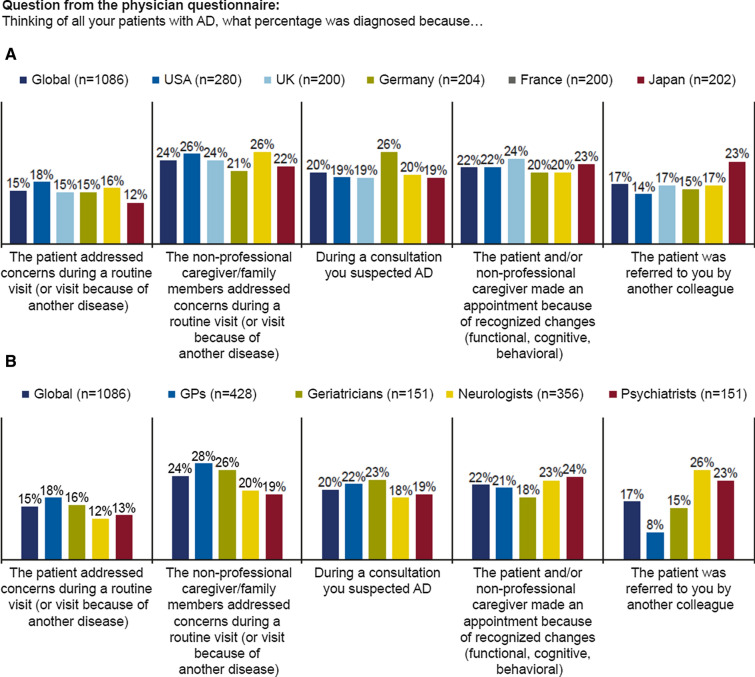

Concerns raised by the patient’s non-professional caregiver/family member, either during a routine visit (24%) or during a visit requested because of a recognized change (22%) were the most common triggers leading to AD diagnosis (Fig. 2a). Globally, physician’s suspicion of AD during a consultation triggered the diagnostic process in only 20% of cases. On a country-specific level, physician suspicion of AD was reported most frequently in Germany (26%). In Japan, physicians reported that a sizeable percentage of patients were referred to them by another colleague (23%), whereas referral was relatively low in other participating countries (14–17%). There was a substantial difference by specialty in the proportion of patients referred by another colleague, with 26% of neurologists and only 8% of GPs reporting this as a trigger for AD diagnosis (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Reasons that lead to AD diagnosis, globally and by country (a) and by specialty (b) (N = 1086). AD Alzheimer’s disease, GPs general practitioners, n number of physicians

On average, the most frequently stated tool used to confirm AD was the Mini Mental State Examination (48% of physicians). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI, 29%) and routine test/blood work/laboratory tests (13%) were also reportedly used to confirm diagnosis. It was found that only 10% of physicians reported that input from caregivers or family members provided an important source of data confirming AD diagnosis.

Diagnostic tool preference differed among countries and specialties. For example, 25% of physicians in France reported using the neuropsychiatric inventory, compared with 1–9% of physicians in other countries. Japanese physicians favored the Hasegawa Dementia Scale (58%). MRI is more commonly used by neurologists (53%), compared with other specialties (16–21%). Similarly, neurologists reported using the neuropsychiatric inventory more frequently (21%) than other specialties (2–7%).

Discussion

Alzheimer’s disease is a growing public health concern associated with both psychosocial and economic burden. Timely detection and diagnosis of AD allows for early initiation of treatment, before functional competencies of patients are significantly deteriorated by cognitive decline, therefore enhancing the quality of life of the patients and their caregivers [4, 8, 16, 20]. Additionally, patients who are diagnosed in the mild stages of AD may be better able to take part in the future planning of their affairs alongside their families or caregivers [8]. The main goal of AD management is keeping patients in their home setting for as long as possible, therefore timely diagnosis and initiation of AD-specific treatment is crucial.

It is recognized that the insidious onset of AD makes diagnosis difficult. Indeed, disease is frequently unrecognized or diagnosed late in its course [21–23], as initial symptoms may not become apparent during routine examination [24]. Another area of delay is the time taken to reach AD diagnosis after first contact with a physician [25] and has previously been reported to take 12 months or more [26]. Results of the present study, from over 1000 physicians, extend these findings, as it was observed that a substantial proportion of patients still do not receive AD diagnosis until many months after presenting to a physician. Findings from France were particularly striking, with a high proportion of patients waiting more than 9 months to receive an AD diagnosis. It is acknowledged that the accurate diagnosis of AD is a step-wise process that requires time. However, a 9-month delay in diagnosis results in lost opportunities for the patient and their family when therapy could have been initiated. In addition, such a delay in diagnosis does not reflect best healthcare practice.

