Abstract

Introduction

Diquafosol is a P2Y2 receptor agonist that has been shown to be effective in the treatment of dry eye disease (DED) in short-term studies; however, its long-term safety and effectiveness have not been evaluated in a real-world setting.

Methods

This prospective, multicentre, open-label observational study was conducted in patients with DED over 12 months. Safety endpoints included the incidence of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and serious ADRs. Effectiveness endpoints included change from baseline in keratoconjunctival staining score, tear film break-up time (BUT) and Dry Eye-related Quality of Life Score (DEQS).

Results

A total of 580 patients were included, most of whom were female (82.9%). The proportion of patients who completed 12 months of observation was 55.0%, the most common reason for discontinuation was patient decision (54.6%). The incidence of ADRs was 10.7% and was highest during the first month of treatment (5.5%); no serious ADRs were reported. Compared with baseline, significant improvements in all effectiveness outcomes, including keratoconjunctival fluorescein staining score, BUT and DEQS summary score, were observed at each evaluation during the treatment period (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

The present, real-world study showed that diquafosol 3.0% ophthalmic solution was well tolerated and effective in the long-term treatment of DED.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12325-019-01188-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Break-up time, Diquafosol, Dry eye, Fluorescein staining, Ophthalmology, Post-marketing study, Safety

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Diquafosol is a P2Y2 receptor agonist that is approved for the treatment of dry eye disease (DED) in Japan. |

| Short-term treatment with diquafosol was effective and safe in a prospective, observational, post-marketing study. |

| Objective findings do not always correlate with subjective symptoms in patients with DED, and determining the treatment effects based on subjective symptoms in a real-world setting may be of great clinical significance. |

| The aim of this study was to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of long-term diquafosol in the real-world setting, including the effect on Dry Eye-related Quality of Life Score (DEQS). |

| What was learned from the study? |

| During the 12-month observational period, the incidence of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) was 10.7% without any serious ADRs, and significant improvements in keratoconjunctival fluorescein staining score, tear film break-up time and DEQS were observed. |

| Patient-reported outcomes such as DEQS represent better criteria for evaluating the effectiveness of DED therapies than objective parameters. |

| Long-term diquafosol treatment is safe and effective. |

Introduction

Dry eye disease (DED) is a common ocular condition. In the USA, the prevalence of DED among adults has been estimated at 6.8% [1]. In Japan, 11.6% of office workers have been diagnosed with definite DED and 54.0% with probable DED [2].

The definition of DED has evolved over time [3]. In 2017, the Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society (TFOS) International Dry Eye Workshop (DEWS) II and the Asia Dry Eye Society (ADES) proposed similar definitions, both of which defined DED as a multifactorial disease characterised by tear film instability and accompanied by ocular symptoms [4, 5]. In the latest edition of the Japanese dry eye definition and diagnostic criteria (2016), dry eye was defined as a disease with the following criteria: (1) subjective symptoms such as ocular discomfort and abnormal visual function and (2) tear film break-up time (BUT) of 5 s or less [6]. This differs from the definition in the former diagnostic criteria (2006), in which DED is diagnosed on the basis of the presence of keratoconjunctival epithelial disorder and abnormal tear function assessed by the Schirmer’s test I and/or BUT [7].

In many patients with DED, the severity of ocular symptoms does not appear to correlate with clinical findings [8, 9]. Therefore, several questionnaires have been developed that aim to provide objective and standardised assessment of patient-reported outcomes in DED, including the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI), Dry Eye Questionnaire-5 (DEQ-5) and Dry Eye-related Quality of Life Score (DEQS) [10].

Diquafosol is a uridine 5′-triphopsphate (UTP) derivative and potent P2Y2 receptor agonist. P2Y2 receptors are found on palpebral and bulbar conjunctival epithelium cells, and on corneal epithelium and Meibomian gland cells, where they are involved in the regulation of aqueous fluid and mucin secretion. By stimulating P2Y2 receptors, diquafosol promotes tear film stabilisation which may help in improving symptoms, since tear film instability is closely correlated with subjective symptom severity [11]. In a randomised, double-blind, phase III clinical trial conducted in 287 adult patients with DED over 4 weeks, diquafosol 3.0% ophthalmic solution was non-inferior to sodium hyaluronate 0.1% ophthalmic solution, improving the mean corneal fluorescein staining score and BUT, and was significantly more effective in improving the keratoconjunctival rose bengal staining score [12]. Diquafosol 3.0% ophthalmic solution was approved for the treatment of DED in Japan in 2010, followed by subsequent approval in several other countries including South Korea, Thailand, Vietnam and China [13].

