Abstract

Purpose:

To determine effects of continued or discontinued use of omega-3 (ω3) fatty acid supplements through a randomized withdrawal trial among patients assigned to ω3 supplements in the first year of the DREAM study.

Methods:

Patients who were initially assigned to ω3 (3000 mg) for 12 months in the primary trial were randomized 1:1 to ω3 active supplements or placebos (refined olive oil) for 12 more months. The primary outcome was change in the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) score. Secondary outcomes included change in conjunctival staining, corneal staining, tear break-up time, Schirmer test, and adverse events.

Results:

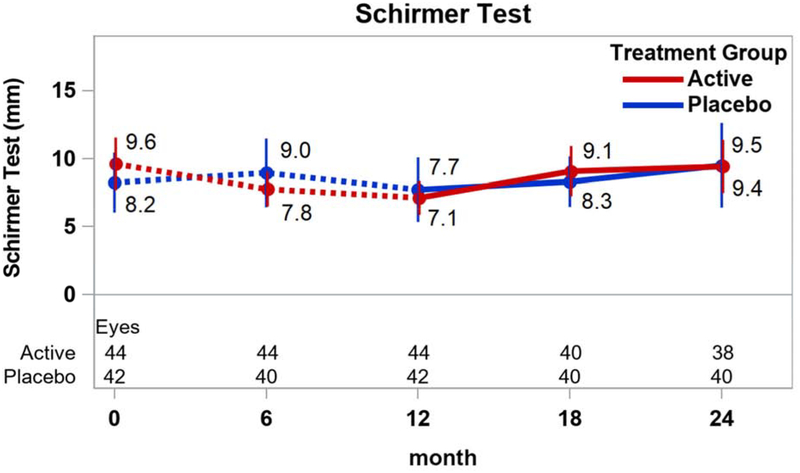

Among 22 patients assigned to ω3 and 21 to placebo supplements, the mean change in OSDI score between month 12 and 24 was similar between treatment groups (mean difference in change −0.6 points, 95% confidence interval [CI], (−10.7, 9.5), p= 0.91). There were no significant differences between groups in mean change in conjunctival staining (difference in mean change −0.5 points; 95% CI (−1.2, 0.3)), corneal staining (−0.3 points; 95% CI (−1.2, 0.3)), tear break-up time (−0.8 seconds; 95% CI (−2.6, 0.9)) and Schirmer test (0.6 mm, 95% CI (−2.0, 3.2)). Rates of adverse events were similar in both groups.

Conclusion:

Among patients who received ω3 supplements for 12 months in the primary trial, those discontinuing use of ω3 for an additional 12 months did not have significantly worse outcomes compared to those who continued use of ω3.

Keywords: dry eye disease, omega-3 fatty acids, randomized clinical trial

1. INTRODUCTION

Dry eye disease (DED) is a common chronic disorder that results in ocular discomfort, fatigue, visual disturbance and pain, thereby affecting overall quality of life.1–5 DED is one of the most frequently encountered ocular morbidities6 and is considered one of the top 3 most prevalent chronic eye diseases, together with glaucoma and age-related macular degeneration.7–10 Nearly 14% of Americans, 50 years and older, of all races, and more commonly women, are affected by dry eye disease.1,11,12 The average cost of managing DED in the US is estimated at more than $55 billion annually, including healthcare costs and loss of productivity.13 Standard treatments for DED include use of artificial tears and lubricating ointments, anti-inflammatory drops, lid scrubs and punctal occlusion. Although the pathogenesis of DED is multifactorial, inflammation of the ocular surface has been shown to be an important component of dry eye disease.5,14

There have been several reports of small clinical trials to support the role of ω3 fatty acids in the treatment of DED.15–20 However, outcome measures, dosing, composition, and length of treatment with ω3 have varied across these trials. We are unaware of any previous reports of the effects on DED of withdrawing ω3 supplements from current users.

The Dry Eye Assessment and Management (DREAM) trial was a large-scale, multicenter, randomized controlled trial that reported no difference between ω3 and placebo supplement groups on symptoms and signs of DED, although both groups showed improvement in symptoms over time.21 The purpose of the DREAM extension trial is to determine effects of continued use or discontinuation of ω3 through a randomized withdrawal trial among subjects who were assigned to ω3 in year one of the study. The extension trial aims to provide information on long-term safety and sustainability of any treatment effect by evaluating data for return of signs and symptoms of DED after withdrawal of ω3 treatment.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Subjects

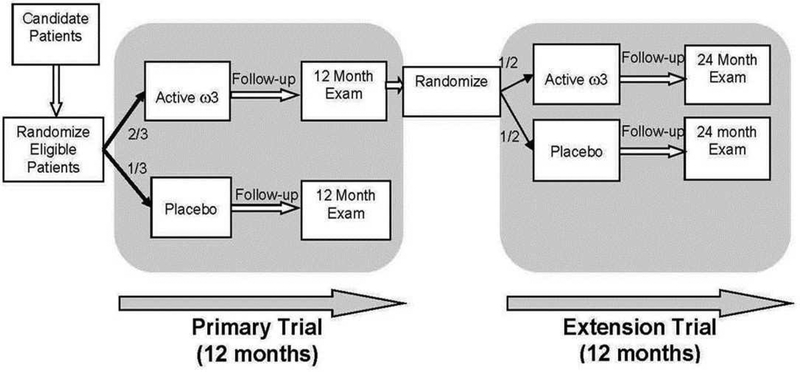

The DREAM Study was a prospective, multi-center, double-masked, randomized, clinical trial. Participants were enrolled from 27 centers throughout the United States. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained at each center and the trial adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The trial was carried out under a Food and Drug Administration Investigational New Drug application and was registered with clinicaltrials.gov (.) A detailed description of the primary trial design and methodology has been published.22 Participants who completed the DREAM study visit at 12 months and who were assigned to active supplements in the primary trial were eligible for the extension study (Figure 1). Participants were informed whether they had been taking ω3 or placebo supplements during the preceding 12 months. Those who agreed to continue taking study supplements for the second year and had a negative urine pregnancy test (women of childbearing potential only) were enrolled after written informed consent was obtained.

