Abstract

Introduction:

Prevention and treatment of pain in pediatric patients compared with adults is often not only inadequate but also less often implemented the younger the children are. Children 0 to 17 years are a vulnerable population.

Objectives:

To address the prevention and treatment of acute and chronic pain in children, including pain caused by needles, with recommended analgesic starting doses.

Methods:

This Clinical Update elaborates on the 2019 IASP Global Year Against Pain in the Vulnerable “Factsheet Pain in Children: Management” and reviews best evidence and practice.

Results:

Multimodal analgesia may include pharmacology (eg, basic analgesics, opioids, and adjuvant analgesia), regional anesthesia, rehabilitation, psychological approaches, spirituality, and integrative modalities, which act synergistically for more effective acute pediatric pain control with fewer side effects than any single analgesic or modality. For chronic pain, an interdisciplinary rehabilitative approach, including physical therapy, psychological treatment, integrative mind–body techniques, and normalizing life, has been shown most effective. For elective needle procedures, such as blood draws, intravenous access, injections, or vaccination, overwhelming evidence now mandates that a bundle of 4 modalities to eliminate or decrease pain should be offered to every child every time: (1) topical anesthesia, eg, lidocaine 4% cream, (2) comfort positioning, eg, skin-to-skin contact for infants, not restraining children, (3) sucrose or breastfeeding for infants, and (4) age-appropriate distraction. A deferral process (Plan B) may include nitrous gas analgesia and sedation.

Conclusion:

Failure to implement evidence-based pain prevention and treatment for children in medical facilities is now considered inadmissible and poor standard of care.

Keywords: Pediatric pain, Pain treatment, Pain prevention, Multimodal analgesia, Topical anesthesia, Comfort positioning, Sucrose, Breastfeeding, Distraction

Key Points

According to the 2010 Declaration of Montreal, access to pain management is a fundamental human right and it is a human rights violation not to treat pain

Evidence-based pain prevention and treatment must become a priority for all medical facilities providing pediatric care

Effective multimodal analgesia for acute pain act synergistically for more effective pediatric pain control with fewer side effects than single analgesic or modality and includes pharmacology (eg, basic analgesia, opioids, and adjuvant analgesia), regional anesthesia, rehabilitation, psychology, spirituality, and integrative (“nonpharmacological”) modalities.

For chronic persistent pediatric pain, an interdisciplinary rehabilitative approach including (1) physical therapy, (2) psychological interventions, (3) active integrative mind–body techniques, and (4) normalizing life (eg, school, sleep, social, and sports) has been shown most effective.

Opioids are usually not indicated in chronic pain in the absence of new tissue injury.

For elective needle procedures, evidence now mandates to consistently offer 4 strategies to every child every time: (1) topical anesthetics, (2) sucrose or breastfeeding for infants 0 to 12 months, (3) comfort positioning (including swaddling, skin-to-skin contact, or facilitated tucking for infants, sitting upright for children), and (4) age-appropriate distraction.

1. Introduction

Data from children's hospitals around the world reveal that pain in pediatric patients from infancy to adolescence is common, under-recognized and undertreated.6,48,144,148,162,170,179 Compared with adult patients, pediatric patients with the same diagnoses receive less analgesic doses, and the younger the children are, the less likely it is that they receive adequate analgesia in the medical setting.5,9,117,137

The pain experienced by children in a hospital, medical facility, or doctor's office can be disease- and/or treatment-related and may be based on one, several, or all of the following pathophysiologies:

(1) Acute somatic pain (eg, tissue injury), which arises from the activation of peripheral nerve endings (nociceptors) that respond to noxious stimulation [and may be described as localized, sharp, squeezing, stabbing, or throbbing].

(2) Neuropathic pain, resulting from injury to, or dysfunction of, the somatosensory system [burning, shooting, electric, or tingling]. Central pain would be caused by a lesion or disease of the central somatosensory nervous system.

(3) Visceral pain results from the activation of nociceptors of the thoracic, pelvic, or abdominal viscera [poorly localized, dull, crampy, or achy].

(4) Total pain: suffering that encompasses all of a child's physical, psychological, social, spiritual, and practical struggles134

(5) Chronic (or persistent) pain: pain beyond expected time of healing

A particularly vulnerable group of patients are infants and neonates. A recent systematic review showed that neonates admitted to intensive care units frequently suffer through an average of 7 to 17 painful procedures per day, with the most frequent procedures being venipuncture, heel lance, and insertion of a peripheral venous catheter.2 In most infants no analgesic strategies are used.135 In addition, children with serious medical conditions are exposed to frequent painful diagnostic and therapeutic procedures (eg, bone marrow aspirations, lumbar punctures, and wound dressing changes). Furthermore, even healthy children have to undergo significant amounts of painful medical procedures throughout childhood: Vaccinations are the most commonly performed needle procedure in childhood, and pain is a common reason for vaccine hesitancy.32,90,156

Exposure to severe pain in infants without adequate pain management has negative long-term consequences, including increased morbidity (eg, intraventricular hemorrhage) and mortality.2,152 Exposure to pain in premature infants is associated with higher pain self-ratings during venipuncture by school age172 and poorer cognition and motor function.66 Research has also shown that exposure to pain early in life even heightens the risk for developing problems in adulthood (chronic pain, anxiety, and depressive disorders), implying that adequate management of infant and child pain is imperative.8,74,177

This Clinical Update, building on the Factsheet Pain in Children: Management. 2019 Global Year against Pain in the Vulnerable of the International Association for the Study of Pain [IASP],59 which have been translated into 18 languages so far, will address the prevention and treatment of the 3 most common pain entities in pediatric medicine: acute pain, chronic pain, and needle pain.

2. Prevention and treatment of acute pain in children

Acute nociceptive pain might be due to tissue injury caused by disease, trauma, surgery, interventions, and/or disease-directed therapy. Untreated acute pain may lead to fear and even avoidance of future medical procedures.

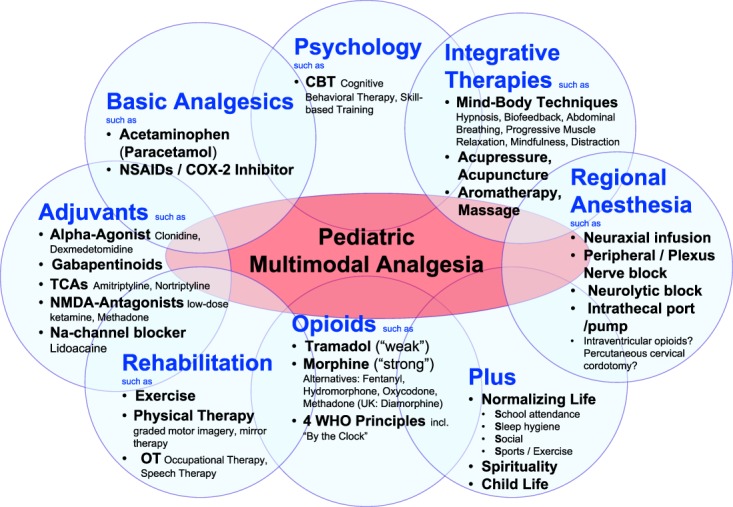

Multimodal analgesia (Fig. 1) is the current recommended approach to address acute pain in hospitalized children. Pharmacology (including basic analgesia, opioids, and adjuvant analgesia) alone might not be sufficient to treat children with acute pain. The addition and integration of modalities such as regional anesthesia, rehabilitation, effective psychosocial interventions, spirituality, and integrative (“nonpharmacological”) modalities acts synergistically for more effective (opioid-sparing) pediatric pain control with fewer side effects than single analgesic or modality.55

Figure 1.

Pediatric Multimodal Analgesia: Implementing some or, depending on the clinical scenario, all modalities in the treatment of acute pain acts synergistically for more effective (opioid-sparing) pediatric pain control with fewer side effects than single analgesic or modality.

2.1. Treat underlying disease process

Pain is foremost a symptom and might be a warning sign. After a detailed medical history, clinical examination, and potentially further workup (including imagery or laboratory investigations), an underlying disease process (such as tissue injury including infection, and trauma) needs to be addressed as appropriate in the specific clinical scenario to avoid further harm. As an example, in a child with increasing foot pain after orthopedic surgery, the primary intervention would be to rule out and address a potential compartment syndrome, and not simply to increase the analgesic dose.

