Abstract

Considering the poor prognosis of most advanced cancers, prevention of invasion and metastasis is essential for disease control. Ras homologous (Rho) guanine exchange factors (GEFs) and their signaling cascade could be potential therapeutic targets in advanced cancers. We conducted in silico analyses of The Cancer Genome Atlas expression data to identify candidate Rho-GEF genes showing aberrant expression in advanced gastric cancer and found FERM, Rho/ArhGEF, and pleckstrin domain protein 1 (FARP1) expression is related to poor prognosis. Analyses in 91 clinical advanced gastric cancers of the relationship of prognosis and pathological factors with immunohistochemical expression of FARP1 indicated that high expression of FARP1 is significantly associated with lymphatic invasion, lymph metastasis, and poor prognosis of the patients (P = 0.025). In gastric cancer cells, FARP1 knockdown decreased cell motility, whereas FARP1 overexpression promoted cell motility and filopodium formation via CDC42 activation. FARP1 interacted with integrin β5, and a potent integrin αvβ5 inhibitor (SB273005) prevented cell motility in only high FARP1-expressing gastric cancer cells. These results suggest that the integrin αvβ5-FARP1-CDC42 axis plays a crucial role in gastric cancer cell migration and invasion. Thus, regulatory cascade upstream of Rho can be a specific and promising target of advanced cancer treatment.

Subject terms: Gastric cancer, Targeted therapies, Target identification, Extracellular matrix, RHO signalling

Introduction

Molecular targeted therapies have successfully improved prognoses of several patients with cancer; however, prognoses of most patients carrying advanced cancers are still poor. In fact, trastuzumab (a HER2-neutralizing antibody) and ramucirumab (an anti-VEGFR-2 antibody) have been introduced with or without combined treatment of cytotoxic agents that have improved the survival of patients with gastric cancer; however, the overall survival of patients with advanced gastric cancer remains discouraging1. Gastric cancer remains the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide2,3. The only curative treatment for advanced gastric cancer is surgery. The prognosis of patients with metastatic gastric cancer is poor, with median survival ranging from 4 to 12 months, depending on the medical treatments applied4,5. Therefore, better management of advanced cancers, including gastric cancer, particularly through the use of new targeted therapeutic agents, is urgently required.

Recent studies have revealed the aberrant expression of or genetic alterations in Ras homologous (Rho) guanine exchange factors (GEFs) in several human cancers6–10, which is consistent with their reported crucial role in the deregulated signaling of human cancer initiation and progression11. Rho family proteins comprises 20 members in humans as a major branch of the Ras superfamily of small GTPases that specifically regulate actin organization, cell motility, polarity, growth, survival, and gene transcription1,12. Rho family proteins act as binary switches that are highly regulated by Rho GEFs that induce the replacement of bound GDP by GTP. In human cancers, Rho GTPases are crucial for cancer cell migration, invasion, and metastasis13. Accordingly, mutations of Ras genes have been identified in over 30% of human cancers14; conversely, very few mutations in Rho GTPases have been detected.

FERM, Rho/ArhGEF, and pleckstrin domain protein 1 (FARP1) constitutes a Rho GEF protein that is composed of an ezrin-like domain, which is found in cytoskeleton-associated proteins of the band 4.1 superfamily, a Dbl homology (DH) domain, and two pleckstrin homology (PH) domains, which are conserved in Rho GEF family members15. Recently, it was reported that in dendrites, FARP1 binds SynCAM1 and integrates excitatory synapse development via Rac1 activation16, whereas in endothelial cells, it regulates the endothelial barrier via a signaling unit also comprising PAK7, a CDC42 effector, and the CDC42-GTPase-activating protein SYDE117. However, the impact of FARP1 expression in cancer remains poorly understood.

In the present study, we examined correlation between FARP1 expression and the prognosis of patients with gastric cancer, and explored the potential role of the integrin αvβ5-FARP1-CDC42 axis in promoting cancer cell migration and invasion.

Results

Identification of candidate Rho GEF genes in gastric cancer

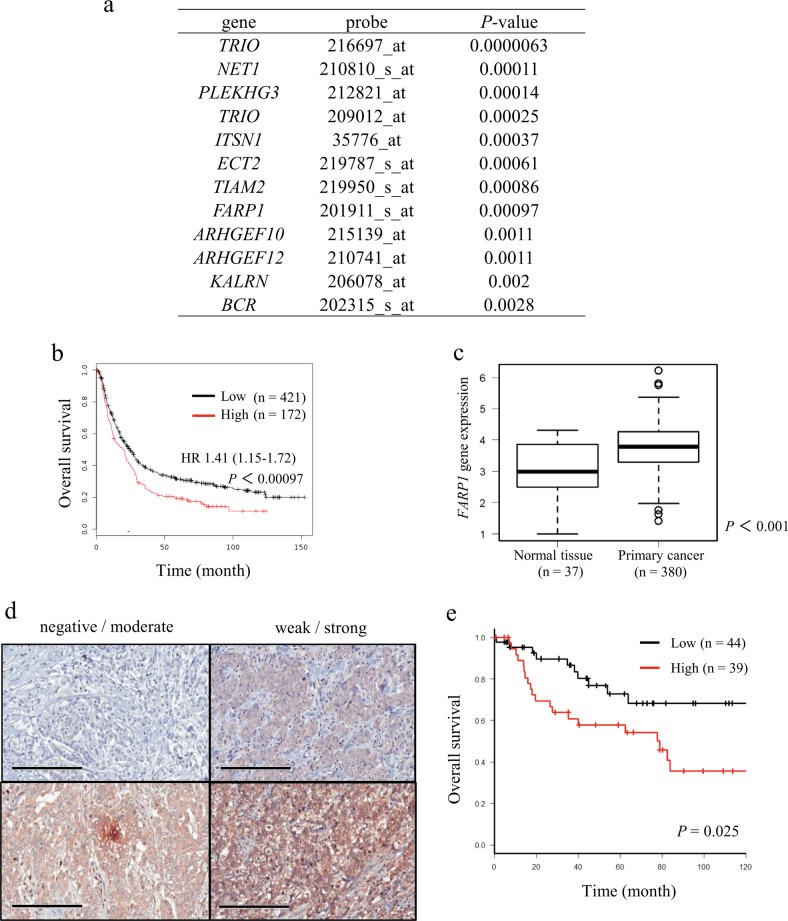

Kaplan–Meier analysis showed that high expression of 11 Rho GEF genes was significantly correlated with worse prognosis of patients with gastric cancer in GEO datasets (Fig. 1a). The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data analysis indicated that the gene expression of TRIO, NET1, ECT2, TIAM2, FARP1, ARHGEF12 and BCR in primary cancer was significantly higher than those in normal tissues (Supplementary Fig. S1). Several investigators have previously reported the relevance of TRIO, NET1, ECT2 and TIAM2 in cancer metastasis and clinical prognosis9,18–33 (Supplementary Table 1). We further focused on FARP1, which has never been reported to have clinical significance in cancers. The prognostic value of FARP1 expression in the Kaplan–Meier plotter and TCGA data analysis of FARP1 expression in normal tissues and primary cancer are shown in Fig. 1b (HR 1.41 [1.15–1.72], P = 0.00097) and Fig.1c (P < 0.001), respectively.

