Abstract

STMN1 has been regarded as an oncogene and its upregulation is closely associated with malignant behavior and poor prognosis in multiple cancers. However, the detailed functions and underlying mechanisms of STMN1 are still largely unknown in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) development. Herein, we analyzed STMN1 expression and the related clinical significance in HCC by using well‐established Protein Atlas, The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) cancer databases. Analysis indicated that STMN1 was highly expressed in HCC and closely associated with vascular invasion, higher histological grade, advanced clinical grade and shorter survival time in HCC patients. Overexpressing and silencing STMN1 in HCC cell lines showed that STMN1 could regulate cell proliferation, migration, drug resistance, cancer stem cell properties in vitro as well as tumor growth in vivo. Further experiments showed that STMN1 mediated intricate crosstalk between HCC and hepatic stellate cells (HSC) by triggering the hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)/MET signal pathway. When HSC were cocultured with HCC cells, HSC secreted more HGF to stimulate the expression of STMN1 in HCC cells. Mutually, STMN1 upregulation in HCC cells facilitated HSC activation to acquire cancer‐associated fibroblast (CAF) features. The MET inhibitor crizotinib significantly blocked this crosstalk and slowed tumor growth in vivo. In conclusion, our findings shed new insight on STMN1 function, and suggest that STMN1 may be used as a potential marker to identify patients who may benefit from MET inhibitor treatment.

Keywords: hepatic stellate cell, hepatocellular carcinoma, MET pathway, STMN1, tumor microenvironment

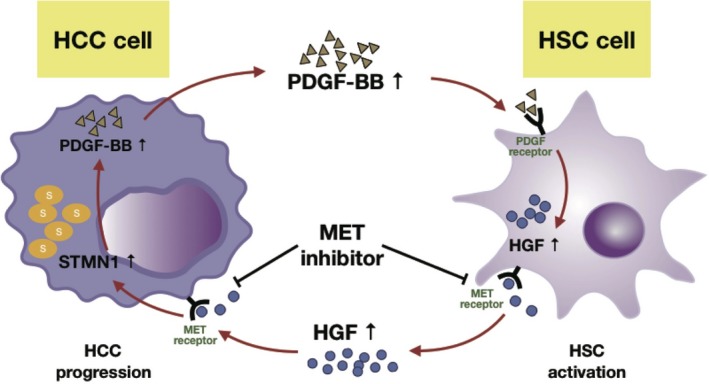

Working model of MET inhibitor inhibited the positive feedback loop between high STMN1 HCC cells and HSC cells. STMN1 mediates intricate crosstalk between HCC and hepatic stellate cells (HSC) by triggering HGF/MET signal pathway. MET inhibitor crizotinib blocked MET pathway to effectively inhibit HCC‐HSC crosstalk and shrink tumor growth when both high STMN1 HCC cells and HSC were coinoculated in mice.

Abbreviations

- AFP

alpha‐fetoprotein

- CAF

cancer‐associated fibroblast

- GEO

Gene Expression Omnibus

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HGF

hepatocyte growth factor

- HSC

hepatic stellate cell

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- TGF‐β

transforming growth factor‐β

1. INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma is the fifth most common malignancy in humans worldwide, with high incidence and mortality rates.1 Metastasis and recurrence after surgery are the major challenges that contribute to the dismal prognosis of HCC. Currently, there is a lack of effective strategies for HCC treatment. Sorafenib is the first FDA‐approved targeted drug for advanced‐stage HCC patients, but the survival benefit is still limited. Recently, with great progress in understanding the molecular mechanisms of cancer development, a number of targeted drugs, such as lenvatinib, regorafenib and cabozantinib, have been developed for cancer therapy. However, the efficacy of these targeted drugs is not satisfactory in HCC because of the high genetic and epigenetic heterogeneities as well as the complicated tumor microenvironment.2, 3

The tumor microenvironment is composed of tumor cells, immune cells, stromal cells, and a variety of cytokines secreted by these cells. HSC are the primary source of CAF, which play important roles in tumor growth, metastasis and drug resistance in HCC.4, 5, 6 There exists intricate crosstalk between HCC and HSC. Tumor cells can secrete multiple growth factors and cytokines to activate HSC. After activation, HSC release a number of oncogenic factors, including HGF, osteopontin (OPN), and TGF‐β to facilitate cancer development. HGF, one of the well‐studied cytokines, can bind to receptor tyrosine kinases to activate the MET pathway, thereby facilitating cell proliferation, invasion, and migration.7 The positive feedback loop in tumor cells and HSC exacerbates HCC progression.8

STMN1 is known as an oncogene encoding a highly conserved 18‐kDa cytosolic phosphoprotein. STMN1 protein has a tubulin‐binding domain, and a Stathmin‐like domain with four serine phosphorylation sites at the N‐terminal region, which play a crucial role in regulating microtubule dynamics by sequestrating alpha/beta‐tubulin heterodimers and promoting microtubule destabilization. STMN1 is found to be upregulated in many cancers such as non‐small cell lung cancer, breast cancer, and gastric cancer. It can induce cell differentiation, proliferation, and migration in solid tumors and is associated with poor clinical prognosis.9, 10 In HCC, high expression of STMN1 is reported to be positively correlated with higher AFP levels, tumor size, vascular invasion, and intrahepatic metastasis, and with lower 5‐year survival and early recurrence rates. However, the detailed functions and underlying mechanisms of STMN1 in HCC development are still largely unknown. Whether the aberrant expression of STMN1 in HCC may mediate the interaction of tumor and the microenvironment needs to be elucidated.

In the present study, we carried out data mining of public biomedical databases and found that high levels of STMN1 are closely associated with poor prognosis in HCC patients. Our results indicated that STMN1 can regulate crosstalk between cancer cells and HSC by triggering the HGF/MET pathway. The MET inhibitor crizotinib efficiently slowed tumor growth in the STMN1‐high group. These findings provide new insight into STMN1 function and present valuable clues for personalized therapy with the MET inhibitor crizotinib in HCC.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Patients and clinical specimens

A total of 17 HCC patients were enrolled in this study. These patients received curative resection for HCC without any preoperative treatment at Huashan Hospital, Fudan University (Shanghai, China) from June 2016 to December 2016. Paraffin samples were collected from patients after obtaining informed consent. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Huashan Hospital, Fudan University.