In a prospective, observational, post-marketing study conducted in 3196 patients with DED over 2 months, treatment with diquafosol 3.0% ophthalmic solution was effective and well tolerated [14], but long-term experience with this agent in a real-world clinical practice population is limited. The current study (also a post-marketing study) was therefore undertaken to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of diquafosol in patients with DED over a longer period of 1 year.

Methods

Study Design

This prospective, multicentre, open-label, observational study was conducted upon request from the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency of Japan, which reviewed and approved the study protocol prior to initiation. The duration of the observational period was 12 months. According to Japanese regulations, post-marketing studies do not require approval of the ethics committees at individual study sites or patients’ informed consent. Verbal consent was obtained from all patients, with the option of also obtaining written consent. The study was conducted in accordance with the Good Post-marketing Study Practice regulations (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare ordinance no. 171, 20 December 2004).

Participants

Patients with DED who had not used diquafosol previously and who underwent fluorescein staining of the cornea and conjunctiva, and completed the DEQS questionnaire, were eligible for inclusion. DED diagnosis was established if a patient met both of the following criteria: (1) DEQS ≥ 1 in at least one of the ocular symptoms and (2) BUT ≤ 5 s. Once verbal consent was obtained from the patient, anonymised patient information was recorded in a central database.

Outcome Measurement

Safety outcomes evaluated in this study included adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and serious ADRs. An ADR was defined as an adverse event for which causal relationship to study treatment could not be denied. ADRs were classified according to the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities Japanese edition (MedDRA/J) version 19.1.

Effectiveness outcomes included mean fluorescein staining score, BUT and DEQS summary score. Fluorescein staining was evaluated in three areas (cornea, temporal conjunctiva and nasal conjunctiva), with each area graded on a four-point scale, where 0 indicates no staining and 3 indicates staining in the entire section. BUT was defined as the time between a patient opening his or her eyes and the appearance of a dark spot in the tear film [12, 14]. The DEQS questionnaire contains six questions about ocular symptoms and nine questions about their effect on the quality of life, making a total of 15 questions. For each question, respondents are first asked to rate how often they experience a symptom on a five-point scale, where 0 indicates never, 1 indicates occasionally, 2 sometimes, 3 often and 4 indicates always. Those who select any answer other than 0 are asked to rate how much the symptom bothers him or her on a four-point scale, where 1 indicates “hardly bothers” and 4 indicates “bothers very much” [15]. The scores for individual items are used to generate an overall summary score, and two multi-item subscale scores measuring impact on daily life (based on the nine questions about daily life) and bothersome ocular symptoms (based on the six questions about ocular symptoms) [15].

Effectiveness outcomes were evaluated at baseline and every 3 months thereafter (at 0, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months).

Statistical Analysis

For qualitative variables, proportions of patients affected were calculated, while for quantitative variables, mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated, and paired t test was used to determine the p values. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Japan), with a two-sided significance level of 5%.

