Abstract

Purpose

A previous study found that milestone ratings at the end of training were higher for male than for female residents in emergency medicine (EM). However, that study was restricted to a sample of 8 EM residency programs and used individual faculty ratings from milestone reporting forms that were designed for use by the program’s Clinical Competency Committee (CCC). The objective of this study was to investigate whether similar results would be found when examining the entire national cohort of EM milestone ratings reported by programs after CCC consensus review.

Method

This study examined longitudinal milestone ratings for all EM residents (n = 1,363; 125 programs) reported to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education every 6 months from 2014 to 2017. A multilevel linear regression model was used to estimate differences in slope for all subcompetencies, and predicted marginal means between genders were compared at time of graduation.

Results

There were small but statistically significant differences between males’ and females’ increase in ratings from initial rating to graduation on 6 of the 22 subcompetencies. Marginal mean comparisons at time of graduation demonstrated gender effects for 4 patient care subcompetencies. For these subcompetencies, males were rated as performing better than females; differences ranged from 0.048 to 0.074 milestone ratings.

Conclusions

In this national dataset of EM resident milestone assessments by CCCs, males and females were rated similarly at the end of their training for the majority of subcompetencies. Statistically significant but small absolute differences were noted in 4 patient care subcompetencies.

Society depends upon residency programs, licensing agencies, and specialty boards to use assessment data to determine that a trainee is ready for completion of supervised training. It is critical that assessments and summary judgments accurately reflect the ability of the resident and that sources of error and bias are accounted for. Since December 2013, as part of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Next Accreditation System (NAS),1 residency programs have implemented milestone assessment systems that collect and synthesize competency performance data to inform decisions regarding resident progression and readiness for practice without supervision.2 Each residency program is mandated to have in place a Clinical Competency Committee (CCC) whose responsibility is to generate milestone ratings for each resident based on aggregated assessment data from individual faculty and other sources. The milestone ratings made by the CCC are submitted to the ACGME on a semiannual basis and enable the longitudinal analysis of residents’ development for both the individual resident and the program.

Emergency medicine (EM) was one of the first specialties to develop milestones through a multistep, rigorous process that included a consensus of national experts, based on the EM practice model.3–7 In the implementation of the milestones project, the reporting milestones used by the CCCs were not intended to be used as individual assessment tools, but rather a schema to guide programs in making judgments about the progression of their residents.8 However, as EM engaged in efforts to meet NAS aims, many EM programs developed assessment tools that directly reflect the reporting milestones9,10 that are used in semiannual CCC deliberations regarding resident performance.

Within a residency program, the CCC examines multiple sources of data in a group setting of educational leaders. These data might include direct observations; procedure logs; off-service rotation assessments; monthly global assessments; simulation sessions; professionalism or communication concerns; clinical skills; mock oral board examinations; peer, nursing, and staff assessments; self-assessment; compliance with departmental policies; committee appointments; and involvement with special projects.9,11,12 In aggregate, and following discussion among committee members, the CCC determines the level of competency each resident has achieved for each subcompetency and submits milestone ratings to the ACGME every 6 months.

Recently, Dayal and colleagues raised concerns about potential gender bias in EM assessments by faculty.10 At 8 residency programs between July 2013 and July 2015, faculty completed a mobile app-based direct observation milestone assessment tool. The authors found that for all 23 EM subcompetencies, females and males were rated similarly at the beginning of residency, but males were rated slightly higher than females by the time of graduation (a difference of 0.01 to 0.26 milestones on the 5-point scale). The authors proposed 2 potential reasons for these differences in gender performance during the final year of residency: first, that there is implicit gender bias in the assessments by faculty, in that women are perceived as less competent than their male counterparts; second, that women actually performed lower than their male counterparts.

The Dayal study specifically looked at the faculty assessments that contribute to CCC deliberations but not the final milestones judgment of the CCC itself. While gender bias in the direct observation data that informs CCC decisions is an important problem, it is unclear whether there were gender differences in the final milestone ratings reported to the ACGME.

The purpose of our study was to investigate whether similar gender differences would be found in a national EM milestones dataset reported by programs after CCC consensus review.

Method

Setting and participants

The Common Program Requirements2 assign the CCC for each program the responsibility to prepare and ensure the reporting of milestones assessments of each resident semiannually to the ACGME. The data for this study were based on these reported milestones from each program. We extracted residents’ milestones data from the cohort of residents who entered 3-year EM training programs in July 2014 and graduated in June 2017 (1,363 residents from 125 programs). Twenty-seven residents with missing gender information were excluded, as were data from programs reporting residents of only one gender (female: 1 program; male: 6 programs). This resulted in 1,282 residents from 117 programs: female = 446 (34.8%); male = 836 (65.2%), for whom we used data in the subsequent analyses.

