Abstract

Background.

Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) due to alcohol use disorder (AUD) is the primary cause of liver transplantation (LT) in the United States. Studies have found that LT recipients experience a range of physical and emotional difficulties posttransplantation including return to alcohol use, depression, and anxiety. The aim of this study is to better understand the experiences of LT recipients with ALD because they recovered posttransplant to inform the development of a patient-centered intervention to assist patients during recovery.

Methods.

Using qualitative methods, researchers conducted semi-structured interviews with 16 ALD LT recipients. The primary topics of the interview were physical recovery, mental health, substance use including alcohol and tobacco use, and financial experiences. Common patient themes were identified and coded.

Results.

Within the domain of physical health, patients stressed that undergoing LT was a near-death experience, they were helpless, changes in weight influenced their perception of their illness, and they have ongoing medical problems. In the domain of mental health, patients described cognitive impairments during their initial recovery, difficulty in processing the emotions of having a terminal condition, ongoing depression, anxiety, and irritability. The patients also described their perception of having AUD, the last time they used alcohol and their attitude to AUD treatment posttransplant. Patients also described their reliance on one member of their social support network for practical assistance during their recovery and identified one member of their medical team as being of particular importance in providing emotional as well as medical support during recovery.

Conclusions.

The patient’s description of their lived experience during the months following transplant informed the development of a patient-centered intervention that colocates behavioral health components with medical treatment that helps broaden their social network while addressing topics that emerged from this study.

Alcoholic liver diseases (ALDs; an array of conditions, including cirrhosis, caused by the consumption of alcohol1) are the leading indicator for liver transplant (LT) in the United States.1,2 ALD is often a result of alcohol use disorder (AUD), which is a chronic condition typified by a pattern of consuming alcohol despite severe impairment in daily functioning, often with numerous failed attempts of abstaining.3 The current study endeavors to further elucidate the needs of LT recipients with ALD during their recovery by analyzing patients’ perspectives on their experiences pre- and posttransplant.

Patients with a history of AUD have an elevated risk for alcohol use and increased risk of mortality, resulting in higher cost of care due to ongoing liver disease.4 One study5 reported that 8%–22% of LT recipients return to alcohol use within the first-year posttransplant, and another6 found that within 5 years posttransplant, 30%–40% of LT recipients have used alcohol.

Despite these high rates of return to alcohol use, LT recipients have demonstrated low compliance with AUD treatment. Weinrieb et al7 found that less than half of the participants recruited to their study attended 4 of the 7 AUD treatment sessions offered. The authors attributed the low completion rate, in part, to a lack of desire by LT recipients to engage in AUD treatment, reinforcing the lessons learned, in a previous study,8 in which the researchers could not recruit any LT recipients to participate in a study which provided AUD treatment.

Heyes9 conducted 2 qualitative studies aimed at understanding the reluctance of LT recipients to receive AUD treatment. One study compared people without ALD who sought AUD treatment to ALD transplant recipients.10 They found that ALD participants were more likely to have a supportive partner, stable housing, broader support, and were more likely to have been abstinent for longer periods than the non-ALD treatment-seeking group. The authors concluded that the ALD group may have perceived treatment to be unnecessary because they understand that these protective factors discourage disordered drinking.

In the second study, Heyes et al11 asked the members of the ALD group about their experiences of recovery from AUD and liver transplantation. Among the themes that emerged, many participants explained that they wanted to “handle their AUD on their own,”11 even preferring not to report relapse to their medical team. Participants reported that social support from family and friends helped them maintain abstinence in lieu of formal AUD treatment. Third, participants indicated that a lack of integrated care for addiction in LT settings made them reluctant to seek options for AUD treatment outside of the medical setting. This was compounded by weak communication from the medical team on issues pertaining to alcohol use.11 Finally, participants perceived that participation in AUD treatment would stigmatize them and label them as “alcoholic,” a term associated with character failings. Because abstinence was stressed by the medical team pretransplant, the patients also reportedly felt embarrassed or intimidated by discussing with them relapse posttransplant.

LT recipients with ALD are also at higher risk for other mental health issues. DiMartini et al12 found that during the year following LT, 57% of the sample of ALD patients had consistently low depressive scores, 25% demonstrated depression increasing to moderate to high scores, and 18% with consistently moderate to high Beck Depression Inventory scores, while controlling for the effects of underlying medical conditions.12 Additionally, those who have survived an organ transplant experience anxiety regarding graft rejection, over-medicalization of life,13 trouble re-establishing normality,14 and the patient’s struggle to understand their position in life.15

Several studies have also found that patients face other psychosocial difficulties. They are unlikely to return to work posttransplant, and loss of income or financial stress are difficulties commonly faced by LT recipients.16–18 Health-related sequelae19 and medical noncompliance20,21 are other common challenges.