Results

Patients

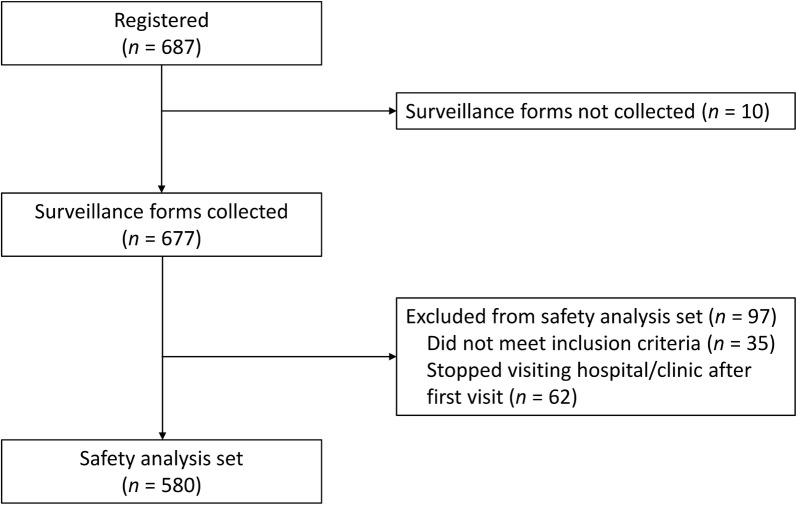

A total of 580 patients with DED were included in this study. Patient flow is shown in Fig. 1. Most patients were female (82.9%); patients aged 70–79 years comprised the largest age category (Table 1). Most patients (63.1%) were treatment-naïve and received diquafosol as monotherapy.

Fig. 1.

Patient flow diagram

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics

| Characteristic, n (%) | n = 580 |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 99 (17.1) |

| Female | 481 (82.9) |

| Age (years) | |

| < 20 | 0 (0.0) |

| 20–29 | 21 (3.6) |

| 30–39 | 42 (7.2) |

| 40–49 | 59 (10.2) |

| 50–59 | 73 (12.6) |

| 60–69 | 137 (23.6) |

| 70–79 | 188 (32.4) |

| ≥ 80 | 60 (10.3) |

| BUT (s)a | |

| ≤ 2 | 249 (43.5) |

| 3–5 | 299 (52.2) |

| > 5 | 25 (4.4) |

| Keratoconjunctival fluorescein staining scorea | |

| 0 | 116 (20.2) |

| 1–2 | 164 (28.5) |

| 3–5 | 249 (43.3) |

| 6–9 | 46 (8.0) |

| Dry eye disease according to the 2006 criteria [7] | |

| Definitive | 272 (49.7) |

| Suspected (1)b | 250 (45.7) |

| Suspected (2)c | 7 (1.3) |

| Suspected (3)d | 1 (0.2) |

| Did not meet criteria | 17 (3.1) |

| Unknown | 33 |

| Dry eye disease according to the 2016 criteria [6] | |

| Definitive | 522 (95.4) |

| Not meet criteria | 25 (4.6) |

| Unknown | 33 |

| Concurrent disease | |

| Allergic conjunctivitis | 97 (16.7) |

| Conjunctivochalasis | 35 (6.0) |

| Sjögren’s syndrome | 46 (8.4) |

| Meibomian grand dysfunction | 33 (5.7) |

| Contact lens wearers | 39 (6.7) |

| Therapeutic pattern | |

| Treatment-naïve, monotherapy | 301 (63.1) |

| Add-on to sodium hyaluronate | 58 (10.0) |

| Switch from sodium hyaluronate | 44 (7.6) |

| Treatment-naïve, combination therapy with sodium hyaluronate | 61 (10.5) |

BUT tear film break-up time

aPatients with missing data excluded: BUT (n = 7), fluorescein staining score (n = 5)

bSuspected (1): defined as positive for subjective symptoms and abnormal tear fluid, but not for corneal and conjunctival epithelium disorder

cSuspected (2): defined as positive for subjective symptoms and corneal and conjunctival epithelium disorder, but not for abnormal tear fluid

dSuspected (3): defined as positive for abnormal tear fluid and corneal and conjunctival epithelium disorder, but not for subjective symptoms

Treatment Administration and Follow-Up

The most common frequency of administration was six times per day (69.5%), followed by four times per day (24.7%; Table 2). The mean duration of the treatment was 264.0 days (SD 147.8; range 3–712). Overall, 55% (95% confidence interval CI 50.9%–59.0%) of patients completed the 12-month observation period, as estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. Reasons for discontinuation before 12 months were patients did not attend follow-up visits (54.6%), development of adverse events (15.2%), improvement of symptoms (14.5%) and experienced insufficient effectiveness (10.8%; Table 2).

Table 2.

