A draft genome of 906 scaffolds of 115.8 Mb was assembled for Desmodesmus armatus, a diploid, lipid- and storage carbohydrate-accumulating microalga proven relevant for large-scale, outdoor cultivation, and serves as a model alga platform for improving photosynthetic efficiency and carbon assimilation for next-generation bioenergy production.

ABSTRACT

A draft genome of 906 scaffolds of 115.8 Mb was assembled for Desmodesmus armatus, a diploid, lipid- and storage carbohydrate-accumulating microalga proven relevant for large-scale, outdoor cultivation, and serves as a model alga platform for improving photosynthetic efficiency and carbon assimilation for next-generation bioenergy production.

ANNOUNCEMENT

Microalgae, having higher annual biomass production relative to terrestrial crops and potential for cultivation in salt water on nonarable lands, are critical future feedstocks for renewable liquid fuels (1–4). Desmodesmus, taxonomically divergent from the genus Scenedesmus (5, 6), has been shown to exhibit phenotypic plasticity and resilience, allowing survival in harsh and variable environments, including brackish and salt water (7–12), and to possess other beneficial traits for outdoor, large-scale, biofuel-relevant cultivation, as follows: it thrives in temperatures of 35 to 45°C (13–15), resists toxins (12) and grazers (16), accumulates microcrystalline guanine and polyphosphate (17) and lutein as an important coproduct for aquaculture (15), settles rapidly (13), and has diverse, sporopollenin-containing cell walls (18–20). Desmodesmus achieved areal harvest yield productivities of 9 to 20 g/m2 day (annual average of 11.4 g/m2 day) over the course of 2 years in outdoor, large-scale saltwater cultivation (2, 11, 21, 22) and can accumulate >55% dry cell weight (dcw) lipids (14, 23) or carbohydrates (13), both important cellular components for biofuels, making it amenable to a fractionation-based conversion pathway (24–26). Here, we report the draft nuclear and chloroplast genomes, ploidy, and potential bioenergy-relevant engineering targets of D. armatus.