Fig. 1. High expression of FARP1 is associated with poor prognosis in gastric cancer.

a List of Rho GEF genes significantly correlated with poor prognosis of patients with gastric cancer. b Relationship between FARP1 expression and overall survival of patients with gastric cancer as assessed using the Kaplan–Meier plotter. c Gene expression of FARP1 in solid normal tissue and primary gastric cancer. Magnification, ×200; scale bar, 200 μm. d Intensity of anti-FARP1 staining in the cytoplasm of gastric cancer cells. e Overall survival of patients with gastric cancer within high and low FARP1 expression grouped according to immunohistochemistry assessment. Survival rates were calculated by the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences in survival were estimated by the log-rank test.

Correlation between FARP1 expression and clinicopathological findings in patients with advanced gastric cancer

To investigate whether the expression of FARP1 plays a role in gastric cancer development, we performed immunohistochemical analysis of 91 advanced gastric cancer samples (Fig. 1d). The accuracy of anti-FARP1 antibody was confirmed by immunohistochemical and immunofluorescence staining (Supplementary Fig. S2). The expression of FARP1 protein was associated with lymphatic metastasis (N) (P = 0.012), lymphatic invasion (ly) (P = 0.025) and recurrence rate (P = 0.002) but not with age, sex, pathological type, depth of invasion (T), pathological stage (pStage), venous invasion (v), or recurrence pattern (Table 1). The overall survival of patients in the high FARP1 expression group was significantly shorter than that in the low FARP1 expression group (P = 0.025) (Fig. 1e) in line with the in silico analysis.

Table 1.

Correlation between FARP1 expression and clinicopathological factors in gastric cancer patients.

| FARP1 expression, n (%) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | ||

| Patient, n = 91 | 47 (51.6) | 44 (48.4) | |

| Age, n = 91 | |||

| ≤65 | 20 (55.6) | 16 (44.4) | 0.697 |

| <65 | 27 (49.1) | 28 (50.9) | |

| Gender, n = 91 | |||

| Men | 31 (50.0) | 31 (50.0) | 0.814 |

| Women | 16 (55.2) | 13 (44.8) | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy, n = 67 | |||

| Yes | 20 (51.3) | 19 (48.7) | 0.269 |

| No | 19 (67.9) | 9 (32.1) | |

| Pathological type, n = 91 | |||

| Differentiated | 12 (42.9) | 16 (57.1) | 0.373 |

| Undifferentiated | 35 (55.6) | 28 (44.4) | |

| T (pathological), n = 91 | |||

| pT2 | 9 (60.0) | 6 (40.0) | 0.654 |

| pT3 | 23 (52.3) | 21 (47.7) | |

| pT4a | 15 (48.4) | 16 (51.6) | |

| pT4b | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | |

| N (pathological), n = 91 | |||

| pN1 | 19 (82.6) | 4 (17.4) | 0.012 |

| pN2 | 7 (43.8) | 9 (56.2) | |

| pN3 | 8 (36.4) | 14 (63.6) | |

| pN4a | 8 (38.1) | 13 (61.9) | |

| pN4b | 5 (55.6) | 4 (44.4) | |

| Stage, n = 91 | |||

| IB | 8 (80.0) | 2 (20.0) | 0.352 |

| IIA | 8 (61.5) | 5 (38.5) | |

| IIB | 7 (58.3) | 5 (41.7) | |

| IIIA | 6 (37.5) | 10 (62.5) | |

| IIIB | 10 (50.0) | 10 (50.0) | |

| IIIC | 5 (35.7) | 9 (64.3) | |

| IV | 3 (50.0) | 3 (50.0) | |

| Lymphatic invasion, n = 91 | |||

| ly1 | 14 (77.8) | 4 (22.2) | 0.025 |

| ly2 | 16 (57.1) | 12 (42.9) | |

| ly3 | 10 (43.5) | 13 (56.5) | |

| ly4 | 7 (31.8) | 15 (68.2) | |

| Venous invasion, n = 91 | |||

| v1 | 7 (41.2) | 10 (58.8) | 0.191 |

| v2 | 23 (65.7) | 12 (34.3) | |

| v3 | 9 (47.4) | 10 (52.6) | |

| v4 | 8 (40.0) | 13 (65.0) | |

| Recurrence, n = 82 | |||

| Yes | 5 (22.7) | 17 (77.3) | 0.002 |

| No | 39 (65.0) | 21 (35.0) | |

| Recurrence pattern, n = 20 | |||

| Local | 1 (33.3) | 2 (67.7) | 0.886 |

| Lymphogenus | 1 (25.0) | 3 (75.0) | |

| Hematogenous | 1 (25.0) | 3 (75.0) | |

| Peritoneal dissemination | 0 (0.0) | 3 (100.0) | |

| Multiple | 1 (20.0) | 4 (80.0) | |

| Follow-up lost, n = 7 | 3 (42.9) | 4 (57.1) | 1 |

Statistical analyses of two groups were performed using χ2 test.

FARP1 expression promotes gastric cancer cell motility and promotes filopodium formation by activating CC42

Supplementary Fig. S3 shows the mRNA and protein FARP1 expression levels of the four human gastric cancer cell lines. Since MKN45 and MKN74 cells exhibited relatively higher endogenous FARP1 expression, FARP1 RNA interference was performed in only these cells. The knockdown efficiency of siRNAs was confirmed by qPCR and western blot analysis (Supplementary Fig. S4a, b). Alternatively, MKN7 and GSU cells were infected with FLAG- enhanced green fluorescence protein (EGFP)- or FLAG-FARP1-expressing lentivirus, and the overexpression efficiencies of infection were confirmed by qPCR and western blot analysis (Supplementary Fig. S4c, d).

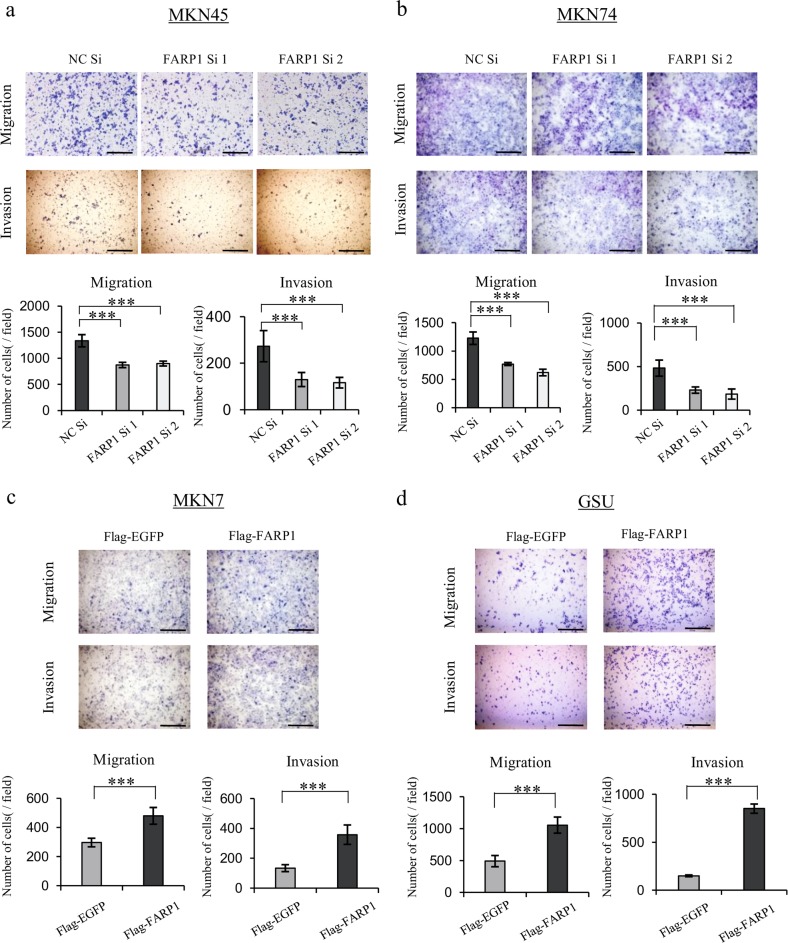

The proliferation of FARP1-knockdown and FARP1-overexpressing cells was comparable to that of the control cells (Supplementary Fig. S5). FARP1 knockdown significantly decreased the numbers of migratory and invasive cells in both the MKN45 and MKN74 cell lines (Fig. 2a, b). Consistent with these findings, FARP1 overexpression significantly increased the numbers of migratory and invasive cells in the MKN7 and GSU cell lines (Fig. 2c, d).