Previous research has identified issues that patients face during their recovery from liver transplantation; however, there have been few studies in the United States that have sought the patient’s perspective on the challenges they have and the care they receive. This study seeks to use patients’ experience and outlook as a first step in the development of a patient-centered intervention that will be colocated with their follow-up medical appointments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

To better understand the experiences of LT recipients with ALD as they recovered posttransplant, researchers interviewed 16 patients and analyzed their responses using a through content analysis qualitative method.22,23 This approach is well tailored to seek commonalities in complex and personal struggles, achievements, and attitudes that comprise the process of recovering from liver transplantation and AUD.

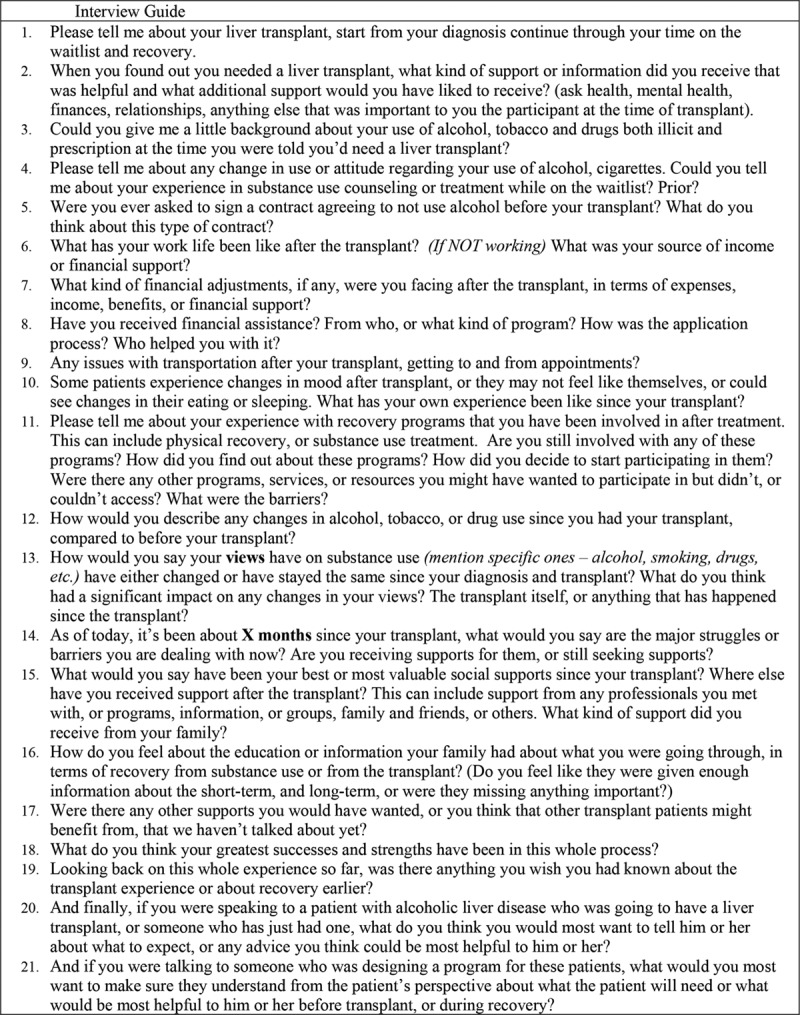

The researchers developed an interview guide in collaboration with a patient partner, an individual who had received a LT for ALD and could provide valuable first-hand experience to help contextualize and organize questions about the transplant and recovery experience during recovery. The interview guide included open questions and asked for the participants to relate their experiences on their physical recovery, mental health, substance use including alcohol and tobacco use, and financial experiences (Figure 1). Previous studies indicated that these may be areas in which patients’ needs are not met in the current medical model, and patients’ perspectives would help shape the proposed intervention to best meet them. Because many transplant recipients resided at a distance from the hospital, the authors decided to conduct telephone interviews to assist in recruitment by reducing the participant’s time commitment.

FIGURE 1.

Interview guide.

After receiving Institutional Review Board approval, researchers mailed an invitation letter to surviving patients, with an ALD diagnosis, who received a transplant between January 1, 2016, and June 30, 2017, and who were also between 6 and 18 months posttransplant, at a teaching hospital in a large urban area in a Mid-Atlantic state. This time-frame allowed participants to recall recent events and provided patients with time to regain most physical functioning. Researchers continued recruitment by telephone from a list of potential participants: 7 patients who personally answered the call by the researchers declined to participate, and none of the over 50 voicemail messages from the researchers was returned. Each potential participant was informed that the study was optional, would not impact medical care, and would comprise one 60- to 90-minute telephone interview. Participants received a $50 gift card for completing the interview. Pseudonyms are used to protect participants’ privacy.

