Abstract

The incidence of renal-cell carcinoma has been increasing each year, with nearly one third of new cases diagnosed at advanced or metastatic stage. The advent of targeted therapies for metastatic renal-cell carcinoma (mRCC) has underscored the need to subtype tumors according to tumor-immune expression profiles that may more reliably predict treatment outcomes. Over the past 2 decades, several vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and tyrosine kinase inhibitors have been the mainstay for first- and second-line treatment of mRCC. Very recently, immunotherapy checkpoint inhibitors have significantly changed the treatment landscape for patients with mRCC, particularly for first-line treatment of intermediate to poor risk mRCC patients. Now, combination immunotherapy as well as combinations of immunotherapy with targeted agents can significantly alter disease outcomes. The field of immuno-oncology for mRCC has unveiled a deeper understanding of the immunoreactivity inherent to these tumors, and as a result combination therapy is evolving as a first-line modality. This review provides a timeline of advances and controversies in first-line treatment of mRCC, describes recent advances in understanding the immunoreactivity of these tumors, and addresses the future of combination anti-VEGF and immunotherapeutic platforms.

Keywords: Immune checkpoint inhibitors, Metastatic renal-cell carcioma, Targeted therapies, VEGF-immunotherapy combinations, VEGF therapies

Introduction

Renal-cell carcinoma (RCC) represents approximately 90% of all renal cancers, with 85% of RCC identified as the clear-cell subtype.1 The incidence of RCC has increased by approximately 2% per year over the last 65 years.2 Strikingly, nearly one third of patients are initially diagnosed with advanced or metastatic RCC (mRCC).3-6 mRCC has a variety of clinical presentations, however, and risk assessment is important, both to determine prognosis and to stratify patients for clinical drug development.

In the age of targeted therapies, risk assessment for mRCC patients was established with the International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database (IMDC) criteria. From a multicenter cohort of 645 patients, 6 clinical factors were shown to be independently prognostic of survival on multivariable analysis: (1) anemia, (2) neutrophilia, (3) thrombocytosis, (4) hypercalcemia, (5) Karnofsky performance status < 80, and (6) < 1 year from diagnosis to first-line systemic therapy.7 Favorable risk patients had none of these factors, intermediate risk patients had 1 or 2 of these factors, and poor risk patients had more than 3 of these clinical factors. Risk stratification has now become a key part of clinical decision making, both for regulatory agencies granting indications for treatment and for clinicians selecting treatments for patients.

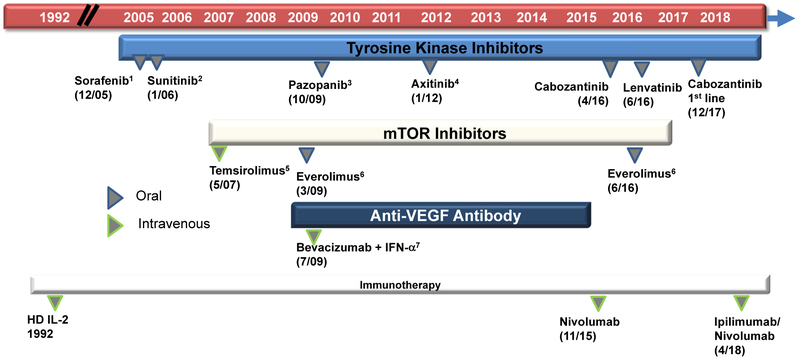

Over the past decade, the introduction of targeted therapies has greatly improved the outcomes of patients with mRCC.4-6 Multi-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), which inhibit vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (VEGFR) and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), have been standard therapy options for patients with mRCC (Figure 1). Of these, sunitinib and pazopanib have been commonly used for first-line treatment of mRCC.8 However, in December 2017, cabozantinib was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for first-line use in mRCC based on improved progression-free survival (PFS) compared to sunitinib.9 In non–clear-cell RCC, particularly papillary RCC, sunitinib still represents the preferred front-line therapy based on 2 randomized trials (Aspen and ESPN).10,11 Finally, in patients with poor-risk RCC or chromophobe RCC, an mTOR-based strategy may have superior efficacy over vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibition.12

Figure 1. US Food and Drug Administration Approval Timeline of Treatment Options for Metastatic Renal-Cell Carcinoma Therapy.

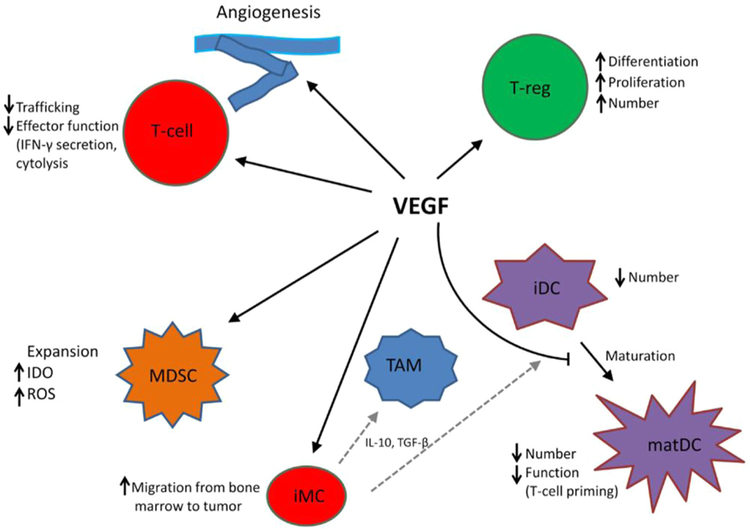

Within the past 3 years, immunotherapy checkpoint inhibitors (CPIs) have significantly changed the treatment landscape for patients with mRCC. The combination of ipilimumab with nivolumab has further improved clinical outcomes and has been approved for first-line treatment of intermediate to poor risk mRCC patients.13 With a more complex understanding of cross-talk between RCC signaling pathways such as VEGF and the tumor microenvironment and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in mRCC, there is a rationale for combining VEGF and immunotherapy agents (Figure 2), and early clinical trial data support these strategies (ClinicalTrials.gov ). However, combination therapy is accompanied by increased adverse events (AEs), cost, and effects on sequencing second-line treatments. Furthermore, to date, there are no randomized data comparing combination immunotherapies to one another.

Figure 2. VEGF Modulation of Function of T Cells, Suppressive Immune Cells, and Stroma in Tumor Microenvironment. Dotted Gray Lines Indicate Differentiation From iMC to TAM and iDC, Respectively.

Abbreviations: iDC = immature dendritic cell; iMC = immature myeloid cell; matDC = mature dendritic cell; MDSC = myeloid-derived suppressor cell; TAM = tumor-associated macrophage; T-reg = T-regulatory cell.