Fig. 2. Effect of FARP1 expression on cell migration and invasion in gastric cancer cell lines.

a–d Transwell migration and invasion assay in FARP1-knockdown (MKN45, MKN74) and FARP1-overexpressing (GSU, MKN7) cell lines. Magnification, ×100; scale bar, 500 μm. In (a–d), the graphs indicate the number of migratory and invasive cells. The values represent the means ± SD from six independent microscopic fields. ***P < 0.001 (Student’s t test).

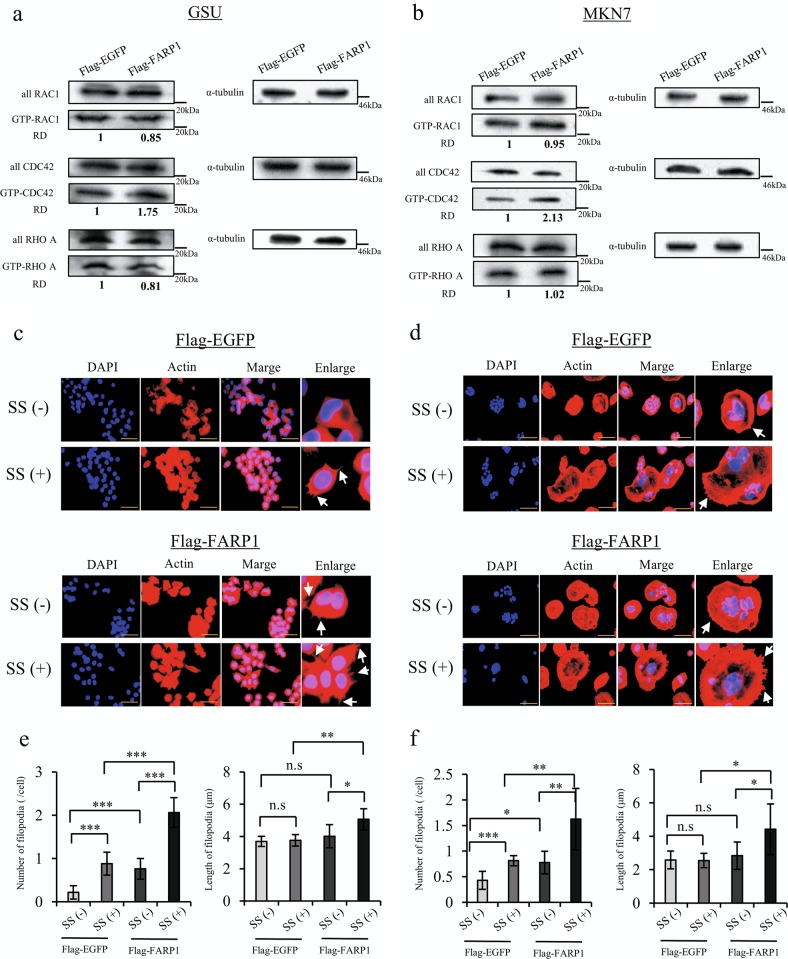

Considering that Rho GEFs can directly activate Rho family proteins, we determined the amounts of activated RAC1, CDC42, and RHOA using a Rho small GTPase pulldown assay in FARP1-overexpressing cells upon serum stimulation. The amount of GTP-CDC42 increased in FARP1-overexpressing cells; however, the amount of GTP-RAC1 and GTP-RHOA in FARP1-overexpressing cells did not change (Fig. 3a, b). Conversely, the amount of GTP-CDC42 in FARP1-overexpressing GSU cells showed no distinct change compared with that of EGFP-overexpressing cells with no serum stimulation (Supplementary Fig. S6). Several investigators have reported that certain extracellular stimuli first activate Rho GEFs in a distinct manner12,34,35. Thus, these results may suggest that the FARP1-CDC42 cascade might be activated by particular extracellular signals.

Fig. 3. FARP1 activates CDC42 and promotes filopodium formation in gastric cancer cell lines.

a, b Active Rac1/CDC42/RhoA pulldown assay with serum stimulation in GSU and MKN7 cells infected with the FLAG-EGFP- or FLAG-FARP1–expressing lentivirus. c, d Immunofluorescence staining for actin (red) and DAPI (blue) with or without serum stimulation in GSU and MKN7 cells infected with the FLAG-EGFP- or FLAG-FARP1-expressing lentivirus. Magnification, ×400; scale bar, 50 μm in each of the three photos; magnification, ×200; scale bar, 100 μm in enlarge. SS serum stimulation. White arrow, filopodium formation. e, f Number and length of filopodia in the FLAG-EGFP- or and FLAG-FARP1-expressing cells. Values represent the means ± SD from six independent fields. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; n.s. not significant (Student’s t test); RD relative density.

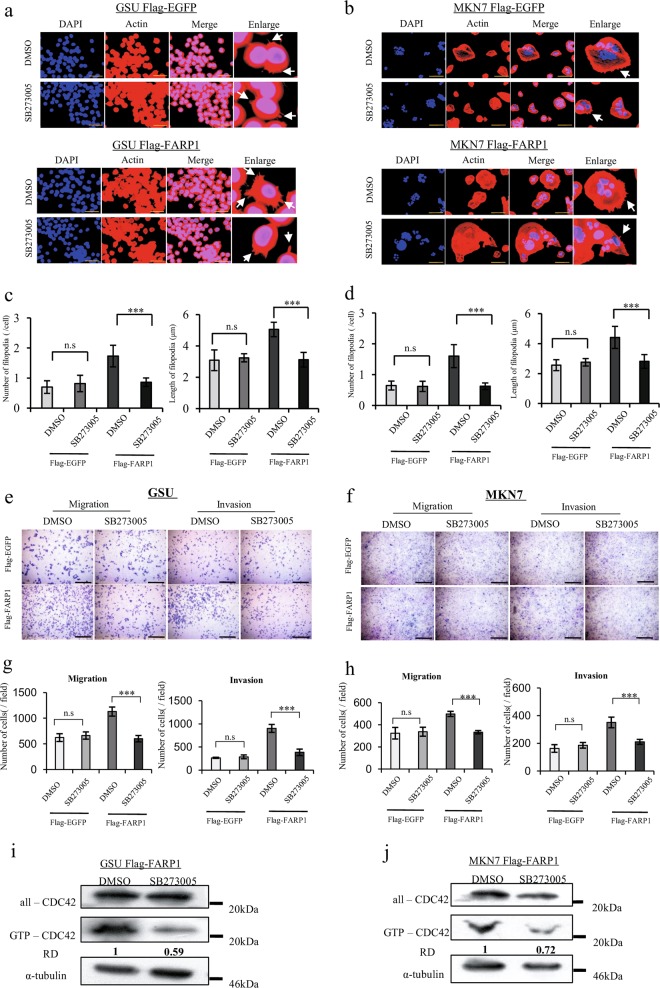

In addition, as Rho family GTPases have important roles in the regulation of the cytoskeleton, we evaluated the effect of FARP1 expression on the cytoskeleton in GSU and MKN7 cell lines by detecting actin expression. Serum stimulation promoted filopodium formation in both EGFP- and FARP1-overexpressing cells, with FARP1-overexpressing cells exhibiting particularly greater filopodium formation than that of EGFP-overexpressing cells for both cell lines (Fig. 3c–f).

