Abstract

Objective

Timely initiation of Alzheimer’s disease (AD)-specific treatment may postpone cognitive deterioration and preserve patient independence. We explored real-world physician behavior in the treatment of AD.

Methods

Online questionnaires and patient record forms (PRFs) were completed by participating physicians. The physicians included general practitioners, neurologists, geriatricians and psychiatrists, recruited from France, Germany, Japan, the UK and the USA. Physicians completed an online interview and two to three PRFs based on selected records of their patients with AD. Data on treatment algorithms and key drivers for therapy were captured.

Results

A total of 3346 PRFs were submitted and 1086 physicians interviewed. Overall, 44% of patients with mild cognitive impairment/prodromal AD, 71% of patients with mild disease and 76% of patients with moderate disease had already received therapy. The most common reasons for not prescribing therapy were patient refusal (35%) and early disease stage (26%). Except in the USA, the majority of physicians preferred to prescribe monotherapy. Almost 30% of patients at any stage of the disease did not receive AD-specific pharmacotherapy immediately after diagnosis.

Conclusions

Physicians’ attitudes toward AD treatment could be driven by limited awareness regarding the benefits of early intervention and the modest efficacy of currently available therapies. Efficacious therapies for AD, especially early AD, which could be used alone or in combination with current medications to maximize treatment benefit, are still needed. The availability of more efficacious therapies may improve time to treatment initiation, treatment rates and acceptance of treatment by patients, caregivers and physicians.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Survey, Physician’s management, Treatment

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Timely diagnosis and treatment of patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD)-specific medications (i.e., donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine or memantine) are important to preserve cognitive capabilities that are required for the daily functioning of patients with AD |

| The aim of this study was to investigate the behavior of physicians in the treatment of AD, with emphasis on treatment algorithms (including time to treatment initiation) and key drivers for drug therapy |

| What were the study outcomes/conclusions? |

| This study found that the most common reasons for not prescribing therapy were patient refusal and early disease stage. Except for physicians in the USA, the majority of physicians preferred to prescribe monotherapy. Almost a third of patients at any stage of the disease did not receive AD-specific pharmacotherapy immediately after diagnosis |

| What was learned from the study? |

| This real-world survey suggests that some aspects of AD treatment can be improved |

| There are patients with AD who do not receive any AD-specific pharmacotherapy, even at the moderate stage of the disease |

| Combination therapy to maximize treatment benefit is not widely adopted, despite its recommendation in the international treatment guidelines |

| Findings highlight an unmet medical need for a new, effective medication for symptomatic relief from the first manifestation of clinical symptoms of AD |

Introduction

The implications of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), a progressive and debilitating neurologic disorder, are both psychosocial [1] and economic [2] with global societal economic cost of dementia predicted to increase to USA $2 trillion by 2030 [3]. Thus, the primary objective of AD management is minimizing the level of support required from caregivers [4] in addition to keeping patients in their home setting for as long as possible [5]. Indeed, this serves to maintain patient quality of life and reduce the emotional and financial burdens on caregivers as well as reduce cost associated with nursing home placement [6–10].

Timely diagnosis and treatment of patients with AD-specific medications (i.e., donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine or memantine) are important [4] to preserve cognitive capabilities that are required for the daily functioning of patients with AD [11]. Consideration of comorbidities, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus and a history of myocardial infarction, is also important, because these can contribute to the pathogenesis of neurodegeneration, and the development of frailty, in patients with AD [12]. Part 1 of our report focused on physicians’ behavior in diagnosing AD, specifically the triggers and timing of AD diagnosis [13]. However, timely initiation of AD-specific treatment is also crucial for maintaining patient independence [14]. With disease progression and cognitive decline, competencies essential for daily functioning diminish and may become difficult to restore [15]. However, the efficacy of pharmacologic treatments was reported to be modest for patients with mild-to-moderate AD [16] and inconsistent in patients presenting in the early stages of the disease (i.e., mild cognitive impairment [MCI]/prodromal AD), for which there are currently no licensed treatments [17]. As a result, the misconception that little can be done for patients with AD, especially at the early stages of the disease, sometimes persists [18]. Part 2 of the report therefore focuses on the behavior of physicians in the treatment of AD, with emphasis on treatment algorithms (including time to treatment initiation) and key drivers for drug therapy.

Methods

All aspects of the research were performed by the independent primary market research agency, GfK. Because the study was non-interventional and based on market research data, clinical trial database registration was not necessary.