Data from Ott PA, Hodi FS, Buchbinder EI. Inhibition of immune checkpoints and vascular endothelial growth factor as combination therapy for metastatic melanoma: an overview of rationale, preclinical evidence, and initial clinical data. Front Oncol 2015; 5:202.

Here we discuss recent advances and controversies in first-line treatment of mRCC using anti-VEGF monotherapy, discuss immunotherapies, and address the future of combination approaches with anti-VEGF and immunotherapy.

First-Line Therapy With Antiangiogenic Agents

As our basic understanding of RCC pathophysiology and its dependency on angiogenesis increased, this has translated into the successful development of VEGFR TKI monotherapy targeted agents. The von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) gene encodes an E3 ligase that cooperates in ubiquitination of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α, targeting it for proteasome degradation. When VHL is lost or inactivated in up to 80% of sporadic cases of clear-cell carcinoma, HIF-1α overaccumulates, resulting in up-regulation of VEGF and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF).14 With unopposed stimulation of VEGF and PDGF receptors (VEGFR and PDGFR), tumor angiogenesis, growth, and metastasis ensue.15 Initial proof-of-concept studies for targeting angiogenesis demonstrated that bevacizumab, an anti-VEGF antibody, showed notable efficacy in RCC.16-18 Since then, multiple VEGFR TKIs have been FDA approved for either first- or second-line treatment of mRCC.

For this review, we summarize the first-line VEGF TKI data of sorafenib, sunitinib, pazopanib, and cabozantinib (Table 1).12,19-24

Table 1. Historic Phase 3 Trials in First-Line Treatment of Metastatic Renal-Cell Carcinoma.

| Treatment Arm |

Comparison Arm |

No. of Patients |

ORR (% CR/% PR) |

mPFS | mOS | Most Common Grade 3/4 AEs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sorafenib | Placebo | 903 | 10% vs. 2% | 5.5 vs. 2.8 mo | NR (HR = 0.72) | Hypertension, HFS, anemia |

| Sunitinib | Interferon α | 750 | 31% vs. 6% | 11 vs. 5 mo | NR (HR = 0.65) | Hypertension, diarrhea, neutropenia, increased lipase |

| Pazopanib | Placebo | 435 | 30% vs. 3% | 9.2 vs. 4.2 mo | NR | Hypertension, diarrhea, transaminitis |

| Pazopanib | Sunitinib | 1110 | 31% vs. 24% | 8.4 vs. 9.5 mo | 28.4 vs. 29.3 mo | Hypertension, fatigue, HFS, transaminitis |

| Temsirolimus | Interferon α | 626 | 8.6% vs. 4.8% | 5.5 vs. 3.1 mo | 10.9 vs. 7.3 mo | Anemia, hyperglycemia, dyspnea, asthenia |

| Cabozantinib | Everolimus | 658 | 17% vs. 3% | 7.4 vs. 3.9 mo | 21.4 vs. 16.5 mo | Diarrhea, fatigue, nausea, decreased appetite, PPE |

| Cabozantinib | Sunitinib | 157 | 20% vs. 9% | 8.6 vs. 5.3 mo | 26.6 vs. 21.2 mo | Diarrhea, hypertension, fatigue, PPE |

Abbreviations: AE = adverse event; CR = complete response; HFS = hand–foot syndrome; HR = hazard ratio; mOS = median overall survival; mPFS = median progression-free survival; NR = not reported; ORR = objective response rate; PPE = palmar–plantar erythrodysesthesia; PR = partial response; SD = stable disease.

Immuno-oncology Therapies for mRCC

Despite the clinical benefit of first-line antiangiogenesis therapy, tumor resistance often develops within the first year of treatment, underscoring a need for therapies that produce more durable responses with (ideally) less toxicity.25 Historically, RCC has been known to be immunogenic and immunoresponsive, with low levels (5%-8%) of durable complete responses to high-dose interleukin (IL)-2.26,27 Durable complete responses are rare (1%) with VEGF-targeted strategies alone in mRCC.13,22 The advent of CPIs for treatment of various solid tumors has offered much promise, given the immune system’s capacity for memory and its exquisite specificity. In addition, immunotherapy offers antitumor memory responses should tumors recur, a unique feature distinct from targeted therapies. In mRCC, immunotherapy CPIs have demonstrated considerable disease efficacy and have now been established as the standard of care in the first-line treatment of mRCC.

Below we summarize the current understanding of interactions between the tumor microenvironment and dynamic immune infiltrates in mRCC, and how immunotherapy CPIs can exploit these interactions.

Tumor Microenvironment and TILs in mRCC

To employ immunotherapy for mRCC, a better understanding of the tumor immune microenvironment is essential for deciphering the mechanisms of tumor immune evasion and active suppression. One approach examines the association between TIL content with clinicopathologic characteristics of the tumors and patient outcomes.

T lymphocytes are the primary effector population that can recognize and respond to atypical malignant tumor cells, with the ultimate goal to engender tumor-cell–specific killing by antigen-specific T-lymphocyte populations. Activation and subsequent development of effector and memory CD8+ T lymphocytes occurs by contact with their foreign antigen (peptide bound to major histocompatibility complex [MHC]) on antigen-presenting cells and costimulation by antigen-presenting cells, leading to increased cytokine gene expression, promotion of T-lymphocyte survival, and maintenance of T-cell responsiveness.28 The potency and presence of TILs in RCC and other solid tumors may be related to both host- and tumor-specific factors, including human leukocyte antigen expression, PBRM1 loss, neoantigen expression, tumor mutational burden, programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression, and gut microbiome content, thus illustrating the complexity of predicting response to immunotherapy.29-33

Infiltrates of T lymphocytes have revealed prognostic significance in RCC. For instance, high-density CD4+ T-cell infiltrates have been associated with unfavorable tumor characteristics and poor prognosis. This negative association has been predominantly attributable to the tolerizing CD4+ population of regulatory T cells (Treg). High proportions of Foxp3+ Tregs among both peripheral blood mononucleated cells and TILs have been associated with metastatic relapse and poor prognosis in RCC patients.34-37 Furthermore, Tregs isolated from TILs demonstrated more immunosuppressive activity than those from peripheral blood mononuclear cells.38 Results from a study by Siddiqui et al,39 however, suggested that the negative effect on survival is attributed to Foxp3-negative rather than Foxp3-positive Tregs. Thus, the role of cytotoxic CD8+ TILs has been controversial in the context of RCC, with several studies demonstrating conflicting results.40-45 This discrepancy led investigators to examine the relative ratios of the various TIL subsets as a measure of balance between the active antitumor lymphocyte populations and immunoregulatory/suppressive populations. In turn, it was soon discovered that high ratios of CD8+ to Foxp3+ Tregs among TILs in a variety of solid tumors are associated with favorable tumor characteristics, response to therapy and radiation, and improved patient survival.46-49 These high ratios of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells to Foxp3+ Tregs seem to also predict for treatment outcomes with immunotherapy in mRCC treated with atezolizumab.50

Natural killer (NK) cells are innate immune cells (ICs) that share an equally important role in tumor killing, as they also carry the capacity to kill cancerous cells while sparing normal cells. They do not rely on MHC binding like T lymphocytes do and are thus another promising effector cellular pathway to attack tumors that down-regulate the MHC antigen-presenting mechanism. The cytolytic activity of NK cells is determined by a balance between activating receptors and inhibitory receptors that are coexpressed on individual NK cells.