2.2. Public data collection

Clinical characteristics and normalized level‐three RNA‐sequencing data (RNA‐seq) of HCC patients were obtained for The Cancer Genome Atlas‐Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma (TCGA‐LIHC) dataset from the data portal (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). Exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) patients whose pathological type was cholangiocarcinoma, fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma or mixed hepatocellular/cholangiocarcinoma; and (ii) patients with no survival data or STMN1 expression data. Ultimately, 319 patients were enrolled for analysis. RNA‐seq data for STMN1 in GSE57957 and GSE25097 were obtained from GEO of NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) to compare the expression of STMN1 in healthy, tumorous, and adjacent tissues. Normalized expression matrix files and sequencing platform annotations of the gene sets were downloaded. The highest value for the STMN1 mRNA probe was used among multiple probes.

2.3. Cell lines

The HCC cell line MHCC97L was established at the Liver Cancer Institute, Fudan University. The human HCC cell line Huh7 and the hepatic stellate cell line LX2 were purchased from Cell Bank of Chinese Academy of Sciences. These cell lines were cultured in DMEM (HyClone) with 10% FBS (Gibco) and maintained in a cell incubator with 5% CO2 at 37°C.

2.4. Coculture assay

Six‐well Transwell chambers with 0.4‐µm porous polycarbonate membranes (Corning Incorporated Life Sciences) were used. A total of 5 × 105 Huh7/MHCC97L cells were seeded in the lower chamber 24 hours before coculture, and then 1.5 × 105 LX2 cells were added to the upper chamber. Alternatively, 3 × 105 LX2 cells were plated in the lower chamber 24 hours before coculture, and then 2.5 × 105 Huh7/MHCC97L cells were plated in the upper chamber. After 48 hours, cells in the lower chamber and the supernatant (after centrifuging at 500 g for 3 minutes to remove cell debris) were collected separately for analysis.

2.5. In vivo tumor growth assay

All the in vivo experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Shanghai Medical College, Fudan University. The HCC subcutaneous tumor model was established by injecting 2.5 × 106 MHCC97L cells alone or mixed with 1 × 106 LX2 cells into 5‐week‐old male BALB/c nude mice (Shanghai SLAC Laboratory Animal Co.). When the tumor volume reached approximately 100 mm3, the MET inhibitor crizotinib (20 mg/kg) was given orally 4 days per week. After 4 weeks, tumors from each group were isolated. Tumor size and body weight were measured twice a week. Tumor tissue was fixed by paraffin for further IHC experiments.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences Version 16.0 (SPSS 16.0) and GraphPad Prism 7.0 software. The χ2 test, Student’s t test, and one‐way ANOVA were used for comparison between groups. Kaplan‐Meier survival analyses were used to estimate the prognostic value, and the log‐rank test was used to assess the survival differences. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Detailed methods for plasmid construction and transfection, ELISA, IHC, sphere formation, in vitro migration and invasion assays, cell proliferation assay, wound‐healing assay, and western blotting are described in the supplementary materials (Appendix S1).

3. RESULTS

3.1. STMN1 is upregulated in HCC and associated with advanced tumor stage and poor prognosis

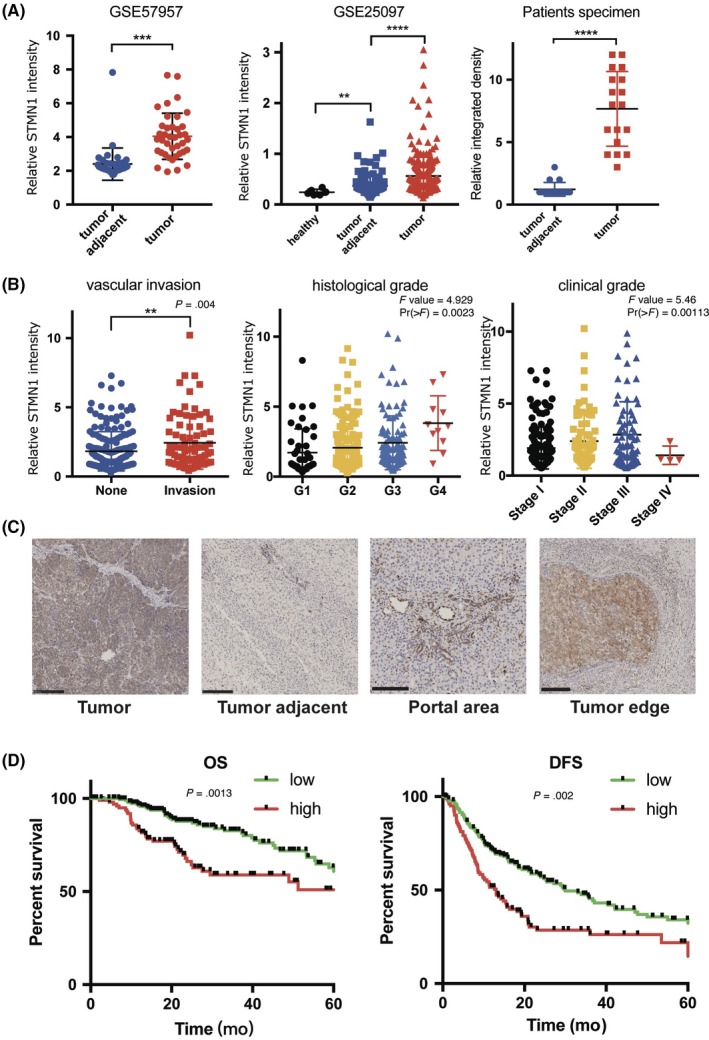

To unravel the functions of STMN1 in cancers, we first analyzed the expression of STMN1 in the Human Protein Atlas database and found that the STMN1 gene is pervasively expressed in various tissues of the human body but is expressed at extremely low levels in normal liver (Figure S1A). Analysis of two HCC GEO datasets, GSE57957 and GSE25097, showed that the expression level of STMN1 was increased significantly in HCC tissues compared with tumor‐adjacent and healthy liver tissues (Figure 1A left and middle). Our IHC assay further confirmed that STMN1 protein displayed stronger staining intensity in HCC tissues than in normal counterparts (Figure 1A right). RNA‐seq data from TCGA‐LIHC database showed that STMN1 was especially higher in patients with vascular invasion, higher histological grade (poor differentiation), and more advanced clinical stage except for stage IV (Figure 1B). Our IHC analysis of STMN1 also showed that STMN1 was specifically higher at the edge of the tumor or around the portal tubes in the tumor than in the other parts (Figure 1C). These results indicated that STMN1 upregulation is closely associated with local tumor invasion and progression of HCC.

Figure 1.