Physician Interviews

As described in Part 1 of our report [13], physicians from an online panel were approached via email and were asked to indicate their consent to participate in the study. If the physicians agreed to participate they were then screened according to the predefined selection criteria. Physicians who were eligible for inclusion had to have been board certified for at least 3 years at the start of the study, spend at least 75% of their working time on patient care and see > 200 (specialists)/> 350 (general practitioners [GPs]) patients per month, of whom at least 35 (specialists)/15 (GPs) have a diagnosis of AD.

The methods for the collection and analysis of physician questionnaires and patient record forms (PRFs) have been previously described in Part 1 [13]. Briefly, online interviews were conducted with GPs, neurologists, geriatricians and psychiatrists in France, Germany, Japan, the UK and the USA. In addition, participating physicians were asked to complete two to three PRFs, using data transcribed from their patient record database. Physicians were instructed to start with surname letters H, M or K and select the first patient with a diagnosis of MCI/prodromal AD, mild or moderate AD. Data were not collected on patients with severe AD (although physicians may still have treated patients with severe AD).

The following information, captured from the questionnaire data, is included in this part of our report: physician demographics and practice details; the types of patient treatments (including AD-specific pharmacologic and non-AD specific pharmacologic treatments and non-pharmacologic therapy) prescribed by physicians; physician familiarity with each of the AD-specific treatment options; physician preference for prescribing monotherapy or combination therapy and the reasons behind this; factors that influence the physician’s treatment decision; the physicians’ attitude toward treatment of AD compared with other psychiatric disorders.

The data collected from PRFs included details of disease management and treatment algorithms (including treatment approaches, time to initiation of AD-specific pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic treatments, reasons for their patients not receiving pharmacologic treatment and key drivers for drug therapy). AD-specific pharmacologic treatments included acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs) donepezil, galantamine and rivastigmine, and the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist, memantine. The administration of concomitant therapies, for example, administration of an AD-specific pharmacologic treatment (such as donepezil, rivastigmine, memantine or galantamine) along with a non-pharmacologic therapy (such as cognitive training, rehabilitation, speech therapy or music therapy) or an AD-specific pharmacologic treatment with a concomitant non-AD specific pharmacologic treatment (such as an anti-psychotic, anti-depressant or anti-anxiety agent), was also captured.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The work presented in this report followed national and international guidelines for the conduct of non-interventional studies. The survey conducted complied with globally accepted guidelines for the code of conduct of market research and pharmaceutical market research from the European Society for Opinion and Marketing Research [19], the European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association [20] and the Council of American Survey Research Organizations [21]. Approval by an institutional review board was not necessary for this non-interventional, market research study. Survey responses were anonymized to preserve patient confidentiality and to avoid bias during the data collection and analysis phases.

Data Analysis

Data analyses were performed (1) for all countries combined (hereafter referred to as global data), (2) within each participating country and (3) by physician specialty, wherever possible. Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics.

Results

Participating Physicians and Their Patients

A detailed description of participating physicians was provided in Part 1 of our report [13]. Briefly, 1086 physicians, including 428 GPs, 356 neurologists, 151 geriatricians and 151 psychiatrists, were interviewed, and 3346 PRFs were submitted. Overall, 76% of the physicians who took part in this study were male, practicing within large urban centers (46%) or suburbs (33%). Participating physicians had been board certified for a mean of 17 years at the time of the survey.

The majority of physicians (70%) reported that they were the current key medical point of contact for patients and caregivers. A proportion of physicians also indicated that they would remain the key contact in the event of disease progression (GPs: 33%; neurologists: 36%; geriatricians: 13%; psychiatrists: 18%). Participating physicians indicated that they saw approximately 398 patients on a monthly basis, 69 (17%) of which had AD. Physicians in the USA reported seeing the highest number of patients with AD per month (86) and those in France reported seeing the lowest (61).

On average, physicians treated 41 patients per month in the mild to moderate stages of the disease, with a further 15 patients with MCI/prodromal AD. A similar distribution was observed across all participating countries (Table 1). Across all physician specialties, the highest frequency of patients with MCI/prodromal AD was seen by geriatric specialists (18%) and the lowest by GPs and psychiatry physicians (12%).

Table 1.