2.2. Basic analgesia

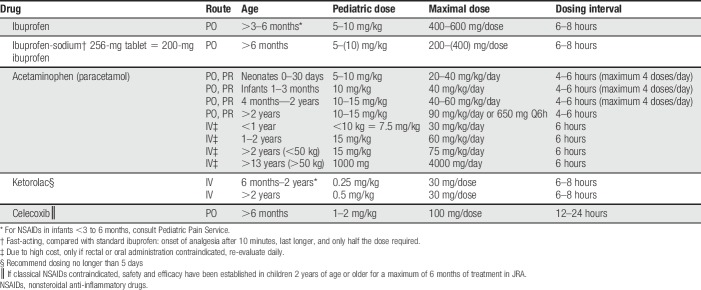

Basic (or “simple”) analgesia usually includes acetaminophen (paracetamol) and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Data have shown that ibuprofen-sodium (available over-the-counter in the United States and other countries) compared with standard ibuprofen has a faster analgesic onset (within 10 minutes), only requires 50% of the dose, and has a longer duration of action.116 If NSAIDs are contraindicated due to their side-effect profile (which includes bleeding risk and gastrointestinal side effects), one may consider a COX-2 inhibitor (eg, celecoxib).163 The renal toxicity profile may be somewhat better compared with classic NSAIDs.118 For starting doses, see Table 1. Although in some countries dipyrone (metamizole) is commonly used as a basic analgesic, it is not available in many countries, including the United States.

Table 1.

Basic analgesia for children.

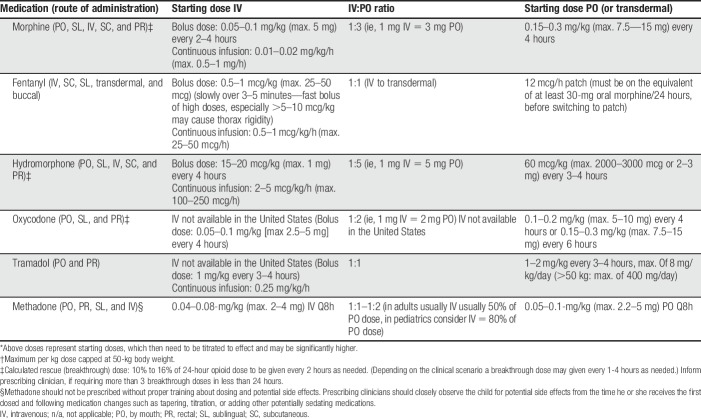

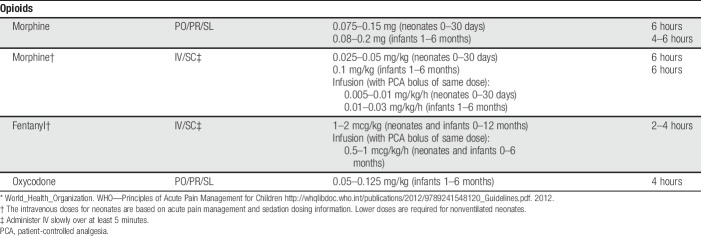

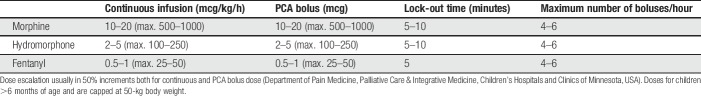

2.3. Opioids

Opioids are often indicated for medium to severe acute pain due to tissue injury. The World Health Organization (WHO) step 2 suggests opioid use in children with persisting medium–severe pain due to medical illness in addition to basic analgesia (and not waiting for the effect of acetaminophen or an NSAID).180 Morphine remains the “gold standard,” but other “strong” opioids, such as fentanyl, oxycodone, hydromorphone, diamorphine (in the United Kingdom only), and methadone are equally effective in their respective analgesic effects. For opioid starting doses, see Table 2; for neonates, Table 3; and for usual patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pump starting doses, see Table 4.

Table 2.

Opioid analgesics: usual starting doses for children with acute pain (>6 months).*,†

Table 3.

Opioid analgesia for neonates and infants 0–6 months of age.*

Table 4.

Usual starting doses for patient (or nurse)-controlled analgesia (PCA) pumps for children in acute pain (>6 months).

“Weak” opioids, with an analgesic ceiling effect, include codeine, which cannot be recommended anymore due to pediatric deaths, especially in cytochrome P450 2D6 ultrarapid metabolizers.22,24,38,47,49,88,94 Tramadol, a multimechanistic analgesic, however, seems to continue playing a key role not only in outpatient surgery (eg, more than 6,000 pediatric tramadol scripts were filled at Children's Minnesota in 2018 in part due to its relative respiratory safety profile), but also in treating episodes of inconsolability in children with progressive neurologic, metabolic, or chromosomally based conditions with impairment of the central nervous system. Surprisingly, and not well based on scientific evidence, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a warning against pediatric use of tramadol and cited the data of 3 children who have died worldwide in the previous 49 years, therefore actually making it far safer than any other opioid. Unfortunately, this warning may place children at greater risk for unrelieved pain and other distressing symptoms by encouraging clinicians to either use strong opioids in the outpatient setting with a higher risk of respiratory depression or not use opioids at all.54

“By the clock”: when pain is constantly present, both administration of basic analgesia and opioid should usually be scheduled “around the clock” (eg, acetaminophen every 6 hours scheduled and/or morphine every 4 hours scheduled). As-needed prescriptions only (without scheduled analgesia) often do not reach the patient, and “PRN” (“pro re nata” or “as-needed”) is often translated into “patient receives nothing”, with 69 percent of hospitalized pediatric patients for whom analgesics had been ordered “PRN” did not receive a single dose in one study.79

2.4. Adjuvant analgesia

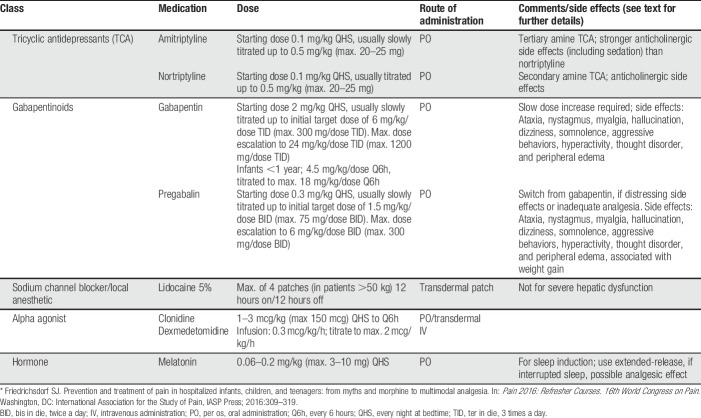

Adjuvant analgesics may improve pain control either in addition to basic analgesia and/or opioids, or they may also act as primary analgesics, especially in neuropathic and visceral pain treatment.41,45 This heterogenic group includes gabapentinoids33,68 (such as gabapentin and pregabalin), alpha-2-adrenergic agonists10,23,78 (such as clonidine or dexmedetomidine), low-dose tricyclic antidepressants (such as amitriptyline or nortriptyline), N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) channel blockers (such as low-dose ketamine40,86), and sodium-channel blockers (such as lidocaine39,109,127,139,178). See Table 5 for dosing recommendations.

Table 5.

Adjuvant analgesics used in pediatric pain management.*

Cannabis and medical marijuana (including cannabidiol [CBD] and tetrahydrocannabinol [THC]) lack any evidence to support its use for treatment of acute or chronic pain.29,76 The updated American Academy of Pediatrics policy opposes marijuana use,126 citing lack of research and potential harms including correlation with mental illness,19 testicular cancer,28,97,167 decline in IQ,113,115 and increased risk of addiction.114 In our clinical practice, we do not support the use of marijuana (or medical cannabis) for a child with a primary pain disorder and a normal life expectancy. However, in children with life-limiting conditions, the administration of medical cannabis might be requested by patients and their parents and certainly may be considered on a case-by-case basis. It is important to watch carefully for side effects (including pancreatitis and psychosis).

2.5. Integrative medicine

Many integrative medicine (other terms used may include “nonpharmacologic,” “complementary,” or “alternative medicine”) modalities seem very effective in treating and preventing pediatric acute pain. In infants, these modalities include breastfeeding, non-nutritive sucking with sucrose 24%, and skin-to-skin contact.21,56,141,149 In toddlers, school children's and young adults' age-appropriate effective integrative modalities include distraction, deep breathing, biofeedback, self-hypnosis, yoga, acupuncture, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation and massage.12,35–37,44,46,81,96,133,171,173,175,181 Many active mind-body techniques, such as guided imagery, hypnosis, biofeedback, yoga, and distraction may result in pain reduction through involvement of several mechanisms simultaneously within the analgesic neuraxis.3,36,93,95,151

2.6. Psychological interventions

Anxiety, depression, catastrophizing thoughts about pain, and behavioral disorders represent risk factors for the evolvement of acute to chronic pain in children and adolescents.103,164 A recent meta-analysis of clinical trials involving adolescents and adults undergoing orthopedic surgery166 demonstrated that preoperative psychological interventions, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), hypnosis, relaxation, emotional counselling, and mixed psychotherapies, are effective to reduce acute postoperative anxiety and to improve longer term quality of life, with no effects found on postoperative pain.