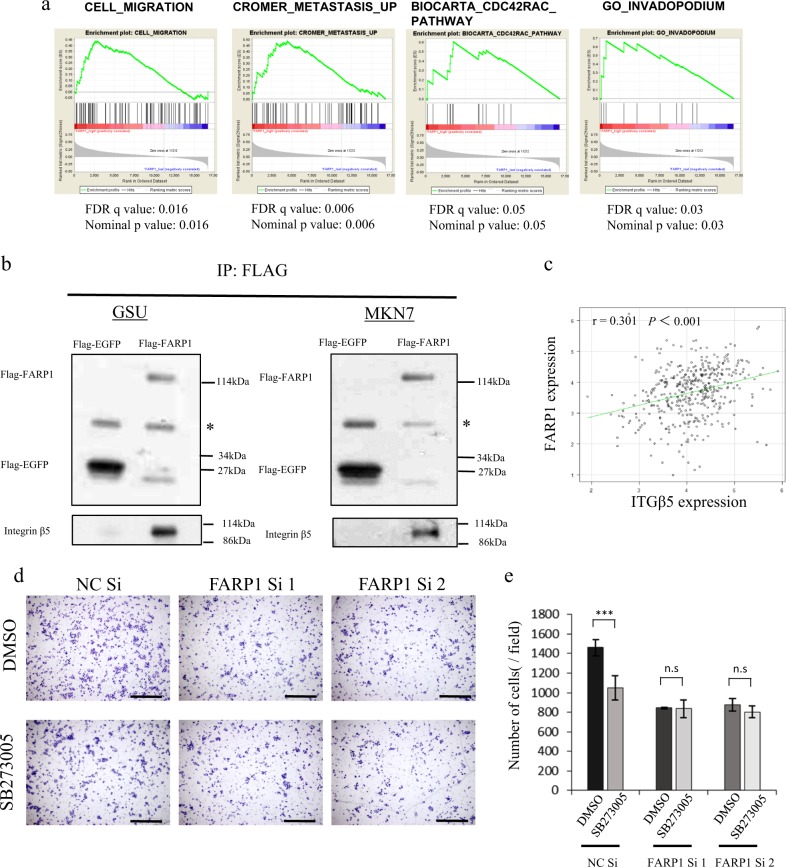

The gene expression and gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) results of FARP1 expression from TCGA data indicated that FARP1 expression enriched the gene sets of CDC42 activation, migration, invadopodia, and metastasis (Fig. 4a), consistent with the in vitro results of FARP1 function.

Fig. 4. Interaction of FARP1 with integrin αvβ5 and expression of integrin β5 in gastric cancer.

a Gene sets identified as being related to FARP1 expression using GSEA. b Lysates from the FLAG-EGFP- or FLAG-FARP1-expressing GSU and MKN7 cells immunoprecipitated with the anti-FLAG antibody. Serum stimulation was applied before the cells were lysed. FLAG and integrin β5 were detected by western blotting. * indicate immunoglobulin heavy chain. c Correlation between FARP1 mRNA expression and integrin β5 mRNA expression in primary gastric cancer based on TCGA data. d Transwell migration assay in MKN74 cells transfected with NC Si, FARP1 Si1 or FARP1 Si2. e Numbers of migratory MKN74 cells transfected with NC Si, FARP1 Si1 or FARP1 Si2. In (d), 0.03% DMSO or 0.3 nM SB273005 diluted in 0.03% DMSO was applied when cells were inoculated onto the chamber. Magnification, ×100. Scale bar, 500 μm. e Values represent the means ± SD from six independent fields. ***P < 0.001; n.s. not significant (Student’s t test).

FARP1 interacts with integrin αvβ5, whereas inhibition of the integrin αvβ5 receptor decreases FARP1-induced filopodium formation and cell motility

Recently, several investigators reported the relationship of Rho GEFs and integrin36,37 and the direct interaction between FERM domain-containing proteins and integrin β5 was reported38,39. As FARP1 contains a FERM domain, we hypothesized that an interaction between FARP1 and integrin β5 might underlie the molecular mechanism of extracellular FARP1 activation. Immunoprecipitation with an anti-FLAG antibody followed by detection with an anti-integrin β5 antibody in FLAG-EGFP- or FLAG-FARP1-expressing GSU and MKN7 cells lysates indicated an interaction between FARP1 and integrin β5 (Fig. 4b). High integrin β5 mRNA levels were associated with worse prognosis using the Kaplan–Meier plotter (HR 1.37 [1.11–1.68], P = 0.0029) (Supplementary Fig. S7a), and the gene expression level of integrin β5 in primary gastric cancer was significantly higher than that in normal tissues based on TCGA data analysis (P < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. S7b). Furthermore, a positive correlation was observed between FARP1 mRNA expression and integrin β5 mRNA expression (P < 0.001, r = 0.301) (Fig. 4c). These data support the existence of an integrin αvβ5-FARP1-CDC42 axis that promotes cancer development.

To assess the importance of this interaction in gastric cancer cell motility, we used SB273005 (Selleck Chemicals, Houston, TX, USA), a potent integrin antagonist, with a Ki of 1.2 nM and 0.3 nM for the αvβ3 receptor and αvβ5 receptor, respectively. To minimize the effect of integrin αvβ3 inhibition, 0.3 nM SB273005 was used because higher concentrations have been reported to inhibit integrin αvβ3 as well. SB273005 significantly decreased the cell motility in control cells but did not change in FARP1-knockdown cells (Fig. 4d, e). In addition, SB273005 significantly decreased filopodium formation and cell motility in FARP1-overexpressing cells but not those in EGFP-overexpressing cells (Fig. 5a–h). Moreover, SB273005 decreased the amount of GTP-CDC42 in FARP1-overexpressing GSU and MKN7 cells (Fig. 5i, j). These results consistent with that integrin αvβ5 signaling enhances to activate FARP1.

Fig. 5. Inhibition of integrin αvβ5 receptor decreases FARP1-induced filopodium formation, cell motility, and CDC42 activation.

a, b Immunofluorescence staining for actin (red) and DAPI (blue). c, d Number and length of filopodia of the FLAG-EGFP- or FLAG-FARP1-expressing GSU and MKN7 cells. e, f Transwell migration and invasion assay in the FLAG-EGFP or FLAG-FARP1-expressing GSU and MKN7 cells. g, h Numbers of migratory and invasive cells among the FLAG-EGFP- or FLAG-FARP1-expressing GSU and MKN7 cells. i, j Active CDC42 pulldown assay in GSU and MKN7 cells infected with the FLAG-EGFP- or FLAG-FARP1-expressing lentivirus. In (a, b, i, and j), the cells were starved in serum-free medium for 24 h and stimulated with 10% FBS for 2 h, and simultaneously, 0.03% DMSO or 0.3 nM SB273005 diluted in 0.03% DMSO was applied. White arrow, filopodia. Magnification, ×400; scale bar, 50 μm (a). Magnification, ×200; scale bar, 100 μm (b). In (e and f), 0.03% DMSO or 0.3 nM SB273005 diluted in 0.03% DMSO was applied when cells were inoculated onto the chamber. Magnification, ×100. Scale bar, 500 μm. c, d, g, and h Values represent the means ± SD from six independent fields. ***P < 0.001; n.s. not significant (Student’s t test); RD relative density.