STMN1 is upregulated in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and is associated with advanced tumor stage and poor prognosis. A, RNA and protein level of STMN1 in the tumor, tumor‐adjacent tissue, and healthy tissue in GSE57957, GSE25097, and patient specimen; B, Expression of STMN1 in different clinicopathological groups of patients (none vs invasive tumor; histological grade from G1 to G4; clinical stage from stage I to stage IV). The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)‐LIHC RNA‐seq database showed that higher STMN1 was linked to malignant clinical characteristics. C, Immunohistochemical staining of STMN1 in the tumor, tumor‐adjacent tissue, portal area, and tumor edge tissue from HCC patients showed STMN1 was higher in the tumor than in the tumor‐adjacent tissue, and especially higher in portal area and tumor edge. Bar, 250 μm. D, Overall survival (OS) and disease‐free survival (DFS) of HCC patients in the high STMN1 group was shorter than that in the low STMN1 group. Comparison between two groups (1A left and 1A right: tumor adjacent vs tumor; 1B left: none vascular invasion vs vascular invasion): Student’s t test (normal distributions with equal variances), Welch’s t test (normal distributions but unequal variances) or Mann‐Whitney U test (non‐normal distributions). Comparison between more than two groups (1A middle, 1B middle and 1B right): multiple t test with adjusted P‐value or one‐way ANOVA. Comparison of survival curves (1D): log‐rank test. **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001

Next, we further investigated the correlation of aberrant STMN1 expression with survival time of HCC patients. When the patients were grouped based on the highest significance and the lowest log‐rank P‐value in the Kaplan‐Meier survival estimator in the Human Protein Atlas, FPKM = 13.14 was defined as the best cut‐off to divide the patients into STMN1‐high and ‐low subgroups. Both overall survival (OS) and disease‐free survival (DFS) of the STMN1‐high group (median OS = 25.50 months, median DFS = 13.07 months) were dramatically shorter than those of the STMN1‐low group (median OS = 71.03 months, median DFS = 29.96 months, P = .0013 and .002) (Figure 1D). Unlike the results in HCC, there was no significant survival difference between the STMN1‐high and STMN1‐low groups in other solid cancers, including breast, gastric, colorectal, pancreatic and lung cancers collected in TCGA (Figure S1B) (https://www.proteinatlas.org/). In addition, some other significant clinical and pathological differences were observed between the two groups, including prothrombin time (STMN1‐high group: 3.019 seconds, STMN1‐low group: 4.503 seconds, P = .012), tumor tissue grade (P = .005) and tumor vascular invasion (P = .004) (Table S1).

Taken together, all of the clinical analyses indicated that STMN1 may play critical roles in promoting the development and progression of HCC.

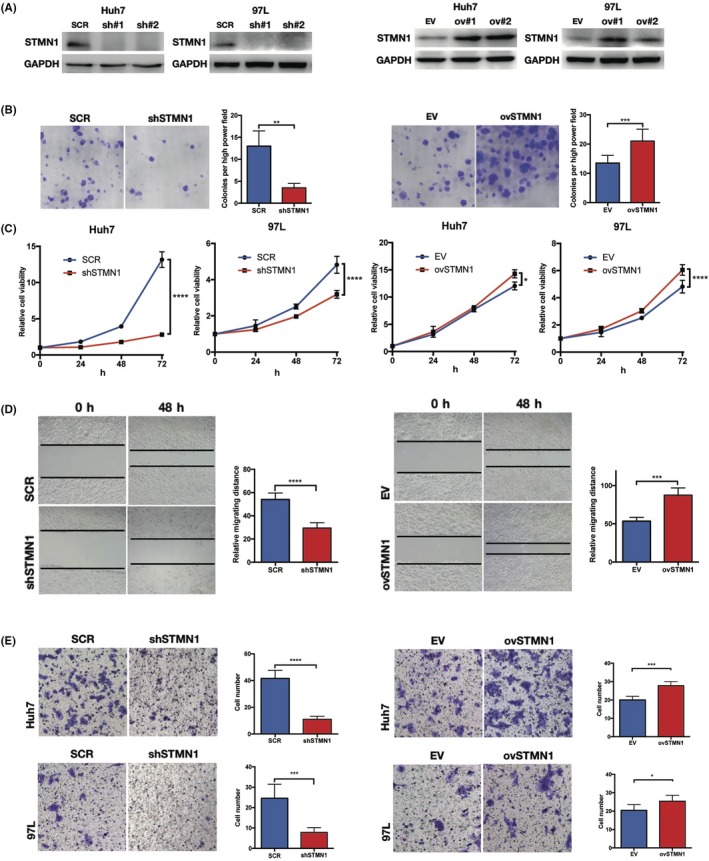

3.2. STMN1 regulates the proliferation and migration of HCC cells

To ascertain the functions of STMN1 in HCC, we knocked down and overexpressed STMN1 in the HCC cell lines Huh7 and 97L (MHCC97L), respectively. Western blot analysis showed manipulation of STMN1 expression was successful (Figure 2A). Compared with control cells, knockdown of STMN1 (shSTMN1) resulted in significant inhibition of colony formation and proliferation in HCC cells, whereas overexpression of STMN1 (ovSTMN1) increased the number of cell colonies and slightly enhanced cell proliferation (Figure 2B,C). Subsequently, wound healing and Transwell experiments indicated that knockdown of STMN1 significantly reduced the migration and invasion abilities of Huh7 and 97L cell lines, whereas overexpression of STMN1 increased these capabilities (Figure 2D,E). These results showed that dysregulation of STMN1 expression can affect HCC cell growth and migration in vitro.

Figure 2.

STMN1 regulates cell proliferation and migration of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells. A, Western‐blot verified the effect of STMN1 knockdown and overexpression in Huh7 and MHCC97L cells. B, Colony formation experiment. C, Cell proliferation assay in STMN1 knockdown and overexpression in Huh7 and MHCC97L cells showed that knockdown of STMN1 impeded tumor cell growth significantly whereas overexpression of STMN1 promoted it. D, Wound healing experiment and E, Transwell experiment showed that knocking down STMN1 impeded migration and invasion of tumor cells whereas overexpressing STMN1 promoted these abilities in Huh7 and MHCC97L cells. SCR, scramble; shSTMN1, STMN1 knockdown cell line; EV, empty vector; ovSTMN1, STMN1 overexpression cell line. Student’s t test. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001