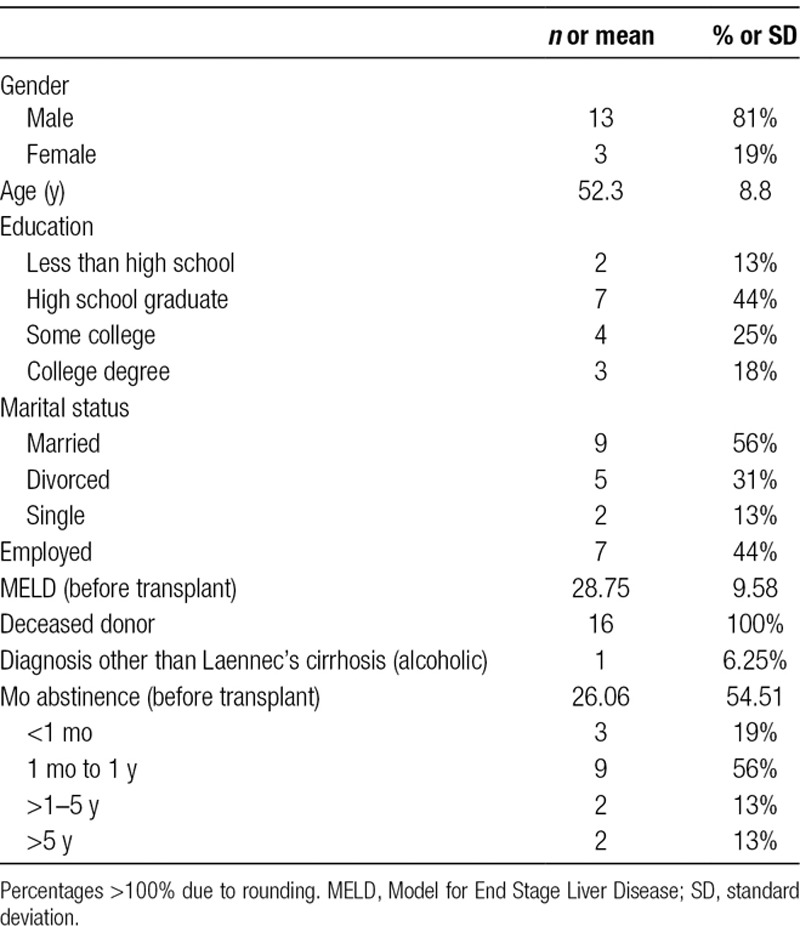

Thirteen males and 3 females, who received a LT from a deceased donor, were interviewed (Table 1). Ages ranged from 35 to 63 years (mean, 52.3; SD, 8.8) and were almost identical for males (mean, 52.4; SD, 9.6) and females (mean, 52; SD, 5.56). This was comparable to the total population of ALD LT recipients at the recruitment hospital in 2015 (75% male, 25–69 y old; mean, 54.24; SD, 10.5 for men; and mean, 45.71; SD, 10.4 for women). Study participants were more racially homogeneous; 100% were white, while 70% of aforementioned patients in 2015 were white, 24% African-American, and 6% Latino. None of the participants were required to undergo alcohol treatment before transplantation, although some were advised to seek treatment and others voluntarily participated in formal treatment or Alcoholics Anonymous (AA).

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants

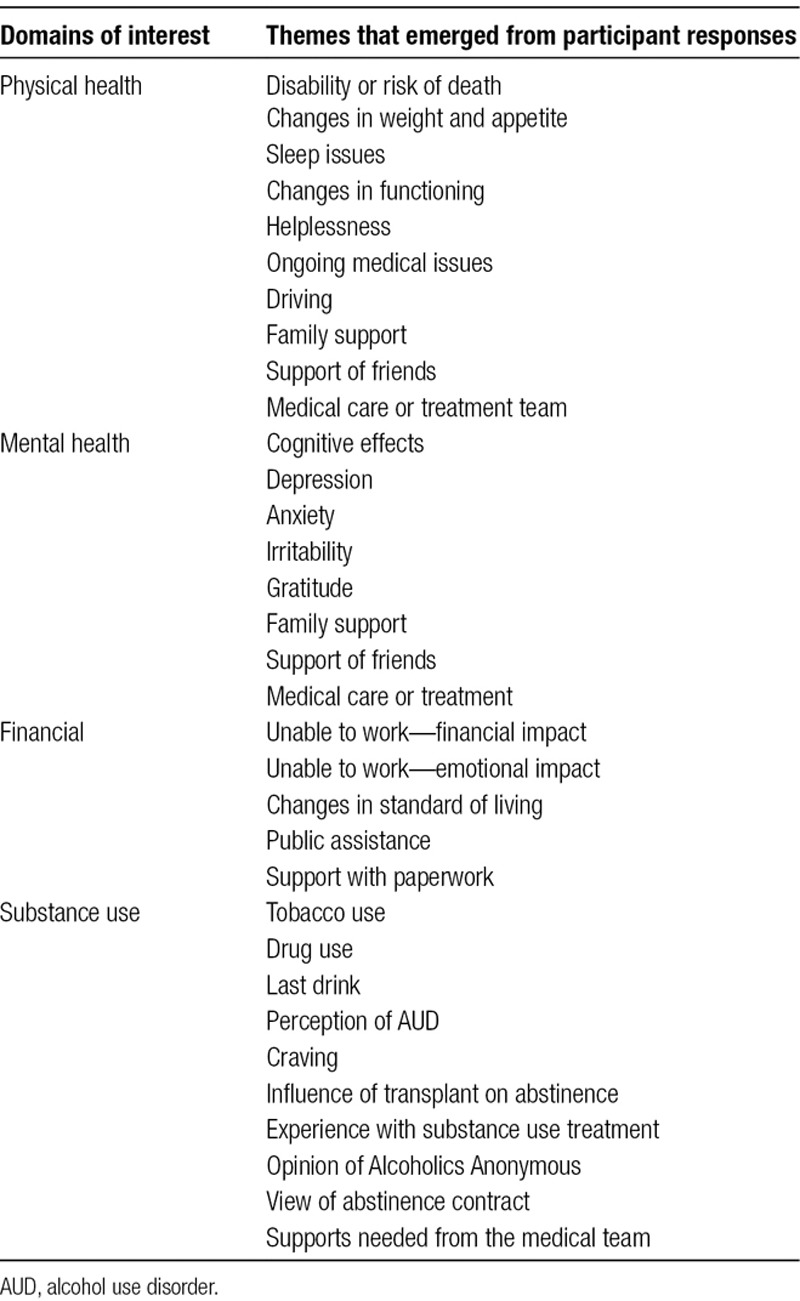

Two of the authors (M.H., M.L.M.) conducted semi-structured interviews which typically lasted 1 hour but ranged from 33 to 105 minutes. Interview transcriptions were read by each of the authors and the patient partner each of whom independently created coding schemes based on their interpretation of the patients’ answers. The authors and patient partner met and discussed similarities and differences between their proposed coding schemes before settling on themes in each domain of inquiry that were proposed by several members of the team. Two of the authors (M.H., M.L.M.) reread each of the transcripts and extracted quotes which reflected the agreed upon codes (Table 2) (disagreement was decided by discussion). All of the authors and patient partner were able to review the extracted quotations and comment about their position in the coding scheme.

TABLE 2.

Structured coding scheme

Following the quality criteria described by Mays and Pope,24 the authors elicited feedback from the patient partner and members of the medical team, as a forms of triangulation, to ensure that the coding scheme was representative of the discussions that are observed in the medical clinic. The patient partner’s feedback additionally provided a form of respondent validation. The interviewers also summarized and reflected each answer to the participant to elicit further clarification. The coding scheme developed included areas that many of the participants addressed, and themes included in the results reflect those of the majority, unless disagreement is noted. The researchers attempted to be inclusive by reaching out to all living LT recipients and the experiences of the sample are known to be consistent with other ALD LT recipients in the hospital based on quantitative data collected from a larger sample of ALD LT recipients in the same hospital,25 concurrence of the medical team, and published quantitative and qualitative research of ALD LT recipients in other hospitals in the United States.26

RESULTS

Participants described their experiences of recovery from liver transplantation and AUD and shared comments on supports they had relied on or desired. While each person is unique in circumstances and views, some predominant patterns could be observed.

Physical and Mental Health

Helplessness

Most participants (14) described being helpless after the transplant. The degree and type of debilitation varied, but almost all participants described noticeable changes to their physical strength and functioning, and helplessness in terms of fatigue or weakness and temporary inability to walk.

Your body is reduced to that of a baby. You have to re-learn how to get out of bed and be able to stand up. Then you have to be able to not fall over.—Chris

It just seemed like I was tired all the time…Before, I had energy. I was always doing something. But it’s just like I couldn’t. I was just too tired to do anything.—Catherine

Changes in Weight and Appetite

A symptom of ALD is loss of appetite, and as expected, most participants lost weight before transplant. Dramatic weight loss continued postoperatively and was often reversed as the participant was restored to health. Participants seemed attuned to changes in their weight and appetite and often volunteered this information to interviewers as measures of their overall health.

I went from 210 down to 140 [pounds]. I wouldn’t eat. I just had no taste to eat, no desire to eat. Sometimes there were times I didn’t even care if I lived or died the first couple months...After a while, I got to where I was eating and stuff. I got to feeling better…After they took that feeding tube out, then I really started eating.—Larry

Jerry lost 60 pounds in early recovery and described his struggles with eating and weakness:

I quit looking at myself in the mirror because I looked like a prisoner of war from World War II is how bad I looked, how much weight I had lost…I just stayed in bed. [My wife] would bring me a sandwich. I’d take a bit of it. Five minutes later, I’d throw up and I’d go back to sleep. I was so tired and weak.

Ongoing Medical Problems

Almost all participants reported ongoing medical problems, some of which they believed were sequela of ALD and some from their current antirejection medications. It was apparent that participants and their healthcare providers must continue to monitor and treat various health issues for a long period after transplant.

Cognitive Impairment

Almost all participants mentioned remembering little about the period immediately prior and posttransplant. Peter’s description is typical: “Getting my mental acuity back, that took longer. I was fuzzy, like all the time. I was just slow for a long time. …It came back, but it just took a while.” However, none of the participants reported being either assessed or diagnosed with covert hepatic encephalopathy.

Near-Death Experience

Fifteen of 16 participants described their diagnosis as terminal or shared an incident in which they were close to dying before receiving their transplant.

When...I found out that I needed a liver, the real conversation was sort of about how I wouldn’t be getting one. The conversation was more about how I was terminal. I was dying.—Adam

Jack reported “[The gastroenterologist] said, ‘Well, you definitely have cirrhosis, and if you don’t stop drinking, you’re going to die, and you’re probably going to die anyway.’”

Participants described significant impacts on their emotional state from their thoughts and beliefs about either anticipating death or having survived.

I was done… My husband said . . . do you really not want to see your sons get married and possibly grandkids? . . . That was the ‘ah-ha’ moment for me.—Mary

[After surviving], I just kind of tried to drop all my baggage then, and leave it there, and start a new life, so to speak.—Rose

Depression/Anxiety

Many of the participants reported experiencing feelings of anxiety or depression due to the transplant. Anxiety was usually directly related to the inherent risk of transplant (eg, rejection, infection), which abated over time. Six participants described symptoms of depression, including feelings of isolation, anhedonia, and lethargy which they associated with their transplant.

George described becoming anxious when he noticed physical symptoms after transplant and sought explanations. “You get all these thoughts running through your head when you don’t get an answer. You start playing out a scenario. What if this happened? Or what if this happened?”

Jack described his depression and why it was difficult to seek help:

I would just cry over everything. I mean, it wouldn’t matter what it was, because it’s a life that you feel like that you cheated death, and it’s just emotional. It’s very emotional… most people aren’t going to come out and say, you know, “I feel depressed, and I cry all the time.”

Irritability

Most participants commented on their irritability and made a connection between the surgery and their mood. While some attributed their irritability to their pain, limitations, and burdens in early recovery, others reported feeling more calm or positive after transplant.

“I had horrific mood swings. I picked a horrible fight with my…two biggest support[s].”—Rose, describing the initial weeks following her transplant.

Since my liver transplant, I have a complete turnaround as far as a positive attitude goes. I used to be--I don’t want to say a very negative person…My mood is better. Much, much better.—Tim

Alcohol Use and AUD Recovery

All participants were diagnosed with ALD and were asked about their alcohol use history and current alcohol use. Twelve participants admitted that they had AUD, while 2 were unsure, and 2 denied having a problem with alcohol. Those who acknowledged having AUD were, like Jack, typically upfront and open about their problem. “I’ve always been a functional alcoholic and drug addict. I’m not saying that to be--I’ve always taken care of all my priorities.”

Eleven participants stopped drinking before their ALD diagnosis, offering varying reasons as to why. Some described suddenly losing the desire to drink after years; others expressed how they reached the conclusion that their alcohol use was having negative consequences.

I stopped on my own… Stopped drinking totally. Just one day, that’s it…It was just-- the drinking I guess wasn’t really meeting my needs. It was fun. [Then] it wasn’t fun.—Mary

I had already started [alcohol treatment] about two weeks before being hospitalized, because I just felt that it was time...Everybody reaches their breaking point.—George

I knew that the life that I was living was just – I couldn’t continue. I had two choices. I could either live or I was going to die, and I know something had to give, something had to change.—Peter

Most participants related either that they have no desire to drink or that their desire to drink is outweighed by their knowledge that continued drinking will damage their new liver and result in death.

It’s not like I have a burning desire or anything. It might be nice to have a drink every now and then, but I know I can’t do it. Just speaking for--I know I can’t do it...absolute no-no. And they told me, because of the fact that I was a daily drinker and the way I drank, that if I did, I’d probably last about a year before I blow up my liver...When you get that liver transplant, you can’t do it anymore, period. You just can’t. If you do, you will die. You will die.—Tom

Jerry’s statement was typical of those who claimed not to have any desire to drink: “Once I detoxed, I never had the urge. I never had the craving… which is great. I thank the powers that be for not having that craving.”

George was among only 3 participants described abstinence as difficult: “The cravings are still there. To this day, I could take a drink out of a five-gallon bucket and drink the whole damn thing. The cravings are still there.”

Alcohol Treatment

Most commonly participants stated that they do not fear their return to drinking and, therefore, do not need any further AUD treatment. For most, this was due to having stopped drinking before they were diagnosed with ALD. Others described feeling that their LT was enough to motivate them to abstain from alcohol with no need for follow-up AUD treatment.

After the transplant, I went to AA a handful of times. I know it’s a great program, don’t get me wrong, but I just, I felt like it wasn’t for me . . . I got a life education. I basically got, “Look dude. You screwed up big time. You’re in a live or die situation.”—Steve

All but 3 of participants did not attend any AUD treatment posttransplant either professional or self-help. Two of the 3 who participated in AUD treatment were members of AA who stopped using alcohol via AA and continued their participation posttransplant. The 13 participants who did not receive posttransplant treatment expressed similar reactions to Steve (above) that they did not need AUD treatment and that they did not wish to participate.

They asked me if I wanted information, and I just told them no. Because I’m not the type of person to--socialistic person, so to speak, to go to AA meetings or want support or anything. They offered it to you, but that wasn’t something you felt that you needed to participate in. That is correct.—Tim

I went to AA a couple times, but it’s not--I don’t consider--AA’s kind of touch and go. . . . it’s not a cure. I guess if--it’s a cure if you go 7 days a week, every time you get an urge, I guess. I just don’t have the urge to drink.—Jack

Social Supports

Family and Friends

Almost every participant identified one person in their immediate family who provided significant practical support early in their recovery. This person was described as supporting the participant’s physical and mental health, as well as assisting in applying for financial assistance. While participants described >1 immediate family member or friends in their emotional support system, they often appeared to rely heavily on one close relative for practical assistance, such as providing transportation, organizing medication, preparing meals, and supporting mobility.

Medical Team

Nearly all participants complimented their medical and surgical team and extolled their skills, although some participants described negative incidents that occurred while under care, mostly with hospital staff. Significantly, half of the participants described a relationship with a single member of their medical team (doctor, nurse, or transplant coordinator) that significantly improved the experience and defined their opinion of the medical team.

DISCUSSION

Our findings suggest that the perspective of patients with ALD who receive a LT is shaped by the traumatic nature of life-threatening illness itself. Transplant patients tended to see the transplant itself as a kind of treatment, and they did not, as a group, identify alcohol use as an ongoing risk for them. Because they did not see alcohol as a specific issue, the themes that ALD transplant recipients focused on in their interviews were similar to those received a LT for other reasons and included prolonged physical, emotional, and mental health recovery. In the process of recovery, they reported relying on a relatively small group of core support people.

The participants in the current study perceived LT as a life or death experience that transformed them in profound ways. They felt that recognizing their own mortality changed their relationship with alcohol and drinking. Other studies have identified similar processes whereby life-threatening illness prompts positive changes in health behavior secondary to cardiac events.27 Based on the Health Belief Model,28,29 the experience of going through a LT may lead individuals to have a greater sense of perceived susceptibility and severity of their illness and the risks associated with returning to drinking.

Going from a terminal prognosis to receiving a second chance may alter one’s beliefs about the importance of positive health behaviors and increase the sense that behavior can make a difference. In a recent study by Elliott et al,30 the authors concluded that those who had a belief that Hepatitis C Virus/HIV inevitably led to bad outcomes drank more than those who did not have those beliefs. It is possible that the hope engendered by a LT combined with the trials they endure during recovery alter their beliefs about drinking.

In the current study, few respondents were concerned about returning to drinking, citing the transplant experience. This finding is consistent with the work by Heyes et al11 and more recently by Mellinger et al26 who documented low levels of formal treatment acceptance among ALD transplant patients. While relapse and treatment are a primary concern for providers, patients may see alcohol as a secondary issue. Even so, between 30% and 40% of individuals who receive a transplant use alcohol within 5 years after transplant,31 and a small percentage of ALD transplant recipients will again engage in heavy drinking.

The fact that the participants did not view themselves as needing further AUD treatment may put them at greater risk of return to use because some evidence suggests that treatment after transplant is associated with lower rates of return to alcohol use.32 Because patients do not believe they need further AUD treatment, they will be reluctant to attend formal treatment or participate in studies related to AUD treatment. This may help explain the contention of Day et al33 that there is no standardized protocol of care for ALD LT and that there are few conclusive data indicating best practices in this area.

LT recipients reported experiencing cognitive problems during the graft process; it is possible that efforts to educate patients during hospitalization and follow-up outpatient care may not be effective. Findings from studies conducted at the time of discharge suggest that patients may not remember even basic information such as medications and diagnosis.34 ALD LT patients may have even more difficulty retaining important information due to cognitive problems secondary to heavy alcohol use35 and/or liver disease.36

Problems with mental health functioning may also extend to mood and anxiety problems. In the current study, many participants reported depression, anxiety, and irritability in the period after transplantation. A recent study suggests that psychiatric conditions (ie, adjustment disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder anxiety disorder, and depression) are more common among individuals with ALD than among those who have a liver disease that is not related to alcohol use.37 Other research has found that depression and anxiety are lower 1 year after liver transplantation among persons with ALD, suggesting that individuals show adjustment posttransplant,38 but trajectories of depression may vary considerably by patient as described by DiMartini et al.12 Mental health symptoms are not always problematic for ALD patients receiving a transplant, but our findings suggest that they are common.