Concerns raised by the patient’s non-professional caregiver or family member were the most common trigger for diagnosis in this study, which is consistent with previous studies [27, 28]. Surprisingly, suspicion of the physician, based on clinical signs and symptoms displayed by the patient, initiated the diagnostic process in only a fraction of cases. Some symptoms of AD, such as forgetfulness, can be quite common among the older adult population and therefore it can be difficult to differentiate between normal age-related change and AD. Findings from a survey of 1480 caregivers of patients diagnosed with AD [29] suggest that not only caregivers but also physicians may lack an understanding of the differences between memory processes in aging and AD [29]. Indeed, a survey of physicians across Europe revealed that GPs as well as specialists have difficulty identifying early symptoms, which consequently impacts the time taken to reach a diagnosis [23].

Limitations of this study include the potential ambiguity of the questionnaire data, as it was based on the physician’s recollection. Similarly, as the PRFs were completed by the physician and were not checked for accuracy by another expert, there could also be a risk of selection bias in the completion of the forms. In addition, the sample of patients with AD in this study may not be representative of the wider patient population. The data pertaining to diagnosis tools used by physicians must also be treated with caution as this was an open-ended question: there may have been physicians who did not use any of the tools listed. The disease stages (e.g., mild, moderate) used in clinical research and in the PRFs used in this study are not definitive terms recognized in clinical practice, and thus were estimated by the physician. Data analysis was therefore performed for all stages of the disease combined. Furthermore, as the focus of this study was on AD, specifically not including other types of dementia, further investigation regarding these subtypes is something that may be considered for future work.

One potential confounding factor in this study is the different healthcare systems within each of the participating countries. Although each of the five countries is considered to be well developed and the treatment guidelines are similar across each country, our survey observed large country-specific differences. For example, in Japan, almost half of patients with AD were diagnosed within 3 months of presenting with symptoms. However, in Germany, the USA, and the UK, time to diagnosis was longer, with approximately half of patients being diagnosed within 6 months; this proportion was even lower in France. This is in line with previous work by Wilkinson et al., who reported delays in the diagnosis of AD in European countries, particularly the UK [23]. The authors of this study speculated that in the UK this may be due to a belief among physicians that referrals for specialist care should only be given to patients with acute or serious disease, with the aim of protecting resources [23]. Indeed, there are many extrinsic factors that may determine whether a patient’s AD is considered to be serious, such as the level of concern raised by the caregiver. It has also been suggested that European countries are restricted in terms of accessibility to diagnostic tests and a lack of government funding in resources for patients with dementia [24]. This may help to explain the variation in the preference for diagnostic tools across the different countries in the current study.

Another point to consider regarding healthcare systems in each participating country is the influence of insurance programs versus government-run systems. In this study, the time taken to reach a diagnosis was notably longer in the European countries, where healthcare is largely funded by the government. The delay in diagnosis of AD in these countries may therefore be partly due to financial constraints. This may also be a factor in the USA, where the majority of patients with AD are likely to be under the federal health insurance program known as Medicare. Non-financial factors may also be influencing the delay in diagnosis. A previous study conducted in California reported several barriers to care in patients with dementia, some of which included insufficient time for the patient–physician consultation, low reimbursement, difficulty in accessing and communicating with specialists, and lack of interdisciplinary teams [30]. In Japan, where patients are required to accept responsibility for a fraction of their healthcare costs and the government funds the rest, the delay in AD diagnosis was shorter than in the other countries. The shorter time to diagnosis could suggest that physicians in Japan more often work as part of interdisciplinary teams than physicians in the other countries, which means that they are able to reach a diagnosis earlier. A finding from our study in support of this was that Japanese physicians (across all specialties) were involved in the initial diagnosis of three-quarters of their patients, whereas in the UK approximately only half of physicians were involved.

Our survey showed that the process of diagnosing AD remains suboptimal even in more developed countries. It was found that a significant proportion of patients remained undiagnosed for a considerable number of months after presenting to a physician. Benefits of timely diagnosis have been recognized [24, 26, 31], as plans for the future can be made while the patient is still able and timely initiation of AD-specific treatment can help to delay cognitive deterioration and a potential decline into frailty [14], and improve daily functioning of the patient, while reducing caregiver burden. These aspects are critical in helping to keep patients at home for as long as possible, which is the main goal of AD management.