A distinct feature of RCC is its proclivity to attract a great variety of ICs to the tumor. RCC by nature attracts high levels of TILs, and NK cells are consistently identified.51 Even so, poor survival is indicated when NK cells make up less than 20% of the total TIL population for advanced RCC tumors.52-55 Other studies have suggested that insufficient activation of RCC intratumoral NK cells contribute to therapy failure for patients treated with combinations of IL-2, interferon (IFN)-α, and histamine.56,57 Past studies elucidated that these tumor-infiltrating NK cells were unable to lyse target cell lines but could exhibit restored cytolytic activity once reactivated ex vivo. NK-TILs were found to predominantly express functional inhibitory receptors, despite their receptor phenotype resembling that of peripheral NK cells that endogenously should express a more cytolytic receptor repertoire with higher expression of activating receptors.58,59 These phenotypic changes reflect the highly distinct immunosuppressive capacity of RCC by first initiating selective recruitment of NK subsets into tumor tissues and eventually changing the landscape of immune effectors to incapacitated infiltrates.

Recently comprehensive profiling of the immune microenvironment across 33 tumor types revealed 6 immune subtypes. RCC was identified as one of the tumor types in the “inflammatory” C3 subtype, which was associated with the best overall survival (OS) outcomes and with mutations in BRAF, CDH1, and PBRM1. With great insight to the immune microenvironment, this study forms a foundation for immune subtyping and will need to be prospectively validated for each disease type, particularly for applications to immunotherapy CPI response.60 Separately, genomic studies have shown that in a cohort of 35 patients with mRCC treated with nivolumab, those patients harboring PBRM1 loss-of-function mutations had significantly better survival outcomes than those patients with intact PBRM1.29

Although recent work has focused on the role of PBRM1 mutations, the gastrointestinal microbiome, and IFN signaling, there still remains a great clinical need for predictive biomarkers that could potentially predict for responses to immunotherapy CPIs.

Checkpoint Inhibition for mRCC

The paramount abilities of RCC to first induce IC trafficking into the tumor microenvironment, with subsequent deactivation by tolerizing mechanisms, have piqued the interests of those testing immunotherapy CPIs. RCC is a promising immunotherapeutic target for checkpoint inhibition because of the endogenous tendency to draw in several immune effector populations, the relatively high expression of immunosuppressive receptor ligands on tumor cells, and the overactive drive of these tumors to up-regulate immunosuppressive receptors on T lymphocytes and NK cells themselves.

To counter tumor-induced immunosuppression, immunotherapy CPIs aim to disarm the regulatory interaction of programmed cell death receptor 1 (PD-1) and its ligand, PD-L1. PD-1 is a coinhibitory receptor that is expressed by activated T and B lymphocytes. PD-1/PD-L1 interactions have been implicated in the functional impairment of tumor antigen–reactive CD8+ T lymphocytes in solid tumors.61 Specifically, PD-L1 binding to PD-1 reduces IFN-γ production by activated T lymphocytes and leads to T-lymphocyte exhaustion and anergy as well as differentiation of naive CD4+ T lymphocytes into regulatory T lymphocytes (Tregs). The binding of PD-L1 to CD80 also initiates negative signals that inhibit T-cell function and cytokine production.62

The ligand for PD-1, known as B7-H1 (PD-L1, CD274), has been extensively studied in patients with RCC. PD-L1 is aberrantly expressed by both primary and mRCC tumor cells63,64 and is associated with adverse pathology, aggressive tumor behavior, and poor survival.65 PD-L1 expression plays a critical role in downregulating immune responses at least in part by interacting with the inhibitory PD-1 receptor on activated T lymphocytes as well as other ICs.66 Follow-up studies revealed that levels of PD-1 expression are high on immune infiltrates within RCC tumors. Patients’ tumors showing high PD-1+ IC infiltration was also more likely to harbor PD-L1+ tumor cells (95% of patients whose tumors were infiltrated by PD-1+ ICs also contained PD-L1+ tumor cells or ICs).67,69

Another immune checkpoint target is the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) receptor. CTLA-4 (CD152) is a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily and is up-regulated on activated CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes and constitutively expressed on Tregs. CTLA-4 acts as a counterbalance to T-lymphocyte activation through CD28 receptor binding to B7-1 and B7-2 as a competitive inhibitor, which results in the inhibition of T-lymphocyte costimulation cascades and subsequent depressed T-lymphocyte responsiveness.70

As these immune checkpoint receptors and ligands were understood as barriers to effective antitumor immunity, so began the advent of developing monoclonal antibodies to bind these targets and render them incapacitated to tolerize and exhaust the immune system, with the goal of unleashing highly potent and activated T lymphocytes for cytotoxic tumor killing. Immune CPIs can enhance the native immune response against tumor cells by preventing signals that once down-regulated T-lymphocyte activation or potentiated Treg activity. These CPIs include pembrolizumab and nivolumab (PD-1 inhibitors); atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab (PD-L1 inhibitors); and ipilimumab (CTLA-4 inhibitor).

Rationale for Combining Antiangiogenic and Immune-Activating Agents

Further understanding of the interaction between angiogenesis and immune escape has led to trials combining antiangiogenic agents and CPIs. The immune system allows the body to produce new blood vessels in response to hypoxia. This phenomenon is regulated through direct immunosuppression by angiogenic factors and promotion of immune regulatory cells by angiogenesis. Hypoxia triggers the accumulation of HIF-1α, which induces the expression of VEGF, PDGF, and erythropoietin to promote angiogenesis to increase oxygen supply.71 In RCC, inactivation of VHL leads to the accumulation of HIF-1α and thus up-regulate downstream angiogenic pathways.72 HIF-1α also promotes immunosuppressive factors, including PD-L1, and activates inflammatory cells, including myeloid-derived suppressor cells, which promote angiogenesis by secreting VEGF and enhancing immunosuppression, leading to increased tumor growth.73 Indeed, in multiple studies, pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio has been associated with poor prognosis in RCC.74 In summary, the RCC microenvironment is characterized by high levels of angiogenic mediators, chemokines, and ICs that promote tumor growth, while T cells are incapacitated by checkpoint regulation and the immunosuppressive effects of myeloid cells.75

Pazopanib has been shown in vitro to inhibit macrophage expansion and counteract the immunosuppressive activity of VEGF by restoring dendritic-cell immunostimulation.76 Pazopanib has also been shown to enhance PD-1 and PD-L1 expression, increasing the potential responsiveness to PD-1 inhibition. A subgroup analysis of CheckMate 025 showed that patients who received prior pazopanib had an OS not estimable in the nivolumab arm compared to 17.6 months in the everolimus arm.77 This needs to be studied further, but there seems to be a basis for combination or sequential approaches to VEGF inhibition and immunotherapy to exploit the immunomodulatory effects of antiangiogenic agents.