Physician estimation of the number of patients with MCI/prodromal, mild and moderate AD they treat per month

| Number of patients in the MCI/prodromal, mild, and moderate stages of AD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPs | Geriatricians | Neurologists | Psychiatrists | ||

| USA | MCI | 14 | 23 | 23 | 17 |

| Mild AD | 16 | 30 | 33 | 24 | |

| Moderate AD | 15 | 33 | 30 | 23 | |

| Japan | MCI | 10 | 17 | 10 | 10 |

| Mild AD | 15 | 28 | 24 | 22 | |

| Moderate AD | 14 | 34 | 19 | 26 | |

| Germany | MCI | 11 | 17 | 15 | 11 |

| Mild AD | 14 | 19 | 23 | 25 | |

| Moderate AD | 11 | 19 | 24 | 28 | |

| France | MCI | 12 | 22 | 14 | 9 |

| Mild AD | 13 | 29 | 19 | 10 | |

| Moderate AD | 11 | 33 | 17 | 11 | |

| UK | MCI | 13 | 11 | 16 | 15 |

| Mild AD | 14 | 17 | 23 | 25 | |

| Moderate AD | 13 | 22 | 22 | 26 | |

Data are presented per specialty for each of the participating countries: the USA, Japan, Germany, France and the UK

AD Alzheimer’s disease, GPs general practitioners, MCI mild cognitive impairment

AD Treatment

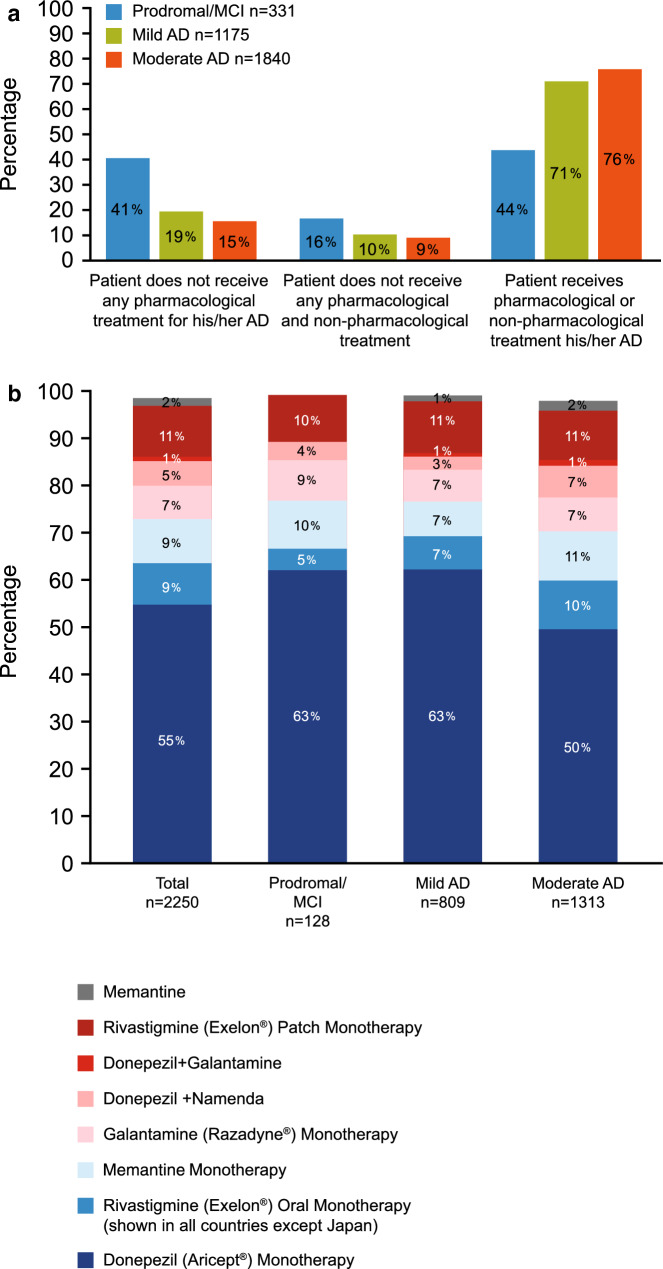

Globally, AD-specific pharmacotherapy was the predominant treatment option, even in patients with MCI/prodromal AD; with 44% of patients with MCI/prodromal AD, 71% of patients with mild disease and 76% of patients with moderate disease receiving any AD-specific pharmacologic treatment (Fig. 1a). This study also showed that 19% of patients with mild AD and 15% of patients with moderate AD dementia received no form of treatment (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Types of treatment prescribed to patients with AD (a) and the global first-line AD-specific treatments for patients (b) per disease stage. AD Alzheimer’s disease, MCI mild cognitive impairment

The most commonly cited reasons for not prescribing any AD-specific pharmacologic treatment were patient refusal (35% of patients) and early disease stage (26%). Contrary to the latter, however, many physicians reported that they felt AD-specific pharmacologic treatments are most efficacious in the early stages of the disease (Germany: 58%; USA: 51%; France: 50%; UK: 38%; Japan: 34%). Globally, PRF data indicated that for 13% of patients, physicians did not prescribe medication because they did not believe treatments were efficacious.