Conclusions

To overcome barriers to timely diagnosis, tailored physician educational activities, public awareness campaigns and execution of the updated national dementia guidelines and strategies [32, 33] are urgently needed. A number of new and ongoing initiatives that aim to improve diagnosis timelines are underway [34–36]. Although the impact of these initiatives remains to be demonstrated, increased awareness among physicians and the general public on the benefits of timely diagnosis and initiation of the AD-specific treatment should give hope to patients and their families and ultimately improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants of the study.

Funding

This survey and the journal’s Rapid Service and Open Access fees were funded by Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH.

Medical Writing and/or Editorial Assistance

Writing, editorial support, and formatting assistance were provided by Lisa Auker, Ph.D., of Fishawack Communications Ltd., funded by Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH. The sponsor was given the opportunity to review the manuscript for medical and scientific accuracy as well as intellectual property considerations.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship Contributions

JP, NW, HZ, TP and SW all provided substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work as well as the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. All authors have contributed towards the preparation of the manuscript, have approved the final submitted version, and agreed to be listed as authors.

Disclosures

Hartmut Zoebelein, Nadine Winter, and Jana Podhorna are full employees of Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH, but received no direct compensation related to the development of this manuscript. Susann Walda is a current employee of GfK and Thomas Perkins was an employee of GfK at the time of the study, but neither author received direct compensation related to the development of this manuscript. The current affiliation for Thomas Perkins is Pennside Partners, Ltd., Wyomissing, PA, USA.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The survey followed national and international guidelines for the conduct of non-interventional studies. It adhered to globally accepted guidelines for the code of conduct on market research and pharmaceutical market research from the European Society for Opinion and Marketing Research [17] (https://www.esomar.org/uploads/public/knowledge-and-standards/codes-and-guidelines/ICCESOMAR_Code_English_.pdf), the European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association [18] (http://www.ephmra.org/code-of-conduct/11/B-What-Constitutes-Market-Research), and the Council of American Survey Research Organizations [19] (http://www.insightsassociation.org/sites/default/files/misc_files/casro_code_of_standards.pdf). Physicians were asked to indicate their consent to participate prior to starting the online questionnaire. The patient record forms chosen by physicians were kept anonymous, in accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996.

Data Availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from GfK upon request.

Footnotes

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.11396601.

References

- 1.Alzheimer’s Disease International: World Alzheimer Report 2015: The global impact of dementia, an analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends 2015. http://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2015.pdf. Accessed Dec 2019.

- 2.Alzheimer's Association Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimer's Dement. 2016;12(4):459–509. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haupt M, Kurz A, Janner M. A 2-year follow-up of behavioural and psychological symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2000;11(3):147–152. doi: 10.1159/000017228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geldmacher DS, Kirson NY, Birnbaum HG, Eapen S, Kantor E, Cummings AK, et al. Implications of early treatment among Medicaid patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2014;10(2):214–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spijker A, Vernooij-Dassen M, Vasse E, Adang E, Wollersheim H, Grol R, et al. Effectiveness of nonpharmacological interventions in delaying the institutionalization of patients with dementia: a meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(6):1116–1128. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Institutes of Health and Clinical Excellence. Dementia: supporting people with dementia and their carers in health and social care. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg42. Accessed Dec 2019.

- 7.Jones RW, Romeo R, Trigg R, Knapp M, Sato A, King D, et al. Dependence in Alzheimer’s disease and service use costs, quality of life, and caregiver burden: the DADE study. Alzheimer's Dement. 2015;11(3):280–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leifer BP. Early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: clinical and economic benefits. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(5 Suppl Dementia):S281–S288. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.5153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stefanacci RG. The costs of Alzheimer’s disease and the value of effective therapies. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(Suppl 13):S356–S362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hurd MD, Martorell P, Delavande A, Mullen KJ, Langa KM. Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(14):1326–1334. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1204629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atchison TB, Massman PJ, Doody RS. Baseline cognitive function predicts rate of decline in basic-care abilities of individuals with dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2007;22(1):99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geldmacher DS. Treatment guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease: redefining perceptions in primary care. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;9(2):113–121. doi: 10.4088/PCC.v09n0205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zidan M, Arcoverde C, Araújo NBD, Vasques P, Rios A, Laks J, et al. Motor and functional changes in different stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Clin Psychiatry. 2012;39:161–165. doi: 10.1590/S0101-60832012000500003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koch G, Belli L, Giudice TL, Lorenzo FD, Sancesario GM, Sorge R, et al. Frailty among Alzheimer’s disease patients. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2013;12(4):507–511. doi: 10.2174/1871527311312040010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wattmo C, Minthon L, Wallin ÅK. Mild versus moderate stages of Alzheimer’s disease: three-year outcomes in a routine clinical setting of cholinesterase inhibitor therapy. Alzheimer’s Res Ther. 2016;8:7. doi: 10.1186/s13195-016-0174-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weimer DL, Sager MA. Early identification and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: social and fiscal outcomes. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2009;5(3):215–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2009.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.ICC/ESOMAR International code on market, opinion and social research and data analytics 2016. https://www.esomar.org/uploads/public/knowledge-and-standards/codes-and-guidelines/ICCESOMAR_Code_English_.pdf. Accessed Dec 2019.