2.7. Physical therapy, exercise, and rehabilitation

Physical therapy and exercise are key modalities in the treatment of children with acute and other pain conditions, including pediatric patients with serious illness.30,101,105,108,110,119,120,143 Independent from pain treatment, increasing physical activity levels has also shown to decrease levels of depression.84 Graded Motor Imagery, including mirror therapy, is the process of thinking about moving without actually moving and has been shown especially effective in children when moving the injured body part is too painful.131

2.8. Spirituality

A correlation between spiritual coping and the quality of life in pediatric patients with chronic illness has been described.65,132 Parents of children with serious illness described religion, spirituality, and/or life philosophy playing an important role in their life and of the affected child.75 Most children's hospitals encourage the inclusion of spiritual aspects of life into health care, for instance, by making hospital chaplains available.

2.9. Regional anesthesia

One of the most effective analgesic modalities in children with tissue injury represents regional or neuraxial anesthesia.13,26,27,73,140,142 Nociceptive pathways may be blocked using central neuraxial infusions, peripheral nerve, and plexus blocks or infusions, or neurolytic blocks.136 Benefits of regional anesthesia include reduced (or no) need for opioid analgesics, absence of systemic side effects such as sedation or nausea, improved gastrointestinal motility, reduced incidence of delirium, and the opportunity for the patient to be awake and able to remember conversations with clinicians and family.11 In addition to motor weakness, less common potential side effects with epidural include pruritus, urinary retention, and hypotension.

3. Management of chronic pediatric pain

Pediatric chronic pain is a significant problem with conservative estimates that posit 20% to 35% of children and adolescents affected by it worldwide.58,91,147 Pain experienced by patients in children's hospitals is known to be common, with more than 10% of hospitalized children showing features of chronic pain.48,148,162,182 Although the majority of children reporting chronic pain are not greatly disabled by it,80,176 about 3% of pediatric chronic pain patients require intensive rehabilitation.71

The 2012 American Pain Society Position Statement, “Assessment and Management of Children with Chronic Pain,” indicates that chronic pain in children is the result of a dynamic integration of biological processes, psychological factors, and sociocultural variables, considered within a developmental trajectory.43 Unlike in adult medicine, chronic pain in children is not necessarily defined by using arbitrary temporal parameters (eg, 3 months) but rather uses a more functional definition such as “pain that extends beyond the expected period of healing” and “hence lacks the acute warning function of physiological nociception.”168,169

3.1. Interdisciplinary management of chronic pediatric pain

An interdisciplinary approach combining (1) rehabilitation, (2) integrative medicine/active mind–body techniques, (3) psychology interventions, and (4) normalizing daily school attendance, sports, social life, and sleep seem to be most effective. As a result of restored function, pain improves and commonly resolves. Opioids are not indicated for primary pain disorders (including centrally mediated abdominal pain syndrome, primary headaches [tension headaches/migraines], and widespread musculoskeletal pain) and other medications, with few exceptions, are usually not first-line therapy.

A recent Cochrane review concluded that face-to-face psychological treatments might be effective in reducing pain outcomes for children and adolescents with headache and other types of chronic pain.42 Psychological treatments have also been found to be effective for reducing pain-related disability in children and adolescents with mixed chronic pain conditions at post-treatment and follow-up and for children with headache at follow-up.31 The most commonly used psychological therapy, CBT,31,121 has been shown to reduce pain severity in children and adolescents with widespread musculoskeletal/joint pain, headaches, abdominal pain, and headaches.31,121

As proposed by Palermo's conceptual framework for understanding chronic pain in children and adolescents122,124 and the Interpersonal Fear-Avoidance Model,60,62 a child's social environment and especially parents play a key role in understanding childhood chronic pain. Increasing evidence suggests that it is important to target parental catastrophizing thoughts, parental distress, and parental behaviors with regard to child pain (eg, protective behaviors), which has led to recommendations to incorporate parents within the multidisciplinary treatment.62 A recent Cochrane review100 indeed indicated a beneficial effect of psychological therapies for parents of children with chronic pain conditions on parenting behavior (eg, reduction of protective behaviors) at post-treatment and follow-up. Furthermore, this review also showed that psychological therapies can improve parent mental health in this population. When considering children's treatment outcomes, a small beneficial effect was found on children's behavior and disability at post-treatment and follow-up. Furthermore, a moderate beneficial effect was found on children's pain at post-treatment, but no effects on child mental health at post-treatment or follow-up.

With regard to the specific effects of CBT, the available evidence shows that CBT is effective in decreasing parents' protective responses in children with chronic (or persistent) abdominal pain.102 Furthermore, a recent randomized controlled trial examining the effects of family-based CBT delivered through the internet99,123 demonstrated greater reductions in activity limitations from baseline to 6-month follow-up for internet-delivered CBT compared with an educational intervention. Additional beneficial effects of CBT were found on sleep quality, reduction of parents' protective behaviors, and treatment satisfaction.123 Secondary longitudinal analyses further showed that child disability, parent protective behavior, and parent distress improved over the 12-month study period.99 Indeed, a recent systematic review on the effects of internet-delivered CBT in youth with chronic pain and their parents161 showed that, compared with pretreatment, internet-delivered CBT had medium to large benefits on child pain intensity, activity limitations, and parental protective behaviors immediately after treatment. Furthermore, small to medium positive effects were found for child depressive symptoms, anxiety, and sleep quality. However, still limited evidence is available, and more trials are needed (Box 1).161

Box 1. Treatment of chronic pain and primary pain disorders.50.

(1) Rehabilitation (eg, physical therapy, graded motor imagery,131 and occupational therapy)

(2) Integrative (“nonpharmacological”) modalities (eg, mind–body techniques such as diaphragmatic breathing, bubble blowing, self-hypnosis, progressive muscle relaxation, and biofeedback plus modalities such as massage, aromatherapy, acupressure, and acupuncture)

(4) Psychology (eg, cognitive-behavioral therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy)

-

(4) Normalizing life (usually life gets back to normal first, then pain goes down—not the other way around)

• Sports/exercise

• Sleep hygiene

• Social life

• School attendance

-

(5) Medications (may or may not be required)

• Basic analgesia (eg, paracetamol/acetaminophen, NSAIDs, and COX-2 inhibitor)

• Adjuvant analgesics (eg, gabapentin, clonidine, and/or amitriptyline)

• Of note: Opioids in the absence of new tissue injury, eg, epidermolysis bullosa and osteogenesis imperfecta, are usually not indicated

3.2. Early screening of children's risk profile to tailor clinical care

To ensure optimal clinical care and treatment for children and adolescents who present with chronic pain complaints at the hospital, early identification of risk factors for adverse outcomes may be warranted. Recently, a 9-item Pediatric Pain Screening Tool (PPST)70,145 has been developed, to rapidly assess risk factors associated with adverse outcomes, such as sleep problems, catastrophizing thoughts, pain-related fear, and depression. Early identification of risk factors that may maintain chronic pain allows optimal stratified care and may improve recovery rates. Importantly, evidence supports the generalizability of the PPST across pain complaints.70,145 Based on this brief scale, a risk profile of the child can be calculated, which provides indications for the type of care needed, ie, conservative treatment including education/advice, for instance, regarding sleep hygiene (low-risk profile), referral to physiotherapy (medium-risk profile), or referral for multidisciplinary treatment, for instance, including psychological treatment and physical therapy for elevated pain-related fear (high-risk profile).70,145

Given the major role of parents in influencing a child's pain experience and functioning,60,62 Simons et al. also developed a brief 12-item self-report screening tool (Parent Risk and Impact Screening Measure [PRISM]146) to assess parents' psychosocial functioning (ie, parents' distress and health), behavioral responses to their child's pain, and the impact of the child's pain on the family. Similar to the PPST, risk profiles of parents can be calculated, identifying parents at low, medium, or high risk and informing the clinician, which parents would benefit from a referral for parent-focused treatment or targeted pain-related interventions for parents (eg, to reduce protective behaviors).

3.3. Strengthening resilience mechanisms

Next to identifying and targeting risk factors for adverse outcomes, it has increasingly been acknowledged that it is also important to identify and promote factors or strengths that can improve adaptive or resilient functioning.25,61 Resilient functioning can be best defined as the ability to restore and sustain living a fulfilling life in the presence of pain61 (eg, is the child able to engage in activities he/she finds important despite the pain; can he/she keep high levels of well-being despite the pain). When a child presents with pain complaints at the hospital, attention should not only be paid to malfunctioning but also to what goes well in the child's life, and how this resilient functioning can be further improved. This can be performed by strengthening resilience mechanisms such as positive affect, psychological flexibility, acceptance of pain, gratitude, and availability of family support over and above targeting/reducing risk factors such as pain-related fear.61 Although empirical evidence is still in its infancy, studies in adults show promising results of resilience-based treatment approaches such as positive psychology interventions128 and acceptance-based approaches.174 Although more empirical research is needed which interventions are most effective for whom, interventions promoting resilience mechanisms may be particularly valuable in early stages of treatment, to support adaptive domains of functioning and to prevent adverse outcomes in the long run. In children with high-risk profiles, it may be an important component of a multimodal approach to treatment.