Clinical Data and Approvals for Immunotherapy in mRCC

Nivolumab, the first PD-1 inhibitor approved for solid tumors, showed early efficacy in in phase 1 and 2 studies including mRCC patients.78 Subsequently, the CheckMate 025 trial compared nivolumab and everolimus in the second-line setting, with improved median OS from 19.6 to 25 months (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.73, P = .002) while maintaining a favorable side effect profile.79 Common toxicities associated with nivolumab included fatigue (33%), nausea (14%), pruritus (14%), diarrhea (12%), decreased appetite (12%), and rash (10%); grade 3 or higher toxicities included fatigue (2%), anemia (2%), diarrhea (1%), dyspnea (1%), pneumonitis (1%), hyperglycemia (1%), nausea (< 1%), decreased appetite (< 1%), and rash (< 1%).72 Nivolumab thus gained FDA approval for treatment for VEGF-refractory mRCC in November 2015.

In January 2016, the results of a phase 1a study on atezolizumab, a humanized PD-L1 antibody, in the setting of mRCC were released. In 63 patients with clear-cell mRCC, median OS was 28.9 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 20 to not reached), median PFS was 5.6 months (95% CI, 3.9-8.2), and overall response rate (ORR) of 15% (95% CI, 7-26). The ORR was higher in those with higher PD-L1 tumor-infiltrating IC expression. The 33 patients with IC1/2/3 (> 1% ICs per tumor area stained positive for PD-L1) had an ORR of 18% (95% CI 7-35), compared to the 22 patients with IC0 (< 1% ICs), who had an ORR of 9% (95% CI 1-29). Immune-mediated AEs occurred in 43% of patients (including grade 1 rash in 20% and grade 2 hypothyroidism in 10%). On the basis of this study, atezolizumab was shown to have promising antitumor activity in mRCC with a manageable safety profile.80

Combination immunotherapy with nivolumab and ipilimumab was tested in the phase 3 CheckMate 214 trial. This study randomized 1096 patients with treatment-naive mRCC to combination nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib. Patients were stratified on the basis of IMDC risk criteria. In the intermediate/poor risk group of patients, the median OS was not reached with nivolumab plus ipilimumab compared to 26 months with sunitinib (HR = 0.63, P < .001). In addition, the ORR was 42% for nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus 27% with sunitinib (P < .001), and importantly, the complete response rate was 9% for nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus 1% with sunitinib. Ipilimumab and nivolumab also trended toward improving median PFS from 8.4 months with sunitinib to 11.6 months for nivolumab plus ipilimumab (HR = 0.82, P = .03).13 The majority of patients enrolled onto this study were treated at a time when second-line nivolumab was not yet the standard of care, so the sunitinib-treated patients likely did not have access to an immunotherapy after disease progression. Common grade 3 or higher AEs related to ipilimumab/nivolumab included increased lipase (10%), fatigue (4%), diarrhea (4%), rash, nausea, decreased appetite, and asthenia (1% each).13 The possibility for a complete response in these intermediate/poor risk patients rivals the historical data seen with high-dose IL-2, and therefore ipilimumab/nivolumab has significant disease activity and presents an exciting treatment option for these mRCC patients. Furthermore, there is evidence that PD-L1 is more commonly expressed in intermediate/poor risk mRCC patients, and may help overall predictions of benefit from immunotherapy. In CheckMate 214, PD-L1–positive patients did have a trend toward better survival outcomes with ipilimumab/nivolumab, although this was not statistically significant compared to PD-L1–negative patients.13

In contrast to the results seen in intermediate/poor risk patients, the favorable risk patients in the CheckMate 214 trial revealed a different efficacy profile for nivolumab and ipilimumab compared to sunitinib. Although it was a secondary end point, these patients still accounted for 249 patients treated on the trial. The ORR for this cohort of patients favored sunitinib (52% vs. 29%, P = .0002). In addition, sunitinib was also superior to ipilimumab/nivolumab in median PFS (25.1 vs. 15.3 months, HR = 2.18 favoring sunitinib, P < .0001).13 These results suggest that there is a cohort of patients whose disease may respond better to VEGFR-targeted therapy compared to CPIs, where angiogenesis is a primary driver of disease progression. It will be increasingly important to find a biomarker that can identify angiogenesis-driven disease.

On the basis of data from the CheckMate 214 trial, the ipilimumab/nivolumab combination was approved by the US FDA for intermediate/poor risk mRCC patients in April 2018.

VEGF-Immunotherapy Combinations

As previously discussed, for first-line treatment of mRCC, combination therapy with nivolumab plus ipilimumab has an ORR of approximately 40%,13 while cabozantinib monotherapy has an ORR of approximately 20%.9 On the basis of these data, the majority of patients treated with either immunotherapy or VEGF targeting therapies will not experience objective responses. Given this need for improved therapies, several early-phase trials have completed accrual in combining VEGF-targeting treatments with immunotherapy. In the first-line setting, there have been several notable phase 1 and 2 studies analyzing combination therapy with anti-VEGF therapy and immunotherapy (VEGF/IO), with preliminary data indicating high ORR and disease control rates (DCR) (Table 2).

Table 2. Early Phase Trials in Metastatic Renal-Cell Carcinoma Combining VEGF and Immunotherapy Targeting Strategies.

| Combination | Line of Therapy |

No. of Patients |

ORR (% CR/% PR) |

DCR (CR/PR/SD) (%) |

mPFS (mo) |

Grade 3/4 AE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axitinib–avelumab | First line | 55 | 58% (6/52) | 78 | NA | 58% (32/55) |

| Axitinib–pembrolizumab | First line | 52 | 67% (4/63) | 88 | NA | 65% (34/52) |

| Pazopanib–pembrolizumab | First line | 10 | 60% (20/40) | 100 | NA | 90% (9/10) |

| Lenvatinib–pembrolizumab | After VEGF | 30 | 63% (0/63) | 96 | NA | 70% (21/30) |

| Lenvatinib–pembrolizumab | First line | 12 | 83% (0/83) | 100 | NA | NA |

| Bevacizumab–atezolizumab | First line | 101 | 32% (7/25) | NA | 11.7 | 40% (41/101) |

| Cabozantinib–ipilimumab–nivolumab | After SOC | 42 (GU: UC, RCC, other) | 33% (8/25) | 83 | 5.8 | 71% (30/42) |

Abbreviations: AE = adverse event; CR = complete response; DCR = disease control rate; GU = genitourinary; mPFS = median progression free survival; NA = not available; ORR = objective response rate; PR = partial response; RCC = renal-cell carcinoma; SD = stable disease; SOC = standard of care; UC = urothelial carcinoma; VEGF = vascular endothelial growth factor.