The EM milestones reporting form consisted of 23 subcompetencies (see Table 1). The medical knowledge subcompetency was modified in July 2015, and thus we excluded it from the analysis. Possible milestone ratings were level 0.0, 1.0, 1.5, continuing at half-point intervals through 4.5 and 5.0, which were treated as an interval scale for analytic purposes. (Level 0.0 was coded as “Had not achieved Level 1.”)13 We deidentified all data in the analyses.

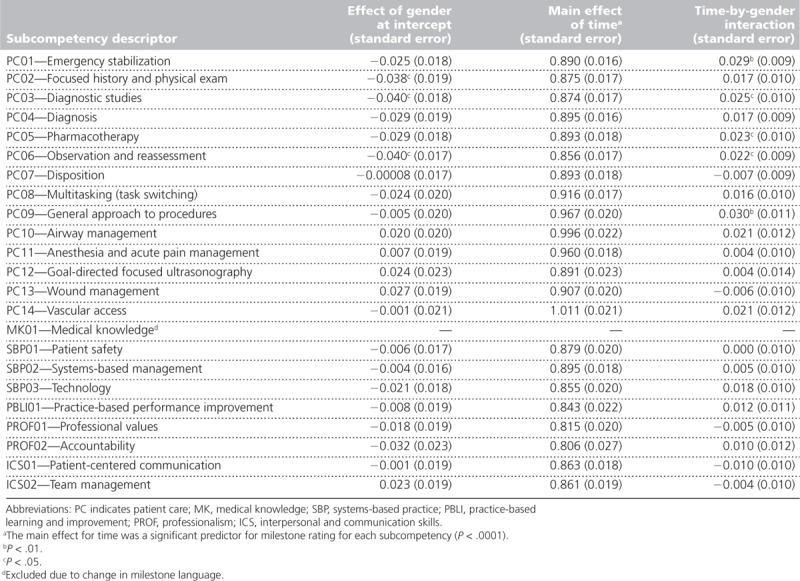

Table 1.

Regression Coefficients of Emergency Medicine Resident Milestone Ratings by Subcompetency, From a National Study of Milestone Assessment Ratings by Gender, 2014–2017

Analytic approach

Residents’ milestone ratings were generated 6 times over the period covered by this study (December 2014–June 2017). To account for possible intercorrelations, we applied a 3-level random coefficient linear regression model using restricted maximum likelihood estimation to each of the 22 subcompetencies. Using this regression model, we sought to determine if a resident’s gender was differentially predictive of their initial milestone ratings, final ratings, or growth in rating over time spent in residency. Specifically, intercepts were specified as randomly varying among residents within the program, but slopes were treated as fixed within each program. We modeled program-level intercepts and slopes to vary among programs.

Each regression model included the regression coefficients for time spent in residency (in 6-month increments), gender, and the time-by-gender interaction. We coded time spent in residency as 0.0 at the initial time of assessment (i.e., December 2014), 0.5 for June 2015, 1.0 for December 2015, 1.5 for June 2016, 2.0 for December 2016, and 2.5 for June 2017. Gender was coded as 1 for male and 0 for female, such that a positive coefficient for gender indicates an effect due to male gender (see Table 1). The regression coefficient for time indicates the linear growth in milestone rating throughout the course of residency. With these coding arrangements, gender effects on initial milestone ratings and growth trajectories could be investigated by examining the regression coefficients for gender and the time-by-gender interaction, which served as the primary variables of interest in this study.

Using the same model, we compared the predicted marginal means between genders at the time of graduation to see if there were any group differences. Using linear extrapolation, this gender difference at the time of graduation could be converted to additional months of training that may be necessary to compensate for any observed difference (as in Dayal et al).10 We conducted all analyses using SAS Enterprise statistical software, version 7.11 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). Statistical significance was presumed at P < .05 (2-tailed test). This study was deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Board of the American Institutes for Research (EX00382).

Results

Initial rating differences/slope difference

We found that 6 of the 22 subcompetencies, all from the general competency of patient care, showed a small but statistically significant effect of gender on milestone ratings for this national-level dataset. Specifically, on the Focused history and physical exam subcompetency, females had initial ratings higher than males (Table 1), but this effect disappeared at the time of graduation (Table 2). On 3 subcompetencies (Emergency stabilization, Pharmacotherapy, General approach to procedures), males and females had equivalent ratings at the beginning of training, but the rates of growth were found to be higher for males than for females (Table 1). Finally, on 2 subcompetencies (Diagnostic studies, Observation and reassessment), males were initially rated lower than females but grew faster than females throughout residency. With all of these findings, the changes were small. There was no gender effect for any of the subcompetencies from the other 5 competency domains.

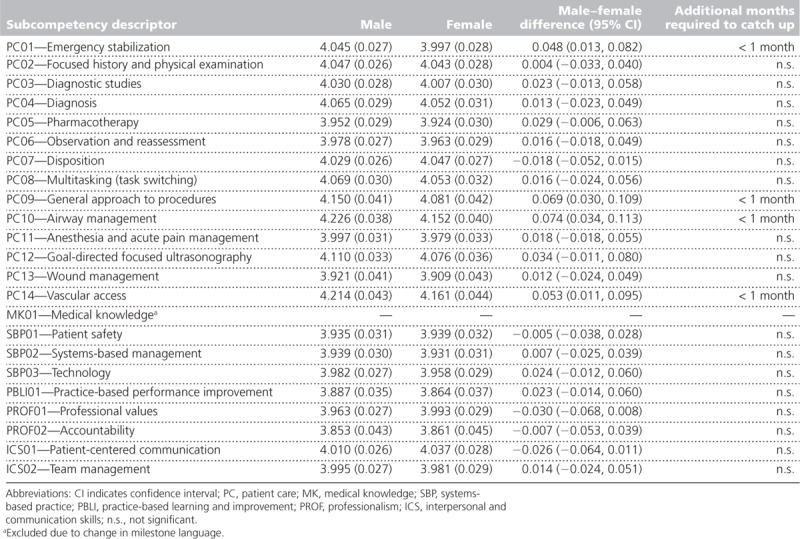

Table 2.

Estimated Group Means and Differences Between Male and Female Emergency Medicine Residents at Time of Graduation from Residency, From a National Study of Milestone Assessment Ratings by Gender, 2014–2017

Differences at time of graduation

Table 2 shows the estimated marginal means (and difference between genders) for each subcompetency and extrapolated additional months of training to catch up for the difference. Marginal mean comparisons revealed gender effects for 4 of the 22 subcompetencies at graduation, all in patient care (Emergency stabilization, General approach to procedures, Airway management, Vascular access) (Table 2). For these subcompetencies, males were rated as performing better than females (0.048, 0.069, 0.074, and 0.053 milestone unit difference on the 5-point scale, respectively). Where differences did exist, the extrapolated educational time effect equated to less than 1 month.

Discussion

In this national dataset of EM resident milestone assessments, males and females were rated similarly by the program throughout their training for the majority of subcompetencies. Statistically significant but very small absolute differences were noted in several subcompetencies, all within the general competency of patient care. It is noted that statistical significance is accentuated by a large sample size, and the observed differences in milestone ratings of 0.048 to 0.074 (on a 5-point scale) at graduation between males and females (see Table 2) are not likely educationally significant judgments at the level of the program. The educational implications and impact of small differences in ratings are unclear and require ongoing follow-up.

Our findings differ from those of the Dayal study, which found gender differences at graduation but not at first year of residency. Dayal and colleagues suggested that women may lag in achievement of some milestones and estimated an educational effect of the differences equivalent to additional 3–4 months of training for female residents. In contrast, we found estimated time of graduation based on milestone performance be slightly longer for females for only 4 of 22 subcompetencies.

Our study had 2 major methodological differences from the work of Dayal and colleagues. First, we used national resident data from 125 residency programs and followed each resident longitudinally. Second, the nature of the assessment data was very different. In the Dayal study, each faculty rater completed shift-based assessments of performance on a custom-designed application for mobile handheld devices. Our study made use of the milestone assessment ratings submitted to the ACGME after CCC review of comprehensive and collated programmatic assessment data based on 6 months of observation. The small differences found in milestone ratings could be from differences in the frontline assessments aggregated or as part of the CCC decisions.