Research on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT),69,129 a third generation behavior therapy that aims to promote resilient functioning by fostering psychological flexibility and acceptance of pain, is growing, and there is accumulating evidence that it can promote better functioning in adolescents with chronic pain, better pain acceptance, better school attendance, and reduced catastrophizing and anxiety and reduced use of health care facilities.57,129 Furthermore, a recent nonrandomized clinical trial in adolescents with chronic pain and their parents89 showed that acceptance and commitment therapy had positive effects not only on adolescents' functioning but also on parents. Specifically, it was found to lead to significant improvements in parents' depressive symptoms and psychological flexibility. Moreover, this study showed that improvements in parents' psychological flexibility were associated with better adolescent pain acceptance over time.

4. Management of needle pain in children

Untreated needle pain, caused by procedures such as vaccinations, blood draws, injections, and venous cannulation can have long-term consequences including needle phobia, preprocedural anxiety, hyperalgesia, and avoidance of health care, resulting in increased morbidity and mortality.153,154 Current evidence,154,158,159 supported by guidelines from the Canadian Paediatric Society,18,82 HELPinKids,72,111,112,157 and recently brought forward by science-to-social media campaigns (“Be Sweet to Baby”21 and especially “It Doesn't Have to Hurt” by Chambers et al.20), strongly suggests that 4 bundled modalities should be offered for elective needle procedures to reduce or eliminate pain and anxiety experienced by children (Box 2).52

Box 2. Prevention and treatment of needle pain.

Offer a bundle of these 4 (or 3 for >12 months) evidence-based modalities to all children all the time:

(1) Topical anesthesia “Numb the skin” eg, 4% lidocaine cream (administered 30 minutes prior procedure), EMLA (lidocaine 2.5% and prilocaine 2.5%) cream (60 minutes prior), amethocaine [tetracaine] 4% gel (30–60 minutes prior) or needleless lidocaine application using pressurized gas to propel medication through the skin (1 minutes prior) eg J-Tip®

(2) Sucrose or breastfeeding for infants 0 to 12 months.

(3) Comfort positioning “Do not hold children down.” For infants, consider parent-infant skin-to-skin (kangaroo care) contact. If not feasible, consider swaddling, warmth, facilitated tucking, and/or cobedding for twins. For children 6 months and older, offer sitting upright with parents holding them on their lap or sitting nearby.

(4) Age-appropriate distraction,9,137,171 such as toys, books, blowing bubbles or pinwheels, stress balls, and using apps, videos, or games on electronic devices.

Of note: If above ineffective or not feasible, consider nitrous gas analgesia/sedation. For needle phobia, in addition, consider referral to pediatric psychologist.

Failure to prevent or minimize treatable procedural pain in children is now considered both inappropriate and unethical.51

(1) Topical anesthesia needs to be offered (and unless verbal children decline for themselves), administered to all children 36 weeks' corrected gestational age and older for every elective needle procedure. Topical anesthetics include 4% liposomal lidocaine cream160 (of note, currently, all 4% lidocaine cream available over-the-counter in the United States and Canada is liposomal), EMLA (lidocaine 2.5% and prilocaine 2.5%) cream, or needle-less lidocaine application through a J-tip (sterile, single-use, disposable injector that uses pressurized gas to propel medication through the skin).106,107

EMLA cream may be on the skin for up to 4 hours and provides maximum analgesia after at least 60 minutes compared with 4% lidocaine cream, which is already effective after 30 minutes and may be on skin up to 2 hours.34,92 In comparison with EMLA cream, amethocaine (tetracaine) 4% gel is superior in preventing pain associated with needle procedures.98

Only topical anesthesia, such as lidocaine provided consistent analgesia within an additive pain intervention regimen during vaccinations in infants.160 Dispelling a common myth, topical anesthetics do not constrict veins and do not decrease the chance of venous cannulation.52,106,138 Not surprisingly, topical anesthesia even works for kids under general anesthesia and should therefore be considered.67

Other modalities, including vapocoolants, ice, cool/cold packs, and vibrating devices might be helpful but currently have insufficient evidence for or against their use to reduce pain at time of injection and therefore should be considered in addition to topical anesthetics, but not instead of numbing cream.155

(2) For term infants 0 to 12 months,21 breastfeeding is effective in preventing or decreasing procedural pain in infants and equally effective to sucrose.141 Sucrose reduces pain and cry during painful procedures, such as venipunctures, and seems to facilitate the release of endogenous opioids, as the mu-opioid antagonist naloxone blunts the effect.56,149 The minimally effective dose of 24% sucrose for procedural pain relief in neonates in a recent randomized controlled trial (RCT) has been determined as “just a drop” (0.1 mL)150 and therefore can be administered to infants who are “NPO” (nothing by mouth). It should be administered about 2 minutes before the painful procedure and may be repeated during the intervention.

(3) Comfort positioning: For elective needle procedures, children should not be held down (this might be different in a life-saving intervention). For infants, consider primarily skin-to-skin (kangaroo care) contact. If not feasible, consider swaddling, warmth, facilitated tucking, and/or cobedding for twins.4,14–17,63,64,85 For children 6 months and older, offer sitting upright with parents holding them on their laps or sitting nearby.

Restraining children for procedures is never supportive, creates a negative experience, and increases their anxiety and pain. In fact, children with cancer who have been restrained for procedures report that it makes them feel ashamed, humiliated, powerless, and they report having lost their right to control their own body.87

Of note, a just-published RCT with 242 stable preterm infants by Campbell-Yeo et al.17 seems not only to suggest that maternal-infant skin-to-skin contact, or kangaroo care (KC) is equally effective as 24% oral sucrose, but that the combination of maternal KC and sucrose did not seem to provide additional benefit. Further research on this topic would be required, and as the result of this, future RCTs may challenge current recommendations. The current recommendation of using sucrose as a standard of care will remain in place for the time being.

(4) Age-appropriate distraction includes the use of toys, books, blowing bubbles or pinwheels, stress balls, and using apps, videos, or games on electronic devices.9,137,171 A recent Cochrane review identified sufficient evidence for the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy, breathing interventions, distraction, and hypnosis for reducing children's pain and/or fear due to needles.7

Offering these 4 simple modalities (or 3 to children older than 12 months) and not just some of them for all needle procedures for all children all the time has now be implemented systemwide in children's hospitals and pediatricians' offices on several continents.52,130

In addition to these 4 modalities, it is recommended that health care professionals and parents use neutral words and avoid language that can increase fear and may be falsely reassuring (eg, “it will be over soon”; “you will be ok”).153

(5) Deferral process (or “plan B”): If adequate procedural analgesia and anxiolysis is not feasible with the above bundled modalities alone (eg, because the child has been held down in the past and has become too anxious, and/or it was difficult to draw blood in the past, etc.) consider involving a child-life specialist, referral to a child-psychologist to offer CBT to overcome needle phobia and/or consider nitrous gas.53

4.1. Nitrous gas analgesia and sedation

Data reveal that children receiving nitrous gas before and during painful procedures have lower levels of distress, lower pain scores, were more relaxed, and many have no recollection of the procedure afterwards.77,125,165 Nitrous gas concentrations between 40% and 70% can be titrated to achieve minimal sedation only, avoiding moderate sedation.104,183 Children receiving minimal sedation are able to respond to verbal commands, maintain, and protect their airway, spontaneous ventilation, and cardiovascular functions are unaffected.1

5. Conclusion

Access to pain management is a fundamental human right, and it is a human rights violation not to treat pain.83 Yet, pain prevention and treatment in pediatric patients compared with adult medicine is often not only inadequate, but also even less often implemented the younger pediatric patients are. Effective multimodal analgesia for acute pain includes pharmacology, regional anesthesia, rehabilitation, psychology, spirituality and integrative (“nonpharmacological”) modalities, which act synergistically for more effective pediatric pain control with fewer side effects than single analgesic or modality. For chronic pediatric pain, including primary headaches (migraines/tension headaches), centrally mediated abdominal pain, and widespread musculoskeletal pain, an interdisciplinary rehabilitative approach including physical therapy, psychological approaches (eg, CBT, ACT), integrative active mind-body techniques, and normalizing life (school, sleep, social, sports) has been shown most effective. Opioids are usually not indicated in chronic pain in the absence of new tissue injury. For elective needle procedures, such as blood draws, intravenous access, injections, or vaccination, overwhelming evidence now mandates that a bundle of 4 modalities to eliminate or decrease pain must be offered to every child every time: (1) topical anesthesia, eg, lidocaine 4% cream; (2) comfort positioning, eg, skin-to-skin contact for infants or not restraining children; (3) sucrose or breastfeeding for infants; and (4) age-appropriate distraction. A deferral process for children where this bundle is ineffective may include nitrous gas analgesia and sedation.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