IMmotion 150, a randomized phase 2 study of atezolizumab alone or combined with bevacizumab versus sunitinib, analyzed 305 patients with untreated mRCC. PFS HRs were 1.0 (95% CI, 0.69-1.45) for atezolizumab plus bevacizumab versus sunitinib and 1.19 (95% CI, 0.82-1.71) for atezolizumab monotherapy versus sunitinib. In PD-L1+ populations, defined as ≥ 1% of IC by immunohistochemistry, PFS HRs were 0.64 (95% CI, 0.38-1.08) for atezolizumab plus bevacizumab versus sunitinib and 1.03 (95% CI, 0.63-1.67) for atezolizumab monotherapy versus sunitinib. Treatment-related AEs led to therapy discontinuation in 9% of patients in the combination arm, with proteinuria being the most common cause (5%). Treatment-related grade 3/4 AEs occurred in 40% of patients in the combination arm.

One notable phase 3 trial that builds on the phase 2 data of atezolizumab and bevacizumab is IMmotion 151, which compares atezolizumab plus bevacizumab to sunitinib in the first-line setting. The predefined co–primary end points for this study were PFS in the PD-L1–positive population (predefined P = .04) and OS in all patients (predefined P = .01). The interim analysis showed that IMmotion 151 met its PFS primary end point based on investigator assessment, improving median PFS for atezolizumab plus bevacizumab compared to sunitinib, with an HR value of 0.74 in PD-L1–positive patients (P = .0217) and 0.83 in intention-to-treat patients (P = .0219). In PD-L1–positive patients, the atezolizumab plus bevacizumab group had an ORR of 43% and duration of response that was not reached compared to ORR of 35% and duration of response of 12.9 months for patients treated with sunitinib. Treatment-related grade 3/4 AEs occurred in 40% of patients treated with the combination, with proteinuria being the only grade 3/4 AE that was more common in the combination group.50 While the PFS and ORR data are promising, the trial has yet to report on its second and more critical co–primary end point, OS in all patients. Furthermore, independent review of PFS in PD-L1–positive patients did not show a statistical difference between the treatment arms (HR = 0.93, 95% CI 0.72-1.21).81 In light of this discordance, the definitive OS data will be important to assess treatment efficacy.

Exploration of the gene expression signatures that correlate with clinical responses in the phase 2 IMmotion 150 trial led to distinct molecular subgroups based on expression of angiogenesis, T-effector/IFN-γ response, and myeloid inflammatory gene expression. Highly angiogenic tumors were associated with improved ORR (46% in angiogenesishigh vs. 9% in angiogenesislow) and PFS (HR = 0.31; 95% CI, 0.18-0.55) in the sunitinib arm, but not across treatment arms. The presence of a preexisting immune response, based on high expression of the T-effector gene signature, showed improved ORR (49% in T-effectorhigh vs. 16% in T-effectorlow) and PFS (HR = 0.5; 95% CI, 0.3-0.86) in the atezolizumab plus bevacizumab arm, and high T-effector gene signature expression was associated with improved PFS with atezolizumab plus bevacizumab compared to sunitinib (HR = 0.55; 95% CI, 0.31-0.95). These findings suggest that it may be possible to predict response to anti-VEGF and immunotherapy combination treatment on the basis of gene expression signatures—an important correlative biomarker to differentiate responses to VEGF versus immunotherapy treatments.81

Combination therapy with axitinib and pembrolizumab demonstrated 67% ORR and 88% DCR.82 The Javelin Renal 100 study analyzed 55 patients who received axitinib and avelumab, with data demonstrating an ORR of 58% and DCR of 78%.83 In addition, initial reports of a phase 2 study of pazopanib and pembrolizumab showed an ORR of 60% and DCR of 100%.84 An additional early-phase study evaluating lenvatinib and pembrolizumab after VEGF therapy showed an ORR of 63% and DCR of 96%.85 The majority of patients treated with lenvatinib/pembrolizumab had tumor shrinkage with partial or complete responses. Another study, which included patients with all types of genitourinary cancer who had received at least one line of standard therapy, analyzed triple therapy with cabozantinib plus ipilimumab and nivolumab, and showed an ORR of 33% and DCR of 83%.86 Grade 3/4 AEs occurred in 40% to 90% of patients treated with combination therapies (Table 2). Results from these early trials have shown promise that VEGF/IO combination therapy could be a viable treatment option in the future with likely significant toxicity and for select patients, pending the results of pivotal phase 3 trials.

There are now multiple phase 3 trials building off the initial early-phase studies, using combinations of avelumab/ axitinib (ClinicalTrials.gov ), pembrolizumab/lenvatinib (ClinicalTrials.gov ), pembrolizumab/axitinib (ClinicalTrials.gov ), and nivolumab/cabozantinib (ClinicalTrials.gov ), all compared to sunitinib in the first-line setting (Table 3). The phase 3 trial with combination of avelumab with axitinib was the first to be reported, improving median PFS from 8.4 months for sunitinib to 13.8 months with avelumab/axitinib (HR = 0.69, 95% CI 0.56-0.84, P = .0001). Avelumab/axitinib also showcased a high DCR of 81%, with objective response rate of 51%, including 3% complete responses. Most common grade 3/4 treatment-related AEs for avelumab/axitinib included hypertension (24%), hand–foot syndrome (6%), diarrhea (5%), and increased alanine aminotransferase (4%), with 1% overall grade 3/4 immune-mediated AEs, including 4 patients who developed immune-mediated hepatitis.87 These results show a good tolerability profile for these agents, with promising disease control and objective response rate. This and other phase 3 trials will likely provide further evidence supporting the use of combination VEGF/IO therapy in the first-line setting; however, careful correlative studies to select the appropriate patients will be necessary to understand who will benefit the most from up-front combination therapies.

Table 3. Ongoing Phase 3 First-Line Trials of Metastatic Renal-Cell Carcinoma With VEGF and Immunotherapy Combinations.

| Treatment Arm | Control Arm | Primary End Point | Trial | ClinicalTrials.gov |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lenvatinib/pembrolizumab vs. everolimus/lenvatinib | Sunitinib | PFS | Clear | |

| Bevacizumab/atezolizumab | Sunitinib | PFS in PD-L1 positive; OS in all patients | IMmotion 151 | |

| Axitinib/avelumab | Sunitinib | PFS | Javelin Renal 101 | |

| Axitinib/Pembrolizumab | Sunitinib | PFS and OS | Keynote 426 | |

| Cabozantinib/nivolumab | Sunitinib | PFS | CheckMate 9ER |

Abbreviations: OS = overall survival; PD-L1 = programmed death ligand 1; PFS = progression-free survival.