Discussion

The roles of FARP1 expression in cancer development are not well understood. In this study, we showed that FARP1 overexpression was significantly associated with lymphatic invasion, lymph metastasis, and poor prognosis in patients with advanced gastric cancer, and that it promoted gastric cancer cell motility by activating CDC42. FARP1 was recently reported to activate CDC42 in the endothelial barrier17, and a correlation between CDC42 activity and FARP1 expression was identified in pheochromocytoma40. FARP1 was also reported to specifically activate Rac1 in dendrites16 and to be able to activate RhoA, as demonstrated using an Sf9-overexpressing system41. In turn, CDC42 has been considered to contribute to a variety of cellular responses, including cellular transformation, cell division, cell migration, cell invasion, filopodium formation, invadopodium formation, enzyme activity, and cell polarity42. Thus, it appears reasonable to conclude that FARP1 activates CDC42 and facilitates the abilities of cell migration and invasion by promoting the formation of filopodia and invadopodia in gastric cancer. The GSEA results were consistent with this conclusion. Zhou et al.43 also recently reported the clinical significance of FARP1 in gastric cancer using in silico analysis, which is consistent with our results. Shannon et al.20 reported that two GEF-GTPase signaling units, ECT2-CDC42 and TRIO-RAC1, involved in glioblastoma cell migration and invasion. A positive correlation was observed between FARP1mRNA expression and TRIO, PLEKHG3, ITSN1, TIAM2, ARHGEF10 and ARHGEF12 mRNA expression based on TCGA data analysis and TRIO showed the most strongest correlation value (P = 0, r = 0.426) (Supplementary Fig. S8). Therefore, FARP1 and TRIO may involve in gastric cancer cell migration, invasion and poor prognosis in a synergistic manner.

The integrin family, which consists of 24 heterodimeric transmembrane receptors, mediates the interaction between cells and extracellular matrices and is involved in cell adhesion and migration. Several integrin heterodimers have already been reported to be involved in gastric cancer biology44–46. For example, integrin αvβ5 was previously recognized as a putative target for the treatment of several cancers47–49. Recently, the efficacy of cilengitide, a potent and selective inhibitor of integrins αvβ3 and αvβ5, in combination with cytotoxic agents has been reported50,51. However, only two studies have focused on integrin αvβ5 in gastric cancer, and its roles in the development of gastric cancer remain controversial52,53. Our in silico analysis indicated that high mRNA expression levels of integrin β5 were correlated with a poor prognosis of patients with gastric cancer; moreover, we provided the first demonstration of the interaction between FARP1 and integrin αvβ5 in gastric cancer cell lines. In addition, we found that inhibition of the integrin αvβ5 receptor significantly decreased the cell motility capability in high FARP1-expressing gastric cancer cells. This result suggests that inhibition of the FARP1-integrin αvβ5 pathway might improve the survival of patients with high FARP1-expressing gastric cancer.

Although MAP4K4 has been reported to phosphorylate FARP1, the activation mechanisms of FARP1 are poorly understood54,55. FARP1 and its close homolog FARP2 contain an FERM domain, a DH domain, and two PH domains (PH1 and PH2), and share a high degree of sequence identity, excluding the FERM/DH linker. Although their DH-PH-PH domains have abundant tyrosine residues at the PH2/DH interface, crystal structural analysis suggests that an autoinhibitory mechanism by the C terminal portion of the sixth helix, which contains no tyrosine residues in the DH domain, can inhibit phosphorylation mediated by Src or other kinases. For this reason, tyrosine phosphorylation alone appears to be insufficient for triggering the full activation of FARPs56. Alternatively, it was recently reported that the recruitment of FARP1 to the membrane, induced by semaphorin 3A/PlexinA1 signaling combined with the plexinA1–FARP1 interaction, regulates FARP1 activity in dendrites57. Therefore, the suppression of an autoinhibitory mechanism through the conformational change effected by interacting with integrin αvβ5 and phosphorylation by EGFR-MAP4K4 signaling might, in turn, regulate FARP1 activity in gastric cancer cells.

However, the minimum amount of SB273005 required for integrin αvβ5 inhibition was used in this study; therefore, it is likely that SB273005 also affected integrin αvβ3 and gastric cancer cell motility. It has been reported that low (nanomolar) concentrations of the RGD mimetics αvβ3 and αvβ5 cause alterations in integrin αvβ3 and, paradoxically, promote tumor growth and angiogenesis58. This might explain why SB273005 had no impact on the motility of EGFP-overexpressing gastric cancer cells. Therefore, to evaluate the actual inhibitory effect in relation to FARP1 and integrin αvβ5 interaction, additional experiments using specific inhibitors for FARP1-integrin αvβ5 interaction are required.

Overall, this study shows that FARP1 interacts with integrin αvβ5 and promotes cell motility through the activation of CDC42. This is consistent with the observation that the overexpression of FARP1 protein correlates with unfavorable prognosis in patients with advanced gastric cancer. This study is based on a limited number of clinical samples and in vitro experiments using gastric cancer cell lines. Although to confirm the clinical relevance of the findings of this study and the molecular mechanism of FARP1, we must analyze more samples and in vivo experiments, our findings suggest that FARP1 may represent a crucial marker to predict the prognosis of patients with gastric cancer and that the integrin αvβ5-FARP1-CDC42 pathway may serve as a target for molecular therapy in these patients. Thus, regulatory cascade upstream of Rho can be a specific and promising target of advanced cancer treatment.

Materials and methods

In silico analysis to determine the relationship between Rho GEF expression and patient prognosis

Comprehensive analyses and multiple testing corrections at a false discovery rate (FDR) of 10% were performed for 72 Rho GEFs in 593 patients with gastric cancer from GEO datasets using the Kaplan–Meier plotter (http://kmplot.com/analysis/) to evaluate the relationship between Rho GEF expression and prognosis59. We used the default settings (except for GSE62254) according to the software developer’s recommendation. To correct the P value for multiple probes, we used the “multiple hypothesis testing” option, available at the same site, to acquire q values for the FDR.

Drugs, reagents, and antibodies

The following reagents were purchased from the indicated manufacturers: MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) (Sigma-Aldrich); monoclonal antibodies against FARP1 (Novus Biologicals Agent, Cat#H00010160-M01), alpha tubulin (Millipore, Cat# CP06), FLAG (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# F1804), integrin β5 (Cell Signaling Technology, Cat# 4708P), RHOA (Cell Signaling Technology, Cat# 2117), CDC42 (Cell Signaling Technology, Cat# 2466), and RAC1 (packed in RHOA/ RAC1/CDC42 Activation Combo Kit, Cell Biolabs, Cat# STA-405); SB273005 (a potent integrin inhibitor with Ki of 1.2 and 0.3 nM for αvβ3 receptor and αvβ5 receptor, respectively) (Selleck Chemicals).

Patients and tumor samples

This study included 91 consecutive patients with advanced gastric cancer who underwent gastrectomy at the Department of Digestive Surgery, Breast and Thyroid Surgery of Kagoshima University Hospital from April 2002 to March 2011 (Table 1). Patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy or had remnant gastric cancer and multiple primary cancers were excluded. The clinical samples were obtained from tumors removed during surgery and ultimately diagnosed as gastric cancer pathologically. The pathological features of gastric cancer were classified according to the TNM classification, seventh edition60.

Immunohistochemical analysis and capture of histological images

The surgical samples were fixed in 10% formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin before being cut into 3-µm-thick slices. Deparaffinization, hydrophilization, and target retrieval were performed using the PT Link system (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked using 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol. After the sections were washed with PBS, they were preincubated in 1% bovine serum albumin for 30 min to block nonspecific reactions at room temperature. The sections were incubated with the FARP1 mouse monoclonal antibody (1:400 dilution) as the primary antibody overnight at 4 °C. Staining was performed using the avidin–biotin complex and immunoperoxidase method (Vectastatin ABC Kit, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). The sections were visualized using diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride, and nuclei were stained with hematoxylin. The images of the specimens were obtained using an Aperio CS2 scanner (Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

Evaluation of FARP1 protein expression

FARP1 staining was performed in the most invasive portion of tumors and observed across five microscopic fields (magnification, ×200). The expression level of FARP1 was scored according to the intensity of cytoplasmic staining as negative (0), weak (1), moderate (2), or strong (3) (Fig. 1d), and the percentage of stained tumor cells was scored as 0% (0), 1–10% (1), 11–50% (2), 51–80% (3), or 81–100% (4). Scores were multiplied to obtain the immunoreactivity score (IRS), ranging from 0 to 12, as described previously61. The IRS value were evaluated independently by two board-certified pathologists those are unaware of clinical data. The accordance was 86/91 (94.5%) and the inconsistent cases were re-evaluated by the two pathologists under agreement (I.K. and A.T). Patients were divided into two groups of high or low FARP1 expression based on the median IRS value.

Cell lines and culture

To investigate the molecular role of FARP1 in the development of gastric cancer, we used four gastric cancer cell lines. The human gastric cancer cell lines MKN7 (RCB Cat# RCB0999, RRID: CVCL_1417), MKN45 (RCB Cat# RCB1002, RRID: CVCL_2791), MKN74 (RCB Cat# RCB1001, RRID: CVCL_0434), and GSU (RCB Cat# RCB2278, RRID: CVCL_8877) were obtained from RIKEN BioResource Center (Tsukuba, Japan). The cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with antibiotics (100 U/mL penicillin) and 10% FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). All cancer cell lines were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

RNA isolation and reverse transcription-quantitative (q)PCR

Total RNA from the cultured cells was isolated using TRIzol (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH, USA) and reverse-transcribed using the ReverTra Ace kit (Toyobo, Oosaka, Japan), according to the manufacturer’s instructions62.

The mRNA expression levels of FARP1 were determined by qPCR on the Step One Plus system (Applied Biosystems) with the forward primer 5′-CATTCTATCCGGAGCCTTGC-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-GGAACCTTCGGTTCCTTTCC-3′ using GoTaq qPCR Master Mix (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Human GAPDH was used for normalization with the forward and reverse primers 5′-TGCACCACCAACTGCTTAG-3′ and 5′-GAGGCAGGGATGATGTTC-3′, respectively. The expression of the target gene was quantified using the comparative cycle threshold method. The primers were synthesized by FASMAC (Kanagawa, Japan).

Protein extraction and immunoblotting

The total cell lysate was isolated using RIPA buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate) and a proteinase inhibitor cocktail (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan). Protein concentrations were measured using Protein Assay CBB Solution (5×) (Nacalai Tesque). Cell lysates were separated by 5–20% SDS-PAGE (ATTO, Amherst, NY, USA) and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. The blotted membranes were incubated with anti-FARP1 (1:750 dilution), anti-alpha-tubulin (1:1000 dilution), anti-FLAG (1:1000 dilution), anti-RAC1 (1:1000 dilution), anti-CDC42 (1:500), anti-RHOA (1:500), or anti-integrin β5 (1:750 dilution) antibody overnight at 4 °C, and each protein was detected as described previously63.

siRNA transfection

FARP1 siRNA1 (5′-CAAAUUUCAUACUAAUUUU-3′) and siRNA2 (5′-CCUUCUUUAGACUUUUUGA-3′) were synthesized by FASMAC. FARP1 siRNA1, FARP1 siRNA2, and Silencer Negative Control No. 1 siRNA (NC Si) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were transfected to MKN45 and MKN74 cells at 50 nM each using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in serum-free medium for 24 h.

FARP1 lentivirus expression vector construct

Full-length FARP1 open reading frame (ORF) cDNA along with a FLAG Tag was obtained from MKN45 cells by reverse transcription-qPCR with the forward primer 5′-TAGCTAGCACCATGGACTACAAGGACGACGATGACAAGGGAGAAATAGAGCAGAGGCC-3′ and reverse primer 5′-TAGCGGCCGCTCAATACACA AGAGACTCTT-3′ synthesized by FASMAC. PCR products were purified and confirmed by DNA sequencing. The EGFP ORF was acquired from pEGFP-C2 (Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, CA, USA). These cDNAs, along with a FLAG Tag, were ligated into CSII-CMV-MCS-IRES2-Bsd (RIKEN BioResource Center). FARP1 and EGFP expression recombinant lentiviruses were produced by cotransfection of 293T cells with CSII-CMV-MCS-IRES2-Bsd-FLAG-FARP1 or CSII-CMV-MCS-IRES2-Bsd-FLAG-EGFP, together with the lentivirus packaging plasmids pMDLg/pRRE, pRSV-REV, and pMD2.G (Addgene, Cambridge, MA, USA) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). MKN7 and GSU cells were infected with the lentivirus for 48 h and then incubated with 5 µg/mL blasticidin S hydrochloride (Kaken Pharmaceuticals, Tokyo, Japan) for at least 5 days.

Cell proliferation assay

Equal numbers of cells (1 × 103) were seeded into 96-well plates and incubated for 1, 3, 5, and 7 days. Cell viability was measured using the MTT colorimetric assay64. These experiments were performed independently at least three times.

Transwell migration and invasion assay

BioCoat Control Inserts and BioCoat Matrigel Invasion Chamber (24-well, 8 µm; Corning, Corning, NY, USA) were used for cell migration and invasion assays. Chamber membranes of the control inserts were coated with 10 µg/mL fibronectin (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were inoculated with serum-free medium into the top chamber, and the bottom chamber was filled with medium containing 10% FBS and 1 ng/mL epidermal growth factor (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA). The numbers of inoculated cells were as follows: MKN45, 3.0 × 105; MKN74, 1.5 × 105; MKN7, 1.5 × 105; and GSU, 1.0 × 105. MKN74 and GSU cells were incubated for 48 h, and MKN45 and MKN7 cells were incubated for 72 h. After incubation, the bottom membranes were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with hematoxylin. Cell numbers were counted in six fields under a microscope. These experiments were performed independently at least three times.

Rho small GTPase pulldown assay

Cells were incubated until they reached approximately 80–90% confluence, after which they were starved in serum-free medium for 24 h and stimulated with 10% FBS for 2 h (serum stimulation) as described previously10. The total cell lysate was isolated using RIPA buffer without SDS. Cell lysates were incubated with PAK1 RBD or Rhotekin PBD agarose beads (Cell Biolabs) for 1 h at 4 °C. GTP-RAC1, GTP-CDC42, and GTP-RHOA were detected by immunoblotting. Densities of the individual bands were quantified using ImageJ software (RRID: SCR_003070; National Institutes of Health). The densities of GTP-form bands were normalized to the densities of bands of each total Rho family protein. Relative densities (RDs) were obtained by comparisons with the density of each GTP-form band of FLAG-EGFP–expressing cells.

Immunoprecipitation

The total cell lysate was isolated using RIPA buffer without SDS. Cell lysates were incubated with anti-FLAG antibody, followed by COSMOGEL (R) Ig Accept Protein G (Nacalai Tesque) for 1 h at 4 °C. FLAG and integrin β5 were detected by immunoblotting.

Immunofluorescence

Cells (1.0 × 104) were seeded into a four-chamber CELLview cell culture dish (Greiner Bio-One, Kremsmuenster, Austria). The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature, followed by permeabilization with PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin and 0.3% Triton X-100. The cells were subjected to immunofluorescence staining for actin using ActinRed 555 ReadyProbes (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 30 min at room temperature and then incubated with DAPI (Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan) (1:4000 dilution) for 10 min at room temperature. The cells were subjected to immunofluorescence staining for FARP1 using anti-FARP1 antibody (1:200 dilution) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by treating with Alexa Fluor 647 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK, Cat# ab150115) (1:500 dilution) as secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated with DAPI for 10 min at room temperature. The images of cells were obtained using Axio Observer Z1 (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). The number and length of filopodia over 1 μm were quantified using ImageJ software in six fields.

GSEA in gastric cancer data from TCGA

TCGA stomach cancer RNA-Seq (level 3) data, recorded as log2(x + 1) transformed read per kilobase of exon per million mapped reads (RPKM) values, were downloaded from UCSC Xena (http://xena.ucsc.edu). The gene expression levels of FARP1 and integrin β5 in solid normal tissue and primary tumor were compared and correlation for these gene expression level in primary tumor was generated using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. GSEA was performed using GSEA v3.0 (Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA, USA). The FARP1 expression level was divided into low and high categories to annotate phenotype, and gene sets (CELL_MIGRATION, CROMER_METASTASI_UP, BIOCARTA_CDC42RAC_PATHWAY, and GO_INVADOPODIUM) from Molecular Signature Database v6.1 (http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp) were used. All other parameters were set based on their default values65. An FDR q value < 0.25 or nominal P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Statistical analysis

All statistical calculations were carried out using EZR66. Statistical analyses of group differences were performed using the χ2 test with Yate’s continuity correction and unpaired, two-sided Student’s t test. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were generated to compare the high and low FARP1 expression groups using the log-rank test. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Error bars represent standard deviations.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Hiroshi Okumura for his useful advice; Ms. Naoko Hidaka and Ms. Izumi Minamimagari for their excellent secretarial assistance; and Ms. Chieri Nakayama, Ms. Rie Tajiri, Ms. Mika Tokunaga, Ms. Maki Motomura, Ms. Aya Harada, and Ms. Tomoko Takajo for their excellent technical assistance. We also wish to thank the Joint Research Laboratory, Kagoshima University Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences, for allowing us to use their facilities, as well as Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing. This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP22501047, JP16K07121, JP16K10465, JP16K10509, JP16K10508, JP17H04285, JP17K10871, JP17K07221, JP18K07239, JP 18K15248, and JP18K16590.

Author contributions

T.H., Y.S. and T.F. designed this study. T.H., Y.S., K.M. and T.F. contributed to interpretation of data. T.H., Y.S., K.T. and T.F. contributed to writing the manuscript. Y.K., T.F. and S.N. supervised the study. T.H., Y.S., N.H., M.K., M.S., K. Minami, M.S., M.Y., K.K., I.K. and A.T. performed research. T.A., S.Y., D.M., Y.U. and S.I. helped to collect clinical specimens and data. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kagoshima University (reference number: S28002 and Henko 25-39), and performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Takuro Hirano, Yoshinari Shinsato

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at (10.1038/s41389-020-0190-7).

References

- 1.Van Cutsem E, Sagaert X, Topal B, Haustermans K, Prenen H. Gastric cancer. Lancet. 2016;388:2654–64. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30354-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagini S. Carcinoma of the stomach: a review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, molecular genetics and chemoprevention. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2012;4:156–169. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v4.i7.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torre LA, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wagner AD, et al. Chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010;3:CD004064. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004064.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pyrhönen S, Kuitunen T, Nyandoto P, Kouri M. Randomised comparison of fluorouracil, epidoxorubicin and methotrexate (FEMTX) plus supportive care with supportive care alone in patients with non-resectable gastric cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 1995;71:587–591. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minard ME, Herynk MH, Collard JG, Gallick GE. The guanine nucleotide exchange factor Tiam1 increases colon carcinoma growth at metastatic sites in an orthotopic nude mouse model. Oncogene. 2005;24:2568–2573. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu D, Asiedu M, Wei Q. Myosin-interacting guanine exchange factor (MyoGEF) regulates the invasion activity of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells through activation of RhoA and RhoC. Oncogene. 2009;28:2219–2230. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qin J, et al. Upregulation of PIP3-dependent Rac exchanger 1 (P-Rex1) promotes prostate cancer metastasis. Oncogene. 2009;28:1853–1863. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirata D, et al. Involvement of epithelial cell transforming sequence-2 oncoantigen in lung and esophageal cancer progression. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009;15:256–266. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fukushima H, et al. ARHGEF15 overexpression worsens the prognosis in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma through enhancing the motility and proliferative activity of the cancer cells. Mol. Cancer. 2016;15:32. doi: 10.1186/s12943-016-0516-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lazer G, Katzav S. Guanine nucleotide exchange factors for RhoGTPases: good therapeutic targets for cancer therapy? Cell Signal. 2011;23:969–979. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wennerberg K, Rossman KL, Der CJ. The Ras superfamily at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118:843–846. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karlsson R, Pedersen ED, Wang Z, Brakebusch C. Rho GTPase function in tumourigenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1796:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bos JL. Ras oncogenes in human cancer: a review. Cancer Res. 1989;49:4682–4689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koyano Y, et al. Molecular cloning and characterisation of CDEP, a novel human protein containing the ezrin-like domain of the band 4.1 superfamily and the Dbl homology domain of Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factors. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;241:369–375. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheadle. L, Biederer T. The novel synaptogenic protein farp1 links postsynaptic cytoskeletal dynamics and transsynaptic organization. J. Cell Biol. 2012;199:985–1001. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201205041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amado-Azevedo J, et al. A CDC42-centered signaling unit is a dominant positive regulator of endothelial integrity. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:10132. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10392-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lane J, Martin TA, Mansel RE, Jiang WG. The expression and prognostic value of the guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) Trio, Vav1 and TIAM-1 in human breast cancer. Int. Semin. Surg. Oncol. 2008;5:23. doi: 10.1186/1477-7800-5-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Mascarel I, et al. Comprehensive prognostic analysis in breast cancer integrating clinical, tumoral, micro-environmental and immunohistochemical criteria. SpringerPlus. 2015;4:528. doi: 10.1186/s40064-015-1297-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shannon P, et al. Cdc42 and the guanine nucleotide exchange factors Ect2 and trio mediate Fn14-induced migration and invasion of glioblastoma cells. Mol. Cancer Res. 2012;10:958–968. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-11-0616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salhia B, et al. The guanine nucleotide exchange factors Trio, Ect2, and Vav3 mediate the invasive behavior of glioblastoma. Am. J. Pathol. 2008;173:1828–1838. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murray D, Horgan G, MacMathuna P, Doran P. NET1-mediated RhoA activation facilitates lysophosphatidic acid-induced cell migration and invasion in gastric cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 2008;99:1322–1329. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen SQ, Li K, Zhu N, Nakao A. Expression and clinical significance of NET-1 and PCNA in hepatocellular carcinoma. Med. Oncol. 2008;25:341–345. doi: 10.1007/s12032-008-9042-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Michael Z, et al. Coexpression of α6β4 integrin and guanine nucleotide exchange factor Net1 identifies node-positive breast cancer patients at high risk for distant metastasis. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2009;18:80–86. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tu Y, et al. Over-expression of neuroepithelial-transforming protein 1 confers poor prognosis of patients with gliomas. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;40:388–394. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyp186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lahiff C, et al. Expression of neuroepithelial transforming gene 1 is enhanced in oesophageal cancer and mediates an invasive tumour cell phenotype. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013;32:55. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-32-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sano M, et al. Expression level of ECT2 proto-oncogene correlates with prognosis in glioma patients. Oncol. Rep. 2006;16:1093–1098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iyoda M, et al. Epithelial cell transforming sequence 2 in human oral cancer. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e14082. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen J, et al. ECT2 regulates the Rho/ERK signalling axis to promote early recurrence in human hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2015;62:1287–1295. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jin Y, et al. Up-regulation of ECT2 is associated with poor prognosis in gastric cancer patients. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2014;7:8724–8731. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luo Y, et al. Elevated expression of ECT2 predicts unfavorable prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2015;73:135–139. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen JS, Su IJ, Leu YW, Young KC, Sun HS. Expression of T-cell lymphoma invasion and metastasis 2 (TIAM2) promotes proliferation and invasion of liver cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 2012;130:1302–1313. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao ZY, et al. TIAM2 enhances non-small cell lung cancer cell invasion and motility. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2013;14:6305–6309. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.11.6305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saito S, et al. Rho exchange factor ECT2 is induced by growth factors and regulates cytokinesis through the N-terminal cell cycle regulator-related domains. J. Cell. Biochem. 2003;90:819–836. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palmby TR, Abe K, Karnoub AE, Der CJ. Vav transformation requires activation of multiple GTPases and regulation of gene expression. Mol. Cancer Res. 2004;2:702–711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okada T, et al. Integrin-α10 dependency identifies RAC and RICTOR as therapeutic targets in high-grade myxofibrosarcoma. Cancer Discov. 2016;6:1148–1165. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gilcrease MZ, et al. Coexpression of α6β4 integrin and guanine nucleotide exchange factor Net1 identifies node-positive breast cancer patients at high risk for distant metastasis. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2009;18:80–86. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu Y, et al. FERM domain-containing unconventional myosin VIIA interacts with integrin β5 subunit and regulates αvβ5-mediated cell adhesion and migration. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:2859–2866. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hu J, et al. FERM domain-containing protein FRMD5 regulates cell motility via binding to integrin β5 subunit and ROCK1. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:4348–4356. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Croisé P, et al. Cdc42 and Rac1 activity is reduced in human pheochromocytoma and correlates with FARP1 and ARHGEF1 expression. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 2016;23:281–293. doi: 10.1530/ERC-15-0502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koyano Y, et al. Chondrocyte-derived ezrin-like domain containing protein (CDEP), a rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor, is inducible in chondrocytes by parathyroid hormone and cyclic AMP and has transforming activity in NIH3T3 cells. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2001;9:S64–S68. doi: 10.1053/joca.2001.0446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qadir MI, Parveen A, Ali M. Cdc42: role in cancer management. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2015;86:432–439. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.12556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou YY, et al. Combination of TNM staging and pathway based risk score models in patients with gastric cancer. J. Cell. Biochem. 2018;119:3608–3617. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chi F, Fu D, Zhang X, Lv Z, Wang Z. Expression of the c-Met proto-oncogene and integrin α5β1 in human gastric cardia adenocarcinoma. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2012;76:1471–1476. doi: 10.1271/bbb.120132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhuang Z, et al. Clinical significance of integrin αvβ6 expression effects on gastric carcinoma invasiveness and progression via cancer-associated fibroblasts. Med. Oncol. 2013;30:580. doi: 10.1007/s12032-013-0580-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lian PL, et al. Integrin alphavbeta6 and matrix metalloproteinase 9 correlate with survival in gastric cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016;22:3852–3859. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i14.3852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilisch-Neumann A, et al. The integrin inhibitor cilengitide affects meningioma cell motility and invasion. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013;19:5402–5412. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cheng NC, Van Zandwijk N, Reid G. Cilengitide inhibits attachment and invasion of malignant pleural mesothelioma cells through antagonism of integrins αvβ3 and αvβ5. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e90374. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ruffini F, et al. Cilengitide downmodulates invasiveness and vasculogenic mimicry of neuropilin 1 expressing melanoma cells through the inhibition of αvβ5 integrin. Int. J. Cancer. 2015;136:E545–E558. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haddad T, et al. A phase I study of cilengitide and paclitaxel in patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Chemother. Pharm. 2017;79:1221–1227. doi: 10.1007/s00280-017-3322-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vansteenkiste J, et al. Cilengitide combined with cetuximab and platinum-based chemotherapy as first-line treatment in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients: results of an open-label, randomized, controlled phase II study (CERTO) Ann. Oncol. 2015;26:1734–1740. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Böger C, et al. Integrins αvβ3 and αvβ5 as prognostic, diagnostic, and therapeutic targets in gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:784–795. doi: 10.1007/s10120-014-0435-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kawahara E, Ooi A, Nakanishi I. Integrin distribution in gastric carcinoma: Association of β3 and β5 integrins with tumor invasiveness. Pathol. Int. 1995;45:493–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1995.tb03491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schwaid AG, et al. MAP4K4 is a threonine kinase that phosphorylates FARP1. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015;10:2667–2671. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang X, et al. Identifying novel targets of oncogenic EGF receptor signalling in lung cancer through global phosphoproteomics. Proteomics. 2015;15:340–355. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201400315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.He X, Kuo YC, Rosche TJ, Zhang X. Structural basis for autoinhibition of the guanine nucleotide exchange factor FARP2. Structure. 2013;21:355–364. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cheadle L, Biederer T. Activity-dependent regulation of dendritic complexity by semaphorin 3A through Farp1. J. Neurosci. 2014;34:7999–8009. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3950-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reynolds. AR, et al. Stimulation of tumor growth and angiogenesis by low concentrations of RGD-mimetic integrin inhibitors. Nat. Med. 2009;15:392–400. doi: 10.1038/nm.1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Szász AM, et al. Cross-validation of survival associated biomarkers in gastric cancer using transcriptomic data of 1,065 patients. Oncotarget. 2016;7:49322–49333. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sobin, L. H., Gospodarowicz, M. K. & Wittekind, C. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors Vol. 7 (Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford, 2010).

- 61.Venerito M, et al. The long-term effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on COX-1/2, 5-LOX and leukotriene receptors in patients with a risk gastritis phenotype—a link to gastric carcinogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2008;270:218–228. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shinsato Y, et al. Reduction of MLH1 and PMS2 confers temozolomide resistance and is associated with recurrence of glioblastoma. Oncotarget. 2013;4:2261–2270. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Che XF, et al. Overexpression of survivin in primary ATL cells and sodium arsenite induces apoptosis by down-regulating survivin expression in ATL cell lines. Blood. 2006;107:4880–4887. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Subramanian A, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software “EZR” for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2013;48:452–458. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.