References

- [1].American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on S, Analgesia by N-A. Practice guidelines for sedation and analgesia by non-anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology 2002;96:1004–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Anand KJ, Barton BA, McIntosh N, Lagercrantz H, Pelausa E, Young TE, Vasa R. Analgesia and sedation in preterm neonates who require ventilatory support: results from the NOPAIN trial. Neonatal outcome and prolonged analgesia in neonates. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1999;153:331–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Baeumler PI, Fleckenstein J, Benedikt F, Bader J, Irnich D. Acupuncture-induced changes of pressure pain threshold are mediated by segmental inhibition—a randomized controlled trial. PAIN 2015;156:2245–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Benoit B, Campbell-Yeo M, Johnston C, Latimer M, Caddell K, Orr T. Staff nurse utilization of kangaroo care as an intervention for procedural pain in preterm infants. Adv Neonatal Care 2016;16:229–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Beyer JE, DeGood DE, Ashley LC, Russell GA. Patterns of postoperative analgesic use with adults and children following cardiac surgery. PAIN 1983;17:71–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Birnie KA, Chambers CT, Fernandez CV, Forgeron PA, Latimer MA, McGrath PJ, Cummings EA, Finley GA. Hospitalized children continue to report undertreated and preventable pain. Pain Res Manag 2014;19:198–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Birnie KA, Noel M, Chambers CT, Uman LS, Parker JA. Psychological interventions for needle-related procedural pain and distress in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;10:CD005179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Brattberg G. Do pain problems in young school children persist into early adulthood? A 13-year follow-up. Eur J Pain 2004;8:187–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Broome ME, Richtsmeier A, Maikler V, Alexander M. Pediatric pain practices: a national survey of health professionals. J Pain Symptom Manage 1996;11:312–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Burns J, Jackson K, Sheehy KA, Finkel JC, Quezado ZM. The use of dexmedetomidine in pediatric palliative care: a preliminary study. J Palliat Med 2017;20:779–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Burns DA. Using regional anesthesia to manage pediatric acute pain. 11th Pediatric Pain Master's Class (Conference). Minneapolis, MN, USA. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bussing A, Ostermann T, Ludtke R, Michalsen A. Effects of yoga interventions on pain and pain-associated disability: a meta-analysis. J Pain 2012;13:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bussolin L, Busoni P, Giorgi L, Crescioli M, Messeri A. Tumescent local anesthesia for the surgical treatment of burns and postburn sequelae in pediatric patients. Anesthesiology 2003;99:1371–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Campbell-Yeo M, Johnston C, Benoit B, Latimer M, Vincer M, Walker CD, Streiner D, Inglis D, Caddell K. Trial of repeated analgesia with kangaroo mother care (TRAKC trial). BMC Pediatr 2013;13:182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Campbell-Yeo ML, Johnston CC, Joseph KS, Feeley N, Chambers CT, Barrington KJ, Walker CD. Co-bedding between preterm twins attenuates stress response after heel lance: results of a randomized trial. Clin J Pain 2014;30:598–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Campbell-Yeo ML, Disher TC, Benoit BL, Johnston CC. Understanding kangaroo care and its benefits to preterm infants. Pediatr Health Med Ther 2015;6:15–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Campbell-Yeo M, Johnston CC, Benoit B, Disher T, Caddell K, Vincer M, Walker CD, Latimer M, Streiner DL, Inglis D. Sustained efficacy of kangaroo care for repeated painful procedures over neonatal intensive care unit hospitalization: a single-blind randomized controlled trial. PAIN 2019;160:2580–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Canadian Paediatric Society. Reduce the pain of vaccination in babies. 2014. Available at: http://www.caringforkids.cps.ca/uploads/handout_images/3p_babiesto1yr_e.pdf. Accessed December 3, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Casadio P, Fernandes C, Murray RM, Di Forti M. Cannabis use in young people: the risk for schizophrenia. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2011;35:1779–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Centre for Pediatric Pain Research. It doesn't have to hurt. Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada: Centre for Pediatric Pain Research, 2016. Available at: http://itdoesnthavetohurt.ca. Accessed December 3, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [21].CHEO’s Be Sweet to Babies Research Team and the University of Ottawa’s School of Nursing. Be sweet to babies. Ottowa, Ontario, Canada: Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, 2014. Available at: http://www.cheo.on.ca/en/BeSweet2Babies. Accessed December 3, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Chidambaran V, Sadhasivam S, Mahmoud M. Codeine and opioid metabolism: implications and alternatives for pediatric pain management. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2017;30:349–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Chrysostomou C, Schulman SR, Herrera Castellanos M, Cofer BE, Mitra S, da Rocha MG, Wisemandle WA, Gramlich L. A phase II/III, multicenter, safety, efficacy, and pharmacokinetic study of dexmedetomidine in preterm and term neonates. J Pediatr 2014;164:276–82, e271–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ciszkowski C, Madadi P, Phillips MS, Lauwers AE, Koren G. Codeine, ultrarapid-metabolism genotype, and postoperative death. N Engl J Med 2009;361:827–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Cousins LA, Kalapurakkel S, Cohen LL, Simons LE. Topical review: resilience resources and mechanisms in pediatric chronic pain. J Pediatr Psychol 2015;40:840–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Cuignet O, Pirson J, Boughrouph J, Duville D. The efficacy of continuous fascia iliaca compartment block for pain management in burn patients undergoing skin grafting procedures. Anesth Analg 2004;98:1077–81, table of contents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Cuignet O, Mbuyamba J, Pirson J. The long-term analgesic efficacy of a single-shot fascia iliaca compartment block in burn patients undergoing skin-grafting procedures. J Burn Care Rehabil 2005;26:409–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Daling JR, Doody DR, Sun X, Trabert BL, Weiss NS, Chen C, Biggs ML, Starr JR, Dey SK, Schwartz SM. Association of marijuana use and the incidence of testicular germ cell tumors. Cancer 2009;115:1215–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Deshpande A, Mailis-Gagnon A, Zoheiry N, Lakha SF. Efficacy and adverse effects of medical marijuana for chronic noncancer pain: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Can Fam Physician 2015;61:e372–381. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Eccleston C, Malleson PN, Clinch J, Connell H, Sourbut C. Chronic pain in adolescents: evaluation of a programme of interdisciplinary cognitive behaviour therapy. Arch Dis Child 2003;88:881–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Eccleston C, Palermo TM, Williams AC, Lewandowski Holley A, Morley S, Fisher E, Law E. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;5:CD003968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Edwards KM, Hackell JM; Committee on Infectious Diseases TCOP, Ambulatory M. Countering vaccine hesitancy. Pediatrics 2016;138:e20162146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Edwards L, DeMeo S, Hornik CD, Cotten CM, Smith PB, Pizoli C, Hauer JM, Bidegain M. Gabapentin use in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Pediatr 2016;169:310–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Eichenfield LF, Funk A, Fallon-Friedlander S, Cunningham BB. A clinical study to evaluate the efficacy of ELA-Max (4% liposomal lidocaine) as compared with eutectic mixture of local anesthetics cream for pain reduction of venipuncture in children. Pediatrics 2002;109:1093–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Evans S, Tsao JC, Zeltzer LK. Complementary and alternative medicine for acute procedural pain in children. Altern Ther Health Med 2008;14:52–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Evans S, Tsao JC, Zeltzer LK. Paediatric pain management: using complementary and alternative medicine. Rev Pain 2008;2:14–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Evans S, Moieni M, Taub R, Subramanian SK, Tsao JC, Sternlieb B, Zeltzer LK. Iyengar yoga for young adults with rheumatoid arthritis: results from a mixed-methods pilot study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010;39:904–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].FDA (Food and Drug Administration). Codeine and tramadol medicines: drug safety communication—restricting use in children, recommending against use in breastfeeding women. 2017. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm554029.htm?source=govdelivery&utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery. Accessed September 3, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Ferrini R, Paice JA. How to initiate and monitor infusional lidocaine for severe and/or neuropathic pain. J Support Oncol 2004;2:90–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Finkel J, Pestieau S, Quezado Z. Ketamine as an adjuvant for treatment of cancer pain in children and adolescents. J Pain 2007;8:515–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Finnerup NB, Attal N, Haroutounian S, McNicol E, Baron R, Dworkin RH, Gilron I, Haanpaa M, Hansson P, Jensen TS, Kamerman PR, Lund K, Moore A, Raja SN, Rice AS, Rowbotham M, Sena E, Siddall P, Smith BH, Wallace M. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol 2015;14:162–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Fisher E, Law E, Dudeney J, Palermo TM, Stewart G, Eccleston C. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;9:CD003968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Force APSPCPT (American Pain Society: Pediatric Chronic Pain Task Force). Assessment and management of children with chronic pain. A position statement from the American Pain Society. 2012. Available at: http://americanpainsociety.org/uploads/get-involved/pediatric-chronic-pain-statement.pdf. Accessed September 3, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Friedrichsdorf SJ, Kohen DP. Integration of hypnosis into pediatric palliative care. Ann Palliat Med 2018;7:136–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Friedrichsdorf SJ, Nugent AP. Management of neuropathic pain in children with cancer. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2013;7:131–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Friedrichsdorf S, Kuttner L, Westendorp K, McCarty R. Integrative pediatric palliative care. In: Culbert TP, Olness K, editors. Integrative pediatrics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. p. 569–93. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Friedrichsdorf SJ, Nugent AP, Strobl AQ. Codeine-associated pediatric deaths despite using recommended dosing guidelines: three case reports. J Opioid Manag 2013;9:151–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Friedrichsdorf SJ, Postier A, Eull D, Weidner C, Foster L, Gilbert M, Campbell F. Pain outcomes in a US children's hospital: a prospective cross-sectional survey. Hosp Pediatr 2015;5:18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Friedrichsdorf SJ, Postier AC, Foster LP, Lander TA, Tibesar RJ, Lu Y, Sidman JD. Tramadol versus codeine/acetaminophen after pediatric tonsillectomy: a prospective, double-blinded, randomized controlled trial. J Opioid Manag 2015;11:283–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Friedrichsdorf SJ, Giordano J, Desai Dakoji K, Warmuth A, Daughtry C, Schulz CA. Chronic pain in children and adolescents: diagnosis and treatment of primary pain disorders in head, abdomen, muscles and joints. Children (Basel) 2016;3:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Friedrichsdorf SJ, Sidman J, Krane EJ. Prevention and treatment of pain in children: toward a paradigm shift. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2016;154:804–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Friedrichsdorf SJ, Eull D, Weidner C, Postier A. A hospital-wide initiative to eliminate or reduce needle pain in children using lean methodology. Pain Rep 2018;3(suppl 1):e671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Friedrichsdorf SJ. Nitrous gas analgesia and sedation for lumbar punctures in children: has the time for practice change come? Pediatr Blood Cancer 2017;64:11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Friedrichsdorf SJ. From tramadol to methadone: opioids in the treatment of pain and dyspnea in pediatric palliative care. Clin J Pain 2019;35:501–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Friedrichsdorf SJ. Prevention and treatment of pain in hospitalized infants, children, and Teenagers: from myths and morphine to multimodal analgesia. In: Pain 2016: refresher courses 16th World Congress on Pain. Washington, DC: International Association for the Study of Pain, IASP Press, 2016. p. 309–319. [Google Scholar]