On the basis of preliminary data from the above studies, VEGF/IO combination therapy has shown higher response rates than VEGF or immunotherapy monotherapy. These data support the hypothesis that VEGF inhibitors likely augment the responses seen with immunotherapy agents alone; however, a critical question is whether these responses will translate into better OS or similar OS with reduced toxicity compared to ipilimumab/nivolumab. Further data from phase 3 trials may change the standard of care in first-line mRCC. Certainly if complete response rates or OS improve dramatically with VEGF/IO combination therapy, these combination therapies may provide significant alternative options for these extremely ill patients, as long as treatment is tolerable. Grade 3 toxicities are higher in combination therapies, and the ongoing phase 3 trials will be informative to see how AE profiles compare to standard-of-care treatment.

Given the toxicity of VEGF/IO combination therapy and the lack of predictive biomarkers, selecting patients most likely to benefit from VEGF/IO combination therapy has been difficult. The molecular subgroups and gene expression signatures found in IMmotion 150 were subsequently validated in the phase 3 IMmotion 151 trial, showing angiogenesishigh and T-effectorhigh, and myeloid inflammation signatures. Angiogenesishigh patients had preferential responses to sunitinib with improvement in median PFS of 10.1 versus 5.9 months (HR = 0.59, 95% CI 0.47-0.75). Similarly, the T-effectorhigh cohort had improved responses to atezolizumab/bevacizumab compared to sunitinib, with median PFS of 12.5 versus 8.34 months (HR = 0.76, 95% CI 0.59-0.99).88 These data highlight the importance of tumor biology and the future potential of using gene expression signatures as biomarkers to select first-line treatments in mRCC.

One pertinent clinically relevant question remains, however, and that is how to optimally sequence therapies for patients who experience disease progression while receiving VEGF/IO combination therapy. In addition, cross-trial comparisons are not definitive, and the mRCC field needs both head-to-head studies to compare treatments for efficacy and toxicity as well as prospective real-world data for compliance and tolerance of these novel treatments and combination therapies. Future trials that integrate VEGF therapy early after combination immunotherapy may further improve outcomes while balancing treatment toxicities and quality-of-life priorities for patients. Clinically validating biomarkers (such as PD-L1 expression and PBRM1 loss) will also be critical to aid in treatment selection for these patients. Given mRCC’s heterogeneity, there may be several pathways in the future for selecting treatment based on clinical presentation, patient preference, and best practices for sequencing treatments.

Conclusion

RCC is a common malignancy with increasing prevalence, and a large number of patients present with disease in advanced stages. With a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying RCC, the arsenal of treatment options for mRCC has rapidly evolved, from anti-VEGF therapy with pazopanib and sunitinib, newer VEGF/MET/AXL targeting therapy with cabozantinib, the addition of immunotherapy with first nivolumab and then combination nivolumab plus ipilimumab, and likely in the near future the emergence of combination anti-VEGF therapies with immunotherapy. With the early results of phase 3 first-line VEGF/IO combination clinical trials starting to be reported, the list of FDA-approved regimens should continue to expand.

This review has highlighted the current first-line treatment landscape for mRCC. The emergence of newer agents including cabozantinib and immunotherapy CPIs has shifted the paradigm for first-line treatment of mRCC. Studies of the combination of immunotherapies and antiangiogenesis agents have preliminarily shown promising data, and this combination has the potential to dramatically improve patient outcomes. Further investigation will be important to discover selecting the optimal therapeutic regimen and sequencing for patients with mRCC.

Footnotes

Disclosure

A.J.A. has received funding (to Duke) from Medivation/Astellas, Bayer, Dendreon, Janssen, Active Biotech, Sanofi-Aventis, Gilead, Novartis, and Pfizer; consulting/speaking with Dendreon and Sanofi Aventis; and consulting with Medivation/Astellas and Janssen. D.J.G. has received research funding (to Duke) from Acerta, Astellas, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dendreon, Exelixis, Innocrin, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer; consulting and speaking with Bayer, Exelixis, Sanofi; and consulting with Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Innocrin, Janssen, Merck, Myovant, Pfizer. T.Z. has received research funding (to Duke) from Pfizer, Janssen, Acerta, Abbvie, Novartis, Merrimack, OmniSeq, PGDx, and Merck; consulting/speaking with Genentech Roche and Exelixis; consulting with AstraZeneca, Amgen, Pharmacyclics, BMS, Pfizer, Foundation Medicine, Janssen, Bayer, and Sanofi Aventis; and stock ownership/employment (spouse) from Capio Biosciences. M.M. has received research funding (to Duke) from Janssen, Agensys, Bayer, Seattle Genetics, and Clovis. The other authors have stated that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin 2015; 65:5–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Motzer RJ, Agarwal N, Beard C, et al. Kidney cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2011; 9:960–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fisher R, Gore M, Larkin J. Current and future systemic treatments for renal cell carcinoma. Semin Cancer Biol 2013; 23:38–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Climent MA, Munoz-Langa J, Basterretxea-Badiola L, et al. Systematic review and survival meta-analysis of real world evidence on first-line pazopanib for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2018; 121:45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vachhani P, George S. VEGF inhibitors in renal cell carcinoma. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol 2016; 14:1016–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975-2014, National Cancer Institute. Available at: https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2014/. Accessed: February 13, 2019.

- 7.Heng DY, Xie W, Regan MM, et al. Prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted agents: results from a large, multicenter study. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27:5794–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN categories of evidence and consensus. Category 1, Available at:https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/categories_of_consensus.aspx. Accessed: February 13, 2019.

- 9.Choueiri TK, Halabi S, Sanford BL, et al. Cabozantinib versus sunitinib as initial targeted therapy for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma of poor or intermediate risk: the Alliance A031203 CABOSUN Trial. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35:591–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armstrong AJ, Halabi S, Eisen T, et al. Everolimus versus sunitinib with metastatic non-clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ASPEN): a multicenter, open-label, radomised phae 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17:378–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tannir NM, Jonasch E, Albiges L, et al. Everolimus versus sunitinib prospective evaluation in metastatic non-clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ESPN): a randomized multicenter phase 2 trial. Eur Urol 2016; 69:866–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hudes G, Carducci M, Tomczak P, et al. Temsirolimus, interferon alfa, or both for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2007; 356:2271–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Motzer RJ, Tannir NM, McDermott DF, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2018; 378:1277–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Srinivasan R, Ricketts CJ, Sourbier C, et al. New strategies in renal cell carcinoma: targeting the genetic and metabolic basis of disease. Clin Cancer Res 2015; 21:10–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nickerson ML, Jaeger E, Shi Y, et al. Improved identification of von Hippel-Lindau gene alterations in clear cell renal tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2008; 14:4726–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang JC, Haworth L, Sherry RM, et al. A randomized trial of bevacizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth receptor antibody, for metastatic renal cancer. N Engl J Med 2003; 349:427–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Escudier B, Pluzanska A, Koralewski P, et al. Bevacizumab plus interferon alfa-2a for treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a randomized, double-blind phase III trial. Lancet 2007; 370:2103–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rini BI, Halabi S, Rosenberg JE, et al. Phase III trial of bevacizumab plus interferon alfa versus interferon alpha monotherapy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28:2137–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM, et al. Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2007; 356:125–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, et al. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2007; 356:115–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sternberg CN, Davis ID, Mardiak J, et al. Paropanib in locally advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results of a randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28:1061–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Cella D, et al. Pazopanib versus sunitinib in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2013; 369:722–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choueiri TK, Escudier B, Powles T, et al. Cabozantinib versus everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma (METEOR): final results from a randomized, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17:917–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choueiri TK, Hessel C, Halabi S, et al. Cabozantinib versus sunitinib as initial therapy for metasttic renal cell carcinoma of intermediate or poor risk (Alliance A031203 CABOSUN randomised trial): profression-free survival by independent review and overall survival update. Eur J Cancer 2018; 94:115–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burris HA. Overcoming acquired resistance to anticancer therapy: focus on the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2013; 71:829–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fyfe G, Fisher RI, Rosenberg SA, et al. Results of treatment of 255 patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma who received high-dose recombinant interleukin-2 therapy. J Clin Oncol 1995; 13:688–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clark JI, Wong MK, Kaufman HL, et al. Impact of sequencing targeted therapies with high-dose Interleukin-2 immunotherapy: an analysis of outcome and survival of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma from an on-going observational IL-2 clinical trial: PROCLAIMSM. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2017; 15:31–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen L, Flies DB. Molecular mechanism of T cell co-stimulation and co-inhibition. Nat Rev Immunol 2013; 13:227–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miao D, Margolis CA, Gao W, et al. Genomic correlates of response to immune checkpoint therapies in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Science 2018; 359:801–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vetizou M, Pitt JM, Daillere R, et al. Anticancer immunotherapy by CTLA-4 blockade relies on the gut microbiota. Science 2015; 350:1079–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sivan A, Corrales L, Hubert N, et al. Commensal bifidobacterium promotes antitumor immunity and facilitates anti-PD-L1 efficacy. Science 2015; 350:1084–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Routy B, Le Chatelier E, Derosa L, et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-baed immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science 2018; 359:91–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Derosa L, Hellmann MD, Spaziano M, et al. Negative association of antibiotics on clinical activity of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with advanced renal cell and non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol 2018; 29:1437–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Griffiths RW, Elkord E, Gilham DE, et al. Frequency of regulatory T cells in renal cell carcinoma patients and investigation of correlation with survival. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2007; 56:1743–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kang MJ, Kim KM, Bae JS, et al. Tumor-infiltrating PD1-positive lymphocytes and FoxP3-poositive regulatory T cells predict distant metastatic relapse and survival of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Transl Oncol 2013; 6:282–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li JF, Chu YW, Wang GM, et al. The prognostic value of peritumoral regulatory T cells and its correlation with intratumoral cyclooxygenase-2 expression in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. BJU Int 2009; 103:399–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liotta F, Gacci M, Frosali F, et al. Frequency of regulatory T cells in peripheral blood and in tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes correlates with poor prognosis in renal cell carcinoma. BJU Int 2011; 107:1500–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Asma G, Amal G, Raja M. Comparison of circulating and intratumoral regulatory T cells in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Tumour Biol 2015; 36:3727–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Siddiqui SA, Frigola X, Bonne-Annee S, et al. Tumor-infiltrating Foxp3-CD4+CD25+ T cells predict poor survival in renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2007; 13:2075–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bromwich EJ, McArdle PA, Canna K, et al. The relationship between T-lymphocyte infiltration, stage, tumour grade and survival in patients undergoing curative surgery for renal cell cancer. Br J Cancer 2003; 89:1906–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choueiri TK, Figueroa DJ, Fay AP. Correlation of PD-L1 tumor expression and treatment outcomes in patients with renal cell carcinoma receiving sunitinib or pazopanib: results from COMPARZ, a randomized controlled trial. Clin Cancer Res 2015; 21:1071–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Giraldo NA, Becht E, Pages F, et al. Orchestration and prognostic significance of immune checkpoints in the microenvironment of primary and metastatic renal cell cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2015; 21:3031–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Remark R, Alifano M, Cremer I, et al. Characteristics and clinical impacts of the immune environments in colorectal and renall cell carcinoma lung metastases: influence of tumor origin. Clin Cancer Res 2013; 19:4079–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakano O, Sato M, Naito Y, et al. Proliferative activity of intratumoral CD8(+) T-lymphocytes as a prognostic factor in human renal cell carcinoma: clinicopathologic demonstration of antitumor immunity. Cancer Res 2001; 61:5132–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weiss JM, Gregory AW, Quinones OA, et al. CD40 expression in renal cell carcinoma is associated with tumor apoptosis, CD8(+) T cell frequency and patient survival. Hum Immunol 2014; 75:614–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jordanova ES, Gorter A, Ayachi O, et al. Human leukocyte antigen class I, MHC class I chain-related molecule A, and CD8+/regulatory T-cell ratio: which variable determines survival of cervical cancer patients? Clin Cancer Res 2008; 14:2028–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sato E, Olson SH, Ahn J, et al. Intraepithelial CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and a high CD8+/regulatory T cell ratio are associated with favorable prognosis in ovarian cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005; 102:18538–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Posselt R, Erlenbach-Wunsch K, Haas M, et al. Spatial distribution of FoxP3+ and CD8+ tumour infiltrating T cells reflects their functional activity. Oncotarget 2016; 7:60383–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu H, Zhang T, Ye J, et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes predict response to chemotherapy in patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2012; 61:1849–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Motzer RJ, Powles T, Atkins MB, et al. IMmotion 151: a randomized phase III study of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab vs sunitinib in untreated metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC). J Clin Oncol 2018; 36(6 suppl):578. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wierecky J, Muller MR, Wirths S, et al. Immunologic and clinical response after vaccinations with peptide-pulsed dendritic cells in metastatic renal cancer patients. Cancer Res 2006; 66:5910–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cozar JM, Canton J, Tallada M, et al. Analysis of NK cells and chemokine receptors in tumor infiltrating CD4 T lymphocytes in human renal carcinomas. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2005; 54:858–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Donskov F, von der Maase H. Impact of immune parameters on long term survival in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24:1997–2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kowalcyzk D, Skorupski W, Kwias Z, et al. Flow cytometric analysis of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Br J Urol 1997; 80:543–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schleypen JS, Baur N, Kammerer R, et al. Cytotoxic markers and frequency predict functional capacity of natural killer cells infiltrating renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2006; 12(3 pt 1):718–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Donskov F, Bennedsgaard KM, Von Der Maase H, et al. Intratumoral and peripheral blood lymphocytes subsets in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma undergoing interleukin-2 based immunotherapy: association to objective response and survival. Br J Cancer 2002; 87:194–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Toliou T, Stravoravdi P, Polyzonis M, et al. Natural killer cell activation after interferon administration in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: an ultrastructural and immunohistochemical study. Eur Urol 1996; 29:252–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schleypen JS, Von Geldern M, Weiss EH, et al. Renal cell carcinoma-infiltrating natural killer cells express differential repertoires of activating and inhibitory receptors and are inhibited by specific HLA class I allotypes. Int J Cancer 2003; 106:905–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gati A, Da Rocha A, Guerra N, et al. Analysis of the natural killer mediated immune response in metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients. Int J Cancer 2004; 109:393–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thorsson V, Gibbs DL, Brown SD, et al. The immune landscape of cancer. Immunity 2018; 48:812–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Parry RV, Chemnitz JM, Frauwirth KA, et al. CTLA-4 and PD-1 receptors inhibit T-cell activation by distinct mechanisms. Mol Cell Biol 2005; 25:9543–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bardhan K, Anagnostou T, Boussiotis VA. The PD1:PD-L1/2 pathway from discovery to clinical implementation. Front Immunol 2016; 7:550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thompson RH, Gillett MD, Cheville JC, et al. Costimulatory B7-H1 in renal cell carcinoma patients: indicator of tumor aggressiveness and potential therapeutic target. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004; 101:17174–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thompson RH, Gillett MD, Cheville JC, et al. Costimulatory molecule B7-H1 in primary and metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer 2005; 104:2084–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thompson RH, Kuntz SM, Leibovich BC, et al. Tumor B7-H1 is associated with poor prognosis in renal cell carcinoma patients with long-term follow up. Cancer Res 2006; 66:3381–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Thomspon RH, Dong H, Lohse CM, et al. PD-1 is expressed by tumor-infiltrating immune cells and is associated with poor outcomes for patients with renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2007; 13:1757–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Herbst RS, Soria JC, Kowanetz M, et al. Predictive correlates of response to the anti-PD-L1 antibody MPDL3280A in cancer patients. Nature 2014; 515:563–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thompson RH, Dong H, Kwon ED. Implications of B7-H1 expression in clear cell carcinoma of the kidney for prognostication and therapy. Clin Cancer Res 2007; 13(2 pt 2):709s–15s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thompson RH, Webster WS, Cheville JC, et al. By-H1 glycoprotein blockade: a novel strategy to enhance immunotherapy in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Urology 2005; 66(5 suppl):10–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Walunas TL, Bakker CY, Bluestone JA. CTLA-4 ligation blocks CD28-dependent T cell activation. J Exp Med 1996; 183:2541–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Majeed R, Hamid A, Qurishi Y, Qazi A, Hussain A, Ahmed M. Therapeutic targeting of cancer cell metabolism: role of metabolic enzymes, oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. J Cancer Sci Ther 2012; 4:281–91. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cowey CL, Rathmell WK. VHL gene mutations in renal cell carcinoma: role as a biomarker of disease outcome and drug efficacy. Curr Oncol Rep 2009; 11:94–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kumar V, Patel S, Tcyganov E, Gabrilovich DI. The nature of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment. Trends Immunol 2016; 37:208–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hu K, Lou L, Ye J, Zhang S. Prognostic role of the neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in renal cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2015; 5:e006404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bracarda S, Porta C, Sabbatini R, et al. Angiogenic and immunological pathways in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a counteracting paradigm or two faces of the same medal? The GIANUS Review [e-pub ahead of print], Crit Rev Oncol, 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2018.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Unnikrishnan R, Rayman P, Yang Y, Diaz-Montero CM, Finke J. Pazopanib, sunitinib, and axitinib reduce expansion of in vitro induced suppressive macrophages. J Urol 2015; 193:e712 (abstract PD33-08). [Google Scholar]

- 77.Motzer RJ, Sharma P, McDermott DF, et al. CheckMate 025 phase III trial: outcomes by key baseline factors and prior therapy for nivolumab (NIVO) versus everolimus (EVE) in advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC). J Clin Oncol 2016; 34(suppl 2S):498. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti–PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:2443–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF, et al. Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:1803–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.McDermott DF, Sosman JA, Sznol M, et al. Atezolizumab, an anti-programmed death-ligand 1 antibody, in metastatic renall cell carcinoma: long-term safety, clinical activity, and immune correlates from a phase Ia study. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34:833–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McDermott DF, Huseni MA, Atkins MB, et al. Clinical activity and molecular correlated of response to atezolizumab alone or in combination with bevacizumab versus sunitinib in renal cell carcinoma. Nat Med 2018; 24:s749–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Atkins MB, Plimack ER, Puzanov I, et al. Axitinib in combination with pembrolizumab in patients with advanced renal cell cancer: a non-randomised, open-label, dose-finding and dose-expansion phase 1b trial. Lancet Oncol 2018; 19:405–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Choueiri TK, Larkin JM, Oya M, et al. First-line avelumab + axitinib therapy in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma: results from a phase Ib trial. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35(suppl 15):4504. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chowdhury S, McDermott DF, Voss MH, et al. A phase I/II study to assess the safety and efficacy of pazopanib and pembrolizumab in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35(suppl 15):4506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lee C, Makker V, Rasco D, et al. A phase 1b/2 trial of lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol 2017; 28(suppl 5):v295–329. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nadal RM, Mortazavi A, Stein M, et al. Results of phase I plus expansion cohort of cabozantinib plus nivolumab and CaboNivo plus ipilimumab in patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma and other genitourinary malignancies. J Clin Oncol 2018; 36(suppl 6):515.29267131 [Google Scholar]

- 87.Motzer RJ, Penkov K, Haanen J, et al. Avelumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2019. 10.1056/NEJMoa1816047. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rini BI, Huseni M, Atkins MB, et al. Molecular correlates differentiate responses to atezolizumab + bevacizumab vs sunitinib: results from a phase III study (IMmotion 151) in untreated renal cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol 2018; 29(suppl 8):LBA31. [Google Scholar]