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the DREAM primary and extension trials

The original plan was to offer participation in the extension study to all participants in the primary trial assigned to active supplements with the assumption that approximately 50% would enroll. However, recruitment for the primary trial required more time and resources than anticipated. To remain within budget, recruitment for the extension study was ended at the same time as recruitment for the primary trial. This change was approved by the DREAM Data and Safety Monitoring Committee. As of July 31, 2016, 43 (39.4%) of 109 patients completing the Month 12 visit and assigned to active supplements were enrolled in the extension study.

2.2. Treatment

Patients were randomly assigned, in a 1:1 ratio, to receive either active or placebo supplements. The active supplements contained a total dose of 2000 mg of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and 1000 mg docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and the placebo supplements contained a total dose of 5000 mg of refined olive oil. The Access Business Group (Ada, MI) manufactured the supplements (softgel capsules). Participants were instructed to take five capsules per day for 12 months.

2.3. Visit procedures

After the enrollment visit (at month 12 of the primary trial), study visits were conducted at 18 and 24 months with a follow up phone call at months 15 and 21 (Appendix A, Table 1). Visit procedures were conducted in a specific order, in both eyes, and all testing was conducted following a standardized protocol. Standardized supplies were used at all sites. The use of artificial tears or any other topical treatment was not permitted for at least 2 hours before any study visit. Participants were asked to complete questionnaires, Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) and Brief Ocular Discomfort Inventory, about their dry eye symptoms and the impact of DED on their daily lives. A slit lamp evaluation (SLE), evaluation of the meibomian glands and eyelids, and tests to determine signs of dry eye disease were performed at each study visit. The four tests to determine key signs of dry eye disease included: 1) lissamine green conjunctival staining using a modified version of the National Eye Institute (NEI)/industry-recommended guidelines, where each of the temporal and nasal areas were graded on a scale of 0 to 3 under white light of moderate intensity; 2) corneal fluorescein staining using the NEI /industry-recommended guidelines, where each of the temporal, nasal, central, top and bottom areas were graded on a scale of 0 to 3 using the cobalt blue filter of the slit lamp;23 3) tear break up time (TBUT) and 4) Schirmer test with anesthetic.

2.4. Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was a change in dry eye symptoms from month 12 to month 24 as measured by the OSDI score. Secondary outcomes included changes in the above described four clinical signs of DED: lissamine green staining, fluorescein corneal staining, TBUT, and Schirmer test from baseline to follow up.

2.5. Adverse Events

Patients were asked about incidences of systemic and ocular adverse events during each visit at 18 and 24 months and by telephone at 15 and 21 months. Adverse events were coded according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) system. All adverse events and their codes were reviewed by a medical monitor.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Change between 12 and 24 months within treatment groups was assessed with tests for linear trend across months 12, 18, and 24. Comparisons of mean change in continuous measures between treatment groups and associated 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were based on linear regression using a robust variance estimator. Generalized estimating equations were used for ocular measures to accommodate the correlation between eyes of the same person. Comparisons of categorical outcomes were made using chi-square tests; and 95% CI’s for the difference in proportions were calculated using Wilson’s method. The difference between groups in the number of adverse events per person was assessed with a Poisson regression model.

3. RESULTS

A total of 22 participants were assigned to the active supplement group and 21 to the placebo group. The characteristics of the participants, at enrollment into the extension study, were comparable between treatment groups across all characteristics listed in Table 2 (p>0.05 for all comparisons). Participants were predominantly female and white. The mean OSDI score, conjunctival and corneal staining, tear breakup time, Schirmer test, and the use of dry eye treatments were similar in the 2 groups at enrollment into the extension trial. At entry into the primary trial, mean values for these 43 patients were 43.0 for the total OSDI score, 3.1 for conjunctival staining, 4.5 for corneal staining, 3.3 seconds for tear breakup time, and 8.9 mm for Schirmer test. Between entry into the primary trial and 12 months, the mean percent fatty acid level increased by 2.5% for EPA and by 2.0% for DHA.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the active and placebo groups at Month 12

| Characteristic | Active (22 Patients) | Placebo (21 Patients) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean | 58.2 | ±15.0 | 58.4 | ±14.7 |

| Gender - no. (%) | ||||

| Female | 19 | (86.4) | 17 | (81.0) |

| Male | 3 | (13.6) | 4 | (19.0) |

| Race - no. (%) | ||||

| White | 15 | (68.2) | 16 | (76.2) |

| Black | 2 | (9.1) | 2 | (9.5) |

| Other | 5 | (22.7) | 3 | (14.3) |

| Ethnicity (self-reported) - no. (%) | ||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 2 | (9.1) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Other | 20 | (90.9) | 21 | (100) |

| OSDI score, mean | ||||

| Total | 27.9 | ±19.5 | 27.8 | ±19.6 |

| Vision-related function subscale | 24.1 | ±24.1 | 21.9 | ±23.6 |

| Ocular symptoms | 32.2 | ±23.9 | 34.7 | ±22.5 |

| Environmental triggers subscale | 32.8 | ±26.3 | 33.1 | ±24.7 |

| Short Form −36 score, mean | ||||

| Physical health | 47.6 | ±12.8 | 48.3 | ±9.5 |

| Mental health | 51.1 | ±10.4 | 51.4 | ±10.0 |

| Brief Ocular Discomfort Index score, mean | ||||

| Discomfort subscale | 31.7 | ±19.4 | 29.0 | ±16.2 |

| Pain interference subscale | 16.5 | ±21.3 | 14.9 | ±14.1 |

| Use of dry eye treatments, n (%) | ||||

| Artificial tears, drops or gel | 13 | (59.1) | 14 | (66.7) |

| Cyclosporine drops | 7 | (31.8) | 4 | (19.0) |

| Warm lid soaks | 4 | (18.2) | 3 | (14.3) |

| Lid scrubs or baby shampoo | 3 | (13.6) | 1 | (4.8) |

| Any other treatment | 6 | (27.3) | 7 | (33.3) |

| Systemic disease - no. (%)** | ||||

| Sjögren syndrome | 4 | (18.2) | 2 | (9.5) |

| Thyroid disease | 4 | (18.2) | 2 | (9.5) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 3 | (13.6) | 4 | (19.0) |