- [56].Gao H, Gao H, Xu G, Li M, Du S, Li F, Zhang H, Wang D. Efficacy and safety of repeated oral sucrose for repeated procedural pain in neonates: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud 2016;62:118–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Gauntlett-Gilbert J, Connell H, Clinch J, McCracken LM. Acceptance and values-based treatment of adolescents with chronic pain: outcomes and their relationship to acceptance. J Pediatr Psychol 2013;38:72–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Goodman JE, McGrath PJ. The epidemiology of pain in children and adolescents: a review. PAIN 1991;46:247–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Goubert L, Friedrichsdorf SJ. Factsheet pain in children: management. 2019 global year against pain in the vulnerable. International Association for the Study of Pain [IASP], 2019. Available at: https://s3.amazonaws.com/rdcms-iasp/files/production/public/2019GlobalYear/Fact_Sheets/Pain_in_Children_Management_GY.pdf. Accessed December 3, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [60].Goubert L, Simons LE. Cognitive styles and processes in paediatric pain. In: McGrath P, Stevens B, Walker S, Zempsky WT, editors. Oxford textbook of paediatric pain Oxford: Oxford University Press., 2013. p. 95–101. [Google Scholar]

- [61].Goubert L, Trompetter H. Towards a science and practice of resilience in the face of pain. Eur J Pain 2017;21:1301–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Goubert L, Pillai-Riddell R, Simons L, Borsook D. Theoretical basis of pain. In: McGrath P, Stevens B, Walker S, Zemsky W, editors. Oxford textbook of paediatric pain. 2nd ed Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019. p. 95–101. In press. [Google Scholar]

- [63].Gray L, Lang CW, Porges SW. Warmth is analgesic in healthy newborns. PAIN 2012;153:960–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Gray L, Garza E, Zageris D, Heilman KJ, Porges SW. Sucrose and warmth for analgesia in healthy newborns: an RCT. Pediatrics 2015;135:e607–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Grossoehme DH, Szczesniak R, McPhail GL, Seid M. Is adolescents' religious coping with cystic fibrosis associated with the rate of decline in pulmonary function?-A preliminary study. J Health Care Chaplain 2013;19:33–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Grunau RE, Whitfield MF, Petrie-Thomas J, Synnes AR, Cepeda IL, Keidar A, Rogers M, Mackay M, Hubber-Richard P, Johannesen D. Neonatal pain, parenting stress and interaction, in relation to cognitive and motor development at 8 and 18 months in preterm infants. PAIN 2009;143:138–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Hartley C, Poorun R, Goksan S, Worley A, Boyd S, Rogers R, Ali T, Slater R. Noxious stimulation in children receiving general anaesthesia evokes an increase in delta frequency brain activity. PAIN 2014;155:2368–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Hauer JM, Solodiuk JC. Gabapentin for management of recurrent pain in 22 nonverbal children with severe neurological impairment: a retrospective analysis. J Palliat Med 2015;18:453–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy: the process and practice of mindful change. 2nd ed New York: Guilford Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [70].Heathcote LC, Rabner J, Lebel A, Hernandez JM, Simons LE. Rapid screening of risk in pediatric headache: application of the pediatric pain screening tool. J Pediatr Psychol 2018;43:243–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Hechler T, Dobe M, Zernikow B. Commentary: a worldwide call for multimodal inpatient treatment for children and adolescents suffering from chronic pain and pain-related disability. J Pediatr Psychol 2010;35:138–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Help ELiminate pain in kids & adults. 2018. Available at: http://phm.utoronto.ca/helpinkids/index.html. Accessed September 3, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [73].Hernandez JL, Savetamal A, Crombie RE, Cholewczynski W, Atweh N, Possenti P, Schulz JT., III Use of continuous local anesthetic infusion in the management of postoperative split-thickness skin graft donor site pain. J Burn Care Res 2013;34:e257–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Hestbaek L, Leboeuf-Yde C, Kyvik KO, Manniche C. The course of low back pain from adolescence to adulthood: eight-year follow-up of 9600 twins. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:468–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Hexem KR, Mollen CJ, Carroll K, Lanctot DA, Feudtner C. How parents of children receiving pediatric palliative care use religion, spirituality, or life philosophy in tough times. J Palliat Med 2011;14:39–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Hill KP. Medical marijuana for treatment of chronic pain and other medical and psychiatric problems: a clinical review. JAMA 2015;313:2474–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Hockenberry MJ, McCarthy K, Taylor O, Scarberry M, Franklin Q, Louis CU, Torres L. Managing painful procedures in children with cancer. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2011;33:119–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Horvath R, Halbrooks EF, Overman DM, Friedrichsdorf SJ. Efficacy and safety of postoperative dexmedetomidine administration in infants and children undergoing cardiac surgery: a retrospective cohort study. J Pediatr Intensive Care 2015:138–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Howard RF. Current status of pain management in children. JAMA 2003;290:2464–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Huguet A, Miro J. The severity of chronic pediatric pain: an epidemiological study. J Pain 2008;9:226–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Hunt K, Ernst E. The evidence-base for complementary medicine in children: a critical overview of systematic reviews. Arch Dis Child 2011;96:769–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Immunize Canada. Reduce the pain of vaccination in kids and teens. Ottowa, Ontario, Canada: Immunize Canada, 2014. Available at: http://www.immunize.ca/uploads/pain/3p_kidsandteens_e.pdf. Accessed September 3, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [83].International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP). Declaration of Montréal. 2010. Available at: http://www.iasp-pain.org/DeclarationofMontreal?navItemNumber=582. Accessed September 3, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [84].Jerstad SJ, Boutelle KN, Ness KK, Stice E. Prospective reciprocal relations between physical activity and depression in female adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol 2010;78:268–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Johnston C, Campbell-Yeo M, Fernandes A, Inglis D, Streiner D, Zee R. Skin-to-skin care for procedural pain in neonates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;1:CD008435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Kajiume T, Sera Y, Nakanuno R, Ogura T, Karakawa S, Kobayakawa M, Taguchi S, Oshita K, Kawaguchi H, Sato T, Kobayashi M. Continuous intravenous infusion of ketamine and lidocaine as adjuvant analgesics in a 5-year-old patient with neuropathic cancer pain. J Palliat Med 2012;15:719–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Karlson K, Darcy L, Enskär K. The use of restraint is never supportive (poster). Nordic Society of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology (NOPHO) 34th Annual meeting 2016 and 11th Biannual Meeting of Nordic Society of Pediatric Oncology Nurses (NOBOS). Reykjavik, Iceland, 2016.