The current study reinforced the idea that social support in crisis situations is deep but narrow. Respondents related that one or a small number of people provided the bulk of assistance to them through the transplantation process. Research suggests that social support levels are lower among ALD LT patients than among non-ALD LT patients39 and lower than national norms.25 This is important as a tenuous support system may become frayed during and after the posttransplantation process. Caregiver burden may lead to emotional problems on the part of the caregiver that persist after the transplant itself.40 Evidence from a meta-analysis suggests that social support is not associated with medication compliance and survival among transplant recipients,41 even as clinicians use it as a means of making listing decisions.42 Still, among ALD LT patients, lack of social support may be associated with alcohol relapse posttransplant43 and impaired quality of life among transplant recipients.

As described, the results of this US-based study concur with previous studies performed in other countries and medical systems. This helped to address the limitations of small sample size and ethnic homogeneity, as well as demonstrate that possible barriers to patient participation were overcome.

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings suggest that efforts to connect ALD LT recipients with formal treatment for AUD may be ineffective because ALD transplant recipients do not see themselves as being at high risk of problematic alcohol use. Heyes et al,11 interviewing a sample of Australian ALD LT patients, also identified that patients were reluctant to engage in formal treatment. Heyes et al10 have advocated for behavioral health integration in medical transplant settings. Similarly, in a review of treatment interventions for people with chronic liver disease and AUD, Khan et al44 found that integration of AUD treatments into comprehensive medical care increased alcohol abstinence. The current study reinforces this conclusion among ALD LT recipients in the context of the US healthcare system, where efforts at behavioral health integration in primary care are ongoing,45 but where integration in the treatment of liver disease is still emerging.46 The perspectives of the patients in this study support the idea that mental health and addiction interventions should be incorporated into overall care for ALD transplant recipients and should include attention to family and other psychosocial factors.

Based on these findings, the authors are developing an intervention which colocates behavioral health treatment within the medical clinic that includes individual and group counseling which will continually screen for mental health issues, provide social support, and obliquely (rather than directly) address the potential for return to alcohol use.

Footnotes

Published online 15 November, 2019.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This work was supported by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality #5R24HS022135-04/PI.