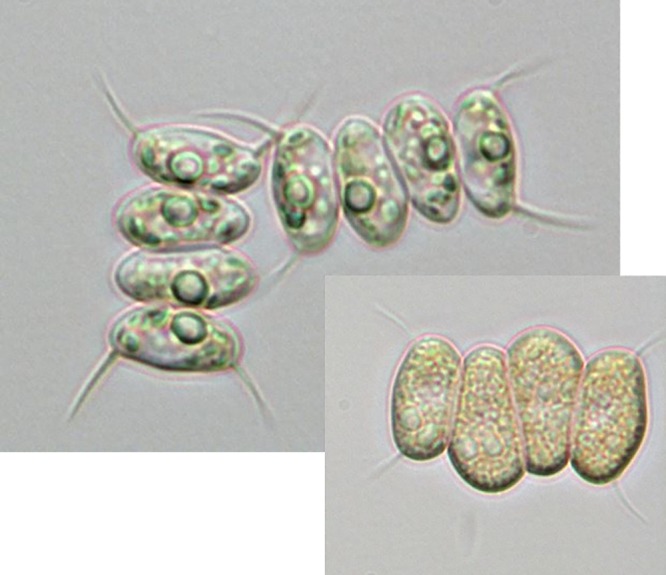

D. armatus (Fig. 1), originally isolated from Las Cruces, NM, wastewater treatment ponds in 2012, was grown photoautotrophically in flat-sided bottles in modified artificial seawater medium (MASM) under constant illumination (4000K LED flat panels, 180 μmol photons/m2), supplemented with 2% CO2. MASM contains the following (g/liter): NaCl (8), MgSO4·7H2O (2.5), KCl (0.6), NaNO3 (0.85), CaCl2·2H2O (0.3), Tris (1), KH2PO4 (0.05), NH4Cl (0.03), thiamine-HCl (3.5 mM stock; 1 ml/liter), cyanocobalamin (10 μg/L stock; 1 ml), and trace element stock (6 ml/liter). Trace element stock was made up of the following (g/liter): Na2-EDTA (1.0), FeCl3·6H2O (0.2), MnCl2·4H2O (0.072), ZnCl2 (0.02), Na2MoO4·2H2O (0.013), and CoCl2·6H2O (0.004). Genomic DNA was extracted from midexponential cells as described (27). PacBio sequence data consisted of average polymerase reads of 741,936 ± 76,024 bp, having a mean insert length of 6,026 ± 784 bp and generating a total assembly size of 116.31 Mb in 906 contigs with an N50 value of 341,806 bp and a GC content of 56.6%, and was determined to be diploid (28). This compares with the genomes of Tetradesmus obliquus (108.72 Mb; 29) and Scenedesmus obliquus (207.97 Mb; 30). Sixteen scaffolds (totaling 112,885 bp) contain chloroplast sequences identified using BLASTN against published chloroplast genomes for Chlorella vulgaris C-27 (31) and Monoraphidium neglectum (32). Proteins that may be beneficial for a robust, outdoor, bioenergy-relevant alga were identified. The presence of homologs of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii STT7 and LHCSR1/3 and the dioxygen reductases Flv3 and PTOX confirms the ability for state transition and nonphotochemical quenching processes involved in energy dissipation essential for maintaining photosynthetic electron transport chain integrity in high or fluctuating irradiances (33) and may be useful targets for the improvement of photosynthetic efficiency and harvest yields in open ponds. Polyphosphate kinase was also identified, suggesting polyphosphate production as an energy or phosphate reserve. In conclusion, the innate robustness and proven reliability of D. armatus in outdoor mass culture provides a robust yet flexible chassis for genetic engineering efforts, potentially leading to the commercial use of D. armatus as a bioenergy-relevant alga.

FIG 1.

Typical cenobium with terminal spines and intracellular changes in morphology of D. armatus under nitrogen-replete and -deplete (inset) conditions. Nitrogen-deplete conditions occur in late-stage cultures once nitrogen is depleted from the medium.

Data availability.

This whole-genome shotgun project has been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the accession number VIIQ00000000.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for the contribution of this strain and associated data from Craig Behnke at Sapphire Energy. This work was authored in part by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC, for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) under contract number DE-AC36-08GO28308. We acknowledge Nick Sweeney of NREL for the micrographs of D. armatus.

Funding was provided by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy and by the Rewiring Algal Carbon Energetics for Renewables (RACER) consortium. Additional support was provided by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory Research Data Initiative.

The views expressed in the article do not necessarily represent the views of the DOE or the U.S. Government.

This research was designed by E.P.K. and L.M.L.M., E.P.K., and D.P.A. directed the PacBio sequencing and assembly. A.N. determined ploidy. D.D. identified proteins of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Davis R, Coleman A, Wigmosta M, Markham J, Kinchin C, Zhu Y, Jones S, Han J, Canter C, Li Q. 2017. 2017 Algae harmonization study: evaluating the potential for future algal biofuel costs, sustainability, and resource assessment from harmonized modeling. NREL/TP-5100–70715 NREL, Golden, CO. [Google Scholar]

- 2.White RL, Ryan RA. 2015. Long-term cultivation of algae in open-raceway ponds: lessons from the field. Ind Biotechnol 11:213–220. doi: 10.1089/ind.2015.0006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knoshaug EP, Darzins A. 2011. Algal biofuels: the process. Chem Eng Prog 107:37–41. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams PJlB, Laurens LML. 2010. Microalgae as biodiesel & biomass feedstocks: review & analysis of the biochemistry, energetics & economics. Energy Environ Sci 3:554–590. doi: 10.1039/b924978h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hegewald E. 2000. New combinations in the genus Desmodesmus (Chlorophyceae, Scenedesmaceae). Arch Hydrobiol Suppl Algol Stud 96:1–18. doi: 10.1127/algol_stud/96/2000/1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Hannen E, FinkGodhe P, Lurling M. 2002. A revised secondary structure model for the internal transcribed spacer 2 of the green algae Scenedesmus and Desmodesmus and its implication for the phylogeny of these algae. Eur J Phycol 37:203–208. doi: 10.1017/S096702620200361X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blokker P, Schouten S, van den Ende H, De Leeuw JW, Sinninghe Damsté JS. 1998. Cell wall-specific w-hydroxy fatty acids in some freshwater green microalgae. Phytochemisty 49:691–695. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(98)00229-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Derenne S, Largeau C, Berkaloff C, Rousseau B, Wilhelm C, Hatcher PG. 1992. Non-hydrolysable macromolecular constituents from outer walls of Chlorella fusca and Nanochlorum eucaryotum. Phytochemisty 31:1923–1929. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(92)80335-C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gelin F, Volkman JK, Largeau C, Derenne S, Sinninghe Damsté JS, De Leeuw JW. 1999. Distribution of aliphatic, nonhydrolyzable biopolymers in marine microalgae. Org Geochem 30:147–159. doi: 10.1016/S0146-6380(98)00206-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gunnison D, Alexander M. 1975. Basis for the resistance of several algae to microbial decomposition. Appl Microbiol 29:729–738. doi: 10.1128/AEM.29.6.729-738.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGowen J, Knoshaug EP, Laurens LML, Dempster TA, Pienkos PT, Wolfrum E, Harmon VL. 2017. The Algae Testbed Public-Private Partnership (ATP3) framework; establishment of a national network of testbed sites to support sustainable algae production. Algal Res 25:168–177. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2017.05.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samori G, Samori C, Guerrini F, Pistocchi R. 2013. Growth and nitrogen removal capacity of Desmodesmus communis and of a natural microalgae consortium in a batch culture system in view of urban wastewater treatment: part I. Water Res 47:791–801. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ho S-H, Lai Y-Y, Chiang C-Y, Chen C-NN, Chang J-S. 2013. Selection of elite microalgae for biodiesel production in tropical conditions using a standardized platform. Bioresour Technol 147:135–142. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pan Y-Y, Wan S-T, Chuang L-T, Chang Y-W, Chen C-NN. 2011. Isolation of thermo-tolerant and high lipid content green microalgae: oil accumulation is predominantly controlled by photosystem efficiency during stress treatments in Desmodesmus. Bioresour Technol 102:10510–10517. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.08.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xie Y, Ho S-H, Chen C-NN, Chen C-Y, Ng I-S, Jing K-J, Chang J-S, Lu Y. 2013. Phototrophic cultivation of a thermo-tolerant Desmodesmus sp. for lutein production: effects of nitrate concentration, light intensity, and fed-batch operation. Bioresour Technol 144:435–444. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lurling M. 2003. Phenotypic plasticity in the green algae Desmodesmus and Scenedesmus with special reference to the induction of defensive morphology. Ann Limnol Int J Limnol 39:85–101. doi: 10.1051/limn/2003014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moudrikova S, Nedbal L, Solovchenko A, Mojzes P. 2017. Raman microscopy shows that nitrogen-rich cellular inclusions in microalgae are microcrystalline guanine. Algal Res 23:216–222. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2017.02.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.An SS, Friedl T, Hegewald E. 1999. Phylogenetic relationships of Scenedesmus and Scenedesmus-like coccoid green algae as inferred from ITS-2 rDNA sequence comparisons. Plant Biol 1:418–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1438-8677.1999.tb00724.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trainor FR. 1998. Nova Hedwigia: biological aspects of Scenedesmus (Chlorophyceae) phenotypic plasticity, vol 117 J. Cramer, Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vanormelingen P, Hegewald E, Braband A, Kitschke M, Friedl T, Sabbe K, Vyverman W. 2007. The systematics of a small spineless Desmodesmus species, D. costato-granulatus (Sphaeropleales, Chlorophyceae), based on ITS2 rDNA sequence analysis and cell wall morphology. J Phycol 43:378–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2007.00325.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knoshaug EP, Wolfrum E, Laurens LML, Harmon VL, Dempster TA, McGowen J. 2018. Unified field studies of the Algae Testbed Public-Private Partnership as the benchmark for algae agronomics. Sci Data 5:180267. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2018.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huntley ME, Johnson ZI, Brown SL, Sills DL, Gerber L, Archibald I, Machesky SC, Granados J, Beal C, Greene CH. 2015. Demonstrated large-scale production of marine microalgae for fuels and feed. Algal Res 10:249–265. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2015.04.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xia L, Rong J, Yang H, He Q, Zhang D, Hu C. 2014. NaCl as an effective inducer for lipid accumulation in freshwater microalgae Desmodesmus abundans. Bioresour Technol 161:402–409. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.03.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knoshaug EP, Dong T, Spiller R, Nagle N, Pienkos PT. 2018. Pretreatment and fermentation of salt-water grown algal biomass as a feedstock for biofuels and high-value biochemicals. Algal Res 36:239–248. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2018.10.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dong T, Knoshaug EP, Davis R, Laurens LML, Van Wychen S, Pienkos PT, Nagle N. 2016. Combined algal processing: a novel integrated biorefinery process to produce algal biofuels and bioproducts. Algal Res 19:316–323. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2015.12.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laurens LML, Nagle N, Davis R, Sweeney N, Van Wychen S, Lowell A, Pienkos PT. 2015. Acid-catalyzed algal biomass pretreatment for integrated lipid and carbohydrate-based biofuels production. Green Chem 17:1145–1158. doi: 10.1039/C4GC01612B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Varela-Alvarez E, Andreakis N, Lago-Leston A, Pearson GA, Serrao EA, Procaccini G, Duarte CM, Marba N. 2006. Genomic DNA isolation from green and brown algae (Caulerpales and Fucales) for microsatellite library construction. J Phycol 42:741–745. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2006.00218.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knaus BJ, Grunwald NJ. 2018. Inferring variation in copy number using high throughput sequencing data in R. Front Genet 9:123. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carreres BM, de Jaeger L, Springer J, Barbosa MJ, Breuer G, van den End EJ, Kleinegris DMM, Schaffers I, Wolbert EJH, Zhang H, Lamers PP, Draaisma RB, Martins dos Santos VAP, Wijffels RH, Eggink G, Schaap PJ, Martens DE. 2017. Draft genome sequence of the oleaginous green alga Tetradesmus obliquus UTEX 393. Genome Announc 5:e01449-16. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01449-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Starkenburg SR, Polle JEW, Hovde B, Daligault HE, Davenport KW, Huang A, Neofotis P, McKie-Krisberg Z. 2017. Draft nuclear genome, complete chloroplast genome, and complete mitochondrial genome for the biofuel/bioproduct feedstock species Scenedesmus obliquus strain DOE0152z. Genome Announc 5:e00617-17. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00617-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wakasugi T, Nagai T, Kapoor M, Sugita M, Ito M, Ito S, Tsudzuki J, Nakashima K, Tsudzuki T, Suzuki Y, Hamada A, Ohta T, Inamura A, Yoshinaga K, Sugiura M. 1997. Complete nucleotide sequence of the chloroplast genome from the green alga Chlorella vulgaris: the existence of genes possibly involved in chloroplast division. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94:5967–5972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bogen C, Al-Dilaimi A, Albersmeier A, Wichmann J, Grundmann M, Rupp O, Lauersen KJ, Blifernez-Klassen O, Kalinowski J, Goesmann A, Mussgnug JH, Kruse O. 2013. Reconstruction of the lipid metabolism for the microalga Monoraphidium neglectum from its genome sequence reveals characteristics suitable for biofuel production. BMC Genomics 14:926. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wobbe L, Bassi R, Kruse O. 2016. Multi-level light capture control in plants and green algae. Trends Plant Sci 21:55–68. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2015.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This whole-genome shotgun project has been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the accession number VIIQ00000000.