| None of the above | 14 | (63.6) | 15 | (71.4) |

| Fatty acid in red blood cells, mean†† | ||||

| Eicosapentaenoic, % | 3.0 | ±1.0 | 3.3 | ±1.0 |

| Docosahexaenoic, % | 6.1 | ±0.7 | 6.2 | ±0.7 |

| Oleic, % | 10.6 | ±1.2 | 11.4 | ±1.4 |

| 44 Eyes | 42 Eyes | |||

| Conjunctival staining score, mean | 2.7 | ±1.7 | 2.1 | ±1.7 |

| Corneal staining score, mean | 3.3 | ±2.9 | 3.9 | ±3.3 |

| Tear break-up time, secs, mean | 4.3 | ±4.8 | 3.3 | ±2.0 |

| Schirmer test, mm, mean | 7.1 | ±3.4 | 7.7 | ±5.9 |

Plus-minus values are means ± SD

Ongoing or past history by patient report; may have more than 1 disease

Missing values for 1 in the Active group

Completion of follow-up visits at 18 and 24 months was ≥86% in both treatment groups. The mean values of the % of EPA and DHA in red blood cell membranes decreased more in the placebo group than in the active group (−2.5% vs −0.6% for EPA and −1.9% vs −0.6% for DHA; p<0.001 for both; Table 3). Mean changes in oleic acid, the main constituent of olive oil, were similar between the 2 groups.

Table 3:

Changes in primary and secondary outcome measures from 12 months to 24 months

| Active Patients | Placebo Patients | Between Group Difference* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change from baseline | n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | Mean | (95% CI) | p |

| Ocular Surface Disease Index score | |||||||||

| Total, mean | 19 | 3.1 | ±15.1 | 20 | 3.7 | ±17.8 | −0.6 | (−10.7, 9.5) | 0.91 |

| Vision-related function, mean | 19 | 2.8 | ±18.0 | 20 | 2.5 | ±20.3 | 0.3 | (−11.4, 12.0) | 0.96 |

| Ocular symptoms, mean | 19 | −0.0 | ±18.8 | 20 | 3.1 | ±16.5 | −3.1 | (−14.0, 7.7) | 0.57 |

| Environmental triggers, mean | 17 | 5.4 | ±17.4 | 20 | 5.4 | ±26.7 | −0.0 | (−14.0, 13.9) | 1.00 |

| ≥10 increase, n (%) | 19 | 6 | (32%) | 20 | 5 | (25%) | 7% | (−33%, 21%) | 0.65 |

| Brief Ocular Discomfort Index, mean | |||||||||

| Discomfort | 19 | −5.1 | ±14.3 | 20 | 3.5 | ±19.3 | −8.6 | (−19.0, 1.7) | 0.10 |

| Interference | 19 | −1.7 | ±16.0 | 20 | 2.6 | ±13.3 | −4.3 | (−13.3, 4.7) | 0.35 |

| Short Form-36 score, mean | |||||||||

| Physical health | 19 | −1.6 | ±11.2 | 20 | −3.3 | ±4.9 | 1.8 | (−3.6, 7.1) | 0.52 |

| Mental health | 19 | −4.1 | ±5.0 | 20 | −0.5 | ±7.0 | −3.6 | (−7.3, 0.1) | 0.055 |

| Fatty acid in red blood cells, % mean | |||||||||

| Eicosapentaenoic | 18 | −0.6 | ±0.8 | 19 | −2.5 | ±0.7 | 1.9 | (1.4, 2.4) | <0.001 |

| Docosahexaenoic | 18 | −0.6 | ±0.6 | 19 | −1.9 | ±0.7 | 1.3 | (0.9, 1.7) | <0.001 |

| Oleic | 18 | 0.51 | ±0.69 | 19 | 0.17 | ±1.51 | 0.3 | (−0.4, 1.1) | 0.36 |

| Signs, mean | |||||||||

| Conjunctival staining score | 38 | −0.4 | ±1.0 | 40 | 0.1 | ±1.9 | −0.4 | (−1.2, 0.3) | 0.26 |

| Corneal staining score | 38 | −0.1 | ±1.7 | 40 | 0.2 | ±2.1 | −0.3 | (−1.2, 0.7) | 0.60 |

| Tear break-up time, seconds | 38 | −0.6 | ±4.6 | 40 | 0.2 | ±1.9 | −0.8 | (−2.6, 0.9) | 0.35 |

| Schirmer test, mm | 38 | 2.4 | ±3.8 | 40 | 1.8 | ±5.4 | 0.6 | (−2.0, 3.2) | 0.65 |

| Safety, mean | |||||||||

| Visual acuity, letters | 38 | 0.0 | ±3.8 | 40 | −0.1 | ±3.9 | 0.1 | (−1.6, 1.9) | 0.89 |

| Intraocular pressure, mmHg | 38 | 0.2 | ±2.6 | 40 | −0.3 | ±2.7 | 0.5 | (−1.0, 2.0) | 0.48 |

Differences are the value in the active group minus the value in the placebo group.