Status of administration

| Status of administration, n (%) | n = 580 |

|---|---|

| Frequency of administration of diquafosol at the beginning of treatment (times per day) | |

| 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 1 (0.2) |

| 3 | 20 (3.4) |

| 4 | 143 (24.7) |

| 5 | 12 (2.1) |

| 6 | 403 (69.5) |

| Discontinued or terminated treatment, n (%) | 269 (46.4) |

| Due to symptom improvement | 39 (14.5) |

| Due to insufficient effectiveness | 29 (10.8) |

| Due to AEs | 41 (15.2) |

| Stopped visiting hospital/clinic | 147 (54.6) |

| Other reasons | 13 (4.8) |

AE adverse event

Safety

In the present study, ADRs occurred in 62 patients (10.7%). ADRs that occurred in three or more patients are summarised in Table 3. None of the ADRs were serious.

Table 3.

Adverse drug reactions

| ADRs, n (%)a | n = 580 |

|---|---|

| Any ADR | 62 (10.7) |

| ADRs in ≥ 3 patients | |

| Eye discharge | 17 (2.9) |

| Eye irritation | 14 (2.4) |

| Eye pruritus | 6 (1.0) |

| Eye pain | 6 (1.0) |

| Conjunctivitis | 5 (0.9) |

| Lacrimation increased | 5 (0.9) |

| Foreign body sensation | 5 (0.9) |

| Blepharitis | 3 (0.5) |

| Allergic conjunctivitis | 3 (0.5) |

ADR adverse drug reaction

aADRs were classified according to the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities Japanese edition (MedDRA/J) version 19.1

The incidence of ADRs was highest in the period between day 1 and 30 from the start of treatment (5.5%), followed by day 31–60 (1.3%). After day 61, the incidence of ADRs was less than 1.0% during all subsequent 30-day periods until the end of treatment.

Effectiveness

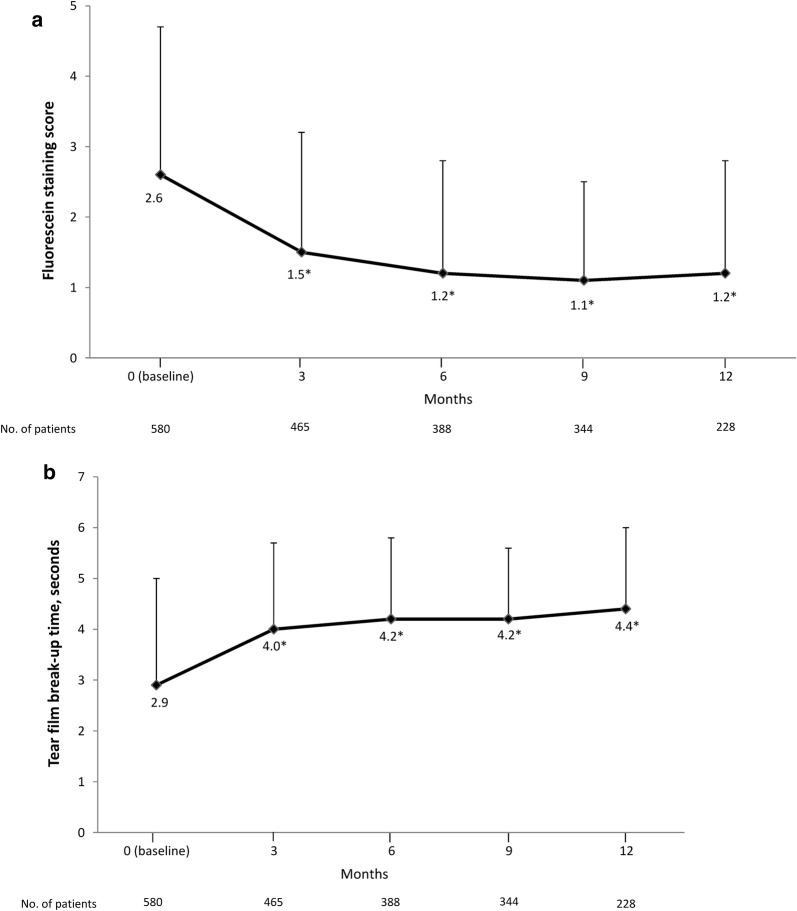

Diquafosol therapy was associated with significant improvements from baseline in fluorescein staining scores (Fig. 2a) and BUT (Fig. 2b) at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months (p < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Mean change in a fluorescein staining score and b tear film break-up time. Error bars represent standard deviation. *p < 0.001, versus baseline determined using paired t test

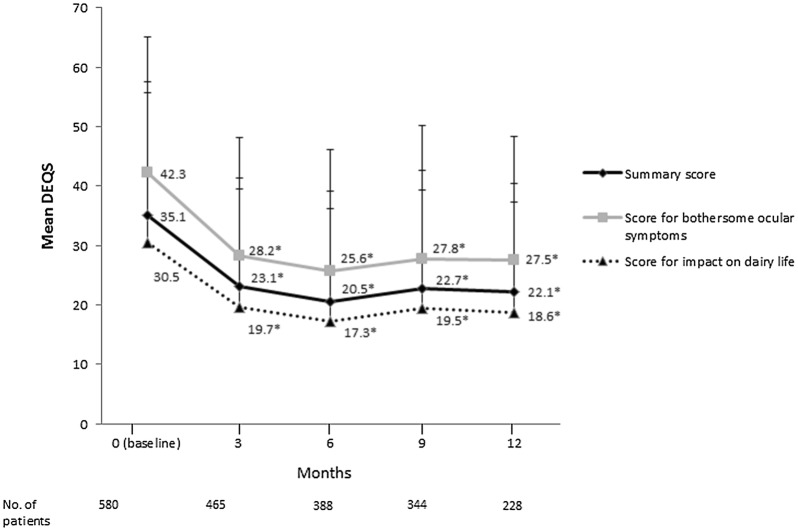

Compared with baseline, significant reductions in the DEQS overall summary score, ocular symptoms score and impact on daily life score were observed with diquafosol therapy at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months (Fig. 3; p < 0.001). Mean individual question scores were also significantly reduced from baseline (Table 4, Supplementary Fig. S1a, b).

Fig. 3.

Mean change in the Dry Eye-related Quality of Life Score (DEQS). Error bars represent standard deviation. *p < 0.001, versus baseline determined using paired t test

Table 4.

Change from baseline to final observation in mean Dry Eye-related Quality of Life Score

| Mean ± SD | Number of patients | p valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ocular symptoms | |||

| Foreign body sensation | − 0.6 ± 1.3 | 468 | < 0.001 |

| Dryness | − 0.7 ± 1.2 | 465 | < 0.001 |

| Pain or soreness | − 0.4 ± 1.2 | 458 | < 0.001 |

| Fatigue | − 0.7 ± 1.2 | 463 | < 0.001 |

| Heaviness in the eyelids | − 0.4 ± 1.2 | 459 | < 0.001 |

| Redness | − 0.4 ± 1.2 | 459 | < 0.001 |

| Impact on daily life | |||

| Difficulty opening the eyes | − 0.4 ± 1.2 | 456 | < 0.001 |

| Blurred vision during activities that require sustained visual concentration | − 0.4 ± 1.2 | 460 | < 0.001 |

| Light sensitivity | − 0.4 ± 1.2 | 456 | < 0.001 |

| Symptoms worsen when reading | − 0.4 ± 1.2 | 458 | < 0.001 |

| Symptoms worsen when watching television or using a computer or cell phone | − 0.5 ± 1.2 | 455 | < 0.001 |

| Eye symptoms reduce the ability to concentrate | − 0.4 ± 1.2 | 454 | < 0.001 |

| Eye symptoms affect work or study | − 0.5 ± 1.2 | 453 | < 0.001 |

| Not feeling like going out because of eye symptoms | − 0.1 ± 0.8 | 456 | < 0.001 |

| Feeling depressed because of eye symptoms | − 0.4 ± 1.2 | 457 | < 0.001 |

SD standard deviation

aVersus baseline determined using paired t test

Discussion

This prospective observational study reports the long-term safety and effectiveness of diquafosol 3.0% ophthalmic solution in 580 patients with DED over a period of 12 months in the real-world clinical setting. During the study, the incidence of ADRs was 10.7% and no serious ADRs were reported. Compared with baseline, significant improvements in all effectiveness outcomes, including keratoconjunctival fluorescein staining score, BUT and DEQS summary score, were observed at each evaluation during the treatment period.