- [88].Kelly LE, Rieder M, van den Anker J, Malkin B, Ross C, Neely MN, Carleton B, Hayden MR, Madadi P, Koren G. More codeine fatalities after tonsillectomy in North American children. Pediatrics 2012;129:e1343–1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Kemani MK, Kanstrup M, Jordan A, Caes L, Gauntlett-Gilbert J. Evaluation of an intensive interdisciplinary pain treatment based on acceptance and commitment therapy for adolescents with chronic pain and their parents: a nonrandomized clinical trial. J Pediatr Psychol 2018;43:981–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Kennedy A, Basket M, Sheedy K. Vaccine attitudes, concerns, and information sources reported by parents of young children: results from the 2009 HealthStyles survey. Pediatrics 2011;127(suppl 1):S92–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].King S, Chambers CT, Huguet A, MacNevin RC, McGrath PJ, Parker L, MacDonald AJ. The epidemiology of chronic pain in children and adolescents revisited: a systematic review. PAIN 2011;152:2729–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Koh JL, Harrison D, Myers R, Dembinski R, Turner H, McGraw T. A randomized, double-blind comparison study of EMLA and ELA-Max for topical anesthesia in children undergoing intravenous insertion. Paediatr Anaesth 2004;14:977–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Kohen DP, Olness KN. Hypnosis and hypnotherapy with children. New York: Routledge Publications, Taylor & Francis, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [94].Koren G, Cairns J, Chitayat D, Gaedigk A, Leeder SJ. Pharmacogenetics of morphine poisoning in a breastfed neonate of a codeine-prescribed mother. Lancet 2006;368:704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Kovacic K, Hainsworth K, Sood M, Chelimsky G, Unteutsch R, Nugent M, Simpson P, Miranda A. Neurostimulation for abdominal pain-related functional gastrointestinal disorders in adolescents: a randomised, double-blind, sham-controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;2:727–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Kuttner L, Friedrichsdorf SJ. Hypnosis and palliative care. Therapeutic hypnosis with children and adolescents. Bethel: Crown House Publishing Limited, 2013. p. 491–509. [Google Scholar]

- [97].Lacson JC, Carroll JD, Tuazon E, Castelao EJ, Bernstein L, Cortessis VK. Population-based case-control study of recreational drug use and testis cancer risk confirms an association between marijuana use and nonseminoma risk. Cancer 2012;118:5374–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Lander JA, Weltman BJ, So SS. WITHDRAWN: EMLA and amethocaine for reduction of children's pain associated with needle insertion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014:CD004236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Law EF, Fisher E, Howard WJ, Levy R, Ritterband L, Palermo TM. Longitudinal change in parent and child functioning after internet-delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic pain. PAIN 2017;158:1992–2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Law E, Fisher E, Eccleston C, Palermo TM. Psychological interventions for parents of children and adolescents with chronic illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;3:CD009660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Lee BH, Scharff L, Sethna NF, McCarthy CF, Scott-Sutherland J, Shea AM, Sullivan P, Meier P, Zurakowski D, Masek BJ, Berde CB. Physical therapy and cognitive-behavioral treatment for complex regional pain syndromes. J Pediatr 2002;141:135–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Levy RL, Langer SL, Walker LS, Romano JM, Christie DL, Youssef N, DuPen MM, Feld AD, Ballard SA, Welsh EM, Jeffery RW, Young M, Coffey MJ, Whitehead WE. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for children with functional abdominal pain and their parents decreases pain and other symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:946–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Lifland BE, Mangione-Smith R, Palermo TM, Rabbitts JA. Agreement between parent proxy report and child self-report of pain intensity and health-related quality of life after surgery. Acad Pediatr 2018;18:376–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Livingston M, Lawell M, McAllister N. Successful use of nitrous oxide during lumbar punctures: a call for nitrous oxide in pediatric oncology clinics. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2017;64:e26610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Logan DE, Carpino EA, Chiang G, Condon M, Firn E, Gaughan VJ, Hogan M, Leslie DS, Olson K, Sager S, Sethna N, Simons LE, Zurakowski D, Berde CB. A day-hospital approach to treatment of pediatric complex regional pain syndrome: initial functional outcomes. Clin J Pain 2012;28:766–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Lunoe MM, Drendel AL, Brousseau DC. The use of the needle-free jet injection system with buffered lidocaine device does not change intravenous placement success in children in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2015;22:447–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Lunoe MM, Drendel AL, Levas MN, Weisman SJ, Dasgupta M, Hoffmann RG, Brousseau DC. A randomized clinical trial of jet-injected lidocaine to reduce venipuncture pain for young children. Ann Emerg Med 2015;66:466–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Lynch-Jordan AM, Sil S, Peugh J, Cunningham N, Kashikar-Zuck S, Goldschneider KR. Differential changes in functional disability and pain intensity over the course of psychological treatment for children with chronic pain. PAIN 2014;155:1955–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Massey GV, Pedigo S, Dunn NL, Grossman NJ, Russell EC. Continuous lidocaine infusion for the relief of refractory malignant pain in a terminally ill pediatric cancer patient. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2002;24:566–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Maynard CS, Amari A, Wieczorek B, Christensen JR, Slifer KJ. Interdisciplinary behavioral rehabilitation of pediatric pain-associated disability: retrospective review of an inpatient treatment protocol. J Pediatr Psychol 2010;35:128–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].McMurtry CM, Pillai Riddell R, Taddio A, Racine N, Asmundson GJ, Noel M, Chambers CT, Shah V; HelpinKids, Adults T. Far from “just a poke”: common painful needle procedures and the development of needle fear. Clin J Pain 2015;31(10 suppl):S3–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].McMurtry CM, Taddio A, Noel M, Antony MM, Chambers CT, Asmundson GJ, Pillai Riddell R, Shah V, MacDonald NE, Rogers J, Bucci LM, Mousmanis P, Lang E, Halperin S, Bowles S, Halpert C, Ipp M, Rieder MJ, Robson K, Uleryk E, Votta Bleeker E, Dubey V, Hanrahan A, Lockett D, Scott J. Exposure-based Interventions for the management of individuals with high levels of needle fear across the lifespan: a clinical practice guideline and call for further research. Cogn Behav Ther 2016;45:217–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Meier MH, Caspi A, Ambler A, Harrington H, Houts R, Keefe RS, McDonald K, Ward A, Poulton R, Moffitt TE. Persistent cannabis users show neuropsychological decline from childhood to midlife. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:E2657–2664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Meier MH, Hall W, Caspi A, Belsky DW, Cerda M, Harrington HL, Houts R, Poulton R, Moffitt TE. Which adolescents develop persistent substance dependence in adulthood? Using population-representative longitudinal data to inform universal risk assessment. Psychol Med 2016;46:877–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Moffitt TE, Meier MH, Caspi A, Poulton R. Reply to Rogeberg and Daly: no evidence that socioeconomic status or personality differences confound the association between cannabis use and IQ decline. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013;110:E980–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Moore RA, Derry S, Straube S, Ireson-Paine J, Wiffen PJ. Faster, higher, stronger? Evidence for formulation and efficacy for ibuprofen in acute pain. PAIN 2014;155:14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Nikanne E, Kokki H, Tuovinen K. Postoperative pain after adenoidectomy in children. Br J Anaesth 1999;82:886–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Nissen SE, Yeomans ND, Solomon DH, Luscher TF, Libby P, Husni ME, Graham DY, Borer JS, Wisniewski LM, Wolski KE, Wang Q, Menon V, Ruschitzka F, Gaffney M, Beckerman B, Berger MF, Bao W, Lincoff AM, Investigators PT. Cardiovascular safety of celecoxib, naproxen, or ibuprofen for arthritis. N Engl J Med 2016;375:2519–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Odell S, Logan DE. Pediatric pain management: the multidisciplinary approach. J Pain Res 2013;6:785–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Palermo TM, Scher MS. Treatment of functional impairment in severe somatoform pain disorder: a case example. J Pediatr Psychol 2001;26:429–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Palermo TM, Eccleston C, Lewandowski AS, Williams AC, Morley S. Randomized controlled trials of psychological therapies for management of chronic pain in children and adolescents: an updated meta-analytic review. PAIN 2010;148:387–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Palermo TM, Valrie CR, Karlson CW. Family and parent influences on pediatric chronic pain: a developmental perspective. Am Psychol 2014;69:142–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Palermo TM, Law EF, Fales J, Bromberg MH, Jessen-Fiddick T, Tai G. Internet-delivered cognitive-behavioral treatment for adolescents with chronic pain and their parents: a randomized controlled multicenter trial. PAIN 2016;157:174–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Palermo T. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic pain in children and adolescents. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [125].Pedersen RS, Bayat A, Steen NP, Jacobsson ML. Nitrous oxide provides safe and effective analgesia for minor paediatric procedures—a systematic review. Dan Med J 2013;60:A4627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [126].Pediatrics, American Academy of Updated AAP policy opposes marijuana use, citing potential harms, lack of research. 2015. Available at: http://aapnews.aappublications.org/content/early/2015/01/26/aapnews.20150126-1. Accessed September 3, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [127].Peixoto RD, Hawley P. Intravenous lidocaine for cancer pain without electrocardiographic monitoring: a retrospective review. J Palliat Med 2015;18:373–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [128].Peters ML, Smeets E, Feijge M, van Breukelen G, Andersson G, Buhrman M, Linton SJ. Happy despite pain: a randomized controlled trial of an 8-week internet-delivered positive psychology intervention for enhancing well-being in patients with chronic pain. Clin J Pain 2017;33:962–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [129].Pielech M, Vowles KE, Wicksell R. Acceptance and commitment therapy for pediatric chronic pain: theory and application. Children (Basel) 2017;4:E10.28146108 [Google Scholar]

- [130].Postier AC, Eull D, Schulz C, Fitzgerald M, Symalla B, Watson D, Goertzen L, Friedrichsdorf SJ. Pain experience in a US children's hospital: a point prevalence survey undertaken after the implementation of a system-wide protocol to eliminate or decrease pain caused by needles. Hosp Pediatr 2018;8:515–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [131].Ramsey LH, Karlson CW, Collier AB. Mirror therapy for phantom limb pain in a 7-year-old male with osteosarcoma. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;53:e5–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [132].Reynolds N, Mrug S, Guion K. Spiritual coping and psychosocial adjustment of adolescents with chronic illness: the role of cognitive attributions, age, and disease group. J Adolesc Health 2013;52:559–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [133].Richardson J, Smith JE, McCall G, Pilkington K. Hypnosis for procedure-related pain and distress in pediatric cancer patients: a systematic review of effectiveness and methodology related to hypnosis interventions. J Pain Symptom Manage 2006;31:70–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [134].Richmond C. Dame cicely saunders. BMJ 2005;331:238. [Google Scholar]

- [135].Roofthooft DW, Simons SH, Anand KJ, Tibboel D, van Dijk M. Eight years later, are we still hurting newborn infants? Neonatology 2014;105:218–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [136].Rork JF, Berde CB, Goldstein RD. Regional anesthesia approaches to pain management in pediatric palliative care: a review of current knowledge. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013;46:859–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [137].Schechter NL, Allen DA, Hanson K. Status of pediatric pain control: a comparison of hospital analgesic usage in children and adults. Pediatrics 1986;77:11–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [138].Schreiber S, Ronfani L, Chiaffoni GP, Matarazzo L, Minute M, Panontin E, Poropat F, Germani C, Barbi E. Does EMLA cream application interfere with the success of venipuncture or venous cannulation? A prospective multicenter observational study. Eur J Pediatr 2013;172:265–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [139].Seah DSE, Herschtal A, Tran H, Thakerar A, Fullerton S. Subcutaneous lidocaine infusion for pain in patients with cancer. J Palliat Med 2017;20:667–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [140].Sen IM, Sen RK. Regional anesthesia for lower limb burn wound debridements. Arch Trauma Res 2012;1:135–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [141].Shah PS, Herbozo C, Aliwalas LL, Shah VS. Breastfeeding or breast milk for procedural pain in neonates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;12:CD004950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [142].Shank ES, Martyn JA, Donelan MB, Perrone A, Firth PG, Driscoll DN. Ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia for pediatric burn reconstructive surgery: a prospective study. J Burn Care Res 2016;37:e213–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [143].Sherry DD, Wallace CA, Kelley C, Kidder M, Sapp L. Short- and long-term outcomes of children with complex regional pain syndrome type I treated with exercise therapy. Clin J Pain 1999;15:218–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [144].Shomaker K, Dutton S, Mark M. Pain prevalence and treatment patterns in a US children's hospital. Hosp Pediatr 2015;5:363–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [145].Simons LE, Smith A, Ibagon C, Coakley R, Logan DE, Schechter N, Borsook D, Hill JC. Pediatric Pain Screening Tool: rapid identification of risk in youth with pain complaints. PAIN 2015;156:1511–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [146].Simons LE, Lewandowski Holley A, Phelps E, Wilson AC. PRISM: a brief screening tool to identify risk in parents of youth with chronic pain. PAIN 2019;160:367–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [147].Stanford EA, Chambers CT, Biesanz JC, Chen E. The frequency, trajectories and predictors of adolescent recurrent pain: a population-based approach. PAIN 2008;138:11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [148].Stevens BJ, Harrison D, Rashotte J, Yamada J, Abbott LK, Coburn G, Stinson J, Le May S. Pain assessment and intensity in hospitalized children in Canada. J Pain 2012;13:857–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [149].Stevens B, Yamada J, Ohlsson A, Haliburton S, Shorkey A. Sucrose for analgesia in newborn infants undergoing painful procedures. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;7:CD001069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [150].Stevens B, Yamada J, Campbell-Yeo M, Gibbins S, Harrison D, Dionne K, Taddio A, McNair C, Willan A, Ballantyne M, Widger K, Sidani S, Estabrooks C, Synnes A, Squires J, Victor C, Riahi S. The minimally effective dose of sucrose for procedural pain relief in neonates: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pediatr 2018;18:85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [151].Stubberud A, Varkey E, McCrory DC, Pedersen SA, Linde M. Biofeedback as prophylaxis for pediatric migraine: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2016;138:e20160675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [152].Taddio A, Katz J, Ilersich AL, Koren G. Effect of neonatal circumcision on pain response during subsequent routine vaccination. Lancet 1997;349:599–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [153].Taddio A, Chambers CT, Halperin SA, Ipp M, Lockett D, Rieder MJ, Shah V. Inadequate pain management during routine childhood immunizations: the nerve of it. Clin Ther 2009;31(suppl 2):S152–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [154].Taddio A, Appleton M, Bortolussi R, Chambers C, Dubey V, Halperin S, Hanrahan A, Ipp M, Lockett D, MacDonald N, Midmer D, Mousmanis P, Palda V, Pielak K, Riddell RP, Rieder M, Scott J, Shah V. Reducing the pain of childhood vaccination: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline. CMAJ 2010;182:E843–855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [155].Taddio A, Appleton M, Bortolussi R, Chambers C, Dubey V, Halperin S, Hanrahan A, Ipp M, Lockett D, MacDonald N, Midmer D, Mousmanis P, Palda V, Pielak K, Riddell RP, Rieder M, Scott J, Shah V. Reducing the pain of childhood vaccination: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline (summary). CMAJ 2010;182:1989–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [156].Taddio A, Ipp M, Thivakaran S, Jamal A, Parikh C, Smart S, Sovran J, Stephens D, Katz J. Survey of the prevalence of immunization non-compliance due to needle fears in children and adults. Vaccine 2012;30:4807–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [157].Taddio A, McMurtry CM, Shah V, Riddell RP, Chambers CT, Noel M, MacDonald NE, Rogers J, Bucci LM, Mousmanis P, Lang E, Halperin SA, Bowles S, Halpert C, Ipp M, Asmundson GJ, Rieder MJ, Robson K, Uleryk E, Antony MM, Dubey V, Hanrahan A, Lockett D, Scott J, Votta Bleeker E; HelpinKids, Adults. Reducing pain during vaccine injections: clinical practice guideline. CMAJ 2015;187:975–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [158].Taddio A, Parikh C, Yoon EW, Sgro M, Singh H, Habtom E, Ilersich AF, Pillai Riddell R, Shah V. Impact of parent-directed education on parental use of pain treatments during routine infant vaccinations: a cluster randomized trial. PAIN 2015;156:185–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [159].Taddio A, Shah V, McMurtry CM, MacDonald NE, Ipp M, Riddell RP, Noel M, Chambers CT; HelpinKids, Adults T. Procedural and physical interventions for vaccine injections: systematic review of randomized controlled trials and quasi-randomized controlled trials. Clin J Pain 2015;31(10 suppl):S20–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [160].Taddio A, Pillai Riddell R, Ipp M, Moss S, Baker S, Tolkin J, Malini D, Feerasta S, Govan P, Fletcher E, Wong H, McNair C, Mithal P, Stephens D. Relative effectiveness of additive pain interventions during vaccination in infants. CMAJ 2017;189:E227–E234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [161].Tang WX, Zhang LF, Ai YQ, Li ZS. Efficacy of Internet-delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy for the management of chronic pain in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e12061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [162].Taylor EM, Boyer K, Campbell FA. Pain in hospitalized children: a prospective cross-sectional survey of pain prevalence, intensity, assessment and management in a Canadian pediatric teaching hospital. Pain Res Manag 2008;13:25–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [163].Teerawattananon C, Tantayakom P, Suwanawiboon B, Katchamart W. Risk of perioperative bleeding related to highly selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2017;46:520–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [164].Tegethoff M, Belardi A, Stalujanis E, Meinlschmidt G. Comorbidity of mental disorders and chronic pain: chronology of onset in adolescents of a National Representative Cohort. J Pain 2015;16:1054–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [165].Tobias JD. Applications of nitrous oxide for procedural sedation in the pediatric population. Pediatr Emerg Care 2013;29:245–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [166].Tong F, Dannaway J, Enke O, Eslick G. Effect of preoperative psychological interventions on elective orthopaedic surgery outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. ANZ J Surg 2019. 10.1111/ans.15332. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]