When questioned about the likelihood to prescribe AD-specific pharmacologic treatment, there were no meaningful differences between physician specialties. However, differences were seen on a country-specific level; in Japan, 83% of patients received AD-specific pharmacologic treatment compared with 76% in the USA, 73% in Germany and the UK, and 69% in France.

The most commonly prescribed first-line therapy across all stages of the AD disease was donepezil, either as monotherapy or in combination with other treatments (Fig. 1b). Country differences were observed, with use of donepezil being highest in the UK (71%) and lowest in France (34%). On the other hand, French physicians reported prescribing rivastigmine more frequently than other countries. Across physician specialties, the use of donepezil as a first-line therapy was similar: GPs: 59%; geriatricians: 57%; psychiatrists: 53%; neurologists: 52%.

Physician treatment goals at the time of this study varied according to the disease stage. Improvement of cognition was cited as the overarching treatment goal for 39% of patients with mild AD and 33% of patients with MCI/prodromal AD. Maintenance of independence was also more important to physicians when treating patients in the early stages of AD (MCI/prodromal AD: 32%; mild AD: 29%). Improvement of functional impairment to be able to perform daily activities was seen as an important treatment goal for patients with mild (37%) and moderate AD (35%). For patients in the moderate stages of AD, treatment of behavioral impairments became an important treatment goal for physicians (33%).

Based on questionnaire responses, the factors considered by physicians as most important when making the decision to prescribe treatments included patient behavioral disturbances, such as aggression and isolation (62%), patient cognitive status (60%), stage of disease (59%), ability of the patient to perform activities of daily living (functional status; 59%) and availability of caregiver support (59%). On a country-specific level, patient ability to perform activities of daily living was considered the most important attribute by 73% and 63% of physicians in Germany and the UK, respectively. In the USA, behavioral disturbances such as aggression and isolation were considered the most important attribute for prescribing treatment (65%), whereas in France it was the stage of disease (63%). In Japan, the most important attribute was caregiver’s input (68%).

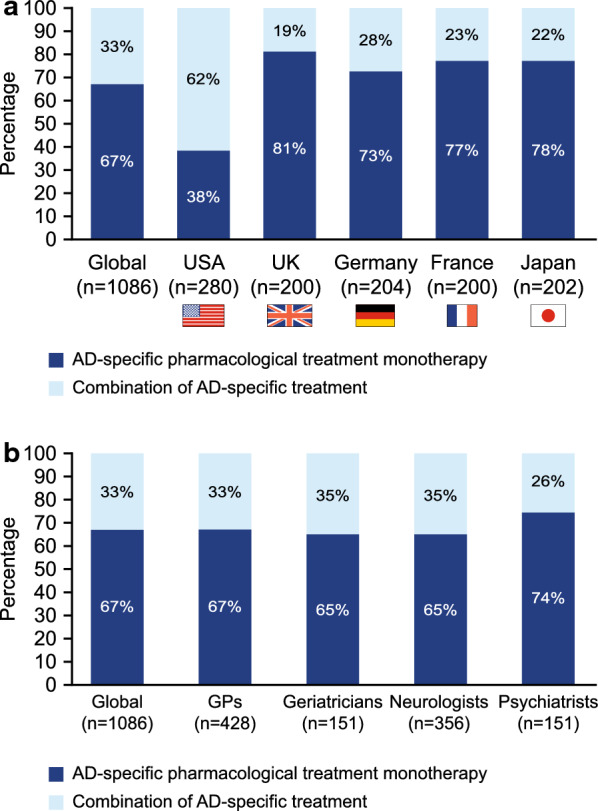

With the exception of the US physicians, the majority of physicians from other countries preferred to prescribe monotherapy rather than combination therapy (Fig. 2a). The preference for monotherapy was particularly high in the UK (81%), followed by Japan (78%), France (77%) and Germany (73%). In contrast, only 38% of physicians in the USA indicated a preference for monotherapy (Fig. 2a). Physicians in the USA reported having the highest proportion of patients with moderate AD (mean n = 24) compared with physicians in Japan (n = 20), Germany (n = 18), the UK (n = 19) and France (n = 17). When data from all countries were combined, a preference for prescribing monotherapy prevailed (psychiatrists: 74%; GPs: 67%; geriatricians and neurologists: 65%) over combination therapy, defined as the combination of AD-specific pharmacologic treatment (psychiatrists: 26%; GPs: 33%; neurologists: 35%; and geriatricians: 35%; Fig. 2b), regardless of specialty.

Fig. 2.

Monotherapy versus combination therapy preferences of physicians per country (a) and specialty (b). AD Alzheimer’s disease, GPs general practitioners

The physician questionnaire asked participants to describe their criteria for favoring monotherapy in an open-ended manner. The five most frequently cited reasons were that they are well tolerated (29%), have good efficacy/result/control (14%), good patient adherence to treatment (9%), avoidance of pill burden/polypharmacy (8%) and ease of monitoring (8%). The five most common reasons for some physicians favoring combination therapy were: good efficacy/result/control (29%), combination/synergistic effect (24%), differing mechanisms of action (13%) and better symptom control (7%).

Overall, treatment compliance was reported to be high; according to the PRFs, physicians reported that up to 66% of their patients have high or very high compliance to their treatment regimens. Physician questionnaires also revealed that only 39% of physicians actively and frequently monitor their patients to assess if AD-specific pharmacologic treatment is successful. Across specialties, 49% of geriatricians and 42% of neurologists monitor their patients’ response to treatment compared with 36% of GPs and 34% of psychiatrists.

Physicians across all specialties considered the management of AD less important than the treatment of other psychiatric conditions, particularly physicians in the USA and Japan (Table 2).

Table 2.

Percentage of physicians who consider the management of AD important* compared with other psychiatric conditions

| GPs | Geriatricians | Neurologists | Psychiatrists | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | 31 | 38 | 35 | 43 |

| Japan | 26 | 40 | 33 | 38 |

| Germany | 17 | 20 | 25 | 0 |

| France | 22 | 10 | 19 | 7 |

| UK | 24 | 31 | 33 | 37 |

*Data show % of responses rated 6 or 7 on a scale ranging from 1 (least important) to 7 (most important)

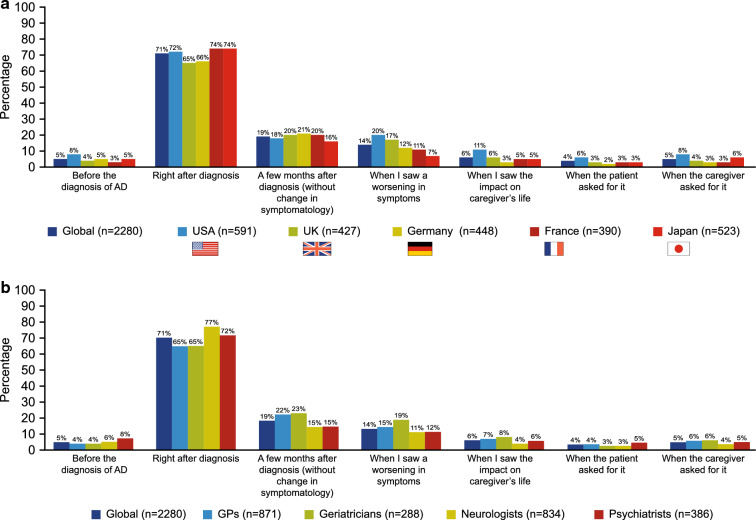

Factors Influencing Initiation of AD Treatment

Globally, physicians did not consider AD-specific pharmacologic treatment immediately following diagnosis in more than a quarter of patients (29%) (Fig. 3a), regardless of the stage of disease (MCI/prodromal AD: 29%; mild AD: 27%; moderate AD: 31%). Additionally, 22%, 16% and 20% of patients with MCI/prodromal AD, mild AD and moderate AD, respectively, did not receive AD-specific pharmacologic treatment until several months after diagnosis. Country differences were not pronounced, with 35% of physicians in the UK not considering treatment immediately after diagnosis compared with 26% in both France and Japan. Across specialties, more GPs and geriatricians did not consider AD-specific pharmacologic treatment immediately following diagnosis (35% of patient cases) than neurologists and psychiatrists (23% and 28% of cases, respectively; Fig. 3b). Non-pharmacologic treatment was also not considered in 70% of patients with AD, globally. Similar results were observed on a country-specific level (USA: 65%; France: 69%; Germany: 70%; UK: 71%; Japan: 76%).

Fig. 3.

Time point for initiating AD-specific pharmacologic treatment reported by physicians per country (a) and physician specialty (b). AD Alzheimer’s disease, GPs general practitioners, PRF patient record form. The data presented here are based on the PRF data for only those patients who received AD-specific pharmacologic treatment (n = 2280). Physicians were able to select more than one answer for this question

Discussion

Given that one of the main goals of AD management is maintaining patients’ independence and keeping them in their home setting for as long as possible, timely diagnosis and initiation of AD-specific treatment are vital. By initiating treatment early, cognitive decline is postponed and functional competencies can be preserved, subsequently improving the quality of life of both the patients and their caregivers [2, 22–24].

Our real-world survey showed that not only does the timely detection and diagnosis of AD remain suboptimal [13], but there are also some aspects of AD treatment that could be improved. It is widely acknowledged that AD is a significant public health issue [3]; however, as previously reported by Wilkinson et al. in 2005 [18], AD is often not considered a healthcare priority. A decade later, our survey reports similar findings regarding physician attitudes towards the management of AD. About one-third of physicians, and even fewer in France and Germany, considered the management of patients with AD important compared with that of other psychiatric conditions.

Based on PRFs, about two-thirds of patients with mild and moderate AD receive specific treatment for their AD (either pharmacologic or non-pharmacologic). However, there are still patients with AD who do not receive any AD-specific pharmacotherapy, even at the moderate stage. The reasons that physicians reported for not prescribing any AD-specific treatment included patient refusal of therapy and a lack of belief that treatments are efficacious. Indeed, the efficacy and effectiveness of currently approved medications are modest [16]. This may improve with the introduction of more effective drug treatments in the future.

Current pharmacologic treatment options for AD include the AChEIs, such as donepezil for mild-to-severe AD, rivastigmine and galantamine for mild-to-moderate AD and the NMDA receptor antagonist, memantine, for moderate and severe AD [25, 26]. There is a lack of evidence for the efficacy of memantine in mild AD, despite its frequent off-label use [27]. Our survey showed that only 14% of physicians indicated that they perceive monotherapy as having good efficacy. Regardless, combination therapy to maximize treatment benefit is not widely adopted, despite its recommendation in the international treatment guidelines [28]. This disparity may be driven by inconsistent results from randomized clinical trials and lack of treatment options for a combination approach; currently, only one pharmacologic class is available to treat mild AD [29–31]. Effective medication for use in combination with AChEIs to maximize benefit in patients with mild AD is desperately lacking.

The second most common reason specified for not prescribing treatment globally was early disease stage. As there is no pharmacologic treatment approved for MCI/prodromal AD, a reason for not prescribing medication could be that patients were in this early stage of the disease. On the other hand, almost half of patients with MCI/prodromal AD do receive some form of AD-specific therapy. This may suggest that there is a need to provide symptomatic relief to patients at early stages of AD, despite the fact that there is no approved pharmacotherapy for these patients [17]. These findings highlight an unmet medical need for a new, effective medication for symptomatic relief from the first manifestation of clinical symptoms of AD.

Our survey showed that 65–74% of physicians considered prescribing AD-specific treatment immediately after diagnosis. A previous survey of healthcare professionals across Europe reported similar findings [32]. Initiation of treatment was delayed in a proportion of patients, including those with mild and moderate AD. However, reasons for delay were not collected per disease stage, which may be important in determining specific barriers to treatment initiation.

Limitations of this study include the potential ambiguity of the questionnaire data, as questionnaires were based on the physicians’ recollection. Furthermore, the PRFs were completed by the physician and were not checked for accuracy by an independent party. There could also be a risk of selection bias in the completion of the forms (physicians were instructed to complete the PRFs by selecting patients with surname letters H, M or K and to select the first patient with a diagnosis of MCI/prodromal AD, mild or moderate AD). The sample of patients with AD in this study may not be representative of the wider patient population as patients with severe AD were not included in the scope of this study. Another limitation of this study is that not all data are available per disease severity.

As acknowledged in the World Alzheimer Report in 2016, early identification of AD followed by a prompt initiation of AD-specific pharmacotherapy is beneficial to both the patient and the caregiver, as well as having a positive socioeconomic impact [2, 22, 23]. It is therefore expected that patients should receive an AD diagnosis within a reasonable time frame, followed by prompt initiation of AD-specific treatment. Indeed, previous work has shown that the initiation of therapy in the early stages of AD can help to maintain activities of daily living functions for a longer period of time [33]. The results of the present study, however, demonstrate that there are still areas for improvement in both the diagnosis and management of AD.

Conclusions

Diagnosis may improve with increased awareness or perhaps if a simple diagnostic tool was to become available. To increase the number and timing of treatment prescriptions, as well as acceptance of treatment by physicians, patients and their caregivers, a more efficacious treatment may provide one solution. The development of a medication that provides symptomatic relief from the first clinical symptoms of AD, either a monotherapy or one that can be used in combination with currently available therapies, is therefore vital.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participants of the study, and also thank Susann Walda and Cristina Constantinescu, who were employed by GfK Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland) at the time of the study (current affiliation is Ipsos, Basel, Switzerland), for their contributions.

Funding

This survey and the journal’s Rapid Service and Open Access fees were funded by Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH.

Medical Writing and/or Editorial Assistance

Writing, editorial support and formatting assistance were provided by Lisa Auker, PhD, of Fishawack Communications Ltd., funded by Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH. The sponsor was given the opportunity to review the manuscript for medical and scientific accuracy as well as intellectual property considerations.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship Contribution

Jana Podhorna, Nadine Winter, Hartmut Zoebelein and Thomas Perkins all provided substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work as well as the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. All authors have contributed towards the preparation of the manuscript, have approved the final submitted version and agreed to be listed as authors.

Disclosures

The authors met the criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Hartmut Zoebelein, Nadine Winter and Jana Podhorna are full employees of Boehringer Ingelheim International, but received no direct compensation related to the development of this manuscript. Thomas Perkins was an employee of GfK at the time of the study, but received no direct compensation related to the development of this manuscript. The current affiliation for Thomas Perkins is: Pennside Partners, Ltd., Wyomissing, PA, USA.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The survey followed national and international guidelines for the conduct of non-interventional studies. It adhered to globally accepted guidelines for the code of conduct on market research and pharmaceutical market research from the European Society for Opinion and Marketing Research [16] (https://www.esomar.org/uploads/public/knowledge-and-standards/codes-and-guidelines/ICCESOMAR_Code_English_.pdf), the European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association [17] (http://www.ephmra.org/code-of-conduct/11/B-What-Constitutes-Market-Research) and the Council of American Survey Research Organizations [18] (http://www.insightsassociation.org/sites/default/files/misc_files/casro_code_of_standards.pdf). Physicians were asked to indicate their consent to participate prior to starting the online questionnaire. The patient record forms chosen by physicians were kept anonymous, in accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996.

Data Availability

The data sets used and analyzed during the current study are available from GfK upon request.

Footnotes

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.11396808.

References

- 1.Haupt M, Kurz A, Janner M. A 2-year follow-up of behavioural and psychological symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2000;11(3):147–152. doi: 10.1159/000017228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geldmacher DS, Kirson NY, Birnbaum HG, Eapen S, Kantor E, Cummings AK, et al. Implications of early treatment among Medicaid patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2014;10(2):214–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alzheimer’s Disease International. World Alzheimer Report 2015: The Global Impact of Dementia, An analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends 2015. http://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2015.pdf. Accessed Dec 2019.

- 4.National Institutes of Health and Clinical Excellence. Dementia: supporting people with dementia and their carers in health and social care. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg42. Accessed Dec 2019.