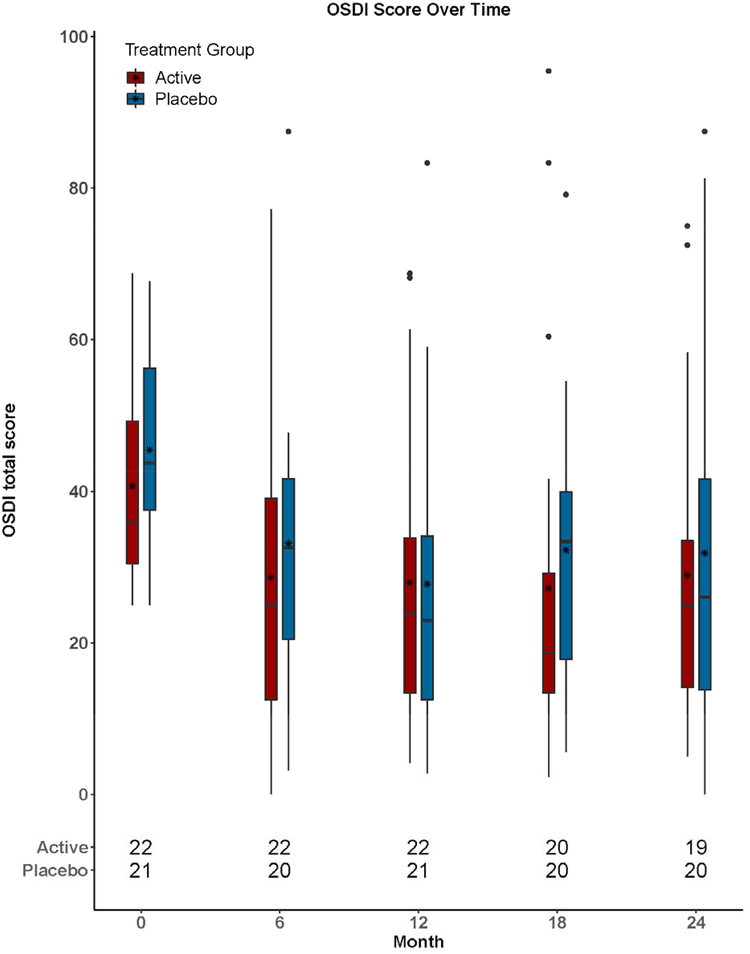

The mean (±SD) change between month 12 and month 24 in total OSDI score was 3.1±15.1 (p=0.52) in the active group and 3.7±17.8 (p=0.28) in the placebo group (Table 3). The difference in mean change between groups was −0.6 (95% confidence interval CI (−10.7, 9.5); p=0.91). (Table 3; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) scores over time. Box and whisker plots: Box upper and lower edges correspond to the 75th and 25th percentiles, respectively. Within the box, the asterisk corresponds to the mean value and the line corresponds to the 50th percentile (median). Ends of whiskers correspond to the lowest score within 1.5 times the interquartile range of the 25th percentile and the highest score within 1.5 times the interquartile range of 75th percentile. Each circle outside of the whiskers corresponds to one score.

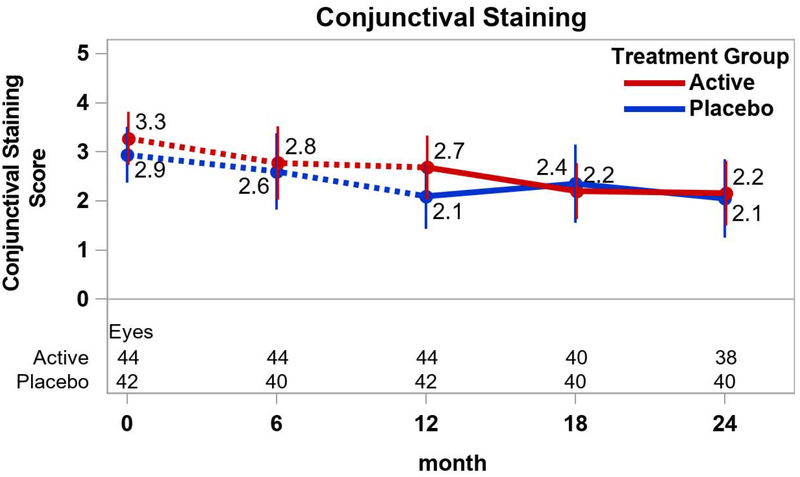

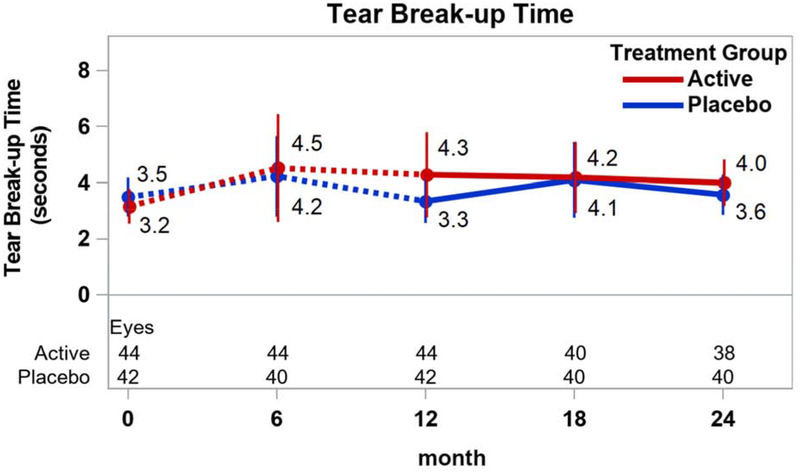

Among the secondary outcome measures of DED signs, most of the changes between 12 and 24 months within the treatment groups were not statistically significantly different from 0 (p≥0.28; Figure 3). However, the mean (±SD) conjunctival staining score decreased in the active group (−0.4±1.0; p=0.04) while the mean (±SD) Schirmer test mm increased in both the active group (2.4±3.8; p=0.004) and the placebo group (1.8±5.4; p=0.03). Mean (95% CI) differences in change between active and placebo groups were −0.4 ((−1.2, 0.3); p=0.26) for the conjunctival staining score and −0.3 ((−1.2, 0.7); p=0.60) for the corneal staining score (Figures 3A and 3B). The mean difference for TBUT was −0.8 secs ((−2.6, 0.9); p=0.35) (Figure 3C) and for Schirmer test was 0.6 mm ((−2.0, 3.2); p=0.65) (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

Signs of dry eye disease over time by treatment group. Mean values and associated 95% confidence intervals for signs of dry eye disease by treatment group, over time. Dotted lines connect values prior to randomization in the extension trial. A. Conjunctival staining; B. Corneal staining; C. Tear break-up time; D. Shirmer test.

One patient in the placebo group experienced a serious adverse event, hospitalization for dyspnea. There were 19 non-serious adverse events among patients in the active group and 11 among patients in the placebo group (p=0.46; Appendix B; Table 4).

4. DISCUSSION

In this randomized trial of withdrawal of ω3 supplementation, we evaluated the effects of discontinuing use of ω3 supplements on the symptoms and signs of DED relative to continuing use. We also evaluated whether there was any added benefit of using ω3 for 2 years in the active ω3 group and whether signs and symptoms of DED returned after stopping ω3 after 1 year in the placebo group.

We found no statistically significant difference in changes in symptoms or signs of DED between patients continuing use of ω3 supplements and patients discontinuing use. The mean OSDI score increased (worsened) by 3 to 4 points in each treatment group; however, these mean changes over time were small and not significantly different from zero. The changes in the extension study were different in magnitude from the changes in these patients in the primary trial when the mean improvement at 12 months was approximately 15 points.