Both studies found gender differences in the patient care milestones, including general procedures, airway management, and emergency stabilization. The original Dayal study was followed by a qualitative analysis of the comments from faculty using the mobile application. Again, gender differences were noted.10,14 When male residents struggled, they received consistent feedback about areas of their performance that needed work. In contrast, when female residents struggled, they received both praise and criticism (discordant feedback),15 particularly regarding issues of autonomy and assertiveness. The authors also note that high-performing residents also demonstrated certain behaviors such as “confident, able to multitask” and note that “many of these characteristics have been identified in prior research as stereotypically masculine traits.”14 These findings may be helpful as a starting point of discussion for faculty assessors to discuss what is a good resident in the context of implicit bias. Additionally, this type of information may be useful to CCCs as they review narrative comments to determine final milestone ratings as well as provide feedback to residents. Similarly, it is important to note that gender bias may also influence CCC discourse and decisions. Implicit bias training may help mitigate the hidden biases present in the assessment culture.

While the decision-making process for CCCs is not completely understood, the purpose of the CCC is to gather assessment data points and render a summative decision for each of the subcompetencies for that point in time. Hauer and colleagues conducted a narrative review of group decision making to inform CCCs.16,17 They noted that group decisions may be affected by the types of information shared, the size and composition of the group, common understanding of how decisions are made, and a shared mental model. These decisions depend in large part on the assessment data, preferences held by members, and the processes that guide members to understand and conduct their work. While the Dayal study demonstrated differences in individual assessment performance of third-year EM female and male residents, it should be noted that, under the NAS, the expectation is that individual assessments are entered into a more holistic decision-making process involving all members of the CCC.18 The ACGME encourages CCC members to engage in programmatic assessment by examining multiple sources of data and to render summative milestone ratings as a group. As our study did not show the same level of gender bias as the Dayal study, it is possible that a group consensus process may mitigate unconscious gender biases of individuals generating individual workplace-based assessments. Further research is needed to better understand CCC data processing and decision making.

The milestone assessments and competency committee decisions are relatively new, and accordingly there may be significant variation in residency program processes during this period of developmental growth in generating milestone ratings over the years of the study. Although there is not a standard structure or process for CCCs across specialties,11,19,20 Doty and colleagues examined EM CCCs and found the majority of CCC members included residency program leadership and core faculty who meet regularly to determine level of milestone achievement for each resident using multiple sources of information.11 They noted that the group function of the CCC served to limit bias since summative decisions were no longer made based upon the assessment of 1 person, such as the program director, as was common in the past. Despite the potential differences in CCC processes, we did not detect major gender bias in the programs’ milestone judgments.

While the Dayal findings and our findings may appear contradictory, each study’s methods are quite different. Faculty ratings on a mobile app after a resident’s shift may be subject to implicit bias due to rapid assessments made on an individual’s performance. This is very different from the rating given by a CCC, which takes into account a variety of data and also is discussed in a committee format. Implicit bias may be mitigated when the collated assessment data are discussed and synthesized by the CCC. While milestone rating forms are used by some programs for generating individual faculty ratings, the ACGME explicitly recommends against this process to reduce unwanted sources of variance in generating milestone ratings.18

Gender bias clearly exists; there are studies in medicine as well as other fields documenting contexts in which this phenomenon occurs. The difficulty is knowing when it is present and meaningful. As Cooke called for in her commentary, “Implicit bias in academic medicine: #WhatADoctorLooksLike,”21 our response should be to track how our data-driven, sex- and race-neutral processes are actually performing. We have a responsibility with future work to seek to understand how CCCs make decisions and to monitor for gender bias through qualitative work. Further, programs may want to examine their own gender performance differences and, if differences are present, to consider whether there are lower ratings for women during CCC discussions. In addition, future work might apply the methods presented in this study to data from other specialties to track and monitor for signs of gender bias, given the importance of this issue.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. Since the milestone ratings reported to the ACGME may be subject to some degree of social desirability, given the context of reporting to an accrediting body, there might be concern within a program if too many residents are progressing slowly or appear to need remediation. It should be noted that it is an explicit policy of the ACGME that the review committees that accredit programs do not use milestone ratings for making accreditation decisions.18 The ACGME milestone reporting system is completely separate from the accreditation branch of the ACGME, yet programs may not be aware of or trust this separation. In addition, while the ACGME common program requirements instruct the CCC of each program to assign milestone ratings, exactly how and who assigns milestone ratings for each program is not known.

Second, while in aggregate we did not see the same degree of difference in milestone ratings by gender as in the Dayal study, there may be underlying program-level gender differences in assessment and elsewhere (e.g., for selection). We did not specifically examine the 8 residency programs from Dayal and colleagues’ study to determine if their CCC milestone ratings showed similar gender differences to their individual faculty ratings. We did not account for the gender of the program director or of the CCC. Further studies might explore program-level gender differences. We excluded a few programs because they only had residents of male gender in the cohort; therefore, we cannot speak to whether those programs experience bias. In addition, 4-year EM programs were excluded due to the difference in their growth of milestones over the 4 years and may represent a different population.

Conclusions

For EM resident milestone ratings submitted by programs, males and females were rated similarly throughout their training for the majority of subcompetencies. Statistically significant but very small effects were noted in a few subcompetencies, all within the general competency of patient care. These differences may not be educationally significant, and further study is warranted.

Footnotes

Funding/Support: None reported.

Other disclosures: Virginia Commonwealth University receives funding for Dr. Santen outside of this work from the American Medical Association Accelerating Change in Medical Education grant for program evaluation. Other authors do not have relevant financial interests.

Ethical approval: This study was deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Board of the American Institutes for Research (AIR EX00382).

Previous presentations: Portions of this work have been previously presented at the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Annual Education Conference, Orlando, Florida, March 3, 2018; the annual meeting of the Association for Medical Education in Europe, Basel, Switzerland, August 30, 2018; and the Association of American Medical Colleges Medical Education Meeting, Austin, Texas, November 2, 2018.

Data: The authors had permission from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education to use the data for research purposes.

References

- 1.Nasca TJ, Philibert I, Brigham T, Flynn TC. The next GME accreditation system—Rationale and benefits. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1051–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Common Program Requirements. https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs2013.pdf. Accessed August 28, 2019.

- 3.American Board of Emergency Medicine. The 2007 Model of the Clinical Practice of Emergency Medicine. https://www.abem.org/public/docs/default-source/default-document-library/2007-em-model2.pdf?sfvrsn=bc98c9f4_0. Accessed November 22, 2019.

- 4.Beeson MS, Carter WA, Christopher TA, et al. The development of the emergency medicine milestones. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20:724–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beeson MS, Carter WA, Christopher TA, et al. Emergency medicine milestones. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(1 suppl 1):5–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korte RC, Beeson MS, Russ CM, Carter WA, Reisdorff EJ; Emergency Medicine Milestones Working Group. The emergency medicine milestones: A validation study. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20:730–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beeson MS, Holmboe ES, Korte RC, et al. Initial validity analysis of the emergency medicine milestones. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22:838–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holmboe ES, Yamazaki K, Edgar L, et al. Reflections on the first 2 years of milestone implementation. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7:506–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hauff SR, Hopson LR, Losman E, et al. Programmatic assessment of level 1 milestones in incoming interns. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21:694–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dayal A, O’Connor DM, Qadri U, Arora VM. Comparison of male vs female resident milestone evaluations by faculty during emergency medicine residency training. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:651–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doty CI, Roppolo LP, Asher S, et al. How do emergency medicine residency programs structure their Clinical Competency Committees? A survey. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22:1351–1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perry M, Linn A, Munzer BW, et al. Programmatic assessment in emergency medicine: Implementation of best practices. J Grad Med Educ. 2018;10:84–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, American Board of Emergency Medicine and The Emergency Medicine Milestones Project. http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PDFs/Milestones/EmergencyMedicineMilestones.pdf. Published 2012. Accessed August 28, 2019.

- 14.Mueller AS, Jenkins TM, Osborne M, Dayal A, O’Connor DM, Arora VM. Gender differences in attending physicians’ feedback to residents: A qualitative analysis. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9:577–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sargeant J, Armson H, Chesluk B, et al. The processes and dimensions of informed self-assessment: A conceptual model. Acad Med. 2010;85:1212–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hauer KE, Chesluk B, Iobst W, et al. Reviewing residents’ competence: A qualitative study of the role of clinical competency committees in performance assessment. Acad Med. 2015;90:1084–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hauer KE, Cate OT, Boscardin CK, et al. Ensuring resident competence: A narrative review of the literature on group decision making to inform the work of Clinical Competency Committees. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8:156–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holmboe ES, Edgar L, Hamstra S; Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Milestones Guidebook. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/MilestonesGuidebook.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed August 28, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Chen F, Arora H, Martinelli SM. Use of key performance indicators to improve milestone assessment in semi-annual Clinical Competency Committee meetings. J Educ Perioper Med. 2017;19:E611. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nabors C, Forman L, Peterson SJ, et al. Milestones: A rapid assessment method for the Clinical Competency Committee. Arch Med Sci. 2017;13:201–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooke M. Implicit bias in academic medicine: #WhatADoctorLooksLike. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:657–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]