- 5.Spijker A, Vernooij-Dassen M, Vasse E, Adang E, Wollersheim H, Grol R, et al. Effectiveness of nonpharmacological interventions in delaying the institutionalization of patients with dementia: a meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(6):1116–1128. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stefanacci RG. The costs of Alzheimer’s disease and the value of effective therapies. Am J Managed Care. 2011;17(Suppl 13):S356–S362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feldman HVBB, Kavanagh S, Torfs K. Cognition, function, and caregiving time patterns in patients with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer disease: a 12-month analysis. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2005;19:29–36. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000157065.43282.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gustavsson A, Jonsson L, Parmler J, Andreasen N, Wattmo C, Wallin AK, et al. Disease progression and costs of care in Alzheimer’s disease patients treated with donepezil: a longitudinal naturalistic cohort. Eur J Health Econ. 2012;13(5):561–568. doi: 10.1007/s10198-011-0334-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones RW, Romeo R, Trigg R, Knapp M, Sato A, King D, et al. Dependence in Alzheimer’s disease and service use costs, quality of life, and caregiver burden: the DADE study. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2015;11(3):280–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michaud TL, High R, Charlton ME, Murman DL. Dependence stage and pharmacoeconomic outcomes in patients with Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer’s Dis Assoc Disord. 2017;31(3):209–217. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atchison TB, Massman PJ, Doody RS. Baseline cognitive function predicts rate of decline in basic-care abilities of individuals with dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2007;22(1):99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koch G, Belli L, Giudice TL, Lorenzo FD, Sancesario GM, Sorge R, et al. Frailty among Alzheimer’s disease patients. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2013;12(4):507–511. doi: 10.2174/1871527311312040010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Podhorna J, Winter N, Zoebelein H, Perkins T, Walda S. Alzheimer’s diagnosis: real-world physician behavior across countries. Adv Ther. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s12325-019-01212-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geldmacher DS. Treatment guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease: redefining perceptions in primary care. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;9(2):113–121. doi: 10.4088/PCC.v09n0205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zidan M, Arcoverde C, Araújo NBd, Vasques P, Rios A, Laks J, et al. Motor and functional changes in different stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Clin Psychiatry. 2012;39:161–165. doi: 10.1590/S0101-60832012000500003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raina P, Santaguida P, Ismaila A, Patterson C, Cowan D, Levine M, et al. Effectiveness of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for treating dementia: evidence review for a clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(5):379–397. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-5-200803040-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper C, Li R, Lyketsos C, Livingston G. Treatment for mild cognitive impairment: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;203(3):255–264. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.127811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilkinson D. Is there a double standard when it comes to dementia care? Int J Clin Pract Suppl. 2005;146:3–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-504X.2005.00479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.ICC/ESOMAR International Code on Market, Opinion and Social Research and Data Analytics 2016. https://www.esomar.org/uploads/public/knowledge-and-standards/codes-and-guidelines/ICCESOMAR_Code_English_.pdf. Accessed Dec 2019.

- 20.European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association: Code of conduct 2017. https://www.ephmra.org/media/1785/ephmra-2017-code-of-conduct-october-2017.pdf. Accessed Dec 2019.

- 21.Council of American Survey Research Organizations (CASRO): Code of standards and ethics for market, opinion, and social research 2013. http://www.insightsassociation.org/sites/default/files/misc_files/casro_code_of_standards.pdf. Accessed Dec 2019.

- 22.Weimer DL, Sager MA. Early identification and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: social and fiscal outcomes. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2009;5(3):215–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2009.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alzheimer’s Disease International. World Alzheimer Report 2016. https://www.alz.co.uk/research/world-report-2016. Accessed Dec 2019.

- 24.Leifer BP. Early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: clinical and economic benefits. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(5 Suppl Dementia):S281–S288. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.5153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.NAMENDA (memantine HCl): Prescribing information. Irvine, CA: Allergan; 2016. http://www.allergan.com/assets/pdf/namenda_pi. Accessed Dec 2019.

- 26.Ebixa (memantine hydrochloride): Summary of product characteristics Copenhagen, Denmark: Lundbeck; 2012. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000463/WC500058763.pdf. Accessed Dec 2019.

- 27.Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Higgins JP, McShane R. Lack of evidence for the efficacy of memantine in mild Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(8):991–998. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ihl R, Frolich L, Winblad B, Schneider L, Burns A, Moller HJ. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the biological treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2011;12(1):2–32. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2010.538083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tariot PN, Farlow MR, Grossberg GT, Graham SM, McDonald S, Gergel I. Memantine treatment in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer disease already receiving donepezil: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291(3):317–324. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.3.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Howard R, McShane R, Lindesay J, Ritchie C, Baldwin A, Barber R, et al. Donepezil and memantine for moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s disease. New Engl J Med. 2012;366(10):893–903. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lopez OL, Becker JT, Wahed AS, Saxton J, Sweet RA, Wolk DA, et al. Long-term effects of the concomitant use of memantine with cholinesterase inhibition in Alzheimer disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80(6):600–607. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.158964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilkinson D, Sganga A, Stave C, O’Connell B. Implications of the facing dementia survey for health care professionals across Europe. Int J Clin Pract Suppl. 2005;146:27–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-504X.2005.00484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hallikainen I, Hanninen T, Fraunberg M, Hongisto K, Valimaki T, Hiltunen A, et al. Progression of Alzheimer’s disease during a three-year follow-up using the CERAD-NB total score: Kuopio ALSOVA study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25(8):1335–1344. doi: 10.1017/S1041610213000653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used and analyzed during the current study are available from GfK upon request.