3.3. STMN1 induces sorafenib resistance, sustains cancer stem cell properties, and promotes tumor growth in vivo

Sorafenib is the earliest approved and most widely used targeted drug in HCC, but its drug resistance remains a severe problem in advanced HCC patients. Compared with the control group, the in vitro cell proliferation of the ovSTMN1 group was less sensitive to sorafenib (Figure 3A), indicating that high STMN1 expression might partly mediate primary sorafenib resistance in HCC. Given that cancer stem cells (CSC) have a well‐established role in drug resistance, we detected whether STMN1 could affect the stemness of HCC cells through sphere‐forming experiments. As shown in Figure 3B, silencing STMN1 could strikingly decrease the number of spheres, whereas overexpressing STMN1 endowed HCC cells with the capacity to form more suspended spheres. Subsequently, we analyzed CSC‐related gene expression in the top 100 STMN1‐high patient specimens and the top 100 STMN1‐low patient specimens in TCGA‐LIHC database. Well‐documented CSC‐related genes, such as OCT4, SOX9, CD133, CK19, and EPCAM, were significantly upregulated in the STMN1‐high group (Figure 3C). Moreover, to further address the oncogenic effects of STMN1, s.c. tumor of nude mice was used. We found that knockdown of STMN1 greatly inhibited tumor growth in vivo (Figure 3D). These findings imply that STMN1 may mediate resistance to sorafenib treatment, sustain CSC properties and accelerate tumor growth in HCC.

Figure 3.

STMN1 regulates cell proliferation and migration of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells. A, ovSTMN1 cell line was more resistant to TKI inhibitor sorafenib than the control group. B, Sphere formation experiment showed that regulating STMN1 could affect the stemness of HCC cells. C, Expression of stemness marker genes (EPCAM, SOX9, CD133, CK19 and OCT4) was higher in the STMN1 high group than in the STMN1 low group. D, Nude mice s.c. tumor formation experiment showed that knocking down STMN1 impeded tumor growth significantly in vivo. Student’s t test: 3A, 3B and 3D; Mann‐Whitney U test: 3C. *P < .05; **P < .01; ****P < .0001

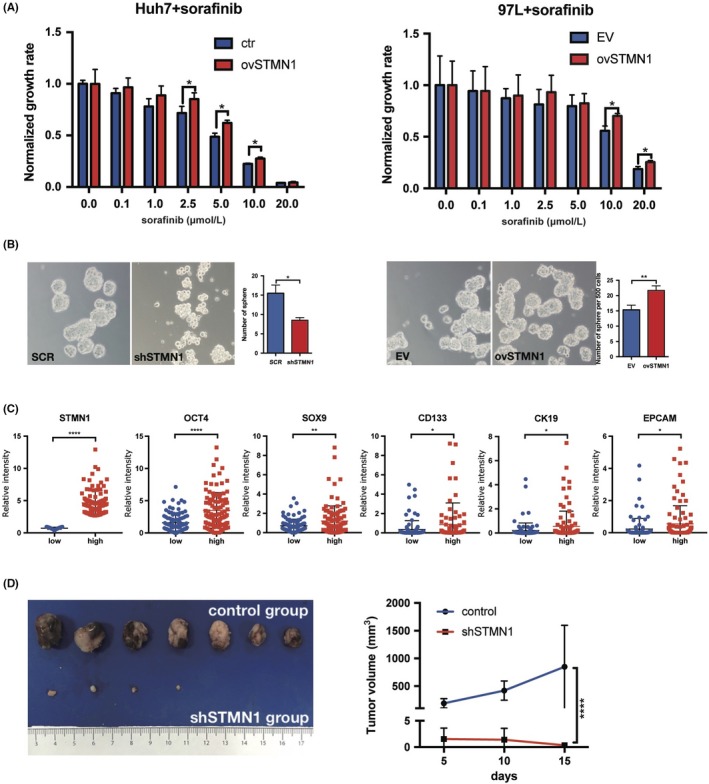

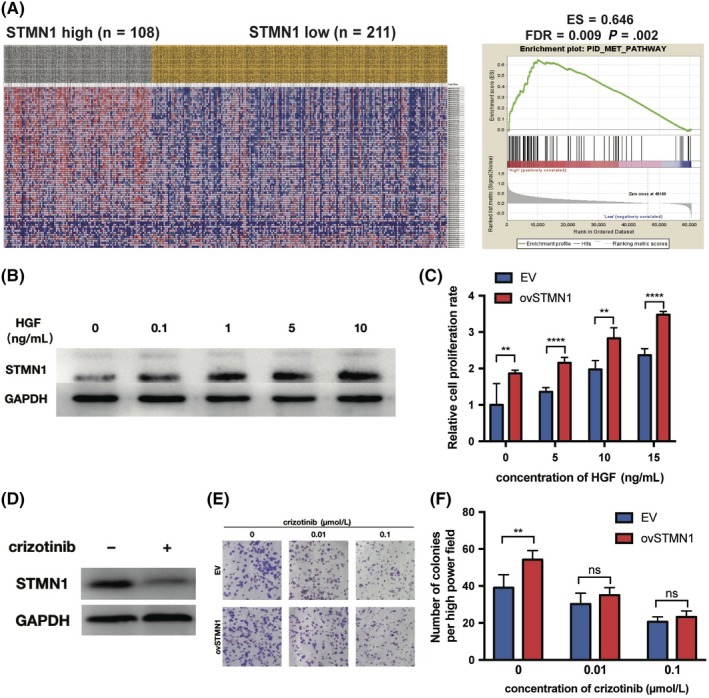

3.4. Activation of the HGF/c‐MET pathway is associated with STMN1 upregulation, and c‐MET inhibition can suppress STMN1‐mediated cell proliferation

To explore the mechanism of STMN1 in promoting HCC cell growth and invasion, we selected several functional gene sets as well as important pathways related to HCC growth and malignancy, and carried out Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) analysis on STMN1‐high and ‐low groups using TCGA‐LIHC RNA‐seq data (Table S2). Results showed that there were no gene sets enriched in the low‐STMN1 group. In the high‐STMN1 group, multiple groups of genes were significantly enriched, including the MET pathway, which is tightly associated with the growth, invasion, and metastasis of HCC (Figure 4A).11 To further investigate the relationship between STMN1 and the MET pathway, 97L cells were treated with different concentrations of HGF, a MET pathway activator, which showed that STMN1 increased in parallel with HGF concentration (Figure 4B). Cell proliferation assays showed that the proliferation ability of HCC cells increased with HGF treatment in a dose‐dependent method in vitro, whereas the growth rate of ovSTMN1 cells increased faster than the control group, indicating that high expression of STMN1 enhanced the sensitivity of HCC cells to HGF (Figure 4C and Figure S2). In addition, the MET inhibitor crizotinib markedly decreased STMN1 protein levels, indicating that the MET pathway inhibitor could regulate STMN1 expression (Figure 4D). Colony formation assays showed that ovSTMN1 cells were more sensitive to crizotinib treatment than were EV cells (Figure 4E,F). All the results proved that STMN1 could be regulated by the HGF/c‐MET pathway and that MET inhibition could effectively inhibit STMN1‐mediated tumor cell growth.