- 18.European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association: Code of conduct 2017. https://www.ephmra.org/media/1785/ephmra-2017-code-of-conduct-october-2017.pdf. Accessed Dec 2019.

- 19.Council of American Survey Research Organizations (CASRO): Code of standards and ethics for market, opinion, and social research 2013. http://www.insightsassociation.org/sites/default/files/misc_files/casro_code_of_standards.pdf. Accessed Dec 2019.

- 20.World Alzheimer Report 2016. https://www.alz.co.uk/research/world-report-2016. Accessed Dec 2019.

- 21.Magsi H, Malloy T. Underrecognition of cognitive impairment in assisted living facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(2):295–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van den Dungen P, Van Marwijk HW, van der Horst HE, Moll van charante EP, Macneil Vroomen J, van de PM, et al. The accuracy of family physicians’ dementia diagnoses at different stages of dementia: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;27(4):342–354. doi: 10.1002/gps.2726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilkinson D, Sganga A, Stave C, O’Connell B. Implications of the facing dementia survey for health care professionals across Europe. Int J Clin Pract Suppl. 2005;146:27–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-504X.2005.00484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bradford A, Kunik ME, Schulz P, Williams SP, Singh H. Missed and delayed diagnosis of dementia in primary care: prevalence and contributing factors. Alzheimer’s Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23(4):306–314. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181a6bebc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chrisp TA, Tabberer S, Thomas BD, Goddard WA. Dementia early diagnosis: triggers, supports and constraints affecting the decision to engage with the health care system. Aging Ment Health. 2012;16(5):559–565. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2011.651794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Speechly CM, Bridges-Webb C, Passmore E. The pathway to dementia diagnosis. Med J Aust. 2008;189(9):487–489. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb02140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brayne C, Fox C, Boustani M. Dementia screening in primary care: is it time? JAMA. 2007;298(20):2409–2411. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.20.2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu CW, Sano M. Economic considerations in the management of Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Interv Aging. 2006;1(2):143–154. doi: 10.2147/ciia.2006.1.2.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knopman D, Donohue JA, Gutterman EM. Patterns of care in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease: impediments to timely diagnosis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(3):300–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb02650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hinton L, Franz CE, Reddy G, Flores Y, Kravitz RL, Barker JC. Practice constraints, behavioral problems, and dementia care: primary care physicians’ perspectives. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(11):1487–1492. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0317-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robinson L, Tang E, Taylor J-P. Dementia: timely diagnosis and early intervention. BMJ. 2015;350:h3029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.National Dementia Strategies (diagnosis, treatment and research): country comparisons 2012. http://www.alzheimer-europe.org/Policy-in-Practice2/Country-comparisons/2012-National-Dementia-Strategies-diagnosis-treatment-and-research. Accessed Dec 2019.

- 33.NICE guideline: Dementia: assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers 2018. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng97. Accessed Dec 2019. [PubMed]

- 34.Brooker D, La Fontaine J, Evans S, Bray J, Saad K. Public health guidance to facilitate timely diagnosis of dementia: ALzheimer’s COoperative Valuation in Europe recommendations. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;29(7):682–693. doi: 10.1002/gps.4066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prorok JC, Stolee P, Cooke M, McAiney CA, Lee L. Evaluation of a dementia education program for family medicine residents. Can Geriatr J. 2015;18(2):57–64. doi: 10.5770/cgj.18.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilcock J, Iliffe S, Griffin M, Jain P, Thune-Boyle I, Lefford F, et al. Tailored educational intervention for primary care to improve the management of dementia: the EVIDEM-ED cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:397. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from GfK upon request.