M.H. conducted interviews and participated in creating coding scheme, coding transcripts, and writing the preliminary draft of the article. M.L.M. participated in research design and creating coding scheme, conducted interviews, participated in coding transcripts, and contributed to major editing of the draft. M.T. and J.L.M. and M.C. participated in research design, reviewed coding scheme, and reviewed and edited the article. P.S. conceptualized the study and provided oversight of research design, participated in creating coding scheme and writing preliminary draft of the article, and reviewed and substantially edited the final article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cholankeril G, Ahmed A. Alcoholic liver disease replaces hepatitis C virus infection as the leading indication for liver transplantation in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018161356–1358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee BP, Vittinghoff E, Dodge JL, et al. National trends and long-term outcomes of liver transplant for alcohol-associated liver disease in the United States. JAMA Intern Med 2019179340–348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Potts JR, Goubet S, Heneghan MA, et al. Determinants of long-term outcome in severe alcoholic hepatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 201338584–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Everson G, Bharadhwaj G, House R, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with alcoholic liver disease who underwent hepatic transplantation. Liver Transpl Surg 19973263–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lucey MR, Brown KA, Everson GT, et al. Minimal criteria for placement of adults on the liver transplant waiting list: a report of a national conference organized by the American Society of Transplant Physicians and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Transplantation 199866956–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinrieb RM, Van Horn DH, Lynch KG, et al. A randomized, controlled study of treatment for alcohol dependence in patients awaiting liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 201117539–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinrieb RM, Van Horn DH, McLellan AT, et al. Alcoholism treatment after liver transplantation: lessons learned from a clinical trial that failed. Psychosomatics 200142110–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heyes CM. Barriers and Resistance to Speciality Alcohol Treatment amongst Alcoholic Liver Disease Transplant Candidates Preceding and Following Liver Transplantation. Sydney, NSW, Australia: Drug and Alcohol Studies, University of Sydney; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heyes CM, Baillie AJ, Schofield T, et al. The reluctance of liver transplant participants with alcoholic liver disease to participate in treatment for their alcohol use disorder: an issue of treatment matching? Alcohol Treat Q 201634233–251 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heyes CM, Schofield T, Gribble R, et al. Reluctance to accept alcohol Treatment by alcoholic liver disease transplant patients: a qualitative study. Transplant Direct. 2016;2:e104. doi: 10.1097/TXD.0000000000000617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiMartini A, Dew MA, Chaiffetz D, et al. Early trajectories of depressive symptoms after liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease predicts long-term survival. Am J Transplant 2011111287–1295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jamieson NJ, Hanson CS, Josephson MA, et al. Motivations, challenges, and attitudes to self-management in kidney transplant recipients: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Am J Kidney Dis 201667461–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boaz A, Morgan M. Working to establish ‘normality’ post-transplant: a qualitative study of kidney transplant patients. Chronic Illn 201310247–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palesjö C, Nordgren L, Asp M. Being in a critical illness-recovery process: a phenomenological hermeneutical study. J Clin Nurs 2015243494–3502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stiavetti E, Ghinolfi D, Pasetti P, et al. Analysis of patients’ needs after liver transplantation in Tuscany: a prevalence study. Transplant Proc 2013451276–1278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saab S, Wiese C, Ibrahim AB, et al. Employment and quality of life in liver transplant recipients. Liver Transpl 2007131330–1338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aberg F, Rissanen AM, Sintonen H, et al. Health-related quality of life and employment status of liver transplant patients. Liver Transpl 20091564–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bravata DM, Olkin I, Barnato AE, et al. Health-related quality of life after liver transplantation: a meta-analysis. Liver Transpl Surg 19995318–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schulz K-H, Kroencke S. Psychosocial challenges before and after organ transplantation. Transplantation Research and Risk Management 2015745–58 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dew MA, DiMartini AF, De Vito Dabbs A, et al. Rates and risk factors for nonadherence to the medical regimen after adult solid organ transplantation. Transplantation 200783858–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health 200023334–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 200862107–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mays N, Pope C. Qualitative research in health care. Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ 200032050–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sacco P, Sultan S, Tuten M, et al. Substance use and psychosocial functioning in a sample of liver transplant recipients with alcohol-related liver disease. Transplant Proc 2018503689–3693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mellinger JL, Scott Winder G, DeJonckheere M, et al. Misconceptions, preferences and barriers to alcohol use disorder treatment in alcohol-related cirrhosis. J Subst Abuse Treat 20189120–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holder GN, Young WC, Nadarajah SR, et al. Psychosocial experiences in the context of life-threatening illness: the cardiac rehabilitation patient. Palliat Support Care 201513749–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hochbaum G, Rosenstock I, Kegels S. Health Belief Model. Washington D.C.: United States Public Health Service; 1952. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Janz NK, Becker MH. The health belief model: a decade later. Health Educ Q 1984111–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elliott JC, Hasin DS, Des Jarlais DC. Perceived risk for severe outcomes and drinking status among drug users with HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV). Addict Behav 20166357–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee BP, Terrault NA. Early liver transplantation for severe alcoholic hepatitis: moving from controversy to consensus. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 201823229–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodrigue JR, Hanto DW, Curry MP. Substance abuse treatment and its association with relapse to alcohol use after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2013191387–1395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Day E, Best D, Sweeting R, et al. Detecting lifetime alcohol problems in individuals referred for liver transplantation for nonalcoholic liver failure. Liver Transpl 2008141609–1613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Makaryus AN, Friedman EA. Patients’ understanding of their treatment plans and diagnosis at discharge. Mayo Clin Proc 200580991–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Houston RJ, Derrick JL, Leonard KE, et al. Effects of heavy drinking on executive cognitive functioning in a community sample. Addict Behav 201439345–349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Collie A. Cognition in liver disease. Liver Int 2005251–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jinjuvadia R, Jinjuvadia C, Puangsricharoen P, et al. ; Translational Research and Evolving Alcoholic Hepatitis Treatment Consortium Concomitant psychiatric and nonalcohol-related substance use disorders among hospitalized patients with alcoholic liver disease in the United States. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 201842397–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pegum N, Connor JP, Young RM, et al. Psychosocial functioning in patients with alcohol-related liver disease post liver transplantation. Addict Behav 20154570–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garcia CS, Lima AS, La-Rotta EIG, et al. Social support for patients undergoing liver transplantation in a public university hospital. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16:35. doi: 10.1186/s12955-018-0863-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Young AL, Rowe IA, Absolom K, et al. The effect of liver transplantation on the quality of life of the recipient’s main caregiver: a systematic review. Liver Int 201737794–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ladin K, Daniels A, Osani M, et al. Is social support associated with post-transplant medication adherence and outcomes? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transplant Rev (Orlando) 20183216–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ladin K, Emerson J, Butt Z, et al. How important is social support in determining patients’ suitability for transplantation? Results from a national survey of transplant clinicians. J Med Ethics 201844666–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rustad JK, Stern TA, Prabhakar M, et al. Risk factors for alcohol relapse following orthotopic liver transplantation: a systematic review. Psychosomatics 20155621–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khan A, Tansel A, White DL, et al. Efficacy of psychosocial interventions in inducing and maintaining alcohol abstinence in patients with chronic liver disease: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 201614191–202.e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mechanic D. More people than ever before are receiving behavioral health care in the United States, but gaps and challenges remain. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014331416–1424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Verma M, Navarro V. Patient-centered care: a new paradigm for chronic liver disease. Hepatology 201562988–990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]