In previous studies, the incidence of ADRs associated with diquafosol was 15.3% in the randomised, double-blind, phase III study conducted in 287 patients with DED over 4 weeks [12] and 4.9% in the prospective, real-world observational study conducted in 3196 patients with DED over 2 months [14]. In our real-world study, the incidence of ADRs was twice these values, but this was likely the result of the longer observation period during which ADRs could be reported. No serious ADRs were reported in any of these studies or in the current study, and the types of ADRs observed, such as eye irritation and eye discharge, were similar [12, 14]. Our results indicate that there are no new ADRs associated with long-term treatment.

The key goals of therapy in DED are to relieve symptoms and improve quality of life [16]. Therefore, it is important for treatments to demonstrate beneficial effects on patient-reported outcomes as well as on objective measures of ocular surface structure and function. The Osaka study showed that subjective symptom severity was associated with shorter tear film BUT (≤ 5 s) and fluorescein staining intensity [11]. Therefore, in Japan, where a high proportion of patients have short BUT [2], treatment that improves tear film stability (such as diquafosol) would be expected to produce symptomatic improvement. Indeed, in the present study, all effectiveness outcomes, including fluorescein staining score, BUT and DEQS (summary and subscale), were significantly improved relative to baseline at 3 months and the scores were maintained until the end of the 1-year study.

Similar to the present study, previous studies of diquafosol showed rapid improvements in fluorescein staining score and BUT, after 2 weeks in the phase III study [12] and after 1 month in the observational study [14]. Therefore, diquafosol appears to be consistently effective in improving objective measures of ocular surface health, regardless of study design.

Strengths of our study included the unselected patient population, reflecting a range of patients with DED seen in routine clinical practice, and the inclusion of patient-reported outcome measures, such as DEQS, along with objective assessments. The DEQS questionnaire was developed to evaluate the symptoms of DED and its effect on quality of life [15]. DEQS has good retest consistency, is easy to administer and its scores correlate well with other methods for assessing patient-reported outcomes, facilitating its use in clinical trials. For example, DEQS correlate closely with those of the mental component of the 8-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-8) and with Ocular Pain, Near Vision, Distance Vision and Mental Health subscales of the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire-25 (VFQ-25) [15].

This study had several limitations. Firstly, open-label observational studies may be subject to significant bias in favour of the study drug, both in the subjective and objective outcome measures. In addition, DED severity is influenced by circumstances such as working status, time since diagnosis and the level of computer use, which were not considered. The current study included a high proportion of elderly patients (42.8% were aged ≥ 70 years), and therefore, may under-represent some patient groups, such as office workers who experience DED during daily visual display terminal (VDT) use. Secondly, the proportion of patients who discontinued the study was relatively high. The most common reason was that the patient stopped visiting the hospital or clinic (54.6%), and a further 14.5% of patients reported an improvement in symptoms as the reason why they stopped treatment. Collectively, these reasons accounted for almost 70% of all discontinuations. It is not always possible to determine the precise reason why patients stop attending follow-up visits, particularly in observational studies, which tend to have less rigorous follow-up procedures compared with randomised clinical trials, and this is another limitation inherent in observational research [17, 18]. There have been little long-term observational research in a real-world setting including other therapeutic drugs for DED like this study. Taking those into consideration, the result from this study of high discontinuation rate may reflect the reality of treatment for DED in clinical practice.

Conclusion

The results of the present, real-world study showed that diquafosol 3.0% ophthalmic solution was well tolerated and effective in the long-term treatment of DED.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study and the journal’s Rapid Service and Open Access fees were funded by Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

We would like to thank Yoshiko Okamoto, PhD, and Georgii Filatov of inScience Communications, Springer Healthcare, who wrote the outline and the first draft of this manuscript, respectively. This medical writing assistance was funded by Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to scientific validation of study protocol. All authors also contributed to preparation and approval of the manuscript.

Disclosures

Yuichi Ohashi reports personal fees from Santen during the conduct of the study, personal fees from Santen and Otsuka, outside the submitted work. Jun Shimazaki reports Grants from Santen and Hoya, personal fees from Santen, Otsuka, Senju, Alcon Japan, QD laser and IDD. Etsuko Takamura reports personal fees from Santen during the conduct of the study, and personal fees from Santen, outside the submitted work. Norihiko Yokoi reports personal fees from Santen during the conduct of the study, personal fees from Alcon Japan, Rhoto, Otsuka and Senju, outside the submitted work. In addition, Norihiko Yokoi has a patent for an ophthalmologic apparatus (with Kowa). Hitoshi Watanabe reports personal fees from Santen during the conduct of the study, personal fees from Santen, outside the submitted work. Masahiro Munesue is an employee of Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Akio Nomura is an employee of Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Fumiki Shimada is an employee of Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This post-marketing study was conducted in accordance with the Ministerial Ordinance on Good Post-Marketing Study Practice (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Ordinance No. 171, December 20, 2004). The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Japanese regulatory authorities before initiation. According to Japanese regulations, post-marketing studies do not require approval of the ethics committees at individual study sites and patients’ informed consent. Verbal consent was obtained from all patients, with the option of also obtaining written consent.

Footnotes

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.11294864.

References

- 1.Farrand KF, Fridman M, Stillman IO, Schaumberg DA. Prevalence of diagnosed dry eye disease in the United States among adults aged 18 years and older. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;182:90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2017.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uchino M, Yokoi N, Uchino Y, et al. Prevalence of dry eye disease and its risk factors in visual display terminal users: the Osaka study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;156(4):759–766. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shimazaki J. Definition and diagnostic criteria of dry eye disease: historical overview and future directions. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59(14):7–12. doi: 10.1167/iovs.17-23475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Craig JP, Nichols KK, Akpek EK, et al. TFOS DEWS II definition and classification report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):276–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsubota K, Yokoi N, Shimazaki J, et al. New perspectives on dry eye definition and diagnosis: a consensus report by the Asia Dry Eye Society. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(1):65–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Revised definition and diagnosis criteria of dry eye in Japan, 2016 [database on the Internet]. http://www.nichigan.or.jp/member/guideline/dryeye.pdf. Accessed Feb 22 2019.

- 7.Shimazaki J. Diagnosis criteria of dry eye. Atarashii Ganka. 2007;24(2):181–184. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Begley CG, Chalmers RL, Abetz L, et al. The relationship between habitual patient-reported symptoms and clinical signs among patients with dry eye of varying severity. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(11):4753–4761. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mizuno Y, Yamada M, Miyake Y. Association between clinical diagnostic tests and health-related quality of life surveys in patients with dry eye syndrome. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2010;54(4):259–265. doi: 10.1007/s10384-010-0812-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolffsohn JS, Arita R, Chalmers R, et al. TFOS DEWS II diagnostic methodology report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):539–574. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yokoi N, Uchino M, Uchino Y, et al. Importance of tear film instability in dry eye disease in office workers using visual display terminals: the Osaka study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;159(4):748–754. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takamura E, Tsubota K, Watanabe H, Ohashi Y. A randomised, double-masked comparison study of diquafosol versus sodium hyaluronate ophthalmic solutions in dry eye patients. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96(10):1310–1315. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-301448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drug profile: diquafosol—Merck/Santen pharmaceutical. [database on the Internet]. Adis International Ltd., part of Springer Science + Business Media 2019. https://adisinsight.springer.com/drugs/800010767. Accessed Mar 14 2019.

- 14.Yamaguchi M, Nishijima T, Shimazaki J, et al. Clinical usefulness of diquafosol for real-world dry eye patients: a prospective, open-label, non-interventional, observational study. Adv Ther. 2014;31(11):1169–1181. doi: 10.1007/s12325-014-0162-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakane Y, Yamaguchi M, Yokoi N, et al. Development and validation of the Dry Eye-related Quality-of-Life Score questionnaire. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131(10):1331–1338. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.4503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin The management of dry eye. BMJ. 2016;353:i2333. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berger ML, Dreyer N, Anderson F, Towse A, Sedrakyan A, Normand SL. Prospective observational studies to assess comparative effectiveness: the ISPOR good research practices task force report. Value Health. 2012;15(2):217–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mann CJ. Observational research methods. Research design II: cohort, cross sectional, and case-control studies. Emerg Med J. 2003;20(1):54–60. doi: 10.1136/emj.20.1.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.