Mean conjunctival staining score decreased slightly (improvement) in the active supplement group and Schirmer test results increased (improved) in both groups. No significant worsening of DED signs and symptoms were seen between 12 and 24 months in the placebo group, suggesting that discontinuing the use of ω3 after 12 months may not have worse outcomes compared to continuing for an additional 12 months.

Strengths of this study include good follow-up and good compliance as judged by the placebo group’s decrease in blood EPA and DHA levels. The mean decreases in EPA and DHA in the group that switched to placebo were similar in magnitude to the large mean increases after the patients initiated active supplements in the primary trial, indicating a high level of compliance in both trials. The small sample size of approximately 20 per group limited the precision of the estimation of the mean differences between treatment groups as reflected in their wide confidence intervals. For the difference between treatment groups in mean change in the OSDI score, the 95% confidence interval was (−10.7, 9.5). This interval includes values that we considered clinically meaningful (greater than a 6-point difference in means) when the primary trial was designed.22

Conduct of a randomized withdrawal trial is not common in ophthalmology, but enables a longitudinal assessment of DED with respect to changes in symptoms and signs in both the placebo and the treatment group. A study duration of 12 months provides information on the sustainability of the treatment effect of ω3 supplementation and facilitates study of long term safety profile of ω3 supplementation.

The results from the DREAM extension study are consistent with the results from the DREAM primary trial. In the primary trial, introduction of ω3 supplementation was associated with a substantial improvement (14 points among all patients) in the mean OSDI score that was similar to the improvement observed in the placebo group. In the extension study, withdrawal of ω3 supplementation was associated with slight worsening (4 points) in the mean OSDI score that was similar to the worsening observed in the ω3 group. Mean changes over time in signs of DED were small and similar between treatment groups in both the primary trial and the extension study. Taken together, the results from the two DREAM clinical trials do not support a beneficial effect of ω3 supplementation on dry eye disease.

Disclosures:

Dr. Asbell reports personal fees from Allergan, Bausch& Lomb, Kao, MC2 Therapeutics, Medscape, Miotech, Novartis, Oculus, Rtech, Santen, Shire, and Valeant; grants from Bausch& Lomb, MC2 Therapeutics, Miotech, Novartis, Rtech, ScientiaCME, and Valeant and non-financial support from Santen, Shire, and Valeant. Dr. Maguire reports personal fees from Genentech/Roche. For the remaining authors, none were declared. The Access Business Group, LLC (Ada, MI) manufactured, packaged and delivered study supplements to the central pharmacy at no cost to the study.

Supported by cooperative agreements U10EY022879 and U10EY022881 from the National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services. Additional support provided by grants from the Office of Dietary Supplements National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services.

Abbreviations

- DED

dry eye disease

- DHA

docosahexaenoic acid

- DREAM

Dry Eye Assessment and Management

- EPA

eicosapentaenoic acid

- NEI

National Eye Institutee

- OSDI

Ocular Surface Disease Index

- TBUT

tear break-up time

APPENDICES

Appendix A.

Table 1.

Extension study schedule of procedures

| Visit (Month) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedure | 15 | 18 | 21 | 24 |

| OSDI & BODI Questionnaires | Y | Y | ||

| Health Economics Questionnaires ( SF-36, WPAI, Healthcare Use) | Y | Y | ||

| Medical History and Events | Y | Y | ||

| Concomitant Medication Query | Y | Y | ||

| Adverse Event Query | Y | Y | ||

| Tear Osmolarity | Y1 | Y1 | ||

| Keratograph Break-Up Time, Tear Meniscus Height, Redness, and Meibomian Gland Evaluation | Y1 | Y1 | ||

| Best Corrected VA (if change in VA ≥ 10 letters, do refraction) | Y | Y | ||

| Contrast Sensitivity | Y | Y | ||

| Tear Collection for Cytokines | Y1 | Y1 | ||

| Slit Lamp Evaluation (SLE) | Y | Y | ||

| Tear Break-Up Time (TBUT)3 | Y | Y | ||

| Corneal Fluorescein Staining3 | Y | Y | ||

| Meibomian Gland Examination3 | Y | Y | ||

| Lissamine green staining3 | Y | Y | ||

| IOP | Y | Y | ||

| Schirmer’s Tear Test (with anesthetic) | Y | Y | ||

| Impression Cytology | Y | Y | ||

| Blood Collection (Mon-Thurs) for fatty acid determination | Y | Y | ||

| Blood Collection (Mon-Thurs) for antibody determination | Y | |||

| Collection of Unused Study Supplements | Y | Y | ||

| Reminder Calls (2 weeks before each visit) | Y | Y | ||

| “Check-In” Telephone Call | Y | Y | Y2 | |

| Letter to Encourage Compliance (sent 1 month after each visit) | Y | |||

LEGEND:

Only at centers with required equipment

Call for final adverse event assessment

Do all 4 procedures OD, then restart for OS

Appendix B.

Table 4:

Adverse events between month 12 and 24 in the extension study by system organ class, preferred term, and treatment group.

| Treatment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active 22 people | Placebo 21 people | ||||

| System Organ Class | Preferred Term | N | Per 100 people | N | Per 100 people |

| Total | 19 | 86.4 | 11 | 52.4 | |

| EAR AND LABYRINTH DISORDERS | VERTIGO | 1 | 4.5 | -- | -- |

| EYE DISORDERS | CONJUNCTIVAL HAEMORRHAGE | 1 | 4.5 | -- | -- |

| CONJUNCTIVAL IRRITATION | -- | -- | 1 | 4.8 | |

| PHOTOPHOBIA | -- | -- | 1 | 4.8 | |

| PHOTOPSIA | 1 | 4.5 | -- | -- | |

| GASTROINTESTINAL DISORDERS | DYSPEPSIA | 1 | 4.5 | -- | -- |

| HEPATOBILIARY DISORDERS | HEPATOMEGALY | 1 | 4.5 | -- | -- |

| INFECTIONS AND INFESTATIONS | BRONCHITIS | 1 | 4.5 | -- | -- |

| GINGIVAL INFECTION | -- | -- | 1 | 4.8 | |

| INFECTION | 1 | 4.5 | -- | -- | |

| LUNG INFECTION | 1 | 4.5 | -- | -- | |

| NASAL ABSCESS | 1 | 4.5 | -- | -- | |

| NASOPHARYNGITIS | 1 | 4.5 | -- | -- | |

| TOOTH INFECTION | 1 | 4.5 | -- | -- | |

| URINARY TRACT INFECTION | 1 | 4.5 | -- | -- | |

| INJURY, POISONING AND PROCEDURAL COMPLICATIONS | ARTHROPOD BITE | 1 | 4.5 | -- | -- |

| EPICONDYLITIS | -- | -- | 1 | 4.8 | |

| FRACTURE | 1 | 4.5 | -- | -- | |

| INVESTIGATIONS | BLOOD CALCIUM INCREASED | 1 | 4.5 | -- | -- |

| MUSCULOSKELETAL AND CONNECTIVE TISSUE DISORDERS | BACK PAIN | 1 | 4.5 | 1 | 4.8 |

| NECK PAIN | -- | -- | 1 | 4.8 | |

| TRIGGER FINGER | 1 | 4.5 | -- | -- | |

| NERVOUS SYSTEM DISORDERS | DIZZINESS | -- | -- | 1 | 4.8 |

| SCIATICA | -- | -- | 1 | 4.8 | |

| RESPIRATORY, THORACIC AND MEDIASTINAL DISORDERS | ALLERGIC COUGH | 1 | 4.5 | -- | -- |

| COUGH | 1 | 4.5 | -- | -- | |

| SURGICAL AND MEDICAL PROCEDURES | CATARACT OPERATION | -- | -- | 2 | 9.5 |

| VASCULAR DISORDERS | BLOOD PRESSURE FLUCTUATION | -- | -- | 1 | 4.8 |

Appendix C. The members of the DRy Eye Assessment and Management (DREAM) Research Group

Credit Roster for the DRy Eye Assessment And Management (DREAM) Study

Certified Roles at Clinical Centers: Clinician (CL); Clinic Coordinator (CC), Data Entry Staff (DE) Principal Investigator (PI), Technician (T).

Milton M. Hom (Azusa, CA): Milton M. Hom, OD FAAO (PI); Melissa Quintana (CC/T); Angela Zermeno (CC/T).

Pendleton Eye Center (Oceanside, CA): Robert Pendleton, MD, PhD. (PI); Debra McCluskey (CC); Diana Amador (T); Ivette Corona (CC/T); Victor Wechter, MD (CL).

University of California School of Optometry, Berkeley (Berkeley, CA): Meng C. Lin, OD PhD FAAO (PI); Carly Childs (CC); Uyen Do (CC); Mariel Lerma (CC); Wing Li, OD (T); Zakia Young (CC); Tiffany Yuen, OD (CC/T).

Clayton Eye Center (Morrow, GA): Harvey Dubiner, MD (PI); Heather Ambrosia, OD (C); Mary Bowser (CC/T); Peter Chen, OD (CL); Helen Dubiner, PharmD, CCRC (CC/T); Cory Fuller (CC/T); Kristen New (DE); Tu Vy Nguyen (C); Ethen Seville (CC/T); Daniel Strait, OD (CL); Christopher Wang (CC/T); Stephen Williams (CC/T); Ron Weber, MD (CL).

University of Kansas (Prairie Village, KS) John Sutphin, MD (PI); Miranda Bishara, MD (CL); Anna Bryan (CC); Asher Ertel (CC/T); Kristie Green (T); Gloria Pantoja, Ashley Small (CC); Casey Williamson (T).

Clinical Eye Research of Boston (Boston, MA): Jack Greiner, MS, OD, DO, PhD (PI); EveMarie DiPronio (CC/T); Michael Lindsay (CC/T); Andrew McPherson (CC/T); Paula Oliver (CC/T); Rina Wu (T).

Mass Eye & Ear Infirmary (Boston, MA): Reza Dana, MD (PI); Tulio Abud (T): Lauren Adams (T); Marissa Arnofsky (T); Jillian Candlish, COA (T); Pranita Chilakamarri (DE); Joseph Ciolino, MD (CL); Naomi Crandall (T); Antonio Di Zazzo (T); Merle Fernandes (T); Mansab Jafri (T); Britta Johnson (T); Ahmed Kheirkhah (T); Sally Kiebdaj (CC/T); Andrew Mullins (CC/T); Milka Nova (T); Vannarut Satitpitakul (T); Chunyi Shao (T); Kunal Suri (T); Vijeeta Tadla (CC); Saboo Ujwala (T); Jia Yin MD, PhD (T); Man Yu (T).

Kellogg Eye Center, University of Michigan (Ann Arbor, MI): Roni Shtein, MD (PI); Christopher Hood, MD (CL); Munira Hussain, MS, COA, CCRP (CC/T); Erin Manno, COT (T); Laura Rozek, COT (T/DE).

Minnesota Eye Consultants (Bloomington, MN): David R. Hardten, MD FACS (PI); Kimberly Baker (T); Alex Belsaas (T); Erich Berg (CC/T); Alyson Blakstad, OD (CL); Ken DauSchmidt (T); Lindsey Fallenstein (CC/T); Ahmad M. Fahmy OD (CL); Mona M. Fahmy OD FAAO (CL); Ginny Georges (T); Deanna E. Harter (CL); Scott G. Hauswirth, OD (CL); Madalyn Johnson (T); Ella Meshalkin (T); Rylee Pelzer (CC/T); Joshua Tisdale (CC/T); JulieAnn C. Wick (CL).

Tauber Eye Center (Kansas City, MO): Joseph Tauber, MD, PHD (PI); Megan Hefter (CC/T).

Silverstein Eye Centers (Kansas City, MO): Steven Silverstein, MD (PI); Cindy Bentley (CC/T); Eddie Dominguez (CC/T); Kelsey Kleinsasser, OD (CL).

Icahn School of Medicine at Mt. Sinai, (New York, NY): Penny Asbell, MD, FACS, MBA (PI); Brendan Barry (CC/T); Eric Kuklinski (CC/T); Afsana Amir (CC/T); Neil Chen (CC/T); Marko Oydanich (CC/T); Viola Spahiu (CC/T); An Vo, MD (T); Matthew Weinstein, DO (T).

University of Rochester Flaum Eye Institute (Rochester, NY): Tara Vaz, OD (PI); Holly Hindman, MD (PI); Rachel Aleese (CC/T); Andrea Czubinski (CC/T); Gary Gagarinas, COMT CCRA (CC/T); Peter McDowell (CC); George O’Gara (DE); Kari Steinmetz (CC/T).

University of Pennsylvania Scheie Eye Institute (Philadelphia, PA): Vatinee Bunya, MD (PI); Michael Bezzerides (CC/T); Dominique Caggiano (CC/T); Sheri Drossner (T); Joan Dupont (CC); Marybeth Keiser (CC/T); Mina Massaro, MD (CL); Stephen Orlin, MD (CL); Ryan O’Sullivan (CC/T).

Southern College of Optometry (Memphis, TN): Michael Christensen, OD PhD (PI); Havilah Adkins (CC); Randy Brafford (CC/T); Cheryl Ervin (CL); Rachel Grant OD (CL); Christina Newman (CL).

Shettle Eye Research (Largo, FL): Lee Shettle, DO (PI); Debbie Shettle (CC).

Stephen Cohen, OD, PC (Scottsdale, AZ): Stephen Cohen, OD (PI); Diane Rodman (CC/T).

Case Western Reserve University (Cleveland, OH): Loretta Szczotka-Flynn, OD PhD (PI); Tracy Caster (T); Pankaj Gupta MD MS (CL); Sangeetha Raghupathy (CC/T); Rony Sayegh, MD (CL).

Mayo Clinic Arizona (Scottsdale, AZ): Joanne Shen, MD (PI); Nora Drutz, CCRC (CC); Lauren Joyner, COA (T); Mary Mathis, COA (T); Michaele Menghini, CCRP (CC); Charlene Robinson, CCRP (CC).

Wolston & Goldberg Eye Associates (Torrance, CA): Damien Goldberg, MD (PI); Lydia Jenkins (T); Brittney Rodriguez (CC/T); Jennifer Picone Jones (CC/T); Nicole Thompson (T), Barry Wolstan, MD (CL).

Northeast Ohio Eye Surgeons (Stow, OH): Marc Jones, MD (PI); April Lemaster (CC/T); Julie Ransom-Chaney (T); William Rudy, OD (CL).

Tufts Medical Center (Boston, MA): Pedram Hamrah, MD (PI); Mildred Commodore (CC); Christian Iyore (T); Lioubov Lazarev (T): Leah Mullen (T); Nicholas Pondelis (T); Carly Satsuma (CC).

University of Illinois at Chicago (Chicago, IL): Sandeep Jain, MD (PI); Peter Cowen (CC/T); Joelle Hallak (CC);Christine Mun (CC/T); Roxana Toh (CC).

The Eye Centers of Racine & Kenosha (Racine, WI): Inder Singh, MD (PI); Pamela Lightfield (CC/T); Eunice Lowery (T); Sarita Ornelas (T); R. Krishna Sanka, MD (CL); Beth Saunders (T).

Mulqueeny Eye Centers (St. Louis, MO): Sean P. Mulqueeny, OD (PI); Maggie Pohlmeier (CC/T).

Oculus Research at Garner Eyecare Center (Raleigh, NC): Carol Aune, OD (PI); Hoda Gabriel (CC); Kim Major Walker, RN MS (CC/T); Jennifer Newsome (CC/T).

Resource Centers

Chairman’s Office (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY): Penny Asbell, MD, FACS, MBA (Study Chair); Brendan Barry (Clinical Research Coordinator); Eric Kuklinski (Clinical Research Coordinator); Shir Levanon (Clinical Research Coordinator); Michael Farkouh, MD FRCPC, FACC, FAHA (Medical Safety Monitor); Seunghee Kim-Schulze, PhD (Consultant); Robert Chapkin, PhD, MSc. (Consultant); Giampaolo Greco, PhD (Consultant); Artemis Simopoulos, MD (Consultant); Ines Lashley (Administrative Assistant); Peter Dentone, MD (Clinical Research Coordinator); Neha Gadaria-Rathod, MD (Clinical Research Coordinator); Morgan Massingale, MS (Clinical Research Coordinator); Nataliya Antonova (Clinical Research Coordinator).

Coordinating Center (University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA): Maureen G. Maguire, PhD (PI); Mary Brightwell-Arnold, SCP (Systems Analyst) John Farrar, MD PhD (Consultant); Sandra Harkins (Staff Assistant); Jiayan Huang, MS (Biostatistician); Kathy McWilliams, CCRP (Protocol Monitor); Ellen Peskin, MA, CCRP (Director); Maxwell Pistilli, MS, MEd (Biostatistician); Susan Ryan (Financial Administrator); Hilary Smolen (Research Fellow); Claressa Whearry (Administrative Coordinator); Gui-Shuang Ying, PhD (Senior Biostatistician) Yinxi Yu (Biostatistician).

Biomarker Laboratory (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY): Yi Wei, PhD, DVM (co-Director, Biomarker Laboratory); Neeta Roy, PhD (co-Director, Biomarker Laboratory); Seth Epstein, MD (Former co-Director; Biomarker Laboratory); Penny A. Asbell, MD, FACS, MBA (Director and Study Chair).

Investigational Drug Service (University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA): Kenneth Rockwell, Jr., PharmD MS (Director).

Peroxisomal Diseases Laboratory at the Kennedy Krieger Institute, Johns Hopkins University Baltimore MD: Ann Moser (Co-Director/Consultant); Richard O. Jones, PhD (Co-Director/Consultant)

Meibomian Gland Reading Center (University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA): Ebenezer Daniel, MBBS, MPH, PhD, (PI); E. Revell Martin (Image Grader); Candace Parker Ostroff, (Image Grader); Eli Smith (Image Grader); Pooja Axay Kadakia (Student Researcher).

National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services: Maryann Redford, DDS, MPH (Program Officer).

Office of Dietary Supplements/National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services

Committees

Executive Committee (Members from all terms of appointment): Penny Asbell, MD FACS, MBA (Chair); Brendan Barry, MS; Munira Hussain, MS, COA, CCRP; Jack Greiner, MS, OD, DO, PhD; Milton Hom, OD, FAAO; Holly Hindman, MD, MPH; Eric Kuklinski, BA; Meng C. Lin OD, PhD. FAAO; Maureen G. Maguire, PhD; Kathy McWilliams, CCRP; Ellen Peskin, MA, CCRP; Maryann Redford, DDS, MPH; Roni Shtein, MD, MS; Steven Silverstein, MD; John Sutphin, MD.

Operations Committee: Penny Asbell, MD FACS, MBA (Chair); Brendan Barry, MS; Eric Kuklinski, BA; Maureen G. Maguire, PhD; Kathleen McWilliams, CCRP, Ellen Peskin, MA, CCRP; Maryann Redford, DDS, MPH.

Clinic Monitoring Committee: Ellen Peskin, MA, CCRP (Chair); Mary Brightwell-Arnold, SCP, Maureen G. Maguire, PhD; Kathleen McWilliams, CCRP.

Data and Safety Monitoring Committee: Stephen Wisniewski, PhD (Chair); Tom Brenna, PhD; William G. Christen Jr, SCD, OD, PhD; Jin-Feng Huang, PhD; Cynthia S. McCarthy, DHCE, MA; Susan T. Mayne, PhD; Mari Palta, PhD; Oliver D. Schein, MD, MPH, MBA.

Industry Contributors of Products and Services

Access Business Group, LLC (Ada, MI) Jennifer Chuang, PhD. CCRP; Maydee Marchan, M.Ch.E; Tian Hao, PhD; Christine Heisler; Charles Hu, PhD; Clint Throop, Vikas Moolchandani, PhD.

Compounded Solutions in Pharmacy (Monroe, CT)

Leiter’s (San Jose, CA)

Immco Diagnostics Inc. (Buffalo NY

OCULUS Inc. (Arlington, WA)

RPS Diagnostics, Inc. (Sarasota, FL)

TearLab Corporation (San Diego, CA)

TearScience Inc. (Morrisville, NC)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

ClinicalTrials.gov number .

REFERENCES

- 1.Pflugfelder SC, Geerling G, Kinoshita S, Lemp MA, McCulley J, Nelson D, et al. Management and therapy of dry eye disease: report of the management and therapy subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007). Ocular Surf 2007;5:163–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belmonte C, Nichols JJ, Cox SM, Brock JA, Begley CG, Bereiter DA, et al. TFOS DEWS II pain and sensation report. Ocul Surf 2017;15:404–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Craig JP, Nichols KK, Akpek EK, Caffery B, Dua HS, Joo CK, et al. TFOS DEWS II Definition and Classification Report. Ocul Surf 2017;15:276–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stapleton F, Alves M, Bunya VY, Jalbert I, Lekhanont K, Malet F, et al. TFOS DEWS II Epidemiology Report. Ocul Surf 2017;15:334–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wei Y, Asbell PA. The core mechanism of dry eye disease is inflammation. Eye Contact Lens 2014;40:248–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gayton JL. Etiology, prevalence, and treatment of dry eye disease. Clin Ophthalmol 2009;3:405–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirsch JD, Morello C, Singh R, Robbins SL. Pharmacoeconomics of new medications for common chronic ophthalmic diseases. Surv Ophthalmol 2007;52:618–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin PY, Tsai SY, Cheng CY, Liu JH, Chou P, Hsu WM. Prevalence of dry eye among an elderly Chinese population in Taiwan: the Shihpai Eye Study. Ophthalmology 2003;110:1096–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moss SE, Klein R, Klein BE. Incidence of dry eye in an older population. Arch Ophthalmol 2004;122:369–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schaumberg DA, Sullivan DA, Buring JE, Dana MR. Prevalence of dry eye syndrome among US women. Am J Ophthalmol 2003;136:318–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farrand KF, Fridman M, Stillman IO, Schaumberg DA. Prevalence of diagnosed dry eye disease in the United States among adults aged 18 years and older. Am J Ophthalmol 2017;182:90–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedman NJ. Impact of dry eye disease and treatment on quality of life. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2010;21:310–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu J, Asche CV, Fairchild CJ. The economic burden of dry eye disease in the United States: a decision tree analysis. Cornea 2011;30:379–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bron AJ, de Paiva CS, Chauhan SK, Bonini S, Gabison EE, Jain S, et al. TFOS DEWS II pathophysiology report. Ocul Surf 2017;15:438–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhargava R, Kumar P, Kumar M, Mehra N, Mishra A. A randomized controlled trial of omega-3 fatty acids in dry eye syndrome. Int J Ophthalmol 2013;6:811–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deinema LA, Vingrys AJ, Wong CY, Jackson DC, Chinnery HR, Downie LE. A randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled clinical trial of two forms of omega-3 supplements for treating dry eye disease. Ophthalmology. 2017;124:43–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kangari H, Eftekhari MH, Sardari S, Hashemi H, Salamzadeh J, Ghassemi-Broumand M, et al. Short-term consumption of oral omega-3 and dry eye syndrome. Ophthalmology 2013;120:2191–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miljanovic B, Trivedi KA, Dana MR, Gilbard JP, Buring JE, Schaumberg DA. Relation between dietary n-3 and n-6 fatty acids and clinically diagnosed dry eye syndrome in women. Am J Clin Nutr 2005;82:887–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pinazo-Duran MD, Galbis-Estrada C, Pons-Vazquez S, Cantu-Dibildox J, Marco-Ramirez C, Benitiz-del-Castillo J. Effects of a nutraceutical formulation based on the combination of antioxidants and omega-3 essential fatty acids in the expression of inflammation and immune response mediators in tears from patients with dry eye disorders. Clin Interv Aging 2013;8:139–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wojtowicz JC, Butovich I, Uchiyama E, Aronowicz J, Agee S, McCulley JP. Pilot, prospective, randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled clinical trial of an omega-3 supplement for dry eye. Cornea 2011;30:308–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asbell PA, Maguire MG, Pistilli M, Ying GS, Szczotka-Flynn LB, Hardten DR, et al. Dry Eye Assessment and Management Study Research Group. n-3 fatty acid supplementation for treatment of dry eye disease. N Engl J Med 2018;378:1681–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asbell PA, Maguire MG, Peskin E, Bunya VY, Kuklinski EJ. The Dry Eye Assessment and Management (DREAM©) Study: Study design and baseline characteristics. Contemp Clin Trials 2018;71:70–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lemp MA. Report of the National Eye Institute/Industry workshop on clinical trials in dry eyes. CLAO J 1995;21:221–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Regression analysis for correlated data. Annu Rev Pub Health 1993; 14:43–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newcombe RG. Interval estimation for the difference between independent proportions: comparison of eleven methods. Stat Med 1998; 17:873–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]