Figure 4.

Activation of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)/c‐MET pathway is associated with STMN1 upregulation, and c‐MET inhibitor can dramatically suppress cell proliferation mediated by STMN1. A, Heat map of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients shows that the genes in the MET pathway were enriched in the STMN1 high group. B, STMN1 upregulated by MET pathway activator HGF. C, Growth rate of the empty vector (EV) and ovSTMN1 cells treated with HGF showed that ovSTMN1 cells were more sensitive to HGF than EV. D, STMN1 downregulated by MET inhibitor crizotinib; cells were treated for 24 h and the concentration of crizotinib was 0.5 μmol/L. E‐F, Colony formation experiment of EV and ovSTMN1 cells treated with crizotinib. Student’s t test. *P < .05; **P < .01; ****P < .0001; ns, not significant

3.5. STMN1 mediates crosstalk between cancer cells and hepatic stellate cells

A previous study showed that HGF is mainly released by HSC.12 Our IHC assays of HCC tissue showed that STMN1‐high HCC cells were mostly surrounded by HSC, and that HSC primarily localized at the edge of tumor or in metastatic nodules (Figure 5A). This special spatial proximity implied that HSC may participate in regulating STMN1 expression in HCC. To clarify the regulation, we constructed the coculture system as shown in Figure 5B,D. After the HCC cells were cocultured with the HSC line LX2, the STMN1 protein level was obviously increased in HCC cells (Figure 5C, left). Meanwhile, the MET pathway was activated in HCC cells (Figure 5C, right). When the MET inhibitor crizotinib was introduced into the coculture system, LX2‐mediated STMN1 upregulation was blocked with the reduction of MET protein levels. This finding suggests that LX2 can trigger STMN1 expression to enhance malignant proliferation of HCC cells by activating the HGF/MET pathway.

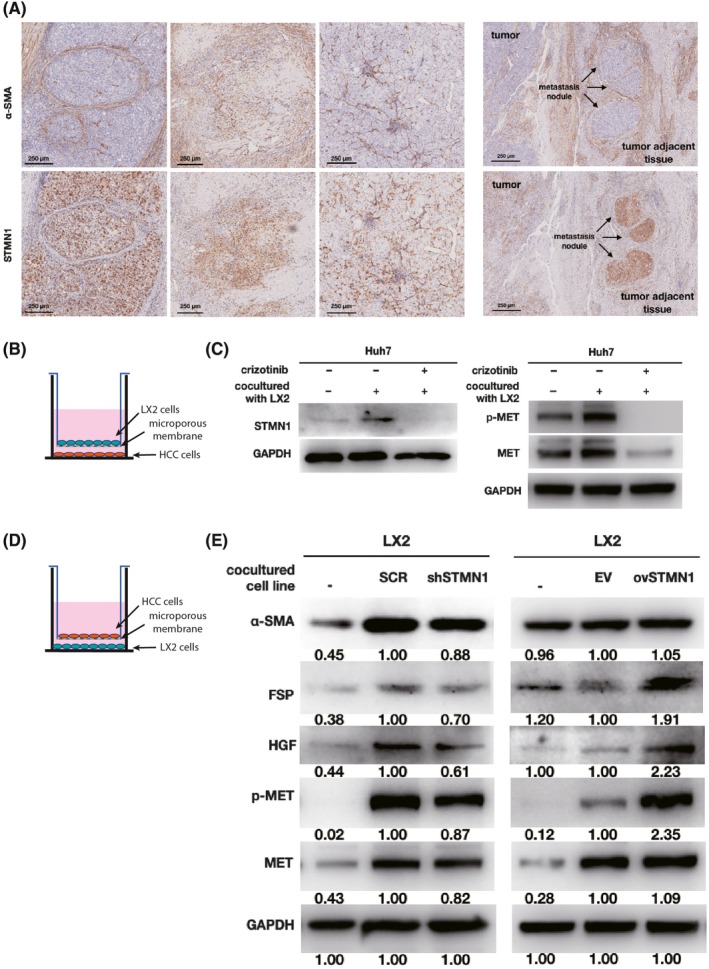

Figure 5.

Crosstalk between hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells and hepatic stellate cell activation. A, Immunohistochemistry of STMN1 and α‐smooth muscle actin (α‐SMA) in the tumor and tumor adjacent tissue of HCC patients shows that expression of STMN1 was higher in HCC cells around hepatic stellate cells (HSC), at the edge of the tumor or in the metastatic nodules surrounded by HSC. Bar, 250 μm. B and D show coculture model of HCC cells and HSC cell line LX2. C, Western blot shows STMN1 and MET/p‐MET expression in Huh7 cells was upregulated after coculture with LX2 cells which could be inhibited by crizotinib. E, Western blot shows that cancer‐associated fibroblast markers, MET and p‐MET in LX2 cells were upregulated after coculture with ovSTMN1 HCC cells and downregulated after coculture with shSTMN1 cells. Ratios of target protein/reference protein were measured by ImageJ. Student’s t test

Cancer‐associated fibroblasts are the activated form of HSC that can secrete a variety of supportive growth factors and nutrients during tumor development, such as HGF and TGF‐β.12 Alpha‐smooth muscle actin (α‐SMA and fibroblast‐specific protein (FSP) are two well‐documented CAF markers. Herein, we assessed whether the aberrant expression of STMN1 may confer CAF properties in HSC. In the coculture system shown in Figure 5D, STMN1 knockdown suppressed HGF expression and MET activation in LX2 cells and reduced the expression of the CAF markers α‐SMA and FSP (Figure 5E, left). In agreement with this result, when STMN1‐overexpressing cells were cocultured with LX2, the HGF/MET pathway was activated, and the CAF markers, α‐SMA and FSP, were strikingly increased in LX2 cells (Figure 5E, right).

Collectively, these findings suggest that STMN1 can mediate the crosstalk between HCC cells and HSC. During the process of HCC development, HSC are transformed to have CAF properties and secrete more HGF, which activates the MET pathway and increases STMN1 expression in HCC cells. High STMN1 expression in HCC cells activates the MET pathway of HSC and enhances CAF characteristics to promote cancer development.

3.6. LX2 enhances STMN1‐mediated platelet‐derived growth factor expression by activating the MET signaling pathway

Within the tumor microenvironment, tumor cells can secrete many kinds of cytokines to activate mesenchymal cells. To explore which HCC‐derived cytokines are responsible for HSC activation, we detected the transcriptional levels of related cytokines by qRT‐PCR. After coculture with LX2, several cytokines showed dysregulation in Huh‐7 cells (Figure 6A). For instance, insulin‐like growth factor (IGF)‐1, IGF‐2, TGF‐A, platelet‐derived growth factor (PDGF)‐C, and epidermal growth factor (EGF) were reduced, whereas TGF‐B and PDGF‐B were increased significantly (Figure 6A). Among these cytokines, the PDGFB gene showed maximum expression. PDGF‐B encodes a homodimeric protein, PDGF‐BB, which functions as a vital activator of HSC to induce liver fibrosis and cancer metastasis.13 Next, we wondered whether STMN1‐mediated PDGF‐B expression is dependent on MET activation. Thus, the MET inhibitor crizotinib was added to the coculture system of LX2 and STMN1‐overexpressing HCC cells. As shown in Figure 6B, the transcriptional level of PDGF‐B was increased in STMN1‐overexpressing HCC cells. After coculture with LX2, STMN1‐mediated PDGF‐B upregulation was further elevated. However, this promoting effect was inhibited by treatment with the MET inhibitor crizotinib. Consistently, PDGF‐BB protein level was elevated by STMN1 overexpression in the HCC cell culture medium. LX2 coculture enhanced STMN1‐modulated PDGF‐BB secretion, and the MET inhibitor crizotinib efficiently blocked this effect (Figure 6C). These results suggest that STMN1 can induce PDGF‐BB expression and that coculture with HSC greatly enhances this effect. The MET inhibitor crizotinib has the capacity to potently abolish PDGF upregulation.

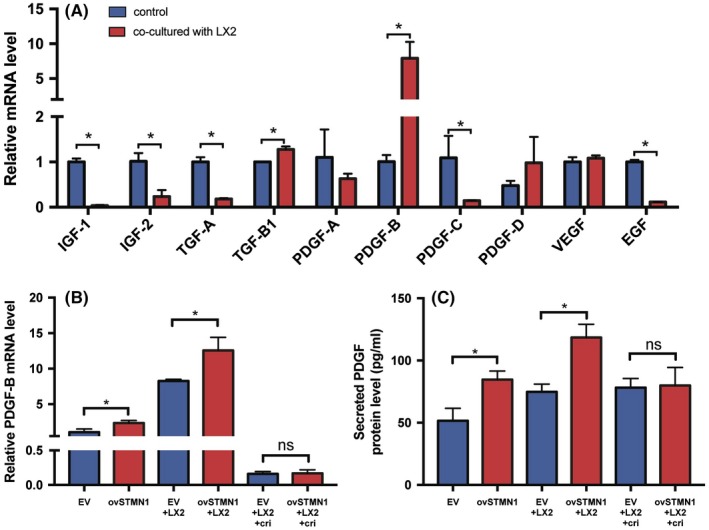

Figure 6.

LX2 enhances STMN1‐mediated platelet‐derived growth factor (PDGF)‐B expression. A, Expression of PDGF‐B in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells was upregulated most significantly among hepatic stellate cell (HSC) activating cytokines after coculture with LX2 cells. B, Expression of PDGF‐B in ovSTMN1 cells and C, amount of protein PDGF‐BB in the supernatant were significantly higher than in empty vector (EV) cells regardless of coculture with or without LX2 cells. After inhibition by crizotinib, the level of PDGF‐B was no longer different between the ovSTMN1 + LX2 and EV + LX2 groups. EGF, epidermal growth factor; IGF, insulin‐like growth factor; TGF, transforming growth factor; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor. Student’s t test. *P < .05; ns, not significant

3.7. Hepatic stellate cells enhance tumor growth mediated by STMN1 overexpression, and MET inhibitor can significantly reverse the malignant effect in vivo

To confirm the above findings, an in vivo tumor growth assay was carried out. As shown in Figure 7A, subcutaneous tumor volume of the ovSTMN1 group was larger than that of the EV group. When the 97L and LX2 cells were mixed at a ratio of 2:1 and injected s.c. into mice, tumor size of the ovSTMN1 + LX2 combination was also significantly larger than that of the EV + LX2 combination (Figure 7A), indicating that HSC could enhance tumor growth through interaction with STMN1‐high HCC cells. After the mice were given MET inhibitor, tumors in the ovSTMN1 + LX2 group were significantly inhibited, but there was no obvious inhibition effect in the EV + LX2 group, which suggested that the MET inhibitor was selectively effective in STMN1‐high HCC cells and blocked the communication between tumor cells and HSC (Figure 7A). IHC results confirmed that in the ovSTMN1 + LX2 group, expression of PDGF‐BB in tumor cells was significantly higher than that in the control group. Similar to the tumor volume results, the inhibition effect of crizotinib on STMN1 and PDGF‐BB was obvious in the ovSTMN1 + LX2 group only (Figure 7B,D). These results suggest that HSC enhanced tumor growth mediated by STMN1 overexpression and that the MET inhibitor effectively reverses the crosstalk between ovSTMN1 and HSC and slows tumor growth in vivo. STMN1 may be a potential marker for MET inhibitor treatment.

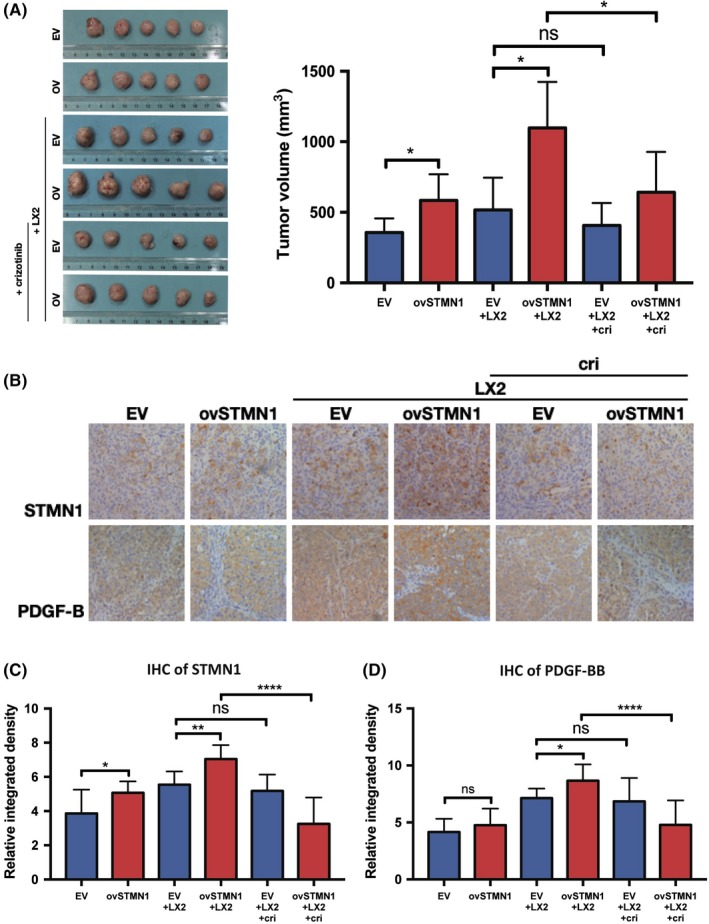

Figure 7.

Hepatic stellate cells enhance tumor growth mediated by STMN1 overexpression, and MET inhibitor can significantly reverse the malignant effect in vivo. A, Tumor volume of nude mice s.c. tumor of ovSTMN1 + LX2 cells was larger than that of other groups, and the inhibition effect of crizotinib was the most obvious in the ovSTMN1 + LX2 group, B‐D, Immunohistochemistry (IHC) of s.c. tumors shows that platelet‐derived growth factor homodimeric protein (PDGF‐BB) and STMN1 were significantly elevated in the ovSTMN1 + LX2 group, which could be obviously inhibited by crizotinib. Student’s t test. *P < .05; **P < .01; ****P < .0001; ns, not significant

4. DISCUSSION

Hepatocellular carcinoma is one of the most lethal cancers with poor 5‐year survival and high recurrence rates after resection.14 Previous studies in our laboratory have identified many genes that are highly expressed in HCC and linked with its growth and invasion potential, such as OPN, GOLM1, and ACOT12. As in other articles, our preliminary sequencing data found that STMN1 expression in HCC was significantly higher than that in adjacent tissues (data not shown). STMN1 is an oncogene that is highly expressed in many tumors and associated with tumor growth and invasion.9 Previous studies have found that cancer cells can activate STMN1 transcription through the AKT/FOXM1 signaling pathway, which leads to TKI resistance. STMN1 is also associated with OPN overexpression, p53 mutation, tumor progression, early recurrence, and poor prognosis in HCC. In the present study, we confirmed that STMN1 was related to high vascular invasion, low histological differentiation, advanced clinical stage, and poor prognosis in HCC patients. Our in vitro and in vivo experiments verified that STMN1 has a great impact on tumor growth, metastasis, invasion, cancer stemness maintenance, and sorafenib resistance. Together, the results indicated that STMN1 cells are a group of highly malignant cells that affect the survival of HCC patients. These findings enrich our knowledge and understanding of the oncogenic functions of STMN1 in HCC development.

Hepatocyte growth factor/c‐Met axis dysregulation occurs in a variety of solid tumors and hematopoietic malignancies and plays a key role in malignant transformation by promoting tumor cell migration, epithelial‐mesenchymal transition, and invasion. In HCC patients, although MET gene mutation is rare, 20%‐50% of patients have MET pathway activation by means of gene mutation, gene amplification, increased mRNA or protein expression of receptors.15, 16 MET overexpression is associated with rapid tumor growth, worse pathological differentiation, portal vein tumor thrombus, increased vessel invasion, and worse prognosis in HCC patients.17 Currently, targeted drugs for HCC are aimed at a variety of receptor tyrosine kinase, including VEGFR, fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR), PDGFR etc. However, many patients are still insensitive or resistant to existing targeted drugs. HSC in the HCC tumor microenvironment is an important drug‐resistance mechanism for first‐line targeted drugs. They can induce drug resistance by revascularization, MAPK/AKT reactivation, soluble factor secretion, stromal modification, and epigenetic modification.18 C‐Met activity may also confer resistance to sorafenib therapy in HCC.19 Some studies have shown that MET pathway inhibitors can cause HCC resensitization to chemotherapeutic agents by inhibiting these adverse effects. Unfortunately, although some phase I/II clinical trials showed promising results with using MET inhibitors to treat HCC patients, none of the MET inhibitors significantly improved survival in unselected HCC patients in phase III trials.19 MET gene amplification is a valid marker for solid tumor response to MET inhibitors, but the incidence of this mutation is extremely low in HCC.20 Other forms of activated MET mutations are also rare.19 At present, there is still no suitable and generally accepted biomarker to predict overactivation of the MET pathway. Determining how to screen patients who are most suitable for MET inhibitors remains a crucial problem. In the present study, we discovered for the first time that patients with high STMN1 expression had enrichment of the MET pathway genes. The inhibitor and activator of the MET pathway regulated STMN1 at the protein level, and ovSTMN1 cells were more sensitive to the growth‐promoting effect of MET activator HGF in the tumor microenvironment (Figure 4E). These results indicate that STMN1 is regulated by the MET pathway and might be a potential biomarker of MET pathway activation status.

Although previous studies have already reported that STMN1 is related to a worse clinical phenotype and prognosis in various types of cancer, the role that STMN1 plays in the tumor microenvironment remains largely undetermined. HSC are the largest group of cells in the HCC microenvironment, and they promote development and invasion of HCC. HSC can be activated by tumor cells and secrete multiple cytokines to facilitate tumor migration and growth.13, 21, 22 HGF is one of the most important factors derived from HSC. Our IHC staining indicated that STMN1‐high HCC cells were mostly surrounded by activated HSC, which formed a metastasis niche. When HSC were cocultured with HCC cells, HSC secreted more HGF to stimulate the expression of STMN1 in HCC cells. Mutually, STMN1 upregulation in HCC cells facilitated HSC activation to acquire CAF features and increased HGF expression. These findings showed that STMN1 mediated a positive feedback loop between HCC and HSC activation by eliciting the HGF/MET signaling axis. Next, we found that STMN1 dramatically elevated the expression of PDGF‐BB, which is an important PDGF isoform that activates HSC. Considering that STMN1‐mediated crosstalk greatly depended on the activation of the MET pathway in HCC and HSC, the MET inhibitor crizotinib was used to treat the coculture system. In vivo experiments showed that crizotinib showed the most obvious inhibitory effect on tumor growth when both STMN1‐high HCC cells and HSC were cocultured (Figure 7A). This inhibitory effect was consistent with the reduced levels of STMN1 and PDGF‐BB protein in s.c. tumors, which were also downregulated by the MET inhibitor. These findings suggest that, in STMN1‐high HCC, MET inhibitors not only impede cancer cells themselves but also interrupt the crosstalk between activated HSC and cancer cells, which potently inhibits growth of tumor.

This study has some limitations. Crizotinib can effectively target and inhibit the MET pathway, but it can also target the ALK fusion gene. Strictly, crizotinib is not a specific inhibitor of MET. As we know, aberrant ALK gene fusion has been reported in diffuse large B‐cell lymphomas and non‐small cell lung carcinoma, but there are rare ALK gene alterations to be found in HCC. Jia23 examined the status of ALK gene fusion and its clinical significance in 213 HCC samples, but no ALK gene translocation was observed in the large HCC cohort. Comparably, activation of the MET pathway has been widely validated in HCC patients. These findings imply that crizotinib may preferentially target MET compared with the low frequency of ALK gene fusion in HCC. Certainly, it warrants further clarification as to whether crizotinib has effects on other pathways to inhibit HCC growth in addition to MET.

In conclusion, we showed that STMN1 mediates the intricate crosstalk between HCC cells and HSC by triggering the HGF/MET signaling pathway and that PDGF may be responsible for STMN1‐induced HSC activation. The MET inhibitor crizotinib significantly blocks crosstalk and slows tumor growth (Figure 8). STMN1 may hopefully be used as a potential marker to identify patients who benefit from MET inhibitor treatment. Our results provide meaningful preclinical evidence for MET‐targeted therapy in HCC.

Figure 8.

Working model shows that MET inhibitor inhibited the positive feedback loop between high STMN1 hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells and hepatic stellate cells (HSC). STMN1 mediates intricate crosstalk between HCC and HSC by triggering the HGF/MET signal pathway. In the coculture system between HCC cells and HSC, HSC secreted more HGF and activated the MET pathway to increase STMN1 expression in HCC cells, and STMN1 subsequently promoted platelet‐derived growth factor homodimeric protein (PDGF‐BB) expression, which might facilitate HSC activation to acquire cancer‐associated fibroblast characteristics and further elevate hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) protein level. MET inhibitor crizotinib could block the MET pathway to effectively inhibit HCC‐HSC crosstalk and shrink tumor growth when both high STMN1 HCC cells and HSC were coinoculated in mice

DISCLOSURE

Authors declare no conflicts of interest for this article.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by China National Key Projects for Infectious Disease (No. 2017ZX10203207).

Zhang R, Gao X, Zuo J, et al. STMN1 upregulation mediates hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatic stellate cell crosstalk to aggravate cancer by triggering the MET pathway. Cancer Sci. 2020;111:406–417. 10.1111/cas.14262

Contributor Information

Jing Zhao, Email: jingzhao@fudan.edu.cn.

Jinhong Chen, Email: jinhongch@hotmail.com.

REFERENCES

- 1. Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet‐Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA: Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87‐108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tahmasebi Birgani M, Carloni V. Tumor microenvironment, a paradigm in hepatocellular carcinoma progression and therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lin D‐C, Mayakonda A, Dinh HQ, et al. Genomic and epigenomic heterogeneity of hepatocellular carcinoma. Can Res. 2017;77:2255‐2265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Coulouarn C, Clément B. Stellate cells and the development of liver cancer: therapeutic potential of targeting the stroma. J Hepatol. 2014;60:1306‐1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baglieri J, Brenner D, Kisseleva T. The role of fibrosis and liver‐associated fibroblasts in the pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Azzariti A, Mancarella S, Porcelli L, et al. Hepatic stellate cells induce hepatocellular carcinoma cell resistance to sorafenib through the laminin‐332/α3 integrin axis recovery of focal adhesion kinase ubiquitination. Hepatology. 2016;64:2103‐2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Trusolino L, Bertotti A, Comoglio PM. MET signalling: principles and functions in development, organ regeneration and cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:834‐848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Luo Q, Wang C‐Q, Yang L‐Y, et al. FOXQ1/NDRG1 axis exacerbates hepatocellular carcinoma initiation via enhancing crosstalk between fibroblasts and tumor cells. Cancer Lett. 2018;417:21‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hsieh S‐Y, Huang S‐F, Yu M‐C, et al. Stathmin1 overexpression associated with polyploidy, tumor‐cell invasion, early recurrence, and poor prognosis in human hepatoma. Mol Carcinog. 2010;49:476‐487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zheng P, Liu Y‐X, Chen L, et al. Stathmin, a new target of PRL‐3 identified by proteomic methods, plays a key role in progression and metastasis of colorectal cancer. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:4897‐4905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kaposi‐Novak P. Met‐regulated expression signature defines a subset of human hepatocellular carcinomas with poor prognosis and aggressive phenotype. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1582‐1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thompson AI, Conroy KP, Henderson NC. Hepatic stellate cells: central modulators of hepatic carcinogenesis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kang N, Gores GJ, Shah VH. Hepatic stellate cells: partners in crime for liver metastases? Hepatology. 2011;54:707‐713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Villanueva A. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1450‐1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ueki T, Fujimoto J, Suzuki T, Yamamoto H, Okamoto E. Expression of hepatocyte growth factor and its receptor c‐met proto‐oncogene in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 1997;25:862‐866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee SJ, Lee J, Sohn I, et al. A survey of c‐MET expression and amplification in 287 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:5179‐5186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wu F, Wu L, Zheng S, et al. The clinical value of hepatocyte growth factor and its receptor—c‐met for liver cancer patients with hepatectomy. Dig Liver Dis. 2006;38:490‐497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kadel D, Zhang Y, Sun H‐R, Zhao Y, Dong QZ, Qin LX. Current perspectives of cancer‐associated fibroblast in therapeutic resistance: potential mechanism and future strategy. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2019;35:407‐421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bouattour M, Raymond E, Qin S, et al. Recent developments of c‐Met as a therapeutic target in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2018;67:1132‐1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Frampton GM, Ali SM, Rosenzweig M, et al. Activation of met via diverse exon 14 splicing alterations occurs in multiple tumor types and confers clinical sensitivity to met inhibitors. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:850‐859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Friedman SL. Hepatic stellate cells: protean, multifunctional, and enigmatic cells of the liver. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:125‐172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. van Zijl F, Mair M, Csiszar A, et al. Hepatic tumor–stroma crosstalk guides epithelial to mesenchymal transition at the tumor edge. Oncogene. 2009;28:4022‐4033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jia S‐W. Alk gene copy number gain and its clinical significance in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(1):183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials