Abstract

As one of the best-studied RNA binding proteins in plant, pentatricopeptide repeats (PPRs) protein are mainly targeted to mitochondria and/or chloroplasts for RNA processing to regulate the biogenesis and function of the organelles, but its molecular mechanism and role in development remain to be further revealed. Here, we identified a mitochondria-localized P-type small PPR protein, MITOCHONDRION-MEDIATED GROWTH DEFECT 1 (MID1) that is crucial for Arabidopsis development. Mutation in MID1 causes retarded embryo development and stunted plant growth with defects in cell expansion and proliferation. Molecular experiments showed that MID1 is required for the splicing of the nad2 intron 1 in mitochondria. Consistently, mid1 plants display significant reduction in the abundance and activity of mitochondrial respiration complex I, accompanied by abnormal mitochondrial morphology and energy metabolism. Furthermore, MID1 is associated with other trans-factors involved in NICOTINAMIDE ADENINE DINUCLEOTIDE HYDROGEN (NADH) DEHYDROGENASE SUBUNIT 2 (nad2) intron 1 splicing, and interacts directly with itself and MITOCHONDRIAL STABILITY FACTOR 1 (MTSF1). This suggests that MID1 most likely functions as a dimer for nad2 intron 1 splicing. Together, we characterized a novel PPR protein MID1 for nad2 intron 1 splicing.

Subject terms: Plant development, Seed development

Introduction

Mitochondrion, originated from the gram-negative bacterium ancestors, is an essential organelle of eukaryotic organisms that can produce energy and signaling molecules for their growth and development1–3. Most of the mitochondrial genes have been transferred and integrated into nuclear genome during evolutionary progress, and the remaining genes encode a limited number of proteins that mainly make up the respiration complexes and translation machinery4–7. Thus, mitochondria are semi-autonomous organelles that require pathways to coordinate the two genomes for biogenesis and function8,9. Among the pathways controlling mitochondrial genes expression are RNA binding proteins-mediated post-transcriptional events in mitochondria such as RNA stability, RNA editing, intron splicing and translation10–13. Genetic studies have shown that these molecular events are critical for mitochondrial function and plant development11,14. Although the molecular function of many mitochondrion-localized RNA binding proteins has been characterized, their precise molecular action remains to be further unveiled.

In plants, most of the well-characterized RNA-binding proteins involved in post-transcriptional regulation of mitochondrial genes are PPR proteins, which are defined by tandem arrays of degenerate 35 amino acid motif11,15. PPR proteins are first discovered by in silico study of incomplete Arabidopsis genome for genes targeting to mitochondrion and chloroplast16. The striking feature of this family is its massive expansion in terrestrial plants, about 450 members in Arabidopsis and 477 members in rice17,18. These proteins can be divided into two groups based on the PPR motif length: P-type and PLS-type, and further into several subgroups based on the C-terminal characteristics17,19. The P-type PPR proteins only consist of the 35-amino-acid classic PPR (P) motifs, while the PLS-type ones have P and longer (L) or shorter (S) PPR motifs, with extra domains at the carboxyl terminus. Consistent with the initial bioinformatics study, the majority of studied PPR proteins are localized to mitochondria and/or chloroplasts, where they usually function in diverse RNA metabolic processes including intron splicing, editing, stabilization and translation11. Moreover, the activity of PPR proteins, especially their binding codes, have been progressively elucidated through bioinformatics and structural analysis20–26. Similar to classic RNA-binding protein Pumilio and FBF (PUF)27, PPR proteins bind RNA targets in a modular fashion, with each PPR motif specifically recognizing one nucleoside and two amino acids at the 5th and 35th of the PPR motif primarily determining the nucleoside specificity11,24. Although great advances have been made on understanding PPR codes, the action mode of PPR proteins is uncertain. Some PPR proteins were reported to play roles in a dimer manner, such as HIGH CHLOROPHYLLFLUORESCENCE 152 (HCF152) and THYLAKOID ASSEMBLY 8 (THA8), two chloroplast-localized PPR proteins involved in RNA processing and splicing respectively28–30. PPR4 and PPR5 are two examples that they exist as monomers to function in rps12 trans-splicing and stability of t-RNA precursor in chloroplasts31,32. However, PPR10, one of best characterized PPR proteins, is still in debate that whether it acts in a dimer or monomer manner to perform function24,33–35.

RNA splicing, a common event taking place in nucleus and organelles of eukaryotic organisms, is a necessary step in post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression36. While the constituents and action mode of spliceosome that splices intron in the nucleus have been extensively studied37, little is known about the splicing machinery responsible for excision of mitochondrial introns. Previous genetic studies have led to the identification of several P-type PPR proteins as necessary factors involved in mitochondrial intron splicing in model species Arabidopsis thaliana and Zea mays. For example, ABA OVERLY SENSITIVE 5 (ABO5), BUTHIONINE SULFOXIMINE (BSO)-INSENSITIVE ROOT 6 (BIR6), MITOCHONDRIAL INTRON SPLICING FACTOR 26 (MISF26), MISF74, MITOCHONDRIAL TRANSLATION FACTOR1 (MTL1), ORGANELLE TRANSCRIPT PROCESSING 43 (OTP43), OTP439, TANG2, SLOW GROWTH3 (SLO3), are required for splicing of some introns of nad genes in Arabidopsis38–45. Interestingly, MISF68 and MISF74 are two P-type PPR proteins reported to function in more than one introns splicing in mitochondria45. EMPTY PERICARP 10 (EMP10), EMP11, EMP16 and DEFECTIVE KERNEL (DEK) 2, DEK35, are involved in the splicing of some introns of nads in maize44,46–49. Besides, some PLS-type PPR proteins which are usually characterized to function in RNA editing, are also implicated in RNA splicing. SLO4 is reported to affect nad2 intron 1 splicing50. A PLS-DYW member, PpPPR43 influences the CYTOCHROME C OXIDASE 1(cox1) intron 3 splicing in Physcomitrella patens51. Furthermore, other trans-factors implicated in RNA splicing have also been identified, such as CHLOROPLAST RNA SPLICING AND RIBOSOME MATURATION (CRM) proteins, PLANT ORGANELLAR RNA RECOGNITION (PORR) proteins, DEAD-BOX RNA-HELICASEs, MITOCHONDRIAL TRANSCRIPTION TERMINATION FACTORs (mTERFs), REGULATOR of CHROMOSOME CONDENSATION (RCC) proteins, RAD52-LIKE PROTEINS AND NUCLEAR MATURASEs (nMATs)41,52–59. How PPR proteins cooperate with these trans-factors to promote introns splicing is not clear. Deciphering the relationship among the previously found splicing factors and identifying their RNA-binding sites will be of great significance to understand the molecular mechanism underlying the mitochondrial RNA splicing.

In this study, we isolated a mutant defective in embryo development and vegetative growth, designated mitochondrion-mediated growth defect 1 (mid1) according to its molecular and physiological function. We showed here that MID1 encodes a mitochondria-localized PPR protein with only four PPR motifs and is responsible for the splicing of intron 1 in the nad2 gene. Loss of MID1 function severely impairs the abundance and activity of mitochondrial respiration complex I, which further leads to the abnormal mitochondrial morphology and energy metabolism. In addition, MID1 is associated with other trans-factors to function in nad2 splicing. Together, we propose that MID1-mediated RNA splicing is necessary for mitochondrion biogenesis and function, and further plays a critical role in plant development.

Results

Isolation of embryo-defective mutants

To isolate embryo-defective mutants, a distorted Mendelian segregation screen was performed as previously reported60,61. mid1 was one of the mutants in which the kanamycin-resistant to kanamycin-sensitive separation ratio of selfed F2 progeny was 2.63:1 (n = 781), indicating that there was a minor deficiency in mid1 embryogenesis62. The reciprocal crosses between mid1/+ and wild-type plants were subsequently conducted to further confirm this speculation. When the pistil of the wild-type was pollinated with pollen from mid1/+ plant, the segregation ratio was 0.91:1(n = 410), and vice versa (0.98:1, n = 1306). The ratio was close to the expected 1:1, indicating that the Ds insertion did not disrupt the male and female gametophyte function. Thus, mid1 is most likely an embryo-defective mutant.

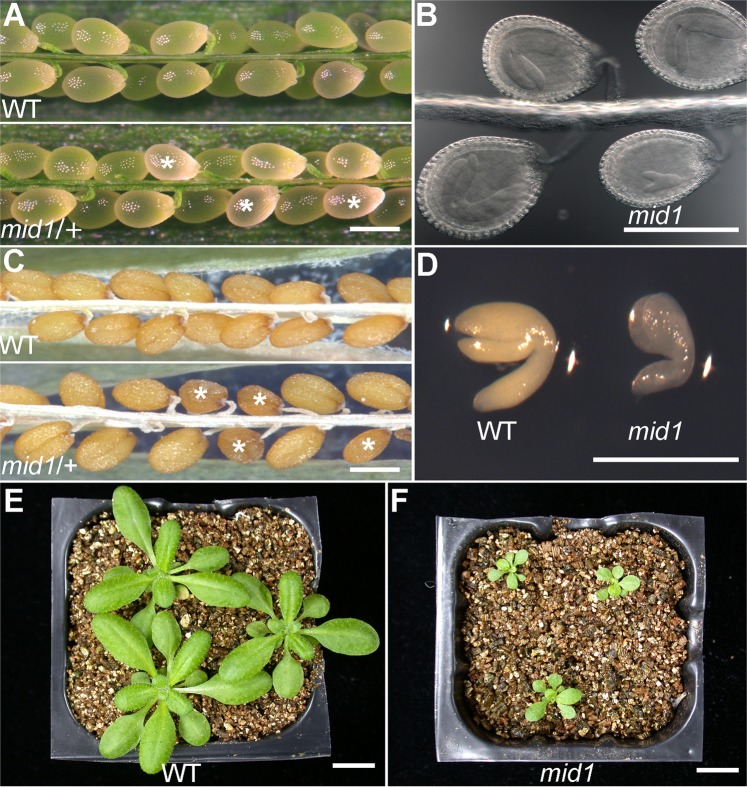

MID1 is required for embryonic and post-embryonic development

To investigate the embryo phenotype, we dissected siliques of wild-type and mid1/+ plants, followed by whole-mount clearing and elaborate microscopic examination. Compared to the synchronous development of wild-type embryos (Fig. 1A), there was a significant developmental discrepancy in embryos of mid1/+ siliques (Fig. 1A,B). For example, at 8-days post pollination (DPP), the wild-type embryos were all at curled cotyledon stage, while about 25% embryos (195:790) of mid1/+ were still at torpedo stage (Fig. 1B). However, the mutant embryos in the mid1/+ were able to reach mature stage, and finally form small brown shrunk seeds harboring small but intact embryos (Fig. 1C,D), indicating that mid1 caused retarded embryogenesis. In addition to the delayed embryogenesis described above, mid1 also impairs the post-embryonic development, characterized by stunted plant growth. For example, the 4-week-old mid1 plant was much smaller than the wild-type (Fig. 1E,F). These results demonstrate that MID1 is crucial for both embryonic and post-embryonic development in Arabidopsis.

Figure 1.

Phenotypes of mid1. (A) Seed set of wild-type and mid1/+ siliques at 8 DPP. The wild-type shows a full seed set while approximately one-quarter of ovules in the mid1/+ silique are abnormal. Asterisks indicate the mid1 ovules. (B) Whole-mounted ovules from silique of mid1/+ plant in (A). (C) Seeds in the mature silique of wild-type and mid1/+. Compared to the wild-type, about one-quarter of the seeds in mid1/+ display shrunken morphology. (D) Embryos dissected from mid1/+ plant. (E) 4-week-old wild-type plants. (F) 4-week-old mid1 plants. (A,F) Bars = 200 μm; (E,F) Bars = 1 cm.

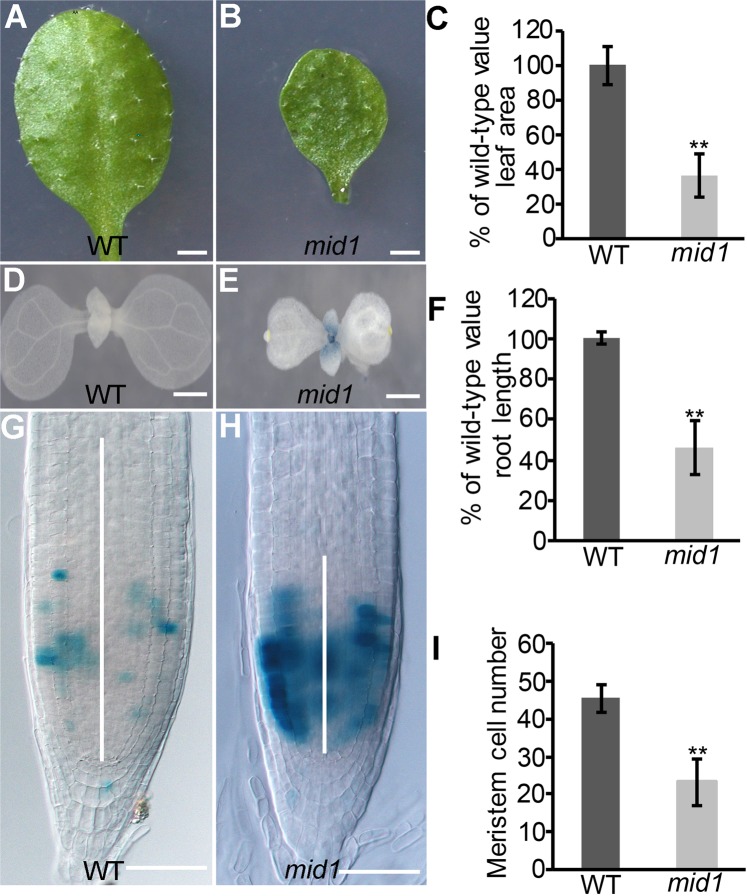

Cell expansion and proliferation are compromised in mid1

One of the distinct phenotypes of mid1 is its dwarfism morphology during the whole life cycle, such as small seed, small leaf and stunted root. Previous studies have indicated that cell proliferation and expansion are the main determinants controlling organ size63. In order to confirm the cellular basis responsible for the smallness, we checked the capacity of cell expansion and proliferation in diverse organs of mid1. In Arabidopsis, the fifth leaf is the first fully developed leaf and widely used as the representative organ to assess cell expansion capacity63. First, we found that the fifth leaf of mid1 was much smaller than the wild-type (Fig. 2A–C). Then, we investigated the cell area of the fifth leaf to determine whether the cell size contribute to the small leaf size. The mid1 leaf cell area was dramatically decreased, about 30% of the wild-type counterpart (Fig. S1A). Second, we investigated mid1 cell proliferation capacity by monitoring the mitotic index through introducing the mitotic activity reporter CYCB1;1-GUS (for β-glucuronidase) into mid164. Indeed, histochemical staining of 8-day-old seedling showed that CYCB1;1-GUS was expressed in young leaves of mid1 while nearly no GUS expression was detected in wild-type plant (Fig. 2D,E), a evidence that many leaf cells in mid1 were retarded at G2/M phase, thus implying that mid1 is deficient in leaf cell proliferation. Next, we also evaluated the effect of MID1 mutation on the root development. Similarly, the root of mid1 seedling was short (Fig. 2F) and there were more root meristem cells expressing CYCB1;1-GUS of 8-day-old mid1 seedlings compared to the wild-type (Fig. 2G,H), indicating that loss-function of MID1 also impaired the root cell proliferation in roots. Consistently, the root meristem cell size, determined by the cortical cell number in the region from quiescent center to the first elongation cell65,66, was greatly reduced in mid1 (Fig. 2I). To check whether cell expansion was also altered in mid1 roots, we measured cell length at the maturation region and found that the mid1 cell length was dramatically shorter than that of the wild-type, suggesting that root cell expansion was also impaired in mid1 root (Fig. S1B).

Figure 2.

Cellular defects of mid1. (A) Fifth leaf of 4-week-old wild-type plant. Bar = 0.3 cm. (B) Fifth leaf of 4-week-old mid1 plant. Bar = 0.3 cm. (C) Leaf area measurement of wild-type and mid1. Data are the mean ± SE; n = 35. Student’s t tests were used to analyze differences between WT and mid1. Double asterisks represent highly significant differences, **P < 0.01. (D) Distribution of CYCB1;1-GUS in the 8-day-old wild-type true leaf. Bar = 1 mm. (E) Distribution of CYCB1;1-GUS in the 8-day-old mid1 true leaf. Bar = 1 mm. (F) Primary root length of 8-day-old wild-type and mid1 seedlings. Data are the mean ± SE, n = 40. Student’s t tests, **P < 0.01. (G,H) Expression of CYCB1;1-GUS in the root meristem of 8-day-old wild-type and mid1. The white lines indicate the meristem zone. Bars = 50 μm. (I) Root meristem cells number of 8-day-old wild-type and mid1 seedlings. The root meristem cells are defined by the number of cortex cells in the cortical file extending from the QC to the transition zone. Data are the mean ± SE, n = 40. Student’s t tests, **P < 0.01.

Furthermore, we performed the callus induction experiments to confirm the causal relationship between mid1 phenotypes and cell proliferation deficiency. The primary roots of mid1 and wild-type seedlings were first cut into segments of 0.5 cm in length, followed by 10 days culturing on Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium in the presence of 100 μg/L of 2,4-D and variable amounts of kinetin. As shown in Fig. S2A, callus from the wild-type plant proliferated rapidly at the indicated concentration of hormone, with a tendency that callus growing better following the increment of kinetin. In contrast, the proliferation of mid1 callus was less robust, even displaying growth repression at high concentration of kinetin. Similarly, the cotyledon explants of mid1 grew slowly compared to the wild-type (Fig. S2B). Collectively, we concluded that mutation of MID1 disrupts, most likely indirectly, the cell proliferation of diverse organs.

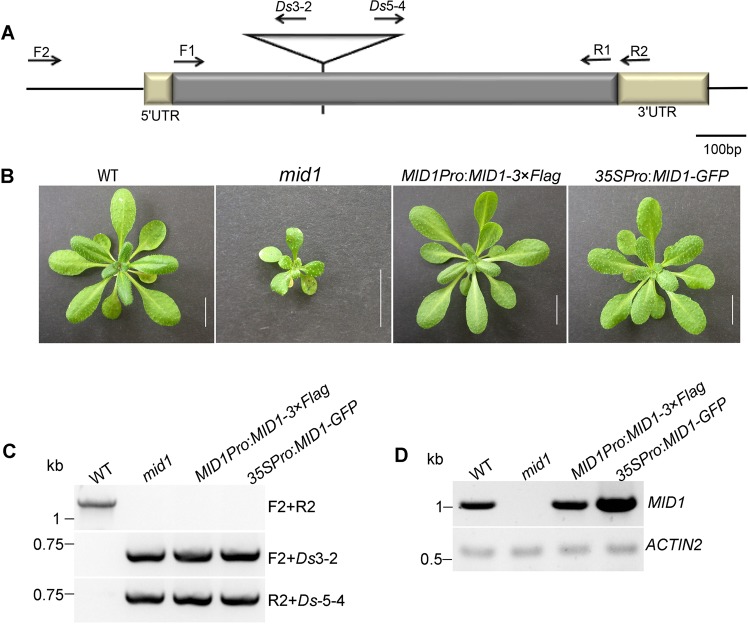

Molecular cloning of MID1

To clone the MID1 gene, thermal asymmetric interlaced PCR (TAIL-PCR) was employed to obtain the genomic sequence flanking the Ds element67. Sequence analysis indicated that the Ds was inserted into the At1g06270, at 342 bp downstream of ATG codon, generating 8 bp duplication at the insertion site (Fig. 3A). Meanwhile, we generate a CRISPR/Cas9-derived mid1 mutant in Col-0 background, where a single A was inserted at 106 bp, causing frameshift and further resulting in premature stop codon after 6 erroneous codons68 (Fig. S3A). This mutant was named mid1-2 while the mutant in Ler background was named mid1-1. Phenotype analysis clearly displayed mid1-2 was similar with mid1-1, such as retarded embryogenesis (Fig. S3B–E), small seed with intact embryo (Fig. S3F–I), and dwarfism at adult stage (Fig. 3J,K). The subsequent genetic and functional analysis mainly focus on mid1-1. The fragment containing the coding sequence of MID1 under the control of either its native promoter (1053 bps upstream of initial ATG codon) or cauliflower mosaic virus promoter (CaMV 35S) could complement the mutant phenotype of mid1-1 (Fig. 3B,C). Therefore, these findings demonstrate that the loss-function of MID1 is indeed the cause of the altered developmental phenotypes of mid1-1 plants. Besides, we failed to detect any MID1 transcripts in mid1-1 plants, suggesting that mid1-1 was a null allele mutant (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Cloning of MID1. (A) Diagram of mid1 mutant. The Ds insertion is pointed out by a triangle. The position of primers used in (C,D) are displayed by arrows. (B) The phenotype of 4-week-old wild-type (WT), mid1, and genetically complemented lines MID1Pro:MID1-3 × Flag and 35SPro:MID1-GFP. Bar = 1 cm. (C) Genotyping of plants in (B) using the primers indicated in (A). (D) RT-PCR detection of MID1 cDNA in plants (B) to confirm the successful complementation. The primers F1 and R1 were used to RT-PCR analysis of MID1.

MID1 contains an open reading frame of 1032 bp that encodes a 40 KD protein with 343 amino acid (aa) residues. Different PPR protein predictors identify different numbers of PPR motif in MID1. For example, plantPPR and TIGRFAM annotates four PPR motifs in MID1, while PROSITE annotates five PPR motifs69, and UNIPROT annotates six PPR motifs70. The discrepancy between these predictors arises from the position of first PPR motif. plantPPR annotates 136th–170th amino acids as the first PPR motif, TIGRFAM annotates 101th–135th amino acids as the first PPR motif19,71, We adopt the annotation from plantPPR due to that it is a recently developed tool that redefines the PPR motif and have more accurate and consistent annotations of PPR sequences19. As annotated from plantPPR database (http://www.plantppr.com)19, MID1 is a member of the P-type PPR family, containing four putative canonical PPR motifs between amino acid residue 136th and 311th. A BLAST search with MID1 protein sequence identified several orthologues from many eudicot plants (Fig. S4). Protein alignment showed that they share high similarity at protein level (Fig. S5). However, there is no close orthologues in monocots, indicating that MID1 is a novel P-type PPR protein unique to eudicots.

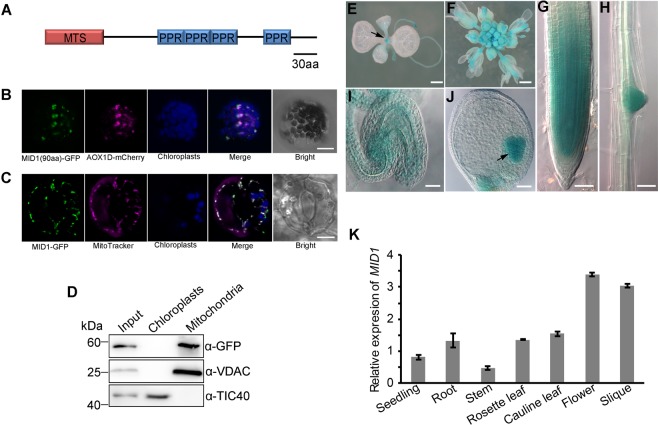

MID1 encodes a mitochondria-localized PPR protein

Both the Predotar and TargetP programs predicted that MID1 is a mitochondrial protein with the N-terminal 76 aa as a putative transit peptide targeted to mitochondrion72–74 (Fig. 4A). To determine its subcellular localization experimentally, the fusion containing the N-terminal of MID1 and GFP reporter was generated and transiently expressed in Arabidopsis protoplasts. Meanwhile, AOX1D, a mitochondria-localized alternative oxidase, was used as a mitochondrion marker. Confocal microscopy showed that the GFP signal was localized in mitochondria, but not in chloroplasts (Fig. 4B). Then we transferred 35SPro:MID1-GFP into mid1-1 mutant plants. The results showed that 35SPro:MID1-GFP fully complemented the mid1-1 mutation (Fig. 3B), suggesting that MID1-GFP was functional. We further checked the MID1 localization in the complemented plants. MID1-GFP was also localized in mitochondria as revealed by MitoTracker staining and there was no co-localization with chloroplasts (Fig. 4C). Besides, we separately extracted mitochondria and chloroplasts from the complemented lines, followed by Western blot detection. The result clearly showed that MID-GFP was enriched in mitochondria, not in chloroplasts (Fig. 4D). Together, these data confirm that MID1 encodes a mitochondria-localized protein.

Figure 4.

The subcellular localization and expression pattern of MID1. (A) Schematic structure of MID1. MTS, mitochondrial transient signal. (B) Subcellular localization of MID1-GFP in Arabidopsis protoplasts. Bar = 10 μm. (C) Subcellular localization of MID1-GFP in the stomata of 35SPro:MID1-GFP transgenic seedling. Bar = 5 μm. (D) Immunodetection of MID1-GFP localization. α-VDAC and α-TIC40 are mitochondrion and chloroplast-specific antibodies, respectively. (E–I) The expression pattern of MID1-GUS reporter. (E) seedling, arrow indicates shoot apex, (F) flower, (G) root meristem, (H) lateral root primordium, (I) unfertilized ovule and (J) ovule with heart embryo, arrow indicate the embryo. (E,F) Bars = 1 mm, (G–J), Bars = 50 μm. (K) Relative expression levels of MID1 mRNA in diverse tissues measured by qRT-PCR. The mean data are derived from triple independent biological replicates prepared from three parallel samples, and finally normalized with ACTIN2.

In order to get a better understanding about the function of MID1 during development, we next investigated its temporal and spatial expression. First, we constructed a MID1Pro:MID1-GUS fusion under the control of its own promoter, which was subsequently transformed into the mid1−1/+ plants. With the help of the double antibiotic selection, the transgenic lines containing both MID1Pro:MID1-GUS and mid1 were identified from the F3 progeny. In these plants, strong GUS signal was detected in multiple organs demanding for high cell proliferation activity, which include the shoot apex (Fig. 4E), flower (Fig. 4F), root meristem (Fig. 4G), lateral root primordium (Fig. 4H), unfertilized ovule (Fig. 4I) and embryo (Fig. 4J). By contrast, there was nearly no GUS activity in the cotyledon and root maturation region where the cell proliferation activity is low (Fig. 4E,H). In general, MID1 is preferentially expressed in tissues with active cell division. To corroborate the expression pattern of MID1, the quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) experiments were employed to detect the relative MID1 mRNA abundance in major organs of Arabidopsis. MID1 was ubiquitously expressed in the organs tested, with high expression in reproductive organs such as flower and silique (Fig. 4I,K), which were consistent with the GUS staining results.

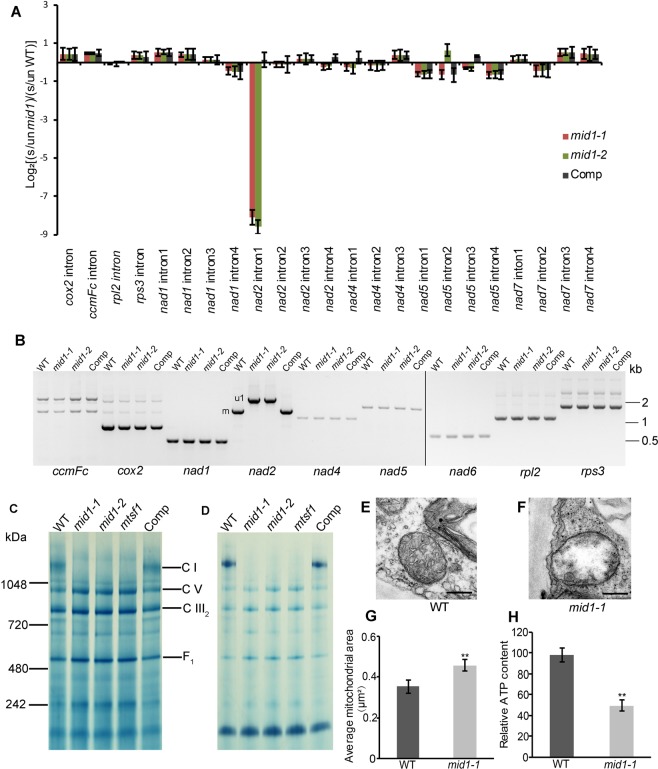

MID1 is required for the splicing of nad2 intron 1 and mitochondrial biogenesis

As we have noted, MID1 encodes a PPR protein belonging to P-type subfamily, many of which were shown to be involved in RNA splicing within organelles29,38–40. So, it is reasonable to speculate that MID1 is potentially involved in mitochondrial RNA splicing. Hence, we detected the splicing efficiency of 23 mitochondrial group II introns in 4-week-old wild-type, mid1-1,mid1-2 and complemented plants using qRT-PCR38,75. The results showed that the splicing efficiency of nad2 intron 1 is dramatically altered while there was no significant alternation in other introns, which suggest that mid1 is defective in the splicing of nad2 intron 1 (Fig. 5A). We further confirmed this RNA splicing deficiency by RT-PCR. First, as shown in Fig. 5B, the precursor nad2 RNA with the intron 1 accumulated in mid1 mutants, and the mature nad2 without intron 1 was restored in the complemented line. Second, consistent with the qRT-PCR analysis, there were no splicing differences between the wild-type and mid1 mutants regarding to other mitochondrial transcripts with introns. Furthermore, we also detected the editing status of nad2 in mid1 mutants to test whether MID1 is involved in nad2 editing. 31 C-U editing events were reported to take place in nad276, but only 27 editing sites were found in either WT mature nad2 or mid1 nad2 with intron 1 in our analysis. Among the identified editing sites, only a small proportion of nad2 280 C was changed to U (Fig. S6). Compared to the WT nad2 editing status, no editing sites were affected in mid1 mutants (Fig. S6). Taken together, mid1 is severely impaired in splicing of nad2 intron 1.

Figure 5.

Functional analysis of MID1 in mitochondria. (A) qRT-PCR analysis of splicing efficiency of mitochondrial introns in mid1. The histograms display the ratio of the spliced transcripts to the unspliced transcripts in mid1 plants as compared with wild-type in a log2 form. Each mean value is the average of three biological replicates, each of which undergoes triple repeats. s, spliced transcripts; un, unspliced transcripts. (B) RT-PCR analysis of mitochondrial transcripts splicing efficiency. u1 means nad2 transcript with intron 1.m means mature nad2 transcript. comp, MID1Pro:MID1-3 × Flag complemented line. (C) BN-PAGE analysis of mitochondrial protein complexes abundance in wild-type, mid1 mutants, mtsf-1 and complemented line. Protein marks are indicated in the left panel and the bands representing main protein complexes are listed in the right panel. (D) In-gel analysis of complex I activity in wild-type, mid1 mutants, mtsf1 and complemented line. comp, MID1Pro:MID1-3 × Flag complemented line. Transmission electron microscopy analysis of mitochondrial ultrastructure in leaf of 4-week-old WT (E) and mid1-1 (F). Bars = 0.5 μm. (G) Mitochondrial area of wild-type and mid1-1. Data are the mean ± SE, n = 140. Student’s t tests, *P < 0.05. (H) ATP content in the leaf of wild-type and mid1-1, Student’s t tests, **P < 0.01.

To investigate whether mitochondrial respiration complexes were affected, blue native gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) was performed. Complex I of mitochondrial respiration chain is a large protein complex consisting of more than 40 subunits encoded by both nuclear and mitochondrial genomes, among which mitochondrial genome-derived nad2 subunit localizes at the membrane arm of Complex I77. As the above results indicating that the splicing of nad2 first intron was deficient in mid1 mutants, we next investigated whether this failure of splicing affects Complex I. Meanwhile, a previously reported Complex I deficient mutant mtsf1 (Salk_086724) was used as a control78. Mitochondria were isolated from 4-week-old wild-type, mtsf1,mid1 mutants and the complemented plants, followed by BN-PAGE resolution and Coomassie staining, to detect the integrity and activity of Complex I. Distinct complexes can be distinguished according to the analogous separation results done before79. Similar to mtsf1, there was a remarkable reduction of Complex I abundance in mid1 mutants compared with the wild-type and the complemented plants, indicating that the integrity of Complex I was impaired in mid1 mutants (Fig. 5C). Consistently, further enzymatic detection showed that the activity of Complex I decreases dramatically in mid1 mutants (Fig. 5D). These results confirmed that the nad2 intron 1 splicing deficiency in mid1 further impairs the Complex I function.

To further investigate whether the mitochondrial function deficiency had effect on their morphology, we performed the transmission electron microscopy to check the ultrastructure of mitochondria in the fifth leaf of 4-week-old wild-type and mid1-1 plant. In the mesophyll cells, there were two striking morphological differences between wild-type and mid1-1. First, nearly 70% of mitochondria (n = 140) has altered cristae structural organization in mid1-1. Cristae was abundant and arranged regularly in the wild-type (Fig. 5E), but less abundant and disordered in mid1-1 (Fig. 5F). Second, mitochondrial size was swollen in mid1-1, about 1.3 times that of the wild-type (Fig. 5G). These findings indicate that loss-function of MID1 results in compromised mitochondrial ultrastructure.

As reported above, mitochondrial respiration Complex I was disrupted in mid1 mutants due to the failure of nad2 intron 1 splicing. The electron transport along the mitochondrial respiration complexes is the prerequisite for the establishment of proton gradient cross the inner membrane, which further ensures the successful generation of ATP80,81. Therefore, we reasoned that the impaired Complex I activity may influence the mitochondrial energy metabolism. To test this hypothesis, we measured the ATP content in the leaf of wild-type and mid1-1. The result showed that ATP content dramatically decreased in mid1-1 compared to the wild-type (Fig. 5H), consistent with the previous results that functional deficiency in Complex I impairs ATP production82,83. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are inevitable byproducts originally generated by excess electron transferred to O2, which ultimately give rise to H2O284,85. Previous studies have revealed that disruption of Complex I could bring about the accumulation of H2O254,86. To access whether mid1-1 produces more H2O2, we measured the H2O2 content through 3′, 3′- diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining, which clearly showed that more H2O2 accumulated in mid1-1, especially in the vascular tissue (Fig. S7A,B), Consistently, subsequent quantitative assay indicates that H2O2 in mid1-1 was 1.5 times more than that of the wild-type (Fig. S7C). Together, these results suggest that the malfunctional mitochondrion caused by MID1 mutation further lead to production of less ATP and more H2O2 than the wild-type.

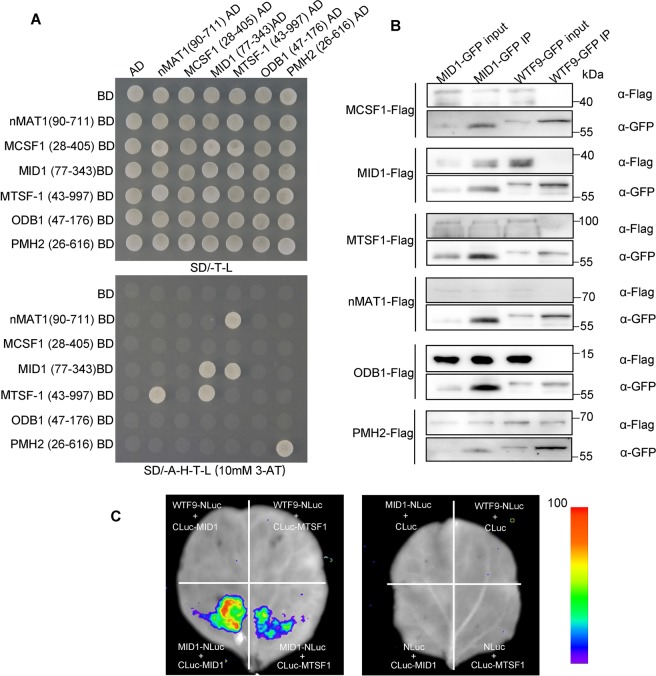

MID1 is associated with other trans-factors involved in nad2 intron 1 splicing

Group II intron, first found in fungi and plant organelle genomes, is a self-splicing ribozyme that catalyzes auto-excision in vitro, but it requires the assistance of trans-factors to fulfill this process in vivo87–89. As previously reported, there are five trans-factors also involved in the splicing of the nad2 intron 1 in Arabidopsis, including MITOCHONDRIAL CAF-LIKE SPLICING FACTOR 1 (MCSF1), MTSF1, nMAT1, ORGANELLAR DNA-BINDING PROTEIN 1 (ODB1) and PUTATIVE MITOCHONDRIAL RNA HELICASE 2 (PMH2)55,59,78,90,91. We reasoned if MID1 may work together with these trans-factors to promote nad2 intron 1 splicing. In order to explore this possibility, we first examined their interaction relationship by yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) assay. As shown in Fig. 6A, MID1 could interact with MTSF1 and itself in yeast. Meanwhile, we also detected that nMAT1 can interact with MTSF1, and PMH2 itself can form homodimer. Next, we performed Coimmunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assays in Arabidopsis protoplasts to investigate whether they are in the same complex to control nad2 intron1 splicing. MID1-GFP is transiently co-expressed with each Flag-tagged trans-factor in the Arabidopsis protoplasts. WHAT’S THIS FACTOR 9(WTF9), a mitochondria-localized protein involved in ccmFc and rpl2 introns splicing92, was fused with GFP to act as the negative control. As shown in Fig. 6B, all the trans-factors tagged with Flag could be successfully pulled down by the MID1-GFP, while WTF9-GFP failed to pull down the target proteins including MCSF1, MID1, MTSF1, nMAT1 and ODB1. WTF9 can pull down PMH2 because they are involved in splicing of rpl2 intron 193, which indicates that they work together to promote intron splicing. Together, WTF9 IP control results point that MID1 interact specifically with other trans-factors, however we can’t exclude the possibility that RNA may facilitate their interactions. In order to further confirm the interaction between MID1, MTSF1 and itself, we performed firefly luciferase complementation imaging assay in tobacco leaves94, in which WTF9 acted as the negative control. As shown in Fig. 6C, while no LUC activity was found in the combination of WTF9-NLuc/CLuc-MID1, WTF9-NLuc/CLuc-MTSF1, both the combination of MID1-NLuc/CLuc-MTSF1 and MID1-NLuc/CLuc-MID1 showed Luc activity, indicating that MID1 can interact with MTSF1 and itself in tobacco. Although MID1 has association with all the other trans-factors, only few of them have direct physical interactions, which can be ascribed to additional uncharacterized trans-factor or RNA that can mediate the physical interaction between these trans-factors. When we finished the interaction assays, another PLS-type PPR protein SLO4 was reported to influence nad2 intron 1 splicing50, it is worthy to test its interaction relationship with other trans-factors.

Figure 6.

MID1 is associated with other trans-factors involved in nad2 intron 1 splicing. (A) Y2H analysis of interaction relationship between trans-factors involved in nad2 intron 1 splicing. The upper panel displays the yeast that can grow on the SD/-Trp-Leu (SD/-T-L) dropout media. The lower panel displays the yeast growing on the SD/-Ade-His-Trp-Leu (SD/-A-H-T-L) dropout media, which indicates the physical interaction of two trans-factors. 10 mM 3-amino-1, 2, 4-triazole (3-AT) is added in the media to inhibit the autoactivation of MTSF1(43–997aa) BD + AD and BD + ODB1(47–176aa) + AD. (B) Co-IP analysis of trans-factors association in Arabidopsis protoplast. About 70 μg total proteins were loaded in the input lanes and one sixth volume of GFP beads were loaded in the IP lanes. Protein mark is on right side of immunoblot. (C) Luciferase complementation assay of interaction between MID1, MTSF1 and itself. The pseudocolor bar indicates the relative luminescence intensity in the image.

MTSF1 is a mitochondria-localized large PPR protein with 19 PPR motifs which positively regulate the stability of nad4 mRNA and nad2 intron 1 splicing78. Regarding that MID1 can interact with MTSF1, it is reasonable to infer that MID1 may also be involved in nad4 mRNA stability. No nad4 mRNA was detected in mtsf1 mutants in the previous report. However, the abundance of nad4 mRNA in mid1 mutants was similar to that of wild-type (Fig. 5B). Thus, our results suggest that MID1 is not involved in nad4 mRNA stability and the interaction between MID1 and MTSF1 mainly functions in the splicing of nad2 intron 1.

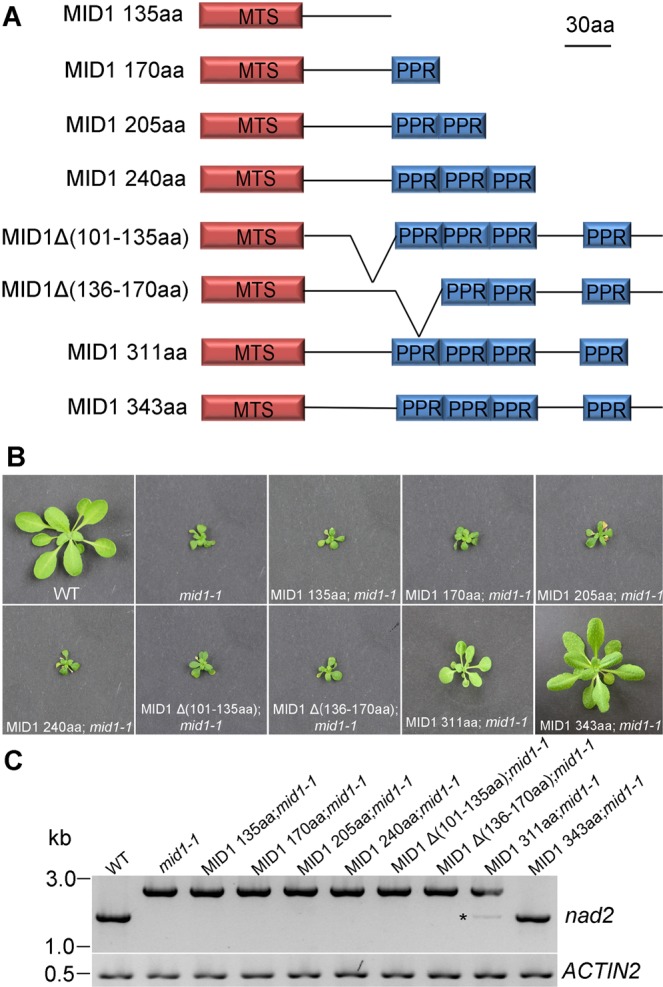

The N-Terminal (77–135aa) and the PPR motifs are important for nad2 intron 1 splicing and plant development

In order to identify the domain responsible for MID1 dimerization, a variety of truncation and fusions lack of different domains of MID1 were constructed and tested in yeast. The MID-BD variants with the first PPR motif (136–170aa), which include MID1(77–170aa)BD, MID1(77–205aa)BD, MID1(77–240aa)BD, MID1(77–276aa)BD, MID1(77–311aa)BD, MID1(77–343aa)BD and MID1(136–170aa) BD were able to interact with MID1(77–343)AD, whereas MID1 variant only containing the N-terminus, MID1(77–135)BD, failed to interact with MID1(77–343)AD. Furthermore, first PPR motif itself, MID1(136–170) BD can interact with MID1 variants that include MID1(77–170aa)AD, MID1(77–205aa)AD, MID1(77–240aa)AD, MID1(77–276aa)AD, MID1(77–311aa)AD and MID1(77–343aa)AD, while MID1(136–170)BD can’t interact with MID1(136–170)AD (Fig. S9a). These results showed that the first PPR domain mediates the dimerization and the N-terminus facilitate the homodimer formation.

We further characterized the role of each domain in MID1 in RNA splicing and plant development. To explore this, a variety of MID1 variants were constructed, which include MID1(135aa), MID1(170aa), MID1(205aa), MID1(240aa), MID1Δ(101–135aa), MID1Δ(136–170aa), MID1 (311aa) and full-length MID1(343aa) (Fig. 7A). These variants, driven by 35S promoter and fused with GFP at its C-terminus, were subsequently transformed to the mid1-1/+ plants for genetic complementation. As shown in Fig. 7B, neither MID1 variants lack the N-terminus (101–135aa) nor were the ones lacking PPR motif able to rescue mid1-1 growth phenotype, indicating that the N-terminus and PPR motifs are essential for MID1 function in plant development. On the other hand, the full-length of MID1 could completely rescue mid1-1 and the MID1 variant without the C-terminus (312–343aa) partially rescue mid1-1, indicating that the C-terminus (312–343aa) plays a less important role during plant development. Consistently, the splicing efficiency of nad2 intron 1 correlated with the complementation level (Fig. 7C). While the MID1 variant without the C-terminus (312–343aa) could partially restore the splicing efficiency of nad2 intron 1, there was no alternation of splicing efficiency in the transgenic plant with the other MID1 variants lacking the N-terminus or a PPR motif, suggesting that the N-terminus and the PPR motifs are necessary for nad2 intron 1 splicing.

Figure 7.

Functional analysis of each domain of MID1. (A) Schematic diagram of MID1 variants. (B) The phenotypes of mid1-1 complemented by MID1 variants. Bar = 1 cm. (C) RT-PCR analysis of splicing efficiency of nad2 intron 1 in mid1-1 complemented by MID1 variants. ACTIN2 is used as loading control.

Discussion

Here, we isolated an embryo-defective mutant mid1 which displays growth defects during the whole plant life cycle. MID1 encodes a mitochondria-localized short P-type PPR protein essential for the correct splicing of the first intron of nad2, mutation of which disrupts the assembly of mitochondrial respiration Complex I and the ultrastructure of mitochondria. Furthermore, MID1 is found to be associated with other trans-factors, among which MID1 can interact with itself and MTSF1 to form homodimer and heterodimer, respectively. The genetic complementation further confirms that the N-terminus and each PPR motif are required for nad2 intron 1 splicing and plant development. In summary, MID1 is a novel short P-type PPR protein required for nad2 intron 1 splicing, mitochondrial biogenesis and plant development.

MID1 plays roles in RNA splicing likely in a dimeric fashion

In contrast to most PPR proteins involved in RNA splicing which are usually long in protein length and harbor more than ten PPR motifs, MID1 is a short P-type PPR protein with only four canonical PPR motifs, similar to another well characterized short PPR protein THA829. THA8 is a chloroplasts-localized PPR protein required for the efficient splicing of ycf3-2 and tRNA introns. In vitro biochemical experiments have validated that THA8 orthologues can bind ycf3-2 intron through multiple purine-rich sequences distributing in intron30. More importantly, the crystal structure analysis of THA8 and THA8-RNA reveals that RNA targets can induce THA8 to form dimer and oligomer which will fold the linearized intron RNA into a condensed tertiary structure that can be easily bound by other splicing factors21,30. Similarly, in our yeast assays, we found that the MID1 can form dimer, in which the first PPR motif of MID1 directly mediate the dimerization and the N-terminus (77–135aa) can facilitate this formation process. It seems that some PPR proteins fulfill their distinctive functions in a dimer manner. How the N-terminus exert effects on the dimerization is still unknown. Experimental identification of RNA targets of MID1 and resolution of MID1/MID1-RNA crystal structure in the further will elucidate the action mode of MID1 in detail. PPR10 is one of the best characterized PPR proteins, but its action mode is still uncertain. The dispute about whether PPR10 works as dimer or monomer may originate from that they use different strategies to study PPR1024,35. It is worthy to figure out its real physiological state in vivo. In addition, it seems that there is no common manner adopted by all PPR proteins to perform function. While some PPR proteins work as dimer28,30, some others work as monomer31,32.

MID1 indirectly affects cell expansion and proliferation

mid1 displays growth retardation and dwarfism phenotypes during the whole plant life cycle, which can be ascribed to its impaired cell expansion and proliferation. The limited production of ATP caused by abnormal mitochondrial biogenesis may be in part responsible for these cellular defects. In mammals, AMP-ACTIVATED PROTEIN KINASE (AMPK) is widely considered to be the cellular energy sensor which can be activated by nutrient stress to maintain energy homeostasis95. One of these cellular effects exerted by AMPK in energy-deficient cell is to arrest cell cycle through phosphorylation p53 and transcriptional activation of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (CDKN1A)96. SUCROSE NON-FERMENTING 1 PROTEIN (SNF1)-RELATED PROTEIN KINASE 1 (SNRK1), the atypical AMPK orthologue in Arabidopsis, has been shown to participate in ABA and sugar signaling97,98, whether it is also involved in the regulation of cellular stress response induced by dysfunctional mitochondrion remains elusive. Alternatively, there are evidences that many other signaling pathways such as ABA, Auxin and GA signaling may act downstream of compromised mitochondrion to convey the energy shortage information54,86,99. Thus, it seems that the abnormal hormone signaling may commonly underlie the cellular deficiency of PPR mutants, which may be further responsible for their mutant phenotypes. Besides, great advances have been made in understanding the plant mitochondrial retrograde signaling in the past decade. For example, many important transcription factors downstream of mitochondrial retrograde signaling have been identified through forward and reverse genetic study, such as ABIA INSENSITIVE 4 (ABI4), WRKY40, WRKY63, NO APICAL MERISTEM/ARABIDOPSIS TRANSCRIPTION ACTIVATION FACTOR/CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON (ANAC013), ANAC017 and MYB DOMAIN PROTEIN 29, which positively or negatively regulate nuclear genes expression upon mitochondrial stress100–104. It will be interesting to genetically evaluate whether they contribute to the mutant phenotypes caused by MID1 disruption.

In conclusion, we characterized a mitochondria-localized PPR protein MID1 which is required for the mitochondrial RNA splicing and Arabidopsis development. The association of trans-factors involved in nad2 intron 1 splicing will lay the foundation for further structural resolution of the mitochondrial RNA splicing apparatus by means of single-particle cryogenic electron microscopy which has successfully resolve the three-dimensional structure of yeast spliceosome at near atom level105. Finally, the mitochondrial retrograde signaling may contribute a lot to the abnormal morphology of mid1, thus mid1 is a candidate mutant that is instrumental to discover the novel components involved in the mitochondrial retrograde signaling in a genetic manner.

Plant materials and growth conditions

Both Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Landsberg erecta (Ler) and Columbia-0 (Col-0) were used as wild-type here. mid1-1(Ds insertion line) was in Ler background while the cell proliferation reporter line CYCB1;1-GUS, mtsf1 (SALK_086724) and mid1-2 (CRISPR/Cas9-derived mutant) was in Col-0 background. CYCB1;1-GUS reporter used in this study was as previously described64. SALK_086724 was obtained from ABRC stock center. mid1-2 was a CRISPR/Cas9-derived mutant. Seeds sterilization and genetic transformation were performed as previously reported53,54. The plants were grown in the air-conditioned house (22 °C) under a 12 h light/12 dark cycle.

Phenotypic analysis

To investigate the embryogenesis phenotype, siliques of mid1/+ plants were dissected with hypodermic needles and cleared in Herr’s solution106. The cleared ovules were subsequently observed with Zeiss Axioskop II microscope equipped with differential interference contrast optics. Measurement of cell size of leaf and root was performed as reported57.

Molecular cloning and genetic complementation

Thermal asymmetric interlaced PCR was performed to identify MID1 that is disrupted by Ds insertion. To complement the mid1-1 mutant, the 35S promoter and the NOS terminator sequences were cloned into pCAMBIA1300 to generate pCAM1300-35SPro-NOS. Then, we amplify the GFP,GUS and 3 × Flag sequence and inserted them into pCAM1300-35SPro-NOS to produce pCAM1300-35SPro:GFP-NOS, pCAM1300-35SPro:GUS-NOS and pCAM1300-35SPro:3 × Flag-NOS, respectively. To produce MIDPro:MID1-GUS and MIDPro:MID1-3 × Flag, 35S promoter was cut from pCAM1300-35SPro:GFP-NOS and pCAM1300-35SPro: GUS-NOS by restriction enzymes digestion. The MID1 promoter and MID1 coding sequence were amplified with gene specific primers in Supplemental Table and simultaneously inserted into pCAM1300-GUS-NOS and pCAM1300-3 × Flag-NOS through in-fusion clone (638933, Takara). To produce the 35SPro:MID1 variants-GFP, the full-length MID1 and the truncated MID1 coding sequence were amplified with specific primers in Supplemental Table and were introduced into pCAM1300-35SPro:GFP-NOS. All the constructs were transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101, which were then introduced into mid1-1/+ plant through A. tumefaciens-mediated floral dip transformation107.

Microscopy

For GUS assay, various organs or the whole seedling of MID1Pro:MID1-GUS complementation lines were immersed in GUS staining solution as reported previously54. For confocal microscopy, 6-day-old seedlings of 35SPro:MID1-GFP complementation lines were stained with 500 nM MitoTracker® Red CMXRos (M7512, Invitrogen/Molecular Probes) for 5 min, followed by washing three times using the half-strength MS liquid medium. The stained cotyledons were observed with a 488 nm and 543 nm laser of a Zeiss CLSM laser scanning microscope. Transmission electron microcopy was performed as previously reported108.

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA from various organs were extracted using the plant RNeasy mini-kit (74104, Qiagen). First-strand cDNA was then synthesized from 1–5 μg of RNA using the superscript III reverse transcriptase (18080093, Thermo Fisher) with the oligo-dT primer according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For qRT-PCR analysis, the primers used to amplify MID1 were designed by Beacon Designer 8 software while primers for analysis of splicing ratio of mitochondrial RNA transcripts was performed as described previously39. qRT-PCR was performed with SYBR Green SuperReal PreMix Plus (FP205, TIANGEN) on the Bio-Rad C1000 Thermal Cycler.

Mitochondrion and chloroplast isolation

Mitochondria isolation was performed according to the previously reported protocol with minor modification109. A total of 20 g soil grown Arabidopsis plants were ground in pre-cold grinding solution [300 mM sucrose, 10 mM KH2PO4 (PH7.5), 25 mM Na4P2O7, 1 mM EDTA, 1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA), 1% [w/v] PVP40, 10 mM cysteine, 1 mM DTT and 1x proteinase inhibitor cocktail]. Tissue homogenate was further broken by Teflon homogenizer at 100 rpm–150 rpm. The resulting cell debris were filtered through two layers of miracloth (473855, Millipore) and separated at 3000 g for 5 min at 4 °C to remove the nucleus. The supernatants were further subject to centrifugation at 15000 g for 30 min to obtain the crude organelle pellets which were subsequently recovered by washing buffer (300 mM sucrose, 10 mM MOPS, 1 mM EGTA). Repeating the differential centrifugation described above. The final suspended homogenate was carefully layered on the discontinuous Percoll (P1644, Sigma) density gradients comprised of 18%, 26%, 50% Percoll (1:5:1, v/v). After centrifugation at 40000 g for 45 min, mitochondria were collected from the interface of 26%/50% and washed three times using washing buffer to eliminate the Percoll. The purified mitochondrial protein concentration was analyzed by Branford protocol and can be directly frozen at −80 °C for the future use.

The isolation of chloroplast was performed according to the previously described protocol with some modifications110. Arabidopsis leaves were homogenized in isolation buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.8, 330 mM sorbitol, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 10 mM Na2CO3, 0.1% (w/v) BSA and 50 mM ascorbate [freshly added]) with 1× protease inhibitor cocktail. The homogenate was filtered through two layers of Miracloth (475855, Millipore) and then centrifuged for 5 mins at 2000 g. The collected crude chloroplasts were resuspended in 500 μL separation buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.8, and 330 mM sorbitol) and laid on the 40%/70% Percoll gradient. After centrifugation for 5 mins at 1500 g, the intact chloroplasts were collected between 40% and 70% Percoll gradient and washed twice with the separation buffer. The purified chloroplasts can be stored at −80 °C for further use.

Blue native page and immunodetection

About 100 μg extracted mitochondria were solubilized in cold NativePAGE Sample Buffer (BN2003, ThermoFisher) containing 1% dodecilmaltoside (DDM) according to the manufacture’s instruction. The mitochondrial protein complexes were separated using the 4–16% NativePAGE Bis-Tris Gel (BN1002BOX, Thermo Fisher) which was further used for Coomassie brilliant blue staining, the Complex I activity assay or transferred to PVDF membrane for immunodetection. Coomassie brilliant blue staining and immunodetection were performed according to the manufacturer’s instruction. In-gel detection of Complex I activity was performed according to the protocol described before111.

Y2H assay

The coding sequence of MCSF1, MID1 variants, MTSF1, nMAT1, ODB1 and PMH2, without the N terminal mitochondrial targeting signals, were cloned to the bait vector pGBKT7 and prey vector pGADT7 (Clontech), respectively. The primers are listed in Supplemental Table. Yeast transformation was carried out according to the protocol described in the manual’s instruction (Clontech). In the detection of some protein interaction pairs, 3-AT was added to prevent their auto-activations.

Protoplast transformation and Co-IP

The full-length MID1 and WTF9 coding sequences were cloned into pBluecript II SK(+)35Pro:GFP and the full length MCSF1, MID1, MTSF1, nMAT1, ODB1 and PMH2, were cloned into pBluecript II SK(+)35SPro:3 × Flag112. Tags were localized at C-terminal of genes. Arabidopsis protoplast was prepared from 3~4 weeks old plants growing in the12 h light/12 h dark condition. The subsequent plasmids transformation was performed according to the method described previously113. For Co-IP assay, total protein was extracted with extraction buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP40, 1 mM DTT, 1 × proteinase inhibitor cocktail). The pre-equilibrated GFP Trap beads (gta-10, Chromotek) incubates with protein extracts overnight at 4 °C. The GFP Trap beads were washed five times with washing buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% NP40, 1 mM DTT, 1 × proteinase inhibitor cocktail). Resuspend the GFP beads with a small volume of washing buffer, followed by boiling them for 5 mins. The eluted protein was ready for SDS page separation and immune-blot assay using the anti-GFP (M20004M, Abmart) and anti-Flag (F1804, Sigma).

Firefly luciferase complementation imaging assay

The corresponding sequences of MID1 and WTF9 were inserted into pCAMBIA-NLuc to produce MID1-NLuc and WTF9-NLuc. The corresponding sequences of MID1 and MTSF1 were inserted into pCAMBIA-CLuc to generate CLuc-MID1 and CLuc-MTSF1. Agrobacterium-mediated infiltration of N. benthamiana leaves was performed as described94. Infiltrated leaves were incubated at 22 °C for 72 h before CCD imaging.

ATP and H2O2 assay

ATP content was measured as described earlier83. The detection of H2O2 was performed as reported previously114. Leaves of wild-type and mid1-1 were subject to quantitative measurement of H2O2 using the Amplex® Red Hydrogen Peroxide/Peroxidase Assay Kit (A22188, Invitrogen). The assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

Accession numbers

Sequence data can be found in the Arabidopsis Genome Initiative database or the GenBank/EMBL data library under the following accession numbers: ACTIN2 (At3g18780), MCSF1 (At4g31010), MTSF1 (At1g06710), MID1 (At1g06270), nMAT1 (At1g30010), ODB1 (At1g71310), PMH2 (At3g22330) and WTF9 (At2g39120).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We appreciate Drs. Chuan-You Li and Lin Yang (Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences) for providing the CYCB1;1-GUS seed and assistance in transmission electron microcopy, respectively. This work was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (31570320).

Author contributions

P.Z., F.W. and W.C.Y. designed the project. F.W., N.L. and D.Q.S. performed the initial mutant screen. P.Z. performed most of experiments. P.Z. and W.C.Y. analyzed the data and wrote the article.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Peng Zhao and Fang Wang.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-58495-5.

References

- 1.Gray MW, Burger G, Lang BF. The origin and early evolution of mitochondria. Genome Biol. 2001;2:REVIEWS1018. doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-6-reviews1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McBride HM, Neuspiel M, Wasiak S. Mitochondria: more than just a powerhouse. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:551–560. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carlsson J, Leino M, Sohlberg J, Sundström JF, Glimelius K. Mitochondrial regulation of flower development. Mitochondrion. 2008;8:74–86. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heazlewood JL, et al. Experimental analysis of the Arabidopsis mitochondrial proteome highlights signaling and regulatory components, provides assessment of targeting prediction programs, and indicates plant-specific mitochondrial proteins. Plant cell. 2004;16:241–256. doi: 10.1105/tpc.016055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Millar AH, Heazlewood JL, Kristensen BK, Braun HP, Moller IM. The plant mitochondrial proteome. Trend Plant. Sci. 2005;10:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winger AM, Taylor NL, Heazlewood JL, Day DA, Millar AH. Identification of intra- and intermolecular disulphide bonding in the plant mitochondrial proteome by diagonal gel electrophoresis. Proteomics. 2007;7:4158–41570. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richardson, A. O., Rice, D. W., Young, G. J., Alverson, A. J. & Palmer, J. D. The “fossilized” mitochondrial genome of Liriodendron tulipifera: ancestral gene content and order, ancestral editing sites, and extraordinarily low mutation rate. BMC Biol. 11 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Liu Z, Butow RA. Mitochondrial retrograde signaling. Annu. Rev. Genetics. 2006;40:159–185. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.40.110405.090613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rhoads DM, Subbaiah CC. Mitochondrial retrograde regulation in plants. Mitochondrion. 2007;7:177–194. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakamura T, Yagi Y, Kobayashi K. Mechanistic insight into pentatricopeptide repeat proteins as sequence-specific RNA-binding proteins for organellar RNAs in plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 2012;53:1171–1179. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcs069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barkan A, Small I. Pentatricopeptide repeat proteins in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 2014;65:415–442. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-040159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hammani K, Giege P. RNA metabolism in plant mitochondria. Trend Plant. Sci. 2014;19:380–389. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nawaz G, Kang H. Chloroplast or mitochondria targeted DEAD-Box RNA helicases play essential roles in organellar RNA metabolism and abiotic stress responses. Front. Plant. Sci. 2017;8:871. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee K, Kang H. Emerging roles of RNA-binding proteins in plant growth, development, and stress responses. Mol. Cell. 2016;39:179–185. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2016.2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Small ID, Peeters N. The PPR motif - a TPR-related motif prevalent in plant organellar proteins. Trend Biochem. Sci. 2000;25:46–47. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(99)01520-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aubourg S, Boudet N, Kreis M, Lecharny A. In Arabidopsis thaliana, 1% of the genome codes for a novel protein family unique to plants. Plant. Mol. Biol. 2000;42:603–613. doi: 10.1023/A:1006352315928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lurin C, et al. Genome-wide analysis of Arabidopsis pentatricopeptide repeat proteins reveals their essential role in organelle biogenesis. Plant Cell. 2004;16:2089–2103. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.022236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Toole N, et al. On the expansion of the pentatricopeptide repeat gene family in plants. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2008;25:1120–1128. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng S, et al. Redefining the structural motifs that determine RNA binding and RNA editing by pentatricopeptide repeat proteins in land plants. Plant J. 2016;85:532–547. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barkan A, et al. A combinatorial amino acid code for RNA recognition by pentatricopeptide repeat proteins. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002910. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ban T, et al. Structure of a PLS-class pentatricopeptide repeat protein provides insights into mechanism of RNA recognition. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:31540–31548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.496828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takenaka M, Zehrmann A, Brennicke A, Graichen K. Improved computational target site prediction for pentatricopeptide repeat RNA editing factors. PLoS one. 2013;8:e65343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yagi Y, Hayashi S, Kobayashi K, Hirayama T, Nakamura T. Elucidation of the RNA recognition code for pentatricopeptide repeat proteins involved in organelle RNA editing in plants. PLoS one. 2013;8:e57286. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yin P, et al. Structural basis for the modular recognition of single-stranded RNA by PPR proteins. Nature. 2013;504:168–171. doi: 10.1038/nature12651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kindgren P, Yap A, Bond CS, Small I. Predictable alteration of sequence recognition by RNA editing factors from Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2015;27:403–416. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.134189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shen C, et al. Specific RNA recognition by designer pentatricopeptide repeat protein. Mol. Plant. 2015;8:667–670. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Filipovska A, Rackham O. Modular recognition of nucleic acids by PUF, TALE and PPR proteins. Mol. Biosyst. 2012;8:699–708. doi: 10.1039/c2mb05392f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meierhoff K. HCF152, an arabidopsis RNA binding pentatricopeptide repeat protein involved in the processing of chloroplast psbB-psbT-psbH-petB-petD RNAs. Plant Cell. 2003;15:1480–1495. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khrouchtchova A, Monde RA, Barkan A. A short PPR protein required for the splicing of specific group II introns in angiosperm chloroplasts. RNA. 2012;18:1197–1209. doi: 10.1261/rna.032623.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ke J, et al. Structural basis for RNA recognition by a dimeric PPR-protein complex. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013;20:1377–1382. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beick S, Schmitz-Linneweber C, Williams-Carrier R, Jensen B, Barkan A. The pentatricopeptide repeat protein PPR5 stabilizes a specific tRNA precursor in maize chloroplasts. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;28:5337–5347. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00563-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schmitz-Linneweber C, et al. A pentatricopeptide repeat protein facilitates the trans-splicing of the maize chloroplast rps12 pre-mRNA. Plant Cell. 2006;18:2650–2663. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.046110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pfalz J, Bayraktar OA, Prikryl J, Barkan A. Site-specific binding of a PPR protein defines and stabilizes 5′ and 3′ mRNA termini in chloroplasts. EMBO J. 2009;28:2042–2052. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Q, et al. Examination of the dimerization states of the single-stranded RNA recognition protein pentatricopeptide repeat 10 (PPR10) J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:31503–31512. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.575472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gully BS, et al. The solution structure of the pentatricopeptide repeat protein PPR10 upon binding atpH RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:1918–1926. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reddy AS. Alternative splicing of pre-messenger RNAs in plants in the genomic era. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 2007;58:267–294. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.58.032806.103754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wahl MC, Will CL, Luhrmann R. The spliceosome: design principles of a dynamic RNP machine. Cell. 2009;136:701–718. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Longevialle AF, et al. The pentatricopeptide repeat gene OTP43 is required for trans-splicing of the mitochondrial nad1 Intron 1 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2007;19:3256–3265. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.054841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koprivova A, et al. Identification of a pentatricopeptide repeat protein implicated in splicing of intron 1 of mitochondrial nad7 transcripts. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:32192–32199. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.147603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu Y, et al. ABA overly-sensitive 5 (ABO5), encoding a pentatricopeptide repeat protein required for cis-splicing of mitochondrial nad2 intron 3, is involved in the abscisic acid response in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2010;63:749–765. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chateigner-Boutin AL, et al. OTP70 is a pentatricopeptide repeat protein of the E subgroup involved in splicing of the plastid transcript rpoC1. Plant J. 2011;65:532–542. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.des Francs-Small CC, et al. The Pentatricopeptide Repeat Proteins TANG2 and ORGANELLE TRANSCRIPT PROCESSING439 are involved in the splicing of the multipartite nad5 transcript encoding a subunit of mitochondrial Complex I. Plant Physiol. 2014;165:1409–1416. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.244616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haili N, et al. The MTL1 pentatricopeptide repeat protein is required for both translation and splicing of the mitochondrial NADH DEHYDROGENASE SUBUNIT7 mRNA in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2016;170:354–366. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.01591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xiu Zhihui, Sun Feng, Shen Yun, Zhang Xiaoyan, Jiang Ruicheng, Bonnard Géraldine, Zhang Jianhua, Tan Bao-Cai. EMPTY PERICARP16 is required for mitochondrialnad2intron 4cis-splicing, complex I assembly and seed development in maize. The Plant Journal. 2016;85(4):507–519. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang C, Aube F, Quadrado M, Dargel-Graffin C, Mireau H. Three new pentatricopeptide repeat proteins facilitate the splicing of mitochondrial transcripts and complex I biogenesis in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2018;69:5131–5140. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ery275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cai M, et al. EMP10 encodes a mitochondrial PPR protein that affects the cis-splicing of nad2 intron 1 and seed development in maize. Plant J. 2017;91:132–144. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen X, et al. DEK35 encodes a ppr protein that affects cis-splicing of mitochondrial nad4 intron 1 and seed development in Maize. Mol. Plant. 2017;10:427–441. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2016.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qi W, Yang Y, Feng X, Zhang M, Song R. Mitochondrial function and maize kernel development requires DEK2, a pentatricopeptide repeat protein involved in nad1 mRNA Splicing. Genetics. 2017;205:239–249. doi: 10.1534/genetics.116.196105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ren X, et al. EMPTY PERICARP11 serves as a factor for splicing of mitochondrial nad1 intron and is required to ensure proper seed development in maize. J. Exp. Bot. 2017;68:4571–4581. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erx212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weissenberger S, Soll J, Carrie C. The PPR protein SLOW GROWTH 4 is involved in editing of nad4 and affects the splicing of nad2 intron 1. Plant. Mol. Biol. 2017;93:355–368. doi: 10.1007/s11103-016-0566-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ichinose M, Tasaki E, Sugita C, Sugita M. A PPR-DYW protein is required for splicing of a groupII intron of cox1 pre-mRNA in Physcomitrella patens. Plant J. 2012;70:271–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Longevialle AF, Small ID, Lurin C. Nuclearly encoded splicing factors implicated in RNA splicing in higher plant organelles. Mol. Plant. 2010;3:691–705. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssq025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kuhn K, et al. The RCC1 family protein RUG3 is required for splicing of nad2 and complex I biogenesis in mitochondria of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2011;67:1067–1080. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.He J, et al. DEXH box RNA helicase-mediated mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production in Arabidopsis mediates crosstalk between abscisic acid and auxin signaling. Plant Cell. 2012;24:1815–1833. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.098707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zmudjak M, et al. mCSF1, a nucleus-encoded CRM protein required for the processing of many mitochondrial introns, is involved in the biogenesis of respiratory Complexes I and IV in Arabidopsis. New. Phytol. 2013;199:379–394. doi: 10.1111/nph.12282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brown GG, Colas des Francs-Small C, Ostersetzer-Biran O. Group II intron splicing factors in plant mitochondria. Front. Plant. Sci. 2014;5:35. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hammani K, Barkan A. An mTERF domain protein functions in group II intron splicing in maize chloroplasts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:5033–5042. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hsu YW, Wang HJ, Hsieh MH, Hsieh HL, Jauh GY. Arabidopsis mTERF15 is required for mitochondrial nad2 intron 3 splicing and functional complex I activity. PLoS one. 2014;9:e112360. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gualberto JM, Le Ret M, Beator B, Kuhn K. The RAD52-like protein ODB1 is required for the efficient excision of two mitochondrial introns spliced via first-step hydrolysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:6500–6510. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ding YH, Liu NY, Tang ZS, Liu J, Yang WC. Arabidopsis GLUTAMINE-RICH PROTEIN23 is essential for early embryogenesis and encodes a novel nuclear PPR motif protein that interacts with RNA polymerase II subunit III. Plant Cell. 2006;18:815–830. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.039495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu M, et al. GAMETOPHYTIC FACTOR 1, involved in pre-mRNA splicing, is essential for megagametogenesis and embryogenesis in. Arabidopsis. J. Integr. Plant. Biol. 2009;51:261–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008.00783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Page DR, Grossniklaus U. The art and design of genetic screens: Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2002;3:124–136. doi: 10.1038/nrg730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li Y, Zheng L, Corke F, Smith C, Bevan MW. Control of final seed and organ size by the DA1 gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genes. Dev. 2008;22:1331–1336. doi: 10.1101/gad.463608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Colon-Carmona A, You R, Haimovitch-Gal T, Doerner P. Technical advance: spatio-temporal analysis of mitotic activity with a labile cyclin-GUS fusion protein. Plant J. 1999;20:503–508. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Casamitjana-Martinez E, et al. Root-specific CLE19 overexpression and the sol1/2 suppressors implicate a CLV-like pathway in the control of Arabidopsis root meristem maintenance. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:1435–1441. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00533-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dello Ioio R, et al. A genetic framework for the control of cell division and differentiation in the root meristem. Science. 2008;322:1380–1384. doi: 10.1126/science.1164147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu YG, Mitsukawa N, Oosumi T, Whittier RF. Efficient isolation and mapping of Arabidopsis thaliana T-DNA insert junctions by thermal asymmetric interlaced PCR. Plant J. 1995;8:457–463. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1995.08030457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yan LH, et al. High-efficiency genome editing in Arabidopsis using YAO promoter-driven CRISPR/Cas9 system. Mol. Plant. 2015;8:1820–1823. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2015.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sigrist CJ, et al. PROSITE: a documented database using patterns and profiles as motif descriptors. Brief. Bioinform. 2002;3:265–274. doi: 10.1093/bib/3.3.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Apweiler R, et al. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D115–119. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Haft DH, Selengut JD, White O. The TIGRFAMs database of protein families. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:371–373. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Emanuelsson O, Nielsen H, Brunak S, von Heijne G. Predicting subcellular localization of proteins based on their N-terminal amino acid sequence. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;300:1005–1016. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Small I, Peeters N, Legeai F, Lurin C. Predotar: A tool for rapidly screening proteomes for N-terminal targeting sequences. Proteomics. 2004;4:1581–1590. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Emanuelsson O, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. Locating proteins in the cell using TargetP, SignalP and related tools. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:953–971. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Unseld M, Marienfeld JR, Brandt P, Brennicke A. The mitochondrial genome of Arabidopsis thaliana contains 57 genes in 366, 924 nucleotides. Nat. Genet. 1997;15:57–61. doi: 10.1038/ng0197-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Giege P, Brennicke A. RNA editing in Arabidopsis mitochondria effects 441 C to U changes in ORFs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.USA. 1999;96:15324–15329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Braun HP, et al. The life of plant mitochondrial complex I. Mitochondrion. 2014;19:295–313. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Haili N, et al. The pentatricopeptide repeat MTSF1 protein stabilizes the nad4 mRNA in Arabidopsis mitochondria. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:6650–6563. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Eubel H. New Insights into the respiratory chain of plant mitochondria supercomplexes and a unique composition of Complex II. Plant Physiol. 2003;133:274–286. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.024620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mitchell P, Moyle J. Chemiosmotic hypothesis of oxidative phosphorylation. Nature. 1967;213:137–139. doi: 10.1038/213137a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dimroth P, Kaim G, Matthey U. Crucial role of the membrane potential for ATP synthesis by F(1)F(o) ATP synthases. J. Exp. Biol. 2000;203:51–59. doi: 10.1242/jeb.203.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Liu W, et al. PINK1 regulates the oxidative phosphorylation machinery via mitochondrial fission. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.USA. 2011;108:12920–12924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107332108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yuan H, Liu D. Functional disruption of the pentatricopeptide protein SLG1 affects mitochondrial RNA editing, plant development, and responses to abiotic stresses in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2012;70:432–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Andreyev AY, Kushnareva YE, Starkov AA. Mitochondrial metabolism of reactive oxygen species. Biochemistry. 2005;70:200–214. doi: 10.1007/s10541-005-0102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shadel GS, Horvath TL. Mitochondrial ROS signaling in organismal homeostasis. Cell. 2015;163:560–569. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yu H, et al. ABA-mediated ROS in mitochondria regulate root meristem activity by controlling plethora expression in. Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004791. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Michel F, Umesono K, Ozeki H. Comparative and functional anatomy of group II catalytic introns–a review. Gene. 1989;82:5–30. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Michel F, Ferat JL. Structure and activities of group II introns. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1995;64:435–461. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.002251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jacquier A. Group II introns: elaborate ribozymes. Biochimie. 1996;78:474–487. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(96)84754-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Matthes A, et al. Two DEAD-box proteins may be part of RNA-dependent high-molecular-mass protein complexes in Arabidopsis mitochondria. Plant Physiol. 2007;145:1637–1646. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.108076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Keren I, et al. nMAT1, a nuclear-encoded maturase involved in the trans-splicing of nad1 intron 1, is essential for mitochondrial complex I assembly and function. Plant J. 2012;71:413–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.04998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Francs-Small CC, et al. A PORR domain protein required for rpl2 and ccmF(C) intron splicing and for the biogenesis of c-type cytochromes in Arabidopsis mitochondria. Plant J. 2012;69:996–1005. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kohler D, Schmidt-Gattung S, Binder S. The DEAD-box protein PMH2 is required for efficient group II intron splicing in mitochondria of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant. Mol. Biol. 2010;72:459–467. doi: 10.1007/s11103-009-9584-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chen H, et al. Firefly luciferase complementation imaging assay for protein-protein interactions in plants. Plant Physiol. 2008;146:368–376. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.111740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hardie DG, Ross FA, Hawley SA. AMPK: a nutrient and energy sensor that maintains energy homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012;13:251–262. doi: 10.1038/nrm3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Jones RG, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase induces a p53-dependent metabolic checkpoint. Mol. Cell. 2005;18:283–293. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jossier M, et al. SnRK1 (SNF1-related kinase 1) has a central role in sugar and ABA signalling in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2009;59:316–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Emanuelle S, et al. SnRK1 from Arabidopsis thaliana is an atypical AMPK. Plant J. 2015;82:183–192. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Laluk K, Abuqamar S, Mengiste T. The Arabidopsis mitochondria-localized pentatricopeptide repeat protein PGN functions in defense against necrotrophic fungi and abiotic stress tolerance. Plant Physiol. 2011;156:2053–2068. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.177501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Giraud E, Van Aken O, Ho LHM, Whelan J. The transcription factor ABI4 is a regulator of mitochondrial retrograde expression of ALTERNATIVE OXIDASE1a. Plant Physiol. 2009;150:1286–1296. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.139782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.De Clercq I, et al. The membrane-bound NAC transcription factor ANAC013 functions in mitochondrial retrograde regulation of the oxidative stress response in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2013;25:3472–3490. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.117168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ng S, et al. A membrane-bound NAC transcription factor, ANAC017, mediates mitochondrial retrograde signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2013;25:3450–3471. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.113985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Van Aken O, Zhang B, Law S, Narsai R, Whelan J. AtWRKY40 and AtWRKY63 modulate the expression of stress-responsive nuclear genes encoding mitochondrial and chloroplast proteins. Plant Physiol. 2013;162:254–271. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.215996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zhang X, et al. The transcription factor MYB29 is a regulator of ALTERNATIVE OXIDASE1a. Plant Physiol. 2017;173:1824–1843. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.01494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wan R, Yan C, Bai R, Huang G, Shi Y. Structure of a yeast catalytic step I spliceosome at 3.4 A resolution. Science. 2016;353:895–904. doi: 10.1126/science.aag2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Vielle-Calzada JP, Baskar R, Grossniklaus U. Delayed activation of the paternal genome during seed development. Nature. 2000;404:91–94. doi: 10.1038/35003595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Clough SJ, Bent AF. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16:735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Li XR, et al. Arabidopsis DAYU/ABERRANT PEROXISOME MORPHOLOGY9 is a key regulator of peroxisome biogenesis and plays critical roles during pollen maturation and germination in planta. Plant Cell. 2014;26:619–635. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.121087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kuhn K, et al. Phage-type RNA polymerase RPOTmp performs gene-specific transcription in mitochondria of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2009;21:2762–2679. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.068536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kikuchi S, et al. A 1-megadalton translocation complex containing TIC20 and TIC21 mediates chloroplast protein import at the inner envelope membrane. Plant Cell. 2009;21:1781–1797. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.063552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Pineau B, Layoune O, Danon A, De Paepe R. L-galactono-1, 4-lactone dehydrogenase is required for the accumulation of plant respiratory complex I. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:32500–32505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805320200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Long YP, Xie DJ, Zhao YY, Shi DQ, Yang WC. BICELLULAR POLLEN 1 is a modulator of DNA replication and pollen development in Arabidopsis. New. Phytol. 2019;222:588–603. doi: 10.1111/nph.15610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Yoo SD, Cho YH, Sheen J. Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts: a versatile cell system for transient gene expression analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:1565–1572. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Stonebloom S, et al. Loss of the plant DEAD-box protein ISE1 leads to defective mitochondria and increased cell-to-cell transport via plasmodesmata. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:17